Abstract

Background and Aim

Potassium‐competitive acid blocker (PCAB) is a recent alternative to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for potent acid suppression. The current systematic review and meta‐analysis aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of PCAB versus PPI in treating gastric acid‐related diseases.

Methods

We searched up to June 5, 2022, for randomized controlled trials of gastric acid‐related diseases that included erosive esophagitis, symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcers, and Helicobacter pylori infection. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was evaluated for the efficacy outcome and treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) as the safety outcome. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the study findings.

Results

Of the 710 screened studies, 19 studies including 7023 participants were analyzed. The RRs for the healing of erosive esophagitis with Vonoprazan versus PPI were 1.09 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–1.14), 1.03 (95% CI 1.00–1.07), and 1.02 (95% CI 1.00–1.05) in Weeks 2, 4, and 8, respectively. There were no differences in the improvement of GERD symptoms and healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers between PCAB and PPI. The pooled eradication rates of H. pylori were significantly higher in Vonoprazan versus PPI first‐line treatment (RR 1.13; 95% CI 1.04–1.22). The overall RR of TEAEs with Vonoprazan versus PPI was 1.08 (95% CI 0.89–1.31). Overall, the risk of bias was low to some concerns. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the study's conclusion.

Conclusion

Vonoprazan is superior to PPI in first‐line H. pylori eradication and erosive esophagitis but non‐inferior in other gastric acid‐related diseases. Likewise, short‐term safety is comparable in both treatment groups.

Keywords: gastric acid‐related diseases, meta‐analysis, potassium‐competitive acid blocker, proton pump inhibitor, vonoprazan

Introduction

The preferred treatment for many gastric diseases, especially gastric acid‐related diseases, has been the proton pump inhibitor (PPI). 1 , 2 , 3 Such gastric acid‐related conditions are not limited to symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), erosive esophagitis, dyspepsia, chronic gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and Helicobacter pylori infection. 4 , 5 However, despite being an effective acid suppression and only 1–3% of short‐term adverse events, a recent umbrella review indicated more longer‐term risks with PPI use, especially fractures and kidney disease in the elderly, and a more severe COVID‐19 disease. 6 , 7 Furthermore, an estimated 10–40% of GERD patients have an incomplete or no response to standard doses of PPI, otherwise termed refractory GERD. 8 Thus, the aforementioned limitations warrant an alternative acid‐suppressive drug superior to or at least similar in efficacy to PPI.

Potassium‐competitive acid blocker (PCAB) could be the potential alternative to PPI. PCABs are reversible, competitive antagonists of the H+/K+ ATPase and have more potent, rapid‐acting, and sustained acid suppression. 9 Vonoprazan, probably the best‐known PCAB, received its first approval for use in Japan in 2015. Previous meta‐analyses have confirmed the benefits of Vonoprazan alone (no other PCABs) and only in several disorders, including GERD, H. pylori eradication, and post‐endoscopic submucosal dissection ulcers. 10 , 11 , 12 Furthermore, non‐randomized studies were included in previous meta‐analyses, prone to biases and heterogeneity, among other limitations. Therefore, the current systematic review and meta‐analysis included only robust randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of all studied PCABs. The aims were to assess the efficacy (superiority or non‐inferiority) and safety of PCAB compared with PPI in treating gastric acid‐related diseases.

Methods

Before writing this systematic review and meta‐analysis, a protocol was prospectively designed and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42022307265). 13 We have followed the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA; Table S1). 14

Search strategy and selection criteria

Only RCTs of gastric acid‐related diseases randomized to either PCABs or PPIs were searched and selected if the inclusion criteria were satisfied. Gastric acid‐related disorders included erosive esophagitis, H. pylori infection, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and symptomatic GERD. All studied PCABs were included, that is, Vonoprazan, Soraprazan, Revaprazan, Tegoprazan, Keverprazan, and Linaprazan. Meanwhile, any PPIs as the comparator were Omeprazole, Esomeprazole, Lansoprazole, Rabeprazole, Pantoprazole, Dexlansoprazole, and Ilaprazole. For H. pylori studies, only RCTs that compared therapies (regardless of dual or triple, or quadruple therapies and their durations) with the exact dosages and drugs, aside from the PCAB or PPI, were included. Hence, studies that compared different numbers of regimens were excluded (i.e. dual vs triple or dual vs quadruple or triple vs quadruple). From inception to June 5, 2022, studies published in English were searched using the following electronic databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane Library. The search terms are presented in Figure S1 and include the following keywords: gastric acid‐related diseases, PCAB, PPI, and clinical trials. Additional studies were also identified through manual hand‐searching, from relevant systematic reviews or meta‐analyses and the reference lists of included studies.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

All retrieved articles were imported into the Endnote 20 (Clarivate, Boston, USA) software, and duplicates were removed. Subsequently, two independent authors (D. M. S. and A. F. S.) screened the titles and abstracts, reviewed the full texts, performed data extraction, and assessed the risk of bias. The following details were extracted: study identifier, publication date, recruitment period, study location, study design, baseline characteristics of the participants (number of participants, age, and gender), types of gastric acid‐related disease, treatment regimen given, outcome measurement, and the treatment outcome. To rate the risk of bias, the Cochrane's Risk of Bias (RoB) tool 2.0 was used to assess the risk of bias in included studies. 15 The tool evaluated five major domains, which were (i) randomization process, (ii) deviations from intended interventions, (iii) missing outcome data, (iv) measurement of the outcome, and (v) the selection of the reported result. For any disagreement, the reviewers would reconcile until a mutual agreement was achieved.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest for this review were the endoscopic healing rates of erosive esophagitis and gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers, the eradication rate of H. pylori (as assessed by urea breath test), and the improvement of any GI symptoms experienced by symptomatic GERD patients (as reported by patients). Only intention‐to‐treat (ITT) and full analysis set (FAS) outcome data were extracted and included in the analysis for efficacy outcomes. ITT outcomes were defined as data available for all randomization patients; however, many studies had minor variations concerning the definition of FAS outcome, which ultimