Abstract

Cognitive impairment is one of the most prevalent symptoms of post Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COronaVirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) state, which is known as Long COVID. Advanced neuroimaging techniques may contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiological brain changes and the underlying mechanisms in post-COVID-19 subjects. We aimed at investigating regional cerebral perfusion alterations in post-COVID-19 subjects who reported a subjective cognitive impairment after a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection, using a non-invasive Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) MRI technique and analysis. Using MRI-ASL image processing, we investigated the brain perfusion alterations in 24 patients (53.0 ± 14.5 years, 15F/9M) with persistent cognitive complaints in the post COVID-19 period. Voxelwise and region-of-interest analyses were performed to identify statistically significant differences in cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps between post-COVID-19 patients, and age and sex matched healthy controls (54.8 ± 9.1 years, 13F/9M). The results showed a significant hypoperfusion in a widespread cerebral network in the post-COVID-19 group, predominantly affecting the frontal cortex, as well as the parietal and temporal cortex, as identified by a non-parametric permutation testing (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected with TFCE). The hypoperfusion areas identified in the right hemisphere regions were more extensive. These findings support the hypothesis of a large network dysfunction in post-COVID subjects with cognitive complaints. The non-invasive nature of the ASL-MRI method may play an important role in the monitoring and prognosis of post-COVID-19 subjects.

Subject terms: Biomedical engineering, Neurology

Introduction

There is growing evidence of a post COronaVIrus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) state, known as Long COVID, characterised by long-term complications or symptoms persisting for at least 4 weeks following Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COronaVirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, most recently defined as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 or post-acute COVID-191–3. Long term complications were observed in more than 30% of subjects affected by COVID-194, including those who have had less severe forms of COVID-19 and the asymptomatics5. Post-COVID-19 results in a broad range of manifestations, affecting several organs and systems in the body, often including the central or the peripheral nervous system in a significant proportion of patients.

The most frequent neurological manifestations of post-COVID-19 include increased fatigue, diffuse myalgia, ageusia, anosmia, headache, sleep disturbances dysautonomia and cognitive impairment1,6–9. Particularly, cognitive impairment has being increasingly recognised as a long-term sequela of the COVID-197,10–13. Recent follow-up investigations reported prevalence of cognitive deficits in 36% of patients at 3 months10,11 and 10 months7 after infection.

The mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of post-COVID-19 neurologic symptoms are still debated. Advanced functional neuroimaging techniques may contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiological brain changes in post-COVID-19 subjects by identifying the metabolic and perfusion alterations in affected brain regions. Several recent 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) studies reported hypometabolism in several brain regions in post-COVID-19 patients with persistent functional symptoms, including cognitive deficit12,14–19. In the light of the detected metabolic alterations assessed with nuclear imaging techniques, the identification of brain perfusion patterns would provide additional information to better understand the underlying mechanisms of COVID-19 neurological sequelae. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is correlated to cerebral metabolic rate and brain functional activity, since it affects the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissues20.

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is a relatively new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique to measure CBF, which is increasingly being used to investigate brain perfusion in subjects affected by neurological diseases21–25. This noninvasive MRI method uses arterial blood water as an endogenous tracer to measure tissue perfusion26,27 and it is able to detect affected brain regions in subjects with cognitive impairment28. Recently, an ASL study detected a hypoperfusion in subcortical regions in adults who previously self-isolated at home due to COVID-19 disease compared to non-COVID-19 controls who experienced flu-like symptoms29.

Thus, the advanced neuroimaging techniques and processing might contribute to identify the perfusion alterations underlying the symptoms of COVID-19 neurological sequelae.

The aim of the present study was to investigate regional cerebral perfusion abnormalities in post-COVID-19 subjects who reported a subjective cognitive impairment after a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in comparison to healthy controls using an MRI-ASL technique.

