Abstract

Background

Gender-based differences are reported in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) pathogenesis, but their impacts on IBD outcomes are not well known. We determined gender-based differences in response to treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapies in individuals with ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods

We used the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) platform to abstract individual participant data from randomized clinical trials to study infliximab and golimumab as induction and maintenance therapies in moderately to severely active UC. Using multivariable logistic regression, we examined associations between gender and the endpoints of clinical remission, mucosal healing, and clinical response for each study individually and in a meta-analysis.

Results

Of 1639 patients included in induction trials (Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment—Subcutaneous [PURSUIT-SC], active ulcerative colitis trials [ACT] 1 and 2) and 1280 patients included in maintenance trials (Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment—Maintenance [PURSUIT-IM], ACT 1 and 2), 696 (42.5%) and 534 (41.7%) were women, respectively. In a meta-analysis of induction trials, the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of clinical remission (aOR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31–0.97), mucosal healing (aOR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.27–0.83), and clinical response (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29–0.90) in the treatment arm and of clinical remission in the placebo arm (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.15–0.82) were lower in men compared to women. There were no differences in outcomes by gender in the treatment and placebo arms in the meta-analysis of maintenance trials.

Conclusions

Men are less likely to achieve clinical remission, mucosal healing, and clinical response compared to women during induction treatment with TNFi for UC, but not during the maintenance phase. Future studies delineating the mechanisms underlying these observations would be informative.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, gender, sex-based, meta-analysis, clinical trial data, individual participant data, therapy

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic, progressive, immune-mediated diseases of the gastrointestinal tract and are associated with significant morbidity, disability, and even mortality.1,2 Early and adequate control of inflammation with immune-modifying therapies, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), is crucial to prevent disease progression and complications. Despite marked progress in IBD therapeutics, response to available therapies is variable and our ability to predict who will respond is poor. Identifying how demographic and clinical characteristics impact responses to specific biologics could help refine therapeutic decision-making, and ultimately improve patient outcomes and preserve resources.

There is increasing evidence on gender-based differences in the IBD epidemiology, phenotype, and pathogenesis, which signals that there may be differences in therapeutic outcomes. Recent epidemiological data indicate differences in CD and UC incidences between men and women.3,4 Data on responses to therapy are heterogenous and less clear. Male sex has been associated with reduced clinical responses to TNFi therapy in UC, but with contradictory findings in CD.5,6 Gender-based differences in response to biologics are suggested in other immune-mediated diseases; for example, in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, clinical response to biologics may be better in men compared to women.7,8

The primary objective of our study was to conduct a meta-analysis of individual patient–level clinical trial data in order to evaluate whether gender is associated with differential clinical outcomes in patients with active UC receiving TNFi. We restricted this analysis to clinical trials in UC, given homogeneity in the UC, but not CD, phenotype and outcomes assessment.

Methods

Data Sources

We accessed individual patient–level clinical trial data through the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project, a clinical research data sharing platform with the goal of promoting research and generalizable knowledge.9 The Yale University Open Data Access provides access to deidentified, individual patient–level data from approved clinical trials to researchers upon submission and approval of a research protocol. Our detailed research protocol (YODA Project Protocol number 2018-3737) was reviewed by the YODA scientific committee and was approved on November 28, 2018, with final data user agreements signed on March 19, 2019. Through this platform, we accessed individual patient–level data from clinical trials of available TNFi for the treatment of moderate-to-severe UC (Table 1). Of available trials, we included trials studying the safety and efficacy of golimumab induction in UC (PURSUIT-SC; NCT00487539; sponsor protocol number C0524T17), golimumab maintenance (PURSUIT-IM; NCT00488631; sponsor protocol number C0524T18), and infliximab induction and maintenance in UC (ACT-1 [NCT00036439; sponsor protocol number C0168T37] and ACT-2 [NCT00096655; sponsor protocol number C0168T46]; Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included in induction trials (PURSUIT-SC, ACT 1 and 2) and maintenance trials (PURSUIT-SC, ACT 1 and 2) .a

| Arm | Trial | Variable | Overall | Women | Men | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Pooled | n | 1149 | 476 | 673 | - |

