Abstract

Aims

Recent years have seen an exponential increase in the proportion of parents searching for online health information on their child's medical condition. We investigated the experiences, attitudes and approaches of paediatricians interacting with parents who search for online health information and the impact on the doctor–parent relationship.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted utilising semi‐structured interviews with 17 paediatric physicians, surgeons, anaesthetists and trainees working in an Australian children's hospital. Data were analysed through deductive and inductive thematic analysis using line‐by‐line coding.

Results

Three key themes were identified: paediatricians' experiences with, and attitudes towards, parents using online health information; paediatricians' communication approaches; and the perceived impact on the doctor–parent relationship. These themes demonstrated that most paediatricians acknowledged the information parents found and directed parents to reliable websites. Following discussions with Internet‐informed parents, a few changed their management plans and a few reported discouraging parents from further searching online.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that paediatricians predominantly used patient‐centred communication strategies to care for patients in partnership with parents. Paediatricians contextualising online health information can contribute to a quality partnership with parents and facilitate shared decision‐making, potentially fostering better health outcomes for children. Our conclusions may inform clinicians' communication approaches when interacting with Internet‐informed parents and stimulate research about more effective doctor–parent communication approaches. In a digital age, paediatricians may benefit from employing more time‐efficient approaches to manage increasing workloads with their new role of digital stewardship of parents.

Keywords: consumer health information, digital health, health communication, patient education, physician–patient relations

What is already known on this topic

Physicians working in an adult patient context employ communication strategies that may resist (avoid), repair (discourage), coconstruct (contextualise) or enhance patients' search for online health information.

Most parents are increasingly using online health information for education about their child's medical condition and to gain more decision‐making power, although information they find can often be inaccurate or irrelevant.

Paediatricians have been identified as requiring greater support with adjusting to the ‘informed parent’, who may be misled by online health information and may be critical of the paediatrician's clinical practice.

What this paper adds

A framework that highlights the positive impact of patient‐centred communication approaches on the doctor–parent relationship, and a potential to improve paediatric health outcomes.

Parents bringing online health information to consultations increases time pressures as paediatricians often choose to contextualise the online health information, employing coconstructive communication strategies. Coconstructive strategies encourage parents' searching, direct them to reliable websites and facilitate shared decision‐making.

Paediatricians may be more open to adopt this new role of digital stewardship than physicians in a primary care or adult patient context. This highlights the need for education of both physicians and paediatricians to improve their use of more time‐efficient yet patient‐centred communication approaches in a digital age.

Few paediatricians use compromising communication approaches that could result in changed management plans for the child, covert dismissal approaches, repairing approaches and enhancing approaches.

The rise of the Internet over the last two decades has altered the doctor–patient and doctor–parent relationships. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Traditionally, the doctor was regarded as the primary source of health information; however, many parents now access online health information more readily than their child's doctor. 5 , 6 , 7

Parents and patients have become more active in health‐care decision‐making. 4 , 8 For some, increased empowerment has led to more collaborative consultations and balance in the doctor–patient or doctor–parent relationship. 4 , 9 , 10 Nevertheless, consultations have become more time‐consuming due to discussions of online health information. 11

Parents report limited opportunities to clarify uncertainties as doctors face reduced time with patients, resulting in fragmented care and parents prevented from being equal participants. 12 It is, therefore, unsurprising that patients and parents turn to the Internet as it is quick and readily available, particularly after hours. 13 Kubb and Foran's 3 systematic review highlights that anxiety is a significant motivator for parents searching online, whereas AlGhamdi and Moussa 14 report that curiosity is the major driver of patients' searches.

The proportion of Australian parents accessing online health information in the last decade has increased from 64 to 90%. 15 , 16 However, a Canadian cross‐sectional study highlighted that almost all online health information found by parents had readability scores that were too high for an average parent. 17 Nevertheless, Kubb and Foran 3 found parents rarely discuss online health information with their paediatrician, despite wishing for more guidance on finding reliable information. 16 There is a gap in the literature regarding how online health information impacts the way paediatricians communicate with parents.

