ABSTRACT

A substantial burden of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infections and HPV-related cancers can be mitigated by vaccination. The current study aimed to investigate the willingness of female students at the University of Kuwait to get HPV vaccination and its possible association with general vaccine conspiracy beliefs (VCBs). This cross-sectional survey study was conducted during September–November 2022 using a validated VCB scale as the survey instrument. The final sample comprised 611 respondents with a median age of 22 y and a majority of Arab ethnicity (n = 600, 98.2%). Only 360 respondents (56.9%) heard of HPV before participation and these students showed an above-average level of HPV knowledge (mean knowledge score of 12.7 ± 2.6 out of 16 as the maximum score), of whom only 33 self-reported HPV vaccine uptake (9.2%). The willingness to accept free-of-charge HPV vaccination was seen among 69.8% of the participants, with 20.1% who were hesitant and 10.1% who were resistant. The acceptance of HPV vaccination if payment is required was 23.1%. Reasons for HPV vaccine hesitancy/resistance included complacency to the HPV disease risks, lack of confidence in HPV vaccination, and inconvenience. The embrace of VCBs was associated with significantly higher odds of HPV vaccine hesitancy/resistance. The current study showed the detrimental impact of endorsing vaccine conspiracy beliefs manifested in lower intention to get HPV vaccination among female university students in Kuwait. This should be considered in vaccine promotion efforts aiming to reduce the burden of HPV cancers.

KEYWORDS: Vaccine attitude, vaccine acceptance, sexually transmitted infection, awareness

Introduction

The morbidity and mortality from human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers remain substantial worldwide.1 In particular, infection by high-risk HPV types (e.g., HPV-16, HPV-18, among others) is associated with cervical, oropharyngeal, and anogenital cancers.2–4 Additionally, HPV is considered the most common causative agent of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1 A major problem of HPV infection is the large fraction of asymptomatic cases that remain unrecognized sustaining the forward transmission of the virus.5,6

The tropism of HPV is in the squamous epithelium of mucous membranes, including the cervix.7 The main documented route of HPV transmission is sexual practices, although non-sexual routes of transmission have also been reported.8,9 The molecular basis of HPV carcinogenesis is well described, with the integration of viral DNA into the host genome, leading to genomic instability, subsequently favoring transforming genetic events and progression to malignancy.10 Strategies to prevent HPV-related cancers include vaccination against high-risk types and screening programs for early detection and treatment of precancerous lesions.11

Vaccination for girls represents an evidence-based, cost-effective intervention measure to reduce the burden of HPV-related cervical cancer (CC) as advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO).12 If the WHO 90–70–90 targets (90% fully vaccinated girls by age 15 y, 70% of females undergoing CC screening by high-performance test at 35 and 45 y of age, and treatment for 90% of women identified with cervical disease) are achieved by the year 2030, this strategy would prevent more than 62 million CC-related deaths by the year 2120.12,13

So far, three vaccine types have been approved to prevent infection by HPV types commonly implicated in CC.14 Currently, HPV vaccination is recommended for girls at 11 y through to 26 y given as a two-dose vaccine, with lower benefits among older females as a result of the higher chance of HPV exposure that comes with advancing in age.15,16 The current evidence points to high safety and efficacy profiles of the currently approved HPV vaccines, despite the need for further comprehensive long-term studies.17–19

In Kuwait, among other Middle Eastern countries, the burden of HPV-related disease is relatively low.20,21 This can explain the low perceived risk of HPV-related disease in the region.22 Complacency toward the disease partly explains the low intentions to get vaccinated, which was previously shown in the context of HPV vaccination.22–24 However, there is sufficient evidence indicating that the burden of HPV-related cancers represents a public health issue warranting intervention.25

The challenges to the efforts aiming to reduce the burden of HPV-related disease in the Middle East include a lack of awareness, low HPV vaccine uptake, and unwillingness to get vaccinated.22,24,26–29 These issues were manifested in earlier studies in the Middle East, where the discussion of STIs can be viewed as a taboo subject.30,31 An additional issue impeding HPV vaccination in Middle Eastern countries is the affordability of the vaccine in terms of cost. Even in Kuwait, a high-income country, the vaccine is not part of the routine immunization program and the two-dose HPV vaccine costs about 150 Kuwaiti dinars (KWD, about 490 US dollars).25,32 Thus, unwillingness to pay for the vaccine can be a major constraint driving HPV vaccination hesitancy/resistance.22,33 Furthermore, an issue that came to light following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, is the embrace of conspiratorial ideas regarding vaccination which was widely prevalent in the Middle East, even among educated study groups (e.g., health professionals).34–36 Misinformation as the main driving factor behind the negative attitude to vaccination was recently shown in the context of HPV vaccination.37

Therefore, the current study aimed to evaluate the willingness of female university students in Kuwait to get HPV vaccination. Additionally, the study objectives included the evaluation of the factors associated with hesitancy/resistance to get HPV vaccination. Moreover, the study intended to evaluate the overall embrace of vaccine conspiracy beliefs among female students at various colleges studying at Kuwait University.

