Abstract

Aim(s)

This study aims to map the extent of the research activity in the field of financial competencies and nursing and identify main patterns, advances, gaps, and evidence produced to date.

Background

Financial competencies are important indicators of professionalism and may influence the quality of care in nursing; moreover, these competencies are the basis of health care sustainability. Despite their relevance, studies available on financial competencies in the nursing field have not been mapped to date.

Evaluation

A scoping review was guided according to (a) the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Review and (b) the Patterns, Advances, Gaps and Evidence for practice and Research recommendations framework.

Key issue(s)

A total of 21 studies were included. Main research patterns have been developing/evaluating the effectiveness of education programmes and investigating the nurse's role in the context of financial management, challenges and needs perceived by them, and tool validation to assess these competencies. The most frequently used concept across studies was ‘financial management competencies’ (n = 19).

Conclusion(s)

The sparse production of studies across countries suggests that there is a need to invest in this research field.

Implications for nursing management

Nurses with managerial roles should invest in their financial competencies by requiring formal training both at the academic and at the continuing education levels. They should also promote educational initiatives for clinical nurses, to increase their capacity to contribute, understand, and manage the emerging financial issues.

Keywords: financial behaviours, financial knowledge, financial liability, financial literacy, financial management, nursing

1. INTRODUCTION

The increased sustainability concerns, productivity expectations and economic pressure applied to the entire health care sector regardless of whether based on tax, social insurance or market (Erjavec & Starc, 2017) and consequently, on the whole nursing system, have been underlined as being at the merit of specific actions by 2020 (Scoble & Russell, 2003). From their side, clinical nurses undertake several decisions daily, and these may have different cost‐effective impact. Moreover, they are immersed in a clinical environment that may value or not the financial implications of each activity, such as supporting nurses in time management and prioritization, in promoting the quality of care to prevent negative outcomes (e.g., increased length of stay) and in coaching how to decide between interventions (e.g., surfaces preventing pressure sores) implying different costs. Moreover, the budget pressure applied by local, regional and national rules may shape the nurse's behaviour and the entire work environment: Examples of how this pressure may exasperate the nursing care at the bedside have been summarized in several documents reporting the detrimental effects of workforce cuts (Alameddine et al., 2012) and that of work environments dominated by the so called command‐and‐control behaviours (Lynas, 2015).

In this scenario, nurse managers have been recognized as playing an important role and are in need of enlarging their responsibilities from those regarding the care quality and staffing to those associated also with financial competencies (Courtney et al., 2002). Nursing care has been reported as consuming approximately one third of the hospital budget (Bai et al., 2017), and head nurses in charge of the units are expected to control labour costs, to contribute to cost saving and ultimately, to the financial stability of the system (Manss, 1993). Given that nurse managers may function as a role model, shaping staff attitudes and behaviours and, ultimately, the care environment, they have been called to be prepared on financial competencies (Hadji, 2015; McFarlan, 2015).

At the beginning of the 90s, Chase (1994) developed the Nurse Manager Competencies Model including financial management skills. In this context, financial management competencies were defined as those regarding the implementation of financial control systems, the collection of financial data, the analysis of financial reports and the following financial decision‐making based on the analyses conducted (Chase, 1994). More recently, Pihlainen et al. (2016) have identified three main competencies of nurse managers, namely, context‐related, operational and general including also financial competencies. The debate regarding the core competencies of nurse managers has continued recently (e.g., Gunawan & Aungsuroch, 2017; Ma et al., 2020) up to the most recent scoping review, where González‐García et al. (2021) have identified 22 competencies as being the most documented in the literature, including financing. However, despite financial competencies having been discussed as relevant more than 100 years ago (The Hospital, 1920), achieving full recognition as a core competence among nurse managers (González‐García et al., 2021) and an educational content to introduce in undergraduate programmes (Lim & Noh, 2015), studies available have never been mapped to date. Mapping the extent of the research on financial competencies in the nursing field, identifying the main patterns, the advances achieved and the gaps still present, may inform future policy, managerial, educational and research directions. Therefore, the intent of this study was to contribute to advance the knowledge available by mapping studies regarding financial competencies published to date in the nursing field.

2. METHODS

2.1. Aim

The specific aim of the study was to summarize (1) the main characteristics of studies on financial competencies published in the nursing field to date, (2) the main issues investigated, (3) the advances produced in terms of knowledge and (4) the gaps still present in this research field.

2.2. Design

A scoping review was performed following two guidelines, namely

-

(1)

the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA‐ScR) guidance (Tricco et al., 2018, Table S1), and

-

(2)

the (a) Patterns, (b) Advances, (c) Gaps and (d) Evidence for practice and research recommendations framework (PAGER guidance, Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2021).

2.3. Search methods

The electronic databases, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL‐EBSCO), SCOPUS and ProQuest (Health and Medical Complete) were approached in October 2021 and then refreshed on the 6th and 7th January 2022. In the initial approach of the database, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were searched (e.g., financial management), and additional terms emerged as more common in the nursing field (e.g., ‘financial competence’; González‐García et al., 2021). Therefore, all MeSH/key words close to that of financial competencies were used in order to broaden the search. Specifically, the following terms ‘financial literacy’, ‘financial management’, ‘financial liability’, ‘financial knowledge’, ‘financial capability’, ‘financial behaviour’, ‘financial education’, ‘financial competency’, ‘nurs*’, ‘nurse’, ‘nursing student’, ‘nurse educator’, ‘nurse teacher’, ‘nurse manager’, ‘nurse leader’, ‘nurse researcher’ were used by two researchers (AB and AP) (Tables S2 and S3).

