Abstract

Introduction

Androgenetic alopecia is the most common cause of hair loss in both males and females. In a society that places significant value on hair and associates it with attractiveness, a lack there of can have damaging psychological consequences. The psychosocial impact of hair loss is often overlooked due to the medically benign nature of offending conditions. Addressing the psychological aspects of androgenetic alopecia can improve holistic patient care and patient outcomes.

Methods

A search was conducted in PubMed using the following search strategy: androgenetic alopecia AND anxiety OR depression OR psychological OR psychosocial OR self‐esteem. Studies were excluded if they focused on any other type of alopecia or were published in a language other than English.

Results

A total of 13 studies were retained after the initial search process. The included studies date from 1992 to 2021. They all conclude that androgenetic alopecia serves as a significant psychosocial stressor in the lives of those affected. It impairs quality of life according to multiple measures.

Conclusion

The data examined from these studies shed light on the increased need to attend to the psychosocial comorbidity associated with androgenetic alopecia. These hair‐loss patients often present to dermatology clinics to seek treatment but would also benefit from psychological support.

Keywords: androgenetic alopecia, hair disorders, psychocutaneous disorders, psychodermatology, psychotrichology

1. INTRODUCTION

Androgenetic alopecia is a common dermatologic condition characterized by progressive hair loss. The hair loss generally begins after puberty and is more commonly seen in males than females. It affects up to 80% of males and 50% of females over the course of their lifetime. 1 The hair loss is a result of dihydrotestosterone (DHT)’s effect on androgen‐sensitive hair follicles, which leads to miniaturization of the follicle and a shortened hair growth cycle. 1 In males, this presents as recession of the frontal hairline, thinning of hair over the vertex scalp, and eventual balding. In females, this primarily presents with hair thinning over the vertex scalp. Although it is often believed to be a benign medical condition, androgenetic alopecia can have a dramatic effect on one's appearance and self‐esteem. In our society, a head full of hair is a key component of the ideal body image. 2 Therefore, hair loss can drastically reduce body image satisfaction. 3 Those affected by hair loss often feel they look older than they are and fear social rejection when looking for a romantic partner. 4 Not only do those suffering from hair loss worry about a loss of physical attractiveness, but they also perceive a loss of social attractiveness. People often correlate physical attractiveness to socially desirable traits such as friendliness when they know nothing more about a person. 2 When people understand that hair loss puts them at a disadvantage from a social perspective, it can have a significant impact on their psychological well‐being.

Current treatment options for androgenetic alopecia include minoxidil, 5alpha‐reductase inhibitors, hormonal therapy, and hair transplantation, but the efficacy of these treatments varies widely. PRP and low‐level laser light therapies are relatively new treatment modalities with promising anecdotal outlooks. This is a fast‐growing area of research, and as such, less compelling data are available to support these new treatments. It is certain that addressing the psychological aspects of androgenetic alopecia can improve patient outcomes. Most systematic reviews to date have solely focused on alopecia areata, which has an autoimmune origin and different treatment options. The aim of this review is to focus on the psychosocial comorbidity associated with androgenetic alopecia specifically.

