Abstract

The U.S. Congress temporarily expanded the Child Tax Credit (CTC) during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide economic assistance for families with children. While formerly the CTC provided $2,000 per child for mostly middle-income parents, in July-December 2021 it provided up to $3,600 per child. Eligibility criteria were also expanded to reach more economically disadvantaged families. There has been little research evaluating the effect of the policy expansion on mental health. Using the Census Household Pulse Survey (N = 812,314) and a quasi-experimental study design, we examined effects on mental health and related outcomes among low-income adults with children and racial/ethnic subgroups. We found fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms among low-income adults. Black adults demonstrated greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared with White adults, and adults of Black, Hispanic and other racial/ethnic backgrounds demonstrated greater reductions in anxiety symptoms. There were no changes in mental healthcare utilization. These findings are important for Congress and state legislators to weigh as they consider making the CTC and other similar tax credits permanent to support economically disadvantaged families.

INTRODUCTION

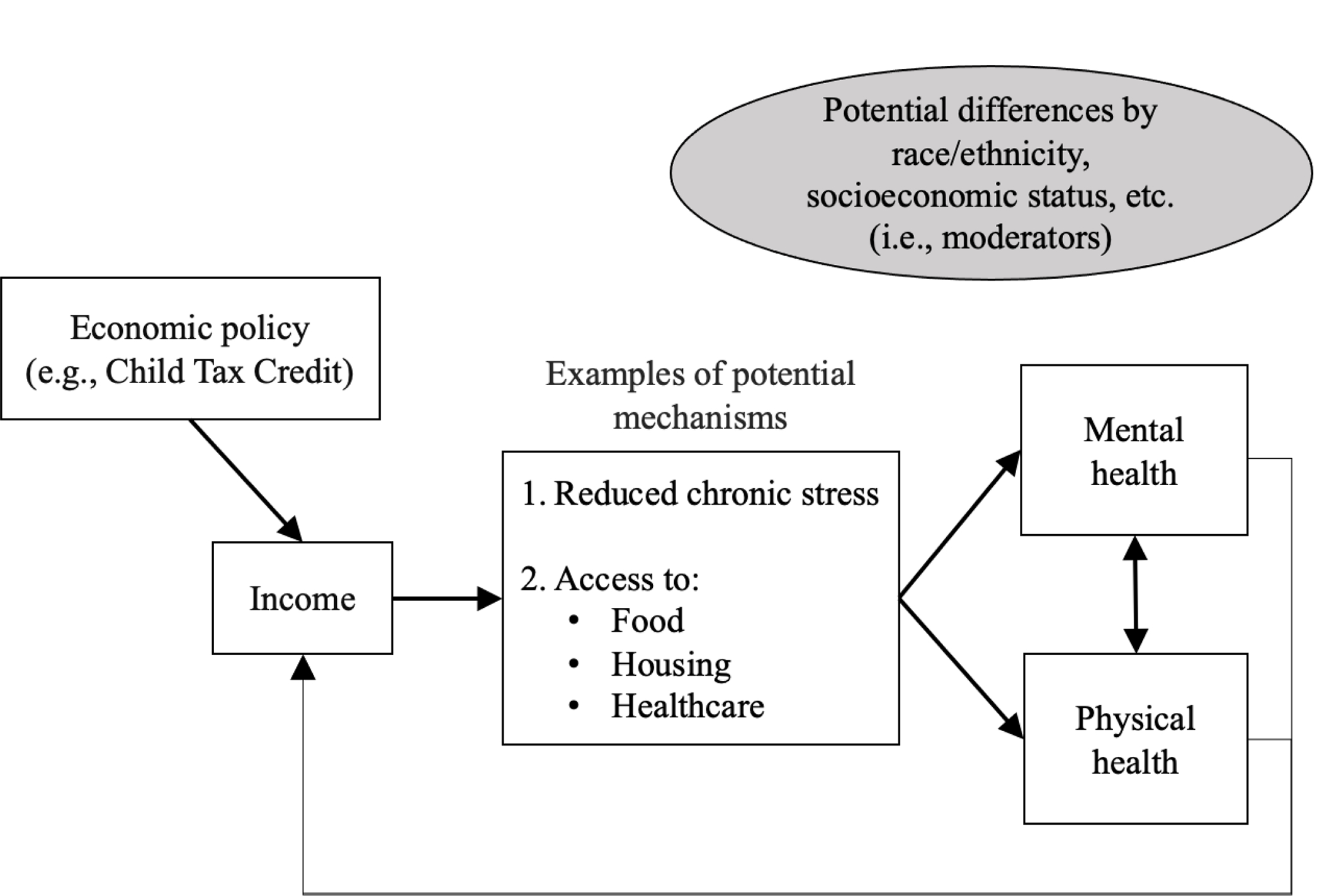

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a rapid rise in anxiety and depressive symptoms, disproportionately impacting economically disadvantaged families and people of color.(1) In June 2020, 37.8% of White adults reported adverse mental or behavioral health symptoms compared with 44.2% among Black adults and 52.1% among Hispanic adults.(2) Racial/ethnic minority groups were at increased risk of chronic stress in the pandemic as they were more likely to experience financial hardships and exacerbations of longstanding inequities in income, housing, and other social determinants of mental health.(3–7) Since poverty and financial hardship are major risk factors for stress and mental health problems, it is imperative to identify population-level polices to improve mental wellbeing among at-risk groups. Economic policies have the potential to affect mental health by addressing the social determinants of mental health like poverty, food insecurity, and healthcare access (see conceptual diagram, Exhibit 1).(8–10) These mechanisms and mental health itself can then affect physical health in the long run.(11)

Exhibit 1. Potential pathways linking economic policy, poverty, and mental health.