A Swiss study investigated physicians' communication approaches with Internet‐informed adult patients. 1 Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz 1 found that 17 primary care physicians and medical specialists used one of four communication strategies when interacting with Internet‐informed patients: physician‐centred resistant or repairing strategies, or patient‐centred coconstructive or enhancing strategies. Physicians using resistant strategies dismissed information found by patients, while those using repairing strategies discouraged searching. Physicians using coconstructive strategies integrated the patient's perspective into the consultation and encouraged searching, while those using enhancing strategies equipped patients with tools to pursue good quality online health information. Coconstruction was considered the best approach to strengthen the doctor–patient bond. 1 , 6

These findings from an adult patient context may not be transferred to the paediatric context with confidence because parents report feeling more responsible making a decision on behalf of their child than for themselves. 8 Indeed, Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz 1 excluded paediatricians from their study due to the unique nature of their relationships with parents, where parents are usually an active third party.

Recent research highlights that the doctor–parent communication dynamic is changing as paediatricians are challenged by parents who may have been misled by online health information. 10 Given paediatricians have been identified as requiring greater support with adjusting to the ‘informed parent’, 4 , 10 this study addresses the uncertainty about the communication strategies used by sub‐specialty paediatricians. We aimed to investigate the experiences, attitudes and communication approaches of paediatric physicians, surgeons and anaesthetists (hereafter referred to as ‘paediatricians’) when interacting with parents accessing online information about their child's medical condition. Our research focus was paediatricians' communication approaches and their impact on the doctor–parent relationship, while including paediatricians' attitudes towards parents' information‐seeking behaviour, which may shape their communication approaches.

Methods

Given the paucity of literature available on the topic, we selected a qualitative approach to thoroughly explore paediatricians' perspectives. 18 The Sydney Children's Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR/17/SCHN/179) granted approval for the study.

Sample

A female qualitative researcher (CK) recruited participants between June and September 2017 at an Australian children's hospital. The study was undertaken with two other female investigators experienced in qualitative methodology, trained in biomedical and social science research methods (PC and KS).

CK emailed a study overview to Heads of Departments and, upon written approval via return email, paediatricians were invited to participate via a separate email. Through purposive sampling, we recruited a broad cross‐section of participants, selected according to ongoing analysis: first, we diversified the sample in terms of age, gender and years of clinical experience; then, in terms of paediatric sub‐specialty. Participant Information Statements and Consent Forms were issued via email and signed prior to data collection. Information regarding participants' sub‐speciality were obtained from the Hospital Intranet database. Age, gender and years of clinical experience were obtained through a brief demographic survey.

Interview guide

Guided by the research questions and literature, 1 , 4 , 8 we developed an interview guide with open‐ended questions. Questions included: paediatricians' experiences when interacting with Internet‐informed parents wanting to learn about their child's health, how they advised parents, paediatricians' perspectives about parents' reasons for searching, and the impact on the doctor–parent relationship.

Data collection

The interview guide was piloted on three participants, whose data were omitted. To elicit sufficient depth of responses, we asked introductory questions, followed by probing questions, which offered new insights to the study. 18

CK conducted semi‐structured interviews in private offices. The interviews lasted 30–70 min, averaging 45 min. Field notes were taken at each. CK had no previous relationship with participants. Investigators, KS and PC, were known to participants but were not involved in data collection.

Interviews continued until theoretical saturation was reached, when no new data was generated. 19 Interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were deidentified before analysis.

Data analysis

We used deductive and inductive thematic analysis, 20 where initial codes were derived from the research questions and literature. 19 Additional codes were derived from multiple readings of transcripts and line‐by‐line coding. Key phrases were identified and classified into broader concepts and categories, before being organised into a coding table, which formed the themes and subthemes of the data. Coding was performed by CK and KS, and reviewed by PC.

