Abstract

Aim

To identify and describe the impact areas of a newly developed leadership development programme focussed on positioning leaders to improve the student experience of the clinical learning environment.

Background

There is a need to consider extending traditional ways of developing leaders within the clinical learning in order to accommodate an increased number of students and ensure their learning experience is fulfilling and developmental. The Florence Nightingale Foundation implemented a bespoke leadership development programme within the clinical learning environment. Identifying the areas of impact will help to inform organisational decision making regarding the benefits of encouraging and supporting emerging leaders to undertake this type of programme.

Method

For this qualitative descriptive study, eight health care professionals who took part in a bespoke leadership development programme were interviewed individually and then collectively. The Florence Nightingale Foundation fellowship/scholarship programme is examined to determine impact.

Results

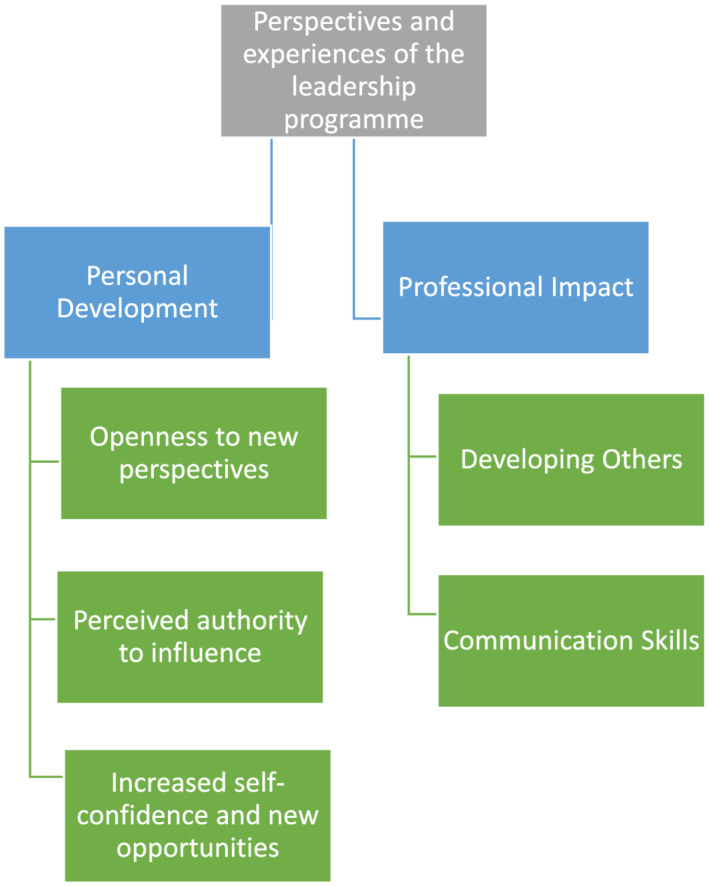

Two key themes were described in relation to impact of the programme. These were ‘Personal Development’ and ‘Professional Impact’. The two key themes comprised several subthemes. The notion of time and space to think was subsumed within each theme.

Conclusion

Data highlights that the Florence Nightingale Foundation programme had a distinct impact on participants by transforming thinking and increasing self‐confidence to enable changes to make improvements both within their organisations and at national level.

Implications for Nursing Management

Health care managers must continue to invest in building leadership capacity and capability through programmes that can help position individuals to realize their potential to positively influence health outcomes and wider society.

Keywords: allied health professional, leadership development, midwives, nurses

1. INTRODUCTION

This study provides insight into the experiences of a cohort of nurses, midwifes and allied health professionals (AHPs) who embarked on a novel 12‐month programme of leadership development, with a focus on enabling change and improvements in the learning environment. In this paper, we draw upon participants' experiences and perspectives of how the programme facilitated their development as leaders. As far as we know, the approach to leadership development outlined here is innovative in that it is the first to extend traditional approaches to leadership development (Paton et al., 2021) by incorporating health care professionals (HCPs) from various specialties. It was anticipated that the programme would encourage participants to engage in a process of critical reflection whereby they would question their own leadership styles, as well as one another's points of view about leadership. This reasoning was underpinned by adult learning theory (Mezirow, 2000), which holds that a learner can transform their thinking by confronting and questioning theirs (and their peers) established preferences/worldviews. Therefore, we predicted that programme participants would motivate one another, through discussion and reflection on leadership challenges, and, ultimately, come to see these challenges in new ways (Bass & Riggio, 2006, in Echevarria et al., 2017).

