Abstract

Objectives

Analyze the relationship between family styles and quality of life (QoL) in adolescents with bronchial asthma and study the influence of self‐esteem as a protective factor and threat perception as a risk factor.

Methods

Family styles, QoL, perceived threat of the disease, and self‐esteem were assessed in a total of 150 adolescents diagnosed with bronchial asthma with ages ranging from 12 to 16 years (M = 13.28; SD = 1.29), 60.7% being male. Descriptive statistics and mean comparisons were conducted according to the level of self‐esteem. Relationships between variables were also studied using Pearson's correlations, and finally, the mediating role of self‐esteem and the perceived threat of the disease was assessed using PROCESS.

Results

Adolescents shown healthy family characteristics (high scores on affect and parental mood and low scores on psychological control) and high scores on QoL. Thirty‐five percent of adolescents showed low self‐esteem and a tendency to underestimate the disease. There are existing relationships between family styles and QoL; thus, healthy family characteristics (affection, parental mood, autonomy promotion) were positively associated with QoL, while psychological control was negatively associated with QoL. Disease threat and self‐esteem mediated the relationship between family styles and adolescent QoL. Disease threat was negatively, and self‐esteem was positively associated with QoL.

Conclusions

Self‐esteem and family support are protective factors for the well‐being of adolescents with bronchial asthma; however, the high perceived threat of the disease can have negative consequences for the adolescent's health and negatively impact their QoL.

Keywords: adolescence, bronchial asthma, family styles, quality of life, self‐esteem, threat

1. INTRODUCTION

Adolescents with bronchial asthma (BA), compared to their healthy peers, 1 report poorer perceived health and a more significant number of interferences in their ability to enjoy regular daily physical activity in their lives and increased deterioration in their psychological health. Moreover, this difference becomes more acute when adolescents with asthma are symptomatic, as they show greater limitations in their physical functioning, more missed school days, and greater psychological difficulties. 2 For these reasons, research shows that patients with asthma have a poorer health‐related quality of life (QoL) than their healthy peers. 3 In this regard, it is essential to consider several factors that may modulate the psychological impact of BA on the well‐being of adolescents. According to studies, 4 , 5 , 6 these factors could be grouped into intrapersonal variables (temperament or problem‐solving skills), social ecology (family environment, social support, and community resources), and the patient's coping skills (cognitive appraisal and coping strategies).

It has also been studied how the early onset of asthma allows patients to adapt and cope better with the disease, showing better QoL. When they reach adolescence, these patients and their parents seem to perceive asthma as less threatening and a more common and manageable disease than other chronic diseases. Thus, adolescents whose asthma was diagnosed earlier (having lived with it for a more extended period) seem to feel less anxiety and show greater coping and management skills than adolescents with recently diagnosed asthma. 7

Self‐esteem is another variable that best represents the impact of chronic disease, given the physical and social limitations that the disease entails. 8 Studies demonstrate that chronic diseases are a risk factor for low self‐esteem. 8 , 9 , 10 Some studies suggest that patients with asthma have a lower self‐concept and self‐esteem than adolescents without asthma. 8 However, other studies find no differences in self‐esteem between non‐asthmatic and asthmatic individuals. 11 On the other hand, recent research indicates that patients with asthma have better self‐esteem than their healthy peers. This could be explained by the fact that they receive greater attention from their parents and teachers, which can positively reinforce their self‐image. 12 Therefore, there is still no conclusive data on the differential impact of chronic asthma on self‐esteem in young people. During adolescence, high self‐esteem can generally be considered a protective variable, but its facilitating role is even more critical in adapting to the disease and reducing suffering. 13 In addition, self‐esteem appears to be a significant predictor of perceived QoL in patients with asthma. 14

Several studies indicate that, for asthmatic patients, asthma symptoms represent the worst component of their disease. In addition, the effects of this disease would represent a moderate emotional discomfort for them.

