Abstract

Objective:

Explanations for associations between social norms and drinking often focus on wanting to fit in, gain social approval, and/or avoid social exclusion. From this perspective, students who believe that drinking is strongly linked to social approval should be more motivated to drink, especially if their sense of social approval or belongingness in college is low. To evaluate this hypothesis, we examined changes in drinking as a function of fluctuations in perceived injunctive norms (i.e., perceptions of others’ approval of drinking) and belongingness (i.e., one’s sense of social belonging in college).

Method:

Participants included 383 (60% women) nonabstaining students who, beginning in their first or second year of college, completed assessments every 3 months over a 2-year period. Data were analyzed using multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial models followed by marginal tests to evaluate nonlinear interactions.

Results:

Within-person results indicated that when individuals believed other students were more approving of alcohol, they subsequently increased their drinking, which is especially true when individuals’ sense of belongingness was at or below average. Between-person effects revealed overall positive associations of injunctive norms and belongingness with drinking. In addition, greater alcohol consumption among individuals with higher injunctive norms was less evident among students with lower average levels of belongingness.

Conclusions:

Perceiving others as more approving of drinking corresponds to increased drinking only when personal levels of belongingness are at or below average. Elevated feelings of belongingness may buffer social influences on drinking.

Keywords: belongingness, approval, adjustment, alcohol, social

College students’ drinking behavior is influenced by perceptions of how much and how often other students drink (descriptive norms) and by perceptions of how much others approve of drinking (injunctive norms; Borsari & Carey, 2003; Neighbors et al., 2007). However, the strength and consistency of associations between injunctive norms and drinking, the focus of the present article, have varied across studies. The present study examined belongingness as a moderator of the association between injunctive norms and drinking.

Alcohol and Perceived Norms in College

Alcohol consumption patterns over the life course have remained relatively consistent in the United States (Greenfield & Kerr, 2003; Keyes & Miech, 2013). On average, alcohol consumption increases in the late teens, with heavy drinking peaking in the early 20s and gradually declining after that (Casswell et al., 2002; Maggs et al., 2013; Masten et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2005). The college years typically occur during the ages at which individuals drink the most, yet the college environment has a unique impact on heavy drinking (Merrill & Carey, 2016; White et al., 2005). In particular, among college students, perceptions of how much and how often other students drink and perceptions of the extent to which close others (e.g., friends and family) approve of drinking (perceived injunctive norms) are strongly associated with one’s own drinking (Baer et al., 1991; Borsari & Carey, 2003; Collins & Spelman, 2013; Hagler et al., 2017; Krieger et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2015; Stappenbeck et al., 2010).

A closer examination of the association between injunctive norms and drinking reveals that consistent positive findings are evident when the reference group is close others (e.g., friends, parents, members of one’s group) but mixed when referring to more distal others (e.g., other college students of the same sex; Collins & Spelman, 2013; LaBrie et al., 2010; Larimer et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2008; Prentice & Miller, 1993). This is consistent with the broader recognition that individuals are more likely to adhere to the norms of groups with which they more strongly identify (Hogg & Reid, 2006). Most examinations of associations between injunctive norms and drinking have been cross-sectional. In studies where injunctive norms and drinking have been examined at multiple time points, results have shown consistent within-person associations (DiGuiseppi et al., 2020; Graupensperger et al., 2020, 2021), but few of these have examined prospective associations (Lewis et al., 2015). Incorporating the construct of belongingness has the potential to broaden the theoretical framework underlying the influence of injunctive norms by helping to explain for whom and when students may be especially attentive to how closely their behavior aligns with their perceptions of other students’ approval.

Belonging

Feeling connected to others, feeling appreciated, being viewed favorably, and being seen as competent by others are central to psychological well-being and important determinants of goal pursuits. Feeling connected to others and perceiving others as viewing the self with respect, appreciation, and approval also correspond to two of three fundamental psychological needs identified by self-determination theory (i.e., competence and relatedness needs; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Similarly, Sociometer Theory suggests that self-esteem reflects the extent to which an individual feels valued and socially accepted by relevant others (Leary, 2005; Leary & Baumeister, 2000, 2017; Leary et al., 1995). Belonging has been described as indispensable for human functioning and a fundamental human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Gere & MacDonald, 2010). Baumeister and Leary (1995) defined the need to belong as a need for interpersonal relationships that are positive and stable. Elsewhere, belonging has been described as a sense of fit or potential fit between oneself and a given setting or context, reflecting feeling included versus isolated and feeling valued versus not valued (Walton & Brady, 2017).

Belonging in the College Context

The transition to college typically involves a number of significant changes that are stressful for many students (e.g., changes in residence, finances, social networks, social activities, responsibilities, etc.; Ross et al., 1999). Increases in belongingness during the first year of college have been associated with increased psychological well-being (Pittman & Richmond, 2008). Students who find it challenging to establish new relationships are more likely to experience loneliness and increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (Moeller & Seehuus, 2019). Interventions that seek to increase feelings of belonging among individuals who report not feeling like they belong in a given context have demonstrated positive outcomes. For example, among first-year ethnic minority students, who may feel more disenfranchised in academic settings, a brief belongingness intervention resulted in better grades and health relative to a control condition (Walton & Cohen, 2007, 2011).

Similarly, a belongingness intervention provided to women in male-dominated majors was associated with increased grade point averages (GPAs), better integration, and more friendship with male classmates (Walton et al., 2015). These findings underscore the strong desire and motivation to fit in and feel a sense of belonging. They also reveal that the sense of belonging is not fixed in a given context but can change over time. As young adults establish a sense of belonging in college, they may consider factors likely to facilitate increased belongingness (e.g., “What things help new people fit in here? How do the people that appear to fit well in this context behave?”). For many students, alcohol consumption is an inherent part of the college experience and a vital determinant of belonging in this context (Angosta et al., 2019; Osberg et al., 2011).

