Abstract

Factors such as socioeconomic status, age at menarche and childbearing patterns are components that have been shown to influence mammary gland development and establish breast cancer disparity. Pubertal mammary gland development is selected as the focus of this review, as it is identified as a “window of susceptibility” for breast cancer risk and disparity. Here we recognize non-Hispanic White, African American, and Asian American women as the focus of breast cancer disparity, in conjunction with diets associated with changes in breast cancer risk. Diets consisting of high fat, N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, N-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, as well as obesity and the Western diet have shown to lead to changes in pubertal mammary gland development in mammalian models, therefore increasing the risk of breast cancer and breast cancer disparity. While limited intervention strategies are offered to adolescents to mitigate development changes and breast cancer risk, the prominent solution to closing the disparity among the selected population is to foster lifestyle changes that avoid the deleterious effects of unhealthy diets.

1. Introduction

The mammary gland is one of the few organs that continues to develop postnatally through stages of massive tissue remodeling that is directly influenced and controlled by hormonal signaling. This includes stages of development involving proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. These stages of development also include multiple cell types including stromal and epithelial crosstalk (Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). These timepoints of tightly regulated development are now being described as “windows of susceptibility” where modifiable risk factors, including diet, obesity, hormone therapy, alcohol consumption, and smoking can negatively influence normal mammary gland regulation and thereby increase the risk of developing breast cancer (Isaac, Sundar, Romanos, & Rahman, 2016; Martinson et al., 2013; Okasha et al., 2003; Sundaram, Johnson, & Makowski, 2013).

Studies have shown that specific populations around the world are at a greater risk for developing breast cancer. Breast cancer is the most prevalent female cancer accounting for nearly one in three cancers diagnosed in this population. Unfortunately, although recent statistics show that incidence rates are similar, mortality rates are over 40% higher in African American (AA) women compared to Non-Hispanic White (NHW) Women (Churpek et al., 2015; Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013). In addition, AA women are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages and to have the lowest survival rate at each stage of diagnosis. Several studies have shown that AA adolescents often begin puberty at younger ages than other races (Churpek et al., 2015). Menarche is defined as the first menstrual cycle in female humans. From both social and medical perspectives, it is often considered the central event of female puberty, as it signals the possibility of fertility. Females experience menarche at different ages. The timing of menarche is influenced by female biology, as well as genetic and environmental factors, specifically nutritional factors. The mean age of menarche has declined over the last century, but the magnitude of the decline and the factors responsible remain subjects of contention. The worldwide average age of menarche is very difficult to estimate accurately, and it varies significantly by geographical region, race, ethnicity and other characteristics, but various estimates have placed it at 13 years of age. This is particularly relevant here, as the risk for developing breast cancer increases for each year a female starts menarche sooner. It is estimated that for each 2-year increase in actual age at menarche, there is a 10% reduction in breast cancer risk (Ambrosone et al., 2014; Carwile et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2014; Deardorff et al., 2014; Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013; Reagan et al., 2012). Despite this, the link between cancer disparity and the “windows of susceptibility” during mammary development have not been adequately assessed.

While intervention strategies during puberty have been cited as having the greatest impact on reducing breast cancer risk, the idea of prescribing young females with medication to prevent the future development of breast cancer is, for obvious reasons, controversial. However, current research is beginning to uncover alternative interventions, including diet, exercise, and other modifiable lifestyle factors as more appropriate and feasible strategies to decrease breast cancer risk in all women but in particular AA women who suffer from many of the risk factors that are independently associated with earlier menarche (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Colditz & Frazier, 1995; Dieli-Conwright, Lee, & Kiwata, 2016; Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013; Reagan et al., 2012). This review will summarize the biological, socioeconomic and environmental associations between mammary development and breast cancer disparity rates.

