Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Cadaver dissection has become the gold-standard for anatomical education in US medical schools. Ethical issues regarding cadavers may not be as obvious as in living patients, which can lead to their potential neglect in medical school curricula. In this study, we assessed the different ethical concerns (ECs) of medical students regarding cadavers in the gross anatomy lab (GAL), gathered student information, including self-reported academic performance (AP) in the GAL, and determined the best predictors for a student's EC.

METHODS

All second-year medical students at the University of Toledo were invited to complete an anonymous, online-survey. Participants were presented with 10 hypothetical but realistic lab scenarios and asked to rate their EC for each on a 5-point Likert scale. Gender, age, and scores received in the GAL course were also collected. A multiple linear regression model was used to find the best predictors of the total EC score.

RESULTS

A total of 112 (63%) responses to the online-survey were recorded. The highest EC was for Q7: Taking pictures of the cadaver. The lowest EC was for Q10: The dissection of cadavers itself is an EC. Gender was the best predictor of total EC, followed by age. Female total EC was significantly higher than that for males (35.8 ± 5.5 vs 33.1 ± 7.9). Female scores for Q1 and Q2 were significantly higher than those for males. Total EC for students in the age group 25 to 34 was significantly higher than those in the age group 18 to 24 (35.9 ± 6.1 vs 33.9 ± 7.2). No significant difference was found for individual scenarios. AP was not significantly related to the total score or the scores of the individual scenarios.

CONCLUSION

The significant differences in ECs of medical students found in our study indicate that not all students have the same outlook towards the GAL specifically and ECs generally.

Keywords: Ethics, dissection, cadaver, medical student, gross anatomy lab

Introduction

Over the past 500 years, medical education has changed drastically in many different ways. One facet that has remained particularly persistent and remains as one of the most universally recognizable steps in the journey to becoming a physician is human dissection. 1 The gross anatomy lab (GAL) course has become an integral part of medical education. In addition to the vast educational benefits of anatomical dissection of the human body, the psychosocial aspect may be the greatest benefit to the development of the medical student.2,3

The main ethical concern (EC) of cadaver dissection lies with respect to human life. 4 Historically, many institutions made use of the bodies of executed criminals for anatomical dissection. 5 However, today bodies used for academic purposes are obtained through donation programs that require written consent from the donor. 6

Extensive ethical guidelines are in place not only for the donation of bodies, but also for every aspect of their use, transfer, storage, and disposal.6–9 Furthermore, academic institutions have set in place ethical standards to be maintained in the GAL including limiting entrance into the GAL to enrolled students, prohibiting any photography in the GAL, and ensuring appropriate maintenance and handling of the cadavers.10–12

Today, medical schools in the United States incorporate a significant amount of ethical education into their anatomical dissection courses. 6 In addition to this introductory ethical education, students often develop their own ethical perspectives following their individual experiences in dissection. A study conducted by Stephens et al 13 suggested that donor dissection had a strong impact on students’ perception of medical ethics. The study highlighted the importance of anatomical dissection as a merging point between medical and ethical education for students.

Nonetheless, ethical issues regarding cadavers may not be so obvious, especially to a medical student who has never been involved in an anatomical dissection of the human body before. This unique experience can be overwhelming to the novice learner at first, especially if there is no explicit education on the appropriate ethical behavior that should be upheld in the GAL. We aimed to study the response students have when presented with ethical scenarios that were taught as rules of the GAL in their course introduction as well as scenarios that were not taught in the course introduction. Therefore, in this study, we assess the relationship between different ECs in the GAL and the personal, social, and academic performance (AP) of medical students. In addition, we determined the best predictors for a student's level of EC.