| Women | 476 (41%) | - | - | - | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 30.5 (16.02) | 29.3 (15.19) | 31.3 (16.53) | .037b | ||

| White race | 1005 (87%) | 419 (88%) | 586 (87%) | .65 | ||

| IMM use | 394 (34%) | 157 (33%) | 237 (35%) | .45 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 372 (32%) | 139 (29%) | 233 (35%) | .06 | ||

| ACT-1 | n | 223 | 86 | 137 | ||

| Women | 86 (39%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 42 (14) | 39 (14) | 44 (14) | .008b | ||

| White race | 209 (94%) | 81 (94%) | 128 (93%) | 1 | ||

| IMM use | 96 (43%) | 36 (42%) | 60 (44%) | .78 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 78 (35%) | 26 (30%) | 52 (38%) | .25 | ||

| ACT-2 | n | 226 | 91 | 135 | ||

| Women | 91 (40%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 40 (13) | 39 (12) | 41 (14) | .41 | ||

| White race | 213 (94%) | 87 (96%) | 126 (93%) | .57 | ||

| IMM use | 75 (33%) | 29 (32%) | 46 (34%) | .77 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 81(36%) | 30 (33%) | 51 (38%) | .48 | ||

| PURSUIT-SC | n | 700 | 299 | 401 | ||

| Women | 299 (43%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 24 (13) | 24 (13) | 24 (13) | .84 | ||

| Mean BMI (SD) | 25.35 (5.33) | 24.80 (6.18) | 25.75 (4.57) | .025b | ||

| White race | 583 (83%) | 251 (84%) | 332 (83%) | .76 | ||

| IMM use | 223 (32%) | 92 (31%) | 131 (33%) | .62 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 213 (30%) | 83 (28%) | 130 (32%) | .21 | ||

| Placebo | Pooled | n | 490 | 220 | 270 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 29.25 (16.04) | 28.04 (15.04) | 30.23 (16.78) | .13 | ||

| Women | 220 (45%) | - | - | |||

| White race | 411 (84%) | 185 (84%) | 226 (84%) | 1 | ||

| IMM use | 161 (33%) | 70 (32%) | 91 (34%) | .70 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 158 (32%) | 66 (30%) | 92 (34%) | .38 | ||

| ACT-1 | n | 89 | 37 | 52 | ||

| Women | 37 (42%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 42 (14) | 41 (13) | 44 (15) | .30 | ||

| White race | 81 (91%) | 33 (89%) | 48 (92%) | .71 | ||

| IMM use | 31 (35%) | 11 (30%) | 20 (38%) | .50 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 37 (42%) | 13 (35%) | 24 (46%) | .38 | ||

| ACT-2 | n | 95 | 38 | 57 | ||

| Women | 38 (40%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 40 (14) | 39 (13) | 41 (14) | .65 | ||

| White race | 89 (94%) | 33 (87%) | 56 (98%) | .04 | ||

| IMM use | 38 (40%) | 15 (39%) | 23 (40%) | 1 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 37 (39%) | 13 (34%) | 24 (42%) | .52 | ||

| PURSUIT-SC | n | 306 | 145 | 161 | ||

| Women | 145 (47%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 22 (13) | 22 (12) | 22 (13) | .81 | ||

| Mean BMI (SD) | 24.78 (5.07) | 24.53 (5.74) | 24.99 (4.40) | .433 | ||

| White race | 241 (79%) | 119 (82%) | 122 (76%) | .21 | ||

| IMM use | 92 (30%) | 44 (30%) | 48 (30%) | 1 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 84 (27%) | 40 (28%) | 44 (27%) | 1 | ||

| Treatment (30 weeks) | Pooled | n | 1,098 | 455 (41.44%) | 643 (58.56%) | |

| Women | 455 (41.44%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 29.13 (15.81) | 28.61 (14.71) | 29.49 (16.54) | .35 | ||

| White race | 959 (87.34%) | 400 (87.91%) | 559 (86.93%) | .65 | ||

| IMM use | 386 (35.15%) | 162 (35.60%) | 224 (34.83%) | .79 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 470 (42.80%) | 186 (40.87%) | 284 (44.16%) | .29 | ||