Materials and methods

Study population and protocol

In this study, we investigated the brain perfusion alterations by MRI-ASL image processing in patients with neuro-cognitive sequelae of COVID-19. We included consecutive subjects admitted to the post-COVID neurological outpatient clinic of the University Hospital of Trieste, Italy, between 1 September 2021 and 31 January 2022 with presence of self-reported cognitive impairment in the post-acute COVID-19 period. The inclusion criteria was the persistent or ex-novo cognitive impairment at least after 4 weeks from Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test-confirmed SARS-CoV2 infection. Exclusion criteria were: age < 18 or > 65 years, previous neurological or psychiatric diseases (i.e. major depressive disorder), neuroimaging assessed major vascular alterations, previous history of cognitive deficits, consumption of agents affecting the nervous system (e.g., antipsychotic, antidepressant or antiepileptic drugs). In addition, we excluded the patients who suffered from moderate-to-severe COVID-19 disease, defined as patients positive to SARS-CoV-2 with clinical and radiographic evidence of lower respiratory tract disease or hospitalised for COVID-19.

All subjects admitted to the post-COVID neurological outpatient clinic who reported a subjective cognitive impairment after the initial clinical evaluation, including medical history and comprehensive neurological examination, underwent Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test for cognitive deficits and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS).

All included patients underwent MRI imaging within 15 days from MoCA assessment. Imaging protocol included high resolution structural 3D T1-weighted images and 3D pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling (3D-pcASL), as well as standard clinical brain imaging including diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) to screen the presence of acute ischemic lesions. ASL scans and maps were visually inspected by two experienced radiologists (M.U. and M.A.C) to exclude the presence of artifacts. A total of two subjects were excluded for large motion artifacts and 24 post COVID-19 subjects were included in the final analysis.

As many as twenty-two age- and sex-matched healthy controls, who underwent MRI imaging—including ASL—in our University Hospital during a previous project before the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and had no history of cognitive impairment or of any other neurological disease, were retrospectively selected.

The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants released their informed consent for treatment of clinical data after all procedures had been fully explained, as for standard institutional procedure. This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee CEUR (Comitato Etico Unico Regionale, FVG, Italy).

Neuropsychological assessment

The MoCA was administered during the first visit by a trained neurologist using the validated Italian version30 and was further described by domain scores31 based on single item scores (orientation: spatial and temporal orientation; attention: digit span, letter A tapping, subtraction; executive: trail making, abstraction, word fluency; visuoconstructive: cube copying, clock drawing; language: naming, sentence repetition; memory: delayed word recall). The global MoCA test score was corrected for years of education (YoE; + 1 point if ≤ 12 YoE). Domain-scores were not adjusted for YoE. In addition, the MoCA score corrected according to correction for Italian population32 was also calculated.

The FSS, consisting of 9 sentences related to the interference of fatigue with daily activities and subjectively rating its severity on a 7-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”), was administered during the visit33.

MRI imaging and processing

All subjects were scanned on an Ingenia 3T MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) using a 32-channel head coil. High-resolution whole brain anatomic images were acquired using 3D T1-weighted (3DT1w) scan with TR = 8.4 ms, TE = 3.9 ms, flip angle = 8°, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 and 180 slices.

ASL-MRI was performed using the pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pcASL) with label duration = 1800 ms, post-labeling delay (PLD) = 2000 ms. 3D gradient and spin-echo (GraSE) pCASL scans with background suppression were obtained with TR/TE = 4.1 s/13 ms, FOV = 240 × 240 mm2, matrix size = 80 × 75, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 5 mm3, 20 slices, flip angle = 90°. Seven label/control image pairs were acquired as well as one calibration M0 image with no background suppression. All subjects were asked to rest and to keep their eyes closed during data acquisition. Post-COVID-19 and control subjects were acquired using exactly the same imaging protocol on the same MRI scanner.

The individual steps of ASL data processing and analysis were performed using FSL 6.0.5 (FMRIB, Oxford, United Kingdom) including Bayesian Inference for Arterial Spin Labelling MRI (BASIL)34. The head motion correction was carried out with MCFLIRT, non-brain tissue removal was performed with a brain extraction tool (BET). Spatial smoothing was also applied35. CBF maps were quantified from perfusion-weighted images (averaged pairwise subtracted control label images) by applying the general kinetic model36 according to the ASL white paper26 using voxel-wise calibration with the M0 image. To correct the partial volume effect spatially regularised technique was applied37. For each subject native space CBF maps were spatially normalised into the Montreal Neurological Institute—MNI152 standard-space (2-mm T1-weighted average structural template image).

