Abstract

Background

With an increasing burden of stroke and a lack of access to rehabilitation services in rural South African settings, stroke survivors rely on untrained family caregivers for support and care. Community health workers (CHWs) support these families but have no stroke-specific training.

Objectives

To describe the development of a contextually appropriate stroke training program for CHWs in the Cape Winelands District, South Africa.

Method

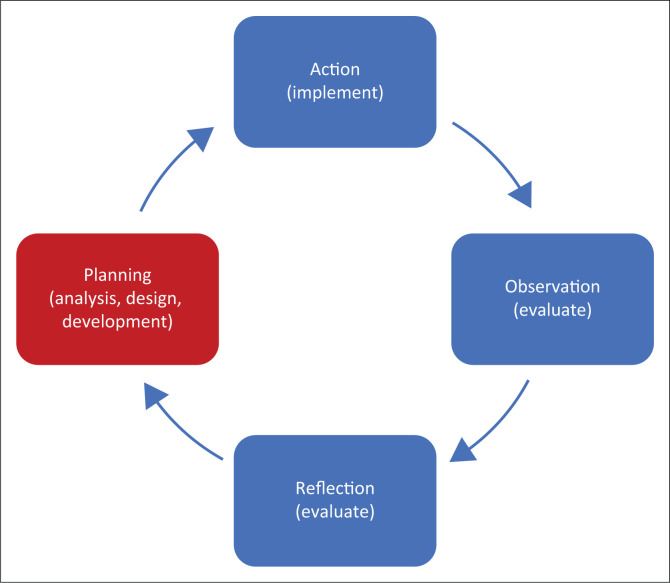

Twenty-six health professionals and CHWs from the local primary healthcare services participated in action research over a 15-month period from September 2014 to December 2015. The groups participated in two parallel cooperative inquiry (CI) groups. The inquiry followed the cyclical steps of planning, action, observation and reflection. In this article, the planning step and how the CI groups used the first three steps of the analyse, design, develop, implement, evaluate (ADDIE) instructional design model are described.

Results

The CHWs’ scope of practice, learning needs, competencies and characteristics, as well as the needs of the caregivers and stroke survivors, were identified in the analysis step. The program design consisted of 16 sessions to be delivered over 20 h. Program resources were developed with appropriate technology, language and instructional methodology.

Conclusion

The program aims to equip CHWs to support family caregivers and stroke survivors in their homes as part of their generalist scope of practice. The implementation and initial evaluation will be described in a future article.

Contribution

The study developed a unique training program for CHWs to support caregivers and stroke survivors in a resource-constrained, rural, middle-income country setting.

Keywords: Primary healthcare, family caregiving, stroke rehabilitation, community care, education and training, participative methods

Introduction

South Africa (SA) and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have an increasing burden of stroke as a result of socio-economic development, urbanisation, increasing risk factors for noncommunicable diseases and a transition in the epidemiological profile of the population associated with ageing, increase in cardiovascular diseases and adoption of the Western lifestyle (Donkor 2018; Langhorne et al. 2018; Taylor & Ntusi 2019). While significant functional improvement is possible, around a third of stroke survivors require ongoing care (Jaracz et al. 2015). In rural SA, the incidence and prevalence of stroke are higher than elsewhere recorded in SA or other African countries (Maredza, Bertram & Tollman 2015; The SASPI Project Team 2004), and the lack of access to medical and rehabilitation services increases disability and impairment, with resultant dependence on family caregivers. While family caregiver training is integral to stroke care and rehabilitation in all settings and levels of the health system (Cameron et al. 2016; Lindsay et al. 2014; Pandian et al. 2016; Winstein et al. 2016), the lack of services in rural SA contexts means a lack of caregiver training in these communities.

The local and international literature describes a myriad of caregiver training interventions in different levels of care, different settings and with different caregiver needs and stroke survivor stages of recovery (Aslani et al. 2016; Bakas et al. 2014; Brereton, Carroll & Barnston 2007; Camak 2015; Chaiyawat & Kulkantrakorn 2012; Chaiyawat, Kulkantrakorn & Sritipsukho 2009; Deyhoul et al. 2020; Forster et al. 2013; Hafsteinsdóttir et al. 2011; Krieger, Feron & Dorant 2017; Lutz et al. 2016; Mudzi, Stewart & Musenge 2012; Nordin et al. 2014; Pitthayapong et al. 2017; Robinson et al. 2005; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Smith et al. 2004; Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019). Most evidence, including evidence from SA, comes from stroke survivors who received specialised stroke unit care and/or multidisciplinary rehabilitation services (Aslani et al. 2016; Bakas et al. 2014; Brereton et al. 2007; Camak 2015; Dobe, Gustafsson & Walder 2022; Forster et al. 2013; Hafsteinsdóttir et al. 2011; Krieger et al. 2017, 2021; Lutz et al. 2016; Robinson et al. 2005). There is limited evidence for caregiver training interventions in settings where these services are not available (Deyhoul et al. 2020; Dobe et al. 2022; Krieger et al. 2021; Mudzi et al. 2012; Nordin et al. 2014; Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2019). Despite the volume of evidence on caregiver training, few publications detail the training development process (Forster et al. 2015; Krieger et al. 2017; Robinson et al. 2005). This inadequate description of the development process, particularly the context and instructional design methods, limits the transferability of interventions to low-resourced primary healthcare (PHC) settings. There is also no evidence of caregiver training as a PHC intervention.

South African health policy promotes a PHC approach with a continuum of preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative services. Home- and community-based care (HCBC) are delivered by nurse-led teams of community health workers1 (CHWs) (Naledi, Barron & Schneider 2011; National Department of Health 2018). Rehabilitation services at the PHC level are limited and infrequent (Rhoda, Mpofu & De Weerdt 2009) and often inaccessible because of poverty and a lack of or inaccessible transport (Cawood & Visagie 2016; Eide et al. 2015; Maart et al. 2007; Maart & Jelsma 2014; Visagie & Swartz 2016).

National initiatives to strengthen PHC rehabilitation services include strengthening the role of CHWs, as well as introducing midlevel rehabilitation workers2 (National Planning Commission 2012). However, the latter has not gone to scale, and there is a need to redress the inequitable distribution of rehabilitation services. Stroke caregiver training is congruent with the scope of practice of CHWs (Hartzler et al. 2018). Unfortunately, the national CHW training curriculum contains limited rehabilitation content and only as elective modules (South African Qualifications Authority 2018a, 2018b, 2018c), thus limiting the knowledge of CHWs to support family caregivers.

