Abstract

In many species, oocytes are initially formed by the mitotic divisions of germline stem cells and their differentiating daughters. These progenitor cells are frequently interconnected in structures called cysts, which may function to safeguard oocyte quality. In Drosophila, an essential germline-specific organelle called the fusome helps maintain and coordinate the mitotic divisions of both germline stem cells and cyst cells. The fusome also serves as a useful experimental marker to identify germ cells during their mitotic divisions. Fusomes are cytoplasmic organelles composed of microtubules, endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles, and a meshwork of membrane skeleton proteins. The fusome branches as mitotic divisions progress, traversing the intercellular bridges of germline stem cell/cystoblast pairs and cysts. Here, we provide a protocol to visualize fusome morphology in fixed tissue by stabilizing microtubules and immunostaining for α-Tubulin and other protein constituents of the fusome. We identify a variety of fluorophore-tagged proteins that are useful for visualizing the fusome and describe how these might be combined experimentally. Taken together, these tools provide a valuable resource to interrogate the genetic control of germline stem cell function, oocyte selection, and asymmetric division.

Keywords: Germline stem cell, Cyst, Oocyte, Germarium, Germline, Microtubules

1. Introduction

To build oocytes, Drosophila melanogaster germ cells develop as cysts of undifferentiated cells that remain interconnected during mitotic division [1-3] (Fig. 1a, b). Within each cyst, one cell is ultimately selected as the oocyte and the other 15 become nurse cells. The cells of the cyst remain interconnected from their initial division through the late stages of oogenesis, where nurse cells shift (“dump”) their cytoplasmic contents to the oocyte. The “nursing” mechanism of oocyte development requires that cyst cells maintain conduits between cells, called ring canals, that are initially built during cyst cell mitotic divisions. Ring canals arise due to incomplete cytokinesis at each mitotic division, manifested by cleavage furrow arrest and the subsequent formation and growth of stable structures post-mitosis that permit transport of cytoplasm and organelles [3-5]. Apart from their role in nurse cell to oocyte transport, ring canals also support cell-cell communication and oocyte specification during germ cell mitotic divisions [3-5]. The evolutionary conservation of cyst formation suggests that germ cell interconnectivity is biologically relevant, and in support of this, stable intercellular bridges are required for optimal fertility in multiple phyla [1, 5, 6]. Cyst formation has been postulated to increase cytoplasmic volume, enhance sensitivity to DNA damage, and ensure robust oocyte development [3-7].

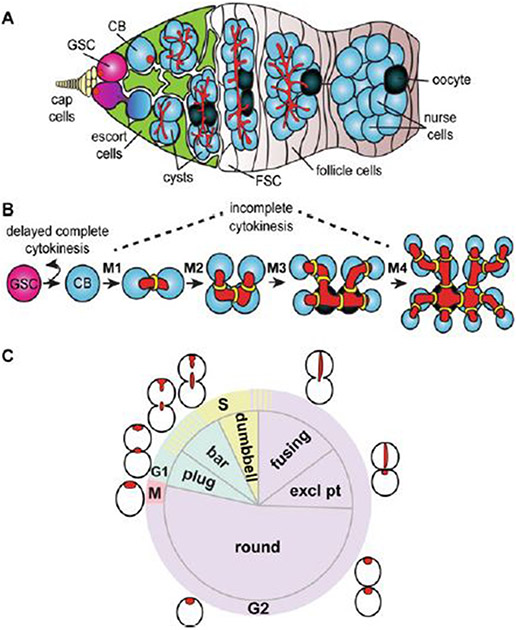

Fig. 1.

Germ cell mitotic division in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Drosophila ovaries are composed of 14 to 16 ovarioles, or strings of progressively older egg chambers. (a) Schematic of a germarium. Germline stem cells (GSCs, pink) are located at the anterior tip of the germarium, which resides at the anterior-most tip of each ovariole. GSCs lie adjacent to somatic cap cells (yellow) and escort cells (green) which support GSC self-renewal. GSC division gives rise to another GSC and a differentiating daughter cell, called a cystoblast (CB), which forms posterior to the GSC and continues to divide into 2-cell, 4-cell, 8-cell, and 16-cell cysts (blue). Within each cyst, one germ cell is specified as the oocyte (dark blue), while others become nurse cells. At the posterior of the germarium, cysts are surrounded by somatic follicle cells (tan), which descend from follicle stem cells (FSC). (b) Germ cells divide in a stereotypical fashion. GSCs undergo asymmetric mitotic divisions with complete cytokinesis, while cystoblasts divide four times (M1-M4) with incomplete cytokinesis, giving rise to the interconnected cells of the cyst. Individual cells remain connected by small ring canals (yellow), through which the fusome (red) branches. (c) Schematic diagram of the GSC cell cycle. GSCs divide approximately every 15 h; however, abscission (the final stage of cytokinesis) is delayed well into the G2 phase of the next cell cycle [9, 14, 23, 24, 26]. Fusome morphology (red) can be used for identifying GSCs generally, and more specifically, as an indirect indicator of the cell cycle stage of the GSC [9, 14, 22]. G1 gap phase 1; S synthesis phase; G2 gap phase 2; M mitosis