We undertook a rigorous approach to verify themes, 18 with analysis moving from open to focused coding and from descriptive to analytical codes. After CK and KS trialled the codebook through analysis of three interview transcripts, codes were removed (n = 1), added (n = 8) and collapsed (n = 3). Through routine meetings, the full range and depth of data were captured and classified, with full consensus achieved. To optimise credibility, the codebook was discussed for investigator triangulation. 18 In reporting findings, illustrative quotations are provided for sub‐themes, including participants' gender, age range and pseudonym, though not sub‐specialty to safeguard participant anonymity.

Results

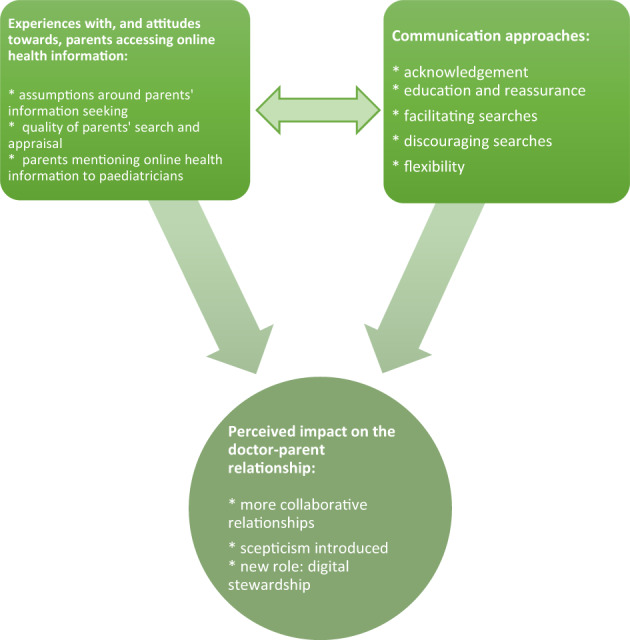

Interviews were conducted with 17 participants from 10 sub‐specialties. The sub‐specialties included: endocrinology, neonatology, rehabilitation medicine, urology, surgery, respiratory medicine, infectious diseases, sports and exercise medicine, oncology and anaesthesia. Participants had an age range of 25–66 years, median 45 years. Their range of years of clinical experience was 3–40 years, median 23 years. Nine were female and four were trainees. Of the trainees, two were fellows, one was a registrar, and one was a senior resident. The remaining 13 consultants had completed speciality training. Three themes were identified in the data: paediatricians' experiences and attitudes, communication approaches and perceived impact on the doctor–parent relationship. Illustrative quotations were selected (Table 1) and, through synthesising and interpreting the findings, the conceptual relationships between themes and sub‐themes were developed (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Illustrative quotations. Themes and subthemes are classified, and illustrative quotations represent each subtheme

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Experiences with, and attitudes towards, parents accessing online health information | |

| Assumptions around parents' information‐seeking | It'll be literally after they've called their mother after their kid has had a bad diagnosis. (M.†, Male, 60s) |

| Information is power. Information is sometimes comfort. (P., Male, 40s) | |

| They look but once they're confident that what we're saying is in fact reflective of trusted sites, they often stop doing it. (V., Male, 60s) | |

| Quality of parents' search and appraisal | The Internet opens up a bazillion possibilities which, in reality, don't exist. (L., Male, 50s) |

| Either you overemphasise, you catastrophise, think the worst, or you underestimate because you try to minimise, trivialise the severity of the problem. (J., Male, 50s) | |

| A parent can pitch up and they can know more than a consultant about the specific condition their child has had. (L., Male, 50s) | |

| Parents mentioning online health information to paediatricians | If you feel like you're not equal, then you're maybe less likely to bring it up. Sometimes they might not bring up minor issues if they don't want to bother us. (D., Female, 40s) |

