Abstract

In this post-hoc analysis of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial, we evaluated the prognostic role of anemia in adverse cardiovascular (CV) outcomes in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). We defined anemia as hemoglobin of <12 g/dl in females and <13 g/dl in males. The primary outcome was a composite of CV mortality, aborted cardiac arrest (ACA), or hospitalization for heart failure. Secondary outcomes were individual components of the primary outcome, all-cause, CV and non-CV mortality, cause-specific CV and non-CV mortality, all-cause hospitalization and HF hospitalization, myocardial infarction, and stroke during follow up. We conducted time-to-event with Cox proportional hazards models and Poisson regression analyses to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) and the incident rates, respectively. Among 1,748 patients from TOPCAT-Americas, patients with anemia had a 52% higher risk of the primary outcome (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.27, 1.83, p<0.05) during a median follow up of 2.4 years (interquartile range 1.4–3.9 years). These patients were also at higher risk of all-cause and CV mortality (HR 1.40 and 1.47, respectively, p for both <0.05) with no difference in non-CV mortality (p>0.05) as compared to those without anemia. Among CV causes, patients with anemia had a higher risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD)/ACA and presumed CV death (HR 1.67 and 1.83, respectively, p<0.05 for both) with no difference in death due to pump failure (p>0.05). Among non-CV causes, patients with anemia had a higher risk of death due to malignancy (HR 2.61, p<0.05). Patients with anemia also had a higher risk of all-cause and HF-related hospitalizations (HR 1.26 and 1.56, respectively, p<0.05 for both). There was no difference in the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke between the 2 groups. In conclusion, patients with HFpEF and anemia have a higher risk of mortality and hospitalizations. Anemia is a significant risk factor for SCD/ACA, death due to presumed CV causes and malignancy among those with HFpEF.

Keywords: Anemia, Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction, Sudden Cardiac Death, Heart Failure

Introduction

With the increase in the prevalence of heart failure (HF), there has been a proportionate rise in the number of patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1 While the morbidity and mortality associated with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has been reduced with many evidence-based therapies, few currently available treatment strategies have shown clinical benefit in HFpEF.2–6 Comorbidities are a major driver of the morbidity and mortality burden in HFpEF.7 Anemia is one such co-morbidity that is independently associated with adverse outcomes, such that HFpEF patients with anemia are at a higher risk of all-cause, cardiovascular (CV), and non-CV mortality.7–9 However, there is limited data on cause-specific mortality and hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF and anemia. The urgency of these questions is reiterated by the lack of available treatment strategies for HFpEF2–6, where anemia may be a promising target for intervention.9,10 We evaluated the independent association between anemia and adverse outcomes in patients with HFpEF enrolled in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. We hypothesized that patients with HFpEF and anemia have a higher rate of adverse outcomes.

Methods

The TOPCAT trial is a randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect of spironolactone treatment in patients with HFpEF.6,11 There were no exclusion criteria on the basis of hemoglobin. The full details of the study population have been published previously.11

The study protocol was approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board (IRB) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (NHLBI-BioLINCC). For our analysis, we excluded patients enrolled in Russia and Georgia due to prior concerns regarding the validity of HFpEF diagnosis12 and management13 of patients enrolled in these sites. The current analysis was conducted among those enrolled from the United States of America, Canada, Argentina, and Brazil and constituted the ‘TOPCAT-Americas’.

The hemoglobin at the time of enrollment was used for this investigation. Anemia was defined using the World Health Organization definition-hemoglobin <12 g/dl for females and <13 g/dl for males.14

The primary outcome for this study was the trial defined composite of CV mortality, aborted cardiac arrest (ACA), or hospitalization for the management of HF during the follow-up. Secondary outcomes were individual components of the primary outcome, all-cause mortality, non-CV mortality, cause-specific CV and non-CV mortality, all-cause and HF hospitalizations, myocardial infarction, and stroke during follow up. A blinded clinical events committee adjudicated all clinical outcomes in TOPCAT. The adjudication process has been described previously.6,11

We represent continuous variables as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical variables were represented as counts with proportions. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and chi-squared tests to identify the differences in baseline characteristics in continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

We checked the Cox proportional hazard assumption using Schoenfeld residuals and used Cox proportional hazards models to compare the risk of outcomes by anemia status. For the primary outcome and its components, non-CV mortality, any and all-cause hospitalizations, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards models while controlling for the following covariates- age, gender, race, ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, estimated glomerular filtration rate, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, stroke, New York Heart Association class, orthopnea, peripheral arterial disease, treatment with spironolactone, current smoker, left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF), serum albumin and ‘coronary artery disease’ a composite of prior angina, prior myocardial infarction, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, or prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Due to the low number of cause-specific mortality events, the hazard ratio (HR) was adjusted for only age, gender, and race. We calculated the HR for adverse outcomes by using hemoglobin as a continuous variable. We also checked for interaction between hemoglobin and gender, as well as hemoglobin and treatment (spironolactone vs placebo) on the risk of the primary outcome using Poisson regression analyses. Poisson regression analyses were to estimate incident rates (IR, per 100 person-years) of all outcomes. We accounted for non-linearity with spline-based modeling to optimize the Akaike information criterion.

