Abstract

Background

We aimed to evaluate whether major depressive disorder (MDD) could aggravate the outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or whether the genetic liability to COVID-19 could trigger MDD.

Aims

We aimed to assess bidirectional causal associations between MDD and COVID-19.

Methods

We performed genetic correlation and Mendelian randomisation (MR) analyses to assess potential associations between MDD and three COVID-19 outcomes. Literature-based network analysis was conducted to construct molecular pathways connecting MDD and COVID-19.

Results

We found that MDD has positive genetic correlations with COVID-19 outcomes (rg: 0.10–0.15). Our MR analysis indicated that genetic liability to MDD is associated with increased risks of COVID-19 infection (odds ratio (OR)=1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.00 to 1.10, p=0.039). However, genetic liability to the three COVID-19 outcomes did not confer any causal effects on MDD. Pathway analysis identified a panel of immunity-related genes that may mediate the links between MDD and COVID-19.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that MDD may increase the susceptibility to COVID-19. Our findings emphasise the need to increase social support and improve mental health intervention networks for people with mood disorders during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19; depressive disorder, major; Mendelian randomization analysis; depression; genetics, behavioral

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Observational studies have reported that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder (MDD).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

MDD was associated with a 5% increased risk for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

It is necessary to improve mental health interventions for people with mood disorders during the pandemic.

Introduction

Since the inception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many risk factors have been revealed, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes and smoking.1–6 Meanwhile, the neurological pathogenesis of COVID-19 remarkably threatens the mental health of affected individuals. Various COVID-19 outcomes cause an elevated risk for mental stress and mental disorders.7 8 After the acute phase of COVID-19, some patients develop lingering symptoms, such as pulmonary dysfunction, muscle exertion and mood changes that persist for months. These postrecovery symptoms are called ‘long COVID-19 syndrome’ and commonly include depression, anxiety and cognitive impairment.9–14 These psychopathological sequelae of COVID-19 are both from an improper immune response to the virus and neuroinflammation caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and augmented by disease-related psychological stressors.15 16

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mood disorder that causes persistent sadness and loss of interest. Changes in various proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines are critical in the pathogenesis of MDD.17 Pre-existing depression symptoms may impact the outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which corresponds with higher rates of symptomatic disease, hospitalisation or death.18 The prolonged release of proinflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 may inhibit the activity of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus and increase the levels of reactive oxygen species, resulting in the propagation of a vicious cycle between MDD and COVID-19.19

Until now, associations reported in observational studies have shown weak evidence for the causal associations between MDD and COVID-19, and the relationship between the two remains somewhat debatable. Therefore, in-depth studies are urgently needed to identify the relationship between MDD and COVID-19 and elucidate the mechanisms behind their interactions. The Mendelian randomisation (MR) method can be used to explore causal associations between traits.20–23 We tested genetic relationships between MDD and three COVID-19 outcomes (SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 hospitalisation and critical COVID-19) using genetic correlation analysis, the MR framework and literature-based network analysis.

