Abstract

Although abortion and euthanasia are highly contested issues at the heart of the culture war, the moral foundations underlying ideological differences on these issues are mostly unknown. Given that much of the extant debate is framed around the sanctity of life, we argued that the moral foundation of purity/sanctity—a core moral belief that emphasises adherence to the “natural order”—would mediate the negative relationship between conservatism and support for abortion and euthanasia. As hypothesised, results from a nation‐wide random sample of adults in New Zealand (N = 3360) revealed that purity/sanctity mediated the relationship between conservatism and opposition to both policies. These results demonstrate that, rather than being motivated by a desire to reduce harm, conservative opposition to pro‐choice and end‐of‐life decisions is (partly) based on the view that ending a life, even if it is one's own, violates God's natural design and, thus, stains one's spiritual purity.

Keywords: Abortion, Conservatism, Euthanasia, Moral foundations theory, Purity

As a Christian, I believe in the sanctity of life, and that death is a part of life.—Desmond Tutu

Abortion and euthanasia are arguably two of the most contested issues within politics (Rae et al., 2015) and are often highly moralised in public discourse. For example, opponents of both issues routinely invoke the “sanctity of life” to defend their positions (Baranzke, 2012; Jelen & Wilcox, 2005; Moulton et al., 2006). Yet despite this potentially powerful rhetoric, public opinion is broadly supportive of increased access to both abortion and euthanasia (see Emanuel et al., 2016; Osborne et al., 2022; Young et al., 2019), with such sentiment reflected in changing legislation across the world. For example, New Zealand (i.e., the location of the current study) legalised both abortion and euthanasia in 2020. Similarly, legislative reforms have been proposed or enacted across several countries to increase access to legal abortions (Ishola et al., 2021) or euthanasia (Mroz et al., 2021), including in Australia (Millar & Baird, 2021), Columbia (Daniels, 2022), Ecuador (Solano, 2022) and Northern Ireland (Thomson, 2019).

Despite these notable examples of progressive change, opposition to legal abortion and/or euthanasia remains strong amongst some constituencies. Indeed, these issues are often divided by party lines, with conservatives expressing greater opposition to abortion and euthanasia than their liberal counterparts (Koleva et al., 2012). For example, although knowledge of Roe v. Wade correlates positively with support for upholding the ruling (see Crawford et al., 2021), this relationship is moderated by political affiliation. Specifically, knowledge of the ruling increases Democrats' support, but decreases Republican's support, for Roe v. Wade. Democrats are also significantly less likely than Republicans to oppose euthanasia (Sabriseilabi & Williams, 2022). Thus, abortion and euthanasia sit at the heart of the current culture war between liberals and conservatives (Dillon, 1996; Hout, 1999).

What explains these ideological differences in support for both issues? Although anti‐abortion/euthanasia rhetoric is often framed in terms of care‐based, altruistic concerns where protecting life is of upmost importance (Beckwith, 2001), such explicit justifications often belie the underlying moral concern (Rottman et al., 2014). For example, Deak and Saroglou (2015) situated the debate within a moral foundations framework and showed that, rather than being associated with the care‐based “individualising” moral foundations of harm and fairness, opposition to euthanasia and abortion is based in the “binding” moral foundations of loyalty, authority and purity (Graham & Haidt, 2010). Silver (2020) similarly argued that conservative opposition to abortion and euthanasia was rooted in adherence to a binding moral framework that prioritises moral absolutism and group norms over individual needs. Thus, moral opposition to abortion and euthanasia appears to be a matter of preventing the violation of group norms, rather than protecting the well‐being of those involved. Although this work illustrates the moral foundations underlying opposition to issues related to the “sanctity” of life, research has yet to examine the possibility that such views on morality explain the current partisan divide in attitudes outside of a religious‐majority country.

Our work aims to address this oversight by examining the role moral foundations play in explaining the deep divisions between conservatives and liberals' attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia using a nation‐wide random sample of adults from New Zealand. Given that New Zealand is a religious‐minority country (Lineham, 2014), religious norms regarding abortion and euthanasia may be less salient to our sample, thereby leaving political ideology to play a greater role in shaping moral thinking. We thus begin by examining ideological differences in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia before examining how moral foundations theory might help explain why the left and the right are divided on these issues. We then highlight the importance of the moral foundations (particularly purity) in connecting conservatism to opposition to abortion and euthanasia before summarising the aims and hypotheses of the study.

Ideological differences in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia

Although conservatism consistently correlates with opposition to abortion and euthanasia (Koleva et al., 2012), research has only identified tentative explanations for this relationship. One likely possibility is that conservative opposition to both issues is explained by religiosity, as religious identification correlates positively with both conservatism (Guth et al., 2006) and anti‐abortion attitudes (Kelley et al., 1993; Osborne et al., 2022). Religious identification also appears to underlie anti‐euthanasia attitudes (Bulmer et al., 2017). For example, religiosity (but not spirituality) predicts opposition to euthanasia, with Evangelicals and Catholics expressing stronger opposition than mainline Protestants (Sabriseilabi & Williams, 2022). Similarly, markers of religious affiliation, including identification with a religion or religious denomination, as well as church attendance, are strong predictors of opposition to physician‐assisted suicide (Bulmer et al., 2017; Danyliv & O'Neill, 2015). Nevertheless, controlling for conservatism eliminates the relationship between religiosity and opposition to euthanasia (Ho & Penney, 1992), suggesting that political ideology is a more proximal predictor than religious identification of attitudes towards euthanasia.

Given the above literature, left–right differences in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia may simply be a matter of ideological disagreement, with conservatives showing greater adherence to proscriptive norms against abortion/euthanasia. However, examination of anti‐abortion and euthanasia rhetoric tells a different story, often suggesting that conservative opposition is motivated by underlying concerns for the vulnerable—a position that includes conceptualising the preborn as human (MacInnis et al., 2014). Notably, such discourse is often accompanied by paternalistic stereotypes that portray women who seek abortions as victims who need to be “saved” from their own decisions (see Pizzarossa, 2019; Silver, 2020).

Despite this rhetoric, MacInnis et al. (2014) found that ideological differences in abortion support were not explained by perceptions of preborn “humanness.” Similarly, Skitka et al. (2018) found that the moralisation of abortion attitudes was rooted in neither harm‐based nor intuitive considerations. Instead, Deak and Saroglou (2015) showed that the binding foundations of authority, loyalty and purity strongly predicted opposition to abortion and euthanasia. Thus, rather than harm‐based considerations for the well‐being of those involved, opposition to abortion and euthanasia may reflect adherence to rigid, group norms rooted in a perception of natural, immutable moral laws.

The moral roots of the left–right divide

One potential way to explain ideological differences in opposition to both abortion and euthanasia is to focus on how people moralise the issues. According to moral foundations theory, five core moral beliefs exist across cultures as a response to shared adaptive challenges: authority, loyalty, purity, harm and fairness (Graham & Haidt, 2010). Notably, past work has validated this five‐factor structure across a range of contexts, including in New Zealand (Davies et al., 2014), Japan (Kitamura & Matsuo, 2021) and Turkey (Yilmaz et al., 2016). Moreover, the five‐factor structure provides a good fit to data from both WEIRD and non‐WEIRD cultures (see Doğruyol et al., 2019; Graham et al., 2013).

