Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking is one of the leading causes of preventable death world wide. There is good evidence that brief interventions from health professionals can increase smoking cessation attempts. A number of trials have examined whether skills training for health professionals can lead them to have greater success in helping their patients who smoke.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of training health care professionals in the delivery of smoking cessation interventions to their patients, and to assess the additional effects of training characteristics such as intervention content, delivery method and intensity.

Search methods

The Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group’s Specialised Register, electronic databases and the bibliographies of identified studies were searched and raw data was requested from study authors where needed. Searches were updated in March 2012.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials in which the intervention was training of health care professionals in smoking cessation. Trials were considered if they reported outcomes for patient smoking at least six months after the intervention. Process outcomes needed to be reported, however trials that reported effects only on process outcomes and not smoking behaviour were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Information relating to the characteristics of each included study for interventions, participants, outcomes and methods were extracted by two independent reviewers. Studies were combined in a meta‐analysis where possible and reported in narrative synthesis in text and table.

Main results

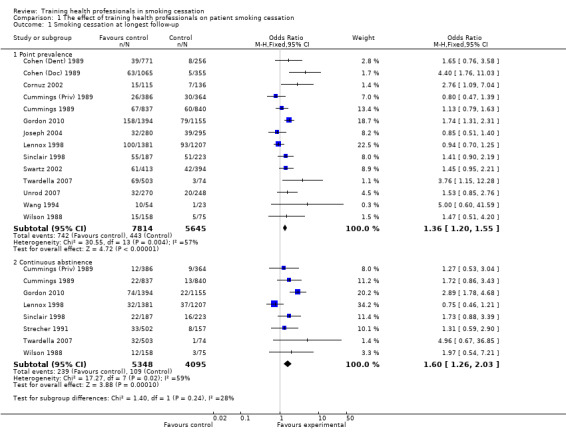

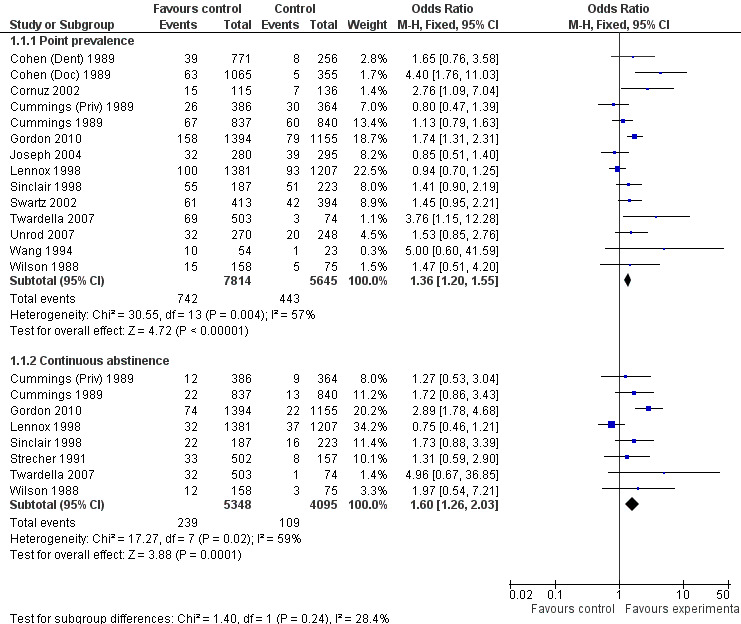

Of seventeen included studies, thirteen found no evidence of an effect for continuous smoking abstinence following the intervention. Meta‐analysis of 14 studies for point prevalence of smoking produced a statistically and clinically significant effect in favour of the intervention (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.55, p= 0.004). Meta‐analysis of eight studies that reported continuous abstinence was also statistically significant (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.03, p= 0.03).

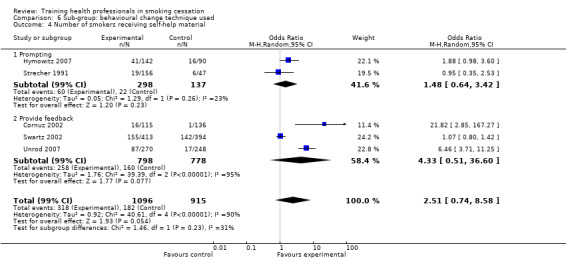

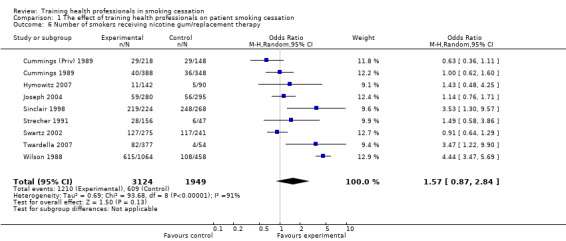

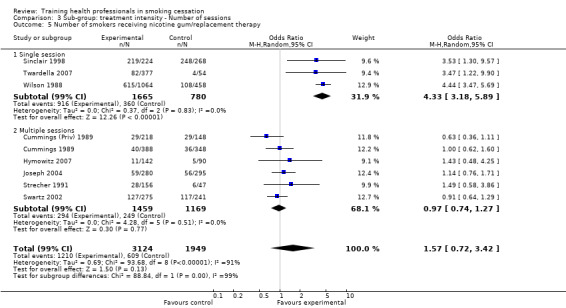

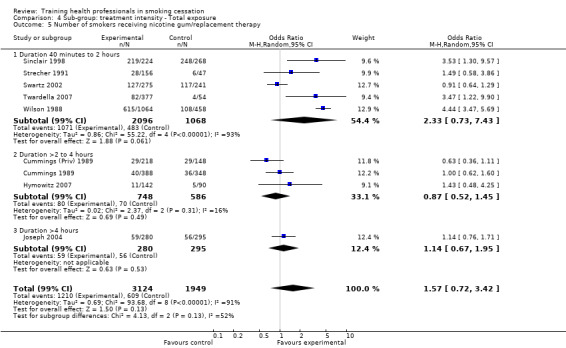

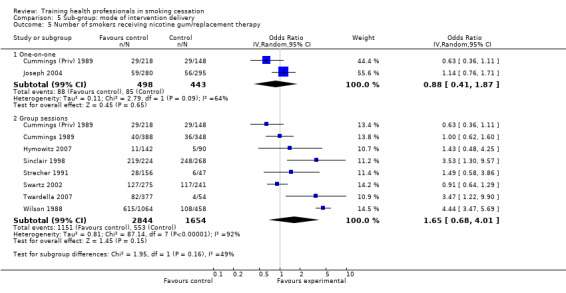

Healthcare professionals who had received training were more likely to perform tasks of smoking cessation than untrained controls, including: asking patients to set a quit date (p< 0.0001), make follow‐up appointments (p< 0.00001), counselling of smokers (p< 0.00001), provision of self‐help material (p< 0.0001) and prescription of a quit date (p< 0.00001). No evidence of an effect was observed for the provision of nicotine gum/replacement therapy.

Authors' conclusions

Training health professionals to provide smoking cessation interventions had a measurable effect on the point prevalence of smoking, continuous abstinence and professional performance. The one exception was the provision of nicotine gum or replacement therapy, which did not differ between groups.

Plain language summary

Can training health professionals to ask people if they smoke increase offers of advice and help patients quit?

