Abstract

Rationale: Chemoimmunotherapy is a promising approach in cancer immunotherapy. However, its therapeutic efficacy is restricted by high reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, an abundance of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor microenvironment (TME) as well as immune checkpoints for escaping immunosurveillance.

Methods: Herein, a new type of TME and reduction dual-responsive polymersomal prodrug (TRPP) nanoplatform was constructed when the D-peptide antagonist (DPPA-1) of programmed death ligand-1 was conjugated onto the surface, and talabostat mesylate (Tab, a fibroblast activation protein inhibitor) was encapsulated in the watery core (DPPA-TRPP/Tab). Doxorubicin (DOX) conjugation in the chain served as an immunogenic cell death (ICD) inducer and hydrophobic part.

Results: DPPA-TRPP/Tab reassembled into a micellar structure in vivo with TME modulation by Tab, ROS consumption by 2, 2'-diselanediylbis(ethan-1-ol), immune checkpoint blockade by DPPA-1 and ICD generation by DOX. This resolved the dilemma between a hydrophilic Tab release in the TME for CAF inhibition and intracellular hydrophobic DOX release for ICD via re-assembly in weakly acidic TME with polymersome-micelle transformation. In vivo results indicated that DPPA-TRPP/Tab could improve tumor accumulation, suppress CAF formation, downregulate regulatory T cells and promote T lymphocyte infiltration. In mice, it gave a 60% complete tumor regression ratio and a long-term immune memory response.

Conclusion: The study offers potential in tumor eradication via exploiting an “all-in-one” smart polymeric nanoplatform.

Keywords: polymersome-micelle transformable nanoplatform, tumor microenvironment modulation, immune checkpoint blockade, immunogenic cell death, cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

Immunogenic cell death (ICD) is characterized by a host immune response via damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (e.g., calreticulin (CRT), high mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1)) and tumor-associated antigen (TAA) secretion from dying tumor cells, together facilitating dendritic cell (DC) recognition, maturation and antigen cross-presentation to T cells 1-4. Due to the efficient immune response activation, ICD induced by chemotherapeutics (e.g., doxorubicin (DOX)), photosensitizers or radiosensitizers have been widely reported in cancer immunotherapies 5-8. However, as has been reported, a high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the tumor microenvironment (TME) is adverse to ICD via injuring HMGB1 function 9; it is essential to consume ROS and reverse the immunosuppressive effects of the TME in order to achieve ICD of tumor cells. Moreover, immunosuppressive TME components including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), regulatory T cells (Tregs) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are also adverse to therapeutic efficacy 10-16. CAFs account for a large proportion of the TME's contribution to Treg up-regulation and TGF-β secretion 17, 18. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is a typical marker of CAFs, and plays a key role in fibrosis, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and tumor progression 19-21. FAP may be a potential targeting point for CAFs inhibition with the aim of reversing TME mediated immunosuppression. Recently, FAP inhibitors, e.g., talabostat mesylate (Tab), have been exploited for CAF inhibition with successful immunosuppressive cytokine downregulation 19.

Immune checkpoint signaling pathways, e.g., programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), play a key role in facilitating tumors' escape from host immunosurveillance 22. Nowadays, a variety of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) including pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as malignant tumor treatments 23-25. Other strategies including gene delivery to silence PD-L1 also have been reported 26. Nevertheless, the high costs of antibody or gene therapy should not be ignored. Recently, other PD-L1 inhibitors, such as D-peptide antagonist (DPPA-1), have been easily synthesized to an acceptable price and reported in immune checkpoint blockade studies to show potentially robust therapeutic efficacy 27-29. Therefore, exploiting synthetic antagonists of immune checkpoint proteins may be a promising strategy in exerting host immune responses to a reduced cost.

Stimulus-responsive nanomedicine is indispensable in cancer immunotherapy due to their long circulation time, high tumor accumulation and especially due to their controllable release 30-37. Stimulus (e.g., redox, pH, reactive oxygen species) responsive nanosystems mainly facilitate immune responses via chemotherapeutics, photosensitizers, immune checkpoint blockade, antigens, siRNA or agonist triggered release 38-43. Furthermore, stimulus-responsive prodrug nanoplatforms, which are able to endow carrier bioactivity, reduce drug leakage and trigger drug release at the specific site, are attracting more and more attention 44, 45. Transformable stimulus-responsive nanomedicine with tunable size or morphology is in the TME capable of prolonging tumor retention and/or facilitating internalization, which reinforces its therapeutic efficacy 46-49. Therefore, transformable stimulus-responsive prodrug nanocarriers may have a huge potential in provoking host immune responses when combined with ICI and TME modulation.

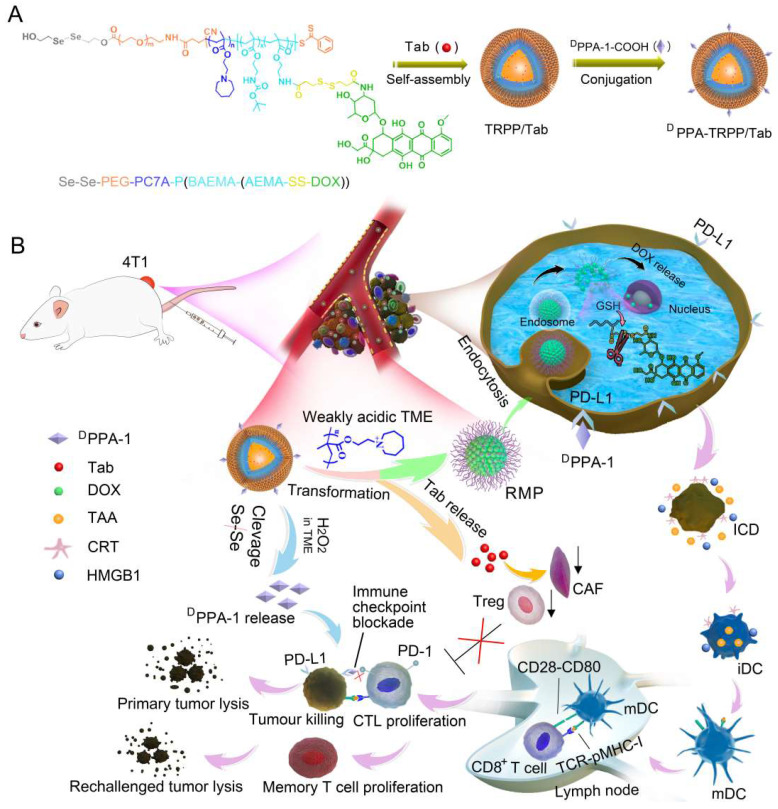

Herein, we constructed a TME-and-reduction dual-responsive polymersomal prodrug (TRPP) nanoplatform based on copolymer 2, 2'-diselanediylbis(ethan-1-ol)-polyethylene glycol-poly 2-(hexamethyleneimino)ethyl methacrylate-poly ((2-boc-amino)ethyl methacrylate-(2-amino ethyl methacrylate-disulfide-DOX) (HO-Se-Se(dSe)-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) with FAP inhibitor Tab encapsulation (TRPP/Tab) (Scheme 1). DPPA-1 was able to conjugate to the TRPP/Tab surface via an esterification reaction to form DPPA-TRPP/Tab. When encountering the high concentration of H2O2 in the TME, the Se-Se bond was cleaved with H2O2 consumption and DPPA-1 shedding for PD-L1 blockade. The PC7A segment was converted from being hydrophobic to hydrophilic in the weakly acidic TME with re-assembly and transformation into a reduction-sensitive micellar prodrug (RMP). During re-assembly, Tab was released from TRPP into the TME for CAF inhibition. When RMP was further internalized by tumor cells, DOX was released due to the disulfide bond cleavage in the high intracellular glutathione concentration, with accompanying tumor ICD. Concurrently, DPPA-TRPP/Tab inhibited Tregs, down-regulated α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression and TGF-β secretion, induced ICD, and facilitated TNF-α secretion and T lymphocyte infiltration. Remarkably, when the initial tumor volume was around 100 mm3, DPPA-TRPP/Tab in a single dose achieved 60% complete regression in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. The rechallenge-tumors remained notably suppressed compared with those in untreated mice due to the long-term memory immune response. For the relatively large initial tumor (~150 mm3), DPPA-TRPP/Tab also displayed a higher antitumor activity than the other groups did. This design may provide an approach to combine multiple immunosuppressive-factors-reversal with ICD in potentiating cancer immunotherapy efficacy.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of TME and reduction dual-responsive prodrug DPPA-TRPP/Tab nanoplatform for cancer immunotherapy. (A) Preparation of DPPA-TRPP/Tab. (B) DPPA-TRPP/Tab elicits immune response via immune checkpoint blockade, TME modulation and immunogenic cell death.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of pH-responsive tri-block copolymer COOH-PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA

The macromolecular RAFT reagent COOH-PEG-CPAA was obtained via amidation between COOH-PEG-NH2 and CPPA according to a previous report 50. The 1H NMR spectrum and MALDI-TOF results are presented in Figure S2-S3. (Supporting Information). HOOC-PEG-CPPA (100 mg, 0.02 mmol), MA-C7A (60 mg, 0.28 mmol) and AIBN (0.49 mg, 0.003 mmol) were dissolved in 1, 4-dioxane (2 mL) under inert atmosphere. After being stirred at 65 ºC for 24 h, the product went through precipitation, filtration and vacuum desiccation to obtain the di-block copolymer PEG-PC7A. The related characterization including 1H NMR and GPC results are shown in Figure S4 and Table S1 (Supporting Information). To obtain the tri-block copolymer PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA, PEG-PC7A (140 mg, 0.019 mmol), BAEMA (112 mg, 0.49 mmol) and AIBN (0.49 mg, 0.003 mmol) were dissolved in 1,4-dioxane under nitrogen protection. After being stirred at 65 ºC for 48 h, the mixture was then precipitated into a cold diethyl ether, followed by filtration. The final product (HOOC-PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA) was obtained, 1H NMR spectrum and GPC results of which are shown in Figure S5-S6 and Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Synthesis and characterization of HOOC-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA)

HOOC-PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA (200 mg, 0.017 mmol) and TFA (2 mL) were dissolved in DCM (2 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature (RT) for 0.5 h and then dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO = 3500 Da) and lyophilized. The final product (HOOC-PEG-P(BEM-BAEMA)-PC7A) was obtained as a light-yellow powder (150 mg, yield 75%). The 1H NMR spectrum is shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Information).

Synthesis and characterization of dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA)

HOOC-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA) (100 mg, 8.6 μmol) dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF, 2 mL) was activated with EDC•HCl (2.5 mg, 13.1 μmol) and DMAP (1.6 mg, 13.1 μmol) under nitrogen atmosphere at RT for 1 h. dSe (1 mg, 12.6 μmol) was then added to the above mixture under nitrogen atmosphere. After 24 h reaction at RT, the mixture was dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO = 3.5 kDa) and lyophilized. The final product (dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BEM-BAEMA)) was obtained as a light-yellow powder (75 mg, yield 74%) (Figure S6, Supporting Information).

Synthesis and characterization of dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-DTPA))

3, 3-Dithiodipropionic acid (DTPA) (3.1 mg, 14.7 μmol) dissolved in DMF (2 mL) was activated with EDC•HCl (4.2 mg, 21.9 μmol) and NHS (2.5 mg, 21.9 μmol) under nitrogen atmosphere at RT for 1 h. dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA) (55 mg, 4.7 μmol) was dropwise added to the above mixture under nitrogen atmosphere. After being left to react for 24 h at RT, the mixture was dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO = 3.5 kDa) and lyophilized. The final product (dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-DTPA) was obtained as a light-yellow powder (50 mg) (Figure S7, Supporting Information).

Synthesis and characterization of dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)

dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-DTPA)) (40 mg, 3.33 μmol) dissolved in DMF (2 mL) was activated with EDC•HCl (2.9 mg, 15 μmol) and NHS (1.7 mg, 15 μmol) under nitrogen atmosphere at RT for 1 h. DOX (5.8 mg, 10 μmol) was then added to the above mixture under nitrogen atmosphere. After being left to react for 24h at RT, the mixture was dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO = 3.5 kDa) and lyophilized. dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) was obtained as a red powder, the DOX content in which was characterized by UV-vis (Figure S8, Supporting Information).

DOX conjugation ratio detection

Free DOX, with a series of different concentrations from low to high, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40 μg/mL, was measured by UV-vis for the standard curve. Pro-drug copolymer dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) dissolved in DMF (1 mg/mL) was detected by UV-vis to obtain the absorbance curve. The DOX content in each polymer chain was calculated according to the absorption intensity and standard curve.

H2O2 consumption investigation

Prodrug copolymer dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) was dissolved in DMF to prepare different concentration solutions (1 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL) with H2O2 (100 μM) addition. A H2O2 fluorescence probe (Oxi Vision greenTM) was added to the above solutions, and to a H2O2 standard solution, then all were incubated for 1 h at RT. The H2O2 concentration changes in each sample were detected via fluorescence spectroscopy.

Preparation of TME, pH and reduction triple-responsive polymersomal prodrug nanoplatform (TRPP)

The TRPP was fabricated by a solvent-exchange method. Prodrug copolymer dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) dissolved in THF (200 μL, 5 mg/mL) was dropwise added into phosphate buffered solution (PBS, 800 μL, 10 mM, pH 7.4) to acquire the uniform nanoplatform. A TME responsive polymersome (TP), as a control, was prepared by a similar method, it self-assembled from copolymer PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA. The dynamic sizes and morphology were separately measured by dynamic latter scattering (DLS) and by transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Preparation of DPPA-1 decorated TRPP (DPPA-TRPP)

DPPA-1 was able to conjugate on the TRPP surface to form DPPA-TRPP. In detail, DPPA-1 (55 μg, 0.026 μmol) first reacted with EDC.HCl (13.6 μg, 0.071 μmol), DMAP (8.6 μg, 0.071 μmol) and triethylamine (TEA, 10 μL, 0.071 μmol) for 30 min at 30 ºC. The reactants were then added dropwise into TRPP (1 mg/mL, 1 mL) and stirred overnight. After dialysis (MWCO, 3500), DPPA-TRPP was obtained, the size and size distribution of which were measured by DLS. The morphology was characterized by TEM.

DPPA-TRPP transformation into micellular nanoplatform investigation

DPPA-TRPP transformation was explored by size and morphology changes, respectively. DPPA-TRPP at pH 6.8 or 7.4 was monitored by DLS at pre-set time points to show the pH responsiveness and re-assembly. Morphologies were captured by high angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) at 0 and 24 h (pH 6.8) for further transformation confirmation. One drop of DPPA-TRPP was put on carbon-coated copper grids and air-dried overnight at RT before capturing images.

Animals and cells

BALB/c mice (female, 6-8 weeks, 20 g) were purchased from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All the animal experiments were executed with ethical compliance and following the protocol from the Institute of Drug Discovery & Development of Zhengzhou University (syxk (yu) 2018-0004). 4T1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle media (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin & streptomycin (P&S) (37 ºC, 5% CO2).

In vivo antitumor activity investigation

BALB/c mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells (2.0 × 106 per mouse) in the right flank. Five formulations, PBS, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP/Tab, DPPA-TRPP/Tab (DPPA: 0.5 mg/kg, DOX: 0.5 mg/kg, Tab: 1.0 mg/kg), were used to treat the tumor-bearing mice. As for the small initial tumor volume treatment, drug formulations were given at day-6 post-inoculation when tumor volumes were around 100 mm3. Tumor volume and body weight in each group were measured every three days. The formula used to calculate tumor volume was V = 0.5 * Length * Width2. Tumor volume recordings were stopped when the volumes reached 1500 mm3 at day-27. The survival of mice was observed and recorded within 45 days. The surviving mice were rechallenged with 4T1 cells for the memory immune response study when the untreated mice were also inoculated. The rechallenge-tumor volume was monitored and measured every three days with untreated mice as a control. Mice were euthanatized when the tumor volume in the untreated mice was around 1500 mm3 at day 72. Tumors from each group were photographed and weighed.

