Abstract

Interprofessional collaborative practice has been shown to be an appropriate model of care for chronic disease management in primary care. However, how patients play a role in this model is relatively unknown. The aim of this constructivist grounded theory focus group study was to explore the perceptions of patient advocates regarding the role of patients in interprofessional collaborative practice for chronic conditions in primary care. Primary data were collected from patient advocates, from public and private Australian organisations and who represent patients with chronic disease in primary care, through focus groups in July–August 2020. Videoconference focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim and inductively, thematically analysed using the five‐step approach by Charmaz: (1) initial line‐by‐line coding, (2) focused coding, (3) memo writing, (4) categorisation and (5) theme and sub‐theme development. Three focus groups comprising 17 patient advocates with diverse cultural and professional backgrounds participated. Two themes and five sub‐themes relating to interprofessional collaborative practice teams were constructed from the data. In theme 1, patients ‘shifted across the spectrum of roles’ from ‘relinquishing control to the team’, ‘joining the team’ to ‘disengaging from the team’. The second theme was the need for ‘juggling roles’ by ‘integrating patient role with life roles’, and ‘learning about the patient role’. The diversity and variability of patient roles as described by patient advocates highlight the challenges of working with people with chronic conditions. The diverse patient roles described by advocates are an important finding that may better inform communication between patients and health professionals when managing chronic conditions. From the health professional perspective, identification of the role of a patient may be challenging. Therefore, future research should explore the development of a tool to assist both patients and health professionals to identify patient roles as they move across the spectrum, with the support of policy makers. This tool should aim to identify and promote patient engagement in interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care settings.

Keywords: chronic disease, intersectoral collaboration, patient care team, primary healthcare, qualitative research

What is known on this topic?

Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) involves two or more healthcare professionals working together with patients, their families, carers and communities to provide comprehensive healthcare.

Practice guidelines for managing chronic conditions recommend IPCP.

Little is known about the patient role in IPCP.

What this study adds?

Health professionals need to be aware that a patient role in IPCP exists on a spectrum (from actively driving their care to releasing control to the IPCP team), and may change over time.

Some individuals may be disengaged from IPCP care because of a negative healthcare experience or when there is disruption in their life including relocation or change from paediatric to adult care.

1. INTRODUCTION

For many countries, primary care is the first point of contact in healthcare where physical, mental and social well‐being are addressed (Department of Health, 2020). Chronic conditions are a key focus in primary care, including prevention and management (Australian Health Minister's Advisory Council, 2017). The leading causes of death globally are chronic conditions and related risk factors (Bauer et al., 2014), where ~50% of adults have a chronic condition in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019), and the USA (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2018). Chronic conditions require complex and comprehensive management, best coordinated by a team of health professionals (Harris et al., 2011). Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) is a model of care where health professionals from multiple disciplines work together with a patient, their family, and communities to deliver high‐quality healthcare (World Health Organization, 2010). The IPCP model is designed to address the quadruple aim of healthcare: (i) enhancing patient experience, (ii) improving population health, (iii) reducing healthcare costs and (iv) enhancing healthcare provider experience (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014).

The first quadruple aim of healthcare, “enhancing patient experience”, has been explored in the Australian primary care setting previously from older persons' perspectives through surveys (Saunders et al., 2019). Additionally, the patient experience of the IPCP model delivered in primary care globally has been synthesised in an integrative systematic review (Davidson et al., 2022). However, the roles that a person may have as part of IPCP in primary care are relatively unknown (Davidson et al., 2022). Previous research has shown that an enhanced patient experience (Doyle et al., 2013; Maben et al., 2012), and an improvement in role clarification (Brault et al., 2014), including that of the patient, can improve healthcare outcomes (Brault et al., 2014; Doyle et al., 2013; Maben et al., 2012), reduce healthcare costs (Brault et al., 2014; Doyle et al., 2013; Maben et al., 2012) and enhance provider experience (Brault et al., 2014; Maben et al., 2012) ‐ the remaining three healthcare aims (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014). Therefore, understanding patient experience and role in IPCP can be useful in working towards achieving the quadruple aim of healthcare.

Patient advocates are individuals who represent patients and populations at practice or policy level within the healthcare system and have a higher understanding of patient rights. Patient advocates include individuals with first‐ or second‐hand lived experience of healthcare, or experience in a social or healthcare professional role (Schwartz, 2002; Water et al., 2016). The exact role and responsibilities of a patient advocate will rightly differ in varying contexts, with the overarching aim to ensure that patient rights are respected and met (Schwartz, 2002). Patient advocates are an important group of stakeholders in healthcare as they reflect multiple insights and experiences and represent the voice of people they represent. Patient advocates have been chosen over individual patients in this study, as advocates typically have a greater understanding of the healthcare system, and a higher health literacy to understand complex concepts, such as IPCP (Health Consumers Queensland, 2017).