Training programs are used to encourage health professionals to ask their patients if they smoke, and then offer advice to help them quit. The review of 17 trials found that these training programs help health professionals to identify smokers and increase the number of people who quit smoking. The programs also increase the number of people offered advice and support for quitting by health professionals.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Training health professionals for smoking cessation.

| Training health professionals for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Smokers treated by health professionals Intervention: Training | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Training health professionals | |||||

| Point prevalence of smoking cessation self‐report and some biologically validated Follow‐up: 6 to 14 months | 78 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (88 to 131) | OR 1.41 (1.13 to 1.77) | 13459 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | |

| Continuous smoking abstinence self‐report and some biologically validated Follow‐up: 6 to 14 months | 27 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (28 to 62) | OR 1.60 (1.26 to 2.03) | 9443 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 | |

| Number of smokers counselled self‐report Follow‐up: 6 to 48 months | 465 per 1000 | 664 per 1000 (578 to 739) | OR 2.28 (1.58 to 3.27) | 8531 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | |

| Patients asked to make a follow‐up appointment self‐report Follow‐up: 6 to 12 months | 166 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (233 to 593) | OR 3.34 (1.52 to 7.30) | 3114 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Number of smokers receiving self‐help material self‐report Follow‐up: 6 to 48 months | 134 per 1000 | 351 per 1000 (227 to 500) | OR 3.51 (1.90 to 6.47) | 4925 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy self‐report Follow‐up: 12 to 48 months | 312 per 1000 | 416 per 1000 (283 to 563) | OR 1.57 (0.87 to 2.84) | 5073 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unclear methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment in the majority of studies and all studies had inadequate blinding of participants 2 Wide confidence intervals around the estimate of effect 3 Significantly large amounts of heterogeneity were observed (I² >90%)

Background

Description of the condition

Every year approximately 5.4 million people die from tobacco‐related diseases, translating to 1 in every 10 deaths among adults world wide (Mathers 2006; WHO 2008). Approximately 80% of those deaths are from people living in less developed countries and by 2030 this figure will increase to more than 8 million per year if no action is taken (Mathers 2006). If current trends continue on this trajectory, an estimated 500 million people alive today will be killed by tobacco. In the 27 countries that form the European Union, over 25% of cancer deaths and 15% of all deaths can be attributed to smoking (European Commission 2004). Smoked tobacco is known to cause up to 90% of all lung cancers and is a significant risk factor for strokes and fatal heart attacks. In addition, tobacco use is linked to the development and treatment of many oral diseases (Bergstrom 2000; Balaji 2008; Petersen 2009) including oral cancer, delayed wound healing and peridentitis contributing to loss of teeth and edentulism (Tomar 2000; Mohammad 2006; Gordon 2009).

Description of the intervention

Health professionals are at the forefront of tobacco epidemics as they consult millions of people and can encourage them to quit smoking (WHO 2005; Zwar 2009). In developed countries, more than 80% of the population will see a primary care physician at least once a year, with doctors perceived to be influential sources of information on smoking cessation (Mullins 1999; Richmond 1999; Zwar 2009). It has been reported that most dentists and dental hygienists believe the lack of skills and training is a significant barrier to effectively providing tobacco cessation interventions into routine care (Gelskey 2002; Warnakulasuriya 2002; Gordon 2009; Rosseel 2009).

Providing training in smoking cessation care is one possible method for increasing the number and quality of delivered interventions by primary care health professionals, and a variety of training methods are available (Anderson 2004; Twardella 2004; Stead 2009). To date, individual studies have shown an effect of training on physician's activities, but there have been doubts about the extent to which this translates into changes in patient behaviour and actual smoking abstinence (Kottke 1989; Cummings 1989a; Cummings 1989b). Training health professionals to deliver smoking cessation messages has been known to increase the frequency with which interventions are offered to patients in the clinical context (Thorogood 2006).

How the intervention might work

Provision of advice and support to smokers by healthcare professionals in primary care settings has been shown to be the most cost‐effective preventive service and has a small but significant effect on cessation rates (Maciosek 2006; Solberg 2006; Stead 2008). Even though these rates appear low from the perspective of many clinicians, they could translate into a substantial public health benefit if consistently provided, as approximately 70‐80% of adults have contact with a health care practitioner, usually in primary care, at least once each year (Mullins 1999; Richmond 1999; Hung 2009; Zwar 2009). It is therefore disappointing that despite ongoing developments in this field worldwide, the number of patients who report receiving advice on smoking cessation from health professionals is still low (CDC 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

On a worldwide scale, tobacco use currently costs hundreds of billions of dollars each year (WHO 2008). Data on the global impact of tobacco is incomplete, however it is known to be high, with annual tobacco related health care costs being US$81 billion for the USA, US$7 billion for Germany and US$1 billion for Australia (Guindon 2008).

The first systematic review on this topic was published over a decade ago and showed that training health professionals to provide smoking cessation interventions had a positive effect on professional performance. However, there was no strong evidence that it changed smoking behavior of patients (Lancaster 2008). Since then, a number of new trials have examined whether specific skills training for health professionals leads them to overcome frequently mentioned barriers and to have greater success in helping their patients to quit smoking.

We therefore systematically identified and reviewed the evidence from new published randomized controlled trials that have studied the effects of training and supporting health care professionals in providing smoking cessation advice. Furthermore, we assessed the effects of training characteristics, such as the content, setting, and intensity.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the effectiveness of training health care professionals to deliver smoking cessation interventions to their patients, and to assess the effects of training characteristics (such as contents, setting, delivery and intensity).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered only randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

We considered trials in which the unit of randomization was a healthcare practitioner or practice, and that reported the effects on patients who were smokers.

Types of interventions

We considered interventions in which health care professionals were trained in methods to promote smoking cessation among their patients. To be included in the review studies had to have allocated healthcare professionals to at least two groups (including one which received some form of training) by a formal randomization process. Studies that used historical controls were excluded. We included studies that compared a trained group to an untrained control group, and studies that examined the effectiveness of adding prompts and reminders to training.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was abstinence from smoking six months or more after the start of the intervention, assessed as:

point prevalence (defined as not smoking at a set period (e.g., seven days) prior to the follow‐up), and

continuous abstinence (defined as not smoking for an extended/prolonged period at follow‐up)

The definition of point prevalence and continuous abstinence for each study can be found in the 'Outcomes' section of the Characteristics of included studies table.

The strictest available criteria to define abstinence were used. In studies where biochemical validation of cessation was available, only those participants who met the criteria for biochemically confirmed abstinence were regarded as being abstinent. Those lost to follow‐up were regarded as being continuing smokers.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary ‘patient level’ outcome measures included process variables such as the number of smokers who were:

asked to set a date for stopping (quit date)

given a follow‐up appointment

counselled

given self‐help materials

offered nicotine gum/replacement therapy

prescribed a quit date, and

cost effectiveness for interventions.

Secondary ‘physician level’ outcome measures include the number of referrals made (to local smoking cessation services).

To be included in the review, studies had to assess changes in the long term smoking behaviour of patients. Studies which only assessed the effect of training on the consultation process were excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified potentially relevant study reports from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register. This Register includes reports of trials and other evaluations of interventions for smoking cessation and prevention, based on regular highly sensitive searches of multiple electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CENTRAL, and handsearches of conference abstracts. For details of search strategies and dates see the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library. The most recent search of the Register was in March 2012. Records were identified from the Register as potentially relevant if they included the free text terms ‘training’ or ‘trained’ or the MeSH keywords ‘Education, Premedical’ or ‘Education, Professional’ or ‘Inservice Training’ or ‘Physician's Practice Patterns’ or ‘Dentist's Practice Patterns’ or ‘Delivery of Health Care’ or ‘Comprehensive Health Care’ or ‘Critical Pathways’ or ‘Disease Management’ or the EMBASE indexing terms ‘clinical education’ or ‘continuing education provider’ or ‘continuing education’ or ‘medical education’ as indexing terms. We conducted an additional search of MEDLINE (via OVID, to 2012 Feb week 5) exploding the same MeSH keywords in combination with the terms for smoking cessation and controlled trials used in the regular search of MEDLINE for the Specialised Register. See Appendix 1 for this strategy. Records included definite and probable reports of randomized trials, and reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (KC, MV) prescreened all study reports identified from the Specialised Register (limited to papers published after 1999 for this update). Articles were rejected if the title and/or abstract did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In instances where the study could not be categorically rejected, the full text was obtained and screened. Reference lists of screened articles were scanned for other potentially relevant articles.

Two reviewers then independently assessed the relevant studies for inclusion (KC and MV), with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Studies which were excluded though relevant to the review topic are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, with the reason for their exclusion described.

Data extraction and management

A combination of two reviewers independently extracted data from published reports (KC, MV, and MB). Disagreements were resolved by referral to a third party. No attempt was made to blind any of these reviewers to either the results of the primary studies or the intervention the subjects received.