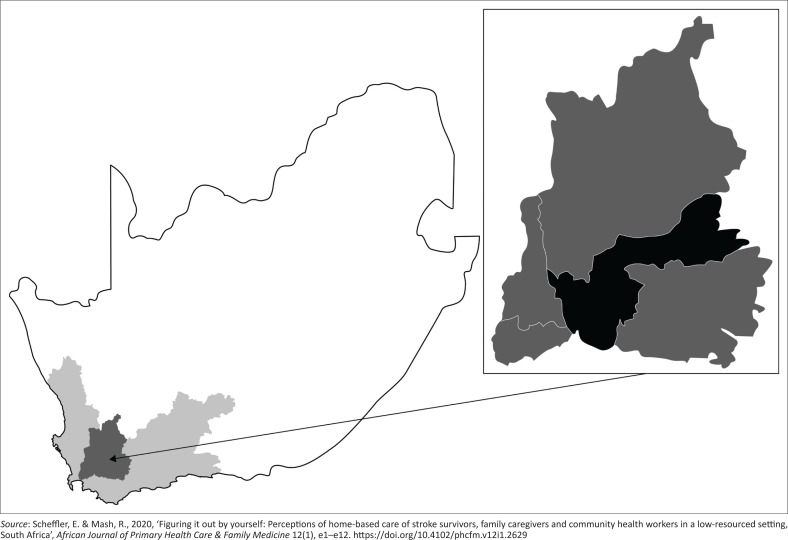

The Western Cape province in SA (Figure 1) has a higher prevalence of stroke compared with national figures (Shisana et al. 2013; Statistics South Africa 2018a). Within its less-resourced rural districts, there are no stroke units or inpatient rehabilitation services. Acute inpatient stays are an average of five days (Scheffler & Mash 2019), and stroke survivors are discharged home to untrained family caregivers, resulting in poor stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes and satisfaction (Scheffler & Mash 2019) and a high caregiver burden (Scheffler & Mash 2020). For these stroke survivors and their family caregivers, CHWs may be their only accessible source of health care and rehabilitation. However, these CHWs have no stroke or rehabilitation-specific training. Because of the lack of rehabilitation service capacity in the district, a community-based services (CBS) manager from the rural Cape Winelands District (Figure 1) requested the researcher’s assistance with the development of a rehabilitation training program for CHWs to train family caregivers of stroke survivors within HCBC services. The district had one multidisciplinary professional rehabilitation team of seven members and no midlevel rehabilitation workers. The researcher, a physiotherapist, had extensive stroke rehabilitation experience in low-resourced settings and with designing and developing training programs for rehabilitation health workers. This article reports on the design and development of a contextually appropriate stroke training program for CHWs within a rural South African PHC context.

FIGURE 1.

Map of South Africa illustrating the Western Cape province (light grey area), with the Cape Winelands district (darker grey area). The insert shows the Breede Valley subdistrict (black).

Research methods and design

This article reports on the last stage of a multistage mixed-methods study (Table 1). The first two convergent stages, a quantitative longitudinal survey (Scheffler & Mash 2019) and a qualitative exploratory descriptive study (Scheffler & Mash 2020), preceded the participatory action research study in stage three.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the multistage study, procedures and results integrated with the steps of the ADDIE model.

| Study stage | Steps of the ADDIE model | Procedures | Products | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Analyse | Longitudinal survey (Scheffler & Mash 2019) |

|

|

| Stage 2 | Analyse | Qualitative descriptive exploratory study (Scheffler & Mash 2020) | Perceived needs of stroke survivors, caregivers, and community health workers | |

| Stage 3 | Analyse | Participatory action research using cooperative inquiry | Planning | Design and develop training program and resources |

| Design | ||||

| Develop | ||||

| Implement | Action | Pilot training program and evaluate outcomes | ||

| Evaluate | Observation | |||

| Reflection | ||||

ADDIE, analyse, design, develop, implement, evaluate.

In this last stage of this multistage mixed-methods study, a cooperative inquiry (CI) process was used (Heron 2014; Higginbottom & Liamputtong 2015; Ramsden et al. 2018). Cooperative inquiry had been used in stroke program and training development (Aslani et al. 2016; Dobe et al. 2022; Krieger et al. 2021). The CI followed the cyclical steps of planning, action, observation and reflection (Table 1). The cyclical steps of the CI were also aligned with the analyse, design, develop, implement, evaluate (ADDIE) (analyse, design, develop, implement, evaluate) instructional design model (Allen 2006; Mayfield 2011) for the development of a training program (Table 1): analyse, design, develop, implement and evaluate.

This article focuses only on the planning step of the CI, which corresponds with the analysis, design and development steps of the ADDIE model (Figure 2). A separate article will report on the remaining steps of the inquiry where the program, per the ADDIE model, was implemented and evaluated.

FIGURE 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the methods. The cycle illustrates the 4 steps of the cooperative inquiry (planning, action, observation and reflection) with the relevant steps of the analyse, design, develop, implement, evaluate model in brackets. This article focuses on the planning step of the cooperative inquiry.

Setting

The study was conducted in the Breede Valley Subdistrict (Figure 1) of the Cape Winelands District in the Western Cape, South Africa. In this rural setting, the majority of the population of 866 000 live in poverty and are dependent on public sector services (Statistics South Africa 2018b). The predominant language in the district is Afrikaans, followed by English and isiXhosa.

Stroke clinical practice pathways, evidence-based practice guidelines, as well as referral guidelines, were absent on the HCBC platform, and stroke care was poorly coordinated (Scheffler & Mash 2019). Stroke survivors were discharged home from acute care to untrained family caregivers. Function and care were limited by numerous environmental barriers such as unavailable or inaccessible services, physical barriers and lack of assistive products (Scheffler & Mash 2019, 2020a). Overall literacy and numeracy of both stroke survivors and caregivers were low, with more than half having no or only primary school education (Scheffler & Mash 2019, 2020a). Knowledge of stroke, rehabilitation, services and assistive products was poor (Scheffler & Mash 2019, 2020a).

Four independent organisations delivered rehabilitation-related services to stroke survivors and their families free of charge:

Seven healthcare professionals, all from different professions, referred to as the multidisciplinary professionals (MDPs) (Table 2) from the Department of Health rotated through the primary care facilities and delivered individual rehabilitation services. Therapists, on request of HCBC services, had previously provided short, informal ad hoc in-service training sessions to CHWs.

Boland Hospice, a nonprofit organisation, was funded by the Department of Health to deliver HCBC services in 10 municipal wards. Four home-based care coordinators, who were professional and enrolled nurses, were responsible for conducting assessments, designing treatment plans and supervising the 79 CHWs (Table 3) delivering home-based care services.

The Breede Valley Association for the Physically Disabled (APD), a nonprofit organisation, provided a range of services for persons with disabilities, including stroke survivors, such as access to education, employment and therapeutic counselling services.

Undergraduate physiotherapy and speech therapy students from Stellenbosch University (SU)’s Rural Clinical School were placed in two of the municipal wards and often accompanied the CHWs. They were supervised by two physiotherapists and a speech therapist from the university.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of multidisciplinary professionals and community health workers in the Breede Valley subdistrict.

| Profession | n |

|---|---|

| Physiotherapists | 1 |

| Occupational therapists | 1 |

| Speech therapists | 1 |

| Social workers | 1 |

| Oral hygienists | 1 |

| Clinical psychologists | 1 |

| Dieticians | 1 |

| Community health workers | 79 |

TABLE 3.

Participant profile of the two cooperative inquiry groups.

| Characteristics | Community-based services CIG |

Multidisciplinary professionals CIG |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community-based service management | Boland Hospice | Association for physically disabled | District | University | |

| Total participants | 3 | 11 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Professions | |||||

| Operational manager | 2† | 1 | 1† | 0 | 0 |

| Nurse (enrolled or professional) | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Social worker | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Occupational therapist | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Physiotherapist | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Oral hygienist | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Speech therapist | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Community health worker | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 0 | 1 | |||

| Female | 18 | 7 | |||

| Age range | |||||

| 20–29 years | 0 | 2 | |||

| 30–39 years | 7 | 2 | |||

| 40–49 years | 8 | 3 | |||

| 50–59 years | 2 | 1 | |||

| 60+ years | 1 | 0 | |||

| Time in profession | |||||

| 1–5 year | 4 | 1 | |||

| 6–10 years | 5 | 4 | |||

| 11–20 years | 6 | 1 | |||

| 21+ years | 3 | 2 | |||

CIG, cooperative inquiry group.

