Abstract

Background:

Given the personal and public consequences of untreated/undertreated OUD among persons involved in the justice system, an increasing number of jails and prisons are incorporating medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) into their system. Estimating the costs of implementing and sustaining a particular MOUD program is vital to detention facilities, which typically face modest, fixed health care budgets. We developed a customizable budget impact tool to estimate the implementation and sustainment costs of numerous MOUD delivery models for detention facilities.

Methods:

The aim is to describe the tool and present an application of a hypothetical MOUD model. The tool is populated with resources required to implement and sustain various MOUD models in detention facilities. We identified resources via micro-costing techniques alongside randomized clinical trials. The resource-costing method is used to assign values to resources. Resources/costs are categorized as (a) fixed, (b) time-dependent, and (c) variable. Implementation costs include (a), (b), and (c) over a specified timeframe. Sustainment costs include (b) and (c). The MOUD model example entails offering all three FDA-approved medications, with methadone and buprenorphine provided by vendors, and naltrexone by the jail/prison facility.

Results:

Fixed resources/costs are incurred only once, including accreditation fees and trainings. Time-dependent resources/costs are recurring, but fixed over a given time-period; e.g., medication delivery and staff meetings. Variable resources/costs are those that are a direct function of the number of persons treated, such as the medication provided to each patient. Using nationally representative prices, we estimated fixed/sustainment costs to be $2,919/patient, over 1 year. This article estimates annual sustainment costs to be $2,885/patient.

Conclusion:

The tool will serve as a valuable asset to jail/prison leadership, policymakers, and other stakeholders interested in identifying/estimating the resources and costs associated with alternative MOUD delivery models, from the planning stages through sustainment.

Keywords: Budget impact tool, Guideline, Medication for opioid use disorder, Incarceration, Jail, Prison

1. Background

Opioid misuse has been associated with increased criminal-legal activity, (Birnbaum et al., 2011; Catalano et al., 2011; Mark et al., 2001; Murphy et al., 2014; Murphy & Polsky, 2016), which coincides with a high prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) among persons with criminal-legal involvement in the United States (National Academies of Sciences, 2019); the rate of OUD among individuals who are incarcerated is estimated to be around 15% (Baillargeon et al., 2009; Bronson, 2017; James, 2006; Peters et al., 1998) versus ~1% among the general US population, ages 12 and older (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022).

Pharmacotherapy is the recommended first-line treatment for OUD. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications for OUD (MOUD) are methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Despite ample evidence that treating OUD at the point of incarceration is beneficial to both personal and public health, more than 80% of incarcerated individuals with a history of OUD do not receive MOUD during their stay (Krawczyk et al., 2017). Benefits associated with MOUD provision during or immediately following incarceration include improved linkage to community-based treatment (Gordon et al., 2014; Kinlock et al., 2007; Magura et al., 2009), increased treatment retention (Carroll et al., 2008; Gordon et al., 2015; Kinlock et al., 2009), and reduced criminal behavior overdose risk and risk behaviors associated with HIV infection (Degenhardt et al., 2011; Kerr et al., 2007; Kinlock et al., 2009; MacArthur et al., 2012). Rhode Island was the first state to begin offering both induction and maintenance of all three FDA-approved medications; they found that after 1 year of implementation, the postincarceration deaths had decreased by 61% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020). In fiscal year 2017, Kentucky estimated that for every dollar spent on substance use treatment in correctional facilities there was a return of more than $4 in cost offsets (Deck et al., 2009; Green et al., 2018; Mattick et al., 2003; Staton M, 2018).

In the late 1980s and mid 1990s, several correctional facilities offered at least one form of MOUD (National Governors Association, January, 2021); by 2018, only 14 states in the United States (27% of jurisdictions) offered methadone or buprenorphine maintenance in any jail or prison facility, while 39 (76%) offered injectable extended-release naltrexone just prior to release (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). Since 2018, an increasing number of jails and prisons have begun to offer all three MOUD, either on their own, or in response to a legislative mandate, including at least 15 bills across 12 states, resulting in 62% of states with at least one facility offering some form of MOUD (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017; National Governors Association, 2021; National Academy for State Health Policy, 2020). However, the resources required to implement MOUD programs in jails and prisons vary widely due to the myriad possible combinations of a) existing services and b) potential delivery models. For example, with regard to (a), a facility may not currently offer any MOUD, but decide to offer extended-release naltrexone or buprenorphine upon release from incarceration, or they may already provide the latter service, and decide to offer MOUD to incarcerated people throughout their stay. Jails/prisons may decide to offer MOUD only to persons who enter the facility with an existing, verifiable prescription (i.e., maintenance), while other facilities may choose to offer both MOUD initiation and maintenance. With regard to (b), observed MOUD delivery models in jails/prisons include the medication being provided by the facility’s health care team, a vendor, or a combination of the two. In addition to treatment administration, vendors can provide licenses, staff supervision, training, and intake assessments. Examples of direct delivery by the facility include: on-site jail/prison health care providers administering naltrexone, which can be prescribed by any provider with a Drug Enforcement Agency license to prescribe medications; on-site providers obtaining Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) waivers to prescribe buprenorphine; and the facility becoming a licensed opioid treatment provider (OTP), thereby allowing jail/prison health care providers to store and dispense methadone onsite. Conversely, a facility may hire a vendor with an OTP license to provide all MOUD onsite. A combined model may entail the facility’s providers delivering a relatively-low-barrier treatment (i.e., naltrexone), while a vendor with the necessary licensure delivers methadone and buprenorphine. Still, other facilities have chosen to transport patients to an off-site treatment provider (National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 2021; National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020).

Jail/prison health care, unlike civilian health care, is constrained by fixed budgets, typically financed by state and federal funds, because providers cannot bill insurance (public or private) while a person is incarcerated. Moreover, jail/prison health care budgets can vary drastically between states; for example, in fiscal year 2015, the per-inmate cost for observed expenditures in Louisiana was $2,173 vs. $13,747 in Vermont (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017). Such financial constraints add even more weight to the identification of planning and start-up (i.e. implementation) costs, in addition to the day-to-day operation costs, when deciding on a particular delivery model (Saldana et al., 2022).