Methods

Study design

The current online survey study was based on a cross-sectional design to survey female students enrolled at Kuwait University (KU), which is the oldest and the largest public university in the country with more than 38,000 students enrolled in 16 different colleges.38 The survey instrument was based on the previously published validated tools including the vaccine conspiracy belief scale (VCBS) validated by Shapiro et al.22,26,27,39 The survey tool was uploaded into Google Forms in both Arabic and English languages simultaneously. Then, survey distribution was based on the snowball convenience-based approach starting from the first author and her contacts asking for further distribution of the survey link via the following social media and instant messaging services: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Messenger, and WhatsApp. Participation was voluntary, and anonymous and no incentives were offered to the potential participants.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was briefly divided into six sections as follows: First, an introductory section with a mandatory e-consent item. Second, the sociodemographic information section inquired about age, nationality, ethnicity, current educational level, college, and monthly income of the household. Third, a section on HPV knowledge started with an introductory question “Have you heard of HPV prior to this survey?,” with “yes” or “no” as possible responses. For those who answered “no,” the survey was directed to the VCBS section. For the students who answered “yes,” eight HPV knowledge questions adopted from a previous study followed, with yes, no, and I do not know as the possible responses.22 The eight items formed the HPV knowledge score (HPV K-score) based on the following scoring: for correct responses a score of 2 was given, while I do not know and incorrect responses were given the scores of 1 and zero, respectively, yielding a range for HPV K-score of zero–16. Fourth, a section assessing the intention to get HPV vaccination, the previous history of HPV vaccine uptake and sources of information about HPV followed. The exact phrasing of the item assessing the intention to get HPV vaccination was “Are you willing to get HPV vaccine if provided for free?,” with yes vs. maybe vs. no as the possible responses. The students who answered “yes” comprised the HPV vaccine acceptance group, while those who answered “maybe” and “no” comprised the vaccine hesitant and vaccine-resistant groups, respectively. Finally, the vaccine conspiracy beliefs were assessed using seven items on a 7-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, neutral, somewhat agree, agree, and strongly agree).39 Higher VCBS scores indicated a higher embrace of vaccine conspiracies.22,34,39 To rule out careless responses, an attention question was asked by the end of the survey, where the participants were asked to write down a number shown in an attached figure. The complete survey instrument is provided in (Supplementary File 1).

Ethical approval

The current study was approved by the Health Sciences Center Ethical Committee at Kuwait University (reference number: VDR/EC-4016, granted on 27 April 2022). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants, which was mandatory for the completion of the survey.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26.0, IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics included the measurements of mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and interquartile range (IQR). Normality of distribution for scale variables (HPV K-score, VCBS), was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test (K–S). Univariate analyses were conducted based on the chi-squared (χ2), Mann–Whitney U (M–W), and Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) tests. Logistic regression multivariate analyses were done to evaluate the associations between different study variables as follows: Age was dichotomized into two categories based on the median age in the study sample, which was 22 y. The HPV K-score was dichotomized based on the mean value of the participants who have heard of HPV prior to the study into two categories: HPV K-score ≤12 (lower HPV knowledge) vs. HPV K-score >12 (higher HPV knowledge). The VCBS score was dichotomized into two categories based on the mean VCBS in the whole study sample: VCBS <28 indicating a lower embrace of vaccine conspiracies vs. VCBS ≥28 indicating higher embrace of vaccine conspiracies. The level of statistical significance was considered for p < .050.

Results

A total of 652 responses were retrieved during 18 September 2022–9 November 2022. The number of respondents who did not agree to participate in the study was 33 (5.1%), with an additional eight responses that were excluded as careless responses based on incorrect responses to the attention item (1.2%). Thus, the final study sample comprised a total of 611 respondents (93.7%).

Study sample characteristics

The final study sample consisted of 611 respondents. A summary of the study sample characteristics is shown in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics (N = 611).

| Variable | Category | N3 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | <22 y | 277 (45.3) |

| ≥22 y | 334 (54.7) | |

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 490 (80.2) |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 121 (19.8) | |

| Ethnicity | Arab | 600 (98.2) |

| Non-Arab | 11 (1.8) | |

| Current educational level | Undergraduate | 492 (80.5) |

| Postgraduate | 119 (19.5) | |

| College | Health | 228 (37.3) |

| Scientific | 171 (28.0) | |

| Humanities | 212 (34.7) | |

| Monthly income of household | ≤1250 KWD2 | 216 (35.4) |

| >1250 KWD | 395 (64.6) | |

| Have you heard of HPV1 prior to this survey? | Yes | 338 (55.3) |

| No | 273 (44.7) |

1HPV: Human papillomavirus; 2KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; 3N: number.

The respondents belonged to 15 different colleges with the highest number affiliated with the College of Engineering and Petroleum (n = 94, 15.4%), Medicine (n = 87, 14.2%), Education (n = 67, 11.0%), Pharmacy (n = 61, 10.0%), Allied Health Sciences (n = 56, 9.2%), Science (n = 42, 6.9%), Social Sciences (n = 39, 6.4%), Law (n = 33, 5.4%), Arts (n = 32, 5.2%), Business Administration (n = 31, 5.1%), Life Sciences (n = 23, 3.8%), Public Health (n = 14, 2.3%), Architecture (n = 12, 2.0%), Dentistry (n = 10, 1.6%), and Sharia and Islamic Studies (n = 10, 1.6%).

Knowledge of HPV prior to participation

In the whole study sample, only 55.3% of the respondents indicated that they have heard of HPV prior to participation (n = 338). Older age, postgraduate education, affiliation with health colleges, and higher monthly income were significantly associated with a higher percentage of knowledge of HPV prior to participation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between study variables and knowledge of HPV prior to participation.

| Variable | Category | Have you heard of HPV2 prior to this survey? |

p Value4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N3 (%) | No N (%) | |||

| Age | <22 y | 120 (43.3) | 157 (56.7) | < .001 |

| ≥22 y | 218 (65.3) | 116 (34.7) | ||

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 280 (57.1) | 210 (42.9) | .068 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 58 (47.9) | 63 (52.1) | ||

| Ethnicity | Arab | 329 (54.8) | 271 (45.2) | .074 |

| Non-Arab | 9 (81.8) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Current educational level | Undergraduate | 249 (50.6) | 243 (49.4) | < .001 |

| Postgraduate | 89 (74.8) | 30 (25.2) | ||

| College | Health | 170 (74.6) | 58 (25.4) | < .001 |

| Scientific | 76 (44.4) | 95 (55.6) | ||

| Humanities | 92 (43.4) | 120 (56.6) | ||

| Monthly income of household | ≤1250 KWD1 | 102 (47.2) | 114 (52.8) | .003 |

| >1250 KWD | 236 (59.7) | 159 (40.3) | ||

1KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; 2HPV: human papillomavirus; 3N: number; 4p value: Calculated using chi-squared test. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

