Abstract

High levels of loneliness are prominent in teenagers ranging from ages 14–19. The 4‐week Self‐Care program, offered by the Heartfulness Institute, is designed to develop social–emotional skills and self‐observation. This study examined the impact of the Self‐Care program on loneliness in high school students in the United States in a randomized, wait‐list control trial with baseline and postintervention assessments. High school participants, aged 14–19, were randomized into a control‐wait‐listed group (n = 54) and a Heartfulness group (n = 54). Both the groups completed the intervention and the presurveys and postsurveys online, assessing their loneliness with the UCLA Loneliness Scale. The initial analysis noted the baseline equivalence of the data. A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant time * group interaction, with a significant decrease in loneliness reported in the Heartfulness Intervention group but no significant pre–post difference in the control group. In summary, the short online intervention program consisting of self‐care tools decreased loneliness scores in the participants. This study opens up a new valley of possibilities, apart from existing research, and demonstrates that the online intervention used might be helpful to decrease loneliness levels in teens.

Keywords: Heartfulness, high school students, loneliness, mental health, social–emotional skills

INTRODUCTION

Loneliness is defined as a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one's social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one's social relationships (Hawkley et al., 2008; Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001; Wheeler et al., 1983). It refers to a perceived discrepancy between social needs and their availability in the environment (Mushtaq et al., 2014). Studies show chronic loneliness has clear links to an array of health problems, including dementia, depression, anxiety, self‐harm, heart conditions, and substance abuse (Ducharme, 2020). Current high schoolers belong to the category of Generation Z—also referred to as iGen, Homelanders, Digital Natives, and most commonly as Gen Z or Gen Zers—comprising individuals born between 1995 and 2012 and accounting for approximately 24% of the US population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Gen Z has experienced several disruptions in a short time with changes in the political, social, technological, and economic landscape (Pichler et al., 2021). A survey conducted by Cigna (2018) to understand the impact of loneliness in the United States showed that Gen Z is the loneliest generation with the highest loneliness score measured on the UCLA Loneliness Scale and claims to be in worse health than older generations.

Even before the COVID‐19 pandemic, public‐health experts were concerned about an epidemic of loneliness in the United States. The coronavirus has exacerbated that problem, as stay‐at‐home mandates have indefinitely limited socializing opportunities for people to members of their households. While these restrictions have been challenging for people of all ages, they may be particularly difficult for adolescents, who at this developmental stage rely heavily on their peer connections for emotional support and social development (Ellis & Zarbatany, 2017). A study conducted by Magson et al. (2021) provides initial longitudinal evidence for the decline of adolescents' mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Over the last decade, new technologies such as social media and the invention of the smartphone have made our everyday interactions and tasks more dependent on virtual platforms. While these recent advancements provide new avenues of connection for youths worldwide, they can also aggravate mental health issues. Some of these mental health issues may include—but are not limited—to stress, depression, and anxiety. Studies have shown that apps and interventions can benefit high schoolers in stress management and combating depressions (Harrer et al., 2019; Iyer et al., 2021).

Loneliness in youth is thus becoming common and causing poor physical and mental health. In addition, lonely people have lower feelings of self‐worth (Peplau et al., 1982), tend to blame themselves for social failures (Anderson et al., 1983), are more self‐consciousness in social situations (Cheek & Buss, 1981), and adopt behaviors that increase, rather than decrease, their likelihood of rejection (Horowitz, 1983). Loneliness not only increases depressive symptoms but also increases perceived stress, fear of negative evaluation, anxiety, and anger and diminishes optimism and self‐esteem (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Hawkley and Capitanio (2015) point to evidence linking perceived social isolation with adverse health consequences, including depression, poor sleep quality, impaired executive function, accelerated cognitive decline, poor cardiovascular function, and impaired immunity at every stage of life. The research studies on loneliness have focused on youth and older adults, presenting a gap in research targeting the high school age group. It is essential to address the effects of loneliness in high schoolers because online learning in the age of COVID‐19 has exacerbated this concern with students' exposure to the computer screen for hours.

