Abstract

The role of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) employment specialist is a new type of occupation within mental healthcare. High turnover among employment specialists necessitates improvement in their recruitment and retention. One element that impacts retention is job satisfaction. We assessed the personality of 38 employment specialists (Big 5 Inventory‐2) and measured job satisfaction over three time periods. Compared to norm data, employment specialists were significantly higher on Extraversion (ΔT = 8.0, CI: 5.59–10.42), Agreeableness (ΔT = 7.8, CI: 5.56–10.12), Conscientiousness (ΔT = 3.3, CI: 0.8–5.84), Open‐mindedness (ΔT = 3.5, CI: 0.97–6.07), while lower on Negative emotionality (ΔT = −3.5, CI: −6.5 to −0.42). Extraversion had a substantial longitudinal positive effect on job satisfaction (β at T1 = 0.39; CI: 0.10–0.73) (β at T2 = 0.40; CI: 0.03–0.80), while Negative emotionality – a substantial negative effect (β at T1 = −0.60; CI: −0.90 to −0.30) (β at T2 = −0.50; CI: −0.90 to −0.12). Male gender was significantly associated with higher job satisfaction at the time point 1 (β = −0.46; CI: −0.80 to −0.14). Age, length of employment in the role, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness and Open‐mindedness were not found to have substantial significant effects on job satisfaction of employment specialists. Recruiting employment specialists who score high on Extraversion and low on Negative emotionality may be a good fit for the role and job satisfaction.

Keywords: Individual placement and support, employment specialists, recruitment, Big 5, job satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

It is a truth universally acknowledged (Austen, 1813) that a person in possession of a severe mental illness is not likely to be in want of a job. However, many studies indicate that at best this sentiment is misguided and at worst is willfully prejudiced: people with mental illness often state that work is central to their recovery (Iyer, Mangala, Jeyagurunathan, Thara & Malla, 2011; Ramsay, Broussard, Goulding et al., 2011). The question is whether the systems that provide care can collaborate to ensure that this goal is realized? More than 27 randomized controlled trials suggest so (Brinchmann, Widding‐Havneraas, Modini et al., 2019). The much messier subject of how this translates to the real world has been given far less space in academic journals. This paper reports on a study that explores one element of how the bridge from research to practice is crossed in the hope of providing guidance to government agencies, and health and employment services who may wish to follow.

Employment has been shown to improve the mental health and wellbeing of people with severe mental illness, including improved self‐esteem, symptom control and quality of life (Drake, Frey, Bond et al., 2013; Fossey & Harvey, 2010; Luciano, Bond & Drake, 2014). Furthermore, a meta‐analysis concluded that being employed is associated not just with mental health improvements, but also with a number of subjective functional and social benefits (Modini, Joyce, Mykletun et al., 2016). Despite the benefits of having paid work and the wish to be employed, a large proportion of people with severe mental illnesses do not (re‐)enter the workforce (Luciano & Meara, 2014; Marwaha, Johnson, Bebbington et al., 2007; McQuilken, Zahniser, Novak, Starks, Olmos & Bond, 2003; Waghorn, Saha Harvey et al., 2012; Westcott, Waghorn McLean Statham & Mowry, 2015).

Individual placement and support (IPS) is a vocational rehabilitation approach that helps people with severe mental illness to obtain and maintain paid employment (Bond Drake & Becker, 2012). IPS is more than twice as effective compared to other forms of vocational rehabilitation in achieving paid employment (Brinchmann, Widding‐Havneraas, Modini et al., 2019). The key implementation figure in the IPS process is the employment specialist.

The role of IPS employment specialists entails providing people with severe mental illness direct assistance in searching, gaining and retaining a job through continuous support (Drake, Bond & Becker, 2012). To achieve their professional goals, employment specialists must work closely with local employers and be integrated with clinical teams. Interaction with clinicians and employers puts different practical demands on employment specialists: communication with clinicians requires an understanding of mental health and the mental health system, while interaction with employers entails presenting skills and the abilities of job seekers with severe mental illness (Moen, Walseth & Larsen, 2021). [Corrections made on 29 August 2022, after first online publication: In‐text citation and reference details for the preceding statement have been corrected in this version.] IPS requires knowledge and skills in establishing an individualized job searching process based on the person's preferences, and follow‐up support once the person has gained employment (Corbiere, Brouwers, Lanctot & van Weeghel, 2014; Teixeira, Rogers, Russinova & Lord, 2020; Whitley, Kostick & Bush, 2010).

Despite the variety of practical demands that an IPS employment specialist has along with the different settings and systems in which they have to operate, their position does not require a specific occupational background, nor does it entail a formal educational qualification, instead it mainly relies on a learning by doing principle. In addition, there is no established evidence‐based framework for the recruitment and selection of candidates for the role. Despite the absence of strict recruitment criteria, we assume that a two‐way process occurs between employers and job seeking candidates for the employment specialist position. Employers may have a preferred type of personality for employment specialists that they would tend to search for among the candidates. While the role would naturally attract people with a specific personality profile based on the description of job duties and work setting.

In the context of the IPS, we hypothesize that the employment specialist role attracts people with high extraversion as their job entails active interactions with different groups of people, the continuous establishment of relationships and networking, high mobility, and advocating for people with severe mental illness. Extraversion is defined as an “energetic approach toward the social and material world” (John, 2021, p. 42). Facets that constitute this and other domains and their hierarchy are still debated in the research community (DeYoung, Quilty & Peterson, 2007; Hofstee, de Raad & Goldberg, 1992; Roberts, Bogg, Walton, Chernyshenko & Stark, 2004; Saucier & Ostendorf, 1999; Soto & John, 2017). The Big 5 Inventory 2 (BFI‐2) scale entails three major facets of extraversion: sociability, assertiveness, and energy level (Soto & John, 2017). A recent quantitative review of 97 meta‐analyses concludes that high extraversion provides motivational, emotional, interpersonal and performance advantages to the individuals (Wilmot, Wanberg, Kammeyer‐Mueller & Ones, 2019).