| ACT-1 | n | 178 | 71 (40%) | 107 (60%) | ||

| Women | 71 (40%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 42.02 (14.21) | 38.24 (13.95) | 44.53 (13.88) | .004b | ||

| White race | 170 (96%) | 69 (97%) | 101 (94%) | .48 | ||

| IMM use | 76 (43%) | 32 (45%) | 44 (41%) | .64 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 60 (34%) | 21 (30%) | 39 (36%) | .42 | ||

| ACT-2 | n | 185 | 75 (41%) | 110 (59%) | ||

| Women | 75 (41%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 40 (13.14) | 40 (12.14) | 41.34 (13.83) | .57 | ||

| White race | 176 (95%) | 72 (96%) | 104 (95%) | .74 | ||

| IMM use | 67 (36%) | 28 (37%) | 39 (35%) | .88 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 65 (35%) | 22 (29%) | 43 (39%) | .21 | ||

| PURSUIT-IM | n | 735 | 309 (42%) | 426 (58%) | ||

| Women | 309 (42%) | |||||

| Mean age (SD) | 23.04 (13) | 23.57 (12.62) | 22.66 (13.28) | .34 | ||

| Mean BMI (SD) | 24.96 (5.05) | 24.42 (5.90) | 25.35 (4.29) | .018b | ||

| White race | 613 (83%) | 259 (84%) | 354 (83%) | .84 | ||

| IMM use | 243 | 102 (33%) | 141 (33%) | 1 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 345 | 143 (46%) | 202 (47%) | .77 | ||

| Placebo (30 weeks) | Pooled | n | 182 | 79 (43.41%) | 103 (56.59%) | |

| Women | 79 (43.41%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 36.68 (15.89) | 34.37 (15.80) | 38.45 (15.81) | .09 | ||

| White race | 163 (89.56%) | 67 (84.81%) | 96 (93.20%) | .08 | ||

| IMM use | 67 (36.81%) | 31 (39.24%) | 36 (34.95%) | .64 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 72 (39.56%) | 26 (32.91%) | 46 (44.66%) | .127 | ||

| ACT-1 | n | 69 | 25 (36%) | 44 (64%) | ||

| Women | 25 (36%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 43.19 (13.47) | 42.24 (12.39) | 43.72 (14.16) | .65 | ||

| White race | 64 (93%) | 23 (92%) | 41 (93%) | 1 | ||

| IMM use | 27 (39%) | 10 (40%) | 17 (39%) | 1 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 26 (38%) | 6 (24%) | 20(45%) | .12 | ||

| ACT-2 | n | 65 | 28 (43%) | 37 (57%) | ||

| Women | 28 (43%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 40.56 (13.48) | 39.10 (13.72) | 41.67 (13.37) | .45 | ||

| White race | 60 (92%) | 24 (86%) | 36 (97%) | .16 | ||

| IMM use | 27 (42%) | 16 (57%) | 15 (41%) | .22 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 24 (37%) | 19 (68%) | 15 (41%) | .04 | ||

| PURSUIT-IM | n | 48 | 26 (54%) | 22 (46%) | ||

| Women | 26 (54%) | - | - | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 22.06 (12.08) | 21.69 (13.16) | 22.5 (12.38) | .83 | ||

| Mean BMI (SD) | 24.77 (5.42) | 24.13 (6.13) | 25.54 (4.45) | .36 | ||

| White race | 39 (81%) | 20 (77%) | 19 (86%) | .48 | ||

| IMM use | 13 (27%) | 9 (35%) | 4 (18%) | .33 | ||

| Corticosteroid use | 22 (46%) | 11 (42%) | 11 (50%) | .77 |

BMI data are available for PURSUIT-IM and PURSUIT-SC only. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IMM, immunomodulator.

Statistically significant.