The use of patient advocates as a study population in healthcare research has been previously conducted to examine the accessibility of healthcare, policy reform, and to enable the voice of patients to be represented in the healthcare literature (Brickley et al., 2021; Bridges et al., 2018; Spassiani et al., 2016; Treiman et al., 2017). However, patient advocates' views of the patient experience and role in IPCP in the Australian primary care setting have not been previously explored. The views of patient advocates are useful in providing a broad understanding of the topic, which can then lead to further targeted exploration directly with patients. Therefore, this qualitative constructivist grounded theory study aimed to understand the roles, current and potential, of patients in IPCP in primary care from the perspective of patient advocates, and to develop a theoretical framework to support findings.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

The study aim was best achieved through a qualitative study design founded in a constructivist research paradigm where the views of patient advocates were based on their lived experiences (Crotty, 1998). Constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) was used to facilitate an inductive exploration of patient advocates' experiences and perceptions of patient roles in IPCP in primary care. Charmaz's method enabled induction of ideas and concepts of patient advocates to be built from the individuals' voiced lived experiences (Charmaz, 2006), whereby themes were derived from the data. This manuscript was developed using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O'Brien et al., 2014) ‐ Supplementary file 1.

Researchers held dual health professional and researcher titles. AD is a dietitian undertaking her PhD and has previous experience and training with qualitative research methods. LB is a dietitian, Professor of community health and well‐being, and primary care researcher. MM is a practising general practitioner (GP) and Professor in a tertiary medical programme. DR is a dietitian and Associate Professor of Nutrition and Dietetics. LB, MM and DR are AD's PhD supervisors. During study design conception, researchers discussed the research paradigm, and any potential influences on the study in a reflexivity meeting (Charmaz, 2006).

2.2. Participants and setting

Purposive and snowball sampling techniques (Charmaz, 2006; Robinson, 2014; Sbaraini et al., 2011), were used to recruit patient advocates from government and non‐government organisations' patient advocacy or advisory groups. Organisations were purposefully selected to include a diverse range of advocates covering different chronic conditions. In line with the recognised definition of patient advocates, advocates could be professionals such as health or other professionals, carers, and/or individuals with a chronic condition (Schwartz, 2002; Water et al., 2016), were ≥18 years of age, and English speaking. Organisations were contacted directly by the first author via email with the participant information sheet, outlining researcher and study details, inviting members to participate. Potential participants responded to recruitment emails and were screened against inclusion criteria before being invited to a focus group. Researchers did not know the participants prior to data collection.

2.3. Data collection

Focus groups were conducted and recorded via Zoom Videoconferencing (Zoom Video Communications, 2021), informed by virtual research occurring during the global pandemic (Dos Santos Marques et al., 2021), ran for 90 min, facilitated by the first author and second author. Focus groups were chosen as patient advocates were familiar with group discussions as part of their advocacy/advisory role. To facilitate equitable videoconference group discussions, focus groups were kept to a maximum of six participants (Dos Santos Marques et al., 2021), and a minimum of three focus groups was determined to provide sufficient data for theory development (Guest et al., 2017). A semi‐structured focus group guide and slideshow guided discussions (Supplementary File 2), and were developed using key literature on IPCP (Banfield et al., 2017; van Dongen et al., 2017; van Dongen et al., 2017), focus group methods (Bloor et al., 2001), and WHO Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice (World Health Organization, 2010). Focus group facilitation materials were amended based on feedback from two piloting phases: first, the guide was piloted with a patient advocate with lived experience of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Second, materials were then rehearsed with two doctoral researchers via a simulated Zoom focus group.

2.4. Data analysis

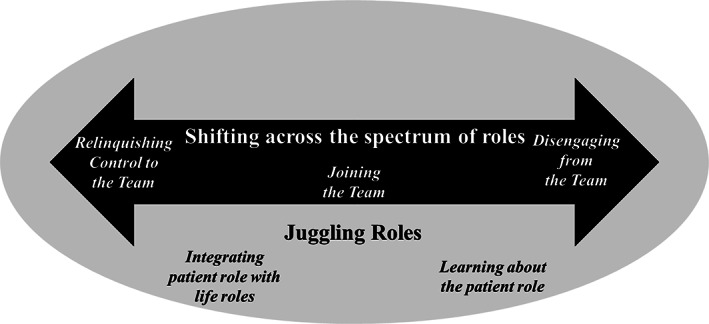

Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation) and Trello (Atlassian, 2022) were used to facilitate data analysis. Participant names and personal details were removed during transcription for anonymity. Focus group audio recordings were transcribed verbatim before undergoing a five‐step iterative thematic analysis (Charmaz, 2006): (1) Initial line‐by‐line coding: coding was closely related to the data and AD remained open to coding possibilities. (2) Focused coding: direct, selective, and conceptual codes were formed based on initial codes. (3) Memo‐writing: codes in steps 1 and 2 were reflected upon by AD to compare data. (4) Categorisation: Focused codes and memos collapsed into categories for synthesis, conducted by AD and DR. (5) Theme and sub‐theme development: categories were collapsed further to develop inductive sub‐themes and themes facilitated by research team discussions. Once results were finalised, Figure 1 was developed to represent the themes and sub‐themes as a theoretical framework (Charmaz, 2006). To enhance the trustworthiness of the results, participants were asked to provide feedback on summarised results as a form of member‐checking (Charmaz, 2006).

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework of patient roles in interprofessional collaborative practice of chronic conditions in primary care from the perspective of patient advocates. Sub‐themes are in italics.

2.5. Ethics, consent and permission

Ethical approval was obtained from the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: AD02910). Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the commencement of focus groups.

