Abstract

Aim

Thinking biases are posited to be involved in the genesis and maintenance of delusions. Persecutory delusions are one of the most commonly occurring delusional subtypes and cause substantial distress and disability to the individuals experiencing them. Their clinical relevance confers a rationale for investigating them. Particularly, this review aims to elucidate which cognitive biases are involved in their development and persistence.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Global Health were searched from the year 2000 to June 2020. A formal narrative synthesis was employed to report the findings and a quality assessment of included studies was conducted.

Results

Twenty five studies were included. Overall, 18 thinking biases were identified. Hostility and trustworthiness judgement biases appeared to be specific to persecutory delusions while jumping to conclusions, self‐serving attributional biases and belief inflexibility were proposed to be more closely related to other delusional subtypes. While the majority of the biases identified were suggested to be involved in delusion maintenance, hostility biases, need for closure and personalizing attributional biases were believed to also have aetiological influences.

Conclusions

These findings show that some cognitive biases are specific to paranoid psychosis and appear to be involved in the formation and/or persistence of persecutory delusions.

Keywords: cognitive biases, paranoia, persecutory delusions, psychosis, schizophrenia

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the DSM‐5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), psychosis is a reality distortion experience characterized by delusions and hallucinations, negative symptoms, grossly disorganized or catatonic behaviour, and disorganized thinking and speech.

For the purpose of this review, a focus will be placed on persecutory delusions (PD) and cognitive biases. PD can be conceptualized as erroneous and unfounded “threat beliefs” (Freeman et al., 2002). PD are one of the most commonly occuring delusional subtypes, occuring in half of individuals experiencing psychosis and in more than 70% of first‐episode psychosis (FEP) patients (Coid et al., 2013; Waller et al., 2015). PD are associated with significant risks as they are proposed to be the most likely delusional subtype to be acted upon and to be associated with a risk of serious violence (Coid et al., 2013; Wessely et al., 1993).

According to the cognitive model of PD (Freeman et al., 2002), trigger events cause arousal in individuals, who then experience an inner‐outer confusion, driving the emergence of anomalous experiences. One of the putative routes to anomalous experiences is via the action of cognitive biases associated with psychosis. The latter are also employed in the “search for meaning”, a process during which individuals try to make sense of such experiences. As for delusion maintenance, thinking biases that favour the receipt of confirmatory evidence have been proposed as contributing factors (Freeman et al., 2002). Overall, this framework proposes that cognitive biases represent causal elements in the formation and persistence of PD, conferring a rationale to investigate their role in this delusional subtype. Of note, other cognitive theories have implicated biases in the process of development and maintenance of positive symptoms (Garety et al., 2001).

Cognitive biases can be understood as dysfunctional thinking patterns that lead to incorrect inferences and abnormal perceptions (Gawęda & Prochwicz, 2015). A number of cognitive biases have been associated with delusions and are deemed to be psychosis‐specific. One of the most studied is Jumping To Conclusions (JTC), which refers to the tendency to make decisions on the basis of insufficient information (Moritz & Woodward, 2005). JTC has been found in 40%–70% of patients with delusions (Freeman et al., 2004). Liberal acceptance is another bias associated with delusions, which can be understood as the tendency to endorse information and make decisions prematurely, based on low subjective probability ratings (Moritz et al., 2008; Reininghaus et al., 2019). A related concept to JTC and Liberal acceptance pertains to overconfidence, which is characterized by a tendency for individuals to be overly confident when making erroneous judgements. Indeed, studies have reported that individuals with psychosis, compared to controls, demonstrate higher confidence levels in relation to their erroneous judgements and low‐confidence levels in relation to correct responses (Moritz et al., 2014). Overconfidence has been proposed to arise from a liberal acceptance reasoning style and to be closely linked to JTC (Moritz et al., 2008).

A substantial part of the existing research also focuses on attributional biases. Schizophrenia patients with delusions have been proposed to demonstrate a negative external personal attributional style compared to non‐delusional patients, meaning that they tend to attribute the causality of negative events to other people, rather than to circumstances or to themselves (Aakre et al., 2009). Other psychosis‐specific biases include the Need For Closure (NFC), which refers to the desire to accept any explanatory framework due to an inability to tolerate uncertainty (Kruglanski & Fishman, 2009), and a lack of belief flexibility, intended as the metacognitive ability to think about one's thoughts and to consider alternative explanations (Garety et al., 2005). Additional biases in psychosis include Bias Against Disconfirmatory/Confirmatory Evidence (BADE and BACE, respectively). While BADE involves the tendency to neglect evidence that opposes one's view (Gawęda & Prochwicz, 2015), BACE refers to a hinderance in accepting information that is consistent with a true interpretation (McLean et al., 2017). Additionally, it has been proposed that individuals with psychosis display attentional biases toward pathology‐congruent material (Savulich et al., 2012). Individuals with psychosis have also been posited to process information that is consistent with their delusional beliefs, a mechanism driven by confirmation biases. These are mental processes that favour encoding of information in a manner that prevents a certain hypothesis from being modified by contradictory evidence (Oswald & Grosjean, 2004). Of note, theory of mind (ToM) deficits, or a difficulty in inferring other people's mental states, have been proposed to predispose individuals to delusions of persecution and reference (Frith, 1992). The latter are better understood as cognitive deficits, nevertheless, it is important to mention them, since they may be related to cognitive anomalies such as misperception biases.

While prior literature has repeatedly investigated the presence of thinking biases in psychosis, a limited amount of research has been carried out in terms of the cognitive anomalies implicated in paranoid psychosis specifically. Indeed, no systematic review investigating a wide range of thinking biases associated with PD has been conducted. This confers a rationale for reviewing this topic, with the hope of shedding light on the mechanisms underlying these processes. The objective of this paper is to summarize the evidence base regarding the types of cognitive biases found in individuals with psychosis characterized by PD, as well as investigating their role in the formation and maintenance of these symptoms.

2. METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009). The protocol of this review was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42020194169).

2.1. Search strategy

A systematic search of MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Global Health was conducted, including studies from the year 2000 to 15th June 2020. The following text strings were utilized: Persecut* OR Paranoid delusion* OR Paranoid ideation* OR Persecut* delusion* OR Idea* of persecut* OR Paranoi* AND Thinking bias* OR Cognitive bias* OR Thought* bias* OR Reasoning bias* OR Cognitive mediator* OR Reasoning anomal* OR Biased process* OR Biased cognition* AND Psycho* OR Schizo* OR Early psychosis OR Chronic psychosis.

2.2. Study selection

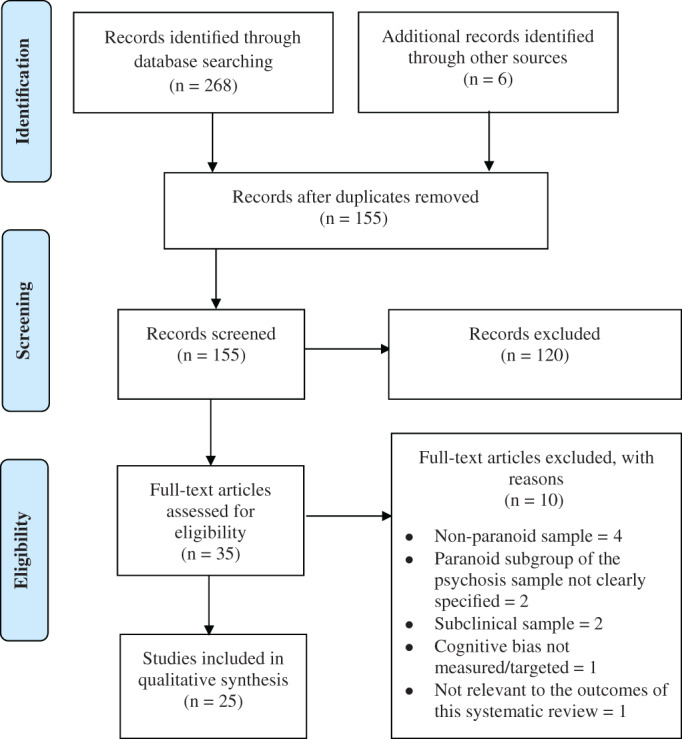

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to investigate cognitive biases present in psychotic patients with PD. The selection process was reported using the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009; see Figure 1). Studies were deemed eligible if they had been published in peer‐reviewed journals and were written in English. Study participants had to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder and had to exhibit clinical levels of paranoia, or PD. The presence of psychotic disorders and paranoid symptoms had to be assessed using reliable psychometric tools (e.g., DSM‐5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As for study design, all kinds of observational studies were considered.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram outlining the study screening procedure

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Unpublished/grey literature, study protocols and any type of review were excluded. Literature not written in English was omitted. Studies including individuals with a psychosis secondary to an organic pathology, or that was drug‐induced, were not considered. Studies were excluded if they only recruited individuals with subclinical psychosis or paranoia.

