Abstract

Sepsis, a medical emergency, is the overwhelming host response to infection leading to organ failure. The pathophysiology of this heterogeneous disease includes an inflammatory response that stimulates a complex interaction between endothelial and complements with associated coagulation abnormalities. Despite a more comprehensive understanding of sepsis pathophysiology, there exists a translational gap to improve sepsis diagnosis clinically. Many of the proposed biomarkers to diagnose sepsis lack sufficient specificity and sensitivity to be used in routine clinical practice. There has also been a lack of progress in diagnostic tools due to the focus on the inflammatory pathway. Inflammation and coagulation are known to be linked to the innate immune response. Early immunothrombotic changes could result in the early switch from infection to sepsis and aid in sepsis diagnosis. This review integrates both preclinical and clinical studies that highlight sepsis pathophysiology providing a framework for how the development of immunothrombosis could be used as a starting point to investigate biomarkers for early sepsis diagnosis.

Keywords: biomarkers, immunothrombosis, innate immunity, neutrophil extracellular traps, platelets

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis, a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by an exaggerated host response to infection, is one of the leading causes of death worldwide (1). Globally, there are ∼48.9 million sepsis cases, leading to 11 million deaths annually (2, 3). Sepsis is one of the most expensive medical conditions to treat. Before the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, sepsis costs were about $1.3 billion/per year in Ontario, Canada, and $27 billion in the United States (2, 3). The average hospital length of stay for sepsis is twice as long as any other fatal condition, and the in-hospital mortality remains as high as 20% (4, 5). Furthermore, sepsis survivors are at an increased risk of death or a reduced health-related quality of life even after discharge from the hospital (6–8). Hence, sepsis is a significant contributor to the global health burden of diseases. Approximately 80% of septic cases begin treatment in the emergency department, and the rest are transferred to the other departments of the hospital (9). There are three major problems with sepsis diagnosis: 1) the clinical symptoms are not specific to sepsis; 2) no biomarker has sufficient sensitivity and specificity to identify sepsis due to the complex pathophysiology; and 3) sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome with no unifying cause, phenotype, or biological characteristics (10, 11). These challenges require urgent attention, as early diagnosis and treatment are essential for improving sepsis outcomes—ideally within 3 h as outlined by the best practice guidelines (9, 12). This review will describe the pathophysiology of the host response in sepsis within three archetypal biological domains, highlight their complex interplay, and discuss the implication for early diagnosis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of sepsis. A schematic outline of the critical switch from infection to sepsis is termed “Time Zero.” The host-defense mediators elicit exaggerated immune cell response stimulating the complement system and collaterally damaging the endothelium and microvasculature. This figure was created with BioRender.com. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; EWS, early warning score; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

IMMUNE SYSTEM DYSREGULATION: INNATE AND ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSES

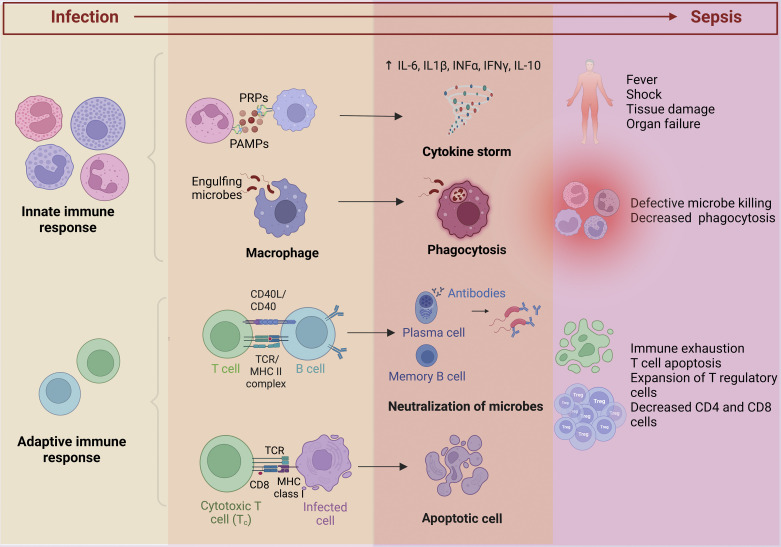

Sepsis is an inflammatory host response to infection. The innate immune system is activated in response to pathogens via the binding of pathogen-associated molecular patterns to specific pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (Fig. 2) (13, 14). Activation of PRRs triggers intracellular signaling that stimulates the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB and interferon regulatory factor pathways to release inflammatory cytokines (13). The timeline of the complex immunological alterations in sepsis is poorly understood. Originally, multiple studies demonstrated that the compensatory anti-inflammatory response occurs after hyperinflammation. However, recent studies postulate that an immunoparalysis phase follows the immediate hyperinflammatory mediators (15). The initial cytokine storm causes fever, shock, respiratory failure, and early death due to multiple organ dysfunction (16, 17). It was postulated that sepsis resulted from a “cytokine storm” induced by proinflammatory mediators; recently, it has been shown that anti-inflammatory mediators also accompany the release of proinflammatory cytokines (18). Proinflammatory cytokines stimulate adhesion molecule expression, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), in the coronary endothelium, and neutrophils infiltrate the myocardium and reduce cardiomyocyte contractility (19). The adaptive immune response triggered by antigen-presenting cells, dendritic cells, and B and T lymphocytes is slower, in contrast to the innate immune system, and produces pathogen-specific antibodies with immunological memory for enhanced response to subsequent exposures from the same antigen (20). Hence, the course of sepsis pathophysiology involves both a pro- and anti-inflammatory response influencing sepsis progression.

Figure 2.

Immune system activation in sepsis. During sepsis, the systemic activation of the immune system results in an inflammatory response characterized by cytokine storm with associated fever, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. The adaptive immune response produces pathogen-specific antibodies with immunological memory for subsequent exposures to the same antigen. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression causes apoptotic depletion of immune cells, immune exhaustion, and decreased CD4 and CD8 cells. This figure was created with BioRender.com. PAMPS, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PRP, pattern recognition protein; TCR, T-cell receptor.

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression, also called “immune exhaustion,” involves the apoptotic depletion of immune cells (21–24). The innate and adaptive immune cells undergo apoptosis contributing to reduced clearance of invading pathogens (24–28). This cell depletion is spanned across all-patient age groups (21, 29). Apoptotic depletion of cells occurs in a greater magnitude among sepsis nonsurvivors than survivors (23, 30–32). Apoptotic depletion of CD4+ T cells results in decreased cytokine production interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) by the subsets of CD4+ T cells, particularly T helper (Th)1 and Th2 (23, 33). T cells can develop a state of functional unresponsiveness referred to as “exhaustion” due to prolonged antigen exposure and altered differentiation of memory T cells (30). There is an increase in T regulatory suppressor cells with concomitant loss of effector T cells, associated with higher sepsis-related mortality (34, 35). Because of the suppression of cell-based immunity, the mortality associated with the late phase of sepsis is due to acquired secondary and opportunistic infections such as Candida (36). The immune system stimulates endothelial and contributes to microcirculatory failure that intertwines in the sepsis pathophysiology.