The data extraction process identified information on the following design characteristics:

Country and setting of study

Description of training delivery method, duration, content

Number of therapists (intervention, control, post randomization dropouts)

Number of patient participants (intervention, control, losses to follow‐up in each condition), method of identification/enrolment

Number of patients per therapist (range and/or average)

Description of intervention and control conditions

Definition of abstinence for smoking cessation outcome(s), duration of follow‐up, method of biochemical validation if used

Secondary outcomes reported

Data was extracted and entered into Review Manager for the following outcome variables, where reported:

Point prevalence abstinence at longest follow‐up (preferred outcome for meta‐analysis is continuous or sustained abstinence)

Continuous or sustained smoking abstinence at longest follow‐up

Cost effectiveness analysis for intervention

We also extracted data on process outcomes where reported. These included patient reported or documented delivery of interventions, such as: setting a quit date, making a follow‐up appointment, number of smokers counselled, provision of self‐help materials, prescription of nicotine replacement therapy and/or prescription of a quit date.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers independently assessed the full text versions for of all included papers for risk of bias using the Cochrane Handbook guidelines, using a domain‐based evaluation (Higgins 2009). In addition, extra criteria developed by the Cochrane EPOC Group (EPOC 2009) were used to address potential sources of bias related to clustering effects. These domains included sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding for participants, blinding for outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, imbalance of outcome measures at baseline, comparability of intervention and control group characteristics at baseline, protection against contamination, selective recruitment of participants and any other sources of potential biases. The risk of bias was assessed for each domain as 'high risk', 'low risk', and 'unclear risk' (using the guidelines from Table 8.5.c of the Cochrane Handbook, Higgins 2009). Two of three reviewers (KC, MV or MB) independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by referring to a third party if disagreement persisted.

Unit of analysis issues

The trials included in the review used cluster randomization. Outcomes relate to individual patients whilst allocation to the intervention is by provider or practice, and ignoring this may introduce unit of analysis errors. Using statistical methods which assume for example that all patients’ chances of quitting are independent ignores the possible similarity between outcomes for patients seen by the same provider. This may underestimate standard errors and give misleadingly narrow confidence intervals, leading to the possibility of a type 1 error (Altman 1997). All trials were expected to be cluster randomized studies, with analysis performed at the level of individuals whilst accounting for the clustering in the data. This was performed by using a random effects model for pooled meta‐analysis as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Chapter 16.3.3, Higgins 2009) and checked by a statistician (AE). For those studies which did not adjust for clustering the actual sample size was replaced with the effective sample size (ESS), calculated using a rho= 0.02 as per Campbell 2000. Trials may use a variety of statistical methods to investigate or compensate for clustering; we have recorded whether studies used these and whether the significance of any effect was altered. In instances where the studies appeared homogenous via a combination of the statistical I² test in addition to homogeneity expressed in the visual inspection of a Funnel plot we meta‐analysed using a fixed effect model. However in the presence of significant heterogeneity (as defined below under ‘Data Synthesis’) the random effects model was used.

In the case of multi‐arm trials each pair‐wise comparison was included separately, but with shared intervention groups divided out approximately evenly among the comparators. However, if the intervention groups were deemed similar enough to be pooled, the groups were combined using appropriate formulas in the Cochrane Handbook (Table 7.7.a for continuous data and Chapter 16.5.4 for dichotomous data, Higgins 2009).

Dealing with missing data

Missing participant data were evaluated on an available case analysis basis as described in Chapter 16.2.2 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2009). Missing standard deviations were addressed by imputing data from the studies within the same meta‐analysis or from a different meta‐analysis as long as these use the same measurement scale, have the same degree of measurement error and the same time periods (between baseline and final value measurement, as per Chapter 16.1.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook, Higgins 2009). Where statistics essential for analysis were missing (e.g. group means and standard deviations for both groups are not reported) and could not be calculated from other data, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain data. Loss of participants that occurred prior to performance of baseline measurements was assumed to have no effect on the eventual outcome data of the study. Losses after the baseline measurement were taken were assessed and discussed. Studies that had more than 30% attrition (i.e., deaths and withdrawals) were reported in text only and excluded from the meta‐analysis.

We made an attempt to contact all authors for verification of methodological quality, classification of the intervention(s) and outcomes data. We attempted to contact the second author if we were unsuccessful in contacting the first author.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The review was expected to have some heterogeneity due to factors such as differing characteristics of clinics, practices and medical surgeries, differences in intervention characteristics and varying measurement tools used to assess outcomes. The Chi² and I² statistic (Higgins 2009) were used to quantify inconsistency across studies. The presence of significant heterogeneity was further explored through subgroup analyses. These were conducted for:

‘treatment type’ (e.g., counselling alone, counselling plus nicotine replacement therapy, counselling plus request for additional appointments, etc.)

‘treatment intensity’ (number of sessions)

‘treatment intensity’ (total exposure)

‘mode of delivery’ (e.g., face‐to‐face, group sessions or both)

‘behavioural change techniques’ (e.g., prompting, providing feedback, use of behavioural change theories)

‘type of professional being trained’ (e.g., dentist, doctor, health care worker etc.)

‘length of follow‐up’ (i.e., >6 to <9 months, >9 to <12 months, >12 to <24 months), and

‘risk of bias’ (i.e., high risk of bias for: < 2 domains, 3 – 5 domains, 6 – 8 domains or > 9 domains).

The likelihood of false positive results among subgroup analyses increase with the number of potential effect modifiers being investigated (Higgins 2009). As such we have adjusted these analyses using a Holm‐Bonferroni method (Holm 1979) using α= 0.05.

Assessment of reporting biases

With the inclusion of more than ten included studies, potential reporting biases were assessed using a funnel plot. Asymmetry in the plot could be attributed to publication bias, but may well be due to true heterogeneity, poor methodological design or artefact. Contour lines corresponding to perceived milestones of statistical significance (p= 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 etc.) were applied to funnel plots, which may help to differentiate between asymmetry due to publication bias from that due to other factors (Higgins 2009).

Data synthesis

1. For dichotomous outcomes the fixed effect model with an odds ratio (OR) was calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI), which was synthesised using inverse variance. However for outcomes with greater than 10 included studies a test for heterogeneity was conducted using a combination of two methods. If heterogeneity was found (defined as the I² test >60% and visual inspection of the funnel plot indicating no clustering of large or small studies) the random effects model was used in place of the fixed effect model, as suggested by the Cochrane Handbook (Section 9.5.2 and 9.5.3, Higgins 2009). Reasons for heterogeneity are further explored in the discussion. When studies appeared homogenous, the meta‐analysis was redone using the fixed effect model.

2. For continuous outcomes, a fixed effect model with a weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated as appropriate. However, in the presence of significant heterogeneity (as defined above) the random effects model was used in place of the fixed effect model.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on studies with an unclear or high risk of bias for sequence generation and/or allocation concealment.

We include the Tobacco Addiction Group glossary of tobacco‐specific terms (Appendix 2).

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

Of 381 articles screened, 17 studies met all of the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for PRISMA diagram). Detailed information relating to each included study is reported in the Characteristics of included studies table (for information relating to the 65 excluded studies see Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Design

All 17 included studies used a randomized controlled trial design with clustering and eleven studies also adopted nesting of participants within practices/hospitals (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cummings (Priv) 1989; Kottke 1989; Lennox 1998; Strecher 1991; Hymowitz 2007; Twardella 2007; Unrod 2007; Gordon 2010). One study (Twardella 2007) incorporated a 2x2 factorial design with randomization to: training plus incentive, training plus medication, training plus incentive and medication or usual care.

Sample sizes

In total 28,531 patients were assessed at baseline (following randomization) with 21,031 remaining in the studies at final follow‐up. Authors report a total of 1,434 individual health professionals recruited at baseline (across a known 260 practices) with follow‐up available for 1,204. Sample sizes for individual studies were medium to large, with the smallest number of patients (randomized at baseline) found in the Wang 1994 study (n= 93) and the largest in the Kottke 1989 study. The smallest sample at follow‐up remained with the Wang 1994 study (n= 82), and the largest remained with the Kottke 1989 study (n= 5266) . At the health professional level, the Hymowitz 2007 study had the largest number of residents randomized at baseline (n= 275) and follow‐up (n= 235) and likewise, Wang 1994 had the smallest number of residents at baseline and follow‐up (n= 27 for both). Seven studies also reported baseline cluster sizes at the practice level: Lennox 1998 (n= 16); Sinclair 1998 (n= 62); Swartz 2002 (n= 50); Joseph 2004 (n= 20); Hymowitz 2007 (n= 16); Twardella 2007 (n= 82); and Gordon 2010 (n= 14).

Setting

Eleven of the 17 studies were conducted in the USA, one in Canada (Wilson 1988), one in Taiwan (Wang 1994), one in Scotland (Sinclair 1998), one in the United Kingdom (Lennox 1998), one in Switzerland (Cornuz 2002) and one in Germany (Twardella 2007). Two studies were performed in a dentistry setting (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Gordon 2010), whilst the remaining 15 were conducted within primary care clinics, HMO (Health Maintenance Organisation) medical centres (Cummings 1989; Swartz 2002), VAMC's (Veterans Affairs Medicial Centres) (Joseph 2004) and one in a pharmacy setting (Sinclair 1998).