In response to the financial hardship caused by the pandemic, in July 2021 the U.S. government expanded the Child Tax Credit (CTC), an economic support program for families with children, as part of the American Rescue Plan Act.(12, 13) The CTC was established in 1997 to provide financial relief for middle-income families. While formerly the CTC provided up to $2,000 per child, as part of the temporary 2021 expansion it provided a maximum of $3,600 per child; it was also made fully refundable to low-income and unemployed parents. Additionally, instead of being transferred in the form of an annual tax refund, in 2021 it was disbursed as monthly advance payments that were automatically transferred into the bank accounts of eligible families who had filed taxes in 2019 or 2020. Prior to the CTC expansion, the credit was not fully refundable, i.e., one third of American children did not receive the full value of the benefit because their families did not earn enough.(14) Children with single parents, those living in rural areas, Black and Hispanic children, and those in larger families were disproportionally ineligible.(14, 15) In contrast, about 90% of children were eligible for the expanded CTC, which was fully refundable, and benefits were larger for lower-income families.

There has been limited work examining the effects of the expanded CTC, with studies suggesting it reduced child poverty by nearly half, and reduced material hardship and food insufficiency.(16–21) There are no studies to our knowledge on its mental health effects. There is, however, existing evidence on another major poverty alleviation program for low-income families with children, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), showing the potential promise of poverty alleviation programs more generally. For example, the EITC has been shown to improve family income, housing, and access to health insurance, and to improve stress and mental health.(22–29) Studies suggest that the EITC’s benefits have particularly benefited Black families.(8, 30) Yet the EITC is disbursed as an annual refund rather than monthly payments, and individuals must work to receive it, so EITC studies do not necessarily generalize to the potential impacts of the CTC, with its monthly payments and near-universality (including broader coverage of immigrant families).

This study addresses this critical gap by examining whether the 2021 CTC expansion improved mental health among adults with children, and specifically for low-income individuals and racial/ethnic minorities. Because of historical marginalization and structural racism, these groups have less wealth and lower income on average than higher-income and White individuals and therefore may have benefited more from this new source of income. The expanded CTC expired at the end of 2021, and Congress continues to debate whether to make the expansion permanent, while state governments consider their own similar programs.(31) Evidence is therefore urgently needed to inform such conversations.

METHODS

Sample

The sample was drawn from the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a nationally representative repeated cross-sectional internet survey that began in April 2020 and continues weekly through the present.(32) The Census Bureau randomly selects HPS participants, who then complete an internet-based survey. We used data from waves 28–41 (April 14, 2021 to January 10, 2022) (N=944,189). Since the first monthly payment for the expanded CTC was made on July 15, 2021 (just before wave 34) and the last payment was made on December 15, 2022 (during wave 41), this provides 6 waves of pre-policy and 7 waves of post-policy data. Of note, a final larger lump-sum CTC payment was made during the spring of 2022 to those who filed taxes or claimed economic impact payments; our approach excluded observations during this period because of the ambiguity regarding defining the exposure period and potential recipients. Finally, we restricted the sample to respondents who provided responses on the mental health outcomes of interest (N = 812,314).

Exposure

CTC-eligible individuals with children under 18 whose interviews occurred during July-December 2021 were considered “exposed” to the expanded CTC. Furthermore, those with lower incomes were considered to have received the strongest exposure, since their benefits were larger than those with higher incomes.

In particular, the 2021 expansion increased CTC benefits from a maximum of $2,000 to a maximum of $3,600 per child for children under age 6 years, and up to $3,000 per child age 6–17. Instead of being disbursed as part of an annual tax refund, the payment mode was changed to monthly advance payments. The full credit was available to single filers, heads of household, and married couples filing jointly with modified adjusted gross incomes under $75,000, $112,500, and $150,000, respectively, for the 2021 tax year. This included those with zero earned income. The credit was phased out when income exceeded these thresholds. The first phase-out occurred when income exceeded these thresholds but was below $400,000 (married filing jointly) or $200,000 (all other filing statuses). The total credit per child was reduced by $50 for each $1,000 (or a fraction thereof). The credit would not be reduced below $2,000 under this phase-out. The second phase-out applied to taxpayers with income more than $400,000 (married filing jointly) or $200,000 (other filing statuses). In this phase-out, the total credit per child was reduced $50 for each $1,000, and the credit could drop below $2,000 until it reached $0. Prior to the 2021 expansion, the CTC was not available to those with earnings below $2,500, and those with lower incomes did not earn enough to qualify for the full amount (i.e., it was not fully refundable). Because of these changes to eligibility criteria, 88% of American families with children (39 million households) were eligible to receive payments beginning July 15, 2021.(33)