As for the mice with larger initial tumor volume (~150 mm3), different formulations were intravenously administered at day 9 post-inoculation. Tumor volume and body weight were measured until the tumor volume reached 1500 mm3. Mice were euthanatized at the therapeutic endpoint, at which tumor and major organs, e.g., heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidneys, were extracted for H&E staining. Apoptosis of tumor tissues was also evaluated by terminal-deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay.

Cytokine detection

HMGB1 from the supernatant in 4T1 cells treated by TRPP was measured via ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol. IL-12, TNF-α and TGF-β levels in serum were also detected via ELISA according to standard protocols.

Flow cytometry measurement for T cell populations

Tumors, after extraction from treated mice, were cut into small pieces, mechanically grinded and then digested by collagenase (50 U/mL), hyaluronidase (100 μg/mL) and DNAse (50 U/mL) for 2 h at 37 ºC. Cells then underwent filtration, centrifugation and washing by PBS. Cells were stained with anti-CD3e-PE, anti-CD8a-APC, and anti-CD4-Percp/Cy5.5 for CD8+CD4+ T cells, anti-CD4-Percp/Cy5.5 and anti-Foxp3-FITC for Tregs for 30 min at RT. After further washing and centrifugation, cells were suspended in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence staining assay

Extracted tumors from mice were embedded with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound, frozen at -80 ºC for 48 h. Tumor sections were obtained using cryotomy, and stained with different primary antibodies. Anti-CD31 and anti-α-SMA were used for CAF characterization. Anti-CD3, anti-CD8 and anti-CD4 were used for CD8+ and CD4+ T cell infiltration investigation. Anti-CRT was exploited for ICD studies. The above primary antibodies were stained overnight at 4 ºC, followed by fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies (Goat anti-Rat Alexa Fluor® 488, Donkey anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor® 594 staining. The slides were captured by confocal microscopy (CLSM).

Statistical analysis

Data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. The numbers of samples per group (n) are specified in the figure legends. Comparison of parameters for more than three groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's significant difference post-hoc test. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, or NS > 0.05).

Results and Discussion

Preparation and Characterization of TRPP

To construct the TME and reduction dual responsive nanoplatform, we first synthesized a pH responsive monomer MA-C7A via a substitution reaction (Scheme S1) and the macro reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) agent PEG-CPPA was obtained via amidation reaction (Scheme S2). Figure S1 showed that the pure monomer MA-C7A was obtained. As shown in Figure S2, the conversion ratio of CPPA was as high as 94.6%, read from its 1H NMR spectrum. The MALDI-TOF spectra in Figure S3 also indicated the successful synthesis of PEG-CPPA. The pH sensitive di-block PEG-PC7A and tri-block copolymer COOH-PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA were synthesized via a reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization (Scheme S3). As shown in Figure S4 and Figure S5, the molecular weights of PEG-PC7A and COOH-PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA were 5.0-2.3 and 5.0-2.3-4.7 kg/mol, respectively, according to the 1H NMR spectra. The relative molecular weights of the two block copolymers were 9.3 (di-block, Mw/Mn: 1.22) and 11.8 kg/mol (tri-block, Mw/Mn: 1.24), respectively, from gel permeation chromatography (GPC) results, in agreement with the 1H NMR spectra (Figure S6, Table S1). After hydrolysis, COOH-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA(NH2)) was obtained (Scheme S4); the hydrolysis degree was 13.6% according to the 1H NMR result in Figure S7. The primary amine (NH2) content was 2.7 NH2 in each polymer chain detected by a 2, 4, 6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBSA) assay (Figure S8), which was consistent with the 1H NMR result (Figure S7).

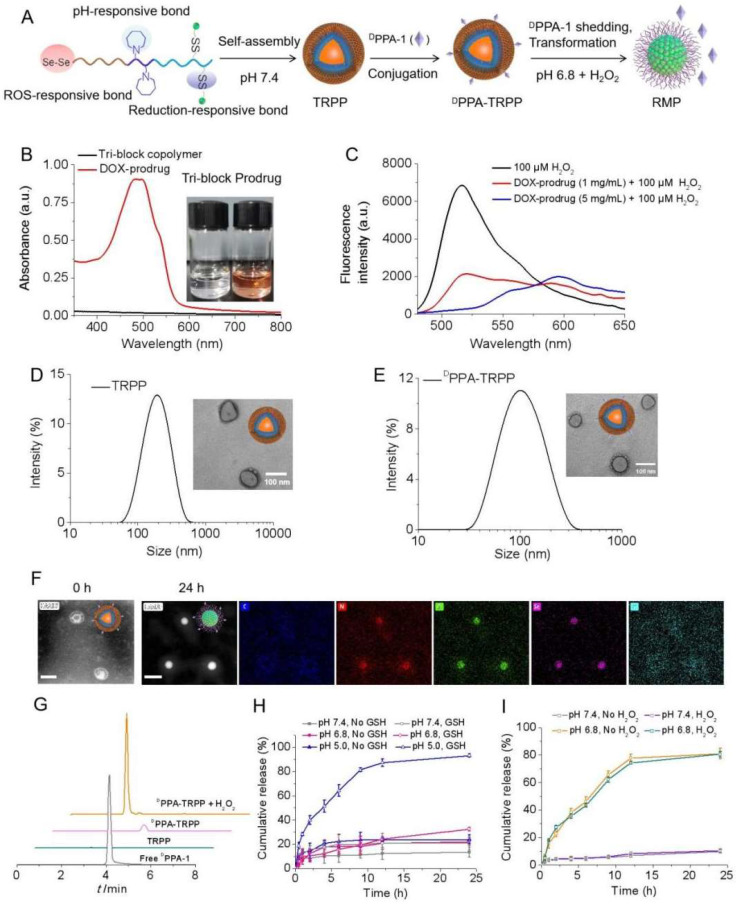

2, 2'-Diselanediylbis(ethan-1-ol) (HO-Se-Se-OH, written as dSe) was obtained after a substitution reaction (Scheme S5), with satisfactory purity as read from the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra in Figure S9. According to Figure S10 (Supporting Information) for the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) characterization, Se-Se bond cleavage was notably observed with seleninic acid formation in the presence of H2O2 (100 µM) based on the characteristic absorption band at 880 cm-1 indicating the ROS consumption of dSe. H2O2 and pH dual responsive HO-Se-Se(dSe)-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA) was acquired after an esterification reaction (Scheme S6), which was characterized by 1H NMR and infrared spectra as shown in Figure S11. DTPA was able to react with dSe-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-AEMA) via an amidation reaction (Scheme S7), Figure S12 shows the successful conjugation. After amidation with DOX, the TME and reduction dual responsive prodrug (dSe)-PEG-PC7A-P(BAEMA-(AEMA-SS-DOX)) was obtained (Scheme S8, Figure 1A). The schematic illustration for preparation and pH responsiveness of TRPP is shown in Figure 1A. According to Figure 1B and Figure S13, DOX mass fraction in the prodrug copolymer was 5% as detected by UV-vis, with the average number of DOX being 1.2 in each prodrug copolymer chain. The orange color of the prodrug copolymer also demonstrated successful DOX conjugation. H2O2 responsiveness of the prodrug copolymer was subsequently investigated using a TME mimicking ROS concentration. As shown in Figure 1C, the H2O2 (100 µM) amount significantly decreased with an attenuated peak absorption at 520 nm after prodrug treatment. With increasing prodrug concentration, the H2O2 consumption increased (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

In vitro construction and characterization of TME and reduction dual responsive polymersomal prodrug (TRPP) nanoplatform and DPPA-1 decorated TRPP (DPPA-TRPP). (A) Schematic illustration of preparation, pH and ROS responsiveness of DPPA-TRPP. (B) UV-vis spectrum of prodrug copolymer. Inset image presented tri-block or prodrug copolymer. (C) In vitro H2O2 (100 µM) consumption mediated by prodrug copolymer. (D) Size and morphology of TRPP measured by DLS and TEM, respectively. (E) DPPA-TRPP characterization by DLS and TEM. (F) Morphology transformation of DPPA-TRPP from polymersomes into micelles at pH 6.8 characterized by HAADF-STEM. Result at 0h represented the HAADF-STEM image of DPPA-TRPP. Result at 24h represented the STEM-EDC mapping images of DPPA-RMP. (G) DPPA-1 shedding from DPPA-TRPP in the condition of H2O2 (100 µM) detected by HPLC. (H) In vitro DOX release from DPPA-TRPP under different conditions within 24 h measured by fluorescence spectrophotometer. (n = 3, mean ± SD). (I) In vitro Tab release from DPPA-TRPP under different conditions within 24 h detected by LC-MS (n = 3, mean ± SD).