Agreeableness is a trait that “contrasts a prosocial and communal orientation toward others with antagonism and hostility”. It includes compassion, respectfulness, and trust, which are major facets in the BFI‐2 (John, 2021, p. 42). Agreeable individuals are characterized by good interpersonal facilitation (Hurtz & Donovan, 2000), benevolent behaviour (Soto & John, 2017) in exchange for higher vulnerability to being exploited (Nettle, 2006). A second order meta‐analysis concluded that this trait is especially important for performance in interpersonal jobs (He, Donnellan & Mendoza, 2019). We hypothesize that employment specialists score higher on agreeableness compared to the general population as their role is humanistic and recovery oriented in its nature, requiring adaptive social behaviors anchored in compassion and respectfulness. Second, as their role entails facilitation of interactions within and between clients, employers and clinicians.

Though the employment specialist role might naturally attract people with a described personality profile, we are unaware of any evidence in the IPS literature that any of Big 5 traits or facets are beneficial for the role. If found so, this knowledge could be helpful during the recruitment and selection of candidates on the usefulness of particular traits in this role. Improving hiring process is one of the suggested ways of dealing with turnover (O'Connell & Kung, 2007), that has been reported as being high among employment specialists (Butenko, Rinaldi, Brinchmann et al., 2022; Vukadin, Schaafsma, Michon, de Maaker‐Berkhof & Anema, 2021). A way of investigating which personality features are beneficial for a role is to study an association between them and job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction is a key concept in occupational psychology (Dalal & Credé, 2013). Job satisfaction is found to be associated with various personality traits (Bruk‐Lee, Khoury, Nixon, & Spector, 2009; Judge, Heller & Mount, 2002b; Steel, Schmidt, Bosco & Uggerslev, 2019), and to productivity and turnover (Riketta, 2008; Tett & Meyer, 1993) in broad occupational groups. Job satisfaction and associated facets have been found to be directly associated with higher turnover intentions of IPS employment specialists, as such showing the importance of maintaining high job satisfaction for the retention of the service providers (Butenko, Rinaldi, Brinchmann et al., 2022). Though as of now, it is unclear which factors are associated with job satisfaction for IPS employment specialists.

Recruitment of employment specialists is about trying to guess who might be satisfied with the job in the demanding role as employment specialist. Consequently, we aim to investigate how personality profiles measured shortly after recruitment to the employment specialist role is associated with job satisfaction several months into the job.

The aims of this study are:

To investigate the difference between personality profile of IPS employment specialists and the general population.

To investigate the association between Big 5 personality traits, demographic factors and general job satisfaction of IPS employment specialists several months in the role.

METHODS

Design

This longitudinal survey‐based cohort study was conducted during 2019–2020 in Nordland, Troms and Finnmark counties in Northern Norway. It is a part of a large naturalistic trial IPSNOR that studies the effectiveness of the implementation of IPS.

Setting

The majority of IPS employment specialists in Norway are employed by the Public Employment Service (Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration [NAV]) which is responsible for the provision of vocational services and social welfare benefits. All IPS employment specialists including the minority not employed by NAV work closely with the agency in terms of supporting IPS clients whilst also being integrated with mental health services.

Data collection instruments

A number of self‐made items were used to collect demographic data. An officially translated Norwegian version of the BFI‐2 scale was used to assess personality of employment specialists (Soto & John, 2017). BFI‐2 is a 60‐item hierarchically structured scale that assesses five personality domains and corresponding 15 facets. The Job in General (JIG) scale was used to measure job satisfaction (Gillespie et al., 2016). JIG is a self‐report global job satisfaction scale, meaning that it grasps general satisfaction with a job, regardless of its type. It consists of 18 adjectives describing a job in general with a Likert scale three‐item response. Reliability and validity of this instrument was demonstrated in a systematic review (Van Saane, Sluiter, Verbeek & Frings‐Dresen, 2003).

A Norwegian version of the JIG did not exist. To translate the JIG, a forward and back translation with a following comparison was conducted by a bilingual expert panel. At the first stage, a forward translation was conducted by a junior team member fluent in both English and Norwegian. Afterwards it was revised by a senior researcher, experienced in English‐Norwegian translation and adaptation of questionnaires. At the second stage a team member who has not seen the original version back‐translated the scale from Norwegian. Finally, the original English and back‐translated versions were compared, and minor inaccuracies were discussed and edited in an expert panel meeting. During the baseline data collection the translated version of JIG was pre‐tested with help of the target population. The respondents made no comments regarding the translation. The JIG authors gave permission for the scale to be translated into Norwegian but were unable to comment on the quality of the translation.

Sample

In this study we attempted to survey the whole population of IPS employment specialists in Northern Norway. Forty employment specialists initially provided consent to be surveyed representing 88.9% of the total number of employment specialists in Northern Norway during the study period.

Data collection

Baseline data collection (T0) of Big 5 personality profiles took place in September 2019 during an educational seminar with employment specialists. Demographic information and Big 5 personality profiles were collected via SurveyMonkey platform.

Job satisfaction data was collected via JIG at three time points – in February 2020 (T1), July 2020 (T2) and October 2020 (T3). One week after each initial request, we personally contacted non‐respondents encouraging them to complete the questionnaire. Those who did not fill in the questionnaire after the initial reminder were contacted a second time.

