Abstract

Objective:

To understand the mechanisms of mindfulness’ impact on migraine.

Background:

Promising mindfulness research demonstrates potential benefit in migraine, but no data-driven model exists from the lived experiences of patients that explains the mechanisms of mindfulness in migraine.

Methods:

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted on adults with migraine who participated in two Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) clinical trials (n=43). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and summarized into a framework matrix with development of a master codebook. Constructivist grounded theory approach was used to identify themes/subthemes.

Results:

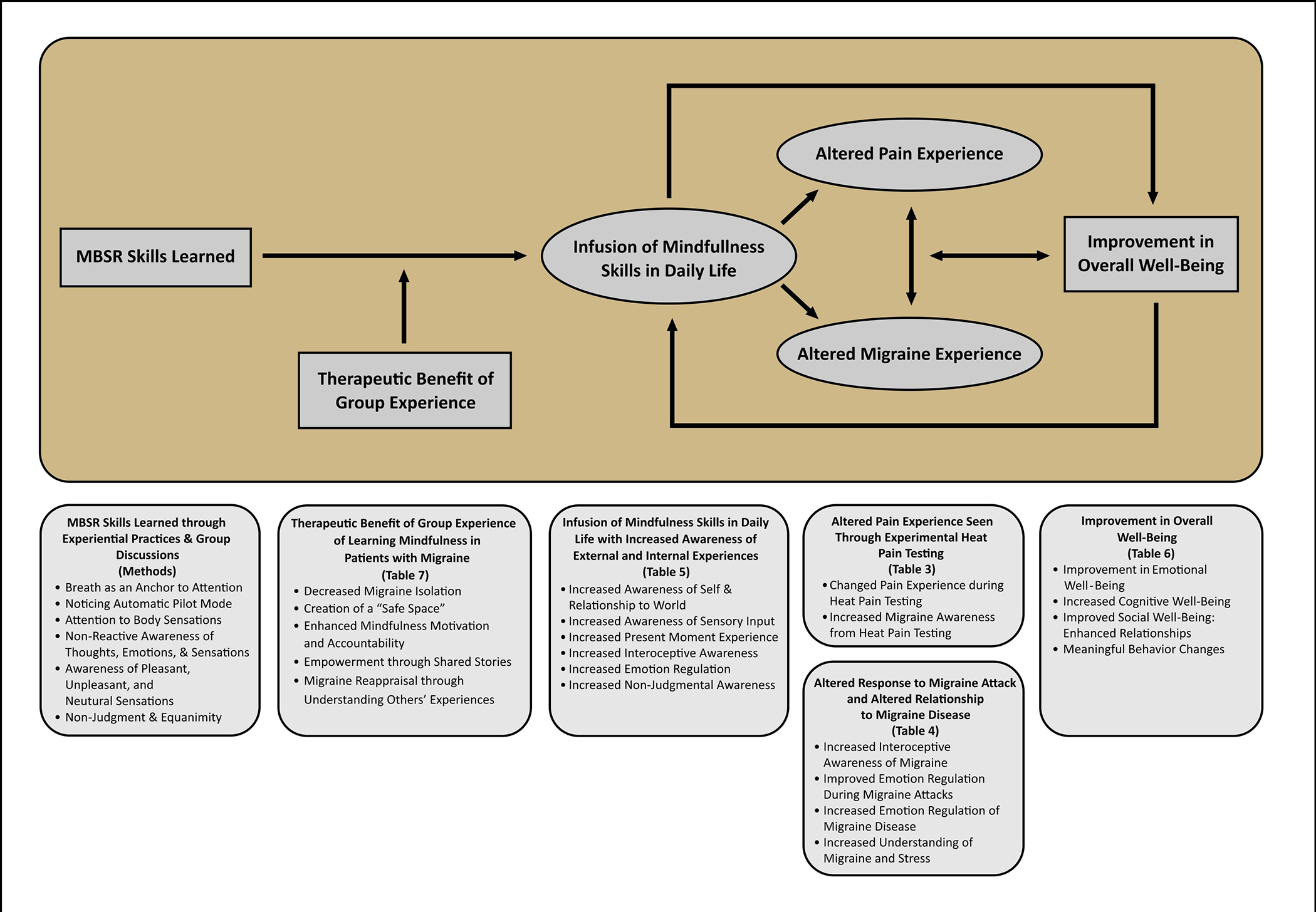

Participants who learned mindfulness techniques through MBSR experienced altered pain perception, altered response to migraine attacks and disease, increased awareness of external and internal experiences, improved overall well-being, and group benefits. Mindfulness resulted in earlier stress-body awareness and increased interoceptive awareness resulting in earlier attack recognition, leading to earlier and more effective management. Inter-ictal factors of self-blame, guilt, and stigma decreased while migraine acceptance, hope, empowerment, self-efficacy, and self-compassion increased. Improved emotion regulation resulted in decreased fear of migraine, pain catastrophizing, anticipatory anxiety, and pain reactivity. Although taught as a prevention, mindfulness was used both acutely and prophylactically. We created a conceptual model hypothesizing that MBSR skills led to an infusion of mindfulness in daily life, resulting in altered pain perception and experience, ultimately leading to improvement in overall well-being, which may positively feedback to the infusion of mindfulness in daily life. The therapeutic benefit of learning mindfulness in a group setting may moderate these effects.

Conclusions:

This study identified several new potential mechanisms of mindfulness’ effect on migraine. After taking MBSR, participants reported altered pain and migraine perception and experiences. Increased stress-body and interoceptive awareness resulted in earlier migraine awareness and treatment. Mindfulness may target important inter-ictal factors that affect disease burden such as fear of migraine, pain catastrophizing, and anticipatory anxiety. This study is the first data-driven study to help elucidate the mechanisms of mindfulness on migraine from patient voices and can help direct future research endeavors.

Keywords: mindfulness, MBSR, migraine, headache, mechanisms, qualitative

Introduction:

Mindfulness has emerged as a potential treatment option for migraine.1, 2 Pharmacological treatments are often limited by side effects, lack of efficacy, and/or costs.3–5 Prior studies have demonstrated benefits of mindfulness for chronic pain conditions.6 Research assessing mindfulness specifically for migraine is critical as migraine is different from chronic pain, involving intermittent unpredictable attacks of acute pain and sensory amplification (e.g., photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, etc.). Recent clinical trials of mindfulness interventions in patients with migraine are promising.2, 7, 8

We conducted two randomized clinical trials evaluating Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in adults with migraine.9, 10 MBSR was taught with the standardized curriculum with eight weekly two-hour sessions plus a “retreat” day. During the intervention, certified MBSR instructors led participants through experiential mindfulness practices including body scan, sitting meditation, walking meditation, and sitting and standing gentle mindful yoga. During these practices, participants engaged in both focused attention (sustaining attention on sensations of the breath, while disengaging from distractors such as mind-wandering), and open monitoring (non-reactive awareness of the flow of cognition, emotions, and sensations).11 Dialogue and inquiry provided an opportunity for participants to discuss their experiences with mindfulness practices and how to incorporate them into daily life. Typical mindfulness skills learned included: use of the breath as an anchor; noticing automatic “pilot-mode” and stress reactivity; attention to body sensations; non-reactive awareness of thoughts, emotions, and sensations; awareness of pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral sensations; and non-judgment and equanimity. For these studies, MBSR was not modified for the migraine patient population. Participants were given MP3 files or compact discs and instructed to use them for daily practice at home, with logs demonstrating average participant practice of 34 (Standard Deviation, SD=11) minutes per day in the pilot study9 and 33 (15) minutes per day in the larger study, with an average practice of 4.2 (2.5) days per week.10

The neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness are actively being explored by researchers across the world.12, 13 We previously published a narrative review discussing potential mechanisms of mindfulness in migraine, which included: (1) alterations in pain perception via de-coupling the sensory and affective components of pain; (2) enhanced interoceptive body awareness; (3) regulation of autonomic dysfunction seen in patients with migraine; and (4) improved cognitive modulation of pain.2 Our quantitative results from our clinical trials showed meaningful clinical improvements in headache-related disability, pain catastrophizing, headache self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms, with benefits seen out to 36 weeks.9, 10 After MBSR, participants had a 36% reduction in response to experimental heat pain intensity and a 30% reduction in pain unpleasantness, suggesting a shift in pain perception that may alter migraine experience.10 To further understand these quantitative findings to investigate the mechanisms of how mindfulness impacts migraine, we went to the lived experiences of the participants with migraine who took the MBSR course. To ensure we fully captured their experiences and since there is currently no data-driven model that explains the mechanisms of mindfulness in migraine, we used a hypothesis-free, constructivist grounded theory approach to analyze the qualitative interviews.9, 10 The objective of our study was to better understand potential mechanisms of mindfulness’ benefit on migraine by listening and understanding the patient perspective.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured in-person qualitative interviews from participants with migraine from two randomized clinical trials on MBSR9, 10 (n=43) registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01545466 and NCT02695498) with IRB approvals from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Wake Forest School of Medicine, respectively. All participants gave written informed consent prior to participation. Full methods of both clinical trials have been fully described previously.9, 10, 14

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

Briefly, a pilot study was conducted in Boston, Massachusetts of MBSR (n=10) vs a wait-list control group (n=9), with enrollment between January and March 2012.9 One hundred percent of those randomized to MBSR completed qualitative interviews. A larger study (n=89) was conducted in Winston-Salem, North Carolina of MBSR (n=45) vs an active comparator Headache Education control group (n=44), enrolled between August 2016 and October 2018.10 Of those randomized to MBSR in the larger study, 73.3% (33/45) completed qualitative interviews, making the total response rate of participants completing qualitative interview in both studies 78.2% (43/55). Of the 12 participants not interviewed in the larger study, 4 were lost to follow up, 4 withdrew from the study, and 4 were not interviewed during their 12 week study visit.10 Inclusion criteria for both studies included participants keeping prospective diaries to confirm migraine frequency (inclusion of 4–14 days/month in the pilot study and 4–20 days/month in the larger study). UCNS-certified headache physicians conducted in-person evaluations to confirm International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) migraine diagnoses. Participants remained on their migraine medications for the study duration and were blinded to group assignment.

Quantitative Sensory Testing

Quantitative sensory testing (QST, e.g., “heat pain testing”) was conducted at baseline and three follow-ups (12, 24, 36-weeks post-baseline) on 33 participants in the larger study, using a 16 × 16 mm thermal probe with the MEDOC TSA-II. Both intensity and unpleasantness were measured using a 15 cm sliding Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), ranging from “no pain sensation” to “most intense imaginable” and from “not at all unpleasant” to “most unpleasant imaginable,” respectively.15, 16

Intervention

The participants in this study who completed qualitative interviews had undergone the standardized MBSR intervention that was delivered with 8 weekly classes of 2 hour duration.

Interviews

All interviews were conducted after participants completed MBSR intervention at the 12-week study visit. Expert qualitative interview consultants from the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes (Q-Pro) Shared Resource provided educational training, consultation, and resources to all team members on how to appropriately conduct effective un-biased qualitative interviews. Qualitative interview techniques that were taught included appropriate probing techniques to clarify details without leading participants. A semi-structured interview guide was utilized during qualitative interview sessions, which contained mostly open-ended questions (see supplementary materials). The main intent of the interviews was to capture participant experiences with the clinical trial and the interventions. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews from the entire larger study (n=71) lasted on average 47 min (SD 13.9) with a range of 18–77 min and a total of nearly 3300 min of recorded interviews.14

Sample Size

For the pilot study, the goal sample size of 34 was not reached (time constraints unrelated to the feasibility of the study [e.g., REW’s relocation] limited recruitment to 3 months and decreased the ability to reach the target sample size).9 For the larger randomized clinical trial, we estimated a final sample size of 44 per group to provide at least 90% power with an alpha of 0.05 (using PASS statistical software).10 For this qualitative study, all participants from both studies who completed MBSR and were interviewed were included (n=43) to ensure we fully captured all potential mechanisms of mindfulness in migraine.

Qualitative Data Analyses

Themes and subthemes were identified using Charmaz’ hypothesis-free, constructivist grounded theory approach.17 Under the leadership of a qualitative research specialist (from Wake Forest Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Developing Shared Resource), team members who were not mindfulness experts (undergraduate, masters, and MD/PhD students, n = 7) received weekly training in qualitative data analysis over 6 months. The qualitative data expert provided educational training, consultation, and participation in team meetings. All students were educated on qualitative interview techniques and analyses using educational materials such as the textbook The Coding Manual for Qualitative Research,18 with regularly assigned readings reviewed (for further details, see Estave et al,14).The research team, including the PI, analyzed the data during weekly meetings (August 2019-January 2022), beginning with summarizing and analyzing transcripts into a framework matrix of 12 key domains extrapolated from the interview guides (see supplementary materials).19–22 Investigator triangulation23 was achieved for 50% of the transcripts until a consistent technique was established. All final summaries were cross-checked against the original transcripts to ensure accuracy. Emerging ideas, potential codes, and any challenges were then discussed at team meetings. A master codebook was created until meaning saturation was achieved.24 Dedoose software was used for data analysis of transcripts. The codebook was applied to each transcript by six independent coders. One-third of the interviews were assessed by two independent raters, with inter-rater reliability tests conducted to confirm consistency. An iterative process of coding, categorization, discussion, and disagreement resolution continued until all team members agreed on a final set of themes, subthemes, and table organization. Experts in qualitative interviewing, mindfulness, and/or behavioral interventions (ES and PG) were then included to help interpret results. For further details on the research team, please see subsection below. Additionally, themes, subthemes, and the conceptual model were continually discussed to increase awareness of theoretical sensitivity and facilitate reflexivity of the researchers. An audit trail was maintained throughout the entirety of data analysis with notes from each research team meeting, within Dedoose software, and through use of an online Sharepoint team site (maintained with high security behind a HIPAA compliant firewall) to organize and maintain study files (e.g., framework matrices, etc.).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used throughout to describe continuous and categorical data. Percentages and standard deviations were used to describe baseline characteristics of participants. Percentages and frequency were also provided for the number of participants who completed qualitative interviews. All statistical analyses were performed using R Software.

Research Team

At the time of data analysis, the research team included the PI, a paid consultant in qualitative interviewing, and 7 students of various training levels, including undergraduate (n=4), masters (n=2), and MD/PhD students (n=1). These students were thoroughly trained in qualitative data analysis as described above and were not mindfulness, migraine, or qualitative data experts. Given the PI’s expertise in mindfulness, the PI was able to identify and recognize meaningful data relevant to the themes and conceptual model during data analysis and interpretation, thus employing theoretical sensitivity throughout the process. For data interpretation, content expertise included those with mindfulness clinical trial expertise (REW and PG), behavioral intervention expertise (ES) and qualitative interviewing expertise (PG and ES).

Results:

Baseline Characteristics

Participants in both the pilot and larger study were an average of 44 (SD=13.0) years old, mostly women (92%), White (89%), and had private health insurance (87%) (Table 1). Most participants had a 26 (SD=14.0) year history of migraine, with 9.8 (3.3) headache days/month, 6.6 (2.7) migraine days/month, and high disability at baseline (HIT-6 score of 63.0, SD 7.2).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants from Both Clinical Trials

| Baseline Characteristic | Pilot RCT with MBSR n=10 n (%) | Larger RCT with MBSR n=37a n (%) | Combined Pilot and Larger RCTs (n=47) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (y); mean (SD) | 46 (17) | 44 (12) | 44.43 (13) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 9 (90) | 34 (92) | 43 (92) |

| Male | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 4 (9) |

| Race | |||

| White | 9 (90) | 33 (89) | 42 (89) |

| Black or African American | 1 (10) | 4 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Primary Health Insurance | |||

| Private | 8 (80) | 33 (89) | 41 (87) |

| Medicare/Medicaid/ Other public | 2 (20) | 4 (11) | 6 (13) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/Living with partner | 9 (90) | 27 (74) | 36 (77) |

| Divorced/Separated/ Widowed | 0 | 5 (13) | 5 (11) |

| Single-never married | 1 (10) | 5 (13) | 6 (13) |

| Current Employment Status | |||

| Employed/Self-employed full time (>30 hours/week) | 4 (40) | 25 (68) | 29 (62) |