, Three of the managers were trained professionals: a social worker, professional nurse and occupational therapist.

Selection of cooperative inquiry group members

The researcher consulted with the respective service managers from all the groups described in the setting section to identify key role players. Because of practical and logistical considerations such as transport problems and work schedules, two cooperative inquiry groups (CIGs) were formed (Table 3). All but one invited person joined the process.

The CBS-CIG consisted of 18 service providers from the Cape Winelands District CBS management, Boland Hospice and APD. The MDP-CIG consisted of eight MDPs from the Breede Valley District and the university and included both clinical and educational expertise.

The inquiry process

Both CIGs engaged in a 15-month collaborative inquiry from September 2014 to December 2015. The inquiry focused on the interprofessional design and development of an appropriate training program for CHWs to train family caregivers of stroke survivors. Cooperative inquiry group members contributed from their own experience, knowledge and available evidence related to caregiver training needs and interventions. The researcher, who was ultimately responsible for driving the research agenda and processes, engaged in a consultative and collaborative manner (Higginbottom & Liamputtong 2015) and shared findings and conclusions between the two CIGs. A mutually designed timetable and activity chart guided the process. This, together with small group assignments, contributed to accountability. With the diversity in members of the CBS-CIG, a dedicated effort was made by the researcher to create a neutral, democratic and collaborative meeting space. The inquiry process is described under the first three steps of the ADDIE model.

Analysis step

During this step, the CIGs triangulated findings from the preceding studies (Scheffler & Mash 2019, 2020a), the available evidence (Cameron et al. 2016; Forster et al. 2012; Lindsay et al. 2014) and their own professional experience to define the CHWs’ learning needs and characteristics as learners, taking into account the CHWs’ broader scope of practice. They also considered the needs of potential trainers, their characteristics as educators, as well as the training resources required. Finally, they analysed the community and service context within which CHWs would need to perform after training.

Design step

In the design step, the CIGs utilised the information generated in the analysis step to formulate the following:

learning outcomes

educational approach

rehabilitation philosophy

training resources required

approach to assessment of trainees

structure of the training and time allocation.

Development step

In this phase, the CIGs developed learner and trainer materials and resources, as well as learner assessment tools.

Data collection and consensus building

Data collection and consensus building are described under the first three steps of the ADDIE model.

Analysis step

Both CIGs held three 3-h meetings and participated in group discussions and nominal group activities to reach consensus and rank ideas (McKillip 1987). All meetings were audio-recorded and transcribed. Small group activities were recorded using field notes, flipchart summaries and photographs. The researcher compiled a detailed summary of each meeting, which was validated at the next meeting.

Design step

Using the same activities, both CIGs met twice to reach a consensus on the design. Following the development and validation of the key programmatic and sessional learning outcomes, the researcher developed an outline of the course structure with key topics, which were reviewed and revised by the CIGs via e-mail. Following consensus on the structure and time allocation, the final design was critically reviewed by five external reviewers who were experts in the field of stroke rehabilitation and training or education.

Development step

The researcher was primarily responsible for the development of the materials according to the design and collaborated closely with relevant CIG members. The psychosocial management session was developed by a CIG subgroup of four social workers and one occupational therapist. The materials were developed according to the design, with attention to evidence-based rehabilitation practice and what was feasible in the local context. Consensus building and validation within the CIGs followed the same process as described in the design step above. All CIG members and the external reviewers reviewed the final materials.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee 1 at Stellenbosch University (ref. no. S13/09/158), and permission was obtained from the Department of Health to conduct the study.

Results

This section reports on the results of the planning of the CIGs in the first three steps of the ADDIE model, namely analyse, design and develop.

Analysis

The following key factors that influenced the design of the training course were identified.

Community health workers’ scope of practice

The CHWs did not have any stroke- or rehabilitation-specific training. Their scope of practice already included health education, basic observations, training of family caregivers, assistance with daily living, monitoring patient and caregiver function and well-being, monitoring of treatment adherence, identification and referral of psychosocial problems and excluded patient assessment and care plan development (Boland Hospice 2014).

As generalists on the PHC platform, their prior training incorporated key principles of person-centeredness, continuity of care and intersectoral coordination. These principles were integrated into the new learning materials while taking note of existing competencies. Care was taken not to duplicate the scope of practice of midlevel rehabilitation workers.

Community health workers’ learning needs

The consensus on the CHW learning needs was positioned within their scope of practice and included:

knowledge about stroke: what it is, risk factors, causes, prevention, recovery

knowledge about stroke rehabilitation: rehabilitation services available in the province, district and HCBC and the roles and responsibilities of CHWs, caregivers and patients

knowledge to provide emotional support, reduce and monitor caregiver strain and identify psychosocial problems

knowledge and skills to teach caregivers how to assist stroke survivors with basic activities of daily living, positioning, transfers and mobility

knowledge on assistive products, including low-cost alternatives and how to access these

knowledge on stroke survivor and caregiver safety, including prevention of falls and prevention of secondary complications

ability to problem-solve around common environmental barriers

knowledge and skills to teach basic rehabilitation exercises.

Distinct differences, however, existed between the two CIGs on how these learning needs were phrased. Whereas the CBS-CIG formulated learning needs in terms of plain language and functional activities, the MDP-CIG used professional jargon and emphasised impairments and theoretical principles. The final consensus was to formulate learning needs in terms of practical and functional activities that were informed by underlying theory, even if the theory was not always explicit.

Community health worker competencies

Six key CHW competencies needed to train caregivers were identified. Although these competencies all existed in a generic way, they needed to be specifically related to stroke:

transfer knowledge to caregivers and stroke survivors by explaining, informing and educating

transfer skills to caregivers and stroke survivors through explanation, demonstration and practice with feedback

evaluation of caregivers’ skills and knowledge

provide emotional support to caregivers and stroke survivors and monitor for caregiver strain

know when and how to get help from medical, rehabilitation and social services

manage themselves in terms of their own roles and boundaries, as well as caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ expectations.

Characteristics of community health workers as learners

Although the CHWs had all completed high school, the majority only had basic literacy and numeracy competencies. The first language of the majority was Afrikaans, followed by isiXhosa and English, with English being the common language. In addition to in-service training, some had completed basic education modules in home-based care. They preferred learning skills through observation, role-play and practice with feedback. Although they had limited knowledge, the CHWs were highly receptive to training on home-based stroke rehabilitation and motivated to learn more.

Characteristics of the trainers

Training was to be delivered by the MDPs, who had experience in stroke rehabilitation and working in low-resourced settings. Although having previously provided in-service training, they had no background in the development of formal structured training programs targeting a community-based health problem.

Trainer resources required

No appropriate existing training materials could be identified. Both CHWs and caregivers complained about having received conflicting information in the past, highlighting the need for a trainer’s manual with detailed session plans to ensure a structured, uniform training approach and content. This would be an important resource for use by MDPs and their students.

Service contextual factors

The lack of clinical practice pathways at the HCBC level resulted in a poor understanding of the CHWs’ rehabilitation role, as well as unmet expectations and unrealistic demands of stroke survivors and caregivers. These factors, together with a lack of insight and support from formal services, resulted in many CHWs assuming additional tasks and responsibilities outside their scope of practice. This raised liability issues and concerns about their own well-being. Community health workers also functioned in isolation from the MDPs and other PHC services, resulting in the fragmentation of services. The program included defining and clarifying the CHWs’ roles and establishing referral systems to MDPs and PHC services. Wider service problems were identified, mostly related to the lack of clinical practice pathways, such as delayed referral to HCBC, fragmentation of services and inadequate provision of assistive products. These problems were escalated to service managers, as this fell outside the scope of the educational initiative.

