Abstract

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease resulting in airflow obstruction, which in part can become irreversible to conventional therapies, defining the concept of airway remodeling. The introduction of biologics in severe asthma has led in some patients to the complete normalization of previously considered irreversible airflow obstruction. This highlights the need to distinguish a “fixed” airflow obstruction due to structural changes unresponsive to current therapies, from a “reversible” one as demonstrated by lung function normalization during biological therapies not previously obtained even with high‐dose systemic glucocorticoids. The mechanisms by which exposure to environmental factors initiates the inflammatory responses that trigger airway remodeling are still incompletely understood. Alarmins represent epithelial‐derived cytokines that initiate immunologic events leading to inflammatory airway remodeling. Biological therapies can improve airflow obstruction by addressing these airway inflammatory changes. In addition, biologics might prevent and possibly even revert “fixed” remodeling due to structural changes. Hence, it appears clinically important to separate the therapeutic effects (early and late) of biologics as a new paradigm to evaluate the effects of these drugs and future treatments on airway remodeling in severe asthma.

Keywords: airway remodeling, biologics, biomarkers, immunotherapies, severe asthma

Abbreviations

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

- ANGPT

angiopoietin

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- BAL

brocho‐alveolar lavage

- βc

common receptor β subunit

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRSwNP

chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- DC

dendritic cell

- EBUS

endobronchial ultrasound

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ECP

eosinophil cationic protein

- EDN

eosinophil‐derived neurotoxin

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EMT

epithelial‐mesenchymal transition

- EPX

eosinophil peroxidase

- FcεRI

high affinity IgE

- FeNO

fractional exhaled nitric oxide

- FDA

food and drug administration

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GINA

global initiative for asthma

- GM‐CSF

granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor

- HLM

human lung macrophage

- HLMC

human lung mast cell

- HRCT

high‐resolution computed tomography

- IL

interleukins

- IL‐5Rα

IL‐5 receptor α

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- i.v.

intravenously

- lfTSLP

long form TSLP

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MBP

major basic protein

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NET

neutrophils extracellular trap

- NHR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NK cell

natural killer cell

- NKT cell

natural killer T cell

- PDGF

platelet‐derived growth factor

- PGD2

prostaglandin D2

- RCTs

randomized clinical trials

- sfTSLP

short form TSLP

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor β

- TSLP

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- T2‐high

type 2‐high

- T2‐low

type 2‐low

- VDP

ventilation defect

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factors

1. INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory disease of the respiratory system that affects approximately 10% of adults. 1 A typical feature of asthma is a variable airflow limitation associated with symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness. 2 The heterogenicity of the immunologic disorder is reflected in different phenotypes that differ in etiology, pathogenic mechanisms, symptoms, and severity. 3 Based on airway inflammation, asthma has been subdivided into type 2‐high (T2‐high) and type 2‐low (T2‐low), although the latter form is rare in clinical practice. 3 , 4 , 5 A similar distinction is made between eosinophilic and non‐eosinophilic asthma (GINA 2021). 6 Severe asthma is defined as asthma that is not well controlled despite the adherence to maximal optimized pharmacological therapy and treatment of contributory factors. 7 Up to 6% of asthma patients have severe asthma, with a reduced quality of life, and increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death. 8 , 9

In T2‐high asthma, immunologic stimuli (e.g., allergens, and viral and bacterial superantigens) activate primary effector cells of allergic disorders (i.e., mast cells and basophils) through the engagement of specific IgE to release a plethora of interleukins (ILs) (e.g., IL‐3, IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13). 10 , 11 Eosinophils and their mediators contribute to the pathogenesis of IgE‐mediated asthma and play pivotal roles in eosinophilic asthma. T2‐low asthma is heterogeneous, incompletely defined and understood and presumably includes different phenotypes characterized by the involvement of mast cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and/or a mixture of these immune cells. 3 , 5 Bronchial epithelial cell‐derived alarmins (e.g., TSLP, IL‐33, and IL‐25) are upstream cytokines that initiate immunologic events culminating in airway remodeling. 12 , 13 , 14 The latter is a complex process requiring a timely expression of fibrogenic 15 and angiogenic factors causing profound structural alterations of the bronchial walls and blood vessels. 16 , 17 These alterations contribute to the reduction of airway caliber and stiffening, resulting clinically in airflow limitations and respiratory symptoms. 18

2. AIRWAY REMODELING

Airway remodeling can affect both large and small airways 19 and is characterized by structural changes including goblet cell metaplasia, subepithelial matrix protein deposition and fibrosis, overexpression of angiogenic factors, and hyperplasia/hypertrophy of airway smooth muscle cells. 15 , 16 , 17 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Increased deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in the reticular basement membrane (RBM), lamina propria, and submucosa is a characteristic of asthmatic airways and contributes to the airway wall thickening and airflow obstruction. 24 , 25 Collagen fibers, fibronectin, and tenascin are the most abundant elements of the ECM in the asthmatic lung. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Aberrant accumulation of ECM proteins leads to alterations in tissue structure and function, contributing to airway remodeling in asthma. 30 , 31 , 32 ASM hypertrophy/hyperplasia (e.g., increased ASM mass) are features of asthmatic airway remodeling. 18 , 33 , 34 , 35 ASM cells in asthmatic individuals also produce increased amounts of collagen and fibronectin. 36 , 37 The increase in the ASM mass contributes to bronchial obstruction, 38 loss of lung function, 21 and greater susceptibility to external triggers. 20 , 39 , 40 Airway remodeling has been implicated in irreversible airflow limitation with consequent poor symptom control and lack of response to treatment. 21 , 41 , 42

The airway epithelium is a key component of the innate immune system and the initiator of airway remodeling in asthma. 14 A plethora of environmental insults (e.g., allergens, cytokines, microbial proteins, smoke extracts, and chemical and physical insults) damage and/or activate epithelial cells to release several cytokines, including TSLP, 13 , 43 IL‐33, 14 , 44 IL‐25/IL‐17E, 12 TGF‐β, and granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), which can recruit/activate dendritic cells (DCs), type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), mast cells, eosinophils, and other immune cells. 45

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), constitutively expressed by human bronchial epithelial cells, 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 can be rapidly released as a result of cell injury in response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli. 46 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 TSLP is also released by DCs, 55 mast cells, 56 human lung macrophages (HLMs), 57 and fibroblasts. 58 , 59 TSLP exerts its effects by binding to a high‐affinity heterodimeric receptor complex composed of TSLPR and IL‐7Rα. 13 There are two isoforms of TLSP: the long (lf) and the short (sf) isoforms; the former is also known as TSLP and its expression increases during inflammation. 57 , 60 The sfTSLP, constitutively expressed in epithelial cells, lung fibroblasts, and HLMs, 57 , 61 is not upregulated by inflammation. For instance, house dust mites induce lfTSLP but not sfTSLP in human bronchial epithelial cells. 62 TSLP immunostaining is increased in the airway epithelium in asthmatic patients, 49 and its concentrations are increased in the broncho‐alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of asthmatics. 48 TSLP is overexpressed in the airways of severe asthma patients, 48 and bronchial allergen challenge of asthmatics increases the expression of TSLP+ cells in the epithelium and submucosa. 47

TSLP promotes allergic responses and airway remodeling 63 by acting on DCs, 55 thereby promoting the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells 64 , 65 and by inducing the survival of ILC2s 13 , 66 , 67 and the induction of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) in airway epithelial cells. 68 Human lung fibroblasts are also a significant source of TSLP. 59 , 69 Through an autocrine mechanism, TSLP can activate human lung fibroblasts 70 to release type I collagen 71 and promote the proliferation of ASM cells. 72 TSLP has also been shown to cause goblet cell metaplasia and mucus production. 73 , 74 , 75 TSLP activates human eosinophils, 13 mast cells, 56 , 76 and HLMs. 57 The multiple activating properties of TSLP on a plethora of immune and structural cells indicate that this cytokine plays a role in T2‐high and T2‐low asthma.