The prodrug copolymer could self-assemble into a TRPP nanoplatform via a solvent-exchange method. According to the DLS result, TRPP had a hydrodynamic size of 174 ± 4 nm with a narrow distribution (0.13 ± 0.02) (Figure 1D). The morphology was characterized by TEM, which confirmed its hollow structure (Figure 1D). The TP was fabricated by PEG-PC7A-PBAEMA as a control, the size of which measured by DLS was 140 ± 2 nm with narrow distribution (0.11 ± 0.01) (Figure S14). DPPA-1 was able to conjugate onto the TRPP surface via an esterification reaction to form DPPA-TRPP (Figure 1A). The DLS result indicated that DPPA-TRPP had a hydrodynamic size of 134 ± 5 nm with a relatively narrow distribution (0.19 ± 0.05), the hollow morphology of which was confirmed by TEM (Figure 1E). As shown in Figure S15, DPPA-TRPP increased at 8 h under weakly acidic condition (pH 6.8), while it re-assembled into smaller ones at 24 h, indicating its pH responsiveness. In contrast, a negligible size change was observed when DPPA-TRPP was placed in the neutral PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mM, 150 mM NaCl), showing its stability under physiological conditions. As shown in Figure 1F, a clear hollow structure of DPPA-TRPP was observed from the HAADF-STEM image. The noticeable micellar transformation of DPPA-TRPP was seen at pH 6.8 at 24 h when densities of elements C, N, O Se and S were observed on the particle surface from STEM-EDC mapping results (Figure 1F). We speculated that the morphological transformation may be attributed to the PC7A segment changing from hydrophobic to hydrophilic at a low pH value. As shown in Figure S15B-D, DPPA-TRPP had a superior stability in PBS, blood and cell culture medium, with negligible size changes.

DPPA-1 was able to cleave from TRPP in the presence of H2O2 (100 µM) (Figure 1G), measured by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). As shown in Figure 1H, DOX was rapidly released from DPPA-TRPP with a cumulative release as high as 93.1% in a pH 5.0 10 mM GSH solution within 24 h. Without GSH, or with 10 mM GSH at pH 7.4, DOX release was in the range of 21.0-22.1%. At pH 6.8, with 10 mM GSH, the cumulative release was slightly higher (32.5%) than in the other control groups. The above results indicated that both low pH and high reduction conditions are essential for facilitating DOX release. Tab could be encapsulated in both TRPP and DPPA-TRPP to form TRPP/Tab and DPPA-TRPP/Tab, respectively. As shown in Table S2, both TRPP and DPPA-TRPP were able to efficiently encapsulate Tab when the drug loading efficiency (DLE) was high as 81.3-84.8% in a theoretical drug loading content (DLC) as 5%. The highest DLC reached 8.57% when the size changed from 118 ± 3 to 132 ± 4 nm, with a relatively narrow PDI (Table S2). Tab was rapidly released from DPPA-TRPP at pH 6.8, with or without H2O2, the cumulative release was as high as 80.9% within 24 h (Figure 1I). In contrast, at pH 7.4, the release was around 10%.

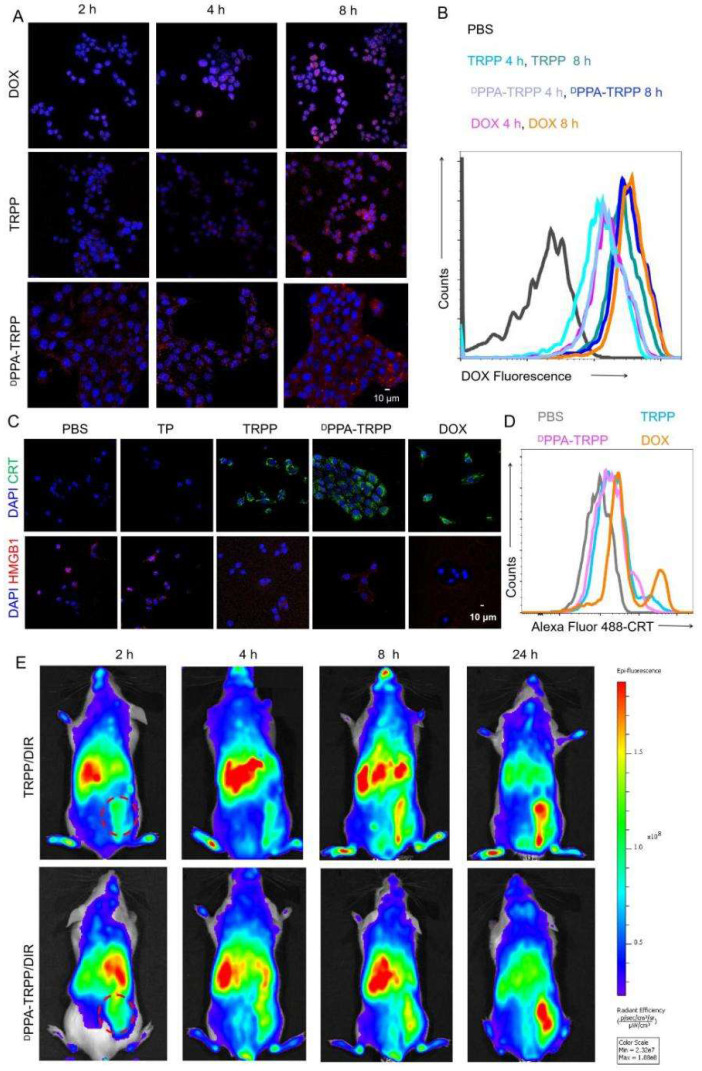

In vitro cellular behavior and in vivo NIR imaging

The cellular behavior of DPPA-TRPP was subsequently investigated. TRPP induced potent cytotoxicity in 4T1 cells due to DOX conjugation with an IC50 of 1.39 µg/mL, which is similar to that of free DOX (1.25 µg/mL) (Figure S16, Supporting Information). As shown in Figure 2A and B, DPPA-TRPP could be rapidly internalized by 4T1 cells with the red signal (DOX) observed with CLSM (Figure S17) and in the form of a noticeable fluorescence shift during flow cytometry. DPPA-TRPP induced ICD in 4T1 cells when CRT exposure and HMGB1 release were observed from CLSM (Figure 2C, Figure S18) and ELISA (Figure S19). Less HMGB1 release was observed in TP treated cells, indicating that DOX conjugation triggered ICD. Flow cytometry results in Figure 2D with a notable CRT fluorescence shift further confirmed DPPA-TRPP mediated ICD. In addition, whether the nanocarrier TP itself without DOX conjugation induces immunity is an interesting point. As seen in Figure S20, TP could induce DC maturation with a 19.0 ± 1.6% CD80+CD86+ ratio in CD11c+ DC 2.4 cells, which was 1.7-fold higher than that of PBS (11.5 ± 0.9%). In addition, TRPP and DPPA-TRPP mediated ICD with DAMPs release also facilitated DC maturation with 26.5 ± 1.3% and 27.5 ± 1.3% CD80+CD86+ DCs detected, which was approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of PBS (10.7 ± 1.2%, Figure S21).

