Abstract

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is often accompanied by impaired cognitive and physical function. However, the role of cognitive function on motor control and purposeful movement is not well studied. The aim of the review was to determine the impact of cognition on physical performance in COPD. Methods: Scoping review methods were performed including searches of the databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Cochrane (CENTRAL), APA PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Two reviewers independently assessed articles for inclusion, data abstraction, and quality assessment. Results: Of 11,252 identified articles, 44 met the inclusion criteria. The review included 5743 individuals with COPD (68% male) with the forced expiratory volume in one second range of 24–69% predicted. Cognitive scores correlated with strength, balance, and hand dexterity, while 6-min walk distance (n = 9) was usually similar among COPD patients with and without cognitive impairment. In 2 reports, regression analyses showed that delayed recall and the trail making test were associated with balance and handgrip strength, respectively. Dual task studies (n = 5) reported impaired balance or gait in COPD patients compared to healthy adults. Cognitive or physical Interventions (n = 20) showed variable improvements in cognition and exercise capacity. Conclusions: Cognition in COPD appears to be more related to balance, hand, and dual task function, than exercise capacity.

Keywords: Cognition, exercise, lung disease, obstructive, dual tasking, pulmonary rehabilitation

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by airflow obstruction. 1 In 2019, COPD had an estimated global prevalence of 391 million 2 and was the third leading cause of death worldwide. 3 The clinical features of airflow limitation, lung hyperinflation, respiratory muscle weakness, and dyspnea, contribute to the exercise intolerance often present in COPD. 4 Exercise capacity as measured by the 6-min walk test (6MWT)5,6 and the level of physical activity 7 are predictors of mortality in COPD patients.

Along with the respiratory manifestations described, COPD is a systemic disease that is often accompanied by extrapulmonary sequela including cognitive dysfunction. 8 The reported prevalence of cognitive impairment in COPD patients is variable ranging between 10 to 61%, 9 and as high as 77% in hypoxemic populations. 10 Moreover, impairment ranges from mild to severe cognitive impairment and dementia, as well as deficits in both global and specific cognitive domains.11–13 Regarding specific cognitive domains, two systematic reviews both corroborate the frequent prevalence of memory and attention-related deficits in COPD.13,14

Related to diminished cognitive performance is dual tasking, an experimental paradigm used to evaluate decrements in cognition when an individual is required to perform a cognitive and motor task simultaneously. Dual task interference arises when there is reduced performance in either task relative to their single task equivalent. 15 There are several cognitive theories postulated to explain the reduced performance observed relative to single tasks. 16 One of the theories, the central capacity sharing model, posits that internal processing of the concurrent events is capacity-limited due to the requirements of parallel processing.17,18 Importantly, processing speed is correlated with broad cognitive measures, such as fluid intelligence. 19 Thus, a systematic review evaluating older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) observed greater dual task interference during walking relative to healthy controls. 20 Furthermore, individuals with MCI display worse postural, gait, and fine motor control relative to their non-MCI counterparts. 21

Given the heightened prevalence of cognitive decline in COPD, and the apparent relationship of MCI and worsened dual task performance and motor control in non-COPD, it is pertinent to evaluate how cognitive capacity influences motor control in COPD patients. Additionally, as COPD patients almost invariantly exhibit dyspnea, 22 it is critical to include dyspnea within our conceptual definition of physical performance. Indeed, dyspnea is not only a physical symptom but also an interoceptive stimuli that requires cortical and subcortical processing.23,24 In COPD, hypoxemia may lead to cognitive dysfunction through neuronal injury. 25 The aim of this scoping review was to investigate the relationship between cognitive function and motor control in COPD patients, and whether treatments improve cognitive and physical function. As cortical control is necessary for purposeful movement, 26 we hypothesize that COPD patients that exhibit cognitive impairments will have more impaired motor control compared to those without cognitive impairments.

Methods

Protocol

The draft protocol and finalized review utilize the established scoping review framework set by Arksey and O’Malley and their updated enhancements.27–29 The draft protocol was registered prospectively with Open Science Framework on 6 September 2021 (https://osf.io/ng765/). Draft revisions were conducted after consultation and feedback from the review team.

Identifying the research question

The primary objective addressed by this scoping review was to examine how cognitive capacity influences physical performance in COPD patients. The following sub-questions were addressed: 1) what is the relationship between cognitive test measures and physical performance; 2) did physical performance indicators differ when COPD patients were stratified by cognitive test scores; 3) does dual tasking influence physical performance in COPD relative to healthy adults; and 4) does baseline cognition influence cognitive and physical changes with interventions?

Information sources and search strategy

The search strategy was developed by a research librarian (AO-C) with the following key concepts: COPD, cognition, and exercise capacity. The search was executed on 20 July 2021, and a second search on 14 February 2022, in the databases: Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid Embase; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); APA PsycINFO; CINAHL complete (EBSCOhost). Conference and book materials were removed from Embase. The reference lists of retrieved publications were also examined. The searches were not limited to study design and year but were limited to humans, adults, and English language. Please see the Supplementary Appendix for the comprehensive search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

The following studies were included if they examined COPD patients of any severity: 1) by evaluating the relationship between their cognition and physical performance; 2) compared their physical performance according to stratification of their cognitive test scores; 3) examined dual task paradigms; 4) assessed cognition and physical outcomes after an intervention; and 5) evaluated the relationship between baseline cognition with physical changes with an intervention. Exclusion criteria used: 1) regression models that had cognition as an outcome variable; 2) COPD lung transplant recipients; 3) intervention studies that did not include both cognitive and physical post-treatment scores unless inclusion criterion above was met; and 4) non-English language studies. Case series, grey literature, conference proceedings and abstracts, and dissertations were excluded.

Study selection

Search results were imported into EndNote 20 and duplicates were removed using EndNote’s automation tool. Pairs of reviewers (PR, SA, EF, UM, RLFF, MK) independently screened the titles and abstracts and subsequently the selected full-text articles for inclusion. Disagreement among reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data charting process

Pairs of reviewers (PR, SA, EF, UM, RLFF, MK) independently abstracted data from the full-text articles and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Data abstraction included: study design, study location, inclusion and exclusion criteria, baseline characteristics (age, sex, number of participants, COPD severity, comorbidities), study protocol, and outcome measures (correlation coefficients, hypothesis testing outcomes, beta-coefficients, dual task results, and treatment outcomes).

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was performed using a 15-item modified Downs and Black checklist 30 or the full Downs and Black 31 checklist (27-items) 31 depending on study design, the latter was used for randomized trials, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or non-randomized controlled trials. This checklist queries study quality, external and internal validity, and power. Quality assessment was conducted by pairs of independent reviewers (PR, SA, EF, UM, MK) and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data synthesis

Baseline characteristics and cognitive and physical assessments of reports were tabulated (Table 1). Study outcomes were synthesized into three tables: cross-sectional studies that assessed the relationship between cognitive test scores and physical measure (Table 2); dual task studies (Table 3); and interventions that evaluated cognitive and physical outcomes (Table 4).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and assessments.

| Author (Year) | Study design | Sample (n) | Age | Male Female | FEV1 (% pred) | Cognitive assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation/Regression/Mean comparison studies | ||||||

| Antonelli-Incalzi (2008) | Cross-sectional | High CF COPD (48) | — | 38:10 | 38 | Raven’s progressive matrices, phonemic verbal fluency test, Corsi’s block-tapping task, auditory word span, rey auditory 15-word learning test, line cancellation test, copying drawings, immediate visual memory test, sentence construction |

| Mid CF COPD (49) | 44:5 | 36 | ||||

| Low CF COPD (52) | 44:8 | 33 | ||||

| Cleutjens (2018) | Cross-sectional | CI COPD (76) | 63 | 46:30 | 55 | Concept shifting test, letter digit substitution test, SCWT, visual verbal learning task, shortened groninger intelligence test |

| CN COPD (107) | 64 | 51:56 | 54 | |||

| Cruthirds (2021) | Cross-sectional | COPD (37) | 68 | 17:20 | 45 | TMT-B, SCWT part 3 |

| Dag (2016) | Cross-sectional | CI COPD (16) | 65 | 47:5 | 51 | MMSE |

| COPD (36) | 60 | 56 | MoCA | |||

| Gore (2021) | Cross-sectional | COPD (382) | 75 | 166:216 | Immediate word recall, delayed word recall, orientation, semantic verbal fluency test | |

| Grant (1982) | Cross-sectional | COPD (203) | 65 | 160:43 | Average impairment rating, Clinician’s global neuropsychological rating | |

| Karpman (2014) | Cross-sectional | COPD (130) | 68 | 77:53 | 50 | DSST |

| Kaygusuz (2021) | Cross-sectional | COPD (60) | 57 | 58:2 | 44 | MMSE |

| Ozyemisci-Taskiran (2015) | Retrospective cross-sectional | AECOPD (133) | 69 | 113:20 | 38 | MMSE |

| Park (2015) | Cross-sectional | COPD (593) | 67 | 382:211 | 28 | TMT |

| Park (2018) | Longitudinal; secondary analysis | COPD class 1 (109) | 67 | 64:45 | 28 | TMT part B |

