Significance

Sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythm are well-established processes for sleep regulation. The serine/threonine kinase SIK3 is reported as a key molecule for sleep homeostasis. Here, we found that SIK3 in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the brain’s master pacemaker region, is involved in the determination of circadian period length and the arousal timing at the dark onset, without affecting sleep amount and pressure. Our studies suggest that the SIK3–HDAC4 pathway plays a critical role in sleep regulation through both circadian rhythm and sleep homeostasis.

Keywords: SIK3, HDAC4, circadian rhythms, circadian period, arousal timing

Abstract

Mammals exhibit circadian cycles of sleep and wakefulness under the control of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), such as the strong arousal phase-locked to the beginning of the dark phase in laboratory mice. Here, we demonstrate that salt-inducible kinase 3 (SIK3) deficiency in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic neurons or neuromedin S (NMS)–producing neurons delayed the arousal peak phase and lengthened the behavioral circadian cycle under both 12-h light:12-h dark condition (LD) and constant dark condition (DD) without changing daily sleep amounts. In contrast, the induction of a gain-of-function mutant allele of Sik3 in GABAergic neurons exhibited advanced activity onset and a shorter circadian period. Loss of SIK3 in arginine vasopressin (AVP)–producing neurons lengthened the circadian cycle, but the arousal peak phase was similar to that in control mice. Heterozygous deficiency of histone deacetylase (HDAC) 4, a SIK3 substrate, shortened the circadian cycle, whereas mice with HDAC4 S245A, which is resistant to phosphorylation by SIK3, delayed the arousal peak phase. Phase-delayed core clock gene expressions were detected in the liver of mice lacking SIK3 in GABAergic neurons. These results suggest that the SIK3–HDAC4 pathway regulates the circadian period length and the timing of arousal through NMS-positive neurons in the SCN.

Animals show daily changes in physiology and behavior to adapt to the 24-h environmental light–dark cycle with an activity peak at specific circadian timing. C57BL/6 mice exhibit nocturnal behavior with strong arousal for several hours immediately after the onset of the dark phase, which is sustained under constant darkness by the endogenous circadian clock. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus serves as the master circadian pacemaker that synchronizes the peripheral clocks of the whole body (1–4). The SCN consists of two subdivisions, the core (or a ventrolateral region) and the shell (or a dorsolateral region), which are composed of distinct groups of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic neurons characterized by the expression of neuropeptides. Neuromedin S (NMS)–producing neurons account for 40% of SCN neurons and are distributed in both the core and shell regions. NMS-positive neurons have a dominant role in determining the circadian length of the SCN and behavior (5, 6). Arginine vasopressin (AVP)–producing neurons exist in the shell region and regulate behavioral rhythms and susceptibility to a jet lag (7–11). Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)–producing neurons are localized in the core region, and VIP-producing neurons are required for the synchronization of SCN neuron activity and behavioral rhythm regulation (1–4). In addition to generating internal timing, the SCN is important for sleep and wakefulness to occur at specific times of the day, such as the rapid and robust increase in arousal at the onset of the dark period in mice (12). VIP-producing neurons are involved in nighttime sleep, “siesta” (13). The transcriptional–translational feedback loop that consists of transcriptional activators, CLOCK and BMAL1, and two repressors, PERIOD and CRYPTOCHOROME, serves as the molecular basis of 24-h molecular oscillation (14). We have reported salt-inducible kinase (SIK) 3 as a positive regulator of sleep pressure (15–17). Loss of a conserved protein kinase A phosphorylation site in SIK3 leads to an increase in nonrapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) amount and electroencephalogram (EEG) delta power during NREMS. In addition to sleep pressure regulation, SIK3 may be involved in circadian behavior since SIK3-deficient mice showed a longer circadian period (18). However, more than 90% of salt-inducible kinase 3 (SIK3)-deficient mice died on the first day after birth, and the surviving few showed growth retardation and developed multiple metabolic and skeletal abnormalities (19, 20). Thus, to precisely investigate the role of SIK3 in circadian behavior, it is necessary to manipulate of SIK3 specific to SCN neuron groups.

In this study, we used Sik3flox mice, which exhibit SIK3 deficiency depending on a Cre recombinase and examined sleep and circadian behaviors in mice deficient in SIK3 in GABAergic neurons, NMS-positive neurons, and AVP-positive neurons. VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a longer period length and delayed activity onset at the beginning of the dark phase. In contrast, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice had a longer period length with normal arousal at the dark phase onset. We also found that histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), one of the well-established phosphorylation targets of SIK3, regulates the circadian period and peak phase of arousal. These results indicate that the SIK3–HDAC4 pathway in the NMS-positive neurons regulates circadian period length and arousal timing, but the contribution may differ among subpopulations of the NMS-positive neurons.

Results

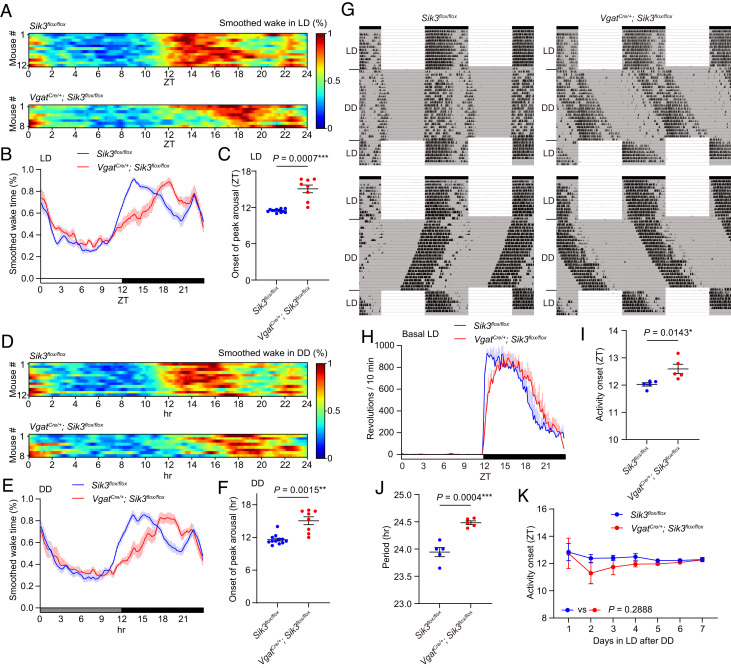

SIK3 Deficiency in GABAergic Neurons Caused a Delayed Arousal Peak and a Longer Circadian Period.

Through the course of EEG/ electromyogram (EMG)-based sleep analysis of SIK3 deficiency in specific neuron subtypes, we noticed that VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a delayed arousal peak after the beginning of the dark phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Whereas control mice exhibited a steep increase in arousal around light-off at ZT12 (onset of peak arousal in a 3-h range at zeitgeber time (ZT) 11.5 ± 0.1), VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a gradual increase during the dark phase, reaching a peak at ZT15.1 ± 0.6 (Fig. 1 A–C). Hourly NREM sleep time and REMS time of VgatCre/+; Sik3 flox/flox mice showed a gradual decrease during the dark phase which was complementary to increased wake time (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). In addition to the highest peak of arousal at the early dark phase, C57BL6 mice showed a second and lower peak of arousal at the end of the dark phase. VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice show no delay from control mice for this arousal peak (Fig. 1 A and B). VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited total wake time, total NREMS time, total REMS time, mean episode duration of NREMS, and delta power in NREMS similar to control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D–H). Thus, the only significant abnormality in sleep/wakefulness in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice was a delayed peak of arousal in the early dark phase.