In Drosophila, cysts arise via four mitotic divisions of the cystoblast, an undifferentiated progenitor cell that is produced from germline stem cells (GSCs) (Fig. 1a, b). In contrast to the incomplete cytokinesis of the dividing cyst cells, GSCs produce cystoblasts via an asymmetric division with complete cytokinesis. GSCs are located at the anterior-most tip of each ovariole (the major subunit of the ovary) adjacent to somatic cap cells (Fig. 1a). GSCs divide asymmetrically every 12–15 h to maintain the GSC population while also forming the cystoblast, which is committed to differentiation [8, 9]. The switch from complete cytokinesis of the GSC/cystoblast pair to incomplete cytokinesis of the dividing cystoblast happens on a rapid timescale, suggesting tight molecular regulation.

Mitotically dividing cysts can be easily distinguished based on the prominent appearance of a germline-specific organelle called the fusome (Fig. 1a, b) [8]. A cytoplasmic vesicular organelle that most closely resembles the endoplasmic reticulum, the fusome core is composed of microtubules, the adducin-like protein Hu-li tai shao (Hts), and the membrane skeletal proteins α- and β-spectrin [10-13]. Other proteins, including cell cycle regulatory proteins and polarity factors, are transiently associated with the fusome. In dividing cyst cells, the fusome extends through ring canals, connecting the cells within a cyst [14-17]. When cells divide, the fusome also grows in a stereotypical pattern. New fusome material accumulates as mitotic spindles are disassembled, resulting in a continuously branched structure [14-17]. Like cysts, GSCs and cystoblasts also contain fusomes, sometimes referred to as spectrosomes due to their prominent dot-like morphology. Although the GSC and cystoblast fusomes are thought to be the precursors of the cyst fusomes, they differ in protein composition, morphology, and temporal dynamics [8, 11, 18]. Despite its variable composition, the function of the fusome is the same: to establish cell polarity, coordinate cyst cell communication, and promote oocyte differentiation [10, 12, 19-21].

Fixed and live-cell imaging analyses demonstrate that morphology of the GSC fusome changes coordinately with the phases of the cell cycle, as new fusome material is distributed to the daughter cystoblast [9, 14, 15, 22-24]. Importantly, delayed cytokinesis between the GSC and the nascent cystoblast keeps the pair connected via a temporary ring canal through S phase of the subsequent cell cycle (Fig. 1c) [25-27]. Through most of G1 and S phase, the GSC fusome appears as a round structure located at the posterior side of the GSC, juxtaposed to the adherens junctions which anchor the GSC to the cap cells (Fig. 1c). As the pair of cells exit S phase and proceed through G2, three events occur: the distribution of new fusome material to the cystoblast, the completion of abscission, and the assembly of the mitotic spindle in the GSC. The cystoblast fusome forms in the nascent ring canal, opposite to the original GSC fusome, as a plug of new fusome material merges with microtubule remnants from the previous cycle’s mitotic spindle. The fusome continues to grow during G2, connecting the GSC and cystoblast and forming a thick elongated structure. Abscission closes the ring canal between the two cells, separating the fusome asymmetrically (appears as an “exclamation mark” morphology). As the GSC progresses through G2, the fusome retracts into the round shape, remaining at the posterior of the cell. The round fusome then becomes the anchor point for the mitotic spindle, whose growth is facilitated by the centrosome. This allows the division plane of the GSC to divide largely perpendicular to the adjacent somatic cap cells, facilitating cystoblast formation posteriorly. Despite the well-characterized morphogenesis of the fusome, the molecular control of this process remains largely unknown.

