Abstract

Antiretroviral drug resistance is a therapeutic obstacle for people with HIV. HIV protease inhibitors darunavir and lopinavir are recommended for resistant infections. We characterized a protease mutant (PR10x) derived from a highly resistant clinical isolate including 10 mutations associated with resistance to lopinavir and darunavir. Compared to the wild-type protease, PR10x exhibits ~3-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency and Ki values of 2–3 orders of magnitude worse for darunavir, lopinavir, and potent investigational inhibitor GRL-519. Crystal structures of the mutant were solved in a ligand-free form and in complex with GRL-519. The structures show altered interactions in the active site, flap-core interface, hydrophobic core, hinge region, and 80s loop compared to the corresponding wild-type protease structures. The ligand-free crystal structure exhibits a highly curled flap conformation which may amplify drug resistance. Molecular dynamics simulations performed for 1 microsecond on ligand-free dimers showed extremely large fluctuations in the flaps for PR10x compared to equivalent simulations on PR with a single L76V mutation or wild-type protease. This analysis offers insight about the synergistic effects of mutations in highly resistant variants.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, HIV Protease, Drug Resistance, X-ray Crystallography, Lopinavir, Darunavir, GRL-519, Molecular Dynamics

INTRODUCTION

HIV/AIDS is a severe ailment for an estimated 38 million people with 4 thousand new infections per day [1]. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) promotes viral suppression, which prevents disease progression and lowers the risk of transmission to others [2]. Moreover, antiviral drugs are beneficial for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [3]. However, these successes are compromised by the evolution of drug-resistant virus and virologic failure [4]. Darunavir (DRV) and lopinavir (LPV) are potent antiviral inhibitors of the HIV-1 protease [5]. These two protease inhibitors (PIs) are used in combination ART for treatment-experienced patients with virologic failure [6].

Resistance to PIs arises primarily by mutations in HIV protease [7–9]. HIV protease acts as a dimer and substrates or inhibitors bind in an extended site between the two 99-residue subunits. The structures of ligand-free proteases display various conformations for the flap region (residues 43–58), which have been classified into two major categories, open and curled [10]. Comparison of the structural and enzymatic properties of resistant variants and the wild-type enzyme has revealed different molecular mechanisms for resistance. Mutations of residues in the protease active site often have a direct role in decreasing affinity for inhibitors, while distal mutations can also influence resistance [11, 12]. Resistance mutations that impair protease activity can combine with additional mutations to rescue viral fitness while enhancing drug resistance. Therefore, studying clinical isolates with both resistance and compensating mutations offers a relevant, naturally selected model to study drug resistance.

Several highly-resistant proteases derived from clinical isolates have 10–24 mutations and show 20 to 10,000-fold worse inhibition for tested PIs (reviewed in [13, 14]). Well-characterized examples with structural data include DRV-resistant strains with 10–20 mutations (PRDRV2, PRDRV5, 11Mut,) and cross-resistant clinical isolates with 10–24 mutations (PR20, MDR769, KY, KY V89L revertant, PRS17, PRS17 V48G revertant, and PRS5B) [15–22]. Compared to the wild-type protease, structures of these variants show expanded inhibitor binding sites (PR20, MDR769, KY L89V revertant, 11Mut), alterations in the hinge loop region (PR20, PRS17, PRDRV2, PRDRV5), decreased interactions with inhibitor (PRDRV2, PRDRV5, 11Mut), alterations in distal regions (PR20, 11Mut, KY, PRS17, PRS5B), and/or extreme conformations of the flexible flaps in ligand-free proteases (PR20, MDR769, PRS17, PRS17 V48G revertant) [11, 15–22]. NMR studies and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have demonstrated altered conformational dynamics for the flaps of highly resistant variants PR20 and PRS17 [20, 23, 24]. These biophysical studies confirm the importance of flap mobility for binding of inhibitors and drug resistance.

Here, we identified a clinical isolate in the Stanford HIV drug resistance database (HIVdb) [25–27] with high levels of resistance to all PIs except for tipranavir (TPV). This protease variant has 20 mutations, including 10 mutations associated with resistance to LPV and/or DRV (L10F, V32I, M46I, I54L, L63P, A71V, L76V, I84V, L89V, L90M) [4]. We constructed an optimized recombinant protease (PR10x), performed enzyme kinetics and structural studies by high resolution X-ray crystallography and microsecond molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. PR10x exhibits lower enzymatic activity, worse inhibition, and altered flap conformation and dynamics relative to the wild type enzyme. Insights from this study can inform the design of new inhibitors with high genetic barriers for resistance to improve outcomes in patients with virologic failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification and preparation of PR10x

HIVdb genotype-phenotype data for 1951 protease sequences was queried using a Python script to select a heavily mutated clinical isolate with high drug cross-resistance based on Monogram Biosciences PhenoSense assay [27]. The clinical isolate (SeqID 113050) had 20 mutations, including 10 mutations associated with resistance to DRV or LPV, and showed 100-fold resistance for 7 out of 8 PIs based on EC50 fold-change compared to wild-type virus. The sequence was modified with three mutations that stabilize the protease for structural and kinetic analyses by preventing thiol-bond formation (C95A) and autoproteolysis (Q7K and L33I) [28]. These stabilizing mutations were verified to produce insignificant changes in the proteolytic activity and structure of the native enzyme [29]. The resulting DNA sequence, designated PR10x, was synthesized and inserted into plasmid pJ414 (ATUM) and transformed into competent E. coli BL21(DE3) (New England BioLabs). The protease variant was expressed and purified as described previously [30]. Purified protease was further diluted for enzymatic assays or concentrated to 3.9 mg/mL via Amicon 10kDA centrifugal filters for crystallization.

Inhibitors

Clinical inhibitors DRV and lopinavir (LPV) with HPLC purity of 91.9% and 99.3%, respectively, were obtained from the AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Inhibitor GRL-519 with HPLC purity of >95% was provided by Dr. Arun Ghosh at Purdue University. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO for experiments.

Enzymatic assays

Kinetic values, inhibition constants, and sensitivity to urea were determined via a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) continuous assays as previously reported [31, 32]. Cleavage of FRET substrate analog of HIV-1 p2/NC cleavage site (BACHEM H-2992, Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle-p-nitro-Phe- Gln-Arg-NH2, were Abz is anthranilic acid, Nle is norleucine and p-nitro-Phe is p-nitrophenylalanine) at 25 °C was measured upon addition of freshly refolded enzyme. SigmaPlot (Systat Software) and Solver (Microsoft) were used to calculate enzyme parameters and fit to non-linear plots. The calculated values were averaged over 3–5 replicate runs for each assay. Enzyme parameters Km and kcat were determined by fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Inhibition constants (Ki) were obtained by calculating IC50 values in dose-response plots and solving the equation for tight-binding inhibitors [33]. The UC50 values (concentration of urea at which protease activity is half of the maximum activity in the absence of urea) were calculated from sigmoidal curve fitting as previously described [32].

Crystallographic analysis

Crystallization trials via hanging-drop vapor diffusion using equal volumes of protein stock (3.9 mg/mL) and well reservoir solution were performed for PR10x alone or in complex with a panel of inhibitors (amprenavir (APV), saquinavir (SQV), TPV, LPV, DRV, and GRL-519). The trials yielded diffraction quality crystals of ligand-free PR10x and in complex with inhibitor GRL-519 (PR10x/519). PR10x was complexed with GRL-519 dissolved in DMSO on ice at 1:8 molar ratio and excess DMSO was removed via centrifugation. Crystals of PR10x/519 grew with reservoir solution of 1 M NaCl and 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 5.2. Ligand-free PR10x crystallized in 0.85 M NaCl and 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 5.4. Crystals were cryoprotected in 30% glycerol prior to mounting. X-ray diffraction data were collected remotely using the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline of the Advanced Photon Source in Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL).

For the PR10x/519 structure, diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and scaled via HKL-2000 suite [34] followed by molecular replacement using CCP4i [35] MolRep [36] of CCP4 Suite [37] with the structure of wild-type PR in complex with amprenavir (PDB 3NU3) [38]. Refinement was performed via SHELX-97 [39] and models were fit to electron density maps in Coot [40]. In order to reduce bias, flap residues, inhibitor, and mutated side chains were deleted and rebuilt into omit difference maps (Fo - Fc). Alternate conformations were modeled if visible in the electron density maps for the inhibitor and protein residues. Alternate conformations observed for flaps and inhibitor were matched based on the lack of clashing atoms. Anisotropic B factors were applied in the last stages of refinement. For ligand-free PR10x, diffraction data were processed in the HKL-2000 suite followed by molecular replacement with CCP4i Phaser [41] using a monomer of refined PR10x/519 structure after deleting flap residues 40–60. Rigid body and subsequent refinements were performed with CCP4i Refmac5 [42]. Initially, the main-chain atoms in the omitted flaps were built using ARP/wARP [43] and omit maps. Refinement was performed as described for the PR10x/519 structure, apart from not using anisotropic B factors. Hydrogen bond interactions were identified by distances between non-hydrogen atoms of 2.4–3.6 Å, and distances of 3.6–4.2 Å were used for van der Waals contacts, based on published criteria [44]. Structural figures were made using PyMol (Schrödinger, LLC.). Analysis of B-factors and non-polar interactions was performed using CCP4i Baverage and Contact, respectively.

