Abstract

Purpose

Although research has explored burnout risk factors among medical trainees, there has been little exploration of the personal experiences and perceptions of this phenomenon. Similarly, there has been little theoretical consideration of trainee wellbeing and how this relates to burnout. Our study aimed to conceptualise both constructs.

Method

We situated this study within a post‐positivist epistemology using grounded theory to guide the research process. Participants were recruited from one Australian General Practice training organisation. Fourteen trainees completed interviews, while a further five focus groups explored the views of 33 supervisors, educators and training coordinators. Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently, drawing upon constant comparison and triangulation. Template analysis, using an iterative process of coding, was employed to generate conceptual models of the phenomena of interest.

Results

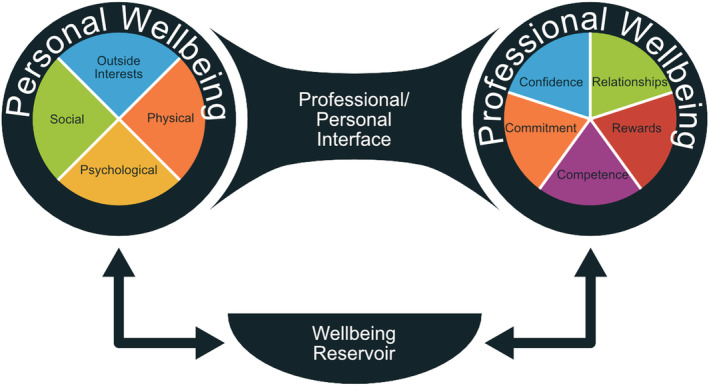

Participants described burnout as an insidious syndrome lying on a spectrum, with descriptions coalescing under seven themes: altered emotion, compromised performance, disengagement, dissatisfaction, exhaustion, overexertion and feeling overwhelmed. Wellbeing was perceived to comprise personal and professional domains that interacted and were fuelled by an underlying ‘reservoir’. Both constructs were linked by the degree of a trainee's value fulfilment, with burnout occurring when a trainee's wellbeing reservoir was depleted.

Conclusions

Participants in this study characterised burnout and wellbeing as multifaceted, connected constructs. Given the complexity of these constructs, preventive interventions should target both person and workplace‐focused factors, with value fulfilment proposed as the basic change mechanism. A novel model that synthesises and advances previous research is offered based on these findings.

Short abstract

Prentice et al. propose a novel model of burnout and wellbeing amongst General Practice trainees that is underpinned by trainees' value fulfilment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Burnout is associated with substantial personal, professional and societal costs. 1 , 2 , 3 Despite much literature documenting risk factors alongside interventions for postgraduate medical trainees, 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 burnout among this group remains a major concern. 9 We contend that a core contributor to this situation is conceptual confusion regarding burnout, characterised by untested assumptions and a lack of construct clarity. 10 , 11 , 12

The Leiter and Maslach 13 , 14 model, via the Maslach Burnout Inventory, has dominated this predominantly quantitative literature. 9 , 17 However, we are unaware of any theoretical justification for the superiority of this model in a medical context over the plethora of alternatives (e.g. Farber, 18 , 19 Manzano‐García and Ayala‐Calvo 20 and Shirom, 21 among others 22 , 23 , 24 ). Indeed, current models of burnout may inadequately capture trainees' experiences. 25 , 26 This occurs in a broader research effort to re‐examine burnout as a phenomenon. 23 , 27 , 28 This knowledge gap, in combination with evidence that burnout may have contextually influenced presentations (e.g. as per different versions the Maslach Burnout Inventory 15 , 29 ), 30 , 31 , 32 suggests a need for medicine‐specific investigation of what burnout is. This research will help to determine which, if any, model is most applicable.

To date, only five studies have qualitatively examined burnout experiences in trainees. Two qualitative studies provided a brief account of relevant symptoms (e.g. self‐doubt, disengagement, exhaustion and relationship deterioration). 33 , 34 A further three studies engaged in a more in‐depth examination among family medicine 26 , 35 and emergency medicine trainees. 36 However, none of these studies offer an overarching model of how burnout develops. Moreover, only one study has triangulated trainees' experiences with other data sources (e.g. faculty and supervisors). 36 Such triangulation may provide insight into external burnout manifestations, complementing trainees' experiences and perceptions.

Conceptual confusion in this area is compounded by minimal exploration of trainees' wellbeing. 11 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 Some factors (e.g. workload and work–family conflict) appear to show mixed relationships with trainee burnout and wellbeing. 42 , 43 It follows that just as disease prevention and health promotion are distinct, a sole focus on burnout prevention is insufficient to promote wellbeing. 10 , 44 Accordingly, we need to clearly define ‘wellbeing’ to understand how to promote it. In doing so, making reference to burnout will be crucial to understand similarities and differences in intervention design and intent.

Explorations of burnout and wellbeing must also be sensitive to observed specialty differences in burnout symptom patterns, particularly since these may affect interventional responses. 45 For example, whereas reduced motivation and self‐worth were common to emergency medicine and family medicine trainees, cynicism and physical exhaustion were not shared. 35 , 36 These data were supported by a recent meta‐analysis, which noted considerably different symptom profiles based on trainees' specialty. 9 To understand the phenomena, initial explorations of both constructs should therefore be confined to a single specialty.

We sought to use a post‐positivist paradigm to qualitatively explore burnout and wellbeing to determine whether pre‐existing models adequately capture trainee experiences and perceptions. We also aimed to understand how these constructs relate to one another. We confined the scope of this study to General Practice (GP) training owing to the importance of specialty differences and the availability of a recent review on this topic. 38 Additionally, the prevalence of burnout within this group means trainees would likely have either experienced burnout or known a colleague who had. 46 , 47 Our research questions were:

What does burnout mean for general practice trainees?

What does wellbeing mean for general practice trainees?

2. METHODS

The present article adheres to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines. 48 The University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for this study (H‐2019‐072).

2.1. Rationale

Our motivation for this study originated with a systematic review of burnout estimates among postgraduate medical trainees. From this review, we learnt that there is considerable heterogeneity in how burnout is operationalised. 9 Even among studies that utilised the Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey and its derivates (including the Medical Personnel version), 16 we identified 25 unique definitions of burnout ‘caseness’ across 182 studies. These findings mirror those of Rotenstein et al, 17 leading us to question how burnout should be best operationalised. In further exploring the above literature, we came to pose our research questions.