Statistics

Z‐scores for BFI‐2 domains of employment specialists were calculated, using BFI‐2 normative data and individual raw scores. Normative data for the BFI‐2 scale from the demographically representative US adult sample was obtained from the author of the scale and can be found in the referenced article in supplementary materials (Soto, 2019). The formula used for calculating Z‐scores was Z = (X ‐ μ) /σ, where X is raw score, μ – population mean and σ – standard deviation. T‐scores were calculated consequently according to the T = 50 + 10Z formula, where Z is the Z score.

A one‐sample t‐test was used to calculate the difference between means of T‐scores of employment specialist Big 5 personality and normative data. MS Excel v2016 (16.0.5173.1000) was used to visualize the difference between average Big 5 profile of employment specialists and normative data.

A linear regression analysis was used to investigate the association between Big 5 personality traits and general job satisfaction of IPS employment specialists. For the analysis we have used JIG data from T1 and T2 time points as outcomes. We did not use T3 data due to decreased response rate which would increase the probability of results being affected by a type 2 error. We standardized included variables to enable estimate confidence intervals for individual effects of predictors on the outcome and to be able to compare strength of effects between the models. To perform the analysis in the first place we estimated individual effects of factors‐predictors on general job satisfaction by making bi‐variable linear regression models. We included demographic variables in the analysis and found a significant individual effect for gender on general job satisfaction and adjusted the primary bi‐variable models for gender as a possible confounder. SPSS v27 was used to perform analysis.

RESULTS

Demographical characteristics of the IPS employment specialists who provided their consent to participate in the study are presented in Table 1. Age was calculated as a difference between the year of birth and the year of our first data collection at T0 (2019). Length of time as IPS employment specialist was calculated in months as a difference between the month of the respective data collection and the month they started their job.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Number of participants | n = 40 |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD, range) | Mean = 41.7; SD = 8.2; R = 26–58 |

| Gender (% of women) | 62.5% |

| Length of time as IPS employment specialist (mean, SD, range in months) |

Mean at T0 = 9.0; SD = 8.8; R = 0–32 Mean at T1 = 14.0; SD = 8.0; R = 5–34 Mean at T2 = 19.0; SD = 8.3; R = 10–39 |

| Previous work experience (n, %) | |

| Health sector | n = 9 (22.5%) |

| Labour and welfare administration (NAV) | n = 10 (25.0%) |

| Both health sector and Labor and welfare administration (NAV) | n = 8 (20.0%) |

| Other | n = 8 (20.0%) |

| Missing data | n = 5 (12.5%) |

Response rate at T0 was 95% out of those who provided their written consent to participate, at T1–85.0%, at T2–67.5%, at T3–60.0%.

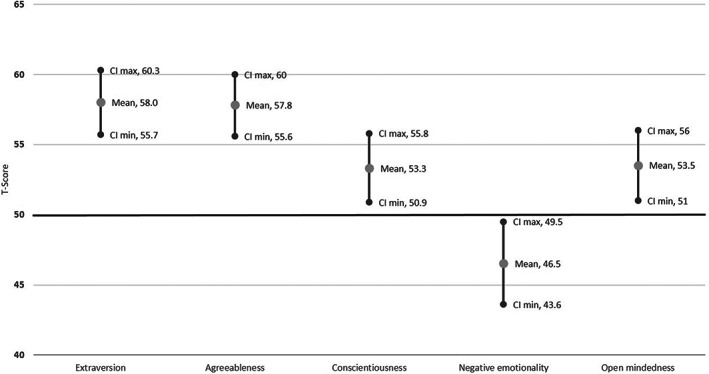

Using a one sample t‐test we found there was a significant difference in T‐scores of all Big 5 domains between the sample of employment specialists and normative data (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The biggest differences were observed in Extraversion (ΔT = 8.0, CI: 5.59–10.42, p < 0.001), and Agreeableness (ΔT = 7.8, CI: 5.56–10.12, p < 0.001). Modest differences were observed in Conscientiousness (ΔT = 3.3, CI: 0.8–5.84, p = 0.011), Neuroticism (ΔT = −3.5, CI: −6.5 to −0.42, p = 0.027), Open‐mindedness (ΔT = 3.5, CI: 0.97–6.07, p = 0.008). Figure 1 displays differences in T‐scores of Big 5 domains between employment specialists sample and normative US data.

Table 2.

BFI‐2 Big 5 personality domains T‐scores of IPS employment specialists', compared to US norm data

| N | t | ΔT | SD | Std. Error Mean | 95% CI | Sig.(2‐tailed) p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Extraversion | 38 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 7.34 | 1.19 | 5.59 | 10.42 | <0.001 |

| Agreeableness | 38 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 6.94 | 1.13 | 5.56 | 10.12 | <0.001 |

| Conscientiousness | 38 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 7.66 | 1.24 | 0.8 | 5.84 | 0.011 |

| Negative emotionality (Neuroticism) | 38 | −2.3 | −3.5 | 9.25 | 1.50 | −6.5 | −0.42 | 0.027 |

| Open‐mindedness | 38 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 7.76 | 1.26 | 0.97 | 6.07 | 0.008 |

Fig. 1.

T‐scores and confidence intervals of BFI‐2 Big 5 personality domains of IPS employment specialists sample. Note. Bold black line at the 50th T‐score stands for the average Big 5 personality profile from the BFI‐2 normative data.

Using a linear regression analysis, we found that male gender had a statistically significant positive effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (model 2) (β = −0.46; CI: −0.80 to −0.14) (Table 3). At T2 the effect of male gender was positive, but not statistically significant (β = −0.40; CI: −0.80 to 0.03). Age was found to have no substantial, statistically significant effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (model 1) (β = 0.11; CI: −0.30 to 0.50) and at T2 (β = −0.06; CI: −0.50 to 0.40). Length of time as IPS employment specialist at T1 was found not to have a substantial, statistically significant effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (model 3) (β = −0.10; CI: −0.50 to 0.40), and at T2 (model 4) (β = 0.13; CI: −0.34 to 0.60).

