Abstract

Modern genetic approaches in animal models have unveiled novel itch‐specific neural pathways, emboldening a paradigm in which drugs can be developed to selectively and potently target itch in a variety of chronic pruritic conditions. In recent years, kappa‐opioid receptors (KORs) and mu‐opioid receptors (MORs) have been implicated in both the suppression and promotion of itch, respectively, by acting on both the peripheral and central nervous systems. The precise mechanisms by which agents that modulate these pathways alleviate itch remains an active area of investigation. Notwithstanding this, a number of agents have demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials that influence both KOR and MOR signalling. Herein, we summarize a number of opioid receptor modulators in development and their promising efficacy across a number of chronic pruritic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis, uremic pruritus and beyond.

Keywords: afferent, atopic, dermatitis, dynorphins, histamine, neurons, opioid, receptors, spinal cord

1. THE CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR BASIS OF PRURITUS

Pruritus, or itch, is defined as an uncomfortable sensation that causes a desire to scratch. In its acute form, the itch‐scratch reflex is considered an evolutionarily conserved mechanism by which the mammalian host rapidly senses noxious (itch) environmental stimuli (e.g. toxic plants, parasites) for mechanical removal (scratch) from the skin. 1 , 2 , 3 However, if itch lasts >6 weeks, it is defined as chronic pruritus and considered pathologic. Chronic itch has a prevalence of approximately 15% and is associated with numerous inflammatory skin disorders 4 ; it may also be triggered by neuropathic processes or organ dysfunction (e.g. cholestatic or uremic pruritus) or be idiopathic in nature (e.g. chronic pruritus of unknown origin). 5 , 6 While largely considered a pathology of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), there is a strong belief that chronic itch also leads to central sensitization, a process whereby the perception of itch is heightened over time in the brain. 5

Sensation in the skin arises in response to a variety of external or endogenous triggers which elicit perceptions such as touch (mechanoreception), pain (nociception) and itch (pruriception); these processes are mediated by the somatosensory nervous system within the PNS. Upon stimulation of a sensory nerve in the skin, an action potential is generated and relayed to the neurons in the spinal cord; subsequent release of neurotransmitters then results in the activation of projection neurons to the brain where itch is ultimately perceived. 6 At the cellular level, individual peripheral nerve fibres are classified on the basis of the diameter and speed of transmission into Aβ, Aδ and C nerve fibres. Functionally, Aβ fibres transmit mechanosensations such as touch, pressure and/or vibration, while Aδ fibres also relay some forms of pain. Unmyelinated C fibres, the slowest and smallest of the group, are polymodal in nature and transmit a variety of thermal, pain and itch sensations. 6 Thus, the physical properties of the nerves, in part, are predictive of their functions.

Major recent discoveries in our understanding of itch neurobiology suggest that multiple itch‐specific molecules, and even neurons (pruriceptors), exist. Beyond the major peripheral pruritogen histamine, several other endogenous pruritogenic molecules have been identified in the periphery, including a number of cytokines that promote nonhistaminergic itch. 6 Thus, blocking the ability of pruritogens to bind itch‐sensory neurons is now an important therapeutic strategy for conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD); however, to date, only one agent with a putative neuromodulatory property has been approved by the FDA specifically for chronic itch associated with chronic kidney disease (i.e. KORSUVA™ [difelikefalin]). 7 Herein, we describe how various endogenous opioid pathways may be targeted for the development of new anti‐itch treatments.

2. OPIOID RECEPTOR STRUCTURE, FUNCTION AND OVERALL DISTRIBUTION

Opioid receptors are members of a large class of evolutionarily conserved cell surface G protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs). Although expressed across a number of different cell types, opioid receptors are best known for their function on neurons. 8 , 9 Endorphins bind to mu‐opioid receptors (MORs), and activation of this pathway is the most effective approach to alleviating pain. However, it is well appreciated that the activation of MORs may actually trigger or exacerbate itch. 10 , 11 In contrast, the kappa‐opioid receptor (KOR) pathway, which is triggered by endogenous dynorphins, activates sensory neurons to suppress both pain and itch. 12 In mice, aversive behaviours induced by the injection of chemicals that induce pain (capsaicin) and itch (chloroquine) were shown to be alleviated by both peripherally restricted and centrally penetrating KOR agonists (e.g. nalfurafine, nalbuphine). 13 , 14 Thus, the range of pain and itch sensations that can be modulated by KOR agonism remains to be fully defined.