Fig. 1.

VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice showed phase-delayed awakening at the dark onset and a longer circadian period (A) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (B) Mean of smoothed wake time of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (C) The onset of peak arousal of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. Welch’s t test. (D) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice on the first day in DD. (E) Mean of smoothed wake time of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice in the first day in DD. (F) The onset of peak arousal of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/floxmice in the first day in DD. Welch’s t test. (G) Representative double plots of running-wheel activity of a Sik3flox/flox mouse and a VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mouse. (H) Daily wheel revolutions per 10 min of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. (I) Activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. Welch’s t test. (J) Circadian period of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice. Unpaired t test. (K) Estimated activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice during the reentrainment LD period after DD. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA. For A–F, VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 8) and Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 12) were used. For G–K, n = 5 for each genotype was used. Data are mean ± SEM.

To examine whether light, either as a zeitgeber signal or through the extended masking effect, causes a delayed arousal peak in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice, we performed sleep/wake analysis using the first day in DD. As in LD, control mice exhibited a steep increase in arousal around the end of the subjective day (11.6 ± 0.3 h later at the end of the dark phase) (Fig. 1 D–F). However, VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a gradual increase in arousal, reaching a peak at 15.1 ± 0.7 h (Fig. 1 D–F). In DD, VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited total wake time, total NREMS time, total REMS time, mean episode duration of NREMS, and delta power in NREMS similar to control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 I–P). Thus, SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons caused a phase-delayed arousal peak under both LD and DD.

Next, we examined the circadian behavior of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice using a running wheel. VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited a longer circadian period under DD (Sik3flox/flox mice: 23.9 ± 0.1 h and VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.5 ± 0.0 h, P = 0.0004; Fig. 1 G and J). Consistent with a delayed arousal peak in the early dark phase in both LD and DD, VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited a delayed or variable activity onset after the beginning of the dark phase in LD (Fig. 1 G–I). The number of wheel revolutions of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice was reduced later in the dark phase compared to that of Sik3flox/flox mice (Fig. 1H). When LD was resumed at the original circadian timing after DD, activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice was immediately adjusted to the dark phase of LD, as did Sik3flox/flox mice (Fig. 1 G and K). In the first few days of LD, VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice showed an activity peak immediately after the beginning of the dark phase similar to Sik3flox/flox mice. Since ZT12 on the first day of the LD corresponded to the subjective dark phase on the last day of DD, this result indicates an intact masking effect of light in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice. Delayed activity onset reappeared after the fifth day after the resumption of LD (Fig. 1G). To further examine the adaptation of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice to light–dark cycle shift, light-on timing was advanced by 6 h (21). VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice started their activity earlier each day and were entrained to the 6-h advanced LD in 10 d (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). Daily advances in activity onset were similar for both VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox and Sik3flox/flox mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). When light-off timing was delayed for 6 h, the activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice was immediately shifted to the beginning of the new dark phase, as did control mice. This was likely due to a masking response to light during the dark phase of the previous LD. Delayed activity peak in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice reappeared after the fourth day after the start of the 6-h delayed LD (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). These results indicate that SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons induced a longer circadian period and phase-delayed activity/wake during the early dark phase, with almost intact entrainment to light–dark cycle shift and masking response to light.

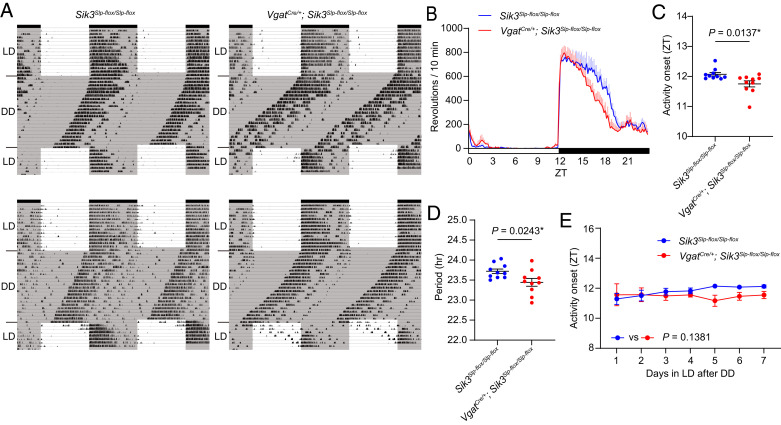

Sleepy Allele Induction in GABAergic Neurons Advanced Activity Onset and Shortened Circadian Period.

In contrast to a loss-of-function effect examined using Sik3flox mice, Sik3Slp-flox mice induce the gain-of-function allele, Sleepy (Slp), in a Cre recombinase–dependent manner (17). In wheel-running experiments, VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice exhibited advanced activity onset compared to Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice (Fig. 2 A–C). In DD, VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice showed a shorter circadian period than Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice (Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice: 23.7 ± 0.1 h and VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice: 23.4 ± 0.0 h, P = 0.0243; Fig. 2 A and D). These results are opposite to those of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice. Sleep analysis showed that the arousal peak at ZT11.2 ± 0.3 in VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice was similar to that of control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). The phase-advanced arousal of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice was only observed in the wheel-running experiment (Fig. 2C). Probably because the phase-advanced activity was easily masked by light, the difference was only detected with the running wheel which enhanced the arousal level and made the interindividual differences smaller (coefficient of variation of activity onset time with wheel running: 0.0274 and arousal peak time from sleep recording: 0.104) (22, 23). A consolidated activity bout at the early dark phase of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice was decreased earlier than that of control mice (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the light masking affected the beginning of the activity bout. After 3 wk of DD, when LD was resumed at the original circadian timing, activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice was immediately adjusted to the dark phase of LD, as did Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice (Fig. 2 A and E). Thus, Sik3(Slp) induction in GABAergic neurons has the opposite effect of SIK3 deficiency in terms of activity onset and circadian period length.

Fig. 2.

VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-floxmice showed a shorter circadian period (A) Representative double plots of running-wheel activity of a Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mouse and a VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mouse. (B) Daily wheel revolutions per 10 min of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox in basal LD. (C) Activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice in basal LD. Unpaired t test. (D) Circadian period of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice. Unpaired t test. (E) Estimated activity onset of VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-flox mice during the reentrainment LD period after DD. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA. n = 10 for each genotype. Data are mean ± SEM.

