Abstract

Purpose

To compare the accuracy of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI), 68Ga-PSMA PET and the Briganti 2019 nomogram in the prediction of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes (PLN) in prostate cancer, to assess the accuracy of mpMRI and the Briganti nomogram in prediction of PET positive PLN and to investigate the added value of quantitative mpMRI parameters to the Briganti nomogram.

Method

This retrospective IRB-approved study included 41 patients with prostate cancer undergoing mpMRI and 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT or MR prior to prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection. A board-certified radiologist assessed the index lesion on diffusion-weighted (Apparent Diffusion Coefficient, ADC; mean/volume), T2-weighted (capsular contact length, lesion volume/maximal diameters) and contrast-enhanced (iAUC, kep, Ktrans, ve) sequences. The probability for metastatic pelvic lymph nodes was calculated using the Briganti 2019 nomogram. PET examinations were evaluated by two board-certified nuclear medicine physicians.

Results

The Briganti 2019 nomogram performed superiorly (AUC: 0.89) compared to quantitative mpMRI parameters (AUCs: 0.47–0.73) and 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET (AUC: 0.82) in the prediction of PLN metastases and superiorly (AUC: 0.77) in the prediction of PSMA PET positive PLN compared to MRI parameters (AUCs: 0.49–0.73). The addition of mean ADC and ADC volume from mpMRI improved the Briganti model by a fraction of new information of 0.21.

Conclusions

The Briganti 2019 nomogram performed superiorly in the prediction of metastatic and PSMA PET positive PLN, but the addition of parameters from mpMRI can further improve its accuracy. The combined model could be used to stratify patients requiring ePLND or PSMA PET.

Keywords: Multiparametric MRI, Prostate cancer, PSMA, PET imaging, Pelvic lymph nodes

1. Introduction

While most prostate cancer patients present in early stages with localized disease, about 14 % of patients are found to have metastases in regional pelvic lymph nodes at presentation, which is a poor prognostic factor for local recurrence after radical prostatectomy [1], [2]. Abdominal CT or MRI may be used to detect cancerous lymph nodes in patients with high-risk features. However, conventional imaging only identifies suspiciously enlarged lymph nodes and relies on size (≥ 8–10 mm) as the sole criterion for malignancy. As small metastatic lymph node metastases are common in the pelvis, the sensitivity of standard cross-sectional imaging is low [3], [4]. PSMA-PET has been approved in some countries for primary staging of prostate cancer, but recent studies, including a large multi-centric study with patients undergoing prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection demonstrated a sensitivity of only 40% in detection of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes when using histopathology as a standard-of-reference [5], [6].

Several clinical nomograms have been developed to predict the presence of pelvic lymph node metastases and further stratify patients [7], [8], [9]. Most notably, the Briganti 2019 nomogram combines clinical data (i.e., Gleason score, PSA level, percentage of cores with clinically significant prostate cancer) with data from pre-biopsy multiparametric MRI (mpMRI, i.e., clinical stage, size of the target lesion) [10]. However, this approach only includes the data provided by standard ‘anatomical sequences’ of mpMRI (e.g., size of a lesion on standard T2-weighted imaging), while easily accessible quantitative data (e.g., from diffusion-weighted imaging) are not incorporated.

Though clinical nomograms are helpful in assessing the risk for pelvic lymph node metastases [11], PSMA PET offers additional value for localization of metastatic lymph nodes. However, access to PSMA PET is costly and not ubiquitous: therefore, the correct identification of prostate cancer patients with metastatic pelvic lymph nodes on histopathology or PSMA PET is crucial, as it impacts therapy stratification as well as the cost-effective use of 68Ga- PSMA PET.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was (1) to compare the accuracy of mpMRI parameters, 68Ga- PSMA PET and the Briganti 2019 nomogram in the prediction of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer with histopathology as standard of reference, (2) to assess the accuracy of mpMRI parameters and the Briganti 2019 nomogram in prediction of PET positive pelvic lymph nodes on 68Ga- PSMA PET and (3) to investigate the added value of quantitative parameters of mpMRI to the Briganti 2019 nomogram to predict metastatic pelvic lymph nodes on histopathology and 68Ga- PSMA PET.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and patients