Few adolescents, however, report that their asthma is a significant disruption to their lives, 15 tending to underestimate the impact of their disease. In this sense, young asthmatics who are also coping with the everyday stressful situations associated with adolescence may be at risk of ignoring or denying their condition and, in some cases, engaging in potentially risky behaviors. 16 Despite the problems associated with this type of adjustment, studies on the perceived threat of the disease in asthma do not adequately address this risk factor, focusing mainly on analyzing the representations of the disease (symptoms, duration, consequences, control, and treatments) by the caregivers. 17 Few studies have looked at possible gender differences in adolescent illness threat. Although research seems to report that girls perceive the disease as more threatening. 18 , 19

Throughout childhood and adolescence, good asthma self‐management will be essential. To this end, the adolescent must achieve good treatment adherence and adequate use of asthma medication devices. Studies highlight the importance of family support in treatment adherence in patients with asthma. It has been observed that adolescents with a lack of parental supervision have a higher level of adherence complications and poor asthma control. Furthermore, along the same lines, studies suggest that parental energy, involvement, and willpower are good predictors in the development of adherence in adolescents with asthma. 20 , 21 The studies 22 point out that familial cohesion, communication, organization, and control are family characteristics associated with children's mental health. Adolescents with asthma in families with positive communication dynamics had a better QoL related to the disease than those living in more conflictive families. There is no record of analysis of gender differences in perceived family styles. It is observed that family characteristics such as the promotion of autonomy or affection and communication promote well‐being in adolescents and other factors such as behavioral control or psychological control have a negative impact. 23

The role of the family changes throughout the everyday life of the adolescent, and a progressive increase in their autonomy and independence is advisable for them (whether or not they have asthma). However, a certain degree of family involvement in the self‐management of the disease can be considered a determining factor in the QoL of the adolescent with asthma. 24 The family provides the main developmental environment for adolescents and, therefore, is where most of the elements associated with asthma management and control occur. The challenges of controlling asthma in adolescents can place significant pressure on families, as it introduces additional responsibilities, which can negatively affect the QoL of family members (including adolescents) and their psychological well‐being. In addition, increased family stress and the resulting relational environment are negatively associated with treatment adherence and child health. 25 , 26 Furthermore, the results suggest that the combination of positive characteristics (i.e., adequate cohesion, support for expressiveness [disclosure], and low conflict, not excessive rules and control) can help promote children's optimal psychosocial functioning, boosting their self‐esteem, and having a positive impact on their QoL. 22 , 27 Although more research is needed, especially to assess the influence of the family on self‐esteem.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the relationship between family styles through family characteristics (affection and communication, autonomy promotion, psychological and behavioral control, parental mood) and QoL in adolescents with BA and to study the influence of self‐esteem as a protective factor and the perceived threat as a risk factor. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed: H1. Healthy family styles will be positively associated with QoL and self‐esteem, and negatively associated with the perceived threat of the disease. H2. Adolescent QoL will be positively associated with self‐esteem and negatively associated with the perceived threat of the disease. H3. Self‐esteem and perceived threat level will have a mediating role in the relationship between family styles, QoL, and the adjustment to the disease of the adolescent with BA.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

A total of 150 adolescents with BA, aged between 12 and 16 years (M = 13.28; SD = 1.29), with 60.7% male and 39.3% female. Of the adolescents with BA, 86% had controlled asthma for at least 6 months, compared to 14% with uncontrolled asthma. Regarding the severity of asthma: 60.4% had persistent‐moderate asthma, 32.3% had frequent episodic asthma, 6% had occasional episodic asthma, and 1.3% had severe asthma.

2.2. Design and procedure

It is a single‐pass cross‐sectional design. The procedure identified all patients with BA who attended pediatric pulmonology consultations at the hospital. For pediatric patients, the inclusion criteria were that they were aged between 12 and 16 years and had been diagnosed with BA at least 6 months ago.

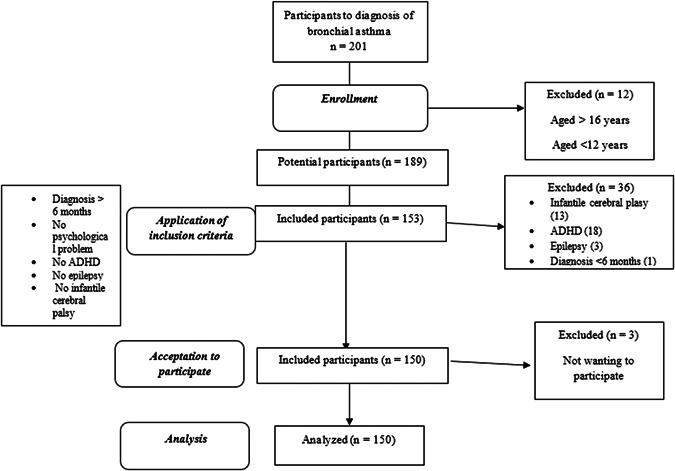

Participants who met these diagnostic criteria and agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form were included. As an exclusion criterion, those patients with BA who, despite meeting the requirements, had a previously diagnosed physical or psychological pathology, or cognitive difficulties, were excluded (Figure 1). All included patients answer 100% of the questionnaires. The present study was approved by the UV‐INV_ETICA‐1226194 ethics committee.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selection and participation in the study