ENDOTHELIAL AND MICROCIRCULATORY DYSFUNCTION IN SEPSIS

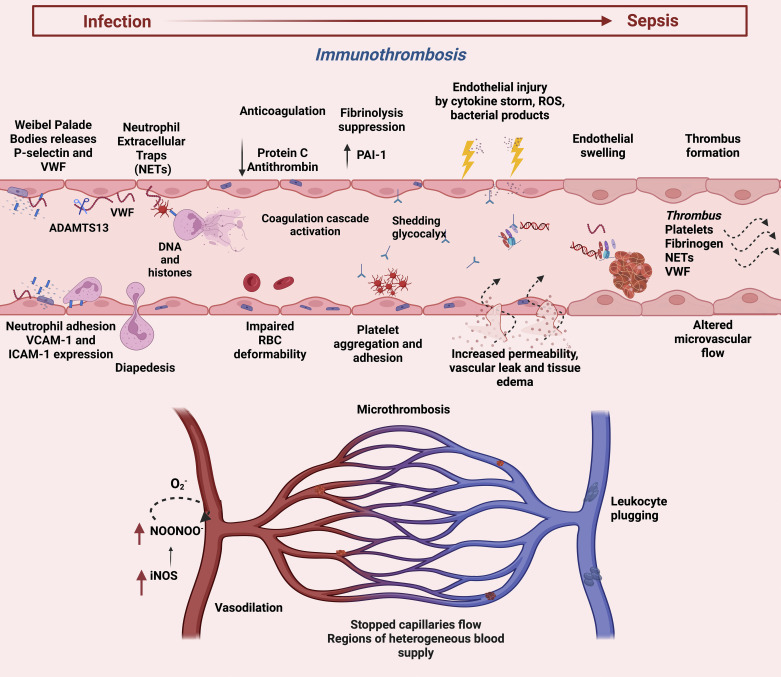

It has been suggested that endothelial cells form a dynamic equilibrium between inflammation, innate immunity, complement, and coagulation to delicate a host response in sepsis (Fig. 3) (37). Microvascular dysfunction in sepsis begins with activation of the endothelium and changes to a proinflammatory phenotype for endothelial cells (ECs) (38). The cytokine storm during hyperinflammation damages the endothelium, causing dysregulated vascular tone and homeostasis, impairing the vascular permeability barrier (38–42). Although ECs share common characteristics, organ-specific features are observed due to the heterogeneity of different microcirculatory beds (43–45). The integrity of the endothelial lining regulated by the endothelial cytoskeleton and glycocalyx is disrupted by the release of reactive oxygen species, inflammatory cytokines, and bacterial endotoxins leading to glycocalyx shedding (46–50). Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by widespread endothelial barrier dysfunction in the lungs mediated by proinflammatory cytokines with increased pulmonary vascular permeability and diffused pulmonary infiltrates leads to the accumulation of protein-rich fluid predisposing to acute respiratory failure (51). In addition, the glycocalyx layer helps to modulate the leukocyte-endothelial interactions under physiological conditions (46). Glycocalyx shedding enhances leukocyte activation, adhesion, and extravasation by exposing adhesion molecules (such as P-selectin, E-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1) that facilitate the recruitment of leukocytes and platelets (47–50, 52). Hence, endothelial injury by proinflammation injury induces impaired permeability that subsequently activates the coagulation system, depicting the intertwined sepsis pathophysiology.

Figure 3.

Endothelial activation and coagulation dysfunction in sepsis. Weibel Palade bodies release P-selectin and VWF. ADAMTS13, a metalloprotease, cleaves highly procoagulant VWF multimers into lesser procoagulant forms. Platelets interact with activated neutrophils to induce NETs formation. NETs shift the balance toward excessive coagulation together with downregulation of anticoagulation and antifibrinolysis. The cascade of endothelial injury induces increased vascular permeability with associated coagulation abnormalities, altered microvascular flow, and micro thrombosis. This figure was created with BioRender.com. ADAMTS13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Under physiological conditions, the endothelium maintains the balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis to prevent systemic bleeding and clotting, maintaining hemostasis (53). The endothelium synthesizes and expresses molecules that are vital in regulating hemostasis, such as von Willebrand factor (VWF), tissue factor (TF), and plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1) (54–58). VWF, the main cargo of Weibel palade bodies, mediates platelet adhesion and aggregation (58, 59). Reduced levels of the VWF proteolytic scissor, ADAMTS13 antigen in sepsis promotes formation of small blood clots in the bloodstream and leads to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (58). P-selectin released by exocytosis with VWF is involved in leukocyte rolling and recruitment in inflammation, making VWF an acute phase response protein (60, 61). Activated endothelial cells and leukocytes express high TF levels stimulating the extrinsic clotting cascade by binding to factor VII, resulting in thrombin generation (62–64). The proteolytic inactivation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and reduced activation of protein C (PC) facilitates a prothrombotic phenotype (65). The elevated production of PAI-1 by endothelium suppresses the fibrinolytic pathway by inhibiting tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) (66). These defects increase the production of fibrin-rich microvascular clots in sepsis, predisposing the vessels to DIC.

The microcirculation constitutes arterioles, capillaries, and postcapillary venules, involved in the pathophysiological processes in sepsis, including endothelial dysfunction, activation of coagulation, loss of smooth muscle tone reactivity, and disordered leukocyte sequestration (67). The endothelial cells regulate the local distribution of blood flow and oxygen delivery through the release of vasodilators, especially nitric oxide (NO), modulating arteriolar smooth muscle cell tone (68). Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is known to be upregulated in sepsis but is heterogeneously expressed in the vascular beds, resulting in both hypo- and overperfusion that contributes to mismatched oxygen delivery (42, 69, 70). RBC velocity and supply rate in capillary networks is reduced in sepsis, as demonstrated by preclinical studies and human studies leading to impaired convective transport of oxygen (71–73). This is exacerbated by decreased functional capillary density and increased stopped-flow capillaries caused by reduced deformability of the RBCs and platelet-fibrin plugging (74, 75). The smooth muscle cells lining arterioles lose their ability to regulate perfusion and tone in sepsis (76). RBCs lose their ability to release vasodilators, impair RBC/O2 signaling, and causing decreased oxygen delivery during sepsis (77). Impaired oxygen delivery to the tissues fails to meet the oxygen demand, ensuing anaerobic glycolysis lactic acidosis.

COAGULATION AND COMPLEMENT DYSFUNCTION

The coagulation dysfunction in sepsis ranges from mild-subclinical to severe hematological dysfunction presenting as prolonged prothrombin time, increased D-dimer levels, and low platelet counts leading to DIC (78, 79). The etiology of the dysregulation of coagulation in sepsis involves two important innate immune cells: platelets and neutrophils. Stimulated platelets express P-selectin on their surface, facilitating platelet-leukocyte interactions through the receptor P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 on leukocytes facilitating cell trafficking and activation (80). Takei et al. (81) discovered neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in 1996 as a cell death mechanism different from apoptosis and necrosis. This cell death mechanism has a major prognostic impact on patients with sepsis, similar to apoptotic death (23, 28, 82–84). NETs are composed of extracellular chromatin wrapped around histones and numerous granular proteins (such as elastase and myeloperoxidase) engulfing the invading pathogens (85, 86). Most bacteria are killed readily by neutrophils; however, some bacterial pathogens can circumvent destruction by NETs (86, 87). Peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 (PAD4) citrullinates the histones and relaxes the chromatin releasing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) into the circulation (88). Platelets bind to neutrophils via the platelet Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) that stimulates NETs production (89). Similarly, histones during NETs generation can activate platelets via Toll-like 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 receptors (90). Consequently, platelet recruitment leads to NETs formation and clot growth that entraps bacteria in the microvasculature (91–93). Although NETs protect the host by limiting microbial growth and dissemination, excessive NETosis during sepsis can shift the hemostatic balance toward excessive coagulation, promoting thrombus formation (94–97). CfDNA enhances thrombin generation by activating the intrinsic pathway (94). Deoxyribonuclease, known to degrade CfDNA, improves sepsis mortality; however, its absence leads to vascular occlusion and organ damage (98–100). In addition, sepsis is characterized by a drop in platelet count due to their sequestration and consumption by microthrombi (101). The dysregulated immune response leads to systemic activation of blood coagulation to a variable degree inducing microvascular clotting due to massive thrombin and fibrin formation (102). This can manifest as DIC forming thrombi within small and medium vessels, leading to multiorgan failure (102). Therefore, platelets and neutrophils promote innate immune cell responses and procoagulant action. This depicts an interlinked immunothrombotic mechanism in sepsis.