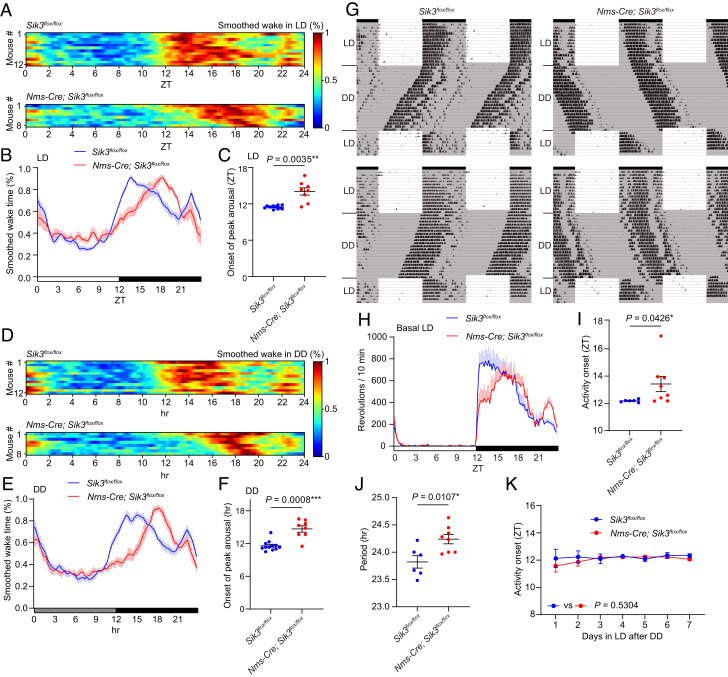

SIK3 Deficiency in NMS-Positive Neurons Caused a Delayed Arousal Peak and a Longer Circadian Period.

To further characterize neuronal groups responsible for sleep and circadian behavior changes in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice, we performed sleep and circadian behavior analysis in Nms-Cre-dependent SIK3-deficient mice. NMS-positive neurons account for 40% of SCN neurons and are essential for the pacemaker function of the SCN (5). Similar to VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice, Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a gradual increase in wake time from the dark onset, reaching an arousal peak at ZT14.0 ± 0.6, which was delayed by 2.5 h compared to control mice (same as Fig. 1A) (Fig. 3 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Hourly NREM sleep time and REMS time of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a gradual decrease during the dark phase which was complementary to increased wake time (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B and C). A delayed arousal peak was also observed under DD (Fig. 3 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S4I). Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed a second arousal peak at the end of the dark phase similar to control mice under both LD and DD (Fig. 3 A, B, D, and E). Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited total wake time, total NREMS time, total REMS time, mean episode duration of NREMS, and delta power in NREMS similar to control mice under both LD and DD (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Thus, Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited a delayed peak of arousal in the early dark phase similar to VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice.

Fig. 3.

Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice showed phase-delayed awakening at the dark onset and a longer circadian period (A) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (B) Mean of smoothed wake time of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (C) The onset of peak arousal of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. Welch’s t test. (D) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice on the first day in DD. (E) Mean of smoothed wake time of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in the first day in DD. (F) The onset of peak arousal of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice on the first day in DD. Welch’s t test. (G) Representative double plots of running-wheel activity of a Sik3flox/flox mouse and an Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mouse. (H) Daily wheel revolutions per 10 min of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. (I) Activity onset of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. Mann–Whitney U test. (J) Circadian period of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice. Unpaired t test. (K) Estimated activity onset of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice during the reentrainment LD period after DD. Mixed-effects model. For A–F, Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 8) and Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 12, same as Fig. 1 A–F) were used. For G–K, Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 6) and Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 8) were used. Data are mean ± SEM.

Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice exhibited a longer circadian period than Sik3flox/flox mice using a running-wheel activity in DD (Sik3flox/flox mice: 23.8 ± 0.1 h and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.2 ± 0.1 h, P = 0.0107; Fig. 3 G and J). In LD, Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed delayed activity onset with greater variability compared to Sik3flox/flox mice (Fig. 3 G–I). When LD was resumed at the original circadian timing after 3 wk of DD, the activity onset of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice quickly adapted to the dark phase of LD (Fig. 3O). These results indicate that SIK3 deficiency in NMS-positive neurons is sufficient to reproduce phase-delayed activity/wake during the early dark phase and a longer circadian period in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice.

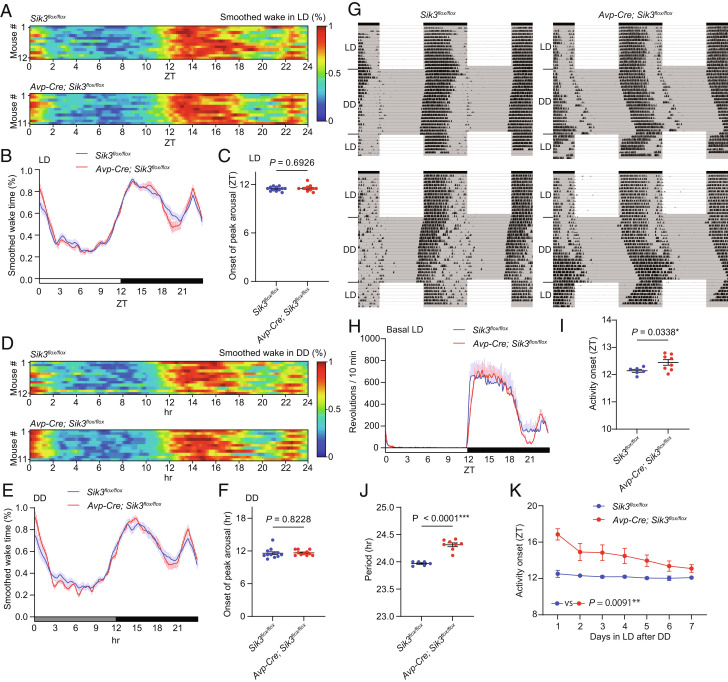

Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox Mice Did Not Show Delayed Arousal Peaks with a Longer Circadian Period.

Next, we examined mice lacking SIK3 in AVP-positive neurons which are a subpopulation of NMS-positive neurons in the SCN (9). In sharp contrast to VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice did not show any delay in arousal peak after the onset of the dark phase under LD (Fig. 4 A–C) and DD (Fig. 4 D–F). Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed no change in the total time of wakefulness, NREMS, or REMS (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–F, I–N), episode duration of NREMS (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 G–O), and delta power during NREMS (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 H–P) under LD and DD.

Fig. 4.

Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice showed a longer circadian period and normal arousal peak (A) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (B) Mean of smoothed wake time of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. (C) The onset of peak arousal of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in LD. Welch’s t test. (D) Heat maps of smoothed wake time of individual Sik3flox/flox mice and Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice on the first day in DD. (E) Mean of smoothed wake time of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice in the first day in DD. (F) The onset of peak arousal of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/floxmice on the first day in DD. Welch’s t test. (G) Representative double plots of running-wheel activity of a Sik3flox/flox mouse and an Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mouse. (H) Daily wheel revolutions per 10 min of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. (I) Activity onset of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice in basal LD. Unpaired t test. (J) Circadian period of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice. Unpaired t test. (K) Estimated activity onset of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice during the reentrainment LD period after DD. Mixed-effects model. For A–F, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 11) and Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 12, same as Fig. 1 A–F) were used. For G–K, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 6) and Sik3flox/flox mice (n = 8) were used.

Circadian behavior analysis using a running wheel showed that Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice had a longer circadian period than Sik3flox/flox mice (Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.0 ± 0.2 h and Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.3 ± 0.0 h, P < 0.0001; Fig. 4 G and J). In LD, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice showed delayed activity onset compared to Sik3flox/flox mice by only 0.3 h (Fig. 4 G–I). When Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice were released to the original LD after 3 wk of DD, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice took approximately 7 d before activity onset reached the beginning of the dark phase, whereas the activity onset of Sik3flox/flox mice immediately shifted to the beginning of the dark phase (Fig. 4O). This result may be because ZT12 on the first day of LD in Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox and Sik3flox/flox mice corresponded to the subjective day and night, respectively, on the last day of DD. Thus, SIK3 deficiency in AVP-positive neurons did not delay arousal peak at the early dark phase but had a longer circadian period.

