Abstract

Background

Benralizumab is highly effective in many, but not all, patients with severe asthma. Baseline characteristics alone are insufficient to predict an individual's probability of long-term benralizumab response. The objectives of the present study were to: 1) study whether parameters at 3 months, in addition to baseline characteristics, contribute to the prediction of benralizumab response at 1 year; and 2) develop an easy-to-use prediction tool to assess an individual's probability of long-term response.

Methods

We assessed the effect of benralizumab treatment in 192 patients from the Dutch severe asthma registry (RAPSODI). To investigate predictors of long-term benralizumab response (≥50% reduction in maintenance oral corticosteroid (OCS) dose or annual exacerbation frequency) we used logistic regression, including baseline characteristics and 3-month Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ-6) score and maintenance OCS dose.

Results

Benralizumab treatment significantly improved several clinical outcomes, and 144 (75%) patients were classified as long-term responders. Response prediction improved significantly when 3-month outcomes were added to a predictive model with baseline characteristics only (area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) 0.85 versus 0.72, p=0.001). Based on this model, a prediction tool using sex, prior biologic use, baseline blood eosinophils, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, and at 3 months OCS dose and ACQ-6 was developed which classified patients into three categories with increasing probability of long-term response (95% CI): 25% (3–65%), 67% (57–77%) and 97% (91–99%), respectively.

Conclusion

In addition to baseline characteristics, treatment outcomes at 3 months contribute to the prediction of benralizumab response at 1 year in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Prediction tools as proposed in this study may help physicians optimise the use of costly biologics.

Short abstract

Baseline characteristics and OCS dose and ACQ score at 3 months help predict long-term clinical response to benralizumab. Clinical tools, such as proposed in this study, could help clinicians predict future response to benralizumab. https://bit.ly/3XS9nDd

Introduction

Severe eosinophilic asthma is associated with impaired quality of life, uncontrolled asthma symptoms [1–4] and severe exacerbations that, until recently, could only be controlled by recurrent bursts or daily use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) putting patients at risk for serious long-term side-effects [5]. This undesirable situation changed remarkably with the availability of biologics, especially biologics targeting interleukin (IL)-5, a cytokine responsible for the recruitment and activation of eosinophils [6].

One of these biologics is benralizumab, targeting the IL-5-receptor α subunit (IL-5Rα), which has been shown to be very effective in the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma. In phase 3 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) benralizumab treatment has been shown to induce a reduction in maintenance OCS dose and exacerbation frequency and an improvement in pulmonary function and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [7–9]. In addition, results of the recent open-label PONENTE study showed that the majority of patients initiating benralizumab were able to reduce or completely eliminate maintenance OCS [10].

While benralizumab is highly effective in most patients, some patients have no response or only a partial response, resulting in discontinuation or switching to another biologic [11–13]. Given the high burden of disease and treatment costs, there is an urgent need for (bio)markers to predict long-term response to benralizumab [14, 15].

To date, a few studies have addressed the prediction of benralizumab response. Certain baseline characteristics, such as higher exacerbation frequency or higher blood eosinophil counts, are associated with more favourable benralizumab-induced outcomes, but it remains difficult to predict an individuals’ probability of being a responder [13, 16]. Next to baseline characteristics, early treatment effects may contribute to the prediction of long-term outcomes, as shown by a few studies that focused on predicting future asthma exacerbations or therapy response [17–19]. Whether the prediction of long-term response to benralizumab improves with the addition of early treatment outcomes to baseline characteristics is not yet known.

Therefore, we assessed the effects of benralizumab treatment using real-world patient data from the Dutch Severe Asthma Registry RAPSODI [20]. The primary aim of this study was to assess whether treatment outcomes at 3 months – in addition to baseline characteristics – contribute to the prediction of benralizumab response at 1 year. We further, exploratively, developed an easy-to-use prediction tool to enable clinicians to assess an individual patient's probability of long-term response to benralizumab treatment.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This was a nationwide, multicentre observational registry-based real-world population study. The study population consisted of patients with severe asthma included in the Dutch Registry of Adult Patients with Severe asthma for Optimal DIsease management (RAPSODI). In RAPSODI, patient-level data are captured annually in a CASTOR EDC® eCRF from severe asthma patients in 19 Dutch hospitals. Furthermore, patients are asked to fill in 3-monthly electronic questionnaires (PatientCoach®, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; www.patientcoach.lumc.nl/).

All patients ≥18 years old who initiated benralizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma between 1 April 2018 and 1 October 2020 were included in this study. All patients were diagnosed with severe asthma according to the European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines [21]. Anti-IL-5Rα eligibility was based on blood eosinophils ≥0.3×109 cells·L−1 or ≥0.15×109 cells·L−1 for patients using OCS maintenance treatment [22]. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up. Informed consent for this study was collected at registry enrolment. For the current study, a formal approval from a medical ethics committee was waived according to Dutch legislation. The study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (registration number: NL8885).