As a direct result of our work alongside clinical trials evaluating the comparative-effectiveness of various MOUD models for jails/prisons, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)–funded, Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (JCOIN) (Murphy et al., 2021) and Health and economic outcomes of treatment with extended release naltrexone among pre-release prisoners with opioid use disorder (HOPPER): protocol for an evaluation of two randomized effectiveness trials (Murphy et al., 2020), we developed a budget impact tool to assist jail/prison stakeholders, and criminal-legal researchers in estimating the costs associated with implementing and sustaining the aforementioned multitude of MOUD program options for jails and prisons. In this article, we discuss the context of MOUD provision within jails/prisons, and how the components of the tool can be used to estimate the implementation and sustainment costs of a given MOUD delivery model in either setting; we finish with an applied example of the tool to a hypothetical MOUD program.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

The study team identified the resources required to implement and sustain each MOUD program in US jails and prisons; and estimated the associated costs, via micro-costing analysis, which entails systematically capturing, cataloging, and valuing changes in resources resulting from the use of an intervention to treat patients (Neumann, 2017). Resource identification was guided by a tailored version of the Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (DATCAP) instrument (French, 2003), and we determined and categorized necessary resources utilizing a combination of administrative data and data collected using semistructured interviews of relevant study staff. We identified 12 jails in Massachusetts and Maryland and 2 prisons in Maryland and Pennsylvania. The number of individuals interviewed varied among sites but averaged between 6 and 8 individuals. The semistructured interviews included personnel who typically handle, and are therefore most familiar with, the day-to-day operations of the MOUD program. “Relevant personnel” varied across sites, but could include clinicians (doctors, nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners), social workers, managers/directors, information technology staff, health service administrators, counselors, superintendents, deputies, and sheriffs. We have included a template of potential interview questions in the appendix. The resources were grouped within the budget impact tool according to type (fixed, time-dependent, variable; defined below) and phase (implementation, sustainment). The tool utilizes the resource-costing method to value resources, which entails weighting the number of resource units utilized by a relevant unit cost. The end-user then customizes the tool by selecting the resources they would require for a desired MOUD delivery model, inputs the estimated demand for MOUD, and, if desired, replaces the existing nationally representative unit costs, with values that more closely reflect their environment. Additionally, we will make this tool publicly available on the “Resources” page of the website for the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH; www.cherishresearch.org). CHERISH is a NIDA-funded multi-institutional center of excellence whose mission is to develop and disseminate health economic research on health care utilization, health outcomes, and health-related behaviors that informs substance use disorder treatment policy, and HCV and HIV care of people who use substances. We can arrange guidance to those who are interested in a more in-depth application via the free economic consultation service offered by CHERISH, requests for which can also by submitted via the “Resources” page of the website (Murphy et al., 2018).

2.2. Measures

We categorized resources/costs as either “fixed”, “time-dependent”, or “variable”. Fixed resources/costs are those that are incurred only once and are not directly related to the number of persons treated. Examples of fixed costs could include construction or renovation of a space for dispensing medications, trainings, and one-time licensing fees. Time-dependent resources/costs are those that are recurring but fixed over a given time-period. Common examples of time-dependent resources/costs include rent/lease fees and annual licensing fees. Variable resources/costs are those that are a direct function of the number of persons treated, such as staff time and medications. The budget impact tool organizes the aforementioned resource categories into two phases: “implementation” and “sustainment”. The implementation phase is the period from inception, including all planning activities, until steady-state, and includes all fixed, time-dependent, and variable costs that would be incurred over that time-period. The sustainment phase is the period following steady-state and includes the time-dependent and variable costs that would be incurred on an annual basis, following the implementation phase. Fixed costs are not included in the sustainment phase, given that they are primarily required for purposes of implementation, and do not recur over time. The expected time until steady state is a modifiable feature in the tool, given that it will vary across facilities.

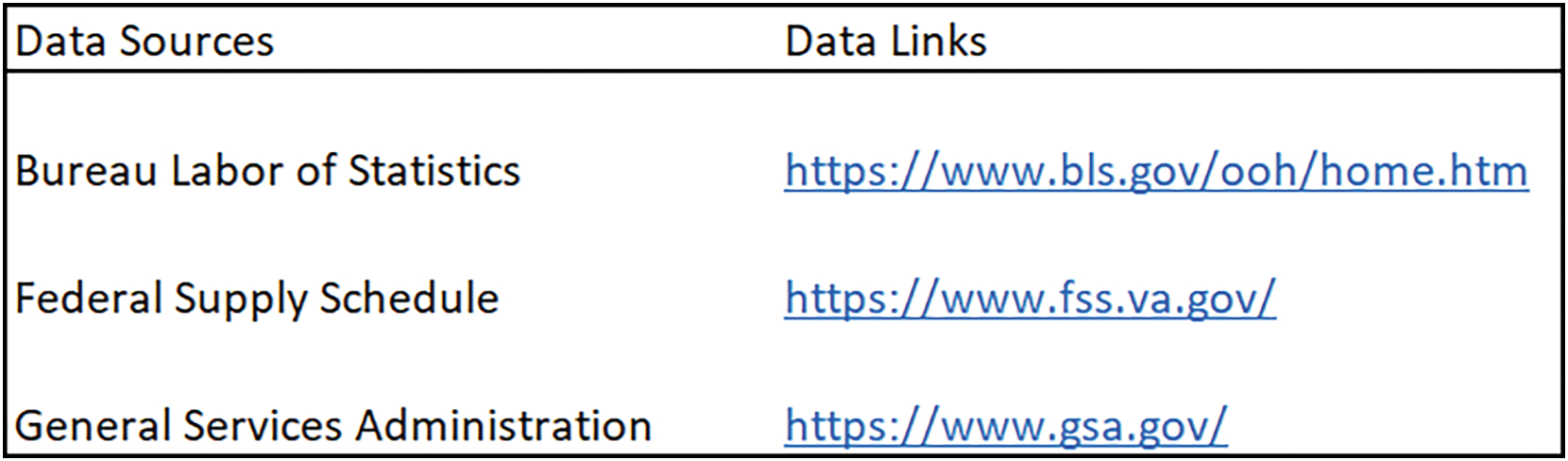

The tool contains nationally representative unit costs for valuing each resource; however, as mentioned above, the user can modify these. The hourly wages and fringe benefits for employers were derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021). The team derived other supply costs from the Federal Supply Schedule, including those associated with medications and drug-screening tests (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021). We used federal reimbursement rates to estimate travel costs, including food and lodging (U.S. General Services Administration, 2021). Contracted vendor fees were estimated by calculating the average costs from multiple Department of Correction facilities (Horn et al., 2018; National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017, 2020; Vermont Agency of Human Services 2016). We adjusted all monetary values to 2020 USD using the Consumer Price Index (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021a). The data source links to each of the nationally representative value will be included in the last tab of the tool (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Data Sources.

