Abstract

Objective

To provide information and recommendations to women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer and their physicians regarding hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Outcomes

Control of menopausal symptoms, quality of life, prevention of osteoporosis, prevention of cardiovascular disease, risk of recurrence of breast cancer, risk of death from breast cancer.

Evidence

Systematic review of English-language literature published from January 1990 to July 2001 retrieved from MEDLINE and CANCERLIT.

Recommendations

· Routine use of HRT (either estrogen alone or estrogen plus progesterone) is not recommended for women who have had breast cancer. Randomized controlled trials are required to guide recommendations for this group of women. Women who have had breast cancer are at risk of recurrence and contralateral breast cancer. The potential effect of HRT on these outcomes in women with breast cancer has not been determined in methodologically sound studies. However, in animal and in vitro studies, the development and growth of breast cancer is known to be estrogen dependent. Given the demonstrated increased risk of breast cancer associated with HRT in women without a diagnosis of breast cancer, it is possible that the risk of recurrence and contralateral breast cancer associated with HRT in women with breast cancer could be of a similar magnitude. · Postmenopausal women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer who request HRT should be encouraged to consider alternatives to HRT. If menopausal symptoms are particularly troublesome and do not respond to alternative approaches, a well-informed woman may choose to use HRT to control these symptoms after discussing the risks with her physician. In these circumstances, both the dose and the duration of treatment should be minimized.

Validation

Internal validation within the Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer; no external validation.

Sponsor

The steering committee was convened by Health Canada.

Completion date

October 2001.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) connotes treatment with either estrogen alone or estrogen with progesterone in postmenopausal women. Menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness, and the potential long-term effects of estrogen deprivation are a concern to women with breast cancer, particularly those in whom menopause develops early as a result of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Traditionally, the use of HRT has been contraindicated in women with breast cancer because of the notion that the development and growth of breast cancer is estrogen dependent and that the introduction of HRT may increase the risk of breast cancer recurrence. The focus of this guideline is on whether it is safe to give HRT to women with breast cancer.

Methods

This guideline is based on a systematic review of the English-language literature published from January 1990 to July 2001 retrieved from MEDLINE and CANCERLIT. Medical subject headings used in the search were “breast,” “breast neoplasms,” “estrogen replacement therapy,” “estrogens” and “hormone replacement therapy.” For the purposes of this guideline we considered HRT as replacement with either estrogen alone or estrogen plus progesterone. Review articles and textbook chapters were also consulted, primarily to provide background information and to secure additional references. Rules of evidence as described by Sackett1 were used for grading the levels of experimental studies. The initial draft was prepared by a writing committee and was revised according to feedback from several members of the Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer. The document was then discussed by the entire steering committee at meetings in May and October 2001, and further revisions were made. The final document was approved by the steering committee.

Evidence from randomized trials (levels I and II) on the efficacy and safety of HRT in women with breast cancer is unavailable. Hence we first reviewed indirect evidence relating estrogen exposure to breast cancer and then considered the limited number of studies involving women with breast cancer who took HRT. For the suggested alternatives to HRT that can be considered by women with breast cancer, we reviewed the highest level of evidence available but did not conduct a comprehensive systematic review of the literature.

Recommendations (including evidence and rationale)

Safety of HRT in women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer

· Routine use of HRT (either estrogen alone or estrogen plus progesterone) is not recommended for women who have had breast cancer. Randomized controlled trials are required to guide recommendations for this group of women. Women who have had breast cancer are at risk of recurrence and contralateral breast cancer. The potential effect of HRT on these outcomes in women with breast cancer has not been determined in methodologically sound studies. However, in animal and in vitro studies, the development and growth of breast cancer are known to be estrogen dependent. Given the demonstrated increased risk of breast cancer associated with HRT in women without a diagnosis of breast cancer, it is possible that the risk of recurrence and contralateral breast cancer associated with HRT in women with breast cancer could be of a similar magnitude.