To understand the mechanisms of the adverse prognostic role of anemia in HFpEF, we performed a linear regression to estimate the correlation of circulating biomarkers (BNP and NT-proBNP) and echocardiographic parameters (left atrial end-diastolic volume, LVEF, septal and lateral E/e’ ratio) with hemoglobin. Values of BNP and NT-proBNP were log-transformed as they did not have a normal distribution.

There was no funding source for the current investigation. The funders of TOPCAT had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. N.S.B. and K.G. had full access to all study data.

Results

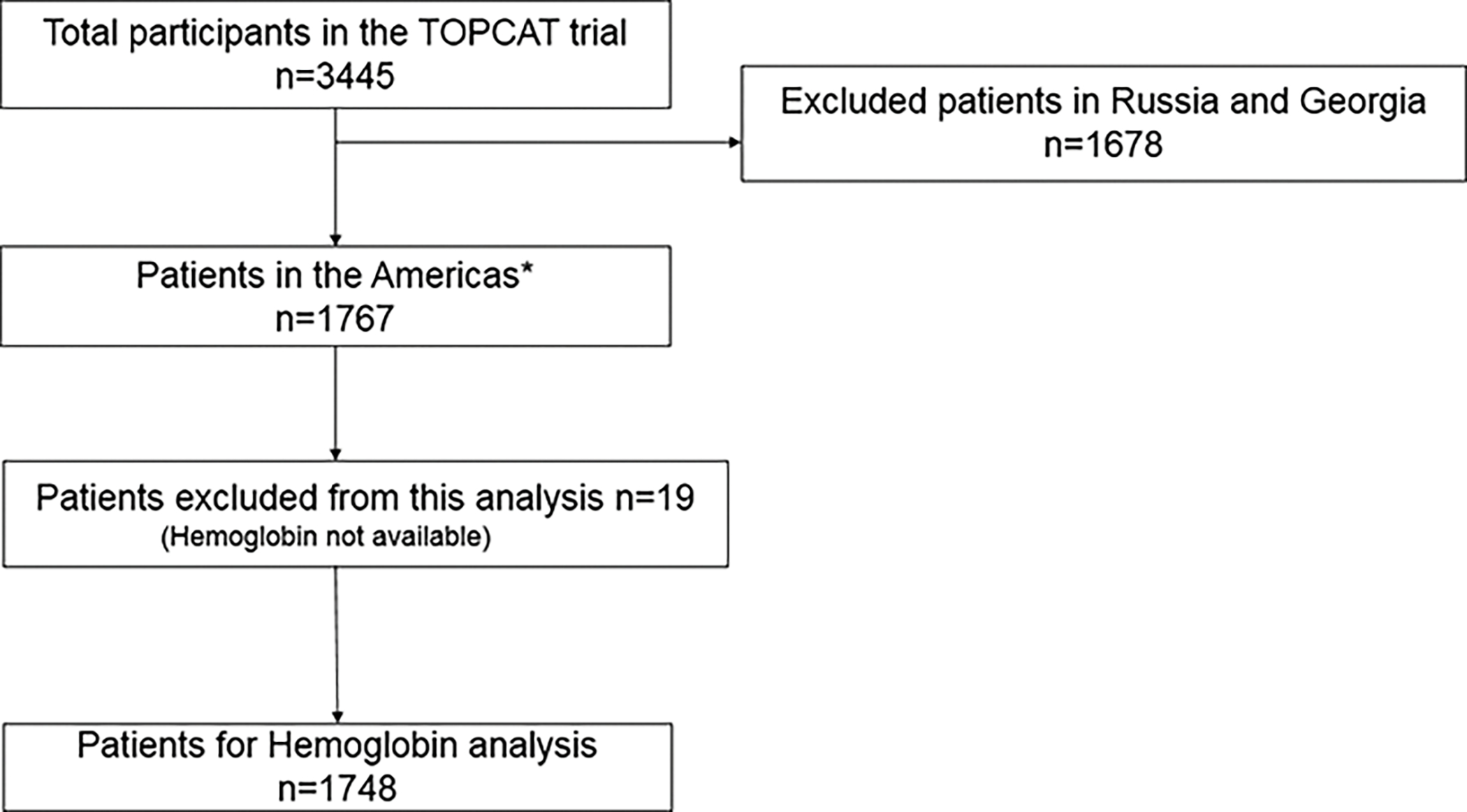

Of the total 3,445 patients with HFpEF included in the TOPCAT, 1,767 (51%) were enrolled in the Americas (United States, Argentina, Brazil, and Canada). Among them, 19 patients (<1%) did not have hemoglobin recorded at baseline and were excluded from this analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the assembled cohort. The median age was 72 years (IQR 64–79), with equal representation of men and women. The majority of the subjects (83%) were white. There was a high burden of co-morbidities like hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity amongst the study population. There were 716 (41%) patients with anemia in the entire cohort (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Flow Diagram for Subject Selection.