Methods

Data sources and study design

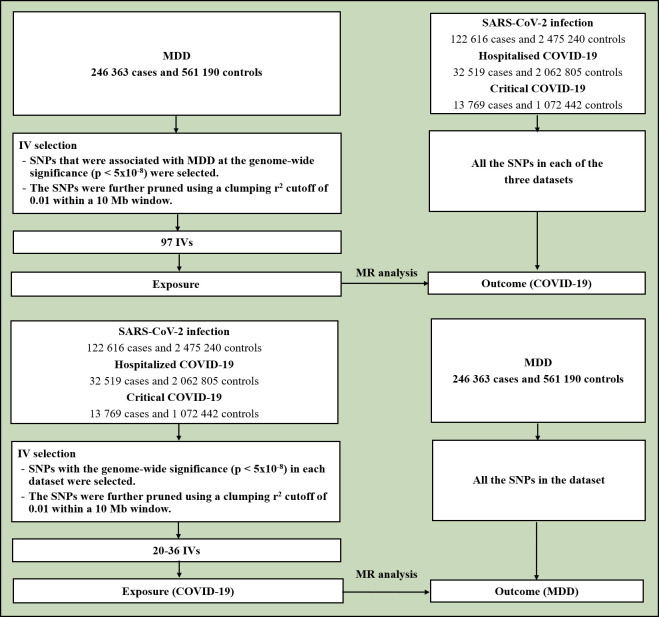

The design of the study is described in figure 1. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary datasets of MDD and COVID-19 were analysed. The MDD dataset included 246 363 cases and 561 190 controls.24 Three datasets on COVID-19 were obtained from the Host Genetic Initiative GWAS meta-analyses (round 7), including SARS-CoV-2 infection (122 616 cases and 2 475 240 controls), hospitalised COVID-19 (32 519 hospitalised COVID-19 cases and 2 062 805 controls) and critical COVID-19 (13 769 very severe respiratory confirmed COVID-19 cases and 1 072 442 controls).25

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IV, instrumental variable; MDD, major depressive disorder; MR, Mendelian randomisation; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

All participants were of European origin. In GWAS, the label ‘SARS-CoV-2 infection’ represents the overall likelihood of contracting the virus, whereas ‘hospitalised COVID-19’ and ‘critical COVID-19’ reflect the severity of the disease. Therefore, both hospitalised COVID-19 and critical COVID-19 were called ‘severe COVID-19’ in this study.

Genetic correlation analysis

We evaluated the genetic correlations between MDD and the COVID-19 outcomes using linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression.26 27 The 1 000 Genome Project phase III of the European population was leveraged to infer the LD structure.

Statistical analysis for MR

In the TwoSampleMR package (V.0.5.6),28 causal associations were evaluated with the inverse variance weighting (IVW) model along with the weighted median (WM) and MR-Egger as complementary measures ensuring sensitivity.29–31 While the WM and MR-Egger models are less statistically powerful than the IVW model, they perform in more robust fashion in cases of horizontal pleiotropy or invalid instruments. Here, potential horizontal pleiotropy was evaluated by examining the intercept from the MR-Egger regression,29 and heterogeneity by Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics (p<0.05 and I2>0.25).

For each exposure phenotype, genome-wide significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with MDD (p<5×10–8) were pruned by a clumping r2 value of 0.01 within a 10 Mb window and used as instrumental variables (IVs).

Knowledge-based analysis

To explore the potential connection between MDD and COVID-19 at the molecular level, we used the Pathway Studio environment,30 allowing one to perform large-scale literature data mining in the automated mode. After a manual review of the results for quality control, we constructed a set of molecular pathways connecting MDD and COVID-19, along with their downstream targets and upstream regulators. More details were described previously.13 In this study, the molecules/genes connecting MDD and COVID-19 were called ‘mediating molecules/genes’.

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) were detected using STRING V.11.31 Enrichment analyses of the candidate genes were run on a Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)-based pathway using functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations (FUMA).32

Results

Genetic correlation analysis

As shown in table 1, genetic correlation analyses indicated that MDD had positive genetic correlations with SARS-CoV-2 infection (rg=0.10 (0.04), p=0.007), hospitalised COVID-19 (rg=0.15 (0.03), p<0.001) and critical COVID-19 (rg=0.10 (0.03), p=0.003).

Table 1.

Genetic correlations between MDD and COVID-19

| Trait 1 | Trait 2 | rg (SE) | Z | P value |

| MDD | SARS-CoV-2 infection | 0.10 (0.04) | 2.72 | 0.007 |

| MDD | Hospitalised COVID-19 | 0.15 (0.03) | 4.57 | <0.001 |

| MDD | Critical COVID-19 | 0.10 (0.03) | 2.97 | 0.003 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; MDD, major depressive disorder; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SE, standard error.