According to the population, concept and context (PCC) framework (Peters et al., 2020), there were eligible studies concerning:

-

(1)

the nursing system (e.g., nurses, nursing student and nurse manager/leaders) (Population),

-

(2)

the financial competencies topic or related terms (e.g., literacy/knowledge) as investigated with primary and secondary studies (Blaney & Hobson, 1988) (Concept),

-

(3)

all settings (e.g., hospitals and universities) (Context), and written in English, Italian, Slovenian and Czech according to the languages of the research team.

Then, the reference lists of included studies were screened to increase the inclusiveness of the search, and those eligible were included (e.g., Sharma et al., 2021).

2.4. Study selection process

All studies searched were transferred to a reference manager (Mendeley). The duplicated studies were removed by the reference manager programme and visual inspection. After removing the duplicates, the study selection process consisted of two stages. In the first step, two reviewers (AB and AP) screened independently titles, abstracts and keywords of the eligible studies against the inclusion criteria. In the second step, the full text of the studies chosen in the first stage was screened by two reviewers (AB and AP) to extract data. In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were manually searched. In case of disagreement at each stage, a researcher was involved for further discussion until consensus was reached (AnP and BB). Taking into consideration the international panel of researchers, online meetings were conducted to discuss the scoping review protocol and the study selection process.

2.5. Data extraction

Data extraction of the eligible studies was performed independently by two reviewers (AB and AP). The data extraction grid was piloted in one study, and the final version was approved by the entire research team as composed by the following elements: (a) author(s), year, country of origin and field of authors (e.g., economics, nursing); (b) study aim(s), design, setting(s) and year of data collection; (c) sampling method and participants' main characteristics; (d) data collection process and tools; (e) concepts/terminologies used in the study (e.g., financial competence, literacy); (f) interventions applied, if applicable (e.g., education); and (g) main findings related to the research question(s). Data extraction was performed by researchers (AB and AP), and other researchers (AnP and BB) were consulted in case of disagreements.

2.6. Data synthesis

First, the included studies have been summarized in their main features. Then, according to the Patterns, Advances, Gaps and Evidence (PAGER) framework (Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2021), the patterns of this current body of literature have been described regarding (a) studies characteristic, (b) the main areas investigated, (c) the profiles of participants involved and (d) the underlying financial concepts used by authors to also detect in this case, the main patterns. Thus, according to the PAGER framework (Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2021), the main advances in the evidence were identified by summarizing the findings produced in this research field over the years. Then, gaps in the research were identified, and implications for nurse managers of the evidence emerged were summarized.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

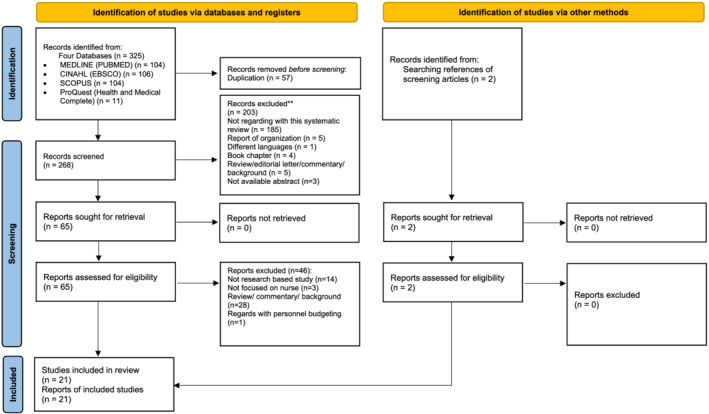

As reported in Figure 1, a total of 21 studies were included. These were published between 1987 (Johnson, 1987) and 2021 (Paarima et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021), mostly in the United States (n = 13) and the remainder in different continents (Africa, Naranjee et al., 2019; Asia, Bai et al., 2017; Australia, Courtney et al., 2002; and Europe, e.g., Slovenia & Ghana; Paarima et al., 2021). In the majority (n = 14), the first author was appointed at university level (e.g., Scalzi & Wilson, 1991), whereas the remaining were in health care facilities (e.g., Johnson, 1987) (Table S4).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. Source: Page et al. (2021) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Six studies were cross‐sectional or descriptive (e.g., Carruth et al., 2000), four mixed both qualitative and quantitative approaches (e.g., Ruland & Ravn, 2003), three were pre/post or quasi‐experimental study designs (e.g., Krugman et al., 2002), whereas two were qualitative (e.g., Naranjee et al., 2019). The remaining six did not specify the design (e.g., Davis, 2005). Multiple research phases were performed by three studies involving different participants, such as that conducted by Erjavec and Starc (2017) (first phase 297 nurse managers and second phase 12), by Lim and Noh (2015) (11 nurses and 12 experts) and by Brydges et al. (2019) (178 and 10 nurse executive leaders).