3. RESULTS

Three focus groups with seventeen patient advocates were conducted in July–August 2020, for an average of 90 minutes (87–93 minutes). Participant demographics are shown in Table 1; most were female (14/17 participants), with one male participant in each group. Patient advocates represented a broad range of cultural backgrounds including Caucasian Australian, First Nations' Australian, Asian, European, and South American. Participants represented a range of perspectives, including health and other professionals, such as interpreters, carers; and individuals with chronic conditions: mental health, cancer, diabetes, auto‐immune, kidney and cardiovascular diseases. Patient advocates had been in their advocacy role for ~2–20 years. Participants described themselves as advocates for the patient voice within their communities or organisations. It was evident that some patient advocates knew one another from various groups and organisations reflecting a sense of community.

TABLE 1.

Patient advocate focus group participant demographics

| Participant No. | Sex | Government or NGO | Advocate background (consumer, carer, health, and non‐health professionals) | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group 1 | ||||

| 1 | F | NGO | Health Professional | WA |

| 2 | F | NGO | Health Professional | NT |

| 3 | F | NGO | Non‐Health Professional | VIC |

| 4 | F | NGO | Consumer—Mental Health | QLD |

| 5 | M | NGO | Consumer—Diabetes | WA |

| 6 | F | NGO | Consumer and Health Professional | NSW |

| Focus group 2 | ||||

| 1 | F | Government | Consumer —Mental Health | QLD |

| 2 | M | NGO | Consumer and Professional—Multiple chronic conditions | QLD |

| 3 | F | NGO | Consumer—Identifies as Aboriginal (First Nations') | NSW |

| 4 | F | Government | Consumer—CALD | QLD |

| 5 | F | Government | Consumer—Mental Health | QLD |

| 6 | F | Government | Consumer and Professional—Worked with people with intellectual disabilities | QLD |

| Focus Group 3 | ||||

| 1 | F | NGO | Health Professional | NT |

| 2 | F | Government | Professional –Interpreter—CALD | QLD |

| 3 | M | NGO | Consumer and Carer | QLD |

| 4 | F | Government | Consumer and Professional—person with physical disability | QLD |

| 5 | F | NGO | Consumer and Carer—Cancer and cared for family member with cancer | VIC |

Note: Note that organisations have been de‐identified to keep participant identity confidential.

Abbreviations: CALD, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse; NGO, Non‐Government Organisation; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Figure 1 illustrates two themes and five sub‐themes. Theme 1: ‘Shifting across the spectrum of roles', represents the three key roles, presented as sub‐themes ordered left to right, that focus group participants described as roles that people may play in their care and how they may develop over time: relinquishing control to the team, joining the team, and disengaging from the team. Theme 2: ‘Juggling roles’ represents integrating the patient role with life roles, and how individuals are learning about the patient role. The double‐ended arrow embedded in the oval represents how the role as patient is embedded into the life of individuals. Very minor amendments were made to the themes and sub‐themes based on feedback provided by participants through member‐checking (Charmaz, 2006), including creating a lay summary for patients (Supplementary File 3).

3.1. Theme 1: Shifting across the spectrum of roles

Overall, patient advocates described patients as having roles in IPCP that exist on a spectrum. In their care, an individual's role as a patient continuously shifts, ebbs, and flows depending on several factors such as individual wants and needs, personality and other individual characteristics, their perspective of healthcare and health status, and changes in their condition and healthcare journey. This spectrum was conceptualised by some as a sliding scale that could shift at any time and is regularly updated. When asked, ‘what is the patient role?’, one advocate highlighted the inability to provide a definitive answer:

‘I don't think you can give a definitive answer to this question because… some patients simply don't want to know…I guess we can say what we think most of them want, or what we want, but the reality is that it's a very wide spectrum’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 6, Consumer Representative

3.1.1. Sub‐theme 1.1: Relinquishing control to the team

Patient advocates reported the role of patients as possibly passive, as has historically been the case across all healthcare settings. Despite an increasing shift towards the desirable proactive patient role, some patients remain content to relinquish control to health professionals. This passive role could be driven by fear, discomfort, or reduced confidence to be more proactive. Individual patient characteristics underpinned this role including personality, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, disability, age, socio‐economic status, health literacy, and condition, where mental health conditions were described as more vulnerable than physical. Alternatively, a patient may be content to play a passive role as they trust that their health professionals will support and instruct them:

‘They're going to leave it to the doctor, you know, the doc will tell me if I need to do anything, and they don't even want to know when there's something seriously wrong with them’. ‐ Focus Group 1 Participant 4, Mental Health Consumer Representative

Participants described that a passive patient role could be the consequence of an overly involved family and/or carer, considered a detriment in some situations. Patient advocates described concerns when the family or carer's needs and wants were prioritised over the patient's because the patient played a passive role. Advocates highlighted examples where health professionals overlooked the patient or did not invite them to express their needs and wants, instead listening to the family or carer:

‘There's a multiple range of people in the community that certainly are not involved directly in their care and have a lot of say in it, especially if there's carers or family that are representative. It's assumed, wrongly, that that's the person to talk to and not actually…listening to the needs of the patient’. ‐ Focus Group 3 Participant 4 – Consumer with Physical Disability Representative

3.1.2. Subtheme 1.2 Joining the team

Patient advocates described a centralised patient role in the IPCP team and used the concept and aspects of patient‐centred care in their descriptions. Patient advocates stated that this role should be obvious, but what was ideal to them and what happened in practice did not always align. Patient advocate quotes reflect this discrepancy. In this desired position across the spectrum of roles, patients take a role where they are:

• Partnering in healthcare

• Taking ownership of their role

• Advocating and navigating

• Involving family and carers.