2. Mammary gland development

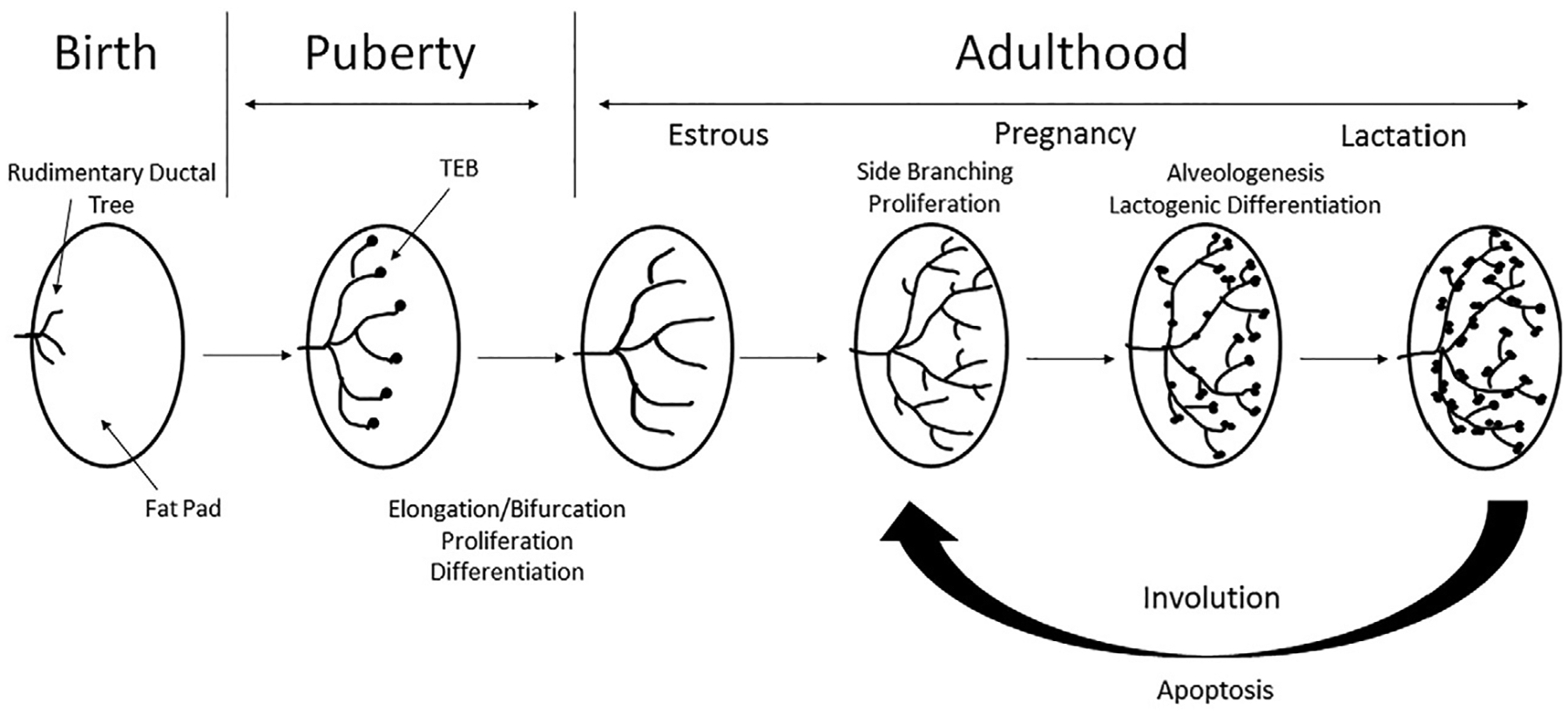

The mammary gland, as mentioned previously, is a unique organ as it develops postnatally. Following pre-natal or embryonic development where a rudimentary ductal tree is formed, pubertal development is the next major stage of development to occur whereby the ductal tree is laid down in order for the mature functioning gland. This allows for the future development changes that occur during the cyclic stages of pregnancy, lactation and involution (Fig. 1). The mammary gland is a complex secretory organ composed of multiple cell types, including epithelial cells, adipocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and various immune cells (Brady, Chuntova, & Schwertfeger, 2016; Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). The main function of the mammary gland is to produce and secrete milk for the nourishment of newborns during breastfeeding and lactation. The gland fulfills its function of supplying adequate milk by forming an extensive and functional tree-like structure of branched ducts that fill the fat pad during pubertal development (Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). Reproductive development is primarily under hormonal influence leading to an increase in secondary and tertiary branching, vascularization, as well as alveologenesis during pregnancy, which later differentiate into milk-secreting lobules during lactation. After weaning of offspring, stagnate milk in the lobules sends local cues leading to cellular signaling and an immune response, which helps to guide the ductal tree back to a simple ductal architecture where it no longer produces or secretes milk (Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). This stage of development is called involution. The consequences of these tightly regulated phases of mammary development leads to periods that are vulnerable to cancer development, known as windows of susceptibility (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Colditz & Frazier, 1995; Dieli-Conwright et al., 2016; Martinson et al., 2013; Sundaram et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Overview of different stages of mammary gland development. Schematic representation of mammary gland development from a rudimentary structure at birth, through tightly regulated phases of growth such as puberty, associated with the formation of TEBs and increased proliferation, differentiation and elongation/branching of the ductal tree. After puberty the gland is fully formed and becomes quiescent, until pregnancy. Hormonal factors during pregnancy leads to increased proliferation, differentiation, side branching and alveologenesis to form a functioning gland for lactation. Following lactation is a stage of tightly controlled apoptosis during involution to return the gland to a quiescent state.

2.1. Window of susceptibility

The “lifecycle” of mammary gland development can be divided into five windows of cancer susceptibility: in utero, pubertal, pregnancy, postpartum involution, and age-related involution. Fortunately, each of these windows shows a limited duration making the at-risk populations identifiable (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Colditz & Frazier, 1995). A key characteristic of these risk “windows” is tightly regulated tissue remodeling driven by hormonal signaling, in addition to mammary epithelium and stromal crosstalk (Martinson et al., 2013; Sundaram et al., 2013). Epidemiological studies have established a connection between specific life events and breast cancer risk. Having a child later in life, as well as a child with high birth weight, increases breast cancer risk for woman in adulthood (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Okasha et al., 2003; Reagan et al., 2012). Nutrition during adolescence has been shown to affect breast cancer risk, as increased consumption of milk, soy, fruits and vegetables, as well as caloric restriction lead to a decreased risk of breast cancer (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Okasha et al., 2003; Shrivastava, Shrivastava, & Ramasamy, 2016). On the contra, increased consumption of visible fats of meat led to increased risk of premenopausal breast cancer (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Okasha et al., 2003; Shrivastava et al., 2016). Non-dietary factors, such as physical activity during adolescence have also been shown to lead to a decrease in breast cancer risk (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Dieli-Conwright et al., 2016; Okasha et al., 2003). Other specific life events including age at puberty, length of time between menarche and first birth, exposure to smoking and age at menopause have also been shown to affect breast cancer risk (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Deardorff et al., 2014; Okasha et al., 2003). The recognition of these “windows of susceptibility” led to the proposal of targeting intervention strategies for cancer prevention at crucial stages of mammary gland development (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Colditz & Frazier, 1995; Dieli-Conwright et al., 2016).

2.2. The pubertal window

The pubertal window is attractive to study as preventative measures at this stage have the potential to have the biggest impact on reducing future risk of breast disease. Unfortunately, it remains one of the least attractive for clinical translation due to the controversy surrounding the use of chemoprevention drug use in vulnerable populations. However, a greater understanding of the development of the mammary gland during puberty will lead to more attractive methods of prevention in this population. One of the best models that researchers use to study mammary development is rodents (mouse and rat). Indeed, research in rodent models has led to a better understanding of mammary development and has been applied to humans.