Measurements

The Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ-6) at baseline, 3 months and 12 months after initiating benralizumab was collected using the application PatientCoach®. Other baseline characteristics at the moment of benralizumab initiation and clinical outcomes after 12 months were collected from the RAPSODI registry and included: patient demographics, asthma characteristics, medication (inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) dose, OCS use, OCS maintenance dose, previous biologic), exacerbation frequency in the 12 months before benralizumab initiation, lung function measurements (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)), inflammatory markers (baseline peripheral blood eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide fraction (FENO)) and comorbidities (nasal polyposis, chronic rhinosinusitis, bronchiectasis). OCS maintenance dose after 3 months of benralizumab treatment was collected from the patients’ records. Clinical outcomes after 12 months were: continuation of benralizumab, exacerbation frequency in the previous 12 months, OCS use, OCS maintenance dose, ACQ-6 and FEV1.

Study definitions

A positive response to benralizumab treatment was defined as continuation of benralizumab after 12 months and having a ≥50% reduction in annual exacerbation frequency or a ≥50% reduction in OCS maintenance dose. These patients were classified as responders. If benralizumab was discontinued at or before the 12 months mark or the patients did not achieve a ≥50% reduction in either OCS maintenance dose or exacerbations, the patients were classified as non-responders. Patients without maintenance OCS and exacerbations at baseline were excluded from the analysis. Asthma exacerbations were defined by at least one of the following criteria: 1) patient-reported use of OCS courses; 2) doubling of maintenance dose of OCS for at least 3 days; and 3) unscheduled emergency visits or hospitalisations for asthma deterioration.

Statistical analysis

Assessment of clinical outcomes

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±sd or median (IQR) as applicable and categorical variables as percentages. Baseline differences between responders and non-responders to benralizumab treatment were compared using t-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests as applicable for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Changes in clinical outcomes pre- and (3 or 12 months) post-benralizumab initiation in the total group and within responder group were assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Predicting response

To investigate predictors of benralizumab response at 12 months, we used logistic regression, including commonly available baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes after 3 months as potential predictors. Variables with >20% missing data were considered not commonly available from clinical practice and were hence left out of the analysis. Variables univariately associated with benralizumab response (p<0.20) were selected for multivariable logistic regression, following a full model approach in order to avoid predictor selection bias and overfitting [23, 24]. Effect-sizes were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Discriminative ability was assessed with the area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) and calibration with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and calibration plots. Based on AUROCs, a choice was made between incorporating either variables at baseline and 3 months or the change in these variables between baseline and 3 months. To assess the added value of the variables at 3 months in the prediction of long-term response, two multivariable models predicting long-term response were compared: a model with only baseline variables and a model with baseline variables combined with 3-month data. AUROCs of both regression models were compared using the DeLong test.

Development of a prediction tool

Based on the univariately selected predictors, an easy-to-use tool was developed in order to predict an individual's probability of being a benralizumab responder. First, continuous variables were categorised according to clinically relevant cut-offs, and a multivariable regression model was constructed. In order to construct a parsimonious model, variables that contributed marginally to the AUROC were excluded from the model. The model was internally validated and corrected for optimism using internal bootstrap resampling (1000 bootstrap samples) [25]. Finally, score points were assigned to the variables based on the regression coefficients. Individual prediction scores were calculated to assess the performance of the model in the study population. Risk categories based on the absolute risk for response were established in order to make the model clinically applicable.

A p-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 and STATA version 16.0.

