Abstract

ZYIL1 is a nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain‐containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome inhibitor, which prevents NLRP3‐induced apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain oligomerization, thus inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. We investigated the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic profiles of ZYIL1 after single and multiple doses in healthy subjects. The subjects aged 18–55 years were enrolled in 2 different studies: single and multiple ascending dose. Blood/urine samples were collected at designated time points for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis. In the single‐ascending‐dose study, 30 subjects were enrolled (6 subjects each in 5 dose groups). One adverse event was reported during the study. ZYIL1 was well absorbed with median time to maximum plasma concentration at 1–1.5 hours. The exposures were dose proportional across the dose ranges. ZYIL1 is excreted as an unchanged form via the renal route. The mean elimination half‐life was 6–7 hours. In the multiple‐ascending‐dose study, 18 subjects were enrolled (6 subjects each in 3 dose groups). Eleven adverse events were reported by 6 subjects during the study. The accumulation index at steady state for area under the plasma concentration–time curve indicated that ZYIL1 has a marginal accumulation upon repeated dosing. Dose‐proportional exposure was observed across the dose ranges. All subjects showed >90% interleukin (IL)‐1β inhibition in all dose groups for both studies. Inhibition in IL‐1β and IL‐18 was observed throughout the 14 days of treatment in the multiple‐dose study. The safety profile, rapid absorption, marginal accumulation, and significant inhibition of IL‐1β and IL‐18 level support its development for the management of inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: healthy subjects, NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, safety, ZYIL1

The mammalian immune system defends against internal and external threats using innate immunity and adaptive immunity. The innate immune response relies on pattern‐recognition receptors to target pathogenic microbes and other endogenous or exogenous pathogens. Pattern‐recognition receptors are expressed mainly in immune and inflammatory cells. Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes formed by innate immune sensors, including nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)‐like receptor protein (NLR) family members nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain‐containing 1 (NLRP1), nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat and pyrin domain‐containing 3 (NLRP3), and nucleotide‐binding domain and leucine‐rich repeat receptor CARD domain‐containing protein 4, along with other non‐NLR receptors such as interferon‐inducible proteins. NLRP3 inflammasome activation is dependent on 2 successive signals. The first step comprises an initiating signal (priming) in which many danger‐associated molecular patterns and pathogen‐associated molecular patterns are recognized by toll‐like receptors, which in turn upregulates transcription of inflammasome‐related components, including inactive NLRP3, pro‐interleukin (IL)‐1β, and pro‐IL‐18. In the second step of inflammasome activation, the oligomerization of NLRP3 and subsequent assembly of NLRP3, apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a CARD (ASC), and procaspase‐1 results in formation of a complex. This triggers the transformation of procaspase‐1 to caspase‐1, leading to the release of active proinflammatory cytokines IL‐1β and IL‐18. 1 , 2 , 3

The NLRP3 protein is made up of 3 domains: a leucine‐rich repeat domain and a nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain, and a pyrin domain (PYD). Upon activation, NLRP3 oligomerizes and triggers the assembly of the adapter ASC via PYD–PYD interactions. ASC fibrils assemble into large structures, called ASC specks, and recruit pro‐caspase‐1, leading to its autoproteolytic activation. The activated caspase‐1 can cleave pro‐IL‐1β and pro‐IL‐18 to generate the inflammatory cytokines IL‐1β and IL‐18. 4 , 5

IL‐1β is a key proinflammatory cytokine involved in the mediation of inflammation in almost every cell type and tissue where its levels and activities are correlated with the pathogenesis of various autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases. IL‐18 belongs to the same family of IL‐1 cytokines. IL‐18 and IL‐1β share similar mechanisms of activation, receptor structure, and signal transduction pathways. IL‐18 is a pleiotropic cytokine that provides an important link between the innate and adaptive immune responses and is involved in the regulation of both. 6

IL‐1β has been identified to be one of the major causal cytokines, responsible for disease initiation and progression in multiple inflammatory diseases like cryopyrin‐associated periodic syndrome (CAPS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and Parkinson disease. 7 , 8 , 9

The CAPS is a group of rare inherited innate immune inflammatory disorders due to gain of function mutations in the gene for the NOD‐like receptor known as NLRP3, resulting in dysregulation of IL‐1 mediated inflammation. There are 3 CAPS subtypes of varying severity including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome, and neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID). Targeting IL‐1 in patients with all subtypes in the spectrum has decreased disease‐related symptoms and improved patients’ quality of life. 10

IBD is an umbrella term used to describe disorders that involve chronic inflammation of the digestive tract. It usually involves severe diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss. It is well known that IL‐1β is a constitutive component of the mixture of proinflammatory cytokines that are responsible for the inflammation occurring in patients with IBD, and elevations in IL‐1β levels are associated with increased disease severity. 11 , 12

Proposed etiology of Parkinson disease suggests microglia activation in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and other affected regions, as well as increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition exerted dopaminergic neuroprotection in cellular or animal models of Parkinson disease. 13 , 14 , 15

The NLRP3 inflammasome is the best understood and widely studied because of its role in host defense and innate immunity. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a potential target for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases. ZYIL1 is an oral NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor that prevents NLRP3‐induced ASC oligomerization, thus inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasomes pathway.