MR analysis

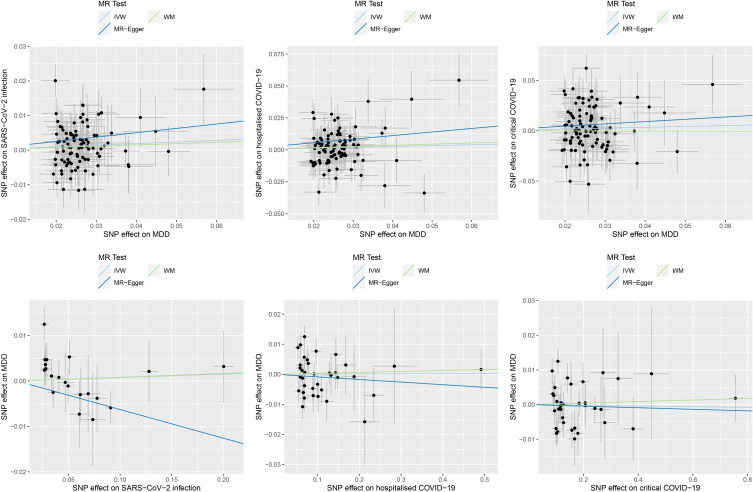

In the MR analysis of the causal effects of MDD on the COVID-19 outcomes, a total of 97 IVs were derived from the MDD dataset. We found that genetic liability to MDD was associated with an increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection (odds ratio (OR)=1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.00 to 1.10, p=0.039) (table 2 and figure 2). There was no solid evidence for the causal effect of MDD on COVID-19 hospitalisation (OR=1.07, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.18, p=0.175) and critical COVID-19 (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 0.92 to 1.28, p=0.306).

Table 2.

Causal effects of MDD on COVID-19

| Exposure | Outcome | Method | b (SE) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| MDD | SARS-CoV-2 infection | IVW | 0.047 (0.023) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.039 |

| MDD | SARS-CoV-2 infection | WM | 0.038 (0.030) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.10) | 0.203 |

| MDD | SARS-CoV-2 infection | MR-Egger | 0.126 (0.127) | 1.13 (0.88 to 1.46) | 0.325 |

| MDD | Hospitalised COVID-19 | IVW | 0.066 (0.049) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.18) | 0.175 |

| MDD | Hospitalised COVID-19 | WM | 0.090 (0.066) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.24) | 0.171 |

| MDD | Hospitalised COVID-19 | MR-Egger | 0.279 (0.269) | 1.32 (0.78 to 2.24) | 0.301 |

| MDD | Critical COVID-19 | IVW | 0.085 (0.083) | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.28) | 0.306 |

| MDD | Critical COVID-19 | WM | −0.007 (0.100) | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.21) | 0.947 |

| MDD | Critical COVID-19 | MR-Egger | 0.228 (0.452) | 1.26 (0.52 to 3.04) | 0.615 |

b, effect size; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MDD, major depressive disorder; MR, Mendelian randomisation; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SE, standard error; WM, weighted median.

Figure 2.

Causal associations between MDD and COVID-19. The upper panel shows the causal effects of MDD on COVID-19 outcomes. The lower panel shows the causal effects of COVID-19 outcomes on MDD. The trait on the x-axis denotes exposure, the trait on the y-axis denotes outcome and each cross point represents an instrumental variable. The lines denote the effect sizes (b) of an exposure on an outcome. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MDD, major depressive disorder; MR, Mendelian randomisation; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; WM, weighted median.

In the MR analysis of the causal effects of the COVID-19 outcomes on MDD, the numbers of IVs were 20 for SARS-CoV-2 infection, 36 for hospitalised COVID-19 and 36 for critical COVID-19 (table 3). We found that the genetic liability to the COVID-19 outcomes was not associated with the risk of MDD, including SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.05, p=0.691), COVID-19 hospitalisation (OR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.02, p=0.955) and critical COVID-19 (OR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.01, p=0.859).

Table 3.

