Abstract

Diaphorina citri is an important vector of Citrus Huanglongbing (HLB) disease. After feeding on young host plant shoots, the population of D. citri can increase significantly. Females also only lay eggs on young shoots. However, there are few studies on the mechanism of this phenomenon. Exogenous nutrient signals can affect the insulin signaling system of D. citri after feeding on young shoots. In this study, the expression of upstream factors DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR in the insulin signaling system of D. citri was upregulated after feeding on young shoots. After being silenced by RNA interference technology, the results showed that the number of oviposited eggs of D. citri was significantly decreased and the ovarian development was inhibited with severe vacuolation. In addition, detection using quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction showed that the upstream regulatory gene DcRheb of the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway and the downstream reproduction‐related DcVg gene were also significantly downregulated. These results suggest that feeding upon young shoots may upregulate the expression levels of upstream factors DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR in the insulin signaling system. The signal will be through upregulating the expression of DcRheb, an upstream gene of the TOR signaling pathway. This in turn influences yolk metabolism, which eventually causes the ovaries of female D. citri to mature and therefore initiate oviposition behavior.

Keywords: Diaphorina citri, insulin‐like peptide, insulin receptor, insulin signaling, reproduction, target of rapamycin

After female D. Diaphorina citri feed on young shoots, DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR in the insulin signaling system are upregulated. Interfering with these three genes reduces the expression level of DcRheb in the target of rapamycin signaling system and the reproduction‐related gene DcVg. This results in varying degrees of stunted ovarian development and a significant decrease in oviposition.

Introduction

Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri) is an important homopteran pest impacting the global citrus industry (Tsai et al., 2009; Ruan et al., 2012). D. citri transmits the devastating citrus disease, Huanglongbing (HLB), which can lead to plant growth retardation and fruit quality degradation that eventually leads to a serious reduction in economic value. D. citri can acquire the pathogenic bacteria of HLB, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas), from infected plants quickly and effectively in its nymphal stages. The resulting D. citri adults then disperse and carry the bacteria to new healthy plants through feeding on them. This can lead to widespread distribution of HLB in the field (George et al., 2018). In addition, the honeydew secreted by the nymphs of D. citri can cause a sooty blotch and so block photosynthesis of the host plant; seriously harming the growth of the citrus crop. At present, no effective bactericides have been found to eliminate HLB, so controlling the vector insect D. citri is currently at the core of management programs for HLB.

The insulin and insulin‐like growth factor signaling (IIS) pathway is a conserved signaling pathway found in both vertebrates and invertebrates. This pathway can sense nutritional status and transmit signals through cascades to affect development, metabolism, longevity, and reproduction of the animal. In the IIS pathway, insulin and the insulin receptor (IR), as upstream factors, play an important role in sensing and transmitting nutritional signals. Insect insulin‐like peptides (ILPs) were first isolated from a Bombyx mori brain (Wu & Brown, 2006). To date, ILPs have been found in many different insect species with many different functions (Veenstra, 2020). ILPs are upstream factors of the insulin signaling pathway. Molecular studies over the past few decades have shown that ILPs can sense nutritional status through conserved insulin signaling pathways (Wu & Brown, 2006). As an organ related to insect nutrition, the brain of insects also has many insulin‐producing cells secreting ILP. This secretion is regulated by signals produced by the fat body, another key organ regulating nutrient metabolism, similar to the mammalian liver (Delanoue et al., 2016). Another important component of the IIS is the IR. This is a transmembrane receptor that triggers the IIS signal transduction cascade and transmits the signal downward after insulin binding (Wei et al., 1995; Hubbard, 1997). The IIS regulates various physiological processes such as development, longevity, metabolism, diapause, and female reproduction (Garofalo, 2002). The effect of IIS on reproduction has also been widely studied in various insects, for example, injection of bovine insulin into female adults of Tribolium castaneum lacking juvenile hormone (JH) can increase the vitellogenin protein (VG) which is essential for egg maturation and postoviposition embryo development (Wyatt & Davey, 1996; Sheng et al., 2011). Furthermore, it has been found that the development of the ovaries of homozygous female D. Drosophila melanogaster with dinrE19 mutations is inhibited during the pre‐embryonic stage (Brogiolo et al., 2001).

Insect reproduction is known to be affected by two endocrine hormones, JH and 20‐ecdysone (20E) (Bellés & Maestro, 2005). 20E is crucial for vitellogenesis in some hymenopteran, lepidopteran, and dipteran insects, and plays a major role in reproductive processes of mosquitoes and flies; 20E was found to stimulate the expression of VG and oocyte maturation in Aedes aegypti (Raikhel et al., 2002), and was also found to be involved in ovarian growth and oocyte maturation in T. castaneum (Parthasarathy et al., 2010). JH also plays a crucial role in the uptake of VG from the ovaries of many insects. In adult female Pyrrhocoris apterus, methoprene‐tolerant (Met) is a receptor protein of JH. Deficiency of this receptor severely inhibits the transcription of VG resulting in the VG receptor disrupting the uptake of vitelloprotein into oocytes; this ultimately leads to reduced reproductive capacity (Smykal et al., 2014). IIS can intervene in insect reproduction by influencing the content of JH and 20E; these two endocrine pathways being closely related. Female D. melanogaster with DmIR mutation had impaired ovarian development in the previtellogenesis stage, but treatment with methoprene, a JH analogue, restored vitellogenesis (Tatar et al., 2001). In addition, compared with the wild type, the ovaries of D. melanogaster with the DmIR mutation produced less ecdysone (Tu et al., 2002).

In the process of plant development, nitrogen, potassium, and other elements will be transferred from old tissues to new tissues to synthesize characteristic substances in flush shoots and other new tissues. These substances will be ingested by female D. citri, so changing their nutritional status after feeding on flush shoots (Sétamou et al., 2016) and inducing them to lay eggs. Our previous research demonstrated that the expression levels of JH‐ and 20E‐related genes and VG increase after D. citri has fed on flush shoots (Guo et al., 2021). The DcRheb (Ras‐homologue enriched in brain), DcRaptor (regulatory associated protein of mTOR), DcSin1 (target of rapamycin [TOR] complex 2 subunit MAPKAP1), and DcS6K (TOR complex 2 subunit MAPKAP1) genes in the TOR signaling pathway are also all upregulated after mated D. citri females have fed on flush shoots (Guo et al., 2021). We also previously determined that the synthesis and effect of JH and 20E are closely related to the TOR pathway. The expression of JH‐ and 20E‐related genes was significantly inhibited by interference treatment of DcRheb, a key factor in the TOR pathway. These results suggested that feeding on flush shoots induces oviposition in female D. citri and is realized by the TOR signaling pathway affecting JH and 20E (Guo et al., 2021). However, its upstream pathway has not been fully studied.