This study was approved by the institutional review board and the requirement for study-specific informed consent was waived. General informed consent to use clinical and imaging data for research was available in all patients. A retrospective search was performed (01/2016 – 02/2019) to identify patients undergoing 68Ga-PSMA-11-PET/MRI (n = 35) or 68Ga-PSMA-PET/CT (n = 6) and mpMRI prior to MRI-guided TRUS-based biopsy for primary staging of prostate cancer within < 6 months and who subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy with regional lymph node dissection. Of note, the decision to perform PET imaging in these patients was not based on the Briganti 2019 model, but rather on overall clinical assessment in multidisciplinary team meetings. Clinical information (e.g., age, PSA, clinical stage etc.) were collected through the in-house clinical information system. Histopathological data (e.g., Gleason score, percentage of cores with clinically significant prostate cancer, presence of pelvic lymph node metastases) were gathered from the pathological reports.

2.2. Multiparametric MRI and 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET

All multiparametric MRI examinations were performed on clinical MRI scanners (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) at a field strength of 3 Tesla with a pelvic phased-array surface coil and included high-resolution T2- weighted in three orientations, diffusion weighted- imaging (b-values of 100, 600 and 1000 s/mm² and calculated b-value of 1400 s/mm²) and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with injection of gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem, Guerbet, Villepinte, France) as a contrast agent (dose of 0.1 mmol/kg body weight). The MRI protocol was compliant with current PI-RADS guidelines [12].

68Ga-PSMA-11 PET examinations were performed on a 3 T hybrid scanner (SIGNA PET/MR, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA) or a hybrid PET/CT scanner (Discovery MI PET/CT, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA), 60 min after injection of a 68Ga- labeled Glu-urea-Lys (Ahx)-HBED-CC (i.e., PSMA-11) ligand targeting the prostate-specific membrane antigen. PET emission data were reconstructed using an iterative algorithm (ordered subset expectation maximization based VUE Point FX, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA) and six bed positions were acquired from head to mid-thigh. The accompanying MRI protocol included a T1-weighted fat saturated gradient echo sequence covering head to mid-thigh before and after contrast agent injection (gadoterate meglumine, Dotarem, Guerbet, Villepinte, France) in a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg body weight. PET acquisitions were performed in accordance with current guidelines [13].

2.3. Image analysis

All analyses were performed on anonymized examinations and all readers were blinded to clinical data and patient information.

PET examinations were read by two board-certified radiologists/nuclear medicine physicians IB and MH (blinded for review) with 9 and 13 years of experience in urogenital imaging, who rated the probability of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes on a Likert-like scale (1: not present, 2: unlikely, 3: unclear, 4: likely, 5: present). The results of both readers were combined as a consensus reading using the highest rating per patient.

A third reader with four years of experience in radiology SBK (blinded for review) additionally identified the index lesion on every mpMRI scan and measured the following parameters: (1) Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC, mean) on diffusion-weighted imaging, (2) volume of the lesion on the ADC map, (3) parameters of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI by applying the Tofts model (kep, Ktrans, iAUC, ve), (4) Lengths of capsular contact (mm), maximal diameter, orthogonal short axis diameter and volume of the index lesion on T2-weighted imaging.

Data from MR analysis (maximal tumor diameter on T2-weighted imaging) and clinical data (PSA level, clinical stage at mpMRI, Gleason score and percentage of cores with clinically significant prostate cancer) were then used to calculate the probability of the presence of pelvic lymph node metastases (N1 stage) using the Briganti 2019 nomogram [10].

2.4. Statistical analysis

The patient characteristics were summarized using the mean, median, standard deviation, and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Discrimination ability was assessed using receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis and accuracy was measured using area under the curve (AUC). To calculate sensitivity and specificity the Youden method was used for mpMRI parameters, a cut-off of LNI rating of ≥ 3 was used as a cut-off for PSMA PET positivity and a cut-off of 7% for the Briganti 2019 nomogram, respectively [10]. The added value of the quantitative mpMRI parameters to the Briganti 2019 nomogram was assessed using multivariable logistic regression. Nested logistic regression models were compared using the likelihood ratio X² test. Moreover, we determined the value of including the mpMRI parameters to the model by calculating the fraction of new information provided, which equals one minus the ratio of the variance of pre-test probability of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes to the variance of post-test probability of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes [14].