Methods

Using the Qualtrics platform, a questionnaire was designed to assess the EC levels of medical students at the University of Toledo. The length of the study in which the questionnaire was available to students, was a total of 4 weeks from July 19, 2021, to August 19, 2021. Prior to beginning the questionnaire, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. This brief, anonymous, online questionnaire presented students with 10 hypothetical but realistic lab scenarios (Table 1) and each student was asked to rate their level of EC for each on a standardized scale from 1 to 10. The term “ethical concern” was not defined in the survey and was left up to the interpretation of the students. Some of the scenarios were derived from the rules of the GAL presented in the introductory material of the course (Q3, Q5, Q6, Q7, Q8, and Q9), while others reflected potential concerns as deemed appropriate by the authors of the study. In addition, gender, age, and scores received in the GAL course were also collected. The questionnaire was not validated previously due to the nature of the study which required the incorporation of unique questions relevant to the GAL experience at the University of Toledo. Additionally, the population of the study included all second-year medical students at the University of Toledo which eliminated the availability of a potential pilot population from within the class. Following the completion of the first semester of the GAL course, all second-year medical students at the University of Toledo were invited to complete the study through an email that contained a short description of the study and a link to the survey on the Qualtrics platform. In addition to the original email, 3 reminder emails approved by the IRB at the University of Toledo (IRB number: 301067), were sent to the students.

Table 1.

The 10 hypothetical but realistic scenarios presented in the questionnaire.

| Q1 | Leaving the face of the cadaver uncovered when dissecting other parts of the cadaver. |

| Q2 | Leaving the genitalia of the cadaver uncovered when dissecting other parts of the cadaver. |

| Q3 | Making jokes about the cadaver. |

| Q4 | Placing anatomy books directly on the cadaver. |

| Q5 | Poor maintenance of the cadaver (lack of hydration and anti-fungal implementation). |

| Q6 | Leaving the body bag open when the cadaver is not being used. |

| Q7 | Taking pictures of the cadaver. |

| Q8 | Eating food around the cadavers. |

| Q9 | Listening to music/podcasts while working on the cadavers. |

| Q10 | The dissection of cadavers itself is an ethical concern. |

The online-survey also collected demographic information (age, gender, and ethnicity/race) of the participants in the study. An example of the questionnaire can be found in the Supplemental Material. A multiple linear regression model was used to find the best predictors of the total EC score.

Results

The anonymous survey was shared with 179 second-year medical students at the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, and a total of 112 responses were collected with a 63% response rate.

A total of 63% of participants were 18 to 24 years of age and 37% were 25 to 34 years of age. As for gender, 47% of the participants were male, 50% female, 1% nonbinary/third gender, and 2% preferred not to answer. In regards to ethnicity/race, 69.16% of the participants identified as “White,” 14.02% as “Asian,” 10.28% as “Black or African American,” 0.93% as “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,” and 5.61% chose “Other: Hispanic or Middle Eastern.”

The results of the multiple linear regression model are presented in Table 2. The AP predictors had shown no significance in predicting the total score or the scores of the individual scenarios with a P-value of .4409 for AP1 (AP on the musculoskeletal gross anatomy laboratory practical exam) and .4875 for AP2 (AP on the neuroscience gross anatomy laboratory practical exam). However, as for gender and age, both were strong predictors of the total ethical scores with P-values of .0321 and .0428, respectively. Female total EC was significantly higher than that for males (35.8 ± 5.5 vs 33.1 ± 7.9, respectively). Moreover, female scores for Q1 and Q2 were significantly higher than those for male students. Total EC for students in the age group 25 to 34 was significantly higher than those in the age group 18 to 24 (35.9 ± 6.1 vs 33.9 ± 7.2, respectively). The level of EC for each individual scenario was also assessed. Q7 had a mean EC of 4.46, while Q10 had a mean EC of 1.51 (Table 3). This indicated that Q7 (taking pictures of the cadavers) had the highest EC. While Q10 (the dissection of cadavers itself is an EC) was shown to be of the lowest EC. Moreover, Q3 (4.38 ∓ 0.98) and Q5 (4.1518 ∓ 0.96) were the second and third highest ECs, respectively.

Table 2.