Exposure Variable

Gender (woman, man), as determined based on self-report, was the primary exposure variable. The clinical trials included for this analysis did not collect information regarding patients’ sex at birth nor nonbinary gender data, so these data are not available, although we acknowledge the relevance.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was clinical remission, defined as a Mayo Clinic Score (MCS) < 3.10 Secondary outcomes included mucosal healing, defined as an endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1, and clinical response, defined as a decrease in MCS by ≥3 points and at least 30% from baseline, along with either a decrease from baseline in the rectal bleeding subscore ≥1 or a rectal bleeding subscore of 0 or 1. The MCS is a composite of the rectal bleeding score (graded 0–3), stool frequency (0–3), physician global assessment (0–3) and the endoscopic subscore (0–3). These definitions are consistent with those used in the clinical trials included in our study.

Covariates

We adjusted all analyses by age, race (White vs other races), MCS, concomitant use of immunomodulators (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, methotrexate), and concomitant use of systemic corticosteroids. We also included the study drug dose as a multilevel variable in individual trials’ models and, when available, body mass index (BMI) as a continuous variable. Covariate determination was based on data obtained at the time of screening for the native study inclusion.

Statistical Analysis

We performed univariable analyses to compare baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of men and women in the treatment arm in each trial, as well as to compare outcomes at the end of the induction period between men and women in each trial using chi-squared or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and t-tests for parametric continuous variables. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses to study the association of gender with each outcome in the treatment and the placebo arms of each trial after adjusting for covariates separately for induction and maintenance trials. For the latter analyses, we compared outcomes at week 30, as well as at week 54, to those at the end of induction (week 6 for golimumab and week 8 for infliximab). For PURSUIT-IM, we included the subset of patients who had been randomized and excluded the open-label extension subset of patients. We included the study drug dose in individual models but, given the lack of statistical significance of the associated estimate and heterogeneity of this variable across trials, we did not include it in the meta-analyses. Similarly, we included BMI in individual models but not in the meta-analysis, as data on this variable were not available consistently across trials. We then pooled estimates from relevant trials and conducted a meta-analysis for each outcome in the treatment and placebo arms of induction and maintenance trials using package mixmeta, available in R Cran.11,12 In order to account for the heterogeneity across different studies, a mixed-effect model was implemented. Both random and fixed effects were estimated via maximum likelihood estimation. A Cochran Q test was performed on the residuals of all the models estimated in this study. All models resulted in a P value from a Cochran Q test >.2, thereby rejecting the hypothesis of heterogeneity of the residuals. A P value ≤ .05 was considered significant for all analyses. The R Project for Statistical Computing (version 3.6.3) was utilized for all the analyses.12

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Totals of 1149 and 490 patients were included in the treatment and placebo arms, respectively. Of these, 476 (41%) and 220 (45%) were women, respectively. The mean age of women was slightly lower compared to that of men in the treatment arm (29.3 years [SD, 15.19 years] and 31.3 years [SD, 16.53 years], respectively; P = .037), but not in the placebo arm (28.0 years [SD, 15.04 years] and 30.2 years [SD, 16.78 years], respectively; P = .13). There were no statistically significant differences in race, immunomodulator use, or corticosteroid use among women, compared to men, in the 2 arms of pooled induction trials (Table 1).

After pooling data from the 3 maintenance trials, 1098 (n = 455, 41% women) and 182 (n = 79, 43% women) patients were included in the treatment and placebo arms, respectively. Age, race, immunomodulator use, and corticosteroid use were comparable between women and men in the treatment and placebo arms in the pooled maintenance trials (Table 1).

Individual Induction Trials Analyses

The estimates for each of the primary and secondary outcomes—clinical remission, mucosal healing, and clinical response—in the 3 individual induction trials were overall similar in magnitude and direction to those from the overall pooled analysis (Table S2).

The following results were discordant between the individual trials and the overall pooled analysis. For the treatment arm of ACT-1, there was no statistically significant association of gender with any of the 3 outcomes (clinical remission: aOR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.36–1.16]; mucosal healing: aOR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.30–1.10]; clinical response: aOR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.28–1.05] in men compared to women). In contrast, for the treatment arm in ACT-2, compared to women, men had significantly lower odds of each of the 3 outcomes. In the placebo arm of ACT-1, there was no difference in any outcome between men and women, while in the placebo arm of ACT-2, men had an 85% lower likelihood of clinical remission (aOR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03–0.84) and a 60% lower likelihood of clinical response (aOR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.16–0.98) compared to women.