HPV knowledge among the respondents who have heard of the virus before participation

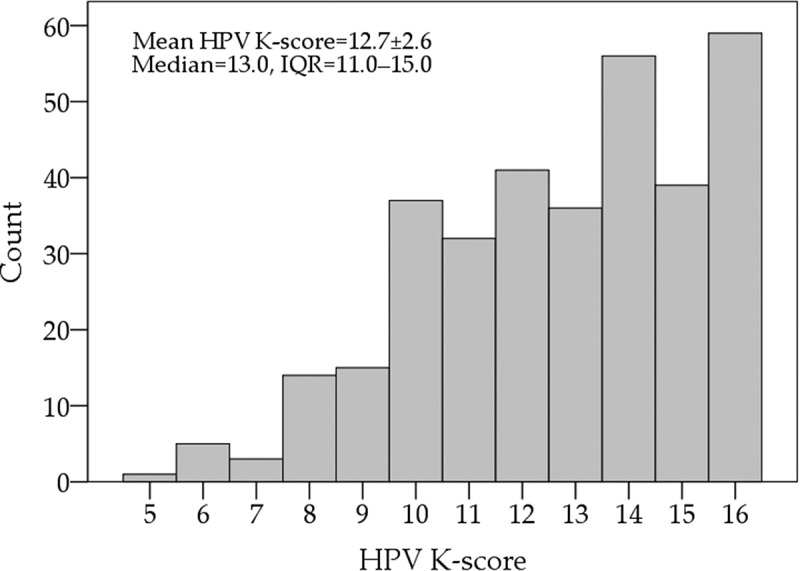

The overall level of HPV knowledge among the participants who have heard of HPV prior to the study was non-normally distributed (p < .001, K–S), with moderate skewness of −0.531 indicating a relatively high level of HPV knowledge (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge among the participants who have heard of HPV prior to the study.

HPV K-score: Human papillomavirus knowledge score calculated based on correct responses to 10 knowledge items; IQR: interquartile range.

Per item, correct responses ranged from 50.9% to 84.0%, with correct knowledge that vaccination is available to prevent HPV infection observed among 78.7% of the participants who heard of HPV prior to participation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge per item among the participants who have heard of HPV prior to the study.

HPV: Human papillomavirus. Incorrect items are marked with an asterisk.

By dividing the HPV-K score into two categories (lower for HPV K-scores ≤12 and higher for HPV K-scores >12), better HPV knowledge was seen among students in health colleges followed by students in scientific colleges and students in humanities colleges (Table 3).

Table 3.

HPV knowledge association with study variables.

| Variable | Category | HPV K-score2 |

p Value4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤12 N3 (%) | >12 N (%) | |||

| Age | <22 y | 59 (49.2) | 61 (50.8) | .139 |

| ≥22 y | 89 (40.8) | 129 (59.2) | ||

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 126 (45.0) | 154 (55.0) | .323 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 22 (37.9) | 36 (62.1) | ||

| Ethnicity | Arab | 145 (44.1) | 184 (55.9) | .522 |

| Non-Arab | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | ||

| Current educational level | Undergraduate | 115 (46.2) | 134 (53.8) | .137 |

| Postgraduate | 33 (37.1) | 56 (62.9) | ||

| College | Health | 52 (30.6) | 118 (69.4) | < .001 |

| Scientific | 40 (52.6) | 36 (47.4) | ||

| Humanities | 56 (60.9) | 36 (39.1) | ||

| Monthly income of household | ≤1250 KWD1 | 45 (44.1) | 57 (55.9) | .936 |

| >1250 KWD | 103 (43.6) | 133 (56.4) | ||

1KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; 2HPV K-score: human papillomavirus knowledge score calculated based on correct responses to eight knowledge items; 3N: number; 4p value: calculated using chi-squared test. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

History of HPV vaccine uptake among the study participants

Among the students who have heard of HPV prior to participation, only 30 indicated the previous uptake of HPV vaccination (8.9%). Higher vaccine uptake was associated with older age (11.5% among those aged 22 y or older vs. 4.2% among the students younger than 22 y, Table 4).

Table 4.

History of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake among participants who have heard of HPV prior to participation.

| Variable | Category | Have you received HPV2 vaccination? |

p Value4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N3 (%) | No N (%) | |||

| Age | <22 y | 5 (4.2) | 115 (95.8) | .024 |

| ≥22 y | 25 (11.5) | 193 (88.5) | ||

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 24 (8.6) | 256 (91.4) | .666 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 6 (10.3) | 52 (89.7) | ||

| Ethnicity | Arab | 29 (8.8) | 300 (91.2) | .811 |

| Non-Arab | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | ||

| Current educational level | Undergraduate | 18 (7.2) | 231 (92.8) | .075 |

| Postgraduate | 12 (13.5) | 77 (86.5) | ||

| College | Health | 15 (8.8) | 155 (91.2) | .482 |

| Scientific | 9 (11.8) | 67 (88.2) | ||

| Humanities | 6 (6.5) | 86 (93.5) | ||

| Monthly income of household | ≤1250 KWD1 | 7 (6.9) | 95 (93.1) | .392 |

| >1250 KWD | 23 (9.7) | 213 (90.3) | ||

1KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; 2HPV: human papillomavirus; 3N: number; 4p value: calculated using chi-squared test. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

The intention to get HPV vaccination if provided freely and if payment is needed

The overall willingness to accept HPV vaccination if provided freely was expressed by 236 participants who have heard of HPV prior to participation (69.8%), with 68 participants who were hesitant (20.1%) and 34 participants who were resistant (10.1%). The acceptance for HPV vaccination was associated with older age, postgraduate educational level, and affiliation with health colleges (Table 5)

Table 5.