The current study therefore investigates the pathways that transmit nutritional signals and seeks to link them to reproduction. Combined with the relationship between the insulin signaling pathway and insect nutrition status as described above, we considered whether the insulin signaling pathway is also involved in reproductive regulation upstream of TOR.

Materials and methods

Insects

The D. citri used in this study was collected on shrubs of Murraya paniculata near South China Agricultural University (SCAU), Guangzhou, China, and subcultured in the laboratory of the Engineering Research Center for Biological Control, Ministry of Education, SCAU. The culturing method was to simply allow the D. citri to feed on the host plant M. paniculata covered in a white nylon net bag in an incubator at 26 °C, 14 h light and 10 h dark photoperiod, and 60% ± 2% relative humidity (Guo et al., 2021).

Identification of DcILP1, DcILP2, DcIR, and phylogenetic tree construction

For the sake of description, we named the gene XP_008468126 as DcILP1, AWT50608.1 as DcILP2, and XP_008479213 as DcIR. The prepropeptide of DmILPs and DmIR was identified (Brogiolo et al., 2001) and aligned with DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR using the clustalx multiple sequence alignment program. A total of 26 ILP amino acid sequences from 16 species and 40 IR from 22 species were used for alignment and phylogenetic tree construction. The prediction of the signal peptide (SP) of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR was made by signalp 4.0. The sequences of the species investigated are listed in the Supporting Information Table S1. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGAX software according to the maximum likelihood method and the bootstrap value was set as 1000. Three‐dimensional models of DmIR and DcIR were constructed and analyzed using SWISS‐MODEL.

Expression patterns of insulin key genes DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR in Diaphorina citri feeding host

Pairings were made according to the ratio of 1 : 2 male to female and placed on mature leaves (20 d after budding) for 7 d. They were then transferred to an environment where only either flush shoots (within a week after budding) or mature leaves were available (Fig. 1). Female D. citri were collected at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d after each treatment. Each treatment had three replicates and each replicate had 30 D. citri. RNA was extracted from frozen worms using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. , Waltham, MA, USA) with agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was used to determine quality and concentration. The cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of the above RNA samples according to the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with GDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TAKARA, Beijing, China). primer 5 software was used to design quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR) specific primers for DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes; DcActin gene was used as the internal reference gene (Supporting Information Table S2). The fluorescent dye TB Green Premixture Ex Taq II (TAKARA) was used to detect the expression of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes at different time intervals within female adults of D. citri. Relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001).

Fig. 1.

Pictures of flush shoots and mature leaves influencing the reproduction of Diaphorina citri. (A) Flush shoots within a week after budding can induce the reproduction of D. citri; (B) mature leaves 20 d after budding cannot induce the reproduction of D. citri.

RNA interference effect of dsRNA on the number of oviposited eggs and ovarian morphology

The dsRNA‐specific primers of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR were designed using primer 5 software (Supporting Information Table S2). The cDNA of the whole D. citri was used as a template. The plasmid of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used as the template for the control group (also shown in Supporting Information Table S2). The PCR conditions were 94 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final step of 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR product was purified by use of a DNA purification kit (Tiagen, Beijing, China). dsRNA was synthesized by the Hiscribe™ T7 in Vitreo Transcription Kit (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA).

The D. citri were paired according to the ratio of male to female 1 : 2. There were 30 female insects in total. The D. citri were placed on mature leaves for 7 d, following which the females were collected for RNA interference (RNAi). The RNAi was performed by diluting dsRNA to 800 ng/μL with RNase‐free water, placing the mated female on ice for a few minutes to cause it to pass out, and then using a 10‐μL Hamilton syringe to locally drop 1 μL dsRNA to the ventral chest between the three pairs of legs. The control was administered with dsEGFP. After being treated with dsRNA, the females of each group were placed on individual shoots and separated by a white nylon net bag. Five biological replicates with 30 females in each replicate were collected on the 1st and 5th days after being placed on the shoots. Total RNA of all samples was extracted and reverse‐transcribed into cDNA, and the silencing efficiency of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes after RNAi was detected by RT‐qPCR.

Female D. citri mated for 7 d on mature leaves after delivering dsRNA were moved to individual flush shoots, again separated by a white nylon net bag, and moved to new leaves every 3 d to lay eggs. Then, the leaves that had eggs laid on them were cut off, and the number of eggs was counted under a microscope. On day 5 after RNAi, 15 females were randomly selected to dissect their reproductive systems. Photographs were taken with a microscope (Stemi 305, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using color photography (Axioca 506, Zeiss) using a phosphate‐buffered saline anatomical buffer under a positive fluorescence biological microscope.

Effects of dsRNA on the expression of TOR signal and reproduction‐related genes

On both day 1 and day 5 after RNAi, 30 females were collected as a replicate, and five biological replicates were collected at each time‐point. Total RNA of all samples was extracted and reverse‐transcribed into cDNA. The RT‐qPCR was used to detect the expression levels of DcRheb, a key gene in the TOR pathway, and DcVg with DcActin gene as an internal reference gene after RNAi (Guo et al., 2021).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Gene expression and number of oviposited eggs data were analyzed using Student's t test between treatments for mean separation, P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic comparison