In this analysis, we assumed that eligible people received the credit (an approach similar to prior studies of the EITC and other safety net programs where administrative data on benefit receipt is unavailable).(8, 24, 25, 34) Notably, 65.4% of our sample who seemed eligible based on their self-reported demographic characteristics reported that they received the CTC, which indicates that our approach may involve some degree of measurement error. Notably, prior work has indicated that self-reported receipt of safety net benefits is unreliable; this may especially be the case if individuals were not aware of the automatic deposits into their bank accounts.(35)

Outcomes

We included several mental health outcomes measured in the HPS. First, depressive symptoms were captured using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2). In the PHQ-2, respondents are asked how often they have been bothered by 1) having little interest or pleasure in doing things and 2) feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. Answers range from “not at all” to “nearly every day.” The two items are typically combined, and scores ≥3 indicate high risk of depression.(36)

Second, the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) scale is a brief screening tool for generalized anxiety disorder. Individuals are asked if they are 1) feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge, and 2) not able to control or stop worrying in the past two weeks; and again how often they experience these symptoms.(37) A GAD-2 score ≥3 is considered high risk for anxiety.

We also included two binary outcomes capturing mental healthcare utilization, including mental health counseling or therapy within the last 4 weeks, or medication to help with emotions, behavior, or concentration.

Covariates

We adjusted models for variables representing potential confounders of the relationship between CTC receipt and the outcomes: gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, number of children, and education. We also included fixed effects for bi-weekly survey wave to account for secular trends in mental health that occurred during this period due to underlying factors affecting all individuals.

Statistical Analysis

Primary Analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics stratified by (1) whether households included children and (2) whether the interview was conducted after the CTC expansion.

We then estimated the effect of the expansion using a difference-in-difference-in-differences (i.e., triple-difference, or DDD) approach. DDD analysis builds on traditional difference-in-differences (DID) analysis, which is a quasi-experimental technique suited to examining the effects of policy changes while accounting for underlying trends.(38, 39) These methods compare pre-post changes in outcomes among a “treatment” group (i.e., adults with children), while “differencing out” underlying secular trends in outcomes in a “control” group (i.e., adults without children). The triple-difference approach enables further refinement of the treatment and control groups to estimate the effects on subgroups most affected by the policy. Specifically, we included an additional set of interaction terms between the primary exposure variable and a binary variable for whether an individual’s income was below $35,000. This is because the lowest-income households were the primary beneficiaries of the expanded CTC, as they were more likely to be newly eligible and to receive the largest payments.

The triple interaction term in DDD models was therefore composed of three variables: (1) an indicator for whether the interview occurred after (versus before) the CTC expansion, (2) an indicator variable for adults with (versus without) children; and (3) an indicator variable for whether the individual belonged to a lower (versus higher) income group. The equation for the analysis and additional details about model assumptions are included in the Appendix, including Appendix Exhibits A1–3.

Secondary Analyses

Subgroup Analyses

We evaluated whether the CTC had a greater impact on mental health among racial/ethnic subgroups that may be more likely to benefit from the income boost. To do so, we conducted additional DDD analyses, including an interaction term between race/ethnicity and the primary exposure variable (i.e., the interaction between pre-post expansion and adults with versus without children).

Sensitivity Analyses

As an additional sensitivity analysis, we assessed whether there were changes in the effects of the monthly CTC payments over time (e.g., whether mental health improved initially but then returned to baseline). To do so, we modified the main analysis to include a categorical variable for bi-weekly survey wave instead of using a binary pre-post variable to represent time. Second, to account for missing values for key covariates, we conducted multiple imputation using chained equations (see Appendix).

Ethical Approval

This study involved publicly available de-identified data. Ethical approval was not required.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The final sample included adults with children (112,862 observations before and 145,429 after the CTC expansion) and adults without children (237,901 observations before and 316,122 after the expansion) (Exhibit 2). Adults with children were more likely to be younger, married, Hispanic, Black, and less educated compared to adults without children. Indicators of mental health were worse among adults with children. Importantly, DID analysis does not require that characteristics of the treatment and control group be similar, but rather that trends (i.e., slopes) in outcomes be parallel during the pre-revision period. Descriptions of the results of analyses to evaluate the validity of model assumptions are provided in the Appendix.

Exhibit 2.

