Abstract

Despite the existence of numerous studies supporting a pathological link between fructose consumption and the development of the metabolic syndrome and its sequelae, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), this link remains a contentious issue. With this article, we shed a light on the impact of sugar/fructose intake on hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL), an outcome parameter known to be dysregulated in subjects with type 2 diabetes and/or NAFLD. In this review, we present findings from human intervention studies using physiological doses of sugar as well as mechanistic animal studies. There is evidence from both human and animal studies that fructose is a more potent inducer of hepatic lipogenesis than glucose. This is most likely due to the liver’s prominent physiological role in fructose metabolism, which may be disrupted under pathological conditions by increased hepatic expression of fructolytic and lipogenic enzymes. Increased DNL may not only contribute to ectopic fat deposition (i.e. in the liver), but it may also impair several metabolic processes through DNL-related fatty acids (e.g. beta-cell function, insulin secretion, or insulin sensitivity).

Keywords: sugar, glucose, fructose, de novo lipogenesis, fatty acids

Introduction

Metabolic health is at risk in societies with an excess supply of energy-dense palatable food and drinks and an everyday life with low physical activity. There is a global epidemic of metabolic syndrome (Saklayen 2018), which includes obesity (particularly visceral adipose tissue accumulation), dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and hypertension. Importantly, this syndrome not only affects adults but also children and adolescents, in particular in developing countries (Noubiap et al. 2022). Similarly, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, is increasing (Moore 2010, Sahota et al. 2020, Riazi et al. 2022). The metabolic syndrome, with all of its associated comorbidities, not only burdens the affected individual but also the public health care system (Boudreau et al. 2009).

It is commonly acknowledged that an increased body weight, associated with a positive energy balance, is a major trigger for the development of metabolic diseases. It is assumed, however, that factors other than an imbalanced energy intake and expenditure can influence metabolic health. A well-balanced macronutrient intake, characterized by a moderate fat and carbohydrate intake, with a focus on sugar restriction, is regarded as an important component of a healthy diet. A high intake of added sugars, and in particular of fructose – which is often present in a typical western diet – is considered to be a principal factor promoting metabolic derangements (Lim et al. 2010, Jensen et al. 2018). Despite numerous studies, it is still debated whether the metabolic effects of added sugars are mediated by excess energy intake/weight gain or whether fructose and glucose affect metabolism differently and independently of excess caloric intake. This review aims to shed a light on the current literature regarding this question.

Sugar consumption and its effects

Current recommendations

To reduce the risk of developing obesity and metabolic diseases, the World Health Organization recommends that adults and children consume less than 10% (preferably less than 5%) of their energy needs from free sugar (WHO 2015). Importantly, free sugars include monosaccharides and disaccharides added to food and beverages as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices, and fruit juice concentrates. Recent studies on sugar intake in Europe, Latin America, and the USA found that mean sugar intakes in most countries were higher than the recommended intake (Fisberg et al. 2018, Löwik 2021, DiFrancesco et al. 2022). As a consequence, measures to reduce sugar intakes such as better food labeling or taxes on sweetened food are discussed or already implemented in many countries.

Dietary glucose and fructose

Glucose and fructose are stereoisomers. Fructose displays a higher sweetening power compared to glucose (Moskowitz 1970). Fructose and glucose occur naturally as monosaccharides in fruits and honey but also as sucrose (a disaccharide consisting of glucose and fructose). Other sugar sources include table sugar (sucrose) or high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) (a mixture of fructose and glucose), concentrated fruit juices, agave or maple syrup, and so on. Sugar added to food and beverages as sweeteners are termed ‘added sugars’. Importantly, the digestion/absorption of sugar from fruits is much slower than that of beverages and thus is unlikely to be associated with any negative effects. Unfavorable metabolic effects are particularly induced by beverages containing high amounts of free sugar that are rapidly absorbed, as detailed below. HFCS is manufactured industrially from corn starch through the isomerization of glucose to fructose. The proportion of fructose varies between 42 and 90% in HFCS (Serna-Saldivar 2016). HFCS with 42% fructose is widely used as a sweetener in processed foods, whereas HFCS with 55% fructose is commonly used in beverage production (Kay Parker 2010). HFCS was first introduced to the market in the USA in the 1970s, and it is now a significant US export product, particularly to developing countries. The average fructose intake increased since the 1970s in the USA (Tappy & Lê 2010). HFCS is a cheap sweetener used in the food and beverage industries, and its consumption is linked to the occurrence of type 2 diabetes (Kmietowicz 2012) and other metabolic diseases, as described below.

Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption is a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases

A major source of added sugars are sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) (Johnson et al. 2009, Malik & Hu 2022). Their consumption has been linked not only to the development of obesity but also to its complications such as type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disease (Malik & Hu 2022). Prospective cohort studies from the USA and the UK found an association between high SSB consumption and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes independently of obesity (Imamura et al. 2015). Similarly, studies confirmed that habitual SSB consumption is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of dyslipidemia and coronary heart disease (Te Morenga et al. 2014, Yin et al. 2021). Importantly, studies showed that habitual SSB consumption has a dose-dependent effect on the risk of NAFLD (Ouyang et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2019) and that SSB intake in early childhood is associated with the later development of hepatic steatosis in adulthood (Sekkarie et al. 2021). In addition to metabolic abnormalities, there is evidence of a link between SSB consumption and breast cancer, pancreatic and prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer (Malik & Hu 2022).

Worldwide, SSB intake is still rising (Singh et al. 2015, Malik & Hu 2022). However, regional differences regarding SSB consumption are striking. Overall, SSB intake is highest in men and women in Latin America and the Caribbean (average SSB intake about 325 g/day), where it has been rising for decades. In contrast, SSB intake in western high-income countries has stabilized since the 1990s at around 150–200 g/day (Malik & Hu 2022). In Asian countries, SSB consumption is remarkably low (the average intake of SSB is about 30 g/day). Given these data on global SSB consumption, the global burden of obesity and chronic diseases for societies is likely to rise further, particularly in developing countries.

A specific role for fructose in the etiology of cardiometabolic diseases?

Differences between fructose and glucose metabolism

Although high sugar consumption is recognized as a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases, the debate over whether the fructose component of consumed sugar plays a specific role in the etiology of such diseases is still ongoing. This question cannot be easily assessed by epidemiologic studies as fructose is rarely ingested in a pure form but mostly co-ingested with glucose.