2. METHODS

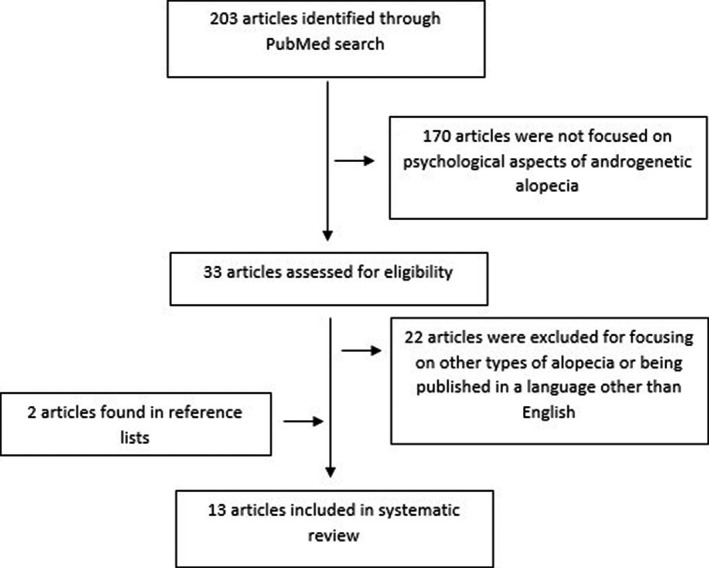

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. To analyze literature from inception to August 20, 2021, the following search strategy for titles and abstracts in PubMed was used: androgenetic AND alopecia AND anxiety OR depression OR psychological OR psychosocial OR self‐esteem. Article reference lists were also examined. Studies were excluded if they focused on alopecia areata, treatment efficacy, or were published in a language other than English. Studies were evaluated in chronological order. A flow diagram of the search process can be seen in Figure 1. Table 1 was also included to facilitate easy referencing of the included studies.

FIGURE 1.

Flow Diagram of Systematic Search Process

TABLE 1.

Included Studies by Chronological Order

| Source, Time Frame, and Location | Participant Characteristics | Measures of Psychosocial Well‐Being |

|---|---|---|

|

Cash TF 5 1992 Rural Virginia |

145 males (divided according to Norwood‐Hamilton chart ratings) | Hair Loss Effects Questionnaire |

|

Cash TF, Price VH, & Savin RC 6 1993 San Francisco and New Haven |

56 female controls 96 females with AA 60 males with AA |

Multidimensional Body‐Self Relations Questionnaire Hair Loss Effects Questionnaire |

|

Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, et al. 7 1994 Netherlands |

58 females with AA | Interview (Asked questions related to significance of hair, distress secondary to hair loss, and psychosocial maladjustment) |

|

Camacho FM & García‐Hernández M 8 1993–1995 Spain |

100 females with AA 100 males with AA |

Questionnaire (Related to behavior secondary to hair loss) |

|

Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, et al. 10 2001 Germany |

50 females with AA or diffuse alopecia | Hairdex |

|

Williamson D, Gonzalez M, & Finlay AY. 3 2001 United Kingdom |

65 females with AA 13 males with AA All members of an alopecia support group |

Alopecia Disability Questionnaire (Including Dermatology Life Quality Index & Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) |

|

Lee HJ, Ha SJ, Kim D, et al. 11 2002 Korea |

130 nonbalding females 90 nonbalding males 30 balding males |

Questionnaire (Perceptions of balding men) |

|

Kranz D 12 2011 Germany |

160 university students (divided according to Norwood‐Hamilton chart ratings and coping mechanism) | Questionnaires (Related to coping strategies and level of distress secondary to hair loss) |

|

Zhuang X, Zheng Y, Xu J, et al. 13 2013 China |

125 females with AA |

Visual Analog Scale Dermatology Life Quality Index |

|

Gupta S, Goyal I, & Mahendra A 14 2019 India |

200 males with AA |

Dermatology Life Quality Index Hair‐Specific Skindex−29 |

|

Titeca G, Goudetsidis L, Francq B, et al. 15 2020 13 European Countries |

115 dermatologic patients with hair diseases (37 with alopecia areata and 20 with AA) |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Dermatology Life Quality Index |

|

Zac et al. 16 2021 Brazil |

31 females with AA | Dermatology Life Quality Index |

|

Huang C, Fu Y, & Chi C. 17 Inception to 2021 Taiwan |

41 Studies (7995 Patients) |

Dermatology Life Quality Index Hair‐Specific Skindex−29 Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

Abbreviations: AA, androgenetic alopecia.