The studies of peripheral afferent C nerve fibres in mice have helped elucidate the distribution and function of KORs in the peripheral afferent pathways involving dorsal root ganglion (DRG)‐based somatosensory neurons. 13 The endogenous KOR agonist dynorphin acts within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to inhibit itch signals from peripheral afferents. 13 , 15 More recently, it has been shown that medullary kappa‐opioid neurons suppress itch via a descending circuit. 16 KOR agonism also inhibits the development of neurogenic inflammation, as measured by inhibition of capsaicin‐induced plasma extravasation in the presence of KOR agonists. 13 Thus, collectively, there are numerous mechanisms by which KOR agonists may suppress itch from the periphery to the brain.

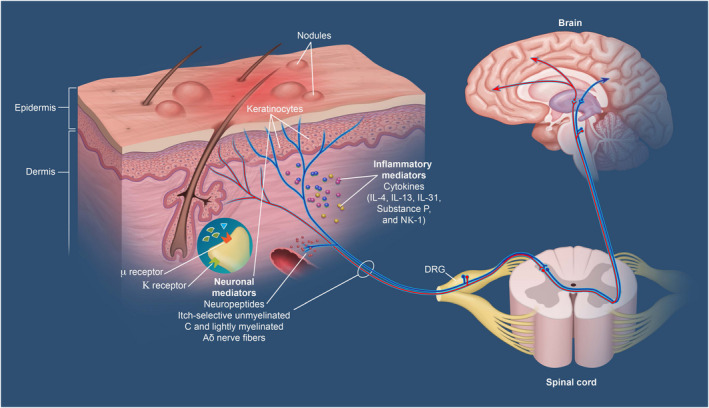

Although MORs are expressed on C fibres that contain itch‐sensory neurons, it has been shown that KORs, in addition to being reported on C fibres, are expressed on Aβ fibres as well, which generally do not mediate itch. 13 Itch sensations propagate via action potentials from peripheral dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons by synapsing directly on spinal neurons in a pathway‐specific manner (Figure 1). 6 , 17 , 18 Both chemical and mechanical itch pathways involve multiple spinal interneuron types, including those that provide a “gating” function that regulates multiple signals from the periphery within the spinal cord. 6 , 17 , 19 , 20 Thus, one possible interplay between the MOR and KOR pathways in itch is that, while MOR stimulation can promote itch, KOR transmission gates out signals from MOR‐expressing nerves within the spinal cord, where both Aβ and C fibre nerves converge. However, the precise mechanisms by which MORs and KORs modulate itch remain to be more fully elucidated.

FIGURE 1.

Central and peripheral mediators in chronic pruritus. 18 KOR, kappa‐opioid receptor; MOR, mu‐opioid receptor

Sensitization, or lowering of the stimulus thresholds required for neuron firing, is a phenomenon common to the sensory processing of both itch and pain. 21 , 22 Sensitization may involve peripheral and central neural pathways and may be both a driver and result of various chronic itch conditions. In the context of chronic pruritus, sensitization also may involve the transduction of normally painful stimuli as itch rather than pain. In terms of mechanical itch, sensitization can result in alloknesis, whereby mechanical stimuli promote itch. 23

In addition to the PNS, KORs and MORs are broadly distributed in the spinal cord and brain 24 ; as in the PNS, activation of central MORs has been generally associated with promoting itch, while the activation of central KORs can suppress itch. 25 However, the mechanisms may be different in the central nervous system (CNS) in terms of how itch is modulated compared with the PNS. In the spinal cord, studies in mice have shown that loss of a subset of spinal Bhlhb5‐expressing interneurons (known as B5‐I neurons) results in excessive scratching behaviour. 26 Strikingly, this small but important population of B5‐I neurons expresses the endogenous KOR ligand dynorphin. Importantly, scratching behaviour caused by a variety of itch‐inducing factors in Bhlhb5 knockout mice was attenuated with treatment with nalfurafine and other KOR agonists. 15 Taken together, these studies demonstrate the importance of KOR pathways within the spinal cord in suppressing itch.