2.4. Data extraction process

An Excel spreadsheet was created to facilitate data extraction, including different variables such as author names, publication date, study design and sample characteristics.

2.5. Risk of bias in individual studies

The Effective Public Health Practice Project tool (EPHPP; Thomas, 2003) was utilized to assess the risk of biases of the included studies (see Table 1 for risk of bias assessment).

TABLE 1.

Risk of bias assessment

| Author (year) | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Data collection methods | Withdrawals and dropouts | Analyses (appropriateness) | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An et al. (2010) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Bentall and Swarbrick (2003) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Combs et al. (2009) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Fraser et al. (2006) | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Weak |

| Freeman et al. (2014) | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Freeman et al. (2012) | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Garety et al. (2013) | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Korkmaz and Can (2020) | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Weak |

| Langdon et al. (2010) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Lincoln et al. (2009) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| McKay et al. (2005) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| McKay et al. (2007) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Moritz and Laudan (2007) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Moritz et al. (2007) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Moutoussis et al. (2011) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Peer et al. (2004) | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Peters and Garety (2006) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Yes | Moderate |

| Pinkham et al. (2016) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Sanford and Woodward (2017) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Savulich et al. (2017) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| So et al. (2012) | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Moderate |

| Startup et al. (2008) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Taylor and John (2004) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Yes | Weak |

| Wittorf et al. (2012) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

| Woodward et al. (2006) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Yes | Strong |

2.6. Summary measures

Where provided by the papers included, standardized metrics were reported (namely effect sizes, odds ratios, confidence intervals and p‐values).

2.7. Planned methods of analysis

The results were recorded employing a formal narrative synthesis. The findings were grouped into clusters sharing the same theme, which allowed the identification of similarities between studies. The synthesis presented in the “results” section has been structured around the outcomes of interest.

3. RESULTS

Of 274 papers initially retrieved from the literature search, a total of 25 papers were included in the review. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of all included studies, while Table 3 reports the main findings. The results are summarized based on the type of bias investigated.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of studies

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample (number and diagnosis) | Mean age (SD) | Gender ratio | Symptoms measure | Cognitive bias investigated | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An et al. (2010) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 20 FES | 21.3 (5.0) | 8M/12F | SIPS, SCID | Attributional biases | Strong |

| 24 UHR | 20.0 (3.9) | 14M/10F | |||||

| 39 HC | 19.7 (3.5) | 16M/23F | |||||

| Bentall and Swarbrick (2003) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 57 SCZ,1 DD, 33 with acute PD | 34.47 (11.17) | 23M/10F | PANSS | NFC | Strong |

| 24 with remitted PD | 36.75 (9.86) | 14M/10F | |||||

| 57 HC | 33.04 (11.07) | 35M/22F | |||||

| Combs et al. (2009) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 32 SCZ with PD | 41.8 (9.5) | 17M/15F | SCID‐P | Attributional biases | Strong |

| 28 SCZ without PD | 43.0 (10.9) | 9M/19F | |||||

| 50 HC | 22.1 (4.8) | 9M/41F | |||||

| Fraser et al. (2006) | Cross‐sectional, comparative study | 15 SSD or DD with PD | 38.47 (12.73) | 9M/6F | PSYRATS | JTC, IU (construct related to NFC) | Weak |

| 15 Panic disorder | 41.0 (10.70) | 3M/12F | |||||

| 15 HC | 40.4 (12.61) | 9M/6F | |||||

| Freeman et al. (2014) | Cross‐sectional | 87 SCZ, 10 SAD, 10 DD, 16 psychosis NOS with PD | 40.6 (11.2) | 73M/50F | PANSS, PSYRATS | JTC | Moderate |

| Freeman et al. (2012) | Cross‐sectional | 111 SCZ, 9 SAD, 7 DD, 1 psychosis NOS with delusions (119 with PD) (2 missing data) | 41.1 (11.6) | 82M/48F | SAPS | Attentional, interpretation biases | Moderate |

| Garety et al. (2013) | Cross‐sectional | 257 SCZ, 40 SAD, 4 DD (192 with PD) | 37.6 (NS) | 211M/90F | PANSS, SCAN | JTC, BI | Moderate |

| Korkmaz and Can (2020) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 35 SCZ with PD | 32.91 (10.57) | 25M/10F | BPRS, SAPS, SANS | JTC | Weak |

| 31 SCZ without PD | 33.65 (9.72) | 23M/8F | |||||

| 31 GAD | 35.29 (11.12) | 11M/20F | |||||

| 31 HC | 33.77 (10.18) | 14M/17F | |||||

| Langdon et al. (2010) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 30 SCZ, 5 SAD (23 with PD) | 35.9 (10.4) | 23M/12F | DIP, PDI, SAPS | JTC, attributional biases | Strong |

| 34 HC | 32.0 (12.9) | 26M/8F | |||||

| Lincoln et al. (2009) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 45 SCZ, 3 DD, 2 SAD, 25 with acute PD | 35.4 (11.8) | 14M/11F | PANSS | Attributional biases | Moderate |

| 25 with remitted PD | 32.3 (9.7) | 15M/10F | |||||

| 50 HC, 25 with high subclinical paranoia | 33.4 (11.7) | 18M/7F | |||||

| 25 with low subclinical paranoia | 37.8 (12.0) | 10M/15F | |||||

| McKay et al. (2005) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 19 SCZ, 3 SAD, 3 BD (13 with acute PD, 12 with remitted PD) | 40.0 (10.42) | 10M/15F | SAPS, SANS | Attributional biases | Moderate |

| 19 HC | 35.89 (11.71) | 7M/12F | |||||

| McKay et al. (2007) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 18 SCZ, 2 SAD, 2 BD (11 with acute PD, 11 with remitted PD) | 40.36 (10.16) | 10M/12F | SAPS, SANS | JTC, NFC | Strong |

| 19 HC | 35.89 (11.71) | 7M/12F | |||||

| Moritz and Laudan (2007) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 24 SCZ (12 with PD) | 35.21 (11.29) | 16M/8F | M.I.N.I., PANSS | Attentional biases | Strong |

| 34 HC | 35.85 (13.23) | 18M/16F | |||||

| Moritz et al. (2007) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 25 SCZ, 10 SAD (19 with acute PD, 12 with remitted PD) | 34.23 (9.29) | 19M/16F | SCID | Attributional biases | Strong |

| 18 MDD | 39.83 (8.73) | 10M/18F | |||||

| 34 GAF | 35.35 (11.18) | 12M/22F | |||||

| 28 HC | 33.50 (10.23) | 10M/18F | |||||

| Moutoussis et al. (2011) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 36 SCZ, SAD or DD with acute PD | NS | NS | NS | JTC | Moderate |

| 29 SSD with remitted PD | 34.66 (10.35) | 18M/11F | |||||

| 46 MDD (20 with PD) | NS | NS | |||||

| 33 HC | 39.03 (13.96) | 14M/19F | |||||

| Peer et al. (2004) | Longitudinal | 68 SCZ (26 with paranoia), 10 SAD, 6 psychosis NOS, 2 BD, 4 other DSM disorder (1 missing data) | 35.7 (9.7) | 56M/35F | BPRS‐E | Emotion misperception biases | Moderate |

| Peters and Garety (2006) | Longitudinal, Case–control | 23 psychosis (8 with “bad‐me” and 8 with “poor‐me” paranoia) | 30.7 (7.2) | 21M/2F | MS, PDI, DSSI | JTC, attributional biases | Moderate |

| 22 MDD and/or Anxiety | 40.9 (13.6) | 11M/11F | |||||

| 36 HC | 27.7 (6.7) | 18M/18F | |||||

| Pinkham et al. (2016) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 38 SCZ, 28 SAD without PD | 37.98 (14.57) | 48M/18F | PANSS | Attributional, trustworthiness social judgement biases | Strong |

| 42 SCZ, 39 SAD with PD | 39.06 (11.70) | 54M/27F | |||||

| Sanford and Woodward (2017) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 41 SCZ (10 with PD) | NS | NS | M.I.N.I., SSPI | BADE, attributional biases | Moderate |

| 44 BD (2 with PD) | NS | NS | |||||

| 58 HC | NS | NS | |||||

| Savulich et al. (2017) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 32 SCZ with PD | 42.75 (7.72) | 19M/13F | M.I.N.I., PDI‐21 | JTC, interpretation biases | Strong |

| 29 SCZ without PD | 39.59 (8.80) | 19M/10F | |||||

| 29 HC | 37.41 (15.51) | 13M/16F | |||||

| So et al. (2012) | Longitudinal | 232 SCZ, 37 SAD or 4 DD (157 with PD) | 37.7 (SD NS) | 193M/80F | PANSS, PSYRATS, SAPS | JTC, BI | Moderate |