Drinking to Belong

The transition to college is marked by a significant increase in alcohol consumption (Fromme et al., 2008). A considerable literature has linked alcohol consumption and perceptions of social approval in the college context (Borsari & Carey, 2003; LaBrie et al., 2010; Larimer et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2007; Real & Rimal, 2007). Drinking frequency has been previously associated with greater belongingness in college (Murphy et al., 2006).

Litt and colleagues reported that perceptions of best friends’ alcohol use were strongly associated with willingness to drink among students who were higher in need to belong but was not associated with willingness to drinking among students who were lower in need to belong (Litt et al., 2012). Students’ drinking behavior is also influenced by their perceptions that drinking is an important part of the college experience (Osberg et al., 2010). In addition, students correctly believe that most students drink at least occasionally (Neighbors et al., 2007), and that other students approve of consuming at least a few drinks on a given occasion (Krieger et al., 2016). In essence, students have the perception that drinking is a valued and shared experience among students who are favorably regarded, included, and accepted by their peers. There is, thus, some reason to expect that students who are generally higher (vs. lower) in belongingness will drink more than other students, and this will be especially true among those who perceive other students as more approving of drinking. However, research also indicates positive prospective associations between perceived norms and drinking among newer students (Lewis et al., 2015; Neighbors et al., 2006), which suggests that students may increase their drinking behavior to better integrate themselves within the social environment.

Further evidence suggests that students with lower implicit self-esteem appear to drink, at least partly, in hopes of acquiring social acceptance (DeHart et al., 2009) and consume more alcohol when drinking with friends when belongingness needs are activated (Hamilton & DeHart, 2017). Directly related to the present study, Hamilton and DeHart (2019) found that students higher in need to belong were more likely to drink in a manner consistent with their perceived injunctive norms on days when they experienced negative interpersonal interactions.

Additional support for the hypothesis that injunctive norms have greater influence during times when individuals feel lower in belongingness comes from work by Graupensperger et al. (2021). In this study, investigators examined associations between perceptions of group drinking norms and drinking among members of 35 college club sports teams at three times. Injunctive norms were positively associated with drinking at both the between- and within-person levels. Further, within-person associations between injunctive norms were moderated by within-person differences in social identity and in-degree network centrality. Thus, injunctive norms were more influential at times when individuals considered their group membership as a more important part of their self-image. Individuals’ drinking was also more strongly associated with drinking at times when fewer teammates reporting spending time with them (in-degree centrality). These results are consistent with the notion that when individual young adults feel a lower sense of belongingness within a valued group, they are more likely to drink in concordance with their perceptions of the group’s injunctive drinking norms.

Study Purpose and Overview

The present research aimed to clarify the influence of injunctive norms on drinking by evaluating belongingness as a moderator, focusing on prospective associations, and distinguishing within-person from between-person effects. Hypotheses were evaluated with data collected as part of a more extensive longitudinal study (Lindgren et al., 2016), which included a relatively large sample of undergraduate students who began the study in their first or second year of college. Participants were assessed every 3 months, covering a 2-year period. At the within-person level, we expected fluctuations in belongingness to moderate the prospective influence of injunctive norms on subsequent drinking. Based on the idea that individuals are most likely to adjust their behaviors to meet others’ expectations when they feel socially disconnected, we reasoned that injunctive norms would be most influential on drinking when feelings of belonging were lower relative to when they were higher.

We also expected belongingness to moderate the association between injunctive norms and drinking at the between-person level but in a different form than at the within-person level. Given previous cross-sectional findings that belongingness is associated with more drinking, especially when close others drink, at the between-person level, we expected injunctive norms to be positively associated with drinking, particularly among those who feel that they belong more.

Method

Participants

Participants included 383 (60% women) undergraduate students who reported consuming alcohol at any point during the 2 years in which they were assessed. In the larger study, 506 (57% women) undergraduates who were either first-year (54%) or second-year students were recruited to participate in a longitudinal study examining alcohol-related cognitive factors (please see Lindgren et al., 2016, for details about the larger study). Participants were assessed eight times at 3-month intervals. Of the 506 original participants, 383 (76%) reported consuming alcohol at one or more assessment points. For the purposes of this article, in which changes in drinking were the outcome of primary interest, individuals who reported no drinking at any time point were not included. Preliminary analyses indicated that abstainers did not differ from drinkers on average belongingness or injunctive norms. Race representation was 55.2% Caucasian, 29.2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 12.3% multiracial, and 5.7% other. Ethnicity representation was 8.1% Hispanic/Latino/a. Incentives for participation were $25 for completing each of the first three assessments, $30 for each of the subsequent four assessments, and $35 for the final assessment. As additional incentives, participants received $5 for completing all of the first four assessments and another $10 for completing all of the last four assessments.

Measures

Alcohol use was assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985; Dimeff et al., 1999). Participants are asked to report the average number of drinks consumed on each day of the week for a typical week over the past 3 months. Scores are computed as the sum of the number of drinks for each day of the typical week and thus reflect the typical number of drinks per week.

Injunctive norms were assessed with 15 items asking participants to indicate the extent to which they believe the typical student at their university finds drinking acceptable (Lewis et al., 2010). Response options ranged from 1 = unacceptable to 7 = acceptable. Sample items include drinking alcohol every weekend, drinking to have fun, drinking to get drunk, drinking to meet people, and drinking alone. Cronbach’s αs ranged from .87 to .91 across assessment points.

Belongingness was assessed with 17 items where participants are asked to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with their experience at their university (Walton & Cohen, 2007). Sample items include people at (school name) accept me; I feel like an outsider at (school name)-reverse coded; I think in the same way as do people who do well at (school name); I feel alienated from the (school name)-reverse coded; I know what kind of people the (school name) professors are; I fit in well at (school name). Participants indicated their level of agreement with each statement on a 7-point scale with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Belongingness scores represent the mean of the 17 items. Cronbach’s αs ranged from .92 to .94 across assessment points.