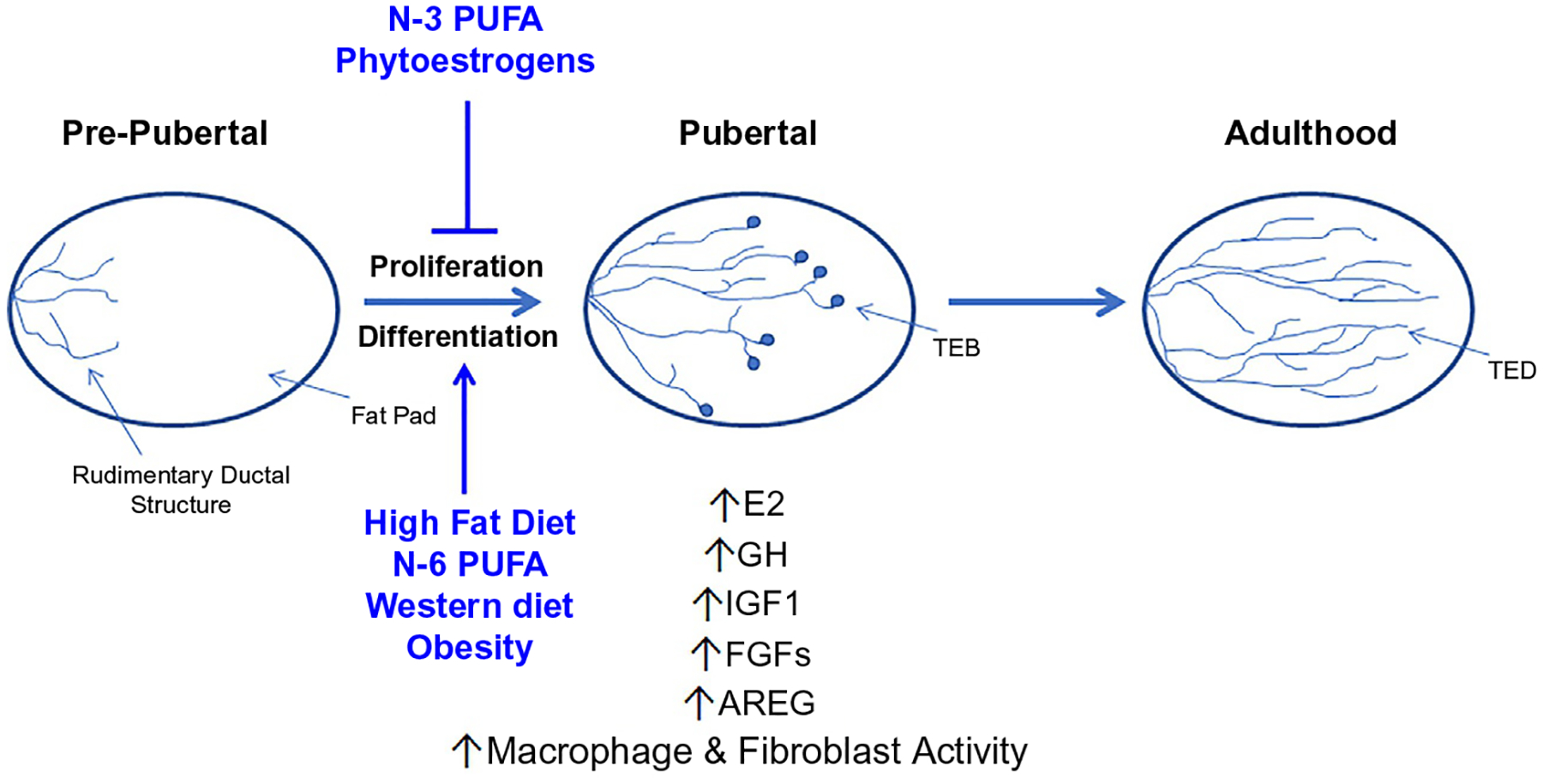

Pubertal development of the rodent mammary gland begins during an extensive hormone-dependent phase of growth associated with increased epithelial cell proliferation (Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006). This stage is associated with the formation of terminal end buds (TEBs), highly proliferative club-like structures at the ends of ducts (Ball, 1998; Butner et al., 2016; Paine & Lewis, 2017). These bulbous structures form around 3 weeks of age and begin to penetrate the fat pad via the proliferation of a single layer of cap cells at the ends of the TEBs and the underlying epithelium (Ball, 1998; Butner et al., 2016; Paine & Lewis, 2017). Cap cells then differentiate into the myoepithelial layer surrounding the tubular ductal bilayer as the tree pushes into the mammary fat pad (Ball, 1998; Butner et al., 2016; Paine & Lewis, 2017; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). Proliferation is regulated by growth hormones (GH), thereby inducing the expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) in the mammary stromal cells (Fig. 2). Acting together with estrogen (E2) from the ovaries, IGF1 helps to induce epithelial proliferation. Acting via a paracrine fashion, E2 signals through its receptor, estrogen receptor 1 (ER), to stimulate the release of amphiregulin (AREG), an epidermal growth factor (EGF) family member (Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). AREG then binds to its receptor on stromal cells inducing the release of fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), which stimulate ER negative luminal cell proliferation (Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006).

Fig. 2.

Factors influencing pubertal mammary gland development. The tightly regulated window of pubertal mammary gland development has shown to be a key window of “cancer susceptibility” specific when looking at lifestyle factors, such as diet and obesity. Diets such as; a diet high in fat, N-6 PUFA, the Western diet and lifestyle factors such as obesity have been shown in various in vivo models to lead to dysregulation of development and increased hormonal and growth factor status as well as immune/stromal cell activity. Meanwhile other diets high in N-3 PUFA and phytoestrogens have been shown to have protective effects in cancer susceptibility when consumed during puberty.

Extensive primary ductal networks develop via the bifurcation of the TEBs followed by the divergence of secondary side branches. Secondary branching from primary ducts continues until the ductal tree occupies approximately 60% of the fat pad, leaving space for the influence of pregnancy hormones. The mature ductal tree undergoes further branching under the influence of cycling ovarian hormones, leading to the formation of short tertiary side branches (Inman et al., 2015; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). Factors including TGF-β1, Reelin, Slit2 and Netrin1 lead to either positive or negative regulation of mammary ductal formation (Macias & Hinck, 2012; Sternlicht, 2006; Sternlicht et al., 2006). Once the gland is fully formed at the end of pubertal development, highly proliferative TEBs begin to taper off and become quiescent forming terminal end ducts (TEDs) in adulthood (Ball, 1998; Butner et al., 2016; Paine & Lewis, 2017).

3. Mammary gland development and cancer health disparity

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and is the second leading cause of cancer related mortality in women. Although breast cancer incidence is equal among AA and NHW women, AA women are more likely to die of their disease. In fact, more aggressive tumor characteristics are more common in breast cancers diagnosed in AA women than any other racial/ethnic group. Cancer stage at diagnosis directly affects overall survival, and only 52% of breast cancer cases in AA women are diagnosed at local stage, compared to 63% in NHW women. In addition, 22% of breast cancers in AA women are classified as triple negative compared to only 10–12% in women of other racial groups. Since there are currently no targeted therapies for this aggressive subtype of breast cancer it remains the deadliest with the poorest prognosis (Ambrosone et al., 2014). AA women are also more likely to have ER−, PR− and double negative (ER−/PR−) breast cancer compared to NHW women, which is associated with higher grade, later stage and reduced survival rate (Cui et al., 2014). Several biological, socioeconomic and environmental factors exist between mammary development and breast cancer disparity rates, these will be discussed below.

3.1. Socioeconomic and environmental factors

The disparity observed in breast cancer survival outcomes may be attributed in part to unhealthy lifestyle and socioeconomic factors, as well as factors associated with access to sufficient medical care. Studies show that as many as 70% of new breast cancer cases may be attributed to diet and poor lifestyle (Willett, 1999). Dietary factors, in particular, are known to affect mammary gland development during puberty and contribute to increased tumor occurrence and progression, discussed in more detail in Section 4 (Shrivastava et al., 2016; Song et al., 2014). Low-income populations are associated with a poor diet consisting of low cost, unhealthy, and highly processed foods. This contributes to the disparities observed as AA communities have the highest prevalence of low-income with over 27% living at or below the poverty level. These populations are also 1.5 times more likely to be obese compared to NHW populations (Economic Policy Institute, n.d.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Service, n.d.). Low-income, poor diet, lack of exercise, and certain life choices such as smoking and drinking reveal a socioeconomic and environmental connection between mammary development, breast cancer risk, and cancer disparity. Historically, a person of a lower socioeconomic status is more likely to integrate themselves with factors that increase breast cancer risk. Marketing strategies, environmental and community factors, such as reduced access to fruits and vegetables and fewer opportunities for physical activity, contribute to the integration of low socioeconomic status and breast cancer risk.

3.2. Menarche

Age at menarche is defined as the age of first menstrual cycle in females and has been linked with increased risk of breast cancer development for each year earlier than average (12.77 years in the United States) at which it occurs. It is estimated that for each 2-year increase in age at menarche, there is a 10% reduction in breast cancer risk. Studies have shown that both AA women and Hispanic women are more likely to have earlier onset of menarche compared to NHW women (Ambrosone et al., 2014; Carwile et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2014; Deardorff et al., 2014; Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013; Reagan et al., 2012). Age at menarche was shown to occur earlier in populations associated with increased poverty levels, and as discussed earlier poverty levels are higher in AA populations (Reagan et al., 2012). NHW women who experienced a later menarche were shown to have a decreased risk for the development of solely ER positive (ER+) breast cancer when compared to AA women, which showed a decreased risk of both ER+/− breast cancer when menarche was later (Ambrosone et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2014). A plethora of factors are thought to cause changes in menarche onset, such as: social economic status (lower family education level and lower family income), obesity during childhood, physical inactivity, and diet (Carwile et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2014; Deardorff et al., 2014; Mervish et al., 2017; Mueller et al., 2015; Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013; Reagan et al., 2012; Vani et al., 2013; Villamor & Jansen, 2016).