Although the spinal pathways for mechanical itch in mice are not as well characterized as those for chemical itch, inhibitory interneurons expressing neuropeptide Y (NPY+ neurons) appear to provide gating of mechanical itch analogous to that provided by the B5‐I neurons for chemical itch. Ablation or inactivation of these NPY+ neurons leads to spontaneous scratching behaviour or enhancement of light touch‐induced scratching or alloknesis. 19

From the spinal cord, itch sensations are carried to the brain by spinal projection neurons via axons that are thought to cross the midline and ultimately join spinothalamic tracts leading to the thalamus and parabrachial nucleus. 6 , 17 , 27 Although detailed mapping of these pathways and the involved neurons remains to be performed, there is evidence that the ascending transmission of different itch stimuli remains pathway specific; projection neurons bearing the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R+ neurons) appear to transmit chemical itch, but not mechanical itch, sensations. 6 , 28 However, the ways that MOR and KOR signalling ultimately influence these ascending pathways are poorly understood and constitutes an important area of future study.

In the brain, it is believed that chronic pruritus can be attenuated by reducing cravings to scratch and the associated rewarding stimuli resulting from such behaviour. 29 In other words, the central hypothesis is that by limiting the pleasurable sensations triggered by endogenous opioid pathways elicited by scratching behaviour, itching and subsequent scratching behaviour can be attenuated. 30 , 31 Experimental support for the role of opioid receptors in this area has principally come from a functional MRI study in humans in which the combined KOR agonist/MOR antagonist butorphanol significantly decreased brain activity in these regions, concurrent with itch suppression. 32 Therefore, disrupting the “itch‐scratch cycle” by reducing cravings, reward and the pleasurable feelings associated with scratching may be achieved by targeting opioid receptors in the CNS, 31 although additional research in this area is required to validate this mechanism. However, it is evident that KOR agonism and MOR antagonism represent important mechanisms with the potential to suppress itch in the periphery, the spinal cord and the brain.

3. EMERGING PARADIGMS OF ITCH‐SPECIFIC PATHWAYS IN RELATION TO MOR AND KOR SIGNALLING

3.1. Peripheral itch pathways

Classically, itch has generally been divided into 2 forms, histamine‐mediated (histaminergic) and non–histamine‐mediated (nonhistaminergic). 1 However, it is well recognized now that most forms of itch are nonhistaminergic in nature. Recent single cell RNA‐sequencing (scRNA‐seq) studies have demonstrated that multiple itch‐specific neurons exist within the DRG that can be classified based on their expression of itch receptors, including receptors for histamine, serotonin, leukotrienes and various cytokines. Additionally, itch‐associated neuropeptides such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) are highly expressed within specific subsets of these neurons. 33 To date, these neurons are generally subdivided into what are described as NP1, NP2 and NP3 neurons. While the NP1 neuron expresses the itch‐associated receptor MrgprD, NP2 is known for expressing both the histamine 1 receptor (H1‐R) and the itch‐specific GPCRs MrgprA3 and MrgprC11. While NP3 can also express H1‐R, it is increasingly recognized as the itch neuron that can respond to the cytokine pruritogen IL‐31 and the receptor for the pruritogen leukotriene C4 (LTC4) called CysLTR2. 6 , 33 In addition to these emerging classifications, a variety of cytokines associated with itch in AD, such as IL‐4, IL‐13, IL‐31, IL‐33 and TSLP, have also been implicated in promoting itch at the neuronal level. 6 However, the ways in which these cytokines converge upon different itch‐sensory neurons is currently a major area of inquiry. Notwithstanding this, a number of these cytokines are known to signal through downstream Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) within itch‐sensory neurons, and this is likely the mechanism by which forthcoming JAK inhibitors derive their rapidity, breadth and potency in terms of suppressing itch. 6 , 22 However, the extent and nature of interactions between MOR and KOR signalling and the JAK/STAT pathway (and other intracellular signalling networks) remain unclear and the subject of intense exploration.

The importance of peripheral KOR signalling in itch has been reinforced by recent work in murine and canine models. The peripherally restricted KOR agonist HSK21542 significantly reduced itch intensity in a compound 48/80‐induced scratching test in mice; this compound also demonstrated substantial antinociceptive and antiallodynic effects. 34 In a canine AD model employing house dust mite antigen, topical application of the KOR agonist asimadoline substantially reduced dermatitis severity but not pruritus severity, suggesting that its effects may be mediated peripherally at least in part via suppression of inflammation. 35