Procedure

First- and second-year undergraduate students were recruited via email addresses provided by the university registrar’s office. Only those who were full-time students and between the ages of 18 and 20 years old at the time of the initial assessment were included. Recruitment emails invited students to participate in an online-only longitudinal study consisting of eight assessments. These assessments took place every 3 months over 2 academic years on computers of the participants’ choosing. Specifically, assessments took place as follows: T1 Fall (October); T2 Winter (January); T3 Spring (April); T4 Summer (July); T5 Fall (October); T6 Winter (January); T7 Spring (April); T8 Summer (July). The university’s Institutional Review Board provided approval for all procedures. Additional details regarding other measures, retention rates, and incentives have been previously reported (Lindgren et al., 2016).

Analysis and Results

Distribution

The quantity of alcohol consumed in a typical week over the past 3 months was the primary outcome. Scores on this variable had a lower bound of zero, were positively skewed, and consisted of integers (i.e., counts-number of drinks). A comparison of fit indicators suggested a negative binomial model (Log-likelihood = −4,500.02; Akaike information critenon [AIC] = 9,028.04; Bayesian information critenon [BIC] = 9,105.11) provided superior fit relative to a Poisson model (Log-likelihood = −4,767.54; AIC = 9,561.07; BIC = 9,632.64) or a linear model (Log-likelihood = −5,504.94; AIC = 11,035.87; BIC = 11,107.43). Thus, multilevel negative binomial regression was used to model effects (Atkins et al., 2013; Cameron & Trivedi, 2013; Hilbe, 2011).

Descriptives

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) are presented in Table 1. ICCs for injunctive norms and belongingness were calculated as the ratio of between-person variance (random intercept) to the total variance [between-person variance + within-person variance (i.e., within residuals)] from mixed intercept-only models. The ICC for drinks per week was calculated using procedures described by Leckie and colleagues for multilevel negative binomial models (Leckie et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations, and Intraclass Correlation Coefficients

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1. Drinks per week | — | 0.192*** | 0.207*** | −0.048 | 0.144** |

| 2. Belongingness | 0.035 | — | 0.066 | −0.003 | −0.133** |

| 3. Injunctive norms | 0.065** | 0.052* | — | 0.041 | 0.089 |

| 4. Sex (female) | — | 0.103* | |||

| 5. School year (second year) | — | ||||

| M | 5.80 | 5.11 | 4.59 | 0.60 | .52 |

| SD | 7.50 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.49 | .50 |

| Between-person variance (ICC) | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Within-person SD | 4.18 | 0.13 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Note. Between-person correlations are above the diagonal. Within-person correlations are below the diagonal. School year was coded 0 = first-year; 1 = second-year at time of recruitment. Sex was coded 0 = men; 1 = women; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient. The Daily Drinking Questionnaire assessed drinks per week. Injunctive norms were assessed by the scale created by Lewis et al. (2010). Belongingness was assessed using items from Walton and Cohen (2007).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Lagging

In order to test the effects of injunctive norms and belongingness on subsequent drinking, both predictor variables were lagged such that drinking at time t + 1 was examined as a function of injunctive norms and belongingness at t. Drinking at the previous time point was person-mean centered and included as a covariate. Thus, each participant contributed up to seven observations for the eight assessment periods (t2 drinking = t1 norms, t1 belongingness, and t1 drinking; t3 drinking = t2 norms, t2 belongingness, and t2 drinking; . . . t8 drinking = t7 norms, t7 belongingness, and t7 drinking).

Centering

Given that our hypotheses were distinctly related to within-person effects versus between-person effects, data were structured to disaggregate within-person (Level 1) and between-person (Level 2) variance attributed to the three effects of interest: injunctive norms, belongingness, and the interaction between injunctive norms and belongingness. At Level 1, scores for injunctive norms and belongingness person-mean centered, such that each person’s mean on the relevant predictor was subtracted from each of the person’s original scores on the predictor . Thus, within-person scores for injunctive norms and belongingness represent how much higher or lower a person is at a given time point relative to their average score on the relevant variable. The Level 1 product term (Injunctive norms × Belongingness) was constructed from the person-mean centered scores of injunctive norms and belongingness. At Level 2, scores for injunctive norms and belongingness were the grandmean-centered person-means for each predictor. Thus, each person had a single Level 2 score reflecting his or her average score over all assessments, from which the sample mean of the relevant variable was subjected. The scores on the Level 2 predictors of injunctive norms and belongingness represent how much higher or lower a person’s average score was from the grand mean. The Level 2 product term (Injunctive norms × Belongingness) was constructed from the grand-mean-centered Level 2 scores of injunctive norms and belongingness. These centering approaches partition the variance in the predictors into uncorrelated factors reflecting within-and between-person variation corresponding to our hypotheses (Enders & Tofighi, 2007; Hoffman, 2015).

Time was centered at the middle assessment point (1 year) of predictors. Drinking at time t was included as a covariate and was person-mean centered. Between-person covariates included year in school at the first assessment (dummy coded: Year 1 = 0, Year 2 = 1), sex (dummy coded: men = 0, women = 1), and were both grand-mean-centered.

Parameter Estimates

Table 2 provides the results for specific parameter estimates. Estimates in negative binomial regression are log-linked such that the regression estimates correspond to the amount of expected change in the outcome on the natural log scale for each unit change in the predictor. When exponentiated, estimates represent incident rate ratios (IRRs), which indicate the expected proportion of change in the outcome for each unit change in the predictor. For example, between-person results revealed a significant effect of school-year, with an IRR of 1.52, indicating that participants who began the study as second-year students consumed 52% more drinks per week than students who began the study as first-year students.

Table 2.