3.3. Childbearing patterns

Childbearing patterns have also been shown to differ by race/ethnicity, with higher parity (defined as the number of times a woman has carried a pregnancy to a viable gestational age) and a lower prevalence of lactation in AA women, both of which have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Ambrosone et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2014; Deardorff et al., 2014). In NHW women, it was observed that multiparity (≥3) led to a decreased risk of ER+ breast cancer risk, while late age of first birth (>30 years) and nulliparity led to an increased risk of the development of ER+ breast cancer (Cui et al., 2014). A woman’s risk of breast cancer decreases by 7% for each birth, further signifying the effect parity has on breast cancer prevention. Shorter interval between menarche and first live birth has also been shown to lead to an increased risk of ER negative (ER−) breast cancer (Ambrosone et al., 2014). This is noteworthy, as the current trends are both earlier age at menarche and later age of first birth, both of which serve to increase this interval. Breastfeeding is the optimal method to deliver nutrients to newborns, but also has plentiful benefits on both the infant and the mother. The World Health Organization and American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life and continuing breastfeeding up to 2 years (World Health Organization, 2017). Breastfeeding has also been shown to affect a woman’s breast cancer risk. It has been suggested that the benefits of breastfeeding surpass previously mentioned childbearing patterns, including parity (Phipps & Li, 2014). Furthermore, breastfeeding is a modifiable risk factor which is important for focusing on cancer prevention (Anstey, Chen, Elam-Evans, & Perrine, 2017; Phipps & Li, 2014). Indeed several studies have now shown that women who breastfeed for 4–6 months show a 25–50% reduction in breast cancer risk compared to parous women that have never breastfed (Phipps & Li, 2014). This was further emphasized in a 2002 study that demonstrated a 4.3% decrease in breast cancer risk for every 12 months a mother breastfed (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 2002). Interestingly, there is a significant difference in breastfeeding practices among AA women; data obtained from the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS; n = 35,338 black) and the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII; n = 103,508 white and 2068 black) showed that the age-standardized prevalence of ever breastfeeding was only 44% of multiparous AA women, compared to NHW women who reported 81% (Phipps & Li, 2014; Warner et al., 2013). Data collected in these prospective cohorts were by self-reported questionnaires. This is a continuing trend, as recent national statistics reported only 58.9% of new mothers of AA descent reported breastfeeding, compared to 75.2% of new mothers of NHW descent (Anstey et al., 2017; Phipps & Li, 2014; Smith et al., 2005). These data were collected as part of the National Immunization Survey (NIS) by person to person interview in households with children aged 19–35 months (Smith et al., 2005). One study showed that if AA women breastfed at the same rate as NHW women, the incidence of triple-negative breast cancer in the United States would be reduced by two-thirds among parous AA women (Phipps & Li, 2014). Many factors contribute to this disparity within the AA community and include a lack of information provided about the benefits of breastfeeding, a lack of resources to assist, and interestingly, a lack of social and cultural acceptance within the AA community toward breastfeeding (Anstey et al., 2017). Differences in breastfeeding practices can be contributed to differences in social economic status, as well as more biological factors like obesity, development, diet, physical activity or other chronic diseases (Anstey et al., 2017; Dieli-Conwright et al., 2016; Phipps & Li, 2014).

4. Diet, development and breast cancer risk

Many studies have examined the impact of diet on development and breast cancer risk and these will be discussed in detail below. This information is also summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Overview of studies investigating the impact of diet on development and breast cancer risk.

| Environmental factor | Developmental effect | Breast cancer risk |

|---|---|---|

| High-fat diet | ↑Mammary adiposity (C57BL/6) (Warner et al., 2013) ↓Epithelial proliferation (C57BL/6) (Warner et al., 2013) ↑Epithelial proliferation (BALB/c) (Smith et al., 2005) ↓E2 responsiveness (BALB/c) (Smith et al., 2005) ↓Duct length and number of TEBs (Warner et al., 2013) ↑Vascularization and immune cell recruitment (Olson et al., 2010) Sparse ductal tree (Warner et al., 2013) |

↓Latency of DMBA/PhIP-induced mammary tumors (Olson et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016) ↑Growth factors, stromal invasion, inflammatory and angiogenic processes (Aupperlee et al., 2015; MacLennan & Ma, 2010) ↑Proliferation, tumor growth, M2 macrophage recruitment and vascularization (Aupperlee et al., 2015; MacLennan & Ma, 2010) Intervention after puberty, reduced tumor latency remained (Aupperlee et al., 2015) Loss of luminal gene expression (Snyderwine et al., 1998) ↑Mesenchymal and breast cancer invasive gene expression (Snyderwine et al., 1998) |

| Phytoestrogens | ↑Acceleration of mammary cell differentiation (Shao, 1998; Yu, Zhang, & Wu, 2003) ↑Proliferation and number of TEBs in early development (Shao, 1998; Yu et al., 2003) |

Abundant in blood and urine of low breast cancer populations (Brzezinski & Debi, 1999; Jawaid, Crane, Nowers, Lacey, & Whitehead, 2010) Associated with later age of menarche (Brzezinski & Debi, 1999; Mervish et al., 2017) ↑Progesterone, estrogen receptor expression and proliferation of lobular epithelium (Iwasaki et al., 2008) ↓HER2 and neu expression (Iwasaki et al., 2008) Inhibit growth of estrogen dependent and independent breast cancer cell lines (Anderson et al., 2014; Maskarinec, Verheus, & Tice, 2010; Wu et al., 2002) ↓Chemically-induced mammary tumors in mice fed pubertal diet Antioxidant effect (Shao, 1998; Wu et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2003) ↓Angiogenesis, EGF signaling pathway and local synthesis of estrogen (Maskarinec et al., 2010; Shao, 1998; Wiseman et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2003) |

| N-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Delay in pubertal onset (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, & Cotroneo, 1998; Wu et al., 2002) ↓TEBs in early development (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) ↓TEB proliferation (Abdelmagid et al., 2016) ↑TEB apoptosis, ductal coverage and elongation (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) |

Abundant in populations with low breast cancer incidence (Manni et al., 2011; Willett, 1999; Zhu et al., 2011) Delay in pubertal onset (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) Anti-inflammatory and modulation of oncogenic signaling via lipid raft disruption (Bagga et al., 2002; Goodstine et al., 2003; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Leslie et al., 2014; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2011) ↑Apoptosis, expression of proteins in cell cycle control and DNA repair (Bagga et al., 2002; Goodstine et al., 2003; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Leslie et al., 2014; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2011) ↓Cellular proliferation and mammographic density (Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Liu & Ma, 2014; Luijten et al., 2013; MacLennan et al., 2013; Medvedovic et al., 2009; Olivo & Hilakivi-Clarke, 2005; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004; Weisburger, 1997; Wu et al., 2002) Inhibit the effects of oncogenic N-6 PUFAs (Goodstine et al., 2003; Luijten et al., 2013) |

| N-6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Early pubertal onset (Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) ↑TEBs in early development (Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) ↑Proliferation and AA in glands (Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2002) |

↑Expression of human breast cancer genes (Zhu et al., 2011) ↑AA leading to precursors active in carcinogenesis (Goodstine et al., 2003; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 2011) Unbalanced ratio of N-6/N-3 leads to inflammation, modulation of oncogenic protein signaling and increased proliferation (Diorio & Dumas, 2014; Goodstine et al., 2003; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Liu & Ma, 2014; Luijten et al., 2013) |

| Western diet | ↑Proliferation of epithelial cells of TEBs (Escrich et al., 2004; Khan et al., 1994; Uribarri et al., 2010) ↑TEB and duct presence (Escrich et al., 2004; Khan et al., 1994; Uribarri et al., 2010) |

Exposure to diet after immigration leads to loss of protective nature (Brzezinski & Debi, 1999; Jawaid et al., 2010; Messina, Caan, Abrams, Hardy, & Maskarinec, 2013; Wiseman et al., 2000) Early menarche onset (Carwile et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2015; Villamor & Jansen, 2016) ↑Consumption of reactive compounds leading to manipulation of cell cycle and survival (Fritz et al., 2013; Snyderwine, 1998; Xue et al., 1996) |

| Obesity | Enlarged mammary gland (Gooderham et al., 2002) Sparse ductal tree, surrounded by thick collagen layers and incomplete myoepithelium layer (Gooderham et al., 2002) ↓Ductal branching (Gooderham et al., 2002) |

↑Inflammation and formation of CLS (Kamikawa et al., 2009; Lauber & Gooderham, 2011) ↑Pro-inflammatory factors and aromatase (Kamikawa et al., 2009; Lauber & Gooderham, 2011) ↑NF-κβ, hypertrophy of adipocytes and hormone receptors on tumors (Bhardwaj et al., 2015; Kamikawa et al., 2009; Lauber & Gooderham, 2011; Subbaramaiah et al., 2011) |

4.1. High-fat diet

A high-fat diet (HFD) is a diet consisting of at least 35% of total calories is consumed from fats, both unsaturated and saturated. In addition to the popular processed foods, many other foods have a high fat content including but not limited to animal fat, chocolate, butter, and oily fish. Commonly higher in fat content, most processed foods are easier to obtain as they are normally cheaper considering socioeconomical factors, such as lower family income. Many dishes among different cultures and ethnicities such as fried foods or “soul food” contain ingredients with high fat such as oils, butters, and fats to increase flavor and appeal.