To this end, we felt grounded theory offered a comprehensive means for inductively generating a theoretical account of these psychological phenomena. 49 We executed this within a post‐positivist stance, in keeping with the methodology's original position, as our objective was to generate a model (or models) that could be somewhat transferable beyond the context of this study. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Under this stance, we accepted a critical realist perspective that ‘burnout’ and ‘wellbeing’ are states that exist, but that our ability as researchers to understand their true nature is impeded by human subjectivity and interpretation. 53 , 54

2.2. Context

We completed this study in the Australian GP training setting. In Australia, following the completion of a medical degree, medical trainees complete a year as an intern in a hospital rotating through different specialties. Following this, trainees have the option to apply to complete specialist training. Trainees accepted into the Australian GP training programme (known as GP registrars) can complete their training with one of two colleges: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) or the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM). At the time of writing, this training is delivered by 10 training organisations with whom most trainees train, although alternative options are available (e.g. independent pathways). For most of GP training, registrars must complete training placements under the supervision of an accredited supervisor. These placements are served for at least one 6‐month period (called a ‘term’), with the option to extend the placement for a further term. Training typically occurs over three training terms. To complete GP training and become a qualified GP, registrars must complete the Australian GP training programme requirements and pass a series of examinations set by the College with whom the registrar is training.

2.3. Procedures

We recruited participants from a single training organisation to maximise our contextual understanding. We believed this would not overly distort the sample given that registrars spend most of their time working within practices rather than interfacing with the training organisation. This meant there was already a substantial degree of variability in participants' experiences. Data collection comprised two forms that occurred concurrently: interviews with registrars and focus groups with other stakeholder groups. We spoke with various stakeholders to provide ‘self’ and ‘other’ reports. This allowed us to triangulate these reports. 54 Furthermore, we postulated that comparing internal and external perceptions of the phenomena may be informative for burnout monitoring efforts. Due to the sensitivity of the topic, we chose to use interviews with registrars to promote open and truthful discussion and disclosure of these experiences. We used focus groups with other stakeholders, as this involved discussing registrars in general, rather than their personal experiences. The focus groups also provided opportunity to build upon each other's experiences and observations. 55

Registrars were eligible to participate if they were in their second term or later, as we sought the viewpoints of trainees who could reflect on their experiences in GP. Given the stigma associated with burnout, 56 , 57 we anticipated that requiring prospective participants to self‐identify as experiencing burnout could dissuade many from participating in our study. As the training organisation supported this study, registrars may have also perceived risks regarding their training status. We did not want to skew the sample by only speaking to those who were open about their personal experiences, thereby distorting the representation of the phenomena of interest. Accordingly, personal experience of burnout was not an eligibility criterion. All eligible registrars were emailed an invitation to participate in a 1‐h, semi‐structured interview examining their understanding of burnout and wellbeing. Participating registrars were reimbursed in accordance with RACGP guidelines.

Invitation emails were also sent to supervisors, training coordinators (hereafter ‘coordinators’) and medical educators (hereafter ‘educators’) to participate in separate focus groups. Supervisors are qualified GPs who typically work in the same practice as a registrar and teach, assess and oversee registrars' medical practice. Coordinators are training organisation staff who offer administrative support in guiding registrars through the training program. Educators are qualified GPs involved in the education and assessment of registrars. Separate focus groups for supervisors, coordinators and educators were held during training organisation‐paid working time; participants were not otherwise compensated.

All email invitations included participant information sheets detailing the study's purpose; requirements, risks and benefits of participating; withdrawal options; data management and usage processes; and contact details for the researchers and Human Research Ethics Committee. At the beginning of each interview and focus group, we reminded participants of the study's purpose and gave them an opportunity to ask questions. We also assured participants of the confidentiality of their interview or focus group.

We continued sampling among all groups until all individuals who had expressed interest in participating had participated, were no longer interested or could not be contacted. We pursued this recruitment strategy given the personal significance of the subject matter. Although there has been recent debate about the merits of saturation, 58 , 59 from a post‐positivist perspective, we emphasised the data's comprehensiveness. We defined saturation as when no new themes or codes emerged from the data. 60 We also evaluated participant characteristics (i.e. stakeholder groups, gender, stage of training and geographic location) to ensure that diverse perspectives were sought.

The same question schedule was used in all interviews and focus groups (see Appendix B). However, SP adjusted prompts as data collection progressed to reflect issues emerging from preliminary data analysis. Given interviews and focus groups occurred concurrently, these data interacted at the collection stage. Questions focused on understanding stakeholders' perceptions of burnout and wellbeing, where possible exploring observations or—where volunteered—participants' personal experiences. SP conducted all interviews and focus groups, either face‐to‐face or via Zoom, from August to November 2019. Although SP held pre‐existing professional relationships with some participants, he did not hold a position of power in these relationships and found the pre‐existing rapport facilitated, rather than impeded, the data collection. Where participants consented, we audio‐recorded interviews and focus groups. Only SP had access to these recordings; he transcribed them verbatim, reviewed them for accuracy and removed identifying information (e.g. locations and names). For participants who did not consent to be audio‐recorded, we used the interviewer's notes in place of a transcript. SP labelled transcripts with the participant type (coordinator, educator, registrar, supervisor), data collection method (interview, focus group) and chronological number. We then imported transcripts into NVivo Qualitative Software V12 for Windows (QSR, International), noting demographic details as case attributes.

2.4. Analysis

Each transcript represented a single unit of analysis, with interview and focus group transcripts analysed within the one coding framework. SP began analysis by immersing himself in each interview/focus group as part of the transcribing process, identifying general themes emerging from each. 50 Once we finalised data collection, he selected an initial transcript informed by this preliminary analysis that was broadly representative of the themes to commence analysis. Both analysts (SP and TE) analysed this transcript separately to permit investigator triangulation.