Figure 2.

Cellular behavior and in vivo tumor accumulation investigation. (A) Cellular internalization of DPPA-TRPP in 4T1 cells characterized by CLSM and (B) flow cytometry, respectively. (C) DPPA-TRPP mediated ICD via CRT exposure and HMGB1 release via CLSM characterization. Blue color presented DAPI. Green and red colors were CRT and HMGB1, respectively. (D) TRPP induced ICD by flow cytometry characterization. (E) In vivo tumor accumulation of DPPA-TRPP/DIR and TRPP/DIR at different time points.

We then investigated in vivo tumor accumulation of DPPA-TRPP, which was the precondition for successful TME modulation and antitumor activity enhancement. To conveniently monitor tumor accumulation at different time points, Tab was replaced by lipophilic DIR as the fluorescent model compound encapsulation in DPPA-TRPP to form DPPA-TRPP/DIR. As shown in Figure 2E, the fluorescent signal from tumor tissue increased over time in mice with TRPP/DIR or DPPA-TRPP/DIR treatment within 24 h, indicating the prolonged retention time of this nanoformulation.

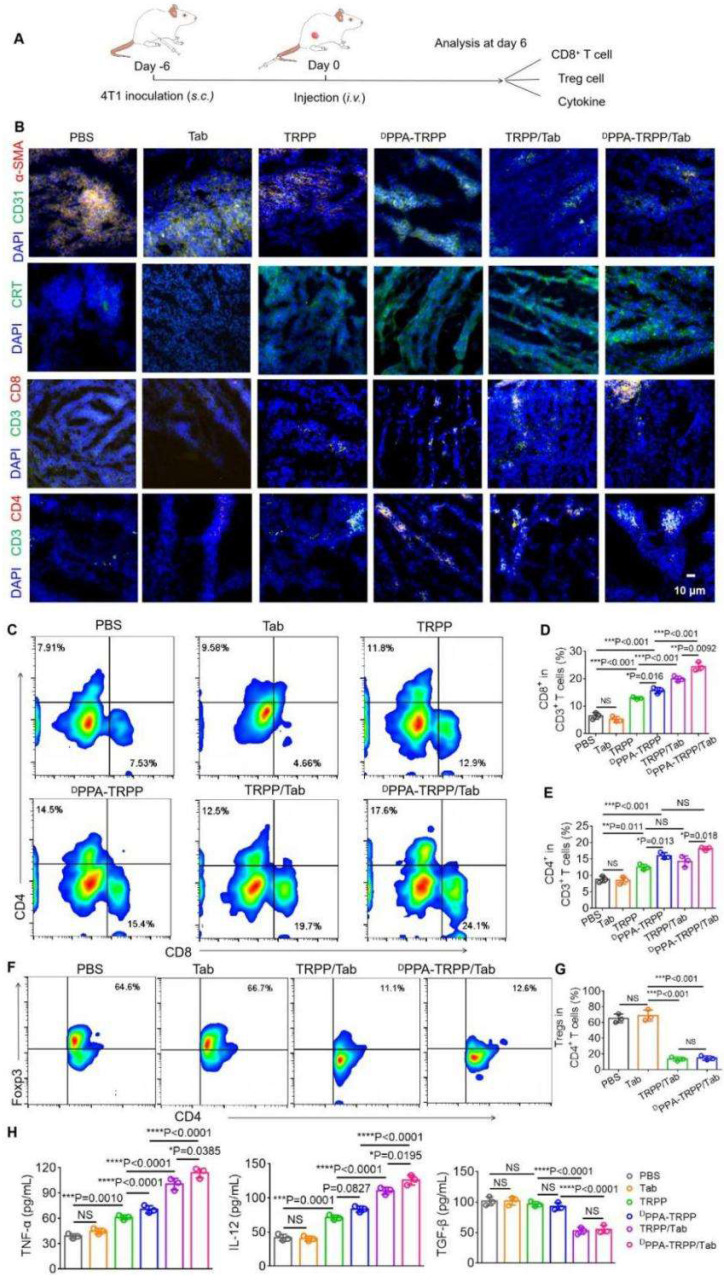

In vivo TME modulation investigation

The nanosystem mediated TME modulation was subsequently explored (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, weak α-SMA signals (red color) were observed in tumor tissue for mice with DPPA-TRPP/Tab and TRPP/Tab treatments, illustrating CAF inhibition (Figure S22a). Notable α-SMA fluorescence existed in mice treated by PBS, free Tab, TRPP, and DPPA-TRPP, showing that Tab encapsulation in this nanosystem induced TME modulation (Figure 3B, Figure S22a). Notable CRT exposure (green color) was observed in all nanoformulated treatment groups, but not in single Tab treated mice, indicating DOX conjugation mediated ICD (Figure 3B, Figure S22b). CRT expression was not affected by DPPA-1 attachment and Tab encapsulation in TRPP nanoformulations, indicating that the DOX conjugation induced ICD. Impressively, DPPA-TRPP/Tab treated mice had the most CD8+ and CD4+ T cell infiltration compared with the other groups, mainly attributed to the combination of DPPA-1 mediated immune checkpoint blockade, Tab-induced TME modulation, and DOX-caused ICD (Figure 3B, Figure S23). Flow results shown in Figure 3C-G were similar to those in Figure 3B with CD8+, CD4+ T cell percentage increments and CD4+ Foxp3+ T cell percentage decrements for nanoformulation treated groups. In short, mice given DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatments had the highest CD8+CD4+ percentage (42.7 ± 1.5%) compared with the other groups (PBS: 15.3 ± 1.0%, Tab: 13.7 ± 0.5%, TRPP: 25.5 ± 1.0%, DPPA-TRPP: 31.7 ± 1.6%, TRPP/Tab: 34.2 ± 1.5%) (Figure 3D, E). The Foxp3+CD4+ ratio was significantly decreased in mice given the Tab nanoformulation treatment (14.3 ± 2.2%) compared with mice given PBS (65.4 ± 4.6%) or Tab (68.9 ± 5.8%) (Figure 3G). Mice treated with Tab nanoformulations had the highest TNF-α and IL-12 levels compared with the other groups (Figure 3H). TGF-β was as expected suppressed in Tab nanoformulation treated mice compared with those receiving PBS, single Tab, TRPP or DPPA-TRPP treatments (Figure 3H). The results suggest that TME modulation mediated by Tab, ICD induced by DOX and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade by DPPA-1 together facilitated CD8+ CD4+ T cell infiltration for a potent immune response.

Figure 3.

In vivo tumor microenvironment modulation after DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment at day 6 after 4T1 tumor inoculation into BALB/c mice. The mice were divided into PBS, Tab, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP/Tab, and DPPA-TRPP/Tab groups (n = 3/group). (A) Schematic illustration for the tumor inoculation, drug administration and analysis. (B) α-SMA staining for CAFs characterization, CRT staining for ICD, CD8+ and CD4+ T cell infiltration in tumor tissue after different treatments. (C) Representative CD8+ CD4+ T cell percentages and (D, E) quantitative analysis in tumor tissue after different treatments by flow cytometry measurement. (F) Representative Foxp3+ CD4+ percentage and (G) quantitative analysis. (H) Cytokines TNF-α, IL-12 and TGF-β in serum were detected via ELISA after treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by analysis of ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test.

