Abstract

Biomimetic metallic biomaterials prepared for bone scaffolds have drawn more and more attention in recent years. However, the topological design of scaffolds is critical to cater to multi-physical requirements for efficient cell seeding and bone regeneration, yet remains a big scientific challenge owing to the coupling of mechanical and mass-transport properties in conventional scaffolds that lead to poor control towards favorable modulus and permeability combinations. Herein, inspired by the microstructure of natural sea urchin spines, biomimetic scaffolds constructed by pentamode metamaterials (PMs) with hierarchical structural tunability were additively manufactured via selective laser melting. The mechanical and mass-transport properties of scaffolds could be simultaneously tuned by the graded porosity (B/T ratio) and the tapering level (D/d ratio). Compared with traditional metallic biomaterials, our biomimetic PM scaffolds possess graded pore distribution, suitable strength, and significant improvements to cell seeding efficiency, permeability, and impact-tolerant capacity, and they also promote in vivo osteogenesis, indicating promising application for cell proliferation and bone regeneration using a structural innovation.

Keywords: Biomimetic biomaterials, Pentamode metamaterials, Selective laser melting, Mass-transport properties, Bone scaffolds

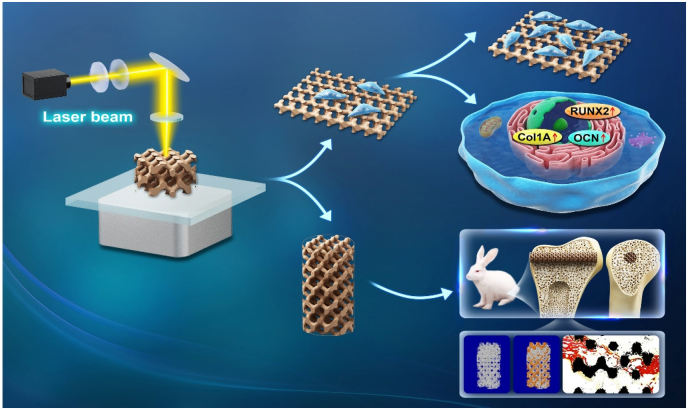

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A sea urchin spine-inspired porous scaffold with multi-physical performances was proposed.

-

•

3D printed biomimetic scaffolds presented tailored mechanical-transport properties.

-

•

The biomimetic scaffold was biocompatible and showed good osteogenesis performance.

1. Introduction

Bone and bone tissue take part in the key functions of the human body, playing an important role in the movement of the body, protection of soft tissues and internal organs, and homeostasis of mineral substances [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. To date, bone tissue engineering (BTE) is considered to have the highest potential to solve the problem of bone defects, which can avoid the disadvantage of autografts and allografts as well as possess comparable designability to cater to geometrical and biomechanical requirements [6,7]. Normally, natural bone, being a heterogeneous structure, has two basic architectures, the cortical bone at the exterior and cancellous bone in the core. The outer cortical bone is highly compact and stiff with nearly 10% porosity and 3–20 GPa Young's modulus, providing sufficient mechanical properties for supporting human movement and bearing body weight. The inner cancellous bone with 50–90% porosity and 0.1–4.5 GPa Young's modulus is an irregular network composed of beam-like and shell-like structures at about 300 μm, affording large physical space for the transport of nutrients and metabolism [8,9]. As reported, bone defects are most conspicuous in the cancellous bone area [10]. It is considered that 80% of bone remodeling activity happens in cancellous bone although cancellous bone is the most barren at 20% of the total bone mass [11]. Due to the specific bone distribution and vulnerable characteristics, it is impossible to repair cancellous bone without destroying cortical bone. Therefore, bone remodeling processes not only need to construct the cancellous bone structure but also involve partly remodeling a cortical bone structure, leading to the requirements of graded porous scaffolds.

At present, with the maturity and progress of 3D printing technology, it is possible to prepare complex and delicate scaffold structures, which promotes the development of BTE [[12], [13], [14]]. However, the present architectures of bone scaffolds, e.g. strut-based lattice structures [15,16], TPMS-based lattice structures [17,18], and Voronoi structures [19], have simple structures and coupled mechanical and mass-transport properties, which cannot be used for precisely controlling cell distribution, effectively realizing cell seeding and bone regeneration. Different from conventional structural materials, pentamode metamaterials (PMs), a kind of metamaterials, possess complex geometrical topologies and can realize multi-physical performance regulation of artificial scaffolds, due to the decoupled relative density and mechanical properties [20]. For enhanced therapeutic efficacy, crucial aspects of bone scaffold design should possess variable porosity, mechanical properties that mimic natural bone in morphology and mechanics, and the ability to moderate mass-transport properties to afford metabolic pathways. The capacity of tailoring multiple physical properties of pentamode metamaterials may provide a structural template for the design of bone scaffolds.

Through millions of years of evolution and improvement, nature has found a way to overcome the conflict between different physical properties to realize a balance for perfect multi-physical properties from the nanoscale to the microscale [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. Bionics provides a top-level solution to achieve superior synthetical physical properties by adapting and implementing natural shape, performance, and functional designs. Today, bionic structure designs have attracted much attention in conceiving high-performance bone tissue scaffolds and biomaterials, such as ultratough and ultrastrong laminated composites and layered tubular cells inspired by nacre and whale baleen, respectively [26,27], anti-wetting and self-cleaning biomaterials enlightened by rose [28], and multichannel and high-efficiency exchange channel architectures inspired by lotus root [29], etc. However, these simple biomimetic strategies only bring into play geometrical similarity and mechanical or mass-transport properties, not implementing multi-physical performance scaffolds. Constructing bone scaffolds with graded porous morphologies, matched mechanical stimulation, as well as efficient mass-transport ability, remains a challenge.

Herein, making use of the evolutionary architectures of sea urchin spines in natural organisms and combining pentamode metamaterials construction, biomimetic bone scaffolds with excellent comprehensive biological performance are proposed. This sea urchin spine-like biomimetic scaffolds were successfully fabricated by selective laser melting (SLM), a 3D printing-based technology that can realize high accuracy and sustainable control of topological features. 3D printed sea urchin spine-like biomimetic scaffolds exhibit bone-like geometrical topologies, excellent mechanical and mass-transport performances, as well as noteworthy improved osteogenic capability in vitro and in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Material preparation and scaffold fabrication

The designed porous scaffolds were fabricated from titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) powder using the laser powder bed fusion AM technique (EOS M280 machine, Germany). The particle diameter of Ti6Al4V powder ranges between 20 μm and 49.6 μm and has an average size of 32.2 μm. The manufacturing process parameters of the porous scaffold were set as laser power of 280 W, scanning speed of 1200 mm/s, a layer thickness of 30 μm and hatch distance of 140 μm. After completing fabrication, the as-built samples were cut down from the base plate via wire electrical discharge machining (Wire-EDM) and were then cleaned with pure ethyl alcohol using an ultrasonic cleaning machine and dried.

2.2. Material characterization

Prior to the compression tests, the dimensions and weights of as-fabricated specimens were measured by a digital Vernier caliper (smallest scale division of 0.01 mm) and an electronic balance (smallest scale increments of 0.1 μg), respectively. An AG-IC100 KN Electronic Universal Testing Machine (SHIMADZU, Japan) was used to conduct uniaxial quasi-static compression tests with a prescribed loading rate of 0.02 mm/s under ambient temperature. A digital camera was used to record the compression process and capture the failure characteristics of the structures. As suggested by the ISO standard 13,314:2011 (ISO Standard, 2011), Young's modulus and yield strength of the porous scaffold were derived by the slope between stress and strain during the linearly elastic stage and the intersection of the stress-strain curve and a line parallel to the linearly elastic curve at a strain offset of 0.2%, respectively.