Individual Maintenance Trials Analyses

In the analysis of the treatment arms of individual maintenance trials, in PURSUIT-IM, men had lower odds of clinical response compared to women (aOR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44–0.97), but the odds of clinical remission or mucosal healing at week 54 compared to week 6 were similar in men and women. In ACT-2, men had lower odds of mucosal healing in the maintenance phase compared to women (aOR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.21–0.96), but the odds of the other 2 outcomes were similar.

Otherwise, there was no statistically significant association of gender with any of the 3 outcomes across the individual maintenance trials in both treatment and placebo arms.

Meta-Analysis of Outcomes at the End of Induction

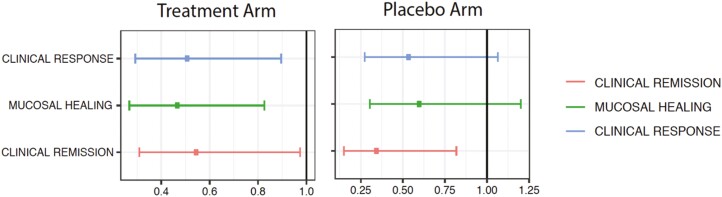

In the meta-analysis of estimates from the 3 induction trials data (PURSUIT-SC, ACT 1 and 2), men had lower adjusted odds of clinical remission, compared to women, in both the treatment and placebo arms after adjusting for age, race, MCS, systemic corticosteroid use, and immunomodulator use (aORs, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.31–0.97] and 0.34 [95% CI, 0.15–0.82], respectively; Figure 1). Men had lower adjusted odds of mucosal healing and clinical response at the end of the induction period, compared to women, in the treatment arm (aORs, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.27–0.83] and 0.51 [95% CI, 0.29–0.90], respectively) but not in the placebo arm (aORs, 0.60 [95% CI, 0.30–1.2] and 0.54 [95% CI, 0.27–1.1], respectively).

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratio for each outcome in male patients compared to female patients with ulcerative colitis, in a meta-analysis of tumor necrosis factor induction therapy trials data, after adjusting for age, race, Mayo score at screening, and concomitant systemic corticosteroid and immunomodulator use.

Meta-Analysis of Outcomes at Week 30 of Maintenance

In the meta-analysis of maintenance trials data (PURSUIT-IM, ACT 1 and 2), men and women had similar odds of clinical remission, mucosal healing, and clinical response at week 30 (vs at the end of induction) in the treatment and placebo arms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratio for each outcome in male patients compared to female patients with ulcerative colitis, in a meta-analysis of tumor necrosis factor maintenance therapy trials data, after adjusting for age, race, Mayo score at screening, and concomitant systemic corticosteroid and immunomodulator use.

| Study arm, time of outcome assessment | Outcome | Adjusted OR | 95% CI, LL | 95% CI, UL | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm, week 30 | Clinical remission | 0.9 | 0.51 | 1.6 | .72 |

| Mucosal healing | 0.66 | 0.36 | 1.2 | .18 | |

| Clinical response | 0.74 | 0.39 | 1.39 | .35 | |

| Placebo arm, week 30 | Clinical remission | 0.989 | 0.39 | 2.51 | .97 |

| Mucosal healing | 0.84 | 0.32 | 2.18 | .72 | |

| Clinical response | 0.68 | 0.24 | 1.9 | .46 | |

| Treatment arm, week 54 | Clinical remission | 0.99 | 0.51 | 1.92 | .97 |

| Mucosal healing | 0.79 | 0.39 | 1.61 | .52 | |

| Clinical response | 0.84 | 0.37 | 1.92 | .69 | |

| Placebo arm, week 54 | Clinical remission | 1.27 | 0.18 | 8.97 | .81 |

| Mucosal healing | 0.85 | 0.22 | 3.23 | .81 | |

| Clinical response | 0.34 | 0.07 | 1.68 | .18 |

Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; OR, odds ratio; UL, upper limit.