Protein data bank accession numbers

Crystallographic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 8DCH for PR10x/519 and 8DCI for ligand-free PR10x.

Molecular dynamics simulations

One microsecond classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted and analyzed for ligand-free forms of PR10x and single mutant PRL76V using Gromacs2020 [45] with the CHARMM36m force field [46]. Starting models were prepared from the crystal structure of ligand-free PR10x and the structure of ligand-free PRL76V was modeled from the “open flap” conformation of PR (PDB 2PC0) [10]. Each dimer was simulated using periodic boundary conditions in a rhombic dodecahedron box with a minimum of 10 Å between any protein atom and the nearest cell edge. The systems were solvated with water molecules (TIP3P model [47]) and 150 mM NaCl with additional ions to neutralize the system. Each system was then minimized to 5 kJmol−1 using the steepest descent algorithm before being equilibrated to 300 K using velocity rescaling [48] and 1 bar using the Berendsen barostat [49]. Production MD was performed using the leapfrog integrator with Nose-Hoover [50, 51] and Parinello-Rahman [52] couplings with a 2 fs integration step. Bonds to hydrogen were constrained using the LINCS [53, 54] algorithm. Long-range electrostatic interactions were handled using the particle-mesh Ewald method [55] with a 12 Å cutoff. The same cutoff was used for van der Waals interactions with smoothing applied starting at 10 Å. Atom positions were saved every 10 ps. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the trajectory and root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) calculations were performed on Cα atoms using Gromacs tools. RMSF was computed using the final 900 ns of production. Plots were constructed using matplotlib.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mutations in highly resistant mutant PR10x

PR10x was derived from clinical isolate with SeqID 113050 in HIVdb by introducing 3 mutations to stabilize the protein for enzymatic and crystallographic studies (Figure 1). This sequence has 20 mutations relative to the standard wild-type protease, including 10 resistance mutations conferring major (V32I, I54L, L76V, I84V) and minor (L10F, M46I, L63P, A71V, L89V, L90M) resistance to DRV and LPV, and 3 minor resistance mutations to other PIs (K20T, M36I, I93L) [4, 27]. Notably, only three of these mutations (V32I, G48Q, I84V) alter amino acids in the inhibitor binding site.

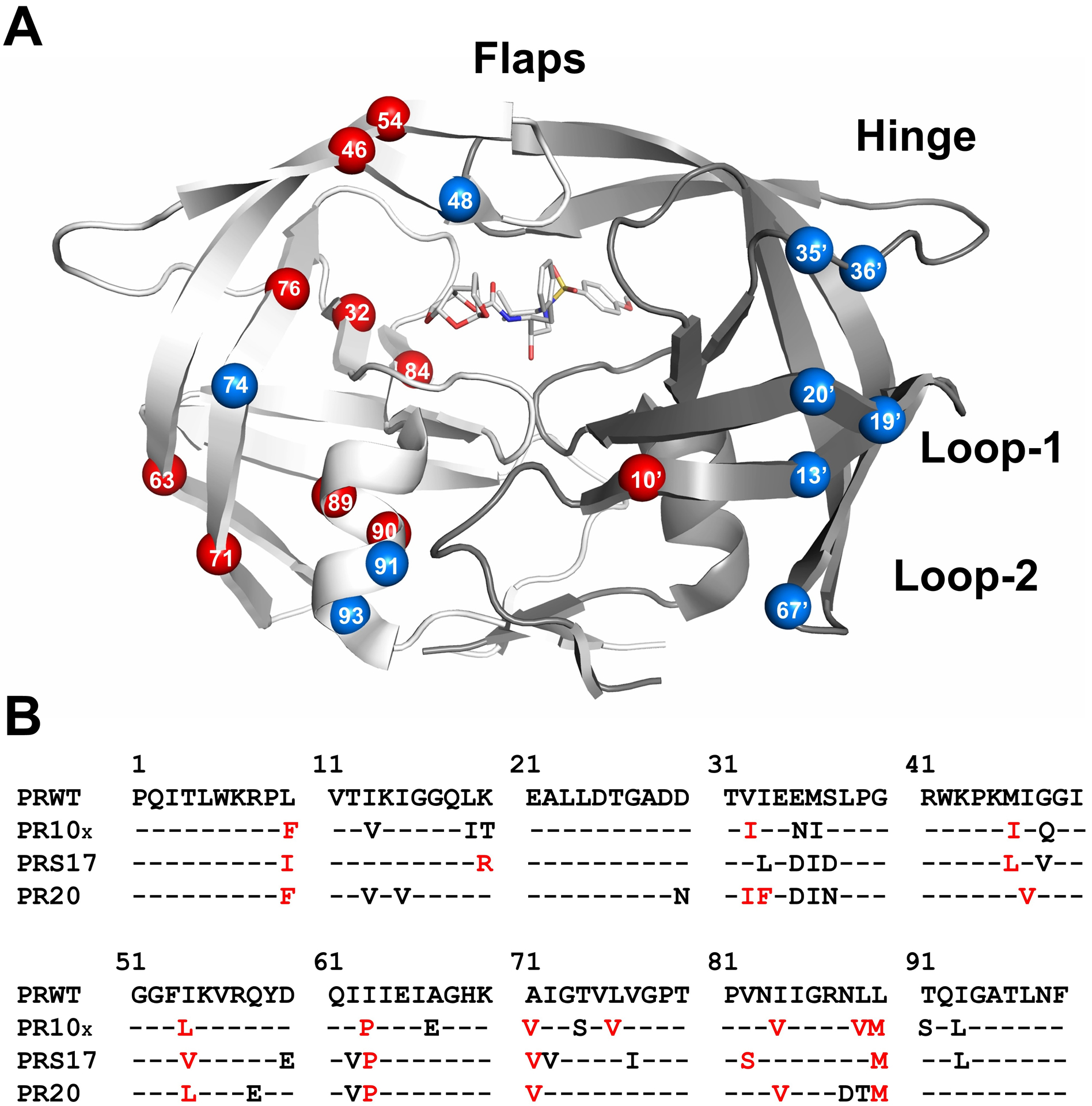

Figure 1: Location of Mutations in PR10x Dimer.

A) Sites of PR10x mutations are shown in the PR dimer in complex with inhibitor GRL-519. The two subunits are indicated by light and dark gray ribbons. GRL-519 is in gray sticks colored by atom. Key structural regions are labeled: residues 43–58 form the antiparallel beta-strands of the flexible flap, residues 34–42 define the flap hinge, and residues 10–23 (loop-1) and 63–73 (loop-2) form two surface loops. Mutations are shown as labeled spheres on the front-facing surface of the dimer. Mutations associated with resistance to DRV and LPV are red and other mutations are blue.

B) Sequences of wild-type PR (HIV-1 subtype-B), PR10x and well-characterized PR20 and PRS17 mutants. Red indicates mutations resistant to DRV and LPV.

Enzymatic properties and inhibition of PR10x

The enzyme kinetic parameters were measured for PR10x and compared with those for wild-type protease. The Km of 88 ± 21 μM determined for PR10x is about 3-fold higher than the wild-type value of 30 μM, while the kcat of 184 ± 23 min−1 for PR10x is similar to the wild-type value of 190 min−1 [38]. Due to the higher Km value, the catalytic efficiency for PR10x of 2.1 ± 0.2 μM−1 min−1 is about 3-fold lower than for the wild-type enzyme at 6.5 μM−1 min−1.

The sensitivity to urea denaturation was measured using a fluorogenic assay for protease activity as described previously [32]. The urea concentration at which protease activity is half-maximal (UC50) for PR10x is about 70% of the wild-type protease value at 0.82 ± 0.08 M versus 1.20 ± 0.06 M, respectively, suggesting the mutant has decreased dimer stability. Other highly resistant variants PRS5B, PRS17 and PR20 gave similar values of 70% or higher relative to wild-type enzyme in these assays [56]. However, individual resistant mutations can produce a greater increase in protease sensitivity to urea. Protease with the single mutation L76V (PRL76V), which also occurs in PR10x, exhibited increased dimer dissociation and a UC50 of about 50% of the wild-type value [57]. Another single mutant, PRG48V, showed about 40% of the UC50 for wild-type protease [29]. PR10x has a different mutation (G48Q) at this position in the flap residue. Therefore, PR10x is more similar to the wild-type protease in urea sensitivity than are single mutants PRG48V and PRL76V.

Inhibition constants (Ki) for PR10x were determined for LPV, DRV, three other PIs and investigational inhibitor GRL-519 (Table 1).

