Abstract

Objective

Concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and pericardiectomy (PC) can be a technically challenging operation. We sought to study the outcomes of patients undergoing concomitant PC and CABG.

Methods

Between July 1983 and August 2016, 70 patients (median age, 67 years; 88% males) underwent concomitant PC and CABG (PC + CABG group). Multivariable analysis was used to identify predictors of mortality. Matched patients who underwent isolated PC (PC group) were identified, and postoperative outcomes and long-term survival in the 2 groups were compared.

Results

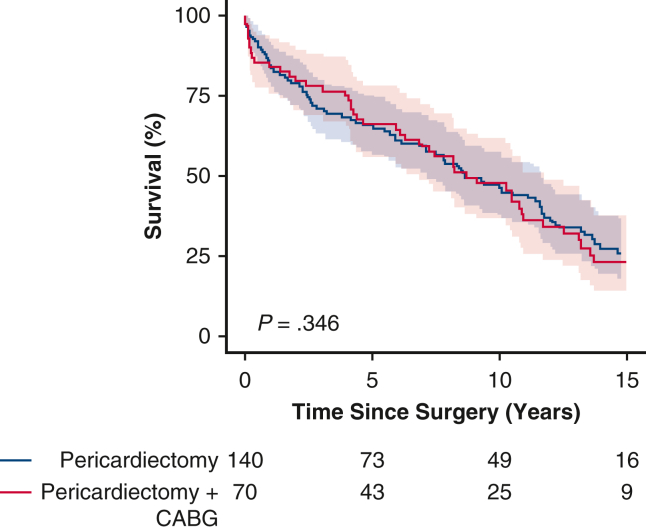

Compared with the PC group, cardiopulmonary bypass time was significantly longer in the PC + CABG group (82 minutes vs 61 minutes; P < .001). In-hospital mortality was 4% in the PC group and 7% in the PC + CABG group (P = .380). Multivariable analysis identified peripheral vascular disease (hazard ratio [HR], 2.67; 95% CI, 1.06-6.76; P = .04) as a predictor of increased morbidity or mortality and a borderline association with New York Heart Association functional classes III and IV (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 0.99-5.86; P = .05) with increased morbidity and mortality in the PC + CABG group. Kaplan–Meier estimates demonstrated similar late mortality rates in the 2 groups at a 15-year follow-up (P = .700).

Conclusions

Concomitant PC and CABG is not associated with increased morbidity or mortality compared with isolated PC. Thus, CABG should not be denied at the time of PC.

Key Words: pericardiectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting, pericarditis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing comparable survival after concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and pericardiectomy (PC) and after isolated PC.

Central Message.

The addition of coronary artery bypass grafting does not add incremental morbidity or mortality to pericardiectomy.

Perspective.

Our analysis shows that concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting with pericardiectomy is a safe procedure. Performing the 2 procedures together does not increase morbidity or mortality. Despite a more extensive procedure, patients with significant coronary artery disease should not be denied coronary artery bypass grafting concomitant with pericardiectomy.

Pericardiectomy (PC) for constrictive pericarditis has been traditionally considered a high-risk operation, with postoperative mortality ranging from 3.9% to 18.6%.1, 2, 3, 4 In addition to PC, patients with severe coronary artery disease may require concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). We identified only a single previous study with just 22 patients requiring concomitant PC and CABG.4 In that study, the presence of coronary artery disease was identified as an independent predictor of late mortality.4 Apart from that study and some isolated case reports,5, 6, 7 outcomes following concomitant PC and CABG have not been described in the literature.

The aim of the present study was to investigate outcomes following concomitant PC and CABG and pericardiectomy, and to compare these outcomes with those in patients undergoing isolated PC.

Methods

A total of 1245 patients who underwent PC at our institution between July 1983 and August 2016, including 837 isolated PCs, were identified. Among these patients, 100 who underwent concomitant CABG performed for coronary artery stenosis were reviewed. We excluded 2 patients who did not give appropriate research authorization and 27 patients with primary ischemic heart disease (rather than pericarditis) who underwent prophylactic PC, as well as 1 patient who underwent CABG for coronary artery aneurysm.