| Employed part-time | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | K9L |

| Student, Homemaker, Volunteer | 2 (20) | 6 (16) | 8 (17) |

| Unemployed, Retired | 3 (30) | 3 (8) | 6 (13) |

| Education | |||

| ≤High School | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 4 (9) |

| College | 4 (40) | 20 (54) | 24 (51) |

| Graduate Degree | 5 (50) | 14 (38) | 19 (40) |

| Recruitment source | |||

| Academic Medical Center/Provider Referral | 8 (80) | 18 (49) | 26 (55) |

| Community | 2 (20) | 19 (51) | 21 (45) |

| Headache Features | |||

| Disease characteristics during Baseline HA Log | |||

| Headache days during 28-day baseline, mean (SD) | 10.4 (3.1) | 9.6 (3.4) | 9.8 (3.3) |

| Migraine days during 28-day baseline, mean (SD) | 4.2 (2.9) | 7.3 (2.6) | 6.6 (2.7) |

| Disease History | |||

| Years with migraine, mean (SD) | 26 (19) | 26 (13) | 26 (14.4) |

| Migraine with Aura | 4 (40) | 14 (38) | 18 (38.3) |

| Family history of headache | 7 (70) | 25 (68) | 32 (68.1) |

| Use of Treatments | |||

| Current Use of Prophylactic Treatment | 8 (80) | 12 (32) | 20 (43) |

| Current Use of Acute Medicationb | 10 (100) | 33 (89) | 43 (92) |

| Experienced Headache Medication Side Effect | 5 (50) | 23 (62) | 28 (60) |

| Triggers, Co-Morbidities, and Disability | |||

| Stress or let-down stress as a trigger | 8 (80) | 28 (76) | 36 (77) |

| Current or past diagnosis of depression | 2 (20) | 15 (41) | 17 (36) |

| Current or past diagnosis of anxiety | 2 (20) | 12 (32) | 14 (30) |

| MIDAS-one month at baselinec, mean (SD) | 12.5 (9.8) | 13.7 (11.5) | 13.4 (11.2) |

| HIT-6 at baseline, mean (SD)d | 63.0 (8.0) | 63.0 (7.0) | 63 (7.2) |

Baseline characteristics from the larger RCT represent participants who completed visit 2 (4 additional participants than the 33 who participated in the qualitative interviews)

Missing data from larger RCT for acute medication use (n=3 or n=4 MBSR group)

Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS)- one month was used to decrease recall bias and improve the accuracy of the results (compared to the typical 3 month recall period).30–32 Scores range (0–115), higher scores reflect greater disability, MIDAS is typically used as an average over 3 months; to facilitate interpretation of the MIDAS-one month data presented, the mean estimate results (but not the confidence intervals) can be multiplied by 3 for conversion to the typical 3 month assessment;30 score range for 3 month MIDAS: 0–5: little or no disability, 6–10 mild disability, 11–20 moderate disability, 21+ severe disability.

Headache Impact Test-6 (36–78), higher scores reflect greater headache impact, score range: <49: little to no impact, 50–55: some/moderate impact, 56–59: substantial impact, 60+ severe impact.

Main Findings

The themes and subthemes from our main findings are summarized in Table 2, with representative quotations in Tables 3–7. Full tables can be found online (supplementary tables 1–5). We found that through learning mindfulness with an MBSR course, participants with migraine had altered pain experience demonstrated through heat pain testing (Table 3); altered response to migraine attacks and relationship to migraine disease (Table 4); infusion of mindfulness skills in daily life with increased awareness of external and internal experiences (Table 5); improvement in overall well-being (Table 6); and therapeutic benefits of the group experience (Table 7).

Table 2:

Main Findings, Themes, and Subthemes of Mechanisms of Learning Mindfulness through MBSR in Adults with Migraine

| Main Finding (Table) | Themes and Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Altered Pain Experience Seen Through Experimental Heat Pain Testing (Table 3) |

Changed Pain Experience during Heat Pain Testing • Changed perception of experimental heat pain testing • Decreased reactivity to pain during heat pain testing |

| Increased Migraine Awareness from Heat Pain Testing • Better understanding of migraine pain through heat pain testing • Differentiating migraine pain intensity from unpleasantness | |

| Altered Response to Migraine Attack (Table 4A) |

Increased Interoceptive Awareness of Migraine • Increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals resulting in earlier awareness of migraine attack • Earlier migraine attack awareness leads to altered use of medications • Use of mindfulness as an acute treatment • Use of breath during migraine attacks and with life challenges • Acknowledging and accepting pain during an attack • Interoceptive stress awareness prevents migraine trigger |

|

Improved Emotion Regulation during Migraine Attacks • Awareness of, and less: fear of migraine • Awareness of, and less: pain catastrophizing • Awareness of, and less: anticipatory anxiety • Decreased reactivity to migraine pain • Increased pain acceptance with decreased self-blame, guilt, and stigma • Self-compassion during migraine attacks | |

| Altered Relationship to Migraine Disease (Table 4B) |

Increased Emotion Regulation of Migraine Disease • Migraine acceptance • Hope and empowerment • Improved self-efficacy |

|

Increased Understanding of Migraine and Stress • Heightened awareness of migraine and stress relationship • Improved ability to manage stress and migraine | |

| Infusion of Mindfulness Skills in Daily Life with Increased Awareness of External Experiences (Table 5A) |

Increased Awareness of Self & Relationship to World • Meta-awareness: Observation of external world separate from self (“self as an observer”) • Broader life perspective • Non-reactive awareness through decentering and re-perceiving |

|

Increased Awareness of Sensory Input • Heightened awareness and appreciation of nature • Increased exteroceptive (e.g., audio, visual, olfactory) sensory sensitivity | |

| Infusion of Mindfulness Skills in Daily Life with Increased Awareness of Internal Experiences (Table 5B) |

Increased Present Moment Experience • Decreased auto-pilot mode • Breath as an anchor leads to non-reactivity |

|

Increased Interoceptive Awareness: Awareness of the Body, Thoughts • Increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals with embodied awareness • Meta-cognition: awareness of thoughts separate from self | |

|

Increased Emotion Regulation • Improved emotional insight • Downregulation of emotional reactivity • Earlier stress-body awareness with sensitivity to stress interoceptive signals • Improving stress response through awareness | |

|

Increased Non-Judgmental Awareness • Self-acceptance through non-judgement • Acceptance of life stressors • Increased self-compassion | |

| Improvement in Overall Well-Being (Table 6) |

Improvement in Emotional Well-Being • Enjoyment and happiness • Equanimity (mental calmness, ability to relax) • Improved depressive symptoms • Improved anxiety • Prioritizing and accepting time for self-care |

|

Increased Cognitive Well-Being • Awareness of mind-body integration • More focused, ability to think more clearly | |

|

Improved Social Well-Being: Enhanced Relationships • Increased empathetic understanding and emotional literacy • More patience with self and others • Improved listening skills • Improved relationships through decreased reactivity | |

|

Meaningful Behavior Changes • Improved eating and drinking habits • Improved activity level • Improved sleep hygiene | |

| Therapeutic Benefit of Group Experience of Learning Mindfulness in Patients with Migraine (Table 7) |

Therapeutic Group Benefits • Decreased migraine isolation • Creation of a “safe space” • Enhanced mindfulness motivation and accountability • Empowerment through shared stories • Migraine reappraisal through understanding others’ experiences |

Table 3:

Altered Pain Experience seen through Experimental Heat Pain Testing after Learning Mindfulness in Patients with Migraine