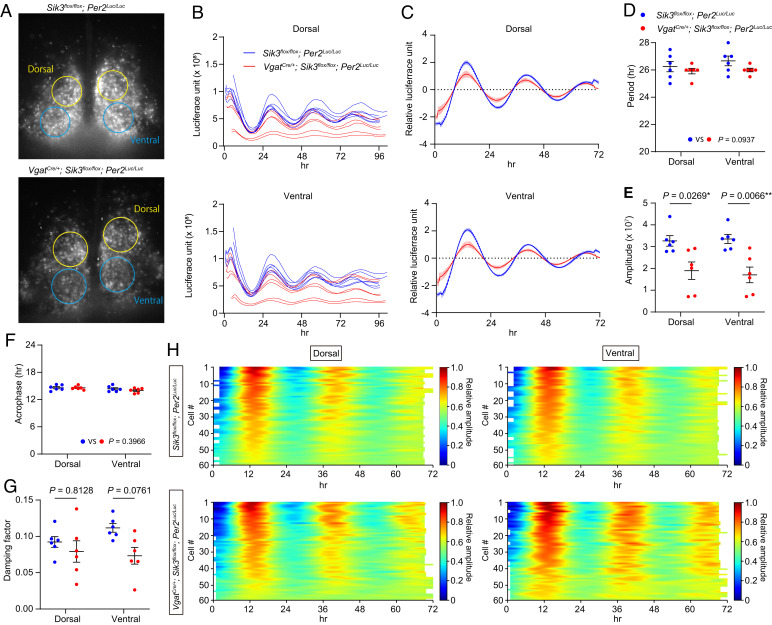

VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc Mice Showed Reduced Per2 Amplitude in the SCN.

To examine the effect of SIK3 deficiency on the oscillation of core clock genes in the SCN, we further crossed VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice with Per2Luc/Luc mice (24). After the entrainment of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice and Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice into LD, SCN slices were dissected during the light phase, and we performed real-time bioluminescence measurements using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. The SCN slices from both VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice and Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice showed robust bioluminescence throughout the recording period (Fig. 5 A–C). To compute circadian parameters of bioluminescence, we defined a region of interest (ROI) on both sides of the dorsal and ventral regions of the SCN (Fig. 5A), and the sum of the bioluminescence of each ROI was used for further analysis. Bioluminescence of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Lucslices steadily oscillated in both the dorsal and ventral parts (Fig. 5 B and C). There is no statistically significant difference in the bioluminescence period between VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices and that of Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices (Fig. 5D); however, the ventral part of the SCN had a tendency for a shorter period in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice (P = 0.1099, unpaired t test). The bioluminescence amplitude was significantly attenuated in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices, whereas the acrophase and damping factor of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices were comparable to those of Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices (Fig. 5 B, C, E, F, and G). To examine the synchronous oscillation of each cell in the SCN slices, ROIs were redefined to surround each cell in the dorsal or ventral regions of the SCN. Because each cell in the SCN slices from VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice exhibited lower amplitude than Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc slices in CCD camera image (Fig. 5A), bioluminescence intensities from each cell were normalized by the maximum amplitude of each genotype to confirm the cell oscillation. We investigated that each SCN cell of the VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice synchronously oscillated in both the dorsal and ventral parts of the SCN similar to Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice (Fig. 5H). Thus, SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons attenuated PER2 expression but did not disturb cell synchronicity in SCN slices.

Fig. 5.

Bioluminescence rhythms of the SCN explants from VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice (A) Representative image of PER2::Luciferase expression of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice and Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice at the first peak phase. Four ROIs were defined at the dorsal and ventral regions of a coronal SCN slice. The sum of the bioluminescence intensity in each ROI was calculated and used for further analysis. (B) The raw bioluminescence intensities of the SCN explants of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice. (C) Detrended and smoothed bioluminescence of the dorsal or the ventral region in the SCN of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice. Data were plotted from the next ZT0. (D–G) Calculated circadian period length (D), amplitude (E), acrophase from time point zero (F), and damping factor (G) of the dorsal or ventral region in the SCN of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. n = 6 in each genotype. Data are mean ± SEM. (H) Heat maps of PER2::Luciferase bioluminescence of individual cells in the SCN of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice. Detrended bioluminescence was normalized by the maximum amplitude in each group. n = 60 in each region and genotype.

VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox Mice Showed Phase-Delayed Clock Gene Expressions in the Liver.

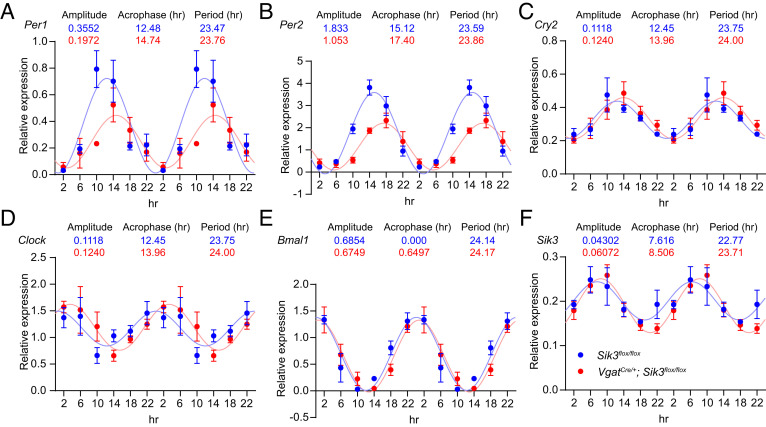

The SCN synchronizes peripheral oscillators such as liver clocks (1). To examine the effect of SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons on the peripheral core clock gene expressions, we performed qRT-PCR using the mRNA from the liver of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice harvested on the second day in DD. We confirmed that Per1, Per2, Cry2, Clock, Bmal1, and Sik3 were expressed and oscillated in the liver of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice and Sik3flox/flox mice as a control (Fig. 6). To further assess the expression amplitude, acrophase, and period of these genes, we double-plotted the expression level and conducted the cosine fitting (see “qRT-PCR” in the Materials and Methods). Per1 or Per2 amplitude of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox livers was decreased to approximately 55% of Sik3flox/flox livers (Fig. 6 A and B). The period of Per1, Per2, Cry2, Clock, and Sik3 was longer in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox livers (Fig. 6 A–D and F). The period of Bmal1 was comparable between VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox and Sik3flox/flox livers (Fig. 6E). The acrophase of all the six genes was phase-delayed in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice (Bmal1: 0.65, Sik3: 0.89, Clock and Cry2: 1.51, Per1: 2.26, and Per2: 2.28; Fig. 6). These results indicate that SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons induced lower Per amplitude and phase-delayed clock gene expression in the liver.

Fig. 6.

Core clock gene and Sik3 expression in the liver from VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice (A–F) Relative mRNA expression rhythm of Per1 (A), Per2 (B), Cry2 (C), Clock (D), Bmal1(E), and Sik3 (F) of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice were double-plotted. Pale lines indicated the simulated expression curves of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice or Sik3flox/flox mice. The equation used was y = amplitude*cos(2*pi*(x – acrophase)/period) + baseline. n = 3 in each time point and genotype. Data are mean ± SEM.