Electronic medical records and operative notes were reviewed. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons definitions were used to define patient baseline characteristics and postoperative outcomes. Matching based on age and sex was done on a cohort of 650 patients who underwent isolated pericardiectomy.

Baseline preoperative characteristics, intraoperative data, and postoperative outcomes were compared between the isolated PC group and concomitant PC and CABG (PC + CABG) group. The primary endpoint of the study was all-cause mortality, for which all patients were followed from the date of surgery to either the date of death or the date of last follow-up. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study (approval no. 19-011985; January 14, 2020).

Surgical Technique

Over a 33-year period, 14 surgeons performed concomitant PC and CABG at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. A median sternotomy was performed in all cases. The extent of PC and the use of cardiopulmonary bypass were at each surgeon's discretion. Our PC technique has been described in previous reports.8,9

Partial PC was defined as removal of the anterior pericardium from phrenic nerve to phrenic nerve. Radical PC was defined as removal of the anterior pericardium, diaphragmatic pericardium, and posterior pericardium behind the left phrenic nerve back to the pulmonary veins.

Statistical Analysis

R version 3.62 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SAS version 9.4M6 (SAS Institute) were used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics included count (percentage) and median (interquartile range [IQR]). The level of statistical significance was defined as P ≤ .05. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) for survival in the concomitant PC + CABG group. Univariable analysis was used to identify factors associated with survival, and significant variables were entered into a model to determine any independent predictors of survival.

Two age- and sex-matched controls from the isolated PC group were identified for each patient in the PC + CABG group. The groups were compared using the χ2 test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to assess survival following surgery, and a stratified log-rank test was used to determine survival differences between the groups. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was introduced to analyze risk factors associated with time to death.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Study population demographics as well as baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy patients who underwent concomitant PC and CABG were included in our study. The primary indication for cardiac surgery was constrictive pericarditis in 61 patients (87%) and effusive/chronic relapsing pericarditis in 9 patients (12%). The median patient age was 67 years (IQR, 60-73 years), and 62 (88%) of the patients were males. Preoperatively, 41 patients (60%) were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III, and 15 (22%) were in NYHA class IV. Twelve patients (17%) had a previous sternotomy, 11 of whom had undergone prior CABG.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | N | Total (N = 210) | PC + CABG group (N = 70) | PC group (N = 140) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 210 | 67.4 (60.2-73.2) | 67.4 (60.4-73.1) | 67.4 (60.2-73.7) | .890 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 210 | 186 (88.6) | 62 (88.6) | 124 (88.6) | 1.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 210 | 27.9 (25.6-32.2) | 27.8 (25.6-30.7) | 28.0 (25.6-32.5) | .608 |

| CHF within 2 wk, n (%) | 209 | 102 (48.8) | 34 (49.3) | 68 (48.6) | .924 |

| Serum creatinine, median (IQR) | 210 | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | .542 |

| Cerebrovascular accident, n (%) | 210 | 10 (4.8) | 5 (7.1) | 5 (3.6) | .252 |

| History of TIA, n (%) | 208 | 5 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (2.9) | .487 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 210 | 61 (29.0) | 23 (32.9) | 38 (27.1) | .390 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 210 | 115 (54.8) | 36 (51.4) | 79 (56.4) | .493 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 210 | 96 (45.7) | 34 (48.6) | 62 (44.3) | .557 |

| NYHA functional class III or IV, n (%) | 208 | 169 (81.2) | 56 (82.4) | 113 (80.7) | .776 |

| PVD, n (%) | 210 | 19 (9.0) | 8 (11.4) | 11 (7.9) | .395 |

| Renal failure (creatinine >2 or dialysis), n (%) | 210 | 22 (10.5) | 9 (12.9) | 13 (9.3) | .426 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 203 | 137 (67.5) | 51 (73.9) | 86 (64.2) | .161 |

| LVEF, %, median (IQR) | 206 | 60 (53-65) | 60 (55-65) | 60 (53-65) | .679 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 210 | 57 (27.1) | 11 (15.7) | 46 (32.9) | .008 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 210 | 33 (15.7) | 13 (18.6) | 20 (14.3) | .421 |

| Urgent status, n (%) | 210 | 31 (14.8) | 12 (17.1) | 19 (13.6) | .492 |

| Previous sternotomy, n (%) | 210 | 76 (36.2) | 12 (17.1) | 64 (45.7) | <.001 |

PC, Pericardiectomy; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; TIA, transient ischemic attack; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