Causal effects of COVID-19 on MDD

| Exposure | Outcome | Method | b (SE) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | MDD | IVW | 0.008 (0.021) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.691 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | MDD | WM | 0.008 (0.025) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | 0.766 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | MDD | MR-Egger | −0.063 (0.034) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 0.081 |

| Hospitalised COVID-19 | MDD | IVW | 0.001 (0.010) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.955 |

| Hospitalised COVID-19 | MDD | WM | 0.003 (0.011) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.777 |

| Hospitalised COVID-19 | MDD | MR-Egger | −0.009 (0.019) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.03) | 0.643 |

| Critical COVID-19 | MDD | IVW | −0.001 (0.006) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.859 |

| Critical COVID-19 | MDD | WM | 0.002 (0.007) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.764 |

| Critical COVID-19 | MDD | MR-Egger | −0.002 (0.011) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.839 |

b, effect size; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MDD, major depressive disorder; MR, Mendelian randomisation; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SE, standard error; WM, weighted median.

The MR-Egger regression test did not support the existence of pleiotropy of genetic instrument variables in all the MR analyses (online supplemental tables 1 and 2). The sensitivity analysis showed that the causal effect estimates between the IVW and WM methods were the same, while the MR-Egger model showed differences with the other two models in some MR tests. The Cochran Q test and I2 statistic did not support the existence of heterogeneity in the causal effects of MDD on SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalised COVID-19 but suggested possible heterogeneity in the causal effect of MDD on critical COVID-19 (p=0.001, I2=0.341).

gpsych-2022-101006supp001.pdf (20.6KB, pdf)

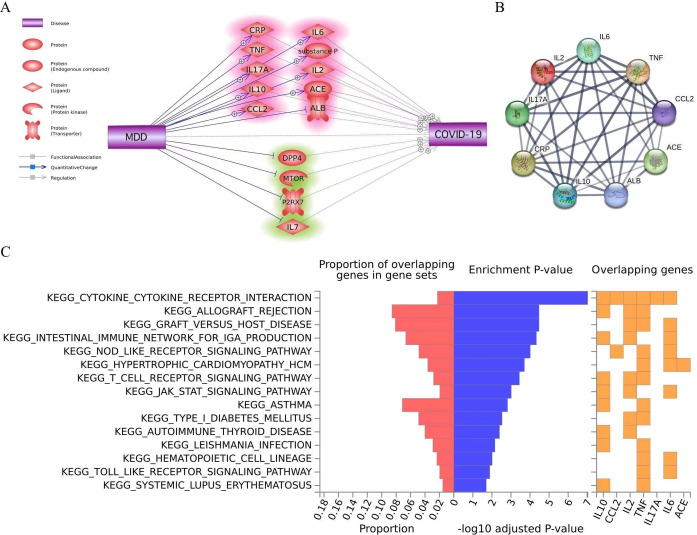

Knowledge-based analysis

Literature-based pathway analysis identified a total of 14 mediating molecules connecting MDD and COVID-19 (figure 3A). Each relation was supported by ≥3 references. A set of 10 molecules quantitatively changed in MDD and enhanced the development of COVID-19, including nine genes (ACE, ALB, CCL2, CRP, IL10, IL17A, IL2, IL6 and TNF) and substance P (highlighted in red in figure 3A). We called these nine genes ‘risk mediating genes’. On the other hand, a total of four MDD-driven genetic changes suppress the development of COVID-19, including DPP4, IL7, MTOR and P2R×7 (protective mediating genes, highlighted in green in figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Molecular pathways connecting MDD and COVID-19. (A) Molecular pathways from MDD to COVID-19. Promoting effects are highlighted in red, and inhibitory effects are highlighted in green. Quantitative genetic changes driven by MDD exert more promoting than inhibitory effects on COVID-19. (B) Protein-protein interactions among the 24 COVID-19-promoting genes. Line sizes are proportional to the combined scores of the interactions. (C) KEGG-based pathway analysis of risk-mediating genes. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MDD, major depressive disorder.

PPI analysis using the STRING framework showed that the nine risk-mediating proteins formed a tightly interconnected network (figure 3B). KEGG-based pathway enrichment analysis in FUMA showed that the set of nine genes was enriched in immunity-related molecular pathways, including those for cytokine‒cytokine receptor interaction, allograft rejection, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor signalling, toll-like receptor signalling and type 1 diabetes (figure 3C).