Design

The design of the training program was based on the information generated during the analysis phase.

Program structure and time allocation

The final structure based on the key programmatic outcomes is summarised in Table 4. While there was good consensus on the structure, suggested time allocations varied widely between CIG members. Individuals who regularly provided skills training allowed more time for observation and practice, whereas others allowed more time for theory. The final time allocation for the program was 21 h.

TABLE 4.

Program outline and time allocation.

| Session name and number | Duration in minutes |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | 15 |

| 2. What is a stroke? | 55 |

| 3. Stroke services and rehabilitation | 55 |

| 4. Communication problems | 55 |

| 5. Emotional and social well-being | 180 |

| 6. Problems with the mind and behaviour | 60 |

| 7. Positioning | 120 |

| 8. Moving in bed | 180 |

| 9. Transfers | 180 |

| 10. Bladder and bowel management and using the toilet | 30 |

| 11. Eating, drinking and swallowing safely | 45 |

| 12. Mouth care | 25 |

| 13. Washing | 50 |

| 14. Dressing | 30 |

| 15. Moving around | 120 |

| 16. Rehabilitation exercises | 60 |

|

| |

| Total time | 1260 |

Learning outcomes

Through multiple reviews, 15 key programmatic learning outcomes as well as detailed learning outcomes for each of the sessions were identified (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Key programmatic outcomes (aims) and learning outcomes of the 16 sessions.

| Session | Programmatic learning outcomes | Sessional learning outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | ||

| Introduction | To introduce the trainers and CHWs to each other and to explain the learning outcomes of the training program | By the end of the session, the CHWs should:

|

| Stroke information and services | ||

| What is a stroke? | To enable CHWs to explain to patients who had a stroke and their family caregivers the causes, symptoms≈and problems associated with a stroke, as well as recovery after a stroke | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain to the patient and the family caregivers:

|

| Stroke rehabilitation and services | To enable CHWs to explain the aims, benefits and principles of stroke rehabilitation to patients who had a stroke and their family caregivers with specific reference to the home-based rehabilitation that patients will receive at primary health care level | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain to the patient and the family caregivers:

|

| Psychosocial management | ||

| Emotional and social well-being | To establish and maintain healthy supportive relationships between the CHW, patients who had a stroke and their families and to identify psychosocial risks to the patient’s well-being | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to:

|

| Rehabilitation knowledge and skills | ||

| Communication problems | To enable CHWs to guide and support family caregivers to communicate effectively with patients who had a stroke and who experience problems with communication | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain and provide guidance to the patient and the family caregivers on:

|

| Problems with the mind and behaviour | To enable CHWs to teach family caregivers to manage and interact effectively with patients who have had a stroke and who are experiencing problems with the mind (cognitive problems) and behaviour | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to teach and provide guidance to family caregivers on:

|

| Positioning | To enable CHWs to guide and support patients who had a stroke and their family caregivers on how to position and support the patients in bed and in a chair | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain and/or demonstrate to the patient and family caregiver:

|

| Moving in bed | To enable CHWs to guide and support patients who had a stroke and their family caregivers on how to move the patient in bed and how to help the patient move in bed | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain and demonstrate to the patient and family caregiver:

|

| Transfers | To enable CHWs to guide and support family caregivers on how to transfer or help transfer patients who had a stroke | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain and demonstrate to the patient and family caregiver:

|

| Incontinence and toileting | To enable CHWs to guide and support family caregivers to improve bladder and bowel management, do safe toilet transfers and select alternative toileting options for the home bedroom | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to:

|

| Eating, drinking, and swallowing | To enable CHWs to guide and support family caregivers to help patients who had a stroke and have difficulty eating, drinking and swallowing to do so safely | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to:

|

| Mouth care | To enable CHWs to teach family caregivers to promote and ensure good mouth and dental care in patients who had a stroke | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to:

|

| Washing | To enable CHWs to teach family caregivers how to wash a patient who had a stroke and is unable to wash themselves and how to help patients to wash themselves | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to explain and demonstrate to the patient and family caregiver:

|

| Dressing | To enable the CHW to teach the family caregivers to safely dress the patients who had a stroke and to teach patients how to dress themselves | By the end of the session the CHWs should be able to guide the patient and family caregiver on:

|

| Moving around | To enable CHWs to teach family caregivers how to help a patient who had a stroke move around at home in a wheelchair or walking | By the end of the session, the CHWs should be able to:

|

| Rehabilitation exercises | To enable CHWs to guide patients who had a stroke and their caregivers on how to do basic rehabilitation exercises | By the end of the session the CHWs should be able to:

|

CHW, community health workers; SLT, speech and language therapist.

Approach to teaching

To be appropriate for CHWs, the content needed to be aligned with level three of the SA National Qualifications Framework (South African Qualifiations Authority 2012). Principles of adult learning were adopted (Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Kaufman 2003; Knowles 1970). This allowed for a facilitative style of teaching and active engagement through demonstrations, practice and role-plays in groups of three, with CHWs rotating through three roles: (1) being the stroke survivor, (2) being the family caregiver and (3) being the CHW. Assuming these different roles gave them a vicarious experience of being the recipient of their intervention as well as the CHW. The teaching approach incorporated a spiral curriculum (Harden & Stamper 1999) and a triad of theory–modelling–practice with feedback for learning practical skills (Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Kaufman 2003; Maguire & Pitceathly 2002).

Considering the practical nature of the training, a ratio of one trainer to six learners was needed for small group work and learning skills. Depending on the size of the training venue, resources and trainers, up to 24 learners could be accommodated in a session.

Rehabilitation philosophy underpinning the training program

The Bobath approach (Michielsen et al. 2019; Vaughan-Graham et al. 2009, 2019a, 2019b) was deemed the most appropriate as it follows a functional, problem-solving approach. Recovery is founded on neuromuscular plasticity. By incorporating the principles of task-based training, motor learning and a 24 h approach, normal movement patterns are facilitated and compensatory patterns are limited. This is the only approach to have formally included other categories of healthcare personnel in its training (Friedhoff & Schieberle 2007).

Training resources required

The following training resources were required:

Trainer’s manual with timetable and detailed session plans inclusive of learning outcomes, list of resources needed, guidelines on further adaptation to the local context, preparation required and detailed session plan including timing, teaching methods and approach to formative assessment with model answers and checklists.

PowerPoint presentations (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, United States) to support the theory and process of each session.

Equipment for demonstration and practice purposes. A standard list of equipment would enable training in different settings, such as a nongovernment organisation, local health care facility or community centre. Although access to tables, chairs, therapy mats and examples of wheelchairs and assistive products would be readily available in most settings, it was unlikely that there would be enough beds or treatment plinths. Therapy mats could be used for practising bed mobility but not for bed or bath transfer training. The training manual had to guide trainers to use chairs and tables to allow simulated transfer practice. Examples of self-made assistive products were also needed.

Learner’s manual for CHWs based on the content of the trainer’s manual, incorporating the formative assessments and model answers or checklists, as well as resources such as examples of referral forms.

Detailed sequences of line drawings were needed to supplement the text of the learner’s manual. These same drawings would be used in the other resources as well.