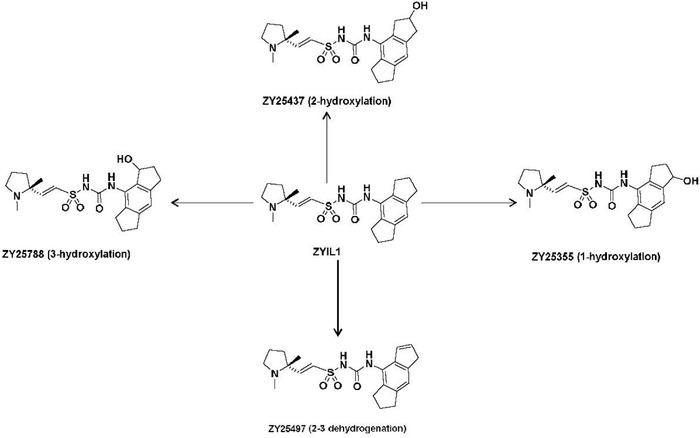

In vivo disposition of ZYIL1 and metabolic fate across the animals and humans was studied in pooled liver microsomes. ZYIL1 was found to be metabolically stable in mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human liver microsomes. Further, in vitro samples were investigated for formation of ZYIL1‐related metabolites, and a total of 5 metabolites have been identified; 3 are putative mono‐oxygenation and 2 are putative dehydrogenation metabolites. This phase 1 metabolite formation is mediated through cytochrome P450 drug‐metabolizing enzymes, and their abundance was very low. Four of 5 metabolites were characterized in animals and humans, 1 and 2‐hydroxy metabolites of ZYIL1 were weakly active, whereas 3‐hydroxy and 2–3 dehydrogenation metabolites are pharmacologically active and its activity was similar to the activity of the parent, ZYIL1. The structural formula of ZYIL1 and its metabolites is provided in Figure 1. To understand the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties and ZYIL1 disposition in human, these metabolite estimations were carried out in human clinical study.

Figure 1.

Structural formula of ZYIL1 and its metabolites.

Materials and Methods

Studies were conducted at Zydus Research Centre (Ahmedabad, India) following approval by the Sangini Hospital Ethics Committee (Ahmedabad, India). All participants gave written informed consent before enrollment. This study was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI) and on Clinicaltrials.gov with the trial reference identifiers CTRI/2020/12/030045 and NCT04731324 for study 1 and CTRI/2021/07/034692 and NCT0497218 for study 2, respectively.

Study Design and Participants

Study 1 was a prospective, open‐label, single‐dose, and single‐arm study of ZYIL1 in healthy human subjects.

The study was conducted in 5 ascending‐dose groups (25, 50, 100, 250, and 400 mg). The decision to proceed to the next dose level was made by both investigator and sponsor medical expert based on the safety and PK data evaluation of previous cohorts. Initially, 3 cohorts were conducted (25, 50, and 100 mg). Interim analysis was performed at the end of cohort 3, and data were presented to the regulatory authority to decide on further dose escalation. Subjects were screened within 28 days of drug administration. All subjects were admitted to the clinical research unit on day −2 (48 hours before dosing) and were discharged 72 hours after dosing, which was the end of the study day.

Study 2 was a prospective, open‐label, and multiple‐dose study of ZYIL1 in healthy human subjects.

Men and women (nonpregnant, nonlactating) of good health aged 18–55 years and weighing 50–100 kg with body mass index ranging from 18.5 to 30 kg/m2 were eligible for inclusion in the studies.

Details of the demographic profiles of enrolled subjects (single‐ascending‐dose and multiple‐ascending‐dose study) is provided in Supporting Information Tables S6 and S7, respectively. Subject disposition (single‐ascending‐dose and multiple‐ascending‐dose study) is shown in Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2, respectively.

Procedure

Study 1 was conducted in 5 dose cohorts (25, 50, 100, 250, and 400 mg) of 6 subjects each. Eligible healthy subjects were enrolled within a 28‐day screening period to ensure that subjects met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria.