| Startup et al. (2008) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 20 SCZ, 3 SAD, 1 DD, 3 BD, 1 Personality disorder with PD | 34.68 (9.38) | 17M/11F | SCAN | JTC | Strong |

| 30 HC | 36.53 (10.25) | 21M/9F | |||||

| Taylor and John (2004) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 12 SCZ with PD | 43.9 (14.37) | 8M/4F | Interview by clinical staff (NOS) | Attentional, memory biases | Weak |

| 12 MDD | 42.88 (13.98) | 4M/8F | |||||

| 12 HC | 42.98 (9.7) | 7M/5F | |||||

| Wittorf et al. (2012) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 20 SCZ with PD | 35.3 (9.0) | 13M/7F | SCID‐I, item P1 of PANSS | JTC, attributional biases | Strong |

| 20 MDD | 36.3 (9.7) | 8M/12F | |||||

| 15 AN | 23.9 (5.7) | 0M/15F | |||||

| 55 HC | 31.7 (10.6) | 21M/34F | |||||

| Woodward et al. (2006) | Cross‐sectional, Case–control | 52 SCZ or SAD, 36 delusional (26 with PD) | 38.08 (9.89) | 28M/8F | SSPI | BADE | Strong |

| 16 non‐delusional (14 remitted) | 38.06 (9.11) | 11M/5F | |||||

| 24 HC | 39.46 (11.50) | 7M/17F |

Abbreviations: Diagnoses, symptoms and terminology: BADE, Bias against disconfirmatory evidence; BD, Bipolar disorder; DD, Delusional disorder; FES, First episode schizophrenia; F, Female; GAD, Generalized anxiety disorder; HC, Healthy controls; IU, Intolerance of uncertainty; JTC, Jumping to conclusions; M, Male; MDD, Major depressive disorder; NFC, Need for closure; NOS, Not otherwise specified; NS, Not specified; PD, Persecutory delusions; SAD, Schizoaffective disorder; SCZ, Schizophrenia; SSD, Schizophrenia spectrum disorder; UHR, Ultra‐high risk. Psychosis measures: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall & Gorham, 1962); BPRS‐E, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale‐ Extended version (Lukoff et al., 1986); DIP, Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis (Castle et al., 2006); DSSI, Delusions Symptom‐State Inventory (Foulds & Bedford, 1975); M.I.N.I., Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998); MS, Manchester Scale (Krawiecka et al., 1977); PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (Kay et al., 1987); PDI, Peter's Delusion Inventory (Peters et al., 1999; Peters et al., 2004); PSYRATS, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (Haddock et al., 1999); SANS, Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen, 1982); SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (Andreasen, 1984); SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (World Health Organization, 1992); SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV (First et al., 1996); SCID‐I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I (Wittchen et al., 1997); SCID‐P, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐Patient Edition (First et al., 2001); SIPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (McGlashan et al., 2003); SSPI, Signs and Symptoms of Psychotic Illness Scale (Liddle et al., 2002).

TABLE 3.

Overview of studies with main relevant findings

| Author (year) | Sample (number and diagnosis) | Mean age (SD) | Gender ratio | Cognitive bias investigated | Cognitive bias measure | Paranoia measure | Main relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An et al. (2010) | 20 FES | 21.3 (5.0) | 8M/12F | Attributional biases | AIHQ | PS, P6 item of PANSS |

FES reported higher hostility biases than HC (p = .037), which were correlated with PS paranoia scores (p = .001). UHR reported higher hostility and blame biases than HC (p = .015, p = .002, respectively), which were correlated with PS paranoia scores (p = .044, p = .022, respectively) and the P6 item of PANSS (p = .039, p = .021, respectively). No difference between FES and HC for blame and aggression biases (both p = 1.0). |

| 24 UHR | 20.0 (3.9) | 14M/10F | |||||

| 39 HC | 19.7 (3.5) | 16M/23F | |||||

| Bentall and Swarbrick (2003) | 57 SCZ,1 DD, 33 with acute PD | 34.47 (11.17) | 23M/10F | NFC | NFCS | P6 item of PANSS |

Acute and remitted subjects scored higher than HC on the NFCS (both p < .001), no difference was found between the patient groups. Compared to HC, both patient groups scored higher for need for order (p < .05), the acute ones scored higher for decisiveness (p < .01) and the remitted ones for discomfort in face of ambiguity (p < .05). |

| 24 with remitted PD | 36.75 (9.86) | 4M/10F | |||||

| 57 HC | 33.04 (11.07) | 35M/22F | |||||

| Combs et al. (2009) | 32 SCZ with PD | 41.8 (9.5) | 17M/15F | Attributional biases | AIHQ, IPSAQ | PS, PAI‐P. suspiciousness item score ≥5 on BPRS‐E |

Patients with PD exhibited higher PAB (p < .001), but no difference was found for EAB, when compared to non‐PD and HC. Significant differences were found across groups in terms of hostility (p < .0001), blame (p < .001) and aggression bias scores (p < .001), with paranoid subjects having higher scores. Hostility bias was a predictor of paranoia (p = .01). |

| 28 SCZ without PD | 43.0 (10.9) | 9M/19F | |||||

| 50 HC | 22.1 (4.8) | 9M/41F | |||||

| Fraser et al. (2006) | 15 SSD or DD with PD | 38.47 (12.73) | 9M/6F | JTC, IU (construct related to NFC) | Card version of the probabilistic reasoning task (60:40 ratio) by Dudley et al. (1997), IUS | PSYRATS |

No significant effect of group was found for number of items asked before coming to a conclusion (p = .24). No significant group‐stimuli interaction was found (p = .63). For emotionally‐related stimuli, all groups made decisions based on less information. For IU, subjects with PD and the psychiatric controls scored significantly higher than HC (p = .000). |

| 15 Panic disorder | 41.0 (10.70) | 3M/12F | |||||

| 15 HC | 40.4 (12.61) | 9M/6F | |||||

| Freeman et al. (2014) | 87 SCZ, 10 SAD, 10 DD, 16 psychosis NOS with PD | 40.6 (11.2) | 73M/50F | JTC, IU | BT (60:40), IUS | GPTS, PSYRATS‐delusions |

No difference between subjects with and without JTC in terms of paranoia levels and severity of PD (p = .522, p = .986, respectively). Patients with JTC had higher levels of negative symptoms (p = .028), poorer working memory (shown by poorer performance on three memory tasks, p = .03, 95% CI = 0.1, 1.8; p = .013, 95% CI = 0.3, 2.0; p = .003, 95% CI = 0.7, 3.5), lower levels of worry (p = .012; 95% CI = 0.9, 7.4) and lower levels of IU (p = .074; 95% CI = −0.9, 19.0). Lower levels of worry and poorer working memory predicted JTC (p = .005 and p = .002). |

| Freeman et al. (2012) | 111 SCZ, 9 SAD, 7 DD, 1 psychosis NOS with delusions (119 with PD) (2 missing data) | 41.1 (11.6) | 82M/48F | Attentional, interpretation biases | TA task, IoA task, SCS | 5 VAS for state paranoia | State paranoia was positively correlated with negative interpretation of ambiguous events (p = .028), anticipation of threat to self (p = .020), hyper‐alertness toward internal thoughts (p = .007) and public self‐consciousness (p < .001). |

| Garety et al. (2013) | 257 SCZ, 40 SAD, 4 DD (192 with PD) | 37.6 (NS) | 211M/90F | JTC, BI | BT using beads and a version using valenced words (60:40 & 85:15), MADS, EoE | Item 8 of SAPS, PSYRATS |

Around 50% of the patients with PD presented JTC on the 85:15 beads task and a considerable proportion had BI. JTC and BI were more commonly associated with grandiose delusions (ORs from 4.5 to 9 times higher). |

| Korkmaz and Can (2020) | 35 SCZ with PD | 32.91 (10.57) | 25M/10F | JTC | BT (60:40 & 90:10) | SAPS |

Subjects with PD requested less beads before making a decision on the 60:40 BT, compared to non‐paranoid (p = .018) and HC (p < .05). Paranoid subjects with JTC exhibited higher delusion scores on the SAPS (p = < .05), than those without. On the 60:40 BT, JTC was positively correlated with positive symptoms and impulsivity (both p = .003), while on the 90:10 version, JTC was positively associated with negative symptoms (p = .035). |

| 31 SCZ without PD | 33.65 (9.72) | 23M/8F | |||||

| 31 GAD | 35.29 (11.12) | 11M/20F | |||||

| 31 HC | 33.77 (10.18) | 14M/17F | |||||

| Langdon et al. (2010) | 30 SCZ, 5 SAD (23 with PD) | 35.9 (10.4) | 23M/12F | JTC, attributional biases | BT (85:10), IPSAQ | PS |