Booklet for caregivers and stroke survivors. A suitable caregiver and patient booklet was previously co-authored by the researcher and revised after a suitability study (Botha 2008; Scheffler & Visagie 2011) for use in a similar community. The booklet was updated and revised accordingly and translated into Afrikaans and isiXhosa (Stellenbosch University 2022).

Assessment

Formative assessments were integrated in each session through case studies and role play activities. Each of the case studies had model answers listed in both trainer’s and learner’s manuals and a checklist for performing activities. These assessments would assist both the trainers and the CHWs to provide or obtain constructive feedback on learning.

Develop

Line drawings were commissioned from purpose-specific photographs taken by the researcher. The text for the trainer’s manual was developed first, and then the PowerPoints and learner’s manual were developed. The stroke survivor and caregiver information booklet were updated and translated. Training resources were developed in English using plain language. This challenged the MDPs. The learner’s manual and information booklet were picture based with limited text. The manuals and information booklet were developed as both hardcopy and online resources, together with the PowerPoint presentations.

Discussion

This study appears to be the first of its kind to design an appropriate stroke training program for CHWs to empower caregivers and stroke survivors in the home. Several stroke interventions, including caregiver training, have been developed through co-creation (Aslani et al. 2016; Dobe et al. 2022; Krieger et al. 2021). However, these programs focus on stroke survivors who have received formal rehabilitation services. These programs are primarily delivered by professionals and also include applications and other technological solutions. In this study, the stroke survivors had not received any formal rehabilitation services.

The training program was designed under the PHC philosophy to address a significant community health problem and was developed through coordinated engagement between local professional and nonprofessional healthcare providers using appropriate technology and resources (Mash et al. 2019; Naidoo, Van Wyk & Joubert 2016; World Health Organization 2008). Technological barriers, such as restrictions on the government computer networks, prevented the use of cloud-based collaborative environments during the design and development phase and impacted the participative process. Primary healthcare in SA is evolving, and MDPs in this study had neither training nor experience in developing community-based interventions and had limited time to participate in such initiatives because of their focus on individual care. Participating in this novel process should lay a foundation for future team-based interprofessional community-oriented PHC interventions. Effective leadership and management are needed to reshape existing care models into comprehensive PHC interventions (Marcus, Hugo & Jinabhai 2017; Schneider et al. 2015).

While stroke caregiver training is routinely delivered by rehabilitation professionals (Bakas et al. 2015; Camak 2015; Chaiyawat & Kulkantrakorn 2012; Forster et al. 2015; Hankey 2013; Mudzi et al. 2012; Sabariego et al. 2012; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Wang et al. 2015), task-shifting to other healthcare cadres is advocated where numbers of rehabilitation professionals are limited (Bryer 2009; Bryer et al. 2011; Hassan et al. 2012; Miranda et al. 2017; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Wasserman, De Villiers & Bryer 2009). Task-shifting to nurses is common (Deyhoul et al. 2020; Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019). However, problems such as increased workload, time implications and inadequate underlying skills and knowledge may undermine such task-shifting (Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2019). No evidence of task-shifting to mid- or grassroots-level workers was found for stroke rehabilitation in LMICs.

Unlike many caregiver training interventions in LMICs, which focus on home-based rehabilitation exercises (Chaiyawat et al. 2009; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019), this training program included minimal teaching of home exercises to ensure that the content was aligned with the CHWs’ scope of practice and avoided overlap with the scope of future midlevel rehabilitation workers. By following the principles of the Bobath neurorehabilitation approach, recovery was promoted through a 24 h therapeutically structured caregiving approach and neuroplasticity by repeated task practice and motor learning. Routinely repeated caregiving activities become therapeutic and synchronous with the therapeutic approach from therapists (Michielsen et al. 2019; Vaughan-Graham et al. 2009, 2019a, 2019b).

The content of this training program was based on an in-depth analysis of the local context and the needs of the caregivers and stroke survivors. In contrast, most caregiver training programs, including those developed in LMICs (Chaiyawat et al. 2009; Chaiyawat & Kulkantrakorn 2012; Deyhoul et al. 2020; Mudzi et al. 2012; Pitthayapong et al. 2017; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Torres-Arreola et al. 2009; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019), have followed a top-down approach with design by professionals from specialist rehabilitation services. Only a few training programs (Dobe et al. 2022; Krieger et al. 2017; Robinson et al. 2005) have been informed by the needs of the target population.

Although the topics covered in this training program were similar to others in the immediate post-acute period in both high-income countries (HICs) (Bakas et al. 2014; Forster et al. 2015; Kalra et al. 2004; White, Cantu & Trevino 2015) and LMICs (Chaiyawat et al. 2009; Chaiyawat & Kulkantrakorn 2012; Deyhoul et al. 2020; Mudzi et al. 2012; Pitthayapong et al. 2017), it differed from existing programs by focusing on culturally and contextually appropriate information and training materials, including low-cost, self-made assistive products. Each lesson plan also provided guidance on how to further adapt the training to the local setting. Contextual appropriateness has only recently been emphasised in stroke training (Krieger et al. 2017; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019).

The low educational levels of both the CHWs and the final target population impacted the selection of teaching methods and the development of training resources. The interactive nature of the adult education teaching model (Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Kaufman 2003; Knowles 1970) accommodated the low literacy levels (Doak, Doak & Root 1996), different learning styles (Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Knowles 1970) and learning of practical skills (Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Kaufman 2003; Maguire & Pitceathly 2002; Mudzi et al. 2012; Nadar & McDowd 2008; Pitthayapong et al. 2017), as well as feedback through assessment (Deyhoul et al. 2020; Hanger & Wilkinson 2001; Kaufman 2003; Maguire & Pitceathly 2002; Mudzi et al. 2012; Pitthayapong et al. 2017). The plain language text of the resources and trainer’s manual and the picture-based format of the learner’s manual and information booklet facilitated access and understanding (Doak et al. 1996).

Poverty, technological barriers (Opoku, Stephani & Quentin 2017) and prohibitive data costs (Independent Communications Authority of South Africa 2017) limited opportunities for CHWs and caregivers to access online information and/or to use electronic teaching and information platforms, necessitating the development of paper-based resources. All resources were also made available online, with online size minimised by using black and white line drawings and low-resolution videos and slide presentations.

With limited access to and availability of psychosocial services, this training program included a substantial focus on psychosocial support within the CHW’s scope of practice, including identification and referral of at-risk families. Although common in training programs in HICs, psychosocial support is less frequent in training programs in LMICs (Pitthayapong et al. 2017; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019).

Although the structure of the training program for CHWs followed a specific sequence and duration, the training of caregivers would be tailored to the stroke survivor’s specific level of functioning and care needs, similar to most training programs (Chaiyawat et al. 2009; Chaiyawat & Kulkantrakorn 2012; Forster et al. 2015; McLennon et al. 2014; Mudzi et al. 2012; Pitthayapong et al. 2017; The ATTEND Collaborative Group 2017; Wang et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019). Progression of caregiver training would be determined by the care coordinators and the CHWs.