Animal studies have explored the impact of high-fat diet on pubertal growth in various strains of mice. Genetic background is important as many studies have shown that different outcomes can be observed depending on the strain used. C57BL/6 mice fed a HFD during puberty led to reduced ductal length, as well as number of TEBs, a sparse ductal tree, increased mammary adiposity, and reduced mammary epithelial cell proliferation when compared to mice fed a control diet (Olson et al., 2010). A HFD in C57BL/6 mice was also shown to reduce E2 responsiveness, a key hormonal factor in the developing mammary gland. When BALB/c mice were fed a HFD during puberty, a similar morphological change was observed in the glands; however, BALB/c mice showed increased mammary epithelial cell proliferation and reduced E2 responsiveness with no change in adiposity of the gland. BALB/c mice, genetically related to A/J mice, are less susceptible to HFD-induced obesity compared to C57BL/6 as seen in the increased mammary adiposity and associated differences among the strains. Interestingly, weight loss initiated in C57BL/6 mice from switching of diets, HFD to control, restored TEB formation and ductal elongation, showing weight gain and mammary gland adiposity to be key players in pubertal mammary development (MacLennan & Ma, 2010; Olson et al., 2010). BALB/c mice fed a HFD also showed increased recruitment of immune cells, such as eosinophils and mast cells, to periepithelial mammary stroma, as well as hyperplastic lesions during pubertal development (3 weeks). Increased vascularization was observed later in pubertal development to sustain the increased proliferation (Aupperlee et al., 2015).

Rodent models have also explored the impact of HFD on breast cancer risk. BALB/c mice fed a HFD throughout puberty, showed a reduced latency of a median time of 115 days versus 204 in LFD in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA)-induced mammary tumors, which were similar to human basal-like breast cancer (Aupperlee et al., 2015). The group showed that the reduced latency is most likely a result of increased growth factor expression, as well as increased inflammatory and angiogenic processes. Prior to tumor formation, mice fed the HFD showed increased proliferation, hyperplasia, and macrophage recruitment. Resultant tumors also showed increased proliferation, M2 macrophage recruitment, as well as increased vascularization. Interestingly, mice fed a HFD diet during early puberty (3 weeks), then switched to a low-fat diet (LFD) in late puberty (9 weeks), still showed similar reduced latency in tumors with human basal-like characteristics compared to mice fed only HFD for 45 weeks, emphasizing the importance of the pubertal window of insult (Zhao et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016). Similar studies in rats showed that treatment with the carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo [4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) during early puberty (~6 weeks of age) and fed a HFD for 25 weeks, results in an increase in tumor incidence with associated increases in tumor proliferation and growth, as well as stromal invasion compared to rats fed a LFD (Snyderwine, Davis, Schut, & Roberts-Thomson, 1998; Snyderwine et al., 1998). Furthermore, mammary glands from rats fed the HFD during puberty showed a loss of luminal epithelial cell marker gene expression and an increase in mesenchymal cell marker gene expression (Vimentin) and breast cancer invasive genes, similar to human basal-like characteristics, suggesting that a HFD may induce genes associated with a poorer prognosis when consumed during specific times of development (Martinez-Chacin, Keniry, & Dearth, 2014).

4.2. Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens are a class of naturally occurring phenolic compounds found in plants or derived from in vivo metabolism of precursors found in plants. The two main subtypes are ligans and isoflavones, which can be found in whole-grain rye bread, red clove, legumes, beans, fruits, vegetables, flaxseed, and soy (Brzezinski & Debi, 1999; Jawaid et al., 2010; Wiseman et al., 2000). Ligans and isoflavones are shown to be abundant in the blood and urine of populations that are associated with low breast cancer incidence, for example, women of Asian descent (Iwasaki et al., 2008; Wiseman et al., 2000). A diet high in both isoflavones and ligans was shown to associate with later age of menarche, which as we discussed earlier is associated with decreased breast cancer risk (Iwasaki et al., 2008; Mervish et al., 2017). Genistein, found primarily in soy, is the most studied compound in the class of isoflavones. Genistein and other phytoestrogens can act as selective estrogen modulators (SERMs) and can bind to either ERα or ERβ, leading to stimulation or reduction of estrogenic activity and genomic activation (Brzezinski & Debi, 1999; Messina et al., 2013; Rice & Whitehead, 2006).

Asian women have lower breast cancer incidence and mortality compared to NHW women, and this is believed to be the result of a diet with high soy content (Iwasaki et al., 2008; Maskarinec et al., 2010; Messina et al., 2013; Rice & Whitehead, 2006; Wu et al., 2002). The diet appears to be protective in nature during specific times of exposure, especially during pubertal development, as Asian women who immigrated to the United States before onset of pubertal development had higher breast cancer rates, comparable to those observed in NHW women (Iwasaki et al., 2008; Maskarinec et al., 2010; Rice & Whitehead, 2006; Wiseman et al., 2000). Increased soy intake was shown to associate with increases in both PR and ER expression and decreased HER2 expression, both of which are associated with better outcome in women with breast cancer (Messina et al., 2013).

Treatment of estrogen dependent and independent breast cancer cells in vitro with genistein conferred a growth inhibitory effect when administered at high concentrations, but growth stimulatory when administered at lower concentrations (Anderson et al., 2014; Shao, 1998; Yu et al., 2003). When rat models were exposed to genistein through diet (25 and 250mg), during early stages of development, a reduction of DMBA-induced mammary cancer was observed (20% and 50%, respectively). This was confirmed in a second study that showed a 52% reduction in mammary tumor incidence in mice fed genistein (Anderson et al., 2014; Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998). The protective effects observed may have been a result of accelerated mammary cell differentiation during development, as rat models given injections of genistein during neonatal and prepubertal timepoints showed increased proliferation and number of TEBs during pubertal development (21 days of age), but decreased proliferation and number of TEBs at time of carcinogenic treatment (50 days of age) compared to control rats with no genistein exposure (Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998). Phytoestrogens may also play a protective role acting as an antioxidant, inhibiting specific enzymes such as tyrosine kinase, topoisomerase II, as well as decreasing angiogenesis, the EGF signaling pathway and local synthesis of estrogen in breast tissue (Lamartiniere, Murril, et al., 1998; Lamartiniere, Zhang, et al., 1998; Rice & Whitehead, 2006; Shao, 1998).

4.3. N-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids

The three most common N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are α-linolenic acid (ALA), commonly found in plant oils such as walnut oil and flaxseed oil and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both commonly found in fish oils. Consumption of N-3 PUFAs are important for normal metabolism and should be consumed by mammals for a healthy lifestyle. Early exposure to a diet of N-3 PUFAs in mice resulted in a delay in pubertal onset and reduced TEB presence in early puberty, possibly through induced epithelial differentiation (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014; Leslie et al., 2014; Olivo & Hilakivi-Clarke, 2005). Increased ductal coverage and elongation was also observed in mice fed a N-3 PUFA diet (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014). As discussed earlier delayed pubertal onset is associated with a decreased in breast cancer risk in women (Abdelmagid et al., 2016). When a HFD with increased N-3 PUFA presence was given to mice, increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of TEBs occurred; however, with a LFD, the opposite was observed among the TEBs, indicating that dietary effects on pubertal mammary gland development are not linear (Olivo & Hilakivi-Clarke, 2005). The Western diet is also commonly associated with a high N-6 PUFA to N-3 PUFA ratio, averaging at 15:1–16.7:1, compared to an optimal ratio proposed to be 4:1 or lower (Simopoulos, 2002). Early exposure of N-3 PUFAs leads to regulation of pathways involved in energy metabolism, adipose tissue function, inflammation and arachidonic acid specific pathways via reduction of the N-6 PUFA in the mammary gland (Leslie et al., 2014; Liu & Ma, 2014; Luijten et al., 2013; MacLennan et al., 2013; Manni et al., 2011; Olivo & Hilakivi-Clarke, 2005; Zhu et al., 2011).