Meta-Analysis of Outcomes at Week 54 of Maintenance

In the meta-analysis of estimates at week 54 compared to at the end of induction (PURSUIT-IM and ACT 1), men and women had similar adjusted odds of clinical remission, mucosal healing, and clinical response in the treatment and placebo arms (Table 2).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of individual patient–level data from randomized clinical trials of UC induction and maintenance treatment with TNFi, we demonstrated that there are gender-based differences in therapeutic endpoints. Specifically, men have a significantly lower likelihood of clinical remission compared to women with UC. Interestingly, this same pattern was seen in the placebo arm during induction. The odds of mucosal healing and clinical response with induction TNFi therapy were significantly lower in men, compared to women, with UC in the treatment arm, but not in the placebo arm. Furthermore, when looking at TNFi maintenance therapies, we found no difference in the odds of clinical remission, mucosal healing, or clinical response by gender, both at week 30 and at week 54, compared to at the end of induction. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate gender-based differences in response to TNFi therapy, including a difference in the responses to induction and maintenance therapies.

The assessment of clinical remission is subjective, as it involves patient-reported symptoms, and it is well established that there is a limited correlation with mucosal healing, a more objective measure of inflammation.13 Our observation that men have lower odds of clinical remission compared to women in both treatment and placebo arms may suggest differences in subjective perception by gender. Furthermore, the overall difference in clinical remission between men and women in the placebo arm is driven primarily by the data in ACT 2. The odds of mucosal healing were lower in men compared to women in the treatment arm, but not in the placebo arm, suggesting an underlying difference in biological pathways. For each of the 3 outcomes, while the magnitude of the effect estimates varied, directionality was maintained. The effect estimates for both TNFi agents that we studied, golimumab and infliximab, were comparable, providing additional corroboration.

Previous studies on the impact of gender on responses to IBD therapies are rare and heterogenous. Based on a single-center, retrospective study of 125 patients with corticosteroid-refractory UC, Nasuno et al5 reported that women had a higher likelihood of clinical remission at 1 year compared to men on treatment with infliximab, although with a wide CI (OR, 3.46; 95% CI, 1.41–8.46). Conversely, in a retrospective study of 210 patients with IBD, men were more likely to have an early and sustained clinical response to TNFi therapy compared to women, although these findings pertained to CD and not UC. Furthermore, the investigators did not report endoscopic outcomes.6 Differences in adherence to IBD therapy have been reported based on gender, although with lower adherence in women.14 However, because randomized controlled clinical trials are organized to have regular monitoring and close follow-up, nonadherence is less likely compared to in nonclinical trials; as such, gender-based differences in adherence are less likely to significantly confound our observations.

Our findings of gender-based differences in clinical and endoscopic endpoints after induction therapy, but no difference after maintenance therapy, may suggest underlying mechanisms that relate more to the pharmacokinetics than the pharmacodynamics of TNFi therapy. To this end, we considered BMI in our analysis, given the potential for confounding; however, our findings were maintained even after adjusting for BMI, suggesting that differences in BMI between men and women do not fully account for the observed lower response in men versus women, at least for the golimumab trials. Although the lack of height data in the infliximab trials precluded a BMI adjustment for these analyses, BMI may be less relevant due to the weight-based dosing of infliximab. Comparable results despite a difference in the modes of administration of golimumab (subcutaneous) and infliximab (intravenous) is also worth noting. Differences in immunogenicity to TNFi among men and women may also impact drug clearance, and this should be explored as a possible contributing factor underlying our observations. Lastly, selection bias, caused by inclusion in maintenance trials of only those patients who responded to induction therapies, may further explain null findings on analyses of maintenance trials. The impacts of gender on outcomes with maintenance TNFi therapy in an unselected cohort outside of the clinical trial setting will be informative.