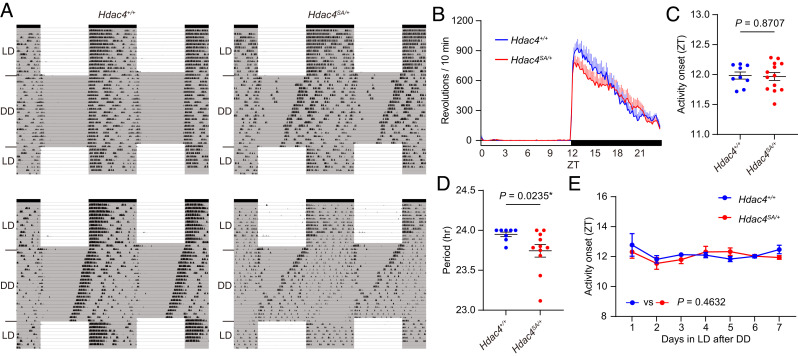

HDAC4 Regulates Circadian Length and Timing of Arousal Peak.

SIK3 phosphorylates histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), a member of the class IIa histone deacetylase, and enhances cytoplasmic localization of HDAC4, which subsequently changes gene expression (25–28). Thus, we next assessed the wheel running and sleep/wake behavior of Hdac4SA mutant mice, a model of HDAC4 haploinsufficiency (27). Hdac4SA has a splice acceptor (SA) mutation in the Hdac4 gene. The homozygous Hdac4SA mutant mice lack HDAC4 protein and exhibit severe abnormality and premature death as reported in HDAC4-deficient mice (27, 29). In the wheel-running experiment, Hdac4SA/+mice had a shorter behavioral period than Hdac4+/+mice (Hdac4+/+mice: 24.0 ± 0.0 h and Hdac4SA/+mice: 23.7 ± 0.1 h, P = 0.0235; Fig. 7 A–D), which is opposite of SIK3 deficiency. The activity onset in LD of Hdac4SA/+mice was similar to that of Hdac4+/+mice (Fig. 7 B and C). When LD was resumed at the original circadian timing after DD, the activity onset of Hdac4SA/+mice was immediately adjusted to the dark phase of LD, as did Hdac4+/+mice (Fig. 7 A–E). Sleep analysis showed that the arousal peak at ZT11.2 ± 0.1 in Hdac4SA/+mice was similar to that of control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–C). To examine the role of HDAC4 phosphorylation by SIK3, we introduced Hdac4S245A mice, in which Ser245, the target serine residue of SIK3, is substituted with alanine (27). Since Hdac4S245A mice were too small to move the running wheel smoothly, we only performed a sleep analysis of Hdac4S245A mice. The arousal peak of all the control mice was in ZT12 ± 1.5, whereas the arousal peak of five of twenty Hdac4S245A/+mice exceeded ZT14 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D). Consequently, averaged arousal peak of Hdac4S245A/+mice was significantly delayed to that of Hdac4+/+mice (Hdac4+/+mice: ZT11.3 ± 0.0 and Hdac4S245A/+mice: ZT12.7 ± 0.5, P = 0.0018; SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A–C). These results indicated that HDAC4 regulates the circadian period and arousal peak in a consistent direction with SIK3 activity.

Fig. 7.

Hdac4SA/ + mice showed a shorter circadian period (A) Representative double plots of running-wheel activity of a Hdac4+ /+ mouse and a Hdac4 SA/+ mouse. (B) Daily wheel revolutions per 10 min of Hdac4 SA/+ mice in basal LD. (C) Activity onset of Hdac4 SA/+ mice in basal LD. Unpaired t test. (D) Circadian period of Hdac4SA/+ mice. Mann–Whitney U test. (E) Estimated activity onset of Hdac4 SA/+ mice during the reentrainment LD period after DD. Mixed-effects model. Hdac4+ /+ mice (n = 9) and Hdac4 SA/+ mice (n = 13). Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

This study revealed that SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons led to a longer circadian period. Although systemic SIK3-deficient mice have been reported to have a longer circadian period (18), almost all SIK3-deficient mice died, and the surviving few showed severe growth retardation and skeletal and metabolic abnormalities (19, 20). Focusing on the activity of SIK3-deficient mice, they showed fragmented activity bouts even during the light phase (18). In contrast, the activity bouts of SIK3-deficient mice in GABAergic neurons used in this study were consolidated in an active phase similar to wild-type mice, and there were no obvious problems with these mice other than phase-delayed arousal and lengthened circadian period.

Similarly, prolonged circadian periods were found with SIK3 deletion in either NMS-positive neurons or AVP-positive neurons (Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.2 ± 0.1 hr, Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: 24.3 ± 0.0 h, and control mice: 23.9 ± 0.1 h). AVP-positive neurons constitute 20% of SCN neurons, and they are also positive for NMS (6). Furthermore, AVP-positive neurons are involved in determining the circadian period (9, 30). It is well known that, when an oscillator with a longer period length is entrained to zeitgeber signals with a shorter period, the phase of the oscillator is delayed from zeitgeber signals (31). Thus, the activity onset in wheel running of both Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice and Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice was phase-delayed. However, phase delay of Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice was more severe than that of Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice (Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: ZT13.4 ± 0.6, and Avp-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice: ZT12.4 ± 0.1). Furthermore, SIK3 deficiency in NMS-positive neurons resulted in a phase-delayed arousal peak during the early dark phase, but SIK3 deficiency in AVP-positive neurons did not. These results indicated that SIK3 in NMS-positive and AVP-negative neurons is required for robust wakefulness immediately after the light-off, which is independent of wakefulness at the end of the dark phase. Recent single-cell RNA-seq analyses demonstrated that NMS-positive neurons consist of AVP-positive neurons and VIP-positive neurons (6, 32). Thus, a delayed arousal peak during the dark phase, which was observed in SIK3 deficiency in NMS-positive neurons but not in SIK3 deficiency in AVP-positive neurons, is thought to be due to SIK3 deficiency in VIP-positive neurons. VIP-positive neurons account for 10% of SCN neurons and are involved in light-mediated circadian phase shift (33) and are required for circadian rhythmicity under DD (32). Furthermore, an intact VIP signaling is required for the circadian period regulation (32, 34–36). Considering the trend that the bioluminescence period was more affected in the ventral part of the SCN by the SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons, it is impossible to reject the possibility that VIP-positive neurons are involved in circadian period length regulation through SIK3 signaling. To investigate in detail the contributions of the subpopulations in the NMS-positive neurons for SIK3-dependent circadian period and arousal timing regulations, further experiments will be useful with mice lacking SIK3 specifically in VIP-positive neurons in the SCN but maintaining normal expression levels of VIP itself.