Subjects were admitted to the clinical research unit on day −2 (48 hours before dosing) and were discharged 72 hours after dosing (end of study). Participants received a single oral dose of ZYIL1 (active pharmaceutical ingredient in capsule) with 240 mL water after fasting for at least 10 hours; no food was allowed until 4 hours after dosing. In each dose cohort, 2 subjects were dosed first. The investigator reviewed safety data up to at least 24 hours after dosing before deciding to proceed with dosing the remaining 4 participants in the cohort. The starting dose of ZYIL1 used in the single‐ascending‐dose study (25 mg) was calculated in accordance with guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration. The investigator and sponsor medical expert decided the dose for the next cohort based on the review of PK, safety, and tolerability data of the previous cohort.

Study 2 was conducted in 3 dose cohorts (12.5, 50, and 100 mg) of 6 subjects each. Eligible healthy subjects were enrolled within a 28‐day screening period to ensure that subjects met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Subjects were admitted to the clinical research unit on day −1 (24 hours before first dosing), followed by twice‐daily treatment for 14 days under housing condition, and were discharged 36 hours after the last dose on day 16. Then, the subjects reported for outpatient visit (end‐of‐study visit) on day 19. Participants received oral doses of ZYIL1 (active pharmaceutical ingredient in capsule) twice daily for 14 days with 240 mL water after fasting for at least 2 hours; no food was allowed until 2 hours after dosing. The dose‐escalation decision for each cohort was made by investigators and sponsor medical experts based on the safety evaluation of previous cohorts. Inclusion/exclusion criteria used for the subject selection is provided in Supporting Information Table S8.

Blood Sampling for PK

In studies 1 and 2, venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected in dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K2‐EDTA) vacutainers at defined time points. In study 1, blood samples were collected up to 48 hours following study drug administration, and in study 2 blood samples were collected until the end of the study (day 19) for evaluation of PK parameters. Plasma was separated from the blood samples and stored frozen at −70 ± 20°C until analysis.

Urine Sampling for PK

In study 1, urine samples were collected before dosing and intervals of 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–24, 24–36, and 36–48 hours following study drug administration. A pooled urine sample was collected from total urine collected at each interval and 2 aliquots (around 4.5 mL each) of the samples were stored frozen at −70 ± 20°C until analysis.

Blood Sampling for Pharmacodynamics

In study 1, 5 venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected in K2‐EDTA vacutainers at defined time points up to 24 hours following study drug administration and in study 2, 5‐mL blood samples (a total of 13 blood samples) were collected in K2‐EDTA up to day 15 following study drug administration.

Safety Assessments

In both studies, safety was evaluated by the incidence, severity, and relationship of adverse events (AEs), clinical examination, frequent vital signs, triplicate 12‐lead ECGs along with evaluation of median corrected QT interval for any changes in corrected QT interval compared to baseline, and clinical laboratory investigations (hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis).

Study Sample Bioanalysis

The concentration of ZYIL1 in plasma and urine samples was determined using separately validated liquid chromatography–tandem spectrometry assays. The assays were validated in accordance with the Food and Drug Administration guideline for Bioanalytical Method Validation (May 2018). The assays were selective, sensitive, and free from any carryover. The study samples were analyzed along with calibration standard curve and quality control (QC) samples distributed throughout each analytical run. Chromatographic separation of analyte and internal standard from endogenous matrix components of plasma and urine samples was achieved on an ACE 5 C18 analytical column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California). The mobile‐phase composition was (a) 0.05% formic acid in water and (b) a solvent mixture of methanol and acetonitrile (50:50 v/v) for the gradient elution. ZY20378, an analog compound, was used as the internal standard for estimation of ZYIL1 in both plasma and urine assays. The quantitative determination of ZYIL1 was performed using a turbo electrospray ionization source in positive mode in plasma matrix and negative ionization mode for urine matrix. The mass transitions were used (m/z) 404.2 to 205.2, 231.1, 124.1 for ZYIL1 and (m/z) 384.1 to 185.1, 104.1 for internal standard for plasma assay. For urine assay, the mass transitions were (m/z) 402.0–203.1 for ZYIL1 and (m/z) 382.2–183.1 for internal standard. ZYIL1 and internal standard were extracted from plasma samples using a protein precipitation procedure and urine samples were processed by solid‐phase extraction. The extraction efficiency of ZYIL1 and internal standard ranged from 93.6% to 96.9% and 91.2% to 94.1% for both plasma and urine assay, respectively. The calibration curve range was 0.01–40 μg/mL for plasma and 5–10,000 ng/mL for urine assay. The accuracy (percent relative standard error) and precision (percent coefficient of variation) of interrun QC samples at low level, medium level, and high level was −2.5% to 3.1% and −5.2% to 4.1% and 0%–3.8% and 2%–5.5% for plasma and urine assay respectively and met the predefined acceptance limit. The chromatographic data were processed using analyst software with a 1/x2 weighing factor in the linear regression model.