Patients requested fewer beads before coming to a decision (p = .03) and presented a stronger EAB (p = .01) than HC. No significant difference found for PAB (p = .10), but there was a tendency for PAB to be associated with paranoia across both groups (p = .02). |

| 34 HC | 32.0 (12.9) | 26M/8F | |||||

| Lincoln et al. (2009) | 45 SCZ, 3 DD, 2 SAD, 25 with acute PD | 35.4 (11.8) | 14M/11F | Attributional biases | IPSAQ | PC, P6 item of the PANSS |

No significant difference found for external‐situational and internal attributions across groups (p = .303, p = .679, respectively). The group with acute PD made more external‐personal attributions than remitted subjects and HC (all p < .05). No significant correlations found for external‐personal attributions for negative and positive events and the PC score within groups. |

| 25 with remitted PD | 32.3 (9.7) | 15M/10F | |||||

| 50 HC, 25 with high subclinical paranoia | 33.4 (11.7) | 18M/7F | |||||

| 25 with low subclinical paranoia | 37.8 (12.0) | 10M/15F | |||||

| McKay et al. (2005) | 19 SCZ, 3 SAD, 3 BD (13 with acute PD, 12 with remitted PD) | 40.0 (10.42) | 10M/15F | Attributional biases | IPSAQ | Item 8 of the SAPS, PPDQ |

EAB and PAB found in all participants, as all were more likely to take credit for positive events (p = .005) and blame others for negative events (p < .001). No significant difference across groups for EAB (p = .215) and PAB (p = .198), but those with acute PD showed PAB levels significantly greater than 0.5 (p = .001). HC made more external‐situational attributions than both clinical groups combined (p = .017) and no difference was found between clinical groups (p = .481). |

| 19 HC | 35.89 (11.71) | 7M/12F | |||||

| McKay et al. (2007) | 18 SCZ, 2 SAD, 2 BD (11 with acute PD, 11 with remitted PD) | 40.36 (10.16) | 10M/12F | JTC, NFC | BT (15:85 & 85:15), NFCS | SAPS |

No significant difference across groups in draws to decision on the BT (p = .436) and the clinical group was less confident in making a decision (p = .022). The clinical group had a higher overall NFC score than HC (p = .003), specifically they scored higher in some aspects (need for order, p = .006; desire for predictability, p = .003 and intolerance of ambiguity, p = .028). No significant correlations found between JTC and NFC (all p > .05). No significant correlations observed between NFC and PD in patients (p > .05), however, a non‐linear relationship was found between NFC and PD severity. |

| 19 HC | 35.89 (11.71) | 7M/12F | |||||

| Moritz and Laudan (2007) | 24 SCZ (12 with PD) | 35.21 (11.29) | 16M/8F | Attentional biases | IOR | P6 item of the PANSS | ATB found in subjects with and without PD, who showed faster response times for paranoia‐related stimuli than HC (p = .02). |

| 34 HC | 35.85 (13.23) | 18M/16F | |||||

| Moritz et al. (2007) | 25 SCZ, 10 SAD (19 with acute PD, 12 with remitted PD) | 34.23 (9.29) | 19M/16F | Attributional biases | ASQ‐B | Item 11 of the BPRS | positive outcomes and grandiose delusions was found (p = .05). |

| 18 MDD | 39.83 (8.73) | 10M/18F | |||||

| 34 GAF | 35.35 (11.18) | 12M/22F | |||||

| 28 HC | 33.50 (10.23) | 10M/18F | |||||

| Moutoussis et al. (2011) | 36 SCZ, SAD or DD with acute PD | NS | NS | JTC | BT (60:40) and a probabilistic reasoning task using valenced words by Dudley et al. (1997). | Item 19.012 of the SCAN and the item 4 of the PDI |

Rejection of the high‐sampling‐cost hypothesis as the mean of the sampling cost converged to near zero for both the paranoid (CS μ‐0.05) and healthy (μ −0.06) groups. JTC seemed to be caused by a higher cognitive noise observed in patients, compared to controls. Paranoid patients were seen to employ a non‐Bayesian reasoning style. |

| 29 SSD with remitted PD | 34.66 (10.35) | 18M/11F | |||||

| 46 MDD (20 with PD) | NS | NS | |||||

| 33 HC | 39.03 (13.96) | 14M/19F | |||||

| Peer et al. (2004) | 68 SCZ (26 with paranoia), 10 SAD, 6 psychosis NOS, 2 BD, 4 other DSM disorder (1 missing data) | 35.7 (9.7) | 56M/35F | Emotion misperception biases | Facial affect slides by Ekman & Friesen, (1976) | Paranoid factor of BPRS‐E |

Significant correlation between disgust misperception bias and paranoid scores (p = .05) at time 1, but no correlation for anger misperception bias (p = .60). When perseverative errors were considered, their interaction with disgust bias showed an even bigger effect on paranoid scores (p = .01). At time 2, anger and disgust misperception bias were not significantly correlated with paranoid scores (p = .59 and p = .92, respectively). |

| Peters and Garety (2006) | 23 psychosis (8 with “bad‐me” and 8 with “poor‐me” paranoia) | 30.7 (7.2) | 21M/2F | JTC, Attributional biases | BT (85:15), PIT | Item 15 of the PDI |

At baseline, psychotic subjects requested fewer beads than psychiatric (p < .001) and healthy controls (p < .05) and changed their estimates more than the HC (p < .01), but not the psychiatric controls (p > .1), when provided with contradictory evidence. At follow‐up, the psychotic group remained stable in terms of number of beads drawn (p > .1) and changed their estimates more than HC (p < .05), but not psychiatric controls (p > .1). At baseline, the “bad‐me” paranoid subgroup made significantly more internal attributions for negative events than the “poor‐me” group (p < .05), while no difference was found for positive events (p < .1). At follow‐up, no significant differences were found between paranoid groups (p > .1). |

| 22 MDD and/or Anxiety | 40.9 (13.6) | 11M/11F | |||||

| 36 HC | 27.7 (6.7) | 18M/18F | |||||

| Pinkham et al. (2016) | 38 SCZ, 28 SAD without PD | 37.98 (14.57) | 48M/18F | Attributional, trustworthiness social judgement biases | AIHQ, TT | P6 item of the PANSS | Subjects with PD presented stronger hostile, blame and trustworthiness biases (p = .005, p = .007, p = .002, respectively) than those without PD. |

| 42 SCZ, 39 SAD with PD | 39.06 (11.70) | 54M/27F | |||||

| Sanford and Woodward (2017) | 41 SCZ (10 with PD), | NS | NS | BADE, attributional biases | ASB Task | SSPI |

Self‐attribution ratings were higher for positive (rather than negative) scenarios and other‐person attribution ratings were higher for negative scenarios (all p < .001) across groups. No difference found for situational attribution ratings, irrespective of event (p = .477). No differences in terms of attributional biases and BADE between SCZ, BD and HC, nor between SCZ with and without PD (p > .06). Mania and disorganization correlated with self‐blame and situational attributions, while anxiety and depression were linked to self‐attributions and PAB. |

| 44 BD (2 with PD) | NS | NS | |||||

| 58 HC | NS | NS | |||||

| Savulich et al. (2017) | 32 SCZ with PD | 42.75 (7.72) | 19M/13F | JTC, interpretation biases | BT (60:40), SRT, SST, | P6 item of the PANSS, GPTS, PS |

SCZ subjects were more negatively biased than HC (paranoid vs. HC, p < .001, d = 1.04, 95% CI = .16, .48; non‐paranoid vs. HC, p = .007, d = .81, 95% CI = .09, .53). On the SST, only subjects with PD exhibited a stronger paranoid, rather than negative, interpretation (p = .006, d = .49, 95% CI = 3.87, 21.24), however, on the SRT, paranoia‐specific biases were also found in subjects without PD. The paranoid group requested the least number of beads and differed significantly from HC (p = .031, d = .74, 95% CI = −18.01, −65), but not from non‐paranoid patients (p = .25). |

| 29 SCZ without PD | 39.59 (8.80) | 19M/10F | |||||

| 29 HC | 37.41 (15.51) | 13M/16F | |||||

| So et al. (2012) | 232 SCZ, 37 SAD or 4 DD (157 with PD) | 37.7 (SD NS) | 193M/80F | JTC, BI | BT (85:15, 60:40 & valenced words) | ≥ 3 rating on SAPS |

BI was positively associated with greater delusional conviction at baseline and follow‐up (p < .01). JTC and BI remained stable over time (p = .16, p = .10, respectively). |

| Startup et al. (2008) | 20 SCZ, 3 SAD, 1 DD, 3 BD, 1 Personality disorder with PD | 34.68 (9.38) | 17M/11F | JTC | BT (60:40) | Paranoia‐related questions of SCAN, PSYRATS | Significantly more individuals in the PD group exhibited a JTC bias compared to HC (p < .001). |

| 30 HC | 36.53 (10.25) | 21M/9F | |||||

| Taylor and John (2004) | 12 SCZ with PD | 43.9 (14,37) | 8M/4F | Attentional, memory biases | PDT, WSC task, FR task | Interviews by clinical staff NOS |