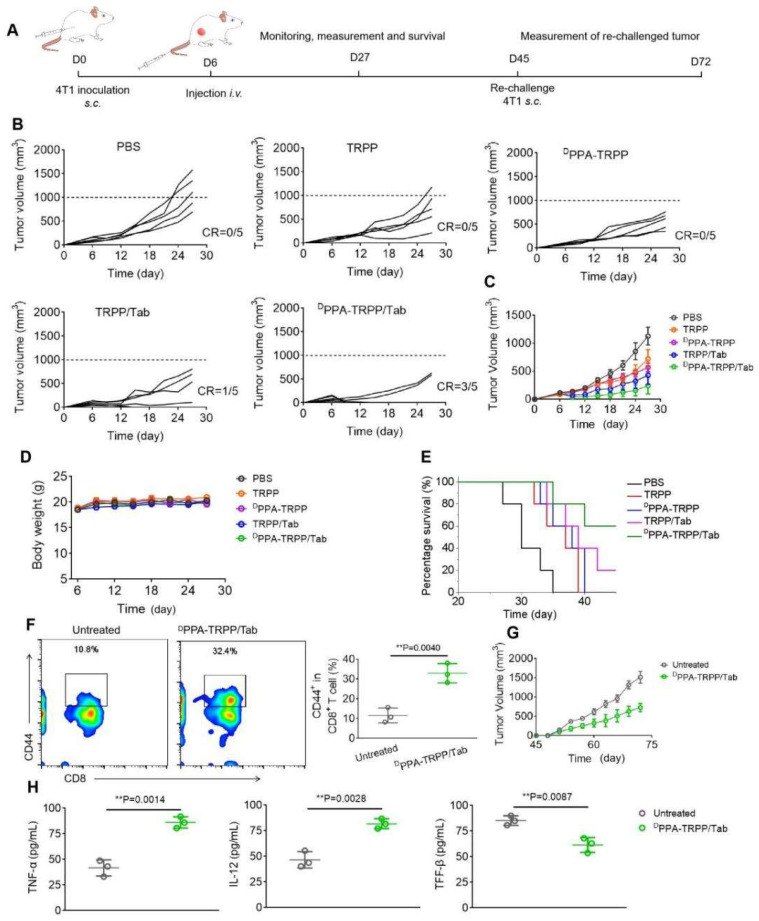

In vivo antitumor immunity and long-term memory immune response

Since the ultimate purpose of devising the project was tumor growth inhibition, the in vivo antitumor activity of DPPA-TRPP/Tab was then investigated in 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. The mice were randomly divided into five groups of PBS, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP/Tab and DPPA-TRPP/Tab, at day 6 after tumor inoculation when their tumor volumes were approximately 100 mm3. The schematic illustration for tumor inoculation, drug administration, observation, tumor re-challenging and analysis is shown in Figure 4A. As shown in Figure 4B and C, the tumor volume and growth were significantly suppressed in mice undergoing DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment, with a complete tumor regression (CR) ratio as high as 60%. The CR ratio in TRPP/Tab treated mice was 20% (Figure 4B and C). The DPPA-TRPP treated group showed slightly higher antitumor activity than did the TRPP-only treated group, both treatments were superior to PBS. The tumor images of treated mice at day 27 after inoculation were shown in Figure S24, these also confirmed the highest antitumor effect of DPPA-TRPP/Tab. Negligible body weight changes were observed in mice after treatment, indicating that the treatments were well tolerated (Figure 4D). DPPA-TRPP/Tab treated mice had prolonged survival time compared with mice in the other groups (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

In vivo antitumor activity and long-term memory immune response of DPPA-TRPP/Tab in 4T1 tumor model. (A) Schematic illustration for the tumor inoculation, drug administration, tumor volume monitoring and analysis. The drug was administered at day 6 post inoculation. Mice were randomly divided into five groups: PBS, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP/Tab, and DPPA-TRPP/Tab (n = 5/group). (B) Individual and (C) average tumor volume growth curve after different treatments. CR represented complete tumor regression. (D) Body weight changes. (E) Survival curves. (F) CD44+ CD8+ T cell percentage and quantitative analysis. (G) Rechallenge-tumor volume growth curve. (H) Cytokine detection in serum of mice at day 7 post rechallenging. **P < 0.01 by analysis of ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test.

Mice with complete tumor regression were rechallenged at day 45 post first tumor inoculation, with the untreated mice serving as controls. Before the re-challenging, memory T cells were analyzed from plasma. As shown in Figure 4F, mice subjected to the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment had a higher percentage of CD8+CD44+ T cells (32.9 ± 4.0%) than untreated mice (11.6 ± 3.1%). As shown in Figure 4G, the rechallenge-tumors were notably suppressed in mice undergoing the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment compared with the tumors in untreated mice. Tumor images and weight at day 72 post inoculation further confirmed the high antitumor activity of DPPA-TRPP/Tab (Figure S25). Negligible body weight loss was observed in mice with rechallenge-tumors (Figure S26). As shown in Figure 4H, higher TNF-α and IL-12 levels, and lower TGF-β concentrations were detected in mice undergoing DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment than in untreated mice. The above results indicated a superior antitumor activity of DPPA-TRPP/Tab even in a single dose, with indicated high CR ratio, long survival time and robust tumor growth inhibition even for tumor re-challenged mice.

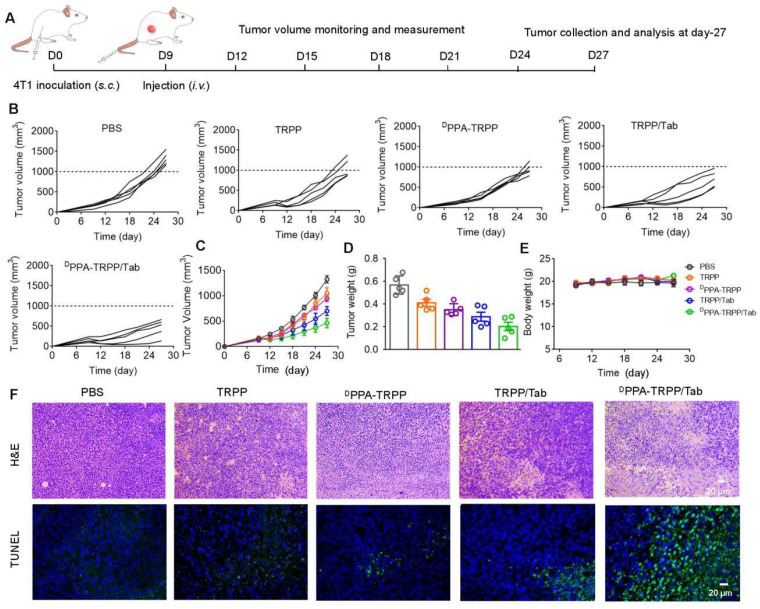

In vivo antitumor and further mechanism investigation for larger initial tumor

Inspired by the robust antitumor activity of DPPA-TRPP/Tab for mice with relatively small initial tumor volume (~100 mm3), we then investigated the antitumor efficacy against a larger initial tumor (~150 mm3). The detailed schematic illustration is shown in Figure 5A. According to Figure 5B and C, even though no complete tumor regression was observed, mice undergoing the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment had the best antitumor activity compared with PBS, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP and TRPP/Tab treated mice. Mice treated with DPPA-TRPP/Tab had the lowest tumor volume compared with the mice in other groups (Figure 5D), which was confirmed by tumor photographs in Figure S27. No obvious body weight changes (Figure 5E) and negligible normal organ damages (Figure S28) were observed in all groups showing again that the treatments were well tolerated. The noticeable cell death was observed in mice undergoing the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and TUNEL results indicating its potent tumor lethality (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

In vivo antitumor activity of DPPA-TRPP/Tab in 4T1 tumor model. (A) Schematic illustration for the tumor inoculation, drug administration, tumor volume monitoring and analysis. Drug formulations were administered at day 9 post-inoculation. Mice were randomly divided into five groups: PBS, TRPP, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP/Tab, and DPPA-TRPP/Tab (n = 5/group). (B) Individual and (C) average tumor volume growth curves after treatment. (D) Tumor weight at the therapeutic endpoint. (E) Body weight changes. (F) H&E staining and TUNEL results of tumor tissues.