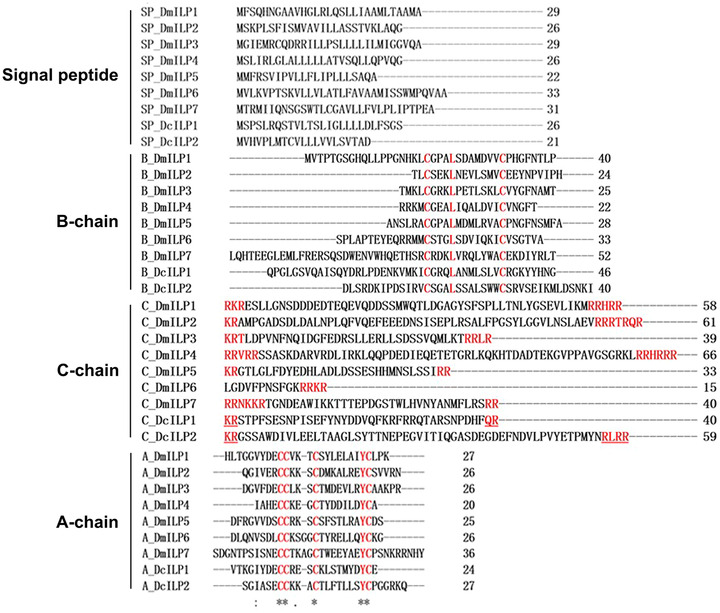

We selected two ILPs that responded to flush shoot feeding and compared the protein sequences of DcILP1 and DcILP2 with DmILP1‐7 of D. melanogaster (Fig. 2). The open reading frames of DcILP1 and DcILP2 were 411 and 444 bp, encoding 136 and 147 amino acids, respectively. Prepropeptides of DcILP1 and DcILP2 also existed of four conserved regions, namely SP, B‐chain, C‐peptide, and A‐chain. We predicted that the SP region of DcILP1 was located at amino acids 1–26 starting from the N‐terminus, and that the SP region of DcILP2 was located at amino acids 1–21. SP is followed by B‐chain; the B‐chains of DcILP1 and DcILP2 have two conserved cysteines (Cys) separated by 11 other amino acids, and in the fourth position of these 11 amino acids is leucine (Leu), which is highly consistent with D. melanogaster. C‐peptide is located behind the B‐chain, and dibasic proteolytic cleavage sites represented by KR, KK, and RR usually exist at the beginning and end. Such sites were also found in DcILP1 and DcILP2. In the A‐chain, DcILP1 and DcILP2 both have four Cys and the amino acid before the fourth Cys is tyrosine (TyR), which is a fairly conservative motif and again highly consistent with D. melanogaster. Furthermore, the second and third Cys are separated by three amino acids in the A‐chains of DcILP1 and DcILP2. This is also consistent with ILP1‐5 in D. melanogaster.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of amino acid sequences between Drosophila melanogaster ILP1‐7, DcILP1, and DcILP2.

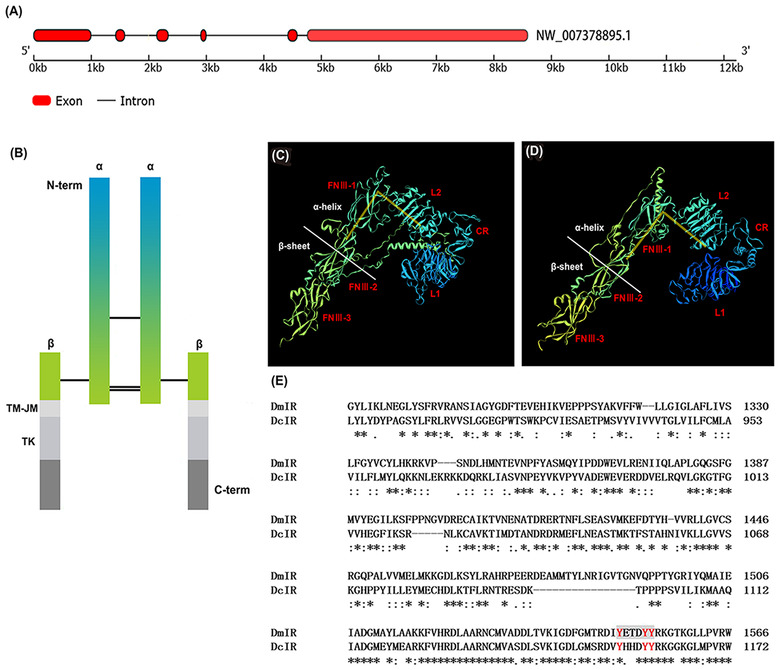

The open reading frame of DcIR was 4 023 bp in length and encoded 1 340 amino acids. It contained five introns (Fig. 3A) and belonged to cluster II according to Smykal's classification method (Smykal et al., 2020). The schematic diagram of DcIR is shown in Fig. 3(B), and when comparing the tertiary structure of the extracellular domain predicted by DcIR (Fig. 3C) with that of D. melanogaster (Fig. 3D), both can be divided into α‐chains rich in α‐helices and β‐chains rich in β‐folds containing many of the same domains. Within this, L1 and L2 represent ligand‐binding loops 1 and 2, CR indicates a cysteine‐rich region, and FNIII‐1, FNIII‐2, and FNIII‐3 represent the three fibronectin type III domains. In addition, they can both form a similar “V” structure (marked in yellow in Fig. 3C, D). We also compared the amino acid sequences of the intracellular domains of DcIR and DmIR. Here, we found that the active region, namely the tyrosine kinase domain of DcIR and DmIR, was highly consistent, and both had the conserved sequence “motif” (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Structure and amino acid sequence analysis of DcIR. Three‐dimensional models and comparison of amino acid sequences between DmIR and DcIR. (A) Introns of DcIR sequence; (B) schematic diagram of DcIR; (C) tertiary structure of the extracellular domain predicted by DcIR; (D) tertiary structure of the extracellular domain predicted by DmIR; and (E) comparison of amino acid sequences of intracellular domains between DmIR and DcIR. Red letters indicate the active region of tyrosine kinase.