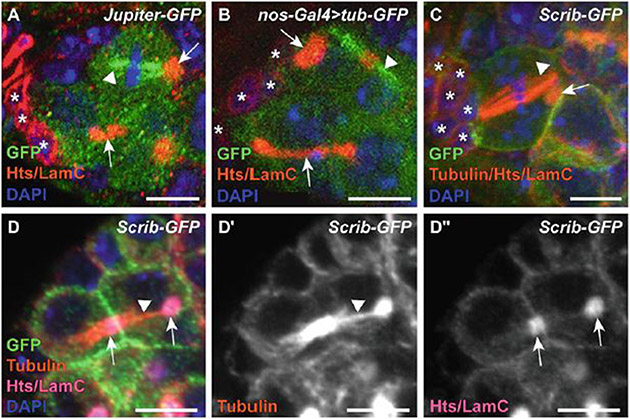

The stereotypical shape and predictable morphogenesis of the fusome, as well as the availability of excellent antisera against fusome core proteins (Hts and α-spectrin) [10, 12, 28, 29], make the fusome a highly useful experimental tool with which to monitor mitotic expansion of the germ cell pool. Here, we provide a protocol to use α-Tubulin immunofluorescence in combination with other fusome core proteins and/or GFP-tagged germ cell resident proteins to visualize GSCs and their daughters during mitotic division. Immunofluorescence for α-Tubulin works particularly well to visualize mitotic spindles and the cytoskeleton in germ cells (Fig. 2) but must be performed carefully to stabilize the microtubules through fixation. Therefore, our protocol is based on the methodology of Grieder and Spradling, who described the fixation conditions and temperature requirements necessary for optimal microtubule stabilization and immunostaining [19]. Our protocol uses Hts localization to both identify germ cells and discern fusome structure, as it works well in co-immunofluorescence with other antibodies, including α-Tubulin (Fig. 2) [12]. We also identify a variety of transgenic fly lines which are useful tools for visualizing different characteristics of GSCs or germ cells during division (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These include GFP-tagged forms of the plasma membrane-associated scaffolding protein Scribble (Fig. 2c, d”) and the microtubule-associated protein Jupiter (Fig. 2a), and a UAS-based α-Tubulin that can be driven specifically in germ cells using the nanos-Gal4::VP16 driver (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Visualizing fusome and spindle morphology. (a, b) GSCs and cystoblasts from Jupiter-GFP (a) and nos-Gal4::VP16 > tub-GFP (b) germaria immunostained for GFP (green; mitotic spindle), Hts and LaminC (LamC; red; fusomes and nuclear membrane of cap cells), and DAPI (blue; DNA). (c) GSC in metaphase of mitosis from Scrib-GFP germarium immunostained for GFP (green; cell membrane), α-Tubulin (red; mitotic spindle), Hts and LamC (red), and DAPI (blue; DNA). (d-d”) Dividing cystoblast from Scrib-GFP germarium co-immunostained for GFP (green; cell membrane), α-Tubulin (magenta; mitotic spindle remnants), Hts and LamC (red; fusome), and DAPI (blue; DNA). Images in d’-d” display Tubulin (d’) or Hts/LamC (d”) channels only. Asterisks indicate cap cells; dashed white lines indicate GSCs; arrows indicate fusomes; arrowheads indicate mitotic spindles or spindle remnants. (Images a–c were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 700 laser scanning confocal; images d-d” acquired with a Zeiss LSM 800 with Airyscan. Scale bars = 5 μm)

Table 1.

Fly stocks useful for visualizing fusome dynamics and/or microtubules in dividing ovarian germ cells

| Fluorescent marker |

Fly Stock | Description | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UASp-tubulin-GFP | P{UASp-GFPS65C-αTub84B}3 (BDSC #7373 or #7253) | Expresses N-terminal region of αTub84B with a N-terminal GFP tag under UASp control | Fusome, mitotic spindle | [19] |

| UASp-Hts-mCherry | P{UASp-hts.mCherry}attP2 (BDSC #66171) | Expresses Hts protein isoform I with a C-terminal mCherry tag under UASp control | Fusome, ring canals, plasma membrane | Tony Harris, personal communication to FlyBase |

| UASp-KDEL-RFP | P{UASp-RFP.KDEL} (BDSC #30909 & #30910) | Expresses DsRed with a N-terminal bovine preprolactin signal sequence and a endoplasmic reticulum retention signal under UASp control | Fusome, endoplasmic reticulum | Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, personal communication to FlyBase |

| Scrib-GFP | P{PTT-GA}scribCA07683 | Protein trap | Plasma membrane, fusome | [11, 30] |

| Jupiter-GFP | JupiterCPTI003917 (Kyoto #115457) | Protein trap | Mitotic spindle, cytoplasm | [31] |

| Rtnl1-GFP | P{PTT-GA}Rtnl1CA06523 | Protein trap | Fusome | [11, 13, 30, 32] |

| Par-1-GFP | P{PTT-GC}par-1CC01981 | Protein trap | Fusome | [11] |

| Fkbp14-GFP | Mi{PT-GFSTF.2} Fkbp14MI04530-GFSTF.2 (BDSC #66358) | Protein trap | Fusome, endoplasmic reticulum | [33] |

2. Materials

2.1. Fly Strains and Culture

Any Drosophila strains are conducive for visualizing fusome morphology via tubulin antibody staining, and many lines utilizing endogenous protein tags are available (some useful examples for visualizing germ cells are listed in Table 1). Standard Drosophila husbandry can be used to generate progeny with genotypes of interest. Flies can be maintained in bottles or vials on standard cornmeal/molasses/yeast media.