| COPD class 2 (122) | 67 | 72:50 | 28 | |||

| COPD class 3 (56) | 67 | 32:24 | 29 | |||

| COPD class 4 (20) | 68 | 15:5 | 30 | |||

| Park (2020) | Cross-sectional | COPD (34) | 69 | 14:20 | 44 | Stroop interference |

| Randeep (2019) | Cross-sectional | COPD (50) | 65 | 28:22 | — | DSST, TMT, MMSE, MoCA |

| Roncero (2016) | Cross-sectional | CI COPD (570) | 70 | 463:107 | 56 | MMSE |

| CN COPD (370) | 66 | 299:71 | 55 | |||

| Schure (2016) | Cross-sectional | TMT-A: Normal (213) | 67 | 175:38 | 46 | TMT-A, TMT-B |

| Borderline (44) | 68 | 33:11 | 44 | |||

| Impaired (44) | 69 | 34:10 | 44 | |||

| TMT- B: Normal (213) | 67 | 172:41 | 46 | |||

| Borderline (38) | 69 | 33:5 | 46 | |||

| Impaired (50) | 68 | 37:13 | 42 | |||

| Soysal Tomruk (2015) | Cross-sectional | COPD (35) | 63 | 31:4 | 38 | MMSE |

| Tudorache (2017) | Cross-sectional | COPD (62) | 68 | 62:0 | 29 | MoCA |

| Yazar (2018) | Cross-sectional | CI COPD (16) | 62 | 13:3 | 3 | MMSE, CDT |

| CN COPD (75) | 62 | 73:2 | 45 | |||

| Yohannes (2021) | Cross-sectional | CI COPD (119) | 66 | 64:55 | 53 | MoCA |

| CN COPD (101) | 65 | 54:47 | 47 | |||

| Summary for cross-sectional | N = 3962 | 57-75 | 70:30% | 28-56 | — | |

| Dual task studies | ||||||

| Hassan (2020) | Cross-sectional | COPD (15) Healthy (20) |

71 69 |

9:6 9:11 |

52 93 |

Backwards spelling |

| Heraud (2018) | Cross-sectional | COPD (25) Healthy (20) |

65 70 |

— — |

48 112 |

Backwards counting by 3 |

| Morlino (2017) | Cross-sectional | COPD (40) Healthy (28) |

71 70 |

29:11 16:12 |

50 116 |

Backwards counting by 3 |

| Ozsoy (2021) | Cross-sectional | COPD (35) Healthy (27) |

62 61 |

31:4 23:4 |

59 — |

Backwards counting by 3 |

| Van Hove (2021) | Cross-sectional | COPD (21) Healthy (21) |

64 63 |

14:7 | 41 | Backwards counting by 3, verbal fluency task |

| Summary for dual task | N = 136 | 62-71 | 61:21% 18% NR |

41-59 | — | |

| Intervention studies | ||||||

| Abumossalam (2021) | RCT | Piracetam (low dose) (42) Piracetam (high dose) (44) Control (no placebo) (40) |

58 56 62 |

36:6 40:4 33:7 |

— — — |

AD8 dementia screening |

| Adrianopoulos (2021) | Pre-post; 3-weeks inpatient PR | CI COPD (25) CN COPD (35) |

68 68 |

16:9 19:16 |

46 47 |

MoCA, S-MMSE, T-ICS, ACE-R, visuospatial skills, memory, orientation, attention, language/executive, fluency |

| Aquino (2016) | Randomized trial; 4-weeks EX | CT group (14) AT group (14) |

65 69 |

14:0 14:0 |

68 69 |

Attentive matrices test, Raven’s progressive matrices, rey-immediate recall, rey-delayed recall, verbal fluency, drawing test I and II |

| Bonnevie (2020) | Pre-post; 8-weeks outpatient PR | CI COPD (41) CN COPD (15) |

64 59 |

21:20 5:10 |

36 39 |

MoCA |

| Cleutjens (2017) | Cross-sectional; PR | CI COPD (46) CN COPD (87) |

62 a | 65:68 a | 54 a | Visual verbal learning test, groninger intelligence test, letter digit substitution test 60 s, concept shifting test, SCWT card III |

| Dal Negro (2012) | Rct; 12-weeks | EAA (44) Placebo (44) |

75 73 |

32:12 29:15 |

— — |

MMSE |

| Emery (1991) | Pre-post; 1-month Outpatient PR | COPD (61) | — | 34:27 | — | TMT-A, TMT-B, digit symbol (WAIS-R), digit span (WAIS-R), finger tapping (halstead-reitan) |

| Emery (1994) | Pre-post; 1-month Outpatient PR | Older COPD (13) Mid-aged COPD (14) |

69 43 |

10:17 (total) | — - |

TMT-A, TMT-B, digit symbol (WAIS-R), digit span (WAIS-R), finger tapping (halstead-reitan) |

| Emery (1998) | Rct; 10-weeks PR | EXESM (30) ESM (24) Waiting list (25) |

65 67 67 |

15:15 10:14 12:13 |

— — — |

TMT-A, TMT-B, digit vigilance, digit symbol (WAIS-R), finger tapping (halstead-reitan), verbal fluency |

| Etnier (2001) | RCT; 15-months outpatient AT | AT (8) Control (7) |

67 70 |

5:3 6:1 |

62 68 |

Culture fair intelligence test |

| Ferrari (2004) | Pre-post; 12weeks home-based PR | COPD (28) | 70 | 20:8 | 55 | MMSE |

| France (2021) | Pre-post; 6weeks PR | COPD (67) | 67 | 37:30 | 31 | MoCA |

| Kilic (2021) | Randomized trial; 12-weeks | Home PR (31) Hospital PR (27) |

70 68 |

27:4 25:2 |

58 50 |

S-MMSE |

| Kozora (2002) | Non-RCT; 3-weeks PR | COPD PR (30) Untreated COPD (29) Con (21) |

66 67 65 |

15:15 13:16 5:16 |

40 45 — |

Digit span and digit symbol subtests (WAIS-R), digit vigilance test, TMT, logical memory, visual reproduction and paired associates subtests (WMS-R), clock drawing to command, boston naming Test-15 item, controlled oral word association test, animal naming test |

| Kozora (2005) | RCT | LVRS (19) Medical therapy (20) Con (39) |

65 64 64 |

14:5 18:2 33:6 |

25 24 — |

Digit span and arithmetic subtests (WAIS-R), logical memory, verbal paired associates, and faces subtests (WMS-R), digit vigilance test, TMT, complex ideational material subtest (boston diagnostic aphasia examination), controlled oral word association test, animal naming test, boston naming Test-15 item, CDT |

| Lavoie (2019) | RCT; 12-weeks SMBM bronchodilators EX | SMBM + T/O + EX (76) SMBM + T/O (76) SMBM + T (76) SMBM + placebo (76) |

65 65 65 64 |

45:31 48:28 55:21 53:23 |

49 50 49 47 |

MoCA |

| Liu (2021) | RCT; 12-weeks virtual PR | Virtual PR (50) Routine PR (50) |

74 75 |

40:10 38:12 |

39 40 |

MoCA |

| NOTT (1980) | RCT; minimum 12-months | 12-h nocturnal O2

(102) Continuous O2 (101) |

66 65 |

82:20 78:23 |

30 30 |

Halstead impairment index. Russell-neuringer average impairment index, brain age quotient |

| Rosenstein (2020) | Randomized trial; 12-weeks EX | CTHI (12) CTVT (12) HIIT (12) |

66 69 67 |

3:9 6:6 4:8 |

60 66 50 |

MoCA, digit span, digit symbol, and block design subtests (WAIS), TMT, SCWT, semantic verbal fluency, letter verbal fluency, RAVLT, Rey-O complex Figure (copy) |

| van Beers (2021) | RCT; 12-weeks training WM + 12-weeks Mainten | WM training (33) Sham WM training (31) |

66 66 |

13:20 16:15 |

58 61 |

Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery |

| Summary for interventional | — | 43-75 | 65:35% | 24-69 | — | |

ACE-R: Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised; AECOPD: Acute Exacerbation of COPD; AT: Aerobic Training; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; CI: cognitively impaired; CF: cognitive functioning; CN: cognitively normal; CT: Combined training (Aerobic + Resistance); CTHI: continuous training at high intensity; CTVT: continuous training at the ventilatory threshold; DSST: Digit Symbol Substitution Test; EAA: Essential Amino Acid supplementation; ESM: education and stress management; EXESM: exercise and ESM; HIIT: high-intensity interval training; LVRS: Lung Volume Reduction Surgery; Mainten: Maintenance; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mo: month; PR: Pulmonary Rehabilitation; RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; SCWT: Stroop Color and Word Test; S-MMSE: Standardized MMSE; T-ICS: Interview for Cognitive Status; SMBM + T/O + Ex: self-management behaviour modification + tiotropium/olodaterol + exercise training; TMT: Trail Making Test; TUG: Timed Up and Go; WAIS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WAIS-R: WAIS-Revised; WM: working memory; WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised.

aValues for total combined group (CI and CN COPD).

Table 2.