| And still… friends or, or uncles or aunts or grandparents… will come out of the woodwork and suggest Chinese herbs. (V., Male, 60s) | |

| When they look online or find more information or queries, they usually come back to their friends, their third uncle twice removed, their holistic healer, their physiotherapist, their psychologist… and I often hear about it through the nursing staff. (E., Male, 40s) | |

| Some parents that just don't wanna be involved come with this information from the Internet and say, ‘Explain it to me’. There are others who come with this information and say, ‘Okay, I wanna understand and I wanna be part of the management – deciding what we're gonna try and what we're not gonna try’. (B., Female, 30s) | |

| Communication approaches | |

| Acknowledgement | I think the first thing is not dismissing it – that's the first thing ‐ no matter how wrong or inappropriate you believe their information is, I think you need to understand the reasoning behind it. (B., Female, 30s) |

| Sometimes people say, ‘I've read about this, this supplement or this’ and I've not heard of it… usually I say ‘Oh that's interesting, can I have a look?’ (S., Female, 50s) | |

| Education and reassurance | Increasingly becoming educators rather than just diagnostic technicians. (J., Male, 50s) |

| You want to be treated like an informed patient. (S., Female, 50s) | |

| Facilitating searches | There's so much stuff that parents hear and it goes in one ear and out the other…Factsheets can be really helpful so that they know what their condition's about, so they can make well‐informed decisions about treatment choices. (G., Female, 30s) |

| If the parent is interested in that and interested in the answers that come with it, then I think it's our job to guide them through it. (B., Female, 30s) | |

| Discouraging searches | You just tell them what's relevant to their child's treatment, because their child only has one type of Hurler syndrome and they're only gonna get one type of transplant. If you look in the literature, you'll find about 20 different ways of doing that transplant. But there's only one way we do it, so that's the only transplant that's relevant. (E., Male, 40s) |

| There's a lot of hokey‐garbage out there. Parents are convinced they've got Lyme's disease and they took their 12 years old to Germany to have hyperthermic therapy where they sort of cooked her at 32° and gave her lots of antibiotics, which just made her sick. (Z., Female, 60s) | |

| Flexibility | There's no one, specific way of reacting to that type of provision of medical information and questions. (P., Male, 40s) |

| It's important to give them those answers, even when the answer is, ‘I don't know’. (B., Female, 30s). | |

| On the disagreements that I've had, I've often just gone, ‘Yeah, sure, that's fine. No problem’, and, ‘We'll get on with it, we'll pay attention to that’, and we quietly do what we think is best. We may, somewhat unbeknownst to the parent, just get on with best‐practice after realising that this conversation is not going to go anywhere and if I dig my heels in as a practitioner and the parent digs their heels in about some fact that's not actually life or death, no one is going to get surgery. (E., Male, 40s) | |

| Perceived impact on the doctor–parent relationship | |

| More collaborative relationships | Each family and each child and each disease is different, so you can't just put a one‐size‐fits‐all plan. If you have the families part of that, then you can get an individualised plan with better outcomes, better rapport and better connection. (D., Female, 40s) |

| Things go much, much better when you explain things to the nth degree and you make yourself open to any question. (P., Male, 40s) | |

| Scepticism introduced | One case caused a lot of problems and it still wasn't resolved 6 months later because the parents were still contacting these overseas doctors and getting different advice. It caused a lot of trouble between the treating practitioners here and the family because the family ended up not believing things that we said because it was different to what the US was saying, but the trouble was the US doctors didn't have all of the facts. (D., Female, 40s) |

| New role: digital stewardship | A number of us have become more involved in the provision of online information. In the rare instance that you actually find something that's really wrong, people will write to the website owner. (P., Male, 40s) |

| There needs to be better advice and probably more often given to families. (D., Female, 40s) | |

| It's about communication and delivering information in bite‐sized chunks… like you talk about Twitter, it's 140 characters. (J., Male, 50s) |

A letter of the alphabet has been randomly assigned to each unique participant.