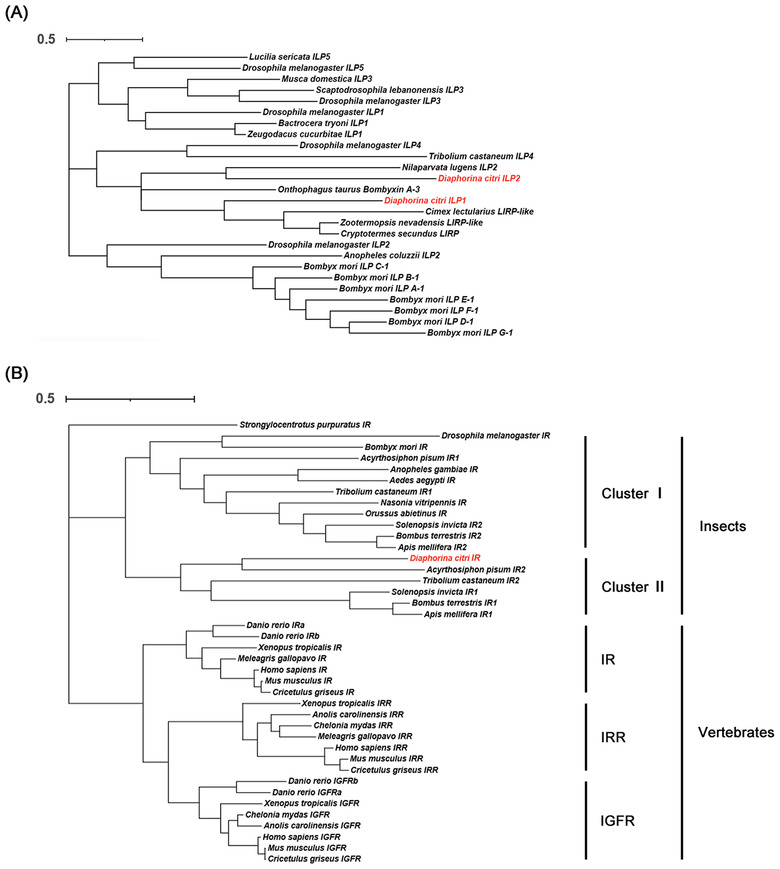

In order to understand the evolutionary relationship between ILP and IR in vertebrates and invertebrates, phylogenetic trees of ILP and IR were constructed. We analyzed 27 ILP amino acid sequences from 16 species and 41 IR from 22 species, these species included vertebrates and invertebrates. For ILPs, insulin‐signaling ligands in vertebrates can be classified into insulin and insulin like growth factor (IGF), which have different functions. Various types of ILPs usually exist in insects. We compared the ILPs of several different insects against DcILPs. The results showed that DcILP1 is clustered with a variety of insect Locusta insulin‐related peptides (LIRP) and it has high homology with LIRP of Cimex lectularius, Zootermopsis nevadensis, and Cryptotermes secundus. DcILP2 has high homology with ILP2 in Nilaparvata lugens (Fig. 4A). IR were found in both vertebrates and invertebrates, indicating that ILP and IR can be traced back to at least before the differentiation of vertebrates and invertebrates, and play an important role in some basic physiological activities of organisms. IRs in vertebrates can be divided into IRs, IRRs, and IGFRs groups. Most insects contain only one kind of IR. According to Smykal's classification criteria, cluster I includes the IR1 of T. castaneum and the IR of D. melanogaster, and cluster II includes IR2 of T. castaneum, IR2 of Acyrthosiphon pisum, and DcIR (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the insulin like peptides and insulin receptors. (A) Insulin‐like peptides; (B) insulin receptors.

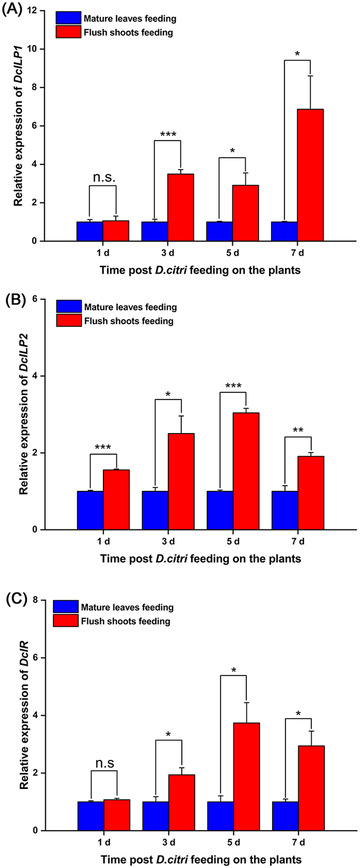

Expression patterns of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes

In order to study the expression of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR at different times, the mated females of D. citri at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d after feeding on either flush shoots or mature leaves were collected for RNA extraction. The RT‐qPCR results showed that the expression levels of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR generally increased when flush shoots were eaten compared with the mature leaves. For DcILP1, the expression levels were not significantly different between the two groups at 1 d. However, they were significantly different at 3, 5, and 7 d. The expression levels of DcILP1 fed on flush shoots were 3.49, 2.91, and 6.87 times higher than those fed on mature leaves at 3, 5, and 7 d, respectively (Fig. 5A). The expression levels of DcILP2 were all significantly different between the two groups at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d after feeding. The expression levels in the group fed on flush shoots were 1.56, 2.50, 3.04, and 1.91 times higher than those groups fed on mature leaves at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d, respectively (Fig. 5B). For DcIR, the expression levels were not significantly different between the two groups at 1 d but were significantly different at 3, 5, and 7 d. The expression levels of DcIR fed on flush shoots were 1.94, 3.74, and 2.94 times higher than those fed on mature leaves at 3, 5, and 7 d, respectively (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Expression profiles of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR after feeding on flush shoots and mature leaves. (A) Expression profiles of DcILP1; (B) expression profiles of DcILP2; and (C) expression profiles of DcIR. Values represent means ± SE. Gene expression data were analyzed using Student's t‐ test. The asterisks denote statistically significant differences compared with control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). n.s. denotes no statistically significant difference compared with control.