The measurement of hydroxyl metabolites (ZY‐25437, ZY‐25355, ZY‐25788, and ZY‐25497) in plasma and urine samples was performed using fit‐for‐research liquid chromatography–tandem spectrometry assays. Two separate assays were established in each plasma and urine matrix; one was the simultaneous estimation of 3 metabolites (ZY‐25437, ZY‐25355, and ZY‐25788), and another was a single metabolite (ZY‐25497) assay. For quantitation analysis, the ionization of metabolites was achieved using a turbo electrospray ionization source in positive mode. The mass transitions used were (m/z) 420.2–205.2, 420.1–205.2, 450.3–231.2, 402.2–205.2, and 309.2–281.1 for ZY‐25437, ZY‐25355, ZY‐25788, ZY‐25497, and internal standard, respectively. The study samples were analyzed in multiple runs and each run comprised of calibration standards and interspersed QC samples. The QC samples met the predefined acceptance criteria for each plasma and urine matrix.

Pharmacodynamics Assay

For pharmacodynamic (PD) assessment, NLRP3 was activated in the whole blood collected from clinical trial volunteers post‐ZYIL1 dosing and corresponding levels of secreted IL‐1β and IL‐18 were measured. Peripheral venous blood from each volunteer was collected at different time points in prelabeled K2EDTA vacutainers and stored at 2–8°C till PD assessment. For the assessment, whole blood was taken in a 96‐well plate in triplicate and treated with 500 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (Sigma–Aldrich, Mumbai, India) followed by incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 4 hours. After 4 hours, 5 mM of adenosine triphosphate (Sigma–Aldrich) was added, and incubation was continued for another hour. At the end of the experiment, blood was spun down, and supernatant was removed and analyzed for IL‐1β and IL‐18 levels using the enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay method. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 The levels of IL‐1β and IL‐18 were derived using the standard curve method. The readings were well within the calibration range, and variability was <5% coefficient of variation.

Statistical Analysis

The target sample size of 6 participants per cohort was based on general phase 1 trial experience and was considered appropriate to investigate for the primary safety outcome.

Noncompartmental PK parameters were calculated from Phoenix WinNonlin software version 8.2 (Certara, Princeton, New Jersey) for study 1 and Phoenix WinNonlin software version 8.3 for study 2. Data sets were derived on the basis of source data. Listing of subject data, tabulation of descriptive statistics and statistical analysis were performed primarily using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, geometric mean, and coefficient of variation) were used for PK and safety analysis. Dose relationships with maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) from time 0 to the last measurable concentration were evaluated using correlation and regression analysis for different doses. The accumulation index (RAUC) was calculated as a ratio of accumulation of a drug under steady state conditions (ie, after repeated administration) as compared to a single dose (RAUCtau = AUC over the dosing interval [AUC0–tau] at day 14/AUC0–tau at day 1). Descriptive statistics (n, mean, median, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation) of the cytokines (IL‐1β and IL‐18 for study 1; IL‐1β, IL‐18, IL‐6, and tumor necrosis factor‐α for study 2) whole blood concentration were summarized by dose and time point. Percentage of IL‐1β inhibition was calculated as [(treated concentration before dosing − untreated concentration before dosing) − (treated concentration at Rx time point − untreated concentration at Rx time point)]/(treated concentration before dosing − untreated concentration before dosing) × 100%. The percentage of cytokine inhibition in stimulated whole blood was estimated, listed, and summarized by dose and time point for each cohort.

Results

Safety and Tolerability

Study 1: One AE (low white blood cell count) was reported in the 250‐mg dose group during the study. The AE was possibly related to study medication and resolved without any concomitant medication. No serious AE was observed during the study in any dose group. No clinically relevant trend or change was observed in the clinical laboratory, vital signs, physical examination, and ECG findings in any of the dose groups.

Study 2: A total of 11 AEs in 6 of 18 subjects were reported during the study, including constipation, headache, pyrexia, glycosuria, nasopharyngitis, decrease in neutrophil count, increase in transaminases, alanine aminotransferase, and triglycerides. Out of the 11 AEs reported, most (8) were mild in severity, 1 was moderate (increase in transaminases), and 2 were severe (increase in triglyceride and decrease in neutrophil count). Most of the AEs (5) were possibly related, 3 were probably related, and 3 were not related to the study medication. All these AEs were resolved without sequelae. One subject reported an AE leading to discontinuation of treatment in the 100‐mg multiple‐ascending‐dose cohort due to moderate elevation of transaminase on day 6. The remaining 17 subjects completed the 14 days of treatment. No serious AE was observed during the study in any dose group. No clinically relevant trend or change was observed in the clinical laboratory, vital signs, physical examination, and ECG findings in any of the dose groups. No consistent pattern or dose dependency was observed in the AEs.