*TOPCAT-Americas included patients from the United States of America, Canada, Argentina, and Brazil.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by Anemia

| Anemia |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOPCAT Americas (n=1748) |

Yes (n=716) |

No (n=1032) |

P-value | |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at randomization (years) | 72 (64, 79) | 73 (64, 79) | 72 (64, 79) | 0.160 |

| Women | 872 (49.9%) | 326 (45.5%) | 546 (52.9%) | 0.002 |

| Black race | 294 (16.8%) | 152 (21.2%) | 142 (13.8%) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Features of Heart Failure | ||||

| Orthopnea | 539 (30.8%) | 259 (36.2%) | 280 (27.1%) | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class III & IV | 611 (35.0%) | 291 (40.8%) | 320 (31.1%) | <0.001 |

| Rales | 288 (16.5%) | 118 (16.5%) | 170 (16.5%) | 0.790 |

| JVP elevated | 297 (17.0%) | 139 (19.4%) | 158 (15.3%) | 0.066 |

| Peripheral Edema | 1,249 (71.5%) | 537 (75.0) | 712 (69.0) | 0.018 |

| Clinical Parameters and Co-morbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 1,572 (90.0%) | 648 (90.6%) | 924 (89.5%) | 0.450 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 780 (44.6%) | 408 (57.1%) | 372 (36.0%) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1,237 (70.8%) | 530 (74.1%) | 707 (68.5%) | 0.011 |

| Obesity | 1,129 (64.6%) | 477 (66.6%) | 652 (63.2%) | 0.140 |

| Current smoking | 115 (6.6%) | 39 (5.5%) | 76 (7.4%) | 0.110 |

| Stroke | 155 (8.9%) | 66 (9.2%) | 89 (8.6%) | 0.660 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 738 (42.2%) | 275 (38.5%) | 463 (44.9%) | 0.008 |

| COPD | 289 (16.5%) | 117 (16.4%) | 172 (16.7%) | 0.870 |

| Coronary artery disease | 807 (46.2%) | 372 (52.0%) | 435 (42.2%) | <0.001 |

| Angina pectoris | 481 (27.5%) | 207 (29.0%) | 274 (26.6%) | 0.270 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 358 (20.5%) | 172 (24.1%) | 186 (18.0%) | 0.002 |

| Prior CABG | 333 (19.1%) | 180 (25.2%) | 153 (14.8%) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 343 (19.6%) | 163 (22.8%) | 180 (17.4%) | 0.006 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 205 (11.7%) | 94 (13.1%) | 111 (10.8%) | 0.130 |

| Enrollment strata: Previous Hospitalization | 967 (55.3%) | 451 (63.0%) | 516 (50.0%) | <0.001 |

| Treatment with spironolactone | 878 (50.2%) | 366 (51.1%) | 512 (49.6%) | 0.540 |

| Anthropometric Parameters | ||||

| Height (m) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8) | 0.031 |

| Weight (kg) | 90.7 (76.0, 108.9) | 93.4 (76.0, 111.1) | 89.0 (75.7, 107.0) | 0.027 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.8 (27.9, 38.4) | 33.1 (28.0, 38.8) | 32.5 (27.9, 38.0) | 0.110 |

| Hemodynamic measures | ||||

| Heart rate (/minute) | 68 (61, 76) | 68 (60, 75) | 68 (61, 76) | 0.092 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129 (118, 138) | 130 (117, 140) | 128 (118, 138) | 0.220 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70 (62, 80) | 69 (60, 78) | 73 (64, 80) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic Parameters * | ||||

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 51 (57, 65) | 51 (57, 65) | 51 (57, 65) | 0.750 |

| LV GLS (%) | -15.5 (-18.2, -13.2) | -15.8 (-18.4, -13.2) | -15.3 (-18.0, -13.0) | 0.237 |

| LV end diastolic volume (ml) | 89.4 (72.4, 114.5) | 96.4 (77.0, 116.9) | 86.3 (70.5, 112.4) | 0.003 |

| LV end systolic volume (ml) | 35.0 (26.0, 46.9) | 36.4 (27.8, 48.7) | 34.1 (25.4, 46.0) | 0.038 |

| E/e’ septal ratio | 15.3 (11.1, 19.9) | 16.0 (12.7, 20.8) | 14.8 (10.1, 19.8) | 0.037 |

| E/e’ lateral ratio | 11.1 (8.2, 15.3) | 12.2 (8.9, 15.9) | 10.3 (7.4, 14.3) | 0.003 |

| Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| BNP (pg/ml) | 258 (150, 447) | 273 (163, 518) | 249 (146, 418) | 0.037 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) | 964 (553, 2017) | 1140 (599, 2356) | 912 (539, 1720) | 0.076 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.8 (11.7, 14.0) | 11.5 (10.8, 12.0) | 13.8 (13.0, 14.6) | <0.001 |

| Leukocyte count (*1000cells/μl) | 7.1 (5.9,8.5) | 7.0 (5.8, 8.5) | 7.1 (5.9, 8.6) | 0.190 |

| Platelet count (*1000cells/μl) | 218 (181, 264) | 220 (179, 269) | 217 (183, 262) | 0.670 |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 61 (48.9, 76.5) | 57.4 (45.7, 72.3) | 63.8 (51.7, 78.4) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (3.6, 4.2) | 3.8 (3.4, 4.1) | 4.0 (3.7, 4.3) | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 140 (138, 142) | 140 (138, 142) | 140.0 (138, 142) | 0.085 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.5) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.5) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.5) | 0.390 |

| Medications | ||||

| Diuretic | 1,558 (89.2%) | 654 (91.3%) | 904 (87.7%) | 0.015 |

| ACEi /ARB | 1,379 (78.9%) | 580 (81.0%) | 799 (77.5%) | 0.077 |

| Beta blocker | 1,372 (78.5%) | 591 (82.5%) | 751 (75.8%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 673 (38.5%) | 289 (40.4%) | 384 (37.2%) | 0.190 |

| Aspirin | 1,015 (58.1%) | 433 (60.5%) | 582 (56.5%) | 0.094 |

| Statin | 1,136 (65.0%) | 511 (71.4%) | 625 (60.6%) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting nitrate | 301 (17.2%) | 150 (20.9%) | 151 (14.6%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 588 (33.7%) | 203 (28.4%) | 385 (37.3%) | <0.001 |