Sample characteristics

| Before July 15,2021 | After July 15,2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Adults without children | Adults with children | Adults without children | Adults with children | |

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) or Percent | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age | 57.3 (15.3) | 44.8 (11.9) | 56.1 (15.9) | 44.0 (11.9) |

| Male | 42.7 | 36.9 | 42.9 | 36.6 |

| Married | 53.9 | 70.7 | 52.7 | 69.9 |

| Less than high school or high school | 11.9 | 13.1 | 12.2 | 13.2 |

| Income | ||||

| Less than $25,000 | 10.7 | 8.9 | 11.7 | 9.5 |

| $25,000, $34,999 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 7.5 |

| $35,000, $49,999 | 10.9 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 9.0 |

| $50,000, $74,999 | 18.2 | 14.9 | 18.1 | 14.6 |

| $75,000, $99,999 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 14.6 | 13.7 |

| $100,000, $149,999 | 17.9 | 20.4 | 17.3 | 20.3 |

| $150,000, $199,999 | 8.8 | 10.6 | 8.2 | 10.8 |

| $200,000 and above | 9.8 | 14.8 | 9.5 | 14.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 79.3 | 68.9 | 78.9 | 68.6 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.3 | 8.5 | 6.4 | 8.7 |

| Asian | 4.5 | 6.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 |

| Hispanic | 6.0 | 10.2 | 6.4 | 10.4 |

| Other | 3.9 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 5.8 |

| Mental Health Outcomes | ||||

| Depressive symptoms (continuous) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.8) |

| Depressive symptoms (score ≥ 3) | 16.4 | 18.4 | 17.2 | 19.9 |

| Anxiety symptoms (continuous) | 1.8 (1.9) | 2.1 (2.0) | 1.5 (1.9) | 19 (2) |

| Anxiety symptoms (score ≥ 3) | 20.1 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 29.3 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

| Utilization of mental health services | 16.5 | 21.8 | 18.4 | 23.3 |

| Mental health prescription | 22.4 | 23.6 | 23.9 | 24.6 |

| Confident in ability to pay mortgage/rent | 78.3 | 72.3 | 75.8 | 70.3 |

| Difficulty with household expenses | 34.8 | 45.1 | 37.5 | 49.9 |

| Food sufficiency | 81.3 | 74.0 | 80.4 | 73.6 |

| N | 237,901 | 112,862 | 316,122 | 145,429 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey

Note: N = 812,314. Data were drawn from the Household Pulse Survey, April 14, 2021-January 10, 2022, including individuals with non-missing information on the mental health outcomes of interest. Depressive symptoms were captured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 scale, and anxiety symptoms were captured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 scale; both were dichotomized at the standard cut-off of 3 or more to indicate high risk of mental health problems. Not married category includes single, divorced, widowed, separated. SD: standard deviation.