In the matched isolated PC group, 54% of the patients were in NYHA functional class III and 27% were in class IV. Sixty-four patients (46%) had a previous sternotomy, and 46 (33%) had a prior CABG. No significant difference was seen between the 2 groups in terms of other comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, previous myocardial infarction, or preoperative renal failure.

Operative Details

The operative details of both patient groups are summarized in Table 2. Owing to severe heart failure symptoms, the procedure was urgent in 12 patients (17%) in the PC + CABG group. Out of 70 patients in the PC + CABG group, radical PC was performed in 65 (93%), and partial PC was performed in 5 (7%). Cardiopulmonary bypass with aortic cross-clamping was performed more frequently in the PC + CABG group compared with the PC group (84% vs 3%; P < .001). The median cardiopulmonary bypass time was significantly longer in the PC + CABG group compared with the PC group (82 minutes [IQR, 59-120 minutes] vs 61 minutes [IQR, 40-80 minutes]; P < .001). In the PC + CABG group, a single bypass graft was used in 38 patients (54%), 2 bypass grafts were used in 25 patients (36%) patients, and 3 bypass grafts were used in 7 patients (10%). The left anterior descending artery was the most commonly used distal target (n = 54; 77%), followed by the right coronary artery (n = 20; 29%) and obtuse marginal artery (n = 20; 29%). The posterior left ventricular artery (n = 4; 6%) and ramus intermedius (n = 2; 3%) were the least frequently used distal targets. In addition, the inferior mesenteric artery was used for grafting in 46 patients (66%).

Table 2.

Operative data

| Parameter | N | Total (N = 210) | PC + CABG group (N = 70) | PC group (N = 140) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative perfusion technique | 210 | <.001 | |||

| None (off-pump), n (%) | 72 (34.3) | 4 (5.7%) | 68 (48.6%) | ||

| CPB without aortic cross-clamp, n (%) | 75 (35.7) | 7 (10.0%) | 68 (48.6%) | ||

| CPB with aortic cross-clamp, n (%) | 63 (30.0) | 59 (84.3%) | 4 (2.9%) | ||

| CPB time, min, median (IQR) | 138 | 68.0 (51.0-96.0) | 81.5 (59.2-119.5) | 61.0 (39.8-80.2) | <.001 |

| Cross-clamp time, min, median (IQR) | 63 | 28.0 (21.5-38.5) | 29.0 (22.0-39.5) | 19.5 (16.0-24.5) | .203 |

| Grafts for revascularization, n (%) | 70 | ||||

| 1 | 38 (54.3) | 38 (54.3) | - | ||

| 2 | 25 (35.7) | 25 (35.7) | - | ||

| 3 | 7 (10.0) | 7 (10.0) | - | ||

| Target vessels grafted, n (%) | |||||

| LAD | 70 | 54 (77.1) | 54 (77.1) | - | |

| Distal RCA | 70 | 20 (28.6) | 20 (28.6) | - | |

| Ramus intermedius | 70 | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | - | |

| OMA | 70 | 20 (28.6) | 20 (28.6) | - | |

| PLV | 70 | 4 (5.7) | 4 (5.7) | - | |

| PDA | 70 | 6 (8.6) | 6 (8.6) | - | |

PC, Pericardiectomy; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CBP, cardiopulmonary bypass; IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending artery; RCA, right coronary artery; OMA, obtuse marginal artery; PLV, posterior left ventricular artery; PDA, posterior descending artery.