No association between ATB and paranoia was observed. Subjects with PD did not show an ATB, as HC were faster than them at probe detection on the PDT (p < .001). A significant interaction between types of memory retrieval, stimuli and words was found for subjects with PD (p < .001), showing that on the FR task they recalled more positive personally‐salient words and on the WSC task they retrieved more positive and negative words, when compared to neutral ones. |

| 12 MDD | 42.88 (13.98) | 4M/8F | |||||

| 12 HC | 42.98 (9.7) | 7M/5F | |||||

| Wittorf et al. (2012) | 20 SCZ with PD | 35.3 (9.0) | 13M/7F | JTC, attributional biases | BT variant (80:20) by Speechley et al. (2010), IPSAQ‐R | P6 item of the PANSS |

There was a significant overall group effect (p = .003) for EAB, with the SCZ group presenting a significantly higher score than the psychiatric controls. No significant difference across groups observed for PAB (p = .241) and JTC (p = .336). In the SCZ sample, low mood, negative and depressive symptoms were associated to fewer draws to decision (p = .063, p = .067, p = .045, respectively), but no association was found for positive symptoms (p = .641) |

| 20 MDD | 36.3 (9.7) | 8M/12F | |||||

| 15 AN | 23.9 (5.7) | 0M/15F | |||||

| 55 HC | 31.7 (10.6) | 21M/34F | |||||

| Woodward et al. (2006) | 52 SCZ or SAD, 36 delusional (26 with PD) | 38.08 (9.89) | 28M/8F | BADE | BADE task | SSPI |

When lure interpretations were revealed on the second scenario of the task, there was a significant difference in BADE for patients vs HC (p < .001), but not between patient groups (p = .25). When revealed on the third scenario, there was a significant difference between patient groups (p < .05) but not between non‐delusional ones and HC (p = .11). BADE resulted specific to delusions (p < .05). |

| 16 non‐delusional (14 remitted) | 38.06 (9.11) | 11M/5F | |||||

| 24 HC | 39.46 (11.50) | 7M/17F |

Abbreviations: Diagnoses, symptoms and terminology: AN, Anorexia nervosa; ATB, Attention to threat bias; BADE, Bias against disconfirmatory evidence; BD, Bipolar disorder; CS, Cost of sampling; DD, Delusional disorder; EAB, Externalizing attributional bias; FES, First episode schizophrenia; F, Female; GAD, Generalized anxiety disorder; HC, Healthy controls; IU, Intolerance of uncertainty; JTC, Jumping to conclusions; M, Male; MDD, Major depressive disorder; NFC, Need for closure; NOS, Not otherwise specified; NS, Not specified; PAB, Personalizing attributional bias; PD, Persecutory delusions; SAD, Schizoaffective disorder; SCZ, Schizophrenia; SSD, Schizophrenia spectrum disorder; UHR, Ultra‐high risk. Cognitive biases and paranoia measures: AIHQ, Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (Combs et al., 2007); ASB task, Attributional Style BADE task (Sanford & Woodward, 2017); ASQ‐B, Attributional Style Questionnaire (Brunstein, 1986); BT, Beads Task (Huq et al., 1988); BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall & Gorham, 1962); BPRS‐E, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale‐ Extended version (Lukoff et al., 1986); EoE, Explanations of Experiences (Freeman et al., 2004); FR task, Free Recall task (Reference not provided); GPTS, Green et al. (2008); IPSAQ, Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire (Kinderman & Bentall, 1996); IPSAQ‐R, Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire‐ Revised (Moritz, Veckenstedt, et al., 2010); IoA task, Interpretation of Ambiguity task (Mathews & Mackintosh, 2000); IOR, Inhibition of Return paradigm (Posner & Cohen, 1984); IUS, Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Freeston et al., 1994); MADS, Maudsley Assessment of Delusions (Wessely et al., 1993); NFCS, Need For Closure Scale (Kruglanski et al., 1993); PAI‐P=Personality Assessment Inventory‐ Persecutory ideation subscale (Morey, 1991); PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (Kay et al., 1987); PC, Paranoia Checklist (Freeman et al., 2005); PDI, Peter's Delusion Inventory (Peters et al., 1999; Peters et al., 2004); PDT, Probe Detection Task (Reference not provided); PPDQ, Persecutory and Delusion‐Proneness Questionnaire (McKay, 2004); PS, Paranoia Scale (Fenigstein & Vanable, 1992; Smari et al., 1994); PSYRATS, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (Haddock et al., 1999); PIT, Pragmatic Inference Task (Winters & Neal, 1985); SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (Andreasen, 1984); SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (World Health Organization, 1992); SCS, Self‐Consciousness Scale (Fenigstein et al., 1975); SSPI, Signs and Symptoms of Psychotic Illness Scale (Liddle et al., 2002); SRT, Similarity Rating Task (Eysenck et al., 1991); SST, Scrambled Sentences Task (Wenzlaff, 1993); TA task, Threat Anticipation task (Kaney et al., 1997); TT, Trustworthiness Task (Adolphs et al., 1998); VAS, Visual analogue scales; WSC task, Word Stem Completion task (Reference not provided).

3.1. Jumping to conclusions

Twelve studies investigated this bias and conveyed mixed results. Five studies reported higher levels of JTC in individuals with psychosis compared to controls (Korkmaz & Can, 2020; Langdon et al., 2010; Peters & Garety, 2006; Savulich et al., 2017; Startup et al., 2008), while three found no significant differences (Fraser et al., 2006; McKay et al., 2007; Wittorf et al., 2012). McKay et al. (2007) observed that patients with acute and remitted PD were actually less confident in drawing conclusions, suggesting that JTC biases may not be essential in the formation or maintenance of this delusional subtype.

While Freeman et al. (2014) reported no differences in terms of paranoia and delusional severity between patients with and without JTC, one study showed that paranoid patients with JTC, as opposed to those without, exhibited PD with higher severity, suggesting that this bias may be a state marker dependent on delusional state (Korkmaz & Can, 2020). Conversely, two longitudinal studies found that psychosis patients request fewer beads during both the acute phase and at remission, suggesting that JTC may be a trait marker (Peters & Garety, 2006; So et al., 2012).

In terms of specificity, most studies showed that JTC is not exclusively associated with PD. Indeed, Garety et al. (2013), showed that JTC is more commonly present in individuals with grandiose delusions (GD). Additionally, two studies proposed that JTC is not specific to psychosis individuals presenting with delusions, as it has been observed in non‐delusional psychiatric patients and healthy controls (Fraser et al., 2006; Wittorf et al., 2012).

Of note, only two studies compared paranoid versus non‐paranoid patients. While one showed that JTC did not differ between the two groups (Savulich et al., 2017), suggesting no specificity for the bias, the other found that individuals with PD requested fewer beads on the hard version of the beads task (Korkmaz & Can, 2020).

3.2. Belief inflexibility

Two studies investigated Belief Inflexibility (BI). One longitudinal study reported BI to be present in 50%–75% of the delusional sample (57% of which exhibited PD) and found it to be positively associated with delusional conviction (So et al., 2012). Furthermore, it was shown to be stable over time, suggesting that it may be a trait bias contributing to delusion formation and maintenance. BI has been demonstrated in individuals with PD and GD, with a stronger association found in the latter, highlighting that this may not be specific to PD (Garety et al., 2013).

3.3. Attentional biases

In regard to an attentional bias to threat, patients with schizophrenia have been found to react faster than controls to cues after being presented with a paranoid stimulus, although this was not found to be specific to paranoid individuals (Moritz & Laudan, 2007).

While the aforementioned study observed this bias in both paranoid and non‐paranoid subjects, another showed that paranoid patients did not exhibit it, given that they were slower than healthy controls in detecting a cue, after being exposed to threatening stimuli (Taylor & John, 2004). Indeed, no association between this bias and paranoia was found. Therefore, the findings for this variable appear to be inconsistent.

A study by Freeman et al. (2012) identified additional attentional biases associated with paranoia. These authors found a positive correlation between state paranoia and the anticipation of threat occurring to self, a type of attentional style. Furthermore, increased attention toward one's thoughts and how one is perceived by others were found to be positively associated with paranoia. These attentional styles were proposed to cause a continuous search for danger, inducing a state of threat, thus, they are likely to be implicated in the maintenance of PD.