Predictive values for EC.

| PREDICTOR | TYPE III SS | MEAN SQUARE | F VALUE | Pr > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP1 | 120.76 | 40.25 | 0.91 | 0.4409 |

| AP2 | 108.84 | 36.28 | 0.82 | 0.4875 |

| Gender | 210.06 | 210.06 | 4.73 | 0.0321 |

| Age | 187.16 | 187.16 | 4.22 | 0.0428 |

Abbreviations: EC, ethical concern; AP, academic performance.

Table 3.

Mean ethical concern (EC) for each scenario, ranked from highest to lowest.

| SCENARIO | MEAN | STD DEV | MEDIAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q7 Taking pictures of the cadaver. | 4.46 | 1.03 | 5 |

| Q3 Making jokes about the cadaver. | 4.38 | 0.98 | 5 |

| Q5 Poor maintenance of the cadaver (lack of hydration and anti-fungal implementation). | 4.15 | 0.96 | 4 |

| Q8 Eating food around the cadavers. | 4.01 | 1.41 | 5 |

| Q2 Leaving the genitalia of the cadaver uncovered when dissecting other parts of the cadaver. | 4.00 | 1.19 | 4 |

| Q6 Leaving the body bag open when the cadaver is not being used. | 3.89 | 1.13 | 4 |

| Q1 Leaving the face of the cadaver uncovered when dissecting other parts of the cadaver. | 3.55 | 1.29 | 4 |

| Q4 Placing anatomy books directly on the cadaver. | 2.62 | 1.24 | 2 |

| Q9 Listening to music/podcasts while working on the cadavers. | 2.08 | 1.26 | 2 |

| Q10 The dissection of cadavers itself is an ethical concern. | 1.51 | 0.92 | 1 |

Specific scenarios which were violations of GAL rules, as explained in the course introduction, generally had higher scores. The 4 scenarios with the highest scores were Q7 (taking pictures of the cadaver), Q3 (making jokes about the cadaver), Q5 (poor maintenance of the cadaver), and Q8 (eating food around the cadavers). Each of these was specifically covered in the precourse ethical guidelines and rules of the GAL. On the other hand, scenarios that were not covered tended to score lower, for example, Q10 (the dissection of cadavers itself is an EC) had the lowest EC score of all the scenarios. One exception to this was Q9 (listening to music/podcasts while working on the cadavers), which despite being against the rules of the GAL, still had the second-lowest EC score.

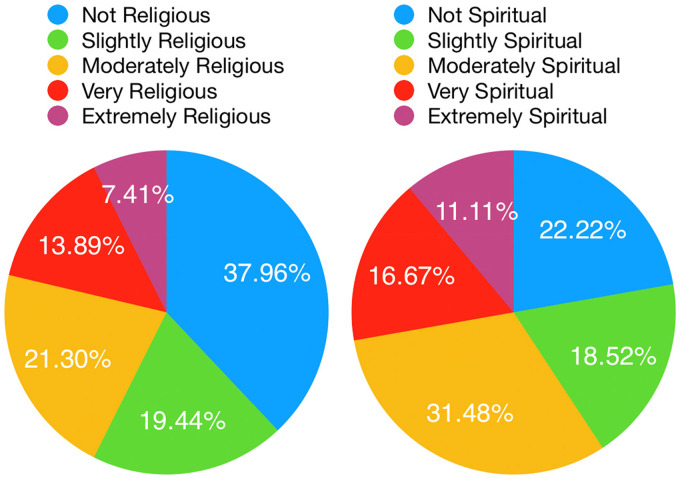

Part of the survey also included open-ended questions such as “(A) Do you feel extra protective of your cadaver, and if so, why?” and “(B) Do you have any additional ECs that were not expressed in this survey”. 47.27% of students responded “Yes” to question A (Figure 1). Of the students who responded with “Yes,” many answers to the question “why?” were identified such as the hard work and care in maintaining the cadaver, an act of respect to the donor, considering the cadaver as their first patient, and should be treated as one, and due to a sense of responsibility. As for question B, the answers reported were minor concerns that were not ethical in nature, rather they were directed to the academic standpoint of the course. One of the answers to this question displayed an EC in regards to resting hands, books, tools, or organ parts on the cadaver's face.

Figure 1.

