Abstract

Intracortical microstimulation of primary sensory regions of the brain offers a compelling platform for the development of sensory prostheses. However, fundamental questions remain regarding the optimal stimulation parameters. The purpose of this paper is to summarize a series of experiments which were designed to answer the following three questions. 1) What is the best electrode implantation depth? 2) What is the optimal stimulation waveform? 3) What is the maximal useful stimulus pulse rate? The present results suggest the following answers: 1) cortical layers V&IV, 2) biphasic, charge balanced, symmetric, cathode leading pulses with of duration of ~ 100 microseconds per phase, and 3) 80 pulses-per-second.

I. Introduction

Neuroprosthetics successes, such as cochlear implants [1] and deep brain stimulation implants [2], indicate future potential neuroprosthetic treatments in health care, such as pain relief, visual, auditory, or somatosensory prostheses, or sensory-motor rehabilitation. Many of these neuroprostheses require implantation into the brain and several penetrating multi-channel microelectrode technologies are appropriate for this application [3-9]. What is not known are the optimal electrical stimulation parameters, particularly with consideration to the tissue response to device insertion and the chronic application of the electrical stimulation.

Longitudinal stimulation efficacy is of critical importance to microelectrode-based stimulation neuroprostheses. While chronic electrical macrostimulation is historically reliable, recent reports indicate that intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) is not [10]. Putatively, the reactive tissue response is implicated in the unreliability of the microelectrode stimulation. Of considerable note, device-capture histology suggests that the reactive tissue response is not constant with the depth of electrode penetration; rather, it is significantly higher near the cortical surface [11]. The electrical stimulation efficacy with respect to depth of the stimulated channel deserves evaluation.

Most neuroprosthetic systems employ the charge-balanced, biphasic waveforms that were suggested by Lilly el al. to be safe and efficacious [12]. However, computational studies suggest that alternative waveforms may result in more efficient neural activation by taking advantage of the non-linear aspects of the neuronal ion channels [13, 14]. The applicability of using asymmetric waveforms for chronic neural prostheses is still unknown.

The informational bandwidth of an individual microelectrode site will be strongly influenced by the pulse rate of the applied stimulation. Higher stimulation rates can serve as a significantly better platform for modulation-based information. Neurons within the “zone of activation” of a given microelectrode will theoretically be entrained by the stimulation rate, up to a point that is ultimately limited by the refractory period. Several studies have investigated the ability of increasing pulse rate to provide more efficacious stimulation for cortical neuroprostheses [15, 16]. It is as-of-yet unknown how pulse rate affects stimulation-evoked behavior in the auditory cortex.

Here we provide results from three studies that seek to determine the optimal electrical stimulation parameters for an auditory cortical prosthesis. First, we investigated the role of cortical depth and time post-implant on the threshold for detection of electrical microstimulation. Second, we evaluated various charge balanced waveforms and their behavioral detectability. And finally, we conducted a study of the role of electrical stimulation pulse rate on the electrical microstimulation detectability. These findings help to elucidate parameters that will enable a reliable, high-fidelity, efficacious auditory cortical prosthesis. In addition, it is likely that many of these findings are translatable to other paradigms including visual or somatosensory prostheses.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Behavioral Paradigm & Electrical Stimulation

In brief, water deprived rats were trained using a conditioned avoidance task. The rats learned to stop licking a water spout in response to a 650 ms warning tone in order to avoid a 1.6 mA cutaneous shock delivered through the spout. Warning trials were randomly presented with a 20% probability among safe trials. For safe trials, no sound was played; however, the rat’s presence on the spout was monitored as to ensure the rat was licking in absence of a stimulus. This data was used to calculate a false alarm rate. If the false alarm rate it exceeded 20% for a given series, the series was removed from analysis and repeated. After the electrode implantation, electrical pulse trains of 650 ms were used as the warning. The conditions of the given experiment determined the parameters of the pulse train. The stimulation was delivered by an MS16 stimulus isolator with 4 serial NC48 batteries, enabling a +/− 96V compliance voltage (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL).