Data analysis

Voxelwise analysis was performed to identify statistically significant differences in CBF maps between post-COVID-19 subjects and healthy controls by a non-parametric permutation testing38 (5000 permutations) using the FSL’s randomize tool. The resulting group difference maps were thresholded using a threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) method39 and a family-wise error (FWE) corrected p-values < 0.05 for multiple comparisons across space.

In addition, information on regional perfusion values was extracted by means of a region of interest (ROI) analysis for nine selected cortical regions including frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes, as well as cerebellum. Anatomic cortical ROIs were defined by the Harvard–Oxford cortical structural atlas in MNI standard space. The mean values of CBF within the masked anatomic ROIs were calculated for each subject. The regional mean CBF values of the brain regions were compared between the two groups.

The differences between groups in age, sex, years of education, and neuropsychological MoCA Score were also tested.

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean and standard deviations (mean ± SD), those with a skewed distribution as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) indicating the first and third quartiles, and categorical variables as counts and percentages (%). Differences between groups were tested with Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann–Whitney U-test for skewed variables, and Pearson’s Chi square for categorical variables. Level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 24 post-COVID-19 patients with subjective cognitive impairment included in the study are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of post-COVID-19 patents.

| (n = 24) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.0 ± 14.5 |

| Sex (M/F) | 9M/15F |

| Education (years) | 14.3 ± 3.2 |

| Δ Covid-19 symptom—Post-Covid-19 assessment (days) | 179.5 (128.5–210.5) |

| Δ Covid-19 symptom—MRI assessment (days) | 10.8 ± 2.1 |

| Pre-existing comorbidities and risk factors | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1 (4.2%) |

| Hypertension | 6 (25.0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (8.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (12.5%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (8.3%) |

| Obesity | 4 (16.6%) |

| Smoke | 3 (12.5%) |

| Autoimmune disease | 1 (4.2%) |

| Clinical features during COVID-19 acute phase | |

| Fever | 18 (75.0%) |

| Upper respiratory airways involvement | 16 (66.6%) |

| Asthenia | 13 (54.1%) |

| Myalgia/arthralgia | 13 (54.1%) |

| Dyspnea | 10 (41.7%) |

| Headache | 9 (37.5%) |

| Hyposmia | 9 (37.5%) |

| Hypo/dysgeusia | 6 (25.0%) |

| Diarrhea/gastrointestinal distress | 3 (12.5%) |

| Palpitations/tachycardia | 2 (8.3%) |

| Post-COVID-19 manifestations | |

| Number of symptoms per patient | 3.5 (2–5) |

| Asthenia | 15 (62.5%) |

| Dyspnea | 10 (41.7%) |

| Hyposmia | 8 (33.3%) |

| Headache | 6 (25.0%) |

| Myalgia/arthralgia | 5 (20.8%) |

| Dizziness/gait instability | 4 (16.7%) |

| Palpitations/tachycardia | 4 (16.7%) |

| Hypo/dysgeusia | 3 (12.5%) |

| Diarrhea/gastrointestinal distress | 1 (4.2%) |

There were no significant differences in age, sex and education between the post-COVID-19 (n = 24) and healthy control (n = 22) groups (53.0 ± 14.5 years for patients vs 54.8 ± 9.1 years for healthy subjects, p = 0.556; 62.5% of women for patients vs 59.1% of women for healthy subjects; p-value = 0.813; 14.3 ± 3.2 years of education for patients vs 14.9 ± 3.0 years of education for healthy subjects, p = 0.536).

Among the 24 included post-COVID-19 patients the reported pre-existing comorbidities and risk factors were hypertension (25.0%), obesity (16.6%), smoke (12.5%), dyslipidemia (12.5%), atrial fibrillation (8.3%), diabetes mellitus (8.3%), ischemic heart disease (4.2%) and autoimmune disease (4.2%). The prevalence of comorbidities and risk factors in the control group were hypertension (22.3%), obesity (13.6%), smoke (18.2%), dyslipidemia (13.6%), diabetes mellitus (4.5%), ischemic heart disease (4.5%) and autoimmune disease (9.0%).