As a participatory action research project, the involvement of the service providers was limited because of low numbers and high service demands. None had experience in designing a training program of this scale and nature. Fully collegial roles (Higginbottom & Liamputtong 2015) with equal responsibility for conducting the research project and compiling and implementing the training program were not possible. Cooperative inquiry group members therefore clarified the extent of their involvement at the start. Whereas CIG members are usually both co-researchers and co-subjects during the inquiry (Heron 2014), limited availability shifted the focus to the pragmatic tasks of developing the training program, with reflectivity limited to more practical and operational awareness. Transferability and use of the training program will be limited to similar services, contexts and group characteristics and will need to be adapted for the local context with regard to resources, technology, health care service structure and existing knowledge. The design of the resources allows for this. This article only reports on the planning phase of the inquiry. A future article will report on the implementation of the program and subsequent actions, observations and reflections of the CIGs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated how local healthcare services at the PHC level can design an appropriate, contextually relevant community-oriented intervention through a participatory approach. The CI planning step described in this article used the ADDIE model to analyse, design and develop an appropriate home-based stroke rehabilitation program to be delivered by CHWs in a low-resourced setting. This home-based stroke rehabilitation program and its accompanying training program for CHWs should be implemented and further evaluated in practice.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that this article is partially based on the author’s PhD 2020 thesis entitled The design, development, and evaluation of an appropriate home based stroke rehabilitation program for a rural primary health care setting in the Western Cape, South Africa at Stellenbosch University, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences with the supervisor R. Mash.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

E.S. conceptualised the study, collected and analysed data and reported on the findings. R.M. supervised E.S. as part of her doctoral studies throughout the research process, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Stellenbosch University Rural Medical Education Partnership Initiative through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS relief (PEPFAR) through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under the terms of T84HA21652, the Discovery Foundation Award for health care in rural and underserved areas, the Stellenbosch University Harry Crossley Fund and Fund for Innovation and Research in Rural Health, the International Bobath Instructors Training Association (IBITA) and the South African Society of Physiotherapy.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, E.S., upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in the submitted article are his or her own and not an official position of the institution or funder.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Scheffler, E. & Mash, R., 2023, ‘A stroke rehabilitation training program for community-based primary health care, South Africa’, African Journal of Disability 12(0), a1135. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v12i0.1135

Community health workers are selected from and work as part of ward-based primary health care outreach teams in the communities in which they live. Standardised national accredited training only started in 2016. Many existing CHWs have limited training. Their scope includes health promotion and illness prevention; referral to health services; adherence support and counselling for those with chronic conditions; curative services; and home-based care, which includes facilitation of daily living activities and restoring function, as well as providing psychosocial support.

Midlevel rehabilitation workers work within facilities and community-based rehabilitation services and include physiotherapy and occupational therapy technicians and rehabilitation care workers. Their training programs are of longer duration and at higher educational level than those of CHWs.

References

- Allen, W.C., 2006, ‘Overview and evolution of the ADDIE Training System’, Advances in Developing Human Resources 8(4), 430–441. 10.1177/1523422306292942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aslani, Z., Alimohammadi, N., Taleghani, F. & Khorasani, P., 2016, ‘Nurses’ empowerment in self-care education to stroke patients: An action research study’, International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery 4(4), 329, PMC. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakas, T., Clark, P.C., Kelly-Hayes, M., Lutz, B.J. & Miller, E.L., 2014, ‘Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad intervention: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association’, Stroke 45(9), 2836–2852. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakas, T., Austin, J.K., Habermann, B., Jessup, N.M., McLennon, S.M., Mitchell, P.H. et al., 2015, ‘Telephone assessment and skill-building kit for stroke caregivers. A ronadomized controlled clinical trial’, Stroke 46(12), 3478–3487. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland Hospice , 2014, Community care worker: Job description, Boland Hospice, Worcester. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, J., 2008, The refinement of a booklet on stroke care at home, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, L., Carroll, C. & Barnston, S., 2007, ‘Interventions for adult family carers of people who have had a stroke: A systematic review’, Clinical Rehabilitation 21(10), 867–884. 10.1177/0269215507078313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryer, A., 2009, ‘The need for a community-based model for stroke care in South Africa’, South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 99(8), 574–575, viewed from http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryer, A., Connor, M.D., Haug, P., Cheyip, B., Staub, H., Tipping, B. et al., 2011, ‘The South African guideline for the management of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: Recommendations for a resource-constrained health care setting’, International Journal of Stroke 6(4), 349–354. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camak, D., 2015, ‘Addressing the burden of stroke caregivers: A literature review’, Journal of Clinical Nursing 24(17–18), 2376–2382, viewed 13 September 2022, from 10.1111/jocn.12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, J.I., O’connell, C., Foley, N., Salter, K., Booth, R., Boyle, R. et al., 2016, ‘Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: Managing transitions of care following stroke, guidelines update 2016’, International Journal of Stroke 11(7), 807–822. 10.1177/1747493016660102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawood, J. & Visagie, S., 2016, ‘Stroke management and functional outcomes of stroke survivors in an arubn Western Cape Province setting’, South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 46(3), 31–36. 10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyawat, P. & Kulkantrakorn, K., 2012, ‘Effectiveness of home rehabilitation program for ischemic stroke upon disability and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial’, Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 114(7), 866–870. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyawat, P., Kulkantrakorn, K. & Sritipsukho, P., 2009, ‘Effectiveness of home rehabilitation for ischemic stroke’, Neurology International 1(1), e10. 10.4081/ni.2009.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyhoul, N., Vasli, P., Rohani, C., Shakeri, N. & Hosseini, M., 2020, ‘The effect of family-centered empowerment program on the family caregiver burden and the activities of daily living of Iranian patients with stroke: A randomized controlled trial study’, Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 32(7), 1343–1352. 10.1007/s40520-019-01321-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak, C., Doak, L. & Root, J., 1996, Teaching patients with low literacy skills, 2nd edn., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Dobe, J., Gustafsson, L. & Walder, K., 2022, ‘Co-creation and stroke rehabilitation: A scoping review’, Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–13. 10.1080/09638288.2022.2032411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkor, E.S., 2018, ‘Stroke in the 21st century: A snapshot of the burden, epidemiology, and quality of life’, Stroke Research and Treatment 2018, 3238165. 10.1155/2018/3238165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide, A.H., Mannan, H., Khogali, M., Van Rooy, G., Swartz, L., Munthali, A. et al., 2015, ‘Perceived barriers for accessing health services among individuals with disability in four African countries’, PLoS One 10(5), e0125915. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A., Brown, L., Smith, J., House, A., Knapp, P., Wright, J.J. et al., 2012, ‘Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11(11), CD001919. 10.1002/14651858.CD001919.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A., Dickerson, J., Young, J., Patel, A., Kalra, L., Nixon, J. et al., 2013, ‘A structured training programme for caregivers of inpatients after stroke (TRACS): A cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-eff ectiveness analysis’, The Lancet 382(9910), 2069–2076. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61603-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A., Dickerson, J., Melbourn, A., Steadman, J., Wittink, M., Young, J. et al., 2015, ‘The development and implementation of the structured training programme for caregivers of inpatients after stroke (TRACS) intervention: The London Stroke Carers Training Course Amanda Farrin 6 and on behalf of the TRACS trial collaboration’, Clinical Rehabilitation 29(3), 211–220. 10.1177/0269215514543334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedhoff, M. & Schieberle, D., 2007, Praxis des Bobath-Konzepts. Grundlagen – Handlings – Fallbeispiele, George Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart. [Google Scholar]