3. Results

3.1. The Tool

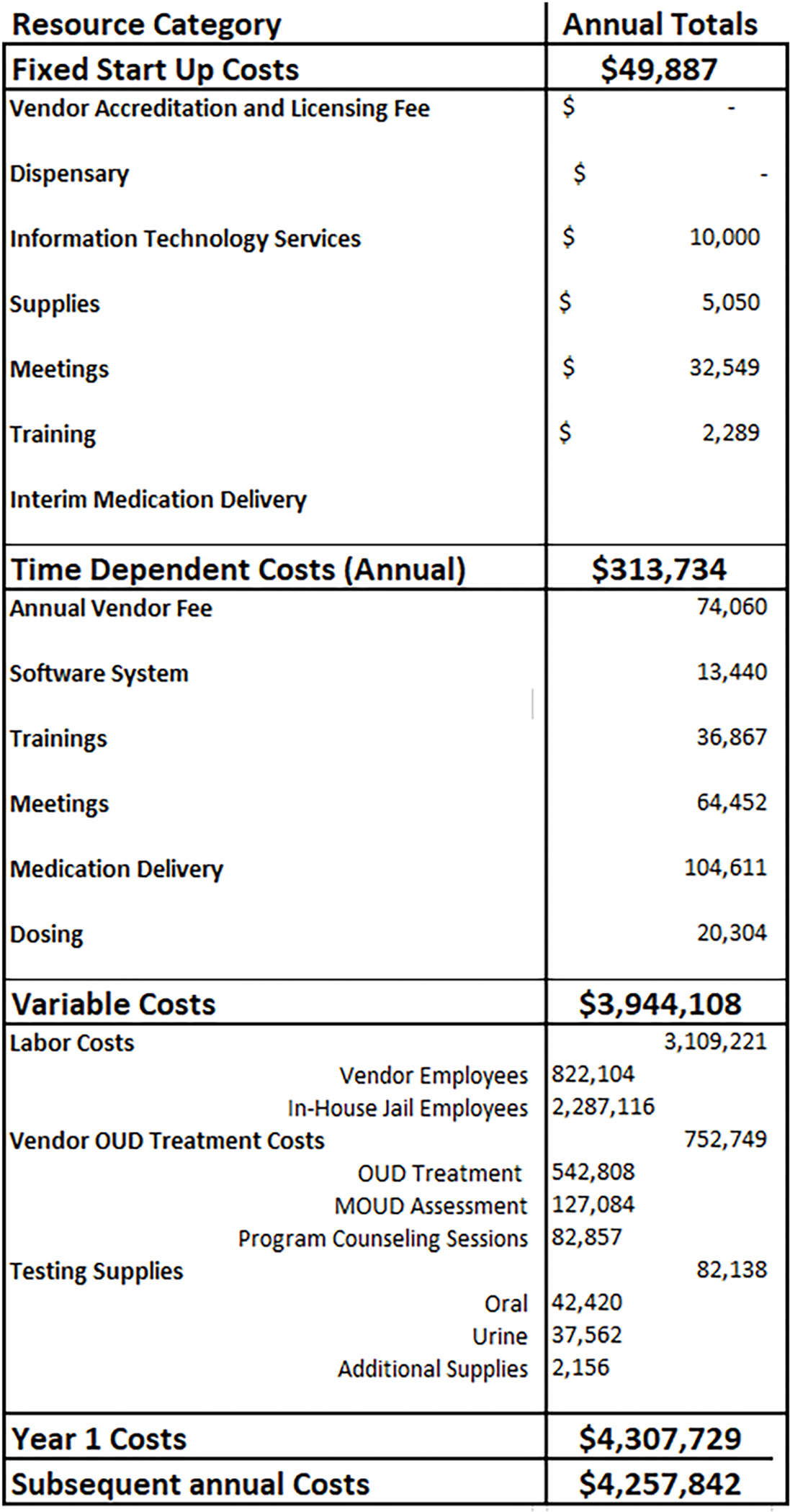

The budget impact tool includes 5 Microsoft Excel worksheets, with drop-down menus incorporated throughout to increase ease of use, and limit data-entry errors. The first worksheet is a dashboard that is automated by linking data from the other worksheets and displays the total costs of each resource category, by phase (see Figure 1. ‘Dashboard’). The remaining worksheets include the various resources that could be associated with different MOUD delivery models, and their associated unit costs. Thus, users will select the quantity of each relevant resource, adjust the unit cost if desired, and be able to view detailed cost estimates for each resource category.

Figure 1. Dashboard.