The intention to get human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination if provided freely and if payment is required divided by different study variables.

| Variable | Category | Are you willing to get HPV2 vaccine if provided for free? |

p Value4 | Are you willing to pay about 150 KWD to get HPV vaccination, given that the vaccine is safe and effective? |

p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N3 (%) | Maybe N (%) | No N (%) | Yes N (%) | Maybe N (%) | No N (%) | ||||

| Age | <22 y | 75 (62.5) | 34 (28.3) | 11 (9.2) | .020 | 21 (17.5) | 51 (42.5) | 48 (40.0) | .196 |

| ≥22 y | 161 (73.9) | 34 (15.6) | 23 (10.6) | 57 (26.1) | 83 (38.1) | 78 (35.8) | |||

| Nationality | Kuwaiti | 196 (70.0) | 53 (18.9) | 31 (11.1) | .244 | 71 (25.4) | 105 (37.5) | 104 (37.1) | .061 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 40 (69.0) | 15 (25.9) | 3 (5.2) | 7 (12.1) | 29 (50.0) | 22 (37.9) | |||

| Ethnicity | Arab | 228 (69.3) | 67 (20.4) | 34 (10.3) | .410 | 76 (23.1) | 131 (39.8) | 122 (37.1) | .894 |

| Non-Arab | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) | |||

| Current educational level | Undergraduate | 167 (67.1) | 60 (24.1) | 22 (8.8) | .007 | 51 (20.5) | 102 (41.0) | 96 (38.6) | .166 |

| Postgraduate | 69 (77.5) | 8 (9.0) | 12 (13.5) | 27 (30.3) | 32 (36.0) | 30 (33.7) | |||

| College | Health | 134 (78.8) | 26 (15.3) | 10 (5.9) | .003 | 47 (27.6) | 68 (40.0) | 55 (32.4) | .159 |

| Scientific | 47 (61.8) | 21 (27.6) | 8 (10.5) | 17 (22.4) | 29 (38.2) | 30 (39.5) | |||

| Humanities | 55 (59.8) | 21 (22.8) | 16 (17.4) | 14 (15.2) | 37 (40.2) | 41 (44.6) | |||

| Monthly income of household | ≤1250 KWD | 71 (69.6) | 17 (16.7) | 14 (13.7) | .244 | 19 (18.6) | 31 (30.4) | 52 (51.0) | .003 |

| >1250 KWD | 165 (69.9) | 51 (21.6) | 20 (8.5) | 59 (25.0) | 103 (43.6) | 74 (31.4) | |||

1KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; 2HPV: human papillomavirus; 3N: number; 4p value: calculated using chi-squared test. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

The willingness to pay for the vaccine was reported only by 78 participants (23.1%), compared to 134 who were hesitant (39.6%) and 126 participants who were resistant to pay for the vaccine (37.3%). Willingness to pay for HPV vaccination was associated with a higher monthly income of the household (Table 5).

The reasons for HPV vaccine hesitancy/resistance were mostly linked to the complacency and lack of confidence items followed by the constraints’ items (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The self-reported reasons for hesitancy or resistance to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among the participants who have heard of HPV prior to the study.

HPV: Human papillomavirus. Multiple responses were allowed.

The embrace of vaccine conspiracy beliefs among the participating students

The mean value for VCBS in the whole study sample was 28.2 ± 11.7 (median: 28.0, IQR: 18.0–38.0). Higher VCBS was seen among students younger than 22 y (mean VCBS: 29.3 ± 11.1 vs. 27.3 ± 12.0, p = .027, M–W), undergraduate students (mean VCBS: 28.7 ± 11.4 vs. 26.2 ± 12.5, p = .032, M–W), students affiliated to humanities’ colleges compared to those affiliated to scientific and health schools, respectively (mean VCBS: 33.4 ± 10.6 vs. 29.5 ± 10.5 vs. 22.4 ± 10.8, p < .001, K–W), lower monthly income (mean VCBS: 30.2 ± 11.4 vs. 27.1 ± 11.7,p = .001, M–W), and among participants who did not hear of HPV prior to participation (mean VCBS: 31.5 ± 10.1 vs. 25.5 ± 12.2, p < .001, M–W), while nationality, and ethnicity did not show statistically significant differences.

Higher VCBS was also noticed among the participants who were resistant to HPV vaccination (unwilling to get free HPV vaccination and unwilling to pay for HPV vaccination) compared to hesitancy and acceptance groups (p < .001 for the two comparisons, K–W, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The association between acceptance of HPV vaccination and vaccine conspiracy beliefs.

HPV: Human papillomavirus; VCBS: vaccine conspiracy beliefs score with higher values indicating higher embrace of vaccine conspiracies; CI: confidence interval of the mean; KWD: Kuwaiti dinar; K–W: Kruskal–Wallis test.