Results

Patient characteristics at baseline

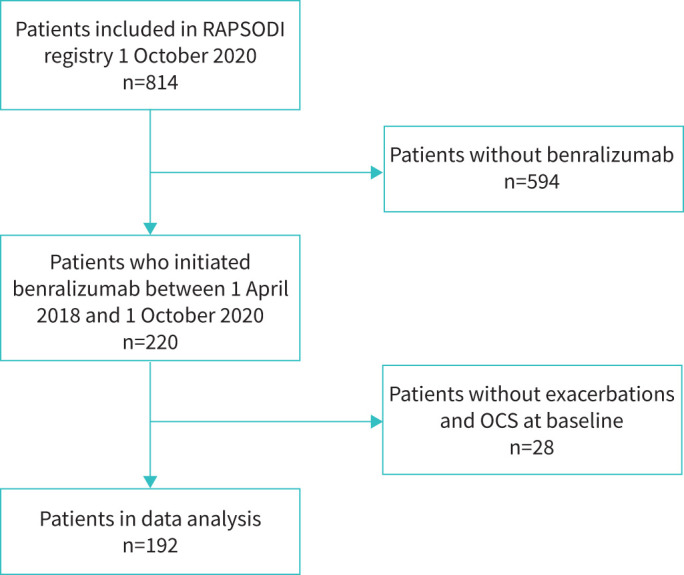

220 out of 814 patients included in the RAPSODI registry on 1 October 2020 initiated benralizumab between 1 April 2018 and 1 October 2020 (figure 1). 28 patients (all switchers from another biologic) did not experience exacerbations in the year prior to benralizumab initiation and had no OCS maintenance treatment at baseline. These patients were unable to improve in exacerbations or OCS dose and were therefore left out of the analyses. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the study population at benralizumab initiation. 48% of the participants were male, the majority of patients had adult-onset asthma and almost half of the patients were previous smokers. 64% of the patients received maintenance OCS when initiating benralizumab and 54.2% of them had previously used another biologic.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of selected patients. OCS: oral corticosteroids.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics for the total population and stratified for non-responders and responders

| Total population | Non-responders | Responders | p-value | |

| Patients n | 192 | 48 | 144 | |

| Age years, mean±sd | 58±13 | 58±13 | 58 (13) | 0.99 |

| Male sex % | 48.4 | 37.5 | 52.1 | 0.080 |

| Body mass index (kg·m−2), mean±sd | 28±5.3 | 28.7±5.9 | 27.7±5.2 | 0.26 |

| Former smoker % | 47.9 | 41.7 | 50.0 | 0.32 |

| Pack-years, median (IQR)# | 11 (5–22) | 10 (5–30) | 11 (6–22) | 0.76 |

| Age of asthma onset years, mean±sd | 41±19 | 37±18 | 42±19 | 0.25 |

| Non-atopic asthma % | 65.2 | 64.4 | 65.5 | 0.90 |

| Late asthma onset % | 80.7 | 75 | 82.6 | 0.245 |

| Exacerbation frequency last year (exacerbations per year), median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.51 |

| ICS daily dose mg (fluticasone equivalents), median (IQR) | 1000 (750–1500) | 1000 (800–1500) | 1000 (750–1125) | 0.38 |

| OCS maintenance on baseline % | 63.5 | 62.5 | 63.9 | 0.86 |

| OCS dose baseline (mg·day−1), median (IQR) ¶ | 10 (5–15) | 10 (7.5–20) | 10 (5–13.8) | 0.025 |

| Previous biologic for severe asthma % | 54.2 | 77.1 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| Ever use of omalizumab % | 14.1 | 22.9 | 11.1 | |

| Ever use of mepolizumab % | 43.8 | 56.3 | 39.6 | |

| Ever use of reslizumab % | 13 | 29.2 | 7.6 | |

| Ever use of dupilumab % | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | |

| ACQ-6 score baseline, median (IQR) | 2.17 (1.67–3.17) | 2.5 (1.85–3.33) | 2.17 (1.5–3.1) | 0.054 |

| FEV1 pre-bronchodilator (%pred), mean±sd | 71.5±22.1 | 67.2±22.9 | 72.9±21.7 | 0.13 |

| FENO (ppb), median (IQR) | 41 (22–73) | 32 (16–60) | 44 (25–74) | 0.061 |

| Blood eosinophils (×109 cells·L−1), median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.1 (0.1–0.4) | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) | 0.013 |

| Blood eosinophils (×109 cells·L−1) % | ||||

| <0.3 | 46.6 | 59.5 | 42.6 | 0.055 |

| ≥0.3 | 53.4 | 40.5 | 57.4 | |

| Bronchiectasis % | 24.8 | 34.5 | 21.7 | 0.17 |

| Nasal polyposis % | 51.5 | 50 | 52 | 0.82 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis % | 62.8 | 64.3 | 62.3 | 0.82 |

IQR: interquartile range; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; OCS: oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalents); ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FENO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide. #: calculated for former smokers; ¶: calculated for patients receiving OCS maintenance treatment on baseline, n=122.

44 (22.9%) patients discontinued benralizumab within 12 months. The reasons for stopping were: failure to reduce symptoms (n=28), failure to reduce OCS (n=24), insufficient effect on pulmonary function (n=20), side-effects (n=7) and other (n=2). Multiple reasons for discontinuing benralizumab were possible. No patients discontinued benralizumab solely based on insufficient effect on pulmonary function. The median (IQR) duration of treatment for patients discontinuing benralizumab was 4 (4–8) months. After discontinuing benralizumab, 22 patients completely ceased the use of biologics, nine switched to another anti-IL-5 biologic and 13 patients switched to anti-IL-4/IL-13 treatment at the follow-up moment.

Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab

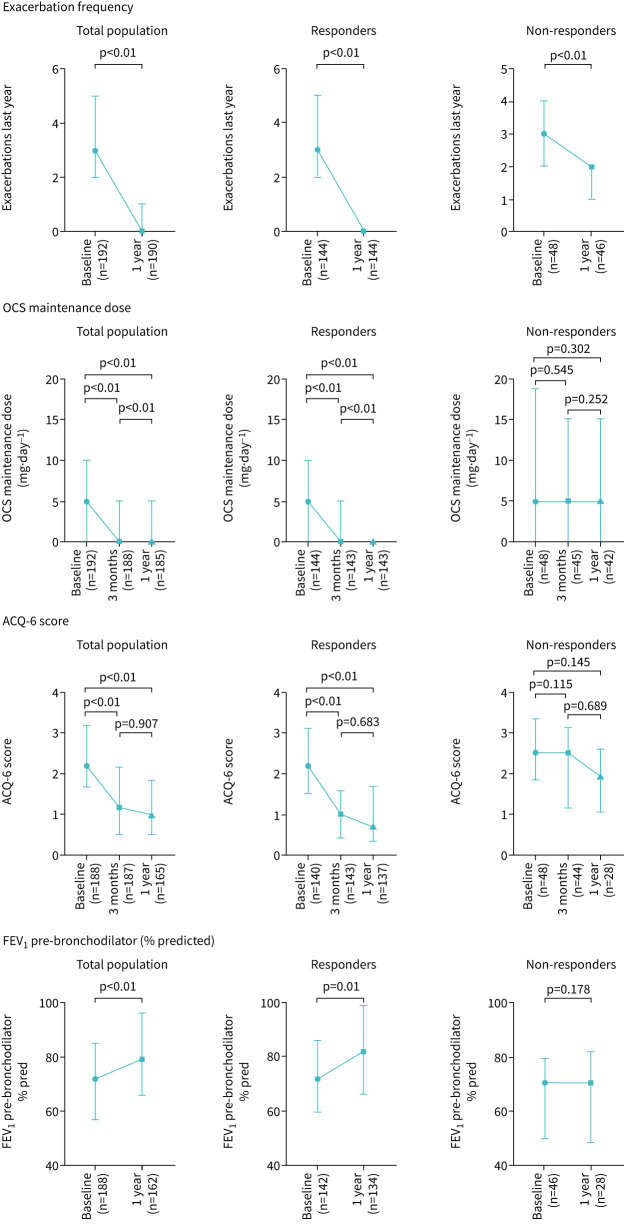

The effect of benralizumab treatment on several asthma-related outcomes is demonstrated in figure 2 and table 2. In the total population, initiating benralizumab led to a statistically significant improvement at 1 year of exacerbation frequency (median (IQR) 3 (2–5) exacerbations per year to 0 (0–1) exacerbations per year, p<0.01) and OCS maintenance dose (5 (0–10) mg·day−1 to 0 (0–5) mg·day−1, p<0.01). In addition ACQ-6 score significantly improved from 2.17 (1.67–3.17) at baseline to 1.0 (0.5–1.83) at 1 year, p<0.01, and FEV1 % predicted from 72% (57–85) to 80% (66–96), p<0.01. A statistically significant improvement of OCS maintenance dose and ACQ-6-score was observed as early as 3 months after initiating benralizumab treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of benralizumab after 12 months on exacerbation rate, maintenance oral corticosteroid (OCS) dose, Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ-6) score and pre-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1 % predicted) for the total population (n=192), responders (n=144) and non-responders (n=48). The available number of patients per time point is shown on the x-axis in brackets.

TABLE 2.

Clinical outcomes to benralizumab treatment for the total population, and stratified for non-responders and responders

| Variable | Total population | Non-responders | Responders | p-value |

| Patients n | 192 | 48 | 144 | |

| Annual exacerbation frequency at baseline | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.51 |

| Annual exacerbation frequency after 1 year | 0 (0–1) | 2 (1–2) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| Change in annual exacerbation frequency after 1 year | −2 (−3– −1) | −1 (−2–0) | −2 (−4– −2) | <0.001 |

| Maintenance OCS dose at baseline mg·day−1 | 5 (0–10) | 5 (0–17.5) | 5 (0–10) | 0.32 |

| Maintenance OCS dose after 3 months mg·day−1 | 0 (0–5) | 5 (0–15) | 0 (0–5) | 0.001 |

| Change in maintenance OCS dose after 3 months mg·day−1 | 0 (−5–0) | 0 (−5–0) | −2.5 (−5–0) | 0.007 |

| Maintenance OCS dose after 1 year mg·day−1 | 0 (0–5) | 5 (0–15) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| Change in maintenance OCS dose after 1 year mg·day−1 | −2. 5 (−6.25–0) | 0 (−5–0) | −3.75 (−7.5–0) | 0.002 |

| ACQ-6 score baseline | 2.17 (1.67–3.17) | 2.5 (1.85–3.33) | 2.17 (1.5–3.1) | 0.054 |

| ACQ-6 score after 3 months | 2.5 (1.15–3.09) | 1.0 (0.43–1.57) | <0.001 | |

| Change in ACQ-6 score after 3 months | −0.83 (−1.57– −0.17) | −0.17 (−0.81–0.38) | −1 (−1.72– −0.34) | <0.001 |