- Hafsteinsdóttir, B., Vergunst, M., Lindeman, E. & Schuurmans, M., 2011, ‘Educational needs of patients with a stroke and their caregivers: A systematic review of the literature’, Patient Education and Counseling 85(1), 14–25. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger, H. & Wilkinson, T., 2001, ‘Stroke education: Can we rise to the challenge?’, Age and Ageing 30(2), 113–114. 10.1093/ageing/30.2.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankey, G.J., 2013, ‘Training caregivers of disabled patients after stroke’, The Lancet 382(9910), 2043–2044. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61688-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden, R.M. & Stamper, N., 1999, ‘What is a spiral curriculum?’, Medical Teacher 21(2), 141–143. 10.1080/01421599979752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler, A.L., Tuzzio, L., Hsu, C. & Wagner, E.H., 2018, ‘Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care’, The Annals of Family Medicine 16(3), 240–245. 10.1370/AFM.2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S., Visagie, S. & Mji, G., 2012, ‘The achievement of community integration and productive activity outcomes by CVA survivors in the Western Cape Metro Health District’, South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 42(1), 11–16, viewed 13 September 2022, from http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/123. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, J., 2014, ‘Co-operative inquiry’, in D. Coghlan & M. Brydon-Miller (eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of action research, SAGE Publications, London. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom, G. & Liamputtong, P., 2015, ‘What is participatory research? Why do it?’, in G. Higginbottom & P. Liamputtong (eds.), Participatory qualitative research methodologies in health, SAGE Publications, London, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Communications Authority of South Africa , 2017, Bi-annual report on the analysis of tariff notifications submitted to ICASA for the period 1 July 2017 to 31 December 2017, viewed 19 April 2019, from https://www.icasa.org.za/uploads/files/Bi-Annual-Retail-Tariffs-Report-Q4-2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jaracz, K., Grabowska-Fudala, B., Gó Rna, K., Jaracz, J., Moczko, J. & Kozubski, W., 2015, ‘Burden in caregivers of long-term stroke survivors: Prevalence and determinants at 6 months and 5 years after stroke’, Patient Education and Counseling 98(8), 1011–1016. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, L., Evans, A., Perez, I., Melbourn, A., Patel, A., Knapp, M. et al., 2004, ‘Training carers of stroke patients: Randomised controlled trial’, The British Medical Journal 328(7448), 1099–1101. 10.1136/bmj.328.7448.1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, D.M., 2003, ‘ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Applying educational theory in practice’, British Medical Journal 326(7382), 213–216. 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M., 1970, The modern practice of adult education: Andragogy versus pedagogy, 2nd edn., Association Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, T., Feron, F. & Dorant, E., 2021, ‘Optimising a complex stroke caregiver support programme in practice: A participatory action research study’, Educational Action Research 29(1), 37–59. 10.1080/09650792.2019.1699131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, T., Feron, F. & Dorant, E., 2017, ‘Developing a complex intervention programme for informal caregivers of stroke survivors: The caregivers’ guide’, Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 31(1), 146–156. 10.1111/scs.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne, P., O’donnell, M.J., Lim Chin, S., Zhang, H., Xavier, D., Avezum, A. et al., 2018, ‘Practice patterns and outcomes after stroke across countries at different economic levels (INTERSTROKE): An international observational study’, The Lancet 391(10134), 2019–2027. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30802-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, P., Furie, K.L., Davis, S.M., Donnan, G.A. & Norrving, B., 2014, ‘World stroke organization global stroke services guidelines and action plan’, International Journal of Stroke 9(Suppl A100), 4–13. 10.1111/ijs.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, B.J., Young, M.E., Creasy, K.R., Martz, C., Eisenbrandt, L., Brunny, J.N. et al., 2016, ‘Improving stroke caregiver readiness for transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home’, The Gerontologist 57(5), 880–889. 10.1093/geront/gnw135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maart, S., Eide, A.H., Jelsma, J., Loeb, M.E. & Ka Toni, M., 2007, ‘Environmental barriers experienced by urban and rural disabled people in South Africa’, Disability and Society 22(4), 357–369. 10.1080/09687590701337678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maart, S. & Jelsma, J., 2014, ‘Disability and access to health care – A community based descriptive study’, Disability and Rehabilitation 36(8), 1–5. 10.3109/09638288.2013.807883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, P. & Pitceathly, C., 2002, ‘Key communication skills and how to acquire them’, British Medical Journal 325(7366), 697–700. 10.1136/bmj.325.7366.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, T.S., Hugo, J. & Jinabhai, C.C., 2017, ‘Which primary care model? A qualitative analysis of ward-based outreach teams in South Africa’, African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 9(1), 8. 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maredza, M., Bertram, M.Y. & Tollman, S.M., 2015, ‘Disease burden of stroke in rural South Africa: An estimate of incidence, mortality and disability adjusted life years’, BMC Neurology 15(1), 54. 10.1186/s12883-015-0311-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash, B., Ray, S., Essuman, A. & Burgueño, E., 2019, ‘Community-orientated primary care: A scoping review of different models, and their effectiveness and feasibility in sub-Saharan Africa’, BMJ Global Health 4(Suppl 8), e001489. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, M., 2011, ‘Creating training and development programs: Using the ADDIE method’, Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal 25(3), 19–22. 10.1108/14777281111125363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKillip, J., 1987, Need analysis, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- McLennon, S.M., Bakas, T., Jessup, N.M., Habermann, B. & Weaver, M.T., 2014, ‘Task difficulty and life changes among stroke family caregivers: Relationship to depressive symptoms’, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 95(12), 2484–2490. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielsen, M., Vaughan-Graham, J., Holland, A., Magri, A. & Suzuki, M., 2019, ‘The Bobath concept – A model to illustrate clinical practice’, Disability and Rehabilitation 41(17), 2080–2092. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1417496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, J.J., Moscoso, M.G., Yan, L.L., Diez-Canseco, F., Málaga, G., Garcia, H.H. et al., 2017, ‘Addressing post-stroke care in rural areas with Peru as a case study. Placing emphasis on evidence-based pragmatism’, Journal of Neurological Sciences 375, 309–315. 10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudzi, W., Stewart, A. & Musenge, E., 2012, ‘Effect of carer education on functional abilities of patients with stroke’, International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 19(7), 380–385. 10.12968/ijtr.2012.19.7.380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadar, M.S. & McDowd, J., 2008, ‘“Show me, don’t tell me”; is this a good approach for rehabilitation?’, Clinical Rehabilitation 22(9), 847–855. 10.1177/0269215508091874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, D., Van Wyk, J. & Joubert, R.W.E., 2016, ‘Exploring the occupational therapist’s role in primary health care: Listening to voices of stakeholders’, African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 8(1), a1139. 10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naledi, T., Barron, P. & Schneider, H., 2011, ‘Primary health care in SA since 1994 and implications of the new vision for PHC re-engineering’, in A. Padarath & R. English (eds.), South African health review 2011, pp. 17–28, Health Systems Trust, Durban. [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health , 2018, Policy framework and strategy for ward based primary healthcare outreach teams: 2018/19 – 2023/24, Pretoria, viewed 23 April 2020, from https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/policy-wbphcot-4-april-2018_final-copy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Planning Commision , 2012, National development plan 2030: Our future – Make it work, The Presidency (ed.), Sherino Printers, Pretoria, viewed 13 September 2022, from https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-workr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, N.A.M., Aziz, N.A.A., Aziz, A.F.A., Singh, D.K.A., Othman, N.A.O., Sulong, S. et al., 2014, ‘Exploring views on long term rehabilitation for people with stroke in a developing country: Findings from focus group discussions’, BMC Health Services Research 14, 118. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, D., Stephani, V. & Quentin, W., 2017, ‘A realist review of mobile phone-based health interventions for non-communicable disease management in sub-Saharan Africa’, BMC Medicine 15(1), 24. 10.1186/s12916-017-0782-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandian, J.D., Gandhi, D.B.C., Lindley, R.I. & Bettger, J.P., 2016, ‘Informal caregiving. A growing need for inclusion in stroke rehabilitation’, Stroke 47(12), 3057–3062. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitthayapong, S., Thiangtam, W., Powwattana, A., Leelacharas, S. & Waters, C.M., 2017, ‘A community based program for family caregivers for post stroke survivors in Thailand’, Asian Nursing Research 11(2), 150–157. 10.1016/j.anr.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden, V.R., Crowe, J., Rabbitskin, N., Rolfe, D. & Macaulay, A.C., 2018, ‘Authentic engagement, co-creation and action research’, in F. Goodyear-Smith & R. Mash (eds.), How to do primary care research, pp. 46–56, Taylor & Franceis Group, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoda, A., Mpofu, R. & De Weerdt, W., 2009, ‘The rehabilitation of stroke patients at community health centres in the Western Cape’, SA Journal of Physiotherapy 65(3), 3–8. 10.4102/sajp.v65i3.87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L., Francis, J., James, P., Tindle, N., Greenwell, K. & Rodgers, H., 2005, ‘Caring for carers of people with stroke: Developing a complex intervention following the Medical Research Council framework’, Clinical Rehabilitation 19(5), 560–571. 10.1191/0269215505cr787oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabariego, C., Barrera, A.E., Neubert, S., Stier-Jarmer, M., Bostan, C. & Ciez, A., 2012, ‘Evaluation of an ICF-based patient education programme for stroke patients: A randomized, single-blinded, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on self-efficacy, life satisfaction and functioning’, British Journal of Health Psychology 18(4), 707–728. 10.1111/bjhp.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, E. & Mash, R., 2019, ‘Surviving a stroke in South Africa: Outcomes of home-based care in a low-resource rural setting’, Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation 26(6), 423–434. 10.1080/10749357.2019.1623473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, E. & Mash, R., 2020, ‘Figuring it out by yourself: Perceptions of home-based care of stroke survivors, family caregivers and community health workers in a low-resourced setting, South Africa’, African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 12(1), e1–e12. 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, E.S. & Visagie, S.J., 2011, Stroke care at home, University of Stellenbosch, Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, H., Schaay, N., Dudley, L., Goliath, C. & Qukula, T., 2015, ‘The challenges of reshaping disease specific and care oriented community based services towards comprehensive goals: A situation appraisal in the Western Cape Province, South Africa’, BMC Health Services Research 15(1), 436. 10.1186/s12913-015-1109-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana, O., Labadarios, D., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L., Zuma, K., Dhansay, A. et al., 2013, South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1), viewed n.d., from https://hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageNews/72/SANHANES-launch%20edition%20(online%20version).pd [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., Forster, A. & Young, J., 2004, ‘A randomized trial to evaluate an education programme for patients and carers after stroke’, Clinical Rehabilitation 18(7), 726–736. 10.1191/0269215504cr790oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Qualifiations Authority , 2012, The South African Qualifications Authority: Level discriptiors for the South African national qualifications framework, Waterkloof, viewed 13 September 2022, from http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/misc/2012/level_descriptors.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- South African Qualifiations Authority , 2018a, National certificate: Community health work, viewed 15 April 2020, from http://regqs.saqa.org.za/showQualification.php?id=64769. [Google Scholar]