In adjusted analyses of individual trials’ data, compared to women, men had a lower likelihood of achieving the primary and secondary outcomes in PURSUIT-SC and ACT 1, but there was a null association between gender and these outcomes in ACT 2, albeit with consistent directionality of the effect estimate. While in ACT 1 the inclusion criteria were failure of corticosteroids or immunomodulators, in ACT 2 patients who failed 5-aminosalicylates were also included.15 This latter group may represent patients with less severe disease and a higher placebo response. It is also possible that unmeasured or random variability could account for these findings.

X-linked IBD susceptibility genes and other sex-based genetic differences have been reported in individuals with IBD.16,17 Estrogen metabolism is implicated in IBD pathogenesis, with a protective role of estrogen receptor β against colitis in female mice,18 and impacts on immune regulation in the gut.19 Sex-based differences in intestinal and peripheral immune populations have been reported in mouse models of colitis.20 Similar differences have also been reported in other immune-mediated diseases. In a study of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, there were significant differences in T-cell subsets by sex, correlating with disease activity in male patients but not in female patients.21 In a mouse model study, female mice had more severe collagen-induced arthritis compared to male mice, and this finding was believed to be related to differences in monocyte lineage cells and higher levels of inflammatory cytokines.22 While these data emphasize sex-based differences in immunological pathways, they may have relevance in driving the therapeutic response. Dedicated investigation is needed to delineate the exact mechanisms underlying the significant findings in our study.

Our study has several strengths. These novel observations are based on individual patient–level clinical trial data from 3 different randomized clinical trials of 2 different TNFi with a large overall sample size. Unlike administrative data, these have been collected for the purpose of clinical research, and therefore have high accuracy with minimal risks of missing data or misclassification. As these data are from randomized clinical trials, the risks of bias and confounding are also lower, although randomization was based on treatment versus placebo arms. There are some limitations of our study as well. These are pooled data with potential unmeasured heterogeneity and differences in study populations. We were not able to include disease duration; biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, and albumin, due to a lack of consistent reporting across studies; or clinical trials data on adalimumab, another subcutaneous TNFi, due to a lack of availability through the YODA platform. Endoscopic data were not centrally read in the included trials. Additionally, we do not have data on histological outcomes. However, the results were consistent across individual trials, pooled analyses, and outcomes.

In conclusion, based on a pooled analysis of data from RCTs, men with UC are less likely than women to achieve mucosal healing, clinical remission, and clinical response during induction treatment with TNFi, although there do not appear to be gender-based differences after the induction phase. Gender-based differences in clinical remission to placebo may implicate possible nonbiological determinants, in addition to biological determinants. Future studies delineating the mechanisms underlying these observations would be informative and have the potential to impact clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study, carried out under Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project 2018-3737, used data obtained from the YODA Project, which has an agreement with Janssen Research & Development, LLC. The interpretation and reporting of research using these data are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the YODA Project or Janssen Research & Development, LLC.

Contributor Information

Manasi Agrawal, The Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; Center for Molecular Prediction of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (PREDICT), Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Francesca Petralia, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; Icahn Institute for Data Science and Genomic Technology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Adam Tepler, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

Laura Durbin, Kantar, Health Division, New York, NY, USA.

Walter Reinisch, Department Internal Medicine III, Division Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Jean-Frederic Colombel, The Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Shailja C Shah, Gastroenterology Section, VA San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, CA, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Author Contributions

S.C.S.: accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study and is the guarantor of the article. M.A., S.C.S.: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. F.P.: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. A.T., L.D.: search strategy design and execution and data management. W.R.: interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.-F.C.: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, including the authorship list.

Funding

M.A. is supported by the NIH K23 career development award (K23DK129762-01).