Indirect evidence

Estrogen and progesterone in experimental studies

The basic biology of breast cancer indicates that estrogen contributes to its development. Many animal and in vitro studies have shown the development of breast cancer to be estrogen dependent.2,3 Virtually all mouse mammary tumour models and mouse xenograft models as well as many in vitro cell lines are dependent on estrogen for their growth and spread. Data from animal and in vitro experiments concerning progesterone are less conclusive. In some studies progesterone had an inhibiting effect on breast cancer growth, whereas in other studies the reverse was true.2,3,4

Epidemiologic studies

Epidemiological data from case–control and cohort studies have shown that a number of factors related to estrogen or to estrogen and progesterone cycling are associated with increased risk of breast cancer.5 These include the observations that early menarche and late menopause are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and that premature menopause, whether natural or surgically induced, substantially reduces the risk of breast cancer.6

HRT in healthy women

More than 50 case–control and cohort studies of the association between HRT and breast cancer development have been carried out. Initially, the results seemed conflicting, but with longer use of HRT and with meta-analyses to examine these results, it has become clear that there is probably a relative risk of breast cancer of 1.3 or 1.4 associated with HRT use, particularly if the use is long term. The most recent analysis of data from 51 studies involving a total of 52 000 women with breast cancer and 108 000 women without breast cancer reported a 1.31 relative risk among long-term HRT users.7 In addition, recent studies suggest that the addition of progesterone to estrogen increases the risk of breast cancer.7,8,9,10

Effect of estrogen removal in women with breast cancer

Ovarian ablation, presumably because it eliminates most estrogen production, results in a significant reduction in breast cancer recurrence and death (level I evidence).11 Furthermore, it is felt that the enhanced effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal women may relate, in part, to the induction of ovarian ablation by the cytotoxic drugs involved.12

Direct evidence

HRT in women with breast cancer

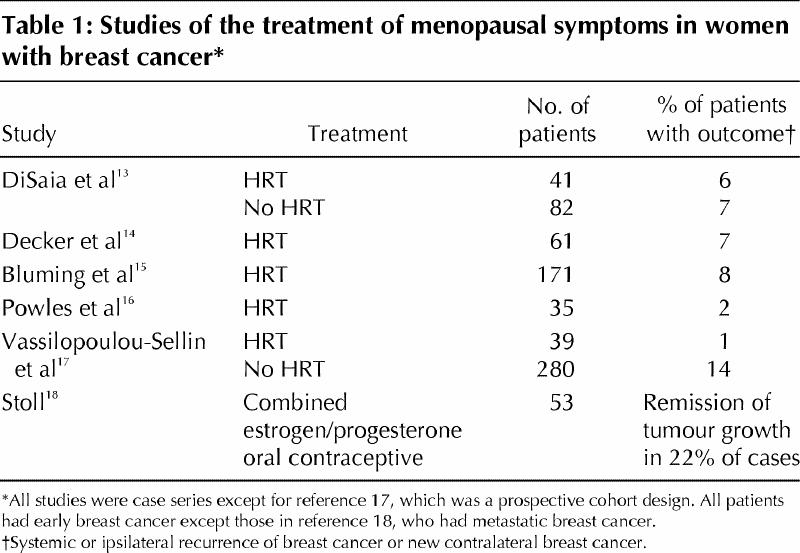

There have been 4 case series13,14,15,16 (level V evidence) and 1 cohort study17 (level III evidence) involving women with early breast cancer who were given HRT to relieve menopausal symptoms (Table 1). Alleviation of these symptoms was observed in all of the patients. None of these small studies showed any obvious increase in risk of breast cancer recurrence related to HRT. In another small series, women with advanced breast cancer received a combination of estrogen and progesterone as anti-cancer therapy18 (level V evidence).

Table 1

In addition to these case series, 3 case–control studies have been conducted. In one, 25 case subjects were matched with 50 control subjects; no adverse effect of HRT on cancer-related deaths was detected.19,20 In the second study a reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence was found in the HRT cohort, a result that may also be subject to potential bias from physician and patient selection of HRT.21,22 In the most recent study 174 women with breast cancer who took HRT were identified from 2755 women with breast cancer enrolled in an HMO (Health Maintenance Organization).23 Each HRT user was matched to 4 nonusers. The rates of breast cancer recurrence and death were statistically significantly lower among the HRT users than among the nonusers.