Multivariate analysis for the factors associated with higher HPV vaccine acceptance

Multivariate analysis using multinomial logistic regression with age, educational level and college as the covariates revealed that the embrace of conspiracy beliefs was significantly correlated with HPV vaccine resistance and hesitancy (Table 6), while higher level of HPV knowledge and postgraduate education were associated with vaccine acceptance compared to the hesitancy group (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis for the possible factors associated with HPV vaccine acceptance compared to vaccine hesitancy and resistance.

| HPV1 vaccine acceptance vs. HPV vaccine hesitancy | OR4 (95% CI)5 | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age: ≥22 y vs. <22 y | 1.843 (0.995–3.415) | .052 |

| Current education: postgraduate vs. undergraduate | 2.586 (1.083–6.174) | .032 |

| College: health vs. humanities | 0.786 (0.375–1.648) | .524 |

| College: scientific vs. humanities | 1.527 (0.705–3.308) | .283 |

| HPV K-score2: >12 vs. ≤12 | 1.926 (1.063–3.491) | .031 |

| VCBS3: <28 vs. ≥28 |

2.275 (1.471–5.025) |

.001 |

| HPV vaccine acceptance vs. HPV vaccine resistance |

OR (95% CI) |

p Value |

| Age: ≥22 y vs. <22 y | 1.419 (0.569–3.541) | .453 |

| Current education: postgraduate vs. undergraduate | 0.591 (0.234–1.493) | .266 |

| College: health vs. humanities | 0.686 (0.263–1.792) | .442 |

| College: scientific vs. humanities | 0.629 (0.229–1.731) | .370 |

| HPV K-score: >12 vs. ≤12 | 1.858 (0.822–4.198) | .136 |

| VCBS: <28 vs. ≥28 | 13.889 (4.529–43.478) | < .001 |

1HPV: Human papillomavirus; 2HPV K-score: human papillomavirus knowledge score calculated based on correct responses to eight knowledge items; 3VCBS: vaccine conspiracy beliefs score with higher values indicating higher embrace of vaccine conspiracies; 4OR: odds ratio; 5CI: confidence interval.

Sources of HPV information

The most common source of HPV information as reported by the participants who have heard of HPV prior to participation was university courses (n = 149, 44.1%), followed by social media platforms (n = 137, 40.5%), and internet websites (n = 131, 38.8%). The source of HPV information was linked with HPV vaccine acceptance, with the highest acceptance level seen among those who depended on university courses (78.5%), followed by those who depended on healthcare providers’ information (77.7%), while the lowest percentage of HPV vaccine acceptance was seen among those who depended on television/radio/newspapers (54.5%), internet websites (58.0%), and social media platforms (67.2%, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The sources of information regarding HPV as reported by the participants who have heard of HPV prior to participation.

HPV: Human papillomavirus; multiple answers were allowed; the sources of HPV information are plotted on the reverse Y-axis as percentages.

The reliance on university courses as a source of HPV information was associated with higher intention to get HPV vaccination (117/149 (78.5%) vs. 119/189 (63.0%), p = .002, χ2 test). On the contrary, the following were associated with lower intention to get HPV vaccination: the dependence on internet websites (76/131 (58.0%) vs. 160/207 (77.3%), p < .001, χ2 test), and the dependence on television/radio/newspapers (18/33 (54.5%) vs. 218/305 (71.5%), p = .044, χ2 test).

Discussion

The main findings of the current study indicated the detrimental effect of endorsing vaccine conspiracy beliefs which were manifested in HPV vaccine hesitancy/resistance among female university students in Kuwait. Additionally, the results of the current study revealed a very low percentage of HPV vaccine uptake among university students in the Middle Eastern country, as self-reported by the participants.

The current study demonstrated a history of HPV vaccine uptake at a level of 9% among female university students studying at the largest public university in the country, and who knew about the virus before participation.38 The very low level of HPV vaccine coverage resonates with the results of previous studies that were conducted in the Middle East.22,40–42 For example, a recent study that was conducted in Kuwait among female school teachers demonstrated that only 26 participants were vaccinated against HPV representing 16% of the participants who were aware of HPV vaccine availability.29 The self-reported history of HPV vaccine uptake was also very low at a level of 4% in a recent study among female university students studying at health schools in Jordan.22 A recent study among medical students in Lebanon showed a vaccination rate of 16%, with an alarmingly low level of HPV knowledge.43 Possible explanation for the very low coverage of HPV vaccination in this study among other studies from the Middle East is the conservative culture and low level of recommendation by health professionals besides the unawareness regarding vaccine availability.42,44–46

Another important finding was the low level of awareness regarding HPV. Specifically, 45% of the participants have not heard of HPV before participation. Additionally, variable gaps in HPV knowledge were found among the participants who have heard of HPV before participation including aspects related to disease treatment, HPV infection occurrence among males, the possibility of asymptomatic HPV infections, and awareness regarding vaccine availability. Consistent with our findings, several recent studies suggested unawareness regarding several aspects of HPV-related disease in the Middle East region.22,26–28,47

Considering the sexual transmission of high-risk HPV types that are associated with cervical among other genital and oropharyngeal cancers, coupled with cultural and religious barriers prevailing in the Middle East, the preventive efforts aiming to reduce the burden of HPV-related cancers can be challenging in the region.48,49 The socio-cultural and religious issues should be meticulously considered for the successful implementation of HPV vaccination in the region similar to other world regions.49,50

Another important finding of the current study is the relatively considerable percentage of participants who were either hesitant (20%) or resistant (10%) to HPV vaccination if provided free-of-charge. The intention to get HPV vaccination dropped from about 70% for free vaccination to only 23% if payment for the vaccine was required. This can be a major barrier to the successful implementation of HPV vaccination in Kuwait considering the cost of the vaccine. Similarly, a recent study among female university students in Jordan highlighted the issue of vaccine affordability in the decision to get vaccinated.22 Understandably, a higher willingness to pay for the vaccine was observed among participants with a higher monthly income. A recent systematic review from the Middle East showed that HPV vaccine acceptance would be high if the cost issues could be rectified.51

The role of sociodemographic variables should be considered in the strategic planning of vaccine implementation, which was shown in univariate analysis in this study where older age and postgraduate education were associated with higher intention to get vaccinated against HPV. The role of sociodemographic factors as determinants of willingness to get vaccinated has been demonstrated previously regarding HPV vaccination among other vaccines.22,34,52,53