A 2-tailed p-value of < 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance. We performed all statistical analysis in R version 4.0.5 (R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

This study included 41 patients undergoing 68Ga- PSMA PET/MR or CT and subsequently radical prostatectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection. All patients also underwent pre-biopsy multiparametric MRI. In 6 patients, no dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI sequences were acquired.

On histopathological analysis, 11 patients (27%) had metastatic pelvic lymph nodes while PET imaging deemed 7 patients (17%) to have positive lymph nodes.

Additional information on the patients and tumors included in this study can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics (1median (interquartile range), 2mean (standard deviation), Gleason score 7a = 3 + 4, Gleason score 7b = 4 + 3).

| Age (years)1 | 65 (9) |

|---|---|

| Highest PI-RADS score on mpMRI | |

| 3 | 5 |

| 4 | 21 |

| 5 | 15 |

| LNI rating on68Ga-PSMA-11 PSMA PET (consensus) | |

| 1 | 34 |

| 2 | - |

| 3 | - |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 4 |

| Gleason score at biopsy | |

| 7a | 5 |

| 7b | 10 |

| 8 | 19 |

| 9 | 7 |

| WHO/ISPU grade groups at biopsy | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 4 | 19 |

| 5 | 7 |

| D′Amico classification | |

| Intermediate | 12 |

| High | 29 |

| Tumor stage on prostatectomy | |

| 1c | 1 |

| 2a | 1 |

| 2b | 1 |

| 2c | 23 |

| 3a | 10 |

| 3b | 4 |

| 4 | 1 |

| Lymph node involvement on ePLND | |

| Positive | 11 |

| Negative | 30 |

| Time between mpMRI and68Ga-PSMA-PET (months)2 | 2.3 (1.3) |

3.2. Accuracy of mpMRI parameters, PSMA PET and Briganti 2019 nomogram in predicting histopathological N + status

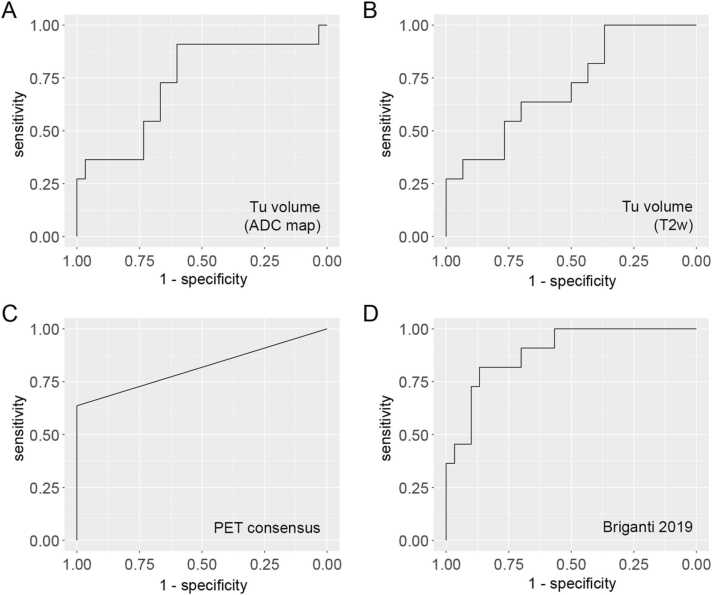

Assessment of the tumor volume on the ADC map (AUC: 0.73, 95%-CI: 0.54 – 0.92) or T2-weighted sequences (AUC: 0.71, 95%-CI: 0.53 – 0.89) and qualitative readings of PSMA PET (Reader 1; AUC: 0.73, 95%-CI: 0.57 – 0.88 / Reader 2; AUC: 0.77, 95%-CI: 0.62 – 0.93 / Consensus; AUC: 0.82, 95%- CI: 0.67 – 0.97) performed comparably in the prediction of metastatic lymph nodes with histopathology as standard-of-reference, with a consensus reading of PSMA PET performing best. Using the Briganti 2019 nomogram (which includes the parameter maximal tumor length on T2-weighted sequences) a further improvement with an AUC of 0.89 (95%-CI: 0.79 – 1.00) was achieved (see Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Added value of quantitative MRI parameters to the Briganti 2019 nomogram.

| N + on histopathology |

N + on68Ga- PSMA-PET |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔX² | p-value | ΔX² | p-value | |

| Briganti 2019 parameters vs. | ||||

| Briganti + Tumor volume on ADC map | 2.22 | 0.14 | 19.22 | 0.12 |

| Briganti + ADC (mean) | 1.65 | 0.2 | 20.34 | 0.06 |

| Briganti + Tumor Volume on ADC map + ADC (mean) | 6.72 | 0.03 | 30.11 | 0.001 |

Table 2.