Despite being universal, the importance that cultures and subcultures—including religious subgroups—place on these five moral foundations may vary considerably (Graham et al., 2013). Indeed, differences in religious and political ideologies are associated with differing patterns of endorsements of the moral foundations (see Hannikainen et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2016; Koleva et al., 2012). For example, liberals generally value the “individualising” foundations of care and fairness, reflecting a focus on the behaviour and outcomes of individuals within the context of social groups (see Graham et al., 2013; Hannikainen et al., 2017; Weber & Federico, 2013). In turn, these “liberal” moral foundations of care and fairness correlate positively with pro‐environmental attitudes (Milfont et al., 2019). By contrast, conservatives value all five foundations and place a stronger emphasis on the “binding” moral foundations of respect for authority, ingroup loyalty and purity/sanctity compared to liberals (Graham & Haidt, 2010; Turner‐Zwinkels et al., 2021; Van Leeuwen & Park, 2009). These foundations are “binding,” as they reflect a preference for the suppression of individual needs or desires in pursuit of ingroup bonds and cohesion (Mooijman et al., 2018).

Within the framework of moral foundations theory, abortion and euthanasia are often seen as violating inherently conservative values, including sexual purity, and religious belief (Kelley et al., 1993; Patev et al., 2019; Woodrum & Davison, 1992). Indeed, past work has demonstrated that conservative opposition to abortion is rooted in the legitimisation of sex‐based asymmetries (Huang et al., 2014), suggesting anti‐abortion attitudes are driven by a motivation to maintain group cohesion over individual needs. Thus, the binding moral foundations may help to explain the connection between conservatism and opposition to abortion and euthanasia.

Purity and the sanctity of life

Although all three binding foundations are implicated in explaining attitudes towards these issues, purity/sanctity seems the most likely moral foundation to connect conservative beliefs to opposition towards abortion and euthanasia. Purity (or sanctity) examines concern for corruption, defilement and imperfection, or otherwise deviancy from that which is sacred (McAdams et al., 2008). Yet, while purity values are a strong predictor of religious beliefs in New Zealand (Bulbulia et al., 2013), they extend beyond religious content. Indeed, purity values may encompass any belief that upholds norms which, when violated, provoke feelings of disgust, as well as those which emphasise either spiritual or physical cleanliness (Haidt & Graham, 2007). Accordingly, purity concerns correlate positively with disgust sensitivity, particularly with regard to sexual behaviour and norm violation (van Leeuwen et al., 2017). For example, disgust/purity concerns are associated with opposition to homosexuality, premarital sex and pornography (Adams et al., 2014; Feinberg et al., 2014), as well as prostitution (Silver et al., 2022) and other groups that threaten traditional sexual morality (Crawford et al., 2014). Purity also correlates positively with endorsement of abstinence (Barnett et al., 2018). Thus, purity appears to moralise group norms by enshrining the body as sacred and viewing the “natural order” as inviolable, or through belief in divine law. Consistent with this perspective, moral opposition to abortion and euthanasia is often framed in terms of purity concerns about sexuality or the perception that God (and, hence, God's creation) is perfect (McAdams et al., 2008). Opposition to a woman's right to choose may therefore be based in the view that abortion violates sexual purity (Jelen, 2014). Rottman et al. (2014) similarly argue that moral condemnation of suicide is rooted in disgust responses and purity beliefs regarding the state of the victims' souls.

Given the above evidence, perceived norm violations such as abortion and euthanasia may be viewed by some as a rebellion against God's design (Kelley et al., 1993). Specifically, opponents to abortion often position life as a gift from God and, thus, sacred and inherently valuable (Jelen, 2014). As such, ending life through either euthanasia or abortion may be seen by some as a contestation of God's infallibility, as well as a violation of one's collective morals. Hence, purity not only characterises abortion and euthanasia as morally wrong, but also views those who support these policies as spiritually “contaminated.” In this way, purity reinforces opposition to abortion and euthanasia by characterising such actions as a stain on one's spiritual purity.

Current study

The current study examines ideological differences in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. Whereas past research demonstrates that liberals support both issues more than do conservatives, the underlying mechanism responsible for these associations has been largely ignored. To these ends, we examined the possibility that the moral foundation of purity mediates the relationship between conservatism and opposition to both abortion and euthanasia. In testing these hypotheses, we differentiate between two scenarios capturing abortion attitudes: abortion when the mother's life was in danger (i.e., traumatic abortion 1 ) and abortion under any circumstances (i.e., elective abortion). These two approaches capture many of the distinct circumstances surrounding abortion and are well‐established within the literature (see Osborne et al., 2022), with factor analyses yielding two‐factor solutions in both New Zealand (Huang et al., 2016) and the United States (Osborne et al., 2022).

Although both scenarios can be framed as moral concerns, the salience of Purity‐based concerns likely differ across traumatic and elective abortion. Indeed, because elective abortion does not involve a threat to the woman's life, moral concerns outside of the realm of Purity (e.g., harm) should be less salient when abortions are sought for elective reasons. Conversely, given the potential threat to the woman's life, abortion for traumatic reasons should increase the salience of care‐based moral concerns (e.g., harm) and other‐oriented motives (e.g., loyalty) to a greater extent than does elective abortion. Thus, traumatic abortion provides a “hard test” of our hypothesis that conservatism would have an indirect effect on abortion attitudes via Purity‐based concerns.

Purity concerns play a disproportionate role in driving attitudes towards many social controversies and correlate strongly with a belief in the sanctity of life (Koleva et al., 2012). For example, anti‐abortion activists often frame the decision to terminate a pregnancy as a stain on one's spiritual purity through violation of sacred law or the “natural” order (Jelen, 2014). Similarly, euthanasia, despite lacking a personal victim, is seen as violating traditional norms surrounding spiritual purity (Silver, 2020). As such, we hypothesized that the moral foundation of purity/sanctity would correlate negatively with support for both forms of abortion and euthanasia.

To demonstrate the unique effect of purity on these issues, we statistically adjusted for the other moral foundations and demographic covariates. As previously noted, there is a strong negative correlation between religiosity and support for abortion (Osborne et al., 2022) and euthanasia (Bulmer et al., 2017). Thus, participants' identification with a religious or spiritual group was included as a covariate in our analyses. Although this measure may overlook important nuances across distinct religious beliefs, it allowed us to adjust for the relationships religious beliefs in general have with both conservatism and the moral foundation of purity/sanctity.

We also included ethnic group membership as a covariate, as some research indicates that minority groups are more likely than ethnic majorities to be religious (Wilcox, 1992). Finally, we controlled for age, gender, and narcissism, as these factors are associated with euthanasia support (Draper et al., 2010). Indeed, Draper et al. noted that narcissism is one of the main predictors of whether people can come to terms with, and adapt to, both mental and physical decline, as well as the effects of old age. By adjusting for these variables in our analyses, we focus on the unique effects of both conservatism and the moral foundation of purity/sanctity on two issues at the heart of the current culture war (namely, abortion and euthanasia).

METHOD

Ethical compliance

Data collection for the current study, as well as the broader project from which these data are derived, was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. Specifically, the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study (NZAVS) is reviewed every 3 years by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee and was most recently approved on 26 May 2021 for an additional 3 years (reference number UAHPEC22576). Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study.

Sampling procedure

Data for the current study came from the NZAVS—a nationwide longitudinal panel study that began in 2009. Participants were randomly sampled from the New Zealand electoral roll, which represents all citizens over 18 years of age who were eligible to vote (regardless of whether they chose to). The sample size of the Time 1 wave (2009) was 6518. While the proportion of those retained from the initial sample declined over the years, the NZAVS retained 59% of participants from Time 1 (when adjusted for mortality) at Time 6. Despite being based on a random sample, the NZAVS tends to overrepresent women, as well as New Zealand Europeans/Pākehā and Māori, while underrepresenting men, Pacific Islanders, and Asian peoples (see Satherley et al., 2015).