2.3. Finite element model

To investigate the effect of gradient on stress distribution as well as dynamic deformation of graded pentamode metamaterials, finite element (FE) analysis was used to simulate the compressive process of these designed porous scaffolds with commercial software, COMSOL Multiphysics 5.4a. The material was assumed to have an elastic modulus of 120 GPa, a yield strength of 1197 MPa and a Poisson's ratio of 0.34 [30]. The post-yielding behavior, that is the non-linear physical property, was defined by a tabular input issued from the uniaxial tensile stress-strain curve of the SLM-built Ti6Al4V, which was presented in another related work [31].

A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model for fluid flow behavior analysis was also conducted [32]. The density and dynamic viscosity coefficient, , of the fluid medium were set to 1000 kg/m3 and 1.01 × 10−3 Pa s, respectively [32]. A low constant inlet velocity, , of 1 mm/s was imposed at the inlet surface while zero pressure was defined at the outlet surface. Importantly, the interface between the cellular structure and fluid phase was no slip. The average pressure drop and permeability were obtained by calculating Darcy's law given by:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Besides, to reduce dimensional effects, the computational permeability values were normalized by the permeability of a perfectly porous structure (vacant unit cell with the same spatial size) with the same above boundary conditions.

2.4. Cell isolation and culture

Human bone marrow specimens were harvested from donors. Isolation and identification of human bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were described in previous research [33]. BMSCs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and were used for further experiments from the second passage. BMSCs were cultured with an osteogenic induction medium (Cyagen Biosciences, USA) for osteogenic differentiation.

2.5. Cell proliferation activity

All the scaffolds were sterilized by a high temperature and autoclave for 30 min after cleaning. All scaffolds were extracted in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37 °C for up to 72 h. Extracts were prepared with a scaffold weight to extraction medium ratio of 0.2 g/mL according to GB/T 16886.5. The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was conducted to evaluate the proliferation activity of BMSCs after 24, 48 and 72 h culture in extracts. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the cells were rinsed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Beyotime) and incubated at 37 °C in a medium containing 10% CCK8. After 4 h of incubation, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer. 20% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was performed as a positive control [34].

2.6. Cell attachment and morphology assays

Cell attachment was observed on the surface of the scaffolds. Cells were cultured on the samples placed in 6-well culture plates at an initial density of 1 × 106 cells per well. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution and treated with 0.1% Trion-X-100. FITC-labeled Phalloidin solution (Beyotime) was used to stain the cytoskeleton at room temperature for 30 min. Then, DAPI solution was added to stain the cell nucleus for 10 min. Confocal images were taken by using the confocal laser scanning microscope. All experimental protocols involving human specimens and cells were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (NO.S347).

2.7. Western blotting analysis

Western blotting analyses were performed to evaluate the expression of Type I collagen (Col1a), runt-related transcription factor-2 (Runx-2), and osteocalcin (OCN). Briefly, the cells were cultured with scaffolds for 5 d [35] and were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beyotim) supplemented with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Beyotim) for 20 min. The concentration of the total proteins was measured using a BCA™ protein assay reagent (Beyotim). The proteins were loaded and electrophoresed using surePAGETM prefabricated gels (4–20%, Genscript, Nanjing, China) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The electrophoresis time and membrane transfer time were determined according to the molecular weight of the target proteins. After blocking with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-HCl buffer saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies, including Col1a, Runx-2, and OCN (Proteintech, IL, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the expression of proteins was measured using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein was used as a reference.

2.8. RT-qPCR

The expression of Col1a, Runx-2, and OCN of osteogenic differentiation was evaluated using RT-qPCR. Total RNA from cultured BMSCs was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and the RNA concentrations were detected. Reverse transcription and RT-qPCR were performed (Related primer sequences were shown in Table S4). RT-qPCR reaction consisted of a 95 °C denaturation step for 30 s, 40 cycles (95 °C for 5 s, 65 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C for 45 s), and an extension at 72 °C for 60 s. The reactions were repeated three times. The results were normalized to GAPDH and quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.9. In vivo osteogenesis of bone scaffolds

To further study the osteogenic effect of biomimetic porous scaffolds, rabbit models with femoral condyle defects were established. New Zealand white rabbits were provided by the Laboratory Animal Center of Hubei Yizhicheng biotechnology company (Yizhicheng, China). Twenty-four rabbits (weight: 2.5–3 kg) were used to establish a bone defect model in this experiment. All the scaffolds were sterilized at a high temperature and autoclaved for 30 min after cleaning. Sterilized cylindrical implants were placed into the predrilled defects in the distal femoral condyle. After 4 weeks and 12 weeks of implantation, the rabbits were anesthetized and euthanized, and the femurs containing the implants were harvested. Then, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT, Bruke Skyscan 1176) was used to evaluate new bone formation within different scaffolds. The sectional images with 9 μm resolution and three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed images were obtained, and the bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) values were analyzed for the quantitative evaluation of osteogenesis. For histological evaluation of new bone formation, the samples were dehydrated, embedded in methylmethacrylate, and sliced into 500 μm sections using hard tissue microtome (Exakt 300 T, Exakt Vertriebs Gmbh, Germany). The sections were stained with Van-Gieson staining (1.2% trinitrophenol and 1% acid fuchsin) following a previous study [35]. The sections were stained with H&E and Masson-Goldner trichrome staining as well. Images of new bone formation were obtained and analyzed using a digital pathology section scanning system (S360, Hamamatsu, Japan). All animal experiments were approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (NO.S2421). The animal experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and animal carcasses are treated harmlessly.

2.10. Statistical analysis

In the present work, three repeated compression tests were performed for each porous scaffold. The data obtained from mechanical tests and permeability measurements were analyzed and expressed as mean ± deviations. Relative cytotoxicity, real-time PCR analysis of the relative mRNA levels and analysis of new bone formation in vivo was analyzed by two-way ANOVA (a = 0.05) and post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparisons test (a = 0.05) with p < 0.0001, ****; p < 0.001, ***; p < 0.01, **; p < 0.05, *; n. s. = not significant.