Heartfulness approach to the theoretical framework of loneliness

A remote intervention on Heartfulness meditation in physicians and advanced practice providers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in a 4‐week study showed significant decrease in loneliness (Thimmapuram et al., 2021). The Heartfulness program is a simple heart‐based program offered by Heartfulness Institute to create a loving, compassionate learning environment to nurture individual well‐being and build social–emotional skills for balanced living. The school program is designed for the whole school community to enable its members to create a more relaxed, compassionate, and positive environment using Heartfulness tools and techniques to feel connected and collaborate with their peers to uncover their highest potential. The Heartfulness approach also encourages the building of stress management and social–emotional skills charted by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL): self‐awareness, self‐management, social‐awareness, relationship skills, and decision‐making skills (CASEL, 2020). Previous research has shown a correlation between stress, anxiety, and emotional well‐being with Heartfulness (Iyer et al., 2021; Iyer & Iyer, 2019).

Weiss (1973) identified six social needs that, if unmet, contribute to feelings of loneliness. Those needs are attachment, social integration, nurturance, reassurance of worth, a sense of reliable alliance, and guidance in stressful situations. Increasing feelings of loneliness also increased feelings of shyness, anxiety and anger, and decreased feelings of social skills, optimism, self‐esteem, and social support, suggesting that loneliness is syndrome‐like in carrying with it a range of attributions, expectations, and perceptions that reinforce feelings of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006).

The Heartfulness Self‐Care program, offered by the Heartfulness Program for Schools, is a 4‐week program that promotes stress management and social–emotional learning tools (Heartful Schools, 2021). In 2020, a team of high schoolers helped create the self‐care program to engage with their peers and build a community that focuses on self‐care. As the pandemic increased the perceptions of loneliness in this age group, this study focused on the impact of this program on loneliness of high school students. Participants of the program received an E‐portfolio that included various activities for self‐care and guided practices through Heartfulness. They also participated in four webinars that focused on managing stress, building a positive mind map, aligning with the daily circadian rhythm to improve sleep quality, and setting goals with self‐observation. The program details are available in a figure in the Supporting Information.

Purpose

The study investigated and examined the relationship between the Heartfulness Self‐Care program to measurable changes in the perception of loneliness in high school students in the United States. The hypothesis is that high schoolers in the United States who participate in the Self‐Care program would have lower levels of loneliness after completion of the program than those who do not participate in the program.

METHODS

Design

This quantitative study was a randomized, wait‐list control group with an assessment conducted at baseline and postintervention after 4 weeks. Over 100 participants showed interest by advertising on social media via Facebook on the Heartfulness Program for School page and the Heartful Schools webpage, posted for a month. An online team generator tool assigned participants randomly to one of two groups: the Heartfulness group or the control group (Randomlists, 2020). Before beginning the 28‐day self‐care program, each participant completed a survey. The preprogram survey used the UCLA Loneliness Scale to measure the participants' loneliness levels before completing the program. During the 28‐day program, participants completed an E‐portfolio and practiced Heartfulness techniques and tools. In addition to this, they viewed one webinar every weekend to learn about the previously mentioned topics. After the self‐care program, the participants filled out a postprogram survey to measure their levels of loneliness.