Patient advocates described their preference for a care model where the patient is a partner in care. They expressed how patients need to work with the team and be on the same page, including providing input and feedback to health professionals, for an effective partnership. This partnership also includes the patient being willing to consent to health professionals working together and with them to achieve best healthcare outcomes. Patient advocates were hopeful that this integral role was implemented, indicating a possible discrepancy to what occurs in practice:

‘We hope they would be a partner and they're an integral part of the team care (laughing), that's what you would be hoping for’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 1, Health Professional Representative

Patient advocates described how patients have the responsibility to take ownership over their health and care. Taking ownership involves driving their needs and driving collaboration between different care components, including health professionals, social, and community. As a ‘member’ of the IPCP team, this patient role balances autonomy with engagement with the team. It removes complete reliance on health professionals and is instead shared:

‘…it's about encouraging them to get to a point where they, they can master it and look after it themselves, and you know they don't need all these people around them all the time’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 3, Advocacy Officer

Taking ownership of their healthcare requires a whole‐picture insight. Patient advocates provided examples of patient insights including knowledge of who is involved, the role of team members, external supports and service options, tests/procedures/investigations, and their healthcare rights. Patient knowledge may come from seeking further education from health professionals by asking the right questions:

‘I can ask for a second opinion. I can ask, “Can you explain that to me? What are my options in that”?’ – Focus Group 2 Participant 5, Mental Health Consumer Rep

Advocates highlighted the need for individuals to advocate for themselves in their care. This self‐advocacy role covers safety, quality, and ethical practice across all healthcare settings, not just primary care, and within the various organisations where they receive care. ‘Flying their own flag’ was a phrase used by one advocate who expressed how some people can self‐advocate.

A key part of a patient advocacy role is the ability to speak up for themselves in their care. Participants highlighted the strength of the person's voice when used appropriately to include having a say, ensuring that health professionals are listening, expressing needs and wants and asking questions, especially ‘why?’. Speaking up is considered especially important when aspects of care are not working:

‘I think it is important that we are our own advocates because if a GP or other primary carer doesn't know that something's not working, or something's not right they can't do anything about it, so we're the ones who need to speak up and say no, this isn't working, no this isn't quite right, no I need something more, need something else’.– Focus Group 2 Participant 1, Mental Health Consumer Representative

Additional to self‐advocacy, patient advocates described a patient role involving navigation and coordination within the healthcare system. Navigation by a patient is particularly necessary when IPCP is lacking or done poorly. Patients can identify when collaboration is lacking when health professionals communicate poorly, causing patient concern. However, the ability to navigate and coordinate care is reliant on an individual's capacity underpinned by sound health literacy and self‐confidence.

‘If the person is not receiving collaborative care and the professionals are not communicating with each other then it's very hard for that person to navigate the system and they really need to pull all the bits of information together and it's a big task for that person. It's reliant on them being able to navigate the information, navigate the services’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 1, Health Professional Representative

Patient advocates acknowledged the importance of involving family and carers in IPCP and sharing the patient role to relieve some stress from the individual. In vulnerable populations, including mental health and people with disabilities, if the patient is unable to care for themselves, with the individual's consent, the family and/or carer may then need to fulfil the individual's role. The person's condition and care also impact family and carers. This quote outlines the importance of the individual consenting family and carer involvement:

‘From a mental health perspective, it's not collaborative if it doesn't involve the consumer and if appropriate or if the consumer has identified they'd like their carer/family involved too’. ‐ Focus Group 1 Participant 4, Mental Health Consumer Representative

3.1.3. Sub‐theme 1.3: Disengaging from the team

Patient advocates reported that a common role that patients play is independent from any form of IPCP. In some situations, patients felt alienated in healthcare and left to fend for themselves. This disconnect stems from two drivers: (1) they chose to disconnect due to a negative health experience or (2) they were in a transition period in their wider life and were unsure of how to re‐engage with a new team. This transition period could be change in home address or workplace, change in healthcare needs, or moving from paediatric to adult care. Disconnect was common in those moving from paediatric care, where IPCP was conducted well and patients felt supported, to adult care. Adult care was described as less organised, and they felt isolated in their care with less support compared to being cared for by a paediatric team:

‘When kids get to a certain age, you know 16, 17, 18 and they had to transition out of paediatrics to adult services, that's often when things do go astray, because they're on their own to a certain extent’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 3, Advocacy Officer.

Disconnecting from health professionals was also described in the context of primary healthcare within CALD and Indigenous communities. The complex socio‐cultural structures of individual communities and mobs provided additional barriers to engagement with IPCP teams, as described by this consumer representative on communicating potential patient involvement:

‘There's extra barriers of even communicating to people on how they're involved, cause if you can't communicate that in the first place, or there's different broader challenges I think in even having those discussions’. – Focus Group 1 Participant 4, Mental Health Consumer Representative

3.2. Theme 2: Juggling roles

Participants reported that the patient role was not the only role that individuals play. People juggle their patient role amongst other life roles such as employee, daughter, and father.

