Abstract

Background:

Sleep disturbances are common and bothersome among cancer and noncancer populations. Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) is commonly used to improve sleep, yet its efficacy and safety are unclear.

Methods:

We systematically searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE from inception through October 5, 2021, to identify randomized trials of Suanzaoren. We included randomized trials comparing Suanzaoren to placebo, medications, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or usual care for improving sleep outcomes in cancer and noncancer patients with insomnia or sleep disturbance. We performed a risk of bias analysis following Cochrane guidelines. Depending on heterogeneity, we pooled studies with similar comparators using fixed- and random-effects models.

Results:

We included participants with insomnia disorder (N = 785) or sleep disturbance (N = 120) from 9 trials. Compared with placebo, Suanzaoren led to significant subjective sleep quality improvements in participants with insomnia and patients with sleep disturbance combined (standard mean difference −0.58, 95% CI −1.04, −0.11; P < .01); Compared with benzodiazepines or CBT, Suanzaoren was associated with a significant decrease in insomnia severity (mean difference −2.68 points, 95% CI −5.50, −0.22; P = .03) at 4 weeks in the general population and cancer patients. The long-term effects of Suanzaoren were mixed among trials. Suanzaoren did not increase the incidence of major adverse events. The placebo-controlled studies had a low risk of bias.

Conclusion:

Suanzaoren is associated with short-term patient-reported sleep quality improvements among individuals with insomnia or sleep disturbance. Due to the small sample size and variable study quality, the clinical benefits and harms of Suanzaoren, particularly in the long term, should be further assessed in a sufficiently powered randomized trial.

Registration:

PROSPERO CRD42021281943

Keywords: Suanzaoren, herbal formula, sleep disturbance, insomnia, clinical evidence

Introduction

Insufficient sleep is a prevalent health problem that has received worldwide attention in recent decades. 1 General sleep disturbance, a sleep disorder not due to a substance or known physiological condition, ranges from difficulty falling asleep to nightmares, sleepwalking, and sleep apnea. Insomnia is defined as difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep. General sleep disturbance is highly prevalent in adults, seen in 32.1% to 60% of individuals, with over 40% reporting a greater than 1-hour gap between sleep need and actual sleep duration.2-4 Insomnia is also common, reported in 6% to 30% of primary care patients and over 60% of patients in the oncological setting.5-9 Disrupted sleep leads to reduced daytime functioning and impaired quality of life and is associated with fatal accidents at work and motor-vehicle crashes. 10 Insomnia has also been associated with long-term health consequences, including cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders, and premature mortality.11-16

Conventional insomnia and sleep disturbance treatments include hypnotic drugs and cognitive behavioral therapy. 17 However, many sedatives and hypnotic drugs have undesirable side effects, and the long-term efficacy of these approaches is limited 18 ; further, only some patients have real-world access to cognitive behavioral therapy. 19 Rates of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use for insomnia are high; for example, around 1.6 million people in the US and 2.1 million in Australia report CAM use for sleep disturbances.20,21 CAM includes many interventions, mind-body practices, and herbal and alternative therapies. Despite widespread use, there is little rigorous efficacy and safety data, so CAM is inconsistently recommended by sleep guidelines. 22 Better evidence is critical to guide the practice of CAM in sleep care.

The herbal medicine Suanzaoren (Semen Ziziphus Spinosae) has been used for centuries to improve sleep health in Asian populations. 23 Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in the use of Suanzaoren in Western populations.24-26 Regardless of comorbid symptoms and pathology, Suanzaoren is the most frequently prescribed Chinese herb for mitigating insomnia symptoms.27-29 Although the mechanisms of action of Suanzaoren remain unclear, pharmacological studies reveal that its major bioactive constituents, including jujubogenin, jujuboside A, and jujuboside B, may increase sleep activity via GABA or serotonin receptors.30-33 Several recent randomized clinical trials have been conducted to assess the effect of Suanzaoren therapies for insomnia or sleep disturbance in different clinical settings, but results have been conflicting.25,34-37

Suanzaoren therapies thus have the potential to be a valuable option for improving sleep health, but a better understanding of their efficacy and safety is needed. Previous reviews have addressed the effects of herbal formulas on sleep health, but none has specifically evaluated Suanzaoren.27,38 To better inform the use of Suanzaoren, we conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Suanzaoren-related herbal or dietary supplements compared to placebo, conventional treatment, or usual care, for sleep improvements in patients with general sleep disturbance or a clinical diagnosis of insomnia.

Methods

Study Inclusion Criteria

The review included English-language publications of parallel-group RCTs with no restriction on trial status, study location, or publication year. Crossover trials and quasi-RCTs were excluded. We included studies that evaluated patients with insomnia or general sleep disturbance (regardless of demographic characteristics). We compared herbal formulas in which Suanzaoren was the critical ingredient to placebo, active treatment, or usual care. Outcomes of interest included (1) sleep improvements measured by validated instruments, such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), either during (short-term) or after (long-term) treatment; (2) anxiety, depression, fatigue, or cognitive impairments measured by validated tools such as Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), respectively; and (3) adverse events (AEs) associated with treatment. When capturing long-term outcomes, we utilized the most extended post-treatment follow-up findings.

Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

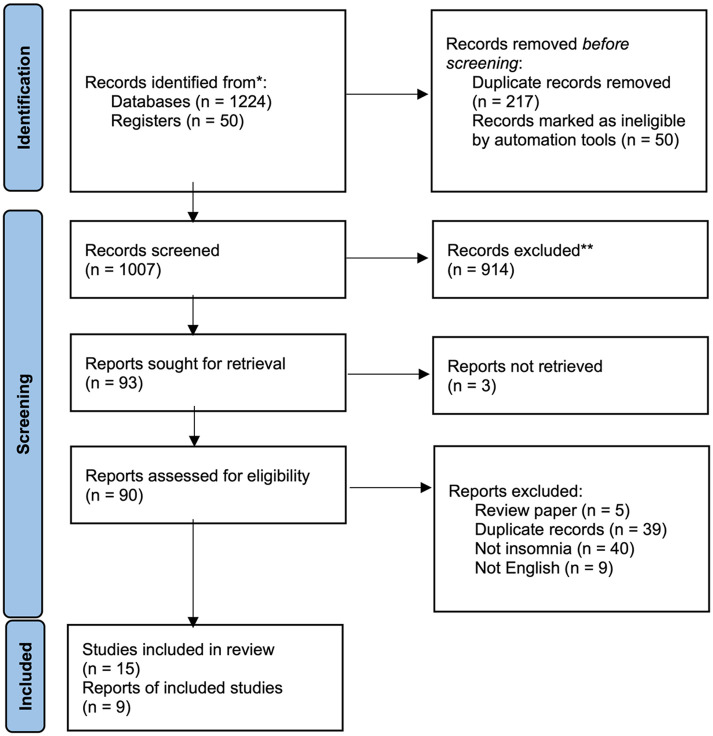

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from inception through October 5, 2021, for RCTs that evaluated the effect of Suanzaoren on insomnia or sleep disturbance. The detailed search strategy is provided in Table S1 (Supplemental Material). We searched 2 global trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO trial registry) for ongoing trials and examined reference lists from published systematic reviews to identify possible missing studies. Two reviewers (MY and HW) initially reviewed titles, followed by abstracts, for inclusion in the review. The same 2 authors then performed a full-text article review and recorded the reason for exclusion, with differences resolved by discussion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review.

Seven reviewers (MY, HW, YZ, FZ, XL, YC, and JC) independently extracted study details (study origin, year of publication, patient demographics, intervention, comparator, outcome and results, setting, AEs, etc.) using a modified Cochrane data-extraction form. 39 Three reviewers (MY, HW, and YZ) cross-checked extracted data to ensure consistency and accuracy. We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias assessment tool for randomized trials, 40 with all assessments performed by 2 independent reviewers (MY and HW) and results confirmed by consensus among the larger reviewer group. Data required for meta-analysis was transferred from the extraction form to the RevMan software (version 5.3) through double data entry. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions among the reviewer group.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted meta-analyses to test the hypothesis that Suanzaoren treatment in any dose is associated with improvements in sleep symptoms at the end of treatment (short-term) and the last post-treatment follow-up (long-term), compared to controls among patients with insomnia or sleep disturbance of any cause. We pooled data when 3 or more studies used the same type of control (i.e., placebo, active treatment, or waitlist) across populations, hypothesizing that the effect of Suanzaoren would be similar across different patient groups. Because insomnia and sleep disturbance indicate a similar underlying sleep problem, we also pooled studies that addressed either problem in the primary analysis, with subgroup analysis, to better clarify the effect for each specific condition.

We used RevMan software version 5.3 for the synthesis and meta-analysis of efficacy data. We summarized continuous data using the mean difference (MD). For continuous data, when different scales were used to measure the same outcome, the effect size was reported using the standard mean difference (SMD). For each pooled analysis, we assessed heterogeneity using the chi-square statistic for which P < .10 indicates significant heterogeneity, 41 and the I 2 test quantifies the proportion of variation among studies caused by heterogeneity. Meta-analysis was performed with a random-effects model when I 2 > 50% or significant methodological heterogeneity was present. Subgroup or sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the cause of substantial heterogeneity. A descriptive analysis is presented if the source of heterogeneity was unclear.

Quality Control

Each reviewer received comprehensive methodology training. An independent reviewer (SDK) performed quality monitoring, including double entry, data monitoring, and cross-validation.

