Abstract

Protein ubiquitination is a widespread, multifunctional, posttranslational protein modification, best known for its ability to direct protein degradation via the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS). Ubiquitination is also reversible, and the human genome encodes over 90 deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), many of which appear to target specific subsets of ubiquitinated proteins. This review focuses on the roles of DUBs in neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). We present the current genetic evidence connecting 12 DUBs to a range of NDDs and the functional studies implicating at least 19 additional DUBs as candidate NDD genes. We highlight how the study of DUBs in NDDs offers critical insights into the role of protein degradation during brain development. Because one of the major known functions of a DUB is to antagonize the UPS, loss of function of DUB genes has been shown to culminate in loss of abundance of its protein substrates. The identification and study of NDD DUB substrates in the developing brain is revealing that they regulate networks of proteins that themselves are encoded by NDD genes. We describe the new technologies that are enabling the full resolution of DUB protein networks in the developing brain, with the view that this knowledge can direct the development of new therapeutic paradigms. The fact that the abundance of many NDD proteins is regulated by the UPS presents an exciting opportunity to combat NDDs caused by haploinsufficiency, because the loss of abundance of NDD proteins can be potentially rectified by antagonizing their UPS-based degradation.

The modification of protein function through covalent attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) via lysine (K) residues is a widespread event involved in every eukaryotic cellular process (1). As a posttranslational mechanism, ubiquitination is used where rapid changes in protein and cell function are essential, for example, enabling signaling cascades, cell cycle changes, cell differentiation, and plasticity (2,3). The specificity of protein ubiquitination is bestowed via approximately 600 enzymes called E3 ubiquitin ligases, that dictate which, when, where, and how proteins are ubiquitinated (1). Ubiquitination is reversible, and deubiquitination is also critically important. Only approximately 90 deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are currently known, but recent identification of noncanonical DUB families suggests that others may exist. This comparatively small number of DUBs are charged with the challenge of precisely regulating all ubiquitinated proteins (4). DUBs target many substrates and function as regulators of cell, developmental, and disease processes (5,6).

Ubiquitination is a diverse and multifunctional posttranslational modification (7). Proteins can be monoubiquitinated or polyubiquitinated, the latter involving sequential attachment of additional Ub moieties to either the N-terminal methionine (M1) or one of seven internal lysine residues of Ub itself (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63). The different Ub chain lengths and linkage types provide a “ubiquitin code” that is deciphered by a host of Ub-binding receptors, which dictate downstream outcomes (7,8). Ubiquitination can facilitate protein-protein interactions, protein trafficking, subcellular localization, and enzymatic activity, among other outcomes, in addition to its well-established role in directing protein degradation. Classically, the attachment of a poly-Ub chain of four or more K48- or K11-linked Ub molecules targets proteins to the 26S proteasome for degradation, a process known as the Ub proteasome system (UPS) (1). In addition, ubiquitination of proteins trafficked through vesicular systems instructs their delivery to the lysosome for degradation (9). In turn, many DUBs antagonize these degradation pathways by removing Ub from specific subsets of proteins in a precise and regulated manner (10).

DUBs are either cysteine- or metalloproteases and divided into seven subfamilies (11). The sole metalloprotease subfamily is the Jad1/Pad/Mpn domain–containing metalloenzymes (JAMMs). The cysteine protease subfamilies include the ubiquitin specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Joseph disease domain proteases (MJDs), Ub C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Josephins motif interacting with Ub-containing novel DUB family (MINDYs), and the zinc-finger and UFSP domain protein (ZUFSP) (11). The sole function of some DUBs is to maintain the free Ub pool in cells, such as UCHL1, which releases free Ub from newly synthesized Ub polymers, and USP14 and UCHL3, which recycle Ub from proteins at the proteasome (11). However, many DUBs are known to target specific sets of ubiquitinated proteins derived via affinities for particular Ub chain lengths or linkage types (e.g., OTU family members) or auxiliary protein-protein interaction motifs (e.g., USP family members) (11–17).

The process and functions of protein ubiquitination and deubiquitination and their roles in neurodegenerative disorders have been reviewed in depth (1,4,7,18,19). Here, we focus on the role of DUBs in the developing brain. We describe genetic evidence from human and mouse implicating DUBs in a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) including developmental delay (DD); intellectual disability (ID); epilepsy; motor, speech, language, and visual difficulties; and behavioral disturbances. We highlight how NDD DUB substrates provide insight into the pathological mechanisms converging on loss of protein abundance and synthesize this knowledge to discuss therapeutic paradigms relevant to individuals with NDD DUB mutations and, more broadly, to NDDs caused by haploinsufficiency.

DUBs IN NDDs

Mutations in 12 DUBs are currently known to cause NDDs (Table 1). Half of these belong to the USP subfamily. Heterozygous loss of function (LoF) mutations (encompassing gene deletion, nonsense, and frameshift mutations) of USP7 have been reported in 23 individuals with DD/ID, speech delay, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), impulsivity, compulsivity, and aggression (20,21). Brain imaging revealed decreased white matter and thinning of the corpus callosum. A thin cortex and reduced brain size is observed in brain-specific Usp7 knockout mice and attributed to elevated apoptosis (22). Mutations in the X chromosome gene Usp9x cause an X-linked NDD in hemizygous males (23–25) and also an NDD syndrome in heterozygous females (26,27). This phenomenon is resolved by the fact that males are affected by hypomorphic (i.e., partially nonfunctional) missense mutations, which are tolerated in heterozygous female carriers (23,24), while females are affected by de novo heterozygous complete LoF mutations (26). Because USP9X escapes X-inactivation, the heterozygous LoF alleles result in an unusual state of female X-linked haploinsufficiency (26). The core neurologic phenotypes caused by USP9X mutations in females (33 individuals) and males (16 individuals) are shared, including DD/ID, delayed speech, movement disorders, and behavioral problems including ASD (27). Frequent brain malformations include agenesis of the corpus callosum and ventriculomegaly (27). Usp9x brain-specific knockout mice show NDD hallmarks, including defective learning, abnormal communication and socialization, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and ventriculomegaly (28–31). These mice display defects in neural stem cell (NSC) polarity, proliferation, and differentiation and neuronal cell migration, growth, and connectivity (23,28–30,32–34). De novo heterozygous LoF mutations of USP15 have been identified in 11 individuals with ASD (35,36). Intriguingly, Usp15 knockout mice display altered neuroinflammatory responses that potentially contribute to the NDD phenotype (37). Biallelic LoF mutations in USP18 have been identified in 6 individuals with pseudo-TORCH syndrome (38,39). TORCH syndrome results from placental-to-fetal microbe transmission, and pseudo-TORCH syndrome describes neonates with TORCH features in the absence of infection. Brain characteristics include hemorrhage, microcephaly, white matter loss, cerebral atrophy, and calcifications. Together with other congenital features, neonatal lethality results. A hallmark of pseudo-TORCH syndrome is hyperactivation of the brain’s innate immune system. USP18 is a unique DUB that cleaves the Ub-like molecule ISG15 from substrates to limit interferon-mediated inflammation (38,40). A hyperactive innate immune response occurs in Usp18 knockout mice, which feature hydrocephalus and reduced life span (41). Two hemizygous LoF mutations affecting 4 individuals with ID, speech, and behavioral problems have been identified in the X chromosome gene USP27X (42). Two additional individuals with NDD have been identified with hemizygous deletions involving USP27X (43). Knockout mice have not been generated; however, overexpression of Usp27x inhibits neurogenesis in mice (44). Biallelic LoF mutations in USP45 cause Leber congenital amaurosis, a severe form of inherited retinal dystrophies that results in irreversible childhood blindness (45). Usp45 knockout mice feature severely disrupted eye function caused by loss of photoreceptor cone cells (45).

Table 1.