Area-under-the-Curve analysis (AUC, CI = confidence intervals) for the accuracy of mpMRI parameters, qualitative readings of 68Ga- PSMA PET (for both readers and as a consensus) and the Briganti 2019 nomogram (7% cut-off) in the prediction of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes with histopathology as the reference standard and PSMA PET positive lymph nodes on 68Ga- PSMA PET (consensus).

| N + on histopathology |

N + on68Ga- PSMA PET |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC, 95%- CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC, 95%- CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||

| MRI parameters | |||||||

| ADC (mean) | 0.58 (0.39 – 0.78) | 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.73 (0.55 – 0.91) | 1.00 | 0.50 | |

| Ktrans | 0.59 (0.38 – 0.79) | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.67 (0.43 – 0.90) | 0.83 | 0.66 | |

| kep | 0.59 (0.39 – 0.78) | 0.89 | 0.46 | 0.71 (0.55 – 0.88) | 1.00 | 0.59 | |

| ve | 0.47 (0.26 – 0.68) | 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.64 (0.42 – 0.86) | 1.00 | 0.48 | |

| iAUC | 0.48 (0.25 – 0.71) | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.49 (0.20 – 0.78) | 0.67 | 0.66 | |

| Tumor diameter (max., T2w) | 0.73 (0.55 – 0.91) | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.62 (0.41 – 0.84) | 0.86 | 0.47 | |

| Tumor diameter (perpend., T2w) | 0.66 (0.45 – 0.86) | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.51 (0.29 – 0.74) | 0.71 | 0.56 | |

| Tumor capsular contact (T2w) | 0.73 (0.54 – 0.92) | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.62 (0.40 – 0.84) | 0.86 | 0.62 | |

| Tumor volume on ADC map | 0.73 (0.54 – 0.92) | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.58 (0.35 – 0.81) | 0.86 | 0.56 | |

| Tumor volume on T2w | 0.71 (0.53 – 0.89) | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.59 (0.40 – 0.78) | 1.00 | 0.32 | |

| PSMA PET | |||||||

| 68Ga- PSMA PET (Reader 1) | 0.73 (0.57 – 0.88) | 0.46 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 68Ga- PSMA PET (Reader 2) | 0.77 (0.62 – 0.93) | 0.55 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 68Ga- PSMA PET (consensus) | 0.82 (0.67 – 0.97) | 0.64 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Clinical nomogram | |||||||

| Briganti 2019 | 0.89 (0.79 – 1.00) | 1.00 | 0.27 | 0.77 (0.61 – 0.93) | 1.00 | 0.24 | |

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for best-performing quantitative MRI parameters, 68Ga-PSMA PET and the Briganti 2019 nomogram in the prediction of N + status on histopathology.

Applying a cut-off of 7% to the Briganti model, 8 patients (19.5%) would have been spared an unnecessary PNLD and none of the node-positive patients on histopathology would have been missed.