Results

Literature Search

We found 1224 publications and 50 additional registry records in the initial database search. After duplicate removal (n = 217), we screened 1057 records for eligibility and excluded 1042 due to ineligibility or irrelevance (Figure 1). We included 9 completed and 6 ongoing trials (Table S2, Supplemental Material) in this review.25,34-37,42-45

Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of the 9 included studies are detailed in Table 1. Included studies originated from Australia, China, South Korea, and Taiwan and were published between 2015 and 2021. All participants were from primary/secondary health centers or hospitals. Participant populations varied in age and were predominantly female. Patients from 5 studies had a clinical diagnosis of primary insomnia disorder with moderate to severe intensity25,36,43-45; in 2 studies, patients had chronic insomnia during cancer treatment, 42 or post-ischemic stroke. 35 The remaining 2 studies included patients who scored more than 5 on the PSQI and experienced general sleep disturbance due to methadone maintenance 34 or cancer. 37

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Author | Region, setting | Participants | Intervention | Control | Outcomes and main results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | Diagnosis | Sample size | |||||

| Birling et al 25 | Australia, Trial center | E 52 (13) C 50 (16) |

Insomnia | E: 38 C: 47 |

ZRAS, 3 capsules, 2.28 g/capsule; oral, q.d. 4 weeks | Placebo 3 capsules of placebo oral q.d. 4 weeks | • ISI: E 11.6 (0.9), C 12.3 (0.9) • DASS: E 5.8 (0.8), C 5.9 (1.0) • FSS: E 33.1 (2.0), C 28.9 (1.8) • AQoL: E 16.3 (0.4), C 16.7 (0.5) • CSD and Actigraphy |

| Chan et al 34 | Taiwan, Hospital | E 40.6 (7.2) C 38.6 (6.9) |

General sleep disturbance | E: 45 C: 45 |

SZRT 4 g granules oral t.i.d 4 weeks | Placebo 4 g, granules oral t.i.d. 4 weeks | • PSQI: E 7.8 (3.7), C 9.6 (3.1) • BAI: E 12.8 (13.2), C 8.8 (13.0) • BDI-II: E 13.0 (13.9), C 11.5 (13.3) • Heroin craving by VAS and Sleep dairy |

| Dai et al 35 | China, Hospital | E 59.9 (8.3) C1 59.1 (8.8) C2 60.5 (9.2) |

Insomnia | E: 36 C1: 36 C2: 36 |

NXAS 1 bag of herbal granules oral b.i.d. 4 weeks | C1 placebo 1 bag, oral b.i.d. 4 weeks C2 Zopiclone 3.75 mg oral q.d. 4 weeks |

• ISI: E 11.0 (4.4), C1 16.0 (4.4), C2 9.5 (3.7) • PSQI: E 7.0 (3.7), C1 13.5 (3.7), C2 8.0 (1.7) • TCM Syndrome |

| Hu et al 36 | China, Hospital | E NA C NA |

Insomnia | E: 60 C: 59 |

SZR-ZZC 150 ml herbal decoction, oral b.i.d. 4 weeks | Lorazepam 2 tablets, 0.5 mg/tablet, oral b.i.d. 4 weeks | • ISI: E 7.2 (3.6), C 9.4 (4.1) • PSQI: E 7.6 (3.8), C 12.0 (3.4) • SAS: E 35.3 (12.9), C 40.3 (10.5) • Polysomnography |

| Lee et al 37 | Korea, Hospital | E 55.7 (23-70) C 52.6 (38-73) |

General sleep disturbance | E: 60 C: 59 |

GGBT 3.75 g dried spray of herbal extractions oral t.i.d. 2 weeks | waitlist (no treatment) | • ISI: E −5.5 (4.4), C 0.1 (1.1) • BDI: E −1.3 (7.0), C -0.4 (0.7) • BFI: E −0.8 (0.8), C 0.0 (0.3) • MoCA: E −0.1 (1.6), C 0.3 (1.3) |

| Moon et al 42 | Korea, Hospital | E 63 (53-71) C 63 (54-67) |

Insomnia | E: 11 C: 11 |

Cheonwangbosimdan 20 ml herbal decoction oral q.d. 4 weeks | CBT-I once per week for 4 weeks | • ISI: E −8.5 (−12.0, −5.0), C −6.5 (−10.0, −3.0) • PSQI: E −7.5 (−9.0, −5.0), C −3.5 (−5.0, −2.0) • SAS: E −7.5 (−9.0, −4.0), C 2.0 (−2.0, 5.0) • BFI: E −1.5 (−2.3, −1.2), C −0.8 (−1.3, −0.1) • EQ-5D-5L: E 0 (−0.03, 0.05), C 0 (−0.13, 0.01) • ECOG-PS and ESS (All data were presented as mean with 95% CI for this study) |

| Mun et al 43 | Korea, Hospital | E 37.7 (4.8) C 37.3 (6.0) |

Insomnia | E: 20 C: 20 |

HT002 hot tea 3 g herb infusion, oral b.i.d. 4 weeks | Waitlist (no treatment) | • ISI: E −4.0 (0.8), C −0.4 (0.8) (4 weeks); E −4.8 (0.7), C 0.9 (0.7) (8 weeks) • PSQI: results not reported • SF-12: E 2.2 (0.9), C −2.5 (0.9) (physical component score); E 3.6 (2.1), C −3.5 (2.1) (mental component score) |