Table 3.

Individual linear regression models showing unadjusted effects of demographic and personality factors on job satisfaction (outcome a) and effects of demographic and personality factors adjusted for gender on job satisfaction (outcome b) at T1 and T2 time points

| Job satisfaction (outcome a) β (in bold), 95% CI | Job satisfaction adjusted for gender (outcome b) β (in bold), 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

|

Age at T0 (model 1) |

0.11 −0.30 to 0.50 |

−0.06 −0.50 to 0.40 |

0.10 −0.30 to 0.40 |

−0.12 −0.53 to 0.30 |

|

Gender (model 2) |

−0.46* −0.80 to −0.14 |

−0.40 −0.80 to 0.03 |

– | – |

|

Length of time as IPS ES at T1 (model 3) |

−0.10 −0.50 to 0.40 |

– |

−0.03 −0.40 to 0.33 |

– |

|

Length of time as IPS ES at T2 (model 4) |

– |

0.13 −0.34 to 0.60 |

– |

0.11 −0.34 to −0.60 |

|

BFI‐2 Extraversion (model 5) |

0.39* 0.10–0.73 |

0.40* 0.03–0.80 |

0.30 −0.01 to 0.61 |

0.40* 0.02–0.73 |

|

BFI‐2 Agreeableness (model 6) |

−0.10 −0.50 to 0.30 |

0.02 −0.41 to 0.50 |

0.01 −0.32 to 0.40 |

0.10 −0.40 to 0.50 |

|

BFI‐2 Conscientiousness (model 7) |

−0.04 −0.41 to 0.33 |

−0.12 −0.54 to 0.30 |

0.10 −0.30 to 0.40 |

0.01 −0.42 to 0.43 |

|

BFI‐2 Negative Emotionality (model 8) |

−0.60* −0.90 to −0.30 |

−0.50* −0.90 to −0.12 |

−0.50* −0.80 to −0.14 |

−0.42* −0.81 to −0.03 |

| BFI‐2 Open‐Mindedness (model 9) |

0.04 −0.40 to 0.44 |

0.30 −0.30 to 0.80 |

0.10 −0.30 to 0.41 |

0.30 −0.25 to 0.80 |

Note: * smarks statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

In bi‐variable models, Extraversion (model 5) had a positive statistically significant effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (β = 0.39; CI: 0.10–0.73) and at T2 (β = 0.40; CI: 0.03–0.80). Negative emotionality (model 8) was found to have a negative statistically significant effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (β = −0.60; CI: −0.90 to −0.30) and at T2 (β = −0.50; CI: −0.90 to −0.12).

After adjusting for gender, Extraversion (model 5) had a positive but not statistically significant effect on general job satisfaction at T1 (β = 0.30; CI: −0.01 to 0.61) and positive statistically significant effect at T2 (β = 0.40; CI: 0.02–0.73). Negative emotionality (model 8) adjusted for gender had a negative statistically significant effect both at T1 (β = −0.50; CI: −0.80 to ‐0.14) and at T2 (β = −0.42; CI: −0.81 to −0.03).

In bi‐variable models Agreeableness (model 6) (T1 β = −0.10; CI: −0.50 to 0.30) (T2 β = 0.02; CI: −0.41 to 0.50), Conscientiousness (model 7) (T1 β = −0.04; CI: −0.41 to 0.33) (T2 β = −0.12; CI: −0.54 to 0.30), and Open‐mindedness (T1 β = 0.04; CI: −0.40 to 0.44) (T2 β = 0.30, CI: −0.30 to 0.80) were found not to have substantial, statistically significant effects on general job satisfaction at both T1 and T2. There was no substantial change in effect sizes of these personality traits on general job satisfaction after the models were adjusted for gender as a potential confounder.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the personality profile of IPS employment specialists and its association to job satisfaction. Compared to a representative sample of US adults, IPS employment specialists in our study were significantly lower on Negative emotionality, while higher on Extraversion, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness and Open‐mindedness. The biggest difference (>1 SD difference) was observed for Extraversion and Agreeableness.

We found that male gender was positively statistically significantly associated with general job satisfaction of IPS employment specialists at T1. Among the five factors of the Big 5 personality model, Extraversion had a positive, while Negative emotionality had a negative longitudinal statistically significant effects on IPS employment specialists' general job satisfaction. When adjusted for gender, Negative emotionality and Extraversion's effects on general job satisfaction did not substantially change, though at the first time point confidence interval of the effect of Extraversion on job satisfaction widened, making the effect statistically insignificant.

Age, length of time as IPS employment specialist, and three personality factors – Agreeableness, Conscientiousness and Open‐mindedness, were found not to have an effect on general job satisfaction of the participants.

Interpretation of findings on personality profile

Different occupations attract different personalities based on the setting and responsibilities of a particular job (Ackerman & Beier, 2003). Being an interpersonal humanistic job that presupposes social facilitation, the role of an IPS employment specialist attracts people high on Extraversion and Agreeableness. It is plausible to conclude that to be comfortable with continuous interaction with clients, employers, clinicians and other social care workers, IPS employment specialists have to be sociable, outgoing and energetic. Assertiveness and respectfulness are needed to communicate and advocate the employment interests, experience and skills of people with severe mental illness to employers. Resolving interpersonal conflicts, encouraging clients when failure occurs, and supporting them by provision of hope and trust relies on skills grounded in the interplay of these traits.