Discussion

Main findings

This study aimed to explore the potential causal relationships between MDD and the COVID-19 outcomes. Our results indicated that MDD was associated with a 5% increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR=1.05).

Recent pandemic surveys revealed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms in COVID-19 survivors is approximately 21%–45%.33 34 However, our study did not support a causal effect of COVID-19 on MDD in the context of genetic variation. It is well known that COVID-19-associated problems are vital mental stressors.35 Therefore, MDD may be primarily triggered by psychological stress associated with COVID-19 rather than by genetic liability to COVID-19.36 Together, COVID-19 and MDD can form a vicious circle, aggravating the risk for each other.

By using literature-based analysis, we explored potential mechanisms underlying the connection between MDD and COVID-19. Notably, the SARS-CoV-2 virus is capable of causing a cytokine storm, with the same primary players as in the neuroinflammatory phenotype seen in patients with MDD, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6.37 38 In particular, IL-6 induces a variety of acute-phase proteins and worsens the inflammatory response, and its high expression increases mucus production and aggravates disease in patients with COVID-19.39 Even more intriguing are the clinical observations that antidepressants can alleviate the symptoms of acute infection with SARS-CoV-2 and a constellation of symptoms observed in patients with long COVID syndrome.40 41 The most pronounced anti-inflammatory action was detected in agonists of sigma-1 receptors of the endoplasmic reticulum, particularly fluvoxamine.42 43 In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants are capable of decreasing the production of ceramides and, therefore, suppressing the activity of acid sphingomyelinase, which is a SARS-CoV-2 facilitating host factor.42 44 Certain antidepressants also rebalance the kinin-kallikrein system by potentiating the anti-inflammatory effects of bradykinin receptor B2 (BDKRB2) and suppressing the proinflammatory signal of bradykinin receptor B1 (BDKRB1).45

In summary, it seems that MDD and COVID-19 share a pathophysiological feature of an enhanced inflammatory background, which may explain the link between the two diseases. Notably, enhanced inflammation is common in people with mental illness, indicating that they may be at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer outcomes.46 47 Therefore, we recommend that people with MDD should be made aware of their increased susceptibility to contracting symptomatic infection with COVID-19 and its adverse outcomes.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The study was conducted using datasets from the European population. Therefore, our results may not be suitable for other populations. Only genetic liabilities to COVID-19 and MDD were considered, with no regard to the confounding effects of other factors, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and insomnia, which have been shown to be closely correlated with MDD and COVID-19.48–51

Implications

In summary, our study supports that MDD may augment the susceptibility to COVID-19, primarily through the priming of neuroinflammatory cascades. Our findings emphasise the need to increase social support and improve the networks of mental health interventions for people with mood disorders during the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium and the Host Genetic Initiative who generously shared the genome-wide association study data.

Biography

Ancha Baranova graduated with a PhD from Moscow State University in 1998 and with a DSci from the Russian Academy of Science in Russia. Currently, she is a professor in the School of Systems Biology at George Mason University in Virginia, USA. She is an expert in a variety of research fields, including chronic liver diseases, cancer and other illnesses, and anti-ageing research. Her lab has discovered many biomarkers for chronic liver diseases, cancer and other illnesses, the biosynthesis of melanin in human adipose, some properties of cell-free DNA, and a variety of novel functions for known biomolecules. Dr Baranova’s research has recently focused on anti-ageing and its major pathophysiological components: systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and organ fibrosis. Her work in personalised medicine emphasises longitudinal monitoring and management of health in pre-symptomatic individuals and also augmenting the body’s homeostasis by non-pharmacological means.

Footnotes

Contributors: FZ conceived the project and supervised the study. AB, YZ, and FZ wrote the manuscript. FZ and HC analyzed the data and created the figures and tables. FZ was responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, et al. Data from: Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, July 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03819-3. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. Data from: The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, April 8, 2022. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-020-0636-6.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval has been obtained in all the original studies.