Table 1–

Inhibition Values for PR10x and wild-type PR

PR10x exhibits larger Ki values for all tested compounds compared to values reported for wild-type protease [58, 60]. The relative Ki value for LPV shows a dramatically worse inhibition (3 orders of magnitude) of the highly-resistant protease. Although DRV has a 2 orders of magnitude worse inhibition for PR10x mutant, it maintained single digit nanomolar potency. GRL-519, which is a DRV-derivative that replaces the bis-tetrahydrofuran (THF) at P2 with a stereochemically defined tris-THF, remains potent against DRV-resistant strains in cellular assays [60]. However, GRL-159 has 3 orders of magnitude poorer inhibition of the multiple mutant PR10x. For completeness, inhibition values were also measured for PIs, APV, SQV and TPV. APV and SQV showed only 10–20-fold worse inhibition of PR10x, however, TPV had five orders of magnitude worse inhibition compared to values for wild-type enzyme. The decreased effectiveness of PIs against PR10x as measured by enzyme kinetics is consistent with the high EC50 fold-change reported in HIVdb [25, 26].

Crystal structures of ligand-free and inhibitor-bound PR10x

Diffraction quality crystals were grown for PR10x alone and in complex with inhibitor GRL-519. No crystals grew in trials with other inhibitors. The crystal structure of ligand-free PR10x was solved at 1.62 Å resolution in the P212121 space group and refined to Rwork/Rfree of 18.9/22.7% (Table 2). The amino acids in the two subunits are numbered 1–99 and 1’−99’. The side chains of flap residues Gln48’, Ile50’, and Phe53’ are partially disordered in the second subunit. Therefore, the first subunit was used for structural comparisons. Ligand-free wild-type proteases have been previously described with open or curled flap conformations [10]. The two subunits of ligand-free PR10x superimposed on the most similar wild-type protease monomer with curled flap conformation (PR2HB4, space group P41212, PDB 2HB4) [10] with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for 99 Cα atoms of 1.16 and 1.28 Å for the first and second subunits, respectively. In contrast, both subunits of PR10x show a larger Cα RMSD of 1.69 Å compared to a monomer of a different wild-type protease classified in the open flap conformation (PR2PC0, space group P41212, PDB 2PC0) [10]. Therefore, our structural analysis of ligand-free PR10x focuses on comparison with protease structures with curled conformation flaps.

Table 2–

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics

| PR10x | PR10x/519 | |

|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 8DCI | 8DCH |

| space group | P 212121 | P 41 |

| cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 28.37, 81.35, 85.62 | 56.66, 56.66, 78.16 |

| resolution range (Å) | 50.00 – 1.62 | 50.00 – 1.25 |

| unique reflections | 25,357 | 67,583 |

| redundancy | 5.8 (5.3) | 6.8 (3.3) |

| completeness | 97.9 (95.0) | 99.4 (97.0) |

| I / sigma | 19.1 (4.1) | 20.7 (3.1) |

| Rsym (%) | 7.5 (47.6) | 8.0 (38.9) |

| Rwork (%) | 18.9 | 14.6 |

| Rfree (%) | 22.7 | 18.6 |

| number of solvent molecules | 126 | 224 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||

| main chain | 27.2 | 16.6 |

| side chain | 31.2 | 23.8 |

| inhibitor | n/a | 13.2 |

| solvent | 29.5 | 30.1 |

| RMS deviations from ideality | ||

| bond length (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| angles | 1.7 ° | 0.04 Å |

Values for the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses.

The crystal structure of PR10x in complex with GRL-519 (PR10x/519) was solved in space group P41 at 1.25 Å resolution and refined to Rwork/Rfree of 14.6/18.6% (Table 2). PR10x/519 displays the typical closed flap conformation seen for protease complexes with inhibitor [10]. Flap residues 39–57 and the inhibitor show two alternate conformations at 50% relative occupancies. In the following structural analyses, similar interactions were observed in both alternate conformations of inhibitor unless specifically noted. Superposition of the dimers of PR10x/519 with wild-type protease in complex with GRL-519 (PR/519, space group P21212, PDB 3OK9) [60] showed an RMSD of 1.17 Å on Cα atoms.

The RMSDs of greater than 1 Å suggest significant differences between the two PR10x structures and their wild-type counterparts. However, the structures were determined in different space groups for PR10x (orthorhombic) and PR10x/519 (tetragonal) structures versus the matching wild-type PR (tetragonal) and PR/519 (orthorhombic) structures, which contributes to the larger RMSD values.

Structural changes in PR10x bound to GRL-519

The active site cavity contains major resistance mutations V32I and I84V in the S2–S2’ subsites and M46I, G48Q and I54L in the flaps. Hydrogen bond interactions with both conformations of inhibitor are conserved in PR10x/519 and the corresponding wild-type complex PR/519 (Figure 2A). A conserved network of water-mediated hydrogen bond interactions connects the inhibitor P2 tris-THF with Gly27, Asp29, Arg87 and Arg8’ at the dimer interface of PR10x/519, PR/519 and several single mutant complexes with the same inhibitor [60, 61].

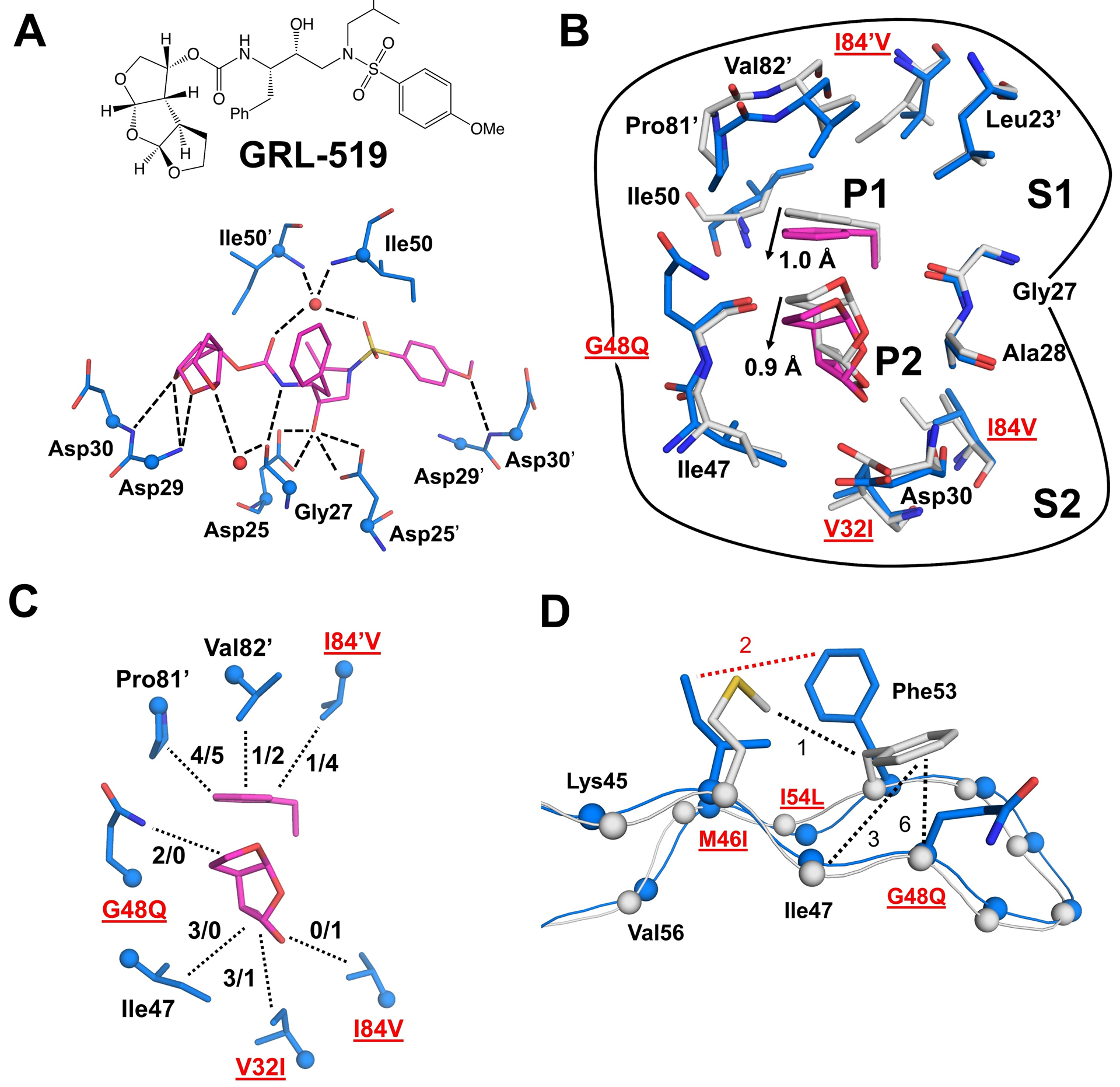

Figure 2: Interactions in inhibitor-binding site and flaps of PR10x/519.

A) Inhibitor GRL-519 (magenta) and its hydrogen bond interactions (dashed lines) with residues in PR10x/519 (blue bonds). Cα atoms are shown as spheres. Conserved waters are red spheres. Hydrogen bond interactions with inhibitor are conserved in PR/519 and PR10x/519 with no more than 0.2 Å variation in distance. The side chains of Asp29/29’ and carbonyl oxygens of Asp30/30’ were removed for clarity.