We assume that the individual responsibility of IPS employment specialists in organizing and structuring the process of gaining employment for clients is a task that attracts people high in Conscientiousness. Conscientiousness stands for “socially prescribed impulse control that facilitates task‐ and goal‐directed behavior” (John, 2021, p. 42). In work related settings people with high Conscientiousness were reported to be more self‐efficient (Burke, Matthiesen & Pallesen, 2006; Hartman & Betz, 2007; Judge, Bono, Ilies & Gerhardt, 2002a) and better in general self‐management (Gerhardt, Rode & Peterson, 2007). Besides, such people are less influenced by situational constraints (Gerhardt et al., 2007) and perceived stress (Besser & Shackelford, 2007). The necessity to manage oneself in terms of time and tasks while handling individual cases that are at different stages of employment calls for thoroughness and self‐organization that are inherent for high Conscientiousness. Combined with high emotional stability that comes with low Neuroticism, high Conscientiousness results in better self‐regulation (Hoyle & Davisson, 2021; McCrae & Löckenhoff, 2010). In turn, self‐regulation of negative emotions such as anger or anxiety is a crucial element of smooth social interaction.

The position of an IPS employment specialist can be challenging in several ways. At an organizational level, some IPS employment specialists can lack resources, such as defined offices in healthcare centers with limited or no access to patient records (Moe, Brinchmann, Rasmussen et al., 2021. In addition, clinicians can be ambivalent towards or even opposing the idea of employment of clients, discouraging employment specialists (Marwaha, Balachandra & Johnson, 2009; Rinaldi, Miller & Perkins, 2010). Considering there is evidence of higher levels of stress and burnout among social care workers (Beer, 2016; Lloyd, King & Chenoweth, 2002), a high frustration threshold and emotional stability associated with low Neuroticism might be beneficial for the role of an IPS employment specialist. As people who score high on Neuroticism might have a tendency to leave their roles, it can be assumed that IPS employment specialists with the observed profile are less prone to leaving their jobs (Zimmerman, 2008). Low scores of Neuroticism also would be beneficial specifically for the IPS employment specialist role as scoring high on this trait was previously linked to social anxiety (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt & Watson, 2010). Based on this it is plausible to assume that a high score on Negative emotionality could mean that IPS employment specialists might find it distressing to work in such a social occupation.

There can be several explanations for high Open‐mindedness of IPS employment specialists. Open‐mindedness “describes the breadth, depth, originality, and complexity of the person's mental and experiential life” (John, 2021, p. 42). First, this job entails developing a personalized approach to a client and jointly creating an individual employment plan – tasks, relying in part on creativity. Secondl Open‐mindedness has previously been found to be negatively associated with conservatism (McCrae & Terracciano, 2005; Van Hiel, Kossowska & Mervielde, 2000; Van Hiel & Mervielde, 2004). The idea of the rehabilitation of people with severe mental illnesses through paid employment is still perceived by some as new and progressive. Given that the principles of IPS are liberal and humanistic in their nature, people becoming IPS employment specialists have to be open‐minded to the idea of rehabilitation, recovery and supporting a person's right to work through paid employment.

Interpretation of findings on the association between personality traits, gender and general job satisfaction

High Extraversion and low Negative emotionality were found to be longitudinally associated with general job satisfaction among IPS employment specialists. There was no substantial change in effect size for the traits on general job satisfaction after the adjustment for gender and we conclude that in our sample gender was not a confounder of the traits' effects on general job satisfaction.

The person‐job fit theory has merit to explain the relation between high Extraversion and job satisfaction in the context of IPS employment specialists' (Edwards, 1991). This theory implies that if a person and an occupation fit, better outcomes for both can be expected. Accordingly, those IPS employment specialists who score high on Extraversion are more satisfied with the job as they fit into the occupational environment that revolves around a high level of interpersonal interactions and requires the continuous establishment of new social contacts.

Negative emotionality, we do not believe that the observed association with general job satisfaction is specific to the occupation. As being low on this trait means being more tolerant to frustrations and less emotionally volatile (John, 2021, p. 42), it is most likely that such individuals would be more satisfied with any occupation and life in general (Judge et al., 2002b; Steel et al., 2019).

Our findings while being new in the IPS literature correspond with previous studies in occupational psychology. Three meta‐analyses explored association between job satisfaction and Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism (Bruk‐Lee et al., 2009; Judge et al., 2002b; Steel et al., 2019), and of course, these associations will vary between occupations. The observed associations between personality profiles and job satisfaction in our study of IPS employment specialists correspond with similar findings in other occupations, whereas others do not.

Regarding the gender effect on general job satisfaction, we surmise that the widened confidence interval at T2 can be explained by the decreased survey participation of respondents, which resulted in a lack of statistical power and increased possibility of a type 2 error. We found a positive association between male gender and general job satisfaction, what corresponds with our previous study, which showed a positive association between female gender and turnover intentions (Butenko, Rinaldi, Brinchmann et al., 2022). Future research with larger sample sizes could address the role of gender in relation to job satisfaction along with age and length of time in role as IPS employment specialist.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