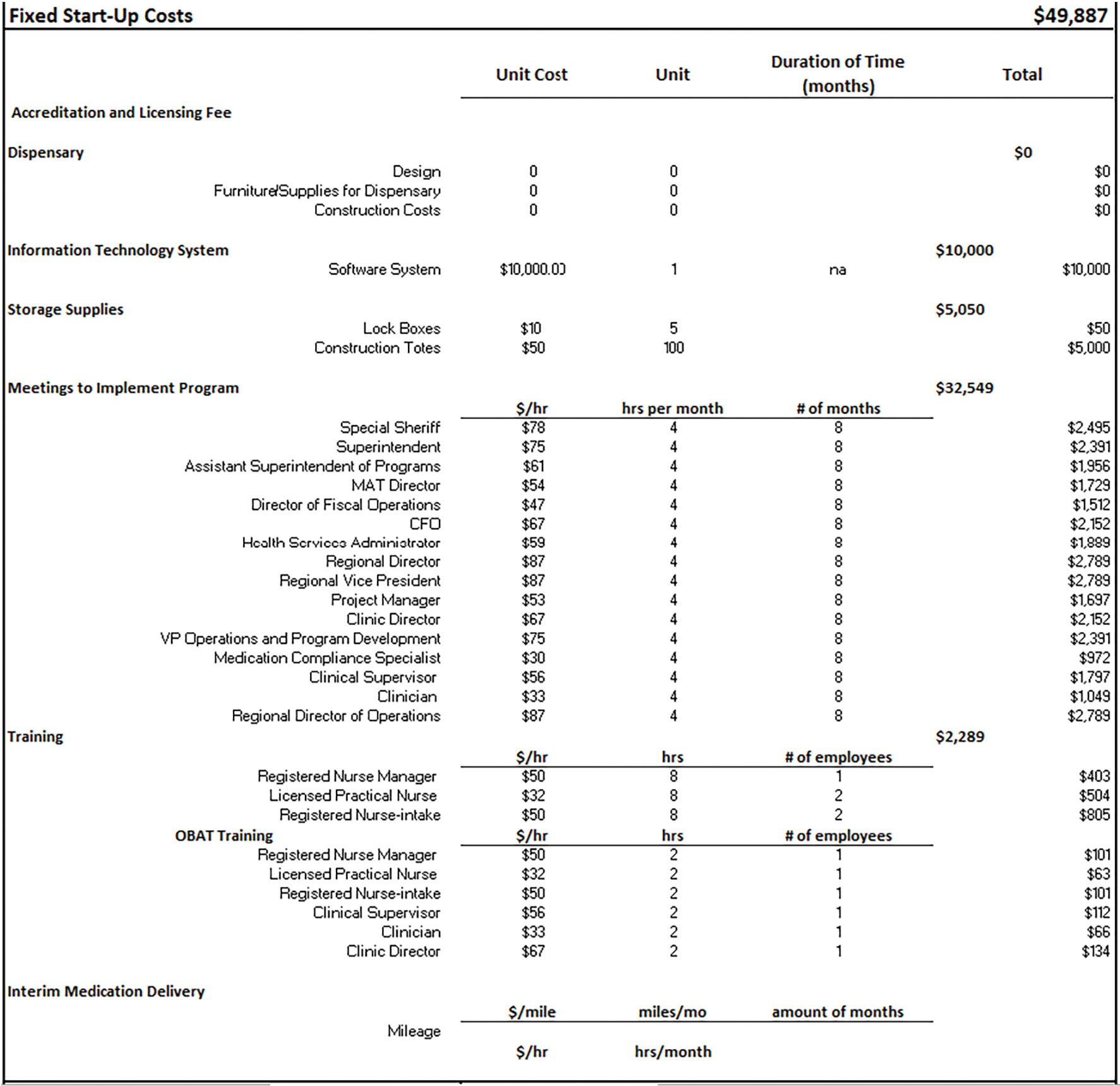

The second worksheet contains the fixed and time-dependent resources/costs (see Figure 2. ‘Start-Up Costs’ & Figure 3/3a ‘Time- Dependent Costs’). The fixed resource options include accreditation and licensing fees (e.g. those associated with one-time start up fees via vendor contract), dispensary design and construction, set-up of information technology services, supplies, meetings to implement the program, training, and interim medication delivery. The dispensary category pertains to those who plan to build a dispensary within the facility, typically with the intent of becoming an OTP. The interim medication delivery category captures the resources associated with a temporary medication delivery system for facilities planning to build a dispensary, but who are interested in offering medications right away.

Figure 2. Fixed Start-Up Costs.

Figure 3. Time-Dependent Costs.

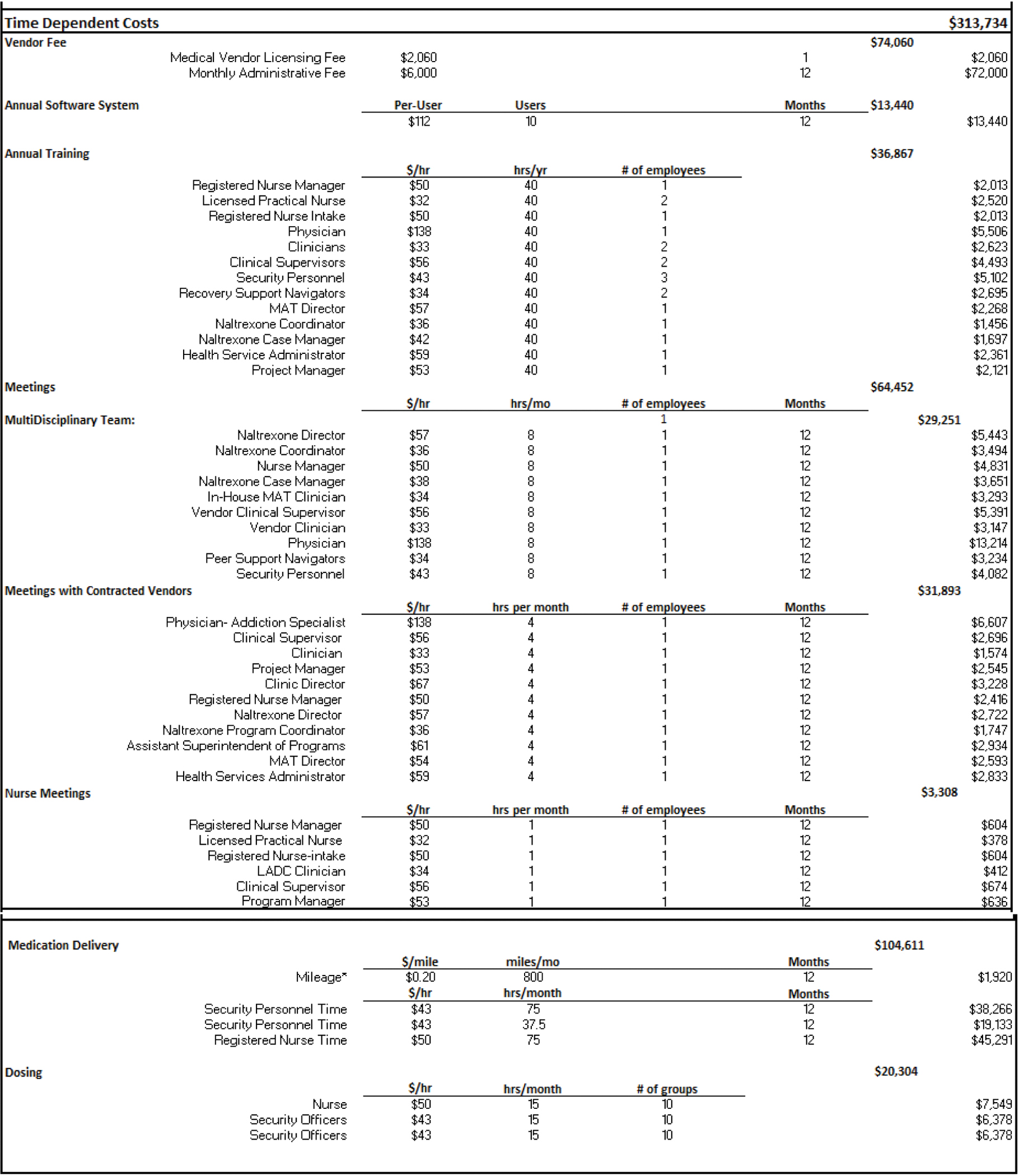

The time-dependent resource options include accreditation fees (e.g., those associated with on-going fees based on the vendor monthly/annual rate per facility), annual software system fees, annual orientation/trainings, weekly and monthly meetings, and medication delivery. The meeting components consist of the occupations and number of employees that would attend, and their time commitment during the year, all of which can be easily adjusted via drop down menus.