The intention to get HPV vaccination was reported at variable rates in different countries and depending on the population of interest. For example, a recent study among young Greek adults showed a rate of willingness to get HPV vaccination of 66%, with vaccine coverage of 52%.54 On the other hand, a recent study that was conducted in 2022 among female university students in China showed much higher rate of intention to get HPV vaccination (90%).52 Another recent study among male medical students in Saudi Arabia showed an acceptance rate of 49% for HPV vaccination.47 The acceptance of HPV vaccination was much higher among adult women in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at 80%.55

The issues cited by the participants who were hesitant/resistant to HPV vaccination in this study included the relatively high level of complacency toward HPV-related disease. In the Arab countries of the Middle East, a notion is present among the general public that views STIs as an uncommon issue. This view lacks credible evidence due to the primitive nature of research addressing STIs in the region.56 Recent studies have shown the relevance of conducting STI research in the region, and in the context of HPV for example, recent studies from Kuwait demonstrated the circulation of high-risk HPV types not covered in the bivalent HPV vaccine highlighting the role of epidemiologic domestic studies to guide a successful immunization campaign.57,58

Besides complacency toward the disease, the lack of confidence particularly in relation to HPV vaccine safety was reported by the hesitant/resistant participants in this study. This was also demonstrated in the previous Jordanian study, and it emphasizes the value of demonstrating the safety of the vaccine and its health benefits in the prevention of CC development.22,59 The issue of perceived susceptibility in relation to HPV vaccine uptake rates has been highlighted in a systematic review involving studies from the United States, Australia, and China.60 Stressing on vaccine safety and recommendation by health providers were shown to enhance HPV vaccine acceptability in the UAE study.55

A major finding of the current study was the significant correlation between the embrace of vaccine conspiracies and HPV vaccine hesitancy/resistance. Supporting this finding and highlighting the negative impact of conspiracies on health behavior, recent studies in the context of different vaccines have shown the prominence of this issue. For example, a previous study conducted among the general Arab public (mainly in Jordan and Kuwait) has shown a very high level of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine hesitancy correlated with vaccine hesitancy.34 Similarly, a recent study among health professionals in Kuwait showed a similar finding.35 Of note, vaccine conspiracies were significantly associated with lower uptake of influenza vaccine among healthcare workers in Jordan.61 In the context of HPV vaccination, and consistent with our findings, a recent study among female university students in Jordan showed that the endorsement of vaccine conspiracy beliefs was associated with higher odds of HPV vaccine rejection.22

Since the source of information regarding HPV was linked with the intentions to get vaccinated against HPV, health education particularly through university courses appears of high importance.22 This was reflected in our results where lower HPV knowledge was associated with HPV vaccination hesitancy. This issue is of particular relevance for the students in the humanities colleges where the students are less likely to be exposed to health education and this was manifested in lower HPV knowledge among this group in the current study. Additionally, the reliance on internet websites was linked with lower intentions to get HPV vaccination highlighting the role of sources of information on the decision to get vaccinated.

The current study suffered from inevitable limitations including the cross-sectional design which should be considered in the interpretation of the results since vaccine hesitancy/rejection is a time- and context-specific phenomenon.62 Additionally, the history of HPV vaccine uptake was self-reported with the absence of evidence of getting the vaccine among the participants. Furthermore, the current study albeit involving students in the largest public university in Kuwait, might not be totally representative of female university students in the country. Finally, convenience sampling provides the advantage of expedited results; however, this sampling method is prone to suffer from the issue of selection bias.

To conclude, our findings demonstrated the potential harmful impact of vaccine conspiracies that were linked with HPV vaccine hesitancy/rejection among female university students in Kuwait. Issue to be considered in the vaccine promotion efforts include (1) improving the level of HPV awareness and knowledge which can reduce the complacency to the disease risks: (2) the provision of introducing HPV vaccination free-of-charge as demonstrated by the disparity between vaccine acceptance rates for free vaccination compared to willingness to pay for the vaccine; (3) efforts should be made to lower the constraints of vaccination to make it aconvenient experience; (4) the focus on vaccine safety and efficacy besides the potential benefits of the vaccine should be highlighted to emphasize the vaccine role in cancer prevention; and (5) importantly, addressing the issues of vaccine conspiracies which appear widely prevalent in the Middle East, and stressing on accurate delivery of information regarding vaccination through reliable sources.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Mariam Alsanafi and Malik Sallam

Methodology: Mariam Alsanafi, Nesreen A. Salim, and Malik Sallam

Software: Malik Sallam

Validation: Mariam Alsanafi, Nesreen A. Salim, and Malik Sallam

Formal analysis: Malik Sallam

Investigation: Mariam Alsanafi, Nesreen A. Salim, and Malik Sallam

Resources: Malik Sallam

Data Curation: Mariam Alsanafi, Nesreen A. Salim, and Malik Sallam

Writing – Original Draft: Malik Sallam

Writing – Review & Editing: Mariam Alsanafi, Nesreen A. Salim, and Malik Sallam

Visualization: Malik Sallam

Supervision: Malik Sallam

Project administration: Mariam Alsanafi and Malik Sallam

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Malik Sallam).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2194772