Among those enrolled in the TOPCAT Echo Study in core laboratory (n=587)

Among those enrolled via BNP stratum, n=590 for BNP and n=356 for NT-proBNP

p-values are from Chi-squared test for categorical and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous comparisons

Data are represented as median (25th to 75th percentile), number (percentage). Anemia defined as hemoglobin concentration <12 g/dl in women and <13 g/dl in men. Chronic kidney disease defined as eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2. GFR estimated by the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) 4-component study equation and CAD was defined as a composite of angina pectoris, previous MI, PCI, or CABG.

ACEi = Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = Angiotensin receptor blocker; E= Peak velocity blood flow during early diastole; e’= early diastolic mitral annular velocity; JVP = Jugular venous pressure; NYHA = New York Heart Association; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; GLS= Global longitudinal strain; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LV = left ventricular; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; NT = N-terminal; KCCQ=Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; mmHg = per millimeters of mercury; μl=microliter; kg/m2= kilogram per squared meter; g/dl=grams per deciliter; ml/min=milliliters per minute; mmol/L= millimoles per liter; mEq/=milli equivalents per liter; mg/dl=milligrams per deciliter.

There was a higher representation of blacks among patients with anemia (Table 1). There were more patients with orthopnea, peripheral edema, and NYHA functional class III/IV amongst patients with anemia. Patients with anemia had a higher prevalence of co-morbidities like diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and renal insufficiency. These patients had a higher prevalence of recent hospitalization and the concentration of markers of myocardial stretch (BNP and NT-proBNP). There was no difference in the LVEF or global longitudinal strain. The proportion of patients on spironolactone was similar in the 2 groups (Table 1).

