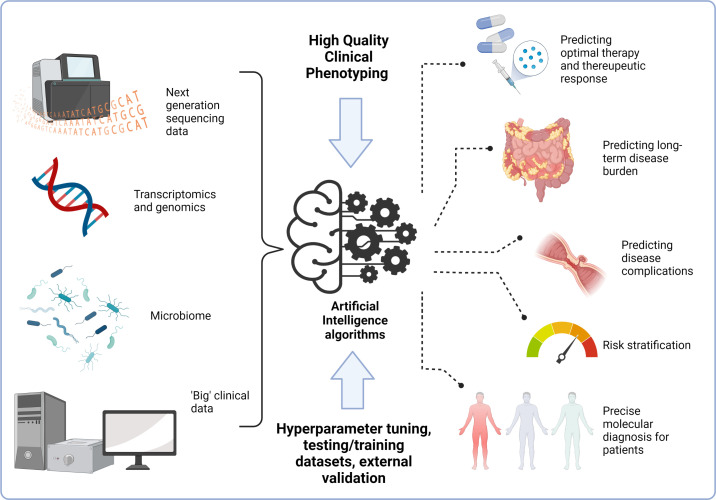

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare provides an opportunity to improve clinical care and patient outcomes. Gastroenterology may be seen as a leader in the application of AI, through automatic image recognition and interpretation in endoscopy, and analysis of images gathered through video capsule endoscopy.1 Despite this, the clinical translation of AI into routine practice has lagged behind its application in research settings. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) presents specific clinical challenges for which AI may have solutions, including prediction of therapeutic response, novel subgroup classification, precise molecular diagnosis, complication risk stratification and endoscopic image analysis for scoring of severity of mucosal inflammation in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.2 We are also moving to an era of big data in IBD research, with consortia collecting and collating large cohorts of patients with available genomic, and other multiomic, data.3 4 This resource presents an unrivalled opportunity to alter the landscape of disease prediction and classification in IBD, and usher in routine personalisation of diagnosis and treatment (figure 1). A key part of reliable, reproducible and applicable use of AI for patients, is the quality of the clinical phenotyping. Lack of in-depth clinical data, systemic bias in data entry, lack of longitudinal outcomes and missing data all pose huge challenges to application of AI, with algorithms reliant on high-quality data input to give high-quality output.5 While this constitutes a challenge, it also creates an opportunity to develop robust systems to gather prospective and retrospective data, in structured ways and to use routinely collected data for alternative purposes.

Figure 1.

Potential applications of artificial intelligence and ‘big data’ to personalise management in inflammatory bowel disease. Created with BioRender.com.

Within this opinion article, we focus on the use of AI to predict outcomes, response to therapy, complications and novel disease subgroups, from molecular and ‘big’ clinical data. We aim to highlight the current issues associated with limited clinical phenotyping of patients, reinforce the importance of precise longitudinal clinical data collection, with specific examples of translational opportunities for big data in IBD. We propose potential mechanisms for optimisation of future clinical application.

Accurate data in AI: what are the issues?

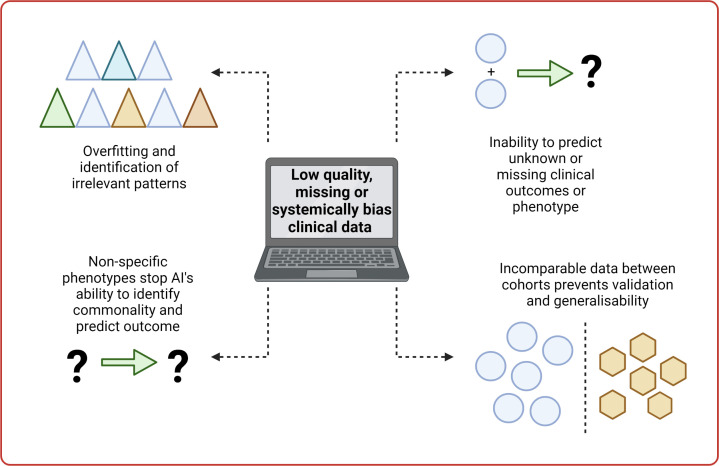

Within AI and machine learning the term ‘garbage in, garbage out’ holds true. There is an absolute need for high-quality data to get high-quality models to benefit patients (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Issues and limitation related to low-quality data and artificial intelligence (AI). Created with BioRender.com.