Genetic manipulations of SIK3 in GABAergic neurons indicate that SIK3 acts to shorten the circadian period length. Since SIK3 phosphorylates HDAC4 and suppresses the nuclear localization of HDAC4 (25, 26), if the SIK3–HDAC4 pathway is involved in circadian behavior control, nuclear HDAC4 may work to lengthen the circadian cycle, which may be reversed when HDAC4 is greatly reduced. As expected, heterozygous HDAC4-deficient mice exhibited a shorter circadian period, whereas mice with a phosphorylation-defective mutation in HDAC4, resistant to phosphorylation by SIK3, showed a delayed arousal peak. In addition, mice deficient in MEF2D, which HDAC4 binds to regulate the expression of target genes, showed a longer circadian period and delayed arousal peak during the onset of the dark phase (37) similar to VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice and Nms-Cre; Sik3flox/flox mice. Thus, SIK3–HDAC4 signaling may regulate circadian behavior and arousal peak phase. Recently, NPAS4-deficient mice were reported to show a prolonged circadian period and a delayed or unstable activity onset during LD (38). Since HDAC5, a close paralog of HDAC4 and another substrate of SIK3, can suppress NPAS4 (39), SIK3 may exert its effects on circadian behavior through HDAC4/5–NPAS4. Thus, the SIK3–HDAC4/5 pathway may regulate the circadian period and arousal peak phase through positive transcription regulators like MEF2D and NPAS4.

Core clock genes in the liver of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice were phase-delayed compared with the control mice in DD. Surprisingly, phase difference and molecular period change were not detected in the SCN explants from VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice, although phase delay in arousal peak was observed in VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox mice in LD. It is important to note that there is a difference in PER2 protein between experiments, an intact PER2 protein for in vivo behavioral analyses and a PER2::Luciferase fusion protein for SCN explant experiments. SIK3 enhances the phosphorylation and degradation of PER2 directly or indirectly (18). However, PER2::Luciferase signals from the SIK3-deficient SCN were not increased but rather decreased (Fig. 5B). A plausible possibility is that PER2::Luciferase fusion protein has a reduced sensitivity to phosphorylation, including that mediated by SIK3 compared with intact PER2. Considering the subtle circadian phenotypes of Hdac4 mutant mice, SIK3 acts to shorten the circadian period through both a fast PER2 phosphorylation process and relatively slow transcriptional regulation. Also, there remain the possibilities that some non-SCN intrinsic factors mediating the SIK3 pathway–dependent regulation in period length and phase angle may be missing in the SCN explants or that the SCN explants of VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice may exhibit an aftereffect of previous LD (37).

In the SCN, both Sik1 and Sik3 are induced by light stimulation (38), and SIK1 is involved in behavioral phase shifts following a jet lag (21). However, SIK3 deficiency in GABAergic neurons did not affect the daily advance of the activity onset after a jet lag. Since Sik1 is induced 30 min after the light pulse while Sik3 is induced 3 h later (38), SIK3 has a different role in the light response than SIK1. In addition, SIK1-inactive knock-in mice showed normal behavioral periods (40).

Endogenous SIK3 in the SCN, composed of GABAergic neurons, regulated arousal peak timing and circadian oscillation without affecting total sleep amount and depth. These results replicated the fact that GABAergic neurons do not affect sleep amount or depth via SIK3 (27). Interestingly, the downstream target molecule of SIK3-dependent sleep regulation is HDAC4/5, which is executed by glutamatergic neurons (27, 28). Thus, the SIK3–HDAC4 signaling pathway contributes to the sleep/wake architecture through both processes, sleep homeostasis regulation via glutamatergic neurons and circadian rhythm regulation via GABAergic neurons.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All animal experimental procedures were approved and conducted following the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tsukuba (approved protocol ID #22-345). Mice were bred under controlled temperature and humidity conditions (23 ± 2 °C and 55 ± 5% humidity) and maintained on a 12-h light:12-h dark cycle with a white fluorescent lamp as the light source. Food and water access was allowed ad libitum. VgatCre (Slc32a1tm2(cre)Lowl/J, Jackson Laboratory #016962, MGI:5141270), Nms-Cre (C57BL/6-Tg(Nms-icre)20Ywa/J, Jackson Laboratory #027205, MGI:5638418), Avp-Cre (Tg(Avp-icre)#Meid, MGI:5697941), Per2Luc (B6.129S6-Per2tm1Jt/J, Jackson Laboratory #:006852, MGI:3040876), and Sik3Slp-flox (Sik3tm2.1Iiis, MGI:6506974) were used. Sik3flox mice, Hdac4SA, and Hdac4S245A were generated by Kim et al. (27).

Circadian Behavioral Analysis.

Instruments for measuring circadian behavior were the same as previously reported (41). Male mice aged 11 to 24 wk old were individually housed in a cage located with a wireless running wheel (Med Associates #ENV-047). The revolutions of wheels were recorded by Wheel Manager software (Med Associates) via a receiving device (Med Associates #DIG807). The mice were habituated to the running wheel under LD for at least 7 d just before recording. Except for Hdac4SA/+ mice, a green light emitting diode (LED) was used as the light source. The wheel-running experiments of Hdac4SA/+ mice were conducted under white fluorescent light. Basal revolutions were measured under LD for more than 13 d, and then mice were released into DD for at least 21 d to measure the free-running period. Finally, mice were returned to the original LD for more than 6 d. The revolutions were recorded every minute. Except for Hdac4SA/+ mice, the circadian period was calculated by χ2 periodogram from days 7 to 21 in DD. The circadian period of Hdac4SA/+ mice was calculated using the whole recording days in DD due to the system problem of the wireless receiver that happened during DD. The data from one Hdac4+/+ mouse and two Hdac4SA/+ mice were removed because the numbers of recording days were not enough to reach the significance of χ2 periodogram. The activity onset for wheel running was defined as the time point when the gap of the sum of the total revolutions before and after 6 h from the candidate bins reached the maximum. For the jet lag experiment, a wheel-running behavior was measured under the 12-h light:12-h dark cycle for 10 d followed by 6 h of light advance. Mice were maintained in the shifted light–dark cycles for 10 d. Then, mice were challenged to a 6-h dark delay and wheel-running activity measured for 10 d. The daily shift was calculated by subtracting the mean activity onset during the previous LD from each activity onset after the 6-h light advance. Periodogram computation, activity onset estimation, and actogram visualization were performed using Python.

EEG/EMG Electrode Implantation Surgery.

EEG/EMG electrodes containing four electrode pins and two flexible stainless steel wires were implanted into 8- to 10-wk-old male mice as previously described (42, 43). Surgery was performed under stereotaxis control with isoflurane anesthesia (4% for induction and 2% for maintenance). Four electrode pins were implanted at the posterior locations (ML: ±1.27 mm just anterior side of lambdoid sutures) and at 5.03 mm anterior side of the posterior locations. Two ipsilateral pins were used for EEG recording. The electrode was fixed to the skull with dental cement (3M ESPE, RelyX U200 Unicem Syringe Dental Resin Cement), and then, the two EMG wires were inserted into the neck extensor muscles. All mice were allowed at least a 5-d recovery from the surgery. After the recovery period, all mice were housed individually and attached to a tether cable to habituate to the connected condition for more than 7 d. Habituation was performed under the 12-h light:12-h dark cycle with green LED light as the light source, same as the recording condition.

EEG/EMG Recording and Analysis.