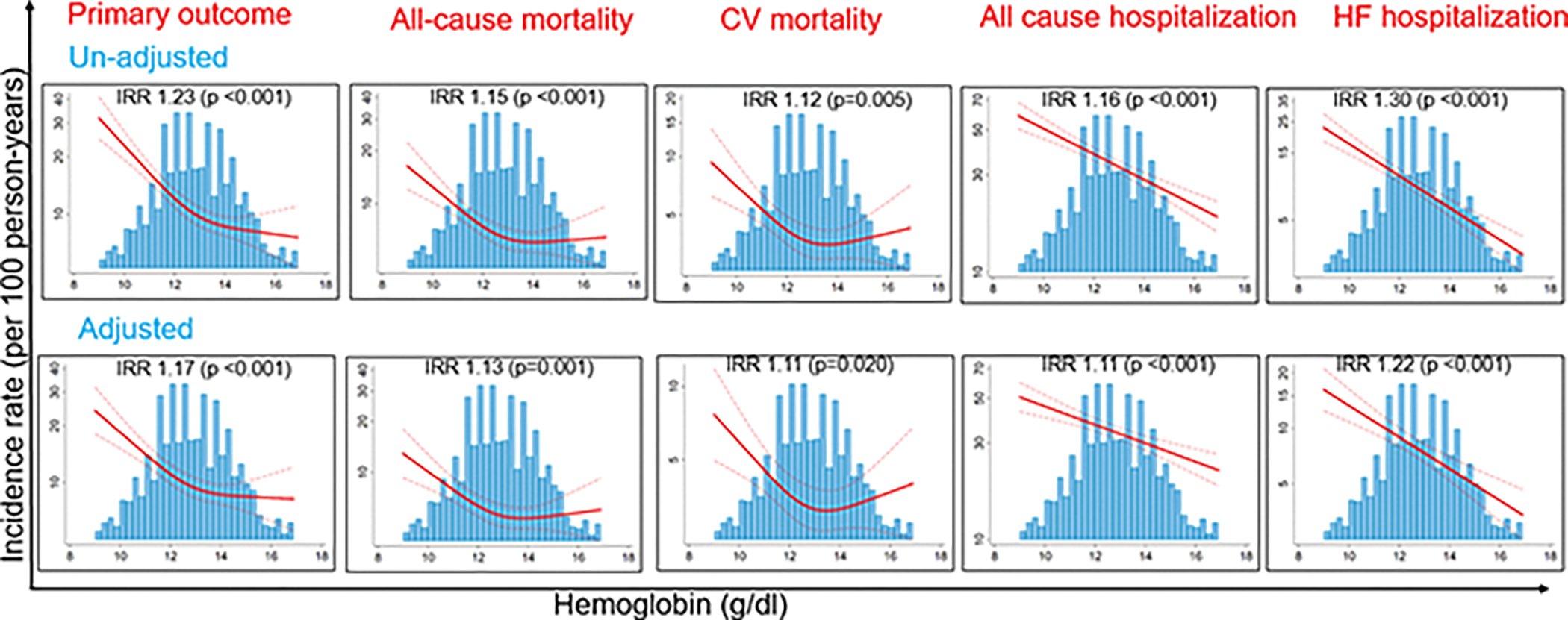

In the TOPCAT-Americas, there were 517 patients with the primary outcome, with an annual rate of 11.4% (95% CI 10.5, 12.4) over 2.4 years of follow-up (IQR 1.4–3.9). Patients with anemia had a 52% higher risk of the primary outcome as compared to those without anemia (IR 16.4 vs. 8.4 events per 100 person-years, Adjusted HR [AHR]: 1.52, p<0.001) (Table 2). With every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, there was a 17.0% (p<0.001) increase in the adjusted incidence rate of the primary outcome (Figure 2). There was no interaction between hemoglobin and gender (p=0.915) or hemoglobin and the use of spironolactone (p=0.632) on the risk of the primary outcome.

Table 2:

Outcomes in the TOPCAT-Americas Population Stratified by Anemia

| Hazard Ratio* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | n/N | Median Follow-up Time (in years) | Unadjusted | P-value | Adjusted (n=1728) | P-value |

|

| ||||||

| Primary Outcome † | 517/1748 | 2.4 | 1.90 (1.60, 2.26) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.27 to 1.83) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | ||||||

| All-cause | 385/1748 | 2.9 | 1.62 (1.32 to 1.97) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.74) | 0.002 |

| CV mortality | 221/1748 | 2.9 | 1.65 (1.27 to 2.16) | 0.001 | 1.47 (1.11 to 1.94) | 0.007 |

| Non-CV mortality | 164/1748 | 2.9 | 1.56 (1.15 to 2.12) | 0.004 | 1.31 (0.95 to 1.82) | 0.104 |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| All cause hospitalization | 1051/1748 | 1.5 | 1.46 (1.29 to 1.65) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.44) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 396/1748 | 2.4 | 2.03 (1.67 to 2.49) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.26 to 1.93) | <0.001 |

| Other events | ||||||

| Aborted cardiac arrest | 6/1748 | 2.9 | 1.69 (0.34 to 8.48) | 0.521 | 0.81 (0.11 to 5.78) | 0.832 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 94/1748 | 2.6 | 1.52 (1.02 to 2.29) | 0.041 | 1.43 (0.93 to 2.21) | 0.103 |

| Stroke | 77/1748 | 2.8 | 1.15 (0.73 to 1.81) | 0.535 | 1.06 (0.66 to 1.71) | 0.797 |

with no anemia as the reference standard.

Primary Outcome defined as a composite of CV mortality, aborted cardiac arrest and HF hospitalization.

HF = Heart Failure; CV = Cardiovascular. Covariates in adjusted cox-proportional hazard include age, sex, race, ethnicity, current smoker, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, left ventricle ejection fraction, estimated glomerular filtration rate, atrial fibrillation, New York Heart Association class (III and IV vs. I and II), orthopnea, myocardial infarction and stroke at baseline, peripheral arterial disease, and treatment with spironolactone.

Figure 2:

Relationship between hemoglobin and the Primary Outcome, All-cause mortality, Cardiovascular-Mortality, All-cause hospitalization and Heart Failure Hospitalization in the TOPCAT-Americas Population.

The adjusted Poisson regression models were controlled for age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, estimated GFR (eGFR based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation), atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, New York Heart Association class (III and IV vs. I and II), orthopnea, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, treatment with spironolactone, current smoker, left ventricle ejection fraction, and albumin concentration. Restricted cubic spline Poisson regression models estimates (solid red) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (dashed red). Blue bars represent the frequency histogram. IRR: Incidence rate ratio for every 1 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin; dL: deciliter

There were 385 deaths during a median follow-up of 2.9 years (IQR 1.9–4.2). The majority of deaths were CV-related (221/385; 57%). Patients with anemia had a 40% higher risk of all-cause mortality (IR 9.5 vs. 6.0 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.40, p=0.002) and a 47% higher hazard of CV mortality (IR 5.5 vs. 3.4 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.47, p=0.007) as compared to those without anemia (Table 2). There was no interaction between hemoglobin and gender for all-cause mortality (p=0.444) or CV mortality (p=0.207). The risk of non-CV mortality was also higher in anemics but not statistical significance (IR 4.0 vs. 2.6 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.31, p=0.104) (Table 2).