For this study, we focused on data from Time 3.5 and Time 6, as these were the only two time points that included our variables of interest. Notably, these data were collected before New Zealand passed the End of Life Choice Act (i.e., a binding public referendum) and the Abortion Legislation Act, both of which took place in 2020. Time 3.5 (2012, mid‐year) of the NZAVS was a supplementary online‐only questionnaire sent to Time 3 (2011) participants who had provided their email addresses earlier in the year. Time 3.5 contained responses from 4514 participants comprised of 2811 (62.3%) women and 1569 (34.8%) men with a mean age of 49.12 years (SD = 15.67). Time 6 (2014/2015) of the NZAVS consisted of 15,820 participants comprised of 10,002 (63.2%) women and 5798 (36.6%) men with a mean age of 49.33 (SD = 14.03). Of these participants, 3360 participants answered our variables of interest (i.e., 74.4% of the sample who completed the Time 3.5 measures).

Participants

Of our 3360 participants, 63.6% (2136) were women and 36.4% (1224) were men. The age range was 18–98, with a mean age of 48.19 (SD = 15.2). In terms of religious identification, 61.2% (2058) indicated that they were religious, while 38.8% (1302) indicated they were not. As for ethnicity, 84.7% (2846) of participants identified as New Zealand European, while 15.3% (514) identified with an ethnic minority group (i.e., Māori, Pacifica or Asian).

Measures

The current study examined support for euthanasia and abortion, the five moral foundations (see Graham & Haidt, 2010), and political orientation, as well as relevant covariates. Unless noted, all items were rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. Items were interspersed within the larger omnibus NZAVS survey containing other measures outside the scope of this study. Previous work has demonstrated the validity of these measures in the New Zealand context (see Davies et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016; Osborne et al., 2022).

Predictors

Moral foundations were assessed at Time 3.5 using the moral foundations questionnaire, a 30‐item measure of people's endorsement of each of the following five moral concerns: Harm, Fairness, Ingroup, Authority, and Purity (see Graham et al., 2011).

Harm was examined using six items including “Compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial value” and “One of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenceless animal” (α = .647).

Fairness was examined using six items including “When the government makes laws, the number one principle should be ensuring that everyone is treated fairly” and “Justice is the most important requirement for a society” (α = .610).

Ingroup was examined using six items including “I am proud of my country's history” and “It is more important to be a team player than to express oneself” (α = .707).

Authority was examined using six items including “Respect for authority is something all children need to learn” and “If I were a soldier and disagreed with my commanding officer's orders, I would obey anyway because that is my duty” (α = .751).

Purity was examined using six items including “People should not do things that are disgusting, even if no one is harmed” and “Chastity is an important and valuable virtue” (α = .840).

Attitudes towards abortion was assessed at Time 6 using two items examining support/opposition for “legalised abortion” (a) “when the woman's life is endangered” (traumatic abortion) and (b) “regardless of the reason” (elective abortion). Both items were rated on a 1 (strongly oppose) to 7 (strongly support) scale.

Attitudes towards euthanasia was assessed for the first time in the NZAVS at Time 6 using a single item: “Suppose a person has a painful incurable disease. Do you think that doctors should be allowed by law to end the patient's life if the patient requests it?” Participants rated their support on a 1 (definitely no) to 7 (definitely yes) scale.

Political orientation was assessed at Time 6 by asking participants to “…rate how politically liberal versus conservative you see yourself as being” on a 1 (extremely liberal) to 7 (extremely conservative) scale.

Covariates

Our model examined the indirect effects of conservatism on attitudes towards elective abortion, traumatic abortion and euthanasia via the moral foundations while simultaneously adjusting for relevant covariates. These covariates included ethnic majority/minority status, religious identification, narcissism, age and gender. Majority/minority status was assessed using ethnicity, which, along with gender, was assessed using open‐ended questions at Time 3.5. Dummy codes were created for ethnicity (0 = NZ European/Pakeha; 1 = minority) and gender (0 = woman; 1 = man). Gender was included as a covariate as past work reveals inconsistent gender differences in attitudes towards abortion (Osborne et al., 2022). Religious identification was assessed with a single item, “Do you identify with a religious and/or spiritual group?” (0 = no; 1 = yes). Narcissism was assessed with the following two items: “Feel entitled to more of everything” and “Deserve more things in life” on a 1–7 scale (α = .715). These two items were drawn from the Psychological Entitlement Scale (see Campbell et al., 2004), and have been validated for use in the New Zealand context (Stronge et al., 2019). We included narcissism as a covariate because past research reveals it is an important predictor of one's acknowledgement of age‐related declines in healthy functioning (Draper et al., 2010) and, thus, could be an important predictor of attitudes towards euthanasia. All covariates, except ethnic group status and gender, were assessed at Time 6.

Analytic approach

To formally investigate our hypotheses, we estimated a mediated path model in Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Specifically, we simultaneously regressed support for traumatic abortion, elective abortion and euthanasia onto endorsement of the moral foundations (Harm, Fairness, Authority, Loyalty and Purity) and conservatism, as well as our control variables. We also regressed endorsement of the five moral foundations onto conservatism and our covariates. The entire model was then estimated using full information maximum likelihood and 95% bias‐corrected (BC) confidence intervals.

Follow‐up analyses were conducted to assess whether the associations between conservatism and the moral foundations, as well as resultant abortion/euthanasia attitudes, differed between gender or ethnic groups. Gender and minority/majority ethnic group status were included as moderators of the relationships conservatism had with each of the moral foundations, as well as the relationship between the binding moral foundations (of Authority, Loyalty and Purity) and attitudes towards abortion/euthanasia. All relevant interaction effects were non‐significant. This suggests that political endorsement of the moral foundations and their subsequent impacts on abortion/euthanasia attitudes did not differ across gender or ethnic groups.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for, as well as the bivariate correlations between, our variables of interest. Before testing our hypotheses, we examined potential differences in our variables included in Time 3.5 (i.e., our covariates and moral foundation measures) as a function of attrition (see Table 2). These analyses revealed that participants who completed both Times 3.5 and 6 were slightly older (p < .001) and more likely to belong to an ethnic majority group (p < .001) than were those who withdrew from the study between waves. Conversely, the latter group endorsed the moral foundation of purity/sanctity more strongly than did the former group (p = .016). There was no evidence that any of the remaining variables significantly varied across our sample and the participants who withdrew from the study. For more information on the demographic predictors of sample attrition, see Satherley et al. (2015).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for variables of interest