During the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, main symptoms of included post-COVID-19 subjects were fever (75.0%), upper respiratory airways involvement (66.6%), asthenia (54.1%), myalgia/arthralgia (54.1%), dyspnea (41.7%), headache (37.5%), hyposmia (37.5%), hypo/dysgeusia (25.0%), diarrhea/gastrointestinal distress (12.5%), palpitations/tachycardia (8.3%). None of the included patients were hospitalised or underwent oxygen therapy during the acute phase.

Beside cognitive complaint, the post-COVID-19 manifestations reported during examination were asthenia (62.5%), persistent dyspnea (41.7%), hyposmia (33.3%), headache (25.0%), myalgia/arthralgia (20.8%), dizziness/gait instability (16.7%), palpitations/tachycardia (16.7%), hypo/dysgeusia (12.5%), diarrhea/gastrointestinal distress (4.2%).

All participants underwent standard clinical brain MRI assessment and none of them presented lesions in DWI or particular signs of atrophy or structural changes.

The median duration between post-COVID clinical evaluation, including the cognitive assessment, and the first infectious symptoms was 5.9 (4.2–6.9) months. The magnetic resonance imaging was performed within 15 days from cognitive assessment (10.8 ± 2.1 days).

The results of cognitive assessment are summarised in Table 2. The median MoCA was 26 (24–27). The median of MoCA score corrected according to correction for Italian population32 was 23.5 (22.4–24.9). None of the patients had a total corrected MoCA score below the cut-off for pathological impairment (< 18), according to the normative data for the Italian population32. However, corrected and uncorrected total MoCA scores was significantly lower in post-COVID-19 group compered to HC (p < 0.001). In particular, post-COVID-19 group presented significantly lower sub-domain MoCA scores for executive, attention, language and especially, memory functions, while no differences in orientation and visuoconstructive functions were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of cognitive assessment of post-COVID-19 patents.

| post-COVID-19 | Healthy controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 24) | (n = 22) | p-value | |

| MoCA | 26 (24–27) | 29 (28–30) | < 0.001* |

| MoCA domain scores | |||

| Orientation (max 6) | 6 (6–6) | 6 (6–6) | 0.607 |

| Attention (max 6) | 5.5 (4.5–6) | 6 (6–6) | 0.006* |

| Language (max 6) | 5 (5–6) | 6 (5–6) | 0.011* |

| Visuospatial function (max 4) | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | 0.711 |

| Memory (max 5) | 3 (2–4) | 5 (4–5) | < 0.001* |

| Executive function (max 4) | 3.5 (3–4) | 4 (4–4) | 0.017* |

| MoCA corrected according Aiello et al.32 | 23.5 (22.4–24.9) | 26.9 (26.3–27.2) | < 0.001* |

| Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | 5.32 ± 1.26 | – | – |

*Statistically significant differences.

The average FSS score in post-COVID-19 group was 5.32 ± 1.26 and 45.8% presented a score higher than the FSS cut-off.

