Abstract

Aims

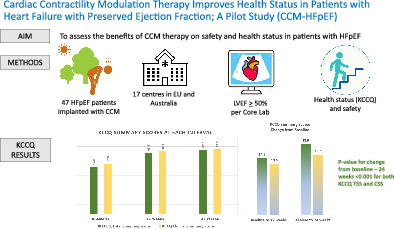

This pilot study aimed to assess the potential benefits of cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Methods and results

This was a prospective, multicentre, single‐arm, pilot study of CCM therapy in patients with HFpEF and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III. Echocardiographic parameters were measured by an echo core laboratory to determine study eligibility. After CCM device implantation, patients were followed for 24 weeks. Overall, 47 patients (mean age 74.3 ± 4.4 years, 70.2% female) were enrolled, with left ventricular ejection fraction of 59 ± 4.4%, 63.8% with hypertension, 46.8% with atrial fibrillation, 40.4% with diabetes, 31.9% with at least one heart failure hospitalization in the prior year, 61.7% in NYHA class III, and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score of 48.9 ± 21.7. The primary efficacy endpoint (mean change in the KCCQ overall summary score) improved by 18.0 ± 16.6 points (p < 0.001) and there was an event‐free rate of 93.6% for the primary safety endpoint (device‐ and procedure‐related complications), as adjudicated by an independent physician committee.

Conclusion

This pilot study demonstrates that the benefits of CCM may extend to the HFpEF patient population. The significant improvement in health status observed, with no obvious impact on safety, suggests that utilization of CCM for patients with HFpEF could prove to be promising.

Keywords: Heart failure, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Cardiac contractility modulation, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Health status, Device therapy

The study primary endpoint – Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score at baseline and 24‐week follow‐up and change from baseline. CCM, cardiac contractility modulation; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CSS, clinical summary score; TSS, total symptom score.

Introduction

Cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) therapy is a promising treatment for patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) 1 , 2 who are symptomatic despite receiving HF guideline‐directed medical therapy. 3 , 4 Whereas HFrEF (ejection fraction ≤40%) has established therapy, there has been less scientific evidence in HF with mildly reduced (HFmrEF) or preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

In previous CCM studies, an incremental treatment effect in peak oxygen uptake (VO2), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, health status, and 6‐min walk distance (6MWD) difference was observed in patients within the higher baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) range and was associated with reduced rates of HF hospitalizations raising the thought that CCM would also be beneficial in HFpEF. In addition, improvements in symptoms and calcium handling by CCM was also reported in a small case‐based pilot study 5 of HFpEF patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CCM in HFpEF in a pilot study.

Methods

Study population

This was a prospective, multicentre, single‐arm, pilot study of CCM in patients with HFpEF and NYHA class II or III symptoms despite receiving optimal medical therapy for the management of hypertension (including diuretic therapy as needed for volume overload), management of atrial fibrillation (AF), and other comorbidities. After signing informed consent, baseline testing and assessments were performed including a physical examination, NYHA functional class assessment, comprehensive echocardiogram based on the 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, 4 12‐lead electrocardiogram, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), and blood testing. Echocardiographic parameters were measured by an echo core laboratory to determine study eligibility, including LVEF ≥50%. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study protocol are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

CCM‐HFpEF study key eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

ECG, electrocardiogram; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; IABP, intra‐aortic balloon pump; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LVEDVi, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Optimal medical therapy for HF with preserved ejection fraction includes management of hypertension, diuretic therapy as needed for volume overload, management of atrial fibrillation, and other comorbidities.

The study conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, all locally appointed ethics committees approved the research protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study device

Eligible patients received the CCM therapy device, which includes a rechargeable implantable pulse generator that delivers non‐excitatory electrical impulses to the right ventricular septum via two active fixation pacing leads. Only experienced implanters performed CCM implantations. Patients are asked to recharge the battery using a transcutaneous inductive charger for approximately 1 h weekly, which confers 15 years of battery life to the system. The device is programmed to deliver CCM therapy signals for 71‐h periods spaced equally over each 24‐h day.

Study conduct

Patients returned for follow‐up visits 2, 12, and 24 weeks after the CCM therapy device implantation. At each visit, the patient's medical history since the prior visit was reviewed, and any occurrence of adverse events/hospitalizations were reported. All baseline assessments were repeated at 12 and 24 weeks, except for blood testing, which was only performed at the 24‐week follow‐up visits. It was recommended that patients remain on their baseline medical regimen throughout the study unless clinical circumstances dictated a change.