3. Results and discussion

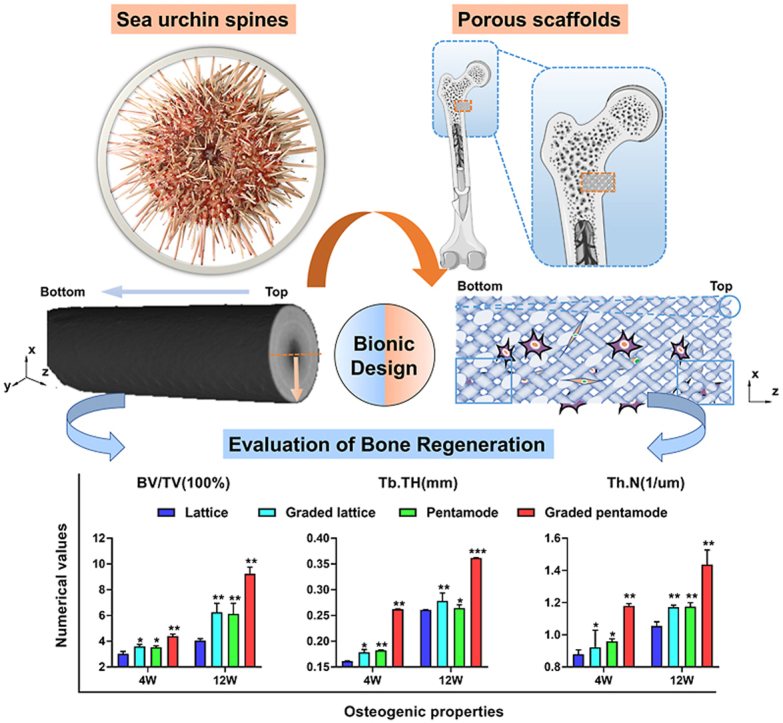

3.1. Feature of sea urchin spine and design of biomimetic scaffolds

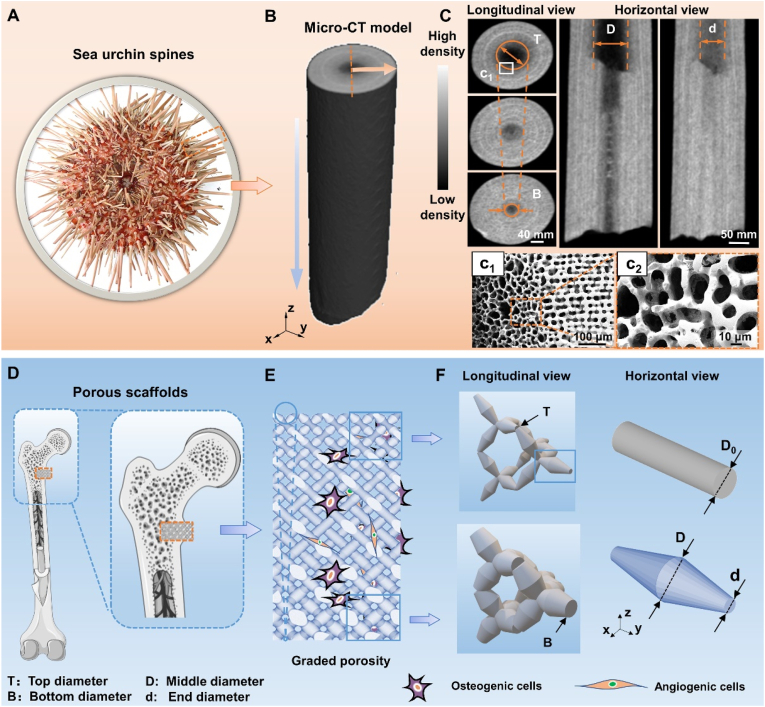

Sea urchins (Echinoidea) are an evolutionary highly successful and diverse class of animals populating earth's oceans for more than 450 million years [36]. Dependent on the environmental challenges, sea urchin spines have evolved an extremely lightweight construction with improved mechanical strength thanks to their hierarchical structure in both longitudinal and horizontal directions (Fig. 1A–C, Fig. S1). From the perspective of biological scaffold design, its multi-level pore topology is conducive to matter transmission and even cell adhesion, and multi-level structural configurations can regulate mechanical properties for suitable stress stimulation. Therefore, imitating the multi-level topology of sea urchin thorn for bone scaffold construction could achieve the tuning of geometrical pores, mechanical strength and mass-transport properties, which is beneficial to cell differentiation and bone regeneration.

Fig. 1.

Topological morphologies of sea urchin spine and its biomimetic scaffolds: Sea urchin spines' needle-like appearance and internal architecture of graded porosity. (A) The optical image shows the natural features of the sea urchin spine. (B) Micro-computed tomography (CT) images show internal graded porosity in horizontal view and longitudinal views. (C) SEM images present the delicate internal morphologies in (c1-c2) sectional views. (D) Schematic diagram of the position of porous scaffolds within the implant. (E) Biomimetic graded pentamode-based scaffolds. (F) Geometrical features of the graded density from longitudinal view and the tapering strut topology compared with the uniform struts in horizontal view.

To mimic the morphology of sea urchin spines (Fig. 1A), a single sea urchin spine was reconstructed by micro-computed tomography (CT) and carefully observed from a sectional view and front view obtained by a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Fig. 1B–C). From the horizontal view of the CT images, the low-density volume decreases from the top surface to the bottom surface, generating a tapering shape-like graded porosity (porosity width from D to d). Likewise, the high-density volume rises from the central section to the peripheral section in the longitudinal view. The low-density surface in the central section of the longitudinal view also seems to have a tapering shape-like topology, showing a graded porosity (porosity width from T to B). Furthermore, microstructure observations of the sea urchin spine present a porous characteristic and gradually varying porosity from the center to the outer edge (Fig. 1c1 and c2). For different positions in space, the porous morphologies or strut features of sea urchin spines differ (Fig. S1). The unconsolidated struts with a large interval distance are distributed in the central zone while the compact struts with a small interval distance are located in the peripheral area. The horizontal and longitudinal microstructures together constituted the hierarchical structural features, which support the excellent physical properties of sea urchin spines.

To construct porous scaffolds suitable for cortical and cancellous bone defects via mimicking the hierarchical morphology of sea urchin spines, a parameterized common pentamode lattice-based structure was rationally designed (Fig. 1E). First, we designed a tapering strut morphology (tapering from middle diameter D to end diameter d) to mimic the horizontal microstructures of sea urchin spines (Fig. 1F). Second, a graded density (grading from top diameter T to bottom diameter B) was designed to mimic the longitudinal microstructures of sea urchin spines (Fig. 1E). The bone scaffolds with different densities were obtained by changing the end and middle diameters of the tapering strut and the top and bottom diameters of the graded structure. Pentamode metamaterials (PMs) possess a tapering strut morphology and a graded density. This results in a larger specific surface area than uniform strut-based lattice structures with an equivalent relative density (Fig. S2), signifying more physical space for new bone tissue cells to stick to. Graded pentamode metamaterials are a kind of hierarchical graded porous structures with an intralayer gradient and an interlayer gradient, which indicate the tapering topology and the graded structure, respectively.

3.2. Morphological characterization of 3D printed biomimetic scaffolds

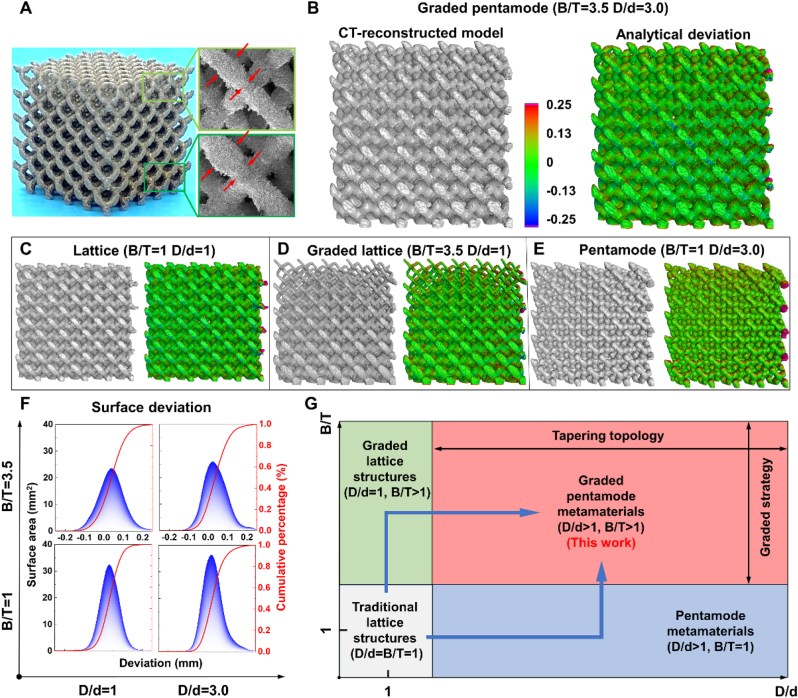

To investigate the effect of graded strategy and tapering topology on the manufacturing fidelity and on the mechanical, mass-transport, and biological properties of sea urchin spine-like graded pentamode-based scaffolds (PM-GD, B/T = 3.5, D/d = 3.0), we designed uniform diamond lattice structures with uniform struts (D-U, B/T = 1, D/d = 1), uniform pentamode metamaterials with tapering struts (PM-U, B/T = 1, D/d = 3.0), graded diamond lattice structures (D-GD, B/T = 3.5, D/d = 1) and graded pentamode metamaterials (PM-GD) to conduct a comparative study (Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S1).