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Changed Pain Experience during Heat Pain Testing | Changed perception of experimental heat pain testing | • [During the second heat pain testing after taking the MBSR class] I think maybe I perceived [the pain] differently...I feel like there were more times where there was no pain this time...I think the first time I was...calling it pain but looking back I’m like “was that really painful or was it just hot?”...[The 2nd time] I was more aware of...what was painful and what wasn’t. |

| Decreased reactivity to pain during heat pain testing | • [During the second heat pain testing, compared to the first, after taking the MBSR class] I did try to kind of breathe through it and not be as reactive to it this time I think. I think I was able to take a step back and really assess the values instead of just reacting to how it felt. | |

| Increased Migraine Awareness from Heat Pain Testing | Better understanding of migraine pain through heat pain testing | • I think that the heat study actually helped to put it in good perspective, you know to kind of have that physical example and then practice with using the scale [with my headaches] and really stopping to think that “okay yes I can feel this sensation, when does it become painful?” You know “how painful is this? How unpleasant was it?”...I think it kind of is easier to...understand after doing that. |

| Differentiating migraine pain intensity from unpleasantness with mindfulness | • It’s...not always something that is easy to differentiate [the intensity and unpleasantness of migraine pain]. I think especially with migraines because they are so painful but you get to a point where they are so painful that you think they are always that painful and sometimes they aren’t that painful, they are just unpleasant. But I think that the mindfulness program helps differentiate, helps you be more aware of, “ok maybe this isn’t that painful maybe it’s just more unpleasant.” But when you’ve had migraines for so long you just assume that it’s always that painful. |

Table 7:

Therapeutic Benefits of Group Experience of Learning Mindfulness in Patients with Migraine

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Group Benefits | Decreased feelings of migraine isolation | • You know the first week I was nervous you know meeting new people... but after that and just opening up to each other and realizing that we had so much in common with the way...we’re frustrated and we were handling things and how migraines take things out of your life. |

| Creation of a “safe space” | • It created a sense of safety, I felt...the paradox trying to find inner space, but not feeling disconnected, I felt very supported to be able to relax and let go. | |

| Enhanced mindfulness motivation and accountability | • With the classes you had the support system you know versus doing it at home by yourself you got that support you feel like you’re not the only one you’re all there motivating each other. | |

| Empowerment through shared stories | • The support makes a big difference when you have a group of people that’s walking in the same shoes and you feel like you can talk about it and support means a lot...it really does. I think that in itself is extremely beneficial as well as the strategies and techniques we were learning. • I think it was beneficial to kind of hear other peoples, everyone I think had a completely different experience, but hearing those together just makes you sort of like a team, you feel like a team a little bit. |

|

| Migraine reappraisal through understanding others’ experiences | • I think it increased my empathy or sympathy depending on the situation. When someone says they had a headache, it’s just it’s sort of blank, oh yeah you have a headache. You have no idea what a headache is. And listening to people in my class, listening to what they get as opposed to what I get and I think oh my goodness that’s really bad, to get injections in their head and someone who can’t function for days or someone who’s altered their life to suit their life. I am grateful that I don’t have that. My headaches are bad and I perceive them as bad and they affect my life but when you look at the scheme of things of others’ |

Table 4:

Altered Response to Migraine Attack (4A) and Relationship to Migraine Disease (4B) after Learning Mindfulness

| Table 4A: Altered Response to Migraine Attack after Learning Mindfulness | ||

| Increased Interoceptive Awareness of Migraine | Increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals resulting in earlier awareness of migraine attack | • I think I recognized the headache coming on a little earlier or just that being...more aware of what’s going on in my body and just accepting that this is happening and that leads me to intervene a bit earlier whereas I think before I tried to ignore it until it was building up. |

| Earlier migraine attack awareness leads to altered use of medications |

Taking medications earlier • I think I’m able to notice certain changes in my body when a migraine is starting and so I feel like if I need medicine I can take it earlier because a lot of times I would just wait and then it would be so blown out of proportion the medication may or may not work and it would last days so I think...that has been better...I think I’m taking my medicine earlier. I’m able to notice the signs and symptoms that are...happening in my body when I have a migraine starting.... • Avoidance of medication • The diverting your mind from the actual pain that you are feeling...you can get though very painful periods of time...without having to take medication. |

|

| Use of mindfulness as an acute treatment | • When I know [the headache] is coming [I know]... what I need to do physically...to change its course...by either eliminating it without having to take medication...by simply paying attention to my body like most of the times when I have a headache...I am very tensed...and I am like...oh wait I need to adjust...so I take necessary measures to relax breathe focus on something else and all of a sudden it is gone....it’s like it is coming and when I take necessary measures...to divert it...so it works. | |

| Use of breath during migraine attacks and with life challenges | • I am thinking and I’m stopping, and I’m choosing now to just take a breath. And that’s helping me to not just react. It helps me to put things in perspective. That’s helping me, not just with my headaches, but with anything that’s going on. Even if it’s not a headache day, I am able to manage the day better, I am able to communicate more effectively with whoever it is I’m dealing with because I’m taking that breath, that pause. And it is becoming more automatic. I find myself now taking a breath without even thinking about it. And it’s almost like a trigger that I’m getting stressed. It’s like my body takes the breath for me before I mentally even realize [it]. And there are times when I take a breath consciously and say I need to take a breath. It’s kind of like a dual thing that is going on. | |

| Acknowledging and accepting pain during an attack | • Stopping for a moment to acknowledge where the pain is, what it feels like, you know what’s the quality of the pain, what’s the intensity of the pain – that in and of itself is being mindful. So I would say that I try harder to, not that I’m necessarily going into a formal meditation or sitting meditation, but I find myself more likely to you know getting a heat pack and putting it on my head, go lay in a quiet space, and just kind of focus on my breathing. If it’s really intense, then I try to focus on that [the breathing] as opposed to consistently sitting there and thinking about the pain. | |

| Interoceptive stress awareness prevents migraine trigger | • With actually practicing [body awareness] and noticing what’s happening with your body, especially in moment of stress vs. just doing checks, you know, checking “Am I stressed? Oh no, okay.” I mean doing stuff like that throughout the day, you start to notice more what’s happening with your body. So I do think you pay attention and, for example in migraines, you start to catch it before it happens. Like the other day I felt like if I don’t stop I’m going to have a migraine. So, I just was like, “I’m not even going to go down this path,” and stopped the conversation I was having because I felt like it was going into an argument, so I just stopped, “Alight, I can’t deal with this today, I need to go be somewhere else.” So, I didn’t get into it and never got the headache. But, I don’t think I would’ve noticed that I was feeling like that before. | |

| Improved Emotion Regulation during Migraine Attacks | Awareness of, and less: fear of migraine | • Part of the unpleasantness had to do with being afraid of [migraine attacks] and part of the unpleasantness came from other body sensations, it wasn’t just the pain in my head it was the stomach pain and being tired because it does make you feel tired. And also the anxiety about [having headaches], being anxious about maybe having to leave work or maybe not do things at home, maybe not cook dinner. It helped me identify those factors...I felt like it was a knot that I was untying...It felt like all of these things were a big knot that was making a pain in my life and I have been able to separate them a little bit. I’ve been able to see this anxiety is separate from this anxiety, so let’s just let that one go because really there is nothing there to be anxious about right now. There’s nothing, let’s just calm down and not be anxious about that right now. I was at work and I felt like I was being okay that day, so I didn’t have to be anxious about that. I’m starting to untie those things, to separate them and that is making it less intense. |

| Awareness of, and less: pain catastrophizing | • I think that they are less intense, but I’ve also noticed in my last set of headaches that lasted 3 days that I just kind of felt like I could deal with it, like I can get up and I don’t have to be just laid around. It’s over, it’s done because I don’t have that fear, if you will, that this is never going to get better. “When is the pain going to go away?” I wasn’t just focused on that. I was able to focus on other things like...breathing and just, “Ok, I have a headache, move on, keep going,” and I was able to just deal with it better. And it did seem like the pain was less intense. | |

| Awareness of, and less: anticipatory anxiety | • Yes it has [changed my approach to migraine]. It’s changed in that I don’t think they are going to control my life and I’m not as fearful in waiting for them to come...and I know that even if it does come, I’ll get through it and it won’t be so terrible, I can still live through it. | |

| Decreased reactivity to migraine pain | • Being mindful of yourself, and being responsive instead of reactive to things, and that we’re always going to have the pain, and how we respond to it...I think the goal of these practices was to be aware and to notice things that happen with triggers and things with our body...When we can notice and put those into words, then we can recognize them and try to respond instead of just react. And that, I think helps, because you know these things are going to happen every day, so if you start to feel yourself tense up in your shoulders and in your neck, you can just sort of breathe in and breathe out and compensate, bring your shoulders down, take a few minutes and practice these things that we’ve learned. You’re still going to have a headache, and you’re still going to have pain, the tension is still going to be there, but these things could help to de-escalate the tension. | |