IL‐33, an IL‐1 superfamily alarmin released by airway epithelial cells and endothelial cells, 77 activates the ST2 receptor on several cells of the innate and adaptive immunity. 77 IL‐33 activates ILC2s 78 , 79 , 80 and induces type 2 cytokines (i.e., IL‐5 and IL‐13) in human mast cells, 81 collagen, and fibronectin release from airway fibroblasts. 82 , 83 IL‐33 and superantigenic activation of human lung mast cells (HLMCs) induce the release of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors. 84 IL‐33, alone and in combination with IL‐3, activates human basophils to release a wide spectrum of cytokines (i.e., IL‐4, IL‐13, CXCL8, and VEGF‐A). 85 , 86 IL‐33 expression is associated with enhanced RBM thickness in bronchial biopsies of tissues severe asthmatic children. 83 In addition, it has been reported that airway remodeling is absent in ST2−/− mice in a model of house dust mite (HDM)‐induced asthma. 83 Collectively, IL‐33 and IL‐33/ST2 signaling pathways might be involved in both airway inflammation and asthma remodeling through the activation of several immune and structural cells.

IL‐25, also known as IL‐17E, is a unique cytokine of the IL‐17 family produced by a subset of airway epithelial cells (i.e., brush cells). 12 , 87 , 88 Airborne allergens, ATP, and viral infections upregulate IL‐25 and its receptor IL‐17RB in airway epithelial cells and submucosa. 89 , 90 IL‐25 activates ILC2s, 91 modulates EMT of alveolar epithelial cells and local tissue remodeling, 92 and upregulates cytokine expression in lung fibroblasts. 93 IL‐25 drives lung fibrosis in several mouse models. 92 , 94 , 95

A plethora of cytokines (transforming growth factor β [TGF‐β], platelet‐derived growth factor [PDGF], fibroblast growth factor [FGF], epidermal growth factor [EGF], vascular endothelial growth factors [VEGFs]), and chemokines (e.g., CXCL2, CXCL3, IL‐8/CXCL8) contributes directly and indirectly to airway remodeling in asthma. 96 , 97 , 98 In particular, TGF‐β, produced by macrophages and eosinophils, is a main mediator responsible for airway remodeling by inducing epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT). 99 IL‐4 activates ASM cells, causing an increase in actin and collagen synthesis as well as TGF‐β release by the bronchial epithelium. 20 , 100 IL‐5 promotes subepithelial and peri‐bronchial fibrosis through the recruitment and activation of eosinophils, a major source of TGF‐β. 101 , 102 IL‐13 induces the release of TGF‐β from bronchial epithelial cells, which increases goblet cell metaplasia. 20 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106

IgE itself could play a role in airway remodeling by stimulating the production of interleukins. 107 Several investigators have reported that human monomeric IgE, in the absence of cross‐linking, can induce the release of cytokines (e.g., IL‐4) and chemokines (e.g., CXCL8) from mast cells. 108 , 109 Moreover, Roth et al have shown that in vitro incubation of serum containing IgE obtained from allergic asthmatics caused ASM proliferation and marked production of type I collagen. 110

Similarly, a large number of cells of the innate and adaptive immune system contribute directly and indirectly to airway remodeling in asthma. Human eosinophil granules are armed with cytotoxic major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil peroxidase (EPX), eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), eosinophil‐derived neurotoxin (EDN), and galectin‐10 (also known as Charcot‐Leyden protein). 111 ECP and MBP induce the release of preformed (histamine and tryptase) and de novo synthesized mediators (prostaglandin D2: PGD2) from human mast cells. 112 , 113 , 114 Activated human eosinophils secrete LTC4 and a wide array of type 2 cytokines (e.g., IL‐5, IL‐4, and IL‐13) and TGF‐β. 96 , 115 Altogether, current data indicate that eosinophils play a globally pathogenic role in airway remodeling.

Macrophages (alveolar and interstitial) are the most abundant immune cell type in human lung 116 , 117 , 118 and are involved in immune responses as well as tissue remodeling. 119 HLMs contribute to airway remodeling through the release of TGF‐β, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), angiogenic (e.g., VEGF‐A and ANGPT2), and lymphangiogenic factors (i.e., VEGF‐C). 57 , 120 HLMCs are important lung‐resident immune cells involved in asthmatic airway remodeling. 121 IgE‐ and non‐IgE‐mediated activation of HLMCs induces the release of several profibrotic cytokines (e.g., IL‐13 and TNF‐α), as well as inflammatory mediators (e.g., PGD2 and tryptase). 113 , 114 Tryptase induces fibroblast, endothelial and epithelial cell proliferation, further fueling airway remodeling in asthmatic individuals. 122 Neutrophils have also been shown to produce MMP‐9, 123 , 124 angiogenic factors, 125 and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) 126 , 127 , 128 and can be associated with severe asthma. 126

Angiogenesis is fundamental to providing the blood vessels to maintain tissue homeostasis, 125 whereas inflammatory angiogenesis is a critical factor in the development of a disease process. 84 , 129 , 130 Blood vessel density and vascular area are increased in patients with asthma. 16 , 17

A recent study in a mouse model of asthma demonstrated dynamic changes in the respiratory microbiota at different stages of the disease. In particular, Staphylococcus and Cupriavidus were more abundant during airway remodeling. 131 Additional studies are urgently needed to investigate whether the dysbiosis of airway microbiota could also play a role in the progression from allergic inflammation to airway remodeling in humans.

2.1. Imaging of airway remodeling

The direct assessment of human airway remodeling can be performed in vivo on bronchial biopsies in asthmatic patients. 115 , 132 , 133 Bronchial biopsies identify useful information on bronchial and pulmonary alterations, such as thickening of the bronchial tissue, infiltration and density of inflammatory cells, aberrant accumulation of elements of ECM, and ASM hyperplasia and hypertrophy. 15 However, this procedure has several limitations that should be pointed out. First, it is not part of the routine clinical evaluation of asthmatic patients. Second, it does not easily facilitate serial biopsies in the same patient. Third, the results can be significantly influenced by the operator and the techniques used to assess tissue remodeling.

During the last decade, high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NHR) are gaining a place as non‐invasive techniques to examine different aspects of airway remodeling in asthma. Hoshino found increased airway wall thickening in asthmatics assessed by HRCT. 134 Bronchial wall thickness assessed by endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) was increased in asthma patients than healthy controls. 135 Hartley et al found that the proximal airway wall area was increased in asthmatics compared to controls. 136 The loss of the peripheral pulmonary vasculature, also termed pruning, was associated with asthma severity. 137 Recently, Eddy and co‐workers demonstrated that the total number of CT‐visible airways was correlated to asthma severity. 138

Preliminary results derive from imaging studies that have evaluated the effects of biological therapies on airway remodeling using HRCT. Hoshino et al reported that 16‐week treatment with omalizumab reduced the airway wall thickness and the number of sputum eosinophils. 139 In another study, 48‐week treatment with omalizumab reduced the airway wall area corrected for body surface, but no changes in percentage wall area, without changes in the luminal area. 140 In two studies conducted by Haldar et al 141 , 142 on airway remodeling by HRCT, it was found that the biological treatment determined a greater variation in pre‐/post‐treatment luminal area compared to the placebo group. A recent study evaluated the impact of one‐year mepolizumab therapy on airway remodeling through EBUS and HRCT. Improved airway remodeling (e.g., reduction in bronchial wall thickness) was better noticeable in invasive EBUS than in non‐invasive HRCT. 143 In the phase 2 CASCADE study, tezepelumab increased the CT scan‐determined lumen area across airway generations. 132

Hyperpolarized helium‐3 MRI of the lung has demonstrated regional heterogeneity of lobar ventilation in asthma, 144 which is correlated with asthma severity. 145 MRI ventilation defects (VDP are correlated to sputum eosinophilia in severe asthma 146 and are a predictor of exacerbation). 147 Collectively, studies with CT and MRI in asthma have shown some structural and functional changes in airways and pulmonary vasculature associated with more severe disease but are unable to differentiate between reversible and potentially irreversible changes.