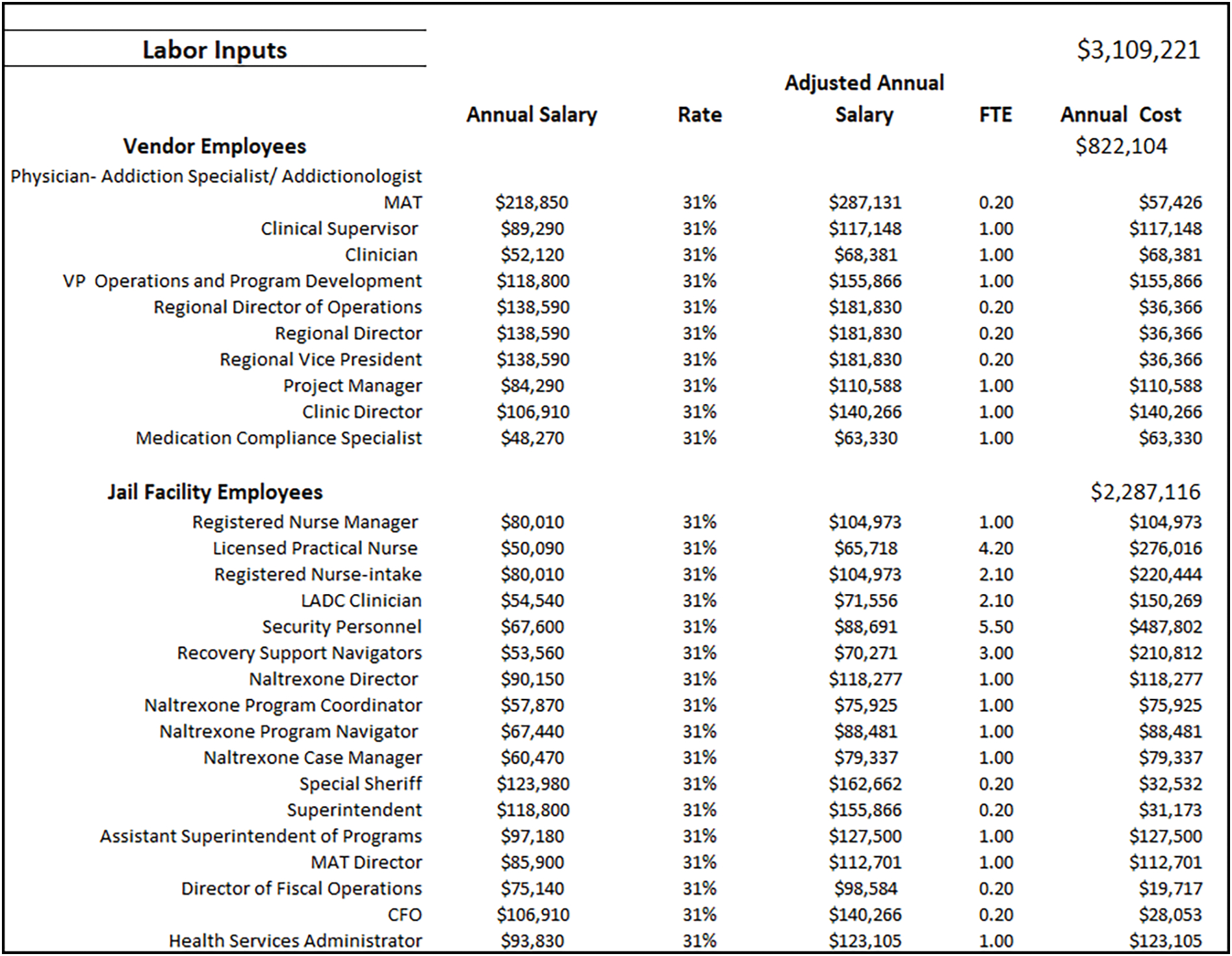

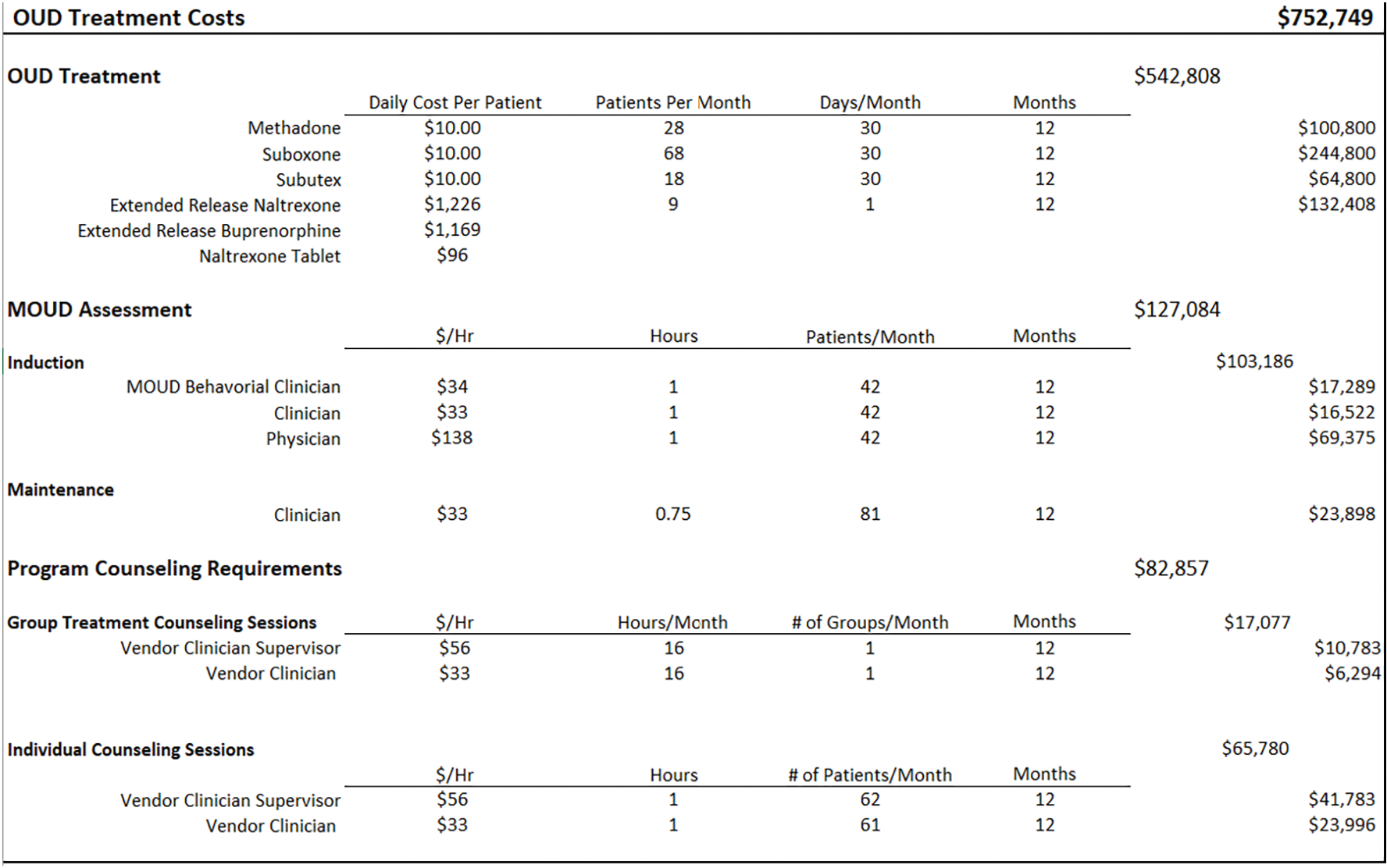

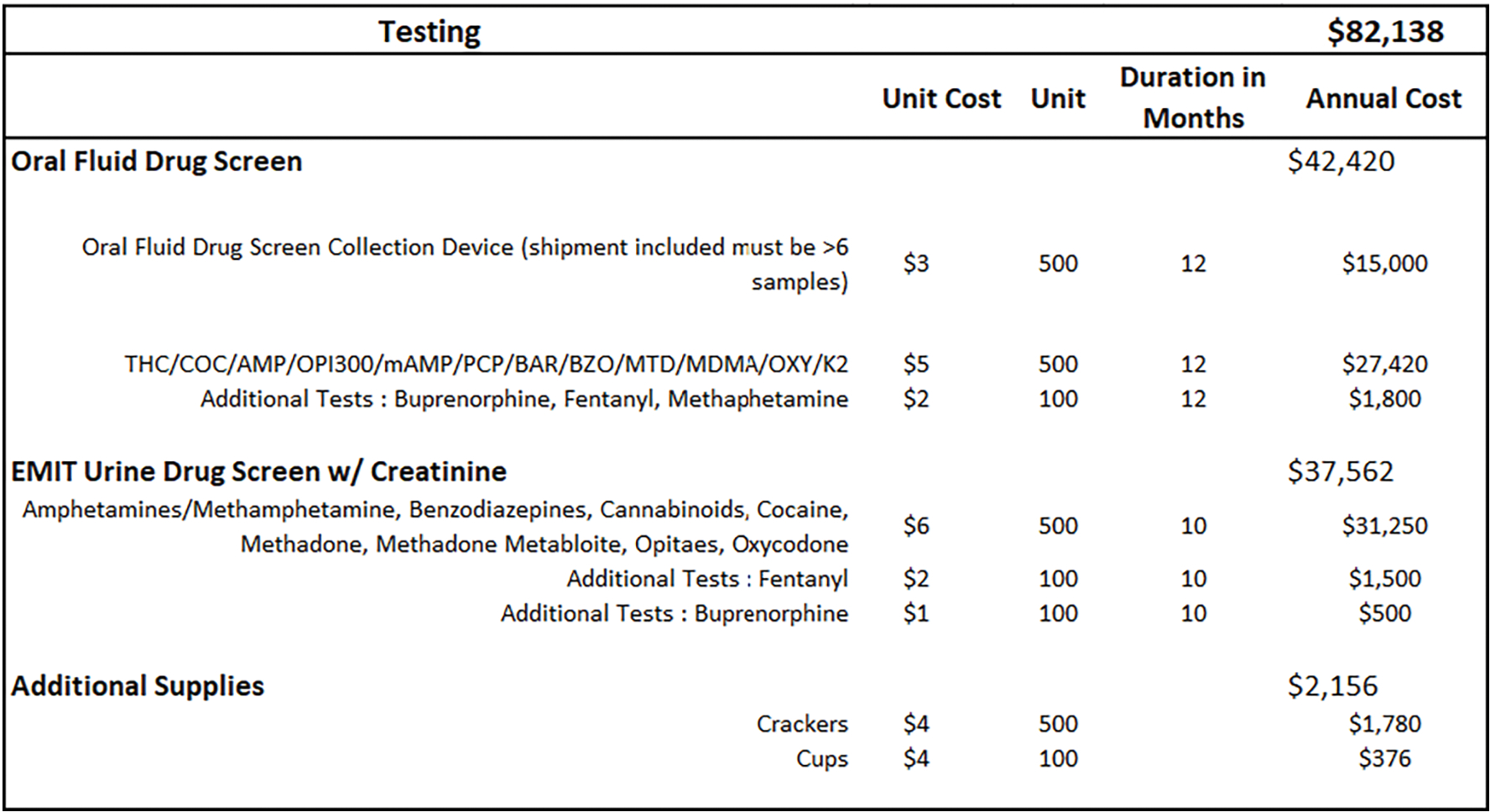

The next three worksheets include the variable resources that the team identified (therapy, labor, testing), and their associated unit costs. The labor tab consists of the various employee occupations involved in the MOUD Program, as well as their salary, fringe benefit rate, and the proportion of their full time equivalent (FTE) dedicated to the program (see Figure 4. ‘Labor’). An FTE = 1.0 implies 40 hours per week, or the equivalent of 1 full-time person. The therapy tab includes all currently approved/available MOUD types; the average daily medication cost, per-patient; the average number of patients treated per month for both induction and maintenance; group and individual counseling sessions; and the estimated number of treatment days per year (see Figure 5. ‘Therapy’). The average medication cost, per-patient, will be calculated according to delivery model; for example, facilities that contract with a vendor may pay a flat fee per-medication, per-patient, or they may pay according to dose. Depending on the facility’s MOUD program, patient requirements may also include weekly or monthly group and/or individual therapy sessions for the patients. The testing tab (see Figure 6. ‘Testing’) includes multiple types of oral and urine screens that a facility might use during the MOUD assessment.

Figure 4. Labor Costs.

Figure 5. Therapy Costs.

Figure 6. Testing Costs.

3.2. Applied Example

The scenario modeled here is one in which a correctional facility (jail or prison) chooses to offer all 3 MOUD using a combination of vendors and their own health care staff. The hired vendor would provide the buprenorphine and methadone, while naltrexone would be offered by the facility’s medical staff. The facility’s medical staff would administer all 3 medications. This type of agreement would be based on the vendor and jail/prison preference. We assumed the average number of MOUD patients per month would be 123 (86 on buprenorphine; 28 on methadone; and 9 on extended-release naltrexone). The number of patients seen, and the medication distribution were assumed according to our real-world observation including several recent and ongoing criminal legal-based trials targeting OUD.

The fixed resources for this example include meetings, trainings, software installation, and license/accreditation fees (see Figure 2). Based on our “real-world” observations, we assume that facility and vendor employees met weekly for an hour, for 8 months prior to the launch of the MOUD program, to discuss program logistics, policies, and procedures. Facility employees included a special sheriff, superintendent, assistant superintendent of