Abstract

Introduction

Aggrecanopathies are rare disorders associated with idiopathic short stature. They are caused by pathogenic changes in the ACAN gene located on chromosome 15q26. In this study, we present a case of short stature caused by mutations in the ACAN gene.

Case Presentation

A 3-year-3-month-old male patient was referred to us because of his short stature. Physical examination revealed proportional short stature, frontal bossing, macrocephaly, midface hypoplasia, ptosis in the right eye, and wide toes. When the patient was 6 years and 3 months old, his bone age was compatible with 7 years of age. The patient underwent clinical exome sequencing and a heterozygous nonsense c.1243G>T, p.(Glu415*) pathogenic variant was detected in the ACAN gene. The same variant was found in his phenotypically similar father. Our patient is the second case with ptosis.

Discussion

ACAN gene mutation should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with idiopathic short stature. The development and widespread use of next-generation sequencing technology has increased the diagnostic and treatment possibilities.

Keywords: Short stature, Aggrecanopathies, ACAN

Established Facts

Aggrecanopathies are rare disorders associated with idiopathic short stature.

They are caused by pathogenic changes in the ACAN gene located on chromosome 15q26.

Novel Insights

Although the incidence of macrocephaly is low, it should be noted that it is among the expected findings.

Our patient is the second case with ptosis.

Introduction

Idiopathic short stature is found in a very large and heterogeneous group of diseases. The development and widespread use of next-generation sequencing technology increases the rate of definitive diagnoses in patients with idiopathic short stature. Aggrecanopathies are a rare group of diseases with idiopathic short stature and are caused by pathogenic mutations in the ACAN gene, which consists of 19 exons (774,224 bp) located on chromosome 15q26. Aggrecan, encoded by this gene, is the main component of epiphyseal plate, articular cartilage, and intervertebral disc and is expressed in many tissues [Uchida et al., 2020]. As a result of mutations affecting aggrecan synthesis, a clinical picture characterized by forward/backward bone age, early epiphyseal fusion, and early growth stopping occurs. A large number of mutations have been identified in this gene so far [Gleghorn et al., 2005; Stattin et al., 2008, 2010; Tompson et al., 2009; Quintos et al., 2015; Dateki et al., 2017; Gkourogianni et al., 2017; van der Steen et al., 2017]. Homozygous mutations of ACAN have been associated with spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, aggrecan type (SEMD, OMIM #612813). Mutations in the heterozygous state have been associated with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia Kimberley type (SEDK, OMIM #608361) and short stature, advanced bone age, with or without early-onset osteoarthritis and/or osteochondritis dissecans (SSOAOD, OMIM #165800).