3.2.1. Subtheme 2.1: Integrating patient role with wider roles

Patient roles were described by advocates as not just roles played in healthcare settings, but in all aspects of life including within the workplace, education institutions, at home, and in their communities. Advocates explained that people are required to manage their condition in these places, and thus may require broader team members that are non‐health professionals. Employers, human resources, and teachers were some examples named by patient advocates. Occasionally, the role as patient, or the role expected of them, was de‐prioritised over a patient's other roles, such as employee, peer, spouse, parent, or friend. This advocacy officer described how she assists individuals in integrating their role as patient into other aspects of life:

‘…supporting whatever that person needs in terms of their care, support…in the settings within hospital settings, within community settings…issues around driving, mental health, lifestyle things, their rights, workplace…’ ‐ Focus Group 1 Participant 3, Advocacy Officer

3.2.2. Subtheme 2.2: Learning about the patient role

Patient advocates reported that patients learn about their role in an ad hoc manner, through a lived experience or accumulation of experiences. Negative healthcare experiences were described as stronger catalysts to learning about the patient role than positive. Self‐learning through trial and error was a difficult process for many consumer advocate participants, driving their current advocate positions, so that others may not have to share their personal negative experiences. The perception of healthcare rights supported learning about patients' roles when caring for themselves. Patient advocates stressed the possible changing nature of roles in IPCP and ongoing learning of new roles as a patient's healthcare journey progresses. This consumer representative highlighted how identifying one's roles is an individual learning process:

‘I just found that [your role is] a personal thing. It's something that you have to develop for yourself…It's gotta be a personal thing, it's something that you have to come to yourself or have experienced what I did’. – Focus Group 2 Participant 3, First Nations' Consumer Representative

4. DISCUSSION

This research explored the roles, current and potential, of patients in IPCP in primary care from the perspective of patient advocates. Key findings were that patient roles in IPCP are on a dynamic spectrum, and are influenced by individual and broader determinants including personality, diagnosis, condition status, socioeconomic background, and health literacy. Additionally, individuals are juggling their role as patient embedded within broader life roles including employer, carer, community member, and spouse.

The dynamic spectrum of patient roles identified in our research is important for policy makers and health professionals to understand and acknowledge. To increase patient autonomy, health professionals should identify patients' role‐preference for current circumstances. There are circumstances where it is appropriate for individuals to relinquish control to the IPCP team such as in emergency situations, a new or rapidly changing status, or reduced self‐care capacity (Bester et al., 2016). Capacity assessment tools for acute medical situations exist (Barstow et al., 2018); however, assessing capacity of otherwise able patients to engage fully in primary care IPCP settings during vulnerable periods is less defined.

Our findings will assist policy makers from government (public), non‐government (not‐for‐profit), and private healthcare organisations to understand how they can organise health services to enable patient engagement to provide more effective primary healthcare. The findings are also important for primary healthcare professionals' practice, in particular understanding that the patient role is fluid and dependent on circumstances. Patient advocate participants perceived the ideal role for patients as being equal and engaged members of the IPCP team, aligning with the WHO definition of IPCP ‘…multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients…’(World Health Organization, 2010). Patients as equal partners is also acknowledged broadly across healthcare professional bodies for chronic condition management (Australian Health Minister's Advisory Council, 2017; The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2020). For more effective engagement in IPCP, patients require a range of skills including health literacy to communicate across different health professionals, self‐efficacy, and an ability to take initiative (Kleman et al., 2021; Mackey et al., 2016; Nutbeam & Lloyd, 2021).

One ideal patient role comprised undertaking self‐management tasks, a key component in chronic condition management (Greenhalgh, 2009). Patient self‐management challenges indicate the need for health professional support (Kleman et al., 2021). Traditionally, health professionals have been encouraged to provide patient self‐management education (Rochfort et al., 2018). A 2018 systematic review investigating the impact of self‐management training for health professionals found limited benefit to patient outcomes for chronic condition management (Rochfort et al., 2018). This review suggested that there may be greater success from patient self‐management education arising from other streams, such as peer support groups and community programmes, reflecting collaborations across healthcare and social services (Kwan et al., 2017; Rochfort et al., 2018; Tung et al., 2018). However, such programmes and collaborations are underutilised in primary care (Saunders et al., 2019).

Health professionals may need to adapt practices when working with CALD or First Nations' individuals due to the health professionals' inadequate experience, and lack of understanding of cultural practices and traditions (Wilson et al., 2020). Additionally, appropriate inclusion of family and carers, with the patient's consent, is vital when the patient may be unable to independently care for themselves, such as in the context of frailty, end‐of‐life, and disability (Bester et al., 2016). Groups requiring particular attention, such as those of CALD backgrounds, or those with reduced capacity, may need enhanced therapeutic relationships built on trust and respect between all parties (Wilson et al., 2020).