| Scholey et al 44 | Australia, Hospital | E 31.0 (10.5) C 29.6 (9.1) |

Insomnia | E: 86 C: 85 |

LZComplex3 two tablets, 5.2 g/tablet, oral q.d. 2 weeks | Placebo two tablets oral q.d. 2 weeks | • ISI: results not reported • PSQI: E −1.8 (2.1), C −1.3 (2.4) (2 weeks); E −1.5 (2.3), C −1.7 (2.8) (3 weeks) • STAI-S: results not reported • QoLs: E 2.7 (2.0, 3.4), C 3.0 (2.3, 3.7) (data were presented as mean with 95% CI) • CFS: E −0.9 (−1.4, −0.5), C −1.0 (−0.5, −1.5) (data were presented as mean with 95% CI) • MTF: E −0.5 (−1.4, 0.1), C −0.7 (−1.5, 0.5) (data were presented as mean with 95% CI) • LESE, ESS, and CSD |

| Song et al 45 | China, Hospital | E 44.0 (10.5) C 39.3 (9.4) |

Insomnia | E: 120 C: 120 |

JWSZRD 150 ml decoction oral b.i.d.; lorazepam 0.5 mg oral q.d. 12 weeks | Lorazepam 0.5 mg oral q.d. 12 weeks | • ISI: specific data not reported • SAS: specific data not reported • SDS: specific data not reported • SSS: specific data not reported • SF-36: specific data not reported • Sleep diary |

Abbreviations: E, experimental group; C, control group; ZRAS, Zhao Ren An Shen; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index, DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21-item; FSS, FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale; AQoL, Assessment of Quality of Life; CSD, Consensus Sleep diary; SZRT, Suan Zao Ren Tang; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BAI, Beck anxiety inventory; DBI, Beck Depression Inventory; VAS, visual analog scale; NXAS, NXAS, Nin Xing An Sheng; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; SZR-ZZC, Suan Zao Ren Tang-Zhi Zhi Chi Tang; SAS, Self Rating Anxiety Scale; GGBT, Gamguibi-tang; BFI, brief fatigue inventory; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores; CBT-I, Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; EQ-5D-5L, Euroqol-5 Dimensions 5 Levals; ECOG-PS, Eastern Corporative Oncology Group Performance Status; HT002, a herbal tea composed of 4 herbs; SF-12, 12-item Short Form Health Survey; LZComples3, a complex composed of lactium™; LESE, Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire, QoLs, Burckhardt Quality of Life Scale; CFS, Chalder Fatigue Scale; STAI-S, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; MTF, multi-tasking framework; JW-SZRDz, Jiawei Suan Zao Ren Decoction; SDS, Slef Rating Depression Scale; SSS, Somatic Self Rating Scale; SF-36, 36 item Short Form Health Survey.

Suanzaoren products included in interventions are summarized in Table S3 (Supplemental Material). Three studies reported manufacturing and quality assurance processes,25,36,43,45 consistent with the CONSORT extensions for Chinese herbal medicine formulas. 46 Control arms included placebo (n = 4),25,34,35,44 active drug/behavioral therapy (n = 4),35,36,42,45 and waitlist control (n = 2).37,43 One study included both placebo and positive treatment control arms. 35 All studies measured subjective sleep improvements using the ISI or the PSQI, and 2 included objective sleep measures (polysomnography, actigraphy).25,44 Five studies measured anxiety and depression severity,25,34,36,37,42, 3 measured fatigue severity,25,37,42,44, 2 evaluated cognitive function,37,44 and 4 assessed quality of life.25,42-44

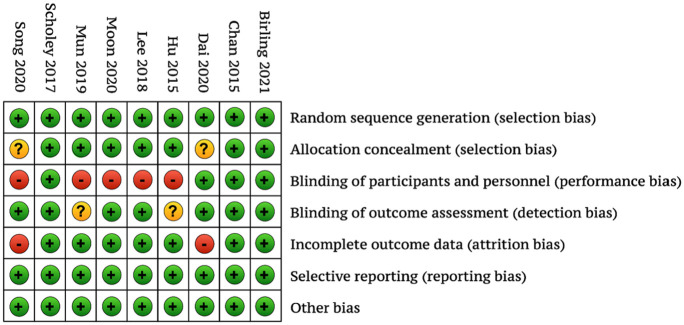

Risk of Bias of Included Studies

The 3 included placebo-controlled studies had a low risk of bias, and the remaining studies, using placebo, active, or waitlist controls, had a moderate to high risk of bias (Figure 2). When present, risk of bias was found in the domains of blinding of participants and personnel and incomplete outcomes data.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias associated with included trials.