Postoperative Complications and Early Mortality

No significant differences were found between the PC + CABG group and the PC group in terms of prolonged ventilatory support (23% vs 19%; P = .46), median time in the intensive care unit (47 hours [IQR, 25-93 hours] vs 29 hours [IQR, 23-85]; P = .73), and new-onset postoperative renal failure (3% vs 10%; P = .10). The incidences of other postoperative complications, including stroke (P = .62) and reoperation for bleeding (P = 1.00) were similar in the 2 groups. The postoperative complications are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Postoperative characteristics

| Characteristic | N | Total (N = 210) | PC + CABG group (N = 70) | PC group (N = 140) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ICU stay, h, median (IQR) | 173 | 41.5 (23.5-93.0) | 47.0 (25.2-93.0) | 29.0 (23.0-85.0) | .726 |

| Reoperation for bleeding, n (%) | 210 | 15 (7.1) | 5 (7.1) | 10 (7.1) | 1.000 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 210 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | .615 |

| TIA, n (%) | 210 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | .615 |

| Prolonged ventilation (>24 h), n (%) | 210 | 42 (20.0) | 16 (22.9) | 26 (18.6) | .464 |

| New-onset renal failure, n (%) | 188 | 15 (8.0) | 2 (3.3) | 13 (10.2) | .099 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 210 | 44 (21.0) | 17 (24.3) | 27 (19.3) | .401 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 210 | 11 (5.2) | 4 (5.7) | 7 (5.0) | .827 |

| GI bleeding, n (%) | 210 | 12 (5.7) | 3 (4.3) | 9 (6.4) | .528 |

| Multiorgan failure, n (%) | 210 | 6 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (2.1) | .380 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 210 | 11 (5.2) | 5 (7.1) | 6 (4.3) | .381 |

| Readmission within 30 d of surgery, n (%) | 200 | 18 (9.0) | 6 (10.0) | 12 (8.6) | .746 |

| Length of hospital stay, d, median (IQR) | 210 | 7 (6-11) | 7 (6-10) | 7 (6-11) | .788 |

PC, Pericardiectomy; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; TIA, transient ischemic attack; GI, gastrointestinal.

In-hospital mortality was comparable in the PC + CABG and PC groups (7% vs 4%; P = .38). Among the 5 deaths (7%) in the PC + CABG group, 3 were due to sepsis with multiorgan failure on postoperative days 50, 59, and 95. Another patient had difficulty weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass and required a left ventricular assist device; this patient died on postoperative day 6 due to persistent ventricular tachycardia and cardiac arrest. One patient who had a prior CABG with a partial PC underwent completion PC with myocardial revascularization, had extensive bleeding in the operating room, and died on the same postoperative day.

Long-Term Survival

In the PC + CABG group, the median duration of clinical follow-up was 17 years (IQR, 9-21 years), and 5-, 10-, and 15-year survival estimates were 66%, 48%, and 23%, respectively. Following the operation, the median survival in the PC + CABG group was 9 years, and 25% of the patients survived for 14 years (Figure 1). Survival was comparable in the PC + CABG and PC groups (P = .35).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimated survival stratified by surgery type (95% confidence interval). CABG, Coronary artery bypass graft.

Predictors of Mortality in the PC + CABG Group

In the PC + CABG group, female sex was associated with lower mortality (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.12-0.96; P = .042), whereas peripheral vascular disease (PVD; HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.19-6.26; P = .017), NYHA functional class III and IV (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.02-5.26; P = .04), and age (HR = 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07; P = .020) were associated with increased mortality on univariate analysis (Table 4). On multivariable analysis, PVD was associated with mortality (HR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.06-6.76; P = .04), whereas NYHA functional class III or IV was borderline associated with mortality (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 0.99-5.86; P = .05) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariate associations with long-term survival in the PC + CABG group

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.038 (1.006-1.072) | .020 |

| Female sex | 0.339 (0.119-0.962) | .042 |

| BMI | 1.010 (0.957-1.066) | .715 |

| CHF within 2 wk | 1.623 (0.911-2.893) | .100 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.521 (0.598-3.865) | .379 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.282 (0.680-2.419) | .443 |

| NYHA functional class III and IV | 2.314 (1.018-5.257) | .045 |

| PVD | 2.736 (1.195-6.264) | .017 |

| Renal failure (creatinine >2 or dialysis) | 1.166 (0.540-2.519) | .696 |

| LVEF | 0.993 (0.968-1.019) | .615 |

| Previous CABG | 1.656 (0.785-3.495) | .186 |

| Previous sternotomy | 1.830 (0.890-3.764) | .100 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Table 5.

Multivariable model for long-term survival in the PC + CABG group

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| PVD | 2.671 (1.056-6.755) | .038 |

| NYHA functional class III and IV | 2.408 (0.990-5.858) | .053 |

| Age, y | 1.028 (0.993-1.064) | .123 |

| Female sex | 0.733 (0.246-2.181) | .577 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Discussion

We reviewed the effect of concomitant CABG to PC on morbidity and mortality in our study cohort. Our findings show that adding concomitant CABG was associated with a longer cardiopulmonary bypass time but not with increased morbidity or mortality. Furthermore, we identified no difference in long-term survival in patients treated with concomitant CABG and PC.

Removing pericardium from the epicardial surface of the heart can be difficult in the setting of heavily calcified pericardium adherent to the heart surface. Longer surgical time and cardiopulmonary bypass time are often required to achieve adequate resection of pericardium. Consequently, adding CABG to complex PC has been characterized as a high-risk procedure.4 In our study, the left anterior descending artery was the most common target vessel, followed by the right coronary artery and the obtuse marginal artery. The posterior descending artery and posterior left ventricular artery were grafted less often, possibly because of difficulties in locating and exposing them with an adhered and inflamed pericardium. A preoperative or postoperative percutaneous coronary intervention can be considered for such lesions.

We found that procedure-related morbidity and mortality rates were comparable in patients who underwent concomitant CABG and PC and those who underwent isolated pericardiectomy. In some earlier studies of PC, the use of cardiopulmonary bypass was associated with worse postoperative outcomes and greater 30-day mortality.3,10, 11, 12 This might be attributed to a sicker patient population needing either concomitant operations or a technically more difficult PC. Our data do not support the idea that the use of cardiopulmonary bypass for PC with concomitant procedures is associated with worse postoperative outcomes. Despite the significantly longer cardiopulmonary bypass time in the PC + CABG group, the postoperative outcomes and mortality were not different from those in the PC group.

We found an association of PVD with increased mortality and a borderline association of NYHA functional class III and IV with mortality in the PC + CABG group. The relationship between PVD and increased morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing CABG has been well described.13,14 Thus, it is not surprising that PVD is associated with increased long-term mortality in the PC + CABG group. The association of NYHA functional class III and IV with adverse long-term mortality likely reflects a sicker patient population with less physiologic reserve to cope with and recover from complex cardiac surgery.

Few previous studies have reported the outcomes of combined PC and concomitant procedures.4,12 In their study of 97 patients who underwent PC, Busch and colleagues4 reported 54 patients with concomitant procedures, including 22 patients who underwent PC with concomitant CABG. Although there was no difference in 30-day mortality between the patients with isolated PC and those with PC and concomitant procedures, patients with concomitant PC and CABG had worse long-term survival. The authors concluded that concomitant PC and CABG was associated with worse long-term outcomes. However, in that study, 45% of the patients underwent a partial PC, which could have been related to the worse postoperative outcomes.

We believe that adequate resection is necessary to prevent hemodynamic compromise and a low cardiac output state in the postoperative period due to residual constrictive physiology.10,15,16 Thus, we favor more extensive resection and try to perform radical PC when feasible.17, 18, 19 This holds true especially for patients requiring concomitant procedures like CABG with PC, in whom severe diastolic dysfunction and ischemic physiology may cause hemodynamic instability with all that it entails (eg, emergency cardiopulmonary bypass support, which may impact the postoperative outcomes).

Limitations

This study's single-institution and retrospective design was associated with a lack of randomization, confounding, and recall bias. In addition, although this study included a modest number of patients undergoing concomitant PC and CABG, the small total sample size increased the risk of type I and II statistical error. Owing to the low incidence of disease, important preoperative considerations, such as preoperative symptoms, severity of constriction, and degree of coronary disease were left uncontrolled. Moreover, our series represents our institutional experience over the past 33 years, and changes in surgical techniques over this period may have impacted outcomes.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that adding CABG at the time of concomitant PC is not associated with increased postoperative complications. Furthermore, postoperative outcomes, including early and long-term mortality, are comparable in patients undergoing concomitant PC and CABG and those undergoing isolated PC. When appropriate, CABG should not be denied in patients undergoing PC.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lin Y., Zhou M., Xiao J., Wang B., Wang Z. Treating constrictive pericarditis in a Chinese single-center study: a five-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1235–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szabó G., Schmack B., Bulut C., Soós P., Weymann A., Stadtfeld S., et al. Constrictive pericarditis: risks, aetiologies and outcomes after total pericardiectomy: 24 years of experience. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2013;44:1023–1028. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokuda Y., Miyata H., Motomura N., Araki Y., Oshima H., Usui A., et al. Outcome of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis in Japan: a nationwide outcome study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busch C., Penov K., Amorim P.A., Garbade J., Davierwala P., Schuler G.C., et al. Risk factors for mortality after pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis in a large single-centre cohort. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2015;48:e110–e116. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudaka M., Koja K., Kuniyoshi Y., Akasaki M., Miyagi K., Kusaba A. [A case report of surgical treatment of constrictive pericarditis with coronary artery disease] Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;45:1880–1883. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Z., Liu Z., Zhang C. Coronary heart disease complicated with chronic constrictive pericarditis: a case report. Chin J Clin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;13:63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang A.T., Karski J., Cusimano R.J. Successful off-pump pericardiectomy and coronary artery bypass in liver cirrhosis. J Card Surg. 2005;20:284–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2005.200434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho Y.H., Schaff H.V. Surgery for pericardial disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:375–387. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murashita T., Schaff H.V. In: Master Techniques in Surgery: Cardiac Surgery. Grover F.L., Mack M.J., editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016. Pericardiectomy, constrictive and effusive; pp. 387–396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.George T.J., Arnaoutakis G.J., Beaty C.A., Kilic A., Baumgartner W.A., Conte J.V. Contemporary etiologies, risk factors, and outcomes after pericardiectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rupprecht L., Putz C., Flörchinger B., Zausig Y., Camboni D., Unsöld B., et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: an institution's 21 years experience. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;66:645–650. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckmann E., Ismail I., Cebotari S., Busse A., Martens A., Shrestha M., et al. Right-sided heart failure and extracorporeal life support in patients undergoing pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a risk factor analysis for adverse outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;65:662–670. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Straten A.H., Firanescu C., Soliman Hamad M.A., Tan M.E., ter Woorst J.F., Martens E.J., et al. Peripheral vascular disease as a predictor of survival after coronary artery bypass grafting: comparison with a matched general population. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkmeyer J.D., O'Connor G.T., Quinton H.B., Ricci M.A., Morton J.R., Leavitt B.J., et al. The effect of peripheral vascular disease on in-hospital mortality rates with coronary artery bypass surgery. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowdhury U.K., Subramaniam G.K., Kumar A.S., Airan B., Singh R., Talwar S., et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi M.S., Jeong D.S., Oh J.K., Chang S.A., Park S.J., Chung S. Long-term results of radical pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis in Korean population. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14:32. doi: 10.1186/s13019-019-0845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillaspie E.A., Dearani J.A., Daly R.C., Greason K.L., Joyce L.D., Oh J., et al. Pericardiectomy after previous bypass grafting: analyzing risk and effectiveness in this rare clinical entity. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murashita T., Schaff H.V., Daly R.C., Oh J.K., Dearani J.A., Stulak J.M., et al. Experience with pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis over eight decades. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:742–750. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmati P., Greason K.L., Schaff H.V. Contemporary techniques of pericardiectomy for pericardial disease. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]