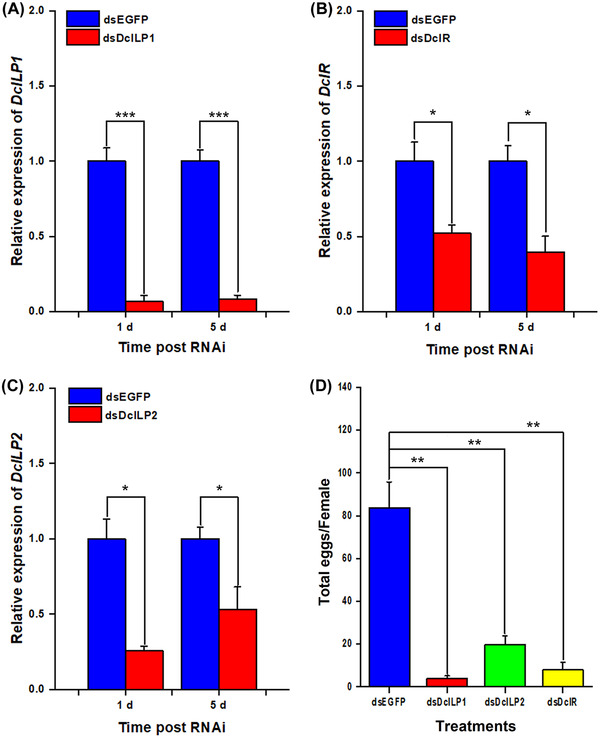

DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes RNAi and reproduction

In order to study the effect of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR, the key genes of the insulin pathway, on the fertility of D. citri, DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR were suppressed using dsRNA. From day 1 after treatment with dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR, RT‐qPCR results showed that the expression levels of DcILP1 were decreased by 14.62 and 11.92 times (Fig. 6A); DcILP2 was decreased by 3.89 and 1.88 times (Fig. 6B); and DcIR was decreased by 1.91 and 2.52 times, compared with the control group (Fig. 6C). In addition, female D. citri were introduced onto flush shoots for feeding after RNAi. Here, the number of eggs in the control group injected with dsEGFP was 83.75 ± 12.09 per female, but in those injected with DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR RNAi the insect reproductive ability was almost destroyed with only 4.05 ± 1.11, 19.70 ± 4.20, and 8.00 ± 3.50 eggs per female, respectively (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of fecundity and relative gene expression of Diaphorina citri after dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR treatment. (A) DcILP1 RNAi efficiency after dsDcILP1 and dsGFP treatment; (B) DcILP2 RNAi efficiency after dsDcILP2 and dsGFP treatment; (C) dsDcIR RNAi efficiency after dsDcILP1 and dsGFP treatment; and (D) fecundity of mated female D. citri. Values represent means ± SE. Gene expression data and number of oviposited eggs were analyzed using Student's t‐ test. The asterisks denote statistically significant differences compared with control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). n.s. denotes no statistically significant difference compared with control.

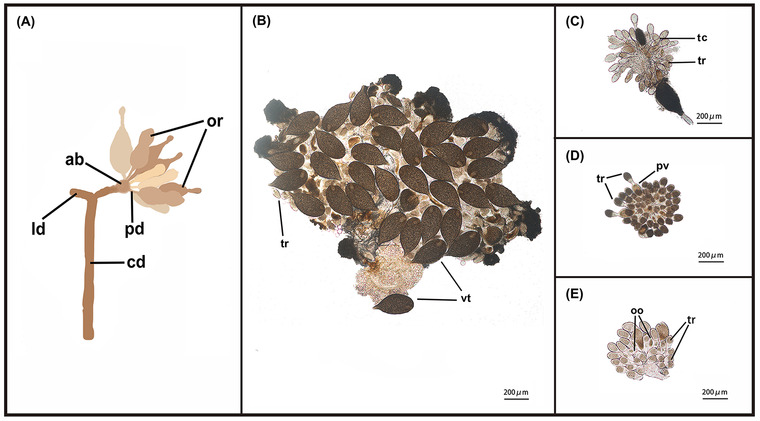

Effect of silencing DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR on ovarian morphology of D. citri

The ovaries of D. citri are inserted into the apical bulb by a pedicel and connected to the common oviduct through the lateral oviduct (Fig. 7A) (Dossi & Consoli, 2014). We examined ovary development after different treatments. After the mated female adults were introduced onto the flush shoots for 5 d, the ovaries in the control group that were injected with dsEGFP became fully developed. Vitellogenic stage oocytes could also be observed; the obvious characteristics of oocytes in this stage are large and plump (Fig. 7B). However, ovarian development was impaired to varying degrees in the dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR groups. For dsDcILP1, 5 d after RNAi, most oocytes were still at the previtellogenic stage, we could observe a large number of trophariums and fewer growing oocytes (Fig. 7C); for dsDcILP2, although there were no vitellogenic stage oocytes, more trophariums could be observed and more previtellogenic stage oocytes were clearly observed compared with dsDcILP1 treatment (Fig. 7D). Five days after dsDcIR treatment, the development of ovarioles was still inhibited compared with that of the control group; there were no vitellogenic stage oocytes but we could observe growing oocytes (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of partial structure of Diaphorina citri ovary and ovarian morphology changes after 5 d following treatment of dsEGFP, dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR. (A) Schematic diagram of partial structure of D. citri ovary; (B) ovarian morphology 5 d after dsEGFP treatment; (C) ovarian morphology 5 d after dsDcILP1 treatment; (D) ovarian morphology 5 d after dsDcILP2 treatment; and (E) ovarian morphology 5 d after dsIR treatment. ab, apical bulb; cd, common oviduct; ld, lateral oviduct; oo, growing oocyte; or, ovarioles; pd, pedicel; pv, previtellogenic stage oocytes; tc, trophic chord; tr, tropharium; vt, vitellogenic stage oocytes.

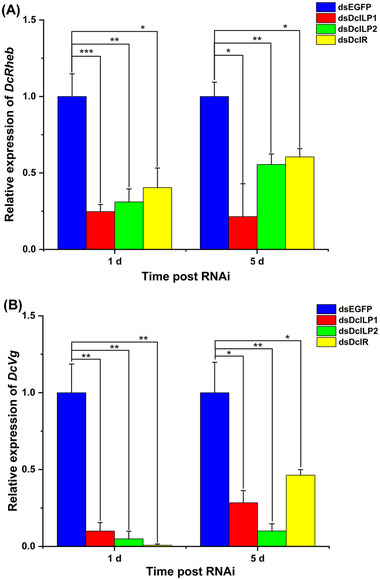

Effect of silencing DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR on TOR signal and reproduction‐related genes

To determine whether the insulin signaling pathway plays an important role in the reproduction of D. citri, DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR were suppressed using dsRNA. Expression of DcRheb and DcVg was analyzed at 1 and 5 d after DcRheb RNAi treatment, at which time both genes were significantly downregulated. The expression level of DcRheb decreased to 24.73% and 21.46% on the 1st and 5th days after dsDcILP1 treatment, and then following dsDcILP2 treatment reduced to 31.06% and 55.54% on the days 1 and 5, respectively. After dsDcIR treatment it reduced to 40.41% and 60.49% on days 1 and 5, respectively (Fig. 8A). The expression of DcVg decreased to 10.02% and 28.41% on days 1 and 5 after dsDcILP1 treatment. Following dsDcILP2 treatment, it decreased to 4.95% and 10.05% on days 1 and 5, and after dsDcIR treatment, it decreased to 0.81% and 46.36% on days 1 and 5, respectively (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

The expression levels of DcRheb and DcVg after dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR treatment. (A) DcRheb expression of female D. citri after dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR treatment for 1 and 5 d; (B) DcVg expression of female D. citri after dsDcILP1, dsDcILP2, and dsDcIR treatment for 1 and 5 d. Values represent means ± SE. The asterisks denote statistically significant difference compared with control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). n.s. denotes no statistically significant difference compared with control.