Effects of Interventions

Short-term sleep improvements

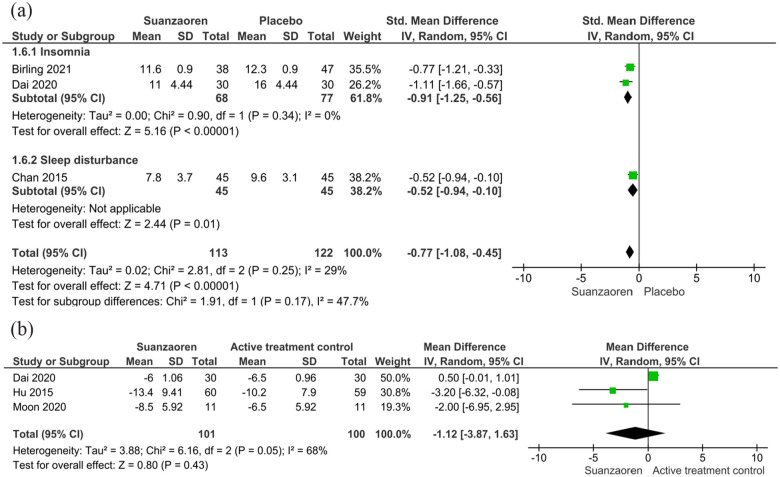

Pooled analysis of the 4 placebo-controlled studies (n = 406) showed that, among patients with insomnia and patients with sleep disturbance combined, Suanzaoren produced significant short-term sleep improvements (SMD −0.58, 95% CI −1.04, −0.11, P < .01; I 2 = 80%) compared to placebo,25,34,35,44 although there was significant heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis showed that statistical heterogeneity was reduced to an insignificant level (pooled effect: SMD −0.77, 95% CI −1.08, −0.45, P < .01; I 2 = 29%) through the exclusion of 1 study with 2-week treatment of Suanzaoren plus non-herbal ingredients such as lactium, magnesium, and vitamin B6. 44 Subgroup analysis of 2 studies that used the ISI to measure insomnia (n = 145) showed that 4-week Suanzaoren treatment was associated with significant improvements in insomnia severity (SMD −0.91, 95% CI −1.25, −0.56, P < .001; I 2 = 0%)25,35 (Figure 3a). The remaining study was conducted among patients with sleep disturbance during methadone maintenance and showed that 4-week Suanzaoren treatment reduced the global PSQI score by 1.8 points (95% CI 0.39, 3.21; P = .007) from baseline to 4 weeks, as compared with placebo. 34

Figure 3.

Short-term sleep improvements in Suanzaoren treatment versus controls. Effect of Suanzaoren treatment on short-term sleep improvement relative to (A) placebo and (B) active treatment controls.

Studies with active sleep treatments (3 trials, n = 201) were pooled separately. All included participants with a clinical diagnosis of insomnia disorder. In the pooled analysis, 4-week Suanzaoren treatment showed similar reductions in insomnia severity measured by the ISI (MD −1.12 points, 95% CI −3.87, 1.63; P = 0.43; I 2 = 68%), as compared to zopiclone, benzodiazepine, or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).35,36,42 Sensitivity analysis showed that statistical heterogeneity was reduced to an insignificant level (I 2 = 0%) after the removal of 1 study that compared Suanzaoren with Zopiclone in stroke patients with insomnia 35 (Figure 3b).

Two studies compared Suanzaoren and waitlist control on the improvement of insomnia or sleep disturbance. One study (n = 30) showed Suanzaoren treatment for 2 weeks was associated with significant improvements in the ISI score as compared to waitlist control among cancer patients with sleep disturbance (MD −5.60 points, 95% CI −7.90, −3.30; P < .01) 37 ; another study (n = 40) demonstrated that 4-week Suanzaoren compared to waitlist control led to significant reductions in the ISI score among general insomnia patients (MD −3.6 points, 95% CI −4.10, −3.10; P < .01). 43

Long-term sleep improvements

Three studies evaluated the long-term effect of Suanzaoren on insomnia severity measured by the ISI in the general population with primary insomnia. Two studies (n = 256) comparing 2- or 4-week Suanzaoren treatment with placebo found no long-term changes in the ISI score at 3 or 8 weeks, respectively.25,44 A third study (n = 40) showed that 4-week Suanzaoren treatment compared to waitlist control was associated with significant improvements in insomnia severity measured by the ISI at 8 weeks among patients with primary insomnia (P = .001). 43

Comorbid symptoms and quality of life

Compared with placebo, Suanzaoren was not associated with significant improvements in anxiety and depression, fatigue, or health-related quality of life in patients with insomnia or sleep disturbance during methadone maintenance.25,44 Compared with lorazepam, the Suanzaoren formula in combination with Zhi Zi Chi Tang led to significantly more improvement in anxiety (MD −6.4, 95% CI −16.08, −3.28; P = .001) after 4 weeks of treatment. 36 One study demonstrated that Suanzaoren treatment compared to CBT-I, was associated with significantly greater reductions in anxiety (MD −9.5, 95% CI −13.8, −5.2; P = .007) but not fatigue or quality of life at 4 weeks. 42 Among patients with cancer-related sleep disturbance, 37 Suanzaoren treatment was associated with significant improvements in fatigue (P = .002) but not depression or cognitive impairment compared to a waitlist control. Another study demonstrated that Suanzaoren treatment significantly improved quality of life as measured by the SF-36 scale in patients with insomnia at 4 and 8 weeks. 43

Safety

Two studies found that Suanzaoren did not lead to significant renal or liver toxicities.37,45 Five studies reported mild AEs possibly associated with Suanzaoren use, including sleep disruptions, dizziness, dry mouth, facial skin rash, urinary urgency, gastrointestinal discomfort, fatigue, and sweating25,34-36,44 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse Events Reported in Each Trial.