Four kinds of bone scaffolds with different topological structures were successfully fabricated by selective laser melting (SLM)-based 3D printing technology. Optical photographs show the front view of 3D printed graded pentamode lattice and SEM images show the lateral view, presenting the geometrical feature with the corresponding designed one (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B–E displays the 3D CT-reconstructed results and the overall comparison nephograms between the micro-CT reconstructed and originally designed models for the graded pentamode lattice, diamond lattice, graded diamond lattice and pentamode lattice, respectively. The 3D deviation maps indicate that the deviation of the majority of the surfaces was nearly zero, shown in green color, and the largest deviations occur at the upper inner walls and the outside overhanging struts (Fig. S4). Statistical surface deviation distributions of scaffolds with different D/d and B/T are presented in Fig. 2F. All surface deviations for all exhibit an approximately Gaussian distribution that is not absolutely symmetrical with the peak surface deviation. The peak deviation of the graded pentamode lattice sample was 0.022 mm, which was approximately equivalent to the 0.023 mm peak deviation of the pentamode lattice, but well below the 0.032 mm and 0.043 mm peak deviation of the diamond and graded diamond lattices, respectively. The CT-statistical analysis also coincided with the macroscopic manufacturing deviation results (Table S2), indicating that the tapering topology could well improve the printing fidelity.

Fig. 2.

Ti–6Al–4V specimens' morphological characteristics of different topological structures fabricated by SLM: (A) Optical photographs show the front view of the 3D printed graded pentamode lattice and SEM images show the lateral view. The CT-reconstructed model is presented and 3D surface deviation maps are compared with the CAD model for (B) the graded pentamode lattice, (C) the diamond lattice, (D) graded diamond lattice and (E) pentamode lattice. (F) Statistical surface deviation distributions are plotted. (G) Design freedoms of topological structures with different D/d and B/T are compared.

Compared with the traditional lattice structures, the design freedom of the graded pentamode lattice has a wider structure design space (Fig. 2G). This scaffold meets the complex shape design requirements of different intralayer and interlayer gradients via the graded strategy and the tapering topology, respectively, so as to obtain various and decoupled mechanical properties and mass-transport performances.

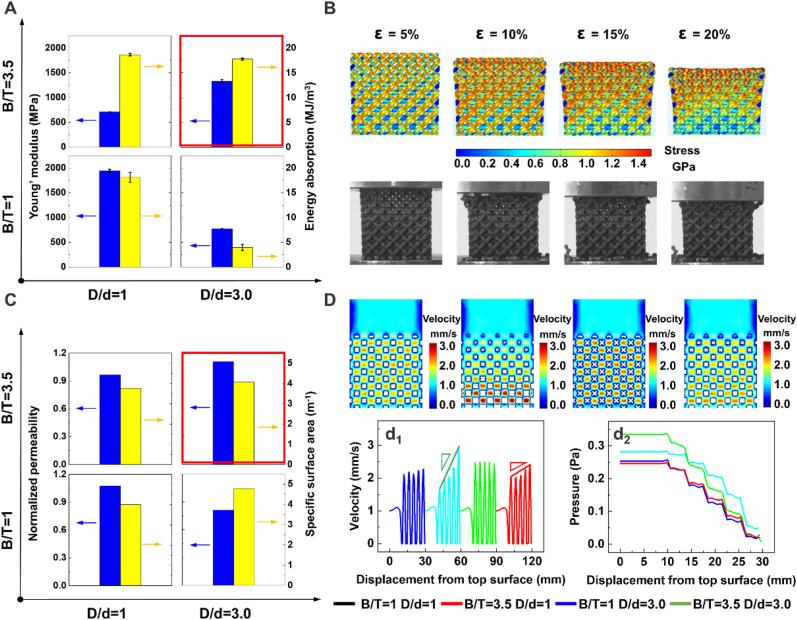

3.3. Mechanical and mass-transport performances of biomimetic scaffolds

In terms of mechanical properties, for uniform traditional lattices, using the graded strategy with increasing B/T did not significantly change the energy absorption per volume but decreased Young's modulus along the graded direction while using the tapering topology with increasing D/d caused the modulus and energy absorption to simultaneously drop off (Fig. 3A). With the increase of B/T, Young's modulus and energy absorption per volume of graded pentamode-based biomimetic scaffolds were larger than those of uniform pentamode-based scaffolds by 42.04% and 77.75%, respectively. Besides, when under the same graded strategy, the graded pentamode lattice had more excellent mechanical properties. On the other hand, continuous stepwise stress growth of graded diamond and pentamode lattice samples was observed under compression loading while the uniform lattices exhibited fracture morphology of 45° diagonal bands from the horizontal direction (Figs. S5 and S6). Continuous stress growth resulted from the layer-by-layer fracture pattern (Fig. 3B), which was attributed to the sequential variation of diameter parameters (Fig. S7). After each layer collapsed, the stress went up due to the increase in relative density, which was presented in the simulation results of compression processes. Therefore, the fracture process of any layer gradually starts at the top sub-layer of lower relative density to the bottom sub-layer of higher relative density.

Fig. 3.

Mechanical and mass-transport properties of the biomimetic scaffolds. (A) Young's modulus and energy absorption per volume of scaffolds with different topological structures. (B) Compression deformation processes of graded pentamode metamaterials. (C) Normalized permeability and specific surface area of different topological scaffolds with different topological structures. (D) Velocity distributions and velocity history as well as pressure variation versus displacement from the top surface of different topological scaffolds.

Mechanical properties of uniform lattices can be manipulated by the graded density and tapering strut to be properly calibrated to the host bone. As observed in Table S3, in terms of mechanical matching, regardless of pore distribution, graded diamond, pentamode, and graded pentamode lattices possess comparable stiffness values with the trabecular bone (E = 0.01–1.57 GPa [37]), while diamond lattices have higher mechanical properties, resulting in the stress shielding phenomenon. Under the same relative density, the root account of mechanical variation caused by the strut topology was the difference in the diameter arrangement on the struts. Specifically, the pentamode lattice could deform drastically due to the shorter end diameters (D0 - d) at the junctions, as compared with the uniform lattice cell (Fig. S8).

The energy absorption capability of cellular structures is a common tool to effectively understand the long-term endurance and the ability to withstand an abrupt impact fracture. The uniform pentamode lattice with a lower deformation resistance cannot play an important role in bearing loading and enduring impacts. The total absorbed energy at 60% strain decreased from 18.14 MJ/mm3 to 3.96 MJ/mm3 as the topology strut degenerated from a uniform strut (D/d = 1) to a tapering strut (D/d = 3.0). On the other hand, the energy-strain curves of graded lattices (B/T = 3.5) had an exponential growth from a lower level to a higher level of energy absorption, as compared with the corresponding uniform lattices (B/T = 1) (Fig. S9). It is readily observed that this law follows the progressive collapse of the deformation process from a low-level density layer to a high-level density layer.

For mass-transport performances, permeability had an exponential relationship with the porosity [38]. For uniform and graded structures with the same porosity, their permeability values are different. This is because the internal structure can change the distribution of fluid velocity, which then affects the permeability. It was found that the permeability of graded diamond lattices was slightly lower than that of uniform diamond lattices by 9.35%, while the permeability of graded pentamode lattices was significantly higher than that of uniform pentamode lattices by 27.27%. Graded pentamode-based biomimetic scaffolds possess the best permeability (Fig. 3C). From Fig. 3D, it is readily noted that almost no turbulence and only laminar flow occurs in the pore channel, where the water behaves smoothly through the scaffold from the inlet to outlet. The velocity is mostly concentrated in the pore center due to no obstacles cutting off the fluid flow, while the fluid-scaffold interface has a lower flow rate. It is distinctly seen that the velocity distribution of graded pentamode-based biomimetic scaffolds is more pronounced than that of graded diamond lattices due to the increased inner sinuosity that is caused by the tapering design.