Fig. 1.

Thematic schema representing the interrelationships between paediatricians' experiences with Internet‐informed parents and their communication approaches, both of which impact the doctor–parent relationship. These factors affect the doctor–parent relationship when paediatricians interact with parents who access online health information.

Experiences with, and attitudes towards, parents accessing online health information

Assumptions around parents' information‐seeking

All participants acknowledged that parents searched online to learn about their child's symptoms prior to a consultation due to anxiety, or confirm information afterwards due to uncertainty. Participants reported that all parents searched using the general search engine, Google; few used databases like PubMed. Participants believed younger, educated, English‐speaking parents of higher socio‐economic status were more likely to find relevant information. They said parents with a child with a chronic illness were more likely to join support groups, blogs and social media to learn from the experiences of other parents in similar situations. Parents' information‐seeking included appraisal of paediatricians through ‘online doctor shopping’.

Quality of parents' search and appraisal

Participants expressed concerns that Google searches presented information in a biased manner. They reported it was time‐consuming to address misguided concerns of parents, triggered by poor eHealth literacy. Some reported that irrelevant or inaccurate online health information had resulted in detrimental decisions; for example, parents trialled experimental treatments that had not been proven to be effective or refrained from giving prescribed medications. Conversely, some parents found relevant information that enabled them to make more informed decisions and better understand their child's management.

Parents mentioning online health information to paediatricians

Participants believed parents were usually open with them about searching online, provided they trusted it would be received well. Sometimes participants needed to prompt parents to discuss their information source as it was ‘camouflaged’ in conversations. Sometimes parents asked Internet‐informed questions to a third party (e.g. nurse, social worker and family member) rather than their paediatrician. This complicated the child's management as these third parties did not have medical training or the child's full clinical picture. Some parents contacted doctors overseas who provided conflicting advice; parents subsequently questioned their child's management. Conversely, paediatricians reported pleasing occasions where parents printed online journal articles and asked their paediatrician to explain them.

Communication approaches

Acknowledgement

All participants reported refraining from dismissing parents' Internet‐informed questions. Instead, they attempted to understand parents' reasons for searching.

Education and reassurance

Participants reported first ascertaining the extent to which parents wanted to be involved in their child's care, then their level of understanding of the medical condition. Participants contextualised online health information for parents and aimed to educate and reassure them. They often used printouts of online information. A few used videos, diagrams, pictures and social media.

Facilitating searches

Most participants directed parents to accurate websites or factsheets. They mentioned practical difficulties of training parents to search online due to time limitations and some parents' poor eHealth literacy. However, very few participants reported training parents to search online databases independently.

Discouraging searches

A few participants in oncology and infectious diseases contextualised online health information without leaving room for dialogue and discouraged further searching. They used this ‘paternalistic approach’ to focus parents' education and protect parents from information overload. These participants believed that it was more difficult for parents to find relevant online information due to the increased complexity of medical conditions in these sub‐specialties.

Flexibility

Participants reported flexible approaches in two overlapping domains: (i) using varying degrees of transparency when communicating with parents and (ii) adjusting paediatric management plans to varying extents according to parents' wishes. Participants reported being frank when they did not know the answer to a question, particularly if the child had a rare condition. Sometimes parents requested changes to management plans based on online health information, which one participant agreed to but then dismissed because he believed it unnecessary – he did not inform the parents due to time constraints and his perception that his sub‐speciality was inaccessible to parents.

Two participants reported collaborating with international paediatricians whom the parents had contacted, though the outcomes were not helpful to patients. Despite not believing it was best, four participants reported altering management to meet parents' requests as they believed adherence to treatment was more likely if parents supported the management plan.