Both analysts had a background in psychology and medical education research and were affiliated with the training organisation where recruitment occurred. This provided us with a rich contextual understanding, enhancing our ability to understand participants' experiences. We were also conscious that these backgrounds may have impeded the analysts' openness to the data, risking ‘forcing’ themes from the data. 50 To raise our awareness of the contribution of these perspectives, we employed two strategies. First, DD—who is not affiliated with the training organisation—reviewed all findings to provide an alternative perspective. Second, SP and TE met repeatedly during analysis to compare their coding approaches, offering a forum to explore the differences in how and why content was coded. 61 Similarly, SP had a greater awareness of the burnout theory literature than TE, so coding comparisons allowed us to explore where SP's theoretical knowledge may have shaped his approach to analysis.

Procedurally, we analysed the data using template analysis 62 by using the research questions as categories to organise the development of codes. We coded the data with NVivo to highlight segments of transcripts and store these in codes. After analysing each transcript, the analyst reviewed the coding structure to identify themes emerging from the codes. Analysts kept an audit trail within NVivo, recording their decisions regarding coding structure development. Once SP and TE had analysed the first transcript, they fused their coding structures in a consensus meeting. SP then applied and extended this coding structure to the remaining transcripts, reviewed the coding structure for consistency and, to identify overarching themes, then re‐coded all transcripts using this revised structure. In this second round of coding, SP paid particular attention to evidence within the data of relationships between themes (i.e. axial coding). Once we finalised analysis, SP ran a series of matrix queries in NVivo to compare the presence of each theme across different stakeholder groups, permitting triangulation between data sources.

From a post‐positivist perspective, we were also interested in the coding structures' robustness. We therefore undertook two rounds of inter‐coder agreement coding. Each round involved TE coding a new transcript and a consensus meeting between SP and TE to discuss disagreements and make a final decision. Inter‐coder agreement, calculated as the number of agreements divided by the sum of the number of agreements and disagreements, 63 reached 95%. We elected simple percentage agreement as the 40 generated codes reduced the likelihood of chance agreement. Additionally, being an exploratory study, we did not specify a coding unit (e.g. sentence and paragraph) to optimise the relevance of content stored within a code, thereby preventing quantification of instances of ‘agreeing to exclude’ content (see Campbell et al 64 ). Once the coding process was finalised, we presented it to DD to review the findings' coherence. No changes were made to the coding from this.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics

Forty‐seven individuals participated in the study: 14 registrars completed interviews, while 15 educators, 13 supervisors and five coordinators participated in five focus groups. One interview was not audio‐recorded. Participants' characteristics are reported in Table 1. The high proportion of female coordinators and registrars in the sample reflects the gender composition of both groups. 65 Illustrative quotes for the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix C. Areas of variation in themes across groups are noted in the below sections and detailed in Appendix C.

TABLE 1.

Participants' characteristics

| Training term (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group (N) | No. interviews/focus groups | Female (%) | Urban (%) | Term 2 | Term 3 | Term 4 or Extended/Advanced Skills post |

| Registrars (14) | 14 | 10 (71.4%) | 8 (57.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (28.6%) | 5 (35.7%) |

| Educators (15) | 1 | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | NA | ||

| Training Coordinators (5) | 2 | 5 (100%) | NA | NA | ||

| Supervisors (13) | 2 | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | NA | ||

TABLE 2.

Illustrative quotes of themes regarding burnout in general practice registrars

| Category | Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of burnout | Altered emotion | ‘It could be anywhere on a broad spectrum of depression‐anxiety, could be at either end of that spectrum, which is affecting all the things in his life, not only work, but everything’ (Supervisor) |

| ‘… getting curt or more snappy and seeing that with patients or seeing that with other doctors or the reception staff …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Compromised performance | ‘… it probably would start impacting on their performance at work … both in terms of efficiency and time management, but also in their ability to sort of interact with patients in a helpful way, probably more likely to make mistakes’ (Registrar) | |

| Disengagement | ‘Or withdrawn, they do not say anything – if they are normally engaging and then they change their behaviour to not saying anything at all’ (Educator) | |

| ‘[they are] just doing the bare minimum and … just trying to get through day‐by‐day rather than actually … focussing on the patient’ (Registrar) | ||

| Dissatisfaction | ‘I think we all do the job because we enjoy it and if you lose that enjoyment of the job, that sort of makes it hard to function’ (Supervisor) | |

| “… not enjoying the job and probably not enjoying things outside of work either …” (Registrar) | ||

| ‘… maybe more complaining like again about … like patients … maybe trivialising their presentations or their concerns …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Exhaustion | ‘I guess you can obviously get the … physical fatigue from not sleeping enough … but then I think there's emotional fatigue … feeling I guess just emotionally drained … I guess it's hard to kind of describe how that presents but … I think just feeling tired from the number of patients that you are seeing and just like decisions you are making can cause mental or emotional fatigue …’ (Registrar) | |

| Overexertion | ‘someone trying to work harder, overworking …’ (Training Coordinator) | |

| Overwhelmed | ‘Struggling to keep up with the program, their training … submitting assessments, attendance at workshops’ (Educator) | |

| ‘… they are feeling like they are working too much and not able to have any time spare … even if they enjoy work, but they just still have not got time to do anything other than work, so they do not have time for their family or their hobbies and they just … get to the point where they cannot cope really, all gets too much’ (Training Coordinator) | ||

| ‘… so I think in the milder spectrum I think you can still employ a lot of coping strategies, whereas the more severe you get … those sort of coping strategies fail you a bit’ (Registrar) | ||

| Qualities of burnout | Spectrum | ‘… like everyone's at least a little burnt out most of the time and … by the end of the day we are a little bit different than what we were in the morning. I [do not] think it's like on Wednesday … you were not burnt out and then … the day after, [you are] all of a sudden … burnt out again, … it's not binary like that, it's definitely a transition and a deterioration’ (Registrar) |

| Insidious | ‘I think it's an acute stress state and it, once it starts, you see it in all aspects of their life, not just work, you see it in the way they talk to the lady at the post office …’ (Supervisor) | |

| Relationship to physical health | ‘it might be affecting their appetite, either … not eating [because] of … poor appetite, or overeating, … not exercising’ (Registrar) | |

| Individual differences | ‘… it's comparative to the registrar, because the amount of noise between Registrar A and Registrar B is going to be at least as big as the way that Registrar A … approaches a problem when they are doing well versus … when they are getting frustrated and burnt out …’ (Registrar) |

TABLE 3.