| ACQ-6 score after 1 year | 1 (0.5–1.83) | 1.92 (1.09–2.6) | 0.71 (0.33–1.57) | <0.001 |

| Change in ACQ-6 score after 1 year | −0.96 (−1.66– −0.17) | −0.17 (−1.18–0.34) | −1.04 (−1.67– −0.5) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 baseline % predicted | 72 (57–85) | 70.3 (51–79) | 72 (60–86) | 0.088 |

| FEV1 after 1 year % predicted | 80 (66–96) | 70.5 (49–82) | 82 (66.1–99) | 0.012 |

| Change in FEV1 after 1 year % predicted | 4 (−1.41–12.23) | 1.5 (−1.5–6.5) | 5.3 (−1–16.7) | 0.085 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) unless otherwise stated. OCS: oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalents); ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

144 patients were classified as responders (continuing benralizumab after 12 months and have a ≥50% reduction in either exacerbation frequency or OCS maintenance dose). 48 patients discontinued benralizumab treatment or did not reduce exacerbation rate or OCS maintenance dose ≥50% and were labelled as non-responders.

Baseline characteristics of responders and non-responders are shown in table 1. Responders differed from non-responders in that they were less likely to report the use of a prior biologic and were more often male. Responders tended to have higher levels of FENO and blood eosinophil levels above 0.3×109 cells·L−1. Data on the effect of benralizumab on clinical outcomes for responders and non-responders are illustrated in figure 2 and table 2.

Predicting long-term benralizumab response

To explore whether 3-month data in addition to baseline characteristics can improve prediction of benralizumab response at 1 year, we used univariate logistic regression analyses (table 3). Male sex, no previous biologic use, lower OCS dose at baseline, lower ACQ-6 score at baseline, higher FEV1 at baseline, baseline blood eosinophils ≥0.3×109 cells·L−1, lower OCS dose at 3 months and lower ACQ-6 at 3 months were univariately associated with benralizumab response (p<0.20) and included in the multivariable analyses. 170 patients had complete data for all characteristics.

TABLE 3.

Univariate logistic regression analysis predicting long-term benralizumab response

| Variables at baseline | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Male sex | 1.81 (0.93–3.54) | 0.082 |

| Body mass index kg·m−2 | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 0.26 |

| Age years | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.99 |

| Former smoker | 0.71 (0.37–1.38) | 0.32 |

| Non-atopic asthma | 1.05 (0.52–2.11) | 0.90 |

| Adult-onset asthma | 0.63 (0.29–1.38) | 0.25 |

| Exacerbation frequency year before start (exacerbations per year) | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 0.43 |

| ICS dose mg, fluticasone equivalents | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.27 |

| OCS dose mg·day−1# | 0.97 (0.94–1.01) | 0.076 |

| No previous biologic | 3.87 (1.83–8.17) | <0.001 |

| ACQ-6 score | 0.74 (0.53–1.02) | 0.063 |

| FEV1 pre-bronchodilator % predicted | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.13 |

| Blood eosinophils ×109 cells·L−1 | 1.47 (0.76–2.84) | 0.26 |

| Blood eosinophils ≥0.300×109 cells·L−1 | 1.98 (0.98–4.00) | 0.058 |

| Nasal polyposis | 0.92 (0.45–1.88) | 0.83 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 1.09 (0.53–2.25) | 0.82 |

| Variables at 3 months | ||

| OCS dose mg·day−1# | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | <0.001 |

| ACQ-6 score | 0.34 (0.24–0.50) | <0.001 |

ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; OCS: oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalents); ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s. #: patients without maintenance OCS have an OCS dose of 0 mg·day−1. Variables with p<0.2 in bold.

Table 4 demonstrates the multivariable logistic regression analyses of two models, the first model using only predictive parameters at baseline and the second model with predictors at baseline and 3 months. The model with only baseline predictors corresponded to an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI 0.63–0.80); the Hosmer–Lemeshow test did not indicate bad fit (p=0.95). The model using baseline parameters combined with 3-month parameters corresponded to a higher AUROC than baseline predictors alone, namely 0.85 (95% CI 0.78–0.92). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed no indication of bad fit (p=0.41); for the calibration plots, see supplementary figure S1. The AUROCs of both models were statistically significantly different (p=0.001). Two exploratory analyses with only outcomes at 3 months and only the ACQ-6 at 3 months are presented in supplementary table S2. Both analyses yielded lower AUROCs than the model using baseline parameters combined with 3-month parameters.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis, including baseline and 3-month characteristics, predicting long-term benralizumab response, as compared to a model including baseline characteristics only

| Variable | Baseline only | Baseline and 3 months | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Male sex | 1.54 (0.71–3.32) | 0.28 | 1.80 (0.69–4.72) | 0.23 |

| OCS dose at baseline mg·day−1 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.27 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 0.94 |