References

- 1.Baranova A, Cao H, Teng S, et al. A phenome-wide investigation of risk factors for severe COVID-19. J Med Virol 2023;95:e28264. 10.1002/jmv.28264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao S, Baranova A, Cao H, et al. Genetic mechanisms of COVID-19 and its association with smoking and alcohol consumption. Brief Bioinform 2021;22:bbab284. 10.1093/bib/bbab284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao H, Baranova A, Wei X, et al. Bidirectional causal associations between type 2 diabetes and COVID-19. J Med Virol 2023;95:e28100. 10.1002/jmv.28100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranova A, Xu Y, Cao H, et al. Associations between pulse rate and COVID-19. J Med Virol 2023;95:e28194. 10.1002/jmv.28194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranova A, Song Y, Cao H, et al. Causal associations between basal metabolic rate and COVID-19. Diabetes 2023;72:149–54. 10.2337/db22-0610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, Baranova A. Smoking quantitatively increases risk for COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2022;60:2101273. 10.1183/13993003.01273-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranova A, Cao H, Zhang F. Causal effect of COVID‐19 on Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. J Med Virol 2023;95:e28107. 10.1002/jmv.28107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranova A, Cao H, Zhang F. Severe COVID-19 increases the risk of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2022;317:114809. 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson C, Davis D, Roche M, et al. What are the long-term holistic health consequences of COVID-19 among survivors? an umbrella systematic review. J Med Virol 2022;94:5653–68. 10.1002/jmv.28086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiabane E, Pain D, Aiello EN, et al. Psychiatric symptoms subsequent to COVID-19 and their association with clinical features: a retrospective investigation. Psychiatry Res 2022;316:114757. 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asadi-Pooya AA, Akbari A, Emami A, et al. Long COVID syndrome-associated brain FOG. J Med Virol 2022;94:979–84. 10.1002/jmv.27404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fioravanti G, Bocci Benucci S, Prostamo A, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health in a sample of Italian adults: a three-wave longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res 2022;315:114705. 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranova A, Cao H, Teng S, et al. Shared genetics and causal associations between COVID-19 and multiple sclerosis. J Med Virol 2023;95:e28431. 10.1002/jmv.28431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murata F, Maeda M, Ishiguro C, et al. Acute and delayed psychiatric sequelae among patients hospitalised with COVID-19: a cohort study using life study data. Gen Psychiatr 2022;35:e100802. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:34–9. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Mello AJ, Moretti M, Rodrigues ALS. SARS-CoV-2 consequences for mental health: neuroinflammatory pathways linking COVID-19 to anxiety and depression. World J Psychiatry 2022;12:874–83. 10.5498/wjp.v12.i7.874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogelzangs N, de Jonge P, Smit JH, et al. Cytokine production capacity in depression and anxiety. Transl Psychiatry 2016;6:e825. 10.1038/tp.2016.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceban F, Nogo D, Carvalho IP, et al. Association between mood disorders and risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1079–91. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y-K, Na K-S, Myint A-M, et al. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in neuroinflammation, neurogenesis and the neuroendocrine system in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2016;64:277–84. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai L, Liu Y, He L. Investigating genetic causal relationships between blood pressure and anxiety, depressive symptoms, neuroticism and subjective well-being. Gen Psychiatr 2022;35:e100877. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baranova A, Cao H, Zhang F. Causal associations and shared genetics between hypertension and COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology March 23, 2023. 10.1002/jmv.28698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baranova A, Chandhoke V, Cao H, et al. Shared genetics and bidirectional causal relationships between type 2 diabetes and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. General Psychiatry 2023;36:e100996. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li N, Zhou R, Zhang B. Handgrip strength and the risk of major depressive disorder: a two-sample mendelian randomisation study. General Psychiatry 2022;35:e100807. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Commun 2018;9:1470. 10.1038/s41467-018-03819-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative . The COVID-19 host genetics initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Eur J Hum Genet 2020;28:715–8. 10.1038/s41431-020-0636-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh P-R, Finucane HK, et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2015;47:291–5. 10.1038/ng.3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet 2015;47:1236–41. 