Psychiatric research is greatly in need of a coherent phenotypic model of psychopathology, by which we mean a model encompassing the manifest signs and symptoms that lead patients to seek psychiatric services. A model of these signs and symptoms is needed because they constitute the problematic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are the foci of psychiatric practice and research.

The DSM-5 nominally serves this purpose, as revealed by the papers in this special issue, which are largely framed by extant DSM rubrics. Nevertheless, DSM categories generally fail to provide a workable overall model, as is widely recognized in contemporary research and scholarship. Indeed, this failure is the reason this special issue was assembled. That is, the articles in this issue, which is focused on convergence and heterogeneity in psychiatric pathophysiology, show how categorical psychiatric rubrics are associated with problems such as comorbidity (most patients meeting criteria for one disorder also meet criteria for other disorders) and heterogeneity (persons meeting criteria for a specific disorder are markedly heterogeneous in clinically important features, including symptoms, course, and prognosis).

Other authoritative entities could, in theory, step in to help rectify the shortcomings of DSM categories–for example, the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), via efforts such as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project. Nevertheless, NIMH’s RDoC aims to circumvent the critical task of articulating a formal phenotypic model of psychopathology by explicitly setting it aside. According to the RDoC website: “RDoC is not meant to serve as a diagnostic guide, nor is it intended to replace current diagnostic systems” (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/about-rdoc.shtml). The presumption of RDoC seems to be that a thorough understanding of underlying “psychological/biological systems” will lead inexorably to an understanding of the manifest signs and symptoms of psychopathology. The articles in this issue, however, underline the inevitable entanglement of biotechnological insights with manifest signs and symptoms, assessed in traditional ways (e.g., via patient reports, as recorded by interviewing patients), that lead patients to seek treatment. The articles are focused on problems such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, and dementia (constructs designed to describe reasons people seek treatment), as well as on the promise of novel technologies to delineate pathophysiological features associated with the reasons people seek treatment. Patients do not arrive at psychiatric clinics complaining of “dysfunction in general psychological/biological systems,” to use the exact language RDoC uses to describe the foci of the RDoC project.

Underlying neurobiological processes are critically important to understand if we are to make progress in delineating the etiology and pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. However, they need to be linked back to a model that describes and classifies the manifest behavioral signs and symptoms that lead patients to seek psychiatric services. Given the problems with the DSM and the ways in which the RDoC project is more interested in “underlying systems” than in the problems that lead patients to seek treatment, what are some features of a useful phenotypic model? We argue that there are three critical features, derived from extensive evidence already accumulated in the scientific literature. These are 1) an explicit recognition of the dimensional nature of psychopathological variation; 2) a recognition that phenotypes vary systematically in their breadth versus specificity (i.e., a workable model needs to be hierarchical); and 3) a means of demarcating distinctions between human variation per se and variations involved in the cybernetic dysfunctions that are the hallmarks of mental disorder.

Given space limitations, we direct readers elsewhere regarding the details of the research and scholarship that supports the central importance of these three features. In particular, we direct readers to recent papers connected with the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) consortium, because this consortium is explicitly focused on the development of an empirically derived dimensional and hierarchical model of psychopathology (1,2). Indeed, recent HiTOP publications focus on genetics (3) and neurobiology (4)–major foci of research in biological psychiatry.