1.1. Programme overview

The programme was designed to respond to the specific context and development needs of clinical educators and comprised a series of experiential development days which focussed on (1) understanding of self and impact of self on teams; (2) personal presence and impact; (3) stepping into authority and having influence; (4) influencing change and measuring impact; and (5) writing for publication and disseminating learning. The programme was delivered remotely, online. Prior to the start of the programme (April 2021), programme participants were presented with a programme specification, outlining the key information and learning outcomes for the above‐referenced experiential development days.

Programme participants were supported and encouraged throughout to pioneer change and improvements in patient and health outcomes, thereby, honouring Florence Nightingale's legacy that still resonates in nursing and health care today (Chatterton, 2019). Clinicians (programme participants) were seconded from their substantive role to undertake the programme, as well as complete a quality improvement (QI) project, which focussed on improving the experience and capacity of the clinical learning environment. Due to the uniqueness of this programme, there is a lack of existing literature on comparable programmes. It is therefore important to identify the areas in which this programme is reported to have been impactful for participants so that measurable influences can be determined for future programmes.

2. BACKGROUND

There is continued concern regarding the shortage of nurses and midwives in the United Kingdom (UK) (Beech et al., 2019; National Audit Office, 2020). Even before the Covid‐19 pandemic, there were reports of increased rates of stress, absenteeism, burnout and high numbers of health care students leaving courses (Bakker et al., 2019; Health Foundation, 2018; Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2020). In terms of health care students, team culture is a notable factor for the observed variance in the quality of HCPs' experiences, and subsequent levels of satisfaction (Labrague, 2021). Enhancing the experience for health care learners is vital to ensure the production and retention of a highly skilled and confident future health care workforce (Panda et al., 2021).

Research has emphasized the positive impact of leadership for shaping organisational cultures and producing positive outcomes for staff, students, and patients (Cummings et al., 2021; Kline, 2019; Sholl et al., 2017). However, workforce pressures often mean less time to devote to leadership development (Coventry et al., 2015; Nash & Garratt, 2021). It is important that leaders are invested in developed and positioned to positively influence, innovate and improve traditional models of clinical learning to support students and ensure their learning experience is fulfilling and developmental. This may be one way to improve retention and reduce attrition rates.

There is a need to find innovative approaches to leadership development in order to increase capacity for high‐quality learning within the clinical environment, which students experience as both fulfilling and developmental. In the clinical learning environment, where traditional models have continued to be implemented, evidence suggests that the workforce feels a significant burden to support students' learning needs (Hanson et al., 2018). As a consequence, students may experience inadequate learning opportunities. In the United Kingdom, this burden has been mitigated by appointing clinicians who have a dedicated role co‐ordinating and supporting students, known as clinical educators or clinical placement managers (Magnusson et al., 2007). Clinical educators are at the centre of the learning process and can have a positive impact on student achievement and attrition rates (Arkan et al., 2018), often supporting students to navigate the challenges posed by clinical practice environment (Cant et al., 2021; Kalyani et al., 2019; Rafati et al., 2020). These individuals are in a position to influence change, implement innovations and drive improvements in both the clinical and academic learning environments (Scott, 2018). To meet these unique challenges, aspiring clinical educators must develop the relevant leadership skills. Regardless of the importance of these roles in both clinical education and practice (van Diggele et al., 2020), there is little leadership or career development available in this area, in the United Kingdom.

2.1. Aim

To identify and describe the impact areas of a newly developed leadership development programme focussed on positioning leaders to improve the student experience of the clinical learning environment.

3. METHODS

3.1. Ethical considerations

The University of Nottingham research ethics committee granted ethical approval (FMHS 218‐0321). Participants gave informed consent and were made aware that their involvement was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw consent at any time.