Discussion

It has been confirmed by this study that after mated female D. citri feed on flush shoots, the substances within the flush shoots are taken in and form a kind of nutritional signal to activate the insulin signaling pathway. Following this, the nutritional signal is transmitted to the TOR signaling pathway, which induces oviposition behavior in D. citri.

Insulin, IGF and ILPs as IIS signal ligands exist widely in vertebrates and invertebrates. These signaling molecules play important roles in different developmental stages and tissues of organisms. The human insulin signaling system is complex and well documented. Humans have not only insulin and IGF, but also relaxin and human ILPs (INSL3‐7; INSL3‐7) (Hudson et al., 1983; Froesch & Zapf, 1985; Chassin et al., 1995; Watanabe et al., 2011; Lok et al., 2012). Insulin and ILPs have also been found in a large number of invertebrates, such as nematodes and insects. There are multiple types of ILPs in most insects, and the number of ILPs varies from 1 to 38. The secretion and function of ILPs in insects are usually related to nutrition. By analyzing conserved sequences, seven DmILPs with different functions were found in D. melanogaster. Among them, DmILP2 regulates cell size and number to affect the size of the organism. Neurosecretory cells (insulin‐producing cells) can autonomously sense circulating glucose and secrete ILP2, ILP3, and ILP5, regulated by factors released by intestinal adipocytes (Nässel & Broeck, 2015). DmILP6 is structurally and functionally similar to IGF in vertebrates (Okamoto et al., 2009; Slaidina et al., 2009), while DmILP7 is similar to relaxin (Miguel‐Aliaga et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). DcILPs were composed of SP, B‐chain, C‐peptide, and A‐chain sequentially, which were compared with DmILPs. Many amino acid motifs were consistently conserved in them. These indicated that ILPs of D. citri may have some similar functions to those in D. melanogaster described above. As a downstream molecule of ILP, IR is a transmembrane protein that exists on the cell membrane and can receive signals transmitted by different ILPs and then transmits them downward. It has been confirmed in D. melanogaster that IR plays a key role in growth, body size, reproduction, and lifespan (Chen et al., 1996; Brogiolo et al., 2001; Wu & Brown, 2006). This study also analyzed DcIR and found that the protein sequence structure of DcIR was similar to that of D. melanogaster, including not only α‐ and β‐chains, but also the inverted “V” structure, indicating that DmIR is likely to play a similar role to D. Drosophila IR.

The IIS has been found to affect reproduction in a variety of insects. Studies on silkworm have shown that the body weight, ovary weight, and egg number of iGfLp knockout female silkworm were significantly lower than that of the wild‐type of silkworm (Fujinaga et al., 2019). Studies on the role of INR genes in the fertility of N. lugens have shown that the combined injection of dsINR1 and dsINR2 (dsINRS) simultaneously silences the expression of NlINR1 and NlINR2 genes, which can reduce the number of eggs laid by N. lugens (Liu et al., 2020). In our study, DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR genes were silenced. The results showed that the number of spawn decreased significantly and ovarian development was also inhibited. These results suggest that the insulin signaling system plays an important role in the development of the oocytes and indirectly affects their oviposition mechanism, which is also consistent with the above results of silkworm and N. lugens.

To make the conclusion more convincing, in addition to the above macrocharacteristics, we also performed further analysis using RT‐qPCR technology. The VG, a precursor of vitelloprotein, is the main source of nutrients for insect reproduction and embryonic development (Saucedo et al., 2003), and is involved in terminal follicular growth, follicular epithelial differentiation, oocyte development, and other reproductive processes (Stocker et al., 2003). We found that the expression level of DcVG decreased significantly on the 1st and 5th day after DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR interference. This indicated that these three genes could significantly affect the reproduction of D. citri and were located upstream of DcVg.

Early studies on the population changes of D. citri showed that the population number was positively correlated with the number of flush shoots of the plant and the continuous generation of flush shoots could ensure the high growth rate of the D. citri population (Tsai et al., 2009). Consistent with the change of population size, the initiation and duration of oviposition behavior of D. citri was also closely related to the flush shoots of host plants. It has been found that female D. citri tend to choose flush shoots less than 6 mm in length on which to lay eggs, and the maturation of the ovary in female D. citri is also closely related to the existence of plant buds (Cifuentes‐Arenas et al., 2018).

As it has been established with D. citri that spawning occurs only after feeding on flush shoots, we speculated that the insulin signaling pathway, as an important signaling pathway for sensing nutritional status, will be activated after the female D. citri feeds on the flush shoots. This is due to some specific substances in the flush shoots. Consistent with this speculation, our results demonstrated that the expression levels of DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR were significantly higher in the group fed on flush shoots on the 3rd, 5th, and 7th days after feeding than in the control group, respectively.

After sensing various nutritional signals, as an upstream signaling factor of the insulin signaling pathway, ILPs can bind to the IR (Chen et al., 1996), recruit substrate Chico (Bohni et al., 1999), and activate phosphoinositol‐3‐kinase (Weinkove et al., 1999). Phosphoinositol‐3‐kinase phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐diphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5‐triphosphate (PIP3). The resulting increased PIP3 can activate Akt (serine/threonine kinase) which then activates other downstream signaling pathways, which then transmit signals (Hansen et al., 2014). The TOR signaling pathway is connected with the insulin signaling pathway. Both of these pathways are nutrient‐sensitive pathways that regulate growth rate (Oldham et al., 2000; Brogiolo et al., 2001; Britton et al., 2002; Ikeya et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2002; Oldham & Hafen, 2003), so it is usually together called the insulin/TOR signaling pathway (Smykal & Raikhel, 2015). In addition, activated Akt has been identified as a key molecule linking the IIS and TOR pathways. It can inhibit the negative regulatory factors of TOR, thus achieving the positive regulatory effect on TOR. A study of female A. aegypti found that blood intake causes the neuroendocrine cells of A. aegypti to release ILP3, which then activates the IIS and TOR pathways by phosphorylating Akt, and inactivates glycogen synthase kinase 3, a key factor in the yolk development of A. aegypti. These results indicate that IIS can be used as an upstream pathway to affect the downstream reproductive process through perception of nutrition, and it is likely to be transmitted through TOR signaling (Hansen et al., 2014). In our previous study, it was found that mated female D. citri produce oviposition only after feeding on flush shoots, and this process has been proved to be closely related to the TOR signaling pathway, and the effect of TOR on reproduction is realized by affecting the expression levels of 20E and JH, two hormones closely related to insect reproduction (Guo et al., 2021). Here in the current study, after silencing DcILP1, DcILP2, and DcIR, we detected the expression level of DcRheb, a key gene upstream of the TOR pathway, to decrease significantly, which indicates that nutrition signals from flush shoots are transmitted downward by the insulin signaling pathway through the TOR signaling pathway. Besides TOR signaling, ILP can also influence the reproductive process through fork head transcription (FOXO) (Sim & Denlinger, 2009). Therefore, insulin/FOXO signaling should also be considered in the reproduction regulation of D. citri in the future.