Studies were mainly multicentre in nature (n = 12, e.g., Bai et al., 2017), and only a few have involved community hospitals (McFarlan, 2020; Paarima et al., 2021), nursing homes (Johnson, 1987), districts (Sharma et al., 2021) and public health care services (Courtney et al., 2002).

A convenience (n = 6, e.g., Blaney & Hobson, 1988) followed by a random (n = 5, e.g., Poteet et al., 1991), a purposeful (n = 3, Bai et al., 2017; Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Naranjee et al., 2019) and a mixed‐sampling method (n = 3, e.g., convenience and purposeful; Brydges et al., 2019) were used, whereas one reached all the target population (Paarima et al., 2021). However, some studies did not report the sampling used (n = 3, e.g., Scalzi & Wilson, 1991). At the overall level, 7 (Ruland & Ravn, 2003) to 370 participants (LaFevers et al., 2015) were involved, and 10 studies out of 21 involved less than 55 participants.

When reported, participants were all (Blaney & Hobson, 1988; McFarlan, 2020; Scalzi & Wilson, 1991) or the majority female (Carruth et al., 2000; Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Paarima et al., 2021); their average age was from 38.4 (Blaney & Hobson, 1988) to 49 years (Poteet et al., 1991; Scalzi & Wilson, 1991), and the average experiences in management ranged from >2 or 3 (Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Lim & Noh, 2015) to 10 years (Scalzi & Wilson, 1991) up to 30 (Erjavec & Starc, 2017). In a few studies, the educational background of participants was described, ranging from diploma (51.9%, Scalzi & Wilson, 1991), to bachelor and masters (Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Paarima et al., 2021) and first‐degree holders (47.9%, Paarima et al., 2021); in only one study, some participants were reported to be educated at the doctorate level (e.g., 4 out of 226; McFarlan, 2020).

Outcomes have been assessed in seven studies with validated tools, namely, (a) the Financial Management Competency Self‐Assessment (FMCA) and the Financial Knowledge Assessment (FKA) on the financial literacy of nurse leaders (Brydges et al., 2019); (b) the Budget‐related Behaviour scale on budget preparation, planning and control (Carruth et al., 2000); (c) the Health Service Managers Role and Careers (Courtney et al., 2002); (d) the Quality Review Checklist on students' opinions about technical and instructional quality of the modules (Edwardson & Pejsa, 1993); (e) the Chase's Nurse Manager Competency Instrument (Erjavec & Starc, 2017); (f) the Nurse Manager Skills Inventory Tool (McFarlan, 2020); and (g) the Nurse Managers Competencies Instrument (NMCI) (Paarima et al., 2021). However, ad hoc questionnaires (n = 4, e.g., Johnson, 1987) and surveys (n = 5, e.g., LaFevers et al., 2015) were also used.

In qualitative studies, data were collected with in‐depth semi‐structured individual interviews (n = 4, e.g., Bai et al., 2017) and focus groups (Lim & Noh, 2015; Ruland & Ravn, 2003). Two studies did not report data collection tools clearly (Consolvo & Peters, 1991; Davis, 2005), and only one has collected data from staffing and financial statistics to assess improvements in the balance stability (Ruland & Ravn, 2003).

In addition, in a few studies, the time when the data collection was performed has been reported (n = 6, e.g., Sharma et al., 2021; Paarima et al., 2021).

3.2. Patterns

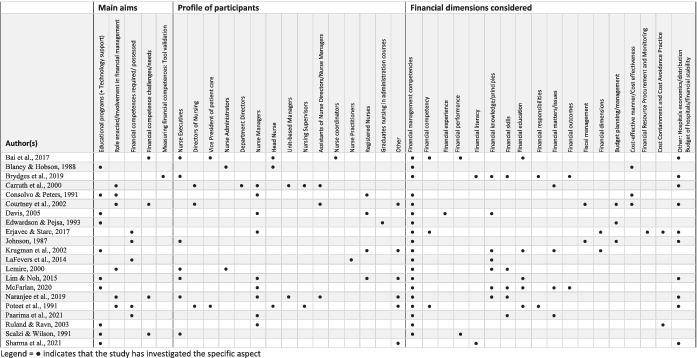

As reported in Table 1, developing educational programmes or evaluating their effectiveness by also including technologies (n = 10, e.g., Sharma et al., 2021) was the most frequent aim of the studies retrieved; to a lesser extent, the role as enacted by nurses in the context of financial management (n = 6, e.g., Carruth et al., 2000), the financial competencies/knowledge possessed (n = 5, e.g., Paarima et al., 2021), the challenges/needs perceived regarding the financial issues (n = 4, e.g., Bai et al., 2017) and the tool validation to assess such competencies was investigated (n = 1, Brydges et al., 2019).

TABLE 1.