B) Comparison of S1 and S2 pockets in PR10x/519 (blue/magenta) and PR/519 (gray) shows a correlated shift of residues 81’−84’ and inhibitor P1/P2 groups. Other parts of inhibitor were removed for clarity.

C) Hydrophobic interactions (dotted lines) of inhibitor P1 and P2 groups in S1 and S2 pockets of PR10x/519 (blue/magenta). The number of hydrophobic contacts (PR10x/PR) is indicated for each side chain.

D) Rotation of the Phe53 side chain due to the larger G48Q side chain in PR10x/519 eliminates hydrophobic interactions with the main chain atoms of Ile47 and Gln48. Hydrophobic contacts (dotted lines) are shown in black for PR/519, and red for PR10x/519. Side chains of other residues have been removed for clarity.

The L10F mutation in resistant mutant PR20 in complex with GRL-519 (PR20/519, PDB 4J54) disrupts the intersubunit ion pair between Arg8 and Asp29’ [62]. In contrast, L10F in PR10x/519 retains this ion pair, possibly due to additional mutations such as L19I and K20T in the antiparallel beta-strand opposite to L10F.

The overall number of non-polar interactions with inhibitor is essentially identical in the structures of the multiple mutant PR10x and wild-type protease. However, the P1 phenyl and P2 tris-THF groups of GRL-519 shift by about 1.0 Å and 0.9 Å, respectively (Figure 2B). This shift is coordinated by interactions of inhibitor P1 and P2 groups with different residues due to mutations V32I, G48Q and I84V (Figure 2C). The shorter side chain of I84V in PR10x/519 eliminates hydrophobic interactions with inhibitor P1 and P2 groups as well as with Thr80 and Val82 in the same subunit and Ile50’ in the flap tip of the second subunit (not illustrated). The shifted P1 phenyl also shows decreased hydrophobic interactions with Val82’ in the multiple mutant compared to wild-type protease. The shift of the P2 tris-THF in PR10x/519, combined with the larger side chains of V32I and G48Q, enables the formation of new hydrophobic interactions in the S2 pocket in contrast to the wild-type complex. The longer side chain of G48Q forms new intersubunit contacts with an inverted boat conformation of Pro81’ in the S1 pocket, which contribute to a 1.5 Å shift of Pro81’ towards the inhibitor. A similar Pro81 conformation coupled with a shift in the 80s loop has been previously described in the I10V variant of resistant MDR769 [63]. Resistant mutant PR20 also contains V32I and I84V and shows poor inhibition by GRL-519 [62]. In PR20/519, I84V loses interactions with inhibitor as seen in PR10x/519, however, V32I does not show additional interactions. Moreover, the inhibitor P1 phenyl in PR10x/519 loses hydrophobic interactions with Val82’ and I84V’, while the P2 tris-THF gains compensating contacts with Ile47 and mutated side chains of V32I and G48Q.

In the PR10x flaps, Phe53 side chain rotates toward M46I relative to its position in PR/519, partly due to the larger side chain of G48Q (Figure 2D). Phe53 side chain forms an additional hydrophobic contact with M46I, however, it loses several interactions with main chain atoms of Ile47 and G48Q in the opposite beta strand. A similar rotation of Phe53 was previously described in resistant mutant PRS17 in complex with DRV (PRS17/DRV, PDB 5T2Z) which bears different mutations (M46L, G48V, and I54V) of the same residues [20]. Mutations in these three positions may contribute to altered flap dynamics and inhibition.

Altered interactions of distal mutations in PR10x/519 compared to wild-type PR/519

PR10x includes mutations V32I, T74S, and L76V at the interface between the flap and hydrophobic core of the protein. Compared to PR/519, the shorter side chain of L76V in PR510x/519 loses interactions with Asp30, T74S, and flap residues Lys45, Ile47, Val56, and Gln58, however, L76V gains new contacts with the larger side chain of mutated V32I (Figure 3). PR10x/519 exhibits a greater loss of interactions around L76V compared to single mutant PRL76V bound to GRL-519 (PDB 6DJ5) [31]. Moreover, the smaller side chain of T74S in PR10x/519 eliminates hydrophobic interactions with Gln58 in comparison to the wild-type PR complex. Fewer interactions between the side chains of T74S and Gln58 are also observed in the structure of a DRV-resistant protease with 22 mutations (PDB 3T3C), however, no change was seen in the interactions with Leu76 [64]. A recent report of MD simulations also suggests that L76V can affect the hydrogen bond stability of adjacent residue Asp30 in the active site and Lys45 in the flap [65]. Overall, the combination of mutations in PR10x/519 amplifies the loss of interactions at the flap-core interface.

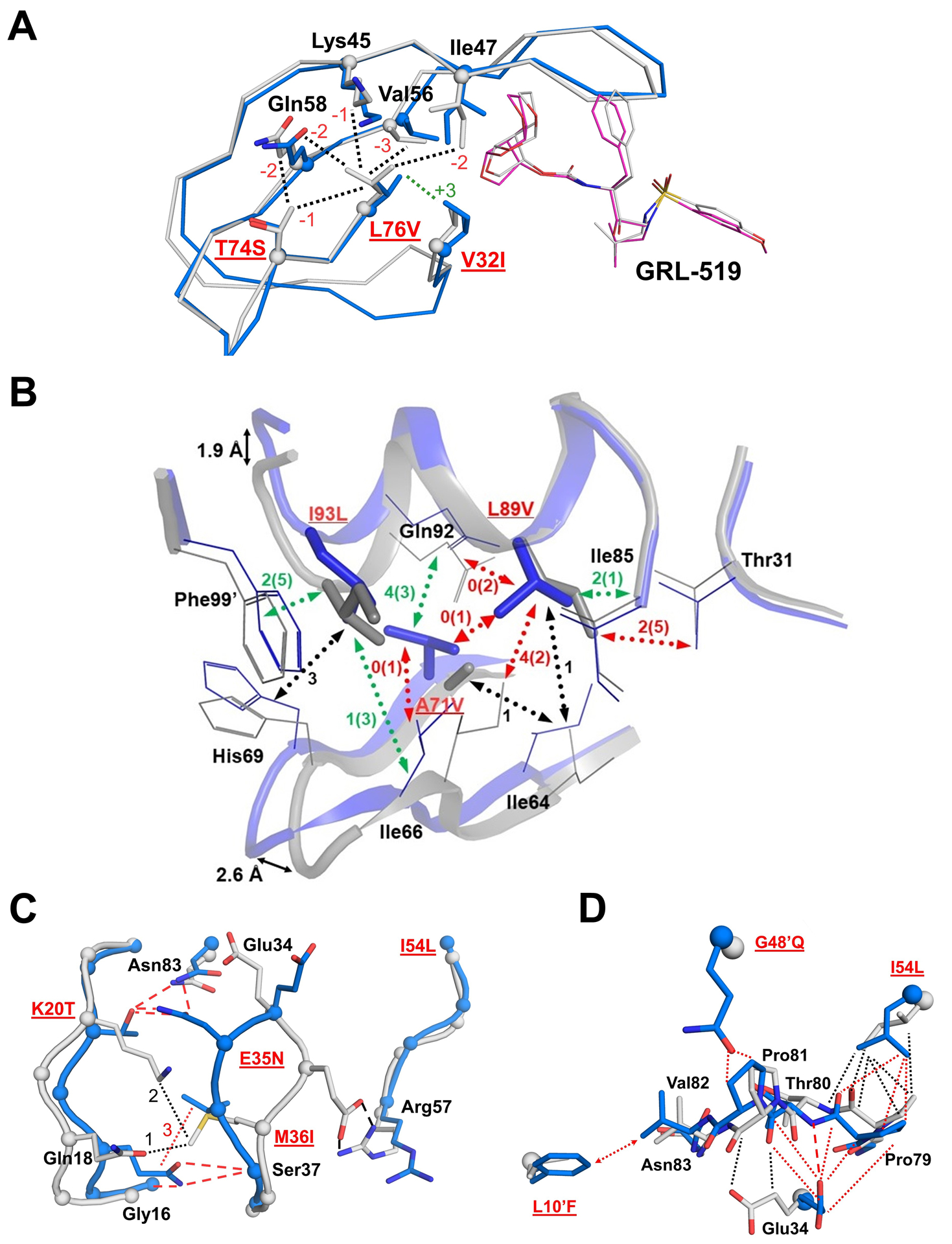

Figure 3: Interactions of distal mutations in PR10x/519 compared to wild-type PR/519.

A) In PR10x/519 (blue/magenta), the smaller side chain of L76V loses hydrophobic contacts with every residue except for V32I in comparison to PRWT/519 (gray). Interactions with Asp30 are also lost (omitted for clarity). The number of increased or decreased interactions compared to PR/519 is indicated next to the dotted lines in green and red, respectively.

B) Hydrophobic interactions of mutated residues A71V, L89V, and I93L and corelated changes of the helix and loop-2. The largest differences in superimposed Cα atoms of PR10x/519 (blue) and PR/519 (gray) are shown as black arrows. Mutations are labeled in red and underlined. Hydrophobic interactions are indicated as dotted lines in black for no change, red when PR10x has fewer contacts than PR, and green if variant has more contacts. Numbers of contacts are shown for PR10x with PR values in parentheses.