Answers to the question: Do you feel extra protective of your cadaver, and if so, why?

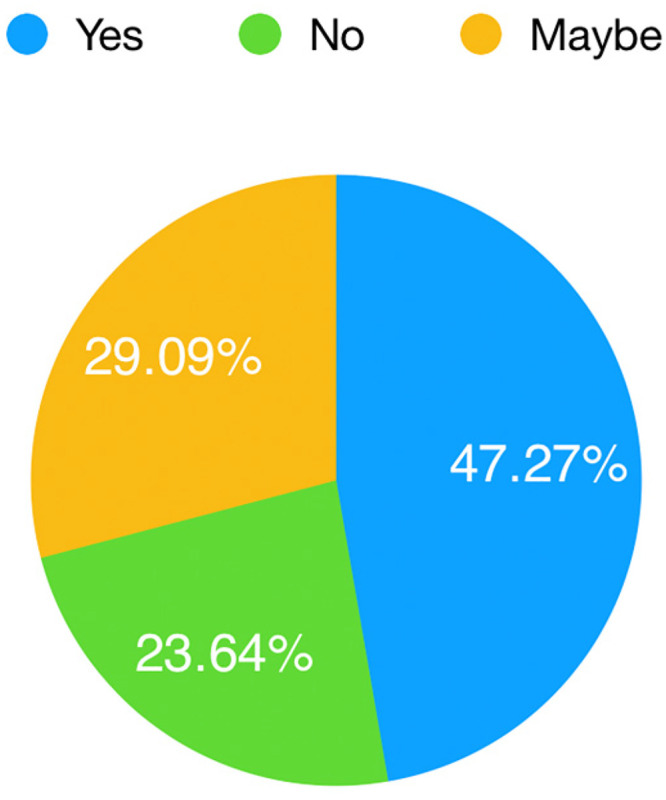

In addition, the level of religiosity and spirituality was assessed in the survey as well. Participants were asked to rate this level on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 being not religious or spiritual, 3 being moderately religious or spiritual, and 5 being extremely religious or spiritual (Figure 2). According to the survey, the level of religiosity measured at a mean of 2.33 ∓ 1.31 with 37.96% of students being “not religious,” 21.3% “moderately religious,” and 7.41% being “extremely religious.” A mean of 2.76 ∓ 1.28 was measured for the level of spirituality. 22.22% of students claimed to be “not spiritual,” 31.48% “moderately spiritual,” and 11.11% “extremely spiritual.”

Figure 2.

Religiosity and spirituality levels of students.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the ECs of medical students in the GAL and determined the predictive power of different student characteristics for their level of EC. We aimed to indirectly study the importance of precourse introduction and ethical education on students and their experience in the GAL. Our study demonstrated that female students had significantly higher EC than male students. Additionally, we found that total EC for students in the age group 25 to 34 was significantly higher than those in the age group 18 to 24. AP was not significantly related to either the total score or the scores of the individual scenarios. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study designed to investigate predictors for EC of medical students in the GAL setting.

Recently, studies assessing the emotional intelligence of medical students have found female students to have significantly higher scores than male students. 14 Additionally, a study conducted on Turkish nursing students found a correlation between the emotional intelligence and ethical sensitivity of students. 15 Our findings align with these studies as we found female students to have significantly higher EC scores than male students. However, multiple studies have shown a correlation between AP and emotional intelligence which does not align with the findings in our study as AP was not a strong predictor for EC.14,16,17

Interestingly, we found that students tend to report a higher level of EC when faced with scenarios that were explicitly against the rules of the GAL as presented in the course introduction. This finding likely suggests that ethical education in the introduction to anatomical courses is highly effective, particularly for medical students, most of whom have no prior experience with such ethical situations.

There are some limitations to our study. First, the questionnaire we designed has not been previously validated. Second, although our sample size is sufficient, it is relatively small. Additionally, our population was limited to one institution. Despite these limitations, the findings of our study can be supported by the strong data we collected.