To estimate the rat’s threshold, an adaptive paradigm was used in which correct detections were followed by a lower amplitude warning stimulus and every miss was followed by a higher amplitude stimulus. The rat was allowed to make five or seven reversals. In this way the rat reached an amplitude for which he had approximately a 50% chance of detecting, which was estimated by averaging his final four reversal values and defined as his threshold. Rats learned the task in an average of 3 days, with 15 minutes being shortest and 20 days being the longest time to detection.

B. Surgery

Specifics of the implant procedures are described in other publications [17]. Briefly, before surgery, an areflexive state was achieved by anesthetic induction through an intraperitoneal injection of a combination of ketamine hydrochloride (80 mg/kg body wt) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). The depth of anesthesia was monitored and anesthesia was supplemented by ketamine hydrochloride (20 mg/kg body wt) if the animal withdrew a limb in response to a toe pinch or if spontaneous movement was noted.

The skull over the right primary auditory cortex of was drilled open using a burr. Vascular landmarks were used to identify the primary auditory cortex [18].

Sixteen channel, linear, single silicon microelectrode array with site areas of 703 or 1250 μm2 and site materials of iridium oxide (IrOx) or Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) spaced on 100 μm pitch (NeuroNexus Technologies, Ann Arbor, MI) were used. In the case of IrOx the electrode was activated 48 hours prior to surgery [19]. During surgery the electrode was lowered to the surface by hand using microforceps (Fine Science Tools Inc., Foster City, CA) and inserted with a radial penetration into the cortical mantle such that the recording sites were positioned spanning 0 – 1.5 millimeters from the cortical surface (microscopic visual inspection confirmed that the most superficial electrode site was at the surface of the cortex). A small wire was attached to an implanted titanium bone screw (size 2-56) for an electrical ground point.

Neural recordings were made during surgery (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL) to assess the neurophysiological responses to click stimuli and to ensure primary auditory cortex placement. Upon confirmation, the electrode array and silicon cable were encased in silicone elastomer. A final layer of dental acrylic was then applied to seal the craniotomy and anchor the implant in place.

C. Experimental Designs

Ten male Sprague-Dawley rats (450-550 g) were used in four experiments to study the effects of the following parameters on the detection threshold for ICMS 1) Electrode Site Depth, 2) Time Post Implant, 3) Waveform, and 4) Pulse Rate. Several rats were in multiple experiments, while a few participated in only one. Additionally electrode material and site depth of the experiments did vary between the rats used for a given experiment. These experimental units and conditions along with the number of threshold collected for the experiments are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE I.

Experiment Summary

| Experiment | Rats | Thresholds |

Electrode

Mtrl. {Rats} |

Site Depths

(μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | 6 | 277 | IrOx {3} & PeDOT {3} | 0-1500 |

| Stability | 7 | 1372 | IrOX {3} & PeDOT {4} | 0-1500 |

| Waveform | 3 | 250 | IrOx | 500, 1000, 1500 |

| Pulse Rate | 2 | 120 | IrOx | 800 |

Experiments 1), and 2) were designed as a longitudinal study aimed to answer two interwoven but distinct questions, 1) what role does site depth play in the behavioral detection of electrical stimulation and 2) what role does site depth play in the stability of detection thresholds. Electrode sites were randomized in terms of order presented to the rat and the detection threshold for each site was collected.