Illustrative quotes of themes regarding wellbeing in general practice registrars

| Category | Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Personal domain | Physical health | ‘… I think … getting enough sleep …’ (Registrar) |

| ‘… things like exercise … maintaining your physical health …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Psychological wellbeing | ‘that positive tone when they ring you and they are cracking jokes, they laugh if you make a joke …’ (Training Coordinator) | |

| ‘… sees [the] future as something bright and hopeful and is able to look at achieving goals …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Social wellbeing | ‘… who has people that they catch up with outside of work and has that sense of network and connection to other people …’ (Registrar) | |

| Outside interests | ‘… you can maintain relationships and hobbies and enjoyment outside of your work and actually have the time to do that’ (Registrar) | |

| ‘I think it is invaluable and makes for better registrars if you have got a little bit else going on apart from study and work’ (Registrar) | ||

| Professional domain | Competence | ‘… they will be attending to their professional … requirements … regularly without … a lot of … complaints …’ (Registrar) |

| ‘… there's a … general sense that they are coping with work, so you know they are not sort of there long hours after patients tidying up notes … they are not making mistakes at work …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Confidence | “… having confidence in their job and that they are doing a good job …” (Registrar) | |

| ‘… knowing that you do not know everything … and not being afraid or feeling stupid to ask for help …’ (Registrar) | ||

| Rewards | “the wellbeing aspect for me is like just seeing someone really enjoying what they are doing and then talking to them about it and they say “yeah, it's really been great”’ (Educator) | |

| ‘… you can very much get a sense that they are enjoying what they are doing and quite like the patients’ (Supervisor) | ||

| Relational engagement | ‘… the way they interact with us is a huge indicator of their wellbeing … the people that seem to cope best are the people that are a bit more proactive in communicating with us’ (Training Coordinator) | |

| ‘… actually talking to colleagues and interacting for ideas and things like that’ (Registrar) | ||

| Commitment | ‘… that's a good sign if they do that, spending …, at the end of the day or in their lunch break or somehow they are making this phone call to protect a child who's … at risk of being harmed’ (Supervisor) | |

| Wellbeing reservoir | ‘I think they would be sort of enthusiastically and positively talking about things that they are doing and directions that they are going that aren't necessarily work related, you know, like talking about their kite‐boarding trip that's coming up or … excitedly discussing this, that or the other thing that's happening in their lives’ (Registrar) | |

| Personal‐professional interface | ‘… the question's about … fulfilment … or balance I guess, it's like … figuring out what fulfilment your job gets you and what types of fulfilment you need to get from other sources … you have to sort of get some diversity to meet all of your psychological and emotional needs, figuring out what your job gets you and then figuring out how many hours you need to remain fulfilled … to get your like essential nutrients from other sources … that's what I sort of think it would be’ (Registrar) | |

| ‘Medicine is incredibly rewarding, but it can also be emotionally draining and if you do not have good things going outside of your work, you can become drained quite quickly’ (Registrar) |

3.2. What is burnout?

3.2.1. Symptoms

When asked to describe burnout, participants' responses coalesced under seven themes (see Figure 1). Notably, the registrar and supervisor datasets both raised each of the seven themes. Coordinators and educators, who have less involvement with registrars, reported fewer themes.

FIGURE 1.

The seven dimensions of burnout among Australian General Practice registrars [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Altered emotion

Participants often noted that registrars experiencing burnout displayed emotional changes. These emotions ranged from ‘… getting more curt or snappy …’ and anger to anxiety and crying, but also depressive symptoms and flat affect.

Compromised performance

Participants believed that registrars experiencing burnout would display impaired professional performance. Suggested manifestations included inefficiency, such as consistently running late for appointments; reduced quality of care, including medical mistakes; missing deadlines (particularly for educational assessments); and acting inappropriately or unprofessionally.

Disengagement

Participants in every interview and focus group believed burnout would involve the registrar experiencing ‘… disinterest in their work …’ and learning. Manifestations fell under three subthemes: avoidance behaviours (i.e. avoiding work or withdrawing from professional relationships), mechanisation (i.e. investing minimal effort, displaying reduced enthusiasm and being unreceptive to new ideas or feedback); and non‐adherence (i.e. not meeting practice or training organisation requirements—including absence, tardiness and non‐compliance with educational assessments).

Dissatisfaction

Participants believed burnout also entailed a sense of dissatisfaction with work and training. This could manifest as complaining, pessimism, a loss of perceived meaningfulness and doubting one's career choice.

Exhaustion

Participants regularly raised the concept of exhaustion. Although this could manifest emotionally (i.e. emotional depletion and reduced empathy), it could also be mental (e.g. reduced initiative) or physical (i.e. fatigue).

Feeling overwhelmed

All groups suggested that registrars would constantly feel time‐pressured and overworked. This could prompt registrars to adopt maladaptive coping strategies (e.g. alcohol, binge‐watching and fast food). Additional manifestations of feeling overwhelmed were explored through the subthemes of ‘pruning’—where registrars reduced outside activities (e.g. hobbies and self‐care) to increase time to dedicate to work and study—and a reduced sense of self‐efficacy or feelings of powerlessness, alongside decreased confidence and resilience. Interestingly, although ‘feeling overwhelmed’ did not emerge within each registrar interview, it was universally raised within the other datasets, suggesting that this feeling may be more apparent to others than registrars themselves.

Overexertion

A rarely discussed symptom was registrars physically and mentally pushing themselves to the limit to meet work demands. This could involve working longer hours or reduced sleep. Participants suggested this was more likely to manifest at an early stage of burnout.

3.2.2. Characteristics of burnout

Burnout was unanimously described as lying on a spectrum. Participants believed that, as burnout exacerbated, symptoms would become more visible and there would be increased complaints and concerned feedback from others. However, they also perceived that the more severe burnout became, the less willing registrars were to admit experiencing it. Furthermore, whereas some of the above themes (i.e. dissatisfaction and compromised performance) indicated severe burnout, other symptoms could be present from the start and exacerbate. For example, where exhaustion could initially manifest as reduced empathy, this would morph into emotional depletion as registrars' burnout intensified.