3.2. Study design

We conducted a qualitative descriptive (QD) study using a sample of individuals who had joined a newly designed leadership development programme for clinical educators. QD was considered appropriate for this study as we sought to gain a broad insight into the impact of the Florence Nightingale Foundation (FNF) programme, while focussing on participants' views and experiences of developing leadership on the programme and planned to use multiple data sources (individual and focus group interviews) (Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000).

3.3. Participants

Participants (n = 8) were all female, nurses (n = 4), midwifes (n = 1) and AHPs (n = 3) working in the UK National Health Service (NHS) in the Southeast of England. No other demographic data were collected. All were seconded from their substantive role for 12 months to follow the FNF leadership development programme while simultaneously working on a QI project focussed on improving the student experience within the clinical learning and education environment.

3.4. Data collection

Data were collected at three points over the course of a 9‐month period from July 2021 to February 2022. Semi‐structured interviews were undertaken by the lead author at 3 months into the programme and again at 6 months into the programme. The main exploratory questions for the interviews were the following:

‘Can you describe your experience of transitioning from your clinical role to the leadership development programme?’

‘What have your experiences of developing as a change agent been so far?’

All interviews were conducted online using video conferencing software and lasted between 35 and 50 min. One focus group was undertaken at 9 months into the project (length = 80 min). Only five (n = 5) participants attended the focus group. Interviews and focus group resulted in a total of 624 min of data. The main exploratory question for the focus group was as follows:

‘From your experience of the programme so far, on reflection, what impact has the programme had?’

Follow up questions were used throughout to enhance to quality and richness of the data. Emerging specific topics were noted and discussed with participants to explore in more detail and generate detailed examples (Tong et al., 2007).

3.5. Data analysis

The lead author, who had also conducted the interviews, transcribed the audio‐recordings verbatim. This ensured in‐depth familiarity with the text. Two analysts (CB & AC) then independently coded the first three transcripts, each creating separate interpretations and themes. The second analyst (AC) was independent from the project. A meeting then took place between the two analysts to discuss the initial coding and resolve any disagreements. Emerging themes were discussed in full and discussions were focussed on the refinement of themes. Draft themes were reviewed by the co‐investigators. This process resulted in a high‐level of agreement among the team. Once themes were established, extracts were taken from the five the remaining transcripts and organised under the derived codes. Participants were invited to comment on whether they felt the themes accurately reflected their experiences. Affirming comments from participants demonstrates the authenticity of the results. As an approach, qualitative description offered a practical straightforward method for understanding participants' perspectives regarding areas of the programme that were impactful for them (Sandelowski, 2000).

4. RESULTS

Participants discussed two core themes in relation to impact of the programme. These were ‘Personal Development’ and ‘Professional Impact’. The two core themes comprised subthemes (Figure 1). Subsumed within each theme was the idea that having the time and space to think was important for personal and professional growth to occur.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the two core themes and subthemes emerged during data analysis

4.1. Personal development

Participants reported being motivated to apply for to the FNF programme and had been actively searching for a route that could provide experience to help them develop a future strategic position and fulfill their passion for working in the clinical learning/educational environment. At each point of data collection, participants reflected on the impact of the course on their personal development.

‘It's been such a journey, psychologically for me … having time to get to know what my leadership style is and how I cope with stress’ [P11]

‘From a personal perspective, it has re‐motivated me, it has changed me….prior to starting the programme I think I was in a bit of a personal rut…..and thinking that we were always doing things the same way’ [P19]

‘I've learnt so much about myself … some of the session with RADA 1 have been really helpful because I am doing a lot of presenting and….I have learnt a lot out how to manage my anxieties and put things into perspective….and I have done things and spoken to people that I would never have spoken to’ [P14]

Participants described the unique aspects of the programme and the influence these elements had on their personal development. This was evident in terms of developing openness to hearing new perspectives on leadership.

4.2. Openness to new perspectives

Participants reflected that the design of the FNF programme, and how it had enabled them to share experiences of leadership with HCPs from various backgrounds. This was felt to have facilitated an openness to new perspectives.