| Increased pain acceptance with decreased self-blame, guilt, and stigma | • When I used to get migraines I’d be hard on myself. I’d put a lot of blame on myself and get frustrated with myself that I had a migraine. I mean it kind of is my fault that I had a migraine but there’s not a whole lot I can do about it. But I’d get really frustrated at myself that I had another one and angry at myself that I couldn’t get rid of it and that added stress I put on myself certainly didn’t make the migraine better. So, now when I get one I’m kinder to myself I don’t blame myself because 99% of the time I don’t put myself in a situation where I know I’m going to get one. So it’s not my fault, it happens. So I’m gentler to myself and it doesn’t add stress to the migraine, so it doesn’t make it worse. So, it makes it less intense... | |

| Self-compassion during migraine attacks | • It has helped me learn to be kinder and gentler to myself when I have a migraine...when I get a migraine it’s very easy to get frustrated with myself and be hard on myself because of it. Almost to the point where you blame yourself. This has helped me just be gentler with myself when I get one, which makes them easier to deal with. | |

| Table 4B: Altered Relationship to Migraine Disease after Learning Mindfulness | ||

| Improved Emotion Regulation of Migraine Disease | Migraine acceptance | • [I learned to] “Let it be.” Things are going to be what they are in the past, in the moment, in the future. And so, stressing about the past changes nothing, stressing about the future might change something, but probably not, and stressing in the moment just takes you out of that present moment and out of enjoying yourself. So, adding that onto headaches, [I now realize] I shouldn’t be stressed or upset with myself about having a headache the day before, or if my head hurts now, being like “Oh no my head hurts now it’s going to become a headache,” that’s only going to get me worked up and it’s not going to impact anything. So just really being able to accept things as they are and not react to everything and just kind of accept it and be like, “okay this is okay.” That has been really helpful to me and I think that is kind of why I am not feeling as many headaches, I’m not getting as worked up on the inside to create the headache. |

| Hope and empowerment | • I think that since I have learned these exercises and being mindful...my perspectives and my life in general has changed that I have a more positive outlook and there is hope and I know now that things can be different and I am not wallowing in pain and it is a bad place to be and things are not going to change....and now I am able to see things around me and enjoy things around me...and so as a person I am someone who is more inviting because when you are in pain you don’t want to talk to anybody and nobody wants to talk to you so now I think I am more open... | |

| Improved self-efficacy | • II absolutely think there’s a mind-body connection. I mean I thought it anyway, but even more so now...a lot of it is related to the stress and tension and those sort of things and also how you think about the illness...and if you have a different view of it and that it can get better and you do have some control over it as opposed to “no, I just have to wait for something or somebody else to heal me.” Then you put the control back in your hands and you do have the ability to change the outcome. | |

| Increased Understanding of Migraine and Stress | Heightened awareness of migraine and stress relationship | • I think your migraines come from stress and worry...[meditation] literally just pulls that stress out and away. Just sends it away, whereas before it’s like crap my head is starting to hurt, let’s just get to the medicine cabinet, take something keep going. You’re still stressed, your mind is still there and what this has done is I think about it, fix it, and then send it away. |

| Improved ability to manage stress and migraine | • I really enjoyed this...it helped me cope with my stress level. In the past two months I’ve had a lot of things happening in my life that caused stress to increase drastically. It helped me deal with my stress in terms of being more calm, techniques I learned for relaxation, the meditation and yoga helped me to reduce my stress level and reduce my migraines by 40%. I used to get them 2–3 times a week, now I get them twice a month. | |

Table 5:

Infusion of Mindfulness Skills in Daily life with Increased Awareness of External (5A) and Internal (5B) Experiences

| Table 5A: Increased Awareness of External Experiences after Learning Mindfulness | ||

|---|---|---|

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations |

| Increased Awareness of Self & Relationship to World | Meta-awareness: Observation of external world separate from self (“self as an observer”) | • [I’m] much more aware about where I am any time, even [at] home, at work, out driving, in public. I went shopping on Memorial Day and there were mobs and mobs of people...I was observing how chaotic it was. I had to stand in line for a dressing room and I was like “this is very interesting”...! didn’t get upset about anything. I just made my choices about whether to stay or not, and I just dealt with it that way. |

| Broader life perspective | • “What is it that you absolutely have to do? What is it that you need to let somebody else do? What is it that you don’t need to deal with?”...that’s how I started looking at things, and it made my plate much smaller in terms of the things I had to deal with...So, I mean, life is different, but it’s the same work...just doing things differently or perceiving them differently and realizing that I don’t have to deal with all the stuff that I was turning into stress. It’s just made everything much nicer. | |

| Non-reactive awareness through decentering and re-perceiving | • It’s made me more mindful or more aware of things...[I learned that] when you’re mindful of things, you’re mindful of unpleasant things too, not just the good things....it has helped me identify...problems [I’ve] been avoiding...It has given me a chance to really dissect those problems and see where I’m a problem. Is my perception part of the problem and if I don’t think I can do something about that problem, can I change the way I react or respond to that problem. | |

| Increased Awareness of Sensory Input | Heightened awareness and appreciation of nature | • I think you become more mindful of yourself and [what’s] around you. I’ve been walking in a park for 6 years. After this walking meditation, I couldn’t believe how many sounds there were. And I didn’t notice them before. I didn’t hear all of these birds. They have always been there, so it was a real moment for me. Wow, what a real difference, what else did I miss? |

| Heightened exteroceptive (e.g., audio, visual, olfactory) sensory awareness | • Sounds are louder than normal [when I’m practicing mindfulness meditation]. Someone opened the door, and it sounded like they were slamming it. Even smell too. It was heightened. | |

| Table 5B: Increased Awareness of Internal Experiences after Learning Mindfulness | ||

| Increased Present Moment Experience | Decreased auto-pilot mode | • I think it does help you focus better because you slow down. You’re not automatic... you don’t just go through the motions of doing as much as you can as fast as you can. You just slow down. [You] mindfully think about and focus on the task you are doing and not thinking about what you need to be doing 10 minutes from now. |

| Breath as an anchor leads to non-reactivity | • I am thinking and I’m stopping, and I’m choosing now to just take a breath. And that’s helping me to not just react. It helps me to put things in perspective. That’s helping me, not just with my headaches, but with anything that’s going on. Even if it’s not a headache day, I am able to manage the day better, I am able to communicate more effectively with whoever it is I’m dealing with because I’m taking that breath, that pause. And it is becoming more automatic. I find myself now taking a breath without even thinking about it. | |

| Increased Interoceptive Awareness: Awareness of the Body, Thoughts | Increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals with embodied awareness | • I definitely feel like, I find myself in moments, and I am in a situation I hate, in a plane, and I notice...“I am alright.” I find myself noticing...how I feel on a more regular basis than I did before. Outside and in my body. Usually I would only do that if I had a pain. Now, after exercise, I feel great right now...Wow! I am noticing that more in general. |

| Meta-cognition: awareness of thoughts separate from self | • [Mindfulness] lets me know that just because a thought comes into my head, I don’t have to think about it—I can let it go. Where before, especially if something negative had come into my mind, I would have worried about it and now I feel free to say, “you know I don’t have to think about that right now,” I can just let it go. | |

| Increased Emotion Regulation | Improved emotional insight | • I think that I’ve been a lot, I don’t know necessarily happier, but just more aware. I have been more perceptive of my mood. So not being like “I’m upset I don’t know why,” but understanding why and then after being able to understand, then being able to go back to a more neutral or positive mood. |

| Downregulation of emotional reactivity | • [I learned to see] things happen as they are. Just being aware of it but not necessarily having an emotional response to it. Not necessarily trying to fix it, especially if it’s someone else’s reaction that I can’t change but I don’t have to react to their reaction. | |

| Earlier stress-body awareness with sensitivity to stress interoceptive signals | • I think in the past I would notice stress, now I am noticing the ramp up time, so now there is time to interfere with it and stop it. The early stages of stress for me feel like too much. I notice that now...It is really about stopping yourself before it’s too much to come down from. Manage it before it gets to that intense level... | |

| Improving stress response through awareness | • I know I won’t be [able to] eliminate all the stress out of my life but I can control some of it...I remove myself from situations until I can get my grasp on what I can and can’t control in that situation. Even at work I’ll remove myself from situations because a lot of the stress is [at work] and I carry that stress over to home, which I didn’t realize I was doing. | |

| Increased Non-Judgmental Attitudes | Self-acceptance through non-judgement | • There should be no judgment on ourselves. I’m very hard on myself...people pleaser, you hear those negative thoughts in your head all the time, “You’re not good enough, you’re a burden, you’re too challenging, you’re too needy, you’re all these things” and standing back and reflecting and saying [instead], “Be nice to yourself, don’t judge yourself as harshly as you do”...just having 8 weeks to focus on that and think about that gives you a little bit more confidence. |

| Acceptance of life stressors | • Like I said, my stress level hasn’t changed in my external life, and I’m glad so I could see the impact [of the course]. I’m noticing even though the same stresses are occurring, I’m more accepting of them...I am not fighting them as much. I feel like my reaction has softened to the world. | |

| Increased self-compassion | • I’ve always been good to other people but not so good to myself so I’m getting better at that. I say [to myself] “hey you’re happy, you look better than you did, you got a sparkle in your eye, you walk a little bit more confident.” | |