Participants

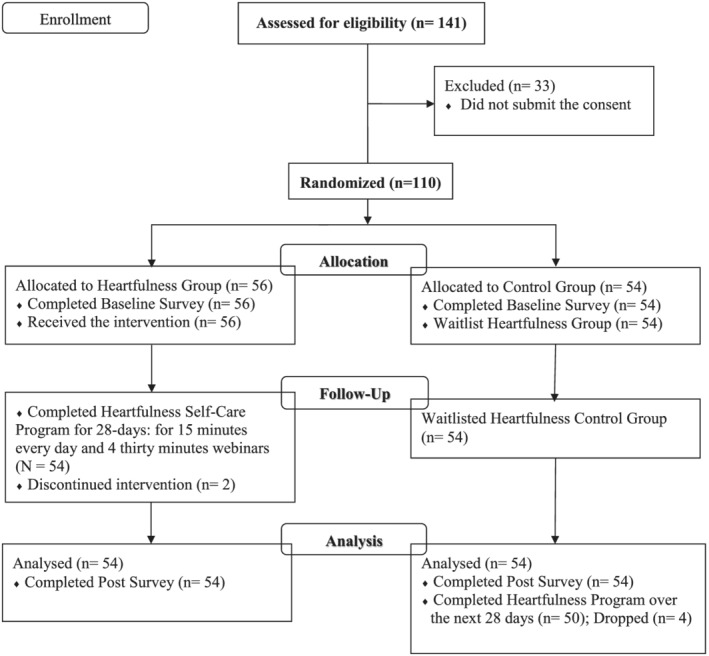

Approved by an IRB through a full board review, participants were recruited between June and July 2020 through awareness via social media (Facebook and Heartfulness webpage). Students enrolled in high school in the 2019–2020 school year in the United States were included in the study. The study's exclusion criteria included (1) non‐English speaking high school students in the United States and (2) prior mental health diagnoses such as major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders, as mentioned in the consent form. Interested participants with prior major disorders did not participate as meditation and contemplative practices may be uncomfortable and may seem challenging. The Heartfulness Loneliness Study ended up with 141 interested participants; 110 gave consent, of which 108 continued with the study. After completing the informed consent and baseline survey, an online generator tool randomly placed participants into the Heartfulness group (n = 56; two dropped and did not complete the program) and the wait‐list control group (n = 54). Participants entered a raffle of five $50 gift cards on completing the study. Figure 1 shows the study design flowchart.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flowchart of participants enrolment

Ethics and participant protection

After the IRB approved the study protocol in June 2020, all participants provided electronically signed consent before participating in the study. A parent or guardian gave consent for adolescents to participate in this study along with assent from adolescents. Participants voluntarily provided consent and assent to participate in the study. Consent and assent forms used during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Intervention

Heartfulness Intervention group

After randomization, the Heartfulness group received an E‐portfolio and a calendar. The total time commitment in the 4‐week program was 15 min every day, with four 30‐min webinars once a week. The daily activity also included guided tools to relax, meditate, affirm, breathe, rejuvenate, and self‐observe. Each webinar was delivered online using Zoom by certified high school trainers and guided the participants into the upcoming week to relieve stress, anxiety, and overall mental well‐being. As these webinars were not interactive, questions were directed to the study's principal investigator and answered after the session was over. In addition, the attendance for the webinars was marked and tracked on the Zoom; however, the daily activities were self‐monitored.

The first webinar, Stress to Destress, detailed important and relevant information about stress and helped the participants become aware of their stressors and find ways to destress. This webinar ended with a guided relaxation and meditation exercise. The second webinar, Fostering Positivity, was conducted a week later with statistics on positivity, followed by a mind mapping activity, a brief dialog on the importance of a positive mindset, and a guided positive affirmation exercise. In the third week, the Circadian Rhythm Webinar consisted of a brief introduction on Circadian Rhythm, a circadian rhythm activity including the participant's daily life cycle, guided relaxation and meditation exercise, and finally, a guided PEMS exercise to self‐observe physically, emotionally, and mentally to connect the whole self. During the final webinar, Goal Setting, participants explored the importance of goal setting and how to communicate with confidence and compassion through heartful communication via connecting with their hearts. Participants completed their goals pyramid and experienced guided PEMS to self‐observe.

Wait‐list control group

Participants randomized to the wait‐list control group received an email with their group assignment stating that they would receive access to the Self‐Care program after 4 weeks. They followed their daily routine during this time. After 4 weeks, participants received a link to the postassessment survey and sent an email with the E‐portfolio to begin their Self‐Care program.