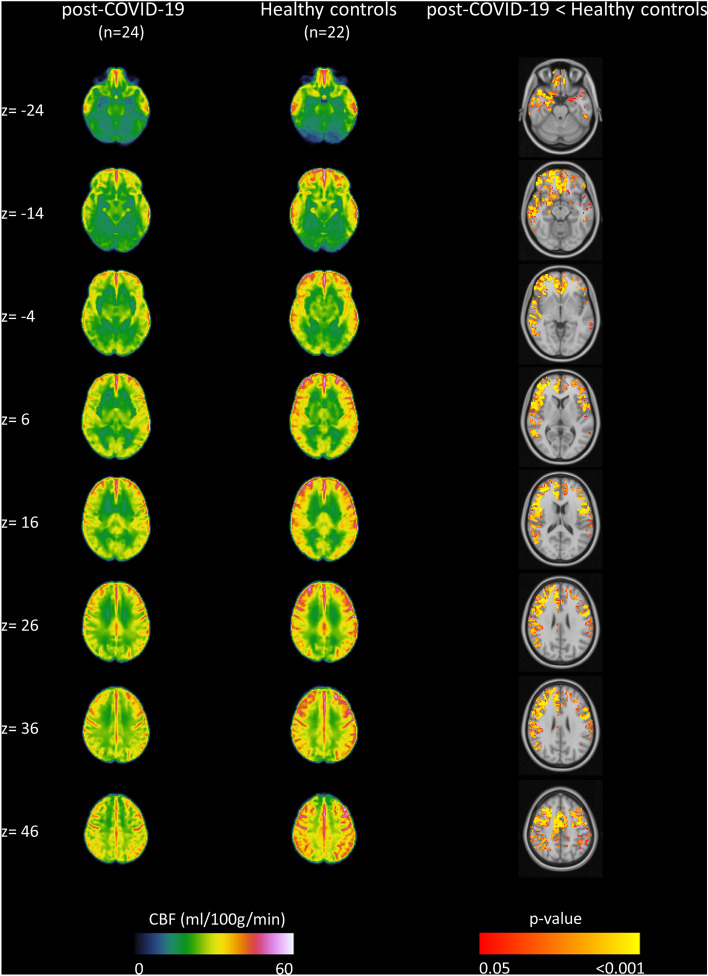

In Fig. 1 are shown the averaged CBF maps calculated for the post-COVID-19 group and healthy subjects, as well as the regions that showed a significant hypoperfusion in the post-COVID-19 group compared to the healthy controls as identified by a non-parametric permutation testing (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected with TFCE). The summary of cluster-level statistics for significant hypoperfused clusters is reported in Table 3. A lower CBF in the post-COVID-19 group compared to healthy subjects was detected in the right and left frontal, parietal and temporal cortex. The hypoperfusion areas identified in the right hemisphere regions were more extensive. No regions with a significantly higher perfusion in post-COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls were detected.

Figure 1.

Result of group analysis of MRI-ASL data. The group averaged cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps (ml/100 g/min) calculated for the post-COVID-19 group (left column) and healthy subjects (middle column). Right column depicts regions that show significant hypoperfusion in post-COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls (non-parametric permutation test, p < 0.05, FWE-corrected with TFCE). No regions with a significantly higher perfusion in post-COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls were detected. Images are reported in the 2-mm MNI152 standard space and in radiological convention.

Table 3.

The summary of cluster-level statistics of the identified hypoperfused regions in post-COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls (anatomical regions, cluster sizes, MNI coordinates of peak locations, as well as t-score and p-values).

| Area | Side | Voxels | MNI coordinate | T score | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Frontal lobe | R | 13,296 | 12 | 40 | − 8 | 6.69 | 0.001 |

| Frontal lobe | L | 7266 | − 52 | 0 | 20 | 7.47 | 0.001 |

| Parietal lobe | R | 6525 | 58 | − 34 | 22 | 7.59 | 0.001 |

| Parietal lobe | L | 1731 | − 44 | − 44 | 50 | 6.92 | 0.004 |

| Temporal lobe | R | 5206 | 62 | − 22 | − 8 | 6.02 | 0.001 |

| Temporal lobe | L | 978 | − 52 | − 34 | − 20 | 7.23 | 0.002 |

The global mean of CBF in gray matter was lower in post-COVID group compared to controls (37.7 (33.3–44.8) vs 44.6 (40.8–48.7), p-value = 0.011). Table 4 reports the results of the ROI analysis of the selected anatomical regions. The mean CBF was significantly lower in left frontal, right frontal, right parietal, left temporal and right temporal lobes in post COVID-19 compared to healthy controls. No significant differences in regional mean CBF were observed for left parietal lobe, left and right occipital lobes, as well as for cerebellum. There was no significant correlation between the MoCA scores and CBF values within the post-COVID-19 group.

Table 4.

