Abstract

Personalized experiences are more effective at creating sustained behavior change. Digitally enabled personalized outreach can improve patient’s experience by providing relevant, meaningful calls to action at a time when labor-intensive human-to-human personalization is challenged by systemic health staffing shortages. Strategic use of digital tools to engage patients and supplement human-to-human care scale personalization to the benefit of patient and provider experience. Specifically, digital personalization can support:

Identification of patients eligible for a procedure, service, or outreach

Engaging patients with a personalized call to action

Augmenting care through the use of digital tools, and

Monitoring patient progress over time to ensure continued support.

The technology to support a more personalized patient experience includes infrastructure to consolidate rich data, an intelligence capability to identify candidates for each call to action, and an engagement layer that presents patients with personalized output. Steps to develop and execute a personalization strategy are provided.

Keywords: access to care, communication, health information technology, patient engagement, telehealth

Introduction to the Issue

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may be the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back with respect to healthcare staffing. Staffing shortages are associated with higher morbidity and mortality 1 and reduced patient satisfaction. 2 They also logically limit the ability of healthcare professionals to deeply personalize the care experience offered to individual patients.

Yet, we know one size fits all doesn’t work for helping patients navigate healthcare and associated lifestyle changes. Personalization is key to providing relevant, meaningful guidance.3,4 When high-touch human-delivered personalization is challenging, digital technology can fill some of the gaps to help patients take the right next action toward their goals while alleviating demands on the health system. If behaviors can be self-, rather than provider-, managed without sacrificing quality outcomes, patients may not need an appointment; if patients can be prompted to reach out to providers appropriately via digital means, then high-touch outreach and care can be reserved for patients with more complex needs or less digital engagement. The staffing crisis offers an opportunity to rethink the use of digital in personalized patient experience. Meanwhile, technological advances make executing on this vision more possible than ever.

Specifically, technology can personalize four different parts of the patient journey to benefit of patient experience within a lean operations model:

Identifying patients who are eligible for a procedure, service, or outreach

Engaging patients with a personalized call to action

Augmenting care with digital tools, and

Monitoring patient progress over time to ensure continued support.

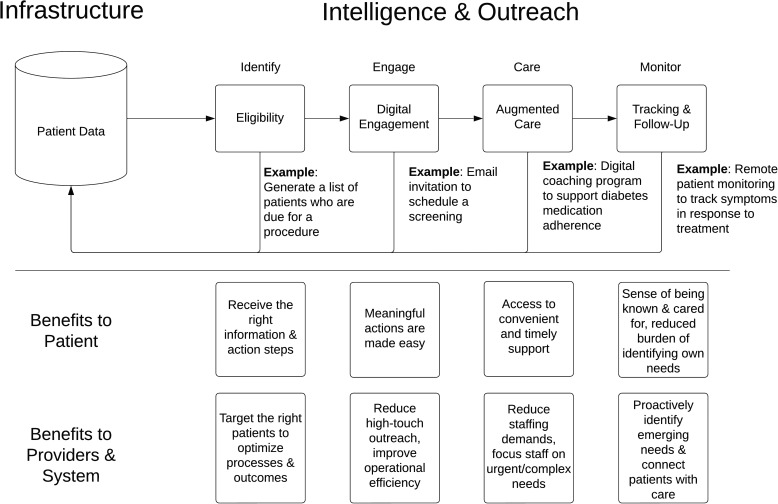

There are three main technology requirements to be met to accomplish this. First, data must be consolidated and organized in an infrastructure layer. Then, there needs to be an intelligence capability to determine personalization needs. Finally, outreach capabilities must exist to surface the personalization to patients and provide a call to action. While many providers have access to digital tools that theoretically enable such personalization, without organizing around these capabilities, the value will not be realized. See Figure 1 for an overview of how digital can provide personalized support and the benefits at each touchpoint.

Figure 1.