Multilevel Negative Binomial Results for Drinks Per Week at Time t + 1

| Level | Predictor | b | SE b | Z | p | IRR | IRR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Intercept | 1.117 | 0.070 | 15.89 | <.001 | 3.054 | [2.661–3.505] | |

| Between-person | School year | −0.126 | 0.141 | −0.89 | .372 | 0.882 | [0.669–1.162] |

| Sex | 0.408 | 0.138 | 2.96 | .003 | 1.505 | [1.148–1.973] | |

| IN | 0.306 | 0.069 | 4.41 | <.001 | 1.358 | [1.185–1.555] | |

| BEL | 0.295 | 0.068 | 4.32 | <.001 | 1.343 | [1.175–1.536] | |

| IN × BEL | 0.095 | 0.066 | 1.45 | .146 | 1.100 | [0.967–1.251] | |

| Within-person | Drinks per week at time t | −0.007 | 0.005 | −1.61 | .108 | 0.993 | [0.984–1.002] |

| Time | 0.059 | 0.016 | 3.65 | <.001 | 1.061 | [1.028–1.096] | |

| IN | −0.007 | 0.020 | −0.36 | .720 | 0.993 | [0.954–1.033] | |

| BEL | 0.049 | 0.023 | 2.13 | .033 | 1.050 | [1.004–1.098] | |

| IN × BEL | −0.058 | 0.021 | −2.77 | .006 | 0.944 | [0.906–0.983] | |

| Dispersion | ln(α) | −1.315 | 0.101 | −13.07 | <.001 | ||

| Random effects | Var(Time) | 0.036 | 0.007 | 5.01 | <.001 | ||

| Var(Intercept) | 2.101 | 0.244 | 8.61 | <.001 | |||

| Cov(Time, Intercept) | −0.178 | 0.037 | −4.87 | <.001 | |||

Note. School year was coded 0 = first-year; 1 = second-year at time of recruitment. Sex was coded 0 = men; 1 = women; IRR = incident rate ratio; IN = injunctive norm; BEL = belongingness.

Consistent with hypotheses, participants who tended to perceive typical students at their university as more approving of drinking consumed 52% more drinks per week than participants who viewed typical students at their university as less approving of drinking. Also consistent with hypotheses, participants who reported higher average levels of belongingness at their university drank more than participants who reported lower average levels of belongingness. The nonsignificant effect for the product of Injunctive norms × Belongingness indicates the absence of an interaction when considering drinks per week in log units. Interpretation of the interaction in natural units (i.e., drinks per week) is described in detail below.

Within-person results for the model were consistent with expectations, revealing a main effect of injunctive norms such that when perceived injunctive norms were higher, participants consumed more drinks per week. There was no main effect of belongingness, but the Injunctive norms × Belongingness product term was significant, indicating that when participant’s sense of belongingness was below their average belongingness, perceiving others as more approving of drinking was prospectively associated with consuming more log drinks per week.

Interpretation of Interactions in Natural Units

Because negative binomial regression is a log-linear model, traditional methods for interpreting interactions (Cohen et al., 2013) are only appropriate with respect to the log-transformed outcome. In linear models, the coefficient of the product term is sufficient to characterize an interaction. Thus, for each unit decrease in belongingness at time t, the association between injunctive norms at time t and ln(drinks per week at time t + 1), controlling for drinks per week at time t, increased by .27. Evaluation of the interaction on the natural scale of drinks per week requires alternative approaches. This is because, in nonlinear models, the effect of a given variable on the outcome does not change at a constant rate as a function of another variable but depend on the values of all variables in the model (for a tutorial see McCabe et al., 2021). Examination of marginal effects of a predictor at differing values of another predictor is an appropriate method for evaluating an interaction in a nonlinear (log-linked) model on the natural scale of the outcome (McCabe et al., 2021; Mize, 2019).

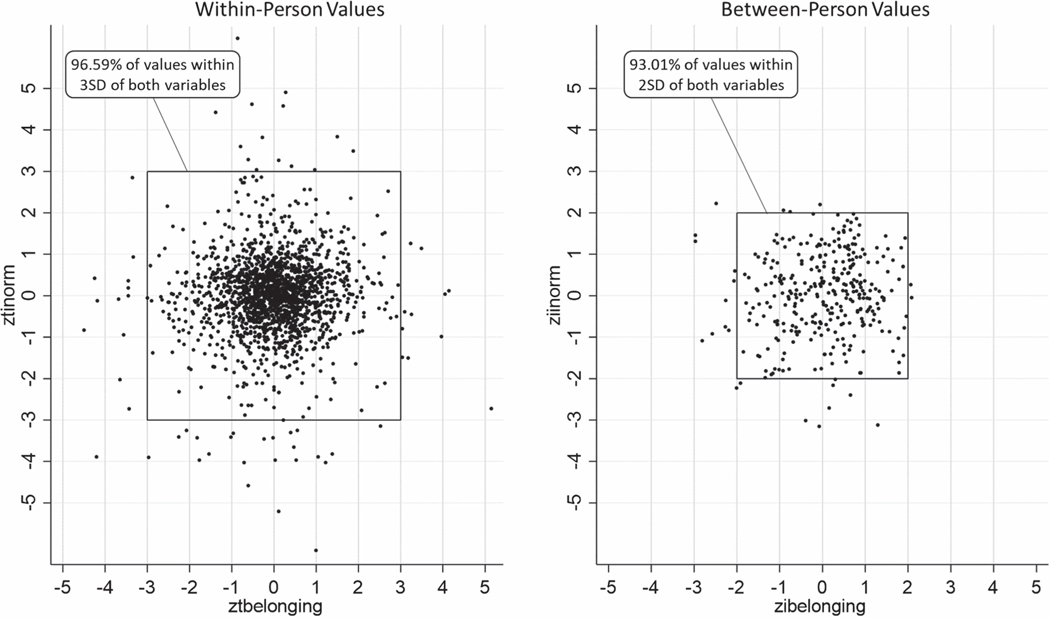

Marginal tests of within-person variations in injunctive norms were evaluated at 1, 2, and 3 SDs above and below the within-person mean of belongingness, averaged over the values of all other variables in the model (average marginal effects). Marginal tests of between-person effects of injunctive norms were evaluated at 0, 1, and 2 SDs above and below the between-person mean of belongingness, averaged over all other variables. The units selected were chosen for ease of interpretation. For example, a score of −1 for within-person belongingness represented one unit below the person’s average belongingness score. Similarly, a score of 2 for within-person injunctive norms represented two units below the person’s average injunctive norms score. The range of values selected was chosen to encompass the full distribution of the variables (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Within-Person Injunctive Norms by Within-Person Belongingness, and Between-Person Injunctive Norms by Between-Person Belongingness