Sepsis downregulates the anticoagulant and fibrinolytic mechanism of the body. NETs augment fibrinolysis, promote the stability of fibrin clots, and inhibit plasminogen activators (95–97). The activated PC is reduced due to the downregulation of endothelial cell protein C receptor and thrombomodulin, decreased production by the liver, and consumption due to ongoing coagulation during sepsis (103–105). Intravascular clotting and microvascular thrombosis result in secondary protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III consumption (106). Kudo et al. (107) established four clinical phenotypes based on the severity of coagulopathy characterized by low platelet counts, high levels of FDP and D-dimer, and high organ dysfunction scores in ICU patients. Similarly, the administration of recombinant human-activated protein C inhibits leukocyte-endothelial interaction, suppresses inflammatory cytokine production, and protects the microcirculation by inhibiting plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 modulating fibrinolysis (108, 109). Recently, suppression of fibrinolysis, termed “fibrinolytic shutdown,” has gained attention. An increase in the tissue plasminogen activator due to the significant increase in PAI-1 by endothelial cells results in fibrinolytic shutdown (110). In vivo models of endotoxemia have shown that fibrin deposition in the kidneys or adrenal glands is mainly attributed to plasminogen activators, downregulation of anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic pathways (111, 112). The inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1, and the complement system in sepsis models downregulate the anticoagulant pathways in sepsis (62). Thrombin also contributes to fibrinolysis resistance by alerting fibrin structures, making them more compact and less permeable (113). This can promote thrombus formation within small and medium vessels, leading to multiorgan failure. The emerging role of point-of-care coagulation tests has received attention to detect sepsis-induced coagulopathy necessary for prognosis and diagnosis (114).

THE COMPLEMENT SYSTEM IN SEPSIS

The innate immune system orchestrates a protective response against microbes by multiple players of the innate and adaptive with the complement system. Similar to other defense systems, the complement response becomes excessive and inappropriately stimulated in sepsis, leading to dysregulated and potentially harmful behavior (115, 116). The early stages of sepsis systematically activate the complement system generating a large amount of C3a and C5a (115, 116). Activated complement systems generate a proinflammatory response that increases vascular permeability and chemotaxis of leukocytes (117). The overwhelming activation of complement results in vascular leak and host tissue damage (118). Activated complement with endothelial activation disrupts cellular barriers, consequently forming edema in the brain, lung, and liver (118–121). Complement factors (such as C1q, C3a, and C5a) induce blood-brain barrier damage, increasing complement synthesis and leakage of serum complement proteins into the subarachnoid space of the central nervous system, consequently causing septic encephalopathy (122). However, the complements factors (specifically C3a and C5a) also have neuroregenerative effects apart from being neurotoxic, as they mediate the release of neurotrophins (123, 124). The cells lining the reticuloendothelial system in the liver can clear the complement proteins, protecting hepatocytes from complement-mediated injury; however, excessive activation consumes C5a at the later stages of sepsis, resulting in neutrophil dysfunction with impaired bactericidal activity (88, 125). Complement activation in the liver upregulates adhesion molecules, increasing the recruitment of leukocytes (126, 127). On leukocyte recruitment, C5a activates leukocytes to mount an oxidative burst with NADPH oxidase assembly and chemotactic response for phagocytosis and bacterial clearing (115, 116).

C5a also binds to a second receptor, apart from C5aR, a C5-like receptor (C5L2) (128). The C5L2 and C5aR receptors asynchronously shown to be downregulated on neutrophil’s surface during septic shock correlate to multiorgan failure development (128). The complement system is vital in cardiac malfunction during sepsis. The C5a interacts with C5a receptors on the surface of cardiomyocytes that downregulates Na+-K+-ATPase, sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, resulting in loss of calcium hemostasis, essential to maintain cardiac contractility (129, 130). Therefore, enhanced C5a is associated with impaired cardiac function, whereas the administration of C5a-specific blocking antibody reverses septic cardiomyopathy (131–134). The complement system also plays a vital role in coagulation with the immune system. C5b-9 terminal complex facilitates tissue factor expression by leukocytes, increasing thrombogenicity by simultaneous induction of coagulation (135). They also modify phospholipid membranes required for tissue factor expression (135, 136). Complement factors C5b-9 increase phosphatidylserine expression to provide a catalytic surface for prothrombinase on platelets, cleaving the prothrombin and generating thrombin (137, 138). Hence, the complement system can influence the coagulation pathway and innate response deleterious in sepsis.

INTERACTION OF ALL DOMAINS IN SEPSIS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Originally, it has been believed that sepsis is an inflammatory host response to infection; however, the inflammatory response activates the other systems, such as endothelial, complement, and coagulation. We believe that the pathophysiology of sepsis is complicated and intertwined due to several factors that play a role in the host response and the presenting symptoms of the patient. Some patients present with strong fighting responses, whereas others deteriorate to a dysregulated state of immunity. The endothelium forms a dynamic equilibrium between inflammation, innate immunity, complement, and coagulation to delicate a host response in sepsis (37). The cytokine storm during hyperinflammation damages the endothelium, causing dysregulated vascular tone, and impairing vascular permeability (38–42). Similarly, the endothelium contributes to proinflammation by recruiting inflammatory cells and releasing inflammatory mediators (53). The initial cytokine storm causes fever, shock, respiratory failure, and early death due to multiple organ dysfunction (16, 17). The complement system activation upregulates adhesion molecules increasing the recruitment of leukocytes and chemotactic response for phagocytosis and bacterial clearing (115, 116, 126, 127). The hypercoagulability of sepsis driven by the release of tissue factors from disrupted endothelial cells causes the systemic activation of the coagulation cascade (139). Activated neutrophils adhered to the injured endothelial cells release NETs that facilitate platelet aggregation (94–97). The subsequent activation of the coagulation system increases the production of fibrin-rich microvascular clots in sepsis. The microcirculatory dysfunction leads to loss of smooth muscle tone reactivity and peripheral vasodilation, ensuing organ hypoperfusion, impaired oxygen delivery to the tissues, and anaerobic glycolysis lactic acidosis (67). Therefore, the pathophysiology of sepsis is dysregulated response to infection that triggers cascades of interconnected systems. This cascade involves multiple players and requires detecting different biomarkers depending on the host status for early diagnosis.

EARLY SEPSIS DIAGNOSIS

The clinical transition from infection to sepsis is termed “time zero.” Early warning scores identify patients at high risk of clinical transition to sepsis and help to recognize critical changes in the patient’s condition; however, little is known about at which stage of sepsis this equilibrium is disrupted (140, 141). This tipping point varies from patient to patient and is likely impacted by host status (such as noncommunicable diseases, injuries, and infections), genetic predisposition, and pathogen type and burden (5, 16, 17, 19, 142, 143). The elderly with chronic comorbidities such as cancer and diabetes are at an increased risk of sepsis due to the functional impairment of cell-mediated immunity and humoral immune responses with age (5, 144). Often, early sepsis manifests as reduced capillary refill time, mottled skin, increased respiratory rate, and altered mental status; hypotension will then ensue, reflecting the onset of circulatory failure, followed by shock, respiratory and renal failure, and premature death due to multiple organ dysfunction (37).