Individuals may require varying levels of support depending on their reason for disengaging from the IPCP team, for example, due to a minor or major life change. A key major life change is during the transition period between paediatric and adult care, where patients can experience poorer chronic condition management (Hepburn et al., 2015). This has been extensively explored in the literature across multiple chronic conditions (Bratt et al., 2018; Nandakumar et al., 2018; Toulany et al., 2019). One qualitative study found that paediatric patients and their parents felt less supported by primary healthcare professionals than hospital‐based professionals in cancer care transition (Nandakumar et al., 2018). This is a potential area for improvement by primary healthcare professionals, who could utilise IPCP and transitional policies to support such transitions, including healthcare system changes, and management of the psychosocial impacts of individual development from adolescence to adulthood (Hepburn et al., 2015). Patient disengagement resulting from changes to geographical location, such as an interstate move, can be challenging for an individual to re‐engage. Relocation during the process of diagnosis or during treatment has been demonstrated to have a negative impact on individual outcomes (Genereux et al., 2021; Muralidhar et al., 2016). However, these studies are from international settings and literature in the Australian setting is scarce. The described transitional periods highlight areas where patients' roles in IPCP can be difficult and require a coordinated policy response.

The requirement of the patient role to fit within the individual's life was strongly highlighted within theme two. The patient role is merely one component of the patient's life, but it is a component that required self‐education and practice. Health literacy and advocacy skills are two key factors that supported individuals to readily joining the IPCP team. Strong health literacy enables an individual to understand their condition (Greenhalgh, 2009) and know how to work with primary healthcare professionals and the healthcare system (Kwan et al., 2017). Support from primary healthcare professionals to provide adequate patient education to understand their individual condition/s is lacking (Rochfort et al., 2018). Therefore, individuals may need to seek multiple routes to improve health literacy and thus their ability to self‐manage, such as broader advocacy training, assistance from public and private organisations, including healthcare professionals (Kwan et al., 2017). However, the effectiveness of patient advocacy training is poorly reported in the literature and requires further investigation.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Purposive sampling of advocates from organisations representing patients from a variety of chronic conditions and advocacy backgrounds, e.g., consumer, carer, health, or other professional, to obtain diversity in the responses is a strength of our study. However, it is possible that only patient advocates who were interested in the topic responded as response to recruitment invitations was voluntary. Responses from interested participants are consistent with qualitative research which seeks participants that are rich data sources. The use of online focus groups was another potential study limitation. Online data collection may be limited by unforeseen technological issues (Dos Santos Marques et al., 2021). However, with the change in communication globally due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, all participants in this study had a reasonable level of technology literacy and used Zoom for their advocacy group meetings, other professional and private communications, and thus were familiar with the format. Additionally, focus group participants were grouped according to convenience where groups were formed once enough participants agreed to a suitable date and time of the interview. Difficulty recruiting was experienced in this study due to time constraints from the pressure of the COVID‐19 pandemic, much like many other areas of healthcare research (Mirza et al., 2022). Another limitation was the involvement of patient advocates only, rather than patients themselves. Patient advocate participants in the current study had varying levels of advocacy training from their organisation, and many had higher education and literacy levels, especially those from professional backgrounds. Therefore, future research should involve individuals with first‐hand lived experience who have not received similar training and may have lower health literacy.

5. CONCLUSION

Our research has highlighted that patient advocates believe that patients should be more engaged in IPCP with their primary care teams. This role may fluctuate and move among the three points across a spectrum: relinquishing control to the team, joining the team (where patients are actively partnering with health professionals) and disengaging from the team, and acknowledged as only one aspect of the patient's life. Our findings have highlighted several specific research and practice improvement areas. The most pressing need is for policy makers to support the development of a relevant tool for use in primary healthcare settings that establish and promote the patient role in IPCP. There are no known tools at present, and future research should endeavour to develop such a tool to support both health professionals and patients in this space.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the research aim and study design. AD conducted data collection and initial stages of data analysis with DR. All authors contributed to theme and sub‐theme development. AD developed the manuscript draft, and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research study was funded by AD's higher degree research budget.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

MM is practising general practitioner. He receives consultancy fees from the Gold Coast Primary Healthcare Network, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Australian Department of Health. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

Appendix S3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient advocates who participated in this research project and thank them for their insights and expertise on the topic. This research study was funded by AD's higher degree research budget, as part of the Australian Government Research Training Program. During this study, AD was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program stipend. LB's salary was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Research. Open access publishing facilitated by Bond University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Bond University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians. [Correction added on 28 November 2022, after first online publication: CAUL funding statement has been added.]

Davidson, A. R. , Morgan, M. , Ball, L. , & Reidlinger, D. P. (2022). Patient advocates' views of patient roles in interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care: A constructivist grounded theory study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e5775–e5785. 10.1111/hsc.14009

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Atlassian . (2022). Trello. In https://trello.com/en

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . (2019). National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18: Chronic Conditions . Retrieved 5 September from: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2017‐18~Main%20Features~Chronic%20conditions~25