DUBs Involved in NDDs

| DUB Class | Gene | Inheritance | NDD Phenotype (OMIM) | Other Disease Associations | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | USP7 | AD | Hao-Fountain syndrome (HAFOUS) (616863) | Cancer, neurodegeneration | (20–22) |

| USP9X | XL | Males: Mental retardation X-linked family 99 (MRX99) (300919) Females: USP9X-female syndrome/Mental retardation X-linked family 99-female syndrome (MRX99F) (300968) |

Cancer, neurodegeneration | (23–34) | |

| USP15 | AD | Autism spectrum disorder (NA) | Cancer | (35–37) | |

| USP18 | AR | Pseudo-TORCH syndrome 2 (617397) | Cancer, autoimmune | (38–41) | |

| USP27X | XL | Mental retardation X-linked family 105 (MRX105) (300984) | Cancer | (42–44) | |

| USP45 | AR | Leber congenital amaurosis 19 (618513) | Cancer, inflammatory bowel disease | (45) | |

| OTU | OTUD5 | XL | Multiple congenital anomalies with neurodevelopmental syndrome – X-linked (MCAND) (301056) | Cancer, | (46–48) |

| OTUD6B | AR | Intellectual developmental disorder with dysmorphic facies, seizures, and distal limb anomalies (IDDFSDA) (617452) | Cancer | (49–51) | |

| OTUD7A | AD | Microdeletion 15q13.3 (612001) | Cancer | (52–56) | |

| JAMM | STAMBP | AR | Microcephaly-capillary malformation syndrome (MICCAP) (614261) | Cancer, neurodegeneration | (57,58) |

| MJD | ATXN3 | AD | Machado-Joseph disease type I (109150) |

Cancer, neurodegeneration | (66,67) |

| UCH | UCHL1 | AR | Spastic paraplegia 79–autosomal recessive (SP79-AR) (615491) | Neurodegeneration | (59–65,70) |

List of known NDD DUBs. Inheritance patterns shown are AD, AR, and XL. Phenotypes are referenced with OMIM entries.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; DUB, deubiquitinating enzyme; JAMM, Jad1/Pad/Mpn domain-containing metalloenzymes; MJD, Machado-Joseph deubiquitinase; NA, not applicable; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; OTU, ovarian tumor proteases; UCH, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase; USP, ubiquitin specific protease; XL, X chromosome–linked.

Mutations in three OTU subfamily members cause NDDs (Table 1). Hemizygous missense mutations in the X chromosome gene OTUD5 cause a male-limited NDD named multiple congenital anomalies-neurodevelopmental syndrome. Ten unique missense variants affecting 26 individuals have been described (46–48). Mutations are hypomorphic, and outcomes range from DD to neonatal lethality. Common features include brain malformations (ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus), congenital heart disease, and craniofacial and genitourinary defects. Both knockout and disease-relevant knockin mouse models are embryonic lethal, while induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models show reduced differentiation into NSCs (47). Biallelic LoF mutations in OTUD6B have been discovered in 15 individuals featuring ID/DD, seizures, absent speech, hypotonia, and microcephaly (49–51). Variable brain structural abnormalities include white matter volume loss, corpus callosum dysgenesis, and dilatation of lateral ventricles. Knockout mice are nonviable, but embryos displayed reduced size with brain and organ abnormalities (49). OTUD7A was identified as the critical gene responsible for brain phenotypes associated with heterozygous 15q13.3 deletions found across hundreds of individuals with NDDs including ID, ASD, epilepsy, and schizophrenia (52). In support, deletions involving only OTUD7A, as well as OTUD7A LoF mutations, have been identified in individuals with NDDs (53,54). Furthermore, both the syntenic 15q13.3 microdeletion mouse model and the Otud7a knockout mouse model recapitulate the human 15q13.3 syndrome, and re-expressing OTUD7A in cortical neurons from the microdeletion model completely rescues neuronal dendritic spine and branching defects (55,56).

Mutations in members of the JAMM-containing metalloenzyme, UCH, and MJD domain protease subfamilies also cause NDDs (Table 1). Homozygous mutations in STAMBP have been identified in 19 individuals with microcephaly-capillary malformation characterized by microcephaly with progressive cortical atrophy, intractable epilepsy, DD, and small capillary malformations on the skin (57). Knockout mice exhibit neuronal damage and elevated apoptosis in the hippocampus (58). Homozygous missense and splice-site mutations in the UCH subfamily member UCHL1 have been reported in 10 cases with spastic paraplegia-79, an early-onset neurodegenerative syndrome (59–62). This childhood syndrome features blindness, cerebellar ataxia, nystagmus, dorsal column dysfunction, and spasticity. The progressive ataxia, muscular, and lethal phenotypes are observed in mutant and knockout mouse models (63,64), which display nerve fiber loss, axonal swelling, degeneration in the spinal cord, and impaired neuromuscular denervation and synaptic transmission (65). Finally, a polyglutamine-coding CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion in the MJD domain protease subfamily member ATXN3 causes an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder called spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (SCA3), which can have infantile or childhood onset called SCA type 1 (66). SCA type 1 is a progressive neuropathy causing severe movement disturbances (ataxia, weakness, dysarthria, spasticity), visual defects, and cognitive decline, culminating in death in early adulthood (66). A polyglutamine-expanded Atxn3 knockin mouse displays adult-onset motor decline; however, a larger expansion of the polyglutamine tract reflective of SCA type 1 is likely required to better model earlier onset (66). Nonetheless, this model reveals accumulation and aggregation of ATXN3 in adult brain cells, neuropathology in both neurons and glia, cerebellar degeneration with loss of Purkinje cells, and evidence of neuroinflammation (67). Collectively, these data highlight that compromised function of DUBs caused by LoF or hypomorphic mutations can cause NDDs, and current mouse models of these disorders are providing valuable insight into the molecular, cell, and physiological mechanisms of pathology.

CANDIDATE DUBs IN NDDs

Recent genetic and functional data have identified at least 19 additional DUBs as NDD gene candidates (Table 2). The chromosome 21 gene USP16 is implicated in Down syndrome. In the Ts65Dn mouse model, which is trisomic for 132 human chromosome 21 gene orthologs, trisomy of USP16 was shown to drive NSC defects (68). Duplications of <1 Mb of sequence including USP16 have also been identified in 2 individuals with NDDs (43). A homozygous missense mutation in USP11 has been identified in an individual with ID and brain malformation (69). Conditional brain knockout of Usp11 in mice causes behavioral, learning, and memory defects underpinned by defective generation and migration of cortical neurons (69). Unlike wild-type Usp11, re-expression of the Usp11 NDD variant in the knockout model failed to rescue these defects, establishing LoF of USP11 as the pathogenic mechanism. Three other DUBs including UCHL1 (described above), OTUD7B, and OTUB1, have been shown to interact with polymorphisms (via chromatin conformation capture and expression quantitative trait loci analysis) identified in genome-wide association studies incorporating multiple psychiatric and behavioral disorders (70). In support, OTUD7B depletion in NSCs induces differentiation (71). USP46 and USP8 are involved in synaptic transmission. Both localize to the postsynaptic density and facilitate recycling of AMPA receptors back to the synaptic membrane (72,73). Usp46 hypomorphic and knockout mice show depression-like phenotypes (74,75), while Usp8 knockout mice are embryonic lethal (76). USP14 is also involved in synapse development. Hypomorphic mice have an early-onset progressive ataxic phenotype associated with defects in synaptic transmission (77), while knockout results in additional NDD phenotypes (78). In utero knockdown of USP1, USP4, and USP20 in the mouse cerebellum disrupts granule neuron morphogenesis, while knockdown of USP30 and USP33 disrupts granule neuron migration (79). CYLD also regulates axonal outgrowth, structure of the postsynaptic density, and synaptic transmission (80,81). Additional UCH family members are also implicated in brain development. Knockout of Uchl3 in mice leads to learning, memory, and synaptic transmission defects, while knockout of Uchl5 causes lethality with severe defects in embryonic brain development (82,83). Finally, mutation of the DUB Otulin also has a severe NDD phenotype in mice (84). LoF of any of these candidate NDD DUBs may plausibly give rise to a human NDD.

Table 2.

Additional DUBs That Regulate Neurodevelopment

| DUB Class | Gene | Inheritance | NDD Phenotype (OMIM) | Other Disease Associations | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | USP1 | n/a | n/a | Cancer, Fanconi anemia | (79) |

| USP4 | n/a | n/a | Cancer | (79) | |

| USP8 | n/a | n/a | Cancer, Cushing disease | (73,76) | |

| USP11 | XL | Intellectual disability | Cancer | (69) | |

| USP14 | n/a | n/a | Cancer, neurodegeneration | (77,78) | |

| USP16 | AD/IC | Down syndrome (190685) | Cancer | (43,68) | |

| USP20 | n/a | n/a | Cancer | (79) | |

| USP30 | n/a | n/a | Neurodegeneration | (79) | |

| USP33 | n/a | n/a | Cancer | (79) | |

| USP46 | n/a | n/a | n/a | (72,74,75) | |

| CYLD | n/a | Frontotemporal dementia and/or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 (FTDALS8) (619132) | Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, cylindromatosis, trichoepithelioma, cancer, neurodegeneration | (80,81) | |

| OTU | ALG13 | XL | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 36 (DEE36) (300884) | Congenital disorder of glycosylation | (85) |

| OTUD7B | Complex | Neuropsychiatric disorder | Cancer | (70,71) | |

| OTUB1 | Complex | Neuropsychiatric disorder | Cancer | (70) | |

| OTULIN | n/a | n/a | Autoinflammatory disease | (84) | |

| JAMM | PRPF8 | AD | Retinitis pigmentosa 13 (600059) | Glaucoma, cancer | (90,91) |

| EIF3F | AR | Mental retardation–autosomal recessive 67 (MR-AR67) (618295) |

Cancer | (86–89) | |

| UCH | UCHL3 | n/a | n/a | Cancer | (82) |

| UCHL5 | n/a | n/a | Cancer | (83) |

List of candidate NDD DUBs. Inheritance patterns shown are AD, AR, XL, and IC. Phenotypes are referenced with OMIM entries.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; DUB, deubiquitinating enzyme; IC, isolated case; JAMM, Jad1/Pad/Mpn domain-containing metalloenzymes; n/a, not applicable; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; OTU, ovarian tumor proteases; UCH, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase; USP, ubiquitin specific protease; XL, X chromosome–linked.