Studies patterns: Main aims, participants profiles and financial dimensions considered in studies (=21)

|

Studies involved different participants, from nurse executives (n = 7 e.g., Scalzi & Wilson, 1991) to nurse managers (n = 9, e.g., Carruth et al., 2000; Paarima et al., 2021), and registered nurses (n = 4, e.g., Davis, 2005). Moreover, studies involved homogeneous profiles (n = 10, Blaney & Hobson, 1988) such as nurse managers/leaders (e.g., Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Paarima et al., 2021), executives (Brydges et al., 2019), graduate students (Edwardson & Pejsa, 1993) or nurse practitioners (LaFevers et al., 2015). The remaining 11 studies involved from two (e.g., Blaney & Hobson, 1988) to six different professional roles (e.g., Carruth et al., 2000).

‘Financial management competencies’ was the most often used concept by researchers (=19 studies) with the exception of two (Carruth et al., 2000; Sharma et al., 2021) followed by that of ‘financial knowledge/principles’ (n = 7, e.g., McFarlan, 2020) and ‘financial/finance education’ (n = 5, e.g., Poteet et al., 1991). Less used were the ‘financial literacy’ (n = 2, Brydges et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021) and ‘financial experience’ (Davis, 2005) concepts.

3.3. Advances in the evidence

The financial role has been investigated in the studies in their main features and across the managerial profiles occupied. Carruth et al. (2000) reported that nurse managers were used to plan, investigate budget variances, prepare future budgets and suggest budget changes activities. Moreover, in their study, less than 25% of nurse managers controlled the budget as compared with less than 18% unit‐based coordinators, supervisors and assistants (Carruth et al., 2000). The financial role has also been documented by Naranjee et al. (2019) (nurse managers = planning; monitoring; decision‐making; controlling), Poteet et al. (1991) (nurse executives = preparing budget; allocating the budget), Courtney et al. (2002) (nurse executives = financial management) and by Lemire (2000) where budget preparation and productivity were both recognized as important and profit analysis rated at higher importance among chief executive officers than nurse administrators.

Despite their recognized role, nurses have been documented to perceive moderate competencies (Paarima et al., 2021) or to be unready to manage the budget (LaFevers et al., 2015) due to the lack of formal education, whereas the competencies are developed mainly on the job and with self‐study. Therefore, financial competencies should be included in the nursing administration curriculum at the masters/doctoral levels and at the bachelor/diploma levels (Johnson, 1987). However, the role occupied, and the working places are both important in influencing the competencies perceived: In Erjavec and Starc (2017), the nurse managers working in private sectors reported significantly higher financial management competencies compared with those working in the public sector. In contrast, nurse managers in high positions reported significantly higher levels of financial management competencies than those in lower positions.

The financial management role occupied has been considered as the basis for the development of a financial competency framework (Naranjee et al., 2019) and specific educational programmes (Scalzi & Wilson, 1991) to support leaders in overcoming the challenges lived in financial and budget management. Specifically, financial and budget management have been perceived as the most difficult tasks due to budget constraints, financial inequities and the increased demands on resources (Courtney et al., 2002). Additional challenges have been documented in the lack of intrinsic motivation and education on financial issues, in the poor cooperation and communication across units and in the insufficient reference managerial tools (Bai et al., 2017).

All studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of education programmes reported their positive effects on motivation and self‐perceived skills to work in a cost‐effective manner (Blaney & Hobson, 1988; Ruland & Ravn, 2003) on financial management knowledge (Davis, 2005; Krugman et al., 2002; McFarlan, 2020), on literacy (Sharma et al., 2021), on roles (McFarlan, 2020) and on nurse manager perceptions (Consolvo & Peters, 1991). Moreover, educational programmes including computer‐aided instruction have been appreciated in addressing financial management issues (Edwardson & Pejsa, 1993) and in reducing expenditures for overtime and extra hours meeting the budget balance in a year (Ruland & Ravn, 2003). Educational programmes may be generated according to the role occupied in a bottom‐up approach (Scalzi & Wilson, 1991) or by mixing the bottom‐up and the top‐down approach (Lim & Noh, 2015). However, only Brydges et al. (2019) validated a tool measuring the financial management competencies among nurse executives, capable also of discerning the level of such competencies across novices, competent and expert executives.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Study characteristics and gaps

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review on financial competencies in the nursing field. With the growing attention on health care costs, sustainability, productivity, performance and, in some countries, on competitiveness (Hampton, 2017; Talley et al., 2013), mapping the research's state might support the identification and the address of gaps in study methodologies and in investigated areas.

Despite the recognized relevance of the financial issues in the health care (Erjavec & Starc, 2017; Scoble & Russell, 2003) and also in the nursing sector (Bai et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2017), only a few studies have been published to date in this field, less than one per year in the last 25 years. The limited power given to nurses (McMillan & Perron, 2020) and the influence of some stereotypes regarding their higher interpersonal skills when compared with doctors, who are perceived as having high power and being strong leaders (Braithwaite et al., 2016), might have left this area of investigation out of the nursing discipline.

Most of the studies have been conducted in the United States, and the diverse nature of the roles played by nurses, as well as the financial features of the health care systems where they are immersed (Waxman & Massarweh, 2018), suggest that evidence produced in this field should be considered generalizable with caution given that it is context‐related. In this regard, more attention should be given in future studies to describing context‐specific issues (Luz et al., 2018) that may affect the interpretation and the generalization of the findings. Describing the health care financial and reimbursement systems, the private or public mission, the role enacted by nurses and their responsibilities are only some examples of contextual data that should be reported in future studies.