Study monitoring and oversight committees

The CCM‐HFpEF data were 100% source data verified by the study sponsor. An Events Adjudication Committee (EAC), comprised of three independent cardiologists experienced in the adjudication process, was established to review and classify all adverse events as attributable to the device or procedure or not, all hospitalizations as HF related or not, and all deaths as HF related or not. An independent Data And Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed aggregate safety data and monitored for the emergence of any significant safety concerns. The DSMB was comprised of individuals not otherwise affiliated with the study and included a statistician and two cardiologists with experience and expertise in providing oversight for clinical trials.

Statistical analyses

The primary efficacy endpoint was a mean change in health status as measured by the KCCQ overall summary score from baseline to 24 weeks following the CCM device implant. The KCCQ overall summary score reflects integrated information on physical limitations, symptoms, self‐efficacy, social interference and quality of life. The threshold for minimal clinically important difference established by Spertus in 2015 is 4.7 points and the study was designed to have a 90% power to detect a 12.5 point average improvement. 6 The secondary efficacy endpoints included the mean change from baseline to 24 weeks in echocardiographic parameters measured by the echo core lab (left atrial volume index [LAVi], septal E' velocity, septal E/E' ratio), N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and NYHA class. All secondary analyses and endpoints were considered exploratory.

All safety endpoint events reported through 168 days were reviewed and classified by the EAC. The primary safety endpoint included the number, rate, and type of device‐ or implant procedure‐related serious adverse events (SAEs). Device‐related events included those that the EAC deemed as having a possible, probable, or causal relationship with the CCM device. Procedure‐related events included those that the EAC deemed as having a possible, probable, or causal relationship with the CCM device implant procedure. For the primary safety endpoint, data on 50 patients provided 94% power to demonstrate that the percentage of event‐free patients is greater than 70% previously used in the FIX‐HF‐5C study based on a criterion from the Food and Drug Administration 7 given an observed event‐free rate of 80%, and 80% power to demonstrate that the percentage of event‐free patients is greater than 70% given an observed event‐free rate of 75%. Study enrolment was closed after 47 patients were enrolled due to the global COVID‐19 pandemic and the suspension of elective procedures at most centres.

The analysis for the primary efficacy endpoint is a paired t‐test. The mathematical form of the t‐test assumes that the data being tested are normally distributed. Changes in KCCQ scores are commensurate with the normality assumption of the t‐test, but a non‐parametric Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was also conducted in case the normality assumption did not hold. The primary efficacy endpoint was met because the (one‐sided) p‐value for improvement from baseline to 24 weeks is <0.025. The same test strategy was employed to analyse the secondary efficacy endpoints, some of which do not meet the normality assumption. Subgroup analyses (by AF) utilize a two‐sample t‐test. Patients missing a 24‐week value with an available 12‐week value had that last observation carried forward; this included one patient for KCCQ and NYHA class, and one patient for septal E/e′.

There were multiple secondary safety endpoints, including (i) all‐cause mortality, (ii) cardiovascular mortality, (iii) time to first cardiovascular‐related event (death or unplanned HF hospitalization), (iv) time to first all‐cause event (death or unplanned hospitalization), (v) number of readmissions to hospital due to HF symptoms or impairment, and (vi) all SAEs.

Results

A total of 134 patients consented to be screened for participation in the study; 47 met eligibility criteria and were implanted at 17 sites in Europe and Australia and completed the 24‐week follow‐up study. No patient was lost to follow‐up.

Patient characteristics and assessments

The mean age of the 47 enrolled patients was 74.3 ± 4.4 years, 70.2% were female and the primary HF aetiology was hypertension in 63.8%. The most common comorbidities included AF present in 46.8% and diabetes in 40.4%. Related to the severity of HF at baseline, 31.9% had at least one HF‐related hospitalization in the year prior to receiving the CCM implant, 61.7% were in NYHA class III and reported a low baseline KCCQ score indicating poor self‐reported health status. More than half of the patients (59.6%) were on oral anticoagulant therapy reflecting a history of AF. Details of the baseline characteristics, assessments, and medications are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics, assessments and medications