Details of AEs with system organ class and preferred terms is provided in Supporting Information Table S1.

Overall ZYIL1 was well tolerated up to a 400‐mg single oral dose and up to oral doses of 100 mg twice a day for 14 days.

Pharmacokinetics

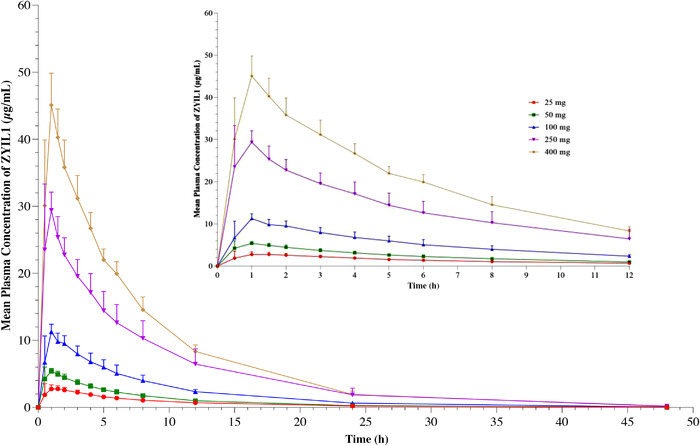

Study 1: ZYIL1 was well absorbed after oral administration under fasting conditions. The absorption was rapid, with a median time to maximum plasma concentration of 1–1.5 hours across the dose range. The exposure (Cmax and AUC) increased dose proportionally across the dose range. The mean elimination half‐life of ZYIL1 across the doses ranged from 5.7 to 6.7 hours. The PK parameters of ZYIL1 determined in the single‐ascending‐dose study are presented in Table 1. The concentration–time profiles of ZYIL1 (mean ± standard error of the mean) after administration of 25, 50, 100, 250, and 400 mg and dose linearity plots are shown in Figure 2 and Supporting Information Figure S3, respectively. The concentration–time profiles of ZYIL1 metabolites (mean ± standard error of the mean) after administration of 25, 50, 100, 250, and 400 mg are shown in Supporting Information Figure S4.

Table 1.

PK Parameters of ZYIL1 in Single‐Ascending‐Dose Study

| PK Parameters | 25 mg (N = 6 a ) | 50 mg (N = 6) | 100 mg (N = 6) | 250 mg (N = 6) | 400 mg (N = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tmax (h) | 1.5 (0.5, 2) | 1 (0.5, 2) | 1 (0.5, 1.5) | 1 (0.5, 1) | 1 (1, 1) |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 3.2 (0.8) | 5.7 (0.5) | 11.5 (1) | 30.4 (3.8) | 45.1 (4.8) |

| AUC0–t (μg • h/mL) | 27 (0.4) | 40.8 (7.2) | 92.3 (14.9) | 245 (64.8) | 340.9 (30.6) |

| AUC0–inf (μg • h/mL) | 27.1 (0.4) | 41.4 (6.6) | 92.8 (15.3) | 247.1 (66.5) | 341.8 (30.8) |

| t1/2 (hour) | 6.5 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.7) | 6.5 (1.5) | 5.7 (0.5) |

| CL/F (L/h) | 0.9 (0) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.1) |

| Amount recovered (mg) | 21.2 (7.7) | 34.6 (6.2) | 76.6 (19.5) | 172.7 (20.7) | 201.3 (109.5) |

| Percent recovered (%) | 84.8 (30.7) | 69.1 (12.3) | 76.6 (19.5) | 69.1 (8.3) | 50.3 (27.3) |

AUC0–inf, area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; AUC0–t, area under the curve concentration–time curve from time 0 to the time of the last measurable concentration; CL/F, clearance rate; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; PK, pharmacokinetic; SD, standard deviation; t1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; tmax, time to maximum plasma concentration.

Data are expressed as mean (SD), except for tmax, which is shown as median (min, max).

N = 6 for Cmax, tmax, amount recovered and percent recovered while for the rest of the PK parameters, N = 5.

Figure 2.

Line plot for the mean (±standard error of the mean) concentration‐time profiles for ZYIL1 after administration of 25‐, 50‐, 100‐, 250‐, and 400‐mg doses to healthy human subjects.

Descriptive statistics of the amount of ZYIL1 recovered in urine and percent recovered are presented in Table 1. Mean cumulative percentage urinary recovery of ZYIL1 was ranging from 50% to 85% across dose range, indicating the renal route is a primary route of ZYIL1 excretion.