Effects of CTC Expansion

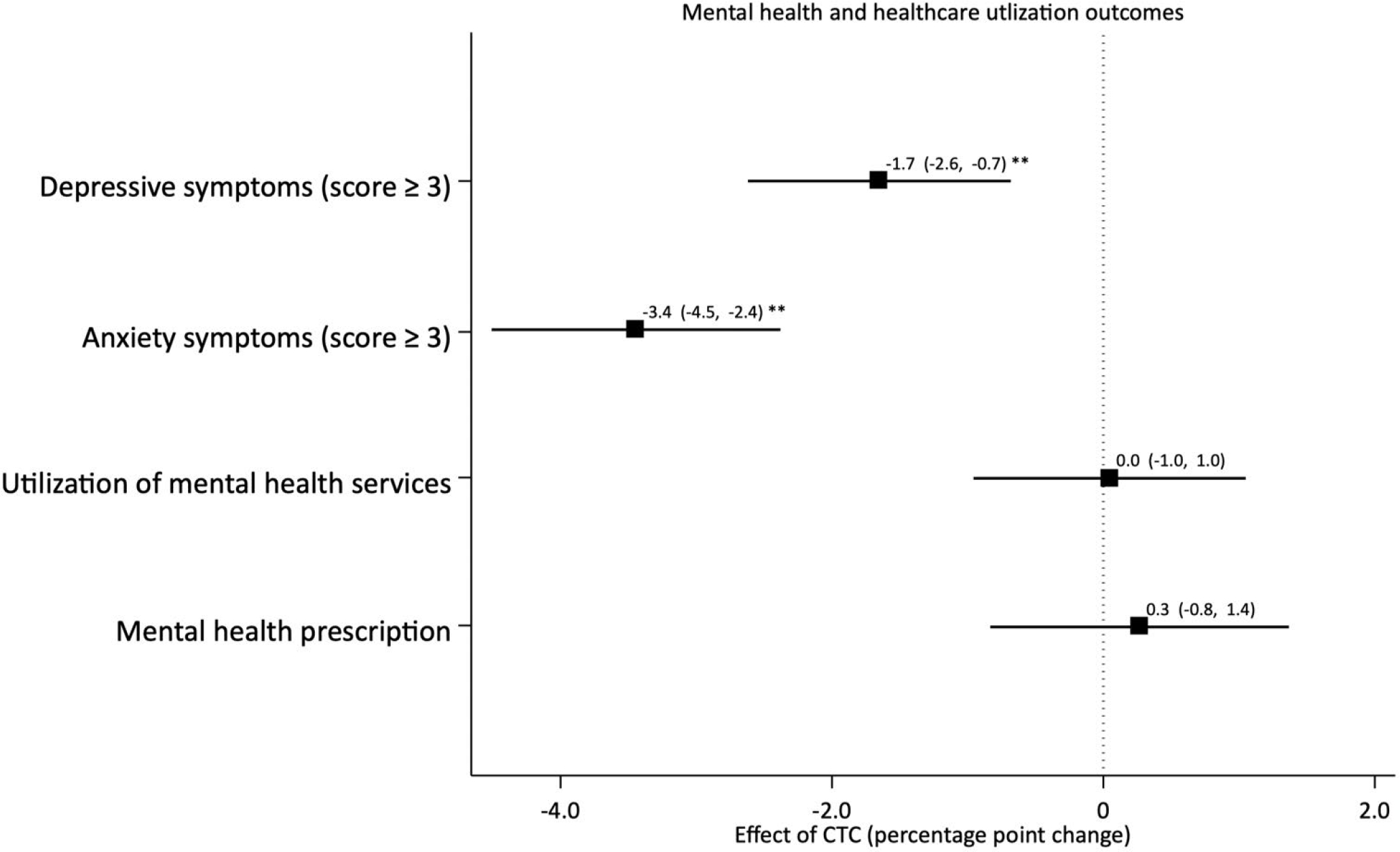

The CTC expansion was associated with decreased depressive (−1.7, 95% CI: −2.6, −0,7) and anxiety (−3.4, 95% CI: −4.5, −2.4) symptoms among low-income adults with children (Exhibit 3). We did not observe an association with utilization of mental health services or prescriptions.

Exhibit 3. Effects of the 2021 Child Tax Credit expansion on mental health and healthcare utilization Source:

Authors’ analysis of data from U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey Note: **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Coefficients are plotted as point estimates (boxes) with 95% confidence intervals (whiskers). Coefficients are derived from models in which the primary exposure is a triple interaction term between an indicator for whether the interview occurred after (versus before) the CTC expansion, a binary variable representing adults with (versus without) children, and a binary variable for whether the interviewee belonged to a lower (versus higher) income group. All regressions adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, number of children, and level of education as well as fixed effects for bi-weekly waves. Depressive symptoms were captured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 scale, and anxiety symptoms were captured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 scale; both were dichotomized at the standard cut-off of 3 or more to indicate high risk of mental health problems.