These reports show that data regarding HRT in women with breast cancer are scarce, that patients given HRT are probably highly selected and that these observations must be viewed as preliminary and uncontrolled. In addition, the mean follow-up time of published cases was relatively short, given that an increased risk of breast cancer in healthy women may be associated mainly with longer durations of HRT.

It is unknown whether the addition of tamoxifen to estrogen offers women with a history of breast cancer protection against any estrogen-induced increased risk of cancer recurrence. There are limited data on this issue. In a report by Powles and colleagues 2 of 35 women with breast cancer who took estrogen with tamoxifen experienced relapse (level V evidence).16 Marsden and colleagues reported on a pilot study involving 100 women with menopausal symptoms and early breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive HRT or no HRT for 6 months (level II evidence).24,25 One of the 29 women who were also taking tamoxifen had breast cancer recurrence.

Clinical trials

In considering trials of HRT use, one must recognize that women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer will not accept much increased risk of recurrence in order to take HRT.26,27 Three randomized trials are now underway. The HABITS study (opened in 1996), a second Swedish study (opened in 1998) and a British study (opened in 2001) are each assigning women with breast cancer to HRT or no HRT for 2 years. Until results from these randomized trials are available increased risk related to HRT for women with a prior diagnosis of breast cancer cannot be ruled out.

Alternatives to HRT

· Postmenopausal women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer who request HRT should be encouraged to consider alternatives to HRT. If menopausal symptoms are particularly troublesome and do not respond to alternative approaches, a well-informed woman may choose to use HRT to control these symptoms after discussing the risks with her physician. In these circumstances, both the dose and the duration of treatment should be minimized.

If HRT is to be considered, factors that may be included in the decision-making process include low-risk disease and long disease-free interval.

There are alternatives to the use of HRT in women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer to relieve menopausal symptoms and to prevent osteoporosis.28,29,30 Strategies to deal with menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis are briefly discussed here. In addition to describing approaches that are effective, some strategies that are of no benefit are also mentioned.

Menopausal symptoms

Vaginal dryness and local menopausal symptoms can be significantly reduced with the use of K-Y Jelly and Replens (level II evidence).31

Urogenital atrophy in women without breast cancer has been treated safely and effectively with estriol creams and estradiol vaginal rings (e.g., Estring) (level I evidence).32,33,34 In the case of creams, bolus systemic absorption of higher estrogen concentrations may occur from intermittent applications. Vaginal rings provide more controlled local delivery with their continuous release of very low doses of estradiol (< 10 mg/24 h), and the observed steady-state levels of systemic plasma concentrations have been found to be within the upper limits of those seen in untreated postmenopausal women.35

Hot flashes can be treated with a variety of nonhormonal therapies:

· Vitamin E: A placebo-controlled trial demonstrated that vitamin E (800 IU/d) achieved a statistically significant reduction in hot flashes over placebo (level I evidence).36 However, this reduction may have been due in part to a placebo effect, since the decrease amounted to 1 hot flash per person per day.

· Clonidine: In a placebo-controlled trial, clonidine reduced the frequency of hot flashes by about 15% compared with placebo (level I evidence),37 but it was associated with a statistically significant amount of toxicity. At the study's end patients did not prefer clonidine over placebo.

· Venlafaxine (Effexor): Low doses of venlafaxine (37.5 mg in a sustained-release preparation) substantially reduced the frequency of hot flashes and was well tolerated in a randomized trial (level I evidence).38

· Soy phytoestrogens: A recently completed placebo-controlled trial did not show that soy protein significantly reduced the severity or frequency of hot flashes when compared with placebo (level I evidence).39

· Other compounds: Compounds such as black cohash and Bellergal (a combination of belladonna, ergotamine and phenobarbital) have been used, but these have not undergone placebo-controlled trials to illustrate benefits and toxicities.