According to ISAAC in Spain in 2005 28 there were about 3000 adolescents with asthma. By choosing a 90% confidence level and a sample size of 150 participants the margin of error would be ±5.84%, which is acceptable.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. QoL

The Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire was used to assess health‐related QoL in its self‐administered version translated into Spanish. 29 In the present study, a new version adapted and validated for patients with pediatric chronic disease (9−18 years) was used, 30 showing adequate reliability indices 85 for the total scale.

2.3.2. Threat of illness

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire was used: A measure of patients' cognitive and emotional representations of their illness. 31 , 32 A new version adapted and validated for adolescents (9−16 years) was used. 33 The results of the internal consistency analyses performed indicate good quality indeces. 32 , 34 In the present study, the reliability was 80.

2.3.3. Self‐esteem

The Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale was used. 35 , 36 The scale consists of 10 items with content that focuses on feelings of self‐respect and self‐acceptance. In the original study, 36 reliability of 92 was obtained.

2.3.4. Family styles

The Parental Styles questionnaire was used. 23 This scale was created to evaluate adolescents' perception of their parents' family functioning style through six dimensions that characterize their parents' educational style. The original scale showed adequate reliability indices. 23 In the present study, 88 for affect and communication, 85 for autonomy promotion, 80 for behavioral control, 82 for psychological control, 77 for disclosure, and 86 for parental mood.

2.4. Data analyses

First, descriptive statistics were performed, comparing means according to self‐esteem through analysis of variance factor, and finally, the variables were related using Pearson's correlation. For this, the SPSS v26 statistical program was used. To analyze the mediating effect that self‐esteem and the perceived threat of the disease could have on the relationship between family variables and QoL, the PROCESS macro was used. 37

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics

3.1.1. QoL

The results on the QoL scale related to health showed a good overall QoL for these patients. A higher score represents a better QoL. As shown in Table 1, all the scores are above 3.5, which suggests that adolescents with BA do not display major interferences in their QoL in their everyday lives. However, the most affected dimensions would be emotional functioning (experiencing emotions of nervousness, sadness) and feelings of fatigue or tiredness.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for QoL and family styles in adolescents with BA

| M | SD | P25 | P50 | P75 | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea | 6.70 | 0.61 | 6.50 | 7 | 7 | 1−7 |

| Fatigue | 5.34 | 1.10 | 4.75 | 5.63 | 6 | 1−7 |

| Emotional function | 5.34 | 1.16 | 4.50 | 5.50 | 6.33 | 1−7 |

| Disease control | 6.01 | 1.09 | 5.33 | 6.33 | 6.92 | 1−7 |

| Total QoL | 5.85 | 0.79 | 5.38 | 6.04 | 6.45 | 1−7 |

| Affect and communication | 41.99 | 5.64 | 39 | 43 | 46 | 16−48 |

| Autonomy | 38.18 | 7.23 | 34 | 39.50 | 43 | 11−55 |

| Behavioral control | 29.20 | 5.53 | 26 | 30 | 34 | 12−36 |

| Psychological control | 19.93 | 7.77 | 14 | 18 | 25 | 6−30 |

| Disclosure | 22.68 | 5.21 | 19 | 24 | 26.75 | 6−30 |

| Parental mood | 30.23 | 4.95 | 28 | 31 | 34 | 11−36 |

Note: Dyspnea: refers to the adolescent's subjective feeling of shortness of breath or difficulty breathing in everyday activities. Fatigue: a feeling of increased physical exhaustion in relation to their asthma. Emotional factor: emotional impact of the disease, assesses whether in the last few weeks he/she has experienced any type of emotion (anger, nervousness). Disease control: assesses the degree of control perceived by the adolescent. Whether or not they feel they can manage the presence of symptomatology. Affection and communication: measure the expression of support and affection that adolescents receive from their parents, the feeling of availability and the fluidity of communication between them. Autonomy promotion: reflects the extent to which parents encourage their children to develop their own ideas and make decisions for themselves. Behavioral control: assesses the extent to which parents set limits and try to stay informed about their children's activities and behaviors outside the home. Too much in adolescence is negative. Psychological control: use of psychological manipulation strategies such as emotional blackmail or guilt inducement is a negative dimension. Disclosure: use of psychological manipulation strategies such as emotional blackmail or guilt‐inducing, this being a negative dimension. Humor: how adolescents perceive their parents as optimistic, relaxed, and with a good sense of humor.