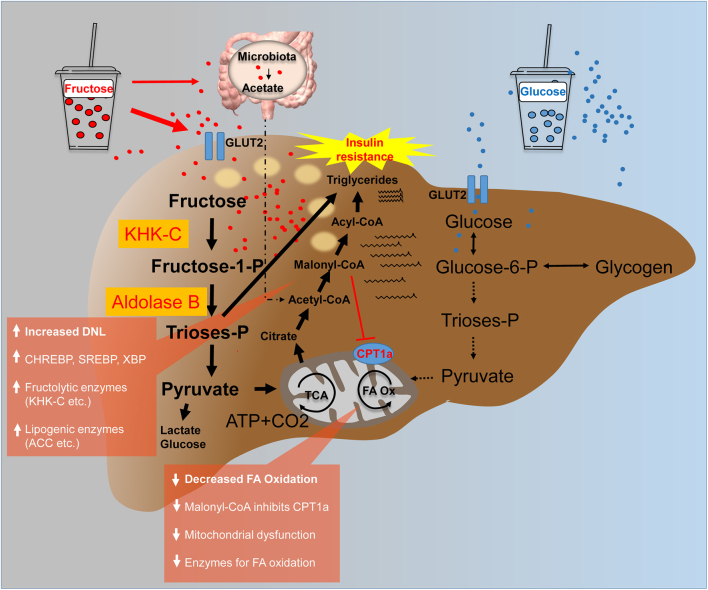

There are important differences regarding the cellular absorption and distribution of glucose and fructose (Maruhama & Macdonald 1973). Fructose is primarily absorbed via facilitated diffusion via glucose transporter 5 (GLUT5) (Burant et al. 1992), which is expressed on epithelial intestinal cells, whereas glucose is absorbed via sodium-glucose-cotransporter 1, an active transporter (Gorboulev et al. 2012). A proportion of fructose is directly metabolized into glucose in enterocytes. However, when large amounts of fructose are consumed (e.g. when consuming SSB), fructose spills over to the liver and large intestine (Jang et al. 2018) (Fig. 1). Fructose and glucose enter the circulation via GLUT5 and GLUT2, respectively (Koepsell 2020). Following that, the liver, which is the primary site of fructose metabolism, extracts a large portion of it (Mendeloff & Weichselbaum 1953). However, it can also be metabolized by the kidney, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Hesley et al.(2020) provided a thorough review of tissue-specific fructose metabolism. In contrast, glucose is taken up and metabolized by most mammalian tissues (Thorens & Mueckler 2010). The majority of glucose is taken up by the liver and muscle and stored as glycogen – processes that require insulin. Further amounts of glucose are metabolized by the brain, adipose tissue, and the kidney (Gerich 2000). Following cellular uptake, fructose and glucose are phosphorylated at different rates by specific kinases. Fructokinase is expressed as the two isoforms ketohexokinase-A (KHK-A) and KHK-C. KHK-C is primarily expressed in the liver, but it is also found in the kidney and intestines, whereas KHK-A is more widely expressed (Diggle et al. 2009). KHK-C drives hepatic fructose uptake by phosphorylating fructose at a very high rate without feedback inhibition, resulting in a flux of fructose toward the liver (Ishimoto et al. 2012) (Fig. 1). Glucose is phosphorylated by glucokinase (GK). Importantly, the phosphorylation rate of KHK is 10 times higher than that of GK. Phosphorylated fructose is cleaved into trioses and enters the glycolytic pathway. Fructose is mainly metabolized into lactic acid and converted to glucose or hepatic glycogen and lipids (Chong et al. 2007, Parks et al. 2008). Notably, fructose absorption is increased when it is co-ingested with glucose (Rumessen & Gudmand-Høyer 1986). Furthermore, animal studies have shown that consuming high amounts of fructose increases the expression of fructolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes and expands the intestinal cell surface, which improves nutrient absorption (Patel et al. 2015a, Taylor et al. 2021).

Figure 1.

A comparison of the hepatic fructose (left) and glucose (right) metabolism after consumption of high loads of sugar in the form of SSB. It is hypothesized that an increased de novo lipogenesis after fructose intake in parallel with a decreased fatty acid oxidation leads to hepatic fat deposition. ACC, acetyl-CoA-carboxylase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CPT1a, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A; FA, fatty acid; GLUT, glucose transporter; KHK-C, ketohexokinase-C; Ox, oxidation; P, phosphate; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Metabolic effects of regular sugar/fructose intake

Traditionally, easily measurable outcome parameters of known clinical significance (cardiovascular risk markers), such as fasting glucose, insulin, c-peptide, insulin sensitivity/resistance, or serum lipids, are measured for the risk assessment of dietary products regarding metabolic health. However, when metabolic health is defined just as the presence of ideal levels of these markers, fine metabolic changes may be missed. As a result, studies used more subtle outcome parameters to investigate how moderate sugar intake affects the metabolism of healthy men. Indeed, they provide evidence that consumption of SSB containing fructose in moderate amounts leads to metabolic derangements such as decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity (reflected by impaired suppression of glucose production during euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamps) (Aeberli et al. 2013), induces a shift toward a more atherogenic low-density lipoprotein (LDL) subclass distribution (Aeberli et al. 2011) in healthy men, or increases hepatic lipogenic activity (Geidl-Flueck et al. 2021).

The latter, an increased de novo lipogenesis (DNL), is supposed to be linked to various metabolic complications/perturbations. As a result, the following section focuses on metabolic interactions between dietary sugars, specifically fructose and DNL.

De novo lipogenesis in health and disease

De novo lipogenesis (DNL) converts excess dietary carbohydrates (CHO) into fatty acids (FAs). FAs are formed during this process from acetyl-CoA molecules generated directly from CHO catabolism (i.e. glycolysis or fructolysis) or acetate generated by microbiota fructose fermentation (Zhao et al. 2020). DNL necessitates the expression of lipogenic pathway enzymes by various cell types, particularly white adipocytes and hepatocytes. DNL contributes to the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. A healthy balance of hepatocyte and adipocyte DNL is essential for maintaining systemic insulin sensitivity (Song et al. 2018). The master transcription factors sterol-responsive element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) induced by CHO intake/insulin signaling and carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) stimulated by CHO intake regulate the expression of lipogenic enzymes. DNL provides FA for the structural maintenance of the cells, allows storage of energy from CHO beyond the glycogen store (thus contributing to glucose homeostasis), and regulates FA oxidation.