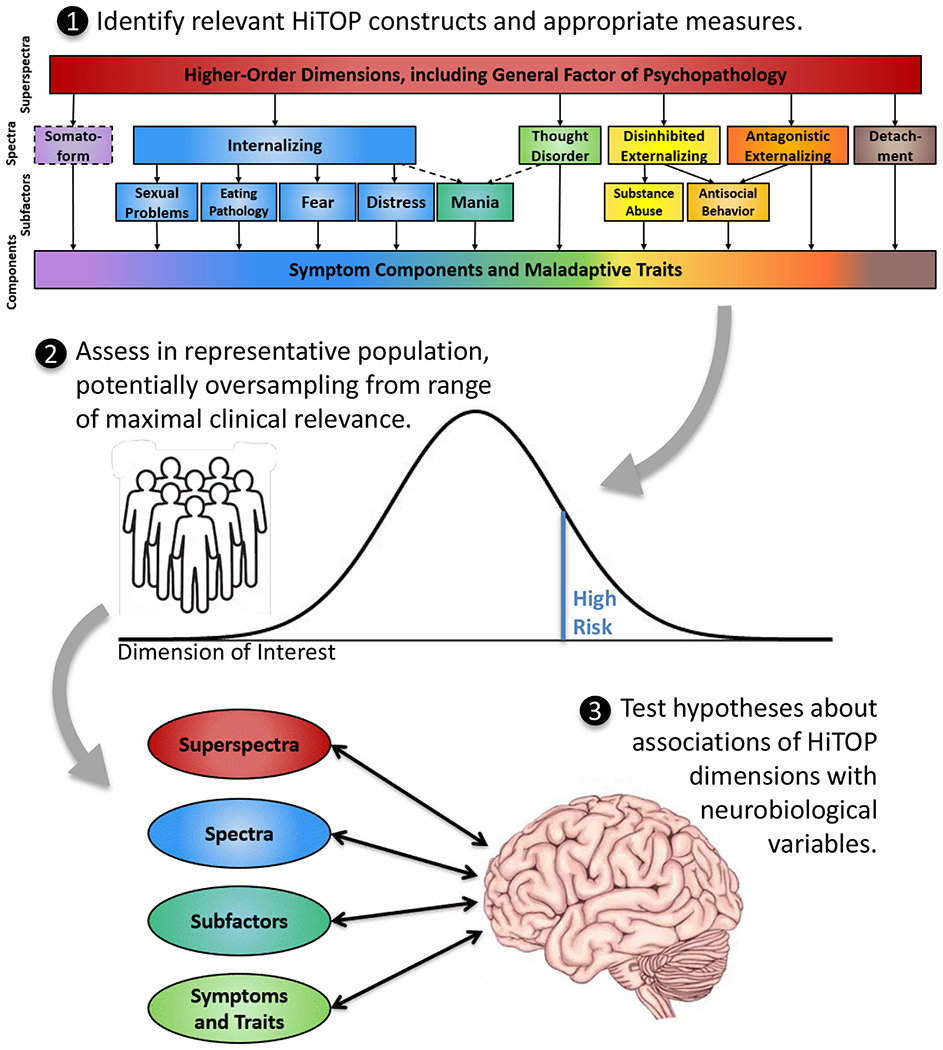

The biological research strategy associated with HiTOP is shown in Figure 1. The working HiTOP model organizes psychiatric signs and symptoms into dimensions of variation that range from broad spectra [e.g., general psychopathology (5)] to specific symptoms (6). With this approach, it becomes possible to understand whether a specific psychobiological variable is associated with psychopathology in general, a specific spectrum of psychopathology, or a specific narrow symptom.

Figure 1.

Using the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) in clinical neuroscience. Recent efforts by an international consortium of researchers have led to HiTOP, a consensual dimensional system (https://medicine.stonybrookmedicine.edu/HITOP/). Step 1 shows a simplified schematic of the HiTOP working model from which clinical phenotypes should be selected for study. (HiTOP is a work in progress and will be updated on the basis of new data. Dashed lines indicate provisional elements that require more study.) Step 2 shows a sampling design that is appropriate for HiTOP-based research, which involves sampling from unselected patient populations or the general population, rather than a case-control design, although researchers may wish to oversample participants who are manifesting or who are at high risk for the problems of interest. Step 3 shows testing associations between HiTOP phenotypes and neurobiological variables, ideally examining constructs at multiple levels of the hierarchy, examining constructs from multiple spectra to assess discriminant validity, and using latent variable modeling when possible. [Reproduced with permission from Latzman et al. (4).]

Regarding the third feature (the distinction between human behavioral variation per se and the concept of mental disorder), we have elsewhere described a cybernetic theory of psychopathology (7). Briefly, strategies such as the one shown in Figure 1 are essential in understanding associations between specific biological correlates and various levels of the dimensional psychopathology hierarchy. However, such strategies do not deal explicitly with the distinction between human variation and the kinds of dysfunction that constitute mental disorder. Behavioral deviation is typically an important feature of psychopathology, but it is not sufficient either to identify the presence of psychopathology as such or to define “disorder.” Rather, we have argued that the hallmark of psychopathology is cybernetic dysfunction, defined as persistent failure to move toward one’s goals, due to failure to generate effective new goals, interpretations, or strategies when existing ones prove unsuccessful. This definition aids in understanding how behavioral deviation may or may not result in disorder. For example, a faith healer might perceive the world in ways that are statistically unusual (e.g., experiencing levels of thought disorder that are not characteristic of most people, such as marked magical thinking and auditory hallucinations). Yet this faith healer’s experiences might be valued, or even prized, in specific cultural contexts and therefore cause them no dysfunction. Thus, levels of the dimensions in Figure 1 are not sufficient to identify mental disorder per se, because those levels must be accompanied by failure in pursuit of life goals in order to conclude that a mental disorder is present.

To conclude, we emphasize that this commentary represents our views on the matters at hand, not the perspective of a specific authoritative entity or consortium. For example, although both of us have been involved in specific organized efforts to model psychopathology, including the HiTOP consortium, our views here are not necessarily the views of the consortium. We welcome challenges to our perspective and vigorous debates about the merits of various pathways forward. Patients and their families expect no less from us in our efforts to ameliorate the considerable human suffering that accompanies psychopathology in contemporary societies.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

RFK was partially supported by National Institute on Aging Grant Nos. R01AG053217 and U19AG051426.

Footnotes

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, et al. (2018): Progress in achieving empirical classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry 17:282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, et al. (2017): The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol 126:454–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waszczuk MA, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Shackman AJ, Waldman ID, Zald DG, et al. (2020): Redefining phenotypes to advance psychiatric genetics: Implications from hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 129:143–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latzman RD, DeYoung CG, HiTOP Neurobiological Foundations Workgroup (2020): Using empirically-derived dimensional phenotypes to accelerate clinical neuroscience: The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) framework. Neuropsychopharmacology 45:1083–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornovalova MA, Choate AM, Fatimah H, Petersen KJ, Wiernik BM (2020): Appropriate use of bifactor analysis in psychopathology research: Appreciating benefits and limitations. Biol Psychiatry 88:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feczko E, Fair DA (2020): Methods and challenges for assessing heterogeneity. Biol Psychiatry 88:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeYoung CG, Krueger RF (2018): A cybernetic theory of psychopathology. Psychological Inquiry 29:117–138. [Google Scholar]