| Author | Adverse events | |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental arm* | Control arm* | |

| Birling et al 25 | 10/38 (dry mouth, frequent night waking, facial skin rash, urinary urgency); | Placebo: 16/47 (not detailed) |

| Chan et al 34 | 6/45 (diarrhea, sweating, dizziness, morning sleepiness); | Placebo: 3/45 (morning sleepiness and headache) |

| Dai et al 35 | 1/30 (dyspepsia) | Placebo: 0/30; Zopiclone: 6/30 (fatigue and nausea) |

| Hu et al 36 | 1/60 (diarrhea) | Lorazepam: 2/59 (dizziness) |

| Lee et al 37 | 2/15 (leg edema, dyspepsia) | Waitlist: 0/15 |

| Moon et al 42 | Not reported | |

| Mun et al 43 | No adverse events were reported | |

| Scholey et al 44 | 11/85 (not detailed) | Placebo: 14/85 (not detailed) |

| Song et al 45 | 24/120 (constipation, loss of appetite, dizziness, abnormal liver function, sexual dysfunction) | Lorazepam: 93/120 (constipation, loss of appetite, dizziness, abnormal liver function, sexual dysfunction) |

Data are presented as cases with AE/group sample size.

Discussion

Insomnia and sleep disturbance are common and negatively impact physical and psychological health. Our systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated improvements in patient-reported sleep quality with the herbal medicine Suanzaoren. In 9 randomized clinical trials that included 905 individuals with insomnia or sleep disturbance, Suanzaoren was well tolerated. There were consistent short-term improvements in sleep quality with Suanzaoren, with significantly greater improvements in insomnia severity compared to placebo or waitlist control and similar effects to benzodiazepine or CBT. However, Suanzaoren use was not associated with improvements in comorbid psychological or cognitive symptoms or quality of life, and results regarding long-term effects were mixed.

Thus far, no clinical practice guidelines on managing insomnia in adults have recommended herbal treatments, mainly due to the lack of rigorous evidence on safety and efficacy.47-49 However, challenges and limitations with conventional sleep approaches create a pressing need for new interventions. Guidelines recommend CBT-I as the first-line treatment for sleep difficulties, but there remain substantial barriers to its widespread use, including patient acceptance, resource availability, and insurance coverage.47,50 Sedative medications are effective for sleep difficulties but can have many side effects during long-term use. 51 With a growing number of people consuming herbal/natural products to aid their sleep, the shortcomings of current pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches create an opportunity for evidence-based CAM use in sleep care. We demonstrated that 4-week treatment with Suanzaoren was well tolerated in people with sleep difficulties and resulted in short-term improvements in insomnia severity, offering a potential CAM option for this critical problem.

Insomnia is often a long-lasting disorder, and our understanding of the long-term effects of Suanzaoren remains limited. 52 We found only 3 trials that measured the long-term use of Suanzaoren, and findings were mixed across studies. Unlike interventions that lead to persistent changes in sleep behaviors or beliefs (like CBT-I), Suanzaoren is an ethnopharmacological treatment that modulates sleep homeostasis.53,54 One would not expect it to improve sleep after therapy is stopped. The more likely long-term scenario would involve regular use of Suanzaoren over months or even years; we found no studies that have evaluated its safety or effectiveness over such a long period.

Further, the safety profile of Suanzaoren beyond major AEs remains unknown, whether used alone or as a main ingredient in composite formulas. Given its sedative properties, herbal-drug interactions with serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are possible and requirefurther research and monitoring in practice.26,55 Future studies are needed to determine the safety of long-term use of Suanzaoren and its impact on sleep quality.

Our study is unique in pooling data on psychological and cognitive symptoms that may complicate sleep disruptions,27,38,56 such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Relatively few studies have addressed these issues, and findings thus far are mixed. The absence of an apparent effect of Suanzaoren on comorbid psychological or cognitive symptoms may be attributed to the short intervention period in these studies. Individuals with insomnia also exhibit impairments in cognitive functions, including working memory, episodic memory, and some aspects of executive functioning. 57 Basic science studies suggest that spinosin—a flavonoid isolated from Suanzaoren 58 —may be protective against dementia 59 and could impact other cognitive problems. However, to our knowledge, no human data have evaluated the effect of Suanzaoren on cognitive impairments. Future studies should investigate the impact of more prolonged treatment with Suanzaoren on psychological symptoms and memory function.

The findings of our study can inform the design of rigorous trials of Suanzaoren for sleep health. Through pooled analysis of clinical trial data on Suanzaoren, we found a moderate effect size (SMD 0.58) for sleep quality improvements, which is essential to informing power estimations for future trials. We also identified promising efficacy data among patients with clearly defined insomnia rather than people with inconsistently defined sleep disturbances. These results highlight the need for studies to refine inclusion/exclusion criteria to reduce the heterogeneity of the study population so as to better characterize the effects of Suanzaoren. Further, because insomnia is usually chronic and persistent, clinical trials with a long-term treatment period are critical. We demonstrated that the efficacy signal is consistently linked to Suanzaoren treatment for 4 weeks, offering perspectives on the interventional course with which future trials could begin. In addition, current data are mainly sourced from Asian populations, so future trials should broaden their racial/ethnic coverage.