C) Conformational changes and interactions of hinge residues 34–36 with flap and loop-1 residues. PR10x/519 is colored blue and PRWT/519 is gray. Interactions are shown in red for PR10x and black for PR. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines and hydrophobic contacts are dotted lines.

D) Altered interactions of L10’F, G48’Q and I54L with the 80s loop. Hydrophobic contacts are shown as dotted lines in black for the wild-type complex and red for PR10x/519. The side chain of L10’F forms new contacts with Val82 as indicated by a dotted line with arrows. One hydrogen bond is indicated by a red dashed line for PR10x.

Distal mutations in PR10x contribute to changes in two other regions: the interfaces of loop-1 with the hinge loop and of loop-2 with the helix. Mutations in PR10x alter the hydrophobic interface between loop-2 (L63P, C67E, A71V) and the helix (L89V, L90M, T91S, I93L) in comparison to the wild-type complex. Shifts in Cα positions of up to 2.6 Å are observed at residues 67–68 in loop-2 and 1.9 Å at residue 94 in the helix (Figure 3B). Similar, although less pronounced, shifts in this region were previously described in the structure of drug-resistant PRS17 [20]. The shorter side chain of L89V in PR10x loses hydrophobic contacts with Thr31, Ile66, A71V, Gly73, and Gln92, and gains one with Ile85. The Gln92 side chain also loses a hydrogen bond with the amide of Ile72 in loop-2. The longer side chain of adjacent mutation L90M forms a shorter interaction of 3.4 Å with the carbonyl oxygen of catalytic Asp25 in PR10x/519 in comparison to 3.8 Å in PR/519, as reported for GRL-519 inhibitor complexes of protease with single mutation L90M and PR20 [17]. Recently, 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations in the KY variant suggested that L90M produces flap fluctuations consistent with a loss of inhibition by DRV at the expense of poorer catalytic activity, and demonstrated that addition of L89V compensates for the loss in enzymatic activity [19].

Hinge residues Glu34, E35N and M36I exhibit distinct conformational changes in PR10x/519 compared to PR/519 (Figure 3C). Residue E35N showed the largest displacement with a Cα deviation of 4.4 Å compared to the wild-type position. As the E35N side chain rotates away from the flaps, its ionic interaction with Arg57 in wild-type PR is replaced by hydrogen bonds with the polar side chains of Asn83 and K20T. The shorter, branched side chain of K20T is partly accommodated by the smaller I13V side chain and it loses hydrophobic contacts with Gln18 and M36I. The shorter side chains of K20T and M36I allow loop-1 to shift closer to the hinge, and the new conformation is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between K20T and E35N as well as between Gln18 side chain and the main chains of Gly16 and Ser37. Large conformational changes in residues 34–36 were also described for the highly resistant variants, PR20, PRS17, and PRS5B [17, 20, 22]. Spectroscopy and MD simulations by other groups suggest that mutations in the hinge alter flap mobility and elimination of the Asp35 to Arg57 salt bridge due to E35D increases backbone dynamics [66–69]. The structural changes in PR10X are in agreement with previous studies showing hinge mutations may alter the dynamics of the flaps.

Mutations in loop-1, the hinge region, and the flaps of PR10x promote the shifting of the 80s loop in the active site (Figure 3D). The coordinated changes include loss of hydrophobic interactions between I54L and Pro79, formation of hydrophobic contacts and a hydrogen bond between Glu34 and upstream residues of the 80s loop, and new interactions between G48’Q in the other subunit with Pro81. The larger side chain of L10’F forms several new hydrophobic contacts with Val82 in PR10x/519, which cannot occur in the wild-type complex. Mutation L10F in PR20/519 forms a similar interaction coupled with a smaller shift in the 80’s loop [62].

Extreme curling of flaps in ligand-free PR10x

The flap region of PT10x bears three mutations, M46I, G48Q, and I54L. The flaps of PR10x display a highly curled flap conformation, which may contribute to the drug resistance phenotype. Structures of ligand-free wild-type protease show open and curled conformations of the flaps, however, highly resistant variants often exhibit more extreme flap conformations [10, 18, 20, 23, 70]. A recent spectroscopy study suggests DRV-resistant mutants favor open flap conformation states over semi-open and closed states [71]. The flap tips of ligand-free PR10x show a higher degree of curling towards the 80’s loop compared to ligand-free wild-type PR2HB4 with curled flap conformation (Figure 4A). Ile50 Cα atom is 11.5 Å away from the corresponding atom in the closed conformation, whereas separations of 4.3–5.4 Å were observed for the curled and open wild-type dimers.

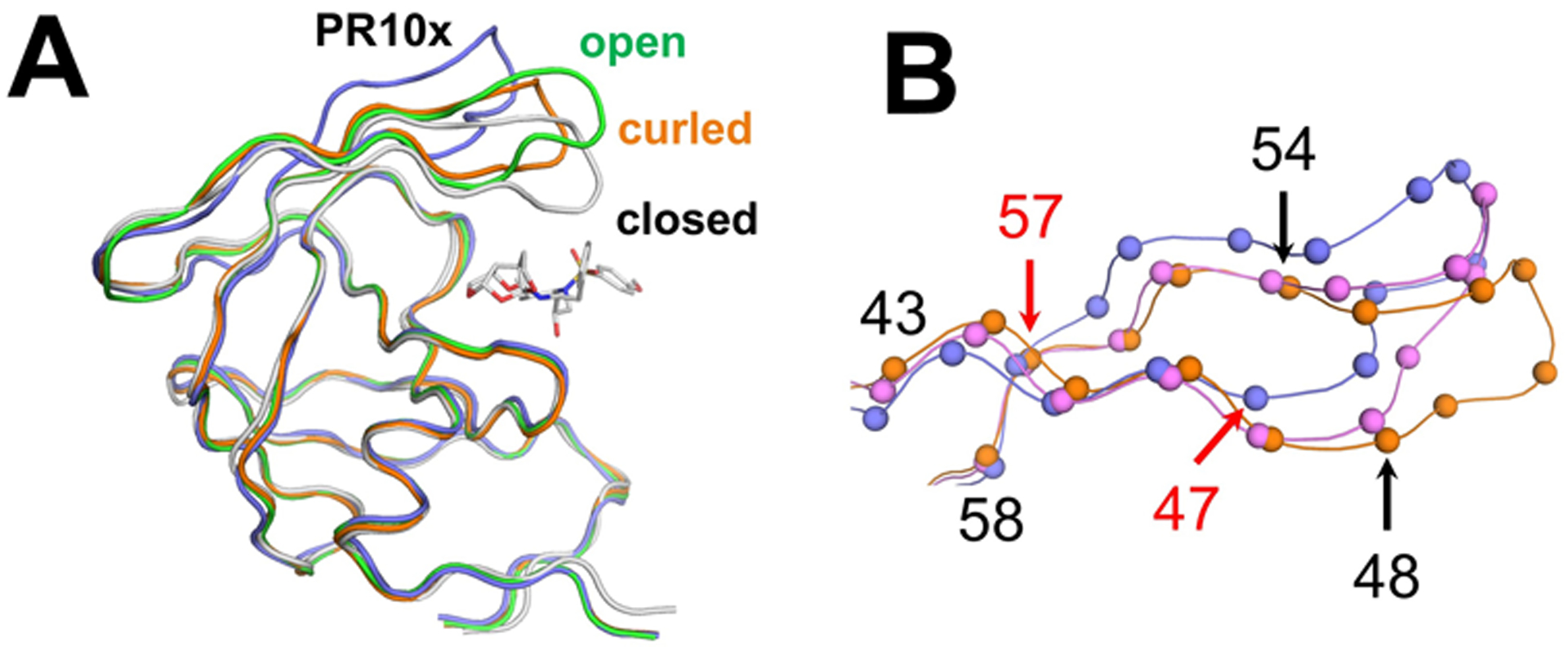

Figure 4: Extreme variation and loss of interactions in the flap of PR10x.

A) The flap in ligand-free PR10x (purple) is further from the closed flap conformation in PR/519 (gray, PDB 3OK9) compared to ligand-free open conformation wild-type PR2PC0 (green, PDB 2PC0), and curled flap conformation in wild-type PR2HB4 (orange, PDB 2HB4). GRL-519 is shown in gray bonds in PR/519.

B) Higher divergence of flaps in PR10x (purple) compared to curled flap conformation in structures of ligand-free wild-type PR2HB4 (orange) and PRS17 (pink, PDB 5T2E). Flaps in PR10x diverge at Ile47 and remain displaced until Arg57 (red arrows). In contrast, the flaps of PRS17 and wild-type curled conformation PR2HB4 diverge at G48V and converge at I54V (black arrows). Cα atoms are shown as spheres.