There was contention about the relationship between registrars' insight and burnout severity. Some argued that insight would increase because of the heightened visibility of their burnout, whereas others maintained that greater exhaustion would impede insight. Another disagreement concerned the directionality of spill‐over for burnout severity. While some thought burnout symptoms would initially manifest in registrars' professional life and then emerge into their personal life as the syndrome worsened, others believed the opposite would occur.

Participants noted that whether a symptom constituted ‘burnout’ required understanding of the situational and individual contexts, especially the registrar's baseline level of functioning. For example, while not engaging with others could be concerning, participants commented that this could be ‘normal’ for highly introverted registrars. Likewise, disengagement and dissatisfaction could stem from a registrar wanting to change their career rather indicating burnout.

Participants also explored presentation differences, including the belief that rural and urban registrars displayed similar burnout symptoms. However, some suggested that the smaller communities in rural areas reduced registrars' ability to mask their symptoms, making burnout more visible. There were mixed views regarding presentation differences between junior and senior registrars: Some perceived similar experiences across groups, whereas others suggested that burnout among senior registrars may be more severe and potentially worsen over time. Many also suggested differences in the nature of the symptoms, with junior registrars' being overwhelmed, whereas senior registrars' were more disengaged and exhausted.

3.3. What is wellbeing?

Although two participants remarked that they had never encountered a ‘well’ registrar, the consensus was that registrars' wellbeing involved an interaction between personal and professional domains fuelled by an underlying ‘wellbeing reservoir’ (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

A conceptual model of wellbeing among Australian General Practice registrars [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.1. Personal wellbeing

Registrars' personal domain was explored through four themes. The first concerned physical wellbeing or health. This was largely discussed in terms of fitness, although some also commented on diet and sleep. The second theme was psychological or emotional wellbeing. This included an awareness of one's general wellbeing and a capacity for empathy, as well as experiencing positive emotions. The third theme related to the need for strong social networks with friends and family. The final theme related to outside interests such as hobbies; participants believed these were necessary to achieve fulfilment.

3.3.2. Professional wellbeing

The dominant of the five themes identified here concerned the level of relational engagement with colleagues, including practice staff, peers and training organisation staff. One educator furthered this, suggesting that prosocial behaviours (e.g. trying to help their peers) were an important sign of wellbeing. The second theme involved professional competence, or the quality and efficiency of one's work. The third related theme, highlighted only by registers, concerned a sense of self‐confidence to practise. This confidence allowed them to acknowledge their own vulnerability and helped them to seek support when needed. However, some cautioned that excessive confidence could be dangerous for the registrar and their patients. A further theme of professional wellbeing involved deriving rewards or satisfaction from one's job. The final theme concerned registrars' commitment to their job, including a commitment to provide high‐quality care and going ‘above and beyond’ to meet patients' individual needs.

3.3.3. Interactions between personal and professional domains

Registrars' state of wellbeing was described in terms of their personal and professional interactions, both of which were connected through a wellbeing ‘reservoir’. This reservoir held the physical and emotional energy that registrars consumed to engage in their daily activities. Engaging in activities that fulfilled one's values and goals helped to fuel this energy reserve. A further element, the ‘personal‐professional interface’, was perceived as a critical conduit linking the demands and fulfilment across registrars' personal and professional lives. Inter‐related subthemes of fulfilment and replenishment were also identified. Registrars were seen as having individual values and goals that could be fulfilled through engaging in personal and/or professional activities. The nature and relative importance of these values and goals varied between individuals due to (1) the specific manifestations of different wellbeing facets (e.g. what constituted a ‘rewarding’ job); (2) each facet's relative importance; and (3) how values and goals could be fulfilled. The combination of these factors produced a unique profile that determined a registrar's optimal ratio (or ‘work/life balance’).

3.4. How do burnout and wellbeing relate?

Participants' descriptions of burnout and wellbeing highlighted that the two phenomena were linked by the interactions between registrars' personal and professional domains. Specifically, when a particular value is unfulfilled, an individual's reservoir will begin to drain faster than it can be refuelled. One registrar noted an example of an under‐resourced healthcare system preventing registrars from adequately caring for their patients. Such a situation compromises registrars' ability to meet their personal and professional demands, creating a vicious cycle. This scenario can also be triggered when the ratio between personal and professional roles and responsibilities is unsustainable, resulting in one domain dominating the other. In both instances, burnout results.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Key findings

In this study, we explored conceptualisations of burnout and wellbeing in Australian GP registrars. Burnout was viewed as a multidimensional syndrome (see Figure 1) thought to occur when a registrar's values and/or goals were no longer met, thereby depleting the wellbeing reservoir. In this way, the personal‐professional ratio was viewed as critical – an unsustainable ratio, where one domain dominated the other to the point that certain values and/or goals could no longer be met, would result in burnout. Individual–organisational value tension has been previously implicated in burnout development. 66 , 67 However, we provide an overarching explanatory model that encompasses well‐established processes, such as the absence of sufficient resources, 68 , 69 as well as proposing that unfulfilment of an individuals' professional and personal values and/or goals is the central process by which burnout develops. This conceptualisation shows modest overlap with Pines' 70 existential model, which posits that burnout arises from a sense of existential meaninglessness. However, Pines 70 did not specifically discuss the role of values: a novel aspect of our model.

Table 4 outlines a comparison of the symptoms raised in our study and those in previous general population and medical education research. While none of our dimensions are new, some are broader than previous articulations (e.g. overwhelmed and dissatisfaction). This is particularly true when examining the medical education literature (e.g. ‘relationship deterioration’ and ‘Feeling like an outsider’ subsumed by ‘disengagement’). 26 , 33 Moreover, no previous research has raised all of our dimensions. In conjunction with our proposal of burnout development, these findings suggest that existing measures of burnout may not fully capture the experience of trainees.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of dimensions of burnout identified in present study with other burnout models

| Dimension | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Altered emotion | Compromised performance | Disengagement | Dissatisfaction | Exhaustion | Overexertion | Overwhelmed |

| General population literature | |||||||

| Cherniss 22 | Reduced work goals, reduced personal responsibility for outcomes, less idealism | Emotional detachment | |||||

| Leiter and Maslach 13 , 14 , 28 | Depersonalisation | Low personal accomplishment | Depersonalisation, ‘disengaged’ profile | Emotional exhaustion | ‘Overextended’ profile, Low personal accomplishment | ||