Participants

At the health professional level, two studies were performed with dentists (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Gordon 2010), six studies included only primary care physicians (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cummings (Priv) 1989; Kottke 1989Twardella 2007; Unrod 2007), two studies were conducted with residents (Cornuz 2002 and paediatric residents in Hymowitz 2007), three studies incorporated a combination of primary care physicians and internists (Cummings 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994), one study used pharmacists (Sinclair 1998), whilst the remaining three studies used a combination of health professionals including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, psychologists, pharmacists and other health visitors (Lennox 1998; Swartz 2002; Joseph 2004).

The individual patients in 16 of the 17 included studies were those visiting their health professional during the recruitment phase of each study. They were recruited during standard GP, dentist or outpatient visits, emergency department visits or from waiting rooms. The Hymowitz 2007 study was the only one to perform the training in a paediatric setting, targeting the parents/guardians of children visiting 16 primary care clinics.

Interventions

Treatment type

Six studies provided patients with a counselling plus nicotine replacement therapy intervention arm (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Sinclair 1998; Joseph 2004; Twardella 2007). The two Cohen et al studies had a second intervention arm of counselling plus a reminder for physicians to ask about smoking (chart prompt), and a third intervention arm combining the counselling, nicotine replacement therapy and chart prompt (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989). Another study (Twardella 2007) also had three intervention arms: counselling plus nicotine replacement therapy; counselling plus a monetary incentive to the physician following study completion per successful smoke‐free participant (€130); and a counselling plus nicotine replacement therapy plus incentive arm. The Wilson 1988 study had two intervention arms in addition to usual care: counselling and nicotine gum (as mentioned above) and a second arm of nicotine gum plus usual care (i.e., physicians were not trained in counselling). Three studies included multiple intervention methods to curtail smoking including counselling, nicotine replacement therapy, request for additional follow‐up appointments and provision of self‐help materials (Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989; Gordon 2010), whilst one study combined three of those four (counselling, nicotine replacement therapy, and self‐help materials, Cornuz 2002). Five studies used counselling alone (Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Lennox 1998; Swartz 2002; Unrod 2007) and two studies used counselling with the addition of self‐help materials (Kottke 1989; Hymowitz 2007).

Treatment intensity

The level of training intensity for health professionals ranged from one 40‐minute session in the Unrod 2007 study, to 'four or five' day long sessions in the Joseph 2004 study. Nine studies had a training session for one day or less: Wilson 1988 (four hours), Cohen (Dent) 1989 (one hour), Cohen (Doc) 1989 (one hour), Kottke 1989 (6 hours), Lennox 1998 (one day), Sinclair 1998 (two hours), Twardella 2007 (two hours), Unrod 2007 (40 minutes) and Gordon 2010 (three hours). Four studies had two separate sessions: Strecher 1991 (two, one hour sessions scheduled two weeks apart), Wang 1994 (two sessions of unknown duration), Cornuz 2002 (two, four hour training sessions scheduled two weeks apart) and Swartz 2002 (two, 20 minute training sessions and another session of unknown duration, where residents were able to practice counselling techniques with standardised patients). Four studies had three or more sessions: Cummings (Priv) 1989 and Cummings 1989 both had three, one hour sessions over a four to five week period, Hymowitz 2007 had four, one hour sessions, four times a year and Joseph 2004 had four to five, day long sessions within six months.

Mode of intervention delivery

Three different modes of intervention delivery were used being groups sessions, one‐on‐one or a combination of the two. Two studies only used one‐on‐one sessions (Joseph 2004; Unrod 2007), eleven studies delivered the intervention in a group setting only (Wilson 1988; Cummings 1989; Kottke 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Lennox 1998; Sinclair 1998; Swartz 2002; Hymowitz 2007; Twardella 2007; Gordon 2010) with an eighth study using group delivery as the primary mode, however doctors who were unable to attend received a private session in their office (Cummings (Priv) 1989). Finally three studies used both modes of intervention delivery (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cornuz 2002), with health professionals in the two Cohen et al studies provided the option of a group or individual session.

Theoretical model ‐ behavioural change technique

Nine studies used behavioural change theories to underpin the intervention techniques. These included the 'stages of change' (also known as the trans‐theoretical) model (Kottke 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Lennox 1998; Sinclair 1998; Cornuz 2002; Twardella 2007) and the '5A' (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange) approach (Unrod 2007; Gordon 2010). Three studies incorporated prompting or reminders to ask about tobacco use (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Hymowitz 2007) and four provided feedback to the health providers, for example number of patients counselled (Cornuz 2002; Swartz 2002; Joseph 2004; Unrod 2007).

Type of professional being trained:

Two studies only focused on dentists (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Gordon 2010), one focused on pharmacists (Sinclair 1998), and the remaining fourteen studies all involved doctors. Five of these fourteen studies included doctors still undergoing training, either residents (Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Cornuz 2002; Hymowitz 2007) or a combination of physicians and internists (Cummings 1989). Three other studies included training to other health care workers as well as doctors: Lennox 1998 also involved nurses and other health visitors; Swartz 2002 also trained nurse practitioners, physicians assistants and other health professionals; and, in addition to doctors, Joseph 2004 included nurses, psychologists and pharmacists.

Length of follow‐up

Eight studies reported follow‐up periods between six and nine‐months post intervention (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Lennox 1998; Sinclair 1998; Unrod 2007; Gordon 2010), eleven studies presented 12 month follow‐up data (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cummings 1989; Kottke 1989; Wang 1994; Cornuz 2002; Swartz 2002; Joseph 2004; Twardella 2007; Gordon 2010) and two studies assessed extended follow‐up periods of 14 months (Lennox 1998) and four years (Hymowitz 2007). However, only two‐year post intervention data was available for Hymowitz 2007 at the time of writing.

Outcomes

Smoking abstinence was assessed in all included studies through self‐report of either continuous abstinence (no smoking for an extended period of time) or point prevalence (for example, no smoking for seven days prior to the time of outcome collection). Of the eight studies that reported continuous abstinence, six (Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989; Gordon 2010; Lennox 1998; Sinclair 1998; Wilson 1988) also reported a point prevalence measure of abstinence. Ten of the included studies used biochemical validation through either exhaled carbon monoxide (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Strecher 1991; Cornuz 2002), serum cotinine (Kottke 1989; Twardella 2007), saliva cotinine (Wilson 1988; Unrod 2007) or a combination of exhaled carbon monoxide and serum cotinine (Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989). A number of secondary outcomes measures were reported by some studies including: patients asked to set a quit date; patients asked to make a follow‐up appointment; number of smokers counselled; number of smokers receiving self‐help material; number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy; and number of smokers prescribed a quit date.

Two studies reported n‐values as a total across both intervention and control arms (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989) and six studies reported n‐values as percentages, which had to be transformed into whole numbers (Wilson 1988; Cornuz 2002; Swartz 2002; Joseph 2004; Hymowitz 2007; Unrod 2007). As such there is likely to be some small variance between actual n‐values and those reported in these analyses, but this is not significant. Seven studies had multiple intervention arms, which were considered similar enough to be pooled together, two in the Wilson 1988, Kottke 1989 and Wang 1994 studies and three intervention arms in the Cohen (Dent) 1989, Cohen (Doc) 1989, Strecher 1991 and Twardella 2007 studies. One study did not report the n‐value for subjects at randomization, and hence this was calculated based on the number eligible for study and the number at follow‐up (Strecher 1991). The Kottke 1989 study reported all outcome data as continuous variables, as such it was unable to be pooled in the meta‐analyses. Smoking related outcomes in the Hymowitz 2007 study were unable to be pooled as only change scores from baseline were presented.

Excluded studies

Sixty‐five studies (71 articles) were excluded for the following reasons: 21 included consultation process only, 18 did not include a control group, 13 failed to measure smoking related outcome data, 12 were considered to be inadequately randomized and one only reported on smokeless tobacco use. See the Characteristics of excluded studies table for more detailed information relating to each excluded study.