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender a | 0.36 | 0.48 | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 48.19 | 15.23 | .196 *** | — | ||||||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity b | 0.15 | 0.36 | −.064 *** | −.260 *** | — | |||||||||||

| 4. Conservatism | 3.42 | 1.34 | .074 *** | .177 *** | −.011 | — | ||||||||||

| 5. Religious Affiliation c | 0.39 | 0.49 | −.028 | .104 *** | .129 *** | .236 *** | — | |||||||||

| 6. Narcissism | 2.56 | 1.22 | .095 *** | −.202 *** | −.125 *** | .059 *** | .006 | — | ||||||||

| 7. Harm/Care | 5.52 | 0.84 | −.248 *** | .053 ** | .042 * | −.024 | .107 *** | −.044 * | — | |||||||

| 8. Fairness/Equality | 5.23 | 0.76 | −.073 *** | .146 *** | .027 | −.099 *** | .038 * | −.038 * | .524 *** | — | ||||||

| 9. In‐group/Loyalty | 4.23 | 0.99 | .064 *** | .254 *** | .031 | .300 *** | .183 *** | .067 *** | .316 *** | .287 *** | — | |||||

| 10. Respect/Authority | 4.52 | 1.06 | .080 *** | .263 *** | .022 | .465 *** | .225 *** | .070 *** | .190 *** | .151 *** | .613 *** | — | ||||

| 11. Purity/Sanctity | 3.89 | 1.36 | .007 | .286 *** | .039 * | .486 *** | .417 *** | .037 * | .252 *** | .187 *** | .545 *** | .657 *** | — | |||

| 12. Abortion support (elective) | 5.12 | 1.84 | −.062 ** | −.174 *** | −.037 * | −.389 *** | −.397 *** | .025 | −.048 ** | −.001 | −.223 *** | −.303 *** | −.325 *** | — | ||

| 13. Abortion support (traumatic) | 6.41 | 1.14 | −.021 | −.009 | −.091 *** | −.273 *** | −.287 *** | −.035 * | .003 | .037 * | −.126 *** | −.191 *** | −.348 *** | .533 *** | — | |

| 14. Euthanasia support | 5.61 | 1.81 | −.023 | −.097 *** | −.077 *** | .230 *** | −.370 *** | .030 | −.060 *** | .007 | −.152 *** | −.135 *** | −.509 *** | .484 *** | .422 *** | — |

Gender was dummy‐coded (0 = female, 1 = male).

Ethnicity was dummy‐coded (0 = NZ Euro/Pakeha, 1 = ethnic minority).

Religious affiliation was dummy‐coded (0 = no, 1 = yes).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Demographic summary of participants who were in the study compared to those who withdrew at Time 6

| In study | Withdrew | Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | t | p | |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Age | 48.19 | 15.23 | 45.21 | 16.54 | 5.72*** | 10.49 | <.001 |

| Gender | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 1.17 | .241 |

| Minority status | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.45 | −0.13*** | −9.39 | <.001 |

| Moral foundations | |||||||

| Harm/Care | 5.52 | 0.84 | 5.56 | 0.85 | −0.04 | −1.31 | .192 |

| Fairness/Equality | 5.23 | 0.76 | 5.25 | 0.81 | −0.02 | −0.84 | .403 |

| In‐group/Loyalty | 4.23 | 0.99 | 4.30 | 1.05 | −0.07 | −1.87 | .062 |

| Respect/Authority | 4.52 | 1.06 | 4.58 | 1.09 | −0.05 | −1.34 | .280 |

| Purity/Sanctity | 3.89 | 1.36 | 4.02 | 1.37 | −0.13* | −2.41 | .016 |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Because the political left often takes more progressive stances on social issues than do the political right (e.g., see Osborne & Sibley, 2015), we predicted that conservatism would correlate negatively with support for both types of abortion and euthanasia. These associations should, however, be mediated by the moral foundations. Given that both abortion and euthanasia could be seen by some as a violation of the “natural” order (Jelen, 2014), we hypothesized that the moral foundation of sanctity/purity would correlate negatively with support for both traumatic and elective abortion, as well as euthanasia. We also predicted that purity would (partially) mediate the negative relationship between conservatism and support for both forms of abortion, as well as (partially) mediate the negative relationship between conservatism and euthanasia.

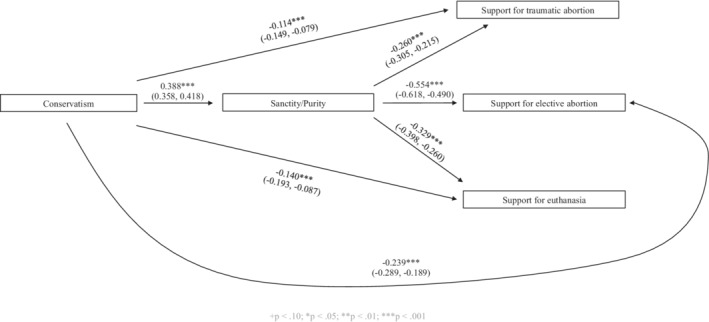

Results revealed that our model provided a good fit to these data, χ 2 (11) = 517.634, p < .001; comparative fit index = .948; root mean square error = .117 (.109, .126; p < .001); standardized root mean square residual = .060 (see Figure 1). In order to demonstrate that our results held after accounting for our covariates, we opted to proceed with the current model (rather than performing post hoc modifications to improve model fit, which often capitalises on chance fluctuations within a given sample; see MacCallum et al., 1992). Assessment of our covariates revealed that, as expected, religious affiliation was significantly negatively correlated with support for both traumatic (B = −0.370, 95% BC [−0.449, −0.291], p < .001) and elective (B = −0.794, 95% BC [−0.920, −0.669], p < .001) abortion, as well as euthanasia (B = −0.985, 95% BC [−1.120, −0.850], p < .001). Contrary to expectations, narcissism was positively associated with support for both elective abortion (B = 0.072, 95% BC [0.026, 0.118], p = .002) and euthanasia (B = 0.067, 95% BC [0.018, 0.116], p = .007). Furthermore, the Respect/Authority moral foundation was positively associated with support for both traumatic (B = 0.066, 95% BC [0.011, 0.121], p = .018) and elective (B = 0.119, 95% BC [0.039, 0.198], p = .003) abortion, as well as euthanasia (B = 0.283, 95% BC [0.198, 0.368], p < .001; see Table 3).

Figure 1.

Path model showing the path from conservatism to support for abortion (both traumatic and elective) and euthanasia (paths reflect unstandardised regression coefficients). Pathway(s) illustrate the hypothesised negative indirect effect of conservatism on support for abortion (both traumatic and elective) and euthanasia through increased endorsement of the Sanctity/Purity moral foundation. Results control for the other moral foundations, as well as demographic covariates.

TABLE 3.

Summary of regression analyses for variables predicting attitudes towards abortion (elective and traumatic) and euthanasia (N = 3360)

| Traumatic abortion | Elective abortion | Euthanasia | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | p | B | SE | 95% CI | p | B | SE | 95% CI | p | |

| Specific direct effects | ||||||||||||

| Demographic covariates | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.052 | .039 | (.129, .025) | .182 | −.190** | .059 | (−.306, −.075) | .001 | −.144* | .064 | (−.269, −.018) | .025 |

| Age | .006*** | .001 | (.003, .008) | <.001 | −.004* | .002 | (−.008, .000) | .048 | −.002 | .002 | (−.006, .002) | .243 |

| Ethnicity | −.133* | .062 | (−.254, −.011) | .032 | −.042 | .082 | (−.203, .120) | .613 | −.233* | .094 | (−.417, −.048) | .013 |

| Religious Affiliation | −.370*** | .040 | (−.449, −.291) | <.001 | −.794*** | .064 | (−.920, −.669) | <.001 | −.985*** | .069 | (−1.12, −.850) | <.001 |

| Narcissism | .006 | .016 | (−.026, .039) | .697 | .072** | .023 | (.026, .118) | .002 | .067** | .025 | (.018, .116) | .007 |

| Predictors | ||||||||||||

| Conservatism | −.114*** | .018 | (−.149, −.079) | <.001 | −.239*** | .026 | (−.289, −.189) | <.001 | −.140*** | .027 | (−.193, −.087) | <.001 |