programs, director of fiscal operations, chief financial officer, MOUD director, and health services administrator, while vendor employees consisted of a regional director, regional vice president, project manager, clinic director, vice president of operations and program development, medication compliance specialist, clinician, and clinician supervisor. As Figure 2 shows, the cost of these meetings totaled $32,549. An 8-hour start-up training was done for the facility’s health care staff (registered nurse [RN] manager, licensed practical nurse, RN) as well as a 2-hour office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) training for both nurses (facility and vendor) and supervisors to attend. The cost of training sessions came to $2,289. We further assumed that the facility required the installation of new software by information technology services to input confidential data regarding dosing and assessments for a fee of $10,000. Storage supplies were purchased for when the medication is retrieved from the OTP, to safely deliver methadone and buprenorphine to the jail/prison. The storage supplies consisted of lock boxes and construction totes, for a total of $5,050. The fixed start-up costs for this model totaled $49,887.

Figure 3 portrays the time dependent costs that occur on a weekly/monthly/yearly basis. The vendor charges the facility an annual fee to cover licensing and other requirements necessary to provide OTP services, and a monthly administrative fee to oversee the program, totaling $74,060 per year. The software system has a per-user cost of $112, and we assume 10 users for an annual cost of $13,440. We further assume that facility and vendor employees are required to attend an annual 40-hour training that provides an overview of employee responsibilities in the context of the MOUD program, and MOUD education. The training attendees include the vendor physician, 2 vendor clinical supervisors, 2 vendor clinicians, and 5 facility RNs, and a facility RN Manager. Additionally, a multi-disciplinary team meeting is held weekly to review patients’ treatment strategies; attendees include the physician, RN manager, clinic supervisor, clinician, and peer support navigators. Weekly meetings also occur between the vendor’s managers and facility staff, to discuss day-to-day operational issues, and review any program concerns. These meetings could include the physician, clinical supervisor, clinician, project manager, clinic director, RN manager, naltrexone director, naltrexone program coordinator, assistant superintendent of programs, MOUD director, and health services administrator. Monthly meetings also take place with the facility and vendor nursing staff to discuss any concerns of the MOUD program processes (e.g., avoiding diversion).