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological details for the 17 included studies are provided in the 'risk of bias table' at the end of the Characteristics of included studies tables. Key methodological features are also summarised in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias judgement presented as percentages across all included studies

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Five studies reported adequate methods of sequence generation (Cummings 1989; Cornuz 2002; Hymowitz 2007; Twardella 2007; Unrod 2007), two had inadequate methods (Kottke 1989; Strecher 1991) whilst the remaining ten did not provide enough information to assess risk of bias for sequence generation and were hence judged to be at unclear risk in this category. Adequate methods included the use of a random number generator or coin toss, whilst unclear methods were described as being 'random' in design, however methods were not described. The Kottke 1989 study required some physicians to be re‐assigned due to inappropriate allocation methods during assignment. For the Strecher 1991 study appropriate randomization did not occur as residents were randomly assigned by clinic half‐day session to one of four groups, which risks introducing bias. All 17 trials used cluster randomization, with five studies inadequately accounting for potential clustering effects in the data, requiring manual clustering adjustments (Wilson 1988; Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989; Kottke 1989; Wang 1994). Only two studies (Kottke 1989; Hymowitz 2007) reported outcome data at the level of randomization. No authors reported that differences in the method of analysis affected the results.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Allocation concealment was unclear in all 17 included studies as authors did not describe methods of allocation concealment. Authors of the Lennox 1998 study report that physicians were randomly and blindly allocated to control or intervention groups, however the methods were not described. Another study mentioned that an independent research assistant concealed the result of randomization until two weeks before the intervention, when residents were provided with details about training sessions, however, methods of concealment were again not reported (Cornuz 2002).

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) of participants

Only one study reported adequately blinding participants to the intervention (Cornuz 2002), as residents were not informed about the aim of the trial and were advised only that a survey on cardiovascular risk factors and prevention would be conducted. Authors announced that a training program in clinical prevention that included sessions on smoking cessation and management of dyslipidaemia was being conducted. Authors also report that patients were blinded to the aim of the study and group allocation of their physician. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants was not possible for the remaining 16 studies. An attempt was made to blind physicians in the Unrod 2007 study, with physicians learning their group assignment only after signing the informed consent, however they were not blinded during the study intervention period and follow‐up.

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) of outcome assessors

Three studies reported methods blinding of outcome assessors that we judged at low risk of bias. Authors of Cummings (Priv) 1989 stated that 'outcome assessors were blinded', authors of the Joseph 2004 study report interviewers collecting patient outcomes were blinded to subject treatment status and authors in the Strecher 1991 study report that telephone interviewers, who were blinded to residents’ and patients’ group assignments, obtained the patient reports. The remaining 14 studies did not report any attempts to blind outcome assessors and as such are unclear for this category.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Incomplete outcome data was adequately addressed in three studies (Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989; Gordon 2010) and unclear in the remaining 14 studies. The Cummings (Priv) 1989 and Cummings 1989 studies reported that missing data was accounted for in analyses, whilst the Gordon 2010 study reported the use of multiple imputation procedures to account for missing data with participants lost to attrition discussed in the text. All unclear studies failed to mention if there was any missing outcome data and if so, how this was addressed when reporting results.

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Selective reporting was evident in three studies (Hymowitz 2007; Unrod 2007; Gordon 2010), unclear in three studies (Kottke 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994) and not detected in the remaining 11. Although all pre‐specified outcomes were addressed in the four year follow‐up for the Hymowitz 2007 study, the authors mention that outcome data for year one was omitted in order to provide a 'cleaner look' at the progress of the data. In the Unrod 2007 study, smoking abstinence from baseline to follow‐up (an outcome that would be expected to have been assessed in this study) was not reported. The Gordon 2010 authors report that secondary participant outcomes were examined with no significant differences on any variables, and that therefore they were not presented in the publication. Also, receipt of intervention was reported in text as percentages, however no information regarding this outcome was reported for the control.

Imbalance of outcome measures at baseline

One study did not report data for baseline smoking and made no mention of statistical analyses to potentially adjust for any imbalances (Wang 1994), as such the risk of bias category was assessed as unclear. All remaining studies adequately addressed imbalances of outcome measures at baseline. Thirteen studies accounted for baseline imbalances through analysis of covariance, regression analyses or other analysis techniques, whilst three studies reported outcomes at baseline to be similar across groups and as such did not require adjustment (Cummings (Priv) 1989; Lennox 1998; Sinclair 1998).

Comparability of intervention and control group characteristics at baseline

Five studies had unclear comparability between intervention and control groups at baseline (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cummings 1989; Twardella 2007) and the remaining twelve studies adequately addressed any differences found between groups via appropriate analysis methods.

Protection against contamination

Two studies reported contamination. In Gordon 2010, authors reported contamination due to a tax increase on cigarettes in New York, which resulted in a drop in smoking prevalence from 18.4% in 2006 to 15.8% in 2008. Authors believed that this tax increase contributed to the unusually high rate of smoking cessation in the usual care patients, thereby affecting the relative impact of the intervention. Authors of the second study, Strecher 1991, mention that "all four groups worked closely with one another at each site", leading to the possibility of contamination, however they also state that “...the effects appeared to be slight.” Nine studies had unclear risk of bias for contamination with insufficient information to permit a judgement of yes or no, whilst the remaining six studies (Wilson 1988; Cummings (Priv) 1989; Cummings 1989; Kottke 1989; Lennox 1998; Cornuz 2002) reported no potential contamination during the study period.

Selective recruitment of participants

Although no studies were identified as having selectively recruited participants, this could not be completely ruled out for eleven studies, which were determined to have an unclear risk of bias for this outcome (Wilson 1988; Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cummings (Priv) 1989; Kottke 1989; Strecher 1991; Wang 1994; Sinclair 1998; Swartz 2002; Twardella 2007; Gordon 2010). The sampling frames in these studies were unclear and as such, generalisability is of a potential concern. The remaining six studies adequately reported recruitment methods and were determined as having a low risk of bias.

Other bias

No other biases were identified for the 17 included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Intervention effectiveness was assessed in all seventeen included studies through smoking prevalence, as well as through multiple secondary outcomes (see Table 1). All data were analysed as per the pre‐defined methodology outlined in the Methods section. For a summary of intervention effectiveness for each of these outcomes see Table 2.

1. Summary of individual study outcomes.

| Study ID/sub‐headings: | Detailed synthesis of intervention effectiveness: |

|

Cohen (Dent) 1989 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: At 12 month follow‐up there was a significant interaction between subjects receiving the gum compared to control (7.7% and 3.1% for gum and control groups respectively, p< 0.05). When the three intervention groups were combined together as per the methods outlined in this review, point prevalence of smoking at 12 month follow‐up was 5.1%, compared to the control of 3.1%, which failed to reach statistical significance. Six months follow‐up: At 6 month follow‐up the coefficient for the reminder effect was negative, which authors state is likely to be caused by high cessation in the gum group coupled with the lower percentages in the gum and reminders group (9% for gum only, 3.2% for reminder only, 3% for gum and reminder and 3.1% for control). |

| Cohen (Dent) 1989 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Prompted dentists were more likely to ask patients to set a quit date (6% for gum only, 14% for reminder only, 31% for both reminder and gum and 3% for control) Number of smokers counselled: Prompted conditions increased the likelihood of dentists advising their patients to quit (72% for gum only, 59% for reminder only, 85% for both reminder and gum and 37% for controls) |

|

Cohen (Doc) 1989 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: The combination of gum and reminders did not increase the percent of patients who quit smoking compared to either condition alone. At 1 year follow‐up significant negative interaction between gum and reminders were found (p< 0.05). Pair‐wise comparisons among the groups showed that the three intervention groups were not significantly different from each other (reminder 15%, gum 8.8%, both 9.6%), however, each of them were significantly different from the control for analyses based on returnees and on all patients (control 2.7%, p< 0.05). Twelve month quit percentages for point prevalence were significantly higher for the reminders group (7.9%), compared to those using gum (4.7%), those using a combination of the two (5.2%) and control (1.5%), p< 0.05. When the three intervention groups were combined together as per the methods outlined in this review, point prevalence of smoking at 12 months follow‐up was 5.9%, compared to the control of 1.5%, which statistically favoured the intervention, p= 0.002. |

| Cohen (Doc) 1989 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Prompted doctors were more likely to ask patients to set a quit date (10% for gum only, 33% for reminder only, 58% for both reminder and gum and 2% for control) Number of smokers counselled: Both the gum and prompted conditions increased the likelihood of doctors advising patients to quit (84% for gum only, 75% for reminder only, 95% for both reminder and gum and 41% for control) |

|

Cornuz 2002 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: At 12 month follow‐up, 7 day point prevalence was significantly higher in the intervention group (15 of 115 patients [13%, 95% CI 7% to 12%]) compared to the control group (7 of 136 patients [5%, 95% CI 1% to 9%]). The eight‐percentage point difference between groups translates to a resident needing to counsel 13 patients to gain 1 additional former smoker. |