3. RESULTS

Studies analyzing the psychological sequelae of androgenetic alopecia date back to the 1990s. One study in particular compared balding and nonbalding males on a variety of psychological measures. 5 145 male participants were recruited from barber shops in rural Virginia and took part in a 90 min assessment. These men were not seeking dermatologic treatment. Participants were 96% white, 31% married, and had considerable occupational variety. 5 During their assessment, they used a Norwood–Hamilton chart to classify their hair loss patterns and filled out a Hair Loss Effects Questionnaire (HLEQ) to assess any emotional, cognitive, or behavioral changes since the onset of hair loss. Based on their evaluations, participants were classified into one of three groups: no hair loss, low hair loss, or high hair loss. More than 30% of high‐hair‐loss males reported increased cognitive preoccupation and behavioral coping because of their hair loss. 6 Behavioral coping mechanisms included trying to compensate for hair loss by improving physique, dressing nicer, wearing hats, and seeking reassurance about their appearance. 5 Most high‐hair‐loss males also indicated that their hair loss increased negative socioemotional events. 5 These negative socioemotional events included fear that others would notice, looking older than their actual age, feeling less attractive, feeling hopeless about their hair loss, and getting teased by their peers. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) comparing low‐hair‐loss and high‐hair‐loss groups found that high‐hair‐loss males had significantly more negative socioemotional impact (p < 0.01), more preoccupation with their hair loss (p < 0.05), and more involvement in coping activities (p < 0.10). 5 High‐hair‐loss males were also found to have significantly more body image dissatisfaction than their no‐hair‐loss counterparts (p < 0.05). 5 Males under the age of 26 reported the most intense preoccupation and coping efforts in response to their hair loss (p < 0.05). 5 Single males also reported more negative socioemotional effects than their married counterparts (p < 0.05). 5 Another study conducted by Cash et al. (1993) compared the psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia in males vs. females. This study looked at newly referred patients with androgenetic alopecia (96 females, 60 males, and 56 female control patients). 6 These patients were selected from dermatology centers in San Francisco and New Haven. Standardized inventories were administered to all 3 groups. Their dermatologists were also asked to assess each participant's hair loss using a Norwood–Hamilton chart. One inventory, the Multidimensional Body‐Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ), assessed attitudes toward body image satisfaction. A HLEQ was also administered to assess which psychosocial effects the patients attributed to their hair loss. ANOVAs comparing hair‐loss females to hair‐loss males found on average that females experienced more adverse psychosocial effects of hair loss, a greater reduction of positive life events, and more coping efforts. 6 The female hair‐loss group also reported more negative feelings about their appearance than did the male hair‐loss group or female control group. 6 Hair‐loss females were also more dissatisfied with the state of their hair than hair‐loss males. When compared with their male counterparts, hair‐loss females also reported higher social anxiety, lower self‐esteem, and less life satisfaction. 6 The HLEQ results revealed that for both sexes, the more hair loss they perceived themselves to have, the worse its impact. More perceived hair loss correlated to more adversity. The patients’ reported adversity could not be predicted by their dermatologists’ objective Norwood‐Hamilton ratings. 6