Case Presentation

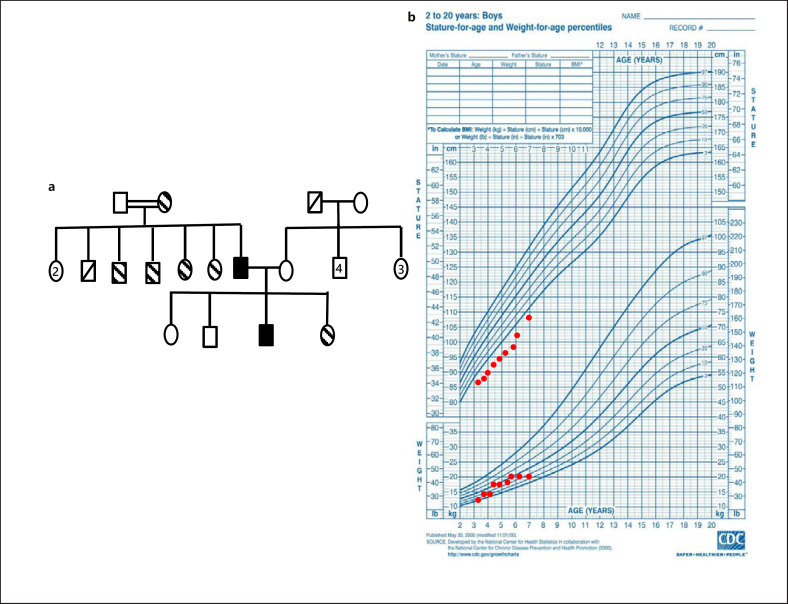

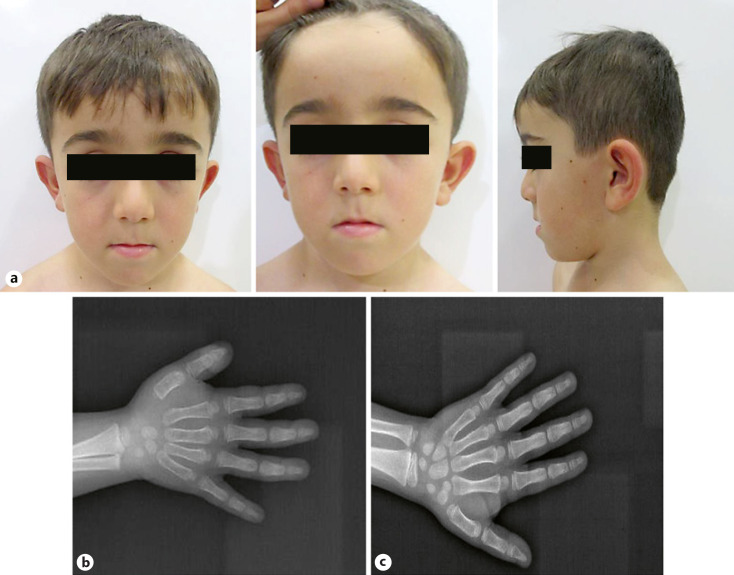

A 3-year-3-month-old male patient presented with short stature. He was born at term by cesarean section without any problems (weight 3,200 g). There was no consanguinity between his parents. His father had a history of short stature in his father's brothers and sisters (Fig. 1a). At 3 years and 7 months of age, body weight was 13.3 kg (−1.45 SDS), height was 89.1 cm (−2.77 SDS), head circumference was 53 cm (+1.66 SDS), stroke length was 88 cm, upper segment versus lower segment ratio was 1.46 (greater than +2 SDS) [Turan et al., 2005; Neyzi et al., 2015]. His mother's height was 157.6 cm (−0.93 SDS), his father's height was 146.1 cm (−4.84 SDS), and his estimated adult height was 158.3 cm (−2.89 SDS). The patient was followed up clinically at 3-month intervals. When he was 4 years and 10 months old, his height was 96.4 cm (−3.09 SDS) (Fig. 1b). The annual growth rate was 5.8 cm/year (Table 1). Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, frontal bossing, ptosis of the right eye, midface hypoplasia, flat face, retrognathia and micrognathia, short neck, mild pectus excavatum, pes planus, and wide toes (Fig. 2a). Puberty was Tanner stage 1.

Fig. 1.

a Pedigree of the family with short stature. Striped symbols denote family members with short stature and the same dysmorphic facial features; black symbols denote the proband and his father. b Percentile curve of the proband.

Table 1.

Clinical information of our patient with ACAN mutation

| Patient data | |

|---|---|

| Birth characteristics | |

| Weight, g | 3,200 |

| Length, cm | NA |

| Head circumference, cm | NA |

| Physical examination | |

| Age, years | 4.8 |

| Weight, kg | 16.4 |

| Length, cm | 96.4 |

| Head circumference, cm | 54 |

| Target height, cm | 158.3 |

| Arm span, cm | 94 |

| Sit height, cm | 56 |

| Arm span/height | 1.02 |

| Sit height/height | 0.58 |

| Annual growth, cm/year | 5.8 |

| Chronological age, years | 6 |

| Bone age, years | 7 |

| Endocrine evaluation | |

| IGFBP-3 (ng/mL) (900–4,300) | 2,530 |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) (14.9–189) | 45.3 |

| GH stimulation test | NA |

IGFBP-3, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; GH, growth hormone; NA, not available.

Fig. 2.

a Photographs of the patient. b The chronological age is compatible with the bone age in the wrist radiograph of the patient, which was taken at the age of 3 years. c In the wrist X-ray taken at the age of 6, the bone age is compatible with the age of 7 years.