Early resuscitation and antibiotic treatment are essential to reestablish organ perfusion (145). However, some patients fail to respond and exhibit depressed myocardial function and inadequate systemic oxygen delivery, increasing anaerobic glycolysis and lactate production (19, 142). Thus, the clinical manifestation of sepsis varies from patient to patient depending on the ability of the individual’s immune system to prevent and manage infections based on risk factors for sepsis.

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommends administrating intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1 h of blood culture results. Every 1-h delay in antibiotic administration is associated with increased in-hospital mortality among patients with sepsis in ED (146). To the best of our knowledge, there are only 11 studies using biomarkers to diagnose sepsis in the emergency department, and none looked at biomarkers involved in the complex pathophysiology (150–153, 156–158, 160–163). An ideal biomarker (or set of biomarkers) should become abnormal before clinical signs and symptoms develop and possess near-perfect sensitivity and specificity (147). This deficit identifies the poor understanding of sepsis pathophysiology and reflects the need to identify the gaps in the current knowledge on sepsis pathophysiology to diagnose sepsis. Procalcitonin (PCT) has been considered the promising biomarker clinically used to detect sepsis in the ED; still, it has a low positive predictive value and is downregulated in viral infections (148–151). Measuring monocyte distribution width is more accurate than PCT levels in ED sepsis diagnosis using the sepsis-3 definition (152, 153). Presepsin, also referred to as CD14 (cluster-of-differentiation) functions, a receptor for peptidoglycan with PCT, has a comparable performance with diagnosing sepsis in the ED (154). Similar to PCT, presepsin is specific for bacterial infections (especially Gram-negative) and gives false-positive results in certain conditions such as renal failure or burns (155). Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), an acute phase protein important in Gram-negative infection, has a diagnostic accuracy lower than that of PCT (156). Similarly, the performance of a proinflammatory mediator that binds and activates neutrophils, known as pancreatic stone protein, and an anti-inflammatory mediator, soluble CD25 (sCD25), has been comparable with PCT (153). Another observational study that used the older sepsis definition, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, found the diagnostic performance of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) greater than PCT in the ED (157). However, there have been many conflicting reports on using PCT as a biomarker with others. Interleukin-6 had a superior diagnostic value compared with PCT and even CRP in patients with ED diagnosed with sepsis (158). Neutrophil CD64 expression shows high specificity and positive predictive value in distinguishing sepsis from patients with no sepsis in the emergency department, making it an accurate biomarker for this purpose (162). Newer biomarkers have been studied for their role in early sepsis identification. They have focused on performance with PCT. None considered the complex pathophysiology of sepsis and biomarkers interlinked to each pathway. Most of these studies focused on the inflammation pathway (Table 1). In addition, the lack of progress in the early diagnosis of sepsis using a biomarker is attributed to finding a single most suitable marker. However, the host response in sepsis involves multiple players at various stages during the disease process. Inflammation and coagulation are critical in the host’s responses to infection (159). Given these complexities, future studies focusing on the immunothrombotic markers are important for early sepsis diagnosis.

Table 1.

Biomarkers for early diagnosis of sepsis

| Author, Yr | Number of Patients | Biomarkers | Biological Domain | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bo et al., 2013 (160) | 859 | Presepsin compared with PCT | Inflammation | Presepsin is a valuable biomarker for early diagnosis of sepsis, risk stratification, and evaluation of prognosis in patients with sepsis in the ED. |

| 2. | Laura et al., 2014 (151) | 513 | PCT, CRP, and WBC | Inflammation | CRP and PCT are reliable diagnostic and biomarkers compared with WBC and can be used in combination with severity clinical score. |

| 3. | Miaomiao et al., 2014 (157) | 480 | NGAL, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and PCT | Inflammation and endothelium | NGAL and TIMP-1 are valuable for early diagnosis of sepsis in the ED. |

| 4. | Caitlin et al., 2014 (150) | 66 | MRproADM, MRproANP, PCT, copeptin, and proET-1 | Endothelium and microcirculation | There were no differences between patients with septic and nonseptic for MRproADM, MRproANP, copeptin, or proET-1. Combination of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and PCT levels is useful for the early detection of sepsis in patients with ED. |

| 5. | *Xin et al., 2015 (161) | 1,815 | Presepsin | Inflammation | Presepsin exhibits a good diagnostic accuracy for sepsis compared with patients with systemic inflammatory disease. |

| 6. | Toh et al., 2016 (162) | 51 | sPLA2-IIA and CD64 | Inflammation | sPLA2-IIA showed superior performance in sepsis diagnosis compared with CD64. In distinguishing sepsis from nonsepsis groups. |

| 7. | Luis et al., 2017 (153) | 152 | PCT, PSP, and sCD25 levels | Inflammation | PSP and sCD25 were comparable with PCT to identify patients with sepsis in the ED. |

| 8. | Luis et al., 2018 (156) | 49 | LBP, CRP, and PCT | Inflammation | In adult patients with ED with suspected infection, the diagnostic accuracy for sepsis of LBP was similar to that of CRP but lower than that of PCT. |

| 9. | Juhyun et al., 2019 (158) | 142 | IL-6, PTX3, and PCT | Inflammation | The diagnostic value of IL-6 was superior to those of PTX3 and PCT for sepsis and septic shock. |

| 10. | Elliott et al., 2019 (163) | 2,158 | MDW and WBC count | Inflammation | MDW alone was effective for the early detection of sepsis in the ED. |

| 11. | Pierre et al., 2021 (152) | 1,517 | MDW, PCT, and CRP | Inflammation | MDW in combination with WBC has the diagnostic accuracy for diagnosis in the emergency department. |

*This is a systematic review. CRP, C-reactive protein; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; LBP, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein; MDW, monocyte distribution width; MRproADM, midregional proadrenomedullin; MRproANP, midregional proatrial natriuretic peptide; NGAL, neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated lipocalin; PCT, procalcitonin; ProET-1, proendothelin-1; PSP, pancreatic stone protein; PTX3, pentraxin 3; sPLA2-IIA, group II secretory phospholipase A2; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1; WBC, white blood cell.

CONCLUSIONS

The complex interaction between different biological domains in sepsis pathophysiology has been poorly understood. Sepsis has been known as a dysregulated reaction to infection; however, the switch from infection to sepsis involves the inflammation pathway that intersects with the coagulation system for endothelial stimulation and microcirculatory dysfunction. The early diagnosis is often difficult as the heterogeneity in the individual response is huge, and the signs and symptoms of sepsis are nonspecific. The development of validated biomarkers has been impossible due to the focus on inflammatory markers, whereas the pathophysiology involves multiple biological pathways at different levels. We show that immunothrombosis plays an important role in determining the switch from infection to sepsis and is crucial to fill the literature gap in the search for potential biomarkers for early sepsis diagnosis. Future studies using immunothrombosis markers for sepsis will help in determining the optimal duration of treatments, antibiotic stewardship, and novel diagnostic approaches to improve care.

GRANTS

A.F.-R. received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for Canadian Sepsis Research Network: Improving Care Before, During and After Sepsis (Grant No. RN391741-430986).