Americans on average consume a lower amount of N-3 PUFAs compared to Japanese, Norwegian, and Mediterranean populations. Interestingly, populations that consume more N-3 PUFAs have a reduced breast cancer risk (Goodstine et al., 2003; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004; Willett, 1999). A diet with a higher ratio of N-3 PUFAs has been shown to have a protective role against breast cancer through anti-inflammatory effects, modulation of oncogenic protein signaling possibly via disruption of lipid rafts in cell membranes, and increased expression of proteins of cell cycle control and DNA repair (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014; Bagga et al., 2002; Medvedovic et al., 2009; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004; Simopoulos, 2002; Weisburger, 1997). A study in the United States showed that consumption of a diet with increased N-3 PUFAs was associated with a 41% reduction in breast cancer risk in premenopausal and an 11% reduction in postmenopausal women (Goodstine et al., 2003). Studies in mice revealed that N-3 PUFA led to suppressive effects of tumorigenesis via decreased inflammation, cellular proliferation and mammographic density, and increased apoptosis possibly via the inhibition of the MEK/ERK/BAD signaling pathway (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014; Diorio & Dumas, 2014; Leslie et al., 2014; Liu & Ma, 2014; MacLennan et al., 2013; Manni et al., 2011; Medvedovic et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011). A diet high in N-3 PUFA may also inhibit the effects of an oncogenic N-6 PUFA diet (discussed below) on breast epithelial cells in culture and in the mammary gland itself, as a reduction of arachidonic acid was observed in the mammary gland of mice fed a high N-3 PUFA diet (Bagga et al., 2002; Manni et al., 2011).

4.4. N-6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids

The most common N-6 PUFAs in modern diets originate from vegetable oils, most commonly linoleic acid (LA), which is further broken down in the body to arachidonic acid. Other sources of N-6 PUFAs are eggs, poultry, flaxseed oil, whole-grain breads and cereals. Consumption of N-6 PUFAs are important for normal metabolism and must be consumed by mammals in a specific ratio with N-3 PUFAs for a healthy lifestyle. However, diets in Western developed countries consume much higher levels of N-6 PUFA when compared to N-3 PUFA thereby promoting the pathological effects, leading to the development of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, auto-immune disease, and cancer (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Simopoulos, 2002). Mice fed a diet high in N-6 PUFAs resulted in earlier pubertal onset, increased TEB presence in early puberty, and increased arachidonic acid in the mammary gland (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014).

People from Western developed countries consume a diet high in N-6 PUFAs compared to people from Asian countries, where more protective N-3 PUFAs are consumed. Furthermore, as discussed earlier, women from Western developed countries have higher rates of breast cancer than women from Asian countries, suggesting a cancer-promoting role of N-6 PUFAs (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2014; Goodstine et al., 2003). This could be, in part, due to the increased consumption of processed foods and vegetable oils, leading to increased arachidonic acid in the body, the precursor of leukotrienes and prostaglandin, which are known to be active in carcinogenesis, such as inflammation and cellular proliferation (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Bagga et al., 2002; Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004). These reactive compounds can lead to inhibition of gap junctions which alters cellular communication, leading to either apoptosis or the immortalization of the cells, both of which are associated with tumorigenesis (Saadatian-Elahi et al., 2004). Increased ratio of N-6 PUFA to N-3 PUFA has shown to be an important determinant of breast cancer risk, rather than total N-6 PUFA consumption (Bagga et al., 2002). An unbalanced ratio leads to chronic inflammation, modulation of oncogenic protein signaling, and increased proliferation (Abdelmagid et al., 2016; Escrich et al., 2004; MacLennan et al., 2013; Manni et al., 2011).

4.5. Western diet

The Western diet is high in sugar, protein and fat, but low in fruit, grains and vegetables (Uribarri et al., 2010). This diet is also associated with increased consumption of manufactured or processed foods, which are commonly lower in cost and therefore are more widely consumed in low-income populations (Uribarri et al., 2010). Studies have shown that increased consumption of animal protein, caffeinated drinks, and artificially sweetened drinks increases the risk for early onset menarche (Carwile et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2015; Villamor & Jansen, 2016). On the contra, a diet with increased vegetable protein was shown to associate with a decreased risk for early onset menarche (Villamor & Jansen, 2016). In mice fed a Western diet during puberty, increased number and proliferation of TEBs was observed together with increased mammary ducts (Khan et al., 1994; Xue et al., 1996, 1999).

Asian populations consume as much as 25g of soy protein or 100mg of isoflavones a day, this is compared to a Western diet that contains less than 1g of soy protein or 1g of isoflavones a day (Fritz et al., 2013). As discussed earlier, women from Asian countries have a lower incidence of breast cancer. Additionally, Asians who immigrate to the United States and adjust to the Western diet lose their protection against development of breast cancer within the first generation (Iwasaki et al., 2008; Maskarinec et al., 2010; Rice & Whitehead, 2006; Wiseman et al., 2000). The Western diet also consists of increased meat consumption and decreased consumption of fruits/vegetables. Cooked meat contains reactive compounds such as heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Snyderwine, 1998). The most studied of these reactive compounds is 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Rats exposed to PhIP lead to tumors in the prostate, colon and mammary gland. Furthermore, human mammary epithelial cells (MCF10A) treated with PhIP underwent genomic and cellular changes, including increased p53 and cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1, as well as manipulation of cell cycle and survival as cells were shown to be increasing in the G1 phase (Gooderham et al., 2002). These changes are critical as it can effect genome repair, the removal of damaged cells and lead to mutation acceptance (Gooderham et al., 2002). PhIP was also shown to induce breast cancer invasion and lead to an associated increase in the expression of cathepsin D, cyclooxygenase 2, and matrix metalloproteinase activity (Lauber & Gooderham, 2011).

4.6. Obesity

A sedentary lifestyle, excessive drinking, and poor diet can lead to chronic obesity leading to changes in mammary gland development as well as an increased predisposition to breast cancer (Sundaram et al., 2013). Childhood obesity, as well as a sedentary lifestyle were shown to be associated with an increased risk for early onset menarche (Vani et al., 2013; Villamor & Jansen, 2016). Mice fed a HFD to induce obesity were shown to have enlarged mammary glands with greater adiposity and a less dense ductal tree with decreased branching. The ductal tree was also shown to be surrounded by thick collagen layers and an incomplete myoepithelial layer (Kamikawa et al., 2009).

Chronic obesity has also been shown to lead to increased inflammation leading to formation of crown-like structures (CLS) in mammary glands, structures associated with increased proinflammatory factors (TNFα, IL-1B, COX2, etc.) and aromatase (Bhardwaj et al., 2015; Subbaramaiah et al., 2011). Obesity and CLS also showed to lead to increased NF-κB activation, hypertrophy of adipocytes and increased hormone receptors on tumors (Bhardwaj et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2015a, 2015b; Subbaramaiah et al., 2011). In obese postmenopausal women there was a 50% greater risk of breast cancer development compared to those that were non-obese, potentially from increased adipose tissue and adipokines, which may affect cancer progression site (Gu et al., 2011). Interestingly, caloric restriction in an obesity mouse model was shown to reverse some of the changes caused by obesity; however, weight management alone may be insufficient to completely reverse epigenetic reprogramming and inflammatory signals in the microenvironment of the mammary gland (Bhardwaj et al., 2013, 2015; Rossi et al., 2016).