The combination of infrastructure, intelligence, and outreach capabilities can help automate patient engagement by identifying, engaging, offering care options, and monitoring ongoing patient progress. This benefits patients, providers, and systems at each step.

Key Factors for Consideration

Evidence from behavior science suggests personalization yields better engagement 5 and outcomes 6 in behavioral interventions. Yet, personalization can be difficult to achieve in practice. While humans are masters of personalization, they are not scalable, and personalizing with technology can require a large amount of data and a sophisticated strategy. 7 Ideally, personalization takes account of people's health care needs and preferences, as well as their social determinants of health, their consumer behaviors, and other factors. The information we need to understand people in context and personalize exists but must be gathered and organized.

This data must also be kept fresh. A key element of personalization is recognizing that people change over time and across contexts. A feedback loop, including whether people follow through with calls to action as well as qualitative feedback, lets provider organizations gauge the success of personalization attempts and adjust as necessary. While types of artificial intelligence (AI) such as reinforcement learning can leverage such feedback data, 8 more analog methods would also suffice, especially for smaller patient populations or pilot studies.

Digitally enabled personalization does not replace high-touch human support. Not everyone will respond to digital outreach or support; some patients prefer phone calls to text messages, for example. 9 Similarly, some patients will eschew digital care experiences in favor of traditional in-person appointments. But if we can use technology to engage those whose needs are suited to a highly digital experience with only specific live touchpoints, we can reduce the overall burden on a strained health system without sacrificing outcomes.

While many healthcare organizations have invested in some or all of these components, none have fully realized the promise of digital personalization. Imagine a future where a patient relocates to a health system. Her record from prior providers is sent over and digitally mined to understand her care needs, which include an annual physical, a mammogram, and a flu shot (identify). She receives personalized outreach for each encounter: An email with a link to an online scheduling tool for a primary care provider who accepts new patients, an email addressing likely reasons she is three years’ overdue for a mammogram with options to schedule at various locations, and a text to book a flu shot this week at a local pharmacy (engage). The physician suggests the patient might have prediabetes, so she is prescribed with a digital app to support dietary changes and record weekly biometrics (care). When her glucose readings don’t show improvement 6 weeks later, the patient is prompted to schedule a follow-up provider visit to discuss more aggressive tactics (monitor). Outside of the actual clinical encounters, this outreach is fully digital.

Healthcare technology is ready to provide this more sophisticated level of personalization building on the investments to date. This is thanks to advancements in three main areas: AI, data aggregation, and health consumer technology (including wearables, digital health apps, and remote patient monitoring tools).

Recommendations

Successfully building and executing a digital personalization strategy requires bringing together the right technology partners to aggregate the wealth of available patient data, determine appropriate next steps, and engage patients in behaviors like consuming education, scheduling care, monitoring symptoms, or adopting lifestyle changes. Recommendations include:

Mapping the Patient Care Experience. Organizations hoping to digitally personalize the patient experience must understand the often complex set of possible touchpoints for a particular care path and associated dependencies, to identify which can be replaced or enhanced with a digital experience. For example, mapping the communications processes used for patient outreach can identify opportunities to prioritize digital channels and selectively deploy high-touch human phone calls only for those not responsive to emails, text, or portal messages. Or it may be possible to substitute virtual care for a live provider visit in some cases.

Consolidating Patient Data. A serious challenge in the United States is patient data stored in silos across different care organizations, although legislation such as the twenty-first Century Cares Act will require improved access and interoperability. 10 The more that patient data belongs to the patient rather than the point of care, the less fragmented it will be and the easier it will be to draw upon it for personalization. While it will take time to achieve a truly patient-centric data approach, organizations should plan how to break down data silos now in preparation for the future.

Identifying Supportive Technologies. The right technologies are needed to execute a personalized patient experience strategy. At a high level, organizations will need an infrastructure layer that consolidates or combines data, an intelligence or orchestration layer that prioritizes and identifies patterns in the data, and an engagement layer that surfaces the resulting personalization and calls to action to patients. Organizations may choose to work with one or multiple vendors to create the right technology set, or build their own.