From the methodological point of view, studies have been conducted by researchers appointed at the academic and at the health care facility levels, suggesting a mix of interests in this research area, from both professional/managerial and academic perspectives, and a potential source of academia/service partnership also including non‐nursing disciplines.

Emerged studies have been mainly multicentric in nature, more often involving hospitals, suggesting the need to also involve community/home, intermediate and residential settings in line with the progressive decentralization of care according to its cost‐effectiveness (Blackburn et al., 2016). Although a wide variety of study designs have been performed to date, some of them have not been fully specified in their methods, confirming the need to increase the methodological accuracy of this research field. Furthermore, studies have included a limited number of participants, with some gender (=all female) and age (mature professionals) biases that should be addressed in the future by also ensuring greater attention is paid to describing participants' characteristics, given that missing data may threaten the external validity of the findings. For example, describing the educational prerequisites possessed (e.g., bachelor/master), as well as how the financial responsibilities are given, through a progressive career promotion in the field or after being trained and assessed in these competencies, might help in the interpretation of the findings.

Studies have mainly investigated the perceptions of nurses as rated with self‐administrated questionnaires or through individual/in group interviews. Only one study has used objective data (e.g., performance data, Ruland & Ravn, 2003). This research field is encouraged to use more objective measures in the future—close to the definition of the financial discipline itself, which is aimed at measuring behaviour and consequences with objective data (OECD, 2013, p. 80). Moreover, while measuring the perceptions, more homogeneity in the metrics and tools used to detect outcomes is encouraged to increase the likelihood of comparing the findings and to accumulate the evidence.

4.2. Patterns and gaps

First, patterns that emerged are all around financial competencies from those required or needed to those perceived as important or challenging and from those possessed or acquired with tailored educational programmes to tools capable of measuring such competencies. Therefore, financial competencies as perceived by nurses are central in this research field: In other words, the focus is given to the nurses' professional development, by identifying the theory and the practice gap, the competencies expected and the associated learning needs (Tashiro et al., 2013), mainly as an internal examination exercise. Moving this research line forward by embracing other disciplines and perspectives is strongly suggested to communicate outside of the nursing field the financial competency achievements that might increase the nurse's power and overcome any stigma (Braithwaite et al., 2016).

Second, regarding the profiles involved, these competencies have been investigated mainly among nurses with managerial roles, and only to a limited extent among clinical nurses (e.g., Davis, 2005). Clinical nurses are important partners in cost‐related initiatives and excluding them might marginalize the entire profession from an issue that is central for the quality of care. Moreover, increasing the gap between the nurse managers in their different roles—by equipping them with appropriate education—and the clinical nurses may also trigger conflicts and professional distance between those who are in charge of the operational decisions regarding the nursing care and those responsible for delivering the care (LaFevers et al., 2015). Furthermore, the low financial competencies of clinical nurses may prevent their full independence in making decisions. One possible reason is that the clinical nurse is not considered as a carrier measurable in the performance, given that it is not reimbursed in terms of specific interventions, but rather as a complex of lump‐sum activities. Moreover, it may also be possible that a prejudice is still present regarding the current reimbursement for care being focused on saving money in terms of direct costs but does not account for indirect costs (e.g., in the care of patients with non‐healing wounds, falls). The education process is also a significant factor: Current nurse educators may lack in financial competencies, and this may prevent the knowledge transfer and promotion to students. Therefore, considering the financial competencies as a continuum, from undergraduate to postgraduate education, embracing all nurses' roles, may increase the mutual understanding and the power of the nursing profession (Di Giulio et al., 2020).

Third, although the concept of ‘financial management competencies’ seems to be considered central in this kind of research, all studies also used other subconcepts (e.g., financial literacy and financial skills): however, more conceptual clarity is required to expand the theoretical foundation of this field of research, a gap that should be urgently addressed.

4.3. Advances in evidence and gaps

Different financial competencies and financial competence frameworks have been identified to date (e.g., Naranjee et al., 2019) mainly involving nurses. Establishing the set of competencies required is crucial to develop educational programmes; however, there is a need to develop a comprehensive framework of such competencies, from clinical to managerial roles, by also involving non‐nurse stakeholders as for example those occupying executive financial roles to deepen their expectations, making visible the continuum of the expected competencies and designing effective undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education strategies. Moreover, a stratification of financial competencies has been identified across novices, experts and competent levels in the same role (Brydges et al., 2019) and across roles (Erjavec & Starc, 2017). This suggests that it is not only the education provided that might modulate the financial competencies but also other factors (e.g., the communication with the financial managers of the hospitals). Therefore, investigating the role of some intrinsic (e.g., motivation towards financial competencies; Bai et al., 2017) and extrinsic factors (e.g., associated with the context, its mission) in building such competencies is recommended.