Conflicts of Interest

The corresponding author confirms on behalf of all authors that there have been no involvements that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or in the conclusions, implications, or opinions stated. W.R. has served as a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Aptalis, Astellas, Centocor, Celltrion, Danone Austria, Elan, Falk Pharma GmbH, Ferring, Immundiagnostik, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Otsuka, PDL, Pharmacosmos, PLS Education, Schering-Plough, Shire, Takeda, Therakos, Vifor, and Yakult; served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Algernon, Amgen, AM Pharma, AMT, AOP Orphan, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Avaxia, Roland Berger GmBH, Bioclinica, Biogen IDEC, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cellerix, Chemocentryx, Celgene, Centocor, Celltrion, Covance, Danone Austria, DSM, Elan, Eli Lilly, Ernest & Young, Falk Pharma GmbH, Ferring, Galapagos, Gatehouse Bio Inc., Genentech, Gilead, Grünenthal, ICON, Index Pharma, Inova, Intrinsic Imaging, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Landos Biopharma, Lipid Therapeutics, LivaNova, Mallinckrodt, Medahead, MedImmune, Millenium, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Nash Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis, Ocera, OMass, Otsuka, Parexel, PDL, Periconsulting, Pharmacosmos, Philip Morris Institute, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Prometheus, Protagonist, Provention, Quell Therapeutics, Robarts Clinical Trial, Sandoz, Schering-Plough, Second Genome, Seres Therapeutics, Setpointmedical, Sigmoid, Sublimity, Takeda, Teva Pharma, Therakos, Theravance, Tigenix, UCB, Vifor, Zealand, Zyngenia, and 4SC; served as an advisory board member for Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Amgen, AM Pharma, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Avaxia, Biogen IDEC, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cellerix, Chemocentryx, Celgene, Centocor, Celltrion, Danone Austria, DSM, Elan, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech, Grünenthal, Inova, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Lipid Therapeutics, MedImmune, Millenium, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Nestle, Novartis, Ocera, Otsuka, PDL, Pharmacosmos, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Prometheus, Sandoz, Schering-Plough, Second Genome, Setpointmedical, Takeda, Therakos, Tigenix, UCB, Zealand, Zyngenia, and 4SC; and received research funding from Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Centocor, Falk Pharma GmbH, Immundiagnostik, Janssen, MSD, Sandoz, and Takeda. J.-F.C. has received research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Takeda; has received payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Inc. Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Takeda; has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Enterome, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Landos, Ipsen, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Tigenix, and Viela Bio; and holds stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development and Genfit.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article.

References

- 1. Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, et al. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shah SC, Khalili H, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Sex-based differences in incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases-pooled analysis of population-based studies from Western countries. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1079–1089.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shah SC, Khalili H, Chen CY, et al. Sex-based differences in the incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases-pooled analysis of population-based studies from the Asia-Pacific region. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:904–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nasuno M, Miyakawa M, Tanaka H, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis and related prognostic factors: a single-center retrospective study. Digestion. 2017;95:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprakes MB, Ford AC, Warren L, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: a large single centre experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Favalli EG, Biggioggero M, Crotti C, et al. Sex and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:333–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, et al. Treatment response, drug survival, and predictors thereof in 764 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The YODA Project. 2020. https://yoda.yale.edu [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317: 1625–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sera F, Armstrong B, Blangiardo M, et al. An extended mixed-effects framework for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2019;38:5429–5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laganà B, Zullo A, Scribano ML, et al. Sex differences in response to TNF-inhibiting drugs in patients with spondyloarthropathies or inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vermeire S, Satsangi J, Peeters M, et al. Evidence for inflammatory bowel disease of a susceptibility locus on the X chromosome. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Biank V, Friedrichs F, Babusukumar U, et al. DLG5 R30Q variant is a female-specific protective factor in pediatric onset Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goodman WA, Havran HL, Quereshy HA, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha loss-of-function protects female mice from DSS-induced experimental colitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5: 630–633.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodman WA, Garg RR, Reuter BK, et al. Loss of estrogen-mediated immunoprotection underlies female gender bias in experimental Crohn’s-like ileitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elderman M, van Beek A, Brandsma E, et al. Sex impacts Th1 cells, Tregs, and DCs in both intestinal and systemic immunity in a mouse strain and location-dependent manner. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aldridge J, Pandya JM, Meurs L, et al. Sex-based differences in association between circulating T cell subsets and disease activity in untreated early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dimitrijević M, Arsenović-Ranin N, Bufan B, et al. Sex-based differences in monocytic lineage cells contribute to more severe collagen-induced arthritis in female rats compared with male rats. Inflammation. 2020;43:2312–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article.