The process of FA synthesis in the liver has been identified as being of particular interest in the etiology of the metabolic syndrome as well as a specific feature of NAFLD (Donnelly et al. 2005, Lambert et al. 2014, Imamura et al. 2020). Clinical studies showed that DNL is increased in subjects with increased hepatic fat content (isotope approaches) (Diraison et al. 2003, Lambert et al. 2014). Furthermore, DNL was found to be positively related to intrahepatic triglyceride (TAG) levels (Diraison et al. 2003, Lambert et al. 2014) and negatively related to hepatic and whole-body insulin sensitivity (Smith et al. 2020). DNL is supposed to increase intrahepatic fat both by providing FA for TAG synthesis and by inhibiting FA oxidation promoting the re-esterification process. Importantly, accumulating intermediates (i.e. malonyl-CoA) inhibit FA import into the mitochondria and thus FA oxidation (McGarry et al. 1977, Cox et al. 2012). Furthermore, a clinical study (crossover) showed that an increase in DNL induced by a diet high in simple sugars correlates with triglyceridemia both in lean and in obese subjects (Hudgins et al. 2000). In addition, increased concentrations of DNL-related FAs (i.e. palmitate 16:0) have been linked to the metabolic syndrome in observational and interventional studies (Vessby 2003). Mechanistic in vitro studies suggest that palmitate impairs beta-cell function via ceramide formation, causing endoplasmic reticulum stress, and induces the apoptotic mitochondrial pathway (Maedler et al. 2001, Maedler et al. 2003, Cunha et al. 2008). Other studies revealed that palmitate stimulates interleukin-6 expression, a mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and vascular inflammation (Rotter et al. 2003, Staiger et al. 2004, Weigert et al. 2004, Testa et al. 2006, Korbecki & Bajdak-Rusinek 2019). Therefore, from a clinical perspective, DNL may serve as a valuable marker for the development of cardiometabolic disease beyond hepatic lipid accumulation/NAFLD.

The impact of macronutrients on DNL – insights from human intervention studies

Regarding the question of how different macronutrients impact metabolic health, early human studies compared the effects of diets with different carbohydrate and fat intake on metabolic outcomes. Later, the effects of different forms of carbohydrates were compared (e.g. simple sugars vs complex carbohydrates or different types of sugar) in studies with children or adults, with or without obesity/metabolic disease. Interventions aimed at increasing sugar/fructose consumption, e.g. by SSB intake or decreasing sugar/fructose intake by prescription of sugar/fructose restriction (Donnelly et al. 2005, Lambert et al. 2014). Finally, they all contribute to the understanding of the relationship between CHO intake and metabolic complications in general as well as the relative importance of fructose and glucose. Importantly, studies on the effects of sugar consumption on DNL are rarely comparable due to significant differences in the study populations, interventions, and/or methods used. (Studies discussed below are summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of studies measuring the effects of dietary interventions on hepatic DNL by tracer methodology.

| Intervention | Duration | Subjects | N | DNL measurement | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eucaloric liquid formula diets –Low-fat diet (10% of calories as fat and 75% as glucose polymers) –High-fat diet (40% of calories as fat and 45% as glucose polymers) |

25 days | Healthy men and women Younger adults Normal weight |

10 | Postprandial DNL labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA; linoleate dilution method |

Dietary substitution of carbohydrate (CHO) for fat stimulates the hepatic fatty acid synthesis | Hudgins et al. (1996) |

| Isocaloric diets with the same macronutrient composition –High-fructose diet (25% caloric intake; beverage) –Complex CHO (solid) diet (replaced fructose) |

9 days | Healthy men All age groups Normal weight |

8 | Postprandial DNL Labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA |

High-fructose diet is associated with higher hepatic DNL |

Schwarz et al. (2015)

|

| Daily SSB consumption (25% of required caloric intake provided as SSB; 8-week outpatient intervention with ad libitum diet, 2-week energy-balanced inpatient intervention) –Glucose-SSB –Fructose-SSB |

10 weeks | Men and women Middle-aged Overweight/obese |

32 | Postprandial DNL Labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA |

High fructose increases hepatic DNL | Stanhope et al. (2009) |

| Beverage consumption containing glucose (GLC) and/or fructose (FRC) –100:0 GLC:FRC –50:50 GLC:FRC –25:75 GLC:FRC |

Single exposure | Healthy men and women Younger adults Normal weight |

6 | Postprandial DNL Labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA |

Acute intake of fructose stimulates hepatic lipogenesis | Parks et al. (2008) |

| Daily SSB (3×0.2 L SSB/day equivalent to 80g sugar intake/day) consumption or SSB abstinence –Glucose–SSB –Fructose–SSB –Sucrose–SSB |

6 weeks | Healthy men Younger adults Normal weight |

94 | Basal DNL Labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA |

Fructose and sucrose increase basal hepatic lipogenic activity | Geidl-Flueck et al. (2021) |

| Dietary sugar restriction –Low free sugar diet –‘Usual’ diet |

8 weeks | Obese boys with NAFLD | 29 | Labeling of palmitate with 2H2O, MIDA | Dietary sugar restriction reduces hepatic DNL | Cohen et al. (2021) |

| Isocaloric fructose restriction –Starch substituted for sugar (reduced caloric intake from fructose from 12% to 4% of total energy intake) |

9 days | Children (male and female) with obesity and metabolic syndrome and habitual high sugar consumption (fructose intake >50 g/day) | 41 | Postprandial DNL Labeling of palmitate with 13C-acetate, MIDA |

Isocaloric fructose restriction decreases hepatic DNL | Schwarz et al. (2017) |

Of note, the process of hepatic DNL is assessed by applying different methods that all analyze FA bound to very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). They range from calculating FA desaturation indices to calculating the percentage of surrogate FA for newly formed FA (i.e. palmitate) in total FA to labeling newly formed FA with isotopes to calculate fractional DNL or fractional secretion rates of de novo synthesized FAs (Hellerstein et al. 1991). Measurement of DNL by isotope labeling methodology is considered the gold standard. However, it is costly and thus only appropriate for studies with small sample sizes.

Initially, it was assessed by Hudgins et al. how the fat and CHO content of a diet impacts hepatic DNL in healthy men. Subjects were randomly assigned to either an eucaloric liquid high-fat diet (40% of calories as fat and 45% as glucose polymers, n = 3) or a high-CHO diet (10% of calories as fat and 75% as glucose polymers, n = 7) for 25 days. DNL was increased in men on a high-CHO diet after 10 days, reflected as palmitate-enriched, linoleate-deficient VLDL triglycerides, and palmitate synthesis (mass isotopomer distribution analysis (MIDA) of palmitate labeled with 13C-acetate) was increased after 25 days compared to the high-fat diet (Hudgins et al. 1996).

In a later study, Schwarz et al. (2015) compared the effects of a high-fructose (25% energy content), weight-maintenance diet to those of an isocaloric diet with the same macronutrient distribution but complex carbohydrates (CCHO) substituted for fructose (crossover design, n = 8). Importantly, fructose was provided as beverages, whereas complex carbohydrates were provided as solid food. After 9 days of intervention, high-fructose intake was associated with higher fractional hepatic DNL (MIDA of palmitate labeled with 13C-acetate) compared to the diet in which fructose was replaced by CCHO (Schwarz et al. 2015). Stanhope et al. (2009) investigated the effects of glucose and fructose consumption on hepatic DNL in obese subjects after 10 weeks of consumption of glucose- or fructose-sweetened beverages providing 25% of energy requirements. Postprandial DNL was increased after fructose consumption (MIDA of palmitate labeled with 13C-acetate) (Stanhope et al. 2009).