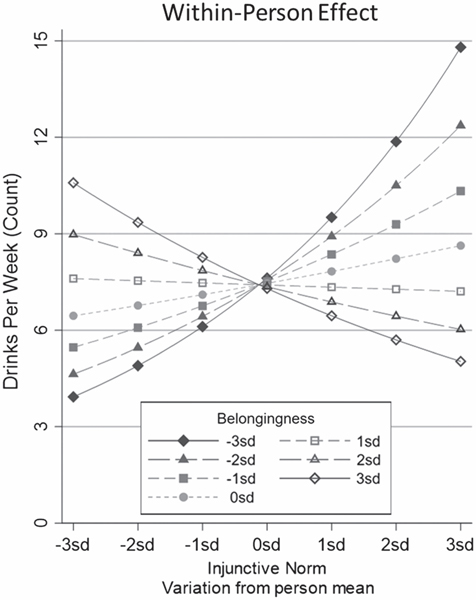

The pattern of the interaction and marginal values for the within-person interaction are presented in Figure 2. Tests of marginal effects and differences between marginal effects are presented in Table 3. Results indicated that when students’ belongingness was at or below their typical sense of belongingness, perceived injunctive norms were prospectively associated with more drinking. When students’ belongingness was above their typical sense of belongingness, perceived injunctive norms were not significantly associated with subsequent drinking. Tests of differences in the average marginal effects of injunctive norms were significant for all contrasts of evaluated values of belongingness.

Figure 2.

Within-Person Interaction of Belongingness and Injunctive Norms Subsequent Drinking

Table 3.

Tests of Average Marginal Effects (AME) to Test the Interaction of Within-Person Belongingness (WP BEL) × Within-Person Injunctive Norm (IN) on Subsequent Drinking

| Estimated effect | AME | SE | z | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| WP belongingness = −3 SD | 1.717 | 0.572 | 3.00 | .003 | [0.595–2.839] |