Cross-sectional studies showing relationships between cognitive test scores and physical performance.

| Author (Year) | Sample | Cognitive measure | Score | Physical measure | Score | Method | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrianopoulos (2021) | CI COPD | MoCA | 25 | mMRC | 1.4 (1.0) | Independent t-test | mMRC did not differ between groups (p > 0.05) |

| CN COPD | 26 | 1.6 (0.8) | |||||

| Antonelli-Incalzi (2008) | High CI | NTB | Scores adjusted for age and education | 6MWD (m) | 293 (88) | 1-Way ANOVA with scheffe post hoc test | 6MWD (m and %pred did not differ among groups (p = 0.216 and p = 0.762, respectively) |

| Mid CI | 277 (124) | VAS dyspnea did not differ among groups (p = 0.279) | |||||

| Low CI | 254 (110) | ||||||

| 6MWD % pred | 59.3 (26.0) | ||||||

| 60.0 (26.4) | |||||||

| 56.4 (23.3) | |||||||

| VAS dyspnea | 5.7 (3.1) | ||||||

| 6.0 (3.7) | |||||||

| 6.8 (3.5) | |||||||

| Bonnevie (2020) | CI COPD | MoCA | 26 | 6MWD (steps) | 148 (103–202) | Mann–Whitney U test; Independent t-test | 6MWD (steps and m) are comparable between CI and CN subgroups (p = 0.08; p = 0.39) |

| CN COPD | 26 | 191 (156–246) | |||||

| 6MWD (m) | 377 (117) | ||||||

| 409 (112) | |||||||

| Cleutjens (2018) | CI COPD | NTB | mMRC | 2.2 (1.0) | Independent t-test; Chi-squared test | mMRC and 6MWT are similar between CI and CN COPD patients (p = 0.53; p = 0.30; p = 0.14; p = 0.16 as listed respectively) | |

| CN COPD | 2.3 (1.0) | ||||||

| 6MWD (m) | 421.8 (112.2) | ||||||

| 439.2 (111.5) | |||||||

| 6MWD % pred | 66.1 (16.7) | ||||||

| 69.8 (16.4) | |||||||

| Cruthirds (2021) | COPD | SCWT pt 3 | 134.7 (6.8) | Leg extension force/kg lean mass (N/kg) | 4.9 (0.2) | Pearson’s correlation | SCWT pt 3 and TMT pt B negatively correlated with leg extension force (r = −0.3671, p < 0.05; r = −0.4563, p < 0.05) |

| TMT pt B | 80.9 (6.3) | ||||||

| Dag (2016) | CI COPD | MMSE | 24 | 6MWD (m) | 389.4 (97.5) | Independent t-test; Pearson’s correlation | 6MWD not different between groups for MMSE and MoCA scores (p = 0.15, p = 0.14) but correlated with MMSE and MoCA (r = 0.29, p = 0.037, r = 0.39, p = 0.004) |

| CN COPD | 24 | 441.5 (117.2) | |||||

| MoCA | 21 | ||||||

| 21 | |||||||

| Gore (2021) | COPD | DWR | 3.88 (1.99) | Gait speed Tandem stance time | 0.69 (0.22) | Multivariate linear regression (covariates: IWR, orientation, executive function) | Model 1: Covariates not associated with gait speed |

| 24.63 (18.5) | Model 2: DWR associated with tandem stance time ( = 1.42, 95% CI 0.10–2.74, p = 0.04) | ||||||

| Grant (1982) | COPD | AIR | 2.28 (0.78) | Maximum cycle ergometer work | Pearson’s correlation | AIR and CGNR negatively correlated with max cycle work (r = −0.18, p = 0.03; r = −0.23, p = 0.002) | |

| CGNR | 4.38 (1.12) | ||||||

| Karpman (2014) | COPD | DSST | — | 6MWD (m) | 410 (120) | Stepwise multivariate linear regression (covariates: Gait speed, DLCO%pred, FEV1%pred) | DSST weakly associated with 6MWD ( = 1.2, p = 0.011) |

| Kaygusuz (2021) | COPD (mMRC <2) | MMSE | 26.63 (2.94) | BBS | 55.20 (1.62) | Spearman’s correlation; Simple linear regression | MMSE correlated with BBS and mMRC (r = 0.331, p = 0.001; r = −0.446, p < 0.001) and associated with BBS ( = 0.314, SE = 0.099, 95% CI = 0.117–0.512, p = 0.002) |

| COPD (mMRC 2) | 25.97 (3.36) | 52.97 (4.50) | |||||

| mMRC | 0.60 (0.49) | ||||||

| 2.97 (0.76) | |||||||

| Park & larson (2015) | COPD | TMT pt A | 43.1 (16.0) | 6MWD (ft) | 1104.0 (307.7) | Pearson’s correlation | TMT pt a negatively correlated with 6MWD and peak work (r = −0.09, p = 0.024; r = −0.12, p = 0.007) and positively with ucsd-sobq (r = 0.09, p = 0.028) |

| TMT pt B | 99.9 (44.5) | Peak work (W) | 36.1 (21.0) | TMT B correlated with UCSD-SOBQ (r = 0.09, p = 0.028) | |||

| UCSD-SOBQ | 58.4 (16.6) | ||||||

| Park (2018) | Class 1 | TMT pt B | 77.0 (21.5) | 6MWD (ft) | 1265.4 (295.7) | 1-Way ANOVA with bonferroni correction | Class 1 had greater 6MWD than classes 2 and 3 (p = 0.01) |

| Class 2 | 88.3 (19.9) | 1139.5 (276.1) | No significant differences among classes for UCSD-SOBQ (p = 0.40) | ||||

| Class 3 | 130.7 (19.5) | 1123.2 (308.0) | |||||

| Class 4 | 185.9 (52.2) | 1240.5 (229.0) | |||||

| UCSD-SOBQ | 59.8 (18.5) | ||||||

| 63.0 (19.9) | |||||||

| 64.9 (19.1) | |||||||

| 60.4 (19.2) | |||||||

| Park (2020) | COPD | Stroop interference | 61.66 (3.924) | AP mean sway velocity BBS | 1.11 (0.073) | Pearson’s correlation; Multiple linear regression (covariates: O2 therapy, fat mass, diabetic status) | Stroop interference - Correlated with postural balance and negatively with BBS (r = 0.59, p = 0.0002; r = −0.45, p = 0.048) - Associated with CoP ( = 0.009796, SE = 0.0022, p = 0.0001) |

| 53.11 (0.55) | |||||||

| Ozyemisci-Taskiran (2015) | CI AECOPD | MMSE | 24 | 6MWD (m) | 146 (134) | Independent t-test; Pearson 2; Test (adjusted for age and education) | 6MWD different among unadjusted groups (p = 0.002) but not different among adjusted groups (p = 0.389) |

| CN AECOPD | 24 | 242 (152) | |||||

| Adjusted cutoff | 240 (42–360) | ||||||

| Adjusted cutoff | 252 (100.5–355) | ||||||

| Randeep (2019) | COPD | S-MMSE | 23.3 (3.3) | 6MWD (m) | 392.3 (124.856) | Pearson’s correlation | MMSE, MoCA, TMT, and DSST correlated with 6MWD (r = 0.41, p = 0.00; r = 0.30, p = 0.03; r = 0.33, p = 0.02; r = 0.34, p = 0.02) |

| MoCA | 22.2 (3.6) | ||||||

| TMT | 223 (27) | ||||||

| DSST | 28.4 (2.2) | ||||||

| Roncero (2016) | CI COPD | MMSE | 27 | mMRC | 3.1 (0.9) | Independent t-test | CI COPD had higher mMRC scores (p < 0.001) |

| CN COPD | 27 | 2.6 (0.9) | |||||

| Schure (2016) | TMT A CN | TMT A | Z-score −1.0 | mMRC | 1.8 (1.1) | One-way ANOVA; Multivariable regression (covariates: Age, sex, living arrangements, FEV % pred, home oxygen use, mMRC, hospitalization in past year, BMI, charlson comorbidity Index) | mMRC and 6 MWD differed in TMT part B subgroups (p = 0.05 and (p = 0.03, respectively) |

| TMT A CB | TMT B | 2.2 (1.1) | Grip strength differed in both TMT a and TMT B subgroups (p = 0.002; p = 0.02); Borderline impaired TMT A showed significant association with grip strength ( = -2.9, 95% CI -5.5, −0.4, p < 0.05). Borderline and impaired TMT B showed significant association with grip strength ( = -3.0, 95% CI -5.7, −0.3, p < 0.05; = -2.5 95% CI -2.5, −0.0, p < 0.01, respectively) | ||||

| TMT A CI | Z-score −1.0 to −1.5 | 2.1 (1.2) | |||||

| TMT B CN | 1.8 (1.1) | ||||||

| TMT B CB | Z-score −1.5 | 2.0 (1.1) | |||||

| TMT B CI | 2.2 (1.2) | ||||||

| 6MWD (ft) | 1122 (375) | ||||||

| 1025 (328) | |||||||

| 976 (377) | |||||||

| 1113.3 (361.2) | |||||||

| 1065.4 (346.9) | |||||||

| 987.7 (421.1) | |||||||

| Grip strength (kg) | 33.6 (9.4) | ||||||

| 29.1 (8.9) | |||||||

| 29.4 (9.8) | |||||||

| 33.3 (9.8) | |||||||

| 30.2 (7.6) | |||||||

| 29.6 (9.2) | |||||||

| Soysal Tomruk (2015) | Hypoxemic COPD | MMSE | 23.9 (3.3) | Placement dexterity (min) | 2.1 (0.3) | Pearson’s correlation | MMSE negatively correlated with placement and turning dexterity (r = −0.411, p = 0.0015; r = 0.418, p = 0.013) |