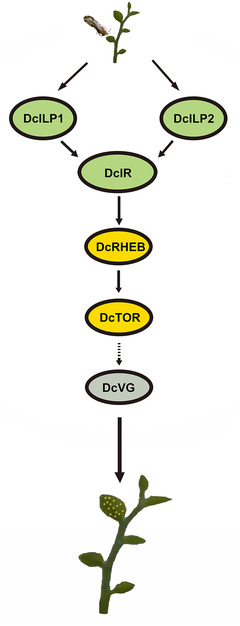

In conclusion, after the female D. citri feed on the flush shoots, the substances in the flush shoots are taken in and form a kind of nutritional signal to activate the insulin signaling pathway, and the resulting nutritional signal is transmitted to the TOR signaling pathway. An activated TOR pathway leads to an increase in VG expression to induce oviposition behavior in D. citri (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Schematic diagram of pathways related to spawning of Diaphorina citri induced by feeding on flush shoots.

Disclosure

All authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no conflict of interest, including specific financial interest and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject of manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 Species and accession numbers of ILPs and IRs used for constructing the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 4.

Table S2 Primers used in the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Guangdong Laboratory of Lingnan Modern Agriculture Project (NT2021003), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515011062), NSFC‐Guangdong Joint Research Fund (U1701231), the National High Level Talent Special Support Plan (2020), the Earmarked Fund for Guangdong Modern Agro‐Industry Technology Research System (2022KJ108), and Study on Control Technology of Huanglongbing (KY‐2017‐001).

Ziye Wang and Delong Tan are co‐first author.

Contributor Information

Baoli Qiu, Email: baileyqiu@scau.edu.cn.

Wen Sang, Email: sangwen@scau.edu.cn.