EEG/EMG recording and analysis were performed as previously described with some modifications (42, 43). EEG/EMG signals were continuously recorded for 48 h, of which the first 24 h was under the 12-h light:12-h dark condition and followed by 24-h constant dark condition. EEG and EMG signals were amplified and filtered (EEG: 0.3 to 300 Hz and EMG: 30 to 300 Hz) with a multichannel amplifier (NIHON KODEN, #AB-611J) and sampled at 250 Hz with an analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments #PCI-6220). The EEG/EMG data were visualized and semiautomatically analyzed by MATLAB-based software followed by visual inspection. A 20-s bin was used to determine wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep. Wakefulness was scored based on the low-amplitude, fast EEG and vigorous or variable EMG. NREMS was determined based on delta (1 to 4 Hz) frequency dominant, high-amplitude EEG, and low EMG activity. REMS was characterized by theta (6 to 9 Hz) frequency dominant, delta frequency diminished, low-amplitude EEG, and EMG atonia. The total time spent in wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep was calculated by summing the total number of 20-s bins in each state. NREMS episode durations were computed by dividing the total time spent in NREMS by the number of NREMS episodes. Epochs with artifacts were included in the time spent analysis but excluded from subsequent spectral analysis. To analyze the EEG spectra, EEG signals were subjected to fast Fourier transform analysis using MATLAB-based custom software, and power spectra of 1 to 30 Hz with 1-Hz bins in each 20-s epoch were calculated. NREMS delta density was the average of the normalized delta power, which was the ratio of delta power to the total EEG power in each epoch of NREMS. To examine the onset of peak arousal, the sum of the wake time in 10-min bin was calculated and then smoothed with 3-h moving average. Smoothed values were normalized by the maximum values in each mouse and then binarized by the mean value of the smoothed wake time. An onset of peak arousal was determined as the latency to the longest consecutive period of threshold exceedance from ZT0 or the beginning of DD. The onset of peak arousal of VgatCre/+; Sik3+/+mice, VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/+mice, VgatCre/+; Sik3Slp-flox/Slp-floxmice, Hdac4+/+ mice, Hdac4SA/+ mice, and Hdac4S245A/+ mice was reanalyzed using the data in Kim et al. (27).

SCN Slice Culture and Bioluminescence Analysis.

VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice and Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice were used. Mice were maintained in the 12-h light:12-h dark cycle with a white fluorescent lamp as the light source. Male mice aged 14 to 22 wk old were harvested between ZT5 and ZT10. Then, 150-µm-thick coronal brain slices were prepared using Vibratome (Leica VT1200S). A pair of mid-rostrocaudal SCN were dissected and cultured at 37 °C on a Millicell Cell Culture Insert (Millipore PICM0RG50) in a sealed 35-mm dish containing 1.5 mL recording medium (phenol red–free DMEM (SIGMA D2902), 10 mM HEPES, and 3.5 g/L D-glucose, pH 7.0) supplemented with 0.42 mM NaHCO3, 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Wako 168-23191), 2% B-27 supplements (Gibco), and 0.2 mM D-luciferin potassium salt (Wako). Bioluminescence from the SCN slices was detected using a CCD camera (Cellgraph, AB-3000D) at a 20-min exposure time with a 10-min interval for 4 d. One SCN slice from VgatCre/+; Sik3flox/flox; Per2Luc/Luc mice was excluded from further analysis because it only covered the posterior edge of the SCN and bioluminescence faded during recording. Four points of ROI were defined in the dorsal medial and ventral medial parts of one pair of the SCN slice. The sum of the bioluminescence intensity in each ROI was calculated and accompanied by circadian parameter computation using Python. Bioluminescence values were detrended by subtracting 24-h moving average values, and then data were smoothened with a Savitzky–Golay filter (12-h window, cubic polynomial) in SciPy. Values from the next ZT0 were used for analysis. The middle of the time points in which the smoothed values crossed value 0 upward and downward was defined as peak phases as previously reported (44). Significant oscillation was defined as a 6-h mean value of around the first peak that was two SD further than the average of detrended values. The period was calculated as the difference between two adjacent peak phases. The amplitude was the sum of the absorbed value of the first peak and the subsequent trough. The acrophase was defined as the latency to the first peak from ZT0. The damping factor was calculated using the values of the first peak and the second peak.

To confirm the synchronization of individual cells, forty points of circular ROI were redefined in the SCN slice (20 ROIs in the dorsal part and 20 ROIs in the ventral part). ROIs enclosed one cell at the beginning of the successive image; however, ROIs were not traced to each cell because it was hard to distinguish one cell from others due to the high density of cells and fading luminescence. Bioluminescence from each ROI was normalized with the maximum value of each group and visualized as the heat map using Python.

qRT-PCR.

Livers of 9- to 14-wk-old male mice were harvested at the specific time of the second day under DD. Total RNA was prepared using Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen) and QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed with an oligo dT primer and PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase Kit (TaKaRa). Synthesized cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR (ViiA7; ThermoFisher) using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa) and gene-specific primers. The expression levels were normalized with the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) gene. The primers used were Per1, Clock, Bmal1, Cry2 (ref. 45), Per2-Fw (5′-GTGTT GAAGG AGGAC CAGGA-3′), Per2-Rv (5′-AAACA CAGCC TGTCA CATCG), Sik3-Fw (5′-AGCGC CAGTC AGATT CAGAT-3′), Sik3-Rv (5′-CGTAG TTGGC AGGGG AGAA-3′), Gapdh-Fw (5′-AGAAC ATCAT CCCTG CATCC-3′), and Gapdh-Rv (5′-CACAT TGGGG GTAGG AACAC-3′).

To calculate the wavelength, acrophase, and amplitude, mRNA expression levels were double-plotted, and cosine fitting was performed using a customized nonlinear regression method in GraphPad Prism 9.3.1. The equation used was y = amplitude*cos(2*pi*(x – acrophase)/period) + baseline, and the equation satisfies the following conditions: period > 22, amplitude > 0, and baseline > 0. The acrophase range was 0 ≦ acrophase < 24. The goodness of fitting was assessed by R squared.

Statistical Analysis.

Two-way ANOVA or two-way repeated measure ANOVA was used for two-factor data. Mixed-effects model was applied for the two-factorial repeated measured data with missing values instead of the two-way repeated measure ANOVA. In pairwise comparison, we first visually confirmed normality and homoscedasticity of the data through the plot. An unpaired t test was used for the pairwise comparison with normal distribution and equal variance. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied if the data seemed not to follow Gaussian distribution. When the data followed Gaussian distribution but the variance was not equal, we used two-tailed Welch’s t test. Tukey’s multiple comparisons were used for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were expressed as mean with SEM. Graph visualization and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Hitoshi Okamoto from RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS)-Kao Collaboration Center for contribution to Avp-Cre mice generation, Joseph S. Takahashi from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for discussing the data, all Y/F laboratory members and International Institute for Integrative Sleep Medicine (IIIS) members, especially Takehiro Miyazaki, and Kumi Ebihara for technical support. This work was supported by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to M.Y., Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (17H06095 and 22H04918 to M.Y. and H.F.; 17H04023, 17H05583, and 20H00567 to H.F.; 26507003 and 18968064 to C.M. and H.F.; 15J00393 and 18J21517 to F.A., and 18K14811 to T.F.), Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) (JPMJCR1655 to M.Y.), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP21zf0127005 to M.Y.), JSPS DC2 17J07957 to S.J.K., University of Tsukuba Basic Research Support Program Type A to S.J.K., and Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST Program) from JSPS to M.Y.

Author contributions

F.A., H.F., and M.Y. designed research; F.A., S.J.K., T.F., C.M., N.H.-H., N.A., K.I., and M.K. performed research; F.A., T.F., C.M., S.M., M.M., F.S., and S.T. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; F.A., S.S. and A.H. analyzed data; and F.A., H.F., and M.Y. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: Y.F., University of Tokyo; and L.P., University of California San Francisco.