‘To be with like‐minded people who are really passionate for change, despite us coming from different backgrounds, it was just really refreshing… it makes me step back from what I know and to be open to their suggestions and their insights’ [P9]

‘In the last action learning, I jotted down a couple of names of the other scholars and fellows, and thought I might actually speak to them and see if they have got any views on these things’ [P15]

‘I am thinking more about how the changes that we want to see happen also benefit other people and their agendas and what they want. I think prior to the scholarship I perhaps would not really have thought about things from that angle’ [P19]

The programme days, where participants came together as a cohort, provided a sense of support and a space for feedback from peers. This was felt to be important in helping participants to develop thinking about how others perceived them as a leader; and to reflect on their own leadership style. Openness to various perspectives was felt to provide participants with an opportunity to ‘reframe’ how they view themselves as leaders and help them to change existing habitual ways of working.

‘One of the things it's given me time not only to reframe me but reframe the way that I work and come away from the normal’ [P9]

Reflective space was something that all participants talked about in terms of having broadened their thinking, so much so that confidence was felt to have increased as a result of individuals beginning to see themselves as experts in their own right.

4.3. Perceived authority to influence

Participants expressed a sense of increasing awareness of themselves as the expert in their particular field of clinical practice and how they had started to develop confidence and self‐belief in their ability to influence as leaders.

‘Some of the previous experiences have been trying to do some of this stuff. Particularly the QI work, I've been trying to do those things. It's so strange because now I feel like I've been given permission to do it. Which kind of, by default, makes me the expert. So, then it makes me feel like I have got a stronger voice to talk about those things’ [P12]

Moving beyond their established networks and becoming part of a wider national network helped participants engage in new conversations. The feeling of developing a sense of agency occurred because they believed they had permission to do something different.

‘People are now listening to me, they are engaging in conversations. Not that they were not before, but I've got more free rein, I suppose, now. I'm allowed to ask those questions … I can ask those questions; I can ask them on a wider field as well. I have gone national with my project’ [P13]

Consequently, participants conveyed a feeling of being empowered. This enabled them to feel they could begin to implement change and make improvements. This was less about their day‐to‐day clinical performance but more about insights gained from the leadership course and their developing awareness of their existing expertise.

‘I'm actually helping the Trust design a pathway at level 7 for nurses. And we are having our voice heard, which is wonderful… I've never really thought I'd have a voice, strategically. And I think because of the FNF programme, it's very slow, but I think that we are beginning to get a strategic voice, which would be incredible. I never would have had that before’ [P15]

4.4. Increased self‐confidence and new opportunities

Growing recognition of, not just themselves as leaders, but a recognition that other people have started to acknowledge them as the ‘go to’ person led to increasing self‐confidence and self‐belief in relation to recognition of their extant wealth of tacit knowledge and experience.

‘What has happened in the past six months is people have really recognized me as somebody … I guess having that knowledge it became a magnet on things, people would ask me questions that they feel I could answer’ [P11]

‘I did not know I was relevant …. I suppose I have gained confidence to apply some of the skills I probably already had that were not given an opportunity or space to be used’ [P9]

‘Now I think I'm definitely more confident in what I am bringing to those sorts of positions. And it feels that there's less mystery around this what is being a leader kind of thing, it has gone a little bit which is good’ [P19]

Participants reported how various opportunities had arisen from both becoming recognized as a source of expert knowledge and having access to a national network of health care leaders via the FNF programme.

‘HEE 2 have come to me, national have come to me and asked me to lead on something, I never expected that conversation to happen’ [P9]

‘What's interesting is the links that I've had with people that I never would have thought. Like, Health Education England. Who talks to anyone in Health Education England, honestly?’ [P14]

‘At the moment now because I'm doing the FNF leadership programme I'm part of the senior management team, which obviously I wasn't before. And a couple of people have said that they need to really think about what I do next. Because they do not want me to leave the senior management team, they want me to have a role within it, and to think about that’ [P19]

Participants understood that the programme cohort of specialist HCPs had broadened their existing network. This was useful in terms of the opportunity to discuss the potential barriers to sustaining change within the learning environment. Thinking critically together and considering how other people experience them as a leader was made possible by time spent away from their substantive roles.