| Turning dexterity (min) | 2.3 (0.3) | ||||||

| Tudorache (2017) | COPD | MoCA | 21.50 (20–24) | 6MWD (m) | 360 (315–400) | Spearman’s Correlation | MoCA not correlated with 6MWD (r = 0.131, NS) |

| Yazar (2018) | CI COPD | MMSE | 24 | 6MWD (m) | 285.94 (136.921) | Independent t-test; Pearson’s correlation | 6MWD different between groups (p = 0.018) but mMRC similar |

| CN COPD | 24 | 358.89 (103.696) | 6MWD correlated with MMSE and CDT (r = 0.294, p = 0.005; r = 0.258, p = 0.014) but not mMRC | ||||

| COPD | CDT | 4.14 (1.3) | MMRC | 2.06 (1.526) | |||

| 1.53 (1.057) | |||||||

| Yohannes (2021) | CI COPD | MoCA | [18,26) | 6MWD | 1134 (842, 1356) | Independent t-test | 6MWD and mMRC did not significantly differ among subgroups (p = 0.102; p = 0.392, respectively) |

| CN COPD | 26 | 1198 (983, 1420) | |||||

| mMRC | mMRC | 3 (2, 4) | |||||

| 3 (1, 4) |

6MWD: 6-min walk distance; AIR: average impairment rating; AP: anteroposterior; BBS: berg balance scale; CGNR: clinician’s global neuropsychologic Rating; CoP: center of pressure; DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; DWR: delayed word recall; IWR: immediate word recall; mMRC: modified medical research council dyspnea scale; NS: non-significant; NTB: neuropsychological testing battery; UCSD-SOBQ: The University of California, San Diego shortness of breath questionnaire; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Table 3.

Dual task studies—performance of COPD patients relative to healthy controls (Con).

| Author (Year) | Cognitive screening (COPD vs control) | Motor task | Single task | Between group p-value | Dual task | Between group p-value | Main outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hassan (2020) | MoCA | PPW velocity | Lower | 0.005 | Lower | 0.025 | COPD exhibited decreased gait velocity in both single and dual tasks (+ backwards spelling) compared to Con |

| 24.2 vs 26.1 | FPW velocity | Lower | 0.001 | Lower | 0.035 | ||

| p = 0.032 | |||||||

| Heraud (2018) | No screening | Gait speed | Lower | NS | Lower | NS | COPD patients exhibit increased stride time variability during dual task (+ counting backwards by 3) compared to Con |

| Stride time variability | Lower | NS | Higher | <0.001 | |||

| Morlino (2017) | MMSE | TUG test | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | COPD patients exhibit longer TUG test time for single and dual tasks (+ counting backwards by 3) compared to Con |

| 26.7 vs 28.3 | |||||||

| p < 0.025 | |||||||

| Ozsoy (2020) | No screening | TUG test | Higher | NS | Higher | NS | COPD did not differ in the TUG test and knee extension muscle force production in single and dual tasks (+ counting backwards by 3) compared to Con |

| Knee extensor force | Lower | NS | Lower | NS | |||

| Van hove (2021) a | No screening | DOT | Higher | NS | Higher b | <0.05 | COPD patients exhibit greater balance-related deficits single and dual tasks (+ counting backwards by 3 or verbal fluency task) compared to Con |

| Higher c | <0.05 | ||||||

| Area | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | <0.05 | ||||||

| ML RoM | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | NS | ||||||

| AP RoM | Higher | NS | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | NS | ||||||

| ML SD | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | NS | |||

| Higher | NS | ||||||

| AP SD | Higher | NS | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | NS | No correlation was found between cognitive function (verbal fluency or backwards counting) and postural control | |||||

| ML speed | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | <0.05 | ||||||

| AP speed | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | <0.05 | ||||||

| TMV | Higher | <0.05 | Higher | <0.05 | |||

| Higher | <0.05 |

Area: area of the 95% prediction ellipse; healthy controls: Con; DOT: total displacement of sway; ML: medial-lateral; RoM: Range of motion; PPW: preferred paced walk; FPW: fast paced walk; SD: CoP standard deviation; TMV: trajectory mean velocity; TUG: timed-up-and-go test.

aResults from eyes closed condition only shown.

bResults for counting backwards dual task condition.

cResults for verbal fluency dual task condition.

Table 4.

Interventions showing within subject changes in cognition and physical performance.

| Author (Year) | Sample | Cognitive measure | Result (Δ mean (SD)) | Pre-post p-value | Physical measure | Result | Pre-post p-value | NS measures a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | ||||||||

| Andrianopoulos (2021) | CI COPD | S-MMSE | 0.7 (1.1) | <0.05 | 6MWD (m) | 25 (59) | <0.05 | Cognitive measures: Orientation, attention |

| CN COPD | 0.5 (1.2) | <0.05 | 46 (48) | <0.05 | ||||

| T-ICS | 1.1 (1.9) | <0.05 | 6MWD%pred | 3.6 (9.3) | NS | |||

| 1.1 (1.7) | <0.05 | 7.1 (7.3) | <0.05 | |||||

| ACE-R | 4.4 (4.6) | <0.05 | CET 75%WRpeak (s) | 140 (142) | <0.05 | |||

| 1.8 (2.9) | <0.05 | 117 (166) | <0.05 | |||||

| Visuospatial skills | 7.5 (14.4) | <0.05 | ||||||

| 0.4 (12.9) | NS | |||||||

| Memory | 6.0 (9.3) | <0.05 | ||||||

| 4.2 (5.8) | <0.05 | |||||||

| Language/executive | 2.1 (5.9) | NS | ||||||

| 1.9 (3.4) | <0.05 | |||||||

| Fluency | 8.3 (16.0) | <0.05 | ||||||

| 0.9 (9.5) | NS | |||||||

| Bonnevie (2020) | CI COPD | MoCA | 1.0 | <0.01 | 6MST | 34 | <0.01 | |

| CN COPD | 0.37 | 27 | 0.03 | |||||

| 6MWD (m) | 28 | 0.10 | ||||||

| 34 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Cleutjens (2017) | CI COPD | 6MWD (m) | 21.7 (47.2) | 0.003 | ||||

| CN COPD | 15.7 (57.8) | 0.013 | ||||||

| mMRC | −0.6 (1.3) | 0.013 | ||||||

| −0.4 (0.9) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Emery (1991) and Emery (1994) b | Male/Female | TMT part A | −2.17/-4.02 | NS | VO2max (ml/min) | 140.7/67.1 | <0.001 | Cognitive measures: Digit span forward, digit span backward, tapping non-dominant hand |

| Middle/Old | −6.76/-8.06 | <0.05 | 212.9/65.54 | NS | ||||

| TMT part B | −33.9/-40.4 | <0.001 | Power (W) | 11.7/8.54 | <0.001 | |||

| −39.1/-55.2 | <0.05 | 20.2/7.32 | <0.05/NS | |||||

| Digit symbol | 5.62/6.61 | <0.001 | Laps (in 12 min) | 2.05/2.43 | <0.05 | |||

| 11.19/6.82 | <0.05/<0.01 | 3.71/1.36 | <0.001/<0.05 | |||||

| Tapping dominant hand | 2.05/3.61 | <0.05 | ||||||

| 4.98/3.1 | NS | |||||||

| Emery (1998) | EXESM | Verbal fluency | 5.3 | <0.001 | Work (kp-m) | 11.3 | <0.01 | Cognitive measures: Digit vigilance, tapping dominant hand, tapping non-dominant hand, TMT part A, TMT part B, digit symbol |

| ESM | −0.2 | NS | 1.8 | NS | ||||

| WL | 0.4 | NS | −1.0 | NS | ||||

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 2.0 | <0.01 | ||||||

| −3.0 | NS | |||||||

| −0.3 | NS | |||||||

| Ferrari (2004) | Home PR | MMSE | Max work (W) VO2max |

↑ ↑ |

<0.05 <0.05 |

|||

| France (2021) | COPD | MoCA | 0.6 (2.8) | NS | SPPB | ↑ | <0.001 | |

| CI COPD | 1.6 (2.4) | 0.004 | ||||||

| CN COPD | −0.8 (2.) | 0.276 | ||||||

| Kilic (2021) | Home PR | S-MMSE | 0.48 | 0.001 | 6MWD (m) | 14.48 | 0.005 | |

| Hospital PR | 0.77 | 0.001 | 68.22 | <0.001 | ||||

| Kozora (2002) | PR COPD | Digit vigilance | −31.3 | CI 0.004 | 6MWD (ft) | 266 | <0.001 | Digit span, digit symbol, TMT part B, visual retention, verbal pairs, BNT-SF, letter fluency, semantic fluency |