| Harm/Care | .074* | .029 | (.018, .130) | .010 | .053 | .042 | (−.028, .135) | .200 | −.052 | .044 | (−.139, .035) | .240 |

| Fairness/Equality | .051 | .032 | (−.012, .114) | .114 | .094 | .045 | (.005, .183) | .039 | .137** | .048 | (.043, .232) | .004 |

| In‐group/Loyalty | .040 | .031 | (−.020, .100) | .187 | .074 | .039 | (−.003, .151) | .061 | −.074 | .043 | (−.158, .011) | .086 |

| Respect/Authority | .066* | .028 | (.011, .121) | .018 | .119** | .041 | (.039, .198) | .003 | .283*** | .043 | (.198, .368) | <.001 |

| Purity/Sanctity | −.260*** | .023 | (−.305, −.215) | <.001 | −.554*** | .033 | (−.618, −.490) | <.001 | −.329*** | .035 | (−.398, −.260) | <.001 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||||||

| Harm/Care | −.002 | .001 | (−.004, .000) | .078 | −.002 | .001 | (−.004, −.001) | .252 | .001 | .001 | (−.001, .004) | .286 |

| Fairness/Equality | −.004 | .003 | (−.009, .001) | .123 | −.007* | .004 | (−.014, .000) | .048 | −.010** | .004 | (−.018, −.003) | .008 |

| In‐group/Loyalty | .007 | .005 | (−.003, .017) | .190 | .013 | .007 | (−.001, .026) | .063 | −.013 | .008 | (−.028, .002) | .090 |

| Respect/Authority | .021* | .009 | (.004, .039) | .019 | .038** | .013 | (.012, .063) | .004 | .090*** | .014 | (.062, .118) | <.001 |

| Purity/Sanctity | −.101*** | .010 | (−.120, −.082) | <.001 | −.215*** | .015 | (−.245, −.185) | <.001 | −.128*** | .015 | (−.156, −.099) | <.001 |

| Model summary | ||||||||||||

| R 2 | .184 | .344 | .197 | |||||||||

Note: CI, confidence interval.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

After adjusting for our relevant covariates including the other four moral foundations, the results displayed in Table 3 reveal that Purity/Sanctity correlated negatively with support for both traumatic abortion (B = −0.260, 95% BC [−0.305, −0.215], p < .001) and elective abortion (B = −0.554, 95% BC [−0.618, −0.490], p < .001), as well as support for euthanasia (B = −0.329, 95% BC [−0.398, −0.260], p < .001). Conservatism also correlated negatively with support for traumatic abortion (B = −0.114, 95% BC [−0.149, −0.079], p < .001), elective abortion (B = −0.239, 95% BC [−0.289, −0.189], p < .001), and euthanasia (B = −0.140, 95% BC [−0.193, −0.087], p < .001). Conversely, conservatism correlated positively with Purity/Sanctity (B = 0.388, 95% BC [0.358, 0.418], p < .001). Once again, these associations emerged after controlling for relevant covariates.

Table 3 displays the indirect relationships between conservatism and our outcome variables through each of the moral foundations. As hypothesised, Purity/Sanctity partially mediated the negative relationship between conservatism and support for traumatic abortion (B = −0.101, 95% BC [−0.120, −0.082], p < .001). The negative relationship between conservatism and support for elective abortion was also partially mediated by Purity/Sanctity (B = −0.215, 95% BC [−0.245, −0.185], p < .001). Finally, the negative relationship between conservatism and support for euthanasia was partially mediated by Purity/Sanctity (B = −0.128, 95% BC [−0.156, −0.099], p < .001; see Figure 1).

Table 3 also displays the specific indirect effects of conservatism onto our three outcome variables through the remaining four moral foundations. As shown here, conservatism had a positive indirect effect on support for traumatic abortion (B = 0.021, 95% BC [0.004, 0.039], p = .019) through the moral foundation of Respect/Authority, as well as indirect effects on support for elective abortion via both Respect/Authority (B = 0.038, 95% BC [0.012, 0.063], p = .004) and Fairness/Equality (B = −0.007, 95% BC [−0.014, 0.000], p = .048). Conservatism also had indirect effects on support for euthanasia via the moral foundations of Respect/Authority (B = 0.090, 95% BC [0.062, 0.118], p < .001) and Fairness/Equality (B = −0.01, 95% BC [−0.018, −0.003], p = .008). None of the remaining moral foundations mediated the relationship between conservatism and support for these three issues.

DISCUSSION

Abortion and euthanasia are highly contested issues within the political landscape and are frequently moralised within popular discourse. Past research reveals that such divisions largely sit along ideological lines (Dillon, 1996; Hout, 1999), with conservatives expressing opposition to both abortion and euthanasia, while liberals often support such issues (Abramowitz, 1995). Our research examined the possibility that distinct moral foundations explain these ideological differences in attitudes, particularly focusing on the role of Purity/Sanctity. As hypothesised, Purity/Sanctity mediated the relationship between conservatism and opposition to both types of abortion and euthanasia (even after accounting for demographic covariates and the other four moral foundations).

Despite rhetoric which often positions conservative opposition to these moral issues as rooted in harm‐based concerns and the desire to protect the unborn (Beckwith, 2001), our results demonstrate that only Sanctity/Purity concerns (partially) mediated the relationships between conservatism and opposition to all three social issues. Although Respect/Authority and Fairness/Equality also inconsistently mediated these associations, Sanctity/Purity was by far the largest specific indirect effect through which conservatism correlated with these issues. This is consistent with past work showing that anti‐abortion/euthanasia rhetoric often does not reflect the underlying rationale of care‐based moral concern (MacInnis et al., 2014; Rottman et al., 2014). Instead, as Deak and Saroglou (2015) note, conservatives' opposition to abortion and euthanasia appear to be driven by the binding moral foundations, mainly Purity/Sanctity.

Deak and Saroglou (2015) argue that conservative opposition is largely motivated by non‐interpersonal principilistic deontology, and this rigid conception of morality seems to share conceptual overlap with that of the Purity/Sanctity moral foundation. In other words, abortion and euthanasia are not seen as violations of prosocial concerns (such as Harm or Fairness), nor even group or social‐functioning concerns (such as Authority or Loyalty). Rather, conservative opposition may reside in the view that these issues violate fundamental principles related to the sanctity of life and the natural order (Kelley et al., 1993). Notably, our model explained a significant proportion of the variance in predicting attitudes towards elective abortion (R 2 = .344), particularly when compared to traumatic abortion (R 2 = .184). Moreover, the relationship between Purity and elective abortion was over twice the size of the corresponding relationship between Purity and traumatic abortion (i.e., bs = −0.554 and − 0.260, respectively). Nevertheless, Purity consistently (partially) mediated the relationships conservatism had with attitudes towards all three issues. In other words, the endorsement of Purity/Sanctity concerns by conservatives helps to explain some of the ideological divisions in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia.

That Purity/Sanctity concerns predicted opposition to these moral issues helps explain the partisan attitudes expressed by both liberals and conservatives. Past work demonstrates that attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia have grown increasingly polarised over the years (Hout, 1999) and is a salient issue to voters when making electoral choices (Adams, 1997). That Purity/Sanctity concerns drive political attitudes towards abortion/euthanasia suggests that such issue positions are rooted in people's moral and value systems, or moral intuitions (Haidt & Graham, 2007). Indeed, analysis of the abortion discourse shows that the abortion debate is largely argued dogmatically and upon polarised lines (Dillon, 1993). Hence, whether attitudes towards abortion or euthanasia can shift over time may largely depend on the values held by the general population, particularly with respect to their endorsement of the moral foundation of Purity/Sanctity.