| Age (years) |

74.3 ± 4.4 (47) 64.0–81.0 |

| Female sex | 33/47 (70.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

30.6 ± 5.0 (47) 23.0–44.0 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

133.6 ± 16.8 (47) 76.0–160.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

76.4 ± 11.7 (47) 53.0–100.0 |

| Heart rate (bpm) |

68.3 ± 13.2 (47) 51.0–122.0 |

| LVEF (%) (core lab) |

59.0 ± 4.4 (47) 50.1–67.4 |

| Primary HF aetiology | |

| Ischaemic | 8/47 (17.0) |

| Idiopathic | 4/47 (8.5) |

| Hypertension | 30/47 (63.8) |

| Valvular | 1/47 (2.1) |

| HFpEF | 4/47 (8.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation a | |

| None | 25/47 (53.2) |

| Paroxysmal | 3/47 (6.4) |

| Persistent | 7/47 (14.9) |

| Long‐standing persistent | 12/47 (25.5) |

| NYHA class | |

| II | 18/47 (38.3) |

| III | 29/47 (61.7) |

| Concomitant device (pacemaker) | 4/47 (8.5) |

| At least one prior HF hospitalization | 15/47 (31.9) |

| Diabetes | 19/47 (40.4) |

| KCCQ overall summary score |

48.9 ± 21.7 (47) 15.4–95.3 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/ml) |

1254 ± 1591 (47) 230–8142 |

| Medications | |

| ACEi or ARB | 38/47 (80.9) |

| ACEi | 20/47 (42.6) |

| ARB | 18/47 (38.3) |

| Ivabradine (/channel/current inhibitor) | 1/47 (2.1) |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 24/47 (51.1) |

| Allopurinol | 11/47 (23.4) |

| Anti‐arrhythmic | 7/47 (14.9) |

| Anticoagulant | 28/47 (59.6) |

| Antiplatelet | 15/47 (31.9) |

| Beta‐blocker | 43/47 (91.5) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 13/47 (27.7) |

| Digoxin | 2/47 (4.3) |

| Diuretic b | 43/47 (91.5) |

| Hydralazine | 1/47 (2.1) |

| Nitrates | 3/47 (6.4) |

| Statin | 32/47 (68.1) |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (N) minimum − maximum, or n/N (%).

ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Atrial fibrillation detail: Paroxysmal = terminating spontaneously within 7 days; Persistent = continuous, >7 days; Long‐standing = persistent, continuous, >12 months.

The diuretics category includes loop and thiazide diuretics; 39/47 patients were on a loop diuretic (83%).

Primary efficacy endpoint results

There was a significant improvement in the KCCQ overall summary score from baseline to 24 weeks (18.0 ± 16.6 points) as shown in Table 3 . A similar improvement in KCCQ in patients with AF (19.3 ± 18.6) and without AF (16.9 ± 14.9) was observed (p = 0.617). Although not required as an endpoint for this study, the KCCQ clinical summary score also significantly improved in the overall group, with and without AF at 24 weeks (15.3 ± 19.4, 15.9 ± 24.5 and 14.9 ± 14.3) (Graphical Abstract).

Table 3.

Primary and additional efficacy endpoints: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire summary scores (with last observation carried forward)

| p‐values for baseline–24 weeks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Baseline | 12 weeks | Baseline–12 weeks | 24 weeks | Baselin–24 weeks | t‐test | Wilcoxon signed‐rank test | Normality test |

| KCCQ overall summary score | 48.9 ± 21.7 (47) | 63.6 ± 21.2 (46) |

14.5 ± 18.6 (46) (9.0–20.1) |

67.0 ± 21.1 (46) |

18.0 ± 16.6 (46) (13.1–22.9) |

<0.001 | <0.001 | 0.219 |

| KCCQ clinical summary score | 52.0 ± 21.9 (47) | 65.1 ± 21.5 (46) |

13.0 ± 19.8 (46) (7.1–18.8) |

67.5 ± 21.9 (46) |

15.3 ± 19.4 (46) (9.6–21.1) |

<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (N), and 95% confidence interval.

KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

Patients missing a 24‐week value with an available 12‐week value had that last observation carried forward for this analysis; this included one patient with KCCQ missing at 24 weeks.