| COPD-no PR | −17.6 | NS | 43 | <0.001 | ||||

| Con | −30.7 | NS | ||||||

| Story retention | 11.1 | CI 0.006 | ||||||

| 10.0 | NS | |||||||

| 9.0 | NS | |||||||

| Clock score | 0.4 | CI 0.06 | ||||||

| −0.4 | NS | |||||||

| 0.4 | NS | |||||||

| Liu (2021) | Virtual PR Control | MoCA | ↑ ↔ |

<0.05 | 6MWD (m) | ↑ ↑ |

||

| Aerobic and resistance training | ||||||||

| Aquino (2016) | CT | Attentive matrices | 2.43 | <0.01 | VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 4.78 | Cognitive measures: Rey-IR, drawing test I | |

| AT | 3.15 | <0.01 | 5.01 | |||||

| Rey-DR | 1.35 | <0.01 | 11.72 | |||||

| 0.64 | <0.05 | Quadricep strength kg | 11.07 | |||||

| Raven test | 1.72 | <0.01 | 4.43 | |||||

| 0.64 | <0.05 | 2.85 | ||||||

| Verbal fluency | 5.0 | <0.01 | Arms strength kg | |||||

| 4.0 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Drawing test II | 5.71 | <0.01 | ||||||

| 3.21 | <0.05 | |||||||

| Etnier (2001) 3-months exercise phase |

COPD | CFIT | 4.93 | <0.001 | 6MWD (ft) | 207 | <0.001 | — |

| VO2max | 0.94 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Maintenance phase(3–18 months) | (mL/kg/min) | |||||||

| Long term exercise | CFIT | 2.5 | NS | 6MWD (ft) | 40.38 | NS | ||

| No exercise | −0.14 | NS | −75.85 | NS | ||||

| VO2max | −0.84 | <0.01 | ||||||

| (mL/kg/min) | −1.75 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Rosenstein (2020) | ||||||||

| 12-weeks intervention phase | CTHI | WAIS digit span | 2.4 | 0.830 c | Endurance time (s) | 30.92 | <0.001 | Medium to small effect sizes during intervention phase: TMT part A, TMT part B, SCWT, semantic and letter verbal fluency, RAVLT (total 1–5), RAVLT (list B), RAVLT (immediate recall), RAVLT (delayed recall), WAIS block design, WAIS digit symbol coding |

| CTVT | −1.0 | −0.310 | 33.26 | <0.001 | ||||

| HIIT | 1.5 | 0.423 | 36.28 | <0.001 | ||||

| Rey-O complex Figure (copy) | 2.0 | 0.963 | ||||||

| 2.9 | 0.659 | |||||||

| 0 | 0.015 | |||||||

| Maintenance phase (week 12 to year 1) | CTHI | 1.7 | 0.932 | |||||

| CTVT | MoCA | −0.3 | - | |||||

| HIIT | 1.1 | - | ||||||

| −0.04 | 0.111 | |||||||

| SCWT (part 4-3) | −0.58 | −0.391 | ||||||

| 0.49 | 0.849 | |||||||

| Working memory (WM) training | ||||||||

| van Beers (2021) | Cognitive measures: Motor orientation task, paired associates learning, stop-signal task, delayed match-to-sample, spatial working memory Physical measures: 6MWD, accelerometry activity count | |||||||

| 12-weeks intervention phase | WM training | |||||||

| Sham training | ||||||||

| 12-weeks maintenance phase | ||||||||

| WM training | 5-Choice movement time (RTI) | ↓ | 0.016 | |||||

| Sham training | ↔ | 0.303 | ||||||

6MST: 6-min stepper test; BNT-SF: Boston Naming Test-Short Form; CET: cycle-endurance test; CFIT: Culture Fair Intelligence Test; DR: delayed recall; ESWT: endurance shuttle walk test; IR: immediate recall; MT: medical therapy; PEmax: maximal expiratory pressure; PImax: maximal inspiratory pressure; RTI: Reaction Time Task; SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery; SNIP: sniff nasal inspiratory pressure; WL: waiting list. Some of the abbreviations are shown for Table 1.

aData from the same study.

bEffect sizes reported instead of p-values.

cNon-significant pre-to-post measures for all study groups.

Results

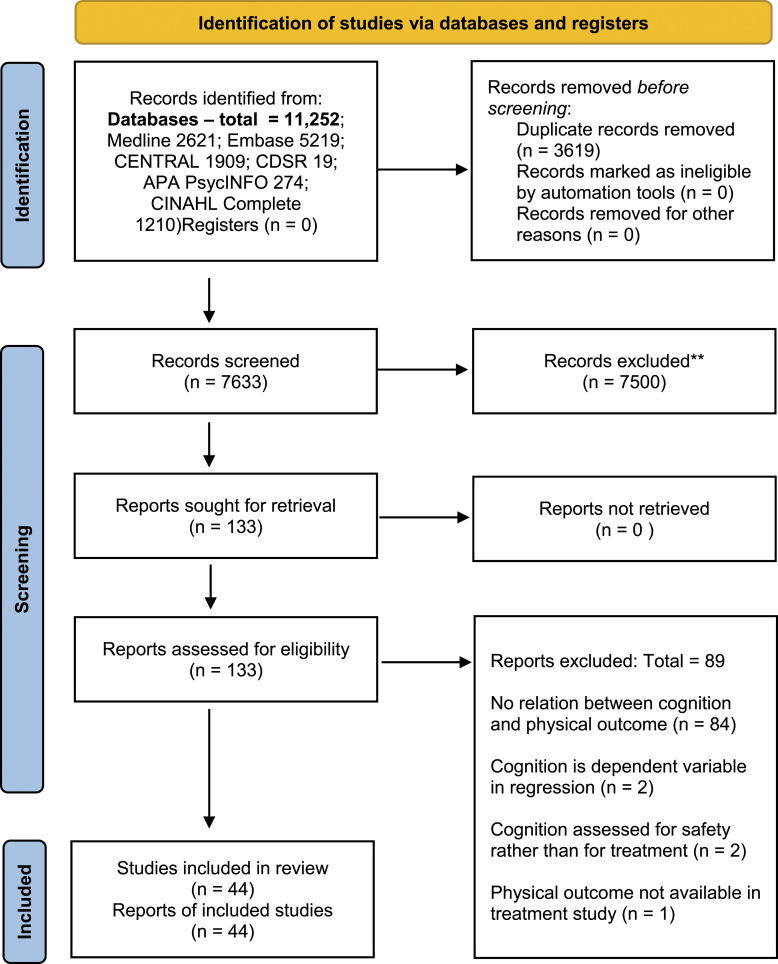

The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the screening results. 32 The initial and second searches yielded 10,045 and 1207 articles, respectively. The number of duplicates removed was 3619. Screening resulted in 133 full-text articles to be screened for eligibility and 44 articles met the inclusion criteria.10,33–75 Studies were excluded due to lack of a relationship between cognition and physical outcomes (n = 84); regression models utilizing cognition as an outcome rather than an explanatory variable (n = 2); drug intervention studies that evaluated pre- and post-cognitive outcomes to assess safety (n = 2); and a study that evaluated cognitive but not physical outcomes after rehabilitation.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram summarizing search strategy results.

Of the 31 studies evaluated using the modified Downs and Black checklist (see Supplementary Appendix), quality assessment scores ranged from 43.8% to 87.5%, with a mean of 65.5%. All 31 studies scored points for: stating the study hypothesis or study aim(s); clearly delineating study outcomes; clearly describing the main findings; using appropriate statistical tests; and using valid and reliable study measures. Studies demonstrated poor external validity and internal validity (confounding) with a combined mean percentage of 14.6% and 32.3%, respectively. The 31 studies had a mean score of 74.2% for internal validity (bias), with no studies receiving points for blinding outcome measures.

Of the 13 studies evaluated using the full Downs and Black checklist, quality assessment scores ranged from 46.4% to 89.3%, with a mean of 60.7%. These studies scored high for internal validity (bias) with a mean of 83.5%. The studies demonstrated poor external validity with a mean of 12.8%. Only two of the 13 studies demonstrated sufficient statistical power.

Baseline characteristics of study participants and cognitive assessment used are summarized in Table 1. Regarding the type of cognitive assessment used in the cross-sectional and longitudinal (non-intervention) studies, three studies used a comprehensive neuropsychological testing battery, seven studies used the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), four studies used the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, and nine studies used a combination of the Stroop Test, Trail Making Test (TMT), Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), clock-drawing test (CDT), a verbal fluency test, and word recall. For the dual task studies, one applied backwards spelling, four used backwards subtraction by threes, and one of these four also applied a verbal fluency task. Among the intervention studies, 10 utilized neuropsychological testing batteries, nine utilized either the MoCA or MMSE, one used the Culture Fair Intelligence Test, and one used the AD8 dementia screening tool.

The relationship between cognitive test scores and physical performance are summarized in Table 2.