This study has several limitations. First, while our meta-analysis merged data from small studies, the inadequate statistical power associated with each study may increase the chance of imprecision. However, our results provide critical preliminary data to support short-term Suanzaoren use and can inform the design of larger randomized controlled trials. Second, the studies in our analysis presented limited information on comorbid diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. Whether Suanzaoren treatments extend emotional and cognitive improvements remains to be elucidated. Third, the current evidence base is built on subjective sleep measures. Future trials should incorporate objective sleep outcome measures like polysomnography or actigraphy to enhance the quality of evidence. Fourth, the small number of included studies precluded our evaluating publication bias. Our literature search was conducted in 3 international databases. Other databases, such as the CNKI and Psycarticles, needed to be covered when updating the review. Finally, given the diversity of Suanzaoren formulas, the ways in which different treatments contribute to sleep improvements remain unclear. Future studies should assess the efficacy of individual formulas to inform precision sleep care.

Our meta-analysis of patient-reported sleep data from randomized placebo-controlled trials shows that Suanzaoren is safe and likely to improve sleep with short-term use among individuals with sleep disturbances, particularly insomnia, but has an unclear effect on psychological or cognitive symptoms. Future large RCTs with longer-term follow-ups are needed to confirm efficacy. In the meanwhile, Suanzaoren can be a viable option for individuals seeking short-term sleep quality improvement in primary care, mainly when CBT-I is not available or desirable and pharmacological treatments are not adequately tolerated.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Deborah Korenstein is now affiliated to Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Data Availability: The study protocol and all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Korenstein discloses that her spouse serves on the scientific advisory board of Vedanta Biosciences and has equity interest, serves on the scientific advisory board of PFL-NYC, and provides consulting for Fibrion. Dr. Mao reports grants from Tibet CheeZheng Tibetan Medicine Co. Ltd. and from Zhongke Health International LLC outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported in part through the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, and by the Laurance S. Rockefeller Fund and the Translational and Integrative Medicine Research Fund, both at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Ethical Statement: No ethical approval was required. The whole study process involved no participation of human or nonhuman subjects.

ORCID iD: Mingxiao Yang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6514-3366

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6514-3366

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimäki M.Sleep epidemiology—a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1431-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerkhof GA.Epidemiology of sleep and sleep disorders in The Netherlands. Sleep Med. 2017;30:229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto T, Chin K.Prevalence of sleep disturbances: sleep disordered breathing, short sleep duration, and non-restorative sleep. Respir Investig. 2019;57:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salfi F, Lauriola M, D’Atri A, et al. Demographic, psychological, chronobiological, and work-related predictors of sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Mérette C.Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM.Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth T, Roehrs T.Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5:5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alattar M, Harrington JJ, Mitchell CM, Sloane P.Sleep problems in primary care: a north Carolina Family Practice Research Network (NC-FP-RN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savard J, Morin CM.Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:895-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Åkerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B.A prospective study of fatal occupational accidents–relationship to sleeping difficulties and occupational factors. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:69-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti JM, Monti D.Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:263-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, Perlis ML, Pack AI.Problems associated with short sleep: bridging the gap between laboratory and epidemiological studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:239-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth T.Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:S7-S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin MR, Vitiello MV.Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallander M-A, Johansson S, Ruigómez A, Rodríguez LAG, Jones R.Morbidity associated with sleep disorders in primary care: a longitudinal cohort study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwak A, Jacobs J, Haggett D, Jimenez R, Peppercorn J.Evaluation and management of insomnia in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181:269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bootzin RR, Epstein DR.Understanding and treating insomnia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:435-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agravat A.‘Z’-hypnotics versus benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2018;22:26-29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koffel E, Bramoweth AD, Ulmer CS.Increasing access to and utilization of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I): a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:955-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson NJ, Johnson LL, Nahin RL.Insomnia, trouble sleeping, and complementary and alternative medicine: analysis of the 2002 national health interview survey data. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1775-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra V, Harnett J, McIntyre E, Steel A, Wong K, Saini B.The prevalence and characteristics of complementary medicine use by Australians living with sleep disorders – results of a cross-sectional study. Adv Integr Med. 2020;7:14-22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng JY, Parakh ND.A systematic review and quality assessment of complementary and alternative medicine recommendations in insomnia clinical practice guidelines. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh A, Zhao K.Treatment of insomnia with traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;135:97-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein S, Becker S, Wolf U. Prescriptions of Chinese medicinal herbs in Switzerland: the example of suan zao ren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen). 2011. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20200226165035id_/https://boris.unibe.ch/52191/1/Poster_DKF2011_Klein_V2.0.pdf