| Montero‐Marín, García‐Campayo 19 | Underchallenged subtype |

Underchallenged subtype Worn‐out subtype |

Underchallenged subtype | Frenetic subtype | Worn‐out subtype | ||

| Shirom 21 | Physical fatigue, emotional exhaustion, cognitive weariness | ||||||

| Tavella and Parker 23 | Anxiety/stress, depression, irritability and anger, emotional lability | Executive functioning issues, reduced performance | Indifference, lack of motivation or passion, withdrawal from others | Depression, lack of motivation or passion | Exhaustion | Anxiety/stress | |

| Medical education literature a | |||||||

| Harsh, Lawrence 33 | Relationship deterioration, depression | Disengagement, depression, relationship deterioration | Depression | Relationship deterioration | Self‐doubt | ||

| Jain, Tabatabai 36 | Emotional fragility, reduced self‐worth | Personal negativity, impaired social skills, apathy | Cynicism | Apathy | Self‐neglect | ||

| Odom, Romain 26 , b | Personal depletion, being overwhelmed | Personal depletion, feeling like an outsider | Personal depletion | Physical exhaustion, personal depletion | Self‐neglect | Basic needs deficiency, self‐neglect, being overwhelmed | |

| Petek, Gajsek 34 , b | Mood swings, irritability, inability to quickly calm, low stress tolerance | Poor concentration, mistakes at work | Lack of motivation, apathy | Exhaustion, chronic fatigue, insomnia, illness susceptibility | |||

| Rutherford and Oda 35 , b | Lack of motivation at work, isolation from family and friends | Moral distress | Physical exhaustion, emotional exhaustion | ||||

Note that, although no specific models of burnout were proposed within the studies listed under ‘Medical education literature’, here we compare the burnout symptoms presented in these articles with the dimensions identified in this study.

Denotes studies conducted with family medicine or general practice trainees.

When specifically compared with other medical education research, Table 4 shows that many of these symptoms have been identified with family medicine or GP trainees and trainees from other specialties. However, ‘compromised performance’ has only been raised in one other GP sample. 34 This may be associated with the lower supervision afforded in GP compared with other specialty training. 71 , 72 , 73

The notion that burnout is not defined by the presence of all identified dimensions, with different groups flagging different symptoms, has implications for its assessment. 23 , 24 Stakeholders that we interviewed reinforced the influence of context, especially registrars' typical behaviour, when determining whether burnout symptoms should be concerning – a critical aspect of any mental health assessment. 74 Our findings therefore support a nuanced approach to conceptualising burnout. Practically, this suggests that interventions may need to be tailored to the symptomatic presentation of burnout among trainees. This is akin to the assessment and intervention of other formally recognised mood disorders, where symptom variability is a feature. 75

Wellbeing was also conceptualised as a multi‐dimensional construct, involving personal and professional domains that interact to fuel an underlying ‘wellbeing reservoir’ (see Figure 2). By engaging in meaningful activities within each domain, the reservoir is sustained, although unfulfilment of values will lead to the reservoir's depletion, resulting in burnout. The structure of our wellbeing model shows strong similarities with a model previously synthesised from the literature, 38 although incorporating important extensions (i.e. outside interests, commitment and wellbeing reservoir). There are also similarities with the theme of ‘personal depletion’ raised by Odom et al. 26 This overlap supports the validity and transferability of our proposed wellbeing model in other GP or family medicine training settings.

Our model extends current wellbeing models (e.g. Dunn et al 76 ) to provide a more nuanced concept of how a personal‐professional imbalance can result in burnout and potentially harm registrars' wellbeing. For example, one can use the model to understand why the adjustment from hospital settings to GP is a stressor 77 , 78 : adjusting to the breadth of this specialty threatens registrars' professional confidence and competence, which then compromises their values (e.g. achievement and caring). 79 Our proposed model can therefore be used to identify the underlying mechanisms and stressors that threaten registrars' wellbeing and consequently potential intervention targets.

We contend that burnout and wellbeing are linked by the continuum of a trainee's value fulfilment. Interventions addressing burnout and/or wellbeing should therefore focus on value fulfilment as the basic change mechanism. Interventions targeting higher‐level burnout causes (e.g. low autonomy) without providing strategies to build trainees' awareness of, and capacity to fulfil, their values (i.e. how is promoting autonomy supporting trainees' value fulfilment) may be less effective at addressing both burnout and wellbeing. A clear example for achieving this at an individual level comes from acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a mindfulness‐based behavioural therapy that identifies values as a core element of wellbeing. 80 ACT protocols for non‐clinical contexts, such as the workplace, may support this. 81 As burnout and wellbeing involve a complex, multifactorial web of causes, 2 , 6 , 82 , 83 organisational‐level interventions must also be utilised. Such interventions can focus on removing system barriers that interfere with, and provide support for, trainees' capacity to fulfil their values (e.g. promoting flexibility and work–life integration). 3

Individualised and contextualised interventions are also important. The multidimensional nature of burnout suggests a need to explore how an individual's characteristics (e.g. personality) interact with their personal and professional contexts to produce their symptom presentation. Likewise, individualistic and organisational interventions to promote wellbeing need to be cognisant of the constituents of personal and professional wellbeing. For instance, an organisation may provide employee assistance programmes to support trainees' wellbeing but offer little support for building collegial relationships.

4.2. Limitations

Our findings must be considered with several limitations in mind. First, participants were sourced from a single training organisation. Efforts to compare our findings with the views and experiences of stakeholders in other geographical, cultural and specialty contexts will be invaluable to establish the transferability of our findings between groups. 9 Second, the theoretical claims made from these findings require further exploration. One priority will be exploring the relationship between burnout and value fulfilment. Similarly, although burnout ‘dimensions’ were proposed, the relationships between these are unclear. Future correlational and longitudinal quantitative research that operationalises these constructs will help to test the models. Finally, participants were not required to have personally experienced burnout. Although some at least implied having experienced this, the stigma associated with burnout means we cannot be sure which participants had experienced some degree of burnout. 56 , 57 The extent to which these findings are informed by lived experience is therefore unclear.