| Cornuz 2002 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: The short‐term effect of the training program performed by the resident was statistically significant in favour of the intervention with 8% compared to 2% for the intervention and control groups respectively Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Short‐term effect was not significantly different between groups with 7% of the intervention and 3% of the control population asked by their physician to make a follow‐up appointment Number of smokers counselled: Not statistically significant with 39% of intervention patients and 29% of control patients counselled not to smoke Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Short‐term effects were statistically significant between groups with 14% of intervention subjects provided with a brochure compared to 1% of control |

|

Cummings (Priv) 1989 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: There was no statistical significance on 7 day point prevalence for validated smoking cessation at one year follow‐up, with 6.7% for trained group patients quit compared to 8.2% for control. Biochemically validated continuous abstinence (defined as > 9 months abstinence) results were similar with 3.2% for intervention subjects and 2.5% for control (95% CI for the 0.7% difference= ‐1.7 to +3.1%) |

| Cummings (Priv) 1989 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Physicians in the experimental group asked more smokers to set quit dates with 100 out of 261 for intervention and 22 out of 177 for control Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Trained physicians were significantly more likely to arrange a follow‐up appointment to discuss smoking with 50 out of 261 for the intervention and 19 out of 177 for control Number of smokers counselled: Trained physicians were significantly more likely to discuss smoking (64%) compared to the control (44%) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Physicians in the experimental group gave self‐help booklets to more smokers with 151 out of 411 for intervention compared to 38 out of 407 for control Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: There was no significant difference in the prescription of nicotine gum; Control group patients with whom smoking was discussed were more likely to be prescribed it (19%) than the trained group (13%) |

|

Cummings 1989 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: There was no significant effect on validated abstinence at one year follow‐up, with 8.0% of trained group patients quitting versus 7.1% of control. |

| Cummings 1989 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Trained physicians were significantly more likely to ask patients to set a quit date with 37.6% of intervention subjects and 11.1% of control subjects asked Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Significantly more subjects in the intervention group had a follow‐up appointment arranged with 15.2% compared to 5% in the control population Number of smokers counselled: Trained and control physicians were similar in terms of asking patients to discuss smoking (50.1% vs 44.9% respectively) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Physicians in the intervention arm were more likely to provide patients with self‐help materials with 24.9% compared to control physicians with 8.4% Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: There was no significant difference in the prescription of nicotine gum; Approximately 10% of patients with whom smoking was discussed were prescribed gum Number of smokers prescribed a quit date: Trained physicians were significantly more likely to prescribe patients with a quit date (16.1%) compared to control physicians (1.2%) |

|

Gordon 2010 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Six months follow‐up: Significantly higher abstinence levels were reported for both continuous abstinence and point prevalence at 7.5 month (six months post‐enrolment plus six week grace period) follow‐up (continuous abstinence: 74 out of 1394 for intervention and 22 out of 1155 control, p< 0.01; Point prevalence: 158 out of 1394 for intervention and 79 out of 1155 for control, p< 0.05) |

| Gordon 2010 Secondary outcomes |

No secondary outcomes reported across both groups, however two outcomes reported for intervention group only: Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Among intervention patients, 66.5% reported receiving the self‐help reading materials and 96.7% reported reading them Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Of the intervention subjects 16.9% reported using nicotine replacement therapy |

|

Hymowitz 2007 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: There was an increase in the special training condition of reported quitting during the past year of 3.8% (an 8.5% increase over baseline levels), however the change from baseline failed to achieve statistical significance. Among parents associated with standard training, the change was only 0.8%. |

| Hymowitz 2007 Secondary outcomes |

Number of smokers counselled: There was a significant increase in the percentage of parents counselled at both intervention and control training sites from baseline, however absolute levels of this activity for residents in each conditions was low (intervention 21.4% (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.87), control 16.7% (OR 1.84, 95% CI 0.84 to 4.02)). There was no significant difference between groups. Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Provision of cessation materials increased significantly across both groups over the four year period when compared to baseline values (intervention 28.8% (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.10 to 3.46), control 17.6% (OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.76 to 4.08)). There was no significant difference between groups. Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Few parents in either condition reported that residents prescribed nicotine replacement therapy (intervention n= 7.6%, control n= 5.9%) |

|

Joseph 2004 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: At follow‐up the point prevalence of smoking cessation did not significantly improve for the intervention subjects, over that of control (intervention 11.4%, control 13.2% (p= 0.51 for Pearson Chi² test)). |

| Joseph 2004 Secondary outcomes |

Number of smokers counselled: During the intervention period, 59% of subjects in the intervention arm received behavioural support to stop smoking in comparison to 55% in the control (p= NS) Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Twenty‐one percent of subjects reported receiving medications for smoking cessation in the intervention arm whilst 19% received medication in the control group (p= NS) |

|

Kottke 1989 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: Almost half of the participants in each group who were smoking at baseline reported quit attempts for at least 24 hours during the previous year, with a mean duration of cessation of 2‐months. No differences between the three groups were identified. |

| Kottke 1989 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Almost 20% of patients seen in the workshop group reported being asked to set a quit date, compared to 10% in the materials group and 5% in the no‐assistance group (p< 0.005) Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Greater proportions of patients in the workshop group were asked to make a follow‐up appointment compared to the other two groups but this was not significant Number of smokers counselled: Slightly over half of the patients interviewed reported that they had been ‘asked if they smoked’ when visiting their physicians during the campaign (p< 0.025); This did not differ significantly between intervention groups Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: One third of patients in the workshop group reported receiving self‐help material compared to 11% in the no‐assistance group (p< 0.001) |

|

Lennox 1998 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Fourteen months follow‐up: There was no significant difference in sustained abstinence at 14 months between intervention (3.6%) and control (4.7%). Eight months follow‐up: No significant difference was observed between intervention and control groups as to whether an attempt was made to give up smoking at any time during the study period. |

| Lennox 1998 Secondary outcomes |

Number of smokers counselled: No significant difference in discussion of smoking with doctors, nurses or health visitors, however results in both groups were above 70%; Intervention subjects who smoked were more likely than control subjects who smoked to recall smoking having been mentioned in a consultation during the 14‐month follow‐up period (significant for GP consultations at the 10 percent level, but not for consultations with practice nurses or health visitors |

|

Sinclair 1998 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Nine month follow‐up: There was no significant difference in nine month continuous abstinence with Intervention group 12%, control 7.4%, and no difference in one month point prevalence. |

| Sinclair 1998 Secondary outcomes |

Number of smokers counselled: Patients consulting training pharmacists were significantly more likely to report discussion of smoking (85% vs 62.3%) Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Anti‐smoking products were bought by most subjects following enrolment, however, intervention subjects were significantly more likely to make a purchase (p = 0.0085); There was a significantly greater use of nicotine patches relative to nicotine gum in the intervention group compared with the control group (p = 0.029). Overall, approximately three‐quarters of the customers used patches compared with a quarter using gum |

|

Stretcher 1991 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Six months follow‐up: There were no significant differences between 6 month validated abstinence rates, which ranged from 1.7% to 5.7% |

| Stretcher 1991 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: Trained physicians were significantly more likely to advise smokers to quit (73% vs 58%) based on physician reported outcomes, however patient reports of this outcome are not significant Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Overall there were no significant differences in scheduling follow‐up appointments; According to patient outcomes however, more tutorial physicians asked to schedule follow‐up appointments compared to non‐tutorial physicians (p< 0.05) Number of smokers counselled: A prompt alone achieved similar counselling levels compared to control (75% vs 70% respectively) and there was no significant interaction between tutorial and prompt; After adjusting for pre‐test scores and speciality, physicians receiving the tutorial reported a significantly greater number of patients advised to quit (76%) compared to non‐tutorial physicians (69%) (p< 0.05) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: All physicians were equally likely to give self help materials Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: There were no differences in the proportion of physicians who prescribed nicotine gum Number of smokers prescribed a quit date: There were no differences in advice to set a quit day, but the trained group was significantly more likely to write a quit day prescription according to physicians; Patients reported that significantly more tutorial physicians prescribed a quit date than non‐tutorial physicians, however when groups were combined (tutorial and prompt, prompt only and tutorial only) this was not significant |

|

Swartz 2002 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: Intervention subjects were more likely to quit at follow‐up (14.8% quit percentage) compared to control subjects (10.7%). Although this result was not statistically significant (p= 0.08), authors of the study report long‐term clinically important reductions. |