Designing the Engagement Layer. The technology only enhances the patient experience when people are given personalized, data-driven calls to action. Healthcare organizations must thoughtfully design the new digital touchpoints identified in their experience mapping exercise to engage patients appropriately in their care. This may include crafting an email, text, IVR, or printed collateral, curating digital health apps to be made available to patients based on symptoms or diagnoses, upgrading the patient portal, or introducing virtual care capabilities.

The ideal digitally supported personalized patient experience includes:

Patients’ care needs are clearly identified based on their demographic, clinical, and psychosocial data as well as past behaviors, so that they are matched with the right set of services.

Patient outreach is personalized and targets meaningful and appropriate calls to action, through patients’ preferred communication channel(s).

When relevant digital health tools exist to support clinical care needs, such as coaching programs, monitoring devices, or digital therapeutics, patients are offered access to them, and they are incorporated into a care plan to enhance or replace in-person services.

When patients lack an immediate need for clinical support, digital tools help them monitor symptoms and track ongoing behavioral progress so that any new needs are quickly identified—essentially feeding back into patient data.

Conclusion

When clinical capacity is constrained by staffing shortages, technology can personalize a patient's experience across all of their healthcare needs while maintaining a high quality of care. A scalable approach to personalization enables efficient use of the availability capacity within the healthcare organization while offering patients opportunities to engage in health behaviors that they are more likely to accept. Thoughtful use of technology to personalize and connect patients to the various healthcare screenings, appointments, and treatments they need will likely improve outcomes as people are more inclined to follow recommendations, while ensuring that providers can focus on those patients most in need of their care. The overall patient experience will be enhanced by more meaningful and relevant outreach and providers prioritizing those aspects of the experience that require the human touch. People deserve to be treated like the N of 1 they are; technology can help overburdened health care providers do that.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Amy Bucher https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6514-4441

References

- 1.McHugh MD, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Windsor C, Douglas C, Yates P. Effects of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation on nurse staffing and patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay: a prospective study in a panel of hospitals. Lancet. 2021/05/22/ 2021;397(10288):1905‐13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00768-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridges J, Griffiths P, Oliver E, Pickering RM. Hospital nurse staffing and staff–patient interactions: an observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(9):706. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schapira MM, Swartz S, Ganschow PS, et al. Tailoring educational and behavioral interventions to level of health literacy: a systematic review. MDM Policy Pract. 2017;2(1):238146831771447. doi: 10.1177/2381468317714474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer LC, Fortuna KL, Jones C, et al. Back to the future: achieving health equity through health informatics and digital health. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(1):e14512. doi: 10.2196/14512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison L, Moss-Morris R, Michie S, Yardley L. Optimizing engagement with internet-based health behaviour change interventions: comparison of self-assessment with and without tailored feedback using a mixed methods approach. Br J Health Psychol. 2014/11/01 2014;19(4):839‐55. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayberry LS, Nelson LA, Greevy RA, et al. 819-P: personalized texts improve adherence and A1c over 6 months among high-risk adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2019;68(Supplement_1). doi: 10.2337/db19-819-P [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonul S, Namli T, Huisman S, Laleci Erturkmen GB, Toroslu IH, Cosar A. An expandable approach for design and personalization of digital, just-in-time adaptive interventions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(3):198‐210. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mnih V, Kavukcuoglu K, Silver D, et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature. 2015;518:529‐33. doi: 10.1038/nature14236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed N, Boxley C, Dixit R, et al. Evaluation of a text message–based COVID-19 vaccine outreach program among older patients: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 2022/7/18 2022;6(7):e33260. doi: 10.2196/33260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lye CT, Forman HP, Daniel JG, Krumholz HM. The 21st century cures act and electronic health records one year later: will patients see the benefits? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(9):1218‐20. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]