Wet yeast paste: used to supplement flies’ diet prior to dissection to increase ovary size aiding in the dissection process. Make a 1:1 mixture of dry active yeast and distilled water; mix until the consistency of smooth peanut butter is reached and store at 4 °C, tightly covered to prevent drying.

Dissecting microscope equipped with CO2 fly pad and tube with air needle to deliver CO2 to flies in bottles or vials.

2.2. Ovary Dissection

1.5 mL microfuge tubes pre-coated with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Add 500 μL BSA to clean microfuge tubes and incubate at room temperature on a nutating mixer for about 1 h. Pre-coating the tubes helps prevent ovaries from sticking to the sides of the tube. Pre-coated tubes can be stored at 4 °C.

Glass or plexiglass dissection dish.

Kimwipes.

Glass pasteur pipettes and bulbs.

Two pairs of #5 dissection forceps (INOX, Dumont #5, Biologie point).

Two 27 × 1¼ gauge needles with 1 mL syringes.

Nutating mixer.

Grace’s Insect Medium.

2.3. Immunostaining

15 mL and 50 mL conical tubes.

1× Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

PBS-T: 1× PBS with 0.1% Triton-X-100, store at room temperature.

Grace’s Insect Medium.

16% electron microscopy grade formaldehyde.

Pipettors and pipette tips.

Blocking reagent: 5% Normal Goat Serum (NGS) in PBS. For 50 mL, add 2.5 mL NGS to 47.5 mL PBS. Store at 4 °C; do not use if solution becomes cloudy or develops an unusual smell.

- Primary antibodies, diluted in blocking reagent (Table 2):

- Labeling endogenously tagged proteins: chicken anti-GFP (1:2000 dilution).

- Cell membrane and fusome marker: mouse anti-Hts (1:10 dilution).

- Nuclear envelope marker: mouse anti-LaminC (1:100 dilution).

- Microtubules and fusomes: anti-α-Tubulin-AlexaFluor555 (1:200 dilution).

Table 2.

Antibodies useful for visualizing the fusome and/or microtubules in dividing ovarian germ cells

| Antigen (Host Species) |

Vendor (Catalog) |

Description | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hts (mouse) | DSHB (1B1) | Monoclonal antisera | Fusome |

| LaminC (mouse) | DSHB (LC28.26) | Monoclonal antisera, useful for identifying cap cells | Nuclear envelope |

| α-Spectrin (mouse) | DSHB (3A9) | Monoclonal antisera | Fusome |

| α-Tubulin-AF555 (mouse) | Millipore (#05-829-AF555) | Directly conjugated monoclonal antisera (clone DM1A), can be purchased with AlexaFluor-555 or AlexaFluor-488 | Fusome, mitotic spindle |

| GFP (chicken) | Abcam (ab13970) | Polyclonal antisera, useful for marking GFP-tagged transgenes (see Table 1) | Variable |

| dsRed (rabbit) | Clontech / Takara (632496) | Polyclonal antisera, useful for marking mCherry- and RFP-tagged transgenes (see Table 1) | Variable |

DSHB Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank

-

6.Secondary Antibodies, diluted 1:200 in blocking reagent from a stock solution in which the product obtained from the manufacturer was diluted 1:1 with 100% glycerol, conjugated with an AlexaFluor of interest and matching the host species of the corresponding primary antibody. For example:

- GFP: goat anti-chicken-AlexaFluor488

- Hts + LaminC: goat anti-mouse-AlexaFluor633

-

7.

4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI): dilute 5 mg/mL DAPI stock 1:500 in 0.1% PBS-T; store at 4 °C in dark.

-

8.

Grace’s Medium.

-

9.

Mounting medium (see Note 1).

2.4. Sample Mounting and Microscopy

Kimwipes.

Glass Pasteur pipettes and bulbs.

Fine dissection tools for ovary mounting (forceps and needles).

Glass microscope slides and coverslips.

Mounting media (see Note 1).

Steel weight, measuring approximately 250 g.

Fingernail polish (clear or colors) to seal slide (if necessary).