4.3. Conclusion

This research supports the notion that burnout in GP registrars is a multidimensional construct that lies on a spectrum, with acknowledgement that burnout may present differently across individuals and contexts. We have also extended previous conceptualisations of wellbeing to offer a comprehensive burnout–wellbeing model. Strategies to prevent and reduce burnout in this group should focus on maximising the fulfilment of registrars' values and goals. This will require combined efforts from registrars and broader system‐wide changes across their work practices, supervisors and training organisations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shaun Prentice: Conceptualisation (equal); investigation (lead); formal analysis (lead); visualisation (lead); writing—original draft preparation (lead); writing—review and editing (equal). Taryn Elliott: Conceptualisation (equal); formal analysis (supporting); writing—review and editing (equal). Diana Dorstyn: Conceptualisation (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Jill Benson: Conceptualisation (equal); writing—review and editing (equal).

Supporting information

Appendix A: Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines (O'Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014) checklist

Appendix B: Interview and focus group schedule

Appendix C: Table of illustrative quotes

Appendix D: Distribution of themes by participant roles

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researchers would like to thank all those who participated in the interviews and focus groups in this study. They would also like to thank GPEx for their funding to support this study. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Prentice S, Elliott T, Dorstyn D, Benson J. Burnout, wellbeing and how they relate: A qualitative study in general practice trainees. Med Educ. 2023;57(3):243‐255. doi: 10.1111/medu.14931

Funding information Funding for registrars' honoraria was provided from GPEx Ltd. Supervisors were given the opportunity to participate during a paid workshop. Employees of GPEx were permitted to participate during GPEx paid working hours. The first author was the recipient of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship while completing this study

Funding information Australian Government; GPEx Ltd

REFERENCES

- 1. Hall LH, Johnson J, Heyhoe J, Watt I, Anderson K, O'Connor DB. Exploring the impact of primary care physician burnout and well‐being on patient care: a focus group study. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(4):e278‐e283. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132‐149. doi: 10.1111/medu.12927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well‐being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129‐146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou AY, Panagioti M, Esmail A, Agius R, Van Tongeren M, Bower P. Factors associated with burnout and stress in trainee physicians: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013761. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carrieri D, Mattick K, Pearson M, et al. Optimising strategies to address mental ill‐health in doctors and medical students: ‘care under pressure’ realist review and implementation guidance. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01532-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brigham T, Barden C, Dopp AL, et al. A journey to construct an all‐encompassing conceptual model of factors affecting clinician well‐being and resilience. In: NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272‐2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47‐54. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0197-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prentice S, Dorstyn D, Benson J, Elliott T. Burnout levels and patterns in postgraduate medical trainees – a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1444‐1454. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eckleberry‐Hunt J, Van Dyke A, Lick D, Tucciarone J. Changing the conversation from burnout to wellness: physician well‐being in residency training programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):225‐230. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00026.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bynum WE, Varpio L, Teunissen P. Why impaired wellness may be inevitable in medicine, and why that may not be a bad thing. Med Educ. 2021;55(1):16‐22. doi: 10.1111/medu.14284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sibeoni J, Bellon‐Champel L, Mousty A, Manolios E, Verneuil L, Revah‐Levy A. Physicians' perspectives about burnout: a systematic review and metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1578‐1590. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05062-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout in health professions: A social psychological analysis. In: Sanders G, Suls J, eds. Social Psychology of Health & Illness. Erlbaum; 1982:227‐247. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leiter MP. The dream denied: professional burnout and the constraints of human service organizations. Canadian Psychology. 1991;32(4):547‐555. doi: 10.1037/h0079040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. 4th ed. USA: Mind Garden; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. MBI: The Maslach burnout inventory manual. 4th ed. Menlo Park, CA, Mind Garden; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. Jama. 2018;320(11):1131‐1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farber BA. Introduction: A critical perspective on burnout. In: Farber BA, ed. Stress and Burnout in the Human Service Professions. Pergamon Press; 1983:1‐20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Montero‐Marín J, García‐Campayo J, Mosquera Mera D, López del Hoyo Y. A new definition of burnout syndrome based on Farber's proposal. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2009;4(1):31. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-4-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manzano‐García G, Ayala‐Calvo J‐C. New perspectives: towards an integration of the concept “burnout” and its explanatory models. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology. 2013;29:800‐809. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shirom A. Burnout in work organisations. In: Cooper CL, Robertson I, eds. International Review of Industrial and Organisational Psychology. Wiley; 1989:25‐48. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cherniss C. Staff burnout: Job Stress in the Human Services. Sage Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tavella G, Parker G. A qualitative reexamination of the key features of burnout. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(6):452‐458. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blostein S, Eldridge W, Kilty K, Richardson V. A multi‐dimensional analysis of the concept of burnout. Employee Assistance Quarterly. 1985;1(2):55‐66. doi: 10.1300/J022v01n02_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeCross AJ. How to approach burnout among gastroenterology fellows. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):32‐35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Odom A, Romain A, Phillips J. Using photovoice to explore family medicine residents' burnout experiences and resiliency strategies. Fam Med. 2022;54(4):277‐284. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.985247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Montero‐Marín J, Prado‐Abril J, Demarzo MMP, García‐Toro M, García‐Campayo J. Burnout subtypes and their clinical implications: a theoretical proposal for specific therapeutic approaches. Revista de Psicopatologia Y Psicologia Clinica. 2016;21(3):231‐242. doi: 10.5944/rppc.vol.21.num.3.2016.15686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: a new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burn Res. 2016;3(4):89‐100. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maslach C, Leiter MP, Schaufeli W. Measuring burnout. In: Cartwright S, Cooper CL, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well‐Being. Oxford University Press; 2009:86‐108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211913.003.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work. 2006;38(2):218‐235. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marques L, Robinaugh DJ, LeBlanc NJ, Hinton D. Cross‐cultural variations in the prevalence and presentation of anxiety disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(2):313‐322. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clifton J, Bonnell L, Hitt J, et al. Differences in occupational burnout among primary care professionals. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2021;34(6):1203‐1211. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harsh JS, Lawrence TJ, Koran‐Scholl JB, Bonnema R. A new perspective on burnout: snapshots of the medical resident experience. Clinical Medicine Insights: Psychiatry. 2019;10:1‐6. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Petek D, Gajsek T, Petek SM. Work‐family balance by women GP specialist trainees in Slovenia: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0551-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rutherford K, Oda J. Family medicine residency training and burnout: a qualitative study. Can Med Educ J. 2014;5(1):e13‐e23. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jain A, Tabatabai R, Vo A, Riddell J. “I have nothing else to give”: a qualitative exploration of emergency medicine residents' perceptions of burnout. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(4):407‐415. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1875833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Slama EM, Batarseh L, Bryan F, et al. Wellbeing as defined by resident physicians: a qualitative study. Am Surg. 2021; 000313482110650. doi: 10.1177/00031348211065092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Prentice S, Benson J, Dorstyn D, Elliott T. Wellbeing conceptualizations in family medicine trainees: a hermeneutic review. Teach Learn Med. 2022;34(1):60‐68. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1919519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hale AJ, Ricotta DN, Freed J, Smith CC, Huang GC. Adapting Maslow's hierarchy of needs as a framework for resident wellness. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):109‐118. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1456928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raj KS. Well‐being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674‐684. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00764.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ratanawongsa N, Wright SM, Carrese JA. Well‐being in residency: a time for temporary imbalance? Med Educ. 2007;41(3):273‐280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Solms L, van Vianen AEM, Theeboom T, Koen J, de Pagter APJ, de Hoog M. Keep the fire burning: a survey study on the role of personal resources for work engagement and burnout in medical residents and specialists in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eckleberry‐Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269‐277. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938a45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Penwell‐Waines L, Greenawald M, Musick D. A professional well‐being continuum: broadening the burnout conversation. South Med J. 2018;111(10):634‐635. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brolinson M, D'Angelo K, Hommema L, Auciello S. Targeted interventions to improve resident well‐being. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;134(1):52S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000585600.36903.ca [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Davis C, Krishnasamy M, Morgan ZJ, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE. Academic achievement, professionalism, and burnout in family medicine residents. Fam Med. 2021;53(6):423‐432. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.541354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karuna C, Palmer V, Scott A, Gunn J. Prevalence of burnout among GPs: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e316‐e324. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245‐1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kennedy TJT, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):101‐108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hall H, Griffiths D, McKenna L. From Darwin to constructivism: the evolution of grounded theory. Nurse Res. 2013;20(3):17‐21. doi: 10.7748/nr2013.01.20.3.17.c9492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fox NJ. Post‐positivism. In: Given LM, ed. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Sage; 2008:659‐664. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lincoln YS, Lynham SA, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage; 2011:97‐128. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Panhwar AH, Ansari S, Shah AA. Post‐positivism: an effective paradigm for social and educational research. Int Res J Arts Humanities (IRJAH). 2017;45:253‐260. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. International J Qual Health Care. 1996;8(5):499‐504. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhou A, Money A, Bower P, van Tongeren M, Esmail A, Agius R. A qualitative study exploring the determinants, coping, and effects of stress in United Kingdom trainee doctors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(6):560‐569. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01086-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ironside K, Becker D, Chen I, et al. Resident and faculty perspectives on prevention of resident burnout: a focus group study. Perm J. 2019;23(3):185. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sebele‐Mpofu FY. Saturation controversy in qualitative research: complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Social Sci. 2020;6(1):1838706. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2020.1838706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample‐size rationales. Qual Res Sport, Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201‐216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893‐1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. O'Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:1‐13. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202‐222. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in‐depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(3):294‐320. doi: 10.1177/0049124113500475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Radloff A, Clarke L, Matthews D. Australian general practice training program: national report. Australian Council for Educational Research, 2019.