As far as we know this is the first study to investigate the personality traits of IPS employment specialists and link them to job satisfaction. Overall, we were able to obtain informed consents for participation in a study from 88.9% of the total population of IPS employment specialists in Northern Norway at the time of the study. Among them, the response rate was 95% at the first data collection, 85% – at the second, 67.5% – at the third and 60% – at the fourth. For a survey‐based research, we were able to reach a response rate that was higher than 52.7%, which is considered to be average for individual responses (Baruch & Holtom, 2008). The decrease in the response rate was partially due to research participation fatigue, partially due to turnover of the IPS employment specialists in the sample and probably that the COVID‐19 pandemic occurred during data collections. To minimize the effect of common method bias a number of measures were taken at different stages of study. First, we chose a validated reliable scale to measure Big 5 personality domains. This scale contains reverse coded items and Likert scales, which are considered to be ways of mitigating common methods bias (Jordan & Troth, 2019). We have used an officially translated version of the BFI‐2, while the translation for JIG we applied translation and back translation method with following comparison, evaluation and pre‐testing. To increase accuracy of responses we provided respondents with explicit explanation about the purpose of the research and instructed them regarding surveying procedure. To prevent acquiescent response bias, we have checked collected survey data at the stage of analysis. There were no respondents whose answers would be consistently showing agreement or disagreement with the questionnaire items regardless of their content. In addition, we attempted to reduce social desirability bias by communicating to respondents that there was no gain, risk or reward related to their responses. A final strength of our study is the longitudinal design that allowed us to dynamically study the relation between Big 5 personality traits and general job satisfaction.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. Even though we were able to include the majority of IPS employment specialists working in Northern Norway the overall sample size was relatively small, thus resulting in wide confidence intervals and an increased risk of type‐2 errors. Therefore, the novel IPS field findings of this study warrant further investigation with a larger sample size. Another disadvantage is that we have used normative data for the BFI‐2 from a US sample. Even though the normative data was collected from a demographically representative sample, average personality profiles might differ across countries. Ideally, we believe that a sample should be compared to a representative sample of the same population. However, there was no available normative data for the BFI‐2 for Norwegian or any northern European representative sample at the time of the study.

Another limitation that we faced was despite overall relatively high response rate, the number of respondents decreased over time, so that at T3 number of observations was not sufficient to conduct the analysis.

Finally, as the data collection at T2 occurred during the COVID‐19 pandemic, social distancing regulations implemented in Norway might have affected strength of associations between personality domains and job satisfaction. It is plausible to assume that IPS employment specialists from our sample found to be high on Extraversion could have been less satisfied with their job due to the decreased number of face to face meetings with colleagues, clients and employers. While on the contrary the negative association between Negative emotionality and job satisfaction might have strengthened as those high on the trait were recently found to experience more negative affect during the pandemic (Kroencke, Geukes, Utesch, Kuper & Back, 2020).

Practical implications

Our findings on the personality profile of IPS employment specialists and the association between high Extraversion and low Negative Emotionality traits with high general job satisfaction could be useful for successful recruitment, retention and management of IPS employment specialists. Particularly, during the process of recruiting potential candidates for the IPS employment specialists' role, emphasis could be made on the advantages of high Extraversion and low Neuroticism as these two traits were longitudinally associated with general job satisfaction. High Agreeableness was found in our sample to be higher by one standard deviation from the general population has theoretical merit to be valuable for performance in an interpersonal type of job (He et al., 2019).

Whereas some occupations practice personality screening in the recruitment process, we are not convinced this would be welcomed in the process of recruiting IPS employment specialists. The findings from this study on the personality traits of IPS employment specialists should not become an ultimate “sieve” for recruiting IPS employment specialists as there are potentially other factors which make a good job fit for the role. There is, however, an emphasis on recruiting people who will be a good job fit in the recruitment for any job, including when recruiting to the role of an IPS employment specialist. It is possible when advertising jobs to mention what type of person may be suitable for the role, and this could also be tested during interviews.

The role of an IPS employment specialist demands the ability to engage and empower people with severe mental illness, work closely with mental health professionals, with public employment services and work proactively with employers. The role is prosocial, facilitative, relational, and continually advocates the recovery goals of employment to mental health professionals and the strengths of the client to employers – a role almost needing “a blind belief that anyone can work given the right help and support.” It is therefore not surprising to find that IPS employment specialists score higher on Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness and Open‐mindedness and lower on Negative emotionality. The latter construct is important in terms of maintaining optimism and hope. In the day‐to‐day role of an IPS employment specialist they can experience negative attitudes of mental health professionals about whether it is realistic for their clients to gain employment and the job search/development process which demands cold‐calling employers by approaching them directly on behalf of clients often results in negative responses. As such the role requires a high degree of optimism, tactfulness, and resilience.

While personality constructs play a role it should be recognized that there are other potential contributors to job satisfaction for IPS employment specialists. For example, work related factors such as caseload size and complexity, local labor markets, relational or system and process issues relating to being integrated with clinical teams and the public employment service. Other factors outside of work include illness, family issues and salary and working hours can all impact on job satisfaction.

Finally, our findings of the personality profile of IPS employment specialists and the discussion of the differences between personality traits of the sample and the reference data, creates a theoretical foundation for future research on the importance of certain personality domains and facets for other than job satisfaction outcomes of interest. Previously, one study explored the relation between Big 5 traits and employment outcomes of IPS clients. They showed that there were no relation between employment outcomes of clients and Conscientiousness of IPS employment specialists measured via the 10‐item International Personality Item Pool Conscientiousness Scale (Taylor & Bond, 2014). We hypothesize that combination of high Extraversion, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness have theoretical merit to be associated with higher effectiveness (clients in employment) of IPS employment specialists. While a combination of higher Extraversion and Agreeableness with low Negative emotionality might be beneficial for a better quality of working alliances with clients and better performance in establishing effective networks with employers and healthcare workers.

CONCLUSION

IPS employment specialists are more extravert, agreeable, conscientious, open‐minded than US norm data from the general population, and lower on Negative emotionality. Such a personality profile describes a highly mobile, social type of occupation that is oriented towards helping people with severe mental illness to achieve paid employment and vocational recovery. High Extraversion and low Negative emotionality were found to be longitudinally associated with higher general job satisfaction. These findings are novel for research on the role of the employment specialist in IPS, and they have merit to improve successful recruitment and retention of employment specialists. We suggest that this obtained knowledge could be used in the recruitment and selection of candidates in a form of a discussion about personal fit for the role, with emphasis on advantages of aforementioned personality traits. Further studies on the IPS employment specialist role, including productivity, turnover and subjective attitudes towards the work environment, should include personality measures.