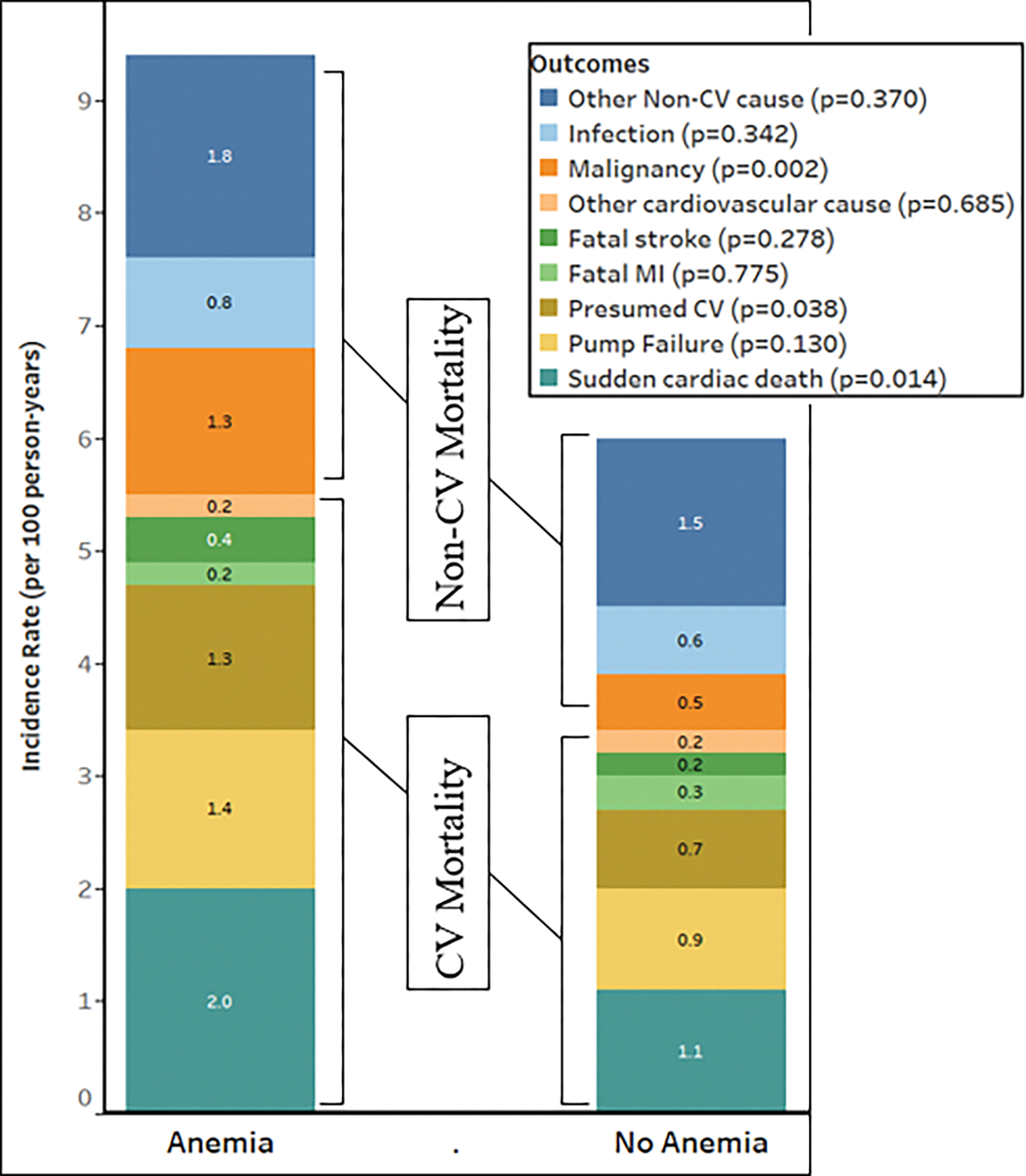

SCD/ACA accounted for 35% (77/221) of CV mortality. Among CV mortality, patients with anemia had a higher risk of SCD/ACA (IR 2.0 vs. 1.1 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.67, p=0.026), and mortality due to presumed CV causes (IR 1.3 vs. 0.7 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.83, p=0.035) (Figure 3 and Supplement Table 1). There was no difference in the risk of death due to pump failure (IR 1.4 vs. 0.9 events per 100 person-years, p=0.109).

Figure 3:

Relationship between anemia and cause-specific mortality in the TOPCAT-Americas Population. CV: Cardiovascular, MI: Myocardial infarction

Among non-CV causes of mortality, 26% (42/164) were due to malignancy. Patients with anemia had a higher hazard of mortality due to malignancy (IR 1.3 vs. 0.5 events per 100 person-years, AHR 2.61, p=0.003) (Figure 3 and Supplement Table 1).

With every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, the adjusted IR of all-cause mortality, CV mortality and non-CV mortality increased by 13, 11 and 14 events per 100 person-years, respectively (Figure 2).

Overall, there were 1,044 hospitalizations during a median duration of 1.5 years (IQR 0.5–2.6) of follow-up. Of them, 396 (38%) were for HF. Patients with anemia had a higher risk for all-cause and HF-related hospitalization (IR 43.1 vs. 28.3 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.26, for all-cause hospitalization and IR 13.0 vs. 6.2 events per 100 person-years, AHR 1.56 for hospitalization related to HF, p<0.001 for both) (Table 2). With every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, the adjusted IR of any hospitalization and hospitalization for HF increased by 11 and 22 events per 100 person-years, respectively (p<0.001 for both) (Figure 2).

There were 102 hospitalizations within 30 days. Patients with anemia had a higher incidence of 30-day all-cause hospitalization (IR 8.0 vs. 4.4 events per 100 person-years, Adjusted Incidence Rate-Ratio [IRR] 1.60, 95% CI 1.06, 2.42, p=0.027). They also had a higher incidence of 30-day hospitalization for HF (IR 3.4 vs. 0.8 events per 100 person-years, Adjusted IRR 3.40, 95% CI 1.50, 7.81, p=0.004). With every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, the incidence rate of 30 day all-cause hospitalization and hospitalization for HF increased by 22 events per 100 person-years (Adjusted IRR 1.22, 95% CI 1.08, 1.39, p=0.002) and 50 events per 100 person-years (Adjusted IRR 1.50, 95% CI 1.19, 1.88, p=0.001), respectively.