Table 6:

Improvement in Overall Well-being

| Improvement in Emotional Well-Being | Enjoyment and happiness | • I think I’m a happier more pleasant person because of it—I think being mindful of the situation you’re in whether it’s at work...I think I’m more engaged with them...I’m paying attention to things a lot more which makes me happier. |

| Equanimity (mental calmness, ability to relax) | • [I now have a] sense of stillness, calm, well-being, a sense of protection. Whatever happens matters, but it isn’t going to be the end of me. [I now have] a sense of being protected. | |

| Improved depressive symptoms | • It’s really shown me how to have strength in everyday and techniques to help pull me through those days as it may not be a happy day, I call them blue days. And blue days can lead to headaches if you’re not careful. And this provided strategies to help through those blue days. • Stress will kill you and emotions will kill you and anxiety will kill you and I’ve experienced depression, suicide attempts and all those things when you’re in a dark hole it’s so hard to climb out of [it] and I think this approach has supported the growth that I’ve needed as I have been progressing in my healing...that focus positively inward instead of all the negative that I’ve been pulling inward...I find [it] a great benefit. |

|

| Improved anxiety | • With the mindful meditation and movements and mindful thinking, I think that’s helping my stress level, helping my anxiety, helping me to focus on me and not so much [on] the stressors that are around me. And that’s something I don’t do a lot of, think about me...[this has had] a great benefit even more so than just going to the gym and lifting weights because [in the gym] you’re focusing on your body but you’re not focusing on your mind. | |

| Prioritizing and accepting time for self-care | • I think the course forced me in a way to do more self-care...to acknowledge, “okay no you don’t need to mop the floor today. It doesn’t need to get done, it’s not the end of the world.” Those little things here and there to you know take time for yourself. Take time to do this meditation practice. | |

| Increased Cognitive Well-being | Awareness of mind-body integration | • I definitely think when you get healthier mentally, it starts to affect you physically. Like when you start thinking about how can you get...healthier mentally you start looking at the physical aspect of yourself. |

| More focused, able to think more clearly | • I think it helps to clear the head, you know clear the mind and help refocus the energy...Life is busy, there’s a lot going on, there’s a lot of pressure. [Mindfulness] definitely kind of lifts that and moves it out of the way and allows me to just think more clearly in that moment...when I’m I come out of [meditating] I have more energy. I feel better. I’m more conscious and present. | |

| Improved Social Well-Being: Enhanced Relationships | Increased empathetic understanding and emotional literacy | • Just how I perceive certain things [has changed] like my relationship with my boyfriend and looking at things a little bit differently, like an argument we had or whatever, trying to see things from his perspective instead of just how I feel...really trying to look at things differently has helped. I feel like certain relationships are less stressful now because of that. |

| More patience with self and others | • I think I’m more patient now with my kids. That’s a benefit for them too. I [also] think I’m more patient with myself...I think my whole demeanor in general is just calmer than it was before. [Mindfulness] just changes the way you look at anything. | |

| Improved listening skills | • There are specific parts of my job that require me to listen and since this practice, since this training, I have learned to listen more and speak less...One patient said to me, “I really appreciate the fact that you took the time to just listen to what I had to say,” and that to me was validation. | |

| Improved relationships through decreased reactivity | • I think that...personally it has enhanced my personal relationships at home...I feel that I am not as stressed...[I am now] able to embrace the chaos without getting pulled into it and let it play out...this class has changed my demeanor...[which] affects the people in my house as well...because now they are not as dramatic...I am compassionate and kind most of the time...but since the class I have been able to catch myself when I am going to cross my line and not be so nice and be mindful. Because of practicing this you are able to pull back and say wait that is not nice. | |

| Meaningful Behavior Changes | Improved eating and drinking habits | • I eat less junk...when we started doing like mindful eating, that’s when I started thinking “wait did I really eat that much today?” or “can I have that much of this?” or you know “if I want to be a little bit healthier...do I need to eat this?” |

| Improved activity level | • Instead of just sitting on the couch I’m trying to be more involved in in my son’s playtime, I’m trying to get in the extra steps here and there, parking a little further away or walking to certain places that I used to not walk to or even though it’s really cold right now I’ve been trying to get more outdoors...I am trying to be more aware of being less stagnant. | |

| Improved sleep hygiene | • The sleep has improved so much...I’m eating better, sleeping better, and feeling better, which is great. I really enjoyed [the class]. |

We created a conceptual model (Figure 1) of proposed relationships between the observed effects of learning mindfulness through MBSR in patients with migraine. We hypothesized that the newly learned MBSR skills led to an infusion of mindfulness into daily life, resulting in both an altered pain experience and migraine experience, ultimately resulting in improved overall well-being. The therapeutic benefits of the group experience may be moderating these effects. Additionally, the improvement in well-being may have resulted directly from, and created a positive feedback loop to, the infusion of mindfulness into daily life.

Figure: Conceptual Model of Proposed Relationships of Observed Effects of Themes and Subthemes of Learning Mindfulness through MBSR in Patients with Migraine.

MBSR skills learned through experiential practices and group discussions led to an infusion of mindfulness skills in daily life (Table 5) that resulted in altered pain experience seen through experimental heat pain testing (Table 3) and altered migraine experience through altered response to attacks and altered relationship to migraine disease (Table 4), ultimately leading improved overall well-being (Table 6). Additionally, the improvement in well-being may have resulted directly from, and created a positive feedback loop to, the infusion of mindfulness into daily life. The therapeutic benefit of the group experience of learning mindfulness in patients with migraine (Table 7) may moderate these effects. The main findings and the themes of each table of the manuscript are represented below the conceptual model. MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction.

Themes and Subthemes

After learning mindfulness, participants’ experience during heat pain testing changed, with alterations in pain perception and decreased reactivity to pain (Table 3). In addition, participants had a better understanding of their migraine pain and of the differentiation between pain intensity and unpleasantness through heat pain testing (Table 3).

Participants’ response to migraine attacks changed through increased interoceptive awareness (conscious perception of internal body sensations)25 and improved emotion regulation during migraine attacks (Table 4A). Specifically, increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals led to earlier awareness of migraine attacks, which altered medication use. Participants used mindfulness as both an acute and prophylactic migraine treatment, allowing them to take medications earlier or avoid them altogether. Learning mindfulness led to using the breath as an anchor during migraine attacks and life challenges. Mindfulness helped participants acknowledge and accept the pain during an attack. Increased interoceptive awareness of stress sensations in the body may have allowed for mindfulness to be used to alter progression of migraine attacks. Improved emotion regulation during migraine attacks led to increased awareness of and less: fear of migraine, pain catastrophizing, anticipatory anxiety, and reactivity to pain. Participants experienced self-compassion during attacks and increased pain acceptance with less self-blame, guilt, and stigma.

Learning mindfulness also altered the relationship to migraine disease through increased emotion regulation with migraine acceptance, hope, empowerment, and self-efficacy (Table 4B). An increased understanding and awareness of the relationship between migraine and stress developed, possibly resulting in an improved ability to manage both stress and migraine (Table 4B).