In addition to the above candidate NDD DUBs, mutations in ALG13, EIF3F, and PRPF8 are known to cause NDDs, but their DUB activity remains speculative. Over 50 individuals, predominantly female, have been identified with de novo missense variants in the X chromosome gene ALG13, causing an NDD featuring an infantile epileptic encephalopathy with DD/ID and hypotonia (85). Although ALG13 is best known as a uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, the individuals display no biomarkers of congenital disorders of glycosylation, casting intrigue over the relevance of its uncharacterized OTU deubiquitinase domain (85). A recurrent autosomal recessive mutation in EIF3F also causes an NDD. The homozygous p.Phe232Val mutation has been identified in 29 individuals (86,87) with DD/ID, seizures, behavioral disturbances, hearing loss, hypertonia, eye abnormalities, and sleeping problems. EIF3F is a translational initiation factor (88), but its deubiquitinating activity has not been well established (89). Mutations in PRPF8 are a well-known cause of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disorder that can present in childhood as early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. PRPF8 encodes a spliceosome factor, and although it harbors a JAMM domain–containing metalloenzyme domain, its deubiquitinating activity has yet to be displayed (90,91).

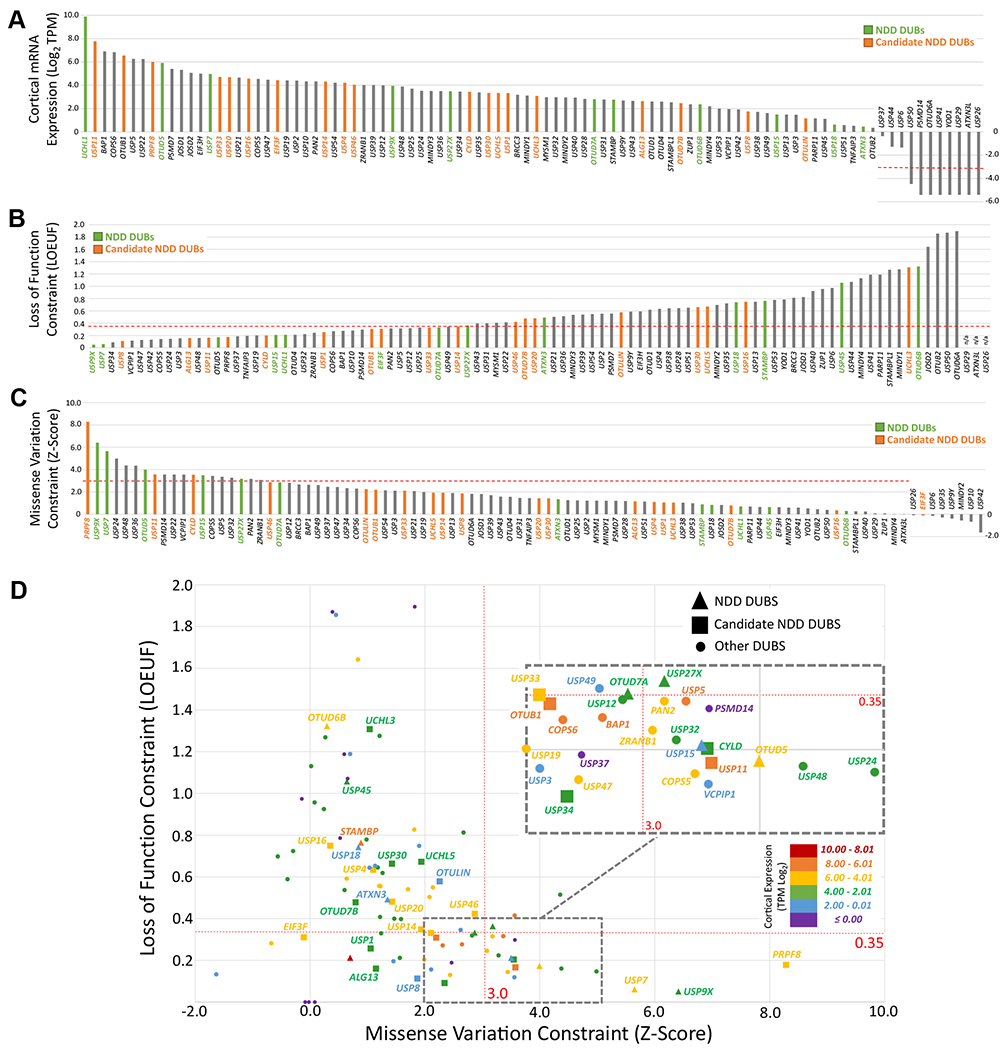

The repositories of transcriptomes, genomes, and exomes can be leveraged to prioritize candidate DUBs in NDDs, with the prediction that an NDD gene should be highly expressed in the brain and intolerant to genetic variation. Cortical expression of DUBs derived from the Genotype-Tissue Expression database (92) reveals that most of the ~90 DUBs are expressed in the cortex, but some to a much higher degree than others (Figure 1A; Table S1). The gnomAD V2 resource of genome variation of individuals devoid of NDDs enables predictions of which DUBs are intolerant to genetic variation (Figure 1B, C; Table S1) (93). Combining this information provides a rationale to prioritize investigations on candidate NDD DUBs including USP11, CYLD, and PRPF8, and identifies potential new NDD DUBs such as ZRANB1, PAN2, COPS5, VCPIP1, USP5, USP24, and USP48 (Figure 1D). In aggregate, these genetic and functional data further highlight the essential requirements of DUB function during brain development and suggest that more NDD DUBs are on the verge of discovery.

Figure 1.

Brain expression and mutational constraint of DUBs. Metrics for NDD DUBs and candidate NDD DUBs are highlighted. (A) Cortical mRNA expression of DUBs. mRNA expression was extracted from the GTEx database and displayed as log2 TPM. Low expression is defined as < −3.32 (1 transcript per 10,000,000 reads). (B, C) Mutational constraint of DUBs. Metrics for intolerance to loss of function variants (B) and missense variants (C) were extracted from gnomAD. (B) Stringent intolerance to loss of function is defined as a LOEUF score < 0.35 (93). (C) Stringent intolerance to missense variation is defined as a Z-score > 3 (93). (D) Combined analysis of brain expression and mutational constraint. Note that all known NDD DUBs and candidate NDD DUBs are expressed in the cortex. Only 4 of 12 NDD DUBs meet the criteria of Z-score > 3 and LOEUF score < 0.35 (USP9X, USP7, USP15, and OTUD5), which cause dominant or X-linked NDDs as predicted for intolerant alleles. These data therefore support several candidate NDD and other DUBs as potentially dominant drivers of NDDs, being defined as highly intolerant to variation and highly expressed in the cortex. DUBs, deubiquitinating enzymes; gnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; LOEUF, loss of function observed/expected upper bound fraction; mRNA, messenger RNA; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; TPM, transcripts per kilobase million.

MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR FUNCTIONS OF NDD DUBs

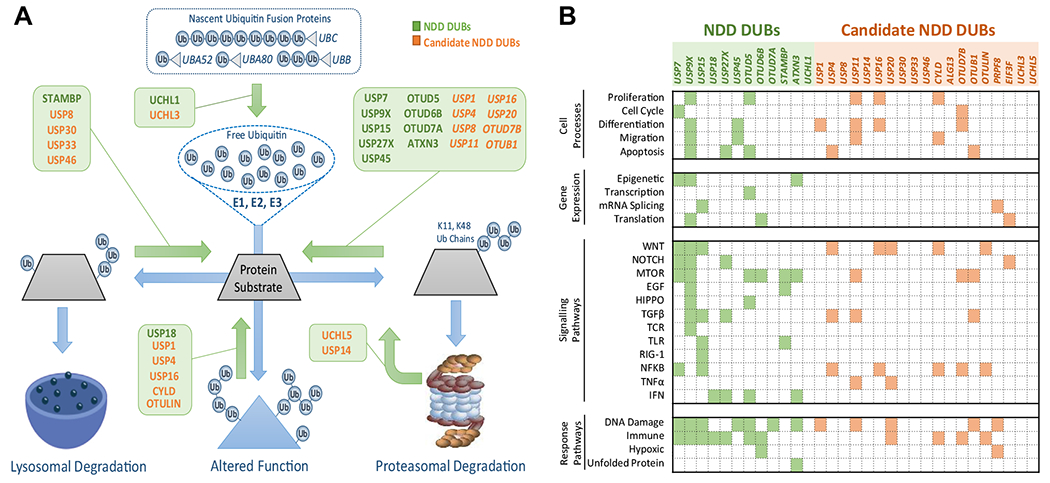

Most NDD DUBs are best known for their ability to antagonize protein degradation via the UPS (Figure 2A). The major exceptions are UCHL1, STAMBP, and USP18. UCHL1 functions to maintain free Ub by releasing it from newly translated multimeric Ub peptides, ribosomal-Ub fusion peptides, and other small Ub adducts (94). Loss of UCHL1 function thus results in a global reduction in the efficiency of ubiquitination machinery (94). The major function of STAMBP is to antagonize vesicular trafficking of membrane-associated proteins to the lysosome. It removes mono- and K67-linked Ub (95), which are common membrane receptor protein internalization signals that instruct delivery to the lysosome for degradation. STAMBP-mediated deubiquitination of cargo redirects their trafficking back to the plasma membrane for ongoing signaling (95), and as such, STAMBP mutations likely cause pathology via defective signaling of receptors in the developing brain. USP18 cleaves the Ub-like molecule ISG15 from protein targets, a modification not directly linked to the UPS (40). Instead, protein ISGylation promotes protein-protein interactions or enzyme activity and functions specifically in the innate immune response (40). USP18 therefore likely affects central nervous system development in a non–brain cell autonomous manner. The remaining NDD DUBs including USP7, USP9X, USP15, USP27X, USP45, OTUD5, OTUD6B, OTUD7A, and ATXN3, are best characterized for their ability to antagonize the UPS through deubiquitination of their substrates. This function is not exclusive, as demonstrated by the USP family members, which generally show a broad spectrum of Ub chain length and linkage preferences (11). For example, although USP9X protects the majority of its substrates from the UPS by removing K48- and K11-linked Ub, it also displays activity against other Ub linkages and chain lengths and regulates processes including vesicular trafficking, subcellular localization, enzyme activity, protein interactions, and chromatin architecture (32,96). Regarding cellular functions of the NDD DUBs, most of the limited knowledge available derives from the study of cancer. The emerging landscape of DUB functions is broad and aligns with use of ubiquitination in dynamic processes including signaling cascades, gene expression and cell proliferation, differentiation, and response mechanisms (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Molecular and cellular roles of NDD DUBs. (A) Major known roles of NDD DUBs and candidate NDD DUBs in the Ub system. The process of protein ubiquitination is shown in blue. The sequential activity of E1, E2, and E3 Ub ligases conjugate Ub to substrates. Three major outcomes are shown including 1) trafficking of vesicular proteins to the lysosome via endocytic, mitophagy, and autophagy pathways; 2) alteration to protein function, e.g., enzyme activity, protein localization, or protein interactions; and 3) driving proteasomal degradation. Diverse Ub chain topologies can drive different outcomes, but chains of four or more K48-linked or K11-linked Ubs direct proteasomal degradation. NDD DUBs predominantly antagonize these outcomes by removing Ub. Note that DUBs can also stimulate Ub processes by contributing to the free Ub pool (e.g., UCHL1). (B) Current knowledge of the major cellular roles of NDD DUBs and candidate NDD DUBs. The roles of many of these DUBs are poorly characterized. DUB, deubiquitinating enzyme; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IFN, interferon; mRNA, messenger RNA; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; NFKB, nuclear factor-κB; TGFβ, transforming growth factor β; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α; Ub, ubiquitin.

NDD DUBs CONTROL ABUNDANCE OF PROTEINS ENCODED BY NDD GENES

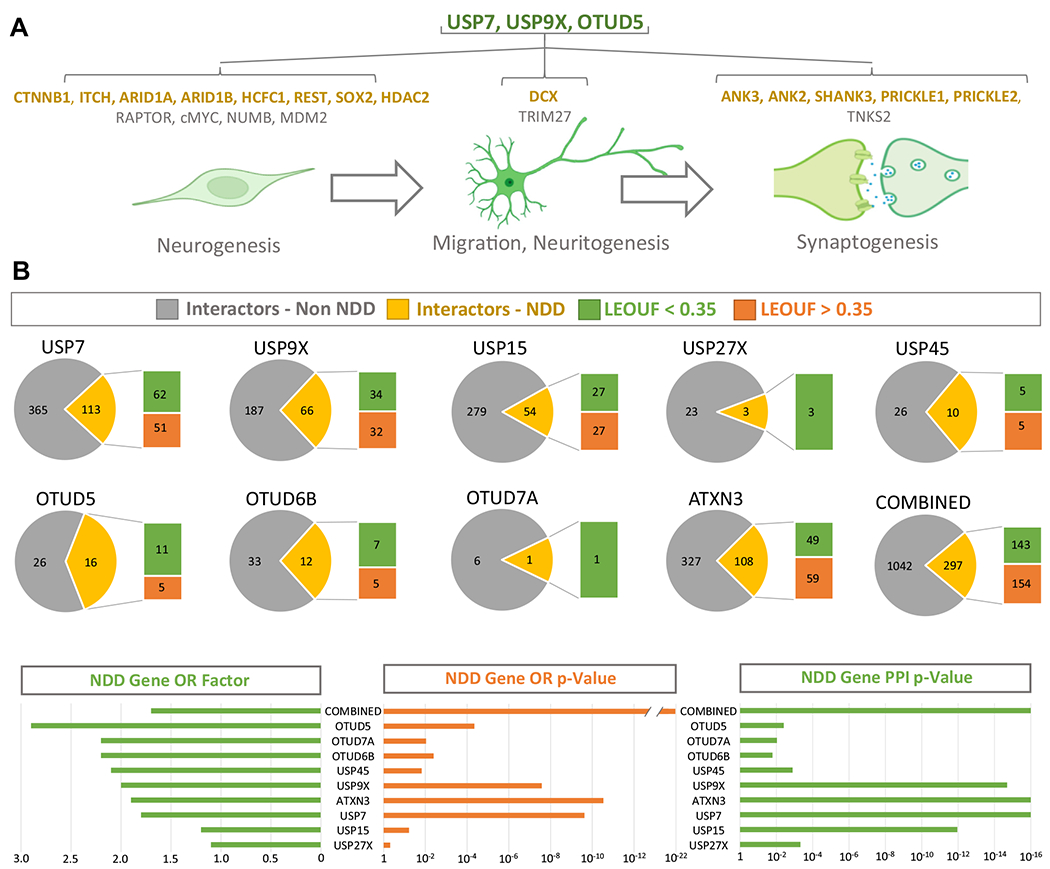

The remainder of this review focuses on the function of NDD DUBs in the UPS and explores mechanisms that converge on the regulation of protein abundance in the developing brain. For descriptions of non-UPS roles of DUBs in the brain, the reader is directed to a recent review (97). USP9X, USP7, and OTUD5 are currently the only NDD DUBs to have protein substrates identified in the context of brain development (Figure 3A). USP9X deubiquitination of the mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) signaling component RAPTOR protects it from proteasomal degradation, thus promoting mTOR signaling and proliferation of NSCs (34). Other substrates depleted in Usp9x knockout embryonic brains include CTNNB1 (WNT signaling), ITCH, and NUMB (NOTCH signaling), and these signaling pathways are defective in USP9X-deficient NSCs (31). CTNNB1 also functions in cell adhesion, and NSC adhesion and polarity is defective in the absence of USP9X (29,33). USP9X also binds DCX, a master regulator of neuronal migration (23,98). C-terminal missense mutations in USP9X that cause NDDs result in loss of this interaction and reduced neuronal migration. Conversely, missense mutations in DCX that cause NDDs specifically disrupts interaction with USP9X (23,98). USP9X regulates additional substrates in developing neuronal synapses. USP9X deubiquitination of ANK3 (and other synaptic proteins including ANK2, SHANK3, and TNKS2) is required to antagonize its proteasomal degradation and is essential for synapse formation (30). Some USP9X mutations causing NDDs disrupt this interaction (30). The degradation of PRICKLE1 and PRICKLE2 is also antagonized by USP9X in the synapse and is required for control of neuronal excitability (25). A USP9X mutation in a male with epilepsy disrupts interaction with PRICKLE1 (25). Thus, USP9X is required to maintain substrate abundance to control different aspects of brain development that appear relevant to the pathology of NDDs.