5. Pubertal intervention strategies

The pubertal window of development, while the hardest to introduce intervention, may dramatically decrease cancer incidence, making it one of the most optimal windows of risk in breast development to target (Martinson et al., 2013). This prompted us to focus our review on the dietary and lifestyle risks of pubertal development and breast cancer. Many pubertal intervention strategies are lifestyle-change based, as pharmacological intervention may be seen as unethical or lead to unknown side effects. Proper education of healthy lifestyle choices during pubertal development is key to introduce the nutritional and lifestyle interventions needed to reduce breast cancer risk in women. Nutritional intervention, such as increased consumption of healthier items associated with decreased breast cancer risk, as discussed above, including vegetables, walnut oil, flaxseed oil, fish, etc., along with decreased consumption of foods associated with increased risk, may help to decrease breast cancer risk overall. Additional lifestyle interventions such as increased physical activity and caloric restriction may also help to decrease adult breast cancer risk.

6. Concluding remarks

The mammary gland and its “lifecycle” of development, specifically pubertal development, is a sensitive time, where cancer susceptibility is high (Biro & Deardorff, 2013; Colditz & Frazier, 1995; Macias & Hinck, 2012; Martinson et al., 2013; Sundaram et al., 2013). External factors, such as diet, can lead to changes in pubertal development ultimately leading to increased breast cancer risk in adulthood. These factors, however, can be mitigated or managed with healthier choices and an active lifestyle, aiding in the reduction of preventable cancers (Dieli-Conwright et al., 2016). Socioeconomic factors demonstrate a link in breast cancer risk such as low-income, poor diet, lack of exercise, and lifestyle choices including smoking and drinking reveal an environmental connection to breast cancer risk and cancer disparity.

References

- Abdelmagid SA, et al. (2016). Role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and exercise in breast cancer prevention: Identifying common targets. Nutrition and Metabolic Insights, 9, 71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosone CB, et al. (2014). Associations between estrogen receptor negative breast cancer and timing of reproductive events differ between African-American and European-American women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 23(6), 1115–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BM, et al. (2014). Lifelong exposure to n-3 PUFA affects pubertal mammary gland development. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 39(6), 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey EH, Chen J, Elam-Evans L, & Perrine CG (2017). Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding—United States, 2011–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(27), 723–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aupperlee MD, et al. (2015). Puberty-specific promotion of mammary tumorigenesis by a high animal fat diet. Breast Cancer Research: BCR, 17, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagga D, et al. (2002). Long-Chain n-3-to-n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios in breast adipose tissue from women with and without breast cancer. Nutrition and Cancer, 42(2), 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SM (1998). The development of the terminal end bud in the prepubertal-pubertal mouse mammary gland. The Anatomical Record, 250(4), 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj P, et al. (2013). Caloric restriction reverses obesity induced mammary gland inflammation in mice. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 6(4), 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bhardwaj P, et al. (2015). Estrogen protects against obesity induced mammary gland inflammation in mice. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 8(8), 751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, & Deardorff J (2013). Identifying opportunities for cancer prevention during pre-adolescence and adolescence: Puberty as a window of susceptibility. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 52(5 Suppl), S15–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady NJ, Chuntova P, & Schwertfeger KL (2016). Macrophages: Regulators of the inflammatory microenvironment during mammary gland development and breast cancer. Mediators of Inflammation, 2016, 4549676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski A, & Debi A (1999). Phytoestrogens: The “natural” selective estrogen receptor modulators? European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 85(1), 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner JD, et al. (2016). A hybrid agent-based model of the developing mammary terminal end bud. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 407, 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carwile JL, et al. (2015). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and age at menarche in a prospective study of US girls. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 30(3), 675–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churpek JE, et al. (2015). Inherited predisposition to breast cancer among African American women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 149, 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, & Frazier AL (1995). Models of breast cancer show that risk is set by events of early life: Prevention efforts must shift focus. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 4(5), 567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. (2002). Breast cancer and breastfeeding: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. The Lancet, 360(9328), 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, et al. (2014). Associations of hormone-related factors with breast cancer risk according to hormone receptor status among white and African-American women. Clinical Breast Cancer, 14(6), 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, et al. (2014). Socioeconomic status and age at menarche: An examination of multiple indicators in an ethnically diverse cohort. Annals of Epidemiology, 24(10), 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieli-Conwright CM, Lee K, & Kiwata JL (2016). Reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence: An evaluation of the effects and mechanisms of diet and exercise. Current Breast Cancer Reports, 8(3), 139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diorio C, & Dumas I (2014). Relations of omega-3 and omega-6 intake with mammographic breast density. Cancer Causes & Control, 25(3), 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economic Policy Institute; n.d. Available from: www.stateofworkingamerica.org.