Algorithms look for patterns

At their simplest, AI algorithms look for patterns in data. This can be performed by a number of mathematical techniques and tools, where AI is searching for similarity (or dissimilarity) in data to classify individuals into predefined categories (supervised) or discover novel groupings (unsupervised).5 The patterns for which the algorithms are searching can be real and generalisable or can be specific to datasets, and therefore, not useful. The patterns can also be inadvertently introduced through systemic bias or missing data. The concept of AI overfitting to datasets is a problem—namely the algorithm finds patterns that are not relevant to the outcomes of interest. High-quality data input, in a structured fashion, can help to minimise discovery of irrelevant patterns.

Al can only predict outcomes it knows about

Defining the clinical outcomes that are most useful to patients and clinicians is important in focusing the use of predictive AI in IBD.6 Clinical and multiomic data have huge potential to provide prediction tools for complications, response to therapeutics and for specific molecular disease subclassification. However, the algorithm can only be trained to discover outcomes it knows about. The presence of precise clinical outcomes in these datasets is vital to be able to train and test AI to predict clinically useful outcomes.

The better the phenotype, the better the predictive ability

The accuracy of the phenotype is all important. Clinical data must look beyond simple outcomes such as disease subtype (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) to useful, longitudinal phenotyping of patients to accurately refine prediction models. High-quality, specific and structured phenotypic data provide the best opportunity for algorithms to produce predictive tools to help patients. Inherently, phenotypic data that is of poor quality, overly broad, incomplete or containing systemic bias limits accurate clinical application for AI.7

External validation and application of algorithms

When creating prediction models, datasets must be split into training and testing cohorts, to avoid circularity. Beyond this initial stage, the clinical translation of AI to benefit patients depends on validation on external patient cohorts. This ensures generalisability of algorithms. Importantly, to use AI in clinical settings the same structured, high-quality, data that were used to train the models must be collected and collated for all patients.7

How can we improve clinical application of AI in IBD?

There is a need to maximise the potential of AI to personalise diagnosis and management of IBD. There are several defined avenues which need to be considered for optimisation of data collection and study management that will improve outcomes and ensure best practice is followed in application of AI and delivery of precision medicine.8

Stringent definitions for clinical variables and outcomes

There is high variability in recording and defining disease, including the tools used, the data collected and the local guidelines followed.9 Standardising and defining basic clinical parameters including biochemical, endoscopic and histological data, alongside long-term measures of disease outcomes, would allow for reduction in the introduction of systemic bias and better utilisation of retrospective clinical data. Strict definitions of treatment response, complications, extraintestinal manifestations and side effects are vital for successful application of machine learning techniques and accurate prediction models.

Automated data collection

Electronic care records offer huge potential as a repository of long-term clinical data and by using this data set there are significant research opportunities to improve patient outcomes. Accurate, automated systems for collection, cleaning and collation of these data presents an opportunity for standardising retrospective clinical phenotyping, including utilising the potential of natural language processing. The Gut Reaction collaboration is now starting to harness the power of ‘big’ clinical data and research opportunities of this repository may be significant.10 It is vital that high-quality data do not come at the cost of being overly burdensome on clinicians, and in some instances data collection directly from patients may prove highly relevant for outcomes not easily captured through medical records.

Technical effects of experiments

An appreciation of the technical effects of sequencing experiments, alongside knowledge that there is a need to optimise AI algorithms through hyperparameter tuning and correct selection of AI model will promote best practice. Involving scientific expertise at an early stage in planning experiments and studies will avoid the potential for introducing systemic bias to AI methodologies, including batch effects in techniques such as transcriptomics, microbiome and epigenetic data.

Novel longitudinal disease burden tools

To date, the heterogeneity of IBD has made defining long-term disease burden challenging.11 Prediction studies have used proxy measures of disease burden such as step-up in therapy, use of biological therapy or need for surgery, however, these fail to account for the complexity and variation in disease burden that can affect an individual patient.12 13 Novel methods are needed to encapsulate longitudinal disease burden into numerical scores, as a tool for AI prediction and stratification of patients.