Methadone and buprenorphine are obtained daily by the jail/prison staff from a nearby OTP. We assume the OTP is approximately 10 miles from the jail facility. The staff inform the vendor of all relevant dose information for each medication, which are stored in the secure lock boxes and construction totes and picked up the next morning. Two correctional officers accompany the vendor nurse to retrieve the medication, which is then the facility’s health care providers administer. Following the provision of medication, the empty methadone vials are returned to the OTP by 1 correctional officer and a vendor nurse. The total number of miles accrued within a month is 800 and the total annual medication delivery cost comes to be $104,611 (see Figure 3).

The average number of incarcerated people on buprenorphine in a given month is 86. The method of trying to ensure the buprenorphine tablet is fully digested to avoid diversion is a lengthier and more resource-intensive process compared to methadone and extended-release naltrexone. The medication dosing for buprenorphine consists of one nurse and 2 security officers. The nurse crushes the buprenorphine tablet and places it under the patient’s tongue. The patient is required to sit and be observed by the security officers for about 15 minutes while the tablet dissolves. Patients are then given a cup of water to swish in their mouth, followed by a cracker and an additional cup of water to ensure the tablet was fully ingested. Dosing takes place in groups of approximately 10 people, and averages about a half hour per group. In this scenario the total buprenorphine administration costs come to $20,304. The total annual time-dependent cost for the MOUD delivery program would be $313,734.

The variable costs for this model include those associated with the labor, medication, and other supplies required to treat a particular patient. Upon arrival to the jail, all criminal-legal are screened by a urinalysis for recent substance use as part of the initial medical intake. If an incarcerated person states that they are on an active MOUD prescription, they will be maintained on that medication and dose, following verification of their prescription by the vendor’s staff and an additional, more comprehensive urinalysis. The process for those on maintenance takes an additional 30–45 minutes to speak with a clinician about the program requirements and what is expected of them to continue their medication during incarceration. Those who are interested in initiating an MOUD will send a request to be inducted and will speak to a facility behavioral health clinician who will complete three assessments (biopsychosocial, DAST-10, and DSM-5) to determine an OUD diagnosis. If the incarcerated person seems like an appropriate candidate for induction, a vendor clinician meets with the patient to discuss what is required of the program (urinalysis, group sessions, medical requirements) and documents it in the software system, which takes approximately an hour. Once all the appropriate assessments are completed, the incarcerated person is seen by a physician, which may take up to an hour to speak about concerns and dosage. The MOUD program requirements by the vendor include a 1-hour weekly group therapy session, as well as monthly individual behavioral health sessions held by the vendor clinicians.

The therapy tab (Figure 5) includes all potential medication formulations; the mean, per patient cost for each medication; number of patient days; and the labor costs associated with different types of visits (e.g., induction vs maintenance). We assume, based on our real-world observations, a vendor-initiated medication cost of $10 per person, per-day, for oral buprenorphine and methadone. The cost of extended-release naltrexone and buprenorphine, which are typically given just prior to release from incarceration, are estimated to be $1,226 and $1,169, respectively, according to the Federal Supply Schedule (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021). The estimated cost for the MOUD maintenance assessment is $25/patient, and the induction process cost is $205/patient. Assuming an average of 123 patients per month, with 42 induction visits and 81 visits being maintenance, the total annual cost of induction and maintenance would be $103,186 and $23,898, respectively. The facility offered four 1-hour group therapy sessions per week, resulting in 16 hours per clinician, times 2 clinicians per month. The total cost of group therapy would be $1,423 per month ($17,077 annually). The individual therapy sessions would amount to $65,780 annually. The ‘testing’ tab contains different types of drug screening tests used for maintenance and induction referrals. We assume that random urine screens are done throughout each month to ensure compliance during treatment. We also included additional testing supplies, such as crackers and cups that are used for those on buprenorphine. The annual costs for the urine test, mouth swabs, crackers and cups were $82,138.

Assuming the facility would reach steady state by year 2 of the program, that all implementation costs would be spread out over the first 12 months of the program, and an average of 123 patients/month, the total cost to the facility over that period would come to $4,307,729 or $2,919/patient. Following the implementation period, and the payment of the fixed start-up costs, the annual estimated cost of sustainment would be $4,257,842 or $2,885/patient.

4. Discussion

The care that jails and prisons provide is critical to fighting disease, and promoting physical and behavioral health, which, in the case of OUD specifically, has been shown to promote both public and economic health. The customizable budget impact tool described above is designed to provide practical information on the types of costs incurred by jails/prisons in the implementation and sustainment phases of an MOUD program. Correctional facilities need time to develop the necessary protocols and calculate the demands for services as well as possibly coordinating with other agencies (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020). This tool can help to adjust the needs of health care services for MOUD. The CHERISH website would provide a link to the tool and a request can be made via the “Resources” page of the website.

The example presented here does not reflect that of a specific facility’s MOUD program, but rather one of many possible uses of the tool. Facilities will undoubtedly identify resources/costs associated with implementation or provision of MOUD at their site, that are not in the tool. Feasible MOUD delivery models will vary by site, according to their location (e.g., proximity to an OTP), capacity, availability of (grant) funding, existing personnel, etc. While a larger budget would likely be needed to implement an MOUD program, it will be important for state policymakers to evaluate not only the relative program costs of feasible models, but also their relative effectiveness, including the potential downstream cost offsets that would occur as a result of successful treatment (e.g., lower recidivism; less high-cost health care utilization following reentry to the community, such as ED visits; reduced utilization of state safety-net programs, etc.).

To the best of our knowledge, little-to-no evidence exists on the relative effectiveness of various MOUD delivery models in jails or prisons; however, we plan to explore this question, while controlling for site characteristics, in future work, following the completion of the aforementioned clinical trials. Fortunately, the tool should be sufficiently flexible/customizable to accommodate any such occurrence. Moreover, the publicly available tool will be updated over time, as additional studies are completed and new resources are identified.