Finally, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) has been proposed to assess airway structure variations in asthma patients, especially in the distal airway. FeNO was associated with bronchial wall thickening in the third to the sixth generation of bronchial trees. 148

2.2. Single‐cell transcriptomics of airway remodeling

The human lung is a complex tissue which comprises more than 40 cell populations, including immune and structural cells. 149 , 150 Previous investigations of airway remodeling in asthma were limited by the examination of a restricted profile of immune and structural cells. Next‐generation sequencing technologies (RNA‐Seq) are now available to identify transcriptomic map of the human lung. 150 , 151 Transcriptomic analysis of flow cytometry‐sorted cell population from the human lung and single‐cell RNA‐Seq (scRNA‐Seq) allows reliable identification of even closely related cell population. 152 scRNA‐Seq also allows the identification of known or novel cell populations for which there are no reliable surface markers during health and disease. 153 scRNA‐Seq has been recently employed to reveal ectopic and aberrant lung‐resident cell populations in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. 150 , 151 Recently, single‐cell transcriptomic of mouse lung revealed a population of inflammatory memory neutrophils with specific molecular features in a model of allergic asthma. 154 Vieira Braga and collaborators used single‐cell transcriptomics to chart the cellular landscape of airways and lung parenchyma in healthy and asthmatic lungs. These authors discovered a novel subset of CD4+ T cells in asthmatic airway wall and a novel mucous ciliated cell in the airway epithelium that contributes to goblet cell hyperplasia. 133 We anticipate that the use of scRNA‐Seq will provide fundamental information to chart the landscape of immunological and structural cells involved in airway remodeling in different pheno‐endotypes of asthma and the effects of biologics in this heterogeneous disorder.

2.3. Targeting airway remodeling

Experimental and human studies have demonstrated that glucocorticoids and certain anti‐inflammatory drugs can reduce inflammation and morbidity in mild to moderate asthma. However, evidences of beneficial effects of inhaled (ICS) or oral (OCS) glucocorticoids on airway remodeling have not been demonstrated, with several reports showing contradictory results with ICS. 17 , 155 , 156 The introduction of several biological immunotherapies (e.g., anti‐IgE, anti‐IL‐5/IL‐5Rα, anti‐IL‐4Rα, and anti‐TSLP) 2 , 157 has contributed to the development of a personalized medicine approach for the treatment of patients with severe asthma. 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 There is some evidence that these biologics can improve not only clinical symptoms but also certain features of airway remodeling and functional decline of FEV1. It is important to emphasize that FEV1 and other spirometric indices are only surrogate markers of airway remodeling in asthma and any improvement in FEV1 after treatment with biologics could be attributable not only to the attenuation of any remodeling processes but also due to the changes in bronchial hyperreactivity, autonomic nervous system modulation and other factors. Finally, it will be important to evaluate the effects of biological immunotherapies in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and real‐life settings. 162 , 163

2.4. Omalizumab

Omalizumab is a humanized IgG1‐κ monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to the Fc fragment of IgE. 164 This mAb inhibits the binding of IgE to the high‐affinity IgE (FcεRI) receptor on human mast cells, basophils, 165 , 166 and DCs. 167 Several studies have documented the efficacy of omalizumab in improving allergic asthma and reducing symptoms and exacerbations 168 , 169 , 170 also in children and pregnant women. 171 , 172 , 173 Although omalizumab did not cause FEV1 improvement in RCTs, 174 , 175 there is some evidence that this mAb can improve FEV1 in real‐life settings 176 , 177 and can reduce the thickness of the basement membrane 139 , 178 and fibronectin deposits in asthmatic airways 179 in addition to preventing exacerbation‐induced inflammatory alterations in the airways. IgE‐containing serum from asthmatic patients stimulated in vitro mesenchymal cell proliferation and accumulation of collagen and fibronectin. Both proliferation and matrix deposition were prevented by preincubation of the cells with omalizumab. 110

2.5. Mepolizumab

Mepolizumab is an IgG1‐κ anti‐IL‐5 mAb approved as add‐on treatment for severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA). 180 , 181 IL‐5 is the most important growth, differentiation, and activation factor of human eosinophils. 182 This cytokine acts on eosinophils by binding to the specific IL‐5 receptor (IL‐5R), which consists of an IL‐5 receptor α (IL‐5Rα) subunit and the common receptor β subunit (βc). 183 IL‐5, together with IL‐3 and GM‐CSF, 184 is crucial for the maturation of human eosinophils in the bone marrow. 57 , 183 IL‐5 is mainly produced by type‐2 ILC2s, Th2 cells, mast cells, invariant NKT cells, and eosinophils themselves. 182 Human eosinophils can also be activated by IL‐33 77 and TSLP. 13

The efficacy and safety of mepolizumab have been demonstrated in several RCTs. 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 The DREAM study, conducted with mepolizumab at 3 different doses administered intravenously (i.v.), showed the clinical efficacy but there were no statistically significant changes in FEV1, although there was an improvement, compared to baseline, in FEV1 in the mepolizumab group versus placebo. 185 In the MENSA study, the FEV1 increase was rapid, starting from the first administration, and persisted over time. 188 Two additional studies showed a rapid and long‐lasting improvement in pre‐bronchodilator FEV1 in the mepolizumab group compared to placebo. 189 , 190 There is some evidence that mepolizumab can also improve FEV1 in real‐life settings. 191 , 192 , 193

Interestingly, some patients first enrolled in the COSMOS study and subsequently in the long‐term COSMEX study, with a suspension of more than 12 weeks of mepolizumab between the two, reported a transient worsening of their symptoms and FEV1, which rapidly improved upon reintroduction of mepolizumab. 187 A clinical trial (NCT03797404) is evaluating the effects on airway remodeling during mepolizumab treatment.

In a pioneering study, Flood‐Page and collaborators examined the bronchial biopsies of mild atopic asthmatics, treated only with SABA, studied before and after treatment with three mepolizumab infusions. 115 They demonstrated that the thickness and density of tenascin in the RBM, the airway TGF‐β1+ eosinophils, and the BAL concentrations of TGF‐β1 were increased in mild asthmatic patients compared to normal subjects. As expected, mepolizumab reduced bronchial eosinophil numbers but also TGF‐β1+ eosinophils, thickness and tenascin immunoreactivity, and the concentration of TGF‐β1 in BAL fluid. 115

2.6. Reslizumab

Reslizumab is a humanized IgG4‐κ anti‐IL‐5 mAb developed by drafting technology from a rat mAb with high affinity against human IL‐5. 194 Reslizumab binds to a small region corresponding to amino acids 89‐92 of IL‐5, which are critical for binding to IL‐5Rα. 195 Reslizumab administration results in clinical improvement in asthma and an increase in FEV1 in patients with eosinophilic counts >400 cells/μl compared to placebo. 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 Apparently contrasting results have been reported on the effects of reslizumab on the improvement of FEV1 compared to placebo. Although several studies reported that reslizumab significantly improved FEV1 compared to placebo, 196 , 199 other investigators found that reslizumab had no improvement in FEV1 compared to those receiving placebo. 196 A real‐life study recently confirmed the efficacy of reslizumab treatment in reducing the number of exacerbations and increasing FEV1 6 months after the beginning of treatment. 201 Further investigations are needed to evaluate the potential role of reslizumab on mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of airway remodeling in asthma patients.

2.7. Benralizumab

Benralizumab is a humanized, afucosylated IgG1‐κ mAb that targets the α subunit of the IL‐5 receptor (IL‐5Rα) and it binds via the constant Fc fragment to the FcγRIIIa receptor for IgG expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, which results in eosinophil apoptosis via antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity. 202 Several studies have demonstrated that benralizumab administration leads to subjective and functional clinical improvement in patients with SEA. RCTs reported an improvement in FEV1 at 12 weeks from the beginning of treatment. 203 , 204 , 205 A post hoc analysis conducted on SIROCCO and CALIMA data further documented that benralizumab promoted functional improvement even in patients with fixed airflow obstruction, an alteration found in approximately 16% of patients with severe asthma. 206 A recent study extended the previous results by showing that benralizumab caused a rapid (4 weeks) improvement in FEV1, which increased after 12 weeks and persisted throughout the period (24 weeks) of observation. 205

Cachi and collaborators evaluated the effects of benralizumab on airway remodeling by examining biopsies from patients with SEA. 207 Benralizumab reduced the number of eosinophils in the bronchial lamina propria and ASM mass compared to placebo. In the benralizumab group, there were no significant changes in the number of myofibroblasts compared to the control group. The effects of benralizumab on ASM mass were attributed to an indirect effect mediated by the depletion of local TGF‐β1+ eosinophils in the bronchial lamina propria.