Secondary Analyses

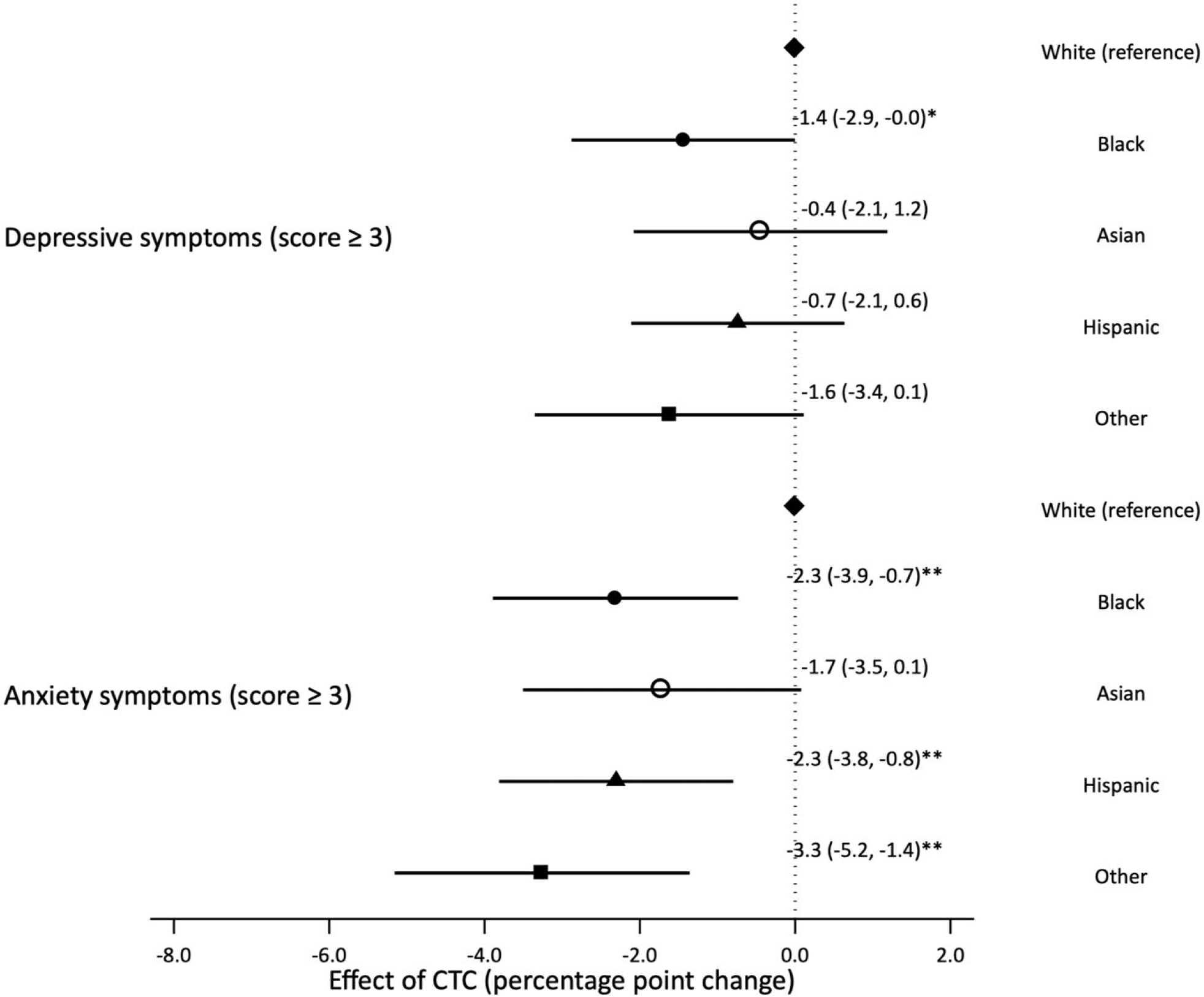

In subgroup analyses by race/ethnicity (Exhibit 4), there was a larger decrease in both depressive and anxiety symptoms among Black adults compared with White adults with children (interaction term coefficient for Black versus White −1.4for depressive symptoms, 95% CI: −2.9, −0.00; −2.3 for anxiety symptoms, 95% CI: −3.9, −0.7). Adults of Hispanic and other racial/ethnic backgrounds also experienced greater reductions in anxiety compared with White adults (interaction term coefficient for Hispanic −2.3, 95% CI: −3.9, −0.7; interaction term coefficient for other racial/ethnic groups −3.3, 95% CI: −5.2, −1.4). There were no differences for Asian families compared with White families for and outcomes, and there were no significant differences by race/ethnicity in mental healthcare utilization (Appendix Exhibit A4).

Exhibit 4. Racial differences in the effects of the 2021 Child Tax Credit expansion on mental health.

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey

Note: **p < 0.01, *p<0.05. Coefficients are plotted as point estimates (boxes) with 95% confidence intervals (whiskers). Coefficients are derived from models in which the primary exposure is a triple interaction term between an indicator for whether the interview occurred after (versus before) the CTC expansion, a binary variable representing adults with (versus without) children, and a binary variable for whether the interviewee belonged to a given racial/ethnic group (reference category: White). All regressions adjust for gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, number of children, and level of education as well as fixed effects for bi-weekly waves. Depressive symptoms were captured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 scale, and anxiety symptoms were captured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 scale; both were dichotomized at the standard cut-off of 3 or more to indicate high risk of mental health problems.

In the secondary analysis in which we examined whether the mental health effects of monthly CTC payments changed over time, there were no clear trends to suggest either early or accumulated beneficial effects (Appendix Exhibit A5). In the secondary analysis in which we imputed missing values for income, the results were similar to findings for the main analysis, suggesting that complete case analysis omitting those with missing income did not contribute to bias (Appendix Exhibit A6–7).

DISCUSSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Child Tax Credit was temporarily expanded to millions of families for the first time, allowing 27 million additional children from the most economically disadvantaged families to receive the full benefit size.(40) This study examined the effects of this increased income on mental health among adults with children using a large serial cross-sectional national data set and rigorous quasi-experimental analyses. We found that the expanded CTC was associated with reduced anxiety symptoms among low-income adults with children, as well as greater mental health benefits among Black and Hispanic individuals. Previous studies have also shown a link between financial hardship and mental health.(41, 42) In the overall sample and among each subgroup, there was no change in mental healthcare visits or prescriptions, suggesting that healthcare utilization was not the primary pathway explaining the results.

The reduction in the prevalence of clinically meaningful anxiety symptoms (3.4% points) represents a 13.3% reduction from baseline anxiety levels (25.5%) among adults with children. While this may be a modest change in risk at the individual level, this represents a meaningful change in the distribution at the population level,(43) particularly considering the challenging pandemic-related circumstances during which it was implemented, and potential cumulative effects if the benefit were to be extended. The effect size is consistent with prior research finding that the other major U.S. anti-poverty program—the EITC—also improves long-run mental health among recipients.(22, 44) In fact, one prior paper examining the short-term impacts of the EITC found no effects on mental health;(45) it may be that the more regular payments of the expanded CTC were more effective in this respect. Additionally, while receipt of some public benefits may lead to feelings of stigma that reduce participation or worsen mental health,(46–48) the expanded CTC benefit was nearly universal with few administrative burdens among those who received automatic benefits, perhaps allowing it to be more impactful for mental health.(49)

We also noted that the mental health benefits of the CTC expansion were largest among adults of Black, Hispanic, and other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Of note, these groups stood the most to gain from the expanded CTC. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black and Hispanic families reported higher rates of job loss, 44 percent and 38 percent in October 2021 respectively, compared to 23 percent for White families, with similar disparities during earlier periods.(50) Due to historical and current structural racism and marginalization, these groups also have less wealth and therefore less ability to withstand acute and chronic economic adversity.(8, 30, 51) Hispanic families are also more likely to be ineligible for other safety net policies because of immigration status, perhaps making the CTC a more salient program for them. For example, the federal EITC is only available to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, while the CTC was available to mixed immigration-status families as long as the child had a social security number. In contrast, we found that Asian individuals benefited similarly to White individuals. While Asians overall are likely to be of higher socioeconomic position than other communities of color, this may mask disparities within this heterogeneous group.