Secondary efficacy endpoint results

Marginal improvements were seen in the mean change from baseline to 24 weeks in LAVi (−2.8 ± 8.2 ml/m2, p = 0.034) and septal E/e′ (−0.9 ± 4.7, p = 0.038) while septal e′ remained unchanged. NYHA class improved by an average of 0.5 ± 0.6 (Table 4 ). In contrast, the median NT‐proBNP at 24 weeks increased by 23.0 pg/ml from baseline (p = 0.077), which represents a marginally significant increase.

Table 4.

Secondary efficacy endpoints (with last observation carried forward)

| p‐values for baseline–24 weeks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Baseline | 24 weeks | Baseline–24 weeks | t‐test | Wilcoxon signed‐rank test | Normality test |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 48.2 ± 14.0 (47) | 45.9 ± 14.4 (44) |

−2.8 ± 8.2 (44) (−5.3 to −0.3) |

0.014 | 0.034 | 0.046 |

| Septal E/e′ | 15.3 ± 4.4 (47) | 14.5 ± 5.2 (42) |

−0.9 ± 4.7 (42) (−2.4 to 0.6) |

0.111 | 0.038 | 0.022 |

| Septal e′ | 5.7 ± 1.2 (47) | 5.6 ± 1.6 (43) |

−0.0 ± 1.5 (43) (−0.5 to 0.4) |

0.417 | 0.336 | 0.008 |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/ml) a | 702.0 (470–1005) (46) | 730.0 (394–1140) (42) |

23.0 (43) (−85.0 to −283.1) |

NA | 0.077 | NA |

| (230.0–6814) | (152.0–4720) | |||||

| (−2399 to 1710) | ||||||

| NYHA class | 2.6 ± 0.5 (47) | 2.2 ± 0.6 (46) |

−0.5 ± 0.6 (46) (−0.6 to −0.3) |

<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (N), and 95% confidence interval.

LAVi, left atrial volume index; NA, not available; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

One was an outlier and removed from this analysis. For NT‐proBNP we present median (interquartile range) and minimum − maximum values.

Primary safety endpoint analysis

There were no SAEs deemed as having a possible, probable, or causal relationship with the Optimizer device (device‐related complication) by the adjudication committee. There were three procedure‐related complications reported in three patients; two lead dislodgements and one worsening tricuspid regurgitation (TR). In this patient, TR was mild at CCM implantation. Following the implantation of the two leads, TR progressed to moderate with an accompanying increase in dyspnoea. Removal of the leads restituted TR to mild with concordant patient symptoms. An event‐free rate of 93.6% was observed (exact 95% confidence interval 82.5–98.7%). All SAEs in the 24‐week follow‐up period are captured in Table 5 .

Table 5.

All serious adverse events

| AE category and type | Implant–30 days (n = 47) | 31–168 days (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|

| General cardiopulmonary event – tricuspid regurgitation a | 1, 1 (2.1%) | 0, 0 (0.0%) |

| Localized infection | ||

| SARS‐CoV‐2 infection | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Upper respiratory | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Urinary tract | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Optimizer system AE – Optimizer lead dislodgement a | 1, 1 (2.1%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias – atrial fibrillation | 1, 1 (2.1%) | 3, 3 (6.4%) |

| Worsening heart failure | ||

| Dyspnoea | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Peripheral oedema | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 2, 1 (2.1%) |

| Unknown | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| General medical | ||

| Acute on chronic renal failure | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Carotid artery disease | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Hyponatraemia | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Hypotension | 1, 1 (2.1%) | 0, 0 (0.0%) |

| Left anterior tibialis rupture | 0, 0 (0.0%) | 1, 1 (2.1%) |

| Renal artery stenosis/renal failure/renal cell carcinoma | 1, 1 (2.1%) | 0, 0 (0.0%) |

Values are given as number of events, n (%) patients.

AE, adverse event; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Procedure‐related serious AEs.