3.4. Need for closure

In two studies, NFC was observed in individuals with acute and remitted PD, who scored higher than healthy controls in some subcategories of the Need For Closure Scale (Bentall & Swarbrick, 2003; McKay et al., 2007). Thus, one could argue that NFC may be a trait bias, involved in the genesis and maintenance of PD. In one study, a complex relationship with paranoia was observed. NFC seemed to present a non‐linear association with PD severity, meaning that they are positively correlated up to a certain stage, after which NFC decreases and severity intensifies (McKay et al., 2007).

NFC was shown not to predict JTC, discrediting the hypothesis that intolerance of uncertainty (IU) may drive hasty decision‐making (McKay et al., 2007). The studies investigating IU reported high levels in individuals with PD (Fraser et al., 2006; Freeman et al., 2014) and, similarly, they found no association between IU and JTC. Particularly, Freeman et al. (2014) reported that IU scores were higher in paranoid patients who did not jump to conclusions, proposing that IU in psychosis may actually lead individuals to gather more information before reaching certainty.

3.5. Bias against disconfirmatory evidence

Two studies investigated BADE directly. Sanford and Woodward (2017), developed the Attributional Style BADE task, intending to measure BADE, as well as attributional biases, which were hypothesised to act additively on delusions. Against predictions, no differences in terms of these biases were found across patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and non‐clinical controls. Particularly, when paranoid and non‐paranoid patients were compared, no distinctions were observed. Another study showed a specificity of BADE for delusions (Woodward et al., 2006). In the BADE task, when disconfirmatory evidence was integrated on the second scenario proposed to participants, BADE was present in both delusional and non‐delusional patients with schizophrenia. However, when it was presented on the third scenario, BADE was shown to be stronger in delusional patients, while no difference was found between non‐delusional patients and healthy controls. Although the majority of participants exhibited PD, this study did not investigate its relationship with paranoia specifically. These results may suggest that BADE is associated with delusions in general, as opposed to being specific to PD.

A third study examined how psychosis patients react to disconfirmatory evidence (Peters & Garety, 2006). Of note, this aspect was not measured with the scope of assessing BADE, but as a variable of the Beads Task, to evaluate JTC. Surprisingly, the study showed that, when provided with contradictory information, patients tended to revise and change their initial estimates more than healthy controls (both at baseline and follow‐up).

3.6. Attributional biases

Ten studies investigated attributional biases of different kinds, conveying mixed results.

As for the Externalizing Attribution Bias (EAB), while a study found it to be exaggerated in schizophrenia patients (Langdon et al., 2010), others observed no differences between psychosis patients and healthy controls (Combs et al., 2009; McKay et al., 2005; Moritz et al., 2007; Sanford & Woodward, 2017). When considering paranoid patients specifically, two studies reported no significant differences for EAB in comparison to non‐paranoid individuals (Combs et al., 2009; Sanford & Woodward, 2017), suggesting that it may not be unique to paranoid patients. Furthermore, a study proposed that self‐serving biases may be more closely related to grandiose delusions, since a significant association between this delusional subtype and internalization of positive events was observed (Moritz et al., 2007).

In terms of the Personalizing Attributional Bias (PAB; also defined as ‘blame bias’), two studies reported that individuals with PD were more prone than non‐paranoid ones to present with this cognitive anomaly (Combs et al., 2009; Pinkham et al., 2016) (Of note, PAB is intended as the tendency to blame other people for negative events). Moritz et al. (2007) showed that paranoid patients tended to blame others not only for negative, but also positive events. It should be further noted that four studies reported no differences across chronic psychosis patients and controls (Langdon et al., 2010; McKay et al., 2005; Sanford & Woodward, 2017; Wittorf et al., 2012). As for first‐episode schizophrenia (FES) individuals, a study reported no significant differences between patients and controls (An et al., 2010). However, PAB was found to be associated with paranoia scores in ultra‐high risk (UHR) subjects, suggesting that it may be implicated in the formation of PD (An et al., 2010). As for studies that compared acutely paranoid and remitted patients, one found no differences in terms of an external‐personal attributional style (McKay et al., 2005). However, two other studies reported that acute patients exhibited a greater tendency to blame others, suggesting that PAB may be a state bias (Lincoln et al., 2009; Moritz et al., 2007). Interestingly, Sanford and Woodward (2017) suggested that particular symptoms, as opposed to diagnoses, are associated with distinct attributional biases. They reported that individuals with anxious and depressive symptoms presented with a PAB and tended to make self‐attributions, while those with disorganization and manic symptoms tended to attribute causality to situations and to blame themselves. While three studies found no association between self‐serving biases and paranoia, or positive symptoms in general (Combs et al., 2009; Lincoln et al., 2009; Wittorf et al., 2012), another found a correlation between PAB and paranoia across both patients and controls (Langdon et al., 2010).

No differences between paranoid and healthy subjects were reported in terms of internal‐personal attributions for positive and negative events (Lincoln et al., 2009). However, Peters and Garety (2006), made a distinction between patients with “poor‐me” and “bad‐me” paranoia, showing that the latter tended to make more internal attributions for negative circumstances, while the former presented with self‐serving biases. However, these differences were only found at baseline and not at remission, suggesting that these biases may depend on the delusional state.

As for situational attributional biases, patients with paranoia did not appear to attribute the cause of events to situations more than healthy controls (Lincoln et al., 2009; McKay et al., 2005).

Consistent results were found for the hostility attributional bias. The three studies investigating this attributional style observed it in psychosis patients, with two of them showing that it is stronger in paranoid individuals, as opposed to non‐paranoid ones (Combs et al., 2009; Pinkham et al., 2016), suggesting that it may be specific to this clinical population. Furthermore, An et al. (2010) found it to be elevated in FES and UHR individuals, showing that it is already present at the earliest stages of the disease. Therefore, one could argue that it may be involved in the genesis of PD. Additionally, the authors found a correlation between this bias and paranoia levels in FES subjects, while Combs et al. (2009) proposed it as a predictor of paranoia.

Finally, the aggression bias was investigated in two studies. While one reported no significant differences between FES subjects and controls (An et al., 2010), another observed it in chronic paranoid patients, although it was not found to predict paranoia (Combs et al., 2009).

3.7. Interpretation biases

Two studies investigated interpretation biases. Savulich et al. (2017) examined negative and paranoia‐related interpretation biases in schizophrenia patients with and without PD. On one of the tasks administered, paranoid patients showed a persecutory, rather than negatively valenced, interpretation bias. On another task, both paranoid and non‐paranoid patients were more strongly biased toward paranoid interpretations. Thus, specificity of this bias for paranoia could not be determined. Nevertheless, paranoid interpretation biases were proposed to be implicated in the formation and maintenance of PD. As for negative interpretations of ambiguous events, Freeman et al. (2012) observed a positive association with state paranoia. This bias was proposed to perpetuate a sense of threat and, thus, maintain paranoid ideation.

3.8. Memory biases

One study investigated memory biases in patients with PD, finding an implicit memory bias for positive and negative personally‐salient stimuli, highlighting the presence of both positive and negative core schemata (Taylor & John, 2004). Furthermore, patients were shown to present an explicit memory bias for positive personally‐relevant stimuli, which could reflect an attempt to preserve a positive self‐image.

3.9. Misperception biases

One study re‐analysed data from an interventional study performed on chronic schizophrenia patients (Peer et al., 2004). A disgust misperception bias, or a tendency to misperceive others' emotions as disgust, was found to be correlated with paranoid symptoms. After 6 months of psychological treatment, paranoia and its association with this bias were reduced, but this reduction was not attributed to treatment effects. Thus, this bias could be a state factor dependent on the severity of paranoid ideation. For this reason, it can be inferred that it may be implicated in delusion maintenance.

Pinkham et al. (2016) observed a trustworthiness judgement bias in paranoid patients, that is, a tendency for individuals to interpret others' faces as untrustworthy. This may be caused by an inability to correctly perceive others' intent, thus, one could argue that this bias may be linked to ToM deficits. Nevertheless, this study also investigated social competence and found no differences between patients with and without paranoia. Thus, it may be inferred that social cognitive biases, but not social cognitive functioning per se, are associated with paranoia.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review to investigate a wide range of thinking biases associated with PD.

Overall, JTC and self‐serving attributional biases were the most extensively investigated. The body of evidence for JTC suggests that it may not be as relevant in the formation of PD as initially predicted, while the literature for attributional biases is mixed. EAB were proposed to play a role in the maintenance of delusions, while PAB were observed in the prodromal stage and, thus, were suggested to also contribute to the formation of paranoid symptoms. Generally, all the biases identified were observed in individuals with PD, however, only hostility and trustworthiness judgement biases could be more confidently assumed to be specific to this clinical population. Indeed, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding other biases, as most studies did not compare individuals with and without PD. Nevertheless, BI, JTC and EAB were proposed to be more closely related to grandiose delusions, while BADE was also found in non‐paranoid individuals, suggesting that these biases may not be unique to PD. While disgust misperception biases were hypothesised to contribute to PD perseverance, but not their development, NFC was proposed to be implicated in both processes, as it was observed in acute and remitted psychosis patients. Consistent results were found for hostility biases, which were observed in UHR, FES and chronic paranoid patients, suggesting that they may be trait‐like factors involved in the genesis and maintenance of PD.