4. KAPPA‐OPIOID RECEPTORS AND MORS AS THERAPEUTIC TARGETS IN CHRONIC PRURITUS

With respect to KOR and MOR function as part of the itch signalling pathways, observations of the effects of KOR and MOR activation on itch perception more generally support these results. In addition to its well‐known analgesic effects, MOR agonism has consistently been associated with increased pruritus, as commonly seen in the intrathecal administration of morphine or other MOR agonists (spinal block) during labour and delivery. The reported incidence of pruritus as an adverse event following neuraxial administration of MOR agonists ranges from 30% to 100%. 10 Recently, the generation of itch by intrathecal morphine was found to be due to disinhibition of spinal dynorphin‐expressing interneurons 36 ; in contrast, itch generation by parenterally administered morphine appears to be the result of histamine release caused by morphine‐induced mast cell degranulation. 37

In contrast, KOR agonism and MOR antagonism (separately or in combination) have consistently been associated with reduction in itch severity; prophylactic treatment with the combination KOR agonist and MOR antagonist nalbuphine was found to significantly reduce the incidence of intrathecal opioid‐induced pruritus. 10 Moreover, in addition to the itch suppression demonstrated by dynorphin treatment of afferent low‐threshold mechanoreceptors and of B5‐I neurons, treatment with KOR agonists and/or MOR antagonists has consistently demonstrated reductions in pruritus severity. 12

Kappa‐opioid receptors agonism may also have anti‐inflammatory effects, possibly via downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression and release. 12 In addition to the inhibition of capsaicin‐induced neurogenic inflammation by the KOR agonist nalfurafine, 13 the mixed KOR agonist/MOR antagonist nalbuphine has been shown to exert anti‐inflammatory effects as well. In a mouse model of contact dermatitis, nalbuphine (pre‐administered subcutaneously) not only reduced scratching behaviour but also modulated cytokine expression. Nalbuphine treatment reduced the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine IL‐31 while increasing the expression of the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10; it also increased the dermal M1 monocyte/macrophage population involved in skin healing. 38 Although the mechanisms explaining these observations remain unknown and may involve activation of opioid receptors on non‐neuronal tissues, these observations suggest that nalbuphine may directly suppress inflammation and promote skin healing in contact dermatitis.

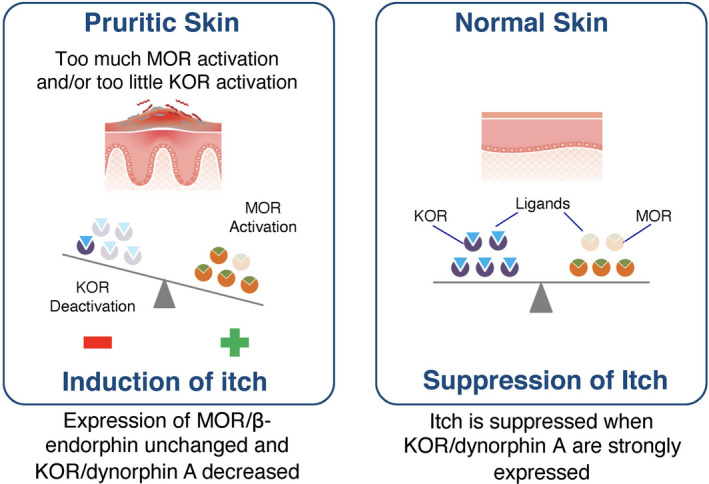

The accumulating evidence implicating dysregulated KOR and/or MOR signalling in itch has led to recent investigations into a variety of chronic itch conditions regarding the role of KORs and MORs. Both preclinical itch models and observed clinical effects of their modulation have led a number of investigators to propose that imbalances in MOR and KOR expression and signalling pathways may contribute to the development and pathophysiology of various disorders characterized by chronic pruritus (Figure 2). 12 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 This concept has received strong support from elegant mRNA sequencing (RNA‐seq) studies in humans with AD and/or psoriasis and monkeys (macaques) with itch. These studies have identified approximately 2000 genes that are differentially expressed in itchy skin compared with normal skin, including the upregulation of chemokines and cytokines and their receptors. It is important to note that in itchy skin there was upregulation of genes for the β‐endorphin precursor (POMC) and μ‐opioid receptor (OPRM1) and downregulation of genes for the dynorphin precursor (PDYN) and the dynorphin receptor (OPRK1). 47 , 48

FIGURE 2.