Measure

The 20‐item UCLA Loneliness Scale, Version 3, is designed to measure subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation. The psychometric data support the validity of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3) in assessing loneliness in various populations, ranging from college students to the elderly (Russell, 1996). This measure is reliable in college students; Cronbach's alpha in this study was .93. The response items scale ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Loneliness sum scores hence ranged from 20 (low) to 80 (high). Both the Heartfulness and wait‐list control groups were administered the UCLA Loneliness Survey at baseline (Week 0) and postintervention (after the program completion, Week 4) to assess loneliness scores via an online survey (Google Form). Data collected included demographic data such as age, sex, class, and school.

Data analysis

Data cleaning eliminated the two dropouts, data errors, duplicates, or corruption in the data. Questions 1, 5, 6, 9, 10, 15, 16, 19, and 20 of the UCLA survey were reverse scored, before building a sum score. The differences between the pre‐Heartfulness and post‐Heartfulness and control group scores using a paired samples t‐test on data from the UCLA Loneliness measure were analyzed for statistical significance p < .001. Cohen's delta (d) assessed each pair‐wise comparison's effect size and practical relevance. Effect sizes is small if d ≤ .2, medium if d = .5, and large if d ≥ .81 (Cohen, 1998). The analysis used both paired t‐tests and a repeated measures ANOVA to compare the two groups using R version 4.0.3 and RStudio Version 1.3.1093 (RCore Team, 2020; RStudio Team, 2020). The overall intervention effect on loneliness was assessed using an analysis of variance for repeated measures with statistical covariates of age and gender. The analyzed data are archived in the FigShare repository and openly available (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13393325.v1).

RESULTS

Participant demographics

Baseline characteristics of participants' ages ranged from 14 to 19 years. In addition, demographic data divided the US states into regions and their grade levels during the 2019–2020 school year (United States Region, 2020) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 108)

| Characteristics | Heartfulness | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 14 | 4 | 7.4 | 11 | 20.4 |

| 15 | 16 | 29.6 | 12 | 22.2 |

| 16 | 15 | 27.8 | 8 | 14.8 |

| 17 | 10 | 18.5 | 12 | 22.2 |

| 18 and over | 9 | 16.7 | 11 | 20.4 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 8 | 14.8 | 12 | 22.2 |

| Female | 46 | 85.2 | 42 | 77.8 |

| Class 2019–20 | ||||

| Freshman | 13 | 24.1 | 17 | 31.5 |

| Sophomore | 14 | 25.9 | 10 | 18.5 |

| Junior | 16 | 29.6 | 13 | 24.1 |

| Senior | 11 | 20.4 | 14 | 25.9 |

| Region | ||||

| West | 11 | 20.4 | 9 | 16.7 |

| Southwest | 12 | 22.2 | 11 | 20.4 |

| Midwest | 12 | 22.2 | 18 | 33.2 |

| Southeast | 3 | 5.6 | 3 | 5.6 |

| Northeast | 16 | 29.6 | 13 | 24.1 |

Intervention effects on loneliness

Descriptive statistics observed the distribution of the data of 108 participants. The summary showed that the loneliness score at baseline was 46.54, and the post was 38.07 in the Heartfulness group. In contrast, at baseline, the loneliness score was 43.93, and the post was 42.89 in the control group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics (n = 108)

| n | Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐Heartfulness | 54 | 23 | 74 | 46.54 | 10.31 |