| No previous biologic | 3.61 (1.47–8.85) | 0.005 | 2.84 (1.00–8.06) | 0.051 |

| ACQ-6 score at baseline | 0.84 (0.56–1.25) | 0.38 | 1.58 (0.88–2.81) | 0.13 |

| Baseline blood eosinophils ≥0.300×109 cells·L−1 | 1.22 (0.54–2.79) | 0.64 | 1.25 (0.47–3.32) | 0.66 |

| FEV1 pre-bronchodilator % predicted | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.61 | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.65 |

| OCS dose at 3 months mg·day−1# | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 0.031 | ||

| ACQ-6 score at 3 months | 0.32 (0.19–0.54) | <0.001 | ||

| Area under ROC (95% CI) | 0.72 (0.63–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | <0.001 |

OCS: oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalents); ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ROC: receiver-operating characteristic. #: patients without maintenance OCS have an OCS dose of 0 mg·day−1.

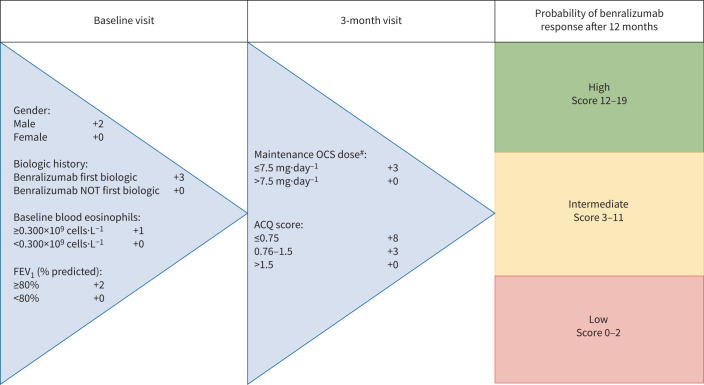

Clinical assessment of long-term response

Based on the multivariable logistic regression model from table 4, including both baseline and predictors at 3 months, we proposed an easy-to-use response prediction tool in table 5 and figure 3. Removal of the ACQ-6 at baseline and OCS dose at baseline had a minimal effect (−0.03) on the AUROC. Internal validation yielded a correction for optimism of 0.005 decrease in the AUROC. Three score categories for probability of long-term benralizumab response were established: low (score 0–2), intermediate (score 3–11) and high (score ≥12). Patients with a score ≥12 at 3 months had a very high probability (97%, 95% CI 91–99%) of benralizumab response after 12 months. The number of patients per score (0–19) and the proportion of patients and likelihood ratios per prediction category are described in supplementary table S1.

TABLE 5.

Development of a prediction tool, predicting long-term benralizumab response

| Variable | Rounded points | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Female sex | 0 | Ref. | |

| Male sex | 2 | 1.57 (0.66–3.76) | 0.31 |

| Previous biologic | 0 | Ref. | |

| No previous biologic | 3 | 2.74 (1.01–7.46) | 0.048 |

| Baseline blood eosinophils <0.300×109 cells·L−1 | 0 | Ref. | |

| Baseline blood eosinophils ≥0.300×109 cells·L−1 | 1 | 1.02 (0.40–2.61) | 0.97 |

| FEV1 <80% predicted | 0 | Ref. | |

| FEV1 ≥80% predicted | 2 | 1.78 (0.70–4.53) | 0.23 |

| OCS dose at 3 months >7.5 mg·day−1 # | 0 | Ref. | |

| OCS dose at 3 months ≤7.5 mg·day−1 # | 3 | 3.07 (1.15–8.19) | 0.025 |

| ACQ-6 score at 3 months | |||

| ≤0.75 | 8 | 7.81 (2.38–25.61) | <0.001 |

| 0.76–1.5 | 3 | 3.19 (1.14–8.94) | 0.027 |

| >1.5 | 0 | Ref. | |

| Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | - | 0.82 (0.75–0.89) | <0.001 |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; OCS: oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalents); ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; ROC: receiver-operating characteristic. #: patients without maintenance OCS have an OCS dose of 0 mg·day−1.

FIGURE 3.

Benralizumab response score. The prediction tool combines baseline characteristics and outcomes at 3 months to predict long-term benralizumab response. Based on the score, the individual patient has a high (97%, 95% CI 91–99%), intermediate (67%, 95% CI 57–77%) or low (25%, 95% CI 3–65%) probability of benralizumab response after 12 months. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire. #: patients without maintenance oral corticosteroids (OCS) have an OCS dose of 0 mg·day−1.