Cognition and exercise capacity

Inconsistent findings were reported for the relationship between 6MWD and stratification of subgroups using cognitive screening tools (MoCA or MMSE) or a comprehensive neuropsychological testing battery. Observational studies did not identify a difference in 6MWD in cognitively impaired (CI) and cognitively normal (CN) subgroups.38,42,75 Two cross-sectional studies62,74 identified a difference in 6MWD between CI and CN subgroups when stratified by the MMSE, with the CI group having a lower mean 6MWD. However, this relationship was negated in one report after adjusting for age and education. 62 Of note, cross-sectional studies identified significant weak-to-moderate correlations between cognitive screening tools and 6MWD,42,66,74 while another study did not find an association between the MoCA and 6MWD. 71 When using a comprehensive neuropsychological testing battery, cross-sectional studies did not identify a difference in 6MWD between CI and CN individuals.36,40

Other cognitive tests used to evaluate relationships with 6MWD also showed mixed results. A longitudinal study organized patients into low or high baseline TMT part B (higher scores indicate greater impairment for TMT A and B) scores (measure of executive function) and reported varying improvements in their cognitive test scores over 3 years, with those improving having higher baseline 6MWD. 64 A cross-sectional study found differences in 6MWD when stratifying COPD patients by TMT part A scores (measure of psychomotor speed) but not according to TMT part B scores; COPD patients with impaired TMT part A had lower 6MWD than patients categorized with a normal TMT part A score. 69 Moreover, TMT part A but not TMT part B was found to have a weak inverse correlation with 6MWD. 65 Another cross-sectional study found a weak correlation between TMT and 6MWD. 66 Two cross-sectional studies found the DSST, a measure of psychomotor speed, to be weakly associated 53 and weakly correlated with 6MWD. 66 The CDT, a measure of memory, attention, and visuospatial abilities had a weak correlation with 6MWD. 74

Regarding gait speed, in a cross-sectional study using multivariate linear regression, all covariates, which included delayed word recall, immediate word recall, measurement of orientation or executive function, were not significant. 50

Regarding cycle ergometry, Average Impairment Rating, a global index of impairment (higher score indicates greater CI), and an independent global rating by clinicians, demonstrated a weak negative correlation with maximum work. 10 TMT part A was also reported to have a weak negative correlation with maximum work, while the relationship with TMT part B was not significant. 65

The Stroop-Color Word Test (SCWT), a measure of executive function and cognitive flexibility, and TMT part B, were both found to have a moderate inverse correlation with leg extension force. 41

Cognition and dyspnea

Categorizing COPD patients into CI and CN subgroups according to cognitive test scores had mixed results regarding Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea scores. Higher mMRC Dyspnea scores were found in CI COPD when stratifying by MMSE 67 and TMT part B, 69 while MoCA,35,75 a comprehensive neuropsychological testing battery, 40 and TMT part A69 stratification showed no significant differences.

Regarding other measures of dyspnea, categorizing subgroups based on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, one cross-sectional study did not identify a difference in their Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) dyspnea scores. 36 Categorizing patients into high or low TMT part B baseline scores with varying trajectories of cognitive improvement, did not find a significant difference between their University of California, San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD-SOBQ) scores 64 ; with TMT part B being weakly correlated with the UCSD-SOBQ, while TMT part A was not. 65

Cognition and balance

An investigation of postural and functional balance through center-of-pressure displacement and Berg Balance Scale (BBS), respectively, found moderate correlations with Stroop interference. 63 Multiple linear regression modelling showed associations with Stroop interference score and center-of-pressure, adjusted for other covariates (see Table 2). 63 In a younger COPD cohort (mean of 57 years), the MMSE was weakly correlated with BBS, and MMSE was associated with BBS through simple linear regression. 54 Moreover, another cross-sectional study using multivariate linear regression, found an association between delayed word recall and tandem stance time. 50

Cognition and hand function

In COPD patients categorized by TMT part A and TMT part B scores, grip strength was significantly higher in CN individuals. 69 Additionally, through multivariable regression, borderline impaired TMT part A scores and borderline impaired and impaired TMT part B scores were independently associated with decreased grip strength (Table 2). 69 Along with handgrip strength, cognition measured through MMSE had a moderate negative correlation with placement and turning dexterity in a hypoxemic cohort, with the dexterity correlation not being different in those with mild and moderate hypoxemia. 70

Dual tasking in COPD patients compared to healthy controls

In one study, COPD patients exhibited decreased walking velocity during both single and dual task (walking and backwards spelling) conditions compared to healthy controls, 51 while another study did not report differences in gait speed in both task conditions, but did find greater stride time variability for COPD patients during dual tasking (walking and backwards counting by 3). 52 Mixed results were also found for the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, whereby one study reported COPD patients having a longer TUG completion time in both single and dual tasks relative to healthy controls, 60 while the other did not report a difference in single and dual task conditions for the TUG test and knee extension muscle force. 61 Both studies utilized backwards counting as their cognitive task paradigm.60,61 Regarding balance assessed through CoP displacement during dual tasking, COPD patients exhibited greater balance deficits in both single and dual tasks relative to healthy controls. 73

Effects of interventions on cognitive outcomes in COPD patients

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) resulted in variable improvements among the studies assessing specific cognitive domains.35,44–46,57 PR showed improvements in global cognition,35,38,49,55,59 attention and processing speed,44,45,57 executive function,35,44–46 visuospatial skills,35,57 and language ability. 57 Among the five PR studies showing improvements in global cognition,35,38,49,55,59 two studies demonstrated improvements only in CI COPD patients.38,49 All PR interventions resulted in significant improvements in physical outcomes,35,38,39,44–46,48,49,55,57,59 with three studies35,38,39 reporting no difference in 6MWD post-rehabilitation between CI and CN COPD patients, while investigation 38 reported CN COPD patients having significantly greater post-rehabilitation 6-min stepper test (6MST) scores than CI COPD patients. Studies evaluating whether cognition is associated with PR physical improvements showed mixed results.38,48 Improvements in MoCA scores were not associated with changes in exercise capacity as measured by 6MWD and 6MST in hospital-based PR, 38 while baseline MMSE scores were significantly correlated with improvements in maximum cycling effort (watts) (r = 0.46, p < 0.05) and VO2max (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) in home-based PR. 48

Exercise interventions had variable cognitive outcomes.37,47,68 Endurance training was shown to improve fluid intelligence,37,47 global cognition, 68 visuospatial abilities,37,68 working memory, 68 attention, 37 delayed recall, 37 and executive function. 37 Combined aerobic and resistance training resulted in greater improvements in delayed recall, fluid intelligence, and visuospatial abilities compared to aerobic training alone. 37

Working memory (WM) training versus sham WM training was also studied. 72 WM refers to the short-term memory that is required to do things in the moment. Although WM span increased over 24 weeks in the intervention group, this was not reflected in improvements in cognitive test scores. 72 Moreover, physical capacity as measured by 6MWT and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) showed no improvements. 72

Other interventions such as behavioral modification, 58 lung volume reduction surgery, 56 oxygen (O2) therapy, 33 amino acid 43 and piracetam supplementation 34 resulted in cognitive improvements. Moreover, all these therapies also improved physical outcomes except O2 supplementation.33,34,43,56,58

Discussion

COPD, 6MWD, and balance

Our findings indicate that CI and CN COPD patients have comparable 6MWT scores,36,38,42,75 with studies finding no association between cognitive impairment and 6MWD.40,62 These findings are corroborated by the low-order correlation between global42,74 and domain-specific65,74 cognitive test scores and 6MWD. Similarly, dyspnea scores were comparable between CI and CN COPD patients,35,36,40,64,74,75 with low, 65 moderate, 54 and non-significant correlations found. 74 Importantly, lower cognitive test scores were associated with impairments in balance parameters.50,54,63

Of clinical importance, a recent meta-analysis found that COPD patients had greater deficits in their balance compared to healthy controls. 76 Nonetheless, while shorter 6MWDs are correlated with impairments in balance function,77–79 and a 6MWD <300 m being a predictor for balance impairments as measured by the BBS and TUG, 80 the reviewed studies indicate no difference in 6MWDs between CI and CN COPD patients. Given the importance of balance in daily activities, further exploration of interventions to improve the relationship between CI and falls are required.

Potential mechanisms underlying cognitive-physical relationship

As depicted from the results, COPD patients who display decreased cognitive capacity are more likely to exhibit impairments in balance and hand function, rather than functional exercise capacity or physical conditioning as measured by the 6MWT. Our results do not reflect a lack of relationship with 6MWD, but that the relationship with cognition and 6MWD is less pronounced. One plausible mechanism is the increased cortical sensorimotor connectivity demonstrated while standing versus walking. 81 This heightened cortical connectivity suggests greater attention is needed for balance and postural control, while walking may depend more on spinal neural networks. 81 COPD patients exhibit reduced white matter integrity and impairments in gray matter functional connectivity 82 ; thus, CI COPD patients may lack the cortical resources to sustain adequate balance.