When examining one possible mechanism through which the increased income from the CTC may have improved mental health, we found no changes in mental healthcare utilization or prescriptions, suggesting that these were not the primary pathway explaining the reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms, at least in the short term and in context of altered utilization patterns during the pandemic. However, recent studies using this data set and similar study designs have noted that the monthly CTC payments resulted in reductions in markers of financial hardship, with improved food sufficiency and more confidence in the ability to pay for housing.(17, 52) This is consistent with prior studies that have also shown that food sufficiency and reduced financial hardship are associated with improved mental health.(53–55)

This study has several strengths, including the use of a large serial cross-sectional diverse national data set, and a rigorous quasi-experimental study design. It provides timely evidence on a policy which is actively being debated by federal and state legislatures. The study also has limitations. One is that the HPS is a repeated cross-sectional survey, so we cannot observe changes in specific individuals’ mental health after receiving CTC benefits as we could in a panel dataset. Additionally, HPS suffers from a high rate of non-response as with many other national surveys; results therefore may not generalize to those not included in this study. Another limitation is that covariates and outcomes were self-reported and may suffer from standard reporting biases. Finally, as with any DID analysis, there may be residual confounding based on contemporaneous policy changes or other exposures that differentially affected the treatment and control groups; we evaluated several model assumptions to lessen concerns about this issue.

The 2021 CTC expansion reduced child poverty by half, but its expiration caused millions of children to fall back into poverty.(18) Our study adds to a small but growing body of work that shows that the CTC not only increased food sufficiency but also improved mental health among adults with children, particularly the most marginalized groups. By reducing financial hardships, this policy has the potential to improve the environments in which vulnerable low-income children grow up. These findings are important for Congress and state legislators to weigh as they consider making the CTC and other similar tax credits permanent to support economically disadvantaged families, particularly as the economic recovery from the pandemic drags on, and as already marginalized families continue to be left behind.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. Readers who wish to access the final published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to url for the pay version https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00733 or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

REFERENCES

- 1.McKnight-Eily LR, Okoro CA, Strine TW, Verlenden J, Hollis ND, Njai R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(5):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(32):1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Primm AB, Vasquez MJT, Mays RA, Sammons-Posey D, McKnight-Eily LR, Presley-Cantrell LR, et al. The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Preventing chronic disease. 2010;7(1):A20–A. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P. Mental Health in the Context of Health Disparities. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008. 2008/09/01;165(9):1102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galea S, Abdalla SM. COVID-19 Pandemic, Unemployment, and Civil Unrest: Underlying Deep Racial and Socioeconomic Divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall LR, Sanchez K, da Graca B, Bennett MM, Powers M, Warren AM. Income differences and COVID-19: impact on daily life and mental health. Population Health Management. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonzo D, Popescu M, Zubaroglu Ioannides P. Mental health impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on parents in high-risk, low income communities. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022. May;68(3):575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batra A, Hamad R. Short-term effects of the earned income tax credit on children’s physical and mental health. Ann Epidemiol. 2021. Jun;58:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughman RA. Evaluating the impact of the earned income tax credit on health insurance coverage. National Tax Journal. 2005:665–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chetty R, Friedman JN, Saez E. Using Differences in Knowledge Across Neighborhoods to Uncover the Impacts of the EITC on Earnings. The American Economic Review. 2013;103(7):2683–721. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic Disparities In Health: Pathways And Policies. Health Affairs. 2002 March 1, 2002;21(2):60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crandall-Hollick ML. The Child Tax Credit: temporary expansion for 2021 under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117–2). Congressional Research Service.2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, HR 1319, 117th Cong (2021–2022). [cited 2022 May 25]; Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319.