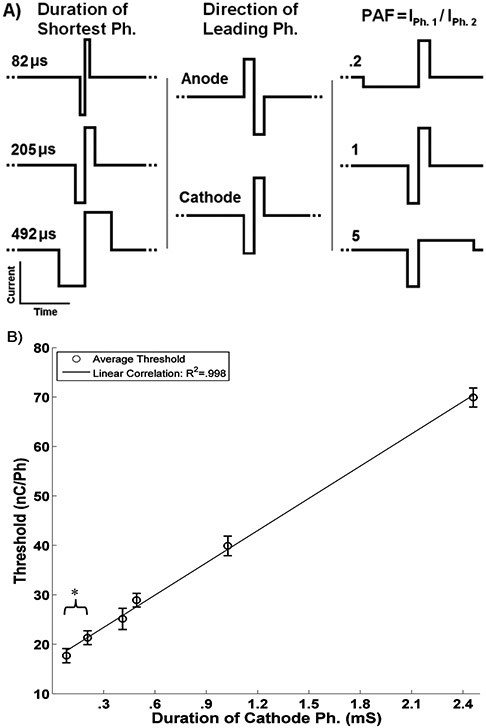

Experiment 3) tested the effect of phase direction (anode or cathode), phase duration (82, 205, 492 μs/Ph) and asymmetry, defined as the phase amplitude factor (PAF)

| (1) |

where I 1 and I 2 are the amplitude of the current for the first and second phase respectively, (PAF = .2, 1, 5) . All three factors and their levels are shown in Figure 2A. The experiment was done in a complete factorial design so there were a total of 18 factor combinations. Waveforms were randomized in terms of the order they were presented to the rat and every day the rats generated thresholds for at least 14 of the 18 waveforms. The experiment was repeated 15 times.

Figure 2. Waveform effects.

A) Factors and levels for experimental design. B) Effect of the cathode phase duration on threshold. Error bars represent 95% CI of the least squares estimate of the mean. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) between pulses of .082 and .205 ms/Ph.

Experiment 4) tested the effect of stimulus pulse rate on detection thresholds. Twelve pulse rates, logarithmically spaced from 16 to 338 pulses per second (PPS) were used. Pulse rates were randomized by the order presented to the rat and every day the rats generated thresholds for all 12 pulse rates, constituting a complete block design. The experiment was repeated a total of 5 times by two rats.

D. Statistical Analysis

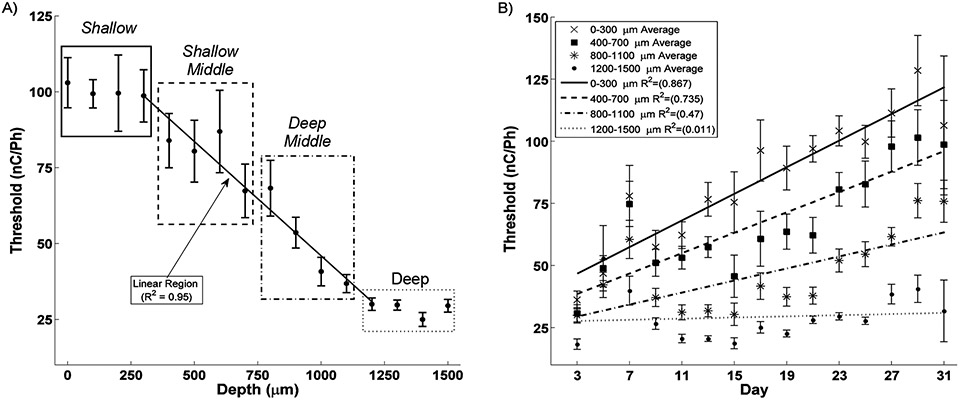

Experiment 1) was analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA). Threshold from six rats collected 22 to 25 days post-op were averaged by electrode sited depth and the standard error of the mean was collected. Linear regression of site depth vs. threshold was performed on sites 300 μm to 1200 μm below the surface.

Experiment 2) was analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA). Threshold from seven rats collected from 3-32 days post op. They were then binned by 48 hour intervals and in four regions by cortical depth (0-300 μm, 400-700 μm, 800-1100 μm, and 1200 to 1500 μm). The mean for each bin was determined along with the standard error of the mean. Linear regression of the mean thresholds was then performed for all the four depth regions as a function of time post implantation.