10.1038/ng.3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, et al. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 2018;7:e34408. 10.7554/eLife.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through egger regression. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:512–25. 10.1093/ije/dyv080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikitin A, Egorov S, Daraselia N, et al. Pathway studio -- the analysis and navigation of molecular networks. Bioinformatics 2003;19:2155–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. String v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D607–13. 10.1093/nar/gky1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, et al. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun 2017;8:1826. 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2021;1486:90–111. 10.1111/nyas.14506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khraisat B, Toubasi A, AlZoubi L, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence: the psychological sequelae among COVID-19 survivors. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2022;26:234–43. 10.1080/13651501.2021.1993924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutherford BR, Choi CJ, Chrisanthopolous M, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic as a traumatic stressor: mental health responses of older adults with chronic PTSD. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021;29:105–14. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021;295:113599. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mingoti MED, Bertollo AG, Simões JLB, et al. COVID-19, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation in the depression route. J Mol Neurosci 2022;72:1166–81. 10.1007/s12031-022-02004-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Wu X, Wang Y, et al. TNF-Α, IL-6 and hsCRP in patients with melancholic, atypical and anxious depression: an antibody array analysis related to somatic symptoms. Gen Psychiatr 2022;35:e100844. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Immunotherapeutic implications of IL-6 blockade for cytokine storm. Immunotherapy 2016;8:959–70. 10.2217/imt-2016-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenze EJ, Mattar C, Zorumski CF, et al. Fluvoxamine vs placebo and clinical deterioration in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:2292–300. 10.1001/jama.2020.22760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoertel N, Sánchez-Rico M, Kornhuber J, et al. Antidepressant use and its association with 28-day mortality in inpatients with SARS-CoV-2: support for the FIASMA model against COVID-19. J Clin Med 2022;11:5882. 10.3390/jcm11195882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashimoto Y, Suzuki T, Hashimoto K. Mechanisms of action of fluvoxamine for COVID-19: a historical review. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:1898–907. 10.1038/s41380-021-01432-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashimoto K. Repurposing of CNS drugs to treat COVID-19 infection: targeting the sigma-1 receptor. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2021;271:249–58. 10.1007/s00406-020-01231-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geiger N, Kersting L, Schlegel J, et al. The acid ceramidase is a SARS-CoV-2 host factor. Cells 2022;11:2532. 10.3390/cells11162532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gouda AS, Mégarbane B. Molecular bases of serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant-attributed effects in COVID-19: a new insight on the role of bradykinins. J Pers Med 2022;12:1487. 10.3390/jpm12091487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry 2021;20:124–30. 10.1002/wps.20806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long J, Tian L, Baranova A, et al. Convergent lines of evidence supporting involvement of NFKB1 in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2022;312:114588. 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang F, Rao S, Cao H, et al. Genetic evidence suggests posttraumatic stress disorder as a subtype of major depressive disorder. J Clin Invest 2022;132:e145942. 10.1172/JCI145942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baranova A, Cao H, Zhang F. Shared genetic liability and causal effects between major depressive disorder and insomnia. Hum Mol Genet 2022;31:1336–45. 10.1093/hmg/ddab328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis C, Lewis K, Roberts A, et al. COVID-19-related posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with lived experience of psychiatric disorder. Depress Anxiety 2022;39:564–72. 10.1002/da.23262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campo-Arias A, Pedrozo-Pupo JC, Caballero-Domínguez CC. Relation of perceived discrimination with depression, insomnia and post-traumatic stress in COVID-19 survivors. Psychiatry Res 2022;307:114337. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gpsych-2022-101006supp001.pdf (20.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, et al. Data from: Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, July 2, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03819-3. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. Data from: The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, April 8, 2022. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-020-0636-6.