Perceived impact on the doctor–parent relationship

More collaborative relationships

A welcoming approach towards parents accessing online health information was thought to improve the paediatrician–parent relationship by making it more transparent and collaborative. Participants reported that shared decision‐making helped to create achievable management plans that improved adherence to treatment.

Scepticism introduced

At times the Internet was a competing source of information. Participants thought this reduced trust in them, particularly when parents questioned clinical decisions after searching.

New role: digital stewardship

Most paediatricians' communication approaches with Internet‐informed parents necessitated that they take on a new digital stewardship role. This involved navigating parents through online health information, reporting poor quality information and publishing good quality health information.

Despite increasing time constraints, participants wanted to improve their digital stewardship of parents and desired to develop more time‐efficient communication approaches. They desired more regular, fast yet comprehensive communications with parents, like ‘Twitter’, so they could continue to educate parents without compromising on other parts of their role. They believed paediatricians' opinions would continue to hold more weight than online health information.

Discussion

Although Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz deliberately excluded paediatricians from their study, 1 our study highlights that all of their communication approaches, except the physician‐centred resistant approach, may be transferable to the paediatric context. In contrast to the adult patient context, parents are the primary spokespeople and advocates for the patient in the paediatric context. Parents are often more anxious when decision‐making for their child, rather than for themselves, due to feeling a heightened sense of responsibility over their child and they may want to be more involved in their management. 8 Therefore, the paediatricians in this study most commonly reported using a patient‐centred communication approach when discussing online health information with parents. This study highlights the ways in which the doctor–parent relationship is evolving through paediatricians' communication approaches with Internet‐informed parents, such as improved balance in the doctor–parent relationship. 4 , 10

The paediatricians' expectations that most parents search online are consistent with recent findings in a paediatric tertiary hospital that almost 90% of parents searched online. 5 , 6 , 7 , 16 Paediatricians were concerned about parents' digital health literacy, in line with recent findings highlighting that parents focus more on relevancy (e.g. wording of website titles) than the credibility of online sources. 5 In contrast to Harvey et al.'s 6 Irish study and Kubb and Foran's 3 systematic review, where most parents chose not to discuss online health information with paediatricians, our Australian study indicated these discussions were quite common. Such variability may be due to cultural differences between Australia and Ireland, whereby Australian paediatricians experience less strain in working conditions and can prioritise patient education and autonomy. 21

Very few paediatricians in this study used a patient‐centred enhancing approach to train parents to search online independently. This approach involved little discussion about the content of online information in the context of a child's condition; rather, it focused on the logistics of how to search online. The physician‐centred repairing approach, involving discouraging searching, was also used by a few paediatricians in our study. These paediatricians believed discussions about online health information sometimes reduced the efficiency of clinical encounters. These attitudes were less commonly reported compared to a Brazilian study, in which 43.1% of physicians believed the Internet negatively impacted on the doctor–patient relationship. 11

Most paediatricians in this study viewed themselves as digital stewards and therefore used a coconstructive approach. They believed parental anxiety was the primary driver of searching, in accordance with Kubb and Foran, 3 and that it was their duty to allay anxiety through an open‐ended discussion. These paediatricians encouraged information‐seeking to facilitate a consensus regarding management. The benefits of shared decision‐making have been postulated in previous research, including increased adherence to treatment. 4 , 10 , 15 , 22

Paediatricians may opt for a coconstructive communication approach since they have grown accustomed to managing the delicate doctor–parent–child triangle. This approach was the only one that used the Internet as a means of strengthening the doctor–patient bond. Given it was predominantly used and no paediatrician used a resistant approach, it appears the doctor–parent–patient relationship may be stronger in the paediatric context than the doctor–patient relationships in previously studied adult contexts. 6 Physicians of adult patients are encouraged to become aware of patients' online information‐seeking, provide them with good‐quality websites, and encourage them to discuss their online research. 13