This study received an ethics approval #123711 from The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics region North, Norway. A data protection officer from Nordland Hospital HF according to the GDPR regulation approved the data protection precautions. The case was assigned #2019/5454. All participation was based on informed consents.

This study is funded by research grants from the Research Council of Norway: 273665 and 280589.

The authors followed The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.

The authors express their gratitude to all IPS staff in Northern Norway. We also want to express our gratitude to several individuals who provided their help and expertise. Unni Kolstad, Centre for work and mental health, Nordland Hospital trust, Bodø, Norway – for reaching out non‐respondent survey participants in order to increase response rates. Marit Borg, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, University of South‐Eastern Norway, Norway – for providing expertise in the translation of the questionnaire. Rolf Gjestad, Centre for Research and Education in Forensic Psychiatry, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; Division of Psychiatry, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway – for providing statistical expertise. Sina Wittlund, Centre for work and mental health, Nordland Hospital trust, Bodø, Norway – for providing help in the translation of the questionnaire.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data is not available due to the GDPR regulations and conditions of ethics approval.

References

- Ackerman, P.L. & Beier, M.E. (2003). Intelligence, personality, and interests in the career choice process. Journal of Career Assessment, 11, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, J. (1813). Pride and prejudice: A novel. In three volumes: By the author of sense and sensibility . London: Printed for T. Egerton, Military Library, Whitehall. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9934876383602122 [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y. & Holtom, B.C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, O. (2016). Predictors of and causes of stress among social workers: A national survey [MSc thesis, University of Plymouth].