References

- Bellés, X. & Maestro, J.L. (2005) Endocrine peptides and insect reproduction. Invertebrate Reproduction and Development, 47, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bohni, R. , Riesgo‐Escovar, J. , Oldham, S. , Brogiolo, W. , Stocker, H. , Andruss, B.F. et al. (1999) Autonomous control of cell and organ size by CHICO, a D. Drosophila homolog of vertebrate IRS1‐4. Cell, 97, 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton, J.S. , Lockwood, W.K. , Li, L. , Cohen, S.M. & Edgar, B.A. (2002) D. Drosophila’s insulin/PI3‐kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Developmental Cell, 2, 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo, W. , Stocker, H. , Ikeya, T. , Rintelen, F. & Hafen, E. (2001) An evolutionarily conserved function of the D. Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin‐like peptides in growth control. Current Biology, 11, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin, D. , Laurent, A. , Janneau, J.L. , Berger, R. & Bellet, D. (1995) Cloning of a new member of the insulin gene superfamily (INSL4) expressed in human placenta. Genomics, 29, 465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. , Jack, J. & Garofalo, R.S. (1996) The D. Drosophila insulin receptor is required for normal growth. Endocrinology, 137, 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes‐Arenas, J.C. , Goes, A.D. , Miranda, M.P.D. , Beattie, G.A.C. & Lopes, S.A. (2018) Citrus flush shoot ontogeny modulates biotic potential of D. Diaphorina citri . PLoS ONE, 13, e0190563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoue, R. , Meschi, E. , Agrawal, N. , Mauri, A. , Tsatskis, Y. , Mcneill, H. et al. (2016) D. Drosophila insulin release is triggered by adipose stunted ligand to brain Methuselah receptor. Science, 353, 1553–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossi, F.C.A. & Consoli, F.L. (2014) Gross morphology and ultrastructure of the female reproductive system of D. Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae). Zoologia, 31, 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Froesch, E.R. & Zapf, J. (1985) Insulin‐like growth factors and insulin: comparative aspects. Diabetologia, 28, 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinaga, D. , Shiomi, K. , Yagi, Y. , Kataoka, H. & Mizoguchi, A. (2019) An insulin‐like growth factor‐like peptide promotes ovarian development in the silkmoth Bombyx mori . Scientific Reports, 9, 2045–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, R.S. (2002) Genetic analysis of insulin signaling in D. Drosophila . Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 13, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, J. , Ammar, E. , Hall, D.G. , Shatters, R.G. Jr & Lapointe, S.L. (2018) Prolonged phloem ingestion by D. Diaphorina citri nymphs compared to adults is correlated with increased acquisition of citrus greening pathogen. Scientific Reports, 8, 2045–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.H. , Liu, Y.M. , Wang, Z.Y. , Wang, F.F. , Mao, Y.K. , Hu, Y.W. et al. (2021) Transcriptome analysis reveals TOR signalling‐mediated plant flush shoots governing D. Diaphorina citri Kuwayama oviposition. Insect Molecular Biology, 30, 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, I.A. , Attardo, G.M. , Rodriguez, S.D. & Drakeet, L.L. (2014) Four‐way regulation of mosquito yolk protein precursor genes by juvenile hormone‐, ecdysone‐, nutrient‐, and insulin‐like peptide signaling pathways. Frontiers in Physiology, 5, 1664–042X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, S.R. (1997) Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog. EMBO Journal, 16, 5572–5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P. , Haley, J. , John, M. , Cronk, M. , Crawford, R. , Haralambidis, J. et al. (1983) Structure of a genomic clone encoding biologically active human relaxin. Nature, 301, 628–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya, T. , Galic, M. , Belawat, P. , Nairz, K. & Hafen, E. (2002) Nutrient‐dependent expression of insulin‐like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in D. Drosophila . Current Biology, 12, 1293–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H. , Sarbassov, D.D. , Ali, S.M. , King, J.E. , Latek, R.R. , Erdjument‐Bromage, H. et al. (2002) mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient‐sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell, 110, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.K. , Luo, Y.J. , Deng, Y.M. , Li, Y. & Tang, B. (2020) Insulin receptors regulate the fecundity of Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Journal of Asia‐Pacific Entomology, 23, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J. & Schmittgen, T. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the2−ΔΔCt method. Methods (San Diego, Calif.), 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok, S. , Johnston, D.S. , Conklin, D. , Lofton‐Day, C.E. , Adams, R.L. , Jelmberg, A.C. et al. (2012) Identification of INSL6, a new member of the insulin family that is expressed in the testis of the human and rat. Biology of Reproduction, 62, 1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel‐Aliaga, I. , Thor, S. & Gould, A.P. (2008) Postmitotic specification of D. Drosophila insulinergic neurons from pioneer neurons. PLoS Biology, 6, e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nässel, D.R. & Broeck, J.V. (2015) Insulin/IGF signaling in D. Drosophila and other insects: factors that regulate production, release and post‐release action of the insulin‐like peptides. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 73, 271–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, N. , Yamanaka, N. , Yagi, Y. , Nishida, Y. , Kataoka, H. , O'Connor, M.B. et al. (2009) A fat body‐derived IGF like peptide regulates post‐feeding growth in D. Drosophila . Developmental Cell, 17, 885–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, S. & Hafen, E. (2003) Insulin/IGF and target of rapamycin signaling: a TOR de force in growth control. Trends in Cell Biology, 13, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, S. , Montagne, J. , Radimerski, T. , Thomas, G. & Hafen, E. (2000) Genetic and biochemical characterization of dTOR, the D. Drosophila homolog of the target of rapamycin. Genes and Development, 14, 2689–2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, R. , Sheng, Z. , Sun, Z. & Palli, R.S. (2010) Ecdysteroid regulation of ovarian growth and oocyte maturation in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum . Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 40, 429–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikhel, A.S. , Kokoza, V.A. , Zhu, J. , Martin, D. , Wang, S.F. , Li, C. et al. (2002) Molecular biology of mosquito vitellogenesis: from basic studies to genetic engineering of antipathogen immunity. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 32, 1275–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, C.Q. , Chen, J. , Liu, B. , Duan, Y.P. & Xia, Y.L. (2012) Morphology and behavior of Asian citrus psyllid, D. Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 28, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo, L.J. , Gao, X. , Chiarelli, D.A. , Li, L. , Pan, D. & Edgar, B.A. (2003) Rheb promotes cell growth as a component of the insulin/TOR signaling network. Nature Cell Biology, 5, 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sétamou, M. , Simpson, C.R. , Alabi, O.J. , Nelson, S.D. , Telagamsetty, S. , Jifon, J.L. et al. (2016) Quality matters: influences of citrus flush physicochemical characteristics on population dynamics of the Asian citrus psyllid (Hemiptera: Liviidae). PLoS ONE, 11, e0168997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Z. , Xu, J. , Bai, H. , Zhu, F. & Palli, S.R. (2011) Juvenile hormone regulates vitellogenin gene expression through insulin‐like peptide signaling pathway in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum . Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286, 41924–41936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim, C. & Denlinger, D.L. (2009) Transcription profiling and regulation of fat metabolism genes in diapausing adults of the mosquito Culex pipiens . Physiological Genomics, 39, 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaidina, M. , Delanoue, R. , Gronke, S. , Partridge, L. & Léopold, P. (2009) A D. Drosophila insulin‐like peptide promotes growth during nonfeeding states. Developmental Cell, 17, 874–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smykal, V. & Raikhel, A.S. (2015) Nutritional control of insect reproduction. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 11, 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smykal, V. , Bajgar, A. , Provaznik, J. , Fexova, S. , Buricova, M. , Takaki, K. et al. (2014) Juvenile hormone signaling during reproduction and development of the linden bug, Pyrrhocoris apterus . Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 45, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smykal, V. , Pivarci, M. , Provaznik, J. , Bazalová, O. , Jedlička, P. , Luksan, O. et al. (2020) Complex evolution of insect insulin receptors and homologous decoy receptors, and functional significance of their multiplicity. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 1775–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, H. , Radimerski, T. , Schindelholz, B. , Wittwer, F. , Belawat, P. , Daram, P. et al. (2003) Rheb is an essential regulator of S6K in controlling cell growth in D. Drosophila . Nature Cell Biology, 5, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar, M. , Kopelman, A. , Epstein, D. , Tu, M.P. , Yin, C.M. & Garofalo, R.S. (2001) A mutant D. Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life‐span and impairs neuroendocrine function. Science, 292, 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.H. , Wang, J.J. & Liu, Y.H. (2009) Seasonal abundance of the Asian citrus psyllid, D. Diaphorina citri (Homoptera: Psyllidae) in Southern Florida. Florida Entomologist, 85, 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M.P. , Yin, C.M. & Tatar, M. (2002) Impaired ovarian ecdysone synthesis of D. Drosophila melanogaster insulin receptor mutants. Aging Cell, 1, 158–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra, J.A. (2020) Arthropod igf, relaxin and gonadulin, putative orthologs of D. Drosophila insulin‐like peptides 6, 7 and 8, likely originated from an ancient gene triplication. PeerJ, 8, e9534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y. , Miyamoto, Y. , Matsuda, T. & Tanaka, M. (2011) Relaxin‐3/INSL7 regulates the stress‐response system in the rat hypothalamus. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 43, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. , Hubbard, S.R. , Hendrickson, W.A. & Ellis, L. (1995) Expression, characterization, and crystallization of the catalytic core of the human insulin receptor protein‐tyrosine kinase domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270, 8122–8130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinkove, D. , Neufeld, T.P. , Twardzik, T. , Waterfield, D.M. & Leevers, J.S. (1999) Regulation of imaginal disc cell size, cell number and organ size by D. Drosophila class I(A) phosphoinositide 3‐kinase and its adaptor. Current Biology, 9, 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q. & Brown, M.R. (2006) Signaling and function of insulin like peptides in insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 51, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, G.R. & Davey, K.G. (1996) Cellular and molecular actions of juvenile hormone II. Roles of juvenile hormone in adult insects. Advances in Insect Physiology, 26, 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H. , Belawat, P. , Hafen, E. , Jan, L.Y. & Jan, Y.N. (2008) D. Drosophila egg‐laying site selection as a system to study simple decision‐making processes. Science, 319, 1679–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Species and accession numbers of ILPs and IRs used for constructing the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 4.

Table S2 Primers used in the study.