Abbreviations: BA, bronchial asthma; M, mean; P25, 25 percentile; P50, 50 percentile; P75, 75 percentile; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

3.1.2. Perceived threat of the disease

The results on the perceived threat of the disease indicated low threat perception scores, obtaining mean scores of 3.73 (SD = 1.93; Range 0−10). However, this low threat perception may be due to a lack of knowledge or an underestimation of their asthma. In this sense, when the adolescents were asked about the main factors or causes related to their disease, 63% of the patients did not know what caused their asthma, the rest of the causes reported were: 15% respiratory problems from birth, 10% due to allergy, 9% due to genetic issues, and 3% were due to chance.

3.1.3. Self‐esteem

Considering that the total score ranges from 10 to 40 points, making a distinction between low self‐esteem (scores equal or lower than 25), average (from 26 to 29), and high (equal or higher than 30), 35% of the asthmatic adolescents reported low high self‐esteem, 40% average, and 25% high self‐esteem.

3.1.4. Family styles

The results obtained in the scales of “affection and communication,” “autonomy promotion,” “behavioral control,” “psychological control,” “self‐disclosure,” and “parental mood,” through which the perception of adolescents about their parents was evaluated, are shown in Table 1.

Considering the range of scores for each scale, average‐high values were obtained in the different subscales, except for “psychological control” and “self‐disclosure” subscales, whose scores were lower. These data, in general, indicate functional family styles since they foster an affective relationship, with an open attitude toward expression and communication, with complicity and with low levels of guilt, but with a degree of control over norms and limits.

3.2. Mean comparison based on self‐esteem levels

When analyzing the differences in QoL and family styles according to self‐esteem levels (high, average, and low) (Table 2), differences in the total QoL were observed between the average and high self‐esteem groups (F 142 = 9.41; p ≤ 0.001; η² = 0.12), with the high self‐esteem group scoring higher in QoL. In addition, in the subdimensions of fatigue (F 142 = 10.61; p ≤ 0.001; η² = 0.13) and emotional functioning (F 142 = 11.21; p ≤ 0.001; η² = 0.14), differences between the three self‐esteem groups were found, with the high self‐esteem group scoring higher in QoL for these dimensions.

Table 2.

Comparison of means as a function of self‐esteem in the study variables

| Low self‐esteem M (SD) | Average self‐esteem M (SD) | High self‐esteem M (SD) | F | η² | Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea | 6.75 (0.43) | 6.53 (0.76) | 6.75 (0.57) | 1.47 | 0.02 | ‐ |

| Fatigue | 4.20 (1.44) | 4.72 (1.19) | 5.55 (0.97) | 10.61*** | 0.13 | Low‐high average‐high |

| Emotional function | 4.23 (1.17) | 4.64 (1.31) | 5.58 (1.02) | 11.21*** | 0.14 | Low‐high average‐high |

| Disease control | 6.01 (0.60) | 5.57 (1.36) | 6.11 (1.01) | 2.94 | 0.04 | ‐ |

| Total QoL | 5.31 (0.32) | 5.37 (0.89) | 6 (0.72) | 9.41*** | 0.12 | Average‐high |

| Perceived threat of illness | 22.40 (6.02) | 24.07 (9.71) | 17.19 (9.25) | 6.76** | 0.09 | Average‐high |

| Affect and communication | 41.60 (4.16) | 39.90 (7.38) | 32.55 (4.99) | 2.62 | 0.04 | ‐ |

| Autonomy | 39.80 (4.09) | 26.69 (9.04) | 38.50 (6.74) | 0.85 | 0.01 | ‐ |

| Behavioral control | 23 (9.54) | 28.44 (6.74) | 29.57 (4.93) | 2.43 | 0.04 | ‐ |

| Psychological control | 24.40 (7.23) | 23.38 (8.40) | 18.80 (7.28) | 4.95** | 0.07 | Average‐high |

| Disclosure | 20.75 (3.30) | 20.57 (5.34) | 23.34 (5.09) | 3.56* | 0.05 | Average‐high |

| Parental mood | 26.20 (4.87) | 28.86 (5.92) | 30.78 (4.52) | 3.58* | 0.05 | Average‐high |

Abbreviations: ES, effect size; F, variation between sample means/variation within the samples; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; η² partial squared eta, small η² ≈ 0.02; medium η² ≈ between 0.15 and 0.3; high η² ≈ 0.3.