4.5. Professional impact

4.5.1. Developing others

Participants talked about using the skills they had developed on the FNF leadership programme to develop others. They also talked about the broader impact of the programme on the learning environment—as well as generating improvements to patient care.

‘The impact has actually still been the ability to affect others and grow others’ [P9]

‘Some of the leadership stuff that we have talked about, I've been able to share, and I've been able to share with senior nurses’ [P15]

‘Within six months of doing the scholarship we have finally got our funding for an ICU psychologist. We've established a follow‐up clinic so patients that have been discharged from ICU, now we have the resources and the opportunity to invite them back into clinic and see how they are’ [P11]

Participants were able to appreciate they were developing as leaders who could influence change, and they could see their agency in the change process.

4.6. Communication skills

Time to reflect and think about ‘the‐self’ as a developing leader was a welcome facet of the programme. Participants discussed the value of having opportunities to stop, pause and reflect on their leadership style. This provided headspace to reflect on communication skills and different ways of communicating as leaders.

‘So much transferable skills if I had not done this programme, what stands out is the lean. … having the time and resources to learn lean has given me a lot of knowledge and empowered me to speak to a lot of senior people’ [P11]

‘Some of the things around the different aspects of conversations that you might have with people, and how to get the best out of those, and how to prepare for them, that was all really quite educational. I'd never taken a step back and thought about that side of things at all’ [P19]

Participants reported that, prior to starting the programme, they rarely had time for reflection on leadership, or to work on specific projects that might improve the learning environment. The experience of having time was reported to be both physically and mentally refreshing.

The cohort of professionals for various backgrounds and specialities was felt to allow different conversations that participants felt they might not have otherwise had. This was felt to expand thinking by stepping out of silo working. Having various conversations within the cohort and sharing the leadership journey was also felt to induce confidence to communicate with people outside of their organisation. This increased confidence to communicate and network with external stakeholders was felt to be influential for creating positive change.

‘I think that developing those relationships and being able to say to people this is why I'm suggesting this change, and this is what I want to achieve. So, I think probably the main skill is having the communication skills, the confidence, but also developing relationships with people, which I had perceived as being a barrier because it was an organisation that I wasn't used to’ [P14]

Thinking time gave participants the opportunity to unpick interpersonal interactions, and social processes, which form part of the culture of the health care teams more broadly.

‘What the programme has taught me is in order to solve problems and in order to sustain the change that you want to see, you really need to step back and really study what's going on. What's driving this, what do the staff feel like, what does the patient feel like, and what are the things around us that we can really influence in order to sustain change?’ [P11]

5. DISCUSSION

Proactively planning leadership programmes to meet the needs clinical educators is necessary for nurse, midwife and AHP leaders to respond to the challenges presented to them within the current workforce (Cummings et al., 2021; Kline, 2019; Sholl et al., 2017). Participants' accounts of their experiences on this newly develop programme affirmed how time away from clinical work helped them to gain clarity in respect to ‘the self’, and the impact of ‘the self’ on others. All participants described how having time and space to think was valuable for developing leadership skills and thinking more broadly about who they are as leader and how they can influence others. The benefits of having ‘time and space to think’ in the current study is supported in contemporary leadership development literature (Coventry et al., 2015; Nash & Garratt, 2021). This reflects the need for continued investment in protecting time for HCPs to focus on developing as leaders.

Participants identified how the FNF programme had provided a community where clinicians from various backgrounds were able to exchange knowledge and share ideas outside their own specialist area. This was reported to have increased confidence in leadership capability. Participants also indicated that the programme had been advantageous for developing a robust national network of health care leaders, which could support their career development. This was felt to have stimulated self‐belief in participants' capacity to become successful health care leaders. Previous studies have noted that building and maintaining relationships have perceived importance for developing effective leadership (Hargett et al., 2017). While difficult to establish form a single study, the national network of established contacts, available to participants via the FNF programme, may be a contributory factor in the perceived effect on self‐confidence and career action.