Median (IQR) of regional mean CBF values (ml/100 g/min) of post-COVID-19 subjects and healthy controls at the various ROIs and comparison between two groups.

| Area | Side | CBF | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-COVID-19 | Healthy controls | |||

| Frontal lobe | R | 46.3 (40.6–55.3) | 52.2 (49.5–61.9) | 0.003* |

| Frontal lobe | L | 47.7 (41.3–57.0) | 53.4 (50.4–62.2) | 0.021* |

| Parietal lobe | R | 45.3 (39.4–53.4) | 50.6 (49.3–58.7) | 0.036* |

| Parietal lobe | L | 47.1 (40.7–57.6) | 52.6 (50.1–57.9) | 0.078 |

| Temporal lobe | R | 34.7 (31.4–42.7) | 41.7 (38.1–48.0) | 0.005* |

| Temporal lobe | L | 36.3 (30.8–45.6) | 42.2 (38.8–50.7) | 0.033* |

| Occipital lobe | R | 36.9 (31.3–44.4) | 38.0 (34.5–49.0) | 0.220 |

| Occipital lobe | L | 39.0 (33.2–45.8) | 41.0 (38.8–46.5) | 0.392 |

| Cerebellum | – | 25.1 (21.3–34.4) | 29.6 (26.5–35.2) | 0.101 |

*Statistically significant differences.

Discussion

The present voxel-based MRI-ASL study identified a significant hypoperfusion in frontal, temporal, and parietal cortex in post-COVID-19 subjects with persistent cognitive impairment 2–10 months after the initial symptoms. The identified hypoperfusion areas were more predominant in frontal regions and more extensive in the right hemisphere. These hypoperfusion clusters were highly discriminant to distinguish cognitively impaired post-COVID-19 patients and healthy subjects.

The identified hypoperfusion areas, in particular frontal lobes, could justify the primarily reduced cognitive performance in executive, attention, language and memory observed in post-COVID-19 patients. The cognitive complaints observed in our sample were in accordance with the common clinical picture reported in post-COVID-19 studies7,14,40. The same was observed in studies which encompassed non-hospitalised patients and those who did not suffer from severe COVID-19 infection40,41. In particular, deficits in memory40–42, attention40–42, language and executive functions40,41 domains have been observed in post-COVID-19 subjects. In general, such cognitive deficits were characterised by functional or structural impairment of the frontal and prefrontal lobes43,44. Indeed, frontal lobes represent key hubs for working memory, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, planning, and problem solving43,44.

These cognitive deficits have also been linked with hypometabolism pattern revealed by FDG-PET imaging in several studies performed on acute and post-COVID-19 patients that presented cognitive complaints12,14,16,17. Frontal and less extensive temporoparietal cortical hypometabolism was observed in seven acute COVID-19 patients with progressive normalization of cerebral metabolism during follow-up at 1 and 6 months, but with persisting prefrontal hypometabolism17. FDG-PET pattern characterised by prevailing frontal lobe hypometabolism, which may reflect an immune mechanism, was detected in four patients with COVID-19-related encephalopathy16. Predominant frontoparietal cortical hypometabolism was observed in 10 out of 15 patients, included subacute COVID-19 patients with decline in frontoparietal cognitive functions14. The follow-up FDG-PET performed on eight patients at 6 months after COVID-19 reveled a reduction of the initial frontoparietal and, to a lesser extent, temporal hypometabolism, although the alterations were still measurable12. The anatomical MRI performed in aforementioned studies has not detected specific abnormalities for most of the subjects7,14,16,17. However, the MRI study, which investigated longitudinal alterations before and after COVID-19, has detected significant effects, including a greater reduction in gray matter thickness and tissue contrast in the orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus, greater changes in markers of tissue damage in regions that are functionally connected to the primary olfactory cortex and a greater reduction in global brain size in the SARS-CoV-2 patients/subjects compared to controls45. The same study reported a greater cognitive decline between the two time points in the participants who were infected with SARS-CoV-2. A recent ASL study reported a significantly decreased CBF in the thalamus, orbitofrontal cortex and regions of the basal ganglia in subjects who previously self-isolated at home due to COVID-19 when compared against controls who experienced flu-like symptoms but tested negative for COVID-1945.