| Post‐Heartfulness | 54 | 20 | 58 | 38.07 | 8.44 |

| Precontrol | 54 | 21 | 70 | 43.93 | 10.97 |

| Postcontrol | 54 | 23 | 71 | 42.89 | 11.49 |

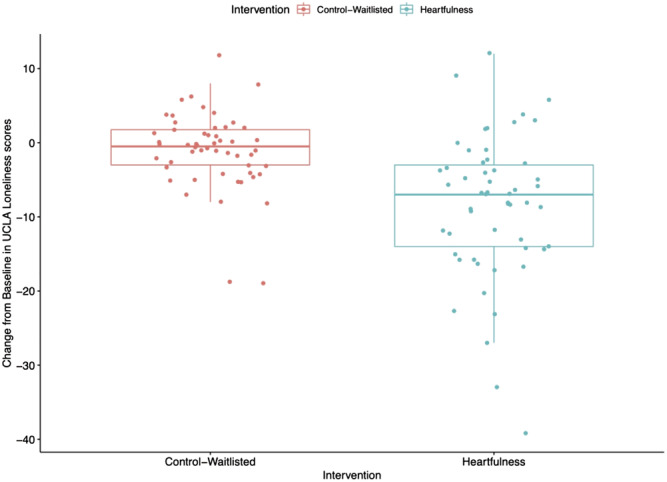

The baseline mean scores of self‐reported loneliness in the Heartfulness group (M = 46.54, SD = 10.31, n = 54) and control group (M = 43.92, SD = 10.97, n = 54) showed no significant differences between the groups (t(53) = −1.365, p = .089). Heartfulness participants scored significantly lower on loneliness after completing the 28‐day program, from 46.54 to 38.07 (t(53) = −6.434, p < .001), and Cohen's d = .90. There was no significant difference for control participants between loneliness scores, from 43.93 to 42.89 (t(53) = −0.054, p = .08), and Cohen's d = .09. Cohen's delta (d) indicated larger effect sizes in UCLA paired analysis in the Heartfulness group and small effect sizes in the control group. The mean difference in the prescores and postscores in the Heartfulness group (M = 8.46, SD = 9.67, n = 54) was significantly greater than zero, t(53) = 6.53, two‐tailed p < .001, and the repeated measures ANOVA controlling for age and gender showed a significant time * group interaction term, F(1) = 24.01, p < .001, η p 2 = .19; providing evidence that the intervention is effective in reducing perceptions of loneliness. The post hoc analysis for the current sample of 108 participants shows the power of the study to be 99.9%, with an alpha error of 0.5%, indicating that the sample was enough for large effect size. A 95% CI about the mean difference in the pre and post loneliness scores is (5.82, 11.10). The difference in loneliness scores from baseline to post scores could be as low as an average of 5.82 to a high of 11.10 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Change from baseline in UCLA Loneliness scores by intervention [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To address the normality of the distribution of the data, the nonparametric test, a permutation test conducted, observed a significant difference between the two groups' postscores. Furthermore, as another sensitivity analysis to consider the outliers, the LOWESS (locally weighted smoothing) showed a nonlinear regression indicating that post‐Heartfulness UCLA scores were significantly different from the control group (see the figure in the Supporting Information to this article).

UCLA post‐Heartfulness scores by class and region

Individuals in the Heartfulness group scored significantly lower on loneliness post‐Heartfulness than baseline premean scores in all classes. The change in score was significantly lower for Freshman (43.92 to 35.38), Sophomore (48.86 to 40.07), Junior (46.25 to 38.81), and Senior (47.09 to 37.64) with p < .001 in all class categories.

Heartfulness group participants scored significantly lower on the loneliness post‐Heartfulness than baseline premean scores in all regions based on their high school locations, including West (48.64 to 38), Southwest (47 to 39.25), Midwest (44.69 to 35.69), Southeast (43.5 to 36), and Northeast (45.8 to 39.67) with p < .001 in all region categories. The change in UCLA scores from baseline to post in the Heartfulness Intervention has data below zero for all regions and class levels, showing that this intervention reduces loneliness scores. The control group scores showed scatter points around the zero values, showing not many changes (see the figure in the Supporting Information to this article).

The Heartfulness and Control groups further subdivided into smaller groups based on class and region showed significance in the Heartfulness group. However, the analyses on the smaller group are almost certainly underpowered. The significance of the data could be extended with a larger sample in future research.