Experiment 3) analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). The least squares estimate of the mean (LSM) for each detection threshold as a function of cathode phase duration and their corresponding 95% confidence interval were calculated by MANOVA; the day the thresholds were obtained was used as the experimental block.

Experiment 4) analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). The LSM for each detection threshold as a function of stimulus pulse rate and their corresponding 95% confidence interval were calculated by MANOVA; the day the thresholds were obtained was used as the experimental block. Log regression of the LSMs was performed as a function of pulse rate from 16 to 84 pulses per second.

III. Results and Discussion

A. Depth

Three regions in terms of threshold level were readily identifiable as seen in Figure 1A. First, sites 0 – 300 μm below the cortical surface (approximately layers I and II) show the highest, statistically equivalent thresholds. Second, sites 400 – 1200 μm deep represents a region of linearly decreasing threshold levels with increasing depth (R2 = 0.95). Third, sites 1300 – 1500 μm (approximately layers V and VI) showed the lowest, statistically equivalent threshold levels suggesting an ideal target for stimulation.

Figure 1. Effect of Depth and Time.

A) Detection threshold show a clear relationship with depth. The four Shallow sites (0-300 μm, solid box) have the highest thresholds while the Deep sites (1100-1500 μm, dotted box) have the lowest thresholds. The eight middle cites in negatively correlate with depth (R2 = 0.95). Clustering these eight sites into Shallow Middle and Deep Middle demonstrates the roll of depth on threshold stability B). Shallow, Shallow Middle, and Deep Middle sites significantly increase while Deep sites show no change in threshold during the first month after implantation.

B. Depth and Time

Clustering the sites into 400 μm regions of Shallow, Shallow Middle, Deep Middle and Deep highlights the effect of electrode site depth on detection threshold during the first month after implantation as seen in Figure 1B. While the threshold for all depths start relatively close to each other, over the first month after implantation sites above 1200 μm deep begin to increase, with the shallowest sites increasing fastest. However, sites at or below 1200 μm maintained their low thresholds. This finding further demonstrates that deep layers of the cortex are ideal targets for ICMS.

C. Waveform

As seen in Figure 2B) despite the elaborate experimental design, the most important factor in determining the rat’s detection threshold for a given stimulus was the duration of the cathode phase as evidenced by the linear correlation (R2 = 0.998). Further, pulses with a cathode phase duration of less 0.082 ms/Ph. had significantly lower thresholds than pulses of .205 ms/Ph. Finally, asymmetry had no significant effect of on detection threshold.

D. Pulse Rate

As seen in Figure 3A) there is a significant negative correlation between detection threshold and pulse rate from 16 to 84 PPS. However, for pulses above 84 PPS there is no significant change in detection threshold, suggesting that ICMS should limit itself to rates below 80 PPS.

Figure 3. Pulse Rate.

A) Pulse rate exhibits a strong logarithmic relationship with detection threshold for the domain of 16 to 84 P.P.S., while above 84 P.P.S. exhibits no correlation. A) Highlights significant differences between rats and B) demonstrates the variance between days for Rats I and O performing the pulse rate experiment.

E. Intra and Inter Subject Variance

For all studies there were significant differences both between rats and between rats’ performances from one day to the next as seen in figure 3A&B), although the general trends were consistent. This suggests that while mean thresholds are generally stable, stimulus levels will likely require recalibration by the subject, possibly on a daily basis.

IV. Conclusion

Developing a device that transfers information directly to the brain to help individuals suffering from sensory loss will be a challenging journey; however, we now have some notion of the nature of the vehicle which will get us there. These studies demonstrate that the electrode should target the deepest cortical layers, that the waveform stimulate with cathode leading symmetric pulse of ~100 microseconds per phase or less, that stimulation rates should be less than 80 PPS. These studies also help to highlight the significant differences between subjects as well as day to day variance within subjects suggesting the potential need for subject calibration. Future work will study the effect of multi-channel stimulation as well as the limits of ICMS for generating subjectively distinct sensations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NIDCD RO3-DC009339, and CTSI TL1 RR025759

Contributor Information

Andrew S. Koivuniemi, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA.