Financial competencies are acquired mainly by on‐the‐job study and self‐study (LaFevers et al., 2015): The examples of programmes scrutinized for their effectiveness published to date (e.g., McFarlan, 2020) might be used to design further educational interventions in their methods, duration and main contents. However, given that today the outcomes of these educational interventions have been investigated from the perceptions of the nurses involved, there is a need to also investigate some actual outcomes (e.g., financial behaviour and decisions) by establishing valid indicators. Examples of policies in this field (e.g., Ruatti et al., 2021) as those designed by the American Organization of Nurse Leadership and the Healthcare Financial Management Association (e.g., AONL, 2022) may be useful in designing educational programmes as well as in underlying the relevance of financial theme as a key factor in the health care sustainability. Above all, nurses at different levels might contribute tremendously to the implementation of the value‐based health care that has been defined as the most important current transformation: In this context, care delivery systems must be value for patients where value is the outcome(s) expected for patients and the costs to achieve these outcomes (Porter & Teisberg, 2006). The Future of Nursing Report 2020–2030 has been recommended to use performance‐based payment criteria for the care and interventions performed by nurses within the scope of the value‐based payment system. In this context, nurses can document the necessary financial behaviours and decisions in a concrete way by recording all kinds of initiatives and care indicators they apply. This provides an opportunity to see the financial behaviours of nurses in a concrete way within the framework of the value‐based health care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021).

4.4. Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, although the search of studies has been designed and conducted with care, some studies may have been missed. Moreover, no grey literature has been investigated, such as professional, regulatory or health care reports/policy documents according to the purpose to map the state of the research. In this intent, all studies were considered eligible without imposing any limitation in the time: As a result, the studies included have been published from 1987 to 2021, and the interpretations of their findings should be prudent given that the financial relevance in the health care sector may differ over time.

In accordance with the method described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), the quality appraisal of included studies was not performed. In addition, we have used the PAGER framework (Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2021) to organize the findings and the discussion to focus the attention on gaps—as this is the main intent of scoping reviews. However, this should be considered in its limitation, given the recent establishment of the PAGE framework and limited examples available. Furthermore, the research team identified the main research patterns and gaps: Their background may have influenced the process of study interpretation and patterns/gaps identification.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Research into financial competencies in the nursing profession is in its infancy. The sparse production of studies across countries suggests that there is a need to invest in this research field. From a mainly internal, professional development‐oriented approach, this research field should be integrated into the broader approach by also involving other disciplines. In addition, more methodologically sound studies are required, transitioning from the definition of competencies required to (a) how to effectively develop them and (b) how these competencies can make a difference in financial decisions and outcomes on a daily basis. Moreover, this research field should change its perspective from being mainly reactive to the increased needs and challenges in the health care sector regarding financial issues and sustainability to being more proactive according to the gaps identified.

From the nursing point of view, financial competencies may help the profession to flourish by increasing its chances to participate and implement decisions safeguarding the quality of care effectively. On the other hand, increased financial competencies may reduce the marginalization of nurses and progressively prevent the subordination of their care to the decisions of others. Consequently, from the health care sector point of view, where the financial issues are increasing their pressures, all nurses can contribute proactively, from those who play a clinical role to those with executive roles.

Nursing in the 21st century needs a change in the mindset of nurses, and therefore, financial literacy must be a part of their professional skills. As part of education, a nurse equipped with financial competencies can effectively share information with the patients, which can ultimately help them in decision‐making. For undergraduate students, financial literacy will help in their personal lives (e.g., personal budget management, economic and financial balance of their future life, poverty prevention and debt traps). Financial literacy will also affect nurses' professional lives, as they better understand the functioning of health care institutions in their country. Based on finance competencies, they could participate in improving the quality of care provided, in applying evidence‐based approaches and in establishing effective indicators of quality of nursing care provided.

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

Nurses with managerial roles should invest in their financial competencies by requiring formal training both at the academic and at the continuing education level. Besides, they need to explore the impact of this investment on their individual financial capabilities and consider the financial goals of the health care institutions they are in. In designing the educational opportunities for clinical nurses to promote their continuing professional development, they should also consider financial alphabetization, to increase their capacity to contribute, understand and manage the emerging financial issues. It is also recommended that these financial competencies be debated in terms of advantage for all managerial roles occupied by nurses, and inside of them, across junior to senior positions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

According to the nature of the study, no ethical approval was required.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

AB, AP, AnP and BB made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data. AB, AP and AnP made substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. AB, AP, AnP and BB (drafting) and SL, NB, SS, RW, MP and IK (revising) involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors had given the final approval of the version to be published. Each author have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supporting information

Table S1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018)

Table S2. Records identified through database screening

Table S3. Records identified through different database

Table S4. Data extraction of included studies (n = 21)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are aware that financial literacy has not yet been systematically addressed in education. For this reason, a project BICEPS project (Building financial capability for health care professionals) is being implemented to share experiences and promote the knowledge and skills of students in health care. This work was supported by the BICEPS project (Building financial capability for health care professionals) funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union (2020‐1‐CZ01‐KA203‐078187). Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Udine within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Bayram, A. , Pokorná, A. , Ličen, S. , Beharková, N. , Saibertová, S. , Wilhelmová, R. , Prosen, M. , Karnjus, I. , Buchtová, B. , & Palese, A. (2022). Financial competencies as investigated in the nursing field: Findings of a scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(7), 2801–2810. 10.1111/jonm.13671

[Correction added on 8 June 2022, after first online publication: The job titles for authors Natália Beharková, Simona Saibertová, Radka Wilhelmová, and Barbora Buchtová has been corrected from Full/Associate Professor to Assistant Professor.]