- 14.Collyer S, Harris D, & Wimer C Left behind: The one-third of children in families who earn too little to get the full Child Tax Credit. New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran MA, & Collyer S Children left behind in larger families: The uneven receipt of the Federal Child Tax Credit by children’s family size. New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parolin Z, Ananat E, Collyer SM, Curran M, Wimer C. The initial effects of the expanded Child Tax Credit on material hardship. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. 2021;No. 29285. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafer PR, Gutiérrez KM, Ettinger de Cuba S, Bovell-Ammon A, Raifman J. Association of the Implementation of Child Tax Credit Advance Payments With Food Insufficiency in US Households. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(1):e2143296–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coughlin CG, Bovell-Ammon A, Sandel M. Extending the Child Tax Credit to break the cycle of poverty. JAMA Pediatr. 2021. Nov 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Lopez D Household Pulse Survey Collected Responses Just Before and Just After the Arrival of the First CTC Checks. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roll S, Chun Y, Brugger L, Hamilton L. How are families in the U.S. using their Child Tax Credit payments? A 50 state analysis. St. Louis, Missouri: Social Policy Institute. Washington University in St. Louis.2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton L, Roll S, Despard M, Maag E, Chun Y, Brugger L, et al. The impacts of the 2021 expanded child tax credit on family employment, nutrition, and financial well-being: Findings from the Social Policy Institute’s Child Tax Credit Panel (Wave 2). Brookings Global Working Paper No. 173. Washington, D.C.: Global Economy and Development Program at Brookings; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields-Zeeman L, Collin DF, Batra A, Hamad R. How does income affect mental health and health behaviours? A quasi-experimental study of the earned income tax credit. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021. Oct;75(10):929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehkopf DH, Strully KW, Dow WH. The short-term impacts of Earned Income Tax Credit disbursement on health. International journal of epidemiology. 2014;43(6):1884–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholz JK. The earned income tax credit:participation, compliance, and antipoverty effectiveness. National Tax Journal. 1994;47(1):63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmeiser MD. Expanding wallets and waistlines: the impact of family income on the BMI of women and men eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit. Health Econ. 2009. Nov;18(11):1277–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romich JL, Weisner TS. How families view and use the EITC: advance payment versus lump sum delivery. National Tax Journal. 2000. December;53(4). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilkauskas N, Michelmore K. The effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on housing and living arrangements. Demography. 2019. Aug;56(4):1303–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozawa MN, Hong B-E. The effects of EITC and children’s allowances on the economic well-being of children. Social Work Research. 2003;27(3):163–78. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noonan MC, Smith SS, Corcoran ME. Examining the impact of welfare reform, labor market conditions, and the Earned Income Tax Credit on the employment of black and white single mothers. Social Science Research. 2007. 2007/03/01/;36(1):95–130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komro KA, Markowitz S, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity. Health equity. 2019;3(1):61–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Personal Income Tax Law: Earned Income Tax Credit: Young Child Tax Credit. 2021–2022. [updated 04/15/21; cited 2022 April 23]; Available from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220SB691.

- 32.US Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey: measuring social and economic impacts during the coronavirus pandemic. [cited 2022 April 19]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey.html.

- 33.Treasury and IRS Announce Families of 88% of Children in the U.S. to Automatically Receive Monthly Payment of Refundable Child Tax Credit. First Payments to Be Made on July 15: U.S. Department of the Treasury; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahl GB, Lochner L. The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. The American Economic Review. 2012;102(5):1927–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celhay PA, Meyer BD, Mittag N. Errors in Reporting and Imputation of Government Benefits and Their Implications. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. 2021;No. 29184. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003. Nov;41(11):1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, Chanpura T, Lopp L. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a Primary Care Setting. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8224–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basu S, Meghani A, Siddiqi A. Evaluating the Health Impact of Large-Scale Public Policy Changes: Classical and Novel Approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017. Mar 20;38:351–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. Jama. 2014. Dec 10;312(22):2401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marr C, Cox K, Hingtgen S, Windham K. Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent. Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azuine RE, Singh GK. Father’s Health Status and Inequalities in Physical and Mental Health of U.S. Children: A Population-Based Study. Health Equity. 2019. 2019/07/01;3(1):495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis G, Rice F, Harold GT, Collishaw S, Thapar A. Investigating Environmental Links Between Parent Depression and Child Depressive/Anxiety Symptoms Using an Assisted Conception Design. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011. 2011/05/01/;50(5):451–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002. Apr;77(4):371–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dow WH, Godøy A, Lowenstein C, Reich M. Can Labor Market Policies Reduce Deaths of Despair? Journal of Health Economics. 2020. 2020/12/01/;74:102372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collin DF, Shields-Zeeman LS, Batra A, Vable AM, Rehkopf DH, Machen L, et al. Short-term effects of the earned income tax credit on mental health and health behaviors. Preventive Medicine. 2020;139:106223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powell L, Amsbary J, Xin H. Stigma as a Communication Barrier for Participation in the Federal Government’s Women, Infants, and Children Program. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication. 2015. 2015/01/01;16(1):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuber J, Kronebusch K. Stigma and other determinants of participation in TANF and Medicaid. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2004;23(3):509–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaines-Turner T, Simmons JC, Chilton M. Recommendations From SNAP Participants to Improve Wages and End Stigma. American Journal of Public Health. 2019. 2019/12/01;109(12):1664–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smeeding T Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means, by Pamela Herd and Donald P. Moynihan, New York, NY: Russell Sage, 2018, 360 pp., $37.50 (list). Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2019 2019/09/01;38(4):1077–82. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. 2021. [cited 2022 May 25]; Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and.

- 51.Batra A, Karasek D, Hamad R. Racial Differences in the Association between the U.S. Earned Income Tax Credit and Birthweight. Womens Health Issues. 2021. Oct 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parolin Z, Curran M, Matsudaira J, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Monthly poverty rates in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. New York City, New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty & Social Policy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park N, Heo W, Ruiz-Menjivar J, Grable JE. Financial Hardship, Social Support, and Perceived Stress. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning. (2):322–32. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myers CA. Food Insecurity and Psychological Distress: a Review of the Recent Literature. Curr Nutr Rep. 2020. Jun;9(2):107–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang D, Thomsen MR, Nayga RM. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2021. 2021/03/29;21(1):607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.