A regression model investigating cognitive-balance relationships demonstrated an association between better delayed word recall and increased tandem stance time. 50 The 10-word list used for delayed recall is often utilized to detect mild CI by assessing hippocampal and entorhinal cortical functions. 83 Poor delayed recall is associated with hippocampal84,85 and entorhinal atrophy.86,87 Importantly, hippocampal atrophy and its association with CI has been reported in COPD. 88 The hippocampus and entorhinal cortex receive input from the vestibular system. 89 Notably, hippocampal and entorhinal atrophy is associated with impaired vestibular function, a system important for maintaining balance. 90

Additionally, another regression model depicted poorer TMT scores (worse executive function) associated with weaker handgrip strength. 69 The prefrontal cortex (PFC) facilitates executive function, 91 and PFC impairments can lead to worse motor planning and recruitment, and thereby reduced strength.92,93

Dual tasking

Similarly, cognitive-motor dual tasking induced static balance deficits in COPD patients. 73 Balance 76 and postural control94,95 are often impaired in COPD. While several factors have been implicated in balance impairments, such as age,96,97 dyspnea, 98 inspiratory muscle weakness, 99 and lower limb muscle strength, 98 the influence of cognition has not been investigated as thoroughly. Although, a cognitive screening test was not conducted in the dual task study by Van Hove et al., 73 COPD patients had lower verbal fluency task scores than healthy controls.

Impairments when performing a concurrent task may arise due to processing constraints within the brain, such as the PFC. In a single-cell recording study in monkeys, dual tasking resulted in concurrent activation of the same lateral PFC region suggesting cognitive capacity limitations. 100 Related to limitations in capacity, Hassan et al. 51 observed that COPD patients did not increase dorsolateral PFC oxygenated hemoglobin (O2Hb) from single to dual tasks, while healthy individuals did increase O2Hb. Therefore, this observed ceiling effect in neural activity may be pivotal to the constraints in simultaneous processing. In addition to limited cognitive capacity, impairment has been reflected by reduced PFC automaticity (decrease in O2Hb seen in tasks requiring less executive function) during single and dual task walking in COPD and older adults, respectively.101,102

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

In this review, the predominant intervention to facilitate cognitive-physical improvements was PR. All PR studies found significant improvements in cognition. However, of the four studies35,38,49,57 assessing differences in PR outcomes between CI and CN COPD patients, three38,49,57 found cognitive improvements only in CI COPD patients. Thus, the efficacy of PR cognitive improvement may also, among other factors, rely on baseline cognition.

Notably, the physical improvements that arise from PR seem to be independent from baseline cognition, as all studies specifically evaluating PR in CI COPD patients note an improvement in physical performance.35,38,39,49 Although, Ferrari et al. 48 did find a moderate correlation between baseline MMSE scores and improvements in exercise capacity in a minimally supervised home PR setting. While compliance was assessed, potential CI may have influenced proper completion of the training sessions in a minimally supervised setting, hence the moderate correlation between MMSE scores and exercise capacity. Furthermore, Cleutjens et al. 39 found that CI COPD patients had an increased rate of PR dropout compared to CN COPD patients.

Nonetheless, despite the potential risk for PR dropouts, physical improvements were observed in CI COPD, with the 6MWT being the most frequent treatment outcome. While this scoping review identified balance as a potential factor that is impaired in CI COPD patients, most PR studies included in our review did not conduct balance assessments. Of interest, a report that examined physical outcomes but not cognition before and after PR in COPD patients, found that the small improvement in BBS were not related to improvements of 6MWD. 103 Thus, including balance outcomes, along with usual exercise capacity measures, may be warranted, especially in CI COPD patients.

Aerobic and resistance training

An interesting finding regarding exercise is the enhanced cognitive benefits found in combining aerobic and resistance training versus aerobic training alone in COPD patients. 37 This approach is corroborated by studies of those with stroke 104 and dementia, 105 as well as a meta-analysis of healthy individuals that showed a larger effect size of combined aerobic-resistance training than aerobic training alone. 106

Working memory training

Cognitive training, specifically WM training, has been recently investigated in COPD patients. While van Beers et al. 72 found an improvement in WM trained task, the improvements did not generalize to overall cognitive improvements as measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. Additionally, secondary outcomes measuring exercise capacity showed no improvements. A previous study investigating cognitive training in hypoxemic COPD also found no cognitive improvements relative to the control group (no cognitive training). 107 A review investigating cognitive training also affirms that, while cognitive training can improve the specific trained task, there may be a lack of generalizability. 108

Limitations

There are some limitations in this scoping review. To develop a broader descriptive scope of the differences between CI and CN COPD patients, results from independent t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and correlation coefficients were included. While these results help characterize the relationship between cognition and physical performance, they cannot delineate the underlying mechanisms. Secondly, there was a large degree of heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes that prevented a meta-analysis of the interventions. Moreover, the low statistical power in many of these interventions precludes conclusions of actual treatment effects. Regarding dual task studies, the comparator groups were healthy individuals rather than CN COPD patients, thus the impact CI has on dual tasking cannot be stated. Importantly, most of the data was collected from cross-sectional studies, thus determining the causality between cognition and physical performance is not possible.

Conclusions and future directions

Limited cognitive capacity in COPD was more likely to be associated with impairments in balance, hand function, and dual tasking rather than exercise capacity. Due to the inherent limitations in study design and statistical analysis, causal mechanisms cannot be determined. Pulmonary rehabilitation was the most common treatment, which resulted in variable cognitive improvements. Given the increased incidence of falls in COPD, 109 and the possible relationship between cognitive impairment and balance deficits, future interventions may incorporate balance assessment in COPD patients that present with cognitive decline and impairment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Impact of cognitive capacity on physical performance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A scoping review by Peter Rassam, Eli M. Pazzianotto-Forti, Umi Matsumura, Ani Orchanian-Cheff, Saina Aliabadi, Manjiri Kulkarni, Rachel L. Fat Fur, Antenor Rodrigues, Daniel Langer, Dmitry Rozenberg and W Darlene Reid in Chronic Respiratory Disease

Authors’ contributions: PR, DR and WDR conceived and designed the study. AO-C performed the data base searches. PR, EF, UM, SA, MK, RLFF screened eligibility of titles and abstracts and PR, EF, UM, SA, MK screened for full text exclusion and abstracted data including the quality assessment for the included articles. PR wrote the initial manuscript and WDR contributed to the writing of the manuscript. PR revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed funding support from the RAMP Trust fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PCS 183427), Canadian Institute of Health Research Operating Grant (PJM 179846). Dmitry Rozenberg receives research support from the Sandra Faire and Ivan Fecan Professorship in Rehabilitation Medicine.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Peter Rassam https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2902-7955

Eli Maria Pazzianotto-Forti https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0989-1092

Ani Orchanian-Cheff https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-2692

Daniel Langer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8738-9482

Dmitry Rozenberg https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8786-9152

W Darlene Reid https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9980-8699

References

- 1.Szalontai K, Gemes N, Furak J, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: epidemiology, biomarkers, and paving the way to lung cancer. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 2889. DOI: 10.3390/jcm10132889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 447–458. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death, 2020.