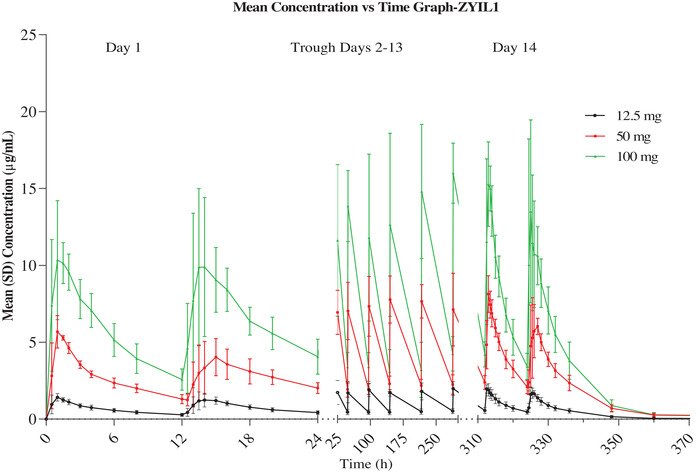

Study 2: ZYIL1 was well absorbed after multiple‐ascending‐dose oral administration. The absorption was rapid at a steady state. The Cmax,ss1 (Cmax after first dose) and Cmax,ss2 (Cmax after second dose) values were from 2 to 16.4 and 1.8 to 16.1 μg/mL across the dose range. The PK parameters of ZYIL1 in the multiple dose study at D1 and D14 are presented in Table 2. The results indicated that exposure increased in a predictable manner with increasing doses. The mean plasma drug concentration–time profiles of ZYIL1 and its metabolites at D1 and D14 of 12.5‐, 50‐, and 100‐mg dose groups are presented in Figure 3 and Supporting Information Figure S5, respectively. The mean plasma drug concentration–time profiles at D1 and D14 of 12.5, 50, and 100‐mg dose groups are presented in Figure 3. The accumulation index at steady state for AUC0–tau ranged from 1.4 to 1.6 across the dose range, which indicated that ZYIL1 has a marginal accumulation upon repeated dosing.

Table 2.

PK Parameters of ZYIL1 in Multiple‐Ascending‐Dose Study at Days 1 and 14

| PK Parameters | 12.5 mg (N = 6) | 50 mg (N = 6) | 100 mg (N = 6 a ) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D14 | D1 | D14 | D1 | D14 | |

| AUC0–tau (μg • h/mL) | 7.7 (1.7) | – | 31.6 (3.7) | – | 66.8 (7.3) | – |

| AUC0–24BID (μg • h/mL) | 16.9 (4) | ‐ | 65.5 (8.2) | ‐ | 145.2 (18.3) | – |

| tmax,ss1 (h) | – | 0.8 (0.5, 1) | – | 1 (1, 1) | – | 1 (0.5, 1.5) |

| Cmax,ss1 (μg/mL) | – | 2 (0.3) | – | 8.1 (1.2) | – | 16.4 (1.3) |

| tmax,ss2 (hour) | – | 1.5 (1, 2) | – | 2.1 (1) | – | 1 (0.5, 3) |

| Cmax,ss2 (μg/mL) | – | 1.8 (0.3) | – | 6.7 (1.1) | – | 16.1 (4.5) |

| AUC0–tau (μg • h/mL) | – | 12 (2.7) | – | 51.2 (7.5) | – | 92.9 (13.5) |

| AUC0–24BID (μg • h/mL) | – | 23.5 (5) | – | 97.7 (15.3) | – | 181.5 (30.4) |

| AUC0–t (μg • h/mL) | – | 28.9 (7) | – | 121.8 (21.4) | – | 216.5 (41.1) |

| AUC0–inf (μg • h/mL) | – | 29.4 (7.5) | – | 124.8 (23) | – | 219.1 (42.7) |

| RAUCtau | – | 1.6 (0.2) | – | 1.6 (0.1) | – | 1.4 (0.1) |

| RAUC24BID | – | 1.4 (0.1) | – | 1.5 (0.2) | – | 1.3 (0.1) |

AUC0–inf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; AUC0–24BID, area under the concentration‐time curve over 24 hour for day 1 and 14 separately; AUC0–t, area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 to the time of the last measurable concentration; AUC0–tau, area under the plasma concentration–time curve over the dosing interval; Cmax,ss1, maximum plasma concentration at steady state after the first dose; Cmax,ss2, maximum plasma concentration at steady state after the second dose; PK, pharmacokinetic; RAUC24BID, accumulation ratio for AUC0‐24BID; RAUCtau, accumulation ratio for AUCtau; SD, standard deviation; tmax,ss1, time to maximum plasma concentration at steady state after the first dose; tmax,ss2, time to maximum plasma concentration at steady state after the second dose.