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

Regarding family variables, differences were found between the average and high self‐esteem groups, in the subscales of psychological control (F 139 = 4.95; p ≤ 0.01; η² = 0.07), disclosure (F 136 = 3.56; p = 0.03; η² = 0.05), and parental mood (F 142 = 3.58; p = 0.03; η² = 0.05) with adolescents with higher self‐esteem presenting healthier profiles.

Finally, it was found that the high self‐esteem group scored lower on the perceived threat of the disease compared to the average self‐esteem group (F 145 = 6.76; p = 0.002; η² = 0.09).

3.3. Relationship between the variables studied

The relationship between the variables studied indicates that QoL was positively related to healthy family styles, as shown in Table 3. Thus, when there were higher scores in affection and communication, autonomy promotion, lower scores in psychological control, and high scores in self‐disclosure and mood, this was positively associated with the QoL of the adolescent with BA. On the other hand, self‐esteem was positively associated with healthy family styles, QoL, and its subdimensions. Finally, the perceived threat of the disease was negatively related to the QoL, self‐esteem, and healthier family styles.

Table 3.

Relationship between quality of life and family styles with disease threat and self‐esteem

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea | 1 | |||||||||||

| Fatigue | 0.42*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Emotional function | 0.33*** | 0.71*** | 1 | |||||||||

| Control | 0.62*** | 0.50*** | 0.48*** | 1 | ||||||||

| Threat | −0.32*** | −0.42*** | −0.42*** | −0.57*** | 1 | |||||||

| Affection and communication | 0.10 | 0.21** | 0.22** | 0.13 | −0.19* | 1 | ||||||

| Autonomy promotion | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.19* | −0.11 | 0.65*** | 1 | |||||

| Behavioral control | −0.13 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.29*** | 0.15 | 1 | ||||

| Psychological control | −0.11 | −0.20* | −0.25* | −0.27** | 0.28*** | −0.38*** | −0.48*** | 0.09 | 1 | |||

| Disclosure | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.24** | 0.56*** | 0.50*** | 0.30*** | −0.33*** | 1 | ||

| Parental mood | 0.23** | 0.28*** | 0.28* | 0.20* | −0.26** | 0.69*** | 0.62*** | 0.26** | −0.40*** | 0.57*** | 1 | |

| Self‐esteem | 0.09 | 0.39*** | 0.34*** | 0.20* | −0.21** | 0.26** | 0.21** | 0.14 | −0.35*** | 0.25** | 0.28*** | 1 |

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001.

3.4. Mediation models between family styles and QoL

Two mediation models were conducted to observe whether the psychological variables of self‐esteem and the perceived threat of the disease exerted a mediating effect in predicting the QoL of adolescents with BA. The variables that showed the highest number of associations with the other variables (psychological control and parental mood) were selected for the models. For this purpose, mediation was tested by directly assessing the importance of the indirect effect of the independent variable (in this study, the adolescent's family variables were used) through two mediating variables (self‐esteem and threat of disease).

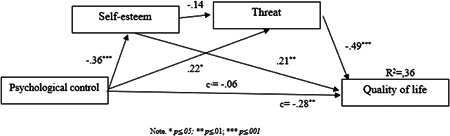

Figure 2 shows the standardized parameter estimates. Psychological control had a direct negative effect on self‐esteem (β = −0.36) and a positive effect on the perceived threat of the disease (β = 0.22), explaining 37% and 30% of its variance. Psychological control had a direct negative effect on the QoL (β = −0.28). In turn, self‐esteem had a direct positive effect on the QoL (β = 0.21), and perceived threat of the disease had a direct negative effect (β = −0.49). β are the standardized partial regression coefficients. The indirect effects of psychological control on the patient's QoL were assessed through self‐esteem and perceived disease threat. It was observed that the indirect effects of psychological control on the QoL through self‐esteem were significant (Effect = −0.01; CI = [−0.02 to −0.01]) as were those of perceived threat of disease (Effect = −0.01; CI = [−0.02 to −0.01]). However, the mediating role of the two mediating variables (self‐esteem and perceived threat of the disease) together was not significant (Effect = −0.01; CI = [−0.01 to 01]). Overall, the direct and indirect effects predicted a total variance of 36%, but when introducing the two mediating variables together, the relationship between psychological control and QoL disappeared; thus, there was total mediation. Full mediation implies the relationship between psychological control and QoL would be explained by mediating variables.