Learning mindfulness increased awareness of external experiences (Table 5A). An increased awareness of self and relationship to the world allowed for development of meta-awareness, with observation of the external world as separate from oneself (e.g., “self as an observer”). Participants gained broader life perspectives and non-reactive awareness through decentering and re-perceiving (separating oneself from one’s thoughts with better clarity of experiences in the moment).26 Participants experienced increased awareness of sensory input seen through heightened nature awareness and appreciation. Heightened exteroceptive (e.g., audio, visual, olfactory) sensory awareness also occurred.

Mindfulness also increased awareness of internal experiences (Table 5B) in the present moment, decreased auto-pilot mode, and increased the use of breath as an anchor leading to non-reactivity. Interoceptive awareness of the body and thoughts developed with increased sensitivity to interoceptive signals with embodied awareness and meta-cognition (awareness of thoughts as separate from self). Emotion regulation improved, with enhanced emotional insight, downregulation of emotional reactivity, earlier stress-body awareness (with sensitivity to stress interoceptive signals), and improved stress response. Non-judgmental attitudes, such as self-acceptance, acceptance of life stressors, and self-compassion, also increased.

Mindfulness improved overall sense of well-being (Table 6). Improvement in emotional well-being was seen through enjoyment and happiness, equanimity (mental calmness and ability to relax), improved depressive symptoms and anxiety, and prioritizing and accepting time for self-care. Increased cognitive well-being was seen through awareness of mind-body integration and being able to think more clearly. Social well-being improved with enhanced relationships, as empathetic understanding and emotional literacy improved. Participants reported being more patient with themselves and others as well as improved listening skills. Relationships also improved with decreased reactivity. Meaningful behavior changes were seen through improved eating and drinking habits, activity level, and sleep hygiene.

Finally, therapeutic benefits of the group experience of learning mindfulness in participants with migraine was evident (Table 7). Participants experienced feelings of decreased migraine isolation and creation of a “safe space.” The group experience enhanced mindful motivation and accountability. Shared stories led to empowerment, and the connection with others who had similar experiences fostered migraine reappraisal through understanding others’ experiences.

Discussion:

Participants with migraine who learned mindfulness techniques through MBSR developed increased mindful awareness of internal and external experiences, with shifts in pain perception and migraine experiences resulting in improvement in overall well-being. Learning mindfulness skills changed participants’ perspectives, altering their experiences with the world and with migraine attacks. Interoceptive and stress-body awareness increased, with overall improved migraine management. Improved emotion regulation around the migraine experience resulted in decreased impact of inter-ictal factors such as fear of migraine, pain catastrophizing, anticipatory anxiety, and pain reactivity. Receiving the intervention in a group context provided an opportunity for participants with migraine to connect with others experiencing similar challenges, resulting in decreased feelings of migraine isolation and increased mindfulness motivation and accountability. This study’s findings support and extend the existing literature regarding the impact and mechanisms of mindfulness on health, emotional wellness, relationships, and healthy behaviors.25–30 Our findings of improved cognitive well-being are consistent with recent MRI evidence suggesting mindfulness improves cognitive efficiency in adults with migraine.8 These qualitative findings expand our understanding of the mechanisms through which mindfulness may positively impact adults with migraine and help explain and validate our quantitative findings previously reported.9, 10

In our quantitative results, we found that mindfulness resulted in a shift in pain perception, with a 30% and 36% reduction in experimental pain unpleasantness and intensity, respectively, in participants with migraine.10 While mindfulness meditation has been shown to attenuate the subjective pain experience in healthy controls,31, 32 our research is unique in demonstrating a reduction of perception of experimentally induced pain across time in a clinical trial of a patient population with pain (e.g., migraine). Our qualitative results help interpret these quantitative findings, as participants explained how they experienced this shift in pain perception, noticing decreased reactivity to pain with use of the breath. Mindfulness impacted participants’ migraine pain experience by changing their awareness, perspective, and reactivity, leading to an improved ability to differentiate pain intensity from unpleasantness. The neural mechanisms of mindfulness-based pain relief have demonstrated that reductions of pain intensity are associated with heightened activity of the anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and the orbitofrontal cortex, while reductions in pain unpleasantness are associated with attenuated activity of the thalamus.32 These results demonstrate that mindfulness is engaged in the cognitive modulation of pain through cognitive and affective pain control and reappraisal of sensory nociceptive input.33 Further, our prior results showing that mindfulness-based pain relief is not mediated through endogenous opioids34 highlights the importance of finding the non-opoidergic pathways that could explain the full benefit of mindfulness’ impact on migraine. Ongoing research at Massachusetts General Hospital is being conducted to further evaluate the mechanisms of mindfulness meditation in patients with migraine utilizing multimodal PET/MR imaging techniques (NIH P01AT009965) to further understand how mindfulness reduces pain perception. This shift in pain perception and altered response to migraine attacks may be key factors contributing to the reductions in migraine related disability, pain catastrophizing, and depressive symptoms seen quantitatively in our clinical trials.9, 10

This study identified several new potential mechanisms of mindfulness’ effect on migraine. The increased interoceptive awareness experienced by participants led to earlier awareness of migraine attacks (e.g., during prodromal state) and triggers, resulting in earlier use of medications. Although many patients and providers may consider mindfulness as an alternative to medication, this finding demonstrates that learning mindfulness can be used as a pharmacological adjunct and may result in better medication management. For example, mindful patients may adhere better to instructions to use acute medications early during a migraine attack because of this enhanced ability to tune in and recognize symptoms of an attack earlier during the prodrome. In our study, identifying a potential migraine earlier even allowed participants to prepare for, or avoid, the attack altogether, often using breathing and relaxation techniques learned through MBSR.

Historically, increased body awareness was thought to lead to somatosensory amplification and hypervigilance towards pain, worsening anxiety sensitivity and creating a maladaptive response.25 On the contrary, our findings demonstrate that the enhanced interoceptive awareness of migraine sensory experiences, including both during the attacks and the prodrome, may be advantageous in patients with migraine. However, such increased interoceptive awareness may only be beneficial when coupled with the reduction of maladaptive responses that occurs with mindfulness, such as attenuated fear of migraine, pain catastrophizing, anticipatory anxiety, and pain reactivity. Mindfulness specifically teaches “turning towards” pain rather than away from it, encouraging awareness of different sensations with curiosity and non-judgment, ultimately allowing for cognitive pain reappraisal.30 36, 37 This increased embodied interoceptive awareness may decrease the experience commonly seen in those with chronic pain that the body has “betrayed them,”38 allowing for positive benefits of interoception.

Although this study has identified a potential impact of improved interoceptive awareness, it is unclear which mindfulness practice drives this effect in migraine. For example, while the open monitoring of mindfulness may be key, the experiential practices of focused attention on the breath versus the body scan may also be instrumental in increasing migraine interoceptive awareness.39 Interoceptive awareness localizes to the insula,39 an area of the brain considered a “hub of activity” in migraine, playing a key role in integrating many of the dynamic processes of migraine (sensory, autonomic, cognitive, and emotional).40 Further research is needed to better understand the neurophysiology underlying improved interoceptive awareness from mindfulness in migraine.

Participants described mindfulness skills as allowing them to become aware of their stress response sooner and using MBSR techniques to decrease their stress reactivity, a commonly identified migraine trigger.41 Participants highlighted how mindfulness decreased inter-ictal factors of self-blame, guilt, and stigma, while also increasing migraine acceptance, hope, empowerment, self-efficacy, and self-kindness during attacks. These factors may play a more meaningful role in individuals’ day-to-day experiences of living with migraine than previously recognized.14 While the focus in clinical trials and clinical practice is often placed on the ictal burden of migraine pain, with a specific focus on 1–10 pain ratings, mindfulness may target these other factors that contribute to significant inter-ictal disease burden. As those with migraine experience recurrent, intermittent, unpredictable attacks of pain and sensory amplification with resulting significant disability, targeting this inter-ictal disease burden is challenging, especially with pharmacological options alone. Mindfulness may thus be a valuable adjunct to help address these inter-ictal factors that contribute to significant disease disability and poor quality of life.