Dosing interval (tau) was 12 hours.

Data are expressed as mean (SD), except for tmax, which are shown as median (min, max).

N = 6 for D1 PK parameters and N = 5 for D14 PK parameters.

Figure 3.

Line plot for the mean (±standard error of the mean) concentration–time profile of ZYIL1 at days 1 and 14 after administration of 12.5‐, 50‐, and 100‐mg doses to healthy human subjects.

All PK plasma samples of studies 1 and 2 and urine samples of study 1 were analyzed for the determination of metabolites. Four minor metabolites (ZY‐25437, ZY‐25355, ZY‐25788, and ZY‐25497) were quantified in the systemic circulation as well as in urine. The percentage of each metabolite was <2% of the parent exposure in plasma and urinary amount (percentage of parent dose) of each metabolite was ranged from 0.2% to 3.2%, and data are presented in Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3.

Pharmacodynamics

Study 1: The PD results indicated that most of the subjects showed >90% inhibition of IL‐1β and >70% inhibition of IL‐18 after ZYIL1 administration. A single dose of 25‐, 50‐, and 100‐mg ZYIL1 showed ex vivo IL‐1β inhibition >90% until 6, 12, and 24 hours after dosing, respectively. Ex vivo IL‐1β inhibition >90% was also observed until 24 hours after dosing with a 250‐ and 400‐mg single dose of ZYIL1.

Study 2: The PD results indicated that the subjects showed around 90% inhibition of IL‐1β and IL‐18 until 12 hours after the last dose in the 12.5‐mg dose group and until 36 hours after the last dose in the 50‐ and 100‐mg dose group. There was no remarkable inhibition observed for IL‐6 and tumor necrosis factor‐α in all dose groups. The descriptive statistics of IL‐1β and IL‐18 inhibition (percentage) on corrected IL‐1β and IL‐18 levels in whole blood are presented in Supporting Information Tables S4 and S5. Individual subject IL‐1β and IL‐18 inhibition (percentage) on corrected IL‐1β and IL‐18 levels with mean (± standard deviation) bar are provided in Supporting Information Figures S6 and S7.

Discussion

ZYIL1 is an oral NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor that prevents NLRP3‐induced ASC oligomerization, thus inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. There are various agents (MCC950, CY‐09, OLT1177, Tranilast, Oridonin, NT‐0167, etc) in various stages of clinical development that directly target NLRP3 itself but not other components (NIMA‐related kinase 7, ASC, caspase‐1, or IL‐1β) up/downstream of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In these studies, the safety, tolerability, PK, and PD of ZYIL1 were evaluated in the healthy human subjects after a single ascending dose and multiple ascending doses. ZYIL1 was well absorbed and showed predictable PK and PD parameters when evaluated in the single ascending and multiple ascending dose study.

The first‐in‐human studies with a small number of healthy subjects demonstrated that ZYIL1 was well tolerated up to a single oral dose of 400 and 100 mg twice daily for 14 days.

The safety profile, rapid absorption, and mechanistic evidence of NLRP3 inhibition, supports continued development of ZYIL1 for the management of inflammatory disease (ie, CAPS). The CAPS are a group of rare inherited innate immune‐inflammatory disorders due to gain of function mutations in the gene for the NOD‐like receptor known as NLRP3, resulting in dysregulation of IL‐1–mediated inflammation. There are 3 CAPS subtypes of varying severity including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome, and NOMID. Targeting IL‐1 in patients with all subtypes in the spectrum has decreased disease‐related symptoms and improved patient's quality of life.

NLRP3 in innate immune cells is activated by pathogen‐associated molecular patterns and death‐associated molecular patterns. The resultant NLRP3 inflammasome activates caspase‐1 and in turn cleave and releases IL‐1b and IL‐18. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors have the potential to negate IL‐1–mediated disease pathologies including CAPS.

All current therapies (ie, anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab) are limited to injectable biologics that often have limited central nervous system penetration, which is particularly important in patients with NOMID with severe central nervous system disease. Therefore, there remains an unmet clinical need for more targeted and preferably small‐molecule compounds as an alternative to IL‐1 targeted biologics. Considering that the PK and PD characteristics in patients may be different from those in healthy subjects, a separate phase 2a study was planned to evaluate the safety, tolerability, PK, and PD of ZYIL1 in subjects with CAPS.

Although this trial provides valuable first‐in‐human data on ZYIL1, it has limitations. The population examined was healthy adult males, the majority of whom self‐selected their race as Asian. It will be important to investigate potential differences in safety and PK in target patient populations. As the trial was conducted only on male subjects, further investigation of sex differences in PK in future trials are warranted.