4.1. Studies limitations

Although most studies were rated as globally “strong” or “moderate” on the quality assessment tool, some methodological shortcomings have been identified. Of note, most studies utilized the beads task to measure JTC, which has been suggested to be methodologically questionable (Glöckner & Moritz, 2009). Additionally, different studies used distinct beads ratios. It could be argued that studies employing the easier version of the task, may report a JTC reasoning style in participants even in the absence of a bias. Indeed, individuals may be more confident in making a quick decision only because the difference in beads between the two jars is evident.

In terms of study design, it is important to note that only four studies directly compared individuals with and without PD, allowing to draw conclusions on whether the biases investigated are specific to paranoid patients. Furthermore, only three studies employed a longitudinal design. Thus, most studies could infer, but not prove, whether the biases are in fact a causal factor in the formation of PD.

As for sample representativeness, most studies scored “moderate.” Nevertheless, it is important to note that these studies included acutely paranoid patients, who are usually less likely to agree to participate in research investigations. For this reason, one could argue that the subjects included in the samples may have been those who were most motivated to participate, thus, they may not accurately reflect this clinical population.

Another limitation is the fact that the majority of participants were White. Individuals from Black ethnic minorities have been reported to have an excess prevalence rate of psychosis, when compared to their White counterparts (Qassem et al., 2015). Furthermore, African Americans have been reported to score higher on the Paranoia Scale (Combs et al., 2009). This suggests that the samples, for the most part, did not adequately reflect the diversity of the population.

4.2. Strengths and limitations of the review

A strength of this study is that it is unique, as no other review has investigated an extensive range of cognitive biases in the context of PD. Particular attention was paid in order to be as inclusive as possible, and no restrictions were made based on the types of cognitive biases to be considered. An independent hand search was conducted and relevant papers that were not captured in the search output were included. Nevertheless, the current review only included studies published in English, peer‐reviewed journals. Thus, some relevant evidence may have been missed. Furthermore, there is a possibility that the search strategy may have led to the involuntary omission of some relevant biases.

Only studies from the year 2000 to present were considered. This was intentionally done, in order to retrieve the most recent evidence. Additionally, study selection and data extraction were performed by two reviewers.

Most of the studies were of cross‐sectional nature, thus, in most cases, the role of the biases could only be inferred.

The trend of the quality of studies included was “moderate‐to‐strong.” This allowed a confident interpretation of the findings.

Notably, there is a discrepancy in the number of studies included for different biases. While the results of this review suggest that hostility and trustworthiness judgement biases may be specific to PD, as opposed to other biases such as JTC, it is important to acknowledge that this review has included a smaller body of literature involving the former biases. Thus, the findings provide limited evidence for the specificity of these biases in PD. Furthermore, while this review included a limited number of studies investigating some of the biases, such as BADE, BI and NFC, it is important to acknowledge that they have been repeatedly explored in psychosis research.

4.3. Clinical implications

The findings of this review highlight that providing treatment on the basis of an interventional‐causal approach, that is, specifically targeting these biases, may moderate change in delusional beliefs.

Over the years, the effect of a range of interventions targeting thinking biases and paranoia has been explored. A frequently used technique is metacognitive training (MCT), a group intervention that educates individuals about cognitive biases in psychosis (Moritz & Woodward, 2007). Research has shown that MCT reduces the frequency (medium‐to‐large effect size) and conviction (medium effect size) of PD (Gawęda et al., 2015). Several adaptations of this interventions have also been created, such as MCT+, which is delivered individually, rather than in a group setting (Moritz, Vitzthum, et al., 2010). The Maudsley Review Training Programme (MRTP) is another intervention developed on the basis of MCT, which targets primarily JTC and belief flexibility (Garety et al., 2015). This therapy was tested on patients with PD and it was shown to be effective in reducing both biases, as well as paranoid symptoms, with small‐to‐medium effect sizes (Garety et al., 2015). A study merging MRTP with four sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy reported even stronger results (Waller et al., 2015). The combined interventions were successful in reducing BI, delusional distress and conviction, as well as state paranoia with a bigger effect size, suggesting that they may be more effective in conjunction than provided separately. Overall, psychological interventions aimed at modifying cognitive biases, such as MCT and its adaptations, have been shown to significantly improve cognitive biases, positive symptoms, as well as cognitive and clinical insight, with a small‐to‐moderate effect size (Sauvé et al., 2020).

Over time, a variety of interventions targeting cognitive biases have been developed. Studies have shown that treatments targeting mechanisms that underlie delusions may be more effective than more generic routinely adopted interventions. Of note, most of the interventions seem to target JTC and BI in patients with PD. However, the results from this review suggest that other biases, such as hostility and trustworthiness judgement biases, may be more relevant in the formation and maintenance of PD. Thus, one could argue that interventions targeting biases specific to this delusional subtype should be prioritized. As such, already existing interventions targeting cognitive biases should be adapted, with the aim of modifying biases that are deemed to be specific to individuals suffering from paranoid psychosis.

4.4. Future research

Future research should focus on conducting longitudinal studies, which can determine whether biases are antecedents or epiphenomenons of delusions. Additionally, research directly comparing patients with and without PD should be performed, to determine the specificity of biases.

Further studies should investigate First Episode Psychosis and Ultra High Risk Psychosis samples, in order to identify which biases are present from the earliest stages of the disease and may contribute to PD formation.

Finally, there is a need to translate the knowledge gained from studies on cognitive biases into clinical practice. Interventions that target these biases in the context of paranoid psychosis should be further investigated.

4.5. Conclusions

This systematic review synthesized a range of cognitive biases present in individuals with psychosis exhibiting PD. Additionally, their role in the formation and maintenance of this delusional subtype was investigated. These findings provided insight into which biases seem to be more closely related to paranoid symptoms, suggesting possible avenues for clinical practice. Particularly, hostility and trustworthiness judgement biases appeared to be specific to this clinical population. Furthermore, hostility biases and NFC were proposed to contribute to the genesis and maintenance of PD. Although the vast majority of the literature investigated JTC and EAB, the findings reported were mixed. Interestingly, the results of this review seem to suggest that JTC, EAB and BI may be more relevant to other delusional subtypes, such as grandiose delusions.

Given the proposed implication of cognitive biases in the processes of persecutory delusion development and persistence, research should focus on modifying already existing interventions to directly target biases that are deemed to be specific to this delusional subtype.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr Anna Georgiades for her expertise and supervision. Furthermore, I would like to thank her for the constant guidance, encouragement and assistance that she provided throughout all aspects of this research project. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr Alexis Cullen and Professor Andrea Mechelli for their guidance and suggestions about how to carry out a systematic review.

Biographies

Giorgia De Rossi, BSc, MSc, PGDip, is a Graduate Mental Health Worker at the Barnet, Enfield and Haringey (BEH) Mental Health Trust, National Health Service (NHS).

Anna Georgiades, PhD, DClinPsy, BABCP, is the Deputy Programme Director for the Early Intervention MSc and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King's College London. She is also a Senior Clinical Psychologist for the Brent Early Intervention Service in the National Health Service (NHS).

De Rossi, G. , & Georgiades, A. (2022). Thinking biases and their role in persecutory delusions: A systematic review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 16(12), 1278–1296. 10.1111/eip.13292