DISCUSSION

This study indicated that the self‐care program significantly reduced loneliness in high schoolers in the United States. This intervention was self‐guided and virtual and, thus, accessible and convenient for teenage participants. The program focuses on guided tools from Heartfulness that focuses on self‐care through the guided experience of relaxation, meditation, affirmations, breathing, rejuvenation, and self‐observation interwoven in the daily activities. The participants used a 28‐day E‐portfolio to track the completion of activities based on these six tools of the Heartfulness program to develop a connection to self, experience calmness within, and build social–emotional skills. In comparison with the control group, the Heartfulness group showed a significant decrease in levels of loneliness.

Data analyzed separately for all the classes showed significantly lower post scores than the preloneliness scores, with the most significant decrease in Seniors. The data divided into US regions showed a statistically significant decrease in the loneliness scores in all areas. Participants in all regions located in the West Region of the United States experienced the most drastic change from preintervention to postintervention survey results. Possible reasons for a high preloneliness score may include a peak of COVID cases in early July in this region (The New York Times, 2020). The intervention helped lower the scores of loneliness. In summary, the feasibility study data indicate a trend in the program's impact on loneliness in high schoolers. Future loneliness research is needed to focus on grouping participants by physical location to compare the underlying causes and trends that lead to different data across various geographic regions.

Loneliness poses a significant health problem for a sizable part of the population, with increased risks in depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, health behavior, and healthcare utilization (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015). While the traditional definition of loneliness looks at an aspect of social isolation, this study focused more on the perception of loneliness (Masi et al., 2011). In a meta‐analysis of over 40 loneliness reduction interventions dating back to the 1930s, the interventions that improve social skills focused on one or more of the following: conversational skills, speaking on the telephone, giving and receiving compliments, handling periods of silence, enhancing physical attractiveness, nonverbal communication methods, and approaches to physical intimacy (Masi et al., 2011). This study opens up a different array of possibilities apart from the existing pool of loneliness studies, as this study did not include any social interaction between participants.

The pandemic has upended lives in various capacities across all ages, races, and socioeconomic statuses. Even though stay‐at‐home mandates have ended most face‐to‐face interaction between participants and peers, they lead to increased perceptions of loneliness. The findings of this study show that feelings of loneliness can be addressed and mitigated without directly fostering social interaction. Previous research studies have reported perceived increases in anxiety, depression, and loneliness due to COVID‐19 in adults and adolescents (Chen et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). This study builds on the literature surrounding COVID‐19 as related to the increase in stress and perceived loneliness and provides evidence for combating the challenges. Research has also indicated that lonely people have lower self‐worth and are more self‐conscious in social situations (Peplau et al., 1982; Cheek & Buss, 1981). Future studies can also examine the link between the impact of Heartfulness on self‐esteem and self‐consciousness.

Limitations

Although the findings in this study are promising, the study noted several limitations. First, results were self‐reported, which could have led to response bias from the participants. In addition, most participants in the Heartfulness group, 43 out of 54 (79.6%), released their completed portfolios at the end of the study. Portfolio completion suggests that the participants followed the given directions to complete the program in almost all cases. However, participants self‐monitored, so it is impossible to determine the degree to which the participants followed the calendar and the effect per participant. Also, this study did not collect data on participants' extracurricular schedules, home life, access to the internet, or other circumstances restricting how participants could engage with the outside world and their ability to complete the daily challenges. Additionally, there was no follow‐up component, making it difficult to ascertain the longevity of the significant improvement found postintervention. Lastly, there were only 108 participants in total, also limited due to the omission of participants with mental health issues, making the data hard to generalize over the whole high school population in the United States.