Funding information European Union, Grant/Award Number: 2020‐1‐CZ01‐KA203‐078187

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Alameddine, M. , Baumann, A. , Laporte, A. , & Deber, R. (2012). A narrative review on the effect of economic downturns on the nursing labour market: Implications for policy and planning. Human Resources for Health, 10, 23. 10.1186/1478-4491-10-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL) . (2022). Finance and business skills for nurse managers. Retrieved from https://www.aonl.org/education/nurse-manager-finance

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. , Gu, C. , Chen, Q. , Xiao, J. , Liu, D. , & Tang, S. (2017). The challenges that head nurses confront on financial management today: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 4(2), 122–127. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, J. , Locher, J. L. , & Kilgore, M. L. (2016). Comparison of long‐term care in nursing homes versus home health: Costs and outcomes in Alabama. The Gerontologist, 56(2), 215–221. 10.1093/geront/gnu021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney, D. R. , & Hobson, C. J. (1988). Developing financial management skills: An educational approach. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 18(6), 13–17. 10.1097/00005110-198806010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury‐Jones, C. , Aveyard, H. , Herber, O. R. , Isham, L. , Taylor, J. , & O’Malley, L. (2021). Scoping reviews: the PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1–14. 10.1080/13645579.2021.1899596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J. , Clay‐Williams, R. , Vecellio, E. , Marks, D. , Hooper, T. , Westbrook, M. , Westbrook, J. , Blakely, B. , & Ludlow, K. (2016). The basis of clinical tribalism, hierarchy and stereotyping: A laboratory‐controlled teamwork experiment. British Medical Journal Open, 6(7), e012467. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydges, G. , Krepper, R. , Nibert, A. , Young, A. , & Luquire, R. (2019). Assessing executive nurse leaders financial literacy level: A mixed‐methods study. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(12), 596–603. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruth, A. K. , Carruth, P. J. , & Noto, E. C. (2000). Financial management. Nurse managers flex their budgetary might. Nursing Management, 31(2), 16–17. 10.1097/00006247-200002000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase, L. (1994). Nurse manager competencies. Journal of Nursing Administration, 24(4 Suppl), 56–64. 10.1097/00005110-199404011-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolvo, C. A. , & Peters, M. (1991). Financial management for nurse managers—The bottom line for renewal. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 22(6), 245–247. 10.3928/0022-0124-19911101-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W. A. , Morrison, M. L. , Eaton, L. H. , Theodore, B. R. , & Doorenbos, A. Z. (2017). Quantity and quality of economic evaluations in US nursing research 1997–2015: A systematic review. Nursing Research, 66(1), 28–39. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, M. , Yacopetti, J. , James, C. , Walsh, A. , & Montgomery, M. (2002). Queensland public sector nurse executives: Professional development needs. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(3), 8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E. (2005). Home study program. Educating perioperative managers about materials and financial management. AORN Journal, 81(4), 798–812. 10.1016/S0001-2092(06)60359-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giulio, P. , Palese, A. , Saiani, L. , & Tognoni, G. (2020). Appunti di contenuto‐metodo per immaginare un percorso formativo a misura del futuro [Notes of method to imagine an education tailored to the future]. Assistenza Infermieristica e Ricerca: AIR, 39(1), 31–34. 10.1702/3371.33474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwardson, S. R. , & Pejsa, J. (1993). A computer assisted tutorial for applications of computer spreadsheets in nursing financial management. Computers in Nursing, 11(4), 169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erjavec, K. , & Starc, J. (2017). Competencies of nurse managers in Slovenia: A qualitative and quantitative study. Central European Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 8(2), 632–640. 10.15452/CEJNM.2017.08.0012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González‐García, A. , Pinto‐Carral, A. , Pérez‐González, S. , & Marqués‐Sánchez, P. (2021). Nurse managers' competencies: A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1410–1419. 10.1111/jonm.13380. Epub 2021 Jul 12 PMID: 34018273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J. , & Aungsuroch, Y. (2017). Managerial competence of first‐line nurse managers: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 23(1), e12502. 10.1111/ijn.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadji, D. (2015). Successful transition from staff nurse to nurse manager. Nurse Leader, 13(1), 78–81. 10.1016/j.mnl.2014.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, M. (2017). Maintain optimal staffing with position control. Nursing Management, 48(1), 7–8. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000511190.33666.0b10.1097/01.NUMA.0000511190.33666.0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. S. (1987). Preparing nurse executives for financial management. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 11, 67–73. 10.1097/00006216-198701210-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, M. , MacLauchlan, M. , Riippi, L. , & Grubbs, J. (2002). A multidisciplinary financial education research project. Nursing Economic$, 20(6), 273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFevers, D. , Ward, S. P. , & Wright, W. (2015). Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: An interprofessional perspective. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(4), 181–184. 10.1002/2327-6924.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire, J. A. (2000). Redesigning financial management education for the nursing administration graduate student. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 30(4), 199–205. 10.1097/00005110-200004000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J. Y. , & Noh, W. (2015). Key components of financial‐analysis education for clinical nurses. Nursing & Health Sciences, 17(3), 293–298. 10.1111/nhs.12186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz, A. , Santatiwongchai, B. , Pattanaphesaj, J. , & Teerawattananon, Y. (2018). Identifying priority technical and context‐specific issues in improving the conduct, reporting and use of health economic evaluation in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 4. 10.1186/s12961-018-0280-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynas, K. (2015). The leadership response to the Francis report. Future Hospital Journal, 2(3), 203–208. 10.7861/futurehosp.2-3-203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. , Chihava, T. N. , Fu, J. , Zhang, S. , Lei, L. , Tan, J. , Lin, L. , & Luo, Y. (2020). Competencies of military nurse managers: A scoping review and unifying framework. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(6), 1166–1176. 10.1111/jonm.13068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manss, V. C. (1993). Influencing the rising costs of health care: A staff nurse's perspective. Nursing Economic$, 11(2), 83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlan, S. (2015). Evaluation of an educational intervention to improve nurse managers understanding of and self‐assessed competence with personnel budgeting. Doctor of Nursing Practice Projects, 58. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/dnp_etds/58