Secondary safety endpoint analysis

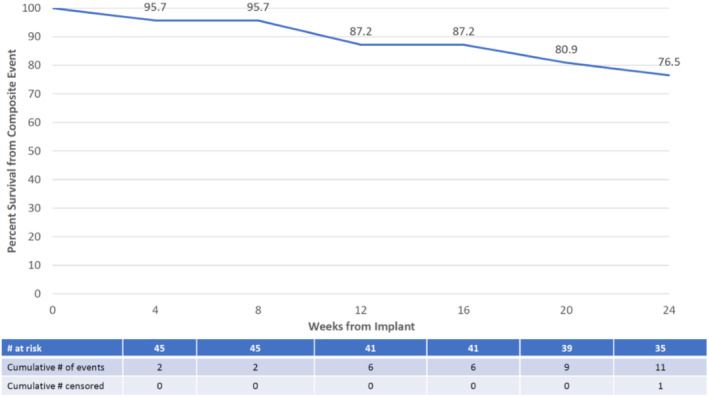

Regarding secondary safety events, there were no deaths reported in the study within the 24‐week follow‐up period (secondary endpoints #1 and #2). Time to first cardiovascular‐related event only included unplanned HF hospitalizations, with a total of two reported (secondary endpoint #3). Time to all‐cause event included a total of 12 patients with one or more unplanned hospitalizations (secondary endpoint #4) and is depicted in Figure 1 . There were four HF hospitalizations reported in two patients during the 24‐week study (secondary endpoint #5). A total of 20 SAEs were reported in 12 patients, as shown in Table 5 (exploratory endpoint #6).

Figure 1.

Time to first composite event of all‐cause death or unplanned all‐cause hospitalization.

Ad hoc analyses

Fewer patients required HF hospitalization in the 1‐year period after CCM therapy device implant compared to the prior 1‐year period. In the prior year, 15 of the 47 patients (32%) had at least one HF hospitalization. In the follow‐up period of 365 days (minimum 79 days, mean 345, median 365), five patients (11%) experienced at least one HF hospitalization. Although this was not a study endpoint, this represents a 67% reduction in the number of patients experiencing a HF hospitalization (p = 0.004 based on McNemar's test for agreement). 6 , 8

Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrate that CCM therapy may provide significant improvement in health status for patients with HFpEF while providing the same safety profile as previously seen in patients receiving CCM therapy with systolic dysfunction. The change noted of 18.0 point improvement in KCCQ from baseline to 24 weeks in the 47 patients was larger than expected, incremental over time and represents a 37% improvement from baseline. Moreover, NYHA class improved and a trend to lower need for HF‐related hospitalizations compared to the year prior to CCM implantation was noted.

The patients included in the present study are representative for HFpEF patients in previous studies. They were symptomatic with poor health status, almost 50% had a history of AF, more than 40% had diabetes, and were more commonly female and overweight as in many HFpEF studies. Moreover, symptom severity at baseline was indeed high with NYHA class III in more than 60% and with a low baseline KCCQ score of 48.9. Furthermore, 91.5% of patients were on a baseline diuretic for congestion. Reflecting their history of hypertension, the majority were on angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (80.9%). Aldosterone blockers (51.1%), and beta‐blockers (91.5%) were also widely used despite the absence of guideline direction for their use in HFpEF.

The magnitude of KCCQ improvement was larger than expected and much larger than 4.7 points, which has been judged to be clinically meaningful. 9 Since this was a pilot study, and thus had no control group, we designed the study to detect a much higher change – 12.5 points – in view of the potential placebo effect seen commonly with device therapy. 1 , 7 , 10 Indeed we cannot rule out that a proportion of the improvement was due to placebo as described by us in a controlled device study with crossover design and in controlled CCM studies. 10 But the magnitude of improvement suggests a treatment effect in addition to a placebo effect. Consequently, the primary endpoint was met and was sustained from 12 to 24 weeks. In addition, the KCCQ clinical summary score showed the same pattern. Importantly, there was no significant difference in KCCQ score improvements between patients in sinus rhythm at baseline and those in AF. Given that 50% of patients with HFpEF 11 can be expected to have AF, the comparable benefit seen in both groups has important implications for future use of CCM therapy in this population. Our results are of comparable magnitude to the results in patients with LVEF 25–45%, in the prior FIX‐HF‐5C trial using the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHFQ) to assess quality of life. 12

In addition, NYHA class improved by an average of 0.5 ± 0.6 units. These improvements were accompanied by a marginally significant reduction (p = 0.034) in LAVi and septal E/e′ (p = 0.034), whereas septal e′ and NT‐proBNP did not significantly change. It may be speculated that treatment time was not sufficient for complete structural changes to occur. Our findings may also indicate that the observed benefits of CCM were not mediated by clear improvements in structural and functional signs of diastolic function including filling pressures. In future studies this should be further studied. This pilot study should be viewed as hypothesis generating and interpreted as such.