In 1994, a study on androgenetic alopecia was conducted in exclusively female patients. 7 They interviewed 58 females with androgenetic alopecia who were actively seeking medical treatment. Out of the 58 participants, 88% reported hair loss to have a negative effect on their daily life, 75% reported that their hair loss had a negative impact on their self‐esteem, and 50% reported social problems because of their hair loss. 7 One large retrospective study aimed to evaluate the psychological features of male and female patients with androgenetic alopecia in the country of Spain. 8 They evaluated 100 females and 100 males who had been diagnosed with androgenetic alopecia at their clinic in the Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena in Sevilla, Spain from the years 1993–1995. 8 They found that depression was more commonly seen in female patients than male patients (55% vs. 3%) but anxiety (78% vs. 41%) and aggressiveness (22% vs. 4%) were more frequent in male patients than female patients. 8 The most prevalent psychological symptom in women was depression (55%): However, 44% of those affected described the depression as “minor.” 8 The higher rate of aggressiveness in the men also correlated to a higher loss to follow‐up among male patients. 8 A study by Williamson (2001) tried to quantify the effect of hair loss on quality of life. In this study, an alopecia disability questionnaire, which included the original Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire and a shortened version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), was given to members of an alopecia support group. Out of 78 total participants, there was a 6:1 female/male ratio, and the majority did not know the cause of their hair loss. 3 The mean DLQI score was 8.3, which compares with those of 8.9 for severe psoriasis patients and 12.5 for atopic dermatitis patients. 3 In general, DLQI scores 0−1 indicate no effect on patient's life, scores 2–5 indicate a small effect on patient's life, and scores 6–10 indicate a moderate effect on patient's life. 9 A DLQI score between 11 and 20 indicates a very large effect on patient's life. 9 74% of participants also had a CES‐D score greater than 8, suggesting that they may have clinical depression. 3 They found a positive correlation, r=0.62 (p < 0.0001, Spearman Rank correlation) between the DLQI scores and CES‐D scores. 3 The participants were also asked utility questions in order to assess the value they placed on their hair. 98.6% of participants preferred a complete cure for their condition over a one‐time $692 US dollars payment. 3 When asked what they would pay to theoretically cure their hair loss, 34% of participants were willing to pay up to 50% of their annual income. 3 An open‐ended question on the questionnaire asked what the most important consequence of hair loss was to them personally. 30% of participants cited loss of self‐confidence whereas 22.8% cited low self‐esteem and more self‐consciousness. 3 In another open‐ended question, 40% of participants reported that their doctor had been “dismissive” or “unsupportive” and another 18.5% of participants said their doctor offered no treatment options. 3

A study by Schmidt et al. (2001) utilized the Hairdex, a tool used to measure quality of life in patients with hair loss, to assess how quality of life is affected by certain coping mechanisms. They looked at 55 female patients who were diagnosed with androgenetic or diffuse alopecia. Their findings concluded that highly visible hair loss led to a more negative impact on functioning, emotional regulation, self‐confidence, and feelings of stigmatization. 10 The Hairdex results revealed that participants experienced a comparable level of impairment to those patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis in the domains of emotion and functioning. 10 This study also revealed that it was not just the severity of hair loss that predicted Hairdex responses but individual personality traits and associated coping patterns as well. 10 Two small groups of participants were identified to have more maladaptive coping patterns that ranged from body dysmorphic to mood disorder tendencies. These groups were made up of females with both androgenetic and diffuse alopecia diagnoses. The females who were deemed to have a maladaptive coping pattern had stronger subjective impairment than other patients but not higher levels of hair loss. 10

A study was conducted in Korea in 2002 assessing the perception of baldness in society. They distributed a questionnaire on the perception of balding men to 130 nonbalding females, 90 nonbalding males, and 30 balding males. The questionnaire results revealed that balding males were perceived as being older and less attractive than nonbalding males by over 90% of the total respondents. 11 Less than 50% of respondents also perceived the balding men to be less confident, duller, and less potent. 11 Significantly more female respondents than male respondents perceived the balding men to be less attractive (p < 0.05). 11 Significantly more balding men than nonbalding men perceived the balding men to appear less confident (p < 0.05). 11 Over 90% of all of the respondents believed the balding men also had a disadvantage in dating or marriage. 11 One study found that acceptance of male hair loss counteracts psychological distress. 12 This study looked at how 160 university students, ages 18–30 years, coped with androgenetic alopecia. 12 These participants had varying degrees of hair loss according to the Norwood‐Hamilton scale. The participants were divided into one of three groups based on their hair loss coping strategy. These coping strategies included compensation, avoidance, and acceptance. Compensation and avoidance were associated with high levels of distress whereas acceptance was negatively related to distress, especially at advanced stages of hair loss. 12

A study by Zhuang et al. (2013) found that treating androgenetic alopecia with minoxidil greatly improved patients’ quality of life. 13 Patients were classified using Ludwig criteria and evaluated with a DLQI questionnaire at baseline and after 12 months of treatment. The DLQI scores were highest in the group with the greatest severity of hair loss (p < 0.05). 13 Overall, this study concluded that androgenetic alopecia in females substantially declines quality of life in patients and treatment with minoxidil can improve their quality of life.