| WP belongingness = −2 SD | 1.250 | 0.390 | 3.20 | .001 | [0.485–2.016] |

| WP belongingness = −1 SD | 0.800 | 0.244 | 3.28 | .001 | [0.322–1.278] |

| WP belongingness = 0 SD | 0.363 | 0.174 | 2.09 | .037 | [0.022–0.703] |

| WP belongingness = 1 SD | −0.066 | 0.234 | −0.28 | .778 | [−0.526 to 0.393] |

| WP belongingness = 2 SD | −0.490 | 0.362 | −1.35 | .176 | [−1.199 to 0.219] |

| WP belongingness = 3 SD | −0.912 | 0.512 | −1.78 | .075 | [−1.915 to 0.091] |

| Contrast | |||||

| −2 SD vs. −3 SD | −0.466 | 0.196 | −2.38 | .018 | [−0.851 to −0.082] |

| −1 SD vs. −3 SD | −0.916 | 0.375 | −2.45 | .014 | [−1.650 to −0.182] |

| 0 SD vs. −3 SD | −1.354 | 0.540 | −2.51 | .012 | [−2.412 to −0.296] |

| 1 SD vs. −3 SD | −1.783 | 0.698 | −2.56 | .011 | [−3.150 to −0.416] |

| 2 SD vs. −3 SD | −2.206 | 0.853 | −2.59 | .010 | [−3.877 to −0.535] |

| 3 SD vs. −3 SD | −2.628 | 1.010 | −2.60 | .009 | [−4.609 to −0.648] |

| −1 SD vs. −2 SD | −0.450 | 0.179 | −2.52 | .012 | [−0.800 to −0.100] |

| 0 SD vs. −2 SD | −0.888 | 0.345 | −2.58 | .010 | [−1.563 to −0.212] |

| 1 SD vs. −2 SD | −1.316 | 0.503 | −2.61 | .009 | [−2.303 to −0.330] |

| 2 SD vs. −2 SD | −1.740 | 0.660 | −2.64 | .008 | [−3.034 to −0.446] |

| 3 SD vs. −2 SD | −2.162 | 0.820 | −2.64 | .008 | [−3.770 to −0.554] |

| 0 SD vs. −1 SD | −0.438 | 0.167 | −2.63 | .009 | [−0.764 to −0.111] |

| 1 SD vs. −1 SD | −0.866 | 0.326 | −2.66 | .008 | [−1.506 to −0.227] |

| 2 SD vs. −1 SD | −1.290 | 0.484 | −2.66 | .008 | [−2.240 to −0.341] |

| 3 SD vs. −1 SD | −1.712 | 0.646 | −2.65 | .008 | [−2.979 to −0.445] |

| 1 SD vs. 0 SD | −0.429 | 0.160 | −2.68 | .007 | [−0.743 to −0.115] |

| 2 SD vs. 0 SD | −0.852 | 0.319 | −2.67 | .008 | [−1.478 to −0.227] |

| 3 SD vs. 0 SD | −1.274 | 0.483 | −2.64 | .008 | [−2.220 to −0.329] |

| 2 SD vs. 1 SD | −0.424 | 0.160 | −2.65 | .008 | [−0.736 to −0.111] |

| 3 SD vs. 1 SD | −0.846 | 0.324 | −2.61 | .009 | [−1.480 to −0.211] |

| 3 SD vs. 2 SD | −0.422 | 0.165 | −2.56 | .010 | [−0.745 to −0.099] |

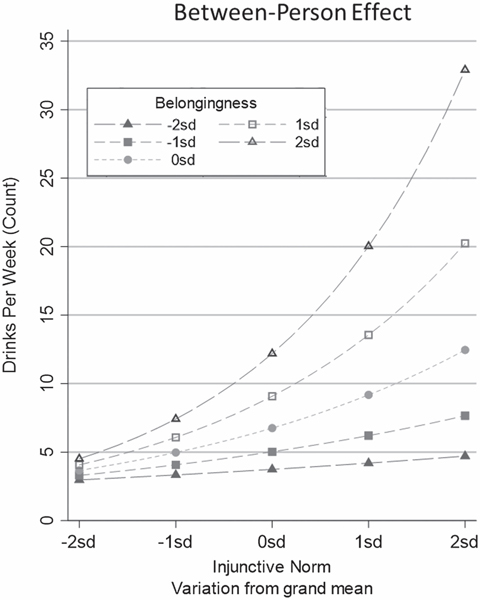

The pattern of the interaction and marginal values for the between-person interaction are presented in Figure 3. Tests of marginal effects and differences between marginal effects are shown in Table 4. Results indicated that students with higher perceived injunctive norms drank more than students with lower perceived injunctive norms and that this tendency was stronger among students with higher levels of belongingness than students with lower levels of belongingness. Between-person average marginal effects of injunctive norms at −2 SD, −1 SD,0 SD, and +1 SD of belongingness were all significantly different from each other. The average marginal effect of between-person injunctive norms at +2 SD of belongingness did not differ from any of the other tested values of belongingness. Examination of tests of differences in Table 4 reveals relatively large standard errors of all differences involving the average marginal effect of injunctive norms at +2 SD of belongingness.

Figure 3.

Between-Person Interaction of Belongingness and Injunctive Norms Subsequent Drinking

Table 4.

Tests of Average Marginal Effects (AME) to Test the Interaction of Between-Person Belongingness (BP BEL) × Betwen-Person Injunctive Norm (IN) on Subsequent Drinking

| Estimated effect | b | SE | z | p value | LL | UL | comp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| BP belongingness = −2 SD | 0.434 | 0.556 | 0.78 | .434 | −0.655 | 1.523 | |

| BP belongingness = −1 SD | 1.085 | 0.512 | 2.12 | .034 | 0.081 | 2.089 | A |

| BP belongingness = 0 SD | 2.171 | 0.569 | 3.82 | .000 | 1.056 | 3.286 | B |

| BP belongingness = 1 SD | 3.953 | 1.197 | 3.30 | .001 | 1.606 | 6.299 | C |

| BP belongingness = 2 SD | 6.844 | 2.807 | 2.44 | .015 | 1.343 | 12.345 | ABC |

| Contrast | |||||||

| −1 SD vs. −2 SD | 0.650 | 0.198 | 3.29 | .001 | 0.263 | 1.038 | |

| 0 SD vs. −2 SD | 1.736 | 0.607 | 2.86 | .004 | 0.547 | 2.926 | |

| 1 SD vs. −2 SD | 3.518 | 1.453 | 2.42 | .015 | 0.671 | 6.366 | |

| 2 SD vs. −2 SD | 6.410 | 3.145 | 2.04 | .042 | 0.246 | 12.573 | |

| 0 SD vs. −1 SD | 1.086 | 0.416 | 2.61 | .009 | 0.271 | 1.901 | |

| 1 SD vs. −1 SD | 2.868 | 1.272 | 2.26 | .024 | 0.375 | 5.360 | |

| 2 SD vs. −1 SD | 5.759 | 2.973 | 1.94 | .053 | −0.068 | 11.587 | |

| 1 SD vs. 0 SD | 1.782 | 0.861 | 2.07 | .038 | 0.095 | 3.469 | |

| 2 SD vs. 0 SD | 4.673 | 2.569 | 1.82 | .069 | −0.361 | 9.708 | |

| 2 SD vs. 1 SD | 2.891 | 1.712 | 1.69 | .091 | −0.463 | 6.246 | |

Note. The comp (comparison) column provides a summary of contrasts such that effects sharing a letter are not significantly different from each other.

Discussion

The present research offers new insights into associations between perceived injunctive norms and drinking among young adults. This study is one of only a few studies to examine prospective associations between injunctive norms and drinking and to distinguish within-person from between-person effects. Importantly, this study’s findings extend previous investigations of injunctive drinking norms, integrating theoretical foundations of social influence by incorporating the construct of belongingness.

Early studies of social influence identified two types of influence: informational social influence occurs when individuals conform because they believe others have accurate information, whereas normative social influence occurs when individuals conform because they want to be accepted by others (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955). Conforming to descriptive drinking norms need not reflect a desire to be accepted or avoid rejection because they can be interpreted as accurate indicators of levels of contextually appropriate behavior. In contrast, injunctive norms represent inherently evaluative endorsements and prescriptions for specific actions and expressions. Peers are likely to maintain or increase the distance from individuals who either express themselves or act in ways that are viewed unfavorably by the group or who fail to express themselves or act in ways that are viewed favorably by the group. The present study results are consistent with the theoretical bases underlying the hypotheses (i.e., self-determination theory, sociometer theory, social identity theory) and specifically with the proposition that perceived injunctive drinking norms are most influential when students are lower in belongingness relative to their typical level of belongingness. Future work might directly examine whether individuals who wish to restore or increase a positive sense of belongingness may respond by conforming to salient injunctive norms within the relevant social domain.

An alternative conceptualization of findings for further examination is the possibility that fluctuations in perceived injunctive norms were prospectively associated with corresponding changes in drinking except when participants reported higher than average belongingness. This may suggest that when individuals feel particularly secure in their belongingness, they no longer feel the need to gain social approval and are less concerned about the prospect of alienation or rejection.