3.3. Accuracy of mpMRI parameters and Briganti 2019 nomogram in predicting PSMA PET positive pelvic lymph nodes

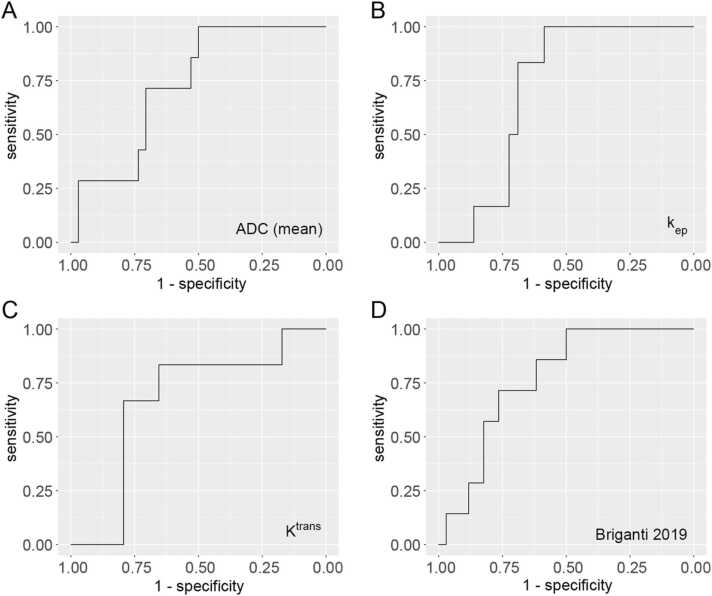

When using quantitative parameters of mpMRI to predict PET positive pelvic lymph nodes, mean ADC performed best, reaching an AUC of 0.73 (95%-CI: 0.55 – 0.91), followed by kep (AUC = 0.71, 95%-CI: 0.55 – 0.88) and Ktrans (AUC = 0.67, 95%-CI: 0.4 – 0.84), see Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for best-performing quantitative MRI parameters and the Briganti 2019 nomogram in the prediction of N + status on 68Ga-PSMA PET.

The Briganti 2019 nomogram performed slightly better in predicting PET positive pelvic lymph nodes, with an AUC of 0.77 (95%-CI: 0.61 – 0.93). Applying the 7% cut-off used to predict histopathologically proven pelvic lymph node metastases to this context of predicting PET positive pelvic lymph nodes, 8 (19.5%) patients would have been spared an unnecessary PSMA PET with no PET positive pelvic lymph nodes missed.

3.4. Added value of quantitative MR parameters to the Briganti 2019 nomogram

When adding tumor volume of the index lesion on the ADC map and mean ADC value to the Briganti 2019 nomogram, performance improved for both prediction of histopathological positive lymph nodes (ΔX² = 6.72, p = 0.03) as well as PET positive lymph nodes (ΔX² = 30.11, p = 0.01). The combined model reached an AUC of 0.72 in the prediction of N + status on histopathology and an AUC of 0.72 when predicting PET positive lymph nodes. The fraction of new information provided by index lesion volume on ADC map and mean ADC value was 0.21.

4. Discussion

In patients with prostate cancer, extended pelvic lymph node dissection (ePNLD) is routinely performed if preoperative clinical nomograms suggest intermediate or high risk for pelvic lymph node metastases [15]. However, since the actual rate of positive lymph nodes on subsequent histopathology is low and a large fraction of up to 70% of patients undergo PLND without need [10], [16], efforts have been made to better identify those patients with pelvic lymph node metastases prior to surgery using nomograms. The majority of these nomograms rely on clinical information, as standard cross-sectional imaging offers poor diagnostic accuracy due to the inability to detect small lymph node metastases in normal-sized lymph nodes [3], [7], [8]. Only the Briganti 2019 nomogram incorporates a single quantitative parameter derived from imaging (maximum index lesion diameter on pre-biopsy multiparametric MRI on T2-weighted imaging) into analysis, allowing to spare 60% of patients from ePLND while missing only 1.6% of patients with positive lymph nodes [7], [8], [10]. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron-emission tomography (PET) has seen increased adoption for patients with high-risk disease, as the added metabolic information may detect metastases even in smaller lymph nodes not deemed suspicious on standard cross-sectional imaging. However, a recent multi-centric study only demonstrated a sensitivity of 40% for this modality when using histopathology as a standard of reference [5]. Furthermore, PET imaging is costly and not available everywhere. Multiparametric MRI of the prostate before biopsy is standard of care in patients with suspected prostate cancer and the quantitative data that can be gathered from this MRI examination is known to offer insights into, for example, tumor aggressiveness with ADC values or perfusion parameters correlating with Gleason score [17]. We therefore hypothesized that the addition of this data to the Briganti 2019 nomogram might further improve its ability to stratify patients for ePLND and PET imaging.