Discussion

The present study shows that treatment outcomes at 3 months, in addition to baseline characteristics, contribute to the prediction of benralizumab response at 1 year in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. In this large nationwide real-world population, benralizumab treatment significantly improved exacerbation frequency, OCS maintenance dose, ACQ-6 and FEV1. The majority (75%) of the 192 patients were responders to benralizumab treatment at 12 months. The prediction of response to benralizumab was significantly improved by adding two easy-to-assess parameters at 3 months (OCS dose and ACQ-6) to a set of baseline parameters, resulting in a predictive model with a higher AUROC and hence a higher discriminative capability. These results suggest that combining baseline data and short-term treatment outcomes and incorporating them into a simple tool, such as the one we propose, could help clinicians predict future response to benralizumab and thus promote the efficient use of costly biologics.

The beneficial effects of benralizumab, as well as its rapid onset, which we demonstrate in this study are in line with previous findings from RCTs and real-world studies [7–10, 19]. However, in terms of response rate, we identified 25% non-responders, which is higher than the 13–14% reported in two UK studies [12, 19]. This not only may be due to the higher number of patients with prior biologic use in our study but also the very strict eligibility criteria used in the UK and in these British studies, which may have selected a more exacerbation-prone population resulting in lower rates of non-responders than experienced in other real-world settings.

The prediction of response to benralizumab has been studied before. Studies predicting response based on baseline characteristics found higher blood eosinophils, more frequent exacerbations, use of maintenance OCS, nasal polyposis, adult-onset asthma and higher levels of FEV1 as important predictive parameters [12, 13, 16, 26]. Early treatment outcomes as a parameter in predicting future response to benralizumab was studied in a single study in which an ACQ-6 improvement of ≥0.5 units 4 weeks after initiating benralizumab predicted response at 48 weeks [19]. Our study confirms and extends these findings, as we showed that a combination of baseline characteristics and early treatment outcomes was most successful in identifying patients that are most likely to respond to benralizumab.

We found that 87.5% of biologic-naïve patients were responders versus 64.4% in patients with a previous biologic. No prior use of a biologic emerged as an important predictor of long-term response to benralizumab. In a recent study it was stated that benralizumab is effective in severe asthma independent of previous biologic use [19]. Also in the present population, patients with or without previous treatment with a biologic for severe asthma significantly benefited from benralizumab treatment (data not shown). However, the individual probability of responding to benralizumab treatment was significantly higher in patients without previous biologic use, justifying its inclusion in the predictive model.

A major strength of this study is that it analyses the largest real-world population of benralizumab-treated patients, using the Dutch RAPSODI registry, which collects longitudinal data in a standardised way, both by clinicians and 3-monthly by patients themselves. This unique registry allowed us to include treatment outcomes at 3 months in the analysis of predictors of long-term response to benralizumab. This study also has limitations inherent to the real-world character and observational design of the study, such as lack of a control group and possible unnoticed confounders in the comparison of clinical outcomes. Further, incompleteness of some data meant that certain parameters, such as FENO, could not be used in the prediction model. In addition, the blood eosinophils before initiating any biological treatment for the patients switching from another biologic or data on other comorbidities were not available. As limiting as this may seem, it reflects real-world practice and ultimately we are looking for predictive parameters that are easy to assess in every clinical practice and a prediction tool that is widely applicable, as presented in our study. We have optimised our predictive model through internal validation, but realise that external validation in another severe asthma population is required to confirm the applicability of our model and tool. Unfortunately, we do not have access to such an independent second population. Finally, we conducted our study at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic increasingly dominated the world. This likely reduced both the rate of exacerbations and the willingness of clinicians or patients to discontinue or switch biologics and may therefore have resulted in fewer patients with non-response. Nevertheless, the number of non-responders in our study is still higher than observed in other studies [12, 19], suggesting that the results were unlikely to have been significantly influenced in this regard, although we cannot exclude such an effect.

Our results have both clinical and research implications. We demonstrated a predictive model and developed a simple clinical scoring tool to help clinicians assess whether a patient is likely to respond to benralizumab treatment in the long term. Where baseline characteristics alone are insufficient to predict an individual's probability of being a responder, our addition of parameters at 3 months succeeds in identifying patients with 97% probability on long-term benralizumab response. These patients may require less intensive monitoring, helping clinicians to allocate their valuable time. Further research will need to determine whether clinical tools integrating biomarkers, phenotypic features and clinical outcomes, such as the one proposed in our study, are a valuable addition to clinical practice, not only in predicting response to benralizumab or other biologics but, even more challenging, in predicting non-response. The optimal set of variables to incorporate in these clinical tools might involve variables that were not available in our dataset, for example exacerbation frequency after 3 months. In addition, the best moment for response evaluation may differ between patients, as some patients may require more time to be labelled a responder. The optimal moment to evaluate treatment response needs to be elucidated. Evidence, such as that provided in our manuscript, adds in this process.