The pentamode unit cell possessed the highest specific surface area among these structures, whereas the permeability value of uniform pentamode scaffolds was the lowest, which is attributed to the fact that the tapering topology simultaneously expanded the internal space and increase the surface for cell seeding. This result was opposite to that summarized by Syahrom et al. [39] but consistent with the experiments of Bobbert et al. [40]. The latter considered that increasing surface area would decrease permeability due to the additional frictional effects. However, the porosity of traditional lattice structures would decrease as the specific area increased, leading to inefficient transmission capacity. Besides, the cell seeding efficiency of uniform pentamode lattices was always higher than that of uniform diamond lattices under identical relative density due to the higher specific area. This illustrates that the pentamode lattice could well balance both the transport property and cell seeding efficiency. For graded lattices, as expected, velocity values of the center region increased with increasing relative density along the flow direction, which is attributed to the gradient pore size (Fig. 3D and S10). A higher velocity implies that the flow has less resistance when permeating the scaffold, leading to higher average permeability and less chance for bone cells to attach to the surface. Therefore, the low-velocity region of the graded lattice scaffolds would have higher seeding efficiency. On the other hand, from the view of Bobbert et al. [40], higher velocity values are required to transport the nutrients, oxygen, etc. Into a deeper part of the scaffold; otherwise, the cell metabolism would probably be disrupted at least in some regions. Thus, there should be an optimum balance of transport capability and cell seeding efficiency.

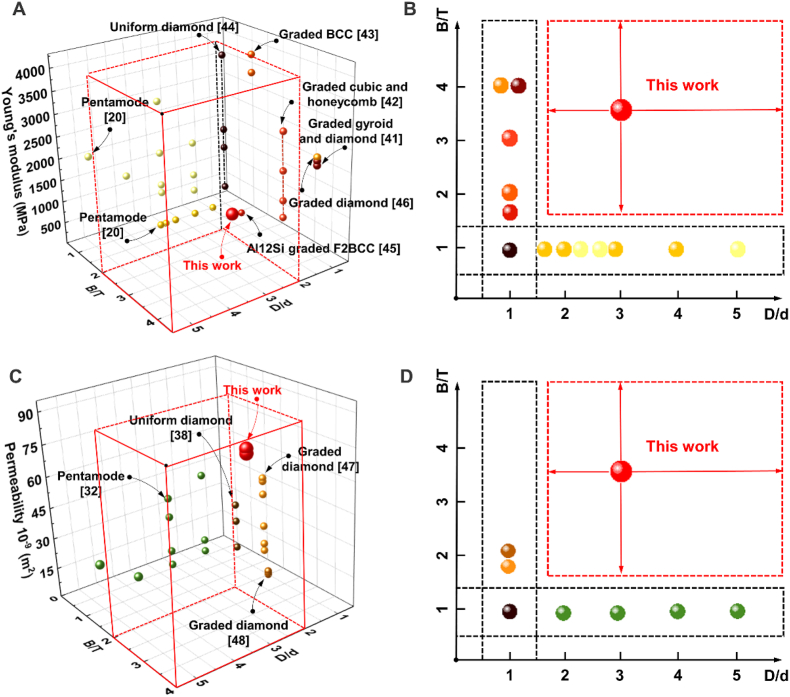

Fig. 4 presents a comparison of mechanical and mass-transport properties of various structures with different B/T and D/d. The Young's modulus of the graded pentamode metamaterials is lower than those of diamond lattice [41], honeycomb lattice [42] and BCC lattice [43] but appropriate for cancellous bone. However, uniform pentamode metamaterials with different D/d possess the lowest stiffness [20], which is caused by the tiny end diameter. The graded pentamode lattice possesses higher fluid permeability compared to the lattice-based scaffolds with D/d = 1 or T/B = 1. The Young's modulus and fluid permeability of graded pentamode lattices could be further tuned by structural gradient T/B and diameter ratio D/d so that graded pentamode lattices could achieve an unprecedented level of tailoring of their multi-physics properties.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of (A-B) mechanical and (C-D) mass-transport properties of various structures with different B/T and D/d [20,32,38,[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]].

3.4. In vitro bioactivity analysis of biomimetic scaffolds

Fig. 5 presents an illustration of the SLM fabrication, in vitro cell activity assay and in vivo osteogenic assay procedures. The interesting result of this study is that the SLM-prepared biomimetic graded pentamode-based scaffolds possess excellent bioactivity both in vitro and in vivo. Firstly, to explore the effect of pentamode-based structure of scaffolds on the cell delivery and osteogenic differentiation of human bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), the cells were cultured on the biomimetic scaffolds with different graded porosities and tapering levels. Then, to further investigate in vivo bone-forming bioactivity, uniform diamond, graded diamond, uniform pentamode and graded pentamode scaffolds were respectively implanted into rabbit femoral defect for 4 and 12 weeks.

Fig. 5.

An illustration of the SLM fabrication, in vitro cell activity assay and in vivo osteogenic assay procedures.

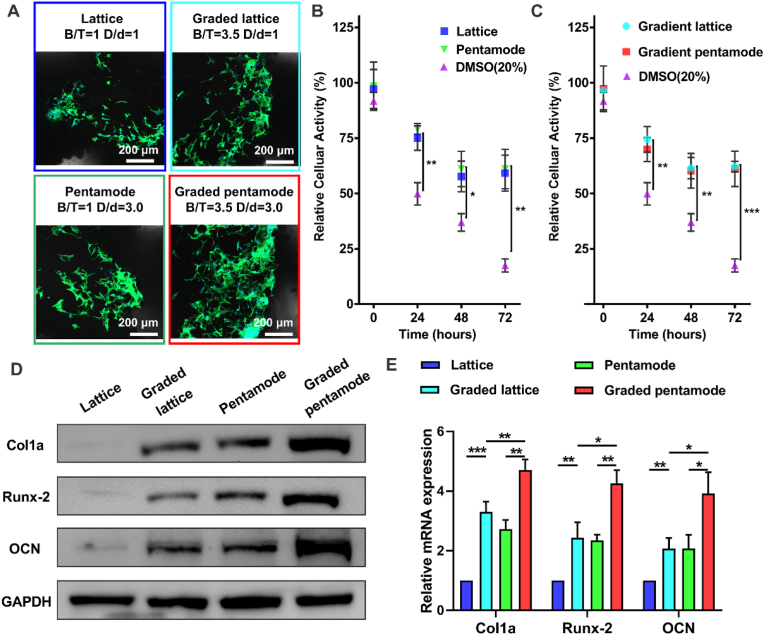

Fluorescence staining results of living cells with different uniform/graded scaffolds were shown in Fig. 6A. Direct cytocompatibility evaluation shows that fluorescently labeled adherent cells were around and in the center of the scaffold. When comparing different topologies of porous scaffolds, no specific cell distribution pattern can be determined. The relative cellular activities of BMSCs extracts from different porous bone scaffolds (D-U, D-GD, PM-U, and PM-GD) prepared by SLM and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were compared (Fig. 6B and C). The cell survival rate of all porous scaffolds in 24 h extract was close to 75%, while that of DMSO in 24 h extract was only 50%. The cell survival rate of porous scaffolds in 72 h extract decreased to 60%, while that of DMSO in 72 h extract decreased to less than 25%. Besides, the cell viability of DMSO extract decreases gradually as the extraction time changes, while the cell viability of porous scaffolds extract was maintained at about 60% after 48 h. Under these conditions, the cytotoxicity of graded porous scaffolds was not significantly higher than that of uniform porous scaffolds. This was consistent with recent studies that analyzed human mesenchymal stromal cells in a 3D scaffold with a gradient pore size [49] and the use of preosteoblasts in a gradient Ti–6Al–4V porous scaffold [43]. The latter concluded that the degree of attachment of cells to struts of different diameters was similar. However, it was found that there was a greater cell distribution on graded scaffolds; that is, a relatively large number of cells adhered to the thicker struts than to the thinner struts, due to the wide space for cell growth provided by the graded structure and the larger surface area provided by the larger-diameter struts. Logically, this might lead to more interaction with the material's surface as the cells pass through the pores. Higher porosity and larger pore sizes may be advantageous in vivo, because they could possess adequate metabolism and matter transport, then stimulate bone regeneration. However, too large pore size means that the specific surface area of the scaffold is reduced, which is not conducive to the attachment of bone cells. Therefore, the pore size needs to be within an optimized range. The biomimetic scaffold (graded pentamode lattice in this work) has a pore size ranging between 0.69 and 2.08 mm, which is reasonable with the human bone of pore size more in the range between 0.7 and 1.2 mm [[50], [51], [52]]. The biomimetic graded scaffolds with a larger pore size range are believed to improve the overall quality of scaffolds, which combine small pores (<1000 mm) for initial cell attachment and large pores (>1000 mm) to obtain nutrient and oxygen supply.