Giorgia De Rossi and Anna Georgiades contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Aakre, J. M. , Seghers, J. P. , St‐Hilaire, A. , & Docherty, N. (2009). Attributional style in delusional patients: A comparison of remitted paranoid, remitted nonparanoid, and current paranoid patients with nonpsychiatric controls. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(5), 994–1002. 10.1093/schbul/sbn033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs, R. , Tranel, D. , & Damasio, A. R. (1998). The human amygdala in social judgment. Nature, 393, 470–474. 10.1038/30982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- An, S. K. , Kang, J. I. , Park, J. Y. , Kim, K. R. , Lee, S. Y. , & Lee, E. (2010). Attribution bias in ultra‐high risk for psychosis and First‐episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 118(1–3), 54–61. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, N. C. (1982). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Definition and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39, 784–788. 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070020005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, N. C. (1984). The scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). The University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Bentall, R. P. , & Swarbrick, R. (2003). The best laid schemas of paranoid patients: Autonomy, sociotropy and need for closure. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 76(2), 163–171. 10.1348/147608303765951195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein, J. C. (1986). Attributional style and depression: First results on the reliability and validity of a German attributional styles questionnaire. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 7, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, D. J. , Jablensky, A. , & McGrath, J. J. (2006). The diagnostic interview for psychoses (DIP): Development, reliability and applications. Psychological Medicine, 36, 69–80. 10.1017/S0033291705005969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid, J. W. , Ullrich, S. , Kallis, C. , Keers, R. , Barker, D. , Cowden, F. , & Stamps, R. (2013). The relationship between delusions and violence: Findings from the East London First episode psychosis study. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(5), 465–471. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs, D. R. , Penn, D. L. , Micheal, O. , Basso, M. R. , Wiedeman, R. , Siebenmorgan, M. , Tiegreen, J. , & Chapman, D. (2009). Perceptions of hostility by persons with and without persecutory delusions. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 14(1), 30–52. 10.1080/13546800902732970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs, D. R. , Penn, D. L. , Wicher, M. , & Waldheter, E. (2007). The ambiguous intentions hostility questionnaire (AIHQ): A new measure for evaluating hostile social‐cognitive biases in paranoia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 12(2), 128–143. 10.1080/13546800600787854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, R. J. , John, C. H. , Young, A. W. , & Over, D. E. (1997). The effect of self‐referent material on the reasoning of people with delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(4), 575–584. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, M. W. , Mogg, K. , May, J. , Richards, A. , & Mathews, A. (1991). Bias in interpretation of ambiguous sentences related to threat in anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(2), 144–150. 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A. , Scheier, M. F. , & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self‐consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 522–527. 10.1037/h007676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A. , & Vanable, P. A. (1992). Paranoia and self‐consciousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(1), 129–138. 10.1037//0022-3514.62.1.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B. , Gibbon, M. , Spitzer, R. L. , Williams, J. B. , & Benjamin, L. J. (2001). User's guide for the structured interview for DSM‐IV personality disorders. New York State Psychiatric Research Institute, Biometrics Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B. , Spitzer, R. L. , Gibbon, M. , & Williams, J. W. (1996). Structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV Axis I disorders: Patient edition (SCID‐I/P), version 2. New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometric Research. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, G. A. , & Bedford, A. (1975). Hierarchy of classes of personal illness. Psychological Medicine, 5, 181–192. 10.1017/s0033291700056452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, J. , Morrison, A. , & Adrian, W. (2006). Cognitive processes, reasoning biases and persecutory delusions: A comparative study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(4), 421–435. 10.1017/S1352465806002852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D. , Dunn, G. , Fowler, D. , Bebbington, P. , Kuipers, E. , Emsley, R. , Jolley, S. , & Garety, P. (2012). Current paranoid thinking in patients with delusions: The presence of cognitive‐affective biases. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(6), 1281–1287. 10.1093/schbul/sbs145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D. , Garety, P. A. , Bebbington, P. E. , Smith, B. , Rollinson, R. , Fowler, D. , Kuipers, E. , Ray, K. , & Dunn, G. (2005). Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non‐clinical population. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(5), 427–435. 10.1192/bjp.186.5.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D. , Garety, P. A. , Fowler, D. , Kuipers, E. , Bebbington, P. E. , & Dunn, G. (2004). Why do people with delusions fail to choose more realistic explanations for their experiences? An empirical investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(4), 671–680. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D. , Garety, P. A. , Kuipers, E. , Fowler, D. , & Bebbington, P. E. (2002). A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41(4), 331–347. 10.1348/014466502760387461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D. , Startup, H. , Dunn, G. , Černis, E. , Wingham, G. , Pugh, K. , Cordwell, J. , Mander, H. , & Kingdon, D. (2014). Understanding jumping to conclusions in patients with persecutory delusions: Working memory and intolerance of uncertainty. Psychological Medicine, 44(14), 3017–3024. 10.1017/S0033291714000592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston, M. H. , Rhéaume, J. , Letarte, H. , Dugas, M. J. , & Ladouceur, R. (1994). Why do people worry? Personality and Individual Differences, 17(6), 791–802. 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frith, C. D. (1992). Essays in cognitive psychology. The cognitive neuropsychology of schizophrenia. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Garety, P. A. , Freeman, D. , Jolley, S. , Dunn, G. , Bebbington, P. E. , Fowler, D. G. , Kuipers, E. , & Dudley, R. (2005). Reasoning, emotions, and delusional conviction in psychosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(3), 373–384. 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety, P. A. , Gittins, M. , Jolley, S. , Bebbington, P. , Dunn, G. , Kuipers, E. , Fowler, D. , & Freeman, D. (2013). Differences in cognitive and emotional processes between persecutory and grandiose delusions. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(2), 629–639. 10.1093/schbul/sbs059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety, P. A. , Kuipers, E. , Fowler, D. , Freeman, D. , & Bebbington, P. E. (2001). A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 31(2), 189–195. 10.1017/s0033291701003312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety, P. A. , Waller, H. , Emsley, R. , Jolley, S. , Kuipers, E. , Bebbington, P. , Dunn, G. , Fowler, D. , Hardy, A. , & Freeman, D. (2015). Cognitive mechanisms of change in delusions: An experimental investigation targeting reasoning to effect change in paranoia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(2), 400–410. 10.1093/schbul/sbu103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawęda, Ł. , Krężołek, M. , Olbryś, J. , Turska, A. , & Kokoszka, A. (2015). Decreasing self‐ reported cognitive biases and increasing clinical insight through meta‐cognitive training in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experiemental Psychiatry, 48, 98–104. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawęda, Ł. , & Prochwicz, K. (2015). A comparison of cognitive biases between schizophrenia patients with delusions and healthy individuals with delusion‐like experiences. European Psychiatry, 30(8), 943–949. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner, A. , & Moritz, S. (2009). A fine‐grained analysis of the jumping‐to‐conclusions bias in schizophrenia: Data‐gathering, response confidence, and information integration. Judgment and Decision making, 4(7), 587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. L. , Freeman, D. , Kuipers, E. , Bebbington, P. , Fowler, D. , Dunn, G. , & Garety, P. A. (2008). Measuring ideas of persecution and social reference: The Green et al. Paranoid thought scales (GPTS). Psychological Medicine, 38(1), 101–111. 10.1017/S0033291707001638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, G. , McCarron, J. , Tarrier, N. , & Faragher, F. B. (1999). Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: The psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS). Psychological Medicine, 29, 879–889. 10.1017/s0033291799008661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq, S. F. , Garety, P. A. , & Hemsley, D. R. (1988). Probabilistic judgements in deluded and non‐deluded subjects. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 40(4), 801–812. 10.1080/14640748808402300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaney, S. , Bowen‐Jones, K. , Dewey, M. E. , & Bentall, R. P. (1997). Two predictions about paranoid ideation: Deluded, depressed and normal participants' subjective frequency and consensus judgments for positive, neutral and negative events. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(3), 349–364. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S. R. , Fiszbein, A. , & Opler, L. A. (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 13(2), 261–276. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman, P. , & Bentall, R. P. (1996). A new measure of causal locus: The internal, personal and situational attributions questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 20(2), 261–264. 10.1016/0191-8869(95)00186-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, S. A. , & Can, S. S. (2020). The jumping to conclusions bias associated with symptoms in schizophrenia: Which factors influence this bias? Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 32(4), 449–459. 10.1080/20445911.2020.1764570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krawiecka, M. , Goldberg, D. , & Vaughan, M. (1977). A standardised psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 55(4), 229–308. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A. W. , & Fishman, S. (2009). The need for cognitive closure. In Leary M. R. & Hoyle R. H. (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 343–353). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A. W. , Webster, D. M. , & Klem, A. (1993). Motivated resistance and openness to persuasion in the presence or absence of prior information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 861–876. 10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, R. , Ward, P. B. , & Coltheart, M. (2010). Reasoning anomalies associated with delusions in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(2), 321–330. 10.1093/schbul/sbn069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, P. F. , Ngan, E. C. , Duffield, G. , & Warren, A. J. (2002). Signs and symptoms of psychotic illness (SSPI): A rating scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 45–50. 10.1192/bjp.180.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, T. M. , Mehl, S. , Exner, C. , Lindenmeyer, J. , & Rief, W. (2009). Attributional style and persecutory delusions. Evidence for an event independent and state specific external‐personal attribution bias for social situations. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 297–302. 10.1007/s10608-009-9284-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff, D. , Liberman, R. P. , & Nuechterlein, K. (1986). Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 12, 578–593. 10.1093/schbul/12.4.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, A. , & Mackintosh, B. (2000). Induced emotional interpretation bias and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(4), 602–615. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan, T. H. , Miller, T. J. , Woods, S. W. , Rosen, J. L. , Hoffman, R. E. , & Davidson, L. (2003). Structured interview for prodromal syndromes (SIPS). Version 4.0. Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, R. (2004). “Sleights of mind”: Delusions and self‐deception. Macquarie University. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]