Imbalances of kappa‐ and mu‐opioid receptors in pruritic skin. 45

The possibility that imbalanced KOR/MOR signalling may underlie some forms of chronic itch has led to active investigation of KOR agonists and MOR antagonists in pursuit of novel treatments for severe itch conditions. 12 , 41 , 42 , 49 Several modulators of opioid receptor activity are currently being investigated as treatments for a range of chronic pruritic conditions, including KOR agonists and dual‐acting KOR agonists/MOR antagonists. Table 1 lists the opioid receptor‐targeting agents currently in clinical development for chronic pruritus, including 3 KOR agonists (asimadoline, difelikefalin and nalfurafine) and one dual‐acting KOR agonist/MOR antagonist (nalbuphine extended‐release [ER]). Difelikefalin has demonstrated efficacy in treating chronic pruritus associated with kidney failure requiring dialysis and is now FDA approved for this indication 7 ; a phase 2 trial in patients with AD‐associated pruritus, however, did not meet the primary end point in itch. 50 The MOR antagonist naltrexone has been evaluated for itch associated with AD; although new phase 2 studies have been announced, participants are not yet being recruited. 51 In addition, the dual‐acting KOR agonist/MOR antagonist butorphanol has reported anecdotal utility in chronic pruritus of various aetiologies in a case series 52 ; however, its intranasal route of administration is generally unfamiliar to dermatologists and may have hampered further development. 22 The dual‐acting KOR agonist/MOR antagonist nalbuphine ER has demonstrated efficacy in uremic pruritus, with patients receiving oral nalbuphine ER 120 mg achieving significantly greater reductions in itch severity scores than placebo. 53 Thus, which specific conditions are most amenable to the modulation of opioid pathways remain to be determined. Although a detailed review of these agents is beyond the scope of this article, we refer readers to several recent reviews. 11 , 22 , 51 It should also be noted that recent advances, most notably the elucidation of the KOR structure (alone and bound to various ligands) at atomic resolution, 54 are paving the way for rational development of new opioid receptor ligands that may permit precise receptor targeting while reducing the risk of adverse effects. 55

TABLE 1.

| Agent | Mechanism of Action | Itch‐Related Indication | ClinicalTrials.gov ID number(s)/citation (if published) | Development Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asimadoline | KOR agonist | Atopic dermatitis | NCT02475447 | Phase 2 |

| Difelikefalin (CR845) | KOR agonist | Atopic dermatitis | NCT04018027 | Phase 2 |

| Cholestatic pruritus | NCT03995212 | Phase 2 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | NCT03617536 | Phase 2 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | NCT02858726 59 | Approve | ||

| NCT03998163 | Phase 3 | |||

| NCT03636269 | Phase 3 | |||

| NCT03422653 60 | Phase 3 | |||

| Nalbuphine ER | KOR agonist/MOR antagonist | Prurigo nodularis | NCT03497975 | Phase 2/3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | NCT02143648 53 | Phase 2/3 | ||

| Nalfurafine | KOR agonist | Atopic dermatitis | NCT00980629 | Phase 2 |

| Chronic liver disease | NCT00638495 | Phase 2 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | NCT01513161 | Phase 3 | ||

| NCT00793156 61 | Phase 3 |

Abbreviations: ER, extended release; KOR, kappa‐opioid receptor; MOR, mu‐opioid receptor.

While not all opioid receptor‐targeting agents have been rigorously assessed for their abuse potential, nalfurafine for treating intractable pruritus in patients receiving haemodialysis produced no differences from control patients receiving haemodialysis with regard to multiple addiction assessments. 56 Academic research conducted on nalbuphine has found a low abuse potential, comparable with the KOR agonist/MOR antagonist pentazocine. 57 Injectable nalbuphine remains the only dual‐acting KOR agonist/MOR antagonist currently marketed in the United States that is not controlled under the Controlled Substance Act (CSA). 58 The status of the CSA scheduling for the recently approved difelikefalin formulation for uremic pruritus is not yet known.

5. MAJOR OPEN QUESTIONS

Opioid receptor signalling has been implicated in the pathophysiology of chronic itch in both preclinical and clinical settings. In addition to heterogeneity of receptor expression and function (MOR vs. KOR), there is increasing appreciation for how these pathways may influence distinct neuronal circuits in the periphery, spinal cord and brain to modulate itch. The degree to which the antipruritic efficacy and adverse‐effect profile of candidate drugs may be affected by their in vivo distribution profile (i.e. centrally penetrating versus peripherally restricted) remains to be fully defined; ongoing and future clinical studies will shed more light on how these drugs work. A major question is whether peripheral exposure to opioid receptor‐targeting agents is sufficient to provide acceptable efficacy across multiple chronic itch conditions.