The present research also highlights the importance of distinguishing between-person from within-person associations among belongingness, injunctive norms, and drinking. In particular, cross-sectional studies and examination of between-person associations between belongingness and drinking might lead to conclusions that belongingness is a risk factor for drinking. However, such conclusions may be short-sighted and miss underlying within-person processes that may prescribe specific strategies for reducing risks by addressing dips in belongingness. For example, students who are lower in belongingness may have fewer opportunities to attend social gatherings with other students, where alcohol consumption is common. Students who drink more may actively seek out more activities involving interactions with other students. Individuals’ differences in personality or sociodemographic factors may account for higher or lower belongingness and level of alcohol consumption.

While the present findings replicate previous positive between-person associations between belongingness and drinking, they also provide relatively strong evidence against the notion that belongingness is a risk factor for heavy drinking. Indeed, the within-person results indicated no overall association between belongingness and subsequent drinking. If anything, low belongingness may increase the risk of drinking, but only when accompanied by perceptions that other students approve of drinking.

Clinical Implications

Results suggest practical clinical implications. First, existing interventions designed to increase belongingness have been successful in improving academic outcomes among students from groups at risk for low belongingness (Walton & Cohen, 2007, 2011; Walton et al., 2015). Adapted belongingness interventions might provide a range of practical strategies for increasing connections with others and, at the same time, reducing the likelihood of increasing drinking as a strategy for gaining acceptance and alleviating feelings of disconnection or alienation. Alternatively, existing alcohol intervention administrators might consider asking participants about their current sense of belonging in the college domain relative to their typical sense of belonging. Students who report feeling more less connected than usual might benefit from personalized norms feedback based on injunctive norms, either alone or in the context of an existing intervention program.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present research includes a single study at one university. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the robustness of the findings. While college students are a significant population for examining drinking among young adults, it is not clear that similar results would be evident in noncollege samples or of young adults aged 21 and over. It seems unlikely that belongingness and injunctive norms would play the same role in young adults who are not in an environment where peers are plentiful, and drinking is relatively prevalent. Future research might consider examining whether similar effects are evident in military samples. The present study also included only one measure of belongingness. It would be useful to see whether other measures of belongingness or constructs similar to belongingness (e.g., loneliness, need to belong, or social connectedness) might produce similar results. The present study was unfortunately not equipped to test belongingness as a unique moderator of prospective effects of injunctive norms on drinking relative to descriptive norms. Descriptive norms were assessed in the beginning waves of the study but were dropped after Wave 3 to reduce survey length. Additional research integrating descriptive norms might help distinguish the extent to which descriptive drinking norms function based on informational versus normative social influence and would further clarify the role of belongingness in the influence of both types of norms. It would also be useful to consider ways to utilize injunctive norms from more proximal groups with whom students personally identify. This may require some creativity, given that different people identify with different groups.

Conclusions

The present study’s results enhance our understanding of when and where injunctive norms appear more or less related to drinking. Results also clarify the importance of a sense of belonging at one’s university (including with the larger institution and education components as well as with peers) in relation to drinking. In particular, injunctive norms appear to be particularly predictive of subsequent drinking when individuals’ sense of belonging is below average. Recognition that students tend to be most affected by perceptions of other students’ approval when they feel less connected may facilitate fruitful new avenues in intervention approaches that incorporate both injunctive norms and belongingness.

Public Health Significance Statement.

This study shows that fluctuations in one’s sense of belongingness play an important role in determining when college students are most susceptible to peer influences on drinking. Increasing drinking in response to perceiving others as more approving of drinking appears to occur primarily when one’s sense of belongingness is lower than normal. These results may contribute to empirically based approaches for personalizing the content of interventions.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants (R01AA021763, PI: Kristen P. Lindgren). Preparation of this manuscript was also supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants (R01AA014576 and R21AA023917, PI: Clayton Neighbors and R01AA024732, PI: Kristen P. Lindgren).

Clayton Neighbors played a lead role in conceptualization. Mary M. Tomkins played supporting role in conceptualization. Lorra Garey played supporting role in conceptualization and methodology. Melissa Gasser played a lead role in methodology. Nisha Quraishi played supporting role in writing of review and editing. Kristen P. Lindgren played a lead role in funding acquisition and supporting role in conceptualization.