Figure 2.

Double moderation analysis of psychological control on quality of life

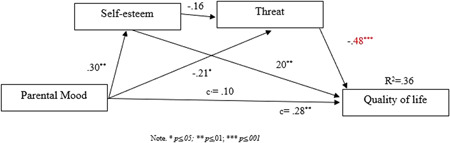

The same procedure was repeated for the parental mood variable (Figure 3); the results showed that parental mood had a direct positive effect on self‐esteem (β = 0.30) and a negative effect on perceived disease threat (β = −0.21) explaining 30% of the variance. Psychological control had a direct positive effect on the QoL (β = 0.28). Likewise, self‐esteem had a direct positive effect on the QoL (β = 0.20), whereas the perceived threat of the disease had a direct negative effect (β = −0.48). The indirect effects of parental mood on patient QoL were tested through self‐esteem and perceived disease threat. It was observed that the indirect effects of parental mood on the QoL through self‐esteem were significant (effect = 0.01; CI = [0.02−06]), as well as for the perception of disease threat (effect = 0.02; CI = [0.01−03]), however, for the mediation of the two mediating variables (self‐esteem and perceived threat of the disease) together, it was not significant (effect = 0.01; CI = [−0.01 to 01]). Overall, the direct and indirect effects predicted a total variance of 36%, but when the two mediating variables were introduced together, the relationship between parental mood and QoL disappeared, resulting in total mediation. Full mediation implies the relationship between parental mood and QoL would be explained by mediating variables.

Figure 3.

Double moderation analysis of the relationship of parental mood on quality of life

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between family styles and QoL in adolescents with BA and to evaluate the influence of self‐esteem as a protective factor and perceived threat as a risk factor. Regarding Hypothesis 1, the family system is where attitudes and beliefs are acquired, with many parents transmitting to their children the idea that if there are no symptoms, there is no asthma, which reduces treatment adherence and negatively impacts their QoL. 17 As such, healthy family styles promote greater self‐esteem and therefore, also positively impact the QoL of the adolescent with BA. The results found in the relationships between variables indicate that high patient QoL is associated with healthy family styles (low psychological control and high mood scores) as indicated by previous studies that family support in promoting better adjustment or adaptation to the disease. 20 , 22

Concerning Hypothesis 2, the QoL of the adolescent with BA would be explained by high scores in self‐esteem, low threat perception of the disease, and healthy family characteristics (high scores in affection and communication, promotion of autonomy, and low scores in psychological and behavioral control). The results found in the relationships between variables indicate that high patient QoL is associated with high scores in self‐esteem as indicated by previous studies that discuss the protective role of self‐esteem 8 , 23 , 38 Self‐esteem is one of the variables considered to be protective, as it facilitates adaptation to the disease and reduces the emotional impact 13 and is a good predictor of the QoL of the adolescent with asthma. 14 On the other hand, risk factors such as the threat of the disease can negatively influence the QoL. The results found indicate that greater perception of disease threat would be associated with lower levels of QoL. This would be in line with previous studies. In adolescence, mental and physical health are closely related, possibly more so than in other life cycle stages. Moreover, the representation of illness constructed by the adolescent 33 influenced by the causes, duration expectations, short‐ and long‐term consequences, and their idea of control, influence the level of threat perceived by adolescents. Previous studies have indicated that when the threat level is high, it is associated with a poorer QoL because there is uncertainty as to when the next crisis may occur or what alterations it may generate in their lives. 15 Given the above, Hypothesis 2 would be accepted.

Finally, Hypothesis 3 proposed that self‐esteem and the level of disease threat would play a mediating role in the relationship between family styles and adjustment to the disease in adolescents with BA. Previous research has highlighted the role of self‐esteem 10 , 11 as a protective variable in emotional adjustment, both in patients with BA and in adolescents in general. Furthermore, the representation of the disease and its perceived threat directly affects the adjustment of the adolescent with BA. 33 When testing whether these variables mediated the relationship between family variables and QoL, it was found that both self‐esteem as a protective factor and the perception of threat as a risk factor did indeed mediate between family characteristics (psychological control and parental mood) and QoL, with full mediation, that is, the relationship between how family variables influence the QoL of adolescents with BA, explained through self‐esteem and the adolescent's threat perception. Through the correlations found and the mediation models, it can be concluded that one of the family variables most closely related to the adjustment of the adolescent with BA is parental psychological control, that is, the use of emotional blackmail, which hinders the satisfaction of the adolescent's psychological and emotional needs. Therefore, given the influence of self‐esteem and the perceived threat of the disease, it would be advisable to assess these aspects when designing intervention programs that aim to improve the patient's QoL and ensure adequate emotional adaptation to the disease by accepting H3.