- Besser, A. & Shackelford, T.K. (2007). Mediation of the effects of the big five personality dimensions on negative mood and confirmed affective expectations by perceived situational stress: A quasi‐field study of vacationers. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, G.R. , Drake, R.E. & Becker, D.R. (2012). Generalizability of the individual placement and support (IPS) model of supported employment outside the US. World Psychiatry, 11, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinchmann, B. , Widding‐Havneraas, T. , Modini, M. , Rinaldi, M. , Moe, C.F. , McDaid, D. et al. (2019). A meta‐regression of the impact of policy on the efficacy of individual placement and support. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(3), 206–220. 10.1111/acps.13129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruk‐Lee, V. , Khoury, H.A. , Nixon, A.E. , Goh, A. & Spector, P.E. (2009). Replicating and extending past personality/job satisfaction meta‐analyses. Human Performance, 22, 156–189. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, R.J. , Matthiesen, S.B. & Pallesen, S. (2006). Personality correlates of workaholism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Butenko, D. , Rinaldi, M. , Brinchmann, B. , Killackey, E. , Johnsen, E. & Mykletun, A. (2022). Turnover of IPS employment specialists: Rates and predictors. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 57(1), 23–32. 10.3233/jvr-221195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere, M. , Brouwers, E. , Lanctot, N. & van Weeghel, J. (2014). Employment specialist competencies for supported employment programs. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24, 484–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, R.S. & Credé, M. (2013). Job satisfaction and other job attitudes. In Geisinger K.F. (Ed.), APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology, vol. 1: Test theory and testing and assessment in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 675–691). NE Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C.G. , Quilty, L.C. & Peterson, J.B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 880–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R.E. , Bond, G.R. & Becker, D.R. (2012). Individual placement and support: An evidence‐based approach to supported employment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R. E. , Frey, W. , Bond, G. R. , Goldman, H. H. , Salkever, D. , Miller, A. et al. (2013). Assisting social security disability insurance beneficiaries with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression in returning to work. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R. (1991). Person‐job fit: A conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. In Cooper C.L. & Robertson I.T. (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology, 1991 (Vol. 6, pp. 283–357). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Fossey, E.M. & Harvey, C.A. (2010). Finding and sustaining employment: A qualitative meta‐synthesis of mental health consumer views. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77, 303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, M.W. , Rode, J.C. & Peterson, S.J. (2007). Exploring mechanisms in the personality‐performance relationship: Mediating roles of self‐management and situational constraints. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, M.A. , Balzer, W.K. , Brodke, M.H. , Garza, M. , Gerbec, E.N. , Gillespie, J.Z. et al. (2016). Normative measurement of job satisfaction in the US. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31, 516–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, R.O. & Betz, N.E. (2007). The five‐factor model and career self‐efficacy: General and domain‐specific relationships. Journal of Career Assessment, 15, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. , Donnellan, M.B. & Mendoza, A.M. (2019). Five‐factor personality domains and job performance: A second order meta‐analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 103848. 10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstee, W.K. , de Raad, B. & Goldberg, L.R. (1992). Integration of the big five and circumplex approaches to trait structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 146–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. & Davisson, E.K. (2021). Self‐regulation and personality. In John O.P. & Robins R.W. (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (4th ed., pp. 615–616). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtz, G.M. & Donovan, J.J. (2000). Personality and job performance: The big five revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S. , Mangala, R. , Jeyagurunathan, A. , Thara, R. & Malla, A. (2011). An examination of patient‐identified goals for treatment in a first‐episode program in Chennai, India. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5, 360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, O. P. (2021). History, measurement, and conceptual elaboration of the big‐five trait taxonomy. In John O. P. & Robins R. W. (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research, (4th edn., pp. 42). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.J. & Troth, A.C. (2019). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A. , Bono, J.E. , Ilies, R. & Gerhardt, M.W. (2002a). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 765–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A. , Heller, D. & Mount, M.K. (2002b). Five‐factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov, R. , Gamez, W. , Schmidt, F. & Watson, D. (2010). Linking "big" personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta‐analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 768–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke, L. , Geukes, K. , Utesch, T. , Kuper, N. & Back, M.D. (2020). Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Research in Personality, 89, 104038. 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C. , King, R. & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11, 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, A. , Bond, G. R. , & Drake, R. E. (2014, 2014/11/01/). Does employment alter the course and outcome of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses? A systematic review of longitudinal research. Schizophrenia Research, 159, 312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, A. & Meara, E. (2014). Employment status of people with mental illness: National survey data from 2009 and 2010. Psychiatric Services, 65, 1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha, S. , Balachandra, S. & Johnson, S. (2009). Clinicians' attitudes to the employment of people with psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha, S. , Johnson, S. , Bebbington, P. , Stafford, M. , Angermeyer, M.C. , Brugha, T. et al. (2007). Rates and correlates of employment in people with schizophrenia in the UK, France and Germany. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R. & Löckenhoff, C.E. (2010). Self‐regulation and the five‐factor model of personality traits. In Hoyle R.H. (Ed.), Handbook of personality and self‐regulation (pp. 147–157). Chichester: Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R. & Terracciano, A. (2005). Personality profiles of cultures: Aggregate personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 407–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuilken, M. , Zahniser, J.H. , Novak, J. , Starks, R.D. , Olmos, A. & Bond, G.R. (2003). The work project survey: Consumer perspectives on work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 18, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Modini, M. , Joyce, S. , Mykletun, A. , Christensen, H. , Bryant, R.A. , Mitchell, P.B. et al. (2016). The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic meta‐review. Australasian Psychiatry, 24(4), 331–336. 10.1177/1039856215618523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe, C. , Brinchmann, B. , Rasmussen, L. , Brandseth, O.L. , McDaid, D. , Killackey, E. et al. (2021). Implementing individual placement and support (IPS): the experiences of employment specialists in the early implementation phase of IPS in Northern Norway. The IPSNOR study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1). 10.1186/s12888-021-03644-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen, E.Å. , Walseth, L.T. & Larsen, I.B. (2021). Experiences of participating in individual placement and support: a meta‐ethnographic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 343–352. 10.1111/scs.12848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettle, D. (2006). The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. American Psychologist, 61, 622–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, M. & Kung, M. (2007). The cost of employee turnover. Industrial Management, 49, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, C.E. , Broussard, B. , Goulding, S.M. , Cristofaro, S. , Hall, D. , Kaslow, N.J. et al. (2011). Life and treatment goals of individuals hospitalized for first‐episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 344–348. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riketta, M. (2008). The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: A meta‐analysis of panel studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, M. , Miller, L. & Perkins, R. (2010). Implementing the individual placement and support (IPS) approach for people with mental health conditions in England. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(2), 163–172. 10.3109/09540261003720456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.W. , Bogg, T. , Walton, K.E. , Chernyshenko, O.S. & Stark, S.E. (2004). A lexical investigation of the lower‐order structure of conscientiousness. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Saucier, G. & Ostendorf, F. (1999). Hierarchical subcomponents of the big five personality factors: A cross‐language replication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 613–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C.J. (2019). How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The life outcomes of personality replication project. Psychological Science, 30, 711–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C.J. & John, O.P. (2017). The next big five inventory (BFI‐2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 117–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, P. , Schmidt, J. , Bosco, F. & Uggerslev, K. (2019). The effects of personality on job satisfaction and life satisfaction: A meta‐analytic investigation accounting for bandwidth–fidelity and commensurability. Human Relations, 72, 217–247. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.C. & Bond, G.R. (2014). Employment specialist competencies as predictors of employment outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal, 50, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C. , Rogers, E.S. , Russinova, Z. & Lord, E.M. (2020). Defining employment specialist competencies: Results of a participatory research study. Community Mental Health Journal, 56, 440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P. & Meyer, J.P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta‐analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hiel, A. , Kossowska, M. & Mervielde, I. (2000). The relationship between openness to experience and political ideology. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hiel, A. & Mervielde, I. (2004). Openness to experience and boundaries in the mind: Relationships with cultural and economic conservative beliefs. Journal of Personality, 72, 659–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Saane, N. , Sluiter, J.K. , Verbeek, J.H.A.M. & Frings‐Dresen, M.H.W. (2003). Reliability and validity of instruments measuring job satisfaction – A systematic review. Occupational Medicine, 53, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukadin, M. , Schaafsma, F.G. , Michon, H.W.C. , de Maaker‐Berkhof, M. & Anema, J.R. (2021). Experiences with individual placement and support and employment – A qualitative study among clients and employment specialists. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn, G. , Saha, S. , Harvey, C. , Morgan, V.A. , Waterreus, A. , Bush, R. et al. (2012). 'Earning and learning' in those with psychotic disorders: The second Australian national survey of psychosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46, 774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott, C. , Waghorn, G. , McLean, D. , Statham, D. & Mowry, B. (2015). Interest in employment among people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 18, 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R. , Kostick, K.M. & Bush, P.W. (2010). Desirable characteristics and competencies of supported employment specialists: An empirically‐grounded framework. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 37, 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot, M.P. , Wanberg, C.R. , Kammeyer‐Mueller, J.D. & Ones, D.S. (2019). Extraversion advantages at work: A quantitative review and synthesis of the meta‐analytic evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104, 1447–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, R.D. (2008). Understanding the impact of personality traits on individuals' turnover decisions: A meta‐analytic path model. Personnel Psychology, 61, 309–348. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available due to the GDPR regulations and conditions of ethics approval.