The overall flap geometry of the anti-parallel beta-hairpin in PR10x differs from that of other ligand-free structures with curled flaps [10, 20] (Figure 4B). PR10x exhibits a higher degree of curling compared to ligand-free PRS17 (space group P3221, PDB 5T2E), which bears different flap mutations (M46L, G48V, I54V) and had the biggest flap curling reported previously. The flap tips of PRS17 and wild-type PR diverge at Gly48/Val48 and converge again at Ile54/Val54. In contrast, the flaps of PR10x diverge one residue earlier at Ile47 and remain displaced until Arg57. Overall, the combination of mutations in PR10x throughout the distal regions, flap-core interface, and the flaps may contribute to the extreme curling of the flaps in PR10x.

One microsecond MD simulations sample extreme dynamics in flaps of PR10x

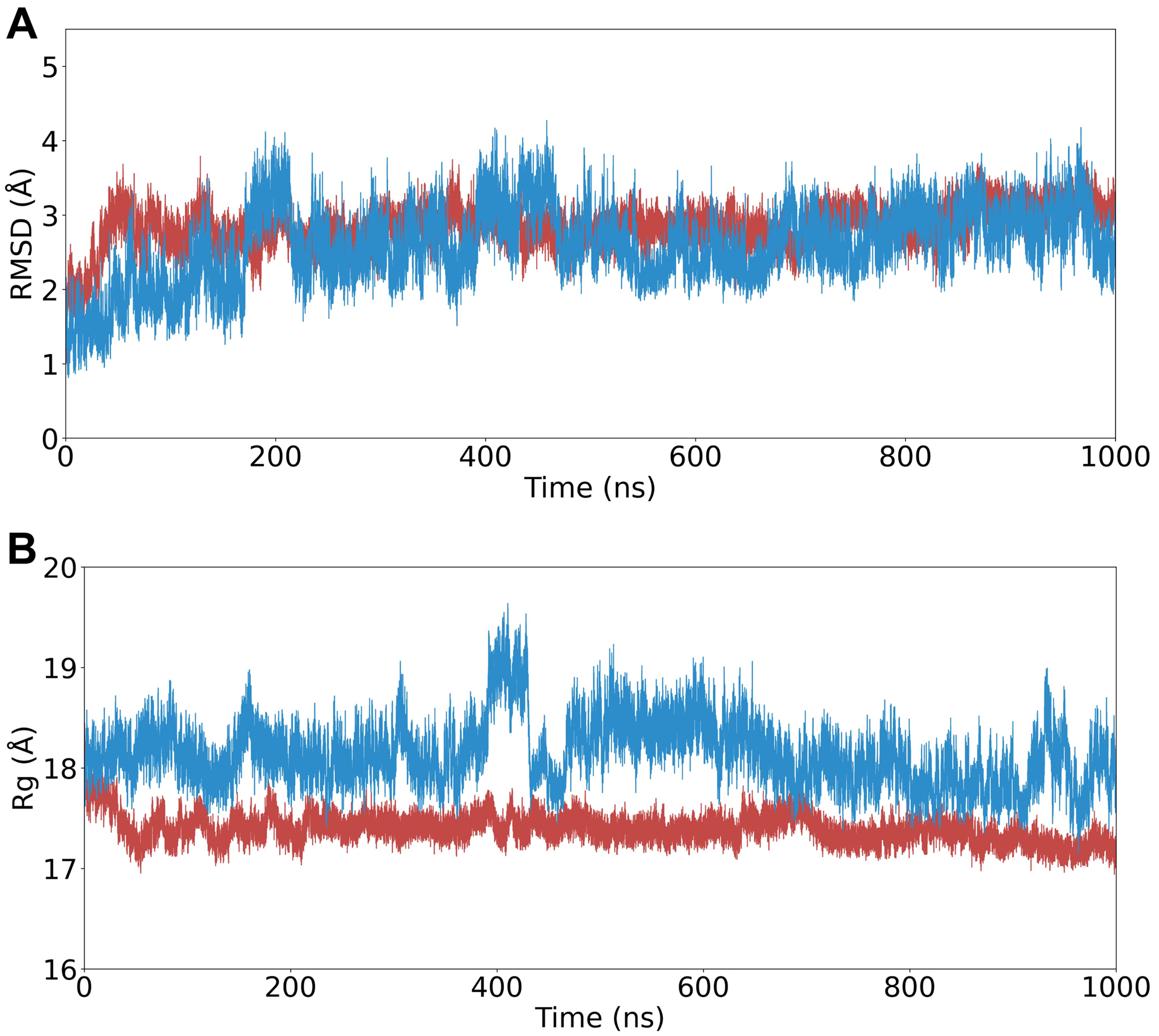

To investigate how mutations in PR10x affect flap dynamics, 1 μs all-atom molecular dynamics simulations were performed for the open-flap conformation observed in the ligand-free crystal structure. For comparison, equivalent simulations were performed for an open-conformation model of PRL76V, since this single mutant resembles PR10x in showing fewer hydrophobic interactions around residue 76 relative to the wild-type enzyme [57]. These MD simulations were compared to 1 μs simulations reported recently for the open conformation of wild-type protease [21]. Visualization showed that each protease dimer behaved consistently throughout the entire 1 μs simulation. Flap dynamics sampled in the simulations were quantified by computing root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the trajectory, radius of gyration (Rg), root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF), and inter-flap distance (Figure 5). The flap conformations observed for the PR10x simulation undulated around the wide-open curled flaps seen in the crystal structure. In contrast, the PRL76V single mutant adopts the closed flap conformation with greater separation between the flap tips, similar to the results previously reported for PR.

Figure 5: Variation over 1 μs MD simulations of PRL76V, and PR76Vmx.

A. Root-mean-square deviation of Cα atoms the trajectory compared to equilibrated starting positions. Starting models were in the open-flap conformations for PR10x (blue) and PRL76V (red).

B. Radius of gyration (Rg) variation over the trajectory.

The RMSD of Cα atoms compared to their equilibrated starting positions captures how the conformations sampled during trajectories are maintained close to their respective open-flap structures (Figure 5A). PR10x and PRL76V showed low RMSD values of 2.6 ± 0.5 Å and 2.8 ± 0.3 Å, respectively (mean ± standard deviation). In an earlier report, simulations of PRWT showed greater deviation from the starting structure (3.6 ± 0.5 Å) due to its adoption of the closed conformation.

The multiple mutant PR10x also exhibits a greater variation in the radius of gyration during the simulation compared to the single PRL76V (Figure 5B). The mean and standard deviation in Rg calculated for PR10x (18.1 ± 0.3 Å) are larger than for PRL76V (17.4 ± 0.1 Å) and wild-type PR (17.5 ± 0.2 Å).