- Australian Health Minister's Advisory Council . (2017). National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions. Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, M. , Jowsey, T. , Parkinson, A. , Douglas, K. A. , & Dawda, P. (2017). Experiencing integration: a qualitative pilot study of consumer and provider experiences of integrated primary health care in Australia. BMC Family Practice, 18(1), 2. 10.1186/s12875-016-0575-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barstow, C. , Shahan, B. , & Roberts, M. (2018). Evaluating medical decision‐making capacity in practice. American Family Physician, 98(1), 40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, U. E. , Briss, P. A. , Goodman, R. A. , & Bowman, B. A. (2014). Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet, 384(9937), 45–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648‐6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester, J. , Cole, C. M. , & Kodish, E. (2016). The limits of informed consent for an overwhelmed patient: clinicians' role in protecting patients and preventing overwhelm. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(9), 869–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloor, M. , Frankland, J. , Thomas, M. , & Robson, K. (2001). Focus Groups in Social Research. SAGE Publications Ltd. 10.4135/9781849209175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, T. , & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573–576. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratt, E. L. , Burström, Å. , Hanseus, K. , Rydberg, A. , & Berghammer, M. (2018). Do not forget the parents—Parents' concerns during transition to adult care for adolescents with congenital heart disease. Child: Care, Health & Development, 44(2), 278–284. 10.1111/cch.12529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault, I. , Kilpatrick, K. , D'Amour, D. , Contandriopoulos, D. , Chouinard, V. , Dubois, C.‐A. , Perroux, M. , & Beaulieu, M.‐D. (2014). Role clarification processes for better integration of nurse practitioners into primary healthcare teams: A multiple‐case study. Nursing Research and Practice, 2014(2014), 170514–170519. 10.1155/2014/170514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley, B. , Williams, L. T. , Morgan, M. , Ross, A. , Trigger, K. , & Ball, L. (2021). Putting patients first: Development of a patient advocate and general practitioner‐informed model of patient‐centred care. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 261. 10.1186/s12913-021-06273-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, J. F. P. , Janssen, E. M. , Ferris, A. , & Dy, S. M. (2018). Project Transform: Engaging patient advocates to share their perspectives on improving research, treatment and policy. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 34(10), 1755–1762. 10.1080/03007995.2018.1440199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practice guide through qualitative analysis (Second Edition ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A. R. , Kelly, J. , Ball, L. , Morgan, M. , & Reidlinger, D. P. (2022). What do patients experience? Interprofessional collaborative practice for chronic conditions in primary care: an integrative review. BMC Primary Care, 23(1), 8. 10.1186/s12875-021-01595-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2020). Primary Care . Retrieved May 21 from https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/primarycare

- Dos Santos Marques, I. C. , Theiss, L. M. , Johnson, C. Y. , McLin, E. , Ruf, B. A. , Vickers, S. M. , Fouad, M. N. , Scarinci, I. C. , & Chu, D. I. (2021). Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collection in a global pandemic. American Journal of Surgery, 221(5), 918–922. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, C. , Lennox, L. , & Bell, D. (2013). A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open, 3(1), e001570. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genereux, D. , Fan, L. , & Brownlee, K. (2021). The psychosocial and somatic effects of relocation from remote Canadian first nation communities to urban centres on indigenous peoples with chronic kidney disease (CKD). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3838. 10.3390/ijerph18073838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T. (2009). Patient and public involvement in chronic illness: Beyond the expert patient. BMJ, 338, b49. 10.1136/bmj.b49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G. , Namey, E. , & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. 10.1177/1525822x16639015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. F. , Jayasinghe, U. W. , Taggart, J. R. , Christl, B. , Proudfoot, J. G. , Crookes, P. A. , Beilby, J. J. , & Powell Davies, G. (2011). Multidisciplinary Team Care Arrangements in the management of patients with chronic disease in Australian general practice. Medical Journal of Australia, 194(5), 236–239. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb02952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Consumers Queensland . (2017). Consumer and Community Engagement Framework. Brisbane: Health Consumers Queensland Retrieved from https://www.hcq.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2017/03/HCQ‐CCE‐Framework‐2017.pdf

- Hepburn, C. M. , Cohen, E. , Bhawra, J. , Weiser, N. , Hayeems, R. Z. , & Guttmann, A. (2015). Health system strategies supporting transition to adult care. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(6), 559–564. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleman, C. , Mesmer, J. , Andrews, M. , Lutz, B. , & Meyer, K. (2021). “Being Sick Is a Full‐Time Job”: A Job Analysis of Managing a Chronic Illness. Health Services Research, 56(S2), 10–11. 10.1111/1475-6773.13726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, B. M. , Jortberg, B. , Warman, M. K. , Kane, I. , Wearner, R. , Koren, R. , Carrigan, T. , Martinez, V. , & Nease, D. E., Jr. (2017). Stakeholder engagement in diabetes self‐management: patient preference for peer support and other insights. Family Practice, 34(3), 358–363. 10.1093/fampra/cmw127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben, J. , Peccei, R. , Adams, M. , Robert, G. , Richardson, A. , Murrells, T. , & Morrow, E. (2012). Exploring the relationship between patients' experiences of care and the influence of staff motivation, affect and wellbeing. Final report. Southampton: NIHR service delivery and organization programme.