Another possibility is that increasing political polarisation in New Zealand may partially explain the strong relationships between Purity/Sanctity and opposition towards abortion and euthanasia. Past work has suggested that political rhetoric may help the public connect their moral intuitions to specific policy issues and positions (see Clifford et al., 2015), with such rhetoric increasing as the issue becomes more polarised (Clifford & Jerit, 2013). Although these trends have been noted in other countries, evidence for increasing levels of political polarisation in New Zealand is limited (Satherley et al., 2020). As such, polarisation is unlikely to play a strong role in shaping the results observed in the current study.

Beyond our focal predictions, we note that, somewhat unusually, Respect/Authority correlates positively (rather than negatively) with endorsement of euthanasia and, to a lesser degree, elective abortion. Indeed, examination of the indirect relationships revealed that Respect/Authority partially mediated the negative relationships between conservatism and support for both elective abortion and euthanasia, albeit in a direction opposite to that of Purity. This is particularly surprising, as the idealisation of authority plays a powerful role in conservative ideology (Eckhardt, 1991) and obedience to traditional authorities is one of the most powerful predictors of conservatism. That Respect/Authority has an opposing impact on support for abortion and euthanasia in our sample may speak to something unique about the political context of New Zealand.

One potential explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that New Zealanders' assessment of the Respect/Authority moral domain was centred on the fulfilment of one's social role (Graham & Haidt, 2010). Past research indicates that older New Zealanders' support for euthanasia was primarily driven by a fear of “feeling like a burden” (Young et al., 2019), as well as a desire to preserve one's dignity. These concepts may partly capture the moral importance of fulfilling one's role‐based duties, even to one's own detriment (Graham & Haidt, 2010). Regardless, future research may wish to further investigate how conservatives and liberals interpret the moral foundations within the context of abortion and euthanasia.

Although more work needs to be done to examine how liberals and conservatives conceptualise the moral parameters of the debate on abortion and euthanasia, our results can help inform public opinion and advocacy groups. Specifically, our work suggests that, despite popular rhetoric, conservative opposition to abortion and euthanasia is rooted in concerns over the purity of one's body and soul, not care‐based moral concern for those involved. Most importantly, our work also demonstrates that the moral foundation of authority can actually increase conservative support for euthanasia and abortion—at least within the New Zealand context. As such, our work may identify important nuanced ways to change citizens' views towards these issues. For example, past work has found that reframing a political topic to be consistent with a group's moral values can increase citizens' support for the issue (see Feinberg & Willer, 2013, 2019; Kalla et al., 2022). Approaches to changing public perception of abortion and euthanasia might thus begin by addressing Purity concerns, as well as appealing to authority figures.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

Our work investigated the role of moral foundations in explaining the ideological differences in attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. As hypothesised, conservatives were more likely to oppose abortion and euthanasia. Moreover, this relationship was partially mediated by the endorsement of Purity/Sanctity. Because we utilised a nation‐wide random sample of adults, our results are generalisable to the wider New Zealand population. Thus, ideological differences in opposition to abortion/euthanasia are partly explained by a desire to maintain one's purity and, assumedly, the perception that abortion and euthanasia violate “natural” laws (Jelen, 2014) – namely, the sanctity of life.

Despite the strengths of our study, there are a few limitations to note. Firstly, the cross‐sectional and non‐experimental nature of the study means our conclusions must be considered carefully. While we show that Purity/Sanctity (partially) mediates the negative relationship between conservatism and support for abortion and euthanasia, the causal direction of this relationship cannot be established. Indeed, past work has argued that moral intuitions may sit at the heart of political ideology (Graham et al., 2011), thus motivating attitudes and behaviour. Future work will have to examine how political ideologies shape moral thinking, and vice‐versa, to establish the causal direction of this relationship.

Secondly, our assessment of conservatism, as well as attitudes towards all three social issues, were limited to single‐item measures. Our items are thus unable to explore potential nuances in the endorsement of abortion and euthanasia. For example, support for abortion—even under traumatic conditions—varies by the scenarios surrounding the decision (e.g., cases of rape or incest vs. the mother does not want another child; see Osborne et al., 2022). Indeed, some conservative politicians even advocate for exceptions to blanket restrictions. These different circumstances may increase the salience of the other moral foundations, thus attenuating or enhancing the impact of political attitudes on abortion.

Similarly, attitudes towards euthanasia may depend on the context or illness. Indeed, due to improvements in palliative care, reasons for euthanasia are now largely focused on psycho‐emotional factors such as “feeling like a burden” (Chochinov, 2006). However, our item specifically asked about someone who has a “painful and incurable disease.” Thus, it is possible that the moral foundations which underlie attitudes towards euthanasia when the issue is focused on pain may differ from when the issue is focused on a feeling of “a loss of dignity,” or “being a burden.” Additionally, with the enactment of the End of Life Choice Act in New Zealand, attitudes towards euthanasia may be further influenced by specific guidelines and safety measures for euthanasia.

As noted above, reframing a political issue in a way that appeals to the binding moral foundations can lead conservatives to adopt more traditionally “liberal” positions (Feinberg & Willer, 2019). This persuasion hypothesis thus suggests that framing the issue may impact how participants connect the topic to their moral foundations and influence their support accordingly. Combining these insights, our research indicates that the Purity/Sanctity moral foundation is particularly important when examining these specific issues of abortion and euthanasia. Future research may wish to examine these nuances in more depth to identify the circumstances under which other moral foundations may influence attitudes towards these sensitive ethical issues, or how the framing of these issues influences how participants connect them to their moral concerns.

While we controlled for religious affiliation, our examination of religion only encompassed those who identified with a religious or spiritual group. The breadth of this question may conceal other important factors influencing attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia both between religious groups, such as denominational differences, and within religious groups including religious identification. Indeed, research demonstrates that religious attitudes towards euthanasia differ both by denomination and church attendance (as a proxy of religiosity), with both Roman Catholics and more frequent attendees showing the lowest levels of support for the issue (Danyliv & O'Neill, 2015). As such, future work may wish to examine the effects of religious identification and denomination more closely to see if these variables moderate the relationship between conservatism and Purity/Sanctity, as well as the relationships Purity/Sanctity have with attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. Finally, we note that, due to the omnibus nature of our survey, some variables of interest present at Time 3.5 were not present at Time 6, limiting our ability to conduct cross‐lagged analyses.

CONCLUSION

The current study investigated the mediating role of moral foundations in the relationship between conservatism and attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. As hypothesized, results showed that Purity/Sanctity partially mediated the negative relationship between conservatism and support for both abortion and euthanasia. Hence, while conservatives may value all five moral foundations (Graham & Haidt, 2010), not all five foundations appear to influence attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. Indeed, consistent with past research, pro‐choice and end‐of‐life decisions are rooted in concerns about the sacred order. If life is sacred, ending a life, regardless of the context, is seen as a rejection of the “natural” order (Jelen, 2014) and a stain on one's spiritual purity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Performance Based Research Fund grants jointly awarded to the third and fourth authors, as well as a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust (TRT0196) awarded to the third author.