| Swartz 2002 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to set a quit date: There was no significant difference between intervention and control groups for patients being advised to quit smoking (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.83) Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: No significant difference was observed between intervention and control groups for patients asked to make a follow‐up appointment (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.51) Number of smokers counselled: Providers discussed counselling more in the intervention group compared to control (27.7% vs. 20.8%; OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.02) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: There was no statistically significant difference between groups for the prevision of self‐help materials (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.43) Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Subjects in both intervention and control groups had similar offers for the provision of nicotine replacement therapy (intervention 46.2%, control 18.6%, OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.25) |

|

Twardella 2007 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: Point prevalence of smoking abstinence was 3%, 3%, 12% and 15% for the control, treatment plus incentive (TI), treatment plus medication (TM) and treatment plus incentive and medication (TI+TM) arms respectively. There were statistically significant differences between the TM, TI+TM and control arms (p= 0.046 and p= 0.02, respectively). Continuous abstinence (for at least 6‐months) was higher in the TM arm (13/140, 9%) and TI+TM arm (17/219, 8%) compared to the control arm (1/74, 1%) and TI arm (2/144, 1%), however this difference was not statistically significant. |

| Twardella 2007 Secondary outcomes |

Number of smokers counselled: No significant differences were observed for number of smokers counselled between the four groups (control 59%, TI 73%, TM 67%, TI+TM 65%) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: A significant difference was observed when comparing TM group to control group (p=0.03), however no other between group difference were observed (control 15%, TI 32%, TM 31%, TI+TM 24%) Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: There was a significant difference between groups for prescription of nicotine replacement therapy, particularly for those provided with reimbursement for costs of the medication (TM and TI+TM) (control 7%, TI 13%, TM 30%, TI+TM 22%) |

|

Unrod 2007 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Six months follow‐up: Seven day point prevalence of abstinence results were higher in the intervention group (12%) than the control group (8%), however this difference approached but did not reach significance (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.94 to 3.34, p= 0.078). |

| Unrod 2007 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment:Intervention physicians were five times more likely to arrange a follow‐up appointment (47.5%) compared to control (9.7%) (OR 8.14, 95% CI 3.98 to 16.68, p< 0.0001) Number of smokers counselled: Significantly more intervention physicians provided quit smoking assistance to their patients (55.1%) compared to control physicians (20.2%) (OR 4.31, 95% CI 2.59 to 7.16, p< 0.0001) Number of smokers receiving self‐help materials: Physicians in the intervention group were more than three times as likely to provide self‐help materials to patients (32.3%) compared to control physicians (6.9%) (OR 5.14, 95% CI 2.60 to 10.14, p< 0.0001) |

|

Wang 1994 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

Six months follow‐up: Statistically significant difference favouring the lesson intervention over the control (p=0.02) and significant difference (p=0.054) between lessons (G1) and poster (G2), however there was no significant difference between group 2 and control. When group 1 and group 2 were combined in meta‐analyses and adjusted for potential clustering effects, no significant differences were observed. |

| Wang 1994 Secondary outcomes |

No secondary outcomes were reported |

|

Wilson 1988 Point prevalence/ continuous abstinence |

One year follow‐up: Differences between the training arm and the other two arms were significant for sustained abstinence at one year and for 2 point prevalence, but not for one year point prevalence. Results were similar when mean cessation percentages were adjusted for baseline values. Twelve month sustained abstinence results were 8.8% for the intervention group, compared to 6.1% and 4.4% in the two comparison arms. However, when the two intervention groups were combined and adjustments for potential clustering effects taken into account, these results were no longer significant for point prevalence or continuous abstinence. |

| Wilson 1988 Secondary outcomes |

Patient asked to make follow‐up appointment: Training groups more likely to ask for a quit date (54%) and arrange follow‐up (12%) than gum only (12%/22%) or usual care (2%/4%) Number of smokers counselled: Training (85%) and gum (70%) groups more likely to mention smoking than usual care (31%) Number of smokers receiving nicotine gum/replacement therapy: Training (63%) and gum (59%) groups more likely to suggest use of gum than usual care (9%) |

Overall summary of smoking behaviour

Four out of 13 studies detected significant intervention effectiveness in training health professionals to influence point prevalence of smoking in their patients at primary follow‐up (Cohen (Doc) 1989; Cornuz 2002; Twardella 2007; Gordon 2010). Out of the eight studies reporting continuous abstinence at primary follow‐up, only one reported a statistically significant effect in favour of the intervention (Gordon 2010). Fifteen of the 17 included studies (the exceptions being Kottke 1989 and Hymowitz 2007) could be included in a meta‐analysis for the primary outcome of smoking (Analysis 1.1). Using a fixed effect model there was a statistically and clinically significant effect in favour of the intervention for point prevalence abstinence (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.55, 14 trials, I² = 57%) and continuous abstinence (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.03, 8 trials, I² = 59%) (Figure 3). Using only the stricter outcome of continuous abstinence for studies reporting both types of cessation, a pooled estimate for all 15 trials gave a similar estimate (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.89, I² = 55%, data not displayed). Since the heterogeneity in this analysis approached the level at which we proposed a random‐effects model we did a sensitivity analysis; the point estimates were similar and the wider confidence intervals continued to exclude no effect. The trial contributing most evidently to the heterogeneity, particularly for the continuous outcome, was Lennox 1998 in which the point estimates for both abstinence outcomes favoured the control group.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 The effect of training health professionals on patient smoking cessation, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 The effect of training health professionals on patient smoking cessation

Two studies could not be included in the meta‐analyses. In the Kottke 1989 study at one year follow‐up almost half of the participants in each group who were smoking at baseline reported quit attempts for at least 24 hours during the previous year, with a mean duration of cessation of two months. No differences between the three groups were identified. For the Hymowitz 2007 study there was an increase in the special training condition of reported quitting during the past year of 3.8% (an 8.5% increase over baseline levels), however the change from baseline failed to achieve statistical significance. Among parents associated with standard training, the change was only 0.8%.

As per pre‐specified methodology, a funnel plot examined the primary outcome of smoking cessation using contour lines to assess the presence of reporting biases. No publication biases were identified (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 The effect of training health professionals on patient smoking cessation

Overall summary of secondary outcomes

Asked to set a quit date for stopping (quit date)

Nine studies reported the effect of training health professionals on the number of patients being asked to set a quit date, eight of which could be included in the meta‐analysis producing a significant result (random effects OR 4.98, 95% CI 2.29 to 10.86, Analysis 1.2). Only three of the seven studies crossed the line of no effect (Strecher 1991; Cornuz 2002; Swartz 2002) but there was a very high level of heterogeneity (I² = 90%) suggesting that not all interventions had the same impact on this outcome. Subgroup analyses suggest that some of the heterogeneity might be due to whether or not the patient intervention included an offer of NRT. The two studies (Strecher 1991; Swartz 2002) that reported this outcome and did not include NRT showed no difference between groups. The other studies showed more consistent evidence that intervention increased numbers although the size of effect remained variable (Analysis 2.1). Contrary to what might have been expected, the studies where training took only a single session had higher effect sizes (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Wilson 1988, Analysis 3.1) compared to the five studies using multiple sessions. Duration of training was similar for the three sub‐groups being examined (Analysis 4.1) as was intervention delivery via one‐on‐one compared to group sessions (Analysis 5.1). There was a large amount of variability between the use of prompting and provision of feedback, however this difference was not significant (Analysis 6.1). Intervention delivery by a doctor (six studies) or dentist (one study) produced a larger effect size compared to delivery by a healthcare worker (Swartz 2002), which may also explain some of the heterogeneity (Analysis 7.1). When comparing follow‐up periods, studies reporting between six and nine months (Cohen (Dent) 1989; Cohen (Doc) 1989; Strecher 1991) and between nine and 12 months (seven studies) produced similar effect sizes and large amounts of variability (Analysis 8.1). Studies judged to be at lower risk of bias were more likely to show evidence of an effect (seven studies) compared to studies with between three and five categories rated at high risk of bias (Strecher 1991), however the between group analysis did not suggest that this was a source of heterogeneity (Analysis 9.1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 The effect of training health professionals on patient smoking cessation, Outcome 2 Patient asked to set a quit date.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sub‐group: treatment type, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Sub‐group: treatment intensity ‐ Number of sessions, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Sub‐group: treatment intensity ‐ Total exposure, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sub‐group: mode of intervention delivery, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sub‐group: behavioural change technique used, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sub‐group: type of professional being trained, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

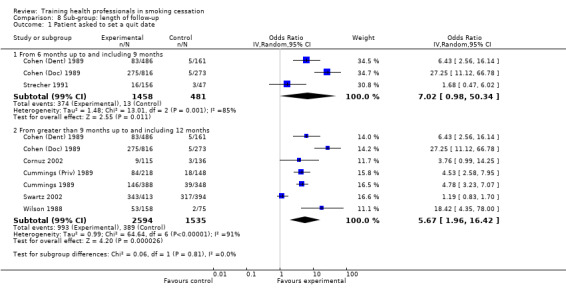

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sub‐group: length of follow‐up, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sub‐group: risk of bias in the studies, Outcome 1 Patient asked to set a quit date.