References

- Angosta J, Steers MN, Steers K, Lembo Riggs J, & Neighbors C. (2019). Who cares if college and drinking are synonymous? Identification with typical students moderates the relationship between college life alcohol salience and drinking outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 98, Article 106046. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C. (2013). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 166–177. 10.1037/a0029508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, & Larimer M. (1991). Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 52(6), 580–586. 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(3), 331–341. 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, & Trivedi PK (2013). Regression analysis of count data (Vol. 53). Cambridge university press. 10.1017/CBO9781139013567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, Pledger M, & Pratap S. (2002). Trajectories of drinking from 18 to 26 years: Identification and prediction. Addiction, 97(11), 1427–1437. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203774441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, & Spelman PJ (2013). Associations of descriptive and reflective injunctive norms with risky college drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 1175–1181. 10.1037/a0032828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart T, Tennen H, Armeli S, Todd M, & Mohr C. (2009). A diary study of implicit self-esteem, interpersonal interactions and alcohol consumption in college students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 720–730. 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, & Gerard HB (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgement. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–636. 10.1037/h0046408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGuiseppi GT, Davis JP, Meisel MK, Clark MA, Roberson ML, Ott MQ, & Barnett NP (2020). The influence of peer and parental norms on first-generation college students’ binge drinking trajectories. Addictive Behaviors, 103, Article 106227. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff L, Baer J, Kivlahan D, & Marlatt G. (1999). Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, & Kruse MI (2008). Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1497–1504. 10.1037/a0012614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gere J, & MacDonald G. (2010). An update of the empirical case for the need to belong. Journal of Individual Psychology, 66(1), 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Graupensperger S, Jaffe AE, Hultgren BA, Rhew IC, Lee CM, & Larimer ME (2020). The dynamic nature of injunctive drinking norms and within-person associations with college student alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. 10.1037/adb0000647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graupensperger S, Turrisi R, Jones D, & Evans MB (2021). Dynamic characteristics of groups and individuals that amplify adherence to perceived drinking norms in college club sport teams: A longitudinal multilevel investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(3), 351–365. 10.1037/adb0000654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, & Kerr WC (2003). Tracking alcohol consumption over time. Alcohol Research & Health, 27(1), 30–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler KJ, Pearson MR, Venner KL, & Greenfield BL (2017). Descriptive drinking norms in Native American and non-Hispanic White college students. Addictive Behaviors, 72, 45–50. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HR, & DeHart T. (2017). Drinking to belong: The effect of a friendship threat and self-esteem on college student drinking. Self and Identity, 16(1), 1–15. 10.1080/15298868.2016.1210539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HR, & DeHart T. (2019). Needs and norms: Testing the effects of negative interpersonal interactions, the need to belong, and perceived norms on alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 340–348. 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM (2011). Negative binomial regression (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511973420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. (2015). Longitudinal analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuation and change. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. 10.4324/9781315744094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, & Reid SA (2006). Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory, 16(1), 7–30. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00003.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, & Miech R. (2013). Age, period, and cohort effects in heavy episodic drinking in the US from 1985 to 2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(1–2), 140–148. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger H, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, LaBrie JW, Foster DW, & Larimer ME (2016). Injunctive norms and alcohol consumption: A revised conceptualization. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(5), 1083–1092. 10.1111/acer.13037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, & Larimer ME (2010). Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 343–349. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME., Turner AP., Mallett KA., & Geisner IM. (2004). Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 203–212. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 75–111. 10.1080/10463280540000007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, & Baumeister RF (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62) Elsevier. 10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, & Baumeister RF (2017). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. In Interpersonal Development (pp. 57–89). Routledge. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tambor ES, Terdal SK, & Downs DL (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 518–530. 10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leckie G, Browne WJ, Goldstein H, Merlo J, & Austin PC (2020). Partitioning variation in multilevel models for count data. Psychological Methods, 25(6), 787–801. 10.1037/met0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Litt DM, & Neighbors C. (2015). The chicken or the egg: Examining temporal precedence among attitudes, injunctive norms, and college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(4), 594–601. 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Geisner IM, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, & Atkins DC (2010). Examining the associations among severity of injunctive drinking norms, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related negative consequences: The moderating roles of alcohol consumption and identity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 177–189. 10.1037/a0018302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Teachman BA, Baldwin SA, Norris J, Kaysen D, Gasser ML, & Wiers RW (2016). Implicit alcohol associations, especially drinking identity, predict drinking over time. Health Psychology, 35(8), 908–918. 10.1037/hea0000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt DM, Stock ML, & Lewis MA (2012). Drinking to fit in: Examining the need to belong as a moderator of perceptions of best friends’ alcohol use and related risk cognitions among college students. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 313–321. 10.1080/01973533.2012.693357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Wray-Lake L, & Schulenberg JE (2013). Developmental risk taking and the natural history of alcohol and drug use among youth. In Miller PM, Ball SA, Bates ME, Blume AW, Kampman KM, Kavanagh DJ, & De Witte P(Eds.), Comprehensive addictive behaviors and disorders: Principles of addiction (Vol. 1, pp. 535–544). Elsevier Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-398336-7.00056-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Faden VB, Zucker RA, & Spear LP (2009). A developmental perspective on underage alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health, 32(1), 3–15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860500/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe CJ, Halvorson MA, King KM, Cao X, & Kim DS (2021). Interpreting interaction effects in generalized linear models of nonlinear probabilities and counts. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 28(6), 1–27. 10.1080/00273171.2020.1868966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, & Carey KB (2016). Drinking over the lifespan: Focus on college ages. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 103–114. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4872605/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize TD (2019). Best practices for estimating, interpreting, and presenting nonlinear interaction effects. Sociological Science, 6, 81–117. 10.15195/v6.a4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller RW, & Seehuus M. (2019). Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 73, 1–13. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Gould R, Reuben DB, Greendale GA, Carter MK, Zhou K, & Karlamangla A. (2005). Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 458–465. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Hoyme CK, Colby SM, & Borsari B. (2006). Alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and quality of life among college students. Journal of College Student Development, 47(1), 110–121. 10.1353/csd.2006.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, & Neil TA (2006). Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(2), 290–299. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 556–565. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, & Fossos N. (2008). The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 576–581. 10.1037/a0013043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Atkins L, Buchholz L, Shirshova V, Swiantek A, Whitley J, Hartman S, & Oquendo N. (2010). Development and validation of the college life alcohol salience scale: A measure of beliefs about the role of alcohol in college life. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(1), 1–12. 10.1037/a0018197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Insana M, Eggert M, & Billingsley K. (2011). Incremental validity of college alcohol beliefs in the prediction of freshman drinking and its consequences: A prospective study. Addictive Behaviors, 36(4), 333–340. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, & Richmond A. (2008). University belonging, friendship quality, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. Journal of Experimental Education, 76(4), 343–361. 10.3200/JEXE.76.4.343-362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, & Miller DT (1993). Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 243–256. 10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real K, & Rimal RN (2007). Friends talk to friends about drinking: Exploring the role of peer communication in the theory of normative social behavior. Health Communication, 22(2), 169–180. 10.1080/10410230701454254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SE, Niebling BC, & Heckert TM (1999). Sources of stress among college students. College Student Journal, 61(5), 841–846. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. 10.1521/978.14625/28806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Quinn PD, Wetherill RR, & Fromme K. (2010). Perceived norms for drinking in the transition from high school to college and beyond. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(6), 895–903. 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Brady ST (2017). The many questions of belonging. In Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, & Yeager DS(Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 272–293). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Cohen GL (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82–96. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Cohen GL (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. 10.1126/science.1198364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Logel C, Peach JM, Spencer SJ, & Zanna MP (2015). Two brief interventions to mitigate a “chilly climate” transform women’s experience, relationships, and achievement in engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 468–485. 10.1037/a0037461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, & Papadaratsakis V. (2005). Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their non-college age peers. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 281–306. 10.1177/002204260503500204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]