In conclusion, this nationwide real-world study confirms the beneficial effects of benralizumab treatment on several clinical outcomes in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. The prediction of long-term response to benralizumab was clearly improved by adding treatment outcomes at 3 months to baseline characteristics and long-term response could be determined using an easy-to-use scoring tool. Prediction tools, such as the one proposed in our study, are promising additions to clinical practice, assisting clinicians in their clinical decision-making and further optimising treatment with costly biologics.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00559-2022.SUPPLEMENT (404.8KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nic Veeger from the Medical Centre Leeuwarden Department of Epidemiology for his contribution to the statistical analysis. This study was conducted on behalf of RAPSOSI (the Dutch Registry of Adult Patients with Severe Asthma for Optimal Disease Management) (full acknowledgement list in the supplementary material).

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: J.A. Kroes reports a grant from AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest: K. De Jong has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Hashimoto has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S.W. Zielhuis reports a grant from AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Genzyme Regeneron, Eli-Lilly and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Conflict of interest: E.N. Van Roon has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.K. Sont reports a grant from AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest: A. Ten Brinke reports grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, TEVA and Sanofi-Genzyme Regeneron, and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, TEVA, AstraZeneca and Sanofi-Genzyme Regeneron, unrelated to this work.

Support statement: This research was conducted with unrestricted financial support from AstraZeneca BV. RAPSODI is financially supported by an unrestricted grant from GSK, Novartis Pharma, AstraZeneca, Teva and Sanofi-Genzyme Regeneron. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Pizzichini MM, Pizzichini E, Clelland L, et al. Prednisone-dependent asthma: inflammatory indices in induced sputum. Eur Respir J 1999; 13: 15–21. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13101599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa AR, Marshall RP, Warnock LC, et al. Responsiveness to oral prednisolone in severe asthma is related to the degree of eosinophilic airway inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy 2017; 47: 890–899. doi: 10.1111/cea.12954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bragt JJMH, Adcock IM, Bel EHD, et al. Characteristics and treatment regimens across ERS SHARP severe asthma registries. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901163. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01163-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) . Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients. 2021. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/SA-Pocket-guide-v3.0-SCREEN-WMS.pdf

- 5.Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow AN, Price DB, et al. Systematic literature review of systemic corticosteroid use for asthma management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 276–293. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201904-0903SO [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Principe S, Porsbjerg C, Bolm Ditlev S, et al. Treating severe asthma: targeting the IL-5 pathway. Clin Exp Allergy 2021; 51: 992–1005. doi: 10.1111/cea.13885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2128–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31322-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2448–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menzies-Gow A, Gurnell M, Heaney LG, et al. Oral corticosteroid elimination via a personalised reduction algorithm in adults with severe, eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (PONENTE): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 47–58. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00352-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eger K, Kroes JA, Ten Brinke A, et al. Long-term therapy response to Anti-IL-5 biologics in severe asthma: a real-life evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 1194–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kavanagh JE, Hearn AP, Dhariwal J, et al. Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2021; 159: 496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Predictors of enhanced response with benralizumab for patients with severe asthma: pooled analysis of the SIROCCO and CALIMA studies. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 51–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30344-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroes JA, Zielhuis SW, van Roon EN, et al. Prediction of response to biological treatment with monoclonal antibodies in severe asthma. Biochem Pharmacol 2020; 179: 113978. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brusselle GG, Koppelman GH. Biologic therapies for severe asthma. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 157–171. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2032506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Bona D, Crimi C, D'Uggento AM, et al. Effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma: distinct sub-phenotypes of response identified by cluster analysis. Clin Exp Allergy 2022; 52: 312–323. doi: 10.1111/cea.14026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroes JA, Zielhuis SW, van der Meer AN, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures after 8 weeks of mepolizumab treatment and long-term outcomes in patients with severe asthma: an observational study. Int J Clin Pharm 2021; 44: 570–574. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01362-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boer S, Sont JK, Loijmans RJB, et al. Development and validation of personalized prediction to estimate future risk of severe exacerbations and uncontrolled asthma in patients with asthma, using clinical parameters and early treatment response. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 175–182.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson DJ, Burhan H, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Benralizumab effectiveness in severe asthma is independent of previous biologic use. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 1534–1544.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RAPSODI registry . www.rapsodiregister.nl/ Date last accessed: 12 December 2021.

- 21.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Longziekten en Tuberculose (NVALT) . Diagnostiek en behandeling van ernstig astma. 2020. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/diagnostiek_en_behandeling_van_ernstig_astma/startpagina_-_ernstig_astma.html Date last accessed: 31 March 2022. [PubMed]

- 23.Shipe ME, Deppen SA, Farjah F, et al. Developing prediction models for clinical use using logistic regression: an overview. J Thorac Dis 2019; 11: S574–S584. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.01.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M, et al. Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart 2012; 98: 683–690. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr, Borsboom GJ, et al. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54: 774–781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleecker ER, Wechsler ME, FitzGerald JM, et al. Baseline patient factors impact on the clinical efficacy of benralizumab for severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: 1800936. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00936-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00559-2022.SUPPLEMENT (404.8KB, pdf)