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Endnote

Elective and traumatic abortions have been given various respective labels including social and physical cases (Bahr & Marcos, 2003) and soft and hard reasons (Adebayo, 1990; Benin, 1985). Traumatic abortion has also been labelled as therapeutic abortion. We use the labels “elective” and “traumatic” abortions here because they offer an intuitive description of the diverse circumstances surrounding an abortion, and because doing so maintain consistency with our previous work in this area (e.g., see Huang et al., 2014, 2016; Osborne & Davies, 2009, 2012).

REFERENCES

- Abramowitz, A. I. (1995). It's abortion, stupid: Policy voting in the 1992 presidential election. The Journal of Politics, 57(1), 176–186. 10.2307/2960276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, A. (1990). Male attitudes toward abortion: An analysis of urban survey data. Social Indicators Research, 22(2), 213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, G. D. (1997). Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 718–737. 10.2307/2111673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, T. G. , Stewart, P. A. , & Blanchar, J. C. (2014). Disgust and the politics of sex: Exposure to a disgusting odorant increases politically conservative views on sex and decreases support for gay marriage. PLoS One, 9(5), e95572. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, S. J. , & Marcos, A. C. (2003). Cross‐Cultural Attitudes Toward Abortion: Greeks Versus Americans. Journal of Family Issues, 24(3), 402–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranzke, H. (2012). “Sanctity‐of‐life”—A bioethical principle for a right to life? Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 15(3), 295–308. 10.1007/s10677-012-9369-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M. D. , Martin, K. J. , & Melugin, P. R. (2018). Making and breaking abstinence pledges: Moral foundations and the purity movement. Sexuality & Culture, 22(1), 288–298. 10.1007/s12119-017-9467-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith, F. J. (2001). Taking abortion seriously: A philosophical critique of the new anti‐abortion rhetorical shift. Ethics & Medicine, 17(3), 155–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benin, M. H. (1985). Determinants of Opposition to Abortion: An Analysis of the Hard and Soft Scales. Sociological Perspectives, 28(2), 199–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulbulia, J. , Osborne, D. , & Sibley, C. G. (2013). Moral foundations predict religious orientations in New Zealand. PLoS One, 8(12), e80224. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer, M. , Böhnke, J. R. , & Lewis, G. J. (2017). Predicting moral sentiment towards physician‐assisted suicide: The role of religion, conservatism, authoritarianism, and big five personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 244–251. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, W. K. , Bonacci, A. M. , Shelton, J. , Exline, J. J. , & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self‐report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. 10.1207/s15327752jpa8301_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov, H. M. (2006). Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end‐of‐life care. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 56(2), 84–103. 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, S. , & Jerit, J. (2013). How words do the work of politics: Moral foundations theory and the debate over stem cell research. The Journal of Politics, 75(3), 659–671. 10.1017/S0022381613000492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, S. , Jerit, J. , Rainey, C. , & Motyl, M. (2015). Moral concerns and policy attitudes: Investigating the influence of elite rhetoric. Political Communication, 32(2), 229–248. 10.1080/10584609.2014.944320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, B. L. , Jozkowski, K. N. , Turner, R. C. , & Lo, W.‐J. (2021). Examining the relationship between Roe v. Wade knowledge and sentiment across political party and abortion identity. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 10.1007/s13178-021-00597-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J. T. , Inbar, Y. , & Maloney, V. (2014). Disgust sensitivity selectively predicts attitudes toward groups that threaten (or uphold) traditional sexual morality. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 218–223. 10.1016/j.paid.2014.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, J. P. (2022). Colombia euthanasia cases prompt regional debate. The Lancet, 399(10322), 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danyliv, A. , & O'Neill, C. (2015). Attitudes towards legalising physician provided euthanasia in Britain: The role of religion over time. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 52–56. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C. L. , Sibley, C. G. , & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of the moral foundations questionnaire. Social Psychology, 45(6), 431–436. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deak, C. , & Saroglou, V. (2015). Opposing abortion, gay adoption, euthanasia, and suicide: Compassionate openness or self‐Centered moral rigorism? Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 37(3), 267–294. 10.1163/15736121-12341309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M. (1993). Argumentative complexity of abortion discourse. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57(3), 305. 10.1086/269377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M. (1996). The American abortion debate: Culture war or normal discourse? In The American culture wars: Current contests and future prospects (pp. 115–132). University Press of Virginia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğruyol, B. , Alper, S. , & Yilmaz, O. (2019). The five‐factor model of the moral foundations theory is stable across WEIRD and non‐WEIRD cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109547. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Draper, B. , Peisah, C. , Snowdon, J. , & Brodaty, H. (2010). Early dementia diagnosis and the risk of suicide and euthanasia. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 6(1), 75–82. 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, W. (1991). Authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 12, 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, E. J. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , Urwin, J. W. , & Cohen, J. (2016). Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician‐assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA, 316(1), 79–90. 10.1001/jama.2016.8499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M. , Antonenko, O. , Willer, R. , Horberg, E. J. , & John, O. P. (2014). Gut check: Reappraisal of disgust helps explain liberal–conservative differences on issues of purity. Emotion, 14(3), 513–521. 10.1037/a0033727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M. , & Willer, R. (2013). The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(1), 56–62. 10.1177/0956797612449177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M. , & Willer, R. (2019). Moral reframing: A technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(12), e12501. 10.1111/spc3.12501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J. , & Haidt, J. (2010). Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 140–150. 10.1177/1088868309353415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J. , Nosek, B. A. , Haidt, J. , Iyer, R. , Koleva, S. , & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. 10.1037/a0021847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth, J. L. , Kellstedt, L. A. , Smidt, C. E. , & Green, J. C. (2006). Religious influences in the 2004 presidential election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 36(2), 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J. , & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannikainen, I. R. , Miller, R. M. , & Cushman, F. A. (2017). Act versus impact: Conservatives and liberals exhibit different structural emphases in moral judgment. Ratio, 30(4), 462–493. 10.1111/rati.12162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, R. , & Penney, R. K. (1992). Euthanasia and abortion: Personality correlates for the decision to terminate life. The Journal of Social Psychology, 132(1), 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout, M. (1999). Abortion politics in the United States, 1972–1994: From single issue to ideology. Gender Issues, 17(2), 3–34. 10.1007/s12147-999-0013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Davies, P. G. , Sibley, C. G. , & Osborne, D. (2016). Benevolent sexism, attitudes toward motherhood, and reproductive rights: A multi‐study longitudinal examination of abortion attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(7), 970–984. 10.1177/0146167216649607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Osborne, D. , Sibley, C. G. , & Davies, P. G. (2014). The precious vessel: Ambivalent sexism and opposition to elective and traumatic abortion. Sex Roles, 71(11), 436–449. 10.1007/s11199-014-0423-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishola, F. , Ukah, U. V. , & Nandi, A. (2021). Impact of abortion law reforms on women's health services and outcomes: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 192. 10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelen, T. G. (2014). The subjective bases of abortion attitudes: A cross national comparison of religious traditions. Politics and Religion, 7(3), 550–567. 10.1017/S1755048314000467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jelen, T. G. , & Wilcox, C. (2005). Continuity and change in attitudes toward abortion: Poland and the United States. Politics & Gender, 1(2), 297–317. 10.1017/S1743923X05050099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. A. , Hook, J. N. , Davis, D. E. , Van Tongeren, D. R. , Sandage, S. J. , & Crabtree, S. A. (2016). Moral foundation priorities reflect U.S. Christians' individual differences in religiosity. Personality and Individual Differences, 100, 56–61. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalla, J. L. , Levine, A. S. , & Broockman, D. E. (2022). Personalizing moral reframing in interpersonal conversation: A field experiment. The Journal of Politics, 84(2), 1239–1243. 10.1086/716944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, J. , Evans, M. D. R. , & Headey, B. (1993). Moral reasoning and political conflict: The abortion controversy. The British Journal of Sociology, 44(4), 589–612. 10.2307/591412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, H. , & Matsuo, A. (2021). Development and validation of the purity orientation–pollution avoidance scale: A study with Japanese sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.590595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva, S. P. , Graham, J. , Iyer, R. , Ditto, P. H. , & Haidt, J. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194. 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lineham, P. J. (2014). Trends in religious history in New Zealand: From institutional to social history. History Compass, 12(4), 333–343. 10.1111/hic3.12152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. C. , Roznowski, M. , & Necowitz, L. B. (1992). Model modifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychological Bulletin, 111(3), 490–504. 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis, C. C. , MacLean, M. H. , & Hodson, G. (2014). Does “humanization” of the preborn explain why conservatives (vs. liberals) oppose abortion? Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 77–82. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. P. , Albaugh, M. , Farber, E. , Daniels, J. , Logan, R. L. , & Olson, B. (2008). Family metaphors and moral intuitions: How conservatives and liberals narrate their lives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 978–990. 10.1037/a0012650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T. L. L. , Davies, C. L. , & Wilson, M. S. (2019). The moral foundations of environmentalism: Care‐ and fairness‐based morality interact with political liberalism to predict pro‐environmental actions. Social Psychological Bulletin, 14(2), 1–25. 10.32872/spb.v14i2.32633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millar, E. , & Baird, B. (2021). Abortion is no longer a crime in Australia. But legal hurdles to access remain. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/abortion‐is‐no‐longer‐a‐crime‐in‐australia‐but‐legal‐hurdles‐to‐access‐remain‐156215