- South African Qualifiations Authority , 2018b, Registered unit standard: Promote independence in an adult with a physical disability, viewed 23 April 2020, from http://regqs.saqa.org.za/showUnitStandard.php?id=260602. [Google Scholar]

- South African Qualifiations Authority , 2018c, Registered unit standard: Provide support relating to homebased care, viewed 15 April 2020, from http://regqs.saqa.org.za/showUnitStandard.php?id=260598. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa , 2018a, Mortality and causes of death in South Africa, 2016: Findings from death notification, STATSSA, Pretoria, viewed n.d., from https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa , 2018b, Provincial profile: Western Cape. Community survey 2016. Report 03-01-07, Statistics South Africa, Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- Stellenbosch University , 2022, Centre for disability & rehabilitation studies: Resources, viewed from http://www.sun.ac.za/english/faculty/healthsciences/Centre for Rehabilitation Studies/Pages/Resources.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. & Ntusi, A., 2019, ‘Evolving concepts of stroke and stroke management in South Africa: Quo vadis?’, South African Medical Journal 109(2), 69–71. 10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i2.0000932252872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The ATTEND Collaborative Group , 2017, ‘Family-led rehabilitation after stroke in India (ATTEND): A randomised controlled trial’, The Lancet 390(10094), 588–599. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31447-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The SASPI Project Team , 2004, ‘Prevalence of stroke survivors in rural South Africa: Results from the Southern Africa Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI) agincourt field site’, Stroke 35(3), 627–632. 10.1161/01.STR.0000117096.61838.C7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Arreola, L.D.P. et al., 2009, ‘Effectiveness of two rehabiltiation strategies provided by nurses for stroke patients in Mexico’, Journal of Clinical Nursing 18(21), 2993–3002. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Graham, J. et al., 2009, ‘The Bobath concept in contemporary clinical practice’, Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation 16(1), 57–68. 10.1310/tsr1601-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Graham, J. et al., 2019a, ‘Developing a revised definition of the Bobath concept’, Physiotherapy Research International 24(2), e1762. 10.1002/pri.1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Graham, J. et al., 2019b, ‘Important movement concepts: Clinical versus neuroscience perspectives’, Motor Control 23(3), 273–293. 10.1123/mc.2017-0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visagie, S. & Swartz, L., 2016, ‘Rural South Africans’ rehabilitation experiences: Case studies from the Northern Cape Province’, South African Journal of Physiotherapy 72(1), 298. 10.4102/sajp.v72i1.298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.-C. et al., 2015, ‘Caregiver-mediated intervention can improve physical functional recovery of patients with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial’, Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 29(1), 3–12. 10.1177/1545968314532030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S., De Villiers, L. & Bryer, A., 2009, ‘Community-based care of stroke patients in a rural African setting’, South African Medical Journal 99(8), 579–583, viewed 13 Septermber 2022, from http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/3284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, C., Cantu, A. & Trevino, M., 2015, ‘Interventions for caregivers of stroke survivors: An update of the evidence’, Clinical Nursing Studies 3(3), 87–95. 10.5430/cns.v3n3p87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winstein, C.J., Stein, J., Arena, R., Bates, B., Cherney, L.R., Cramer, S.C. et al., 2016, ‘Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery’, Stroke 47(6), e98–e169. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , 2008, The world health report 2008: Primary health care now more than ever, World Health Organization, Geneva, viewed 20 August 2018, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43949/9789241563734_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.L., Chen, S., Zhou, B., Zhang, J., Xie, B., Luo, R. et al., 2016, ‘A randomized controlled trial on rehabilitation through caregiver-delivered nurse-organized service programs for disabled stroke patients in rural china (the RECOVER trial): Design and rationale introduction and rationale’, International Journal of Stroke 11(7), 823–830. 10.1177/1747493016654290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Anderson, C.S., Xie, B. et al., 2019, ‘Caregiver-delivered stroke rehabilitation in rural China’, Stroke 50(7), 1825–1830. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, E.S., upon reasonable request.