Fig. 6.

In vitro bioactivity analysis of different topological structures. (A) 2D confocal laser scanning microscopy images of BMSCs seeded on the bone structure scaffolds. Relative cytocompatibility evaluation of (B) uniform and (C) graded cellular structures. Expression of osteogenic genes: (D) western blot results of Col1a, Runx-2, OCN, and GAPDH expressions in BMSCs on day 5 and (E) Real-time PCR analysis of the relative mRNA levels of Col1a, Runx-2, and OCN. (Scale bar: 200 μm).

To study the immunomodulatory effect of uniform/graded design of porous scaffolds on osteogenic differentiation, Western blot analysis was used to study the osteogenic gene expression level of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells under different porous scaffolds (Fig. 6D–E). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein was used as a reference. The expression levels of Col1a, Runx-2, and OCN in continuous graded lattices (D-GDs and PM-GDs) were significantly higher than those in uniform lattices (D-Us and PM-Us). Besides, the expression levels of osteogenic genes (Col1a, Runx-2, and OCN) in the graded pentamode-based biomimetic scaffold (PM-GD) group were higher than those in the D-GD group. These results indicated that the continuously graded porosity and the tapering strut were conducive to the expression of osteogenic genes, cell proliferation, and differentiation. Previous studies demonstrated that porosity is optimal for cell growth and differentiation in bone scaffolds [53,54]. Moreover, different pore sizes present different capacities for cell growth and bone formation [55,56]. Thus, the potential reason for the expression levels increases of osteogenic genes in continuous graded lattices (D-GDs and PM-GDs) may be that continuous graded lattices provided optimal porosity and pore sizes for osteogenic differentiation and bone formation.

3.5. In vivo bioactivity analysis of biomimetic scaffolds

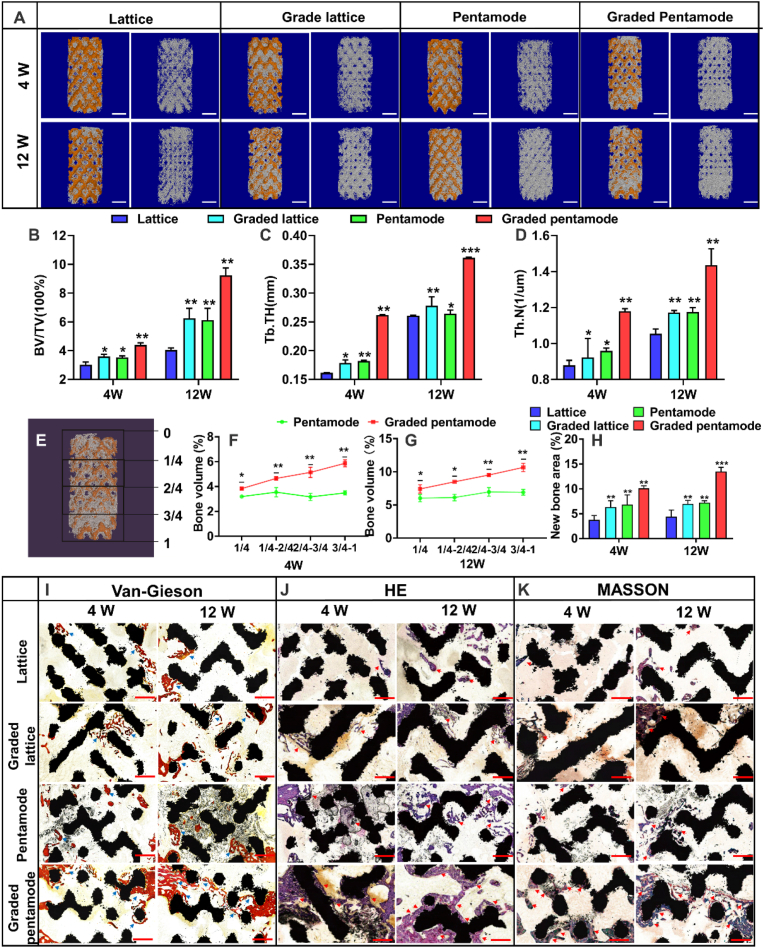

Fig. 7A showed three-dimensional reconstruction micro-CT images of rabbit femoral condyle defects repaired with D-U, D-GD, PM-U, and PM-GD scaffolds (weeks 4 and 12). Location map of porous stent implantation and CAD topological structure map of different porous scaffolds was presented in Fig. S11. In the 4th week after the operation, new bone formation was found around and in the scaffolds of different structural scaffolds, and the new bone volume of graded scaffolds was significantly larger than that of uniform scaffolds. It should be noted that at any given point in time, whether 4 or 12 weeks after surgery, the graded scaffold groups had more new bone mass than the uniform scaffold groups. The above results confirm that the graded scaffold has good osteogenic performance in vivo, and the specific new bone mass parameters are shown in Fig. 7B. The bone mineral density (Bone volume/Total volume, BV/TV) of the graded scaffold groups was higher than those of uniform scaffold groups. Especially at the 12th week, the bone mineral density of graded diamond and graded pentamode-based metamaterial scaffolds (6.25% and 9.23% respectively) were 54.42% and 50.87% higher than those of uniform structure (4.05% and 6.12% respectively). Secondly, at any point in time, the new bone mineral density of the biomimetic pentamode-based scaffold was higher than that of the diamond lattice scaffold. From the 4th week to the 12th week, the bone mineral density of new bone of the PM-U and PM-GD porous scaffolds increased from being 16.83% and 22.21% higher than that of D-U and D-GD porous scaffolds to being 51.25% and 47.78% higher, respectively. The results show that the Trabecular Thickness (Tb. Th) and Trabecular Number (Tb.N) increase as the body heals while new bone tissue begins to form and grow thicker (Fig. 7C–D). The results of bone volume (%) in the different areas showed that percentages of regenerated bone volume in the porous scaffolds increased as the distance from the scaffold top to the scaffold bottom (Fig. 7E–G). The graded pentamode lattice scaffold has the best osteogenic performance in vivo, and the specific new bone volume parameters are shown in Fig. 7H. Van-Gieson, H&E and Masson-Goldner trichrome staining indicated that the newly regenerated bone of the graded biomimetic pentamode-based scaffold is more than those of the other three scaffold groups (Fig. 7I–K).

Fig. 7.

The evaluation of new bone formation: (A) micro-CT images of these porous scaffolds implanted in the rabbit femur at 4 weeks and 12 weeks (scale bar: 2 mm); bone-related parameters (B) BV/TV; (C) Tb. Th and (D) Tb.N. (E) General sketch of bone ingrowth into the porous scaffold to describe the distance from the scaffold top to the scaffold bottom. (F) and (G) Percentages of regenerated bone volume into the porous scaffolds. (H) Calculation of the newly formed bone area from Van-Gieson stained histological sections. (I), (J) and (K) are Van-Gieson, H&E and Masson-Goldner trichrome stained histological sections of scaffolds after being implanted for 4 and 12 weeks. Newly formed bones (in red and purple) indicated by the arrows as well as the structural scaffolds (in black) can be well observed. (scale bar: 1 mm).