· Megestrol acetate: A placebo-controlled trial that evaluated a low dose of the progestational agent megestrol acetate demonstrated a reduction in the frequency of hot flashes by about 80% (level I evidence).40 The therapy was well tolerated in this short-term double-blind, crossover clinical trial, and women significantly preferred megestrol acetate over the placebo. However, many animal and in vitro studies have shown that progestational agents may increase or accelerate breast cancer development or progression, and progesterone has been clearly identified as a cause of breast cancer in women.2,3,4 As with estrogen, there are no good data to demonstrate whether low doses of megestrol acetate in women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer increase or decrease the risk of recurrence, or have no effect. Progestational agents should be regarded with the same degree of caution as estrogen when recommending treatment to patients with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis can now be prevented and treated with a number of approaches that do not involve estrogen or progesterone. Diet, exercise and appropriate calcium intake are important factors in the prevention of osteoporosis,41,42 and a wide array of bisphosphonates inhibit bone absorption and normalize bone turnover. Such agents have been used in women with breast cancer (level I evidence).43,44,45

Raloxifene, like tamoxifen, is a selective estrogen receptor modulator that has been approved recently for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. It provides somewhat less of a beneficial effect on bone density than HRT and does not relieve menopausal symptoms (level I evidence).46 Given that raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator, it could potentially affect breast cancer recurrence, but the direction and magnitude of any effect is unknown. Therefore, raloxifene cannot be routinely recommended to prevent osteoporosis in a woman with breast cancer.

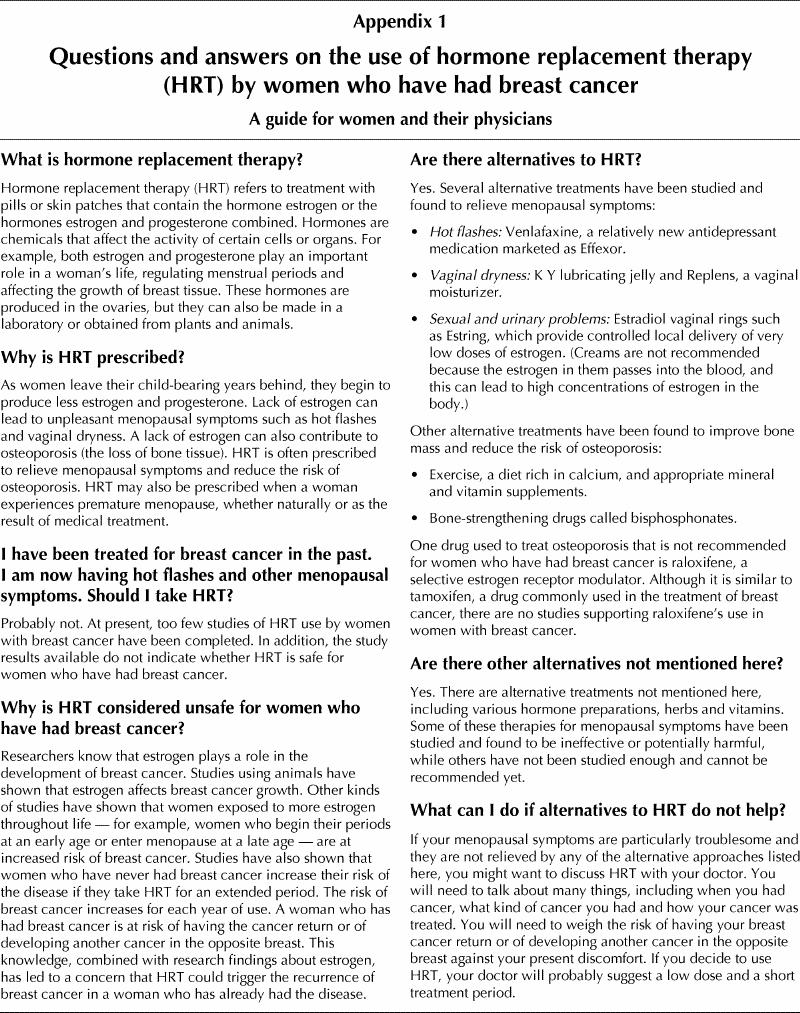

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

The steering committee is part of Health Canada's Canadian Breast Cancer Initiative. A list of the committee members appears at the end of the article.