The inflammatory parainfectious process targeting specially the frontal lobes and/or frontal networks was suggested as the underlying cause of the reported clinical, neurophysiological and neuroimaging findings in COVID-19 patients46. Post-infectious inflammation, production of anti-neuronal autoantibodies, vasculitis, cytokine-related hyperinflammation and the cerebral complications of hypoxia and coagulopathy are possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms induced by the SARS-CoV-2 infection14,47. Successful therapy with immunoglobulin was reported in two cases with status epilepticus in COVID-19 infection suggesting strong autoimmune mechanism48. The aforementioned pathophysiological mechanisms may be a valid explanation for cortical and blood brain barrier dysfunction, leading to cerebral hypopefusion, hypometabolism, and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 subjects. The novelty of this study is that we identified a hypoperfusion areas (frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes), similar to the previously reported FDG-PET hypometabolism pattern, in twenty-four post-COVID-19 subjects with persistent cognitive impairment by non-invasive ASL-MRI technique and analysis, without any radiological contrast agents and radiopharmaceuticals.

Our findings showed that ASL imaging and analysis were able to reveal cerebral hypoperfusion pattern in post-COVID-19 subjects with cognitive deficit. As a non-invasive technique, MRI-ASL could be a useful tool for the follow-up of such patients.

Our study is a single center study on a moderate study sample. The included patients were screened with MoCA test which do not provide comprehensive information about overall cognitive performance. ASL acquisition and subsequently the results of analysis can potentially be susceptible to the different labeling efficiency, which may vary over arteries, scans, and subjects. Variable time points from COVID-19 infection, i.e., range 2–10 months form COVID-19 symptoms onset, median (IQR) 6.0 (4.3–7.0 months), may pose another limitation. However, all patients reported cognitive complaints at the moment of the acquisition. The included patients had a paucisymptomatic acute COVID-19 which did not require hospitalisation or ventilatory support.

Conclusions

In this study we identified a significative alteration of cerebral perfusion pattern in post-COVID-19 subjects who reported cognitive deficit by using a non-invasive ASL-MRI perfusion imaging technique and analysis. Particularly, significant hypoperfusion was observed predominantly in bilateral frontal, as well as in temporal, and parietal areas compared to healthy subjects, supporting the hypothesis of a large network dysfunction. The non-invasive nature of the ASL-MRI method may play an important role in the monitoring and prognosis of post-COVID-19 subjects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Matteo di Franza for editorial and proofreading assistance.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: M.A., K.I., G.F. and P.M.; methodology M.A, K.I and A.A.; data collection: MA, GF, M.M., M.U., M.A.C.; processing and analysis of imaging datasets: M.A., KI. and A.M.; data analysis: M.A., KI. and A.B.S..; analysis and interpretation of results: M.A., K.I., G.F., P.M., draft manuscript preparation: M. A. and K.I.; all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