5. Conclusion

The comprehensive, customizable, and publicly available budget impact tool presented in this article is the first of its kind. The tool will serve as a valuable asset to jail/prison leadership, policymakers, and other stakeholders interested in identifying/estimating the resources and costs associated with alternative MOUD delivery models, from the planning stages through sustainment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) has shown benefits in jail/prison settings

An increasing number of jails/prisons offer MOUD, but often face fixed budgets

Budget impact tool helps jails/prisons estimate implementation and sustainment costs

Acknowledgments

Danielle Ryan, Sean M. Murphy: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing-Original draft preparation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Ivan Montoya, Peter Koutoujian, Kashif Siddiqi, Philip Jeng, Techna Cadet, and Edmond Hayes: Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, and Validation.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (UG1DA050067, R01DA046721, P30DA040500).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing Interest

No competing interests to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, & Paar DP (2009). Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA, 301(8), 848–857. 10.1001/jama.2009.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, & Roland CL (2011). Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med, 12(4), 657–667. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, and Berzofsky M. (2017). Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudaspji0709.pdf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Occupational Outlook Handbook. Retrieved 7/28 from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/home.htm

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Nuro KF, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, & Rounsaville BJ (2008). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. Am J Psychiatry, 165(7), 881–888. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, White HR, Fleming CB, & Haggerty KP (2011). Is nonmedical prescription opiate use a unique form of illicit drug use? Addict Behav, 36(1–2), 79–86. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deck D, Wiitala W, McFarland B, Campbell K, Mullooly J, Krupski A, & McCarty D (2009). Medicaid Coverage, Methadone Maintenance, and Felony Arrests: Outcomes of Opiate Treatment in Two States. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 28(2), 89–102. 10.1080/10550880902772373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Ali H, Hickman M, & McLaren J (2011). Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction, 106(1), 32–51. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French MT (2003). Brief Drug Abuse Treatment Cost Analysis Program (Brief DATCAP): Program Version.

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Couvillion KA, Sudec LJ, O’Grady KE, Vocci FJ, & Shabazz H (2015). Buprenorphine Treatment for Probationers and Parolees. Subst Abus, 36(2), 217–225. 10.1080/08897077.2014.902787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE, & Vocci FJ (2014). A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine: prison outcomes and community treatment entry. Drug Alcohol Depend, 142, 33–40. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BDL, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, & Rich JD (2018). Postincarceration Fatal Overdoses After Implementing Medications for Addiction Treatment in a Statewide Correctional System. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 405. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BP, Li X, Mamun S, McCrady B, & French MT (2018). The economic costs of jail-based methadone maintenance treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 44(6), 611–618. 10.1080/00952990.2018.1491048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, and Glaze LE,. (2006). Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/mental-health-problems-prison-and-jail-inmates

- Kerr T, Fairbairn N, Tyndall M, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, & Wood E (2007). Predictors of non-fatal overdose among a cohort of polysubstance-using injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 87(1), 39–45. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, & O’Grady KE (2009). A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. J Subst Abuse Treat, 37(3), 277–285. 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O’Grady K, Fitzgerald TT, & Wilson M (2007). A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 1-month post-release. Drug Alcohol Depend, 91(2–3), 220–227. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Picher CE, Feder KA, & Saloner B (2017). Only One In Twenty Justice-Referred Adults In Specialty Treatment For Opioid Use Receive Methadone Or Buprenorphine. Health Aff (Millwood), 36(12), 2046–2053. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, Vickerman P, Deren S, Bruneau J, Degenhardt L, & Hickman M (2012). Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 345, e5945. 10.1136/bmj.e5945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Lee JD, Hershberger J, Joseph H, Marsch L, Shropshire C, & Rosenblum A (2009). Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend, 99(1–3), 222–230. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Woody GE, Juday T, & Kleber HD (2001). The economic costs of heroin addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend, 61(2), 195–206. 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00162-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M, & Breen R (2003). Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10.1002/14651858.cd002209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Jeng PJ, Poole SA, Jalali A, Vocci FJ, Gordon MS, Woody GE, & Polsky D (2020). Health and economic outcomes of treatment with extended-release naltrexone among pre-release prisoners with opioid use disorder (HOPPER): protocol for an evaluation of two randomized effectiveness trials. Addict Sci Clin Pract, 15(1), 15. 10.1186/s13722-020-00188-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Laiteerapong N, Pho MT, Ryan D, Montoya I, Shireman TI, Huang E, & McCollister KE (2021). Health economic analyses of the justice community opioid innovation network (JCOIN). J Subst Abuse Treat, 108262. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Leff JA, Linas BP, Morgan JR, McCollister K, & Schackman BR (2018). Implementation of a nationwide health economic consultation service to assist substance use researchers: Lessons learned. Subst Abus, 39(2), 185–189. 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, McPherson S, & Robinson K (2014). Non-medical prescription opioid use and violent behaviour among adolescents. J Child Adolesc Ment Health, 26(1), 35–47. 10.2989/17280583.2013.849607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, & Polsky D (2016). Economic Evaluations of Opioid Use Disorder Interventions. Pharmacoeconomics, 34(9), 863–887. 10.1007/s40273-016-0400-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine,. (2019). Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy. (2020). Three Approaches to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in State Departments of Corrections. Retrieved 07/28 from https://www.nashp.org/three-approaches-to-opioid-use-disorder-treatment-in-state-departments-of-corrections/

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. (2021). Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in Correctional Settings. Retrieved 07/28 from https://www.ncchc.org/opioid-use-disorder-treatment-in-correctional-settings

- National Council for Behavioral Health VS (2020). Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Jails and Prisons. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/MAT_in_Jails_Prisons_Toolkit_Final_12_Feb_20.pdf?daf=375ateTbd56

- National Governors Association ACA (2021). A Roadmap for States to Reduce Opioid Use Disorder for People in the Justice System. https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/NGA-Roadmap-on-MOUD-for-People-in-the-Justice-System_layout_final.pdf

- National Governors Association ACA (January, 2021). Expanding Access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Corrections and Community Settings: A Roadmap for States to Reduce Opioid Use Disorder for People in the Justice System.

- Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, & Ganiats TG (2017). Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine (2nd ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Edens JF, Carter CR, & Ortiz MM (1998). Prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders among prison inmates. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 24(4), 573–587. 10.3109/00952999809019608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana L, Ritzwoller DP, Campbell M, & Block EP (2022). Using economic evaluations in implementation science to increase transparency in costs and outcomes for organizational decision-makers. Implement Sci Commun, 3(1), 40. 10.1186/s43058-022-00295-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, D. M., Winston E,. (2018). Criminal Justice Kentucky Treatment Outcome Study FY 2017. https://cdar.uky.edu/CJKTOS/Downloads/CJKTOS_FY2017_Report_Final.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep19-matusecjs.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings. HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS Rockville, MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved May 31, 2022 from https://www.samhsa.gov/

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2017). Prison Health Care: Costs and Quality. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/10/sfh_prison_health_care_costs_and_quality_final.pdf

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2020). Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in Jails and Prisons. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/04/opioid-use-disorder-treatment-in-jails-and-prisons

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). Federal Supply Schedule Services. Retrieved 07/28 from https://www.fss.va.gov/

- U.S. General Services Administration. (2021). General Services Administration. Retrieved 07/28 from https://www.gsa.gov/travel/plan-book/transportation-airfare-pov-etc/privately-owned-vehicle-pov-mileage-reimbursement-rates

- Vermont Agency of Human Services (2016). Medication-Assisted Treatment for Inmates. Retrieved 08/06/2021 from https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Legislative-Reports/DOC-MAT-Eval-report-final.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.