Critical self‐reflection is thought to be a significant factor in facilitating transitions for health care students and promoting higher‐order thinking (Brockbank & McGill, 2007; Gardner et al., 2006). In the current study, participants reported how the opportunity to reflect on their leadership style by developing openness to new perspectives meant that they were able to challenge exiting presuppositions and change established patterns of thinking (Mezirow, 2000). The distinct approach to leadership development described here may be crucial for changing existing cultures within health care teams more broadly and providing health care students with better learning experiences, consequently, helping to improve retention within the workforce in the longer term.

Participants reported increased openness to hearing the perspectives of others. They also recognized that developing relationships was an important element of authentic leadership and necessary for gaining the support for their QI projects and implementing change. Communication skills have been widely reported in previous studies as essential for health care leaders, particularly for creating organisational resilience and staff retention (see Sihvola et al., 2022). Arguably, in order to maintain these skills and to realize the positive effects of the FNF programme, the reflective processes noted by participants in the current study must involve a continual internal dialogue that is both honest and ongoing (Nesbit, 2012). A strong sense of ‘self’ has been noted (Gardner et al., 2005) as a crucial leadership attribute. However, this may be difficult to sustain when time is insufficient, that is, within dynamic and challenging clinical environments (Bakker et al., 2019). As such, it may not be possible for all of the reflective insights gained during the FNF leadership development programme to be acted upon. Moreover, it is difficult to know whether learning will be effectively transferred back to workplaces (Enos et al., 2003).

While programmes such as ours provide a stimulus for a concentrated effort to improve leadership skills, there is a need for knowledge and skills to be continuously updated. Contemporary leadership theorists argue that learning that occurs external to an individual's formal institution lacks understandings that are gained naturally within leaders' workplace environment through the act of conscious and intentional engagement within the workplace context (Marsick & Watkins, 1990). The format provided and positive outcomes reported by programmes external to organisations may not be as straightforward to transfer to the various NHS contexts, or indeed to reproduce internally in the future. However, participants in the current study valued time away from their everyday working environment, to appraise the repertoire of skills required for leadership within the wider context (e.g., the sub‐theme ‘communication skills’ highlighted reflection on interactions for improving health care teams more broadly). These in‐depth reflections illustrate the significance of investing in programmes that can produce effective and ethical (see Mango, 2018) future health care leaders.

5.1. Limitations of the study

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the long‐term effect(s) of the programme regarding participants' ability to sustain their influence as leaders within the learning environment cannot be fully determined from a single study. Second, we recognize that our sample was small (n = 8), which limits the extrapolation of data to a larger group. Third, our study participants were all female, which means that the results/experiences conveyed here may not translate in the same way to participants' male counterparts. Fourth, the length of participants' work experience in the NHS may also be a limiting factor to consider. Lastly, our sample is nonhomogeneous, it is therefore worth repeating this study with a sample of all nurses and the results compared. Having said this, our sample is ecologically valid since it better represents the real working‐world context of individuals employed within the UK NHS (i.e., multidisciplinary teams). Regardless of these limitations, we have obtained in‐depth data, which indicated that perceived changes in self‐confidence were believed to have been facilitated through the unique facets of the FNF programme. For example, participants referred to the collaborative aspect, action learning sets and developing presence as impactful in their self‐reported growth in confidence. It may be beneficial for future studies to evaluate this type of programme using validated measures that can accurately demonstrate changes in self‐confidence and further research is required to evaluate the longer‐term impact of the FNF programme. Finally, participants were from a single geographical area (Southeast England), therefore, the results presented here cannot be assumed to be representative of the population as a whole. However, our results provide unique insight into the impact of providing leadership development where nurses, midwives and allied HCPs work through the challenges involved in implementing change together.Such insights can inform future studies and programmes of a similar structure.

6. CONCLUSION

The qualitative analysis presented in this paper indicates that participants experienced significant shifts in thinking about leadership, personal development and career action as a result of their unique leadership journey. These data show the impact of the FNF leadership development programme and the potential for this type of programme to support individuals and organisations to implement change and potentially make improvements to the learning environment. Further study is required to strengthen the literature in terms of this approach and regarding the distinct impact the programme had on participants. This will help health care leaders and organisations to make strategic and informed choices regarding investment in leadership development and steer personnel to programmes that can evidence the production of distinct outcomes in terms of developing future nurse, midwife and AHP leaders.