There was no significant difference in the hazard of ACA, myocardial infarction, or stroke in patients with or without anemia (Table 2).

With every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, there was a significant increase in BNP and NT-proBNP (p <0.05 for both) (Supplement Table 2). There was an association of impaired diastolic dysfunction (increased lateral and septal E/e’), but not systolic function (LVEF) with a decrease in hemoglobin. (Supplement Table 2).

Discussion

In this post-hoc analysis of the TOPCAT-Americas population, we observed that the risk of the primary outcome, all-cause, CV and non-CV mortality, as well as all-cause and hospitalizations for HF, increased significantly with a decrease in hemoglobin after extensive adjustment. Patients with anemia also had a higher risk of SCD/ACA and death due to malignancy.

The prevalence of anemia in HFpEF varies from 12% to 33%.2,5,7 The higher prevalence (41%) of anemia in the TOPCAT-Americas could be due to the higher age, and the higher representation of women and blacks- All are independent risk factors for anemia.9 Low hemoglobin in HFpEF could be due to either hemodilution or an absolute reduction in the red blood cell volume.15 The higher prevalence of recent HF-related hospitalization and signs related to congestion in patients with anemia suggests a state of volume overload. Data to measure red blood cell volume and assess hemodilution was not collected in the TOPCAT trial.

Other important causes of low hemoglobin in patients with HF include iron deficiency, chronic inflammation, and impaired renal function.16 Renal insufficiency is a strong predictor of low hemoglobin.9,17 A study by O’Meara et al.9 suggested that in HFpEF, hemoglobin drops little until eGFR declines to <60 ml/min/1.73m2. In the TOPCAT-Americas, 48.6% patients had eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2. We found that with every 10 ml/min/1.73m2 decline in eGFR below 60 ml/min/1.73m2, hemoglobin drops by 0.32 g/dl, which is similar to that reported by O’Meara et al.9 (0.25 g/dl).

The adverse prognostic role of anemia in HFpEF can be explained by several mechanisms. In heart failure, there is altered myocardial energy efficiency.18,19 This efficiency could be further reduced by a low oxygen delivery to the myocytes because of low hemoglobin. In anemia, cardiac mass increases by as much as 25% with an increase in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.20 Further, human studies to suggest an improvement in left ventricle geometry with an improvement in hemoglobin.21–23 In our study, we found that patients with anemia have higher ventricular remodeling (higher volumes and impaired diastolic function). This adverse remodeling may be contributing to increased CV mortality and HF hospitalization. There was no difference in global longitudinal strain between the HFpEF patients with anemia or no anemia. We found that there was a significant impairment in global longitudinal strain only in patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dl which is similar to a previous report.24 This suggests that cardiac contractility remains preserved until prolonged and severe anemia leads to remodeling and decompensation.25

The adverse prognostic role of anemia in HFpEF is also suggested by previous reports.7–9 In a post-hoc analysis of the CHARM-Preserved trial in the HFpEF population, O’Meara et al9 suggest that patients with anemia had a higher risk of mortality and hospitalizations. We validate O’Meara et al.’s9 findings in another rigorously studied HFpEF population. In our study, with every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 13%. This parallels data from the HFrEF population, where every 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin increased the risk of mortality by 16%.21 Further, our data add to the literature that suggests an adverse prognosis with anemia in CV diseases like acute coronary syndrome,26 and valvular heart disease.27

Our study has important public health implications. We found that the incidence of hospitalization increases from 38% to 78% as hemoglobin drops from 12 g/dl to 7 g/dl. Thus, hemoglobin improvement may help reduce hospitalizations in HFpEF, given the lack of benefit with current treatment strategies for HFpEF.2–6 Till now, there has been only 1 randomized control trial exploring the benefits of improving hemoglobin in patients with HFpEF.10 The results of this single-center trial with an erythropoietin analog in 56 community-dwelling HFpEF patients did not suggest any improvement in the left ventricular geometry, or quality of life despite significantly improving hemoglobin after 24 weeks.10 The strong association of low hemoglobin with worse outcomes in HFpEF and lack of clinical benefit even with hemoglobin improvement in this small trial merits a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology. Anemia in HFpEF, as in the general population, is a heterogeneous condition with distinct and sometimes overlapping causes. As with distinct phenotypes of HFpEF28, there may be distinct phenotypes of anemia in HFpEF, such as erythropoietin-deficient, inflammation-related, and volume overload-related. Anemia management also requires a phenotype-matched approach. For instance, in volume overload-associated anemia, treatment with erythropoietin-analogs may be less beneficial. Among the currently described HFpEF phenotypes, anemia correction may have the maximum benefit in high-output phenotype.28 Further, the benefits may be more in those with more profound anemia as the only trial conducted until now excluded patients with hemoglobin <9 g/dl.10 Ongoing trials such as the FAIR-HFpEF trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03074591) will help understand if intravenous replacement of iron helps improve prognosis in HFpEF.