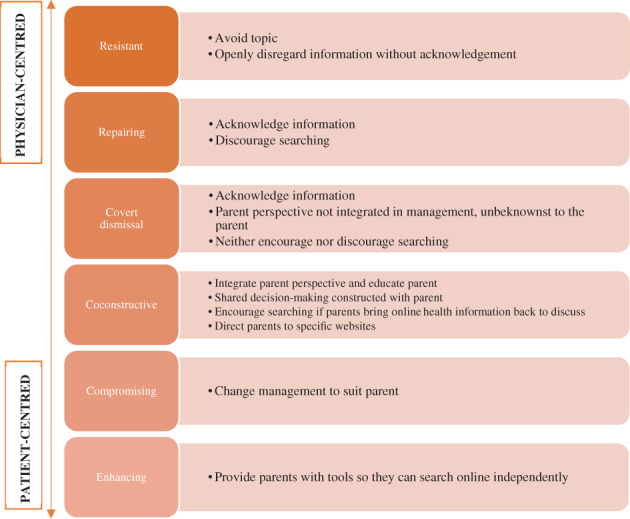

In this exploratory study, we identified two communication approaches in addition to the four reported by Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz. 1 First, a covert dismissal communication approach (Fig. 2) was demonstrated by a paediatrician who informed a parent he would modify the child's management as per the parent's Internet‐informed request. Unbeknownst to the parent, this paediatrician did not follow suit due to concern for the child's health and lack of time. This approach may put paediatricians' professionalism at risk if they do not fully disclose management plans. Perhaps the covert dismissal approach attempts to reduce the burden of paediatricians' increased workload. However, not correcting parents in the interest of time may impose a risk of harm if it perpetuates misinformation about the child's health.

Fig. 2.

Summary of paediatricians' approaches when communicating with Internet‐informed parents (adapted with permission from Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz 1 ). The resistant, repairing and covert dismissal approaches are physician‐centred. The resistant approach is the least patient‐centred. In contrast, the coconstructive, compromising and enhancing approaches are patient‐centred. The enhancing approach is the most patient‐centred.

Finally, a compromising communication approach (Fig. 2), employed by four paediatricians, involved changing a child's management to meet parents' requests, despite not believing it was best. These paediatricians explained this approach facilitated adherence and parents soon realised their choice was ineffective and wanted to revert to the paediatrician's initial plan.

Most paediatricians have taken on an additional digital stewardship role to help navigate parents through online sources and publish good quality information. While this new role aims to enhance patient advocacy, it increases paediatricians' responsibilities. Future research should consider how to delegate part of this digital stewardship role and utilise the skills of a medical informatics professional.

Paediatricians in our study reported more time‐efficient communication approaches are necessary due to heightening expectations. This reflects the United Kingdom's General Medical Council statement that doctors must go ‘above and beyond’ to ensure parents do not misinterpret online information. 23 Future research should assess whether enhancing parents' online health information search affects parental confidence and ability in managing children's health.

Shervington et al. 10 identified a need for educational development of paediatricians to help them adjust to the expectations of Internet‐informed parents. Our study provides a framework of communication approaches that build on Caiata‐Zufferey and Schulz' strategies and indicates that paediatricians could use one or a combination of approaches. We encourage personalisation of information for each family to achieve optimal communication and through this, the desired health outcomes.

Semi‐structured interviews were appropriate to understand paediatricians' attitudes; however, the data were self‐reported. The data were limited to paediatricians who were more available; nevertheless, purposive sampling enabled a heterogenous sample. Although data saturation was reached, the sample size was small and drawn from one Australian hospital, so findings may not be transferable to all specialties and other paediatric or cultural contexts. 18 We recommend follow‐up research across multiple sites with a diverse range of paediatricians and parents to further understand the challenges in discussing online health information. By doing so, we hope to better integrate good quality online health information into the care of paediatric patients and support for parents and carers.