Pelaia and collaborators emphasized the clinical efficacy of benralizumab in terms of lung function in real life after the first administration of this mAb. 208 Padilla‐Galo et al reported an improvement in FEV1 after three months of treatment with benralizumab, which lasted up to six months. 209 Similar results were obtained in a retrospective study. 210 The authors ascribed the rapid improvement of lung function to the early effects of the mAb on peripheral blood and bronchial eosinophils. Although these observations were obtained in small cohorts of patients, they emphasize that the improvement caused by benralizumab on lung function observed in real life is more evident compared to certain RCTs. 73 , 203 , 204 Finally, clinical trials (NCT04365205, NCT03953300) are evaluating the effects of benralizumab on airway remodeling.

2.8. Dupilumab

The Th2‐like cytokines IL‐4 and IL‐13 and the heterodimeric IL‐4 receptor (IL‐4R) complexes that they activate play a key pathogenic role in asthma. 211 Dupilumab is a human IgG4 mAb that targets the IL‐4 receptor α chain (IL‐4Rα), common to both IL‐4R complexes: type 1 (IL‐4Rα/γc; IL‐4 specific) and type 2 (IL‐4Rα/IL‐13Rα1: IL‐4 and IL‐13 specific). 212

In several RCTs, dupilumab reduced the annualized rate of asthma exacerbations in patients with moderate‐to‐severe uncontrolled asthma compared to placebo. 213 , 214 , 215 Dupilumab in patients with severe asthma caused rapid (2 weeks) and long‐lasting improvement in FEV1 versus placebo. 214 , 215 Furthermore, the trend curves of FEV1 post‐bronchodilation showed a loss of function in the placebo group and no decrease in FEV1 over time in the dupilumab group. Moreover, in a mouse model of asthma, dual IL‐4/IL‐13 blockade with dupilumab prevented eosinophil infiltration into lung tissue without affecting circulating eosinophils. 216 A real‐life retrospective study demonstrated that 4 weeks of treatment were necessary to achieve a significant improvement in FEV1 compared to baseline. 217 The VESTIGE study (NCT04400318), evaluating dupilumab effects on lung function and structural airway changes using functional respiratory imaging (FRI), is ongoing.

It should be noted that blood eosinophilia was reported in 4%–25% of patients in the dupilumab group compared to 0.6% in the placebo group. 215 , 218 This paradoxical effect has also been reported in patients treated with dupilumab for moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis. 219 However, transient early elevation of blood eosinophils in asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) or atopic dermatitis patients on dupilumab declined to baseline levels over time. 220

Additionally, indirect evidence of a combined anti‐inflammatory effect as well as on tissue and structural cells can be derived from the observation that all of the abovementioned anti‐Th2 cytokine or receptor antibodies have been shown to reduce the size of nasal polyposis in patients with CRSwNP. 221 , 222 , 223 , 224

2.9. Tezepelumab

Tezepelumab is a human IgG2‐λ mAb, which binds with high affinity to TSLP, an epithelial cell‐derived cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of different phenotypes of asthma. 13 TSLP, a pleiotropic cytokine overexpressed in the airway epithelium of asthmatics, 49 exerts its effects by binding to a high‐affinity heterodimeric receptor complex composed of TSLPR and IL‐7Rα. 13 TSLP concentrations are increased in BAL fluid of asthmatics, 48 and bronchial allergen challenge increases TSLP expression in the asthmatic epithelium and submucosa. Importantly, serum concentrations of TSLP are increased during asthma exacerbations. 225 Finally, TSLP induces the release of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors from HLMs. 57 TSLP can promote airway remodeling via the activation of human lung fibroblasts. 70

The FDA has recently approved tezepelumab for the treatment of severe asthma with no phenotype or biomarker limitations. Tezepelumab is the first biologic antagonizing an alarmin (i.e., TSLP), which plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of asthma. 13 , 43 The phase II PATHWAY study showed that three different doses (70 mg, 210 mg, or 280 mg s.c. every 4 weeks) of tezepelumab reduced the number of annual exacerbation rates regardless of blood eosinophil count, with a significant increase in prebronchodilator FEV1 at 52 weeks from the start of treatment compared to the placebo group. 226 These results were extended in the phase III NAVIGATOR study in which tezepelumab (210 mg s.c. every 4 weeks) reduced asthma exacerbations at Week 52 and significantly improved FEV1 regardless of peripheral blood eosinophils in adolescent and adult patients with severe uncontrolled asthma 227 although there was a trend toward a better improvement with higher eosinophil counts in subgroup analysis.

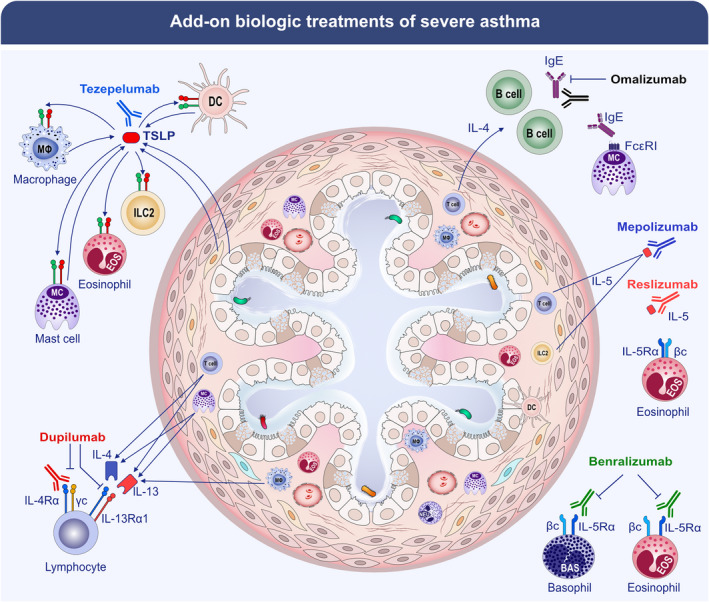

Studies conducted in different animal models using TSLP antibodies have demonstrated that TSLP blockade reduces airway inflammation, TGF‐β1 levels, hyperreactivity, and airway remodeling. 228 , 229 , 230 , 231 The phase II CASCADE study evaluated the effects of tezepelumab on airway remodeling by performing bronchoscopic biopsies in moderate‐to‐severe asthma patients. 132 Tezepelumab caused a greater reduction from baseline to the end of treatment in airway submucosal eosinophils compared to placebo. There were no other significant changes either at the level of other immune cells (neutrophils, mast cells, and T cells) and at the structural level (e.g., RBM thickness and epithelial integrity). Interestingly, tezepelumab administration was associated with lower hyperresponsiveness to mannitol inhalation compared to placebo. The latter finding was confirmed in an independent study. 232 These preliminary results on the effects of tezepelumab on airway remodeling are of translational interest for several reasons. There is overwhelming evidence that fibroblasts are a source of TSLP 58 , 59 and there is evidence that a functional TSLP signaling axis plays a role in fibrotic lung disease. 59 Figure 1 schematically illustrates the mechanisms of action of different biologics and their immunological and cellular targets in the context of airway remodeling.

FIGURE 1.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) effective in the treatment of patients with severe asthma are listed, and their known immunological mechanisms are summarized. The targets of approved add‐on biologic treatments of severe asthma include IgE (omalizumab), IL‐5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab), IL‐5 receptor (benralizumab), IL‐4/IL‐13 receptor complex (dupilumab), and TSLP (tezepelumab).

3. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

3.1. Astegolimab

Astegolimab is an IgG2 mAb that blocks IL‐33 signaling by targeting ST2, the IL‐33 receptor. 77 The phase 2b ZENYATTA study 233 evaluated the safety and efficacy of astegolimab in patients with severe asthma. Astegolimab was safe, well tolerated, and effective in reducing the annualized asthma exacerbations at Week 54. Astegolimab did not show a significant benefit compared to placebo in the absolute change in FEV1 at Week 54.

3.2. Itepekimab

Itepekimab is a human IgG4 anti‐IL‐33 mAb. A phase 2 trial compared the safety and efficacy of itepekimab (300 mg s.c. every 2 weeks), dupilumab (300 mg. s.c. every 2 weeks), itepekimab plus dupilumab, or placebo in patients with moderate‐to‐severe asthma. 234 The primary endpoint, loss of asthma control, was similar in the itepekimab (22%), combination (27%), and dupilumab (19%) groups and lower than in the placebo (41%) group. Prebronchodilator FEV1 increased with itepekimab and dupilumab monotherapies but not with combination therapy. Ipetekimab improved asthma control and quality of life compared to placebo and reduced peripheral blood eosinophils. The latter results are consistent with a role for IL‐33 in the pathogenesis of asthma exacerbations and airflow limitations in asthma. Further investigations are needed to investigate whether blockade of the IL‐33/ST2 axis can modify airway remodeling in patients with asthma.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Immunotherapy with mAbs targeting IgE, several cytokines, or their receptors has revolutionized the treatment landscape for patients with severe asthma. mAbs that block IgE (omalizumab), the IL‐5/IL‐5Rα axis (mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab), IL‐4Rα (dupilumab), or TSLP (tezepelumab) can produce durable responses in the majority of patients with severe asthma.

Airway remodeling is a cardinal feature of bronchial asthma and is responsible for structural alterations of the airways and lung parenchyma, determining airway hyperresponsiveness and the development of fixed airflow obstruction. 15 Damaged epithelial barrier, 235 , 236 subepithelial matrix proteins and collagen deposition, 24 , 25 , 29 infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells, 115 , 124 , 133 goblet cell metaplasia, 23 overexpression of inflammatory angiogenesis, 16 , 17 and hyperplasia and hypertrophy of ASM cells 18 , 33 are major features of airway remodeling in asthma. 41 , 237

At present, we have incomplete knowledge on the short‐ and long‐term effects of biological therapies on airway remodeling in asthma. However, biological therapies targeting IgE, IL‐5/IL‐5Rα, IL‐4Rα, TSLP, and IL‐33/ST2 can improve not only clinical symptoms but also certain indirect features (e.g., FEV1) of airway remodeling in asthma. 215 , 226 , 238 , 239 , 240 , 241 These findings allow us to speculate that biologics could promote the resolution of allergic and non‐allergic inflammation. Late phases of airway remodeling are associated with infiltration/activation of both profibrotic immune cells (e.g., mast cells, eosinophils, and macrophages) and structural cells (e.g., fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, ASM cells, and endothelial cells). Biologics may have late effects on immune and structural cells in addition to early effects on airway inflammation. The effects of each biologic on specific features of airway remodeling are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Effects of biologics on specific features of airway remodeling

| Biologics | Form | Target | Biological effects | Effects on airway remodeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab | Humanized IgG1‐κ mAb | IgE |

|

|

| Reslizumab | Humanized IgG4‐κ mAb | IL‐5 | Blockage of IL‐5/IL‐5R binding |

|

| Mepolizumab | Humanized IgG1‐κ mAb | IL‐5 | Blockage of IL‐5/IL‐5R binding |

|

| Benralizumab | Humanized IgG1‐κ mAb | IL‐5 receptor (IL‐5Rα) | ↓ eosinophils and basophils via antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) |

|

| Dupilumab | Human IgG4 mAb | IL‐4 receptor α chain (IL‐4Rα) |

|

|

| Tezepelumab | Human IgG2‐λ mAb | TSLP | Blockage of TSLP/TSLPR binding |

|

Biologics are presently used for the treatment of patients with severe asthma who are likely to have a prolonged history of persistent and/or repetitive immunological insults. Repetitive or prolonged injury can lead to a pathological state of fibrosis associated with reduced lung function. Experimental studies indicate that there is a limited time window in which stopping inflammation avoids fibrosis. 242 , 243 Beyond this time window, tissue remodeling inevitably occurs even if inflammation is resolved. In this circuit, macrophages, the most abundant hematopoietic cells in the human lung parenchyma, can transition between different states, including proinflammatory, anti‐inflammatory, and profibrotic states. 244 Although there are no clinical and experimental data, we would like to speculate that perhaps early treatment of mild/moderate asthma with biologics might represent an innovative strategy to limit the irreversible airway remodeling of severe asthma. 245 On the contrary, this preventive approach might reduce the direct and indirect heavy socio‐economic consequences of severe asthma and their exacerbations thus counterbalancing the cost of biologic therapies.

There are several limitations in studying in vivo the effects of biological therapies on airway tissue remodeling in asthmatic patients. Bronchial asthma is a highly heterogeneous disorder and different forms of airway remodeling could likely underlie several asthma pheno‐/endotypes. 3 The quantitative identification of immune cells in the airway epithelium and submucosa should also take in consideration the functional heterogeneity of eosinophils, 246 macrophages, 57 , 118 , 133 mast cells, 84 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 neutrophils, 125 , 127 , 251 and basophils. 85 , 86 , 125 , 252 Considering the technical and ethical difficulties to evaluate in vivo bronchial remodeling through invasive methods, particularly in patients with severe asthma, efforts are underway to identify peripheral blood biomarkers of airway remodeling in asthma. 245

In conclusion, a deeper understanding of the immunological mechanisms of the formation of different forms of airway tissue remodeling in various asthma phenotypes is needed. The use of single‐cell transcriptomics will be of paramount importance to chart the cellular landscape and specific signaling networks of upper and lower airways in healthy and asthmatic subjects. 133 , 154 The results emerging from these studies could help in the generation of new reliable diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic approaches to improve asthma treatment.

Funding information

This work was supported in part by grants from the CISI‐Lab Project (University of Naples Federico II), TIMING Project and Campania Bioscience (Regione Campania) to G.V.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

G.V., S.F., J.P., R.P., and G.S. have not potential conflicts of interest to declare. J.C.V. is a full time employee of the University of Rostock as a full time professor and chair of the Departments of Pneumology and Intensive Care Medicine has given independent advice, lectured for and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Avontec, Bayer, Bencard, Bionorica, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Chiesi, Essex/Schering‐Plough, GSK, Janssen‐Cilag, Leti, MEDA, Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Altana, Pfizer, Revotar, Sandoz‐Hexal, Stallergens, TEVA, UCB/Schwarz‐Pharma, Zydus/Cadila, has participated in advisory boards for Avontec, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Chiesi, Essex/Schering‐Plough, GSK, Janssen‐Cilag, MEDA, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Revotar, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis, Sandoz‐Hexal, TEVA, UCB/Schwarz‐Pharma and has received research grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft, Land Mecklenburg‐Vorpommern, GSK, MSD. E.H. received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Novartis, GSK, Circassia, Nestlè Purina, Stallergenes‐Greer outside the submitted work. G.W.C. received honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, Stallergenes, Greer, Hal Allergy, Menarini, Chiesi, Mylan, Valeas, Faes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Gjada Criscuolo for her excellent managerial assistance in preparing this manuscript and the administrative staff (Dr. Roberto Bifulco, Dr. Anna Ferraro, and Dr. Maria Cristina Fucci), without whom it would not be possible to work as a team. Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Varricchi G, Ferri S, Pepys J, et al. Biologics and airway remodeling in severe asthma. Allergy. 2022;77:3538‐3552. doi: 10.1111/all.15473

References

- 1. Barnes PJ. Targeting cytokines to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(7):454‐466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GINA . 2021.