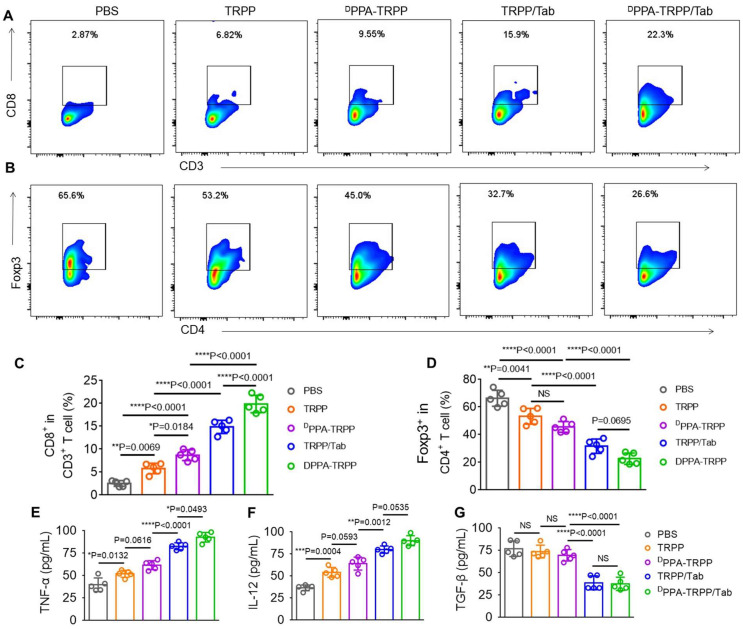

To further study the antitumor activity, we investigated CAFs and T cell distribution, analyzed the T cell population in tumor tissue and detected cytokines at the therapeutic endpoint. As shown in Figure S29, significant CD8+ (red color) T cell infiltration was observed in tumor tissue of mice after DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment, while the α-SMA expression decreased, indicating effective inhibition of CAFs. Flow cytometry analyses were consistent with the above results that CD8+CD3+ T cell percentages notably increased (Figure 6A) and Foxp3+CD4+ T cell percentages significantly decreased (Figure 6B) in mice given the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment. CD8+ T cell percentages in tumor tissue of mice treated with DPPA-TRPP/Tab were 1.4-, 2.3-, 3.4- and 7.8-fold higher than those of TRPP/Tab, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP and PBS treated mice, respectively (Figure 6C). Percentages of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells for mice treated with DPPA-TRPP/Tab were 0.72-, 0.50-, 0.43- and 0.34-fold lower than those of TRPP/Tab, DPPA-TRPP, TRPP and PBS treated mice, respectively (Figure 6D), demonstrating that Tab played a key role in facilitating Tregs' decrease. The highest TNF-α and IL-12 levels were detected in mice undergoing the DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment compared with mice in the other groups (Figure 6E, F). TGF-β levels were notably suppressed in mice treated with DPPA-TRPP/Tab and TRPP/Tab, 0.51 to 0.56-fold lower than in mice treated with DPPA-TRPP or TRPP alone, and 0.49 to 0.50-fold lower than in mice given PBS (Figure 6G). The results above indicate that multiple factors are contributing to the improved antitumor activity, including Tregs suppression, TGF-β down regulation, TNF-α and IL-12 increase, and CD8+ T cell infiltration.

Figure 6.

Cell population analysis and cytokine detection at the therapeutic ending point. (A) Representative CD8+ CD3+ T cell percentages and (B) CD4+ Foxp3+ percentages in tumor tissues. (C) Quantitative analyses of CD8+ CD3+ T cell and (D) CD4+ Foxp3+ percentages in tumor tissues after treatment measured by flow cytometry. Cytokines (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-12 and (G) TGF-β levels detection in tumor tissues. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by analysis of ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test.

Conclusion

We developed a polymersome-micelle transformable pro-drug nanoplatform DPPA-TRPP/Tab for TME modulation, ICD generation and immune checkpoint blockade. The property of transformability resolved the dilemma between whether to use hydrophilic drug release in the TME for immunosuppressive reversal, or a hydrophobic chemotherapeutic for intracellular release to cause ICD. Tab was released from TRPP in the TME, where TRPP re-assembled into prodrug micelles for further internalization by tumor cells to induce ICD. The conjugated DOX was the ICD inducer as well as the hydrophobic segment, the relatively low content of which ensured the biosafety of this nanoplatform. DPPA-1 was able to shed from the TRPP surface when encountering a high concentration of H2O2 in the TME, and the act as an ICI. Compared with anti PD-L1, DPPA-1 has a lower cost of production, which would endow it an advantage during clinical implementation. The DPPA-TRPP/Tab nanoplatform improved the compound's tumor accumulation, suppressed CAFs formation, reduced immunosuppressive cytokine secretion, promoted CD8+ CD4+ T cell infiltration and decreased Tregs distribution, resulting in a potent antitumor effect. Remarkably, after DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment, there was a 60% CR ratio with prolonged survival time in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice when the initial tumor volume was around 100 mm3. The rechallenge-tumors were also notably suppressed compared with tumors in untreated mice. Even for mice with a larger initial tumor (~150 mm3), there was still a high antitumor activity observed after DPPA-TRPP/Tab treatment as compared with mice in the other groups. Thus, this study provides a new type of prodrug nanoplatform with transformable morphology to simultaneously induce CAFs inhibition, ICD and immune checkpoint blockade. The results suggest a clinical translatability of this “all-in-one” transformable prodrug platform for the treatment of malignant tumors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials and methods, schemes, figures and table.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52103191, 52103190), Start-up Grant (32340278) from Zhengzhou University, the National University of Singapore Start-up Grant (NUHSRO/2020/133/Startup/08), NUS School of Medicine Nanomedicine Translational Research Programme (NUHSRO/2021/034/TRP/09/Nanomedicine), and National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Centre Grant Programme (CG21APR1005).