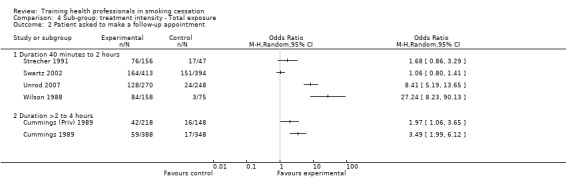

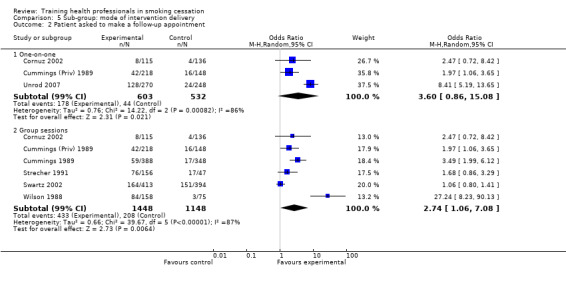

Given a follow‐up appointment

There was a significant increase in the intervention arm for patients being asked to make a follow‐up appointment, as reported in seven studies available for meta‐analysis (random effects OR 3.34, 95% CI 1.51 to 7.37, Analysis 1.3), although significant heterogeneity was observed (I² =92%). When comparing interventions using NRT with those that used counselling alone, an I² of 96% was observed, meaning any results from a pooled analysis would be too unreliable. As such only a visual analysis of odds ratios and confidence intervals are presented, showing similar variability between sub‐groups (Analysis 2.2). Subgroup analyses for treatment intensity suggest that some of the heterogeneity might be due to whether or not the training sessions were single or multiple. Two studies that employed single sessions (Wilson 1988; Unrod 2007) were more likely to show an effect (although variability was observed), compared to five studies using multiple sessions, which produced a smaller effect estimate with less variability (Analysis 3.2). When comparing the duration of the training, significant heterogeneity was once again observed between groups, with studies presenting large amounts of variability, resulting in a pooled estimate being unreliable for comparison (Analysis 4.2). There was little difference between delivery by one‐on‐one compared to group sessions (Analysis 5.2), and due to significant heterogeneity (I² =96%) the pooled comparison of prompting and provision of feedback was not possible, although a visual display shows variability is mostly due to the Unrod 2007 study (Analysis 6.2). Similar to other outcomes, delivery of the intervention by a doctor (assessed in seven studies) meant that more patients were likely to have a follow‐up appointment compared to intervention delivery by a healthcare worker (one study), however the Swartz 2002 study was present in both sub‐groups as the intervention included delivery by both a doctor and healthcare worker, as such a statistical between group comparison was not performed (Analysis 7.2). Reporting of results at different follow‐up periods were similar between sub‐groups, although the five studies with follow‐up between nine and 12 months had similar distributions with the exception of the Wilson 1988 study, which significantly favoured the intervention and had wide confidence intervals (Analysis 8.2). No between group differences were observed for quality of the studies (Analysis 9.2).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 The effect of training health professionals on patient smoking cessation, Outcome 3 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sub‐group: treatment type, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Sub‐group: treatment intensity ‐ Number of sessions, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Sub‐group: treatment intensity ‐ Total exposure, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sub‐group: mode of intervention delivery, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sub‐group: behavioural change technique used, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sub‐group: type of professional being trained, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sub‐group: length of follow‐up, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Sub‐group: risk of bias in the studies, Outcome 2 Patient asked to make a follow‐up appointment.

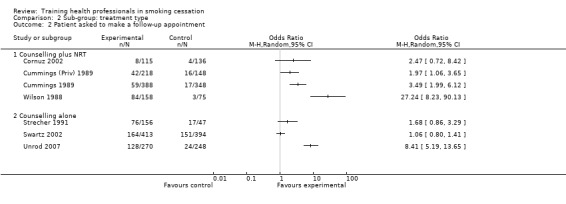

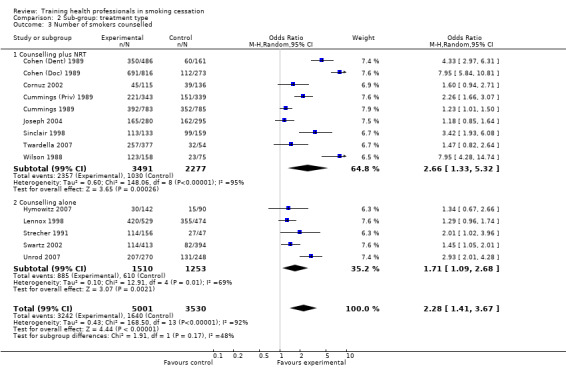

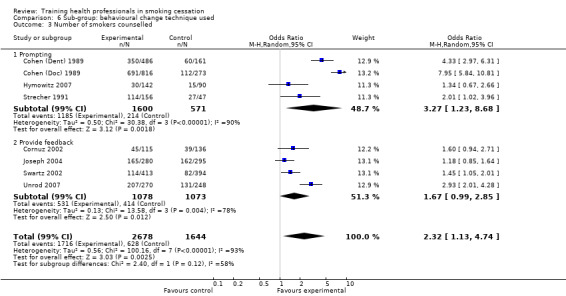

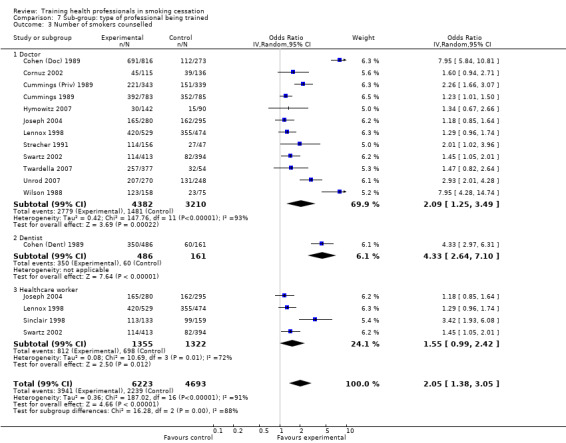

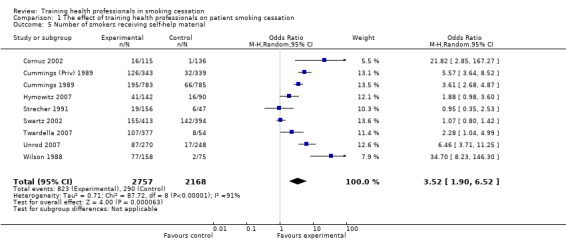

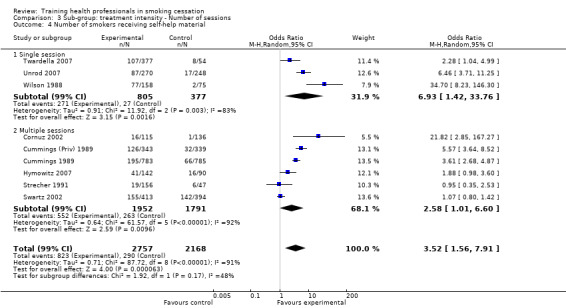

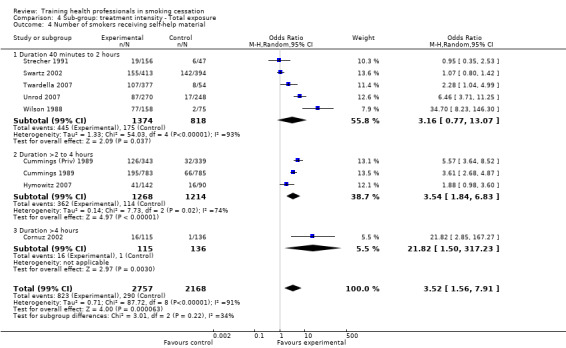

Counselled