The contributions presented are that while the importance of the family in the QoL is evident, other variables can mediate this relationship. However, this study is not without limitations, and it would be advisable to extend the sample to a more significant number of participants (patients) to gain a deeper understanding of the influence of other variables such as gender, asthma control or severity of asthma, use objective measures such as treatment adherence, spirometry to contrast QoL, and use the perception of other informants such as their parents.

5. CONCLUSION

Coping with a disease such as BA during adolescence can generate a series of interferences in daily life. These interferences can influence how adolescents adapt to this stage, so protective and risk factors will be essential for proper adaptation to the disease. Good self‐esteem and family support are protective factors for the well‐being of adolescents with BA; however, perceiving the disease as more threatening can have negative consequences for their health and negatively impact their QoL.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Selene Valero‐Moreno: data curation (lead); funding acquisition (equal); methodology (lead); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review & editing (equal). Inmaculada Montoya‐Castilla: conceptualization (supporting); project administration (lead); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review & editing (equal). Marián Pérez‐Marín: conceptualization (supporting); project administration (supporting); supervision (lead); writing–original draft (equal); writing–review & editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the adolescents and their families for participating in this study and also the healthcare professionals who provided us with this research.

Valero‐Moreno S, Montoya‐Castilla I, Pérez‐Marín M. Family styles and quality of life in adolescents with bronchial asthma: the important role of self‐esteem and perceived threat of the disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2023;58:178‐186. 10.1002/ppul.26178