Prior studies on CCM therapy have focused on patients with HFrEF or HFmrEF but excluded patients with ejection fraction >45%. In the pivotal FIX‐HF‐5 trial, peak VO2 analysis showed a greater treatment effect for patients with ejection fraction ≥25%. 13 The subsequent FIX‐HF‐5C trial further confirmed this finding as patients with ejection fraction 35–45% received twice the treatment effect in peak VO2 and over 20 m greater benefit in 6MWD than the entire cohort of patients with ejection fraction 25–45%. The CE Mark indication for CCM therapy is for subjects with symptomatic systolic HF in an LVEF group up to 50%. A registry study of 503 patients receiving CCM therapy showed that treatment effects in improvement of NYHA class, LVEF, and MLWHFQ score were similar when compared by LVEF subsets (≤25%, 26–34%, ≥35%). 2

The safety endpoint was met conclusively with the lower bound of 82.5%, far above the performance goal of 70%. With these data, there is an indication that the SAE‐free rate is likely above 80%. Nonetheless, one patient experienced worsening of TR from mild to moderate following implantation of the two right ventricular leads. This observed increment of TR in one patient is likely a side effect of the CCM implant, with its two leads traversing the valve. It indicates that careful echocardiographic assessment of tricuspid regurgitation before and after implantation is needed considering that placement of the two ventricular leads may be sufficient to worsen preexisting TR. In future studies, the effect of lead implantation on TR at the time of implant should be further examined.

Postulated mechanisms of action of cardiac contractility modulation therapy in the heart failure with preserved ejection fraction population

A recent evaluation of CCM therapy in human cardiac myocytes using human‐induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC‐CMs) described the effect of CCM on contractile properties, including contraction amplitude, contraction slope, and relaxation slope. Among the findings were faster contraction and relaxation kinetics, which were sustained for the duration of CCM stimulation. Early studies on CCM therapy in rabbit right ventricular papillary muscles were shown to induce a 69% improvement in negative peak dP/dT, as well as an increase in the rate of relaxation and the relaxation time measured from point of peak force to 50% decline in developed force. 14

A 2016 publication from Tschöpe et al. 5 provided results from two HFpEF patients treated with CCM therapy. Symptomatic, functional, and histological improvements were observed in both patients with 3 months of CCM therapy. Early benefits noted included improvement in 6MWD, NYHA classification, and quality of life scores. Objective benefits included a 10–20% improvement in ejection fraction with a significant reduction of the diastolic filling index (E/E′) and ejection fraction reserve, determined by repeated dobutamine stress echocardiography, through 6 months after CCM therapy initiation. Histologically, CCM therapy was associated with reduced cardiac fibrosis as evidenced by decreased collagen I and III protein expression. Titin, the major protein involved in dynamic recoil of the myocardium during diastole, showed increased phosphorylation at 30 min and 3 months of CCM therapy. CCM therapy was also shown to downregulate expression of the foetal gene product myosin 7 and to increase phosphorylation and expression of MLC2. Collectively, this resulted in improvement in diastolic filling index and increased stress echocardiography‐induced contractile reserve.

Prior studies on CCM have shown that phosphorylation of the protein phospholamban results in improved calcium reuptake to the sarcoplasmic reticulum via improved SERCA2a function. While the subsequent improvement in contractile function can be tied to increased cross‐bridging facilitated by increased calcium stores, improved SERCA2a function can also improve lusitropic function. 15

Systolic impairment may coexist with HFpEF despite preserved ejection fraction, with reductions in left ventricular global longitudinal strain and exercise left ventricular stroke index. 16 The augmentation of contractility provided by CCM therapy may therefore be attributed to improved functional capacity. Perhaps supporting this assertion, the MilHFPEF study demonstrated significant improvement versus placebo in KCCQ (+10 vs. −3 points, p = 0.046) and directionally improved 6MWD (+22 vs. −47 m) in patients treated with milrinone. 17 In this study, the investigators hypothesized that milrinone would enhance ventricular relaxation, but this was not demonstrated, leading to the conclusion that another mechanism (i.e. improved contractile reserve) could be the most plausible explanation.

While the current study serves as a meaningful initial step in establishing the benefits of CCM therapy for patients with HFpEF, a larger study is needed to conclusively make that determination. The randomized, quadruple‐blind, sham controlled, 1500 patient AIM HIGHer pivotal trial is underway (NCT05064709) and intends to validate the findings of the current study as well as to expand on the potential benefits of CCM on cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalizations.