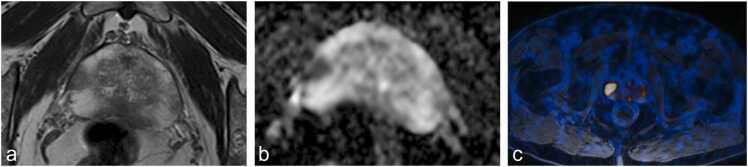

When assessing the ability of mpMRI parameters and PET imaging in predicting pelvic lymph node metastases, we found tumor volume measurements (on the ADC map or T2-weighted imaging) to perform well, but perfusion measures and ADC mean did not. This aligns well with the results of Park et al. in a similar study, who found that only preoperative T stage on MR imaging predicted the presence of micrometastases, but other MR parameters – amongst them ADC - did not [18]. Brembilla et al. reported comparable results with a model composed of PSA values, primary Gleason grade, T stage and tumor volume on MRI showing high predictive accuracy [19]. In our study, PET imaging achieved higher AUCs and very high specificity, but demonstrated poor sensitivity. The Briganti 2019 nomogram - which includes clinical parameters as well as the length of the target lesion on T2-weighted sequences of mpMRI - was superior in predicting pelvic lymph node metastases when compared to mpMRI parameters or PSMA PET alone. Using the Briganti 2019 nomogram in this clinical context would be very cost-effective, as it relies on information commonly collected as part of routine assessments in patients with suspected prostate cancer (see Fig. 3). As mpMRI is routinely performed in all patients with suspected prostate cancer, no additional imaging and in particular, no costly PET imaging, would be necessary. However, if PET is performed in patients with a high risk for metastatic spread to organs or bones or when localization of suspicious lymph nodes is necessary, it would be desirable to identify those patients in whom PET positive lymph nodes are likely to be found. For this distinction, we found the mean ADC value of the target lesion to perform better than perfusion parameters – however, the Briganti 2019 nomogram again performed slightly better than both MR parameters and PET imaging.

Fig. 3.

73-year-old patient with histopathologically proven prostate cancer (Gleason Score 4 + 5) and pelvic lymph node metastases in histopathological work-up after radical prostatectomy. (a) T2- weighted sequence showing a hypointense lesion in the right midglandular peripheral zone, (b) corresponding ADC map showing marked diffusions restriction and (c) 68Ga-PSMA PET/MR with avid tracer uptake in the lesion but now sign of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes. The Briganti 2019 nomogram correctly predicted the presence of lymph node metastases in this patient.

The prediction of histopathologically proven pelvic lymph node metastases and PET positive lymph nodes improved by combining mpMRI parameters (ADC tumor volume and ADC mean of the largest target lesion) and the Briganti 2019 nomogram. The addition of these parameters to the Briganti 2019 nomogram, which only features clinical and “anatomical” information, further refines its tumor assessment, and enhances discriminability. There is also evidence that the use of ferumoxtran-10-enhanced MRI can further increase detection rates of even small lymph node metastases and therefore has the potential to significantly improve lymph node metastases detection in prostate cancer [20], [21], [22]. Future studies are needed to investigate the incremental and complementary value of all available imaging modalities as an addition to clinical nomograms.

Our study has limitations: Though we included 41 patients into this trial, the number of patients with lymph node metastases/PET-positive lymph nodes was still small, limiting further analysis. However, as mpMRI is part of clinical routine in prostate cancer (and as such available in most patients) and the role of PET imaging is currently being investigated in several multi-centric trials, the data needed to evaluate a model combining the Briganti 2019 approach with functional data from pre-biopsy diffusions-weighted imaging seems easily accessible in the future. Second, there is an inherent inclusion bias, as only patients who underwent PSMA PET imaging were included. However, the decision to undergo PSMA PET imaging was based on overall clinical assessment in multidisciplinary team meetings and was not based on the Briganti 2019 nomogram.

In conclusion, we found the Briganti 2019 nomogram, incorporating clinical data and information from pre-biopsy multiparametric MRI, to perform superiorly compared to quantitative mpMRI parameters and 68Ga-PSMA PET in the prediction of pelvic lymph node metastases in patients with prostate cancer. The Briganti 2019 nomogram also performed well in identifying those patients likely to demonstrate PET positive lymph node metastases, thus possibly allowing for improved stratification and cost-effective use of 68Ga-PSMA PET. Furthermore, the Briganti model can be improved further by adding functional information from diffusion-weighted imaging, further refining its predictive discriminability, and potentially serving as a stratification tool for patients undergoing ePLND or PET imaging.