The effects of different hexoses on hepatic DNL were investigated by Parks et al. (2008). Healthy subjects (n = 6) were challenged with sweetened beverages (85 g sugar) containing pure glucose (100:0) or mixtures of fructose and glucose (50:50 or 75:25) on three separate occasions in a random and blinded order. The beverages containing fructose stimulated DNL more potently compared with the beverages containing pure glucose (MIDA of palmitate labeled with 13C-acetate) (Parks et al. 2008).

Aside from the postprandial effect of fructose consumption on DNL which has been studied extensively, the effect of regular fructose consumption on basal hepatic lipogenic activity is of interest. Formation of new FAs requires both the expression of lipogenic enzymes and the availability of substrate (acetyl-CoA). FA synthesis, as measured by a constant infusion of glucose (as a substrate for FA synthesis) and 13C-acetate, reflects hepatic lipogenic activity, which is determined by lipogenic enzyme expression. Thus, in such a setting, differences regarding absorption rates of different sugar types do not influence the measurement. The effect of daily SSB consumption on liver lipogenic activity was studied in 94 healthy men by providing daily glucose, fructose, or sucrose-containing drinks (3×0.2 L SSB/day resulting in a sugar intake of 80g/day) in a randomized way during 6 weeks. The study with SSB consumption in a close to real-life setting showed that fructose and sucrose, but not glucose, increased the basal lipogenic activity of the liver (MIDA of palmitate labeled with 13C-acetate) (n = 94, randomized controlled trial (RCT)) as compared to a control group. This is most likely due to fructose-containing beverages causing an increase in the expression of lipogenic genes in the liver (Geidl-Flueck et al. 2021).

Further studies assessed and clarified the role of DNL in fructose-induced hypertriglyceridemia and whether physical activity prevents hypertriglyceridemia. Egli et al. examined healthy subjects (n = 8) after 4 days of either a weight-maintaining low-fructose diet (control), a high-fructose diet with low physical activity, or a high-fructose diet with high physical activity. Fasting and postprandial TAG and 13C-palmitate in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins were increased after a high-fructose diet compared to control after an oral challenge with 13C-fructose. Those parameters remained unchanged after the high-fructose/high physical activity intervention, indicating that sport protects against fructose-induced triglyceridemia. The underlying mechanism induced by physical activity (i.e. reduced DNL from fructose or improved TAG clearance) was not resolved by this study. The same authors also tested the hypothesis that exercise prevents a fructose-induced rise in VLDL triglycerides (VLDL-TGs) by decreasing fructose conversion into glucose and VLDL-TGs and fructose carbon storage into hepatic glycogen and lipids (Egli et al. 2016). Eight healthy men were placed on a weight-maintenance high-fructose diet (SSB) for 4 days before the metabolic fate of 13C-labeled fructose with or without physical activity was investigated. Exercise increased fructose oxidation. However, it did not abolish fructose conversion into glucose or did not prevent DNL (AUC of VLDL-13C palmitate). These findings imply that fructose-induced DNL occurs regardless of the degree of saturation of other fructose metabolism pathways.

So far, studies that assessed the effect of increased CHO/sugar/fructose consumption on DNL were discussed. Overall, findings from various clinical studies indicate that carbohydrates, particularly when consumed as simple sugars and in liquid form, promote hepatic lipogenesis even when maintenance dietary interventions are used. Furthermore, studies using fructose and glucose interventions revealed that fructose is a more potent inducer of hepatic lipogenesis than glucose.

In addition to these findings, some studies deal with the question of how a reduction/restriction of sugar/fructose consumption impacts DNL.

There is evidence that a general dietary sugar restriction (which also leads to a reduction in fructose intake) results in lower DNL. A link between free sugar consumption and DNL was confirmed by Cohen et al. (2021) who conducted a trial with adolescent boys suffering from NAFLD. A low-sugar diet for 8 weeks reduced DNL (and hepatic fat content) compared to their usual diet, as measured by a lower percentage of newly synthesized palmitate in plasma TAG (labeled with deuterated 2H2O) (Cohen et al. 2021) (n = 29, RCT). Similarly, Schwarz et al. (2017) demonstrated in a study with obese children that restricting sugar/fructose intake for 9 days reduced hepatic DNL (fractional DNL after a test meal containing 13C-acetate) (n = 41). In this study, dietary sugars were substituted by complex carbohydrates.

Both intervention studies that increased sugar/fructose intake and those that reduced fructose intake provide evidence that sugar/fructose intake influences hepatic DNL. Importantly, the few studies that specifically assessed the effects of different hexoses (i.e. glucose and fructose) support the hypothesis that fructose is a more potent inducer of lipogenesis than glucose (Parks et al. 2008, Geidl-Flueck et al. 2021).

Fructose vs glucose metabolism – mechanistic insights from animal studies

Insights into mechanisms underlying the differences in glucose and fructose metabolism were gained from animal studies (Maruhama & Macdonald 1973, Geidl-Flueck & Gerber 2017). Several important transcription factors control carbohydrate metabolism. We focus on the role of ChREBP (Yamashita et al. 2001) and SREBP-1 (Wang et al. 1994) in the regulation of CHO flux. They regulate glycolytic and fructolytic gene expression, as well as the expression of lipogenic genes. Glucose and fructose, to varying degrees, stimulate their expression and activity. Importantly, the expression of both transcription factors is increased in the livers of NAFLD patients (Kohjima et al. 2007, Benhamed et al. 2012).

ChREBP is most strongly expressed in the liver, white and brown adipose tissue, and also the small intestine and muscle (Iizuka et al. 2004). Lipogenic enzyme expression is reduced in mice with a genetic deletion of the ChREBP transcription factor (Iizuka et al. 2004). They display an impaired glucose tolerance as a consequence of reduced glucose disposal. ChREBP deletion shifts the flux from excess CHO to glycogen storage. It increases glycogen content in the liver and reduces the hepatic fat content. ChREBP-knockout animals are fructose intolerant due to decreased expression of fructolytic and lipogenic enzymes, resulting in death when fed high-sugar diets. Liver-specific knockout of ChREBP in mice (L-ChREBP– /–) results in reduced SREBP1c at RNA and protein levels, suggesting that both transcription factors coordinately regulate lipogenic gene expression (Linden et al. 2018).

Feeding studies revealed that fructose induces hepatic ChREBP and its targets more potently than glucose (Koo et al. 2009, Kim et al. 2016, Softic et al. 2016, Softic et al. 2017). Further, it is also activated by glycerol that is generated during fructolysis. As a result, ChREBP activation is thought to be related to hexose- and triose-phosphate levels (Kim et al. 2016).