CONCLUSIONS

Self‐Care participants experienced a statistically significant decrease in their loneliness levels. The program can help high schoolers reduce loneliness through self‐care stress management tools, fostering positivity, aligning with circadian rhythm, and goal setting. The findings from this study provide essential information to design future studies on loneliness interventions in teens. This study's results are consistent with other Heartfulness‐based intervention studies that measured stress levels and emotional wellness, respectively, with a significant decrease and significant increase (Iyer & Iyer, 2019; Thimmapuram et al., 2017).

The preliminary effectiveness of this intervention may help understand existing issues of loneliness and its adverse impact on teenagers' lives. This pilot feasibility study may be valuable in a larger intervention study with a more extended follow‐up period. The Heartfulness group showed a statistically significant reduction in loneliness scores after 28 days. This study suggests that it may help implement evidence‐based mental health interventions online to support adolescents.

In summary, this randomized survey study demonstrated that a virtual Heartfulness Intervention effectively improves loneliness levels in high school students. Specifically, the study found the intervention to reduce loneliness by focusing on self‐care tools effectively. Further, the study showed that increased connection to self could partly explain beneficial outcomes. Future studies should continue investigating this investigation to a larger population, tailoring to serve more male populations and broader geographical representations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or any financial gains from the study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study protocol was approved by the Solutions IRB with an IRB registration number of IORG0007116 in June 2020. All participants provided electronically signed consent before participating in the study. Consent to participate in this study was obtained from a parent or guardian and assent from adolescents. Participants voluntarily provided consent and assent to participate in the study.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04602455; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04602455.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Consent and assent forms used during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Self‐Care through Heartfulness

Figure S2. Pre and Post UCLA Loneliness Scores in Heartfulness and Control Groups

Figure S3. Change from Baseline in UCLA Scores by Intervention, Region and Class

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Heartfulness Institute (Grant 0521) supported this study through the grant for the IRB fee. The authors would like to acknowledge the time of all the Heartfulness Champions. The latter planned the 28‐day Self‐Care program. The authors are thankful to Dr. Vipul Devas for helping in the statistical analysis. The authors also thank Kamlesh D. Patel and Dr. Jayaram Thimmapuram of the Heartfulness Institute for their immense help and guidance with the practice of Heartfulness relaxation techniques.

Iyer, R. B. , Vadlapudi, S. , Iyer, L. , Kumar, V. , Iyer, L. , Sriram, P. , Tandon, R. , Morel, Y. , Kunamneni, H. , Narayanan, S. , Ganti, A. , Sriram, S. , Tandon, R. , Sreenivasan, S. , Vijayan, S. , & Iyer, P. (2023). Impact of the Heartfulness program on loneliness in high schoolers: Randomized survey study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 15(1), 66–79. 10.1111/aphw.12360

Funding information Heartfulness Institute, Grant/Award Number: 0521

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the FigShare repository, Iyer, Ranjani (2020): The Impact of Heartfulness Program on Loneliness in High School Students in the U.S. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13393325.v1.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, C. A. , Horowitz, L. M. , & French, R. D. (1983). Attributional style of lonely and depressed people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 127–136. 10.1037//0022-3514.45.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T. , Hawkley, L. C. , Ernst, J. M. , Burleson, M. , Berntson, G. G. , Nouriani, B. , & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek, J. M. , & Buss, A. H. (1981). Shyness and sociability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(2), 330–339. 10.1037/0022-3514.41.2.330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. , Zheng, D. , Liu, J. , Gong, Y. , Guan, Z. , & Lou, D. (2020). Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID‐19: A cross‐sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 36–38. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigna . (2018). U.S. Loneliness Index Fact Sheet. Retrieved January 7, 2022, from https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/newsroom/loneliness-survey-2018-fact-sheet.pdf

- Cohen, J. (1998). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 10.4324/9780203771587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning . (2020). What Is the CASEL Framework? Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/#the-casel-5

- Ducharme, J. (2020). COVID‐19 is making America's loneliness epidemic even worse. Time website. https://time.com/5833681/loneliness-covid-19/