Kevin J. Otto, Department of Biological Sciences and the Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA..

References

- [1].House WF, “Cochlear implants,” Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, vol. 85 suppl 27, no. 3Pt2, pp. 1–93, May-Jun, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Benabid AL, Pollak P, Gao D et al. , “Chronic electrical stimulation of the ventralis intermedius nucleus of the thalamus as a treatment of movement disorders.[see comment],” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 84. no. 2. pp. 203–14. Feb, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Campbell PK, Normann RA, Horch KW et al. , “A chronic intracortical electrode array: preliminary results.,” Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, vol. 23, no. A2 Suppl, pp. 245–59, Aug, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson DJ, Najafi K, Tanghe SJ et al. , “Batch-fabricated thin-film electrodes for stimulation of the central auditory system.,” IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 693–704, Jul, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fernandez LJ, Altuna A, Tijero M et al. , “Study of functional viability of SU-8-based microneedles for neural applications,” Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, no. 2, pp. 025007, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee K, He J, Clement R et al. , “Biocompatible benzocyclobutene (BCB)-based neural implants with micro-fluidic channel,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 404–7, Sep 15, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mercanzini A, Cheung K, Buhl DL et al. , “Demonstration of cortical recording using novel flexible polymer neural probes,” Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, vol. 143, no. 1, pp. 90–96, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schuettler M, Stiess S, King BV et al. , “Fabrication of implantable microelectrode arrays by laser cutting of silicone rubber and platinum foil,” J Neural Eng, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. S121–8, Mar, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stieglitz T, Beutel H, Schuettler M et al. , “Micromachined, polyimide-based devices for flexible neural interfaces,” Biomedical Microdevices, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 283–294, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Koivuniemi A, Wilks SJ, Woolley AJ et al. , “Multimodal, longitudinal assessment of intracortical microstimulation,” Prog Brain Res, vol. 194, pp. 131–44, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Woolley AJ, Desai HA, Steckbeck MA et al. , “In situ characterization of the brain-microdevice interface using Device Capture Histology,” J Neurosci Methods, vol. 201, no. 1, pp. 67–77, Sep 30, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lilly JC, Hughes JR, Alvord EC Jr. et al. , “Brief, noninjurious electric waveform for stimulation of the brain,” Science, vol. 121, no. 3144, pp. 468–9, Apr 1, 1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hodgkin AL, and Huxley AF, “A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve,” J Physiol, vol. 117, no. 4, pp. 500–44, Aug, 1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McIntyre CC, and Grill WM, “Selective microstimulation of central nervous system neurons.,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 219–33, Mar, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fridman GY, Blair HT, Blaisdell AP et al. , “Perceived intensity of somatosensory cortical electrical stimulation,” Exp Brain Res, vol. 203, no. 3, pp. 499–515, Jun, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bartlett JR, DeYoe EA, Doty RW et al. , “Psychophysics of electrical stimulation of striate cortex in macaques,” Journal of Neurophysiology, vol. 94, no. 5, pp. 3430–42, Nov, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vetter RJ, Williams JC, Hetke JF et al. , “Chronic neural recording using silicon-substrate microelectrode arrays implanted in cerebral cortex,” IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 896–904, Jun, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sally SL, and Kelly JB, “Organization of auditory cortex in the albino rat: sound frequency.,” Journal of Neurophysiology, vol. 59, no. 5, pp. 1627–38, May, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weiland JD, and Anderson DJ, “Chronic neural stimulation with thin-film, iridium oxide electrodes.,” IEEE Transactions On Biomedical Engineering, vol. 47, no. 7, pp. 911–8, Jul, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]