References

- 1.Kombe Kombe AJ, Li B, Zahid A, Mengist HM, Bounda GA, Zhou Y, Jin T.. Epidemiology and burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases, molecular pathogenesis, and vaccine evaluation. Front Public Health. 2020;8:552028. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.552028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F.. Global cancer statistics 2020: gLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–10. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao M, Wu Q, Hao Y, Hu J, Gao Y, Zhou S, Han L. Global, regional, and national burden of cervical cancer for 195 countries and territories, 2007–2017: findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:419. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boda D, Docea AO, Calina D, Ilie MA, Caruntu C, Zurac S, Neagu M, Constantin C, Branisteanu D, Voiculescu V, et al. Human papilloma virus: apprehending the link with carcinogenesis and unveiling new research avenues (Review). Int J Oncol. 2018;52:637–55. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of Viral Latency. Viruses. 2017;9:267. doi: 10.3390/v9100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen ND. HPV disease transmission protection and control. Microb Cell. 2016;3:476–90. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.09.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egawa N, Egawa K, Griffin H, Doorbar J. Human papillomaviruses; epithelial tropisms, and the development of Neoplasia. Viruses. 2015;7:3863–90. doi: 10.3390/v7072802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petca A, Borislavschi A, Zvanca ME, Petca RC, Sandru F, Dumitrascu MC. Non-sexual HPV transmission and role of vaccination for a better future (review). Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:186. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panatto D, Amicizia D, Trucchi C, Casabona F, Lai PL, Bonanni P, Boccalini S, Bechini A, Tiscione E, Zotti CM, et al. Sexual behaviour and risk factors for the acquisition of human papillomavirus infections in young people in Italy: suggestions for future vaccination policies. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:623. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehoux M, D’abramo CM, Archambault J. Molecular mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis. Public Health Genomics. 2009;12:268–80. doi: 10.1159/000214918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CK, Aimagambetova G, Ukybassova T, Kongrtay K, Azizan A. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer: epidemiology, screening, and vaccination-review of current perspectives. J Oncol. 2019;2019:3257939. doi: 10.1155/2019/3257939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. [accessed 2023 Feb 9]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107.

- 13.Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, Keane A, Simms KT, Caruana M, Burger EA, Martin D, Nguyen DTN, Bénard É, et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020;395:591–603. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R, Pan W, Jin L, Huang W, Li Y, Wu D, Gao C, Ma D, Liao S. Human papillomavirus vaccine against cervical cancer: opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 2020;471:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698–702. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination - updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soliman M, Oredein O, Dass CR. Update on safety and efficacy of HPV vaccines: focus on gardasil. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2021;10:101–13. doi: 10.22088/ijmcm.Bums.10.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbyn M, Xu L. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic HPV vaccines. A Cochrane review of randomized trials. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:1085–91. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1548282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porras C, Tsang SH, Herrero R, Guillén D, Darragh TM, Stoler MH, Hildesheim A, Wagner S, Boland J, Lowy DR, et al. Efficacy of the bivalent HPV vaccine against HPV 16/18-associated precancer: long-term follow-up results from the Costa Rica vaccine trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1643–52. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30524-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Awadhi R, Chehadeh W, Kapila K. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among women with normal cervical cytology in Kuwait. J Med Virol. 2011;83:453–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Awadhi R, Chehadeh W, Jaragh M, Al-Shaheen A, Sharma P, Kapila K. Distribution of human papillomavirus among women with abnormal cervical cytology in Kuwait. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:107–14. doi: 10.1002/dc.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallam M, Al-Mahzoum K, Eid H, Assaf AM, Abdaljaleel M, Al-Abbadi M, Mahafzah A. Attitude towards HPV vaccination and the intention to get vaccinated among female university students in health schools in Jordan. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1432. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bencherit D, Kidar R, Otmani S, Sallam M, Samara K, Barqawi HJ, Lounis M. Knowledge and awareness of Algerian students about cervical cancer, HPV and HPV vaccines: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:1420. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandes Q, Allouch S, Gupta I, Elmakaty I, Elzawawi KE, Amarah A, Al-Thawadi H, Al-Farsi H, Vranic S, Al Moustafa A-E. Human papillomaviruses-related cancers: an update on the presence and prevention strategies in the Middle East and North African regions. Pathogens. 2022;11:1380. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11111380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallam M, Al-Fraihat E, Dababseh D, Yaseen A, Taim D, Zabadi S, Hamdan AA, Hassona Y, Mahafzah A, Şahin GÖ. Dental students’ awareness and attitudes toward HPV-related oral cancer: a cross sectional study at the university of Jordan. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:171. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0864-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sallam M, Dababseh D, Yaseen A, Al-Haidar A, Ettarras H, Jaafreh D, Hasan H, Al‐salahat K, Al‐fraihat E, Hassona Y, et al. Lack of knowledge regarding HPV and its relation to oropharyngeal cancer among medical students. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022;5:e1517. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsous MM, Ali AA, Al-Azzam SI, Abdel Jalil MH, Al-Obaidi HJ, Al-Abbadi EI, Hussain ZK, Jirjees FJ. Knowledge and awareness about human papillomavirus infection and its vaccination among women in Arab communities. Sci Rep. 2021;11:786. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80834-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rezqalla J, Alshatti M, Ibraheem A, Omar D, Houda AF, AlHaqqan S, AlGhurair S, Akhtar S. Human papillomavirus (HPV): unawareness of the causal role of HPV infection in cervical cancer, HPV vaccine availability, and HPV vaccine uptake among female school teachers in a Middle Eastern country. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14:661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albanghali MA, Othman BA. A cross-sectional study on the knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases among young adults living in Al Bahah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1872. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horanieh N, Macdowall W, Wellings K. How should school-based sex education be provided for adolescents in Saudi Arabia? Views of stakeholders. Sex Educ. 2021;21:645–59. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1843424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado J, Gómez D, Muñoz, J, Bosch, F, de Sanjosé, S. Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Kuwait. Summary Report. [accessed 2023 Feb 9]. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/KWT.pdf.

- 33.Milondzo T, Meyer JC, Dochez C, Burnett RJ. Human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy highly evident among caregivers of girls attending South African private schools. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:503. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, Yaseen A, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:42. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Sanafi M, Sallam M. Psychological determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study using the 5C and vaccine conspiracy beliefs scales. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:701. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alsanafi M, Al-Mahzoum K, Sallam M. Monkeypox knowledge and confidence in diagnosis and management with evaluation of emerging virus infection conspiracies among health professionals in Kuwait. Pathogens. 2022;11:994. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11090994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milondzo T, Meyer JC, Dochez C, Burnett RJ. Misinformation drives low human papillomavirus vaccination coverage in South African girls attending private schools. Front Public Health. 2021;9:598625. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.598625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuwait University . About Kuwait University. [accessed 2023 Feb 9]. http://kuweb.ku.edu.kw/ku/ar/AboutUniversity/AboutKU/AboutUSKU/index.htm.