6.1. Implications for nursing management

It is important to continue to build nursing and midwifery leadership (and AHP) capacity and capability through programmes, which can help position emerging health care leaders to realize their potential. Unlike medical doctors, nurse and midwives have very few opportunities to develop leadership skills. The nurses, midwives and AHPs interviewed in this study demonstrated passion and ambition for positively impacting outcomes for patients, and wider society. Health care managers should consider supporting clinicians to undertake the type of leadership programme described here, which, through the Florence Nightingale Foundation's national and strategic connections, may help emerging health care leaders to realize their ambitions and make further valuable contributions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

David Hearn is Workforce Education Transformation System Lead, Health Education England Southeast. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The University of Nottingham research ethics committee granted approval (FMHS 218‐0321).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to sincerely thank those who participated in this study whose insights have made this work possible. We would like to thank Health Education England for providing financial support for this research project. The lead author is grateful to Professor Stephen Timmons at the University of Nottingham for his review of the study protocol.

Bond, C. , Stacey, G. , Charles, A. , Westwood, G. , & Hearn, D. (2022). In Nightingale's footsteps: A qualitative analysis of the impact of leadership development within the clinical learning environment. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(7), 2715–2723. 10.1111/jonm.13732

Funding information Health Education England (HEE) funded this research. The funders were not involved in the conceptualization or conduction of this research. CB and AC are both supported by an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) doctoral studentship at the University of Nottingham—grant number ES/P000711/1.

ENDNOTES

Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

Health Education England

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- Arkan, B. , Ordin, Y. , & Yılmaz, D. (2018). Undergraduate nursing students' experience related to their clinical learning environment and factors affecting to their clinical learning process. Nurse Education in Practice, 29, 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, E. J. , Verhaegh, K. J. , Kox, J. H. , van der Beek, A. J. , Boot, C. R. , Roelofs, P. D. , & Francke, A. L. (2019). Late dropout from nursing education: An interview study of nursing students' experiences and reasons. Nurse Education in Practice, 39, 17–25. 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. , & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational Leadership (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beech, J , Bottery, S , Charlesworth, A , Evans, H , Gershlick, B , Hemmings, N , Imison, C , Kahtan, P , McKenna, H , Murray, R , & Palmer, B. (2019). Closing the gap: key areas for action on the health and care workforce. London: The Health Foundation, The King's Fund, Nuffield Trust. Online: www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/closing-the-gap-full-report2019.pdf

- Brockbank, A. , & McGill, I. (2007). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education (2nd ed.). SRHE/Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cant, R. , Ryan, C. , & Cooper, S. (2021). Nursing students' evaluation of clinical practice placements using the clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale–A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 104, 104983. 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton, C. (2019). Florence Nightingale, Nursing, and Healthcare Today, by Lynn McDonald. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry, T. H. , Maslin‐Prothero, S. E. , & Smith, G. (2015). Organizational impact of nurse supply and workload on nurses continuing professional development opportunities: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(12), 2715–2727. 10.1111/jan.12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, G. G. , Lee, S. , Tate, K. , Penconek, T. , Micaroni, S. P. M. , Paananen, T. , & Chatterjee, G. E. (2021). The essentials of nursing leadership: A systematic review of factors and educational interventions influencing nursing leadership. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 115, 103842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria, I. M. , Patterson, B. J. , & Krouse, A. (2017). Predictors of transformational leadership of nurse managers. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(3), 167–175. 10.4324/9781410617095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enos, M. D. , Kehrhahn, M. T. , & Bell, A. (2003). Informal learning and the transfer of learning: How managers develop proficiency. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 14(4), 369–387. 10.1002/hrdq.1074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, F. , Fook, J. , & White, S. (2006). Developing effectiveness in conditions of uncertainty. In White S., Fook J., & Gardner F. (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W. L. , Avolio, B. J. , Luthans, F. , May, D. R. , & Walumbwa, F. (2005). Can you see the real me? A self‐based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 343–372. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, S. E. , MacLeod, M. L. , & Schiller, C. J. (2018). ‘It's complicated’: Staff nurse perceptions of their influence on nursing students' learning. A qualitative descriptive study. Nurse Education Today, 63, 76–80. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargett, C. W. , Doty, J. P. , Hauck, J. N. , Webb, A. M. , Cook, S. H. , Tsipis, N. E. , Neumann, J. A. , Andolsek, K. M. , & Taylor, D. C. (2017). Developing a model for effective leadership in healthcare: A concept mapping approach. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 9, 69–78. 10.2147/JHL.S141664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Foundation, The Kings Fund, Nuffield Trust . (2018). The health care workforce in England: Make or break? London: Health Foundation, The Kings Fund, Nuffield Trust. Online: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/healthcare-workforce-england