- 66. Leiter MP. A two process model of burnout and work engagement: distinct implications of demands and values. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2008;30(1 Suppl A):A52‐A58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Leiter MP, Frank E, Matheson TJ. Demands, values, and burnout: relevance for physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(12):1224‐1225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli W. The job demands‐resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(3):499‐512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hobfoll SE, Freedy JR. Conservation of resources: a general stress theory applied to burnout. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Routledge; 2017:115‐129. doi: 10.4324/9781315227979-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pines A. Burnout: an existential perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Taylor & Francis; 2017:33‐51. doi: 10.4324/9781315227979-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Martin D, Nasmith L, Takahashi SG, Harvey BJ. Exploring the experience of residents during the first six months of family medicine residency training. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(1):e22‐e36. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bugaj TJ, Valentini J, Miksch A, Schwill S. Work strain and burnout risk in postgraduate trainees in general practice: an overview. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(1):7‐16. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1675361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pedersen AF, Nørøxe KB, Vedsted P. Influence of patient multimorbidity on GP burnout: a survey and register‐based study in Danish general practice. British Journal of General Practice. 2020;70(691):e95‐e101. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X707837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marsh JK, De Los Reyes A. Explaining away disorder: the influence of context on impressions of mental health symptoms. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(2):189‐202. doi: 10.1177/2167702617709812 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐5. Washington, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. A conceptual model of medical student well‐being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44‐53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dory V, Beaulieu M‐D, Pestiaux D, et al. The development of self‐efficacy beliefs during general practice vocational training: an exploratory study. Med Teach. 2009;31(1):39‐44. doi: 10.1080/01421590802144245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Larkins SL, Spillman M, Parison J, Hays RB, Vanlint J, Veitch C. Isolation, flexibility and change in vocational training for general practice: personal and educational problems experienced by general practice registrars in Australia. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):559‐566. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schwartz S. Toward refining the theory of basic human values. In: Salzborn S, Davidov E, Reinecke J, eds. Methods, Theories, and Empirical Applications in the Social Sciences. Springer; 2012:39‐46. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-18898-0_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1‐25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Flaxman PE, Hayes SC, Bond FW, Livheim F. The Mindful and Effective Employee: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Training Manual for Improving Well‐Being and Performance. New Harbinger Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dyrbye LN, Trockel M, Frank E, et al. Development of a research agenda to identify evidence‐based strategies to improve physician wellness and reduce burnout. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):743‐744. doi: 10.7326/M16-2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. Br Med J. 2017;358:j3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Guidelines (O'Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014) checklist

Appendix B: Interview and focus group schedule

Appendix C: Table of illustrative quotes

Appendix D: Distribution of themes by participant roles