A patient version of these guidelines appears in Appendix 1.

A patient guide to the use of hormone replacement therapy in women who have had breast cancer appears on page 1022.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Dr. Kathleen Pritchard was responsible for the initial draft of the manuscript. Ms. Humaira Khan performed extensive literature reviews. Dr. Mark Levine provided substantial editing for the various drafts of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Mark Levine, Rm. 9-90 Wing, Henderson Hospital, 711 Concession St., Hamilton ON L8V 1C3

References

- 1.Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest 1989;95(Suppl):2S-4S. [PubMed]

- 2.Clarke R, Johnson MD. Animal models. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p. 319-33.

- 3.Clarke R, Leonessa F, Brunner N, Thompson EW. In vitro models. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p. 335-54.

- 4.Kelsey JL. A review of the epidemiology of breast cancer. Epidemiol Rev 1979; 1: 74-109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Henderson BE, Ross R, Bernstein L. Estrogen as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Res 1988;48:246-53. [PubMed]

- 6.Trichopolis D, MacMahon B, Cole P. Menopause and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 1972;48:605-13. [PubMed]

- 7.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet 1997;350:1047-59. [PubMed]

- 8.Persson I, Weiderpass E, Bergkvist L, Bergstrom R, Schairer C. Risks of breast and endometrial cancer after estrogen and progestin replacement. Cancer Causes Control 1999;10:253-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Schairer C, Lubin J, Troisi R, Sturgeon S, Brinton L, Hoover R. Menopausal estrogen and estrogen–progestin replacement therapy and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2000;283:485-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Wan PC, Pike MC. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk: estrogen versus estrogen plus progestin. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:328-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Ovarian ablation in early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet 1996;348:1189-96. [PubMed]

- 12.Aebi S, Gelber S, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Collins J, Thurlimann B, et al. Is chemotherapy alone adequate for young women with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer? Lancet 2000;355:1869-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.DiSaia PJ, Grosen EA, Kurosaki T, Gildea M, Cowan B, Anton-Culver H. Hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:1494-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Decker D, Cox T, Burdakin J, Jaiyesimi I, Pettinga J, Benitez P. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in breast cancer survivors [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:209.

- 15.Bluming AZ, Waisman JR, Dosik GM, Olsen GA, McAndrew P, Decker RW, et al. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in women with previously treated primary breast cancer, update IV [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998;17:496.

- 16.Powles TJ, Hickish T, Casey S. Hormone replacement after breast cancer. Lancet 1993;342:60-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Asmar L, Hortobagyi GN, Klien MJ, McNeese M, Singletary SE, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy after localized breast cancer: clinical outcome of 319 women followed prospectively. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1482-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Stoll BA. Effect of lyndiol, an oral contraceptive, on breast cancer. BMJ 1967;1:150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wile AG, Opfell RW, Margileth DA, Anton-Culver H. Hormone replacement therapy does not affect breast cancer outcome [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1991;10:58.

- 20.Wile AG, Opfell RW, Magileth DA. Hormone replacement therapy in previously treated breast cancer patients. Am J Surg 1993;165:372-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Eden JA. A case controlled study of combined continuous estrogen–progestin replacement therapy among women with a personal history of breast cancer. Menopause 1995;2:67-72.

- 22.Eden JA, Wren BG, Dew J. Hormone replacement therapy after breast cancer. In: Educational book. Alexandria (VA): American Society of Clinical Oncology; 1996. p. 187-9.

- 23.O'Meara ES, Rossing MA, Daling JR, Elmore JG, Barlow WE, Weiss NS. Hormone replacement therapy after a diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to recurrence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:754-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Marsden J, Baum M, Jurkovic D, et al. A randomized pilot study of HRT in breast cancer patients: the combined effects of tamoxifen and HRT on the endometrium. Breast 1997;6:238-43.