- 3. Wenzel SE. Severe adult asthmas: integrating clinical features, biology, and therapeutics to improve outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(7):809‐821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGregor MC, Krings JG, Nair P, Castro M. Role of biologics in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(4):433‐445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nair P, Surette MG, Virchow JC. Neutrophilic asthma: misconception or misnomer? Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(5):441‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heaney LG, de Llano LP, Al‐Ahmad M, et al. Eosinophilic and noneosinophilic asthma: an expert consensus framework to characterize phenotypes in a global real‐life severe asthma cohort. Chest. 2021;160(3):814‐830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suehs CM, Menzies‐Gow A, Price D, et al. Expert consensus on the tapering of oral corticosteroids for the treatment of asthma. A Delphi study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(7):871‐881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Settipane RA, Kreindler JL, Chung Y, Tkacz J. Evaluating direct costs and productivity losses of patients with asthma receiving GINA 4/5 therapy in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(6):564‐572.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartemes KR, Kita H. Dynamic role of epithelium‐derived cytokines in asthma. Clin Immunol. 2012;143(3):222‐235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):57‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borowczyk J, Shutova M, Brembilla NC, Boehncke WH. IL‐25 (IL‐17E) in epithelial immunology and pathophysiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(1):40‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Varricchi G, Pecoraro A, Marone G, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin isoforms, inflammatory disorders, and cancer. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johansson K, McSorley HJ. Interleukin‐33 in the developing lung‐Roles in asthma and infection. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(5):503‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu G, Philp AM, Corte T, et al. Therapeutic targets in lung tissue remodelling and fibrosis. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;225:107839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoshino M, Takahashi M, Aoike N. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and angiogenin immunoreactivity in asthmatic airways and its relationship to angiogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(2):295‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chetta A, Zanini A, Foresi A, et al. Vascular component of airway remodeling in asthma is reduced by high dose of fluticasone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(5):751‐757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yick CY, Ferreira DS, Annoni R, et al. Extracellular matrix in airway smooth muscle is associated with dynamics of airway function in asthma. Allergy. 2012;67(4):552‐559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elliot JG, Jones RL, Abramson MJ, et al. Distribution of airway smooth muscle remodelling in asthma: relation to airway inflammation. Respirology. 2015;20(1):66‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doucet C, Brouty‐Boyé D, Pottin‐Clemenceau C, Jasmin C, Canonica GW, Azzarone B. IL‐4 and IL‐13 specifically increase adhesion molecule and inflammatory cytokine expression in human lung fibroblasts. Int Immunol. 1998;10(10):1421‐1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pascual RM, Peters SP. Airway remodeling contributes to the progressive loss of lung function in asthma: an overview. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(3):477‐486. quiz 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bergeron C, Boulet LP. Structural changes in airway diseases: characteristics, mechanisms, consequences, and pharmacologic modulation. Chest. 2006;129(4):1068‐1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hauber HP, Foley SC, Hamid Q. Mucin overproduction in chronic inflammatory lung disease. Can Respir J. 2006;13(6):327‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hough KP, Curtiss ML, Blain TJ, et al. Airway remodeling in asthma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bourdin A, Neveu D, Vachier I, Paganin F, Godard P, Chanez P. Specificity of basement membrane thickening in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1367‐1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dolhnikoff M, da Silva LF, de Araujo BB, et al. The outer wall of small airways is a major site of remodeling in fatal asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1090‐7‐1097.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chakir J, Shannon J, Molet S, et al. Airway remodeling‐associated mediators in moderate to severe asthma: effect of steroids on TGF‐beta, IL‐11, IL‐17, and type I and type III collagen expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1293‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slats AM, Janssen K, Van Schadewijk A, et al. Expression of smooth muscle and extracellular matrix proteins in relation to airway function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(5):1196‐1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu G, Cooley MA, Nair PM, et al. Airway remodelling and inflammation in asthma are dependent on the extracellular matrix protein fibulin‐1c. J Pathol. 2017;243(4):510‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roche WR, Williams J, Beasley R, Holgate S. Subepithelial fibrosis in the bronchi of asthmatics. Lancet. 1989;1(8637):520‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mostaco‐Guidolin LB, Osei ET, Ullah J, et al. Defective fibrillar collagen organization by fibroblasts contributes to airway remodeling in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(4):431‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ito JT, Lourenço JD, Righetti RF, Tibério IF, Prado CM, Lopes FD. Extracellular matrix component remodeling in respiratory diseases: what has been found in clinical and experimental studies? Cells. 2019;8(4):342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Howarth PH, Knox AJ, Amrani Y, Tliba O, Panettieri RA Jr, Johnson M. Synthetic responses in airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(2 Suppl):S32‐S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prakash YS. Emerging concepts in smooth muscle contributions to airway structure and function: implications for health and disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311(6):L1113‐L1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yap HM, Israf DA, Harith HH, Tham CL, Sulaiman MR. Crosstalk between signaling pathways involved in the regulation of airway smooth muscle cell hyperplasia. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheng W, Yan K, Xie LY, et al. MiR‐143‐3p controls TGF‐beta1‐induced cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production in airway smooth muscle via negative regulation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells 1. Mol Immunol. 2016;78:133‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harkness LM, Weckmann M, Kopp M, Becker T, Ashton AW, Burgess JK. Tumstatin regulates the angiogenic and inflammatory potential of airway smooth muscle extracellular matrix. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(12):3288‐3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holgate ST. Pathogenesis of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(6):872‐897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cazes E, Giron‐Michel J, Baouz S, et al. Novel anti‐inflammatory effects of the inhaled corticosteroid fluticasone propionate during lung myofibroblastic differentiation. J Immunol. 2001;167(9):5329‐5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Winkler T, Frey U. Airway remodeling: shifting the trigger point for exacerbations in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(3):710‐712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boulet LP. Airway remodeling in asthma: update on mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(1):56‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. James AL, Wenzel S. Clinical relevance of airway remodelling in airway diseases. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(1):134‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marone G, Spadaro G, Braile M, et al. Tezepelumab: a novel biological therapy for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(11):931‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Molofsky AB, Savage AK, Locksley RM. Interleukin‐33 in tissue homeostasis, injury, and inflammation. Immunity. 2015;42(6):1005‐1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grainge C, Dennison P, Lau L, Davies D, Howarth P. Asthmatic and normal respiratory epithelial cells respond differently to mechanical apical stress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(4):477‐480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allakhverdi Z, Comeau MR, Jessup HK, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(2):253‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang W, Li Y, Lv Z, et al. Bronchial allergen challenge of patients with atopic asthma triggers an alarmin (IL‐33, TSLP, and IL‐25) response in the airways epithelium and submucosa. J Immunol. 2018;201(8):2221‐2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li Y, Wang W, Lv Z, et al. Elevated expression of IL‐33 and TSLP in the airways of human asthmatics in vivo: a potential biomarker of severe refractory disease. J Immunol. 2018;200(7):2253‐2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shikotra A, Choy DF, Ohri CM, et al. Increased expression of immunoreactive thymic stromal lymphopoietin in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(1):104, e1‐9‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smelter DF, Sathish V, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Vassallo R, Prakash Y. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin in cigarette smoke‐exposed human airway smooth muscle. J Immunol. 2010;185(5):3035‐3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nakamura Y, Miyata M, Ohba T, et al. Cigarette smoke extract induces thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression, leading to T(H)2‐type immune responses and airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(6):1208‐1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kouzaki H, O'Grady SM, Lawrence CB, Kita H. Proteases induce production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by airway epithelial cells through protease‐activated receptor‐2. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):1427‐1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee HC, Headley MB, Loo YM, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is induced by respiratory syncytial virus‐infected airway epithelial cells and promotes a type 2 response to infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(5):1187‐1196.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kato A, Favoreto S, Avila PC, Schleimer RP. TLR3‐ and Th2 cytokine‐dependent production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):1080‐1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lai JF, Thompson LJ, Ziegler SF. TSLP drives acute TH2‐cell differentiation in lungs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(6):1406‐1418 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kaur D, Doe C, Woodman L, et al. Mast cell‐airway smooth muscle crosstalk: the role of thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Chest. 