Anonymized data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nalbandian A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ceban F, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groff D, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2128568. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tenforde MW, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecchetti G, et al. Cognitive, EEG, and MRI features of COVID-19 survivors: A 10-month study. J. Neurol. 2022;2022:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11047-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buoite-Stella A, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID patients with and witfhout neurological symptoms: A prospective multidomain observational study. J. Neurol. 2022;269:587–596. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michelutti M, et al. Sex-dependent characteristics of Neuro-Long-COVID: Data from a dedicated neurology ambulatory service. J. Neurol Sci. 2022;441:120355. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Borst B, et al. Comprehensive health assessment 3 months after recovery from acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:e1089–e1098. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazza MG, et al. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: Effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three-month follow-up. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021;94:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blazhenets G, et al. Slow but evident recovery from neocortical dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a series of chronic COVID-19 patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2021;62:910–915. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Brutto OH, et al. Cognitive decline among individuals with history of mild symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: A longitudinal prospective study nested to a population cohort. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021;28:3245–3253. doi: 10.1111/ene.14775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosp JA, et al. Cognitive impairment and altered cerebral glucose metabolism in the subacute stage of COVID-19. Brain. 2021;144:1263–1276. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hugon J, et al. Cognitive decline and brainstem hypometabolism in long COVID: A case series. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2513. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delorme C, et al. COVID-19-related encephalopathy: A case series with brain FDG-positron-emission tomography/computed tomography findings. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020;27:2651–2657. doi: 10.1111/ene.14478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kas A, et al. The cerebral network of COVID-19-related encephalopathy: A longitudinal voxel-based 18F-FDG-PET study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2021;48:2543–2557. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudroff T, Workman CD, Ponto LLB. 18F-FDG-PET imaging for post-COVID-19 brain and skeletal muscle alterations. Viruses. 2021;13:2283. doi: 10.3390/v13112283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guedj E, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2021;48:2823–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buxton RB, Uludağ K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexopoulos P, et al. Perfusion abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia in Alzheimer’s disease measured by pulsed arterial spin labeling MRI. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012;262:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melzer TR, et al. Arterial spin labelling reveals an abnormal cerebral perfusion pattern in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2011;134:845–855. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.BoscoloGalazzo I, et al. Patient-specific detection of cerebral blood flow alterations as assessed by arterial spin labeling in drug-resistant epileptic patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storti SF, et al. Combining ESI, ASL and PET for quantitative assessment of drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2014;102(Pt 1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinoto A, et al. ASL MRI and 18F-FDG-PET in autoimmune limbic encephalitis: Clues from two paradigmatic cases. Neurol. Sci. 2021;42:3423–3425. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsop DC, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015;73:102–116. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Plas MCE, Teeuwisse WM, Schmid S, Chappell M, van Osch MJP. High temporal resolution arterial spin labeling MRI with whole-brain coverage by combining time-encoding with Look-Locker and simultaneous multi-slice imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019;81:3734–3744. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marterstock DC, et al. Pulsed arterial spin labeling and segmented brain volumetry in the diagnostic evaluation of frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Tomography. 2022;8:229–244. doi: 10.3390/tomography8010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim WSH, et al. MRI Assessment of cerebral blood flow in nonhospitalized adults who self-isolated due to COVID-19. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jmri.28555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirrotta F, et al. Italian validation of montreal cognitive assessment. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2015;31:131–137. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasreddine ZS, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiello EN, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Updated norms and psychometric insights into adaptive testing from healthy individuals in Northern Italy. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022;34:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siciliano M, et al. Fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: Italian validation of the Parkinson Fatigue Scale and the Fatigue Severity Scale using a Rasch analysis approach. Parkinson. Relat. Disord. 2019;65:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chappell MA, Groves AR, Whitcher B, Woolrich MW. Variational Bayesian inference for a nonlinear forward model. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009;57:223–236. doi: 10.1109/TSP.2008.2005752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groves AR, Chappell MA, Woolrich MW. Combined spatial and non-spatial prior for inference on MRI time-series. Neuroimage. 2009;45:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buxton RB, et al. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn. Reson. Med. 1998;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chappell MA, et al. Partial volume correction of multiple inversion time arterial spin labeling MRI data. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;65:1173–1183. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichols TE, Holmes AP. Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: A primer with examples. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;15:1–25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker JH, et al. Assessment of cognitive function in patients after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2130645. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voruz P, et al. Long COVID neuropsychological deficits after severe, moderate, or mild infection. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2022;6:9. doi: 10.3390/ctn6020009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao S, et al. Rapid vigilance and episodic memory decrements in COVID-19 survivors. Brain Commun. 2022;4:fcab295. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henri-Bhargava A, Stuss DT, Freedman M. Clinical assessment of prefrontal lobe functions. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2018;24:704. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones DT, Graff-Radford J. Executive dysfunction and the prefrontal cortex. Continuum (Minneap. Minn.) 2021;27:1586–1601. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Douaud G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;604:697–707. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toniolo S, et al. Dementia and COVID-19, a bidirectional liaison: Risk factors, biomarkers, and optimal health care. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:883–898. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson RW, et al. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: Clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020;143:3104–3120. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manganotti P, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin response in new-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) COVID-19 adult patients. J. Neurol. 2021;268:3569–3573. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10468-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.