- Kalyani, M. N. , Jamshidi, N. , Molazem, Z. , Torabizadeh, C. , & Sharif, F. (2019). How do nursing students experience the clinical learning environment and respond to their experiences? A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 9(7), e028052. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. (2019). Leadership in the NHS. BMJ Leader, Published Online [1st September 2019], 3(4), 129–132. 10.1136/leader-2019-000159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J. (2021). Influence of nurse managers' toxic leadership behaviours on nurse‐reported adverse events and quality of care. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(4), 855–863. 10.1111/jonm.13228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, C. , ODriscoll, M. , & Smith, P. (2007). New roles to support practice learning–can they facilitate expansion of placement capacity? Nurse Education Today, 27(6), 643–650. 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mango, E. (2018). Rethinking leadership theories. Open Journal of Leadership, 7(01), 57–88. 10.4236/ojl.2018.71005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V. J. , & Watkins, K. E. (1990). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. Routledge. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in Progress. The Jossey‐Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey‐Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, K. , & Garratt, A. (2021). Quality improvement in action. British Journal of Midwifery, 29(10), 546–548. 10.12968/bjom.2021.29.10.546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office . (2020). The NHS nursing workforce. HC 109 (session 2019–2021). Online: www.nao.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/The-NHS-nursing-workforce-Summary.pdf

- Neergaard, M. A. , Olesen, F. , Andersen, R. S. , & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description–The poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 1–5. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit, P. L. (2012). The role of self‐reflection, emotional management of feedback, and self‐regulation processes in self‐directed leadership development. Human Resource Development Review, 11(2), 203–226. 10.1177/1534484312439196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council . (2020). Leavers survey 2019: Why do people leave the NMC register? London: Nursing and Midwifery Council. Online: www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-register/march-2020/nmcleavers-survey-2019.pdf

- Panda, S. , Dash, M. , John, J. , Rath, K. , Debata, A. , Swain, D. , Mohanty, K. , & Eustace‐Cook, J. (2021). Challenges faced by student nurses and midwives in clinical learning environment–a systematic review and META‐synthesis. Nurse Education Today, 101, 104875. 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton, M. , Kuper, A. , Paradis, E. , Feilchenfeld, Z. , & Whitehead, C. R. (2021). Tackling the void: The importance of addressing absences in the field of health professions education research. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26(1), 5–18. 10.1007/s10459-020-09966-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafati, F. , Rafati, S. , & Khoshnood, Z. (2020). Perceived stress among Iranian nursing students in a clinical learning environment: A cross‐sectional study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 485–491. 10.2147/AMEP.S259557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, E. S. (2018). Leading change. Leading and Managing in Nursing‐E‐Book, 320.

- Sholl, S. , Ajjawi, R. , Allbutt, H. , Butler, J. , Jindal‐Snape, D. , Morrison, J. , & Rees, C. (2017). Balancing health care education and patient care in the UK workplace: A realist synthesis. Medical Education, 51(8), 787–801. 10.1111/medu.13290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvola, S. , Kvist, T. , & Nurmeksela, A. (2022). Nurse leaders resilience and their role in supporting nurses resilience during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management, 1–12. 10.1111/jonm.13640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diggele, C. , Burgess, A. , Roberts, C. , & Mellis, C. (2020). Leadership in healthcare education. BMC Medical Education, 20(2), 1–6. 10.1186/s12909-020-02288-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.