- McFarlan, S. (2020). An experiential educational intervention to improve nurse managers knowledge and self‐assessed competence with health care financial management. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 51(4), 181–188. 10.3928/00220124-20200317-08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, K. , & Perron, A. (2020). Nurses engagement with power, voice and politics amidst restructuring efforts. Nursing Inquiry, 27(3), e12345. 10.1111/nin.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjee, N. , Ngxongo, T. S. P. , & Sibiya, M. N. (2019). Financial management roles of nurse managers in selected public hospitals in KwaZulu‐Natal province, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 11(1), a1981. 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . (2021). Paying for equity in health and health care (chapter 6). In Wakefield M., Williams D. R., Le Menestrel S., & Flaubert J. L. (Eds.), The future of nursing 2020–2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity (pp. 147–188). National Academies Press (US). 10.17226/25982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) . (2013). Advancing national strategies for financial education. A joint publication by Russias G20 presidency and the OECD. Page 80. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/finance/financialeducation/G20_OECD_NSFinancialEducation.pdf

- Paarima, Y. , Kwashie, A. A. , & Ofei, A. M. A. (2021). Financial management skills of nurse managers in the Eastern region of Ghana. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 14, 100269. 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J. , Godfrey, C. , McInerney, P. , Munn, Z. , Tricco, A. C. , & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In Aromataris E. & Munn Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. Retrieved from. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global, 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlainen, V. , Kivinen, T. , & Lammintakanen, J. (2016). Management and leadership competence in hospitals: A systematic literature review. Leadership in Health Services, 29, 95–110. 10.1108/LHS-11-2014-0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. , & Teisberg, E. O. (2006). Redefining health care: Creating value‐based competition on results. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poteet, G. W. , Hodges, L. C. , & Goddard, N. (1991). Financial responsibilities and preparation of chief nurse executives. Nursing Economic$, 9(5), 305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruatti, E. , Danielis, M. , & Palese, A. (2021). Il programma Productive Ward per migliorare la qualità delle cure infermieristiche: risultati di una scoping review [The Productive Ward programme to provide high quality care: Findings from a scoping review]. Assistenza Infermieristica e Ricerca: AIR, 40(4), 221–232. 10.1702/3743.37261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland, C. M. , & Ravn, I. H. (2003). Usefulness and effects on costs and staff management of a nursing resource management information system. Journal of Nursing Management (Wiley‐Blackwell), 11(3), 208–215. 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2003.00381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalzi, C. C. , & Wilson, D. L. (1991). Future preparation of home health nurse executives. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 12(1), 13–21. 10.1300/J027v12n01_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoble, K. B. , & Russell, G. (2003). Vision 2020, part I: Profile of the future nurse leader. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(6), 324–330. 10.1097/00005110-200306000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S. , Arora, K. , Sinha, R. K. , Akhtar, F. , & Mehra, S. (2021). Evaluation of a training program for life skills education and financial literacy to community health workers in India: A quasi‐experimental study. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12913-020-06025-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley, L. B. , Thorgrimson, D. H. , & Robinson, N. C. (2013). Financial literacy as an essential element in nursing management practice. Nursing Economic$, 31(2), 77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro, J. , Shimpuku, Y. , Naruse, K. , & Matsutani, M. (2013). Concept analysis of reflection in nursing professional development. Japan Journal of Nursing Science: JJNS, 10(2), 170–179. 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2012.00222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (1920). The economic development of the nursing services. The Hospital, 69(1801), 249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , Moher, D. , Peters, M. D. J. , Horsley, T. , Weeks, L. , Hempel, S. , Akl, E. A. , Chang, C. , McGowan, J. , Stewart, L. , Hartling, L. , Aldcroft, A. , Wilson, M. G. , Garritty, C. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, K. T. , & Massarweh, L. J. (2018). Talking the talk: Financial skills for nurse leaders. Nurse Leader, 16(2), 101–106. 10.1016/j.mnl.2017.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018)

Table S2. Records identified through database screening

Table S3. Records identified through different database

Table S4. Data extraction of included studies (n = 21)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.