- Mooijman, M. , Meindl, P. , Oyserman, D. , Monterosso, J. , Dehghani, M. , Doris, J. M. , & Graham, J. (2018). Resisting temptation for the good of the group: Binding moral values and the moralization of self‐control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(3), 585–599. 10.1037/pspp0000149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton, B. E. , Hill, T. D. , & Burdette, A. (2006). Religion and trends in euthanasia attitudes among U.S. adults, 1977–2004. Sociological Forum, 21(2), 249–272. 10.1007/s11206-006-9015-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz, S. , Dierickx, S. , Deliens, L. , Cohen, J. , & Chambaere, K. (2021). Assisted dying around the world: A status quaestionis. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(3), 3540–3553. 10.21037/apm-20-637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, D. , & Davies, P. G. (2012). When benevolence backfires: Benevolent sexists' opposition to elective and traumatic abortion. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(2), 291–307. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00890.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, D. , Huang, Y. , Overall, N. C. , Sutton, R. M. , Petterson, A. , Douglas, K. M. , Davies, P. G. , & Sibley, C. G. (2022). Abortion attitudes: An overview of demographic and ideological differences. Political Psychology. 10.1111/pops.12803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, D. , & Davies, P. G. (2009). Social dominance orientation, ambivalent sexism, and abortion: Explaining pro‐choice and pro‐life attitudes. In L. B. Palcroft & M. V. Lopez (Eds.), Personality assessment: New research (pp. 309–320). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, D. , & Sibley, C. G. (2015). Within the limits of civic training: Education moderates the relationship between openness and political attitudes. Political Psychology, 36(3), 295–313. 10.1111/pops.12070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patev, A. J. , Hall, C. J. , Dunn, C. E. , Bell, A. D. , Owens, B. D. , & Hood, K. B. (2019). Hostile sexism and right‐wing authoritarianism as mediators of the relationship between sexual disgust and abortion stigmatizing attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109528. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarossa, L. (2019). “Women are not in the best position to make these decisions by themselves”: Gender stereotypes in the Uruguayan abortion law. University of Oxford Human Rights Hub Journal, 2019, 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, N. , Johnson, M. H. , & Malpas, P. J. (2015). New Zealanders' attitudes toward physician‐assisted dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(3), 259–265. 10.1089/jpm.2014.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottman, J. , Kelemen, D. , & Young, L. (2014). Tainting the soul: Purity concerns predict moral judgments of suicide. Cognition, 130(2), 217–226. 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabriseilabi, S. , & Williams, J. (2022). Dimensions of religion and attitudes toward euthanasia. Death Studies, 46(5), 1149–1156. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1800863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satherley, N. , Greaves, L. M. , Osborne, D. , & Sibley, C. G. (2020). State of the nation: Trends in New Zealand voters' polarisation from 2009–2018. Political Science, 72(1), 1–23. 10.1080/00323187.2020.1818587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satherley, N. , Milojev, P. , Greaves, L. M. , Huang, Y. , Osborne, D. , Bulbulia, J. , & Sibley, C. G. (2015). Demographic and psychological predictors of panel attrition: Evidence from the New Zealand attitudes and values study. PLoS One, 10(3), e0121950. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, J. R. (2020). Binding morality and perceived harm as sources of moral regulation law support among political and religious conservatives. Law & Society Review, 54(3), 680–719. 10.1111/lasr.12487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, J. R. , Pickett, J. T. , Barnes, J. C. , Bontrager, S. R. , & Roe‐Sepowitz, D. E. (2022). Why Men (Don't) Buy Sex: Purity Moralization and Perceived Harm as Constraints on Prostitution Offending. Sexual Abuse, 34(2), 180–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skitka, L. J. , Wisneski, D. C. , & Brandt, M. J. (2018). Attitude moralization: Probably not intuitive or rooted in perceptions of harm. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 9–13. 10.1177/0963721417727861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solano, G. (2022). Ecuador approves measure regulating abortion for rape cases. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/ecuador‐approves‐measure‐regulating‐abortion‐rape‐cases‐82963720

- Stronge, S. , Cichocka, A. , & Sibley, C. G. (2019). The heterogeneity of self‐regard: A latent transition analysis of self‐esteem and psychological entitlement. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 103855. 10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, J. (2019). Northern Ireland has been forced to change its abortion law—Here's how it happened. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/northern‐ireland‐has‐been‐forced‐to‐change‐its‐abortion‐law‐heres‐how‐it‐happened‐125256

- Turner‐Zwinkels, F. M. , Johnson, B. B. , Sibley, C. G. , & Brandt, M. J. (2021). Conservatives' moral foundations are more densely connected than liberals' moral foundations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(2), 167–184. 10.1177/0146167220916070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F. , & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F. , Dukes, A. , Tybur, J. M. , & Park, J. H. (2017). Disgust sensitivity relates to moral foundations independent of political ideology. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11(1), 92–98. 10.1037/ebs0000075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C. R. , & Federico, C. M. (2013). Moral foundations and heterogeneity in ideological preferences. Political Psychology, 34(1), 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, C. (1992). Race, religion, region and abortion attitudes. Sociological Analysis, 53(1), 97. 10.2307/3711632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrum, E. , & Davison, B. L. (1992). Reexamination of religious influences on abortion attitudes. Review of Religious Research, 33(3), 229–243. 10.2307/3511088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, O. , Harma, M. , Bahçekapili, H. G. , & Cesur, S. (2016). Validation of the moral foundations questionnaire in Turkey and its relation to cultural schemas of individualism and collectivism. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 149–154. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. , Egan, R. , Walker, S. , Graham‐DeMello, A. , & Jackson, C. (2019). The euthanasia debate: Synthesising the evidence on New Zealander's attitudes. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 14(1), 1–21. 10.1080/1177083X.2018.1532915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]