- 39.Shapiro GK, Holding A, Perez S, Amsel R, Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dany M, Chidiac A, Nassar AH. Human papillomavirus vaccination: assessing knowledge, attitudes, and intentions of college female students in Lebanon, a developing country. Vaccine. 2015;33:1001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abou El-Ola MJ, Rajab MA, Abdallah DI, Fawaz IA, Awad LS, Tamim HM, Ibrahim A, Mugharbil A, Moghnieh R. Low rate of human papillomavirus vaccination among schoolgirls in Lebanon: barriers to vaccination with a focus on mothers’ knowledge about available vaccines. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:617–26. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.S152737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al Shdefat S, Al Awar S, Osman N, Khair H, Sallam G, Maki S. Identification level of awareness and knowledge of Emirati men about HPV. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:5340064. doi: 10.1155/2022/5340064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haddad SF, Kerbage A, Eid R, Kourie HR. Awareness about the human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccine among medical students in Lebanon. J Med Virol. 2022;94:2796–801. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abi Jaoude J, Khair D, Dagher H, Saad H, Cherfan P, Kaafarani MA, Jamaluddine Z, Ghattas H. Factors associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine recommendation by physicians in Lebanon, a cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2018;36:7562–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abi Jaoude J, Saad H, Farha L, Dagher H, Khair D, Kaafarani MA, Jamaluddine Z, Cherfan P. Barriers, attitudes and clinical approach of Lebanese physicians towards HPV vaccination; a cross- sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20:3181–7. doi: 10.31557/apjcp.2019.20.10.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamdi S. The impact of teachings on sexuality in Islam on HPV vaccine acceptability in the Middle East and North Africa region. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;7(Suppl S1):S17–s22. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farsi NJ, Baharoon AH, Jiffri AE, Marzouki HZ, Merdad MA, Merdad LA. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among male medical students in Saudi Arabia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:1968–74. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1856597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obeid DA, Almatrrouk SA, Alfageeh MB, Al-Ahdal MNA, Alhamlan FS. Human papillomavirus epidemiology in populations with normal or abnormal cervical cytology or cervical cancer in the Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dochez C, Al Awaidy S, Mohsni E, Fahmy K, Bouskraoui M. Strengthening national teams of experts to support HPV vaccine introduction in Eastern Mediterranean countries: lessons learnt and recommendations from an international workshop. Vaccine. 2020;38:1114–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdullahi LH, Hussey GD, Wiysonge CS, Kagina BM. Lessons learnt during the national introduction of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programmes in 6 African countries: stakeholders’ perspectives. S Afr Med J. 2020;110:525–31. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i6.14332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gamaoun R. Knowledge, awareness and acceptability of anti-HPV vaccine in the Arab states of the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic review. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24:538–48. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang Y, Chen C, Wang L, Wu H, Chen T, Zhang L. HPV vaccine hesitancy and influencing factors among university students in China: a cross-sectional survey based on the 3cs model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14025. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Boetzelaer E, Daae A, Winje BA, Vestrheim DF, Steens A, Stefanoff P. Sociodemographic determinants of catch-up HPV vaccination completion between 2016-2019 in Norway. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18:1976035. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1976035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sidiropoulou M, Gerogianni G, Kourti FE, Pappa D, Zartaloudi A, Koutelekos I, Dousis E, Margari N, Mangoulia P, Ferentinou E, et al. Perceptions, knowledge and attitudes among young adults about prevention of HPV infection and immunization. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:1721. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ortashi O, Raheel H, Shalal M. Acceptability of human papilloma virus vaccination among women in the United Arab Emirates. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2007–11. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.5.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abu-Raddad LJ, Ghanem KG, Feizzadeh A, Setayesh H, Calleja JM, Riedner G. HIV and other sexually transmitted infection research in the Middle East and North Africa: promising progress? Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(Suppl S3):iii1–4. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mallik MK, Alramadhan B, Dashti H, Al-Shaheen A, Al Juwaiser A, Das DK, George SS, Kapila K. Human papillomaviruses other than 16, 18 and 45 are the major high risk HPV genotypes amongst women with abnormal cervical smear cytology residing in Kuwait: implications for future vaccination strategies. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:1036–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.24035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapila K, Balakrishnan M, Ali RH, Al-Juwaiser A, George SS, Mallik MK. Interpreting a diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance in cervical cytology and its association with human papillomavirus: a retrospective analysis of 180 cases in Kuwait. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020;20:e318–23. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2020.20.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Health Organization . Human papillomavirus vaccines: wHO position paper, October 2014-recommendations. Vaccine. 2015;33:4383–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnard M, Cole AC, Ward L, Gravlee E, Cole ML, Compretta C. Interventions to increase uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine in unvaccinated college students: a systematic literature review. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100884. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sallam M, Ghazy RM, Al-Salahat K, Al-Mahzoum K, AlHadidi NM, Eid H, Kareem N, Al-Ajlouni E, Batarseh R, Ababneh NA, et al. The role of psychological factors and vaccine conspiracy beliefs in influenza vaccine hesitancy and uptake among Jordanian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:1355. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peretti-Watel P, Larson HJ, Ward JK, Schulz WS, Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy: clarifying a theoretical framework for an ambiguous notion. PLoS Curr. 2015;7. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6844c80ff9f5b273f34c91f71b7fc289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Malik Sallam).