The sea urchin spine-like biomimetic scaffolds (PM-GD) had the best effect on the thickness and number of trabeculae and new bone density. Implanted scaffolds for segmental bone defects are mostly surrounded by bone tissues with various structures and biomechanical performance. The graded design strategy was used for the biological porous scaffolds, which was in accordance with the original geometry topology and stress environment of bone tissue. Furthermore, graded scaffolds usually possess the layer-by-layer collapse failure that is beneficial to the energy absorption in order to withstand an abrupt impact fracture. On the other hand, with respect to the biological properties of graded scaffolds, the high-density distribution of cells [57] and accelerated bone defect healing [58] were also observed in previous literature. These results further proved the importance and necessity of exploring an optimum design strategy for functionally graded scaffolds.

Combined with pentamode metamaterials, biomimetic scaffolds would further increase the specific surface area of the porous scaffolds, giving more physical space for cell proliferation and differentiation. The simulation results from the mass-transport process can be found in Fig. 3D. The pentamode metamaterial with graded porosity had a more uniform transport behavior, which facilitated the input and output processes of nutrients and metabolites of the whole scaffold. In this study, integrated with the above evaluation studies on mechanical properties, mass transport properties, and osteogenic properties in vivo, the porous structure of PM-GD shows a super strong ability to repair bone injuries. Firstly, the distribution of graded pores is consistent with the mechanical environment of bone defects, which is convenient for the growth of new bone tissue. Secondly, the specific surface area of pentamode metamaterials is large, which is conducive to cell proliferation and differentiation.