SREBP is expressed in different isoforms. SREBP-1c induces lipogenic gene expression in response to carbohydrate feeding. SREBP1c mRNA expression is regulated by the TOR signaling pathway and the insulin signaling pathway. For full induction of SREBP-1c expression as well as for its translocation to the nucleus, hepatic insulin signaling is required (Haas et al. 2012). In mice, a high-fructose diet induces SREBP-1c expression more potently than a standard chow diet.

Furthermore, mechanistic studies provided evidence that fructose reduces hepatic FA oxidation by different mechanisms. One early in vitro study found that fructose, as a competing substrate for oxidation, inhibits long-chain FA oxidation (Prager & Ontko 1976). A further study showed that fructose feeding reduces the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and FA oxidation enzymes (Nagai et al. 2002). Furthermore, fructose feeding raises malonyl-CoA levels (which inhibits transport of FA by CPT1a into the mitochondria), causes mitochondrial dysfunction (reduced mitochondrial size and protein mass, specifically FA oxidation pathway proteins and CPT1a levels), and increases acetylation of mitochondrial proteins in mice (Softic et al. 2019).

The levels of expression of fructolytic pathway enzymes determine the relative contribution of tissues to fructose metabolism. KHK-C is considered to be a key enzyme in fructose metabolism phosphorylating fructose at a high rate as described above. KHK-C is highly expressed in hepatocytes (Diggle et al. 2009), but it is also found in the intestine, adipose tissue, kidney, and pancreas (Ishimoto et al. 2012). KHK-C knockout mice fail to metabolize fructose, leading to high-fructose concentrations in the blood and urine (Patel et al. 2015b ). Both KHK-C deletion and KHK-C blockade protect against fructose-induced metabolic perturbations (Patel et al. 2015b , Lanaspa et al. 2018, Softic et al. 2019). Deletion of the KHK-A isoform exacerbates fructose-induced metabolic syndrome probably due to an increased fructose supply to the liver (Ishimoto et al. 2012).

Clinical studies show that patients with NAFLD have increased expression of KHK-C in the liver (Ouyang et al. 2008) and that inhibiting KHK-C reduces liver fat in NAFLD (Kazierad et al. 2021).

Possible mechanisms by which sugar/fructose consumption impacts fat distribution/deposition

Ectopic fat deposition is linked to metabolic syndrome and NAFLD and is thought to be exacerbated by a high sugar intake (Ma et al. 2016). It is suggested that lipid deposition is promoted by CHO-induced DNL that reduces FA oxidation and by alterations of FA flux. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that high-sugar (fructose or sucrose) hypercaloric diets increased liver and muscle fat in comparison to eucaloric control diets (Ma et al. 2016). Of course, data from studies that used ‘close to real-life interventions’ with high but not excessive sugar intake would provide the most relevant information about the effects of sugar consumption on fat distribution in individuals. A study by Maerks et al. compared the effects of SSB containing sucrose to those of isocaloric milk and a non-caloric soft drink (one liter of drink/day for 6 months) on ectopic fat deposition. Consumption of sucrose-containing SSB for 6 months increases not only hepatic fat content but also muscle and visceral fat in obese subjects, whereas no such effects were observed in the other groups (Maersk et al. 2012). However, studies that specifically compare the impact of different types of sugars on fat distribution are scarce (Lecoultre et al. 2013). Stanhope et al. compared the effects of fructose and glucose-sweetened beverages on body fat distribution in subjects with obesity by quantification of subcutaneous, visceral, and abdominal fat. Consumption of fructose- but not glucose-sweetened beverages (providing 25% of energy requirements) for 10 weeks significantly increased visceral abdominal fat (Stanhope et al. 2009). In contrast, glucose consumption increased subcutaneous fat. Data about a fat deposition in the liver and muscle were not collected. In a later study, Schwarz et al. used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to investigate the effects of a high-fructose weight-maintenance diet on liver fat. They discovered that 9 days of a high-fructose diet (25% energy content) increased both liver fat and DNL (Schwarz et al. 2015). Different mechanisms underlying fat deposition have been suggested that implicate fructose. It is hypothesized that fructose consumption reduces FA oxidation more than glucose consumption and that fructose consumption raises cortisol levels, promoting visceral adiposity and/or lipid deposition in the liver. Cox et al. investigated the effects of SSB consumption on substrate utilization and energy expenditure in subjects with obesity. They found that the intake of fructose, but not glucose, reduced resting energy expenditure and postprandial fat oxidation while increasing postprandial carbohydrate oxidation. This finding suggests that lipid deposition may result from sparing FA from oxidation. DiNicolantonio et al. proposed that fructose plays a specific role in visceral fat deposition via glucocorticoid-mediated mechanisms (DiNicolantonio et al. 2018). Visceral fat is known to accumulate under pathological conditions where cortisol levels are increased, such as Cushing’s syndrome. Fructose consumption is thought to raise cortisol levels by promoting inflammatory processes in adipose tissue and stimulating the hypothalamus, resulting in the release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Cortisol increases the flux of FA from subcutaneous adipose tissue to visceral fat depots, impairing organ function (DiNicolantonio et al. 2018) and leading to an unfavorable fat distribution in lean individuals, i.e. a body shape described as thin outside, fat inside, which is associated with an increased risk for the metabolic syndrome (DiNicolantonio et al. 2018). Taken together, studies provide evidence that fructose and sucrose consumption promote ectopic fat deposition associated with an increased risk for metabolic disease and cardiovascular events (Gruzdeva et al. 2018). This is most likely due to a simultaneous increase in DNL and decrease in FA oxidation, but it could also be due to increased FA flux from subcutaneous adipose tissue to other tissues (visceral fat and the liver).

Conclusions

A high intake of free sugar as SSB increases the risk of obesity, cardiometabolic diseases, and NAFLD. A central role must be attributed to fructose in the development of these diseases. It is not only a strong inducer of DNL, but it is also a known cause of ectopic fat deposition by reducing fat oxidation and increasing FA flux to visceral fat and the liver. Most importantly, fructose-specific effects occur independently from overfeeding in healthy subjects. There are several mechanisms by which high-fructose consumers increase fructose absorption and catabolism in the liver, exacerbating the metabolic effects. Sugar/fructose consumption should be reduced to avoid these unfavorable metabolic adaptations.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests regarding this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Heuberg foundation.

Author contribution statement

Bettina Geidl-Flueck and Philipp Gerber wrote and revised the manuscript.