Figure 3.

NDD DUBs control the dosage of NDD proteins in cells of the developing brain. (A) Overview of the known NDD DUB substrates identified in the context of cells of the developing brain and the cellular processes they regulate. (B) Interactomes of NDD DUBs. All known DUB-interacting proteins were extracted using the BioGRID resource. The number of proteins encoded by NDD genes within each NDD DUB interactome is shown (yellow) and the OR factor provided to highlight enrichment (p value represents an exact hypergeometric probability test). The connectivity of the NDD interactome components (PPI p value) were assessed using STRING. The proportion of haploinsufficient NDD proteins within the NDD DUB interactomes is shown (green) and defined using the gnomAD metric LOEUF score < 0.35. BioGRID, Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets; DUBs, deubiquitinating enzymes; gnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database; LOEUF, loss of function observed/expected upper bound fraction; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; OR, overrepresentation; PPI, protein-protein interaction; STRING, Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins.

Similar to USP9X, the NDD DUBs USP7 and OTUD5 also regulate brain development by promoting substrate abundance. USP7 protects the transcriptional repressor REST and transcriptional activators c-MYC and SOX2 from proteasomal degradation in NSCs to maintain an undifferentiated state (99). In hypothalamic neurons, USP7 protects TRIM27 from proteasomal degradation. In turn, TRIM27 opposes the delivery and degradation of endosomal cargo at the lysosome (20). USP7 also regulates the proteasomal degradation of the p53 E3-ligase MDM2. In the developing brains of mice lacking USP7, p53 levels become elevated, leading to widespread apoptosis (20). Studies of OTUD5 mutant iPSCs and NSCs revealed that it protects the chromatin regulators ARID1A, ARID1B, HCFC1, and HDAC2 from proteasomal degradation associated with decreased capacity of iPSCs to differentiate into NSCs. Substrates of the remaining NDD DUBs are undetermined in the context of the developing central nervous system.

Although knowledge of NDD DUB substrates in the developing brain is currently limited, it is striking that 70% of the known substrates are themselves encoded by NDD genes (USP9X/USP7/OTUD5 = 14/20) (Figure 3A). Because the genes encoding these substrates cause NDDs through LoF and DUBs promote the function of these genes by promoting the abundance of their encoded proteins, it follows that the function of NDD DUBs may converge to maintain the abundance of NDD protein networks. Support of this mechanism is derived by interrogating NDD DUB interactomes assembled en masse through proteome-scale interaction databases such as BioGRID, BioPlex, and STRING (12,13,100). For example, the BioGRID-derived NDD DUB interactomes are enriched with proteins encoded by NDD genes (Figure 3B; Tables S2 and S3). Furthermore, about half of the NDD genes within these interactomes are intolerant to LoF mutations, suggesting that they are haploinsufficient, thus requiring precise control of their abundance. The fact that the predominate role of several NDD DUBs is to promote the abundance of their interactors through antagonism of proteasomal (or lysosomal) degradation (Figure 2A) illustrates that NDDs caused by LoF of NDD DUBs may be, at least in part, underpinned by loss of abundance of proteins encoded by haploinsufficient NDD genes.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Systematic genome sequencing of individuals with NDDs continues to resolve the contributions that individual DUBs play in brain development. However, even for well-established DUBs, technical and experimental limitations have restricted our knowledge of their complex cell and developmental functions and protein-substrate interactions. The current knowledge of NDD DUBs is a piecemeal of studies focusing on different DUBs, different interactors, different cell types (and so on), predominantly generated in the context of cancer. How DUBs spatiotemporally regulate networks of protein substrates, particularly during physiological brain development, remains largely unexplored. Identification of DUB substrates is challenged by rapid substrate degradation and interaction kinetics. Indeed, traditional immunoprecipitation techniques used to capture interactomes yielded far lower numbers of DUB interactors than predicted (13,14,24,69). Innovations in identifying transient and low-affinity protein-protein interactions and proteomic techniques are providing new opportunities to prospectively identify and interrogate DUB interactions. Proximity biotinylation protein-protein interaction techniques such as BioID, are proving ideal for capturing transient and unstable interactions within the in situ spatially resolved environments of cells and organisms (30,101,102). Coupling these techniques with quantitative proteomics allows identification of interacting proteins en masse (24,69,101,102). The ubiquitination status of interactomes and entire proteomes (aka ubiquitinomes) can also be resolved using techniques such as Ub-remnant (di-glycine) immunoprecipitations (69,103), while the linkage topology of Ub chains decorating proteins can be assessed globally using Ub-TUBEs, Ub linkage–specific antibodies, and Ub-clipping technologies, among others (7,47,104–110). CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)–Cas9 and iPSC technologies have also made studying LoF alleles of DUBs in brain cell contexts more tractable. Entire proteomes and the impact that DUB LoF has on its interacting proteins can be derived by combining the above techniques with traditional paradigms of translational and proteasomal inhibition. Such advances are already driving new knowledge of DUB function, but the challenge is to apply them in the context of the developing brain using in vivo–based small animal and in vitro–based stem and neural cell models (47,69,111,112). Collectively, the ability to deep dive into the discovery of NDD DUB interactomes and their functional relationships in the developing brain can now be approached at the proteome scale with high temporal and spatial resolution.

THERAPEUTIC IMPLICATIONS

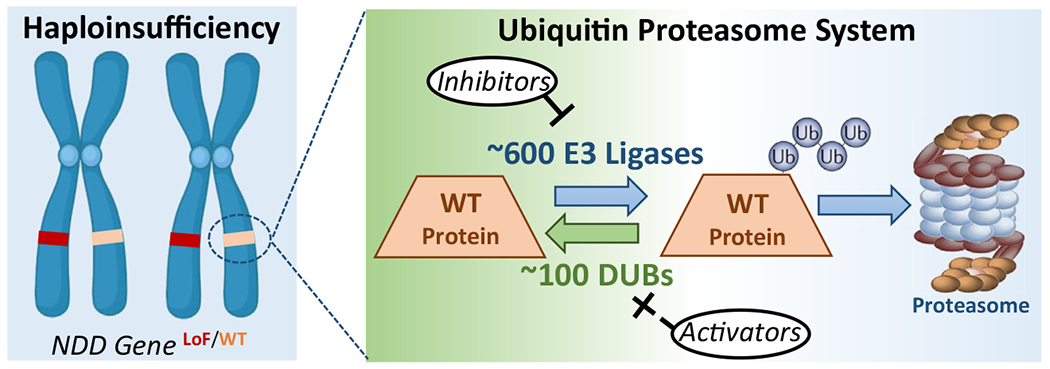

While it is apparent that DUBs regulate networks of proteins, the rate-limiting components of an NDD DUB interactome network may represent major drivers of phenotypic features and, as such, represent key therapeutic targets. ANK3, for example, is a key target in USP9X NDDs, because restoration of its abundance rescues synaptic defects in neurons lacking USP9X (30). The fact that USP9X regulates the abundance of ANK3 by antagonizing its UPS-dependent degradation reveals that increasing ANK3 abundance could be achieved by targeting other regulatory points in the UPS, for example, inhibiting upstream ANK3 cognate E3-ligases such as CDC20-APC (30). However, the emerging mechanism by which NDD DUBs function to antagonize the UPS degradation of proteins encoded by other NDD genes highlights a grander opportunity: NDDs caused by haploinsufficiency may be amenable to therapies that increase abundance of proteins encoded on wild-type alleles by inhibiting their UPS-based degradation (Figure 4). Antagonizing the UPS could be approached by targeting the regulatory elements imparting specificity, either by inhibiting cognate E3-ligases or activating cognate DUBs. The large numbers of DUBs and E3-ligases (~700 in total), coupled with their unique protein specificities, provide an extensive scope of therapeutic targets (113). The cancer field long viewed the UPS as a fertile therapeutic landscape (113). Small molecule inhibitors disrupting specific E3-ligase–substrate interactions now represent true precision therapies in pre/clinical trials (114,115), and developing modifiers of E3-ligase and DUB activity is an active field of research and industry (116–119). Indeed, the UPS is heralded as a means to “drug the undruggable (120)” because of the diverse ways in which it is being harnessed to protect or execute a protein’s existence. Adapting these technologies to increase the abundance of haploinsufficient proteins is largely unexplored. The identification and study of NDD DUBs is illuminating this possibility, and their ongoing study will resolve how the UPS can be targeted as another approach to overcome NDDs caused by haploinsufficiency.