References

- 1.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:97–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An J, Zhang K, Wang B, Wu S, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Liu J, Shi J. Nanoenabled Disruption of Multiple Barriers in Antigen Cross-Presentation of Dendritic Cells via Calcium Interference for Enhanced Chemo-Immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2020;14:7639–7650. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shao Y, Wang Z, Hao Y, Zhang X, Wang N, Chen K, Chang J, Feng Q, Zhang Z. Cascade Catalytic Nanoplatform Based on "Butterfly Effect" for Enhanced Immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10:2002171. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202002171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H, Song Q, Zheng C, Zhao B, Wu L, Feng Q, Zhang Z, Wang L. Implantable Bioresponsive Nanoarray Enhances Postsurgical Immunotherapy by Activating. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:2005747. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X, Yang K, Zhao R, Ji T, Wang X, Yang X, Zhang Y, Cheng K, Liu S, Hao J, Ren H, Leong KW, Nie G. Inducing enhanced immunogenic cell death with nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems for pancreatic cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2016;102:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian L, Wang Y, Sun L, Xu J, Chao Y, Yang K, Wang S, Liu Z. Cerenkov Luminescence-Induced NO Release from 32P-Labeled ZnFe(CN)5NO Nanosheets to Enhance Radioisotope-Immunotherapy. Matter. 2019;1:1061–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Han X, Dong Z, Xu J, Wang J, Liu Z. Hyaluronidase with pH-responsive Dextran Modification as an Adjuvant Nanomedicine for Enhanced Photodynamic-Immunotherapy of Cancer. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1902440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng H, Yang W, Zhou Z, Tian R, Lin L, Ma Y, Song J, Chen X. Targeted scavenging of extracellular ROS relieves suppressive immunogenic cell death. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4951. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18745-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Guo J, Huang L. Modulation of tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy focus on nanomaterial-based strategies. Theranostics. 2020;10:3099–3117. doi: 10.7150/thno.42998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Chen Q, Feng L, Liu Z. Nanomedicine for tumor microenvironment modulation and cancer treatment enhancement. Nano Today. 2018;21:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Q, Wang C, Zhang X, Chen G, Hu Q, Li H, Wang J, Wen D, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Yang G, Jiang C, Wang J, Dotti G, Gu Z. In situ sprayed bioresponsive immunotherapeutic gel for post-surgical cancer treatment. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14:89–97. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P, De Carvalho DD. TGF-beta-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4692. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06654-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Yang D, Fang Y, Lin X, Jin X, Wang Q, Wang X, Ke L, Shi K. Engineering Nanoparticles for Targeted Remodeling of the Tumor Microenvironment to Improve Cancer Immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:126–151. doi: 10.7150/thno.29431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Q, Chen F, Hou L, Shen L, Zhang X, Wang D, Huang L. Nanocarrier-Mediated Chemo-Immunotherapy Arrested Cancer Progression and Induced Tumor Dormancy in Desmoplastic Melanoma. ACS Nano. 2018;12:7812–7825. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:99–115. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, Wen L, Shao S, Tan Y, Meng T, Yang X, Liu Y, Liu X, Yuan H, Hu F. Inhibition of tumor-promoting stroma to enforce subsequently targeting AT1R on tumor cells by pathological inspired micelles. Biomaterials. 2018;161:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busek P, Mateu R, Zubal M, Kotackova L, Sedo A. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in cancer-Prospects and caveats. Front Biosci. 2018;23:1933–1968. doi: 10.2741/4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xin L, Gao J, Zheng Z, Chen Y, Lv S, Zhao Z, Yu C, Yang X, Zhang R. Fibroblast Activation Protein-alpha as a Target in the Bench-to-Bedside Diagnosis and Treatment of Tumors: A Narrative Review. Front Oncol. 2021;11:648187. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.648187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji T, Zhao Y, Ding Y, Wang J, Zhao R, Lang J, Qin H, Liu X, Shi J, Tao N, Qin Z, Nie G, Zhao Y. Transformable Peptide Nanocarriers for Expeditious Drug Release and Effective Cancer Therapy via Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Activation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:1050–1055. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1974–1982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazarika M, Chuk MK, Theoret MR, Mushti S, He K, Weis SL, Putman AH, Helms WS, Cao X, Li H, Zhao H, Zhao L, Welch J, Graham L, Libeg M, Sridhara R, Keegan P, Pazdur R. U.S. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma Following Progression on Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3484–3488. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inman BA, Longo TA, Ramalingam S, Harrison MR. Atezolizumab: A PD-L1-Blocking Antibody for Bladder Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1886–1890. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang W, He L, Ouyang J, Chen Q, Liu C, Tao W, Chen T. Triangle-Shaped Tellurium Nanostars Potentiate Radiotherapy by Boosting Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy. Matter. 2020;3:1725–1753. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hua Y, Lin L, Guo Z, Chen J, Maruyama A, Tian H, Chen X. In situ vaccination and gene-mediated PD-L1 blockade for enhanced tumor immunotherapy. Chinese Chem Lett. 2021;32:1770–1774. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang HN, Liu BY, Qi YK, Zhou Y, Chen YP, Pan KM, Li WW, Zhou XM, Ma WW, Fu CY, Qi YM, Liu L, Gao YF. Blocking of the PD-1/PD-L1 Interaction by a D-Peptide Antagonist for Cancer Immunotherapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:11760–11764. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng K, Ding Y, Zhao Y, Ye S, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Ji T, Wu H, Wang B, Anderson GJ, Ren L, Nie G. Sequentially Responsive Therapeutic Peptide Assembling Nanoparticles for Dual-Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18:3250–3258. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Liang C, Zhang Z, Chen Y, Hu Z, Yang Z. A Supramolecular Trident for Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31:2100729. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang W, Wei Y, Yang L, Zhang J, Zhong Z, Storm G, Meng F. Granzyme B-loaded, cell-selective penetrating and reduction-responsive polymersomes effectively inhibit progression of orthotopic human lung tumor in vivo. J Control Release. 2018;290:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun H, Zhang Y, Zhong Z. Reduction-sensitive polymeric nanomedicines: An emerging multifunctional platform for targeted cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;132:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng G, Zong W, Guo H, Li F, Zhang X, Yu P, Ren F, Zhang X, Shi X, Gao F, Chang J, Wang S. Programmed Size-Changeable Nanotheranostic Agents for Enhanced Imaging-Guided Chemo/Photodynamic Combination Therapy and Fast Elimination. Adv Mater. 2021;33:2100398. doi: 10.1002/adma.202100398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.An H, Mamuti M, Wang X, Yao H, Wang M, Zhao L, Li L. Rationally designed modular drug delivery platform based on intracellular peptide self-assembly. Exploration. 2021;1:20210153. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang N, Xiao W, Song X, Wang W, Dong X. Recent Advances in Tumor Microenvironment Hydrogen Peroxide-Responsive Materials for Cancer Photodynamic Therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020;12:15. doi: 10.1007/s40820-019-0347-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Pan Z, Liu Y. Advanced bioactive nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Exploration. 2021;1:20210089. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao R, Sun W, Zhang Z, Li X, Du J, Fan J, Peng X. Protein nanoparticles containing Cu(II) and DOX for efficient chemodynamic therapy via self-generation of H2O2. Chinese Chem Lett. 2020;31:3127–3130. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irvine DJ, Dane EL. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy with nanomedicine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:321–334. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo M, Wang H, Wang Z, Cai H, Lu Z, Li Y, Du M, Huang G, Wang C, Chen X, Porembka MR, Lea J, Frankel AE, Fu YX, Chen ZJ, Gao J. A STING-activating nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:648–654. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu N, Zhang Y, Li J, Gu W, Yue S, Li B, Meng F, Sun H, Haag R, Yuan J, Zhong Z. Daratumumab Immunopolymersome-Enabled Safe and CD38-Targeted Chemotherapy and Depletion of Multiple Myeloma. Adv Mater. 2021;33:e2007787. doi: 10.1002/adma.202007787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin Q, Liu Z, Chen Q. Controlled release of immunotherapeutics for enhanced cancer immunotherapy after local delivery. J Control Release. 2021;329:882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin JD, Cabral H, Stylianopoulos T, Jain RK. Improving cancer immunotherapy using nanomedicines: progress, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:251–266. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu H, Xia F, Zhang L, Fang C, Lee J, Gong L, Gao J, Ling D, Li F. A ROS-Sensitive Nanozyme-Augmented Photoacoustic Nanoprobe for Early Diagnosis and Therapy of Acute Liver Failure. Adv Mater. 2022;34:2108348. doi: 10.1002/adma.202108348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang C, Pu K. Recent Progress on Activatable Nanomedicines for Immunometabolic Combinational Cancer. Small Struct. 2020;1:2000026. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyu Shim M, Yang S, Sun IC, Kim K. Tumor-activated carrier-free prodrug nanoparticles for targeted cancer Immunotherapy: Preclinical evidence for safe and effective drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;183:114177. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Q, Saeed M, Song R, Sun T, Jiang C, Yu H. Dynamic covalent chemistry-regulated stimuli-activatable drug delivery systems for improved cancer therapy. Chinese Chem Lett. 2020;31:1051–1059. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S, Hu X, Wei W, Ma G. Transformable vesicles for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;179:113905. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang W, Deng H, Zhu S, Lau J, Tian R, Wang S, Zhou Z, Yu G, Rao L, He L, Ma Y, Chen X. Size-transformable antigen-presenting cell-mimicking nanovesicles potentiate effective cancer immunotherapy. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabd1631. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan J, Fan Y, Wei Z, Li Y, Li X, Wang L, Wang H. Transformable peptide nanoparticles inhibit the migration of N-cadherin overexpressed cancer cells. Chinese Chem Lett. 2020;31:1787–1791. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong N, Zhang Y, Teng X, Wang Y, Huo S, Qing G, Ni Q, Li X, Wang J, Ye X, Zhang T, Chen S, Wang Y, Yu J, Wang PC, Gan Y, Zhang J, Mitchell MJ, Li J, Liang XJ. Proton-driven transformable nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2020;15:1053–1064. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-00782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang W, Zhu G, Wang S, Yu G, Yang Z, Lin L, Zhou Z, Liu Y, Dai Y, Zhang F, Shen Z, Liu Y, He Z, Lau J, Niu G, Kiesewetter DO, Hu S, Chen X. In situ Dendritic Cell Vaccine for Effective Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2019;13:3083–3094. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials and methods, schemes, figures and table.