Ethical approval details

This study was approved by the institutional review board and the requirement for study-specific informed consent was waived.

Funding sources

No external funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization, Hötker, Mühlematter, Donati; Methodology, Hötker, Mühlematter, Donati; Software, N/A; Validation, Mühlematter; Formal analysis, Mühlematter; Investigation, Hötker, Mühlematter, Donati; Resources, Donati; Data Curation, Mühlematter; Writing - Original Draft, Hötker, Donati; Writing - Review & Editing, all authors; Visualization, N/A; Supervision, Donati; Project administration, Donati; Funding acquisition, N/A.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2023.100487.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Bianco JR F.J., Scardino P.T., Eastham J.A. Radical prostatectomy: long-term cancer control and recovery of sexual and urinary function ("trifecta") Urology. 2005;66:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdollah F., Suardi N., Gallina A., Bianchi M., Tutolo M., Passoni N., Fossati N., Sun M., dell'Oglio P., Salonia A., Karakiewicz P.I., Rigatti P., Montorsi F., Briganti A. Extended pelvic lymph node dissection in prostate cancer: a 20-year audit in a single center. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24:1459–1466. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hövels A.M., Heesakkers R.A.M., Adang E.M., Jager G.J., Strum S., Hoogeveen Y.L., Severens J.L., Barentsz J.O. The diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI in the staging of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin. Radiol. 2008;63:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briganti A., Abdollah F., Nini A., Suardi N., Gallina A., Capitanio U., Bianchi M., Tutolo M., Passoni N.M., Salonia A., Colombo R., Freschi M., Rigatti P., Montorsi F. Performance characteristics of computed tomography in detecting lymph node metastases in contemporary patients with prostate cancer treated with extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Eur. Urol. 2012;61:1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hope T.A., Eiber M., Armstrong W.R., Juarez R., Murthy V., Lawhn-Heath C., Behr S.C., Zhang L., Barbato F., Ceci F., Farolfi A., Schwarzenböck S.M., Unterrainer M., Zacho H.D., Nguyen H.G., Cooperberg M.R., Carroll P.R., Reiter R.E., Holden S., Herrmann K., Zhu S., Fendler W.P., Czernin J., Calais J. Diagnostic accuracy of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET for pelvic nodal metastasis detection prior to radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection: a multicenter prospective phase 3 imaging trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1635–1642. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skawran S.M., Sanchez V., Ghafoor S., Hötker A.M., Burger I.A., Huellner M.W., Eberli D., Donati O.F. Primary staging in patients with intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer: multiparametric MRI and (68)Ga-PSMA-PET/MRI - What is the value of quantitative data from multiparametric MRI alone or in conjunction with clinical information? Eur. J. Radiol. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.110044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandini M., Marchioni M., Pompe R.S., Tian Z., Gandaglia G., Fossati N., Abdollah F., Graefen M., Montorsi F., Saad F., Shariat S.F., Briganti A., Karakiewicz P.I. First North American validation and head-to-head comparison of four preoperative nomograms for prediction of lymph node invasion before radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018;121:592–599. doi: 10.1111/bju.14074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooperberg M.R., Pasta D.J., Elkin E.P., Litwin M.S., Latini D.M., Du Chane J., Carroll P.R. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 2005;173:1938–1942. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 〈https://www.mskcc.org/nomograms/prostate/pre-op〉 (accessed 13 December 2021).