4. Conclusion

In this work, a design method for optimizing cell transport characteristics and improving cell seeding efficiency of pentamode metamaterials with sea urchin spines-like biomimetic tapering strut and graded porosity is proposed. The tapering strut and graded pore design could enhance the mechanical and mass-transport performance of the biological scaffold, which then improves the osteogenic performance. The tapering topology can better balance the cell transport characteristics and cell sowing efficiency due to the expansion of internal space and increase of surface area. The distribution of graded pores, similar to the pores in bone tissue, is beneficial to the proliferation and differentiation of cells. Due to the tapering topology and the graded strategy, the permeability of graded pentamode metamaterials was increased by 27.27% compared with that of the uniform diamond lattice structure. In vivo experiments verified the excellent osteogenesis performance of graded pentamode metamaterials, and the bone density of graded pentamode metamaterials was 50.87% higher than that of uniform pentamode metamaterials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols involving human specimens and cells were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (NO.S347). Informed consent was obtained from the participant included in the study. All animal experiments were approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (NO.S2421). The animal experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and animal carcasses are treated harmlessly.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lei Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Bingjin Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Bo Song: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Yonggang Yao: Writing – review & editing. Seung-Kyum Choi: Writing – review & editing. Cao Yang: Writing – review & editing. Yusheng Shi: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled, “3D Printed Biomimetic Metamaterials with Graded Porosity and Tapering Topology for Improved Cell Seeding and Bone Regeneration”.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51922044), the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B090923001), the Academic frontier youth team at Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) (2018QYTD04). The authors thank the Analytical and Testing Center of HUST for SEM examination and the State Key Laboratory of Materials Processing and Die & Mould Technology for compression tests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.07.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Yang Y., Cheng Y., Peng S., Xu L., He C., Qi F., Zhao M., Shuai C. Microstructure evolution and texture tailoring of reduced graphene oxide reinforced Zn scaffold. Bioact. Mater. 2021;6(5):1230–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Fu P., Wang N., Peng L., Kang B., Zeng H., Yuan G., Ding W. Challenges and solutions for the additive manufacturing of biodegradable magnesium implants. Engineering. 2020;6(11):1267–1275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheinpflug J., Pfeiffenberger M., Damerau A., Schwarz F., Textor M., Lang A., Schulze F. Journey into bone models: a review. Genes. 2018;9(247):1–36. doi: 10.3390/genes9050247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Entezari A., Roohani I., Li G., Dunstan C.R., Rognon P., Li Q., Jiang X., Zreiqat H. Architectural design of 3D printed scaffolds controls the volume and functionality of newly formed bone. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(1) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shuai C., Yang W., Feng P., Peng S., Pan H. Accelerated degradation of HAP/PLLA bone scaffold by PGA blending facilitates bioactivity and osteoconductivity. Bioact. Mater. 2021;6(2):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An J., Teoh J.E.M., Suntornnond R., Chua C.K. Design and 3D printing of scaffolds and tissues. Engineering. 2015;1(2):261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Q., Dong H., Su J., Han J., Song B., Wei Q., Shi Y. A review of 3D printing technology for medical applications. Engineering. 2018;4(5):729–742. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tertuliano O.A., Greer J.R. The nanocomposite nature of bone drives its strength and damage resistance. Nat. Mater. 2016;15(11):1195–1202. doi: 10.1038/nmat4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do A.V., Khorsand B., Geary S.M., Salem A.K. 3D printing of scaffolds for tissue regeneration applications. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4(12):1742–1762. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M., Lin R., Wang X., Xue J., Deng C., Feng C., Zhuang H., Ma J., Qin C., Wan L., Chang J., Wu C. 3D printing of Haversian bone–mimicking scaffolds for multicellular delivery in bone regeneration. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(12) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langdahl B., Ferrari S., Dempster D.W. Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2016;8(6):225–235. doi: 10.1177/1759720X16670154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park Y., Cheong E., Kwak J.-G., Carpenter R., Shim J.-H., Lee J. Trabecular bone organoid model for studying the regulation of localized bone remodeling. Sci. Adv. 2021;7(4):abd6495. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd6495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M.O., Vorwald C.E., Dreher M.L., Mott E.J., Cheng M.H., Cinar A., Mehdizadeh H., Somo S., Dean D., Brey E.M., Fisher J.P. Evaluating 3D-printed biomaterials as scaffolds for vascularized bone tissue engineering. Adv Mater. 2015;27(1):138–144. doi: 10.1002/adma.201403943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrochenko P.E., Torgersen J., Gruber P., Hicks L.A., Zheng J., Kumar G., Narayan R.J., Goering P.L., Liska R., Stampfl J., Ovsianikov A. Laser 3D printing with sub-microscale resolution of porous elastomeric scaffolds for supporting human bone stem cells. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4(5):739–747. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maconachie T., Leary M., Lozanovski B., Zhang X., Qian M., Faruque O., Brandt M. SLM lattice structures: properties, performance, applications and challenges. Mater. Des. 2019;183 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L., Song B., Liu R., Zhao A., Zhang J., Zhuo L., Tang G., Shi Y. Effects of structural parameters on the Poisson's ratio and compressive modulus of 2D pentamode structures fabricated by selective laser melting. Engineering. 2020;6(1):56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L., Yan C., Cao W., Liu Z., Song B., Wen S., Zhang C., Shi Y., Yang S. Compression–compression fatigue behaviour of gyroid-type triply periodic minimal surface porous structures fabricated by selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 2019;181:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davoodi E., Montazerian H., Esmaeilizadeh R., Darabi A.C., Rashidi A., Kadkhodapour J., Jahed H., Hoorfar M., Milani A.S., Weiss P.S., Khademhosseini A., Toyserkani E. Additively manufactured gradient porous Ti-6Al-4V hip replacement implants embedded with cell-laden gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13(19):22110–22123. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez S., Vlad M.D., López J., Fernández E. Design and properties of 3D scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2016;42:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedayati R., Leeflang A.M., Zadpoor A.A. Additively manufactured metallic pentamode meta-materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017;110(9) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie R.O. The conflicts between strength and toughness. Nat. Mater. 2011;10(11):817–822. doi: 10.1038/nmat3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wegst U.G., Bai H., Saiz E., Tomsia A.P., Ritchie R.O. Bioinspired structural materials. Nat. Mater. 2015;14(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nmat4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwangbo H., Kim W., Kim G.H. Lotus-root-like microchanneled collagen scaffold. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13(11):12656–12667. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c14670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H., Wang H., Pan J., Li J., Zhang K., Duan W., Liang H., Chen K., Geng D., Shi Q., Yang H., Li B., Chen H. Nanoscaled bionic periosteum orchestrating the osteogenic microenvironment for sequential bone regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(33):36823–36836. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c06906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Zhang M., Ma J., Xu M., Chang J., Gelinsky M., Wu C. 3D printing of cell-container-like scaffolds for multicell tissue engineering. Engineering. 2020;6(11):1276–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan G., Zhang J., Zheng L., Jiao D., Liu Z., Zhang Z., Ritchie R.O. Nature-inspired nacre-like composites combining human tooth-matching elasticity and hardness with exceptional damage tolerance. Adv Mater. 2019;31(52) doi: 10.1002/adma.201904603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B., Sullivan T.N., Pissarenko A., Zaheri A., Espinosa H.D., Meyers M.A. Lessons from the ocean: whale baleen fracture resistance. Adv Mater. 2019;31(3) doi: 10.1002/adma.201804574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciasca G., Papi M., Businaro L., Campi G., Ortolani M., Palmieri V., Cedola A., De Ninno A., Gerardino A., Maulucci G., De Spirito M. Recent advances in superhydrophobic surfaces and their relevance to biology and medicine. Bioinspiration Biomimetics. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1088/1748-3190/11/1/011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng C., Zhang W., Deng C., Li G., Chang J., Zhang Z., Jiang X., Wu C. 3D printing of Lotus root-like biomimetic materials for cell delivery and tissue regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2017;4(12) doi: 10.1002/advs.201700401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L., Song B., Zhao A., Liu R., Yang L., Shi Y. Study on mechanical properties of honeycomb pentamode structures fabricated by laser additive manufacturing: numerical simulation and experimental verification. Compos. Struct. 2019;226 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L., Song B., Choi S.-K., Shi Y. A topology strategy to reduce stress shielding of additively manufactured porous metallic biomaterials. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021;197 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L., Song B., Yang L., Shi Y. Tailored mechanical response and mass transport characteristic of selective laser melted porous metallic biomaterials for bone scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2020;112:298–315. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao Z., Luo R., Li G., Song Y., Zhan S., Zhao K., Hua W., Zhang Y., Wu X., Yang C. Exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells modulate endoplasmic reticulum stress to protect against nucleus pulposus cell death and ameliorate intervertebral disc degeneration in vivo. Theranostics. 2019;9(14):4084–4100. doi: 10.7150/thno.33638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Jahr H., Lietaert K., Pavanram P., Yilmaz A., Fockaert L.I., Leeflang M.A., Pouran B., Gonzalez-Garcia Y., Weinans H., Mol J.M.C., Zhou J., Zadpoor A.A. Additively manufactured biodegradable porous iron. Acta Biomater. 2018;77:380–393. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang H., Zhao D., Feng X., Ma L., Deng X., Han C., Wei Q., Yang C. 3D-printed porous titanium scaffolds incorporating niobium for high bone regeneration capacity. Mater. Des. 2020;194 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Presser V., Schultheis S., Kohler C., Berthold C., Nickel K.G., Vohrer A., Finckh H., Stegmaier T. Lessons from nature for the construction of ceramic cellular materials for superior energy absorption. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2011;13(11):1042–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu X., Zheng Y. A review on magnesium alloys as biodegradable materials. Front. Mater. Sci. China. 2010;4(2):111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montazerian H., Zhianmanesh M., Davoodi E., Milani A.S., Hoorfar M. Longitudinal and radial permeability analysis of additively manufactured porous scaffolds: effect of pore shape and porosity. Mater. Des. 2017;122:146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syahrom A., Kadir M.R.A., Abdullah J., Öchsner A. Permeability studies of artificial and natural cancellous bone structures. Med. Eng. Phys. 2013;35:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bobbert F.S.L., Lietaert K., Eftekhari A.A., Pouran B., Ahmadi S.M., Weinans H., Zadpoor A.A. Additively manufactured metallic porous biomaterials based on minimal surfaces: a unique combination of topological, mechanical, and mass transport properties. Acta Biomater. 2017;53:572–584. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu F., Mao Z., Zhang P., Zhang D.Z., Jiang J., Ma Z. Functionally graded porous scaffolds in multiple patterns: new design method, physical and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2018;160:849–860. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choy S.Y., Sun C.-N., Leong K.F., Wei J. Compressive properties of functionally graded lattice structures manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2017;131:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onal E., Frith J., Jurg M., Wu X., Molotnikov A. Mechanical properties and in vitro behavior of additively manufactured and functionally graded Ti6Al4V porous scaffolds. Metals. 2018;8(4) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amin Yavari S., Ahmadi S.M., Wauthle R., Pouran B., Schrooten J., Weinans H., Zadpoor A.A. Relationship between unit cell type and porosity and the fatigue behavior of selective laser melted meta-biomaterials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015;43:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Saedi D.S.J., Masood S.H., Faizan-Ur-Rab M., Alomarah A., Ponnusamy P. Mechanical properties and energy absorption capability of functionally graded F2BCC lattice fabricated by SLM. Mater. Des. 2018;144:32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Grunsven W., Hernandez-Nava E., Reilly G., Goodall R. Fabrication and mechanical characterisation of titanium lattices with graded porosity. Metals. 2014;4(3):401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y., Jahr H., Pavanram P., Bobbert F.S.L., Puggi U., Zhang X.Y., Pouran B., Leeflang M.A., Weinans H., Zhou J., Zadpoor A.A. Additively manufactured functionally graded biodegradable porous iron. Acta Biomater. 2019;96:646–661. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X.-Y., Fang G., Xing L.-L., Liu W., Zhou J. Effect of porosity variation strategy on the performance of functionally graded Ti-6Al-4V scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Des. 2018;157:523–538. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Luca A., Ostrowska B., Lorenzo-Moldero I., Lepedda A., Swieszkowski W., Van Blitterswijk C., Moroni L. Gradients in pore size enhance the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells in three-dimensional scaffolds. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep22898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber F.E. Reconsidering osteoconduction in the era of additive manufacturing. Tissue Eng. B Rev. 2019;25(5):375–386. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2019.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karageorgiou V., Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26(27):5474–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Wild M., Ghayor C., Zimmermann S., Rüegg J., Nicholls F., Schuler F., Chen T.-H., Weber F.E. Osteoconductive lattice microarchitecture for optimized bone regeneration. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2019;6(1):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramu M., Ananthasubramanian M., Kumaresan T., Gandhinathan R., Jothi S. Optimization of the configuration of porous bone scaffolds made of Polyamide/Hydroxyapatite composites using Selective Laser Sintering for tissue engineering applications. Bio Med. Mater. Eng. 2018;29:739–755. doi: 10.3233/BME-181020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng X., Ma L., Liang H., Liu X., Lei J., Li W., Wang K., Song Y., Wang B., Li G., Li S., Yang C. Osteointegration of 3D-printed fully porous polyetheretherketone scaffolds with different pore sizes. ACS Omega. 2020;5(41):26655–26666. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c03489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang B., Song W., Han T., Yan J., Li F., Zhao L., Kou H., Zhang Y. Influence of pore size of porous titanium fabricated by vacuum diffusion bonding of titanium meshes on cell penetration and bone ingrowth. Acta Biomater. 2016;33:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan K.H., Chua C.K., Leong K.F., Naing M.W., Cheah C.M. Fabrication and characterization of three-dimensional poly(ether-ether-ketone)/-hydroxyapatite biocomposite scaffolds using laser sintering. Proc. IME H J. Eng. Med. 2005;219(3):183–194. doi: 10.1243/095441105X9345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erisken C., Kalyon D.M., Wang H. Functionally graded electrospun polycaprolactone and beta-tricalcium phosphate nanocomposites for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2008;29(30):4065–4073. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nune K.C., Kumar A., Misra R.D.K., Li S.J., Hao Y.L., Yang R. Functional response of osteoblasts in functionally gradient titanium alloy mesh arrays processed by 3D additive manufacturing. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;150:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.