Importantly, the safety profile of CCM therapy in the HFpEF population, which has until now never been studied, proved to be consistent with that established in the ejection fraction <50% population. There were only three device‐related complications reported in 47 patients. The lead dislodgement rate of 4% is less than or comparable to rates reported in prior studies. 18 Additionally, the DSMB found no signal toward significant device‐ or procedure‐related complications. The CCM therapy dosing schedule of 7 h per 24 h day proved to be well tolerated and uneventful.

Cardiovascular hospitalization rates and HF hospitalization rates in patients receiving CCM therapy was reduced by 62–80% in the European registry study, 2 and there was a 73% reduction in the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalizations in the FIX‐HF‐5C clinical trial. 7 In the present study, in the follow‐up period of 365 days, five patients (11%) experienced HF hospitalization, consistent with a 67% decrease in the number of patients experiencing a HF hospitalization (p = 0.004). Although this observation was not a pre‐specified endpoint, it suggests that CCM may be associated with HF hospitalization reduction with a magnitude of benefit in HFpEF patients that is comparable to what has previously been described in HFrEF patients.

The echocardiographic signals of improved diastolic function were not differentiated by presence or absence of AF. However, not all echocardiographic metrics indicated improved diastolic function. The small sample size and the heterogeneity of HFpEF phenotypes may have contributed to this result.

Study limitations

The current results are subject to the customary limitations of a pilot study: small sample size, single‐arm design with no control group, and hence a potential role of placebo effect for the primary endpoint. It should also be recognized that results are derived from complete analyses at 24 weeks, which do not account for patients lost to follow‐up or who have died. Similarly, effects of CCM on hospitalization rates were based on comparison of patients' historical rates rather than on a parallel control group. Limitations of this analysis are that it was not defined in the protocol, and the follow‐up times pre‐ and post‐CCM therapy device implant are unequal. However, similar findings were observed in prior randomized clinical trials and have also been used as the primary analysis for other studies of HF therapies.

The observed worsening of TR after CCM implantation in one patient could be a side effect of CCM therapy device implantation. It indicates that careful echocardiographic assessment of TR before and after implantation is needed considering that placement of the two ventricular leads may be sufficient to worsen preexisting TR. In future studies, the effect of lead implantation on TR at the time of implant should be further examined. In addition, the NT‐proBNP increase is a signal that requires careful monitoring in future studies. Finally, HF hospitalizations the year before and after CCM was not a study endpoint and some hospitalizations remain to been adjudicated.

Patients were enrolled into this study prior to the published results showing that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for the treatment of patients with HFpEF reduced the combined risk of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalization.

Conclusion

Until recently, HFpEF did not have established medical therapy. 19 , 20 Our pilot study results suggest that benefits of CCM may extend to the HFpEF patient population as a viable treatment option that can safely improve patients' health status. Further, CCM therapy appears to be safe and may have a positive effect on reduction of HF hospitalizations. Our results need to be corroborated in a randomized controlled clinical trial across a longer follow‐up period of time; the AIM HIGHer pivotal trial has recently been initiated to do just this.

Acknowledgements

Executive Steering Committee: Cecilia Linde, MD, PhD, Piotr Ponikowski, MD, PhD, and Carston Tschöpe, MD, PhD. Clinical Events Adjudication Committee: Andrew Coats, MD, PhD (chair), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, PhD and Jürgen Kuschyk, MD, PhD. Data Safety Monitoring Board: Gerd Hasenfuß, MD, PhD (chair), David Callans, MD, and Steven Ullery (biostatistician). Echocardiographic Core Laboratory: Bonnie Ky, MD, University of Pennsylvania Center for Quantitative Echocardiography.

Funding

The study was funded by Impulse Dynamics (USA), Inc., Marlton, NJ, USA.

Conflict of interest: C.L. reports receiving research support from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Royal Society of Science, Stockholm County Council, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Roche Diagnostics, speaker honoraria from Novartis, Astra, Bayer, Vifor and Medtronic, and Impulse Dynamics, served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, and had a leadership role on the executive steering committee for the CCM HFpEF study. M.G. received fees commensurate with the work completed as an Investigator in the CCM‐HFpEF study. P.P. has nothing to disclose. I.R. and A.S. are employed by Impulse Dynamics (USA), Inc. C.T. reports consulting fees from Impulse Dynamics and speaking fees from Novartis, Abiomed, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and had a leadership role on the executive steering committee for the CCM HFpEF study.