Standardisation of datasets for studies

There is the potential for cohorts to achieve a standardised clinical dataset to facilitate application of AI models. This strategy is important for external validation, which is key to ensure models are generalisable and clinically useful. Standardisation of outcomes and international harmonisation of outcome measures remains challenging, at least in part due to different standards of care and availability of investigations or therapies in different healthcare systems. Recent work from the European Crohn’s and Colitis organisation (ECCO) has provided an outstanding core outcome set for real-world studies in IBD, based on international consensus.14 This is an excellent blueprint for the key data to be collated in AI studies in IBD. We propose a more limited dataset directly relevant to AI (table 1). This is not intended to replace the more comprehensive ECCO guidance but includes collectable, longitudinal, clinical data for incorporation into AI algorithms. We intend this to act as a guide for a minimal dataset to ensure translatability between studies and cross-validation of models.

Table 1.

Suggested first-tier clinical dataset to be collected for prospective artificial intelligence inception cohorts and retrospective studies

| Overall clinical data | Disease location and extent at diagnosis | Blood and calprotectin results | Medications | Complications | Surgery | Extraintestinal manifestations |

| Suggested inclusions | Montreal (or Paris) classification of disease location and extent | Haemoglobin, C reactive protein, albumin, faecal calprotectin | 5-ASA/topical treatment, steroid courses Immunomodulator First line monoclonal or small molecule ‘Advanced therapies’ |

Fistulating disease Stricturing disease |

Intestinal resections, perianal procedures | Liver disease, skin manifestations, joint disease, eye disease |

| Timing of data collection | At diagnosis | Duration of disease-longitudinal assessment | Yearly reviews | Yearly reviews | Yearly reviews | Yearly reviews |

| Important additions | Consider inclusion of disease extent assessed through follow-up endoscopy | Including drug levels and anti-drug antibodies where available | Include drug failures and adverse reactions. | Time from diagnosis to occurrence | Time from diagnosis to occurrence | Include additional autoimmune disease and occurrence of malignancy |

This dataset specifically focuses on data that can be easily coded in a reproducible, numerical, way and is easily collectable to avoid issues faced with missing data.

5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylate.

Current ‘big data’ opportunities

Next-generation sequencing data are plentiful in IBD research. International initiatives, alongside national projects such as the UK Biobank and IBD Bioresource equate to tens of thousands of whole exomes from patients with IBD that have been sequenced, resulting in stable data not subject to batch effects from sequencing.3 4 15 Recent high-profile publications have used vast quantities of data to identify risk loci for Crohn’s disease and are improving the understanding of molecular aetiology at a population level.16 Microbiome and transcriptomic data are also widely collected but are subject to batch effects which make pooling data more complex.17 18

We believe translating these huge resources, and the potential of these data to patient benefit can be achieved through AI, but clinical prediction requires high-quality and precise clinical data.

Potential strategies for standardisation

Increasing the awareness of high-quality data for AI is important. Strategies to address issues raised within this article and progress towards clinical translation are equally imperative. We have proposed several potential tools for optimisation and standardisation including definition of clinical phenotypes, longitudinal disease burden scores, automated data collection and minimal datasets. It is important to acknowledge ethical, financial and legal frameworks that must be developed and adhered to, including maintaining patient confidentiality and maintaining cost-effectiveness. It is also important to acknowledge standardisation of clinical decisions related to AI and support systems to help medical professionals with AI application. Application of AI should currently be considered as an adjunct to clinical judgement, rather than a replacement of the clinician. Developing a future evidence base for routine clinical use of AI must consider observational, trial and retrospective data collection.

Future collaborative initiatives must look to produce a framework for standardised collection, processing and quality control of clinical phenotyping data, incorporating longitudinal measures and ensuring inclusivity of patients from diverse backgrounds to ensure tools are applicable to all patients. Furthermore, stringent replication of findings on external cohorts must be routinely performed through data sharing and research collaboration. Finally, moving AI prediction tools towards clinical application must be seen as a priority, with the potential to guide the personalisation of therapy, prediction of outcomes and risk stratification for all patients with IBD.

Footnotes

Twitter: @James_Ashton, @johanne_brooks, @samiHoque2, @DrNickKennedy, @anjan_dhar6

Contributors: JA conceived the article with SS and JB-W. JA wrote the article with help from all authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: JA is funded by an NIHR clinical lectureship.