Contributor Information

Hiromasa Funato, Email: funato.hiromasa.km@u.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Masashi Yanagisawa, Email: yanagisawa.masa.fu@u.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Source data to support these findings are available in figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22138214.v1) (46). The python scripts used in this paper are available on GitHub (https://github.com/fuyuki-asano/circadian_analysis) (47).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Mohawk J. A., Green C. B., Takahashi J. S., Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 445–462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastings M. H., Maywood E. S., Brancaccio M., Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 453–469 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan L., Expression of clock genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: effect of environmental lighting conditions. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 10, 301–310 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog E. D., Hermanstyne T., Smyllie N. J., Hastings M. H., Regulating the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SVN) circadian clockwork: Interplay between cell-autonomous and circuit-level mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a027706 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee I. T., et al. , Neuromedin s-producing neurons act as essential pacemakers in the suprachiasmatic nucleus to couple clock neurons and dictate circadian rhythms. Neuron 85, 1086–1102 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen S., et al. , Spatiotemporal single-cell analysis of gene expression in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 456–467 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maywood E. S., Chesham J. E., O’Brien J. A., Hastings M. H., A diversity of paracrine signals sustains molecular circadian cycling in suprachiasmatic nucleus circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14306–14311 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi Y., et al. , Mice genetically deficient in vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors are resistant to jet lag. Science 342, 85–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mieda M., et al. , Cellular clocks in AVP neurons of the SCN are critical for interneuronal coupling regulating circadian behavior rhythm. Neuron 85, 1103–1116 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards M. D., Brancaccio M., Chesham J. E., Maywood E. S., Hastings M. H., Rhythmic expression of cryptochrome induces the circadian clock of arrhythmic suprachiasmatic nuclei through arginine vasopressin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2732–2737 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono D., Honma K.-I., Honma S., Roles of neuropeptides, VIP and AVP, in the mammalian central circadian clock. Front. Neurosci. 15, 650154 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ono D., et al. , The mammalian circadian pacemaker regulates wakefulness via CRF neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd0384 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins B., et al. , Circadian VIPergic neurons of the suprachiasmatic nuclei sculpt the sleep-wake cycle. Neuron 108, 486–499.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi J. S., Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 164–179 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funato H., et al. , Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice. Nature 539, 378–383 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda T., et al. , A single phosphorylation site of SIK3 regulates daily sleep amounts and sleep need in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10458–10463 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki K., et al. , Induction of mutant Sik3Sleepy allele in neurons in late infancy increases sleep need. J. Neurosci. 41, 2733–2746 (2021), 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1004-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayasaka N., et al. , Salt-inducible kinase 3 regulates the mammalian circadian clock by destabilizing PER2 protein. Elife 6, e24779 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uebi T., et al. , Involvement of SIK3 in glucose and lipid homeostasis in mice. PLoS One 7, e37803 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasagawa S., et al. , SIK3 is essential for chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletal development in mice. Development 139, 1153–1163 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagannath A., et al. , The CRTC1-SIK1 pathway regulates entrainment of the circadian clock. Cell 154, 1100–1111 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edgar D. M., Kilduff T. S., Martin C. E., Dement W. C., Influence of running wheel activity on free-running sleep/wake and drinking circadian rhythms in mice. Physiol. Behav. 50, 373–378 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milinski L., et al. , Waking experience modulates sleep need in mice. BMC Biol. 19, 65 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo S.-H., et al. , PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5339–5346 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walkinshaw D. R., et al. , The tumor suppressor kinase LKB1 activates the downstream kinases SIK2 and SIK3 to stimulate nuclear export of class IIa histone deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9345–9362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park S.-Y., Kim J.-S., A short guide to histone deacetylases including recent progress on class II enzymes. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 204–212 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S. J., et al. , Kinase signalling in excitatory neurons regulates sleep quantity and depth. Nature 612, 512–518 (2022), 10.1038/s41586-022-05450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou R., et al. , A signalling pathway for transcriptional regulation of sleep amount in mice. Nature 612, 519–527 (2022), 10.1038/s41586-022-05510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vega R. B., et al. , Histone deacetylase 4 controls chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletogenesis. Cell 119, 555–566 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mieda M., Okamoto H., Sakurai T., Manipulating the cellular circadian period of Arginine Vasopressin neurons alters the behavioral circadian period. Curr. Biol. 26, 2535–2542 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aschoff J., Endocrine Rhythms (Krieger Raven Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todd W. D., et al. , Suprachiasmatic VIP neurons are required for normal circadian rhythmicity and comprised of molecularly distinct subpopulations. Nat. Commun. 11, 4410 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones J. R., Simon T., Lones L., Herzog E. D., SCN VIP neurons are essential for normal light-mediated resetting of the circadian system. J. Neurosci. 38, 7986–7995 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colwell C. S., et al. , Disrupted circadian rhythms in VIP- and PHI-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 285, R939–R949 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng A. H., Fung S. W., Cheng H.-Y.M., Limitations of the Avp-IRES2-Cre (JAX #023530) and VIP-IRES-Cre (JAX #010908) models for chronobiological investigations. J. Biol. Rhythms 34, 634–644 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joye D. A. M., et al. , Reduced VIP expression affects circadian clock function in VIP-IRES-CRE mice (JAX 010908). J. Biol. Rhythms 35, 340–352 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohawk J. A., et al. , Neuronal myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D) is required for normal circadian and sleep behavior in mice. J. Neurosci. 39, 7958–7967 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu P., et al. , NPAS4 regulates the transcriptional response of the suprachiasmatic nucleus to light and circadian behavior. Neuron 109, 3268–3282.e6 (2021), 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taniguchi M., et al. , HDAC5 and its target gene, Npas4, function in the nucleus accumbens to regulate cocaine-conditioned behaviors. Neuron 96, 130–144.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor L., et al. , Light regulated SIK1 remodels the synaptic phosphoproteome to induce sleep. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2021), 10.1101/2021.09.28.462159 (Accessed 17 February 2022). [DOI]

- 41.Park M., et al. , Loss of the conserved PKA sites of SIK1 and SIK2 increases sleep need. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyoshi C., et al. , Methodology and theoretical basis of forward genetic screening for sleep/wakefulness in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 16062–16067 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwasaki K., Hotta-Hirashima N., Funato H., Yanagisawa M., Protocol for sleep analysis in the brain of genetically modified adult mice. STAR Protoc. 2, 100982 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maejima T., et al. , GABA from vasopressin neurons regulates the time at which suprachiasmatic nucleus molecular clocks enable circadian behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2010168118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirano A., et al. , In vivo role of phosphorylation of cryptochrome 2 in the mouse circadian clock. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 4464–4473 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asano F., et al. , SIK3–HDAC4 in the suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates the timing of arousal at the dark onset and circadian period in mice. Figshare. https://figshare.com/ndownloader/articles/22138214/versions/1. Deposited 22 February 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Asano F.. Circadian Analysis. GitHub. https://github.com/fuyukiasano/circadian_analysis/archive/refs/heads/master.zip. Deposited 24 February 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix. Source data to support these findings are available in figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22138214.v1) (46). The python scripts used in this paper are available on GitHub (https://github.com/fuyuki-asano/circadian_analysis) (47).