A related question is whether topical, rather than systemic, delivery of opioid receptor‐modulating agents is more suitable for certain chronic itch conditions. Given that endogenous opioids can act on a variety of different cells beyond the nervous system, local delivery can have unique pharmacodynamic effects even on the same disease. As an example, oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors such as apremilast have demonstrated weaker than expected results in AD, while topical PDE4 inhibitors have demonstrated more success. However, future studies will be required to determine the differential effects of topical versus systemic delivery.

Finally, a major open issue is the degree to which types of neurons and itch‐specific signalling pathways are modulated by influencing various opioid receptor pathways. As the field of itch biology continues to expand, there will be greater understanding with regard to how MOR and KOR fit into the emerging paradigm of itch neurocircuitry. By coupling mechanistic murine studies with functional validation in humans, broader understanding of how these pathways can be best targeted to suppress itch will likely emerge to guide therapeutic development.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

The discovery of itch‐specific receptors and neurons in recent years has not only clarified the peripheral and central pathways that promote itch sensations but has also generated more interest in how pathways that suppress itch may also be targeted. In particular, the recognition that KOR signalling acts to limit itch while MOR signalling intensifies itch has led to a renewed pursuit of KOR agonism and MOR antagonism as potential approaches to treating pruritus.

While historically itch has not been viewed as a “disease” but rather a symptom of a primary disorder (e.g. AD, kidney disease), there is increasing appreciation that, by targeting itch‐specific pathways, itch can be relieved even in the absence of controlling the underlying disease. Thus, a paradigm is emerging in which itch can be viewed as a primary endpoint of interest even when the underlying condition is untreatable, poorly understood, or even entirely unknown. Thus, the opioid receptor‐targeting agents present a unique opportunity in which to advance the development of new treatments while also directly informing a better understanding of fundamental itch biology.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: GY. Study investigator, Enrolled patients and Collection and assembly of data: N/A. Data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, manuscript review and revisions and final approval of manuscript: All authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Brian Kim is a consultant for Outlook for iOS, AbbVie, ABRAX Japan, Almirall, Amagma, Arcutis, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bellus Health, Blurprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squib, Cara Therapeutics, Clexio Biosciences, Cymabay, Daewoong Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Escienct, Evommune, Galderma, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Granular Therapeutics, Janssen, Kiniksa, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Pfizer, Novartis, OM Pharma, Recens Medical, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Septerna, Third Harmonic, Trevi Therapeutics, Veradermics, and has received research grants for Cara Therapeutics and LEO Pharma. Saadet Inan, Jacek C. Szepietowski have no conflicts of interest. Sonja Ständer is an investigator for Dermasence, Kiniksa, Galderma, GSK, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Sanofi, Trevi Therapeutics and Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and is a consultant and/or member of the advisory board for Abbvie, Almirall, Beiersdorf, Bellus Health, Benevolent, Bionorica, Cara Therapeutics, Celgene, Clexio Biosciences, Escient, Galderma, Grünenthal, Kiniksa, Leo, Lilly, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Trevi Therapeutics. P.G. Unna Academy, Vifor. Thomas Sciascia is an employee of Trevi Therapeutics and conducts pharmacological investigations with nalbuphine including clinical trials in pruritus subjects. He also has granted patents on the use of nalbuphine in the treatment of pruritus. has no conflicts of interest. Gil Yosipovitch is a Scientific Advisory Board member and consultant for Pfizer, Trevi Therapeutics, Kiniksa, Regeneron, Sanofi, Galderma, Novartis, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Bellus and CeraVe and has received research funds from Pfizer, Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, Novartis, and Eli Lilly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health Company, and funded by Trevi Therapeutics, Inc.

Kim BS, Inan S, Ständer S, Sciascia T, Szepietowski JC, Yosipovitch G. Role of kappa‐opioid and mu‐opioid receptors in pruritus: Peripheral and central itch circuits. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31:1900‐1907. doi: 10.1111/exd.14669

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 2):313‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cevikbas F, Lerner EA. Physiology and pathophysiology of itch. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(3):945‐982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ständer S, Steinhoff M, Schmelz M, Weisshaar E, Metze D, Luger T. Neurophysiology of pruritus: cutaneous elicitation of itch. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(11):1463‐1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ständer S, Schäfer I, Phan NQ, et al. Prevalence of chronic pruritus in Germany: results of a cross‐sectional study in a sample working population of 11,730. Dermatology. 2010;221(3):229‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Clinical practice. Chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1625‐1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dong X, Dong X. Peripheral and central mechanisms of itch. Neuron. 2018;98(3):482‐494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korsuva (difelikefalin) [package insert]. Stamford, CT: Cara Therapeutics, Inc; 2021.