Laser scanning confocal microscope with a 63× oil immersion lens.

Image acquisition and analysis software (ex. Zeiss Zen Blue, Zeiss Zen Black, Imaris).

3. Methods

3.1. Fly Preparation

Use standard Drosophila husbandry to rear flies and/or cross fly lines under UAS control with a Gal4 driver. For analyses of GSCs and their dividing daughters, nos-Gal4::VP16 is a convenient driver [34]. After 2–3 days of egg laying, remove parents to a new vial, such that only eclosing progeny will be collected for dissection. Progeny takes approximately 10 days to eclose when reared at 25 °C.

Age-match flies and feed wet yeast paste (changed daily) prior to dissection. Age, diet, temperature, and genetic background all impact cell cycle dynamics in GSCs; therefore, it is imperative to control these variables.

3.2. Ovary Dissection

Remove Grace’s Medium, formaldehyde, and 1.5 mL microfuge tubes precoated with BSA from refrigerator. Allow these to come completely to room temperature (RT).

Mix fixative. For each batch of flies to be dissected, add 700 μL Grace’s Medium plus 400 μL 16% formaldehyde. Keep fixative at RT (do NOT put in ice bucket) to preserve microtubules during fixation.

Dissect 10–15 pairs of ovaries in Grace’s medium in glass or plastic dissecting dishes, using needles to break open the outer layer of muscle around each ovariole. Teasing apart ovarioles helps fixative and antibodies to reach all germaria and egg chambers more equivalently (see Note 2).

Remove BSA from pre-coated microfuge tube using a glass Pasteur pipet.

Add your dissected ovaries in Grace’s medium to the pre-coated microfuge tube using the same glass pipet from step 4 above. Do NOT put tubes on ice.

3.3. Immunostaining

Although there are a variety of ways to utilize immunofluorescence to visualize mitotically active GSCs and germ cells in the germarium, the method below specifically uses four-color immunofluorescence to simultaneously visualize microtubules, a GFP-tagged protein of interest, the fusome, and the DNA-binding fluorescent dye DAPI to provide a comprehensive view of GSCs as they divide (examples are shown in Fig. 2). It is incredibly useful to co-label anti-α-Tubulin, anti-Hts, and anti-LaminC to visualize microtubules, the fusome core, and the nuclear lamina of both the GSCs and the neighboring cap cells, respectively. Labeling the cap cells provides a reliable way to identify GSCs and their dividing daughters within the context of the cellular microenvironment of the germarium [14, 22]. The challenge to this approach is that available antibodies are frequently raised in the same species, precluding clear discrimination of proteins. For example, available anti-Tubulin, anti-Hts, and anti-LaminC are all mouse monoclonal antisera (see Table 2). To work around this limitation, we altered the original protocol of Grieder and Spradling [19] to layer antibodies onto the tissue (see Note 3). Below, we describe the protocol to visualize germ cells using anti-Hts to label fusomes, anti-LaminC to label nuclear membranes of cap cells, anti-GFP to label the plasma membrane (using Scrib-GFP; see Table 1), and anti-α-Tubulin antisera that is directly conjugated to a stable fluorophore (AlexaFluor555) to visualize the dynamic movements of microtubules (Fig. 2c, d). We group anti-Hts and anti-LaminC (both mouse monoclonals) onto the same wavelength/channel using anti-mouse-AlexaFluor633, as their intracellular distributions are largely distinct.

This protocol could be modified to visualize fusomes and microtubules with other GFP- or RFP/mCherry-tagged proteins (endogenous or via the UASp/Gal4 system) by simply substituting secondary antibodies conjugated with different fluorophores (see Table 1 for some useful fly lines for visualizing fusomes). Alternatively, Tubulin can also be visualized in two- or three-color immunofluorescence using an endogenously tagged Jupiter-GFP (Table 1 and Fig. 2a), or by expressing UASp-Tubulin-GFP specifically in germ cells using the nos-Gal4::VP16 driver (Table 1 and Fig. 2b).

Until the addition of primary antibody, all reagents are brought to room temperature on the day of the experiment, and blocking, rinses, and washes are performed at room temperature, unless otherwise noted. When discarding the previous solution, we always keep ~100–200 μL of liquid on the ovaries to keep the tissue from drying out. In our hands, we reduce background fluorescence by layering primary antibodies onto samples one at a time in sequence, separated by extensive washing in detergent and incubation overnight or over two nights at 4 ° C. For other antibodies or tagged proteins, the exact sequence should be tested experimentally. Secondary antibodies against different species (i.e., anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor568 plus anti-chicken-AlexaFluor488) can be combined; however, the directly conjugated anti-α-Tubulin should be independently added last to prevent cross-labeling by the other anti-mouse secondary antibodies.

Remove all except ~100–200 μL of Grace’s medium from each tube of dissected ovaries. Add 1000 μL fixative to each sample and fix on nutator at RT for exactly 10 min.

Quickly remove fixative to appropriate formaldehyde waste container using a 1000 μL pipettor.

Quickly add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Invert tube 4–5 times to rinse fixative off ovaries.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Remove liquid to appropriate formaldehyde waste container using a 1000 μL pipettor.

Add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample and wash for at least 10 min on a nutator.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Remove liquid to appropriate formaldehyde waste container using a 1000 μL pipettor.

Repeat steps 5–6 twice (totaling one “rinse” and three longer “washes”).

Add 1000 μL blocking reagent to each sample. Block for at least 30 min on a nutating mixer at RT.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the blocking solution.

Add 400–500 μL of chicken anti-GFP (diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution) to each microfuge tube. Incubate in primary antibody on a nutator at 4 °C overnight.

The next day, allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Discard the first primary antibody and add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Wash for at least 30 min on a nutator.

Discard the wash solution and repeat three more times with fresh wash solution (totaling four “washes”).

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the last wash.

Add 400–500 μL of a primary antibody solution containing mouse anti-Hts (1:10) and mouse anti-LaminC (1:100), diluted together in blocking solution, to each microfuge tube. Incubate in primary antibody solution on a nutator at 4 °C over two nights.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Discard the second primary antibody and add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Wash for at least 30 min on a nutator.

Discard the wash solution and repeat three more times with fresh wash solution (totaling four “washes”).

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the last wash.

Add 1000 μL blocking reagent to each sample. Block for at least 30 min on a nutating mixer at room temperature.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the blocking solution.

Add 400–500 μL of a secondary antibody solution containing goat anti-chicken-AlexaFluor488 (1:200) and goat anti-mouse-AlexaFluor633 (1:200), diluted together in blocking solution, to each microfuge tube. Incubate in the secondary antibody solution for 1–2 h at RT on a nutator. From this point forward, samples should be covered in tinfoil as much as possible to prevent fluorescence bleaching.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Discard the secondary antibody solution and add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Wash for at least 30 min on a nutator.

Discard the wash solution and repeat three more times with fresh wash solution (totaling four “washes”).

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the last wash.

Add 400–500 μL of anti-α-Tubulin-AF555 (1:200) diluted in blocking solution. Incubate in this third primary antibody solution on a nutator at 4 °C overnight (see Note 4).

The next day, allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Discard the antibody and add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Wash for at least 30 min on a nutator.

Discard the wash solution and repeat three more times with fresh wash solution (totaling four “washes”).

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes and discard the last wash.

Add 400–500 μL DAPI diluted in blocking solution. Incubate at RT for 15 min on a nutator.

Allow ovaries to sink to the bottom of the microfuge tubes. Discard the DAPI solution and add 1000 μL PBS-T to each sample. Wash for at least 10 min on a nutator.

Discard the wash solution and repeat three more times with fresh wash solution (totaling four “washes”).

Remove the last wash and add 2–3 drops of mounting medium (see Note 1). Store at 4 °C in dark until ready for mounting on slides.

3.4. Microscopy

Use a glass pipette to move ovaries and mounting media from tube to a glass slide. Remove enough mounting media from the slide such that ovarioles no longer float.

Use fine dissecting tools (needles, tungsten wire, and/or forceps) to separate ovarioles from each other and remove egg chambers larger than stage 9. These steps help to reduce the thickness of the ovariole such that germaria can be more clearly imaged (see Note 5).

Once the ovarioles are spread across the slide, add 1–2 drops of mounting medium to prevent air bubbles forming between ovarioles. Carefully place a #1.5 glass coverslip on top of the media in the center of the slide and allow mounting media to spread over ovarioles by capillary action (see Note 6).

Flatten coverslip onto glass slide for 2–5 min. This is most easily accomplished by placing the slide onto a clean kimwipe. Then assemble a weight apparatus composed of a kimwipe, an inverted cardboard box top, and a steel weight. Carefully place the weight apparatus on top of your slide, being cautious not to let the coverslip move on the slide (see Note 7).

After your slide has been flattened, seal the edges of the coverslip to the slide using fingernail polish. Allow slides to dry for at least 1 h before imaging.

Use a confocal microscope with a 63× oil immersion lens to image samples. We use an inverted laser scanning confocal (Zeiss LSM700 or LSM800) capable of adding an optical zoom of at least 2.0× (and up to 6.0×). Images are collected as z-stacks with anywhere from 0.25 to 1.0 μm optical step size (see Note 8).