- 4.Laveneziana P, Guenette JA, Webb KA, et al. New physiological insights into dyspnea and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Expert Rev Respir Med 2012; 6: 651–662. DOI: 10.1586/ers.12.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanova C, Cote C, Marin JM, et al. Distance and oxygen desaturation during the 6-min walk test as predictors of long-term mortality in patients with COPD. Chest 2008; 134: 746–752. DOI: 10.1378/chest.08-0520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cote CG, Pinto-Plata V, Kasprzyk K, et al. The 6-min walk distance, peak oxygen uptake, and mortality in COPD. Chest 2007; 132: 1778–1785. DOI: 10.1378/chest.07-2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waschki B, Kirsten A, Holz O, et al. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest 2011; 140: 331–342. DOI: 10.1378/chest.10-2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleutjens FAHM, Janssen DJA, Ponds RWHM, et al. COgnitive-pulmonary disease. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014(697825): 697825. DOI: 10.1155/2014/697825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrianopoulos V, Gloeckl R, Vogiatzis I, et al. Cognitive impairment in COPD: should cognitive evaluation be part of respiratory assessment? Breathe (Sheff) 2017; 13: e1–e9. DOI: 10.1183/20734735.001417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant I, Heaton RK, McSweeny AJ, et al. Neuropsychologic findings in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 1982; 142: 1470–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleutjens FA, Franssen FM, Spruit MA, et al. Domain-specific cognitive impairment in patients with COPD and control subjects. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017; 12: 1–11. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S119633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd JW. Lung disease as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015; 7(32): 32. DOI: 10.1186/s13195-015-0116-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schou L, Ostergaard B, Rasmussen LS, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–a systematic review. Respir Med 2012; 106: 1071–1081. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres-Sanchez I, Rodriguez-Alzueta E, Cabrera-Martos I, et al. Cognitive impairment in COPD: a systematic review. J Bras Pneumol 2015; 41: 182–190. DOI: 10.1590/S1806-37132015000004424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leone C, Feys P, Moumdjian L, et al. Cognitive-motor dual-task interference: a systematic review of neural correlates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 75: 348–360. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pashler H. Dual-task interference in simple tasks: data and theory. Psychol Bull 1994; 116: 220–244. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tombu M, Jolicoeur P. Testing the predictions of the central capacity sharing model. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 2005; 31: 790–802. DOI: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.4.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tombu M, Jolicoeur P. A central capacity sharing model of dual-task performance. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 2003; 29: 3–18. DOI: 10.1037//0096-1523.29.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimprich D, Martin M. Can longitudinal changes in processing speed explain longitudinal age changes in fluid intelligence? Psychol Aging 2002; 17: 690–695. DOI: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bishnoi A, Hernandez ME. Dual task walking costs in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health 2021; 25: 1618–1629. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1802576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Q, Chan JSY, Yan JH. Mild cognitive impairment affects motor control and skill learning. Rev Neurosci 2016; 27: 197–217. DOI: 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donnell DE, Milne KM, James MD, et al. Dyspnea in COPD: new mechanistic insights and management implications. Adv Ther 2020; 37: 41–60. DOI: 10.1007/s12325-019-01128-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davenport PW, Vovk A. Cortical and subcortical central neural pathways in respiratory sensations. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2009; 167: 72–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Leupoldt A, Farre N. The load of dyspnoea on brain and legs. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001096. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01096-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodd JW, Getov SV, Jones PW. Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J 2010; 35: 913–922. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00125109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorond FA, Cruz-Almeida Y, Clark DJ, et al. Aging, the central nervous system, and mobility in older adults: neural mechanisms of mobility impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015; 70: 1526–1532. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/glv130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005; 8: 19–32. DOI: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010; 5(69): 69. DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 1291–1294. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka T, Basoudan N, Melo LT, et al. Deoxygenation of inspiratory muscles during cycling, hyperpnoea and loaded breathing in health and disease: a systematic review. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2018; 38: 554–565. DOI: 10.1111/cpf.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52: 377–384. DOI: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease . Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93: 391–398. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abumossalam A, Sheta A, Ahmed S, et al. Extra pulmonary boosting in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: leverage of piracetam as an adjunctive therapy on respiratory and neuropsychiatric functions in patients with chronic obstructure pulmonary disease. The Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis 2021; 70: 60–70. DOI: 10.4103/ejcdt.ejcdt._112_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrianopoulos V, Gloeckl R, Schneeberger T, et al. Benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients with mild cognitive impairment - A pilot study. Respir Med 2021; 185(106478): 106478. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antonelli-Incalzi R, Corsonello A, Trojano L, et al. Correlation between cognitive impairment and dependence in hypoxemic COPD. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2008; 30: 141–150. DOI: 10.1080/13803390701287390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aquino G, Iuliano E, di Cagno A, et al. Effects of combined training vs aerobic training on cognitive functions in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 711–718. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S96663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnevie T, Medrinal C, Combret Y, et al. Mid-term effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on cognitive function in people with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2020; 15: 1111–1121. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S249409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleutjens FAHM, Spruit MA, Ponds RWHM, et al. The impact of cognitive impairment on efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017; 18: 420–426. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cleutjens FAHM, Spruit MA, Ponds RWHM, et al. Cognitive impairment and clinical characteristics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2018; 15: 91–102. DOI: 10.1177/1479972317709651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cruthirds CL, van der Meij BS, Wierzchowska-McNew A, et al. Presence or absence of skeletal muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with distinct phenotypes. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2021; 57: 264–272. DOI: 10.1016/j.arbres.2019.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dag E, Bulcun E, Turkel Y, et al. Factors influencing cognitive function in subjects with COPD. Respir Care 2016; 61: 1044–1050. DOI: 10.4187/respcare.04403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dal Negro RW, TestA A, Aquilani R, et al. Essential amino acid supplementation in patients with severe COPD: a step towards home rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012; 77: 67–75. DOI: 10.4081/monaldi.2012.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emery CF. Effects of age on physiological and psychological functioning among COPD patients in an exercise program. J Aging Health 1994; 6: 3–16. DOI: 10.1177/089826439400600101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emery CF, Leatherman NE, Burker EJ, et al. Psychological outcomes of a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Chest 1991; 100: 613–617. DOI: 10.1378/chest.100.3.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emery CF, Schein RL, Hauck ER, et al. Psychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Psychol 1998; 17: 232–240. DOI: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etnier JL, Berry M. Fluid intelligence in an older COPD sample after short- or long-term exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33: 1620–1628. DOI: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrari M, Vangelista A, Vedovi E, et al. Minimally supervised home rehabilitation improves exercise capacity and health status in patients with COPD. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 83: 337–343. DOI: 10.1097/01.phm.0000124437.92263.ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.France G, Orme MW, Greening NJ, et al. Cognitive function following pulmonary rehabilitation and post-discharge recovery from exacerbation in people with COPD. Respir Med 2021; 176(106249): 20201121. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gore S, Blackwood J, Ziccardi T. Associations between cognitive function, balance, and gait speed in community-dwelling older adults with copd. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2021: 20210729. DOI: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassan SA, Campos MA, Kasawara KT, et al. Changes in oxyhemoglobin concentration in the prefrontal cortex during cognitive-motor dual tasks in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2020; 17: 289–296. DOI: 10.1080/15412555.2020.1767561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heraud N, Alexandre F, Gueugnon M, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on cognitive and motor performances in dual-task walking. COPD 2018; 15: 277–282. DOI: 10.1080/15412555.2018.1469607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karpman C, DePew ZS, LeBrasseur NK, et al. Determinants of gait speed in COPD. Chest 2014; 146: 104–110. DOI: 10.1378/chest.13-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaygusuz MH, Oral Tapan O, Tapan U, et al. Balance impairment and cognitive dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease under 65 years. Clin Respir J 2022; 16: 200–207. DOI: 10.1111/crj.13469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilic B, Cicek HS, Avci MZ. Comparing the effects of self-management and hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs in COPD patients. Niger J Clin Pract 2021; 24: 362–368. DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp._165_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kozora E, Emery CF, Ellison MC, et al. Improved neurobehavioral functioning in emphysema patients following lung volume reduction surgery compared with medical therapy. Chest 2005; 128: 2653–2663. DOI: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kozora E, Tran ZV, Make B. Neurobehavioral improvement after brief rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2002; 22: 426–430. DOI: 10.1097/00008483-200211000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lavoie KL, Sedeno M, Hamilton A, et al. Behavioural interventions targeting physical activity improve psychocognitive outcomes in COPD. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00013.02019. DOI: 10.1183/23120541.00013-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu H, Yang X, Wang X, et al. Study on adjuvant medication for patients with mild cognitive impairment based on vr technology and health education. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2021; 2021(1187704): 1187704. DOI: 10.1155/2021/1187704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morlino P, Balbi B, Guglielmetti S, et al. Gait abnormalities of COPD are not directly related to respiratory function. Gait Posture 2017; 58: 352–357. DOI: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozsoy I, Ozsoy G, Kararti C, et al. Cognitive and motor performances in dual task in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparative study. Ir J Med Sci 2021; 190: 723–730. DOI: 10.1007/s11845-020-02357-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ozyemisci-Taskiran O, Bozkurt SO, Kokturk N, et al. Is there any association between cognitive status and functional capacity during exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Chron Respir Dis 2015; 12: 247–255. DOI: 10.1177/1479972315589748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park JK, Deutz NEP, Cruthirds CL, et al. Risk factors for postural and functional balance impairment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 609. DOI: 10.3390/jcm9020609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park SK. Trajectories of change in cognitive function in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 1529–1542. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park SK, Larson JL. Cognitive function as measured by trail making test in patients with COPD. West J Nurs Res 2015; 37: 236–256. DOI: 10.1177/0193945914530520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Randeep M, Archana D, Malay S, et al. Cognitive domain impaired in COPD patients and its correlation with exercise capacity in COPD patients. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences 2019; 10: 1132–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roncero C, Campuzano AI, Quintano JA, et al. Cognitive status among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 543–551. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S100850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosenstein B, Smyrnova A, Rizk A, et al. Short- and long-term changes in cognitive function after exercise-based rehabilitation in people with COPD: a pilot study. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine 2021; 5: 300–309. DOI: 10.1080/24745332.2020.1790060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schure MB, Borson S, Nguyen HQ, et al. Associations of cognition with physical functioning and health-related quality of life among COPD patients. Respir Med 2016; 114: 46–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soysal Tomruk M, Ozalevli S, Dizdar G, et al. Determination of the relationship between cognitive function and hand dexterity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a cross-sectional study. Physiother Theory Pract 2015; 31: 313–317. DOI: 10.3109/09593985.2015.1004768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tudorache E, Fildan AP, Frandes M, et al. Aging and extrapulmonary effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Interv Aging 2017; 12: 1281–1287. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S145002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Beers M, Mount SW, Houben K, et al. Working memory training efficacy in COPD: the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Cogtrain trial. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00475.02021. DOI: 10.1183/23120541.00475-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Hove O, Cebolla AM, Andrianopoulos V, et al. The influence of cognitive load on static balance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Clin Respir J 2021; 15: 351–357. DOI: 10.1111/crj.13307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yazar EE, Aydin S, Gunluoglu G, et al. Clinical effects of cognitive impairment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2018; 15: 306–314. DOI: 10.1177/1479972317743757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yohannes AM, N Eakin M, Holbrook JT, et al. Association of mild cognitive impairment and characteristic of COPD and overall health status in a cohort study. Expert Rev Respir Med 2021; 15: 153–159. DOI: 10.1080/17476348.2021.1838278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Loughran KJ, Atkinson G, Beauchamp MK, et al. Balance impairment in individuals with COPD: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Thorax 2020; 75: 539–546. DOI: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]