Our study has important limitations. We could analyze hemoglobin values only at the time of patient enrollment as hemoglobin was not available at follow-up. Evaluating change in hemoglobin in patients who have adverse outcomes would give us better insight into how low hemoglobin contributes to adverse outcomes in HFpEF. Though we adjusted for most known confounders in the model, markers of inflammation (CRP or hs-CRP) were not available to understand their possible role in elevated risk in anemic HFpEF patients. The data regarding baseline malignancy were not available in TOPCAT data. Hence it is difficult to determine whether deaths were due to prevalent malignancy. The patients with an expected life expectancy of <3 years were excluded. Therefore, it is likely that these deaths were related to incident malignancy.

In conclusion, anemia was a strong predictor of the composite primary outcome of CV mortality, aborted cardiac arrest and HF hospitalization in the TOPCAT-Americas. This association was primarily driven by an increased hazard of CV mortality and HF hospitalization. Anemia was also associated with an increased incidence of SCD/ACA and death due to malignancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This manuscript was prepared using TOPCAT Research Materials obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Funding:

Dr. Bajaj is supported by Walter B. Frommeyer, Jr. Fellowship in Investigative Medicine awarded by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, American College of Cardiology Presidential Career Development Award and National Center for Advancing Translational Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR001417. Dr. Prabhu is supported by NIH R01 grants HL125735 and HL147549, and a VA Merit Award I01 BX002706.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors had any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Investigators C, Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9386):777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JG, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J, Investigators P-C. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(19):2338–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, Love TE, Aronow WS, Adams KF Jr., Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114(5):397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, Ptaszynska A, Investigators IP. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2456–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O’Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Ramasubbu K, Zachariah AA, Wehrens XH, Deswal A. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):998–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in a Population-Based Study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(3):260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Lang CC, Roger SD, Young JB, Solomon SD, Granger CB, Ostergren J, Olofsson B, Michelson EL, Pocock S, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA. Clinical correlates and consequences of anemia in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: results of the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Program. Circulation. 2006;113(7):986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurer MS, Teruya S, Chakraborty B, Helmke S, Mancini D. Treating anemia in older adults with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction with epoetin alfa: single-blind randomized clinical trial of safety and efficacy. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(2):254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai AS, Lewis EF, Li R, Solomon SD, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Clausell N, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, McKinlay S, O’Meara E, Shaburishvili T, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA. Rationale and design of the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial: a randomized, controlled study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. American heart journal. 2011;162(6):966–972.e910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Heitner JF, Lewis EF, O’Meara E, Rouleau JL, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, McKinlay SM, Pitt B. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation. 2015;131(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Denus S, O’Meara E, Desai AS, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Leclair G, Jutras M, Lavoie J, Solomon SD, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Rouleau JL. Spironolactone Metabolites in TOPCAT - New Insights into Regional Variation. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;376(17):1690–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organisation WH. Nutritional anaemias: report of a WHO scientific group. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1968;405:3–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noumi B, Teruya S, Salomon S, Helmke S, Maurer MS. Blood volume measurements in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: implications for diagnosing anemia. Congest Heart Fail. 2011;17(1):14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleijn L, Belonje AM, Voors AA, De Boer RA, Jaarsma T, Ghosh S, Kim J, Hillege HL, Van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P. Inflammation and anaemia in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Heart. 2012;98(16):1237–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Meara E, Rouleau JL, White M, Roy K, Blondeau L, Ducharme A, Neagoe PE, Sirois MG, Lavoie J, Racine N, Liszkowski M, Madore F, Tardif JC, de Denus S. Heart failure with anemia: novel findings on the roles of renal disease, interleukins, and specific left ventricular remodeling processes. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(5):773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz AM. Cardiomyopathy of Overload. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322(2):100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sack MN, Rader TA, Park S, Bastin J, McCune SA, Kelly DP. Fatty acid oxidation enzyme gene expression is downregulated in the failing heart. Circulation. 1996;94(11):2837–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakusan K, Cicutti N, Kolar F. Effect of anemia on cardiac function, microvascular structure, and capillary hematocrit in rat hearts. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;280(3):H1407–H1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand I, McMurray JJ, Whitmore J, Warren M, Pham A, McCamish MA, Burton PB. Anemia and its relationship to clinical outcome in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110(2):149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akaishi M, Hiroe M, Hada Y, Suzuki M, Tsubakihara Y, Akizawa T. Effect of anemia correction on left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with modestly high hemoglobin level and chronic kidney disease. J Cardiol. 2013;62(4):249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckardt KU, Scherhag A, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, Clyne N, Locatelli F, Zaug MF, Burger HU, Drueke TB. Left ventricular geometry predicts cardiovascular outcomes associated with anemia correction in CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20(12):2651–2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Q, Shen J, Liu Y, Luo R, Tan B, Li G. Assessment of left ventricular systolic function in patients with iron deficiency anemia by three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography. Anatol J Cardiol. 2017;18(3):194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metivier F, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, Pannier B, London GM. Pathophysiology of anaemia: focus on the heart and blood vessels. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2000;15 Suppl 3:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, Burton PB, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Gibson CM, Braunwald E. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2042–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rheude T, Pellegrini C, Michel J, Trenkwalder T, Mayr NP, Kessler T, Kasel AM, Schunkert H, Kastrati A, Hengstenberg C, Husser O. Prognostic impact of anemia and iron-deficiency anemia in a contemporary cohort of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;244:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah SJ, Katz DH, Deo RC. Phenotypic spectrum of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10(3):407–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.