- 10.Gandaglia G., Ploussard G., Valerio M., Mattei A., Fiori C., Fossati N., Stabile A., Beauval J.-B., Malavaud B., Roumiguié M., Robesti D., Dell’Oglio P., Moschini M., Zamboni S., Rakauskas A., de Cobelli F., Porpiglia F., Montorsi F., Briganti A. A novel nomogram to identify candidates for extended pelvic lymph node dissection among patients with clinically localized prostate cancer diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging-targeted and systematic biopsies. Eur. Urol. 2019;75:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukagawa E., Yamamoto S., Ohde S., Yoshitomi K.K., Hamada K., Yoneoka Y., Fujiwara M., Fujiwara R., Oguchi T., Komai Y., Numao N., Yuasa T., Fukui I., Yonese J. External validation of the Briganti 2019 nomogram to identify candidates for extended pelvic lymph node dissection among patients with high-risk clinically localized prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;26:1736–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-01954-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turkbey B., Rosenkrantz A.B., Haider M.A., Padhani A.R., Villeirs G., Macura K.J., Tempany C.M., Choyke P.L., Cornud F., Margolis D.J., Thoeny H.C., Verma S., Barentsz J., Weinreb J.C. Prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2.1: 2019 update of prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2. Eur. Urol. 2019;76:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fendler W.P., Eiber M., Beheshti M., Bomanji J., Ceci F., Cho S., Giesel F., Haberkorn U., Hope T.A., Kopka K., Krause B.J., Mottaghy F.M., Schöder H., Sunderland J., Wan S., Wester H.-J., Fanti S., Herrmann K. 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT: joint EANM and SNMMI procedure guideline for prostate cancer imaging: version 1.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2017;44:1014–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3670-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell F.E. Jr, Statistically Efficient Ways to Quantify Added Predictive Value of New Measurements. 〈https://www.fharrell.com/post/addvalue/〉.

- 15.Cagiannos I., Karakiewicz P., Eastham J.A., Ohori M., Rabbani F., Gerigk C., Reuter V., Graefen M., Hammerer P.G., Erbersdobler A., Huland H., Kupelian P., Klein E., Quinn D.I., Henshall S.M., Grygiel J.J., Sutherland R.L., Stricker P.D., Morash C.G., Scardino P.T., Kattan M.W. A preoperative nomogram identifying decreased risk of positive pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2003;170:1798–1803. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091805.98960.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierorazio P.M., Gorin M.A., Ross A.E., Feng Z., Trock B.J., Schaeffer E.M., Han M., Epstein J.I., Partin A.W., Walsh P.C., Bivalacqua T.J. Pathological and oncologic outcomes for men with positive lymph nodes at radical prostatectomy: the Johns Hopkins Hospital 30-year experience. Prostate. 2013;73:1673–1680. doi: 10.1002/pros.22702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hötker A.M., Mazaheri Y., Aras Ö., Zheng J., Moskowitz C.S., Gondo T., Matsumoto K., Hricak H., Akin O. Assessment of prostate cancer aggressiveness by use of the combination of quantitative DWI and Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2016;206:756–763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S.Y., Oh Y.T., Jung D.C., Cho N.H., Choi Y.D., Rha K.H. Prediction of micrometastasis (< 1 cm) to pelvic lymph nodes in prostate cancer: role of preoperative MRI. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015;205:W328–W334. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brembilla G., Dell'Oglio P., Stabile A., Ambrosi A., Cristel G., Brunetti L., Damascelli A., Freschi M., Esposito A., Briganti A., Montorsi F., Del Maschio A., de Cobelli F. Preoperative multiparametric MRI of the prostate for the prediction of lymph node metastases in prostate cancer patients treated with extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Eur. Radiol. 2018;28:1969–1976. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schilham M.G.M., Zamecnik P., Privé B.M., Israël B., Rijpkema M., Scheenen T., Barentsz J.O., Nagarajah J., Gotthardt M. Head-to-Head comparison of (68)Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT and ferumoxtran-10-enhanced mri for the diagnosis of lymph node metastases in prostate cancer patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2021;62:1258–1263. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.258541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkhäuser F.D., Studer U.E., Froehlich J.M., Triantafyllou M., Bains L.J., Petralia G., Vermathen P., Fleischmann A., Thoeny H.C. Combined ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide-enhanced and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging facilitates detection of metastases in normal-sized pelvic lymph nodes of patients with bladder and prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2013;64:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heesakkers R.A.M., Jager G.J., Hövels A.M., de Hoop B., van den Bosch, Harrie C.M., Raat F., Witjes J.A., Mulders P.F.A., van der Kaa, Christina Hulsbergen, Barentsz J.O. Prostate cancer: detection of lymph node metastases outside the routine surgical area with ferumoxtran-10-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;251:408–414. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512071018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material