In 2019, a study analyzing the impact of androgenetic alopecia on quality of life confirmed that the condition has a profound, negative impact on patients’ quality of life. 14 200 male patients with diagnosed androgenetic alopecia were assessed using the DLQI and hair‐specific Skindex‐29. Many of these participants (41.5%) were between the ages of 21–30 years, and 50% of the participants had a positive family history for androgenetic alopecia. 14 The mean DLQI score for the study was 13.52, and the most affected parameter was personal relations. 14 A large multicenter study assessed the psychological burden of different hair diseases in patients vs. healthy controls. 15 They evaluated 115 dermatologic patients with hair diseases; 37 of whom had alopecia areata and 20 of whom had androgenetic alopecia. 15 Patients with hair loss were found to have lower education levels than healthy controls and reported higher numbers of stressful life events during the last six months. 15 Each participant had their clinician rate their hair loss as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed among participants using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The questionnaire includes seven items assessing symptoms of anxiety and seven items assessing symptoms of depression. A score of 0–3 can be assigned to each item, and a score from 0 to 7 is considered normal whereas anything above 11 prompts further evaluation. The HADS mean scores in the hair loss group (anxiety 7.9 and depression 5.4) were significantly higher than the mean scores in the control group (anxiety 5.6 and depression 3.6) (p < 0.001). 15

Similar to zhuang et al.’s study, Zac et al. (2021) evaluated the psychological, social, and quality of life effects of androgenetic alopecia in females. They looked at 31 female participants with diffuse central hair thinning who were prescribed 5% minoxidil to use daily for 6 months. Participants responded to a clinical questionnaire after treatment and 83.9% of participants were satisfied with their treatment results. 16 After at least 6 months of treatment with minoxidil, hair loss still affected the social life of 54.8% of participants. 16 They also found that hair loss influenced chosen hairstyle in 87.1% of participants. 16 The DLQI scores in these patients were 4 (+/−3.5). 16 Patient satisfaction and quality of life scores in this study were not associated with age or severity of hair loss. 16

A recent meta‐analysis performed by huang et al. (2021) confirmed the over‐arching theme that there is a significant association between androgenetic alopecia and a moderate impairment of health‐related quality of life and emotions. 17

4. DISCUSSION

These studies reveal that many of those affected by androgenetic alopecia suffer from feelings of anxiousness, helplessness, and diminished self‐esteem. Many patients are considerably preoccupied by the fear of progressive hair loss and their peers noticing. This psychosocial stress often gives rise to behavioral coping efforts. Patients’ dissatisfaction with their hair leads to overall body image dissatisfaction and a concomitant decline in quality of life. The psychosocial impact seems to be more severe in females when compared to males on average; however, males are significantly affected as well. More 25% of males with androgenetic alopecia find the hair loss to be extremely upsetting and 65% express modest to moderate emotional distress. 5 Across studies, single marital status, young age, and desire for medical intervention are associated with a greater risk of psychological morbidity. According to Cash et al.’s study comparing females with androgenetic alopecia to female controls, 70% of females suffering from hair loss report being very upset to extremely upset about it. 6 The females suffering from hair loss also reported a lower self‐esteem and quality of life than the control group. 6 Another study that involved interviewing females with hair loss found that 88% of them felt their hair loss negatively influenced their day‐to‐day lives. 7

A long‐term multinational study assessing the efficacy of finasteride in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia found that finasteride‐treated men rated their hair growth and satisfaction with their appearance more positively than placebo‐treated men. 18 This is further evidence that androgenetic alopecia warrants intervention and even modest improvement in hair loss leads to improved psychosocial outcomes. 13 , 16 Explaining realistic treatment outcomes to patients and managing their expectations is extremely important. Unrealistic expectations may lead to worse psychological outcomes and premature treatment discontinuation.