Conclusions

Paediatricians view the Internet as an integral part of their interactions with parents. Unlike physicians interacting with adult patients, paediatricians mostly use a coconstructive communication approach when interacting with parents. Such a patient‐centred approach presents paediatricians with a new role of digital stewardship and expands their responsibilities. The issues surrounding paediatricians' increased time constraints must be addressed so they can continue to use communication approaches that engender a quality partnership with parents and facilitate parent education, given shared decision‐making is purported to foster better paediatric health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Grants: None.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions: Miss Ceylan Karatas conceptualised and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript, designed the data collection instruments, collected the data and carried out the analyses. A/Prof Patrina Caldwell conceptualised and designed the study, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, designed the data collection instruments and supervised the analyses. A/Prof Karen Scott conceptualised and designed the study, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, designed the data collection instruments, carried out the initial analyses and supervised the remainder of the analyses. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1. Caiata‐Zufferey M, Schulz PJ. Physicians' communicative strategies in interacting with internet‐informed patients: Results from a qualitative study. Health Commun. 2012; 27: 738–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hart A, Henwood F, Wyatt S. The role of the internet in patient‐practitioner relationships: Findings from a qualitative research study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2004; 6: e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kubb C, Foran HM. Online health information seeking by parents for their children: Systematic review and agenda for further research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020; 22: e19985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson A. Hippocrates and the smart phone: The evolving parent and doctor relationship. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2016; 52: 366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benedicta B, Caldwell PH, Scott KM. How parents use, search for and appraise online health information on their child's medical condition: A pilot study. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020; 56: 252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harvey S, Memon A, Khan R, Yasin F. Parent's use of the Internet in the search for healthcare information and subsequent impact on the doctor–patient relationship. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2017; 186: 821–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manganello JA, Falisi AL, Roberts KJ, Smith KC, McKenzie LB. Pediatric injury information seeking for mothers with young children: The role of health literacy and ehealth literacy. J. Commun. Healthc. 2016; 9: 223–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ben‐Sasson A. Parents' search for evidence‐based practice: A personal story. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2011; 47: 415–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haluza D, Naszay M, Stockinger A, Jungwirth D. Digital natives versus digital immigrants: Influence of online health information seeking on the doctor–patient relationship. Health Commun. 2017; 32: 1342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shervington L, Wimalasundera N, Delany C. Paediatric clinicians' experiences of parental online health information seeking: A qualitative study. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2019; 56: 710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oliveira JF. The effect of the Internet on the patient‐doctor relationship in a hospital in the city of São Paulo. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2014; 11: 327–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Armstrong‐Heimsoth A, Johnson ML, McCulley A, Basinger M, Maki K, Davison D. Good Googling: A consumer health literacy program empowering parents to find quality health information online. J. Consum. Health Internet 2017; 21: 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker SC, Watson BM. Investigating the association between Internet health information use and patient willingness to communicate with health care providers. Health Commun. 2019; 35: 716–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. AlGhamdi KM, Moussa NA. Internet use by the public to search for health‐related information. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012; 81: 363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wainstein BK, Sterling‐Levis K, Baker SA, Taitz J, Brydon M. Use of the Internet by parents of paediatric patients. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2006; 42: 528–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yardi S, Caldwell PH, Barnes EH, Scott KM. Determining parents' patterns of behaviour when searching for online information on their child's health. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018; 54: 1246–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wozney L, Radomski AD, Newton AS. The gobbledygook in online parent‐focused information about child and adolescent mental health. Health Commun. 2018; 33: 710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burns RB. Introduction to Research Methods, 3rd edn. Melbourne: Addison Wesley Longman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Humphries N, Crowe S, Brugha R. Failing to retain a new generation of doctors: Qualitative insights from a high‐income country. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020; 18: 75–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cegala DJ, Chisolm DJ, Nwomeh BC. A communication skills intervention for parents of pediatric surgery patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013; 93: 34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moberly T. High workload is putting doctors' professionalism at risk, says GMC. BMJ 2017; 356: j459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]