- 25.Birling Y, Zhu X, Avard N, et al. Zao Ren An Shen capsule for insomnia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Sleep. 2022;45: zsab266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shergis JL, Hyde A, Meaklim H, Varma P, Da Costa C, Jackson ML.Medicinal seeds Ziziphus spinosa for insomnia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over, feasibility clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2021;57:102657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung W-F, Chung K-F, Poon MM-K, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:497-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie C-l, Gu Y, Wang W-W, et al. Efficacy and safety of Suanzaoren decoction for primary insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Q-H, Zhou X-L, Xu M-B, et al. Suanzaoren formulae for insomnia: updated clinical evidence and possible mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CY-C, Chen Y-F, Wu C-H, Tsai H-Y, et al. What is the effective component in suanzaoren decoction for curing insomnia? Discovery by virtual screening and molecular dynamic simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao J, Li SP, Yang FQ, Li P, Wang YT.Simultaneous determination of saponins and fatty acids in Ziziphus jujuba (Suanzaoren) by high performance liquid chromatography-evaporative light scattering detection and pressurized liquid extraction. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1108:188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang G, Mao S, Tam W, Tam G, Tam C.Survey of biological active molecule in the Chinese herbal formula- Suan Zao Ren Tang in treating insomnia. FASEB J. 2009;23:902.913. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang B, Zhang A, Sun H, et al. Metabolomic study of insomnia and intervention effects of Suanzaoren decoction using ultra-performance liquid-chromatography/electrospray-ionization synapt high-definition mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2012;58:113-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan Y-Y, Chen Y-H, Yang S-N, Lo W-Y, Lin J-G.Clinical efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine, Suan Zao Ren Tang, for sleep disturbance during methadone maintenance: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:710895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai N, Li Y, Sun J, Li F, Xiong H.Self-designed Ningxin Anshen Formula for treatment of Post-ischemic stroke Insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. 2020;11:537402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu L-L, Zhang X, Liu W-J, Li M, Zhang Y-H.Suan zao ren tang in combination with Zhi Zi Chi Tang as a treatment protocol for insomniacs with anxiety: a randomized parallel-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:913252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JY, Oh HK, Ryu HS, Yoon SS, Eo W, Yoon SW.Efficacy and safety of the traditional herbal medicine, Gamiguibi-tang, in patients with cancer-related sleep disturbance: a prospective, randomized, wait-list-controlled, pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:524-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ni X, Shergis JL, Zhang AL, et al. Traditional use of chinese herbal medicine for insomnia and priorities setting of future clinical research. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:8-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang M, Sun M, Du T, et al. The efficacy of acupuncture for stable angina pectoris: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28:1415-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon S-Y, Jerng UM, Kwon O-J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of Cheonwangbosimdan (Tian Wang Bu Xin Dan) versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer patients: a randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, pilot trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420935643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mun S, Lee S, Park K, Lee S-J, Koh B-H, Baek Y.Effect of traditional east Asian medicinal herbal tea (HT002) on insomnia: a randomized controlled pilot study. Integr Med Res. 2019;8:15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scholey A, Benson S, Gibbs A, Perry N, Sarris J, Murray G.Exploring the effect of lactium™ and Zizyphus complex on sleep quality: a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2017;9:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song M-F, Chen L-Q, Shao Q-Y, Hu L-L, Liu W-J, Zhang Y-H.Efficacy and safety of Jiawei Suanzaoren decoction combined with lorazepam for chronic insomnia: a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:3450989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng C-W, Wu T-X, Shang H-C, et al. CONSORT extension for Chinese herbal medicine formulas 2017: recommendations, explanation, and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:112-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morin CM, Inoue Y, Kushida C, Poyares D, Winkelman J.Endorsement of European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia by the World Sleep Society. Sleep Med. 2021;81:124-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg R, Citrome L, Drake CL.Advances in the treatment of chronic insomnia: a narrative review of new nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies. Neuropsychr Dis Treat. 2021;17:2549-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madari S, Golebiowski R, Mansukhani MP, Kolla BP.Pharmacological management of insomnia. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18:44-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morin CM, Benca R.Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012;379:1129-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Du Y, He B, Li Q, He J, Wang D, Bi K.Simultaneous determination of multiple active components in rat plasma using ultra-fast liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry and application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of Suan-Zao-Ren decoction and Suan-Zao-Ren granule. J Sep Sci. 2017;40:2097-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang K, Yan G, Zhang A, Sun H, Wang X.Recent advances in pharmacokinetics approach for herbal medicine. RSC Advances. 2017;7:28876-28888. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeung W-S.Suanzaorentang and Serotonin Syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:113-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leach MJ, Page AT.Herbal medicine for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;24:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fortier-Brochu É, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shergis JL, Ni X, Sarris J, et al. Ziziphus spinosa seeds for insomnia: a review of chemistry and psychopharmacology. Phytomedicine. 2017;34:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko SY, Lee HE, Park SJ, et al. Spinosin, a C-Glucosylflavone, from Zizyphus jujuba var. spinosa ameliorates Aβ1–42 oligomer-induced memory impairment in mice. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2015;23(2):156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-ict-10.1177_15347354231162080 for The Herbal Medicine Suanzaoren (Ziziphi Spinosae Semen) for Sleep Quality Improvements: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by Mingxiao Yang, Hui Wang, Yi Lily Zhang, Furong Zhang, Xiaotong Li, Soo-Dam Kim, Yalan Chen, Jiyao Chen, Susan Chimonas, Deborah Korenstein and Jun J. Mao in Integrative Cancer Therapies