The institution(s) where work was performed

Andreas J. Rieth, MD and Heiko Burger, MD, Kerckhoff‐Klinik Forschungsgesellschaft mbH, Bad Nauheim, Germany

Bartosz Krakawiak, MD, Ph.D. and Dariusz Jagielski, MD, Ph.D., 4. Wojskowy Szpital Kliniczny z Poliklinika SP ZOZ, Wroclaw, Poland

Filippo Crea, MD, PhD and Francesco Perna, MD, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy

Petr Neuzil, MD, PhD and Pavel Hala, MD, Nemocnice Na Homolce, Prague, Czech Republic

Cecilia Linde, MD, Ph.D., Fredrik Gadler, MD, Ph.D. and Jonas Hörnsten, MD, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

Juan Francisco Delgado Jimenez, MD and Adolfo Fontenla Cerezuela, MD, Ph.D, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain

Michele Senni, MD and Paolo De Filippo, MD, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy

Adam Kolodziej, MD and Krzysztof Nowak, MD, Ph.D., Uniwersyteckim Szpitalem Klinicznym we Wroclaw, Poland

Marcin Grabowski, MD, Ph.D. and Lukasz Januszkiewicz, MD, Ph.D., Uniwersyteckie Centrum Kliniczne, Warsaw, Poland

Juan Gabriel Martinez Martinez, MD, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Spain

Elvis Teijeira Fernandez, MD, Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro / Complejo Universitario de Vigo, Spain

Javier Garcia Seara, MD, Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago, Spain

Giovanni Battista Perego, MD, Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, Italy

Roberto Antonicelli, MD, PhD, Lorenzo Pimpini, MD and Fabio Maria Gemelli, MD, IRCCS INRCA, Ancona, Italy

Maria Candida Fonseca, MD, Ph.D. and Dr. Pedro Carmo, MD, West Lisbon Hospital Center, Lisbon, Portugal

Hermann Wittmer, MBBCh, FRACP and David Di Fiore, MBBS, Ph.D., Friendly Society Private Hospital, Bundaberg, Australia

Peter Dias, MBChB, FRACP and Vincent Paul, MD, St. John of God Murdoch Hospital, Perth, Australia

Stefan Buchholz, MD and Vincent Paul, MD, St. John of God Bunbury Hospital, Bunbury, Australia

References

- 1. Borggrefe MM, Lawo T, Butter C, Schmidinger H, Lunati M, Pieske B, et al. Randomized, double‐blind study of non‐excitatory, cardiac contractility modulation electrical impulses for symptomatic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuschyk J, Falk P, Demming T, Marx O, Morley D, Rao I, et al. Long‐term clinical experience with cardiac contractility modulation therapy delivered by the Optimizer Smart system. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:776–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tschöpe C, Van Linthout S, Spillmann F, Klein O, Biewener S, Remppis A, et al. Cardiac contractility modulation signals improve exercise intolerance and maladaptive regulation of cardiac key proteins for systolic and diastolic function in HFpEF. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:1061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abraham WT, Kuck KH, Goldsmith RL, Lindenfeld J, Reddy VY, Carson PE, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cardiac contractility modulation. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:874–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spertus J, Jone P. Development and validation of a short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:469–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linde C, Gadler F, Kappenberger L, Rydén L. Placebo effect of pacemaker implantation in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PIC Study Group. Pacing In Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:903–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, et al.; EMPEROR‐Preserved Trial Investigators . Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1451–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Sandhu AT, Arnold SV. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care: JACC State‐of‐the‐Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Borggrefe M, Burkhoff D. Clinical effects of cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) as a treatment for chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:703–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brunckhorst CB, Shemer I, Mika Y, Ben‐Haim SA, Burkhoff D. Cardiac contractility modulation by non‐excitatory currents: studies in isolated cardiac muscle. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipskaia L, Chemaly ER, Hadri L, Lompre AM, Hajjar RJ. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kraigher‐Krainer E, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Santos A, Claggett B, Pieske B, et al.; PARAMOUNT Investigators . Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nanayakkara S, Byrne M, Mak V, Carter K, Dean E, Kaye DM. Extended‐release oral milrinone for the treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:4–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e895–e1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]