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cui W, Zack MM, Zahran HS. Health‐related quality of life and asthma among United States adolescents. J Pediatr. 2015;166(2):358‐364. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saifi M, Bird JA. Health‐related quality of life and asthma among United States adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;136(suppl 3):S266‐S267. 10.1542/peds.2015-2776KKKK [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stridsman C, Backman H, Eklund BM, Rönmark E, Hedman L. Adolescent girls with asthma have worse asthma control and health‐related quality of life than boys—a population based study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(7):866‐872. 10.1002/ppul.23723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berbesí Fernández DY, García Jaramillo MM, Segura Cardona ÁM, Posada Saldarriaga R. Evaluación de la dinámica familiar en familias de niños con diagnóstico de asma. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2013;42(1):63‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crandell JL, Sandelowski M, Leeman J, Havill NL, Knafl K. Parenting behaviors and the well‐being of children with a chronic physical condition. Fam Syst Heal. 2018;36(1):45‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jelenová D, Praško J, Ocisková M, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric aspects of children suffered from chronic physical illness. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2016;58(4):123‐ 131. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah AA, Othman A. A comparative study of psychological problems of children suffering from cancer, epilepsy and asthma. Intellect Discourse. 2017;25(1):153‐ 183. [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Benedictis D, Bush A. Asthma in adolescence: is there any news? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(1):129‐138. 10.1002/ppul.23498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinquart M. Self‐esteem of children and adolescents with chronic illness: a meta‐analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(2):153‐161. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zashikhina A, Hagglof B. Self‐esteem in adolescents with chronic physical illness vs. controls in Northern Russia. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;26(2):275‐281. 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Junghans‐Rutelonis AN, Suorsa KI, Tackett AP, Burkley E, Chaney JM, Mullins LL. Self‐esteem, self‐focused attention, and the mediating role of fear of negative evaluation in college students with and without asthma. J Am Coll Heal. 2015;63(8):554‐562. 10.1080/07448481.2015.1057146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roncada C, de Oliveira SG, Cidade SF, et al. Burden of asthma among inner‐city children from Southern Brazil. J Asthma. 2016;53(5):498‐504. 10.3109/02770903.2015.1108438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinheiro C, Mena P. Padres, profesores y pares: contribuciones para la autoestima y coping en los adolescentes. Revista Anales de Psicologia [revista en Internet] 2014 [Junio 2016]. An Psicol. 2014;30(2):656‐666. 10.6018/analesps.30.2.161521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lima L, Guerra MP, de Lemos MS. The psychological adjustment of children with asthma: study of associated variables. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(1):353‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arcoleo K, Zayas LE, Hawthorne A, Begay R. Illness representations and cultural practices play a role in patient‐centered care in childhood asthma: experiences of Mexican mothers. J Asthma. 2015;52(7):699‐706. 10.3109/02770903.2014.1001905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alkhawaldeh A, ALBashtawy M, Omari OA, et al. Assessment of Northern Jordanian adolescents' knowledge and attitudes towards asthma. Nurs Child Young People. 2017;29(6):27‐31. 10.7748/ncyp.2017.e858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonney J, Insel KC, Segrin C, Gerald LB, Ki Moore IM. Association of asthma illness representations and reported controller medication adherence among school‐aged children and their parents. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2017;31(6):703‐712. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James P, Caballero MR. Illness perception of adolescents with allergic conditions under specialist care. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(2):197‐202. 10.1111/pai.13169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pesut D, Raskovic S, Tomic‐Spiric V, et al. Gender differences revealed by the brief illness perception questionnaire in allergic rhinitis. Clin Respir J. 2014;8(3):364‐368. 10.1111/crj.12082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burg GT, Covar R, Oland AA, Guilbert TW. The tempest: difficult to control asthma in adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):738‐748. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Costello RW, Foster JM, Grigg J, et al. The seven stages of man: the role of developmental stage on medication adherence in respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(5):813‐820. 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al Ghriwati N, Winter MA, Everhart RS. Examining profiles of family functioning in pediatric asthma: longitudinal associations with child adjustment and asthma severity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(4):434‐444. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oliva A, Parra Á, Sánchez‐Quejía I, López‐Gaviño F. Estilos educativos materno y paterno: Evaluación y relación con el ajuste adolescente. An Psicol. 2007;23(1):49‐56. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miadich SA, Everhart RS, Borschuk AP, Winter MA, Fiese BH. Quality of life in children with asthma: a developmental perspective. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(7):672‐679. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boss P, Bryant CM, Mancini JA. Family Stress Management: a Contextual Approach. Sage Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Winter MA, Everhart RS. Examining profiles of family functioning in pediatric asthma: longitudinal associations with child adjustment and asthma severity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(4):434‐444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pinquart M, Gerke DC. Associations of parenting styles with self‐esteem in children and adolescents: a meta‐analysis. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(8):2017‐2035. 10.1007/s10826-019-01417-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carvajal‐Urueña I, García‐Marcos L, Busquets‐Monge R, et al. Variaciones geográficas en la prevalencia de síntomas de asma en los niños y adolescentes Españoles. International Study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) fase III España. Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41(12):659‐666. 10.1016/S1579-2129(06)60333-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vigil L, Güell MR, Morante F, et al. Validez y sensibilidad al cambio de la versión española autoadministrada del cuestionario de la enfermedad respiratoria crónica (CRQ‐SAS). Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47(7):343‐349. 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valero‐moreno S, Castillo‐Corullón S, Prado‐Gascó V‐J, Pérez‐Marín M, Montoya‐Castilla I. Chronic respiratory disease questionnaire (CRQ‐SAS): analysis of psychometric properties. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2019;117(3):149‐155. 10.5546/aap.2019.eng.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631‐637. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tze Siong N. Brief illness perception questionnaire (brief IPQ). J Physiother. 2012;58(3):202. 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70116-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The common‐sense model of self‐regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self‐management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935‐946. 10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Valero‐Moreno S, Lacomba‐Trejo L, Casaña‐Granell S, Prado‐Gascó VJ, Montoya‐Castilla I, Pérez‐Marín M. Psychometric properties of the questionnaire on threat perception of chronic illnesses in pediatric patients. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2020;28:28. 10.1590/1518-8345.3144.3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Atienza FL, Moreno Y, Balaguer I. Análisis de La Dimensionalidad de La Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg En Una Muestra de Adolescentes Valencianos 2000;22:29‐ 42. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosenberg R. Society and the Adolescent Self‐Image. Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: a Regression‐Based Approach. The Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vázquez A, Morejón R, Bellido G. Fiabilidad y validez de la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg (EAR) en pacientes con diagnóstico de psicosis. Apuntes de Psicologia. 2013;31:37‐43. 10.3233/IDA-2011-0490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.