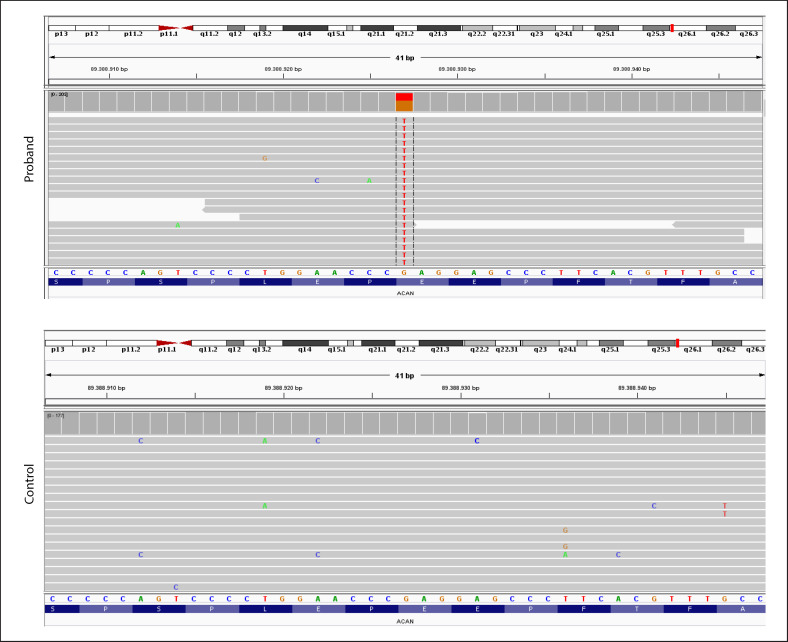

Complete blood count, biochemistry panel, inflammatory markers, celiac screening, hepatic-renal-thyroid function tests, IGF, IGFBP-3, and 25-OH vitamin D3 were normal (Table 1). In the bone survey, bone structures were in normal morphology. After obtaining informed consent from the patient's parents, clinical exome sequencing encompassing 4,490 genes was performed with the prediagnosis of skeletal dysplasia in the patient and his father. A heterozygous nonsense c.1243G>T, p.(Glu415*) pathogenic variant in the ACAN gene (NM_001135) was detected in the patient and his father (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Integrative genomics viewer image of the proband and control. c.1243G>T in the ACAN gene.

At the last admission to our clinic, the patient was 6 years and 3 months old. Bone age was consistent with 7 years in the re-examination of the hand (Fig. 2b, c). The patient had no joint findings. His father, on the other hand, had lumbar disc herniation, while there were no joint findings. Based on the variant detected in our patient and his father, his clinical findings were re-evaluated and short stature associated with advanced bone age was found to be compatible with SSOAOD. Prolonged follow-up for the patient is being carried out in the Department of Pediatric Endocrinology. When growth is found to be insufficient, administration of growth hormone is planned.

Molecular Analysis

DNA isolation from the peripheral blood samples was performed using the MagNAPure LC DNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and the MagNAPure LC 2.0 (Roche Diagnostic Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland) device according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of DNA concentration and enrichment of the library was performed with a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies Holdings Pte Ltd., Malaysia). Library size distribution was measured with Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Clinical Exome Solution kit (SOPHiA GENETICS, Saint-Sulpice, Switzerland) was used for library preparation and exome enrichment. DNA sequencing was performed on Illumina NextSeq 500 instrument (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Bioinformatic analysis was carried out via Sophia DDM version 5.10.8 (SOPHiA GENETICS).

Discussion and Conclusion

The ACAN gene is one of the genes whose importance is increasing in the etiology of idiopathic short stature [Tompson et al., 2009; Nilsson et al., 2014; Gkourogianni et al., 2017]. To date, 97 pathogenic/probably pathogenic variants have been reported in the Varsome database. Most of these variants are nonsense (34) and frameshift (38) (https://varsome.com/gene/ACAN).