4. Notes

We have used both homemade and commercially available mounting media with great success. For a relatively cheap version that works well with long shelf-life, we use 20 n-propyl gallate in 90% glycerol. To create this solution, mix 1.0 g n-propyl gallate and 5 mL of PBS in a 50 mL conical and vortex to mix; add 45 mL of 100% glycerol to conical and wrap in tinfoil to keep solution in dark; nutate overnight at room temperature; store at 4 °C in dark. Alternatively, the commercially available Vectashield Vibrance is a setting formulation antifade mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, H-1700). Slides mounted with this medium can be imaged with no altered fluorescence brightness for more than one week after mounting, if kept stored at 4 °C. See manufacturer’s instructions for additional details.

Be sure to thoroughly tease apart ovaries as no permeabilization step is present.

In general, for triple or quadruple labeling, we apply primary antibodies first in sequence (each incubated overnight at 4 °C), then combine species-specific secondary antibodies in the same solution. Since the fluorophore-conjugated α-Tubulin antibody is also a mouse antibody, this allows independent analysis of the Hts or α-spectrin proteins and α-tubulin in different fluorescence channels. An important note: for immunostaining with α-Spectrin antibodies, we substitute Tween-20 for Triton in all solutions.

Samples can be incubated in the fluorophore-conjugated α-Tubulin antibody for as little as 20 min in dark at RT, but leaving the antibody on the tissue at 4 °C overnight results in brighter staining intensity.

It is important to remove late-stage egg chambers (typically everything after stage 9). Removing these large egg chambers allows high-quality images to be produced, as the cells of the germarium are all in the same optical plane. Leaving the large egg chambers on the slide allows room for germaria to move around on the slide. This movement can negatively affect image quality.

If mounting media does not reach edges, extra can be added around the edge of the glass coverslip using a pipette and allowing capillary action to bring the mounting medium under the coverslip.

Place the lid of a cardboard microscope slide box on top of a folded kimwipe and place a steel weight in the middle of this box. Then set the weight/kimwipe/box apparatus on top of the coverslip. This helps to evenly distribute weight resulting in equally flattened ovarioles for optimal imaging.

With smaller optical sections, a more cohesive three-dimensional image can be created in post-processing, allowing more sophisticated quantitative analyses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of the Drosophila community for sharing reagents and protocols and to members of the Ables lab past and present for helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R15-GM117502 (E.T.A.) and an East Carolina University Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity Award (A.E.W.).