- 25.Marsden J, Baum M, Whitehead MI, et al. A randomized trial of HRT in women with a history of breast cancer — a feasibility study [abstract]. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:22.

- 26.Ganz PA, Greendale G, Kahn B, O'Leary JF. Are breast cancer survivors (BCS) willing to take hormone replacement therapy (HRT)? [abstract] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:102.

- 27.Pritchard K, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Lewis J, Sawka CA, Franssen E, Del Guidice L, et al. The use of a probability trade-off task (PT-OT) to assess maximal acceptable increment in risk of breast cancer recurrence (MAIRR) in order to estimate sample size for a randomized clinical trial of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:213.

- 28.Loprinzi CL. Management of menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. In: Educational book. Alexandria (VA): American Society of Clinical Oncology; 1996. p. 190-2.

- 29.Kessel B. Alternatives to estrogen for menopausal women. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1998;217:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Chlebowski RT. Elements of informed consent for hormonal replacement therapy in patients with diagnosed breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:130-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Law M, Loprinzi CL, Veeder M, Rowland K, vanHaelst-Pisani C, Abu-Ghazaleh S, et al. Double-blind crossover trial of Replens versus KY Jelly for treating vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:534.

- 32.Casper F, Petri E. Local treatment of urogenital atrophy with an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring: a comparative and a placebo-controlled multicenter study. Int Urogynecol J 1999;10:171-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Barensten R, van de Weijer PH, Schram JH. Continuous low dose estradiol released from a vaginal ring versus estriol vaginal cream for urogenital atrophy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repr Biol 1997;71:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Ayton RA, Darling GM, Murkies AL, Farrell EA, Weisberg E, Selinus I, et al. A comparative study of safety and efficacy of continuous low dose oestradiol released from a vaginal ring compared with conjugated equine oestrogen vaginal cream in the treatment of postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:351-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gabrielsson J, Wallenbeck I, Birgerson L. Pharmacokinetic data on estradiol in light of the estring concept. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1996;163(Suppl):26-31. [PubMed]

- 36.Barton DL, Loprinzi CL, Quella SK, Sloan JA, Veeder MH, Egner JR, et al. Prospective evaluation of vitamin E for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:495-500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Goldberg RM, Loprinzi CL, O'Fallon JR, Veeder MH, Miser AW, Mailliard JA, et al. Transdermal clonidine for ameliorating tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:155-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan J, Mailliard A, LaVasseur B, Barton D, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet 2000;356:2059-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Quella SK, Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Knost JA, Sloan JA, LaVasseur BI, et al. Evaluation of soy phytoestrogens for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1068-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Loprinzi CL, Michalak JC, Quella SK, O'Fallon JR, Hatfield AK, Nelimark RA, et al. Megestrol acetate for the prevention of hot flashes. N Engl J Med 1994;331:347-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Nordin BEC. Calcium and osteoporosis. Nutrition 1997;13:664-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Prior JC, Barr SI, Chow R, Faulker RA. Physical activity as therapy for osteoporosis. CMAJ 1996;155(7):940-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Saarto T, Blomqvist C, Valimaki M, Makela P, Sarna S, Elomaa I. Chemical castration induced by adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and flurouracil chemotherapy use rapid bone loss that is reduced by clodronate: a randomized study in premenopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1341-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Powles TJ, McCloskey EV, Paterson AHG, Ashley S, Tidy A, Kanis J. Oral clodronate will reduce the loss of bone mineral density in women with a primary breast cancer [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997;16:130a.

- 45.Delmas PD, Balena R, Confravreux E, Hardouin C, Hardy P, Bremond A. Bisphosphonate risedronate prevents bone loss in women with artificial menopause due to chemotherapy of breast cancer: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:955-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Pritchard KI, Levine M, Walley B. Raloxifene: Handle with care [letter]. CMAJ 2001;165(2):151,153. [PMC free article] [PubMed]