Figure 4.

A therapeutic paradigm to overcome haploinsufficiency in neurodevelopmental disorders using antagonism of UPS. The major outcome of haploinsufficiency is loss of protein dosage. If the dosage of a haploinsufficient protein is also regulated by UPS, then antagonism of UPS may restore protein dosage and overcome the haploinsufficient state. UPS antagonism should be approached by targeting the elements of UPS harboring specificity, either by inhibiting cognate E3-ubiquitin ligases or activating cognate DUBs. With ~700 E3-ubiquitin ligases and DUBs, there is a large scope of targets that represent a fertile landscape of therapeutic exploration and are supported by successful application in the field of oncology. DUBs, deubiquitinating enzymes; LoF, loss of function; NDD, neurodevelopmental disorder; UPS, ubiquitin proteasome system; WT, wild-type.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by SFARI Explorer Grant 527556 to MP and LAJ. LAJ is supported by the Australian Research Council (Grant No. DE160100620). JG is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Research Fellowship (Grant No. 1155224). PP is supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01MH107182).

We apologize to the many investigators whose work we could not cite here due to space restrictions. We are thankful for the funding received from Creola Pora with the help of her friends and colleagues. We acknowledge communication of data provided by the following resources: Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project, supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health; National Cancer Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (data obtained from the GTEx Portal on August 1, 2021: https://gtexportal.org/home/); the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), which is available free of restrictions under the Creative Commons Zero Public-Domain Dedication (data obtained from gnomAD V2.1.1 on August 1, 2021: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/); the Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID; data obtained from BioGRID portal V4.4 on August 1,2021: https://thebiogrid.org/); and the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database, which are freely available under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 (data obtained from STRING V11.5 on August 1, 2021: https://string-db.org/).