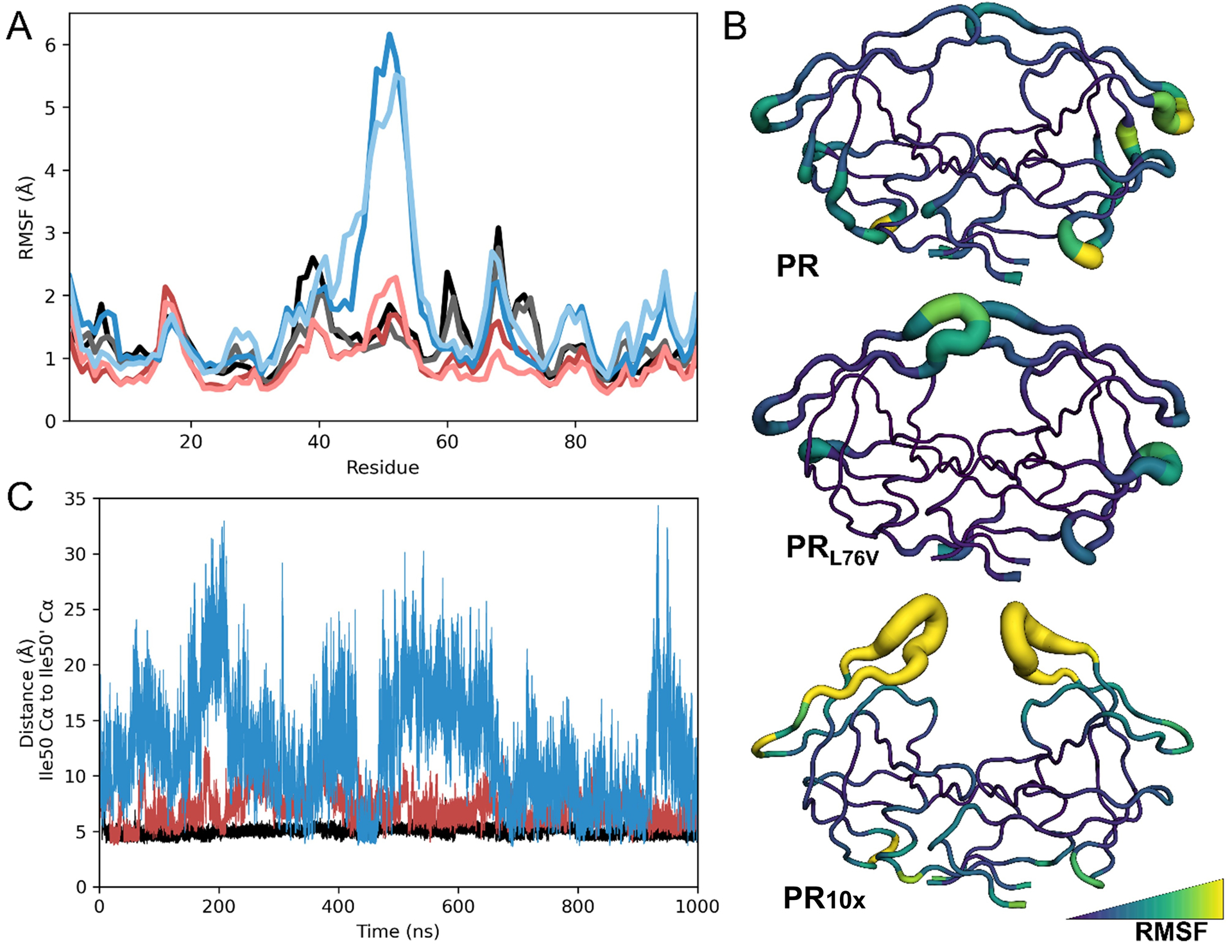

This conformational variation was further analyzed by calculating the root-mean-square fluctuations of Cα positions from their average coordinates (RMSF) (Figure 6A). The RMSF values were used to identify flexible regions in the protease dimers (Figure 6B). PR10x showed extreme conformational flexibility of the flap residues 46–55 with RMSFs ranging from 2.5–6 Å. Each monomer of PR10x exhibited symmetrical RMSF values unlike another highly resistant variant PR20 that showed highly asymmetric fluctuations [23]. The typically rigid 80s loop of residues 78–82 exhibited ~0.5 Å greater RMSF values in the PR10x relative to wild-type protease, consistent with greater flexible of the flaps as suggested by analysis of the crystal structures. However, the flap regions of PRL76V showed RMSF values similar to those of PRWT.

Figure 6: Flap dynamics analysis of MD simulations of PR, PRL76V, and PR10x.

A) Root-mean-square fluctuations of Cα atoms plotted by residue number for each monomer of simulated protease dimers for final 900 ns of production. PR10x monomers are shown in dark and light blue, PRL76V monomers are dark and light red, and wild-type PR is black and gray.

B) RMSF of Cα atoms converted to B-factors and plotted onto the starting structures in the B-factor putty representation and colored in the viridis palette.

C) Interflap tip distances measured from Ile50 Cα to Ile50ʹ Cα for each trajectory.

The erratic conformational changes observed for PR10x resulted in more than double the average inter-flap distances (Ile50/50′ Cα distance of 12.3 ± 4.8 Å) compared to distances of 7.2 ± 1.5 Å for PRL76V and 5.0 ± 0.6 Å for wild-type protease (Figure 6C). The combination of mutations in PR10x results in extreme flap dynamics, which is consistent with the curled flaps captured in the ligand-free crystal structure. Altered conformational dynamics have been described for the flaps of other extremely drug resistant proteases, including PR20 and PRS17, using NMR studies and other MD simulations [20–23, 72, 73]. Large fluctuations and increased flexibility of the flap conformations have also been described for highly resistant variants 11Mut and Mut-3 in MD simulations of inhibitor-bound structures for 100 ns and 700 ns, respectively [16, 74]. These two variants share several resistance mutations with PR10x: variant 11Mut contains I13V, V32I, M46I, I54L, A71V, L76V, and I84V, while Mut-3 shares mutations of L10F, M46I, L76V, and L90M. These biophysical studies confirm the importance of flap mobility for binding of inhibitors and drug resistance.

CONCLUSIONS

The studied protease PR10x contains a total of 20 mutations distributed throughout the structure, including 10 resistance mutations for clinical inhibitors. Analysis of this variant illustrates the importance of compensatory mutations in drug resistance. Compared to wild type protease, PR10x shows a small 3-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency, 70% of the UC50 value, and 13–16000-fold worse inhibition for tested inhibitors. The decreased effectiveness of inhibitors for PR10x is comparable to results reported for other highly resistant variants [15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 63]. While individual resistance mutations such as L76V may decrease dimer stability and autoprocessing, additional mutations like M46I may compensate for such detrimental effects [57]. Additional mutations in PR10x partially rescued protein stability and amplified the loss of potency for DRV, LPV, and GRL-519 compared to values reported for PRL76V [31, 57]. Moreover, the Gag substrate may co-evolve compensating mutations to rescue protease activity while conferring resistance [64]. For example, a Bayesian network learning model revealed several coevolving Gag and protease mutations [75]. A recent 100 ns MD simulation suggests co-selection of A431V in the Gag substrate and L76V in a resistant protease with 4 other mutations (L10F, M46I, I54V, V82A) enhances the binding of substrate [76].

Analysis of the crystal structures shows that hydrogen bond interactions with inhibitor are conserved in PR10x/519 and PR/519. The loss of hydrophobic contacts with inhibitor seen in the S1 pocket of PR10x/519, coupled with conformational changes, are consistent with worse inhibition. Several mutations in PR10x facilitate coordinated shifts in the hinge and the hydrophobic core region formed by loop-1, loop-2, and the helix. Changes in these regions have been previously reported in the structures of resistant PRS17, PR20, PRDRV2, PRDRV5, and PR with 5 mutations including E35D (PR5) [15, 17, 20, 66].

The ligand-free PR10x structure shows the most prominently curled flap observed to date. Flap mutations M46I, G48Q, and I54L may promote the extreme curled conformation, as different mutations in these positions have been associated with the kinked flap tip in PRS17 [20]. MD simulations also suggest increased flap fluctuations in a variants containing M46I and L76V [19, 74]. Decreased interactions of T74S and L76V side chains with residues Val56 and Gln58 of PR10x may further contribute to the prominent divergence of the mega-curled flaps. Moreover, interactions between the side chains of E35N and Arg57 are lost in PR10x, instead Arg57 rotates to interact with the side chain of Trp42 at the N-terminal end of the flap. Changes radiating from T74S and L76V at the flap-core interface to the flap tips could influence drug resistance by enhancing flap mobility and inhibitor dissociation as suggested for other variants [66–69, 77]. Indeed, 1 μs MD simulations confirmed that the dimer of PR10x exhibits an open conformation with extreme flap elasticity in contrast to PRL76V and wild-type protease. This extreme variation in PR10x resulted in almost double the separation between flap tips relative to the separation in wild-type protease. Therefore, this analysis of PR10x demonstrates how several mutations act synergistically to change the structure, enzyme activity, and dynamics of the protease and consequently enhance drug resistance. Fine-tuning our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of resistance available to the virus can improve the design of antiviral inhibitors to add to the available PI-boosted regimens used for patients with virologic failure.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Johnson Agniswamy for valuable discussions. Clinical inhibitors were obtained from the AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. We thank the SER-CAT staff at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, for assistance during X-ray data collection. Supporting institutions may be found at http://www.ser-cat.org/members.html. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (grant numbers AI150461 ITW and RWH, AI150466 AKG); an NIH diversity supplement (AW-S); and a fellowship from the Molecular Basis of Disease Program of Georgia State University (AW-S).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS epidemiological estimates. 2021. [cited 2022 Apr. 27, 2022]; Available from: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/.

- 2.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - HIV Treament as Prevention. March 7, 2022. [cited 2022 Apr. 27, 2022]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html.

- 3.Landovitz RJ, et al. , Cabotegravir for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Men and Transgender Women. N Engl J Med, 2021. 385(7): p. 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wensing AM, et al. , 2019 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top Antivir Med, 2019. 27(3): p. 111–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pokorná J, et al. , Current and Novel Inhibitors of HIV Protease. Viruses, 2009. 1(3): p. 1209–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ClinicalInfoHIV.gov. Clinical Info HIV.gov - Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV. [cited 2022 Apr. 27, 2022]; Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/virologic-failure?view=full.