DISCLOSURES

No other conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A. prepared figures; J.A. drafted manuscript; J.A., A.A.M., and A.F.-R. edited and revised manuscript; J.A., A.A.M., and A.F.-R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315: 801–810, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farrah K, McIntyre L, Doig CJ, Talarico R, Taljaard M, Krahn M, Fergusson D, Forster AJ, Coyle D, Thavorn K. Sepsis-associated mortality, resource use, and healthcare costs: a propensity-matched cohort study. Crit Care Med 49: 215–227, 2021. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang HE, Shapiro NI, Angus DC, Yealy DM. National estimates of severe sepsis in United States emergency departments. Crit Care Med 35: 1928–1936, 2007. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000277043.85378.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NKJ, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, Angus DC, Reinhart K; International Forum of Acute Care Trialists. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193: 253–272, 2016. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer S, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Machado FR, Reinhart KK, Rowan K, Seymour CW, Watson RS, West TE, Marinho F, Hay SI, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Angus DC, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 395: 200–211, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prescott HC, Osterholzer JJ, Langa KM, Angus DC, Iwashyna TJ. Late mortality after sepsis: propensity matched cohort study. BMJ 353: i2375, 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 31: 2316–2323, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085178.80226.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yende S, Austin S, Rhodes A, Finfer S, Opal S, Thompson T, Bozza FA, LaRosa SP, Ranieri VM, Angus DC. Long-term quality of life among survivors of severe sepsis: analyses of two international trials. Crit Care Med 44: 1461–1467, 2016. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Kadri SS, Angus DC, Danner RL, Fiore AE, Jernigan JA, Martin GS, Septimus E, Warren DK, Karcz A, Chan C, Menchaca JT, Wang R, Gruber S, Klompas M; CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA 318: 1241–1249, 2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leligdowicz A, Matthay MA. Heterogeneity in sepsis: new biological evidence with clinical applications. Crit Care 23: 80, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iskander KN, Osuchowski MF, Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Kurosawa S, Stepien D, Valentine C, Remick DG. Sepsis: multiple abnormalities, heterogeneous responses, and evolving understanding. Physiol Rev 93: 1247–1288, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 41: 580–637, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 30: 16–34, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumar S, Ingle H, Prasad DVR, Kumar H. Recognition of bacterial infection by innate immune sensors. Crit Rev Microbiol 39: 229–246, 2013. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.706249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Ferguson TA. The sepsis seesaw: tilting toward immunosuppression. Nat Med 15: 496–497, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osuchowski MF, Welch K, Siddiqui J, Remick DG. Circulating cytokine/inhibitor profiles reshape the understanding of the SIRS/CARS continuum in sepsis and predict mortality. J Immunol 177: 1967–1974, 2006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nedeva C, Menassa J, Puthalakath H. Sepsis: inflammation is a necessary evil. Front Cell Dev Biol 7: 108, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doganyigit Z, Eroglu E, Akyuz E. Inflammatory mediators of cytokines and chemokines in sepsis: from bench to bedside. Hum Exp Toxicol 41: 09603271221078871, 2022. doi: 10.1177/09603271221078871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Revelly JP, Tappy L, Martinez A, Bollmann M, Cayeux MC, Berger MM, Chioléro RL. Lactate and glucose metabolism in severe sepsis and cardiogenic shock. Crit Care Med 33: 2235–2240, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181525.99295.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brady J, Horie S, Laffey JG. Role of the adaptive immune response in sepsis. Intensive Care Med Exp 8: 20, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s40635-020-00309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Grayson MH, Osborne DF, Wagner TH, Cobb JP, Coopersmith C, Karl IE. Depletion of dendritic cells, but not macrophages, in patients with sepsis. J Immunol 168: 2493–2500, 2002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med 27: 1230–1251, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Schmieg RE, Hui JJ, Chang KC, Osborne DF, Freeman BD, Cobb JP, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J Immunol 166: 6952–6963, 2001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cao C, Yu M, Chai Y. Pathological alteration and therapeutic implications of sepsis-induced immune cell apoptosis. Cell Death Dis 10: 782, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma A, Yang WL, Matsuo S, Wang P. Differential alterations of tissue T-cell subsets after sepsis. Immunol Lett 168: 41–50, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inoue S, Suzuki-Utsunomiya K, Okada Y, Taira T, Iida Y, Miura N, Tsuji T, Yamagiwa T, Morita S, Chiba T, Sato T, Inokuchi S. Reduction of immunocompetent T cells followed by prolonged lymphopenia in severe sepsis in the elderly. Crit Care Med 41: 810–819, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318274645f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hohlstein P, Gussen H, Bartneck M, Warzecha KT, Roderburg C, Buendgens L, Trautwein C, Koch A, Tacke F. Prognostic relevance of altered lymphocyte subpopulations in critical illness and sepsis. J Clin Med 8: 353, 2019. [Erratum in J Clin Med 8: 1296, 2019]. doi: 10.3390/jcm8030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Monserrat J, de Pablo R, Diaz-Martín D, Rodríguez-Zapata M, de la Hera A, Prieto A, Alvarez-Mon M. Early alterations of B cells in patients with septic shock. Crit Care 17: R105, 2013. doi: 10.1186/cc12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Felmet KA, Hall MW, Clark RSB, Jaffe R, Carcillo JA. Prolonged lymphopenia, lymphoid depletion, and hypoprolactinemia in children with nosocomial sepsis and multiple organ failure. J Immunol 174: 3765–3772, 2005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin MD, Badovinac VP, Griffith TS. CD4 T cell responses and the sepsis-induced immunoparalysis state. Front Immunol 11: 1364, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen X, Ye J, Ye J. Analysis of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets and prognosis in patients with septic shock. Microbiol Immunol 55: 736–742, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Srivastava A, Swanson PE, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 306: 2594–2605, 2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Sullivan ST, Lederer JA, Horgan AF, Chin DH, Mannick JA, Rodrick ML. Major injury leads to predominance of the T helper-2 lymphocyte phenotype and diminished interleukin-12 production associated with decreased resistance to infection. Ann Surg 222: 482–492, 1995. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199522240-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Venet F, Pachot A, Debard AL, Bohe J, Bienvenu J, Lepape A, Powell WS, Monneret G. Human CD4 + CD25 + regulatory t lymphocytes inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced monocyte survival through a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. J Immunol 177: 6540–6547, 2006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Venet F, Chung CS, Kherouf H, Geeraert A, Malcus C, Poitevin F, Bohé J, Lepape A, Ayala A, Monneret G. Increased circulating regulatory T cells (CD4(+)CD25 (+)CD127 (-)) contribute to lymphocyte anergy in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med 35: 678–686, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Otto GP, Sossdorf M, Claus RA, Rödel J, Menge K, Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC. The late phase of sepsis is characterized by an increased microbiological burden and death rate. Crit Care 15: R183–R183, 2011. doi: 10.1186/cc10332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Opal SM, van der Poll T. Endothelial barrier dysfunction in septic shock. J Intern Med 277: 277–293, 2015. doi: 10.1111/joim.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ince C, Mayeux PR, Nguyen T, Gomez H, Kellum JA, Ospina-Tascón GA, Hernandez G, Murray P, De Backer D; ADQI XIV Workgroup. The endothelium in sepsis. Shock 45: 259–270, 2016. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goldenberg NM, Steinberg BE, Slutsky AS, Lee WL. Broken barriers: a new take on sepsis pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med 3: 88ps25, 2011. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dejana E, Orsenigo F. Endothelial adherens junctions at a glance. J Cell Sci 126: 2545–2549, 2013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muradashvili N, Tyagi R, Lominadze D. A dual-tracer method for differentiating transendothelial transport from paracellular leakage in vivo and in vitro. Front Physiol 3: 166, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ince C, Sinaasappel M. Microcirculatory oxygenation and shunting in sepsis and shock. Crit Care Med 27: 1369–1377, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klijn E, den Uil CA, Bakker J, Ince C. The heterogeneity of the microcirculation in critical illness. Clin Chest Med 29: 643–654, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circ Res 100: 174–190, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a006429, 2012. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ushiyama A, Kataoka H, Iijima T. Glycocalyx and its involvement in clinical pathophysiologies. J Intensive Care 4: 59, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Newman W, Beall LD, Carson CW, Hunder GG, Graben N, Randhawa ZI, Gopal TV, Wiener-Kronish J, Matthay MA. Soluble E-selectin is found in supernatants of activated endothelial cells and is elevated in the serum of patients with septic shock. J Immunol 150: 644–654, 1993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.150.2.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell 76: 301–314, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Osborn L. Leukocyte adhesion to endothelium in inflammation. Cell 62: 3–6, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90230-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bevilacqua MP, Stengelin S, Gimbrone MA Jr, Seed B. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1: an inducible receptor for neutrophils related to complement regulatory proteins and lectins. Science 243: 1160–1165, 1989. doi: 10.1126/science.2466335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. VLeligdowicz A, Chun LF, Jauregui A, Vessel K, Liu KD, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Human pulmonary endothelial cell permeability after exposure to LPS-stimulated leukocyte supernatants derived from patients with early sepsis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L638–L644, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00286.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ley K, Reutershan J. Leucocyte-endothelial interactions in health and disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol 176: 97–133, 2006. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36028-x_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Hinsbergh VWM. Endothelium–role in regulation of coagulation and inflammation. Semin Immunopathol 34: 93–106, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Berriman JA, Li S, Hewlett LJ, Wasilewski S, Kiskin FN, Carter T, Hannah MJ, Rosenthal PB. Structural organization of Weibel-Palade bodies revealed by cryo-EM of vitrified endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17407–17412, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902977106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Colucci M, Balconi G, Lorenzet R, Pietra A, Locati D, Donati MB, Semeraro N. Cultured human endothelial cells generate tissue factor in response to endotoxin. J Clin Invest 71: 1893–1896, 1983. doi: 10.1172/jci110945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mackman N. The many faces of tissue factor. J Thromb Haemost 7: 136–139, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Turner NA, Nolasco L, Ruggeri ZM, Moake JL. Endothelial cell ADAMTS-13 and VWF: production, release, and VWF string cleavage. Blood 114: 5102–5111, 2009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Levi M, Scully M, Singer M. The role of ADAMTS-13 in the coagulopathy of sepsis. J Thromb Haemost 16: 646–651, 2018. doi: 10.1111/jth.13953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boneu B, Abbal M, Plante J, Bierme R. Factor-VIII complex and endothelial damage. Lancet 1: 1430, 1975. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Methia N, André P, Denis C, Economopoulos M, Wagner DD. Localized reduction of atherosclerosis in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice. Blood 98: 1424–1428, 2001. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Denis C, André P, Saffaripour S, Wagner DD. Defect in regulated secretion of P-selectin affects leukocyte recruitment in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4072–4077, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061307098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pawlinski R, Mackman N. Cellular sources of tissue factor in endotoxemia and sepsis. Thromb Res 125: S70–S73, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kalafatis M, Swords NA, Rand MD, Mann KG. Membrane-dependent reactions in blood coagulation: role of the vitamin K-dependent enzyme complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1227: 113–129, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Komiyama Y, Pedersen AH, Kisiel W. Proteolytic activation of human factors IX and X by recombinant human factor VIIa: effects of calcium, phospholipids, and tissue factor. Biochemistry 29: 9418–9425, 1990. doi: 10.1021/bi00492a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Faust SN, Levin M, Harrison OB, Goldin RD, Lockhart MS, Kondaveeti S, Laszik Z, Esmon CT, Heyderman RS. Dysfunction of endothelial protein C activation in severe meningococcal sepsis. N Engl J Med 345: 408–416, 2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108093450603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Murakami J, Ohtani A, Murata S. Protective effect of T-686, an inhibitor of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 production, against the lethal effect of lipopolysaccharide in mice. Jpn J Pharmacol 291: 291–294, 1997. doi: 10.1254/jjp.75.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pries AR, Secomb TW. Blood flow in microvascular networks. Microcirculation 67: 826–834, 2008. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-374530-9.00001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morelli A, Passariello M. Hemodynamic coherence in sepsis. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 30: 453–463, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tsai AG, Acero C, Nance PR, Cabrales P, Frangos JA, Buerk DG, Intaglietta M. Elevated plasma viscosity in extreme hemodilution increases perivascular nitric oxide concentration and microvascular perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1730–H1739, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Takatani Y, Ono K, Suzuki H, Inaba M, Sawada M, Matsuda N. Inducible nitric oxide synthase during the late phase of sepsis is associated with hypothermia and immune cell migration. Lab Invest 98: 629–639, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ellis CG, Bateman RM, Sharpe MD, Sibbald WJ, Gill R. Effect of a maldistribution of microvascular blood flow on capillary O2 extraction in sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H156–H164, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dilken O, Ergin B, Ince C. Assessment of sublingual microcirculation in critically ill patients: consensus and debate. Ann Transl Med 8: 793, 2020. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Sprague RS. Role of erythrocyte-released ATP in the regulation of microvascular oxygen supply in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 216: 265–276, 2016. doi: 10.1111/apha.12596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bateman RM, Jagger JE, Sharpe MD, Ellsworth ML, Mehta S, Ellis CG. Erythrocyte deformability is a nitric oxide-mediated factor in decreased capillary density during sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2848–H2856, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ellis CG, Jagger J, Sharpe M. The microcirculation as a functional system. Crit Care 9: S3–S8, 2005. doi: 10.1186/cc3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Price SA, Spain DA, Wilson MA, Harris PD, Garrison RN. Subacute sepsis impairs vascular smooth muscle contractile machinery and alters vasoconstrictor and dilator mechanisms. J Surg Res 12: 165–176, 1999. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bateman RM, Sharpe MD, Jagger JE, Ellis CG. Sepsis impairs microvascular autoregulation and delays capillary response within hypoxic capillaries. Crit Care 19: 385, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1102-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Iba T, Levy JH. Sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Anesthesiology 132: 1238–1245, 2020. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Iba T, Umemura Y, Wada H, Levy JH. Roles of coagulation abnormalities and microthrombosis in sepsis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Arch Med Res 52: 788–797, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zimmerman GA. Two by two: the pairings of P-selectin and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10023–10024, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Takei H, Araki A, Watanabe H, Ichinose A, Sendo F. Rapid killing of human neutrophils by the potent activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) accompanied by changes different from typical apoptosis or necrosis. J Leukoc Biol 59: 229–240, 1996. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 813–822, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wu HP, Chung K, Lin CY, Jiang BY, Chuang DY, Liu YC. Associations of T helper 1, 2, 17 and regulatory T lymphocytes with mortality in severe sepsis. Inflamm Res 62: 751–763, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Andreu-Ballester JC, Tormo-Calandín C, Garcia-Ballesteros C, Pérez-Griera J, Amigó V, Almela-Quilis A, Ruiz del Castillo J, Peñarroja-Otero C, Ballester F. Association of γδ T cells with disease severity and mortality in septic patients. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20: 738–746, 2013. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00752-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 176: 231–241, 2007. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303: 1532–1535, 2004. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kobayashi SD, Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Neutrophils and bacterial immune evasion. J Innate Immun 10: 432–441, 2018. doi: 10.1159/000487756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, Correll S, Li P, Wang D, Hayama R, Leonelli L, Han H, Grigoryev SA, Allis CD, Coonrod SA. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol 184: 205–213, 2009. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, Keys EM, Allen-Vercoe E, Devinney R, Doig CJ, Green FH, Kubes P. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med 13: 463–469, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: Involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood 118: 1952–1961, 2011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. McDonald B, Davis RP, Kim SJ, Tse M, Esmon CT, Kolaczkowska E, Jenne CN. Platelets and neutrophil extracellular traps collaborate to promote intravascular coagulation during sepsis in mice. Blood 129: 1357–1367, 2017. [Erratum in Blood 139: 952, 2022]. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-741298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jenne CN, Wong CHY, Petri B, Kubes P. The use of spinning-disk confocal microscopy for the intravital analysis of platelet dynamics in response to systemic and local inflammation. PLoS One 6: e25109, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 12: 324–333, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gould TJ, Vu TT, Swystun LL, Dwivedi DJ, Mai SHC, Weitz JI, Liaw PC. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 1977–1984, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gould TJ, Vu TT, Stafford AR, Dwivedi DJ, Kim PY, Fox-Robichaud AE, Weitz JI, Liaw PC. Cell-free DNA modulates clot structure and impairs fibrinolysis in sepsis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 2544–2553, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Longstaff C, Varjú I, Sótonyi P, Szabó L, Krumrey M, Hoell A, Bóta A, Varga Z, Komorowicz E, Kolev K. Mechanical stability and fibrinolytic resistance of clots containing fibrin, DNA, and histones. J Biol Chem 288: 6946–6956, 2013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Komissarov AA, Florova G, Idell S. Effects of extracellular DNA on plasminogen activation and fibrinolysis. J Biol Chem 286: 41949–41962, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.301218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jhelum H, Sori H, Sehgal D. A novel extracellular vesicle-associated endodeoxyribonuclease helps Streptococcus pneumoniae evade neutrophil extracellular traps and is required for full virulence. Sci Rep 8: 7985, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25865-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lauková L, Konečná B, Bábíčková J, Wagnerová A, Melišková V, Vlková B, Celec P. Exogenous deoxyribonuclease has a protective effect in a mouse model of sepsis. Biomed Pharmacother 93: 8–16, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Jiménez-Alcázar M, Rangaswamy C, Panda R, Bitterling J, Simsek YJ, Long AT, Bilyy R, Krenn V, Renné C, Renné T, Kluge S, Panzer U, Mizuta R, Mannherz HG, Kitamura D, Herrmann M, Napirei M, Fuchs TA. Host DNases prevent vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps. Science 358: 1202–1206, 2017. doi: 10.1126/science.aam8897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Levi M, Löwenberg EC. Thrombocytopenia in critically ill patients. Semin Thromb Hemost 34: 417–424, 2008. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1092871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Semeraro N, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Colucci M. Sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation and thromboembolic disease. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2: e2010024, 2010. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2010.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Xu J, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J Thromb Haemos 118: 1952–1961, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Taylor FB Jr, Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Kurosawa S, Ferrell G, Chang AC, Laszik Z, Kosanke S, Peer G, Esmon CT. The endothelial cell protein C receptor aids in host defense against Escherichia coli sepsis. Blood 95: 1680–1686, 2000. doi: 10.1182/blood.V95.5.1680.005k33_1680_1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dhainaut JF, Marin N, Vinsonneau MA, Sprung C. C. Hepatic response to sepsis: Interaction between coagulation and inflammatory processes. Crit Care Med 29, Suppl 7: S42–S47, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Simmons J, Pittet JF. The coagulopathy of acute sepsis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 28: 227–236, 2015. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kudo D, Goto T, Uchimido R, Hayakawa M, Yamakawa K, Abe T, Shiraishi A, Kushimoto S. Coagulation phenotypes in sepsis and effects of recombinant human thrombomodulin: an analysis of three multicentre observational studies. Crit Care 25: 114, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Iba T, Kidokoro A, Fukunaga M, Nagakari K, Shirahama A, Ida Y. Activated protein C improves the visceral microcirculation by attenuating the leukocyte-endothelial interaction in a rat lipopolysaccharide model. Crit Care Med 33: 368–372, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000153415.04995.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Anastasiou G, Gialeraki A, Merkouri E, Politou M, Travlou A. Thrombomodulin as a regulator of the anticoagulant pathway: implication in the development of thrombosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 23: 1–10, 2012. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834cb271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Madoiwa S. Recent advances in disseminated intravascular coagulation: endothelial cells and fibrinolysis in sepsis-induced DIC. J Intensive Care 3: 8, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0075-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. van der Poll T, de Jonge E, Levi M. Regulatory role of cytokines in disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Thromb Hemost 27: 639–651, 2001. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Silasi-Mansat R, Zhu H, Popescu NI, Peer G, Sfyroera G, Magotti P, Ivanciu L, Lupu C, Mollnes TE, Taylor FB, Kinasewitz G, Lambris JD, Lupu F. Complement inhibition decreases the procoagulant response and confers organ protection in a baboon model of Escherichia coli sepsis. Blood 116: 1002–1010, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-269746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Campbell RA, Overmyer KA, Selzman CH, Sheridan BC, Wolberg AS. Contributions of extravascular and intravascular cells to fibrin network formation, structure, and stability. Blood 114: 4886–4889, 2009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-228940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Kim H. Emerging role of the point-of-care coagulation test in sepsis. Korean J Anesthesiol 73: 177–178, 2020. doi: 10.4097/kja.20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Xu R, Lin F, Bao C, Wang FS. Mechanism of C5a-induced immunologic derangement in sepsis. Cell Mol Immunol 14: 792–793, 2017. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Albrecht EA, Ward PA. Complement-induced impairment of the innate immune system during sepsis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 7: 349–354, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ward PA. Role of the complement in experimental sepsis. J Leukoc Biol 83: 467–470, 2008. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature 420: 885–891, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zhang C, Lee JY, Keep RF, Pandey A, Chaudhary N, Hua Y, Xi G. Brain edema formation and complement activation in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl 118: 157–161, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1434-6_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Nuytinck JKS, Goris RJA, Weerts JGE, Schillings PH, Stekhoven JH. Acute generalized microvascular injury by activated complement and hypoxia: the basis of the adult respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure? Br J Exp Pathol 67: 537–548, 1986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Hofer J, Rosales A, Fischer C, Giner T. Extra-renal manifestations of complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathies. Front Pediatr 2: 97, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Lynch NJ, Willis CL, Nolan CC, Roscher S, Fowler MJ, Weihe E, Ray DE, Schwaeble WJ. Microglial activation and increased synthesis of complement component C1q precedes blood-brain barrier dysfunction in rats. Mol Immunol 40: 709–716, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Osaka H, Mukherjee P, Aisen PS, Pasinetti GM. Complement-derived anaphylatoxin C5a protects against glutamate- mediated neurotoxicity. J Cell Biochem 73: 303–311, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Heese K, Hock C, Otten U. Inflammatory signals induce neurotrophin expression in human microglial cells. J Neurochem 70: 699–707, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Koch CA, Kanazawa A, Nishitai R, Knudsen BE, Ogata K, Plummer TB, Butters K, Platt JL. Intrinsic resistance of hepatocytes to complement-mediated injury. J Immunol 174: 7302–7309, 2005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 340: 448–454, 1999. [Erratum in N Engl J Med 340: 1376, 1999]. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Ala A, Dhillon AP, Hodgson HJ. Role of cell adhesion molecules in leukocyte recruitment in the liver and gut. Int J Exp Pathol 84: 1–16, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2003.00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Yan C, Gao H. New insights for C5a and C5a receptors in sepsis. Front Immunol 3: 368, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Zhang T, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Cardiomyocyte calcium and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: friends or foes? Recent Prog Horm Res 59: 141–168, 2004. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Kalbitz M, Fattahi F, Grailer JJ, Jajou L, Malan EA, Zetoune FS, Huber-Lang M, Russell MW, Ward PA. Complement-induced activation of the cardiac NLRP3 inflammasome in sepsis. FASEB J 30: 3997–4006, 2016. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600728R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Niederbichler AD, Hoesel LM, Westfall MV, Gao H, Ipaktchi KR, Sun L, Zetoune FS, Su GL, Arbabi S, Sarma JV, Wang SC, Hemmila MR, Ward PA. An essential role for complement C5a in the pathogenesis of septic cardiac dysfunction. J Exp Med 203: 53–61, 2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Kalbitz M, Fattahi F, Herron TJ, Grailer JJ, Jajou L, Lu H, Huber-Lang M, Zetoune FS, Sarma JV, Day SM, Russell MW, Jalife J, Ward PA. Complement destabilizes cardiomyocyte function in vivo after polymicrobial sepsis and in vitro. J Immunol 197: 2353–2361, 2016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Huber-Lang MS, Sarma J, McGuire SR, Lu KT, Guo RF, Padgaonkar VA, Younkin EM, Laudes IJ, Riedemann NC, Younger JG, Ward PA. Protective effects of anti-C5a peptide antibodies in experimental sepsis. FASEB J 15: 568–570, 2001. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0653fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Hoesel LM, Niederbichler AD, Ward PA. Complement-related molecular events in sepsis leading to heart failure. Mol Immunol 44: 95–102, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Muhlfelder TW, Niemetz J, Kreutzer D, Beebe D, Ward PA, Rosenfeld SI. C5 chemotactic fragment induces leukocyte production of tissue factor activity: a link between complement and coagulation. J Clin Invest 63: 147–150, 1979. doi: 10.1172/JCI109269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Esmon CT. The impact of the inflammatory response on coagulation. Thromb Res 114: 321–327, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Krarup A, Wallis R, Presanis JS, Gál P, Sim RB. Simultaneous activation of complement and coagulation by MBL-associated serine protease 2. PLoS One 2: e623, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Sims PJ, Faioni EM, Wiedmer T, Shattil SJ. Complement proteins C5b-9 cause release of membrane vesicles from the platelet surface that are enriched in the membrane receptor for coagulation factor Va and express prothrombinase activity. J Biol Chem 263: 18205–18212, 1988. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Semeraro N, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Colucci M. Coagulopathy of acute sepsis. Semin Thromb Hemost 28: 227–236, 2015. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Minasyan H. Sepsis and septic shock: pathogenesis and treatment perspectives. J Crit Care 40: 229–242, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Howell MD, Donnino M, Clardy P, Talmor D, Shapiro NI. Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection. Intensive Care Med 33: 1892–1899, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Kline JA, Thornton LR, Lopaschuk GD, Barbee RW, Watts JA. Lactate improves cardiac efficiency after hemorrhagic shock. Shock 14: 215–221, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Martin-Loeches I, Guia MC, Vallecoccia MS, Suarez D, Ibarz M, Irazabal M, Ferrer R, Artigas A. Risk factors for mortality in elderly and very elderly critically ill patients with sepsis: a prospective, observational, multicenter cohort study. Ann Intensive Care 9: 26, 2019. [Erratum in Ann Intensive Care 9: 36, 2019]. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Martín S, Pérez A, Aldecoa C. Sepsis and immunosenescence in the elderly patient: a review. Front Med (Lausanne) 4: 20, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med 43: 304–377, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Liu VX, Fielding-Singh V, Greene JD, Baker JM, Iwashyna TJ, Bhattacharya J, Escobar GJ. The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 856–863, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1848OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Mayeux R. Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. NeuroRx 1: 182–188, 2004. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Lee WJ, Woo SH, Kim DH, Seol SH, Park SK, Choi SP, Jekarl DW, Lee SO. Are prognostic scores and biomarkers such as procalcitonin the appropriate prognostic precursors for elderly patients with sepsis in the emergency department? Aging Clin Exp Res 28: 917–924, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0500-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Becker KL, Nylén ES, White JC, Müller B, Snider RHJ. Clinical review 167: procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 1512–1525, 2004. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Hicks CW, Engineer RS, Benoit JL, Dasarathy S, Christenson RH, Peacock WF. Procalcitonin as a biomarker for early sepsis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 21: 112–117, 2014. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328361fee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Magrini L, Gagliano G, Travaglino F, Vetrone F, Marino R, Cardelli P, Salerno G, Di Somma S. Comparison between white blood cell count, procalcitonin and C reactive protein as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of infection or sepsis in patients presenting to the emergency department. Clin Chem Lab Med 52: 1465–1472, 2014. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Hausfater P, Boter NR, Indiano CM, Cancella de Abreu M, Marin AM, Pernet J, Quesada D, Castro I, Careaga D, Arock M, Tejidor L, Velly L. Monocyte distribution width (MDW) performance as an early sepsis indicator in the emergency department: comparison with CRP and procalcitonin in a multicenter international European prospective study. Crit Care 25: 227, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03622-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. García de Guadiana-Romualdo L, Berger M, Jiménez-Santos E, Rebollo-Acebes S, Jiménez-Sánchez R, Esteban-Torrella P, Hernando-Holgado A, Ortín-Freire A, Albaladejo-Otón MD. Pancreatic stone protein and soluble CD25 for infection and sepsis in an emergency department. Eur J Clin Invest 47: 297–304, 2017. doi: 10.1111/eci.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. de Guadiana Romualdo LG, Torrella PE, Acebes SR, Otón MDA, Sánchez RJ, Holgado AH, Santos EJ, Freire AO. Diagnostic accuracy of presepsin (sCD14-ST) as a biomarker of infection and sepsis in the emergency department. Clin Chim Acta 464: 6–11, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Piccioni A, Santoro MC, de Cunzo T, Tullo G, Cicchinelli S, Saviano A, Valletta F, Pascale MM, Candelli M, Covino M, Franceschi F. Presepsin as early marker of sepsis in emergency department: a narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas) 57: 770, 2021. doi: 10.3390/medicina57080770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. García de Guadiana Romualdo L, Albaladejo Otón MD, Rebollo Acebes S, Esteban Torrella P, Hernando Holgado A, Jiménez Santos E, Jiménez Sánchez R, Ortón Freire A. Diagnostic accuracy of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein for sepsis in patients with suspected infection in the emergency department. Ann Clin Biochem 55: 143–148, 2018. doi: 10.1177/0004563217694378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Wang M, Zhang Q, Zhao X, Dong G, Li C. Diagnostic and prognostic value of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 for sepsis in the emergency department: an observational study. Crit Care 18: 634, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Song J, Park DW, Moon S, Cho HJ, Park JH, Seok H, Choi WS. Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6, pentraxin 3, and procalcitonin levels among sepsis and septic shock patients: a prospective controlled study according to the Sepsis-3 definitions. BMC Infect Dis 19: 968, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Martinod K, Deppermann C. Immunothrombosis and thromboinflammation in host defense and disease. Platelets 32: 314–324, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1817360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Liu B, Chen YX, Yin Q, Zhao YZ, Li CS. Diagnostic value and prognostic evaluation of Presepsin for sepsis in an emergency department. Crit Care 17: R244, 2013. doi: 10.1186/cc13070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Zhang X, Liu D, Liu YN, Wang R, Xie LX. The accuracy of presepsin (sCD14-ST) for the diagnosis of sepsis in adults: A meta-analysis. Crit Care 19: 323, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Tan TL, Ahmad NS, Nasuruddin DN, Ithnin A, Arifin KT, Zaini IZ, Wan Ngah WZ. CD64 and group II secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA) as biomarkers for distinguishing adult sepsis and bacterial infections in the emergency department. PLoS One 11: e0152065, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Crouser ED, Parrillo JE, Seymour CW, Angus DC, Bicking K, Esguerra VG, Peck-Palmer OM, Magari RT, Julian MW, Kleven JM, Raj PJ, Procopio G, Careaga D, Tejidor L. Monocyte distribution width: a novel indicator of sepsis-2 and sepsis-3 in high-risk emergency department patients. Crit Care Med 47: 1018–1025, 2019. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]