ZYIL1 was well tolerated up to a dose of 100 mg twice daily for 14 days in a multiple‐ascending‐dose study. All 3 doses (12.5, 50, and 100) in the multiple‐ascending‐dose group showed IL‐1β inhibition. Considering longer duration of IL‐1β inhibition, a ZYIL1 50‐mg twice‐daily dose was selected for the phase 2a trial in patients with CAPS.

Conclusion

ZYIL1 was well tolerated up to a single dose of 400 mg and multiple doses of 100 mg twice daily for 14 days. ZYIL1 displayed rapid oral absorption and was mainly eliminated via the renal route. Single and multiple doses of ZYIL1 showed that ex vivo inhibition of lipopolysaccharide/adenosine triphosphate stimulated IL‐1β and IL‐18 levels, which suggested mechanistic evidence of NLRP3 inhibition mediated by ZYIL1.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared no competing interests.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accept accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Dr. Deven Parmar and Dr. Kevinkumar Kansagra were responsible for the conceptualization, designing, and execution of the study. Dr. Taufik Momin, Dr. Hardik Patel and Dr. Gaurav Jansari were the study investigators. Dr. Mukul Jain was responsible for the execution and overseeing the bioanalytical analysis. Mr. Ajaykumar Barot and Mr. Ashok Ghoghari were responsible for the execution of bioanalytical analysis. Dr. Harilal Patel was responsible for the pharmacokinetic interpretation. Dr. Chintan Shah was responsible for the clinical data management. Dr. Kasinath Viswanathan and Mr. Bhavesh Sharma were responsible for Pharmaco dynamics analysis. Mr. Jayesh Patel has written this manuscript.

Funding

This trial was sponsored and funded by Zydus Lifesciences Limited, Ahmedabad, India.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This trial was sponsored and funded by Zydus Lifesciences Ltd. (formerly Cadila Healthcare Ltd.), Ahmedabad, India. The authors express their sincere appreciation to all colleagues involved in this study for their participation in this trial. The authors would like to acknowledge all the subjects who participated in this trial. The authors thank Kalpesh Gandhi and his team for pathology laboratory support; Sourabh Shah for support in preparation of the clinical study report; Denison Macwan, Kamal Jaimine, Nimesh Patel, Jaydeep Kapadia, and Manish Patel for phlebotomy and nursing activities; Dr. Chintan Shah for data management activities; Vishal Nakrani, Maulik Shah, and Umesh Patel for quality control; Chetan Shingala, Sanket Patel, and Abdulkasim Gohel for quality assurance; Harsh Bhavsar for PD analysis. All authors are employees of Zydus Lifesciences Limited. This report was prepared by the authors, who had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1. Shao BZ, Xu ZQ, Han BZ, Su DF, Liu C. NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agarwal S, Sasane S, Shah H, et al. Discovery of N‐Cyano‐sulfoximineurea derivatives as potent and orally bioavailable NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11:414‐418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zahid A, Li B, Kombe AJK, Jin T, Tao J. Pharmacological inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JW. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin‐1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(8):633‐652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JP. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):677‐687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dubuisson N, Versele R, Davis‐López de Carrizosa MA, Selvais CM, Brichard SM, Abou‐Samra M. Walking down skeletal muscle lane: from inflammasome to disease. Cells. 2021;10(11):3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corcoran SE, Hafner‐Bratkovič I, Halai R, et al. The NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 inhibits IL‐1β production in PBMC from 19 patients with Cryopyrin‐Associated Periodic Syndrome and in 2 patients with Schnitzler's syndrome [version 1; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:247. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ligumsky M, Simon PL, Karmeli F, Rachmilewitz D. Role of interleukin 1 in inflammatory bowel disease–enhanced production during active disease. Gut. 1990;31(6):686‐689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coccia M, Harrison OJ, Schiering C, et al. IL‐1β mediates chronic intestinal inflammation by promoting the accumulation of IL‐17A secreting innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209(9):1595‐1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang P, Dickson DW. Parkinson's disease: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(1):13‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sawada M, Imamura K, Nagatsu T. Role of cytokines in inflammatory process in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006;(70):373‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ou Z, Zhou Y, Wang L, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition prevents α‐synuclein pathology by relieving autophagy dysfunction in chronic MPTP‐treated NLRP3 knockout mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58(4):1303‐1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lang T, Lee JPW, Elgass K, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen KYH, Messina N, Germano S, et al. Innate immune responses following Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0191830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tang G, Han X, Lin Z, et al. Propionibacterium acnes accelerates intervertebral disc degeneration by inducing pyroptosis of nucleus pulposus cells via the ROS‐NLRP3 pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:4657014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonnekoh H, Vera C, Abad‐Perez A, et al. Topical inflammasome inhibition with disulfiram prevents irritant contact dermatitis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;11(5):e12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material