Here, we present a case in which we detected a heterozygous nonsense c.1243G>T, p.(Glu415*) pathogenic variant in the ACAN gene. The clinical features of our case are similar to the previously reported patients with ACAN mutation. Short stature, midface hypoplasia, frontal bossing, and wide big toes are common features [Stattin et al., 2010; Nilsson et al., 2014; Dateki, 2017; Gkourogianni et al., 2017; Tatsi et al., 2017; van der Steen et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Mancioppi et al., 2021]. Macrocephaly is not a common finding. However, 1 case by Mancioppi et al. [2021], 2 cases by Sentchordi-Montané et al. [2018], 1 case by Nilsson et al. [2014], and 3 cases by Gkourogianni et al. [2017] were reported to have macrocephaly. Our patient and his father also had macrocephaly (95th percentile) in line with the literature. Until now, ptosis was reported in only 1 case. This 15-year-old patient had ptosis, but his father, who carried the same variant, had not [Kim et al., 2020]. In this study, we report the second case with ptosis in the literature. Our patient had unilateral (right) ptosis of unknown etiology. In addition, it was observed that the phenotypically similar sister of the patient also had ptosis, but no other family members. Therefore, we think that the finding of ptosis may not be associated with the disease or may be a rare finding of the disease that regresses in adulthood. Brachydactyly is found in a significant portion of cases [Gkourogianni et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Mancioppi et al., 2021]. However, our patient and his father did not have brachydactyly.

Stattin et al. [2010] reported 19 affected individuals from a total of 53 family members in 5 generations with familial osteochondritis dissecans with dominant inheritance. They identified the V2330M variant in the C-type lectin domain associated with the G3 domain of aggrecan in these individuals. In a comprehensive cohort study in which 103 short stature cases with mutations in the ACAN gene were evaluated, 19 different variants were reported. The p.(Glu415*) variant in our patient is shown for the first time in 9 cases from different generations of a family in this study. Early-onset osteoarthritis was present in 12 different families, including the family with the p.(Glu415*) variant. The most common symptom was knee pain, which was reported to start in late adolescence and to affect individuals in varying degrees even within the same family. The same study reported that intervertebral disc disease or suspicious symptoms started in the 4th and 5th decades [Gkourogianni et al., 2017]. Unlike what was observed in our patient and his father, there was no clinical finding indicative of osteochondritis dissecans. Our patient's father had a history of operation due to intervertebral disc herniation. Thus, this suggests that different mutations might have similar effects on height and that there is no significant genotype/phenotype correlation for osteoarthritis, in which additional genetic and environmental factors may be the cause.

Advanced bone age and premature growth arrest are found in a significant proportion of patients with ACAN gene mutations. In these patients, the initial goal is to pause the progression of bone age and to prevent early fusion of epiphyseal plates. Gkourogianni et al. [2017] demonstrated that there was a significant increase in the annual growth rate of 14 pediatric patients after GH treatment. In addition, it was reported that adults who received GH therapy had a significant increase in final height compared to adults who did not receive treatment. A different study also reported that there was a significant increase in SDS values of pediatric patients who received GH treatment for 1 year [Stavber et al., 2020]. There was also a significant increase in adult height in some cases who received GnRH analog and GH combination therapy [van der Steen et al., 2017]. Our patient, on the other hand, has not received any treatment yet and is being followed up clinically.

As a result, ACAN gene mutation should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with short stature, dominantly inherited frontal bossing, midface hypoplasia, and brachydactyly. Although the incidence of macrocephaly is low, it is among the expected findings. Our patient is the second case with ptosis. It is promising that a limited number of patients receiving GH and/or combination therapy before puberty have a final height-prolonging response. However, it is important to evaluate the data of larger series and to perform long-term follow-ups for these patients.

Statement of Ethics

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects have given their written informed consent to publish their case (including publication of images). Clinical exome sequencing including 4,490 genes was performed on the patient upon receiving informed consent from his parents. Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with local/national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The research conducted in this study was not supported by any grant.

Author Contributions

Emine Karatas, Mikail Demir, Munis Dundar, and Leyla Kara conceived and planned the experiments. Firat Ozcelik, Emine Karatas, and Esra Akyurek carried out the experiments. Emine Karatas, Mikail Demir, Firat Ozcelik, Leyla Kara, Esra Akyurek, Ugur Berber, Nihal Hatipoglu, Yusuf Ozkul, and Munis Dundar contributed to the interpretation of the results. Emine Karatas took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding Statement

The research conducted in this study was not supported by any grant.