2012;142(1):76‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Braile M, Fiorelli A, Sorriento D, et al. Human lung‐resident macrophages express and are targets of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in the tumor microenvironment. Cells. 2021;10(8):2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kang JH, Yang HW, Park JH, et al. Lipopolysaccharide regulates thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression via TLR4/MAPK/Akt/NF‐kappaB‐signaling pathways in nasal fibroblasts: differential inhibitory effects of macrolide and corticosteroid. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(2):144‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Datta A, Alexander R, Sulikowski MG, et al. Evidence for a functional thymic stromal lymphopoietin signaling axis in fibrotic lung disease. J Immunol. 2013;191(9):4867‐4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tsilingiri K, Fornasa G, Rescigno M. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: to cut a long story short. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3(2):174‐182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Harada M, Hirota T, Jodo AI, et al. Functional analysis of the thymic stromal lymphopoietin variants in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(3):368‐374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dong H, Hu Y, Liu L, et al. Distinct roles of short and long thymic stromal lymphopoietin isoforms in house dust mite‐induced asthmatic airway epithelial barrier disruption. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wu J, Dong F, Wang RA, et al. Central role of cellular senescence in TSLP‐induced airway remodeling in asthma. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Soumelis V, Reche PA, Kanzler H, et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(7):673‐680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ito T, Wang YH, Duramad O, et al. TSLP‐activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2005;202(9):1213‐1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Toki S, Goleniewska K, Zhang J, et al. TSLP and IL‐33 reciprocally promote each other's lung protein expression and ILC2 receptor expression to enhance innate type‐2 airway inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1606‐1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Camelo A, Rosignoli G, Ohne Y, et al. IL‐33, IL‐25, and TSLP induce a distinct phenotypic and activation profile in human type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Blood Adv. 2017;1(10):577‐589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cai LM, Zhou YQ, Yang LF, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induced early stage of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in human bronchial epithelial cells through upregulation of transforming growth factor beta 1. Exp Lung Res. 2019;45(8):221‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brunetto E, De Monte L, Balzano G, et al. The IL‐1/IL‐1 receptor axis and tumor cell released inflammasome adaptor ASC are key regulators of TSLP secretion by cancer associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cao L, Liu F, Liu Y, et al. TSLP promotes asthmatic airway remodeling via p38‐STAT3 signaling pathway in human lung fibroblast. Exp Lung Res. 2018;44(6):288‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jin A, Tang X, Zhai W, et al. TSLP‐induced collagen type‐I synthesis through STAT3 and PRMT1 is sensitive to calcitriol in human lung fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2021;1868(10):119083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Redhu NS, Shan L, Movassagh H, Gounni AS. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces migration in human airway smooth muscle cells. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti‐interleukin‐5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add‐on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2128‐2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Niimi A, Matsumoto H, Takemura M, Ueda T, Nakano Y, Mishima M. Clinical assessment of airway remodeling in asthma: utility of computed tomography. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;27(1):45‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Awadh N, Müller NL, Park CS, Abboud RT, JM FG. Airway wall thickness in patients with near fatal asthma and control groups: assessment with high resolution computed tomographic scanning. Thorax. 1998;53(4):248‐253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nagarkar DR, Poposki JA, Comeau MR, et al. Airway epithelial cells activate TH2 cytokine production in mast cells through IL‐1 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(1):225‐32 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Afferni C, Buccione C, Andreone S, et al. The pleiotropic immunomodulatory functions of IL‐33 and its implications in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. de Kleer IM, Kool M, de Bruijn MJ, et al. Perinatal activation of the interleukin‐33 pathway promotes type 2 immunity in the developing lung. Immunity. 2016;45(6):1285‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Leyva‐Castillo JM, Galand C, Kam C, et al. Mechanical skin injury promotes food anaphylaxis by driving intestinal mast cell expansion. Immunity. 2019;50(5):1262‐1275.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Stier MT, Zhang J, Goleniewska K, et al. IL‐33 promotes the egress of group 2 innate lymphoid cells from the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2018;215(1):263‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Altman MC, Lai Y, Nolin JD, et al. Airway epithelium‐shifted mast cell infiltration regulates asthmatic inflammation via IL‐33 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(11):4979‐4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Guo Z, Wu J, Zhao J, et al. IL‐33 promotes airway remodeling and is a marker of asthma disease severity. J Asthma. 2014;51(8):863‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Saglani S, Lui S, Ullmann N, et al. IL‐33 promotes airway remodeling in pediatric patients with severe steroid‐resistant asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(3):676‐685 e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cristinziano L, Poto R, Criscuolo G, et al. IL‐33 and superantigenic activation of human lung mast cells induce the release of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors. Cells. 2021;10(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Marone G, Borriello F, Varricchi G, Genovese A, Granata F. Basophils: historical reflections and perspectives. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2014;100:172‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gambardella AR, Poto R, Tirelli V, et al. Differential effects of alarmins on human and mouse basophils. Front Immunol. 2022;13:894163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bankova LG, Dwyer DF, Yoshimoto E, et al. The cysteinyl leukotriene 3 receptor regulates expansion of IL‐25‐producing airway brush cells leading to type 2 inflammation. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(28):eaat9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ualiyeva S, Lemire E, Aviles EC, et al. Tuft cell‐produced cysteinyl leukotrienes and IL‐25 synergistically initiate lung type 2 inflammation. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(66):eabj0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yi L, Cheng D, Zhang K, et al. Intelectin contributes to allergen‐induced IL‐25, IL‐33, and TSLP expression and type 2 response in asthma and atopic dermatitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(6):1491‐1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Beale J, Jayaraman A, Jackson DJ, et al. Rhinovirus‐induced IL‐25 in asthma exacerbation drives type 2 immunity and allergic pulmonary inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(256):256ra134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mjosberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, et al. Human IL‐25‐ and IL‐33‐responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(11):1055‐1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Xu X, Luo S, Li B, Dai H, Zhang J. IL‐25 contributes to lung fibrosis by directly acting on alveolar epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2019;244(9):770‐780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Letuve S, Lajoie‐Kadoch S, Audusseau S, et al. IL‐17E upregulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in lung fibroblasts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(3):590‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hams E, Armstrong ME, Barlow JL, et al. IL‐25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells induce pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(1):367‐372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Yao XJ, Huang KW, Li Y, et al. Direct comparison of the dynamics of IL‐25‐ and 'allergen'‐induced airways inflammation, remodelling and hypersensitivity in a murine asthma model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44(5):765‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Halwani R, Al‐Muhsen S, Al‐Jahdali H, Hamid Q. Role of transforming growth factor‐beta in airway remodeling in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(2):127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kardas G, Daszyńska‐Kardas A, Marynowski M, Brząkalska O, Kuna P, Panek M. Role of platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF) in asthma as an immunoregulatory factor mediating airway remodeling and possible pharmacological target. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Batra V, Musani AI, Hastie AT, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF)‐beta1, TGF‐beta2, interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐13 after segmental allergen challenge and their effects on alpha‐smooth muscle actin and collagen III synthesis by primary human lung fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(3):437‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hackett TL. Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in the pathophysiology of airway remodelling in asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(1):53‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wen FQ, Liu XD, Terasaki Y, et al. Interferon‐gamma reduces interleukin‐4‐ and interleukin‐13‐augmented transforming growth factor‐beta2 production in human bronchial epithelial cells by targeting Smads. Chest. 2003;123(3 Suppl):372S‐373S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Dolgachev V, Berlin AA, Lukacs NW. Eosinophil activation of fibroblasts from chronic allergen‐induced disease utilizes stem cell factor for phenotypic changes. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(1):68‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Tanaka H, Komai M, Nagao K, et al. Role of interleukin‐5 and eosinophils in allergen‐induced airway remodeling in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(1):62‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Booth BW, Sandifer T, Martin EL, Martin LD. IL‐13‐induced proliferation of airway epithelial cells: mediation by intracellular growth factor mobilization and ADAM17. Respir Res. 2007;8:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Malavia NK, Mih JD, Raub CB, Dinh BT, George SC. IL‐13 induces a bronchial epithelial phenotype that is profibrotic. Respir Res. 2008;9:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Marone G, Granata F, Pucino V, et al. The intriguing role of interleukin 13 in the pathophysiology of asthma. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ouyang Y, Miyata M, Hatsushika K, et al. TGF‐beta signaling may play a role in the development of goblet cell hyperplasia in a mouse model of allergic rhinitis. Allergol Int. 2010;59(3):313‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Samitas K, Delimpoura V, Zervas E, Gaga M. Anti‐IgE treatment, airway inflammation and remodelling in severe allergic asthma: current knowledge and future perspectives. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(138):594‐601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Pandey V, Mihara S, Fensome‐Green A, Bolsover S, Cockcroft S. Monomeric IgE stimulates NFAT translocation into the nucleus, a rise in cytosol Ca2+, degranulation, and membrane ruffling in the cultured rat basophilic leukemia‐2H3 mast cell line. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4048‐4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Matsuda K, Piliponsky AM, Iikura M, et al. Monomeric IgE enhances human mast cell chemokine production: IL‐4 augments and dexamethasone suppresses the response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(6):1357‐1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Roth M, Zhao F, Zhong J, Lardinois D, Tamm M. Serum IgE induced airway smooth muscle cell remodeling is independent of allergens and is prevented by omalizumab. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Varricchi G, Bagnasco D, Borriello F, Heffler E, Canonica GW. Interleukin‐5 pathway inhibition in the treatment of eosinophilic respiratory disorders: evidence and unmet needs. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;16(2):186‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Patella V, De Crescenzo G, Marinò I, et al. Eosinophil granule proteins activate human heart mast cells. J Immunol. 1996;157(3):1219‐1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Marone G, Galdiero MR, Pecoraro A, et al. Prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonists in allergic disorders: safety, efficacy, and future perspectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(1):73‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Marcella S, Petraroli A, Braile M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factors and angiopoietins as new players in mastocytosis. Clin Exp Med. 2021;21(3):415‐427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Flood‐Page P, Menzies‐Gow A, Phipps S, et al. Anti‐IL‐5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(7):1029‐1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Braile M, Cristinziano L, Marcella S, et al. LPS‐mediated neutrophil VEGF‐A release is modulated by cannabinoid receptor activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;109(3):621‐631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Byrne AJ, Mathie SA, Gregory LG, Lloyd CM. Pulmonary macrophages: key players in the innate defence of the airways. Thorax. 2015;70(12):1189‐1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Balestrieri B, Granata F, Loffredo S, et al. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of low‐density and high‐density human lung macrophages. Biomedicines. 2021;9(5):505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Balhara J, Gounni AS. The alveolar macrophages in asthma: a double‐edged sword. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5(6):605‐609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Staiano RI, Loffredo S, Borriello F, et al. Human lung‐resident macrophages express CB1 and CB2 receptors whose activation inhibits the release of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;99(4):531‐540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Varricchi G, Rossi FW, Galdiero MR, et al. Physiological roles of mast cells: collegium internationale allergologicum update 2019. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(4):247‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Compton SJ, Cairns JA, Holgate ST, Walls AF. The role of mast cell tryptase in regulating endothelial cell proliferation, cytokine release, and adhesion molecule expression: tryptase induces expression of mRNA for IL‐1 beta and IL‐8 and stimulates the selective release of IL‐8 from human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161(4):1939‐1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Ardi VC, Kupriyanova TA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP‐free MMP‐9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(51):20262‐20267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Ventura I, Vega A, Chacon P, et al. Neutrophils from allergic asthmatic patients produce and release metalloproteinase‐9 upon direct exposure to allergens. Allergy. 2014;69(7):898‐905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Loffredo S, Borriello F, Iannone R, et al. Group V secreted phospholipase A2 induces the release of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors by human neutrophils. Front Immunol. 2017;8:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Varricchi G, Modestino L, Poto R, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophil‐derived mediators as possible biomarkers in bronchial asthma. Clin Exp Med. 2021;22(2):285‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Cristinziano L, Modestino L, Antonelli A, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021;79:91‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Poto R, Cristinziano L, Modestino L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps, angiogenesis and cancer. Biomedicines. 2022;10(2):431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Sammarco G, Varricchi G, Ferraro V, et al. Mast cells, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in human gastric cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Varricchi G, Loffredo S, Bencivenga L, et al. Angiopoietins, vascular endothelial growth factors and secretory phospholipase A2 in ischemic and non‐ischemic heart failure. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Zheng J, Wu Q, Zou Y, Wang M, He L, Guo S. Respiratory microbiota profiles associated with the progression from airway inflammation to remodeling in mice with OVA‐induced asthma. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:723152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Diver S, Khalfaoui L, Emson C, et al. Effect of tezepelumab on airway inflammatory cells, remodelling, and hyperresponsiveness in patients with moderate‐to‐severe uncontrolled asthma (CASCADE): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(11):1299‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Vieira Braga FA, Kar G, Berg M, et al. A cellular census of human lungs identifies novel cell states in health and in asthma. Nat Med. 2019;25(7):1153‐1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Hoshino M, Ohtawa J, Akitsu K. Effect of treatment with inhaled corticosteroid on serum periostin levels in asthma. Respirology. 2016;21(2):297‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Gorska K, Korczynski P, Mierzejewski M. Comparison of endobronchial ultrasound and high resolution computed tomography as tools for airway wall imaging in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2016;117:131‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Hartley RA, Barker BL, Newby C, et al. Relationship between lung function and quantitative computed tomographic parameters of airway remodeling, air trapping, and emphysema in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a single‐center study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(5):1413‐1422.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Ash SY, Rahaghi FN, Come CE, et al. Pruning of the pulmonary vasculature in asthma. The Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(1):39‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Eddy RL, Svenningsen S, Kirby M, et al. Is computed tomography airway count related to asthma severity and airway structure and function? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):923‐933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Hoshino M, Ohtawa J. Effects of adding omalizumab, an anti‐immunoglobulin E antibody, on airway wall thickening in asthma. Respiration. 2012;83(6):520‐528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Tajiri T, Niimi A, Matsumoto H, et al. Comprehensive efficacy of omalizumab for severe refractory asthma: a time‐series observational study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(4):470‐475.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Haldar P, Brightling CE, Singapuri A, et al. Outcomes after cessation of mepolizumab therapy in severe eosinophilic asthma: a 12‐month follow‐up analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):921‐923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Haldar P, Brightling C, Hargadon B. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Przybyszowski M, Gross‐Sondej I, Zarychta J, et al. Late Breaking Abstract—the impact of treatment with mepolizumab on airway remodeling in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Eur Res J. 2021;58:PA894. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Zha W, Kruger SJ, Cadman RV, et al. Regional heterogeneity of lobar ventilation in asthma using hyperpolarized helium‐3 MRI. Acad Radiol. 2018;25(2):169‐178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Mummy DG, Kruger SJ, Zha W, et al. Ventilation defect percent in helium‐3 magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker of severe outcomes in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(3):1140‐1141.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Svenningsen S, Eddy RL, Lim HF, Cox PG, Nair P, Parraga G. Sputum eosinophilia and magnetic resonance imaging ventilation heterogeneity in severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(7):876‐884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Mummy DG, Carey KJ, Evans MD, et al. Ventilation defects on hyperpolarized helium‐3 MRI in asthma are predictive of 2‐year exacerbation frequency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(4):831‐839 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Nishimoto K, Karayama M, Inui N, et al. Relationship between fraction of exhaled nitric oxide and airway morphology assessed by three‐dimensional CT analysis in asthma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Franks TJ, Colby TV, Travis WD, et al. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(7):763‐766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Reyfman PA, Walter JM, Joshi N, et al. Single‐cell transcriptomic analysis of human lung provides insights into the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1517‐1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, et al. Single‐cell RNA‐seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung‐resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv. 2020;6(28):eaba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Paul F, Arkin YA, Giladi A, et al. Transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors. Cell. 2015;163(7):1663‐1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Villani AC, Satija R, Reynolds G, et al. Single‐cell RNA‐seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science. 2017;356(6335):eaah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]