This clinical trial taught mindfulness as a preventive migraine strategy, as it has been most often studied.2, 8 Interestingly, many participants reported using mindfulness as an acute treatment. To date, only a few small studies have assessed and found the practice of mindfulness beneficial for acute treatment of migraine.42, 43 Psychologically focusing on the breath may physiologically activate the vagus nerve, which has been demonstrated to be an effective acute migraine treatment with the novel non-invasive vagus nerve stimulator.44 This is potentially one of the mechanisms that explains the unique benefits of mind-body modalities in migraine (e.g., yoga,45, 46 tai chi,47 etc.). Use of the breath as an anchor was reported throughout many interviews and can be found in various themes and subthemes, including improving emotion regulation, relationships, and non-reactive awareness. Breath awareness played a key role in understanding migraine and stress, helping decrease stressors by leading to earlier stress-body awareness, non-reactivity, and avoidance of medications. We recently found that slow breathing combined with attention to breath reduces pain independent of endogenous opioids,35 further highlighting the potential importance of the breath in pain reduction. Although not quantitatively assessed, our data supports beneficial effects of mindfulness as an acute treatment, demonstrating a need for further research in this area.

The group setting of MBSR allows for dialogue, inquiry, and didactic discussions, providing an opportunity to learn how to use mindfulness skills in the context of daily life experiences. Group mindfulness sessions have been found to more effectively induce a state of mindfulness and strengthen social connectivity compared to solitary sessions,48 while also providing valuable social support and perspective insight, especially when practiced among others with a shared medical condition.49 Our study identified the group experience as beneficial to connecting people with migraine to each other, decreasing migraine isolation, developing a sense of group support and empowerment, improving migraine perspective, and creating a safe space. The shared group experience also enhanced motivation and accountability for mindfulness practice and engagement. The increased interoceptive awareness that participants experienced from mindfulness may have also played a role in this enhanced social connection.50 Pain can be isolating,38 especially for those with sensory hypersensitivities that preclude full engagement in life activities, such as in migraine.14 The group-based, in-person instruction differentiates this intervention from many app-based programs that exclusively offer asynchronous learning, experiential practices, or self-management strategies. As meditation interest and online options have increased,51 especially during the COVID-19 pandemic,52, 53 understanding the value of group-based and in-person sessions is important to knowing the critical ingredients of learning, engaging with, and benefiting from mindfulness. Given that group environments are known to provide specific therapeutic benefits,54 we designed our study with an active comparator Headache Education group to account for this effect.10 Although MBSR is taught in a group setting and may be a moderator of mindfulness’ benefits seen in this study (Figure 1), our quantitative results demonstrated the impact of the mindfulness group beyond our comparator Headache Education group, suggesting the group effect was not the sole mechanism explaining clinical benefits.10 The role of the group setting in learning mindfulness with others who similarly experience migraine requires further investigation.

A multitude of prior models have been developed to understand the mechanisms of mindfulness, which are well-summarized in this review.24 Our conceptual model framework (Figure 1) organizes our main findings to better understand the major factors potentially contributing to altered pain perception and experiences with migraine attacks. These results also highlight the importance of the biopsychosocial model, with biological (awareness), psychological (well-being) and social (group) factors all playing a role in the altered pain and migraine experiences. While we demonstrated the key hypothesized relationships driving the effects seen in this research, further research will be needed to compare our model with previously developed models39 and to validate the hypothesized relationships with effect sizes of the interactions.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to use patient voices of those with migraine from their lived experiences taking a mindfulness course to develop a model for the mechanisms of mindfulness in migraine. This study has several important strengths, including a large sample of 43 qualitative interviews, obtained across two clinical trials that were conducted in two different cities across time. Participants were diagnosed with migraine by a UCNS-certified headache specialist using ICHD-diagnostic criteria. Rigorous qualitative methodology was used to effectively capture, organize, and analyze data. While previous research has hypothesized mechanisms of mindfulness through survey responses, this study captured mechanisms through the voices and lived experiences of the participants who had experientially learned mindfulness during a standardized MBSR course. The use of open-ended questions allowed for participants’ perspectives to be depicted authentically.

Limitations of this study include a non-diverse patient population, as most participants were White educated females, decreasing study generalizability. Participants in the two trials had either 4–14 or 4–20 migraine days/month, were treatment-seeking, and had baseline severe headache-related disability; therefore, the results reflect the impact of MBSR in patients with this disease burden. In the two clinical trials, 78% randomized to MBSR completed the qualitative interviews, so results only reflect responses of those who completed the interview. MBSR involves weekly group sessions with a guided teacher, and participants practiced mindfulness at home over 30 minutes per day on the days practiced; results may not generalize to other mindfulness interventions or lower dosages. Although access has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic with online class availability,53 MBSR is limited to those with the time, energy, and financial resources to pay for the sessions. Though iterative data collection would have been a helpful approach, interviews were conducted immediately after the intervention when the perspective on mindfulness’ impact may have been greatest and effects seen may wane over time. Magnitude coding was not conducted to assess the proportion of participants endorsing the various themes as our overarching goal with these analyses was to understand all potential mechanisms that could play a role of mindfulness in migraine. Future research may help identify which mechanisms may have the largest effect. Additionally, inferences about potential mechanisms are based on patient perceptions. Inter-individual differences may exist, as the role each factor plays for each person may be more, less, or not at all. Our conceptual model broadly hypothesizes the effects seen across all participants, and each person may not experience each one. Furthermore, gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other individual differences may influence the impact each factor has on mindfulness’ mechanism on migraine. We did not capture effect sizes of the different variables in the model.

In summary, we discovered new findings of the potential mechanisms of mindfulness in adults with migraine. Future research should endeavor to replicate these findings in other mindfulness-based interventions. Extending this research to diverse populations is important, with a potential to extend to pediatric populations. Empiric validation of our newly introduced conceptual model is needed, comparing it to prior models.30 In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic with elevated stress and uncertainty, mindfulness may be an especially beneficial treatment approach for those with migraine.53

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful for all the participants who volunteered for this study and provided unique insights through qualitative interviews. We are thankful for the tremendous support of Charles R. Pierce, Kate Furgurson, Geena George, and Anissa Berger, in addition to the tremendous support of a multitude of other volunteer students, including Nicole Rojas, Hudaisa Fatima, Obiageli Nwamu, MA, Vinish Kumar, Rosalia Arnolda, Paige Brabant, Danika Berman, Nicholas Contillo, Flora Chang, Easton Howard, Camden Nelson, and Carson DeLong. We are thankful of Steven Eugene Albertson’s talent for graphical design and help with our Conceptual Model Figure. We appreciate the support from the Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Developing Shared Resource of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, the Wake Forest Clinical Translational Science Institute (CTSI), the Clinical Research Unit staff and support, and the Research Coordinator Pool, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001420.

Funding:

American Pain Society Grant, Sharon S. Keller Chronic Pain Research Program, (PI-Wells); NCCIH K23AT008406 (Wells) and NINDS K23NS096107 (Seng), NCCIH R01AT011005 (Seng and Wells), NCCIH R01AT011502 (Wells), NCI R01CA266995 (Wells), American Headache Society Fellowship (Wells) and the Headache Research Fund of the John Graham Headache Center, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. Research supported in part by the Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Developing Shared Resource of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center’s NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197 and the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s NCATS Grant UL1TR001420. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- MBSR

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- ICHD

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- SD

Standard Deviation

- QST

Quantitative sensory testing

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- UCNS

United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: PE, CM, SB, RA, MS, AC, JB, NO, PG, and REW have no conflicts of interest to report. ES has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline and Click Therapeutics.

TRIAL REGISTRATIONS: clinicaltrials.gov Identifiers: NCT01545466 and NCT02695498.

References

- 1.Andrasik F, Grazzi L, D’Amico D, et al. Mindfulness and headache: A “new” old treatment, with new findings. Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache 2016. DOI: 10.1177/0333102416667023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells RE, Seng EK, Edwards RR, et al. Mindfulness in migraine: A narrative review. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2020; 20: 207–225. 2020/01/15. DOI: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1715212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald N, Lipscomb J and McCrory DC. AHRQ Technical Reviews. Resource Utilization and Costs of Care for Treatment of Chronic Headache. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US), 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Ailani J, et al. Discontinuation of Acute Prescription Medication for Migraine: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache 2019. 2019/09/24. DOI: 10.1111/head.13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]