Clinical assessment of androgenetic alopecia does not necessarily correlate with a patient's perception of their hair loss or the psychological impact of the condition. This must be considered when formulating treatment plans and giving patients realistic treatment outcome expectations. A multidisciplinary treatment approach is often warranted when treating medical conditions with secondary psychosocial morbidity. Given the fact that many hair loss patients report dissatisfaction with their medical care, physicians ought to make a special effort to spend enough time with these patients. Time should be spent discussing potential therapies, realistic treatment outcomes, and the patient's coping strategies. A psychotherapy referral should be considered in those who present with any level of psychological distress. Given the knowledge that stress exacerbates hair loss, it is important to encourage the implementation of stress‐coping strategies and psychotherapy when warranted.

5. LIMITATIONS

Specific study limitations include small sample sizes, international variations in reporting, bias due to a lack of standardization when evaluating patients, lack of diversity among participants, and loss of patients to follow‐up. Some studies are also plagued by inclusion bias because their only participants are either actively seeking treatment or participating in support groups and therefore are more likely to have severe disease or severe emotional distress secondary to their disease. Patients with androgenetic alopecia who do not seek medical care would serve as ideal control group members. Each study varies in relation to design, quality, objective measures, and purpose of assessment which makes it difficult to draw concrete statistical conclusions based on this review.

6. CONCLUSION

Clinicians must be aware of the psychological impact of androgenetic alopecia, especially given the limited efficacy of current treatment options. In a culture that highly values physical appearance, many patients need psychological support to overcome the effects of their condition. This review highlights the prevalence of androgenetic alopecia and the transcendence of its detrimental psychological impact across time and place. The uncertain course of androgenetic alopecia, as opposed to many other forms of hair loss, adds to the stress of this condition. Further research is needed to determine how to properly address the psychological morbidity associated with this condition. When a patient seeks treatment for androgenetic alopecia, they are often, albeit unknowingly, seeking treatment for more than just hair loss. Psychodermatology liaison services and multidisciplinary clinics can fulfill a key need here. Clinics containing a conglomerate of dermatologists, psychiatrists, and/or psychologists can provide high‐quality integrative patient care to those suffering from psychocutaneous conditions. Androgenetic alopecia warrants such multidisciplinary involvement.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This review did not require an ethics board review or consent of any human subjects.

Aukerman EL, Jafferany M. The psychological consequences of androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:89–95. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14983

Funding information

None

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Androgenetic alopecia. G Ital Dermatol Venerol. 2014;149(1):15‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kranz D, Nadarevic L, Erdfelder E. Bald and Bad? Exp Psychol. 2019;66(5):331‐345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2001;15(2):137‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cartwright T, Endean N, Porter A. Illness perceptions, coping and quality of life in patients with alopecia. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2009;160(5):1034‐1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cash TF. The psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia in men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:926‐931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, Knegt‐Junk Kj, Nieboer C. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camacho FM, García‐Hernández M. Psychological features of androgenetic alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2002;16(5):476‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hongbo Y, Thomas C, Harrison M, Sam Salek M, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, Strauss BM, Elsner P. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(5):1038‐1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee HJ, Ha SJ, Kim D, Kim HO, Kim JW. Perception of men with androgenetic alopecia by women and nonbalding men in Korea: how the nonbald regard the bald. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(12):867‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kranz D. Young men's coping with androgenetic alopecia: acceptance counts when hair gets thinner. Body Image. 2011;8(4):343‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhuang X, Zheng Y, Xu J, Fan WX. Quality of life in women with female pattern hair loss and the impact of topical minoxidil treatment on quality of life in these patients. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(2):542‐546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta S, Goyal I, Mahendra A. Quality of life assessment in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2019;11(4):147‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Titeca G, Goudetsidis L, Francq B, et al. The psychological burden of alopecia areata and androgenetica: a cross sectional multicentre study among dermatological out‐patients in 13 European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2020;34(2):406‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zac RI, da Costa A. Patient satisfaction and quality of life among adult women with androgenetic alopecia using 5% topical minoxidil. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(5):26‐30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang C, Fu Y, Chi C. Health‐related quality of life, depression, and self‐esteem in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):963‐970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Study Group . Long‐term (5‐year) multinational experience with finasteride 1 mg in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:38‐49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.