LAJ devised and coordinated the review, compiled and analyzed all data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. JG, MP, RS, and PP contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M (2006): Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22:159–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasherman MA, Premarathne S, Burne THJ, Wood SA, Piper M (2020): The ubiquitin system: A regulatory hub for intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. Mol Neurobiol 57:2179–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner A, Manford AG, Rape M (2017): Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of stem cell biology. Trends Cell Biol 27:568–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nijman SMB, Luna-Vargas MPA, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AMG, Sixma TK, Bernards R (2005): A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell 123:773–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basar MA, Beck DB, Werner A (2021): Deubiquitylases in developmental ubiquitin signaling and congenital diseases. Cell Death Differ 28:538–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanpude P, Bhattacharya S, Dey AK, Maiti TK (2015): Deubiquitinating enzymes in cellular signaling and disease regulation. IUBMB Life 67:544–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kliza K, Husnjak K (2020): Resolving the complexity of ubiquitin networks. Front Mol Biosci 7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komander D, Rape M (2012): The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 81:203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millard SM, Wood SA (2006): Riding the DUBway: Regulation of protein trafficking by deubiquitylating enzymes. J Cell Biol 173:463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eletr ZM, Wilkinson KD (2014): Regulation of proteolysis by human deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:114–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clague MJ, Urbé S, Komander D (2019): Breaking the chains: Deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function [published correction appears in Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019; 20:321]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20:338–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oughtred R, Rust J, Chang C, Breitkreutz BJ, Stark C, Willems A, et al. (2021): The BioGRID database: A comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. Protein Sci 30:187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huttlin EL, Bruckner RJ, Navarrete-Perea J, Cannon JR, Baltier K, Gebreab F, et al. (2021): Dual proteome-scale networks reveal cell-specific remodeling of the human interactome. Cell 184:3022–3040.e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Gygi SP, Harper JW (2009): Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138:389–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mevissen TET, Komander D (2017): Mechanisms of deubiquitinase specificity and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem 86:159–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahtoe DD, Sixma TK (2015): Layers of DUB regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 40:456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leznicki P, Kulathu Y (2017): Mechanisms of regulation and diversification of deubiquitylating enzyme function. J Cell Sci 130:1997–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B, Ruan J, Chen M, Li Z, Manjengwa G, Schlüter D, et al. (2022): Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs): Decipher underlying basis of neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Psychiatry 27:259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbé S (2009): Breaking the chains: Structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao YH, Fountain MD Jr, Fon Tacer K, Xia F, Bi W, Kang SHL, et al. (2015): USP7 acts as a molecular rheostat to promote WASH-dependent endosomal protein recycling and is mutated in a human neurodevelopmental disorder. Mol Cell 59:956–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fountain MD, Oleson DS, Rech ME, Segebrecht L, Hunter JV, McCarthy JM, et al. (2019): Pathogenic variants in USP7 cause a neurodevelopmental disorder with speech delays, altered behavior, and neurologic anomalies. Genet Med 21:1797–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kon N, Zhong J, Kobayashi Y, Li M, Szabolcs M, Ludwig T, et al. (2011): Roles of HAUSP-mediated p53 regulation in central nervous system development. Cell Death Differ 18:1366–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homan CC, Kumar R, Nguyen LS, Haan E, Raymond FL, Abidi F, et al. (2014): Mutations in USP9X are associated with X-linked intellectual disability and disrupt neuronal cell migration and growth. Am J Hum Genet 94:470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson BV, Kumar R, Oishi S, Alexander S, Kasherman M, Vega MS, et al. (2020): Partial loss of USP9X function leads to a male neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorder converging on transforming growth factor β signaling. Biol Psychiatry 87:100–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paemka L, Mahajan VB, Ehaideb SN, Skeie JM, Tan MC, Wu S, et al. (2015): Seizures are regulated by ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9 X-linked (USP9X), a de-ubiquitinase. PLoS Genet 11:e1005022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reijnders MRF, Zachariadis V, Latour B, Jolly L, Mancini GM, Pfundt R, et al. (2016): De novo loss-of-function mutations in USP9X cause a female-specific recognizable syndrome with developmental delay and congenital malformations. Am J Hum Genet 98:373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jolly LA, Parnell E, Gardner AE, Corbett MA, Pérez-Jurado LA, Shaw M, et al. (2020): Missensevariant contribution to USP9X-female syndrome. NPJ Genom Med 5:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasherman MA, Currey L, Kurniawan ND, Zalucki O, Vega MS, Jolly LA, et al. (2021): Abnormal behavior and cortical connectivity deficits in mice lacking Usp9x. Cereb Cortex 31:1763–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegeman S, Jolly LA, Premarathne S, Gecz J, Richards LJ, Mackay-Sim A, Wood SA (2013): Loss of Usp9x disrupts cortical architecture, hippocampal development and TGFβ-mediated axonogenesis. PLoS One 8:e68287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon S, Parnell E, Kasherman M, Forrest MP, Myczek K, Premarathne S, et al. (2020): Usp9X controls ankyrin-repeat domain protein homeostasis during dendritic spine development. Neuron 105:506–521.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Premarathne S, Murtaza M, Matigian N, Jolly LA, Wood SA (2017): Loss of Usp9x disrupts cell adhesion, and components of the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways in neural progenitors. Sci Rep 7:8109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murtaza M, Jolly LA, Gecz J, Wood SA (2015): La FAM fatale: USP9X in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:2075–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jolly LA, Taylor V, Wood SA (2009): USP9X enhances the polarity and self-renewal of embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitors. Mol Biol Cell 20:2015–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridges CR, Tan MC, Premarathne S, Nanayakkara D, Bellette B, Zencak D, et al. (2017): USP9X deubiquitylating enzyme maintains RAPTOR protein levels, mTORC1 signalling and proliferation in neural progenitors. Sci Rep 7:391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, et al. (2012): Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature 485:246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, Davis LK, Guter S, Wei Q, Jacob S, Potter MH, et al. (2017): Leveraging blood serotonin as an endophenotype to identify de novo and rare variants involved in autism. Mol Autism 8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torre S, Polyak MJ, Langlais D, Fodil N, Kennedy JM, Radovanovic I, et al. (2017): USP15 regulates type I interferon response and is required for pathogenesis of neuroinflammation [published correction appears in Nat Immunol 2016; 17:1479]. Nat Immunol 18:54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alsohime F, Martin-Fernandez M, Temsah MH, Alabdulhafid M, Le Voyer T, Alghamdi M, et al. (2020): JAK inhibitor therapy in a child with inherited USP18 deficiency. N Engl J Med 382:256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meuwissen MEC, Schot R, Buta S, Oudesluijs G, Tinschert S, Speer SD, et al. (2016): Human USP18 deficiency underlies type 1 interferonopathy leading to severe pseudo-TORCH syndrome. J Exp Med 213:1163–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang D, Zhang DE (2011): Interferon-stimulated gene 15 and the protein ISGylation system. J Interferon Cytokine Res 31:119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritchie KJ, Malakhov MP, Hetherington CJ, Zhou L, Little MT, Malakhova OA, et al. (2002): Dysregulation of protein modification by ISG15 results in brain cell injury. Genes Dev 16:2207–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu H, Haas SA, Chelly J, Van Esch H, Raynaud M, de Brouwer AP, et al. (2016): X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol Psychiatry 21:133–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Firth HV, Richards SM, Bevan AP, Clayton S, Corpas M, Rajan D, et al. (2009): DECIPHER: Database of chromosomal imbalance and phenotype in humans using Ensembl resources. Am J Hum Genet 84:524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi T, Iwamoto Y, Takashima K, Isomura A, Kosodo Y, Kawakami K, et al. (2015): Deubiquitinating enzymes regulate Hes1 stability and neuronal differentiation. FEBS J 282:2411–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi Z, Ouyang J, Sun W, Xiao X, Li S, Jia X, et al. (2019): Biallelic mutations in USP45, encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme, are associated with Leber congenital amaurosis. J Med Genet 56:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saida K, Fukuda T, Scott DA, Sengoku T, Ogata K, Nicosia A, et al. (2021): OTUD5 variants associated with X-linked intellectual disability and congenital malformation. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:631428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck DB, Basar MA, Asmar AJ, Thompson JJ, Oda H, Uehara DT, et al. (2021): Linkage-specific deubiquitylation by OTUD5 defines an embryonic pathway intolerant to genomic variation. Sci Adv 7: eabe2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tripolszki K, Sasaki E, Hotakainen R, Kassim AH, Pereira C, Rolfs A, et al. (2021): An X-linked syndrome with severe neurodevelopmental delay, hydrocephalus, and early lethality caused by a missense variation in the OTUD5 gene. Clin Genet 99:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santiago-Sim T, Burrage LC, Ebstein F, Tokita MJ, Miller M, Bi W, et al. (2017): Biallelic variants in OTUD6B cause an intellectual disability syndrome associated with seizures and dysmorphic features. Am J Hum Genet 100:676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straniero L, Rimoldi V, Soldà G, Bellini M, Biasucci G, Asselta R, Duga S (2018): First replication of the involvement of OTUD6B in intellectual disability syndrome with seizures and dysmorphic features. Front Genet 9:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romero-Ibarguengoitia ME, Cantú-Reyna C, Gutierrez-González D, Cruz-Camino H, González-Cantú A, Sanz Sánchez MA (2020): Comparison of genetic variants and manifestations of OTUD6B-related disorder: The first Mexican case. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 8:2324709620957777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowther C, Costain G, Stavropoulos DJ, Melvin R, Silversides CK, Andrade DM, et al. (2015): Delineating the 15q13.3 microdeletion phenotype: A case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Genet Med 17:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki H, Inaba M, Yamada M, Uehara T, Takenouchi T, Mizuno S, et al. (2021): Biallelic loss of OTUD7A causes severe muscular hypotonia, intellectual disability, and seizures. Am J Med Genet A 185:1182–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garret P, Ebstein F, Delplancq G, Dozieres-Puyravel B, Boughalem A, Auvin S, et al. (2020): Report of the first patient with a homozygous OTUD7A variant responsible for epileptic encephalopathy and related proteasome dysfunction. Clin Genet 97:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uddin M, Unda BK, Kwan V, Holzapfel NT, White SH, Chalil L, et al. (2018): OTUD7A regulates neurodevelopmental phenotypes in the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 102:278–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin J, Chen W, Chao ES, Soriano S, Wang L, Wang W, et al. (2018): Otud7a knockout mice recapitulate many neurological features of 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 102:296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonell LM, Mirzaa GM, Alcantara D, Schwartzentruber J, Carter MT, Lee LJ, et al. (2013): Mutations in STAMBP, encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme, cause microcephaly-capillary malformation syndrome. Nat Genet 45:556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki S, Tamai K, Watanabe M, Kyuuma M, Ono M, Sugamura K, Tanaka N (2011): AMSH is required to degrade ubiquitinated proteins in the central nervous system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 408:582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bilguvar K, Tyagi NK, Ozkara C, Tuysuz B, Bakircioglu M, Choi M, et al. (2013): Recessive loss of function of the neuronal ubiquitin hydrolase UCHL1 leads to early-onset progressive neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:3489–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rydning SL, Backe PH, Sousa MML, Iqbal Z, Øye AM, Sheng Y, et al. (2017): Novel UCHL1 mutations reveal new insights into ubiquitin processing [published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet 2017; 26:1217–1218]. Hum Mol Genet 26:1031–1040.28007905 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Das Bhowmik A, Patil SJ, Deshpande DV, Bhat V, Dalal A (2018): Novel splice-site variant of UCHL1 in an Indian family with autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia-79. J Hum Genet 63:927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McMacken G, Lochmüller H, Bansagi B, Pyle A, Lochmüller A, Chinnery PF, et al. (2020): Behr syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a family with a novel UCHL1 deletion. J Neurol 267:3643–3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reinicke AT, Laban K, Sachs M, Kraus V, Walden M, Damme M, et al. (2019): Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) loss causes neurodegeneration by altering protein turnover in the first postnatal weeks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:7963–7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saigoh K, Wang YL, Suh JG, Yamanishi T, Sakai Y, Kiyosawa H, et al. (1999): Intragenic deletion in the gene encoding ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase in gad mice. Nat Genet 23:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen F, Sugiura Y, Myers KG, Liu Y, Lin W (2010): Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 is required for maintaining the structure and function of the neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:1636–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Donis KC, Morales Saute JA, Krum-Santos AC, Furtado GV, Mattos EP, Saraiva-Pereira ML, et al. (2016): Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3/Machado-Joseph disease starting before adolescence. Neurogenetics 17:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Switonski PM, Szlachcic WJ, Krzyzosiak WJ, Figiel M (2015): A new humanized ataxin-3 knock-in mouse model combines the genetic features, pathogenesis of neurons and glia and late disease onset of SCA3/MJD. Neurobiol Dis 73:174–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adorno M, Sikandar S, Mitra SS, Kuo A, Nicolis Di Robilant B, Haro-Acosta V, et al. (2013): Usp16 contributes to somatic stem-cell defects in Down’s syndrome. Nature 501:380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiang SY, Wu HC, Lin SY, Chen HY, Wang CF, Yeh NH, et al. (2021): Usp11 controls cortical neurogenesis and neuronal migration through Sox11 stabilization. Sci Adv 7:eabc6093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2019): Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179:1469–1482.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cui CP, Zhang Y, Wang C, Yuan F, Li H, Yao Y, et al. (2018): Dynamic ubiquitylation of Sox2 regulates proteostasis and governs neural progenitor cell differentiation [published correction appears in Nat Commun 2019; 10:173]. Nat Commun 9:4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huo Y, Khatri N, Hou Q, Gilbert J, Wang G, Man HY (2015): The deubiquitinating enzyme USP46 regulates AMPA receptor ubiquitination and trafficking [published correction appears in J Neurochem 2017; 141:472]. J Neurochem 134:1067–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scudder SL, Goo MS, Cartier AE, Molteni A, Schwarz LA, Wright R, Patrick GN (2014): Synaptic strength is bidirectionally controlled by opposing activity-dependent regulation of Nedd4-1 and USP8. J Neurosci 34:16637–16649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Imai S, Mamiya T, Tsukada A, Sakai Y, Mouri A, Nabeshima T, Ebihara S (2012): Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 46 (Usp46) regulates mouse immobile behavior in the tail suspension test through the GABAergic system. PLoS One 7:e39084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tomida S, Mamiya T, Sakamaki H, Miura M, Aosaki T, Masuda M, et al. (2009): Usp46 is a quantitative trait gene regulating mouse immobile behavior in the tail suspension and forced swimming tests. Nat Genet 41:688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dufner A, Knobeloch KP (2019): Ubiquitin-specific protease 8 (USP8/UBPy): A prototypic multidomain deubiquitinating enzyme with pleiotropic functions. Biochem Soc Trans 47:1867–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson SM, Bhattacharyya B, Rachel RA, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Householder DB, et al. (2002): Synaptic defects in ataxia mice result from a mutation in Usp14, encoding a ubiquitin-specific protease. Nat Genet 32:420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen PC, Qin LN, Li XM, Walters BJ, Wilson JA, Mei L, Wilson SM (2009): The proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzyme Usp14 is essential for the maintenance of synaptic ubiquitin levels and the development of neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci 29:10909–10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anckar J, Bonni A (2015): Regulation of neuronal morphogenesis and positioning by ubiquitin-specific proteases in the cerebellum [published correction appears in PLoS One 2015; 10:e0133943] [published correction appears in PLoS One 2015; 10:e0135535]. PLoS One 10:e0117076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang J, Chen M, Li B, Lv B, Jin K, Zheng S, et al. (2016): Altered striatal rhythmic activity in cylindromatosis knock-out mice due to enhanced GABAergic inhibition. Neuropharmacology 110:260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin C, Kim S, Kang H, Yun KN, Lee Y, Zhang Y, et al. (2019): Shank3 regulates striatal synaptic abundance of Cyld, a deubiquitinase specific for Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains. J Neurochem 150:776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wood MA, Kaplan MP, Brensinger CM, Guo W, Abel T (2005): Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L3 (Uchl3) is involved in working memory. Hippocampus 15:610–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al-Shami A, Jhaver KG, Vogel P, Wilkins C, Humphries J, Davis JJ, et al. (2010): Regulators of the proteasome pathway, Uch37 and Rpn13, play distinct roles in mouse development. PLoS One 5: e13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rivkin E, Almeida SM, Ceccarelli DF, Juang YC, MacLean TA, Srikumar T, et al. (2013): The linear ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinase gumby regulates angiogenesis. Nature 498:318–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ng BG, Eklund EA, Shiryaev SA, Dong YY, Abbott MA, Asteggiano C, et al. (2020): Predominant and novel de novo variants in 29 individuals with ALG13 deficiency: Clinical description, biomarker status, biochemical analysis, and treatment suggestions. J Inherit Metab Dis 43:1333–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martin HC, Jones WD, McIntyre R, Sanchez-Andrade G, Sanderson M, Stephenson JD, et al. (2018): Quantifying the contribution of recessive coding variation to developmental disorders. Science 362:1161–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hüffmeier U, Kraus C, Reuter MS, Uebe S, Abbott MA, Ahmed SA, et al. (2021): EIF3F-related neurodevelopmental disorder: Refining the phenotypic and expanding the molecular spectrum. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee ASY, Kranzusch PJ, Cate JHD (2015): eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature 522:111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moretti J, Chastagner P, Gastaldello S, Heuss SF, Dirac AM, Bernards R, et al. (2010): The translation initiation factor 3f (eIF3f) exhibits a deubiquitinase activity regulating Notch activation. PLoS Biol 8:e1000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Růžičková S, Staněk D (2017): Mutations in spliceosomal proteins and retina degeneration. RNA Biol 14:544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Georgiou M, Ali N, Yang E, Grewal PS, Rotsos T, Pontikos N, et al. (2021): Extending the phenotypic spectrum of PRPF8, PRPH2, RP1 and RPGR, and the genotypic spectrum of early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.GTEx Consortium (2013): The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 45:580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, et al. (2020): The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans [published correction appears in Nature 2021; 590:E53] [published correction appears in Nature 2021; 597:E3-E4]. Nature 581:434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bishop P, Rocca D, Henley JM (2016): Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1): Structure, distribution and roles in brain function and dysfunction. Biochem J 473:2453–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wright MH, Berlin I, Nash PD (2011): Regulation of endocytic sorting by ESCRT-DUB-mediated deubiquitination. Cell Biochem Biophys 60:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Paudel P, Zhang Q, Leung C, Greenberg HC, Guo Y, Chern YH, et al. (2019): Crystal structure and activity-based labeling reveal the mechanisms for linkage-specific substrate recognition by deubiquitinase USP9X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:7288–7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zajicek A, Yao WD (2021): Remodeling without destruction: Non-proteolytic ubiquitin chains in neural function and brain disorders. Mol Psychiatry 26:247–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Friocourt G, Kappeler C, Saillour Y, Fauchereau F, Rodriguez MS, Bahi N, et al. (2005): Doublecortin interacts with the ubiquitin protease DFFRX, which associates with microtubules in neuronal processes. Mol Cell Neurosci 28:153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wei X, Guo J, Li Q, Jia Q, Jing Q, Li Y, et al. (2019): Bach1 regulates self-renewal and impedes mesendodermal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Sci Adv 5:eaau7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. (2019): STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Han S, Li J, Ting AY (2018): Proximity labeling: Spatially resolved proteomic mapping for neurobiology. Curr Opin Neurobiol 50:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Qin W, Cho KF, Cavanagh PE, Ting AY (2021): Deciphering molecular interactions by proximity labeling. Nat Methods 18:133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, et al. (2011): Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell 44:325–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Swatek KN, Usher JL, Kueck AF, Gladkova C, Mevissen TET, Pruneda JN, et al. (2019): Insights into ubiquitin chain architecture using Ub-clipping. Nature 572:533–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hjerpe R, Aillet F, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Lang V, England P, Rodriguez MS (2009): Efficient protection and isolation of ubiquitylated proteins using tandem ubiquitin-binding entities. EMBO Rep 10:1250–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hu Z, Li H, Wang X, Ullah K, Xu G (2021): Proteomic approaches for the profiling of ubiquitylation events and their applications in drug discovery. J Proteomics 231:103996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Matsumoto ML, Dong KC, Yu C, Phu L, Gao X, Hannoush RN, et al. (2012): Engineering and structural characterization of a linear polyubiquitin-specific antibody. J Mol Biol 418:134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Matsumoto ML, Wickliffe KE, Dong KC, Yu C, Bosanac I, Bustos D, et al. (2010): K11-linked polyubiquitination in cell cycle control revealed by a K11 linkage-specific antibody. Mol Cell 39:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Newton K, Matsumoto ML, Ferrando RE, Wickliffe KE, Rape M, Kelley RF, Dixit VM (2012): Using linkage-specific monoclonal antibodies to analyze cellular ubiquitylation. Methods Mol Biol 832:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Newton K, Matsumoto ML, Wertz IE, Kirkpatrick DS, Lill JR, Tan J, et al. (2008): Ubiquitin chain editing revealed by polyubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies. Cell 134:668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ordureau A, Paulo JA, Zhang J, An H, Swatek KN, Cannon JR, et al. (2020): Global landscape and dynamics of parkin and USP30-dependent ubiquitylomes in iNeurons during mitophagic signaling. Mol Cell 77:1124–1142.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jahan AS, Lestra M, Swee LK, Fan Y, Lamers MM, Tafesse FG, et al. (2016): Usp12 stabilizes the T-cell receptor complex at the cell surface during signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E705–E714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Eldridge AG, O’Brien T (2010): Therapeutic strategies within the ubiquitin proteasome system. Cell Death Differ 17:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang W, Sidhu SS (2014): Development of inhibitors in the ubiquitination cascade. FEBS Lett 588:356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fajner V, Maspero E, Polo S (2017): Targeting HECT-type E3 ligases–Insights from catalysis, regulation and inhibitors. FEBS Lett 591:2636–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gabrielsen M, Buetow L, Nakasone MA, Ahmed SF, Sibbet GJ, Smith BO, et al. (2017): A general strategy for discovery of inhibitors and activators of RING and U-box E3 ligases with ubiquitin variants. Mol Cell 68:456–470.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang W, Wu KP, Sartori MA, Kamadurai HB, Ordureau A, Jiang C, et al. (2016): System-wide modulation of HECT E3 ligases with selective ubiquitin variant probes. Mol Cell 62:121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Skaar JR, Pagan JK, Pagano M (2014): SCF ubiquitin ligase-targeted therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13:889–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kanner SA, Shuja Z, Choudhury P, Jain A, Colecraft HM (2020): Targeted deubiquitination rescues distinct trafficking-deficient ion channelopathies. Nat Methods 17:1245–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huang X, Dixit VM (2016): Drugging the undruggables: Exploring the ubiquitin system for drug development. Cell Res 26:484–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.