- Escrich E, et al. (2004). Identification of novel differentially expressed genes by the effect of a high-fat n-6 diet in experimental breast cancer. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 40(2), 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz H, et al. (2013). Soy, red clover, and isoflavones and breast cancer: A systematic review. PLoS One, 8(11), e81968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooderham NJ, et al. (2002). Molecular and genetic toxicology of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Mutation Research, Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 506–507, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstine SL, et al. (2003). Dietary (n-3)/(n-6) fatty acid ratio: Possible relationship to premenopausal but not postmenopausal breast cancer risk in U.S. women. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(5), 1409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J-W, et al. (2011). Postmenopausal obesity promotes tumor angiogenesis and breast cancer progression in mice. Cancer Biology & Therapy, 11(10), 910–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman JL, et al. (2015). Mammary gland development: Cell fate specification, stem cells and the microenvironment. Development, 142(6), 1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac K, Sundar FJ, Romanos GE, & Rahman I (2016). E-cigarettes and flavorings induce inflammatory and prosenescence responses in oral epithelial cells and periodontal fibroblasts. Oncotarget, 7(47), 77196–77204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M, et al. (2008). Plasma isoflavone level and subsequent risk of breast cancer among Japanese women: A nested case-control study from the Japan Public Health Centerbased prospective study group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(10), 1677–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawaid K, Crane SR, Nowers JL, Lacey M, & Whitehead SA (2010). Long-term genistein treatment of MCF-7 cells decreases acetylated histone 3 expression and alters growth responses to mitogens and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 120(4–5), 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikawa A, et al. (2009). Diet-induced obesity disrupts ductal development in the mammary glands of nonpregnant mice. Developmental Dynamics, 238(5), 1092–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Yang K, Newmark H, Wong G, Telang N, Rivlin R, et al. (1994). Mammary ductal epithelial cell hyperproliferation and hyperplasia induced by a nutritional stress diet containing four components of a western-style diet. Carcinogenesis, 15(11), 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamartiniere CA,Murril WB, Manzolillo PA, Zhang JX,Barnes S,Zhang X,et al. (1998). Genistein alters the ontogeny of mammary gland development and protects against chemically-induced mammary cancer in rats. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 217(3), 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamartiniere CA, Zhang JX, & Cotroneo MS (1998). Genistein studies in rats: Potential for breast cancer prevention and reproductive and developmental toxicity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(6), 1400S–1405S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber SN, & Gooderham NJ (2011). The cooked meat-derived mammary carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine promotes invasive behaviour of breast cancer cells. Toxicology, 279(1–3), 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie MA, et al. (2014). Mammary tumour development is dose-dependently inhibited by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the MMTV-neu(ndl)-YD5 transgenic mouse model. Lipids in Health and Disease, 13, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HY, et al. (2015a). Obesity, expression of adipocytokines, and macrophage infiltration in canine mammary tumors. The Veterinary Journal, 203(3), 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HY, et al. (2015b). Effects of obesity and obesity-related molecules on canine mammary gland tumors. Veterinary Pathology, 52(6), 1045–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, & Ma DWL (2014). The role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Nutrients, 6(11), 5184–5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijten M, et al. (2013). Lasting effects on body weight and mammary gland gene expression in female mice upon early life exposure to n-3 but not n-6 high-fat diets. PLoS One, 8(2), e55603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias H, & Hinck L (2012). Mammary gland development. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology, 1(4), 533–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan M, & Ma DWL (2010). Role of dietary fatty acids in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research: BCR, 12(5), 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan MB, et al. (2013). Mammary tumor development is directly inhibited by lifelong n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 24(1), 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni A, Richie JP Jr., Xu H, Washington S, Aliaga C, Cooper TK, et al. (2011). Effects of fish oil and Tamoxifen on preneoplastic lesion development and biomarkers of oxidative stress in the early stages of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced rat mammary carcinogenesis. International Journal of Oncology, 39(5), 1153–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Chacin RC, Keniry M, & Dearth RK (2014). Analysis of high fat diet induced genes during mammary gland development: Identifying role players in poor prognosis of breast cancer. BMC Research Notes, 7, 543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson HA, et al. (2013). Developmental windows of breast cancer risk provide opportunities for targeted chemoprevention. Experimental Cell Research, 319(11), 1671–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskarinec G, Verheus M, & Tice JA (2010). Epidemiologic studies of isoflavones mammographic density. Nutrients, 2(1), 35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic M, et al. (2009). Influence of fatty acid diets on gene expression in rat mammary epithelial cells. Physiological Genomics, 38(1), 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervish NA, et al. (2017). Peripubertal dietary flavonol and lignan intake and age at menarche in a longitudinal cohort of girls. Pediatric Research, 82(2), 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina M, Caan BJ, Abrams DI, Hardy MA, & Maskarinec G (2013). It’s time for clinicians to reconsider their proscription against the use of soyfoods by breast cancer patients. Oncology, 27(5), 430–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller NT, et al. (2015). Consumption of caffeinated and artificially sweetened soft drinks is associated with risk of early menarche. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(3), 648–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okasha M, et al. (2003). Exposures in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood and breast cancer risk: A systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 78(2), 223–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SE, & Hilakivi-Clarke L (2005). Opposing effects of prepubertal low- and high-fat n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diets on rat mammary tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis, 26(9), 1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson LK, et al. (2010). Pubertal exposure to high fat diet causes mouse strain-dependent alterations in mammary gland development and estrogen responsiveness. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 34(9), 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine IS, & Lewis MT (2017). The terminal end bud: The little engine that could. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia, 22, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps AI, & Li CI (2014). Breastfeeding and triple-negative breast cancer: Potential implications for racial/ethnic disparities. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 106(10), dju281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnitz MS, & Lodish MB (2013). Racial disparities in pubertal development. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 31(5), 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan PB, et al. (2012). African-American/white differences in the age of menarche: Accounting for the difference. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 75(7), 1263–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice S, & Whitehead SA (2006). Phytoestrogens and breast cancer—Promoters or protectors? Endocrine-Related Cancer, 13(4), 995–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi EL, et al. (2016). Obesity-associated alterations in inflammation, epigenetics, and mammary tumor growth persist in formerly obese mice. Cancer Prevention Research, 9(5), 339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadatian-Elahi M, et al. (2004). Biomarkers of dietary fatty acid intake and the risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Cancer, 111(4), 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao ZMZ (1998). Genistein exerts multiple suppressive effects on human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Research, 58(21), 4851–4857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, & Ramasamy J (2016). Exploring the role of dietary factors in the development of breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics, 12(2), 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos AP (2002). The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 56(8), 365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PJ, et al. (2005). Statistical methodology of the National Immunization Survey, 1994–2002. Vital Health Statistics 2, 138, 1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyderwine EG (1998). Diet and mammary gland carcinogenesis. Recent Results in Cancer Research, 152, 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyderwine EG, Davis CD, Schut HA, & Roberts-Thomson SJ (1998). Proliferation, development and DNA adduct levels in the mammary gland of rats given 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and a high fat diet. Carcinogenesis, 19(7), 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyderwine EG, et al. (1998). Mammary gland carcinogenicity of 2-amino-l-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine in Sprague-Dawley rats on high- and low-fat diets. Nutrition and Cancer, 31(3), 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F, et al. (2014). RAGE regulates the metabolic and inflammatory response to high-fat feeding in mice. Diabetes, 63(6), 1948–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD (2006). Key stages in mammary gland development: The cues that regulate ductal branching morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Research, 8(1), 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, et al. (2006). Hormonal and local control of mammary branching morphogenesis. Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity, 74(7), 365–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaramaiah K, et al. (2011). Obesity is associated with inflammation and elevated aromatase expression in the mouse mammary gland. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 4(3), 329–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Sun H, et al. (2011). Omega-3 fatty acids induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cells and mouse mammary tissue through syndecan-1 inhibition of the MEK-Erk pathway. Carcinogenesis, 32(10), 1518–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram S, Johnson AR, & Makowski L (2013). Obesity, metabolism and the microenvironment: Links to cancer. Journal of Carcinogenesis, 12, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribarri J, et al. (2010). Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(6), 911–916.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Service; n.d. Available from: www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov.

- Vani KR, et al. (2013). Menstrual abnormalities in school going girls—Are they related to dietary and exercise pattern? Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 7(11), 2537–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villamor E, & Jansen EC (2016). Nutritional determinants of the timing of puberty. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner ET, et al. (2013). Estrogen receptor positive tumors: Do reproductive factors explain differences in incidence between black and white women? Cancer Causes & Control, 24(4), 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburger JH (1997). Dietary fat and risk of chronic disease: Mechanistic insights from experimental studies. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97(7), S16–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett WC (1999). Goals for nutrition in the year 2000. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 49(6), 331–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman H, et al. (2000). Isoflavone phytoestrogens consumed in soy decrease F(2)-isoprostane concentrations and increase resistance of low-density lipoprotein to oxidation in humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(2), 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Breastfeeding. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en/.

- Wu AH, et al. (2002). Adolescent and adult soy intake and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans. Carcinogenesis, 23(9), 1491–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, et al. (1996). Model of mouse mammary gland hyperproliferation and hyperplasia induced by a western-style diet. Nutrition and Cancer, 26(3), 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, et al. (1999). Influence of dietary calcium and vitamin D on diet-induced epithelial cell hyperproliferation in mice. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 91(2), 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Zhang L, & Wu D (2003). Genistein induced apoptosis in MCF-7 and T47D cells. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu = Journal of Hygiene Research, 32(2), 125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, et al. (2013). Pubertal high fat diet: Effects on mammary cancer development. Breast Cancer Research: BCR, 15(5), R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, et al. (2011). Mammary gland density predicts the cancer inhibitory activity of the N-3 to N-6 ratio of dietary fat. Cancer Prevention Research, 4(10), 1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, et al. (2016). Pubertal and adult windows of susceptibility to a high animal fat diet in Trp53-null mammary tumorigenesis. Oncotarget, 7(50), 83409–83423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]