- 8. Pathan H, Williams J. Basic opioid pharmacology: an update. Br J Pain. 2012;6(1):11‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sehgal N, Smith HS, Manchikanti L. Peripherally acting opioids and clinical implications for pain control. Pain Physician. 2011;14(3):249‐258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tubog TD, Harenberg JL, Buszta K, Hestand JD. Prophylactic nalbuphine to prevent neuraxial opioid‐induced pruritus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019;34(3):491‐501. e498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Erickson S, Heul AV, Kim BS. New and emerging treatments for inflammatory itch. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(1):13‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Phan NQ, Lotts T, Antal A, Bernhard JD, Ständer S. Systemic kappa opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic pruritus: a literature review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(5):555‐560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inan S, Dun NJ, Cowan A. Antipruritic effect of nalbuphine, a kappa opioid receptor agonist, in mice: a pan antipruritic. Molecules. 2021;26(18):5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snyder LM, Chiang MC, Loeza‐Alcocer E, et al. Kappa opioid receptor distribution and function in primary afferents. Neuron. 2018;99(6):1274‐1288.e1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kardon AP, Polgár E, Hachisuka J, et al. Dynorphin acts as a neuromodulator to inhibit itch in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;82(3):573‐586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nguyen E, Smith KM, Cramer N, et al. Medullary kappa‐opioid receptor neurons inhibit pain and itch through a descending circuit. Brain. 2022;145(7):2586‐2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen XJ, Sun YG. Central circuit mechanisms of itch. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pereira MP, Steinke S, Zeidler C, et al. European academy of dermatology and venereology European prurigo project: expert consensus on the definition, classification and terminology of chronic prurigo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(7):1059‐1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bourane S, Duan B, Koch SC, et al. Gate control of mechanical itch by a subpopulation of spinal cord interneurons. Science. 2015;350(6260):550‐554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koch SC, Acton D, Goulding M. Spinal circuits for touch, pain, and itch. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:189‐217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Potenzieri C, Undem BJ. Basic mechanisms of itch. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(1):8‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fowler E, Yosipovitch G. A new generation of treatments for itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(2):adv00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng J, Luo J, Yang P, Du J, Kim BS, Hu H. Piezo2 channel‐Merkel cell signaling modulates the conversion of touch to itch. Science. 2018;360(6388):530‐533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng J, Sarkar S, Chang SL. Opioid receptor expression in human brain and peripheral tissues using absolute quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):223‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ko MC. Roles of central opioid receptor subtypes in regulating itch sensation. In: Carstens E, Akiyama T, eds. Itch: Mechanisms and Treatment. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross SE, Mardinly AR, McCord AE, et al. Loss of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord and elevated itch in Bhlhb5 mutant mice. Neuron. 2010;65(6):886‐898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fowler E, Yosipovitch G. Chronic itch management: therapies beyond those targeting the immune system. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(2):158‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Acton D, Ren X, Di Costanzo S, et al. Spinal neuropeptide Y1 receptor‐expressing neurons form an essential excitatory pathway for mechanical itch. Cell Rep. 2019;28(3):625‐639. e626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Setsu T, Hamada Y, Oikawa D, et al. Direct evidence that the brain reward system is involved in the control of scratching behaviors induced by acute and chronic itch. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;534:624‐631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papoiu AD, Nattkemper LA, Sanders KM, et al. Brain's reward circuits mediate itch relief. A functional MRI study of active scratching. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishiuji Y. Addiction and the itch‐scratch cycle. What do they have in common? Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(12):1448‐1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Papoiu ADP, Kraft RA, Coghill RC, Yosipovitch G. Butorphanol suppression of histamine itch is mediated by nucleus accumbens and septal nuclei: a pharmacological fMRI study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(2):560‐568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large‐scale single‐cell RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(1):145‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang X, Gou X, Yu X, et al. Antinociceptive and antipruritic effects of HSK21542, a peripherally‐restricted kappa opioid receptor agonist, in animal models of pain and itch. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:773204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marsella R, Ahrens K, Wilkes R, Soeberdt M, Abels C. Topical κ‐opioid receptor agonist asimadoline improves dermatitis in a canine model of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(4):628‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nguyen E, Lim G, Ding H, Hachisuka J, Ko MC, Ross SE. Morphine acts on spinal dynorphin neurons to cause itch through disinhibition. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(579):eabc3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nguyen E, Lim G, Ross SE. Evaluation of therapies for peripheral and neuraxial opioid‐induced pruritus based on molecular and cellular discoveries. Anesthesiology. 2021;135(2):350‐365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Inan S, Torres‐Huerta A, Jensen LE, Dun NJ, Cowan A. Nalbuphine, a kappa opioid receptor agonist and mu opioid receptor antagonist attenuates pruritus, decreases IL‐31, and increases IL‐10 in mice with contact dermatitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;864:172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bigliardi‐Qi M, Lipp B, Sumanovski LT, Buechner SA, Bigliardi PL. Changes of epidermal mu‐opiate receptor expression and nerve endings in chronic atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2005;210(2):91‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kupczyk P, Reich A, Hołysz M, et al. Opioid receptors in psoriatic skin: relationship with itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(5):564‐570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yosipovitch G, Rosen JD, Hashimoto T. Itch: from mechanism to (novel) therapeutic approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(5):1375‐1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pereira MP, Mittal A, Ständer S. Current treatment strategies in refractory chronic pruritus. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;46:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wieczorek A, Krajewski P, Kozioł‐Gałczyńska M, Szepietowski JC. Opioid receptors expression in the skin of haemodialysis patients suffering from uraemic pruritus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):2368‐2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lipman ZM, Yosipovitch G. Substance use disorders and chronic itch. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):148‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Komiya E, Tominaga M, Kamata Y, Suga Y, Takamori K. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of itch in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hashimoto T, Yosipovitch G. Itching as a systemic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(2):375‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nattkemper LA, Tey HL, Valdes‐Rodriguez R, et al. The genetics of chronic itch: gene expression in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with severe itch. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(6):1311‐1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nattkemper LA, Fourzali K, Yosipovitch G. Cutaneous gene expression in primates with itch. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(6):1586‐1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Snyder LM, Ross SE. Itch and its inhibition by counter stimuli. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;226:191‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cara Therapeutics . Cara Therapeutics Announces Topline Results from KARE Phase 2 Dose‐Ranging Trial of Oral KORSUVA™ in Atopic Dermatitis Patients with Moderate‐to‐Severe Pruritus; 2021. Cara Therapeutics. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://ir.caratherapeutics.com/news‐releases/news‐release‐details/cara‐therapeutics‐announces‐topline‐results‐kare‐phase‐2‐dose [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soeberdt M, Kilic A, Abels C. Small molecule drugs for the treatment of pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;881:173242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dawn AG, Yosipovitch G. Butorphanol for treatment of intractable pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(3):527‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mathur VS, Kumar J, Crawford PW, Hait H, Sciascia T. A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of nalbuphine ER tablets for uremic pruritus. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(6):450‐458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mafi A, Kim SK, Goddard WA 3rd. The atomistic level structure for the activated human κ‐opioid receptor bound to the full Gi protein and the MP1104 agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(11):5836‐5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Spetea M, Schmidhammer H. Kappa opioid receptor ligands and pharmacology: diphenethylamines, a class of structurally distinct, selective kappa opioid ligands. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;271:163‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ueno Y, Mori A, Yanagita T. One year long‐term study on abuse liability of nalfurafine in hemodialysis patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(11):823‐831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jasinski DR, Mansky PA. Evaluation of nalbuphine for abuse potential. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972;13(1):78‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nalbuphine hydrochloride (Trade Name: Nubain®) ; 2019. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/nalbuphine.pdf

- 59. Fishbane S, Mathur V, Germain MJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of difelikefalin for chronic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(5):600‐610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fishbane S, Jamal A, Munera C, Wen W, Menzaghi F. A phase 3 trial of difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):222‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kumagai H, Ebata T, Takamori K, Muramatsu T, Nakamoto H, Suzuki H. Effect of a novel kappa‐receptor agonist, nalfurafine hydrochloride, on severe itch in 337 haemodialysis patients: a phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(4):1251‐1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.