References

- Aeberli I, Gerber PA, Hochuli M, Kohler S, Haile SR, Gouni-Berthold I, Berthold HK, Spinas GA, Berneis K.2011Low to moderate sugar-sweetened beverage consumption impairs glucose and lipid metabolism and promotes inflammation in healthy young men: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 94479–485. ( 10.3945/ajcn.111.013540) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeberli I, Hochuli M, Gerber PA, Sze L, Murer SB, Tappy L, Spinas GA, Berneis K.2013Moderate amounts of fructose consumption impair insulin sensitivity in healthy young men: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 36150–156. ( 10.2337/dc12-0540) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamed F, Denechaud PD, Lemoine M, Robichon C, Moldes M, Bertrand-Michel J, Ratziu V, Serfaty L, Housset C, Capeau Jet al. 2012The lipogenic transcription factor ChREBP dissociates hepatic steatosis from insulin resistance in mice and humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1222176–2194. ( 10.1172/JCI41636) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau DM, Malone DC, Raebel MA, Fishman PA, Nichols GA, Feldstein AC, Boscoe AN, Ben-Joseph RH, Magid DJ, Okamoto LJ.2009Health care utilization and costs by metabolic syndrome risk factors. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders 7305–314. ( 10.1089/met.2008.0070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burant CF, Takeda J, Brot-Laroche E, Bell GI, Davidson NO.1992Fructose transporter in human spermatozoa and small intestine is GLUT5. Journal of Biological Chemistry 26714523–14526. ( 10.1016/S0021-9258(1842067-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H Wang J Li Z Lam CWK Xiao Y Wu Q & Zhang W. 2019Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has a dose-dependent effect on the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16. ( 10.3390/ijerph16122192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MF, Fielding BA, Frayn KN.2007Mechanisms for the acute effect of fructose on postprandial lipemia. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 851511–1520. ( 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1511) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CC, Li KW, Alazraki AL, Beysen C, Carrier CA, Cleeton RL, Dandan M, Figueroa J, Knight-Scott J, Knott CJet al. 2021Dietary sugar restriction reduces hepatic de novo lipogenesis in adolescent boys with fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 131. ( 10.1172/JCI150996) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Graham JL, Hatcher B, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Berglund L, McGahan JP, Havel PJet al. 2012Consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages for 10 weeks reduces net fat oxidation and energy expenditure in overweight/obese men and women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 66201–208. ( 10.1038/ejcn.2011.159) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha DA, Hekerman P, Ladrière L, Bazarra-Castro A, Ortis F, Wakeham MC, Moore F, Rasschaert J, Cardozo AK, Bellomo Eet al. 2008Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Journal of Cell Science 1212308–2318. ( 10.1242/jcs.026062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco L Fulgoni VL Gaine PC Scott MO & Ricciuto L. 2022Trends in added sugars intake and sources among U.S. adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–2018. Frontiers in Nutrition 9897952. ( 10.3389/fnut.2022.897952) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle CP Shires M Leitch D Brooke D Carr IM Markham AF Hayward BE Asipu A & Bonthron DT. 2009Ketohexokinase: expression and localization of the principal fructose-metabolizing enzyme. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 57763–774. ( 10.1369/jhc.2009.953190) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNicolantonio JJ, Mehta V, Onkaramurthy N, O'Keefe JH.2018Fructose-induced inflammation and increased cortisol: a new mechanism for how sugar induces visceral adiposity. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 613–9. ( 10.1016/j.pcad.2017.12.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diraison F, Moulin P, Beylot M.2003Contribution of hepatic de novo lipogenesis and reesterification of plasma non esterified fatty acids to plasma triglyceride synthesis during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes and Metabolism 29478–485. ( 10.1016/s1262-3636(0770061-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ.2005Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1151343–1351. ( 10.1172/JCI23621) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli L, Lecoultre V, Cros J, Rosset R, Marques AS, Schneiter P, Hodson L, Gabert L, Laville M, Tappy L.2016Exercise performed immediately after fructose ingestion enhances fructose oxidation and suppresses fructose storage1. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 103348–355. ( 10.3945/ajcn.115.116988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisberg M, Kovalskys I, Gómez G, Rigotti A, Sanabria LYC, García MCY, Torres RGP, Herrera-Cuenca M, Zimberg IZ, Koletzko Bet al. 2018Total and added sugar intake: assessment in eight Latin American countries. Nutrients 10. ( 10.3390/nu10040389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geidl-Flueck B & Gerber PA. 2017Insights into the hexose liver metabolism-glucose versus fructose. Nutrients 9. ( 10.3390/nu9091026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geidl-Flueck B, Hochuli M, Németh Á, Eberl A, Derron N, Köfeler HC, Tappy L, Berneis K, Spinas GA, Gerber PA.2021Fructose- and sucrose- but not glucose-sweetened beverages promote hepatic de novo lipogenesis: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Hepatology 7546–54. ( 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.02.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerich JE.2000Physiology of glucose homeostasis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2345–350. ( 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00085.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorboulev V, Schürmann A, Vallon V, Kipp H, Jaschke A, Klessen D, Friedrich A, Scherneck S, Rieg T, Cunard Ret al. 2012Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes 61187–196. ( 10.2337/db11-1029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzdeva O, Borodkina D, Uchasova E, Dyleva Y, Barbarash O.2018Localization of fat depots and cardiovascular risk. Lipids in Health and Disease 17 218. ( 10.1186/s12944-018-0856-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JT, Miao J, Chanda D, Wang Y, Zhao E, Haas ME, Hirschey M, Vaitheesvaran B, Farese RV, Kurland IJet al. 2012Hepatic insulin signaling is required for obesity-dependent expression of SREBP-1c mRNA but not for feeding-dependent expression. Cell Metabolism 15873–884. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein MK, Christiansen M, Kaempfer S, Kletke C, Wu K, Reid JS, Mulligan K, Hellerstein NS, Shackleton CH.1991Measurement of de novo hepatic lipogenesis in humans using stable isotopes. Journal of Clinical Investigation 871841–1852. ( 10.1172/JCI115206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsley RN, Moreau F, Gupta MK, Radulescu A, DeBosch B, Softic S.2020Tissue-specific fructose metabolism in obesity and diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports 20 64. ( 10.1007/s11892-020-01342-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins LC, Hellerstein M, Seidman C, Neese R, Diakun J, Hirsch J.1996Human fatty acid synthesis is stimulated by a eucaloric low fat, high carbohydrate diet. Journal of Clinical Investigation 972081–2091. ( 10.1172/JCI118645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins LC, Hellerstein MK, Seidman CE, Neese RA, Tremaroli JD, Hirsch J.2000Relationship between carbohydrate-induced hypertriglyceridemia and fatty acid synthesis in lean and obese subjects. Journal of Lipid Research 41595–604. ( 10.1016/S0022-2275(2032407-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka K Bruick RK Liang G Horton JD & Uyeda K. 2004Deficiency of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) reduces lipogenesis as well as glycolysis. PNAS 1017281–7286. ( 10.1073/pnas.0401516101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, Forouhi NG.2015Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 351 h3576. ( 10.1136/bmj.h3576) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura F, Fretts AM, Marklund M, Ardisson Korat AV, Yang WS, Lankinen M, Qureshi W, Helmer C, Chen TA, Virtanen JKet al. 2020Fatty acids in the de novo lipogenesis pathway and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLOS Medicine 17 e1003102. ( 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimoto T, Lanaspa MA, Le MT, Garcia GE, Diggle CP, Maclean PS, Jackman MR, Asipu A, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Kosugi Tet al. 2012Opposing effects of fructokinase C and A isoforms on fructose-induced metabolic syndrome in mice. PNAS 1094320–4325. ( 10.1073/pnas.1119908109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, Hui S, Lu W, Cowan AJ, Morscher RJ, Lee G, Liu W, Tesz GJ, Birnbaum MJ, Rabinowitz JD.2018The small intestine converts dietary fructose into glucose and organic acids. Cell Metabolism 27351–361.e3. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, Nadeau KJ, Green M, Roncal C, Nakagawa T, Kuwabara M, Sato Y, Kang DHet al. 2018Fructose and sugar: a major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology 681063–1075. ( 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, Sacks F, Steffen LM, Wylie-Rosett J. & American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention 2009Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 1201011–1020. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay Parker M.2010High fructose corn syrup: production, uses and public health concerns SaVCN. Biotechnology and Molecular Biology Reviews 571–78. ( 10.5897/BMBR2010.0009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazierad DJ, Chidsey K, Somayaji VR, Bergman AJ, Birnbaum MJ, Calle RA.2021Inhibition of ketohexokinase in adults with NAFLD reduces liver fat and inflammatory markers: a randomized phase 2 trial. Med 2800–813.e3. ( 10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Krawczyk SA, Doridot L, Fowler AJ, Wang JX, Trauger SA, Noh HL, Kang HJ, Meissen JK, Blatnik Met al. 2016ChREBP regulates fructose-induced glucose production independently of insulin signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1264372–4386. ( 10.1172/JCI81993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmietowicz Z.2012Countries that use large amounts of high fructose corn syrup have higher rates of type 2 diabetes. BMJ 345 e7994. ( 10.1136/bmj.e7994) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H.2020Glucose transporters in the small intestine in health and disease. Pflugers Archiv 4721207–1248. ( 10.1007/s00424-020-02439-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohjima M, Enjoji M, Higuchi N, Kato M, Kotoh K, Yoshimoto T, Fujino T, Yada M, Yada R, Harada Net al. 2007Re-evaluation of fatty acid metabolism-related gene expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 20351–358. ( 10.3892/ijmm.20.3.351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo HY, Miyashita M, Simon Cho BH, Nakamura MT.2009Replacing dietary glucose with fructose increases ChREBP activity and SREBP-1 protein in rat liver nucleus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 390285–289. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbecki J, Bajdak-Rusinek K.2019The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflammation Research 68915–932. ( 10.1007/s00011-019-01273-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Ramos-Roman MA, Browning JD, Parks EJ.2014Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 146726–735. ( 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaspa MA, Andres-Hernando A, Orlicky DJ, Cicerchi C, Jang C, Li N, Milagres T, Kuwabara M, Wempe MF, Rabinowitz JDet al. 2018Ketohexokinase C blockade ameliorates fructose-induced metabolic dysfunction in fructose-sensitive mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1282226–2238. ( 10.1172/JCI94427) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecoultre V, Egli L, Carrel G, Theytaz F, Kreis R, Schneiter P, Boss A, Zwygart K, Lê KA, Bortolotti Met al. 2013Effects of fructose and glucose overfeeding on hepatic insulin sensitivity and intrahepatic lipids in healthy humans. Obesity 21782–785. ( 10.1002/oby.20377) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH.2010The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology and Hepatology 7251–264. ( 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.41) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AG, Li S, Choi HY, Fang F, Fukasawa M, Uyeda K, Hammer RE, Horton JD, Engelking LJ, Liang G.2018Interplay between ChREBP and SREBP-1c coordinates postprandial glycolysis and lipogenesis in livers of mice. Journal of Lipid Research 59475–487. ( 10.1194/jlr.M081836) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwik MRH.2021Assessment and evaluation of the intake of sugars in European countries. Applied Sciences 11 11983. ( 10.3390/app112411983) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Karlsen MC, Chung M, Jacques PF, Saltzman E, Smith CE, Fox CS, McKeown NM.2016Potential link between excess added sugar intake and ectopic fat: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Reviews 7418–32. ( 10.1093/nutrit/nuv047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K, Oberholzer J, Bucher P, Spinas GA, Donath MY.2003Monounsaturated fatty acids prevent the deleterious effects of palmitate and high glucose on human pancreatic β-cell turnover and function. Diabetes 52726–733. ( 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.726) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K, Spinas GA, Dyntar D, Moritz W, Kaiser N, Donath MY.2001Distinct effects of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids on beta-cell turnover and function. Diabetes 5069–76. ( 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.69) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, Ringgaard S, Chabanova E, Thomsen H, Pedersen SB, Astrup A, Richelsen B.2012Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: a 6-mo randomized intervention study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 95283–289. ( 10.3945/ajcn.111.022533) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik VS, Hu FB.2022The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology 18205–218. ( 10.1038/s41574-021-00627-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruhama Y, Macdonald I.1973Incorporation of orally administered glucose-U-14C and fructose-U-14C into the triglyceride of liver, plasma, and adipose tissue of rats. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 221205–1215. ( 10.1016/0026-0495(7390208-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry JD, Mannaerts GP, Foster DW.1977A possible role for malonyl-CoA in the regulation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 60265–270. ( 10.1172/JCI108764) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendeloff AI, Weichselbaum TE.1953Role of the human liver in the assimilation of intravenously administered fructose. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 2450–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JB.2010Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the hepatic consequence of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 69211–220. ( 10.1017/S0029665110000030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz HR.1970Ratio scales of sugar sweetness. Perception and Psychophysics 7315–320. ( 10.3758/BF03210175) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Nishio Y, Nakamura T, Maegawa H, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A.2002Amelioration of high fructose-induced metabolic derangements by activation of PPARalpha. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 282E1180–E1190. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00471.2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Lontchi-Yimagou E, Nkeck JR, Nyaga UF, Ngouo AT, Tounouga DN, Tianyi FL, Foka AJ, Ndoadoumgue ALet al. 2022Global, regional, and country estimates of metabolic syndrome burden in children and adolescents in 2020: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet. Child and Adolescent Health 6158–170. ( 10.1016/S2352-4642(2100374-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, McCall S, Bruchette JL, Diehl AM, Johnson RJ, Abdelmalek MF.2008Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology 48993–999. ( 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, Dingfelder CS.2008Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. Journal of Nutrition 1381039–1046. ( 10.1093/jn/138.6.1039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C Douard V Yu S Tharabenjasin P Gao N & Ferraris RP. 2015aFructose-induced increases in expression of intestinal fructolytic and gluconeogenic genes are regulated by GLUT5 and KHK. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 309R499–R509. ( 10.1152/ajpregu.00128.2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C Sugimoto K Douard V Shah A Inui H Yamanouchi T & Ferraris RP. 2015bEffect of dietary fructose on portal and systemic serum fructose levels in rats and in KHK-/- and GLUT5-/- mice. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 309G779–G790. ( 10.1152/ajpgi.00188.2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager GN, Ontko JA.1976Direct effects of fructose metabolism on fatty acid oxidation in a recombined rat liver mitochondria-high speed supernatant system. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 424386–395. ( 10.1016/0005-2760(7690028-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, Swain MG, Congly SE, Kaplan GG, Shaheen AA.2022The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Gastroenterology and Hepatology 7851–861. ( 10.1016/S2468-1253(2200165-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U.2003Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. Journal of Biological Chemistry 27845777–45784. ( 10.1074/jbc.M301977200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Høyer E.1986Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides. Gut 271161–1168. ( 10.1136/gut.27.10.1161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahota AK Shapiro WL Newton KP Kim ST Chung J & Schwimmer JB. 2020Incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: 2009–2018. Pediatrics 146. ( 10.1542/peds.2020-0771) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saklayen MG.2018The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Current Hypertension Reports 20 12. ( 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Noworolski SM, Erkin-Cakmak A, Korn NJ, Wen MJ, Tai VW, Jones GM, Palii SP, Velasco-Alin M, Pan Ket al. 2017Effects of dietary fructose restriction on liver fat, De Novo Lipogenesis, and Insulin Kinetics in Children With Obesity. Gastroenterology 153743–752. ( 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Noworolski SM, Wen MJ, Dyachenko A, Prior JL, Weinberg ME, Herraiz LA, Tai VW, Bergeron N, Bersot TPet al. 2015Effect of a high-fructose weight-maintaining diet on lipogenesis and liver fat. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1002434–2442. ( 10.1210/jc.2014-3678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekkarie A, Welsh JA, Northstone K, Stein AD, Ramakrishnan U, Vos MB.2021Associations between free sugar and sugary beverage intake in early childhood and adult NAFLD in a population-based UK cohort. Children (Basel) 8. ( 10.3390/children8040290) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Saldivar SO.2016Maize: foods from maize. In Reference Module in Food Science [epub]. ( 10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.00126-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Lim S, Andrews KG, Engell RE, Ezzati M, Mozaffarian D. & Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE) 2015Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: a systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS One 10 e0124845. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0124845) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GI, Shankaran M, Yoshino M, Schweitzer GG, Chondronikola M, Beals JW, Okunade AL, Patterson BW, Nyangau E, Field Tet al. 2020Insulin resistance drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1301453–1460. ( 10.1172/JCI134165) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S, Cohen DE, Kahn CR.2016Role of dietary fructose and hepatic de novo lipogenesis in fatty liver disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 611282–1293. ( 10.1007/s10620-016-4054-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S, Gupta MK, Wang GX, Fujisaka S, O'Neill BT, Rao TN, Willoughby J, Harbison C, Fitzgerald K, Ilkayeva Oet al. 2017Divergent effects of glucose and fructose on hepatic lipogenesis and insulin signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1274059–4074. ( 10.1172/JCI94585) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S, Meyer JG, Wang GX, Gupta MK, Batista TM, Lauritzen HPMM, Fujisaka S, Serra D, Herrero L, Willoughby Jet al. 2019Dietary sugars alter hepatic fatty acid oxidation via transcriptional and post-translational modifications of mitochondrial proteins. Cell Metabolism 30735–753.e4. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z Xiaoli AM & Yang F. 2018Regulation and metabolic significance of de novo lipogenesis in adipose tissues. Nutrients 10. ( 10.3390/nu10101383) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger H, Staiger K, Stefan N, Wahl HG, Machicao F, Kellerer M, Häring HU.2004Palmitate-induced interleukin-6 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Diabetes 533209–3216. ( 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, Hatcher B, Cox CL, Dyachenko A, Zhang Wet al. 2009Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1191322–1334. ( 10.1172/JCI37385) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappy L, Lê KA.2010Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiological Reviews 9023–46. ( 10.1152/physrev.00019.2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SR, Ramsamooj S, Liang RJ, Katti A, Pozovskiy R, Vasan N, Hwang SK, Nahiyaan N, Francoeur NJ, Schatoff EMet al. 2021Dietary fructose improves intestinal cell survival and nutrient absorption. Nature 597263–267. ( 10.1038/s41586-021-03827-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Morenga LA, Howatson AJ, Jones RM, Mann J.2014Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 10065–79. ( 10.3945/ajcn.113.081521) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa R, Olivieri F, Bonfigli AR, Sirolla C, Boemi M, Marchegiani F, Marra M, Cenerelli S, Antonicelli R, Dolci Aet al. 2006Interleukin-6-174 G > C polymorphism affects the association between IL-6 plasma levels and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 71299–305. ( 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.07.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorens B, Mueckler M.2010Glucose transporters in the 21st Century. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 298E141–E145. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00712.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessby B.2003Dietary fat, fatty acid composition in plasma and the metabolic syndrome. Current Opinion in Lipidology 1415–19. ( 10.1097/00041433-200302000-00004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Sato R, Brown MS, Hua X, Goldstein JL.1994SREBP-1, a membrane-bound transcription factor released by sterol-regulated proteolysis. Cell 7753–62. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(9490234-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert C, Brodbeck K, Staiger H, Kausch C, Machicao F, Häring HU, Schleicher ED.2004Palmitate, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induces the expression of interleukin-6 in human myotubes through proteasome-dependent activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Journal of Biological Chemistry 27923942–23952. ( 10.1074/jbc.M312692200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2015Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. (available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H Takenoshita M Sakurai M Bruick RK Henzel WJ Shillinglaw W Arnot D & Uyeda K. 2001A glucose-responsive transcription factor that regulates carbohydrate metabolism in the liver. PNAS 989116–9121. ( 10.1073/pnas.161284298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Zhu Y, Malik V, Li X, Peng X, Zhang FF, Shan Z, Liu L.2021Intake of sugar-sweetened and low-calorie sweetened beverages and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Advances in Nutrition 1289–101. ( 10.1093/advances/nmaa084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Jang C, Liu J, Uehara K, Gilbert M, Izzo L, Zeng X, Trefely S, Fernandez S, Carrer Aet al. 2020Dietary fructose feeds hepatic lipogenesis via microbiota-derived acetate. Nature 579586–591. ( 10.1038/s41586-020-2101-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a