Conclusion

Further investigation of EC in the GAL can help shape the future of ethical education curriculum reforms. The significant differences in ECs of medical students found in our study indicate that not all students have the same outlook towards the GAL specifically and ECs in general. These significant differences can potentially manifest themselves in different areas of medical practice throughout a student's future as a physician. For this reason, a greater emphasis on ethical education in medical schools may have a significant impact on students that goes far beyond the GAL.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mde-10.1177_23821205231168505 for Assessing the Ethical Concerns of Medical Students in the Gross Anatomy Lab by Mohamad Nawras, Jihad Aoun, Vahid Yazdi, Mordechai Hecht, Sadik Khuder and Patrick Frank in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgments for this study.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Approved by the IRB at the University of Toledo (IRB number: 301067).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained.

ORCID iD: Mohamad Nawras https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8345-8049

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dyer GS, Thorndike ME. Quidne mortui vivos docent? The evolving purpose of human dissection in medical education. Acad Med. 2000;75(10):969-979. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeckers A, Boeckers T. The dissection course – a psychological burden or an opportunity to teach core medical competencies: a narrative review of the literature. Eur J Anat. 2016;20(4):287-298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalthur S, Pandey A, Prabhath S. Benefits and pitfalls of learning anatomy using the dissection module in an Indian medical school: a millennial learner's perspective. Transl Res Anat. 2022;26(6510):100159. doi: 10.1016/j.tria.2021.100159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaikh ST. Cadaver dissection in anatomy: the ethical aspect. Anat Physiol. 2015;5:007. doi: 10.4172/2161-0940.S5-007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh SK, Sharma S. Cadaveric preservation under adverse climatic conditions. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(10):1287-1288. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1505-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh SK. The practice of ethics in the context of human dissection: setting standards for future physicians. Ann Anat. 2020;232:151577. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2020.151577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajracharya S, Magar A. Embalming: an art of preserving human body. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2006;4(4):554-557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riederer BM, Bueno-López JL. Anatomy, respect for the body and body donation – a guide for good practice. Eur J Anat. 2014;18(4):361-368. https://eurjanat.com/v1/journal/paper.php?id=140189br [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DG. Searching for good practice recommendations on body donation across diverse cultures. Clin Anat. 2016;29(1):55-59. doi: 10.1002/ca.22648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh SK. Paying respect to human cadavers: we owe this to the first teacher in anatomy. Ann Anat. 2017;211:129-134. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill DR, Leonard RJ, Weiglein AH, von Lüdinghausen M. Viewpoint: unrecognized values of dissection considered. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002;24(3-4):137-139. doi: 10.1007/s00276-002-0053-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vani NI. Safety and ethical issues of bare hand cadaver dissection by medical students. Indian J Med Ethics. 2010;7(2):124-125. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2010.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephens GC, Rees CE, Lazarus MD. How does donor dissection influence medical students’ perceptions of ethics? A cross-sectional and longitudinal qualitative study. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(4):332-348. doi: 10.1002/ase.1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aithal AP, Kumar N, Gunasegeran P, Sundaram SM, Rong LZ, Prabhu SP. A survey-based study of emotional intelligence as it relates to gender and academic performance of medical students. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2016;29(3):255-258. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.204227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ergin E, Koçak Uyaroğlu A, Altınel B. Relationship between emotional intelligence and ethical sensitivity in Turkish nursing students. J Bioeth Inq. 2022;19(2):341-351. doi: 10.1007/s11673-022-10188-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somaa F, Asghar A, Hamid PF. Academic performance and emotional intelligence with age and gender as moderators: a meta-analysis. Dev Neuropsychol. 2021;46(8):537-554. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2021.1999455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altwijri S, Alotaibi A, Alsaeed M, et al. Emotional intelligence and its association with academic success and performance in medical students. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2021;9(1):31-37. doi: 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_375_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-mde-10.1177_23821205231168505 for Assessing the Ethical Concerns of Medical Students in the Gross Anatomy Lab by Mohamad Nawras, Jihad Aoun, Vahid Yazdi, Mordechai Hecht, Sadik Khuder and Patrick Frank in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development