- Ellis, W. E. , Dumas, T. M. , & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID‐19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 52(3), 177–187. 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, W. E. , & Zarbatany, L. (2017). Understanding processes of peer clique influence in late childhood and early adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 227–232. 10.1111/cdep.12248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer, M. , Apolinário‐Hagen, J. , Fritsche, L. , Drüge, M. , Krings, L. , Beck, K. , Salewski, C. , Zarski, A. C. , Lehr, D. , Baumeister, H. , & Ebert, D. D. (2019). Internet‐ and app‐based stress intervention for distance‐learning students with depressive symptoms: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 361. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C. , & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. 10.1098/rstb.2014.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C. , Hughes, M. E. , Waite, L. J. , Masi, C. M. , Thisted, R. A. , & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–S384. 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heartful Schools . (2021). Heartfulness Program for Schools offered by the Heartfulness Institute. Retrieved July 2, 2020. (https://www.heartfulnessinstitute.org/education).

- Horowitz, L. M. (1983). The toll of loneliness: Manifestations, mechanisms, and means of prevention. National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, L. , Iyer, R. B. , & Kumar, V. (2021). A relaxation app (HeartBot) for stress and emotional well‐being over a 21‐day challenge: Randomized survey study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(1), e22041. 10.2196/22041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, R. B. , & Iyer, B. N. (2019). The impact of heartfulness‐based elective on middle school students. American Journal of Health Behavior, 43(4), 812–823. 10.5993/AJHB.43.4.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magson, N. R. , Freeman, J. , Rapee, R. M. , Richardson, C. E. , Oar, E. L. , & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi, C. M. , Chen, H. Y. , Hawkley, L. C. , & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta‐analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 15(3), 219–266. 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, R. , Shoib, S. , Shah, T. , & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 8(9), WE01–WE04. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, L. A. , Miceli, M. , & Morasch, B. (1982). Loneliness and self‐evaluation. In Peplau L. A. & Perlman D. (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 135–151). Wiley‐Interscience. 10.1207/153248301753225702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, L. A. , & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspective on loneliness. In Peplau L. A. & Perlman D. (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, S. , Kohli, C. , & Granitz, N. (2021). DITTO for Gen Z: A framework for leveraging the uniqueness of the new generation. Business Horizons, 64(5), 599–610. 10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M. , & Sorensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta‐analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. 10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randomlists . (2020). Random Team Generator. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.randomlists.com/team-generator

- RCore Team . (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team . (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times . (2020). California Coronavirus Map. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/california-coronavirus-cases.html

- Thimmapuram, J. , Pargament, R. , Bell, T. , Schurk, H. , & Madhusudhan, D. K. (2021). Heartfulness meditation improves loneliness and sleep in physicians and advance practice providers during COVID‐19 pandemic. Hospital Practice, 49(3), 194–202. 10.1080/21548331.2021.1896858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmapuram, J. , Pargament, R. , Sibliss, K. , Grim, R. , Risques, R. , & Toorens, E. (2017). Effect of heartfulness meditation on burnout, emotional wellness, and telomere length in health care professionals. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 7(1), 21–27. 10.1080/20009666.2016.1270806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . (2019). Estimates of the Total Resident Population and Resident Population Age 18 Years and Older for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico. Retrieved January 7, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-state-detail.html#par_textimage_673542126

- United States Regions . (2020). National Geographic Society. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/maps/united-states-regions/

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, L. , Reis, H. , & Nezlek, J. (1983). Loneliness, social interaction, and sex roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 943–953. 10.1037//0022-3514.45.4.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Self‐Care through Heartfulness

Figure S2. Pre and Post UCLA Loneliness Scores in Heartfulness and Control Groups

Figure S3. Change from Baseline in UCLA Scores by Intervention, Region and Class

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the FigShare repository, Iyer, Ranjani (2020): The Impact of Heartfulness Program on Loneliness in High School Students in the U.S. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13393325.v1.