- Mackey, L. M. , Doody, C. , Werner, E. L. , & Fullen, B. (2016). Self‐Management skills in chronic disease management: What role does health literacy have? Medical Decision Making, 36(6), 741–759. 10.1177/0272989X16638330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M. , Siebert, S. , Pratt, A. , Insch, E. , McIntosh, F. , Paton, J. , Wright, C. , Buckley, C. D. , Isaacs, J. , McInnes, I. B. , Raza, K. , & Falahee, M. (2022). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on recruitment to clinical research studies in rheumatology. Musculoskeletal Care, 20(1), 209–213. 10.1002/msc.1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidhar, V. , Nguyen, P. L. , & Tucker‐Seeley, R. D. (2016). Recent relocation and decreased survival following a cancer diagnosis. Preventive Medicine, 89, 245–250. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, B. S. , Fardell, J. E. , Wakefield, C. E. , Signorelli, C. , McLoone, J. K. , Skeen, J. , Maguire, A. M. , Cohn, R. J. , Alvaro, F. , Cohn, R. , Corbett, R. , Downie, P. , Egan, K. , Emery, J. , Ellis, S. , Emery, J. , Fardell, J. , Foreman, T. , Gabriel, M. , Girgis, A. , Graham, K. , Johnston, K. , Jones, J. , Lockwood, L. , Maguire, A. , McCarthy, M. , McLoone, J. , Molloy, S. , Osborn, M. , Signorelli, C. , Skeen, J. , Tapp, H. , Till, T. , Truscott, J. , Turpin, K. , Wakefield, C. , Walwyn, T. , Yallop, K. , & on behalf of the, A. S. S. G . (2018). Attitudes and experiences of childhood cancer survivors transitioning from pediatric care to adult care. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(8), 2743–2750. 10.1007/s00520-018-4077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D. , & Lloyd, J. (2021). Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 159–173. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, B. C. , Harris, I. B. , Beckman, T. J. , Reed, D. A. , & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/09000/Standards_for_Reporting_Qualitative_Research__A.21.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi, W. , & Raghupathi, V. (2018). An empirical study of chronic diseases in the United States: A visual analytics approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 431. 10.3390/ijerph15030431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview‐based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochfort, A. , Beirne, S. , Doran, G. , Patton, P. , Gensichen, J. , Kunnamo, I. , Smith, S. , Eriksson, T. , & Collins, C. (2018). Does patient self‐management education of primary care professionals improve patient outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 163. 10.1186/s12875-018-0847-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, C. , Carter, D. , & Brown, J. J. (2019). Primary care experience of older Australians with chronic illness. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 25(1), 13–18. 10.1071/PY18098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbaraini, A. , Carter, S. M. , Evans, R. W. , & Blinkhorn, A. (2011). How to do a grounded theory study: A worked example of a study of dental practices. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 128. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, L. (2002). Is there an advocate in the house? The role of health care professionals in patient advocacy. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28(1), 37–40. 10.1136/jme.28.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassiani, N. A. , Sawyer, A. R. , Chacra, M. S. A. , Koch, K. , Muñoz, Y. A. , & Lunsky, Y. (2016). "Teaches People That I'm More Than a Disability": using nominal group technique in patient‐oriented research for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(2), 112–122. 10.1352/1934-9556-54.2.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . (2020). Management of type 2 diabetes: A handbook for general practice. RACGP; Retrieved from https://www.racgp.org.au/getattachment/41fee8dc‐7f97‐4f87‐9d90‐b7af337af778/Management‐of‐type‐2‐diabetes‐A‐handbook‐for‐general‐practice.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Toulany, A. , Stukel, T. A. , Kurdyak, P. , Fu, L. , & Guttmann, A. (2019). Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Network Open, 2(8), e198415. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman, K. , McCormack, L. , Olmsted, M. , Roach, N. , Reeve, B. B. , Martens, C. E. , Moultrie, R. R. , & Sanoff, H. (2017). Engaging patient advocates and other stakeholders to design measures of patient‐centered communication in cancer care. Patient, 10(1), 93–103. 10.1007/s40271-016-0188-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung, E. L. , Gunter, K. E. , Bergeron, N. Q. , Lindau, S. T. , Chin, M. H. , & Peek, M. E. (2018). Cross‐sector collaboration in the high‐poverty setting: qualitative results from a community‐based diabetes intervention. Health Services Research, 53(5), 3416–3436. 10.1111/1475-6773.12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen, J. , de Wit, M. , Smeets, H. W. H. , Stoffers, E. , van Bokhoven, M. A. , & Daniels, R. (2017). "They Are Talking About Me, but Not with Me": A Focus Group Study to Explore the Patient Perspective on Interprofessional Team Meetings in Primary Care [Research Support, Non‐U.S. Gov't]. The Patient: Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research, 10(4), 429–438. 10.1007/s40271-017-0214-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen, J. J. J. , Lenzen, S. A. , van Bokhoven, M. A. , Daniëls, R. , van Der Weijden, T. , & Beurskens, A. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients' care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors. BMC Family Practice, 17, 58–10. 10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Water, T. , Ford, K. , Spence, D. , & Rasmussen, S. (2016). Patient advocacy by nurses ‐ past, present and future. Contemporary Nurse, 52(6), 696–709. 10.1080/10376178.2016.1235981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A. M. , Kelly, J. , Jones, M. , O'Donnell, K. , Wilson, S. , Tonkin, E. , & Magarey, A. (2020). Working together in Aboriginal health: A framework to guide health professional practice. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 601. 10.1186/s12913-020-05462-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ [PubMed]

- Zoom Video Communications, I . (2021). Zoom . https://zoom.us/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

Appendix S3

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.