Competing interests: JB-W holds research grants from AbbVie, and has received speaker fees from Dr Falk Pharma. JA no COI to declare. AD Advisory and consultancy for Pfizer UK, Tillotts Pharma UK, Dr Falk Pharma, Pharmacosmos, Takeda UK, Honoraria and Speaker Fees from Dr Falk Pharma, Pfizer, Janssen, Tillotts Pharma, Pharmacosmos, Takeda UK. PBA received research grants from Pfizer and speaker fees from Takaeda, AbbVie, GSK, Janssen, MSD and Tillotts. TCT no COI to declare. SH no COI to declare. SS holds research grants from Biogen, Takeda, AbbVie, TillottsPharma, Ferring and Biohit; served on the advisory boards of Takeda, AbbVie, Merck, Ferring, Pharmacocosmos, Warner Chilcott, Janssen, Falk Pharma, Biohit, TriGenix, Celgene and Tillots Pharma; and has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Biogen, AbbVie, Janssen, Merck, Warner Chilcott and Falk Pharma. NAK has served as a speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Allergan, BMS, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, Mylan, Pharmacosmos, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda and Tillotts. He is the director of a company that handles central reading of endoscopy. His department has received research funding from AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Celtrion, Galapagos, MSD, Napp, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche and Takeda.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2023. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Le Berre C, Sandborn WJ, Aridhi S, et al. Application of artificial intelligence to gastroenterology and hepatology. Gastroenterology 2020;158:76–94. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks-Warburton J, Ashton J, Dhar A, et al. Artificial intelligence and inflammatory bowel disease: practicalities and future prospects. Frontline Gastroenterol 2022;13:325-331. 10.1136/flgastro-2021-102003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. Uk Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001779. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parkes M, IBD BioResource Investigators . IBD BioResource: an open-access platform of 25 000 patients to accelerate research in Crohn's and Colitis. Gut 2019;68:1537–40. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashton JJ, Young A, Johnson MJ, et al. Using machine learning to impact on long-term clinical care: principles, challenges, and practicalities. Pediatr Res 2022;50:1–10. 10.1038/s41390-022-02194-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hart AL, Lomer M, Verjee A, et al. What are the top 10 research questions in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease? A priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. ECCOJC 2017;11:204–11. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stafford IS, Gosink MM, Mossotto E, et al. A systematic review of artificial intelligence and machine learning applications to inflammatory bowel disease, with practical guidelines for interpretation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2022;28:1573–83. 10.1093/ibd/izac115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noor NM, Sousa P, Paul S, et al. Early diagnosis, early stratification, and early intervention to deliver precision medicine in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2022;28:1254–64. 10.1093/ibd/izab228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Egberg MD, Gulati AS, Gellad ZF, et al. Improving quality in the care of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:1660–9. 10.1093/ibd/izy030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gut Reaction Health Data Research Hub for IBD, Crohn’s & Colitis data. Available: https://gut-reaction.org/ [Accessed 31 Aug 2022].

- 11. Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, et al. Long-Term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2002;8:244–50. 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biasci D, Lee JC, Noor NM, et al. A blood-based prognostic biomarker in IBD. Gut 2019;68:1386–95. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ricciuto A, Rauter I, McGovern DPB, et al. Precision medicine in inflammatory bowel diseases: challenges and considerations for the path forward. Gastroenterology 2022;162:1815–21. 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanzel J, Bossuyt P, Pittet V, et al. Development of a Core Outcome Set for Real-world Data in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] Position Paper. J Crohns Colitis 2022;389. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen G-B, Lee SH, Montgomery GW, et al. Performance of risk prediction for inflammatory bowel disease based on genotyping platform and genomic risk score method. BMC Med Genet 2017;18:94. 10.1186/s12881-017-0451-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sazonovs A, Stevens CR, Venkataraman GR, et al. Large-Scale sequencing identifies multiple genes and rare variants associated with Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 2022;54:1275–83. 10.1038/s41588-022-01156-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashton JJ, Beattie RM, Ennis S, et al. Analysis and interpretation of the human microbiome. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:1713–22. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haberman Y, Tickle TL, Dexheimer PJ, et al. Corrigendum. pediatric Crohn disease patients exhibit specific ileal transcriptome and microbiome signature. J Clin Invest 2015;125:1363. 10.1172/JCI79657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]