- 7.Menéndez-Arias L, Molecular basis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance: overview and recent developments. Antiviral Res, 2013. 98(1): p. 93–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konvalinka J, Krausslich HG, and Muller B, Retroviral proteases and their roles in virion maturation. Virology, 2015. 479–480: p. 403–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurt Yilmaz N, Swanstrom R, and Schiffer CA, Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance. Trends Microbiol, 2016. 24(7): p. 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaslet H, et al. , Conformational flexibility in the flap domains of ligand-free HIV protease. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2007. 63(Pt 8): p. 866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ragland DA, et al. , Drug resistance conferred by mutations outside the active site through alterations in the dynamic and structural ensemble of HIV-1 protease. J Am Chem Soc, 2014. 136(34): p. 11956–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menéndez-Arias L and Tözsér J, HIV-1 protease inhibitors: effects on HIV-2 replication and resistance. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2008. 29(1): p. 42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber IT, Kneller DW, and Wong-Sam A, Highly resistant HIV-1 proteases and strategies for their inhibition. Future Med Chem, 2015. 7(8): p. 1023–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber IT, Wang YF, and Harrison RW, HIV Protease: Historical Perspective and Current Research. Viruses, 2021. 13(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozísek M, et al. , Thermodynamic and structural analysis of HIV protease resistance to darunavir - analysis of heavily mutated patient-derived HIV-1 proteases. Febs j, 2014. 281(7): p. 1834–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henes M, et al. , Picomolar to Micromolar: Elucidating the Role of Distal Mutations in HIV-1 Protease in Conferring Drug Resistance. ACS Chem Biol, 2019. 14(11): p. 2441–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agniswamy J, et al. , HIV-1 protease with 20 mutations exhibits extreme resistance to clinical inhibitors through coordinated structural rearrangements. Biochemistry, 2012. 51(13): p. 2819–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, et al. , The higher barrier of darunavir and tipranavir resistance for HIV-1 protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2011. 412(4): p. 737–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henes M, et al. , Molecular Determinants of Epistasis in HIV-1 Protease: Elucidating the Interdependence of L89V and L90M Mutations in Resistance. Biochemistry, 2019. 58(35): p. 3711–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agniswamy J, et al. , Structural Studies of a Rationally Selected Multi-Drug Resistant HIV-1 Protease Reveal Synergistic Effect of Distal Mutations on Flap Dynamics. PLoS One, 2016. 11(12): p. e0168616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burnaman SH, et al. , Revertant mutation V48G alters conformational dynamics of highly drug resistant HIV protease PRS17. J Mol Graph Model, 2021. 108: p. 108005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kneller DW, et al. , Highly drug-resistant HIV-1 protease reveals decreased intra-subunit interactions due to clusters of mutations. FEBS J, 2020. 287(15): p. 3235–3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen CH, et al. , Conformational variation of an extreme drug resistant mutant of HIV protease. J Mol Graph Model, 2015. 62: p. 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis JM and Roche J, Evolution under Drug Pressure Remodels the Folding Free-Energy Landscape of Mature HIV-1 Protease. J Mol Biol, 2016. 428(13): p. 2780–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee SY, et al. , Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res, 2003. 31(1): p. 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafer RW, Rationale and uses of a public HIV drug-resistance database. J Infect Dis, 2006. 194 Suppl 1: p. S51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhee SY, et al. , HIV-1 protease mutations and protease inhibitor cross-resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2010. 54(10): p. 4253–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wondrak EM and Louis JM, Influence of flanking sequences on the dimer stability of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Biochemistry, 1996. 35(39): p. 12957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahalingam B, et al. , Structural and kinetic analysis of drug resistant mutants of HIV-1 protease. Eur J Biochem, 1999. 263(1): p. 238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agniswamy J, et al. , Highly Drug-Resistant HIV-1 Protease Mutant PRS17 Shows Enhanced Binding to Substrate Analogues. ACS Omega, 2019. 4(5): p. 8707–8719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong-Sam A, et al. , Drug Resistance Mutation L76V Alters Nonpolar Interactions at the Flap-Core Interface of HIV-1 Protease. ACS Omega, 2018. 3(9): p. 12132–12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawar S, et al. , Structural studies of antiviral inhibitor with HIV-1 protease bearing drug resistant substitutions of V32I, I47V and V82I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019. 514(3): p. 974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copeland RA, et al. , Estimating KI values for tight binding inhibitors from dose-response plots. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 1995. 5(17): p. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otwinowski Z and Minor W, Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol, 1997. 276: p. 307–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potterton E, et al. , A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2003. 59(Pt 7): p. 1131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagin A and Teplyakov A, Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2010. 66(Pt 1): p. 22–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winn MD, et al. , Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2011. 67(Pt 4): p. 235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen CH, et al. , Amprenavir complexes with HIV-1 protease and its drug-resistant mutants altering hydrophobic clusters. Febs j, 2010. 277(18): p. 3699–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheldrick GM, A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A, 2008. 64(Pt 1): p. 112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, et al. , Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2010. 66(Pt 4): p. 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCoy AJ, et al. , Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr, 2007. 40(Pt 4): p. 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ, Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 1997. 53(Pt 3): p. 240–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamzin VS and Wilson KS, Automated refinement for protein crystallography. Methods Enzymol, 1997. 277: p. 269–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovalevsky AY, et al. , Ultra-high resolution crystal structure of HIV-1 protease mutant reveals two binding sites for clinical inhibitor TMC114. J Mol Biol, 2006. 363(1): p. 161–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abraham MJ, et al. , GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX, 2015. 1–2: p. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang J, et al. , CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods, 2017. 14(1): p. 71–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen WL, et al. , Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1983. 79(2): p. 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bussi G, Donadio D, and Parrinello M, Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys, 2007. 126(1): p. 014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berendsen HJC, et al. , Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1984. 81(8): p. 3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nosé S, A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Molecular physics, 1984. 52(2): p. 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoover WG, Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys Rev A Gen Phys, 1985. 31(3): p. 1695–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parrinello M and Rahman A, Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. Journal of Applied physics, 1981. 52(12): p. 7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hess B, et al. , LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 1997. 18(12): p. 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hess B, P-LINCS: A Parallel Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput, 2008. 4(1): p. 116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darden T, York D, and Pedersen L, Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1993. 98(12): p. 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kneller DW, et al. , Potent antiviral HIV-1 protease inhibitor combats highly drug resistant mutant PR20. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019. 519(1): p. 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Louis JM, et al. , The L76V drug resistance mutation decreases the dimer stability and rate of autoprocessing of HIV-1 protease by reducing internal hydrophobic contacts. Biochemistry, 2011. 50(21): p. 4786–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muzammil S, et al. , Unique thermodynamic response of tipranavir to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease drug resistance mutations. J Virol, 2007. 81(10): p. 5144–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Todd C, HIV/AIDS epidemiology. Lancet, 2000. 356(9238): p. 1357–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghosh AK, et al. , Probing multidrug-resistance and protein-ligand interactions with oxatricyclic designed ligands in HIV-1 protease inhibitors. ChemMedChem, 2010. 5(11): p. 1850–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang H, et al. , Novel P2 tris-tetrahydrofuran group in antiviral compound 1 (GRL-0519) fills the S2 binding pocket of selected mutants of HIV-1 protease. J Med Chem, 2013. 56(3): p. 1074–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agniswamy J, et al. , Extreme multidrug resistant HIV-1 protease with 20 mutations is resistant to novel protease inhibitors with P1’-pyrrolidinone or P2-tris-tetrahydrofuran. J Med Chem, 2013. 56(10): p. 4017–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yedidi RS, et al. , Contribution of the 80s loop of HIV-1 protease to the multidrug-resistance mechanism: crystallographic study of MDR769 HIV-1 protease variants. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 2011. 67(Pt 6): p. 524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kozísek M, et al. , Mutations in HIV-1 gag and pol compensate for the loss of viral fitness caused by a highly mutated protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012. 56(8): p. 4320–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bastys T, et al. , Non-active site mutants of HIV-1 protease influence resistance and sensitisation towards protease inhibitors. Retrovirology, 2020. 17(1): p. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z, et al. , Effects of Hinge-region Natural Polymorphisms on Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Type 1 Protease Structure, Dynamics, and Drug Pressure Evolution. J Biol Chem, 2016. 291(43): p. 22741–22756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang X, et al. , The role of select subtype polymorphisms on HIV-1 protease conformational sampling and dynamics. J Biol Chem, 2014. 289(24): p. 17203–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ode H, et al. , Computational characterization of structural role of the non-active site mutation M36I of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. J Mol Biol, 2007. 370(3): p. 598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meiselbach H, et al. , Insights into amprenavir resistance in E35D HIV-1 protease mutation from molecular dynamics and binding free-energy calculations. J Mol Model, 2007. 13(2): p. 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakashima M, et al. , Unique Flap Conformation in an HIV-1 Protease with High-Level Darunavir Resistance. Front Microbiol, 2016. 7: p. 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Z, et al. , Darunavir-Resistant HIV-1 Protease Constructs Uphold a Conformational Selection Hypothesis for Drug Resistance. Viruses, 2020. 12(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chetty S, et al. , Multi-drug resistance profile of PR20 HIV-1 protease is attributed to distorted conformational and drug binding landscape: molecular dynamics insights. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2016. 34(1): p. 135–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deshmukh L, et al. , Binding kinetics and substrate selectivity in HIV-1 protease-Gag interactions probed at atomic resolution by chemical exchange NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(46): p. E9855–E9862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eche S, et al. , Acquired HIV-1 Protease Conformational Flexibility Associated with Lopinavir Failure May Shape the Outcome of Darunavir Therapy after Antiretroviral Therapy Switch. Biomolecules, 2021. 11(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marie V and Gordon M, Gag-protease coevolution shapes the outcome of lopinavir-inclusive treatment regimens in chronically infected HIV-1 subtype C patients. Bioinformatics, 2019. 35(18): p. 3219–3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marie V and Gordon M, Understanding the co-evolutionary molecular mechanisms of resistance in the HIV-1 Gag and protease. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2021: p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bandaranayake RM, et al. , Structural analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CRF01_AE protease in complex with the substrate p1–p6. J Virol, 2008. 82(13): p. 6762–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]