References

- 1.Dateki S. ACAN mutations as a cause of familial short stature. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;26((3)):119–125. doi: 10.1297/cpe.26.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dateki S, Nakatomi A, Watanabe S, Shimizu H, Inoue Y, Baba H, et al. Identification of a novel heterozygous mutation of the Aggrecan gene in a family with idiopathic short stature and multiple intervertebral disc herniation. J Hum Genet. 2017;62((7)):717–721. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gkourogianni A, Andrew M, Tyzinski L, Crocker M, Douglas J, Dunbar N, et al. Clinical Characterization of Patients with Autosomal Dominant Short Stature due to Aggrecan Mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102((2)):460–469. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gleghorn L, Ramesar R, Beighton P, Wallis G. A mutation in the variable repeat region of the aggrecan gene (AGC1) causes a form of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia associated with severe, premature osteoarthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77((3)):484–490. doi: 10.1086/444401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TY, Jang KM, Keum CW, Oh SH, Chung WY. Identification of a heterozygous ACAN mutation in a 15-year-old boy with short stature who presented with advanced bone age: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;25((4)):272–276. doi: 10.6065/apem.1938198.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancioppi V, Prodam F, Mellone S, Ricotti R, Giglione E, Grasso N, et al. Retrospective Diagnosis of a Novel ACAN Pathogenic Variant in a Family with Short Stature: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Front Genet. 2021;12:708864. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.708864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neyzi O, Bundak R, Gökçay G, Günöz H, Furman A, Darendeliler F, et al. Reference values for weight, height, head circumference, and body mass index in Turkish children. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015;7((4)):280–293. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson O, Guo MH, Dunbar N, Popovic J, Flynn D, Jacobsen C, et al. Short stature, accelerated bone maturation, and early growth cessation due to heterozygous aggrecan mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99((8)):E1510–18. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintos JB, Guo MH, Dauber A. Idiopathic short stature due to novel heterozygous mutation of the aggrecan gene. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28((7-8)):927–932. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2014-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sentchordi-Montané L, Aza-Carmona M, Benito-Sanz S, Barreda-Bonis AC, Sánchez-Garre C, Prieto-Matos P, et al. Heterozygous aggrecan variants are associated with short stature and brachydactyly: Description of 16 probands and a review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;88((6)):820–829. doi: 10.1111/cen.13581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stattin EL, Tegner Y, Domellöf M, Dahl N. Familial osteochondritis dissecans associated with early osteoarthritis and disproportionate short stature. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16((8)):890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stattin EL, Wiklund F, Lindblom K, Onnerfjord P, Jonsson BA, Tegner Y, et al. A missense mutation in the aggrecan C-type lectin domain disrupts extracellular matrix interactions and causes dominant familial osteochondritis dissecans. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86((2)):126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stavber L, Hovnik T, Kotnik P, Lovrečić L, Kovač J, Tesovnik T, et al. High frequency of pathogenic ACAN variants including an intragenic deletion in selected individuals with short stature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182((3)):243–253. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatsi C, Gkourogianni A, Mohnike K, DeArment D, Witchel S, Andrade AC, et al. Aggrecan Mutations in Nonfamilial Short Stature and Short Stature Without Accelerated Skeletal Maturation. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1((8)):1006–1011. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tompson SW, Merriman B, Funari VA, Fresquet M, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, et al. A recessive skeletal dysplasia, SEMD aggrecan type, results from a missense mutation affecting the C-type lectin domain of aggrecan. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84((1)):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turan S, Bereket A, Omar A, Berber M, Ozen A, Bekiroglu N. Upper segment/lower segment ratio and armspan–height difference in healthy Turkish children. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94((4)):407–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchida N, Shibata H, Nishimura G, Hasegawa T. A novel mutation in the ACAN gene in a family with autosomal dominant short stature and intervertebral disc disease. Hum Genome Var. 2020;7((1)):44. doi: 10.1038/s41439-020-00132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Steen M, Pfundt R, Maas SJWH, Bakker-van Waarde WM, Odink RJ, Hokken-Koelega ACS. ACAN Gene Mutations in Short Children Born SGA and Response to Growth Hormone Treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102((5)):1458–1467. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.