References

- 1.Lu K, Jensen L, Lei L, Yamashita YM (2017) Stay connected: a germ cell strategy. Trends Genet 33(12):971–978. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matova N, Cooley L (2001) Comparative aspects of animal oogenesis. Dev Biol 231(2):291–320. 10.1006/dbio.2000.0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepling M, Lei L (2018) Germ cell nests and germline cysts. In: Skinner MK (ed) Encyclopedia of reproduction, 2nd edn. Academic Press, Oxford, pp 159–166. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64710-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Cuevas M, Lilly MA, Spradling AC (1997) Germline cyst formation in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet 31:405–428. 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haglund K, Nezis IP, Stenmark H (2011) Structure and functions of stable intercellular bridges formed by incomplete cytokinesis during development. Commun Integr Biol 4(1):1–9. 10.4161/cib.4.1.13550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell JM, Pepling ME (2021) Primordial follicle formation - some assembly required. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res 18:118–127. 10.1016/j.coemr.2021.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita YM (2018) Subcellular specialization and organelle behavior in germ cells. Genetics 208(1):19–51. 10.1534/genetics.117.300184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinnant TD, Merkle JA, Ables ET (2020) Coordinating proliferation, polarity, and cell fate in the Drosophila female germline. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:19. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villa-Fombuena G, Lobo-Pecellín M, Marín-Menguiano M, Rojas-Ríos P, González-Reyes A (2021) Live imaging of the Drosophila ovarian niche shows spectrosome and centrosome dynamics during asymmetric germline stem cell division. Development 148(18). 10.1242/dev.199716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Cuevas M, Lee JK, Spradling AC (1996) alpha-spectrin is required for germline cell division and differentiation in the Drosophila ovary. Development 122(12):3959–3968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lighthouse DV, Buszczak M, Spradling AC (2008) New components of the Drosophila fusome suggest it plays novel roles in signaling and transport. Dev Biol 317(1):59–71. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H, Yue L, Spradling AC (1994) The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development 120(4):947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Röper K (2007) Rtnl1 is enriched in a specialized germline ER that associates with ribonucleoprotein granule components. J Cell Sci 120(Pt 6):1081–1092. 10.1242/jcs.03407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Cuevas M, Spradling AC (1998) Morphogenesis of the Drosophila fusome and its implications for oocyte specification. Development 125(15):2781–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huynh J-R (2006) Fusome as a cell-cell communication channel of Drosophila ovarian cyst. In: Cell-cell channels. Springer, New York. 10.1007/978-0-387-46957-7_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch EA, King RC (1966) The origin and early differentiation of the egg chamber of Drosophila melanogaster. J Morphol 119:283–303. 10.1002/jmor.1051190303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong SK, Tan C (2010) Germline cyst formation and incomplete cytokinesis during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. Dev Biol 337:84–98. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKearin D (1997) The Drosophila fusome, organelle biogenesis and germ cell differentiation: if you build it. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 19(2):147–152. 10.1002/bies.950190209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grieder NC, de Cuevas M, Spradling AC (2000) The fusome organizes the microtubule network during oocyte differentiation in Drosophila. Development 127(19):4253–4264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snapp EL, Iida T, Frescas D, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Lilly MA (2004) The fusome mediates intercellular endoplasmic reticulum connectivity in Drosophila ovarian cysts. Mol Biol Cell 15(10):4512–4521. 10.1091/mbc.e04-06-0475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue L, Spradling AC (1992) hu-li tai shao, a gene required for ring canal formation during Drosophila oogenesis, encodes a homolog of adducin. Genes Dev 6:2443–2454. 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ables ET, Drummond-Barbosa D (2013) Cyclin E controls Drosophila female germline stem cell maintenance independently ofits role in proliferation by modulating responsiveness to niche signals. Development 140(3):530–540. 10.1242/dev.088583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinnant TD, Alvarez AA, Ables ET (2017) Temporal remodeling of the cell cycle accompanies differentiation in the Drosophila germline. Dev Biol 429(1):118–131. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao SH, Tseng CY, Wan CL, Su YH, Hsieh CC, Pi H, Hsu HJ (2015) Aging and insulin signaling differentially control normal and tumorous germline stem cells. Aging Cell 14(1):25–34. 10.1111/acel.12288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathieu J, Cauvin C, Moch C, Radford SJ, Sampaio P, Perdigoto CN, Schweisguth F, Bardin AJ, Sunkel CE, McKim K, Echard A, Huynh JR (2013) Aurora B and cyclin B have opposite effects on the timing of cytokinesis abscission in Drosophila germ cells and in vertebrate somatic cells. Dev Cell 26(3):250–265. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathieu J, Huynh JR (2017) Monitoring complete and incomplete abscission in the germ line stem cell lineage of Drosophila ovaries. Methods Cell Biol 137:105–118. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2016.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matias NR, Mathieu J, Huynh JR (2015) Abscission is regulated by the ESCRT-III protein shrub in Drosophila germline stem cells. PLoS Genet 11(2):e1004653. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaccai M, Lipshitz HD (1996) Role of Adducin-like (hu-li tai shao) mRNA and protein localization in regulating cytoskeletal structure and function during Drosophila Oogenesis and early embryogenesis. Dev Genet 19(3):249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pesacreta TC, Byers TJ, Dubreuil R, Kiehart DP, Branton D (1989) Drosophila spectrin: the membrane skeleton during embryogenesis. J Cell Biol 108(5):1697–1709. 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buszczak M, Paterno S, Lighthouse D, Bachman J, Planck J, Owen S, Skora AD, Nystul TG, Ohlstein B, Allen A, Wilhelm JE, Murphy TD, Levis RW, Matunis E, Srivali N, Hoskins RA, Spradling AC (2007) The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics 175(3):1505–1531. 10.1534/genetics.106.065961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lye CM, Naylor HW, Sanson B (2014) Subcellular localizations of the CPTI collection of YFP-tagged proteins in Drosophila embryos. Development 141(20):4006–4017. 10.1242/dev.111310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morin X, Daneman R, Zavortink M, Chia W (2001) A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(26):15050–15055. 10.1073/pnas.261408198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagarkar-Jaiswal S, Lee PT, Campbell ME, Chen K, Anguiano-Zarate S, Gutierrez MC, Busby T, Lin WW, He Y, Schulze KL, Booth BW, Evans-Holm M, Venken KJ, Levis RW, Spradling AC, Hoskins RA, Bellen HJ (2015) A library of MiMICs allows tagging of genes and reversible, spatial and temporal knockdown of proteins in Drosophila. elife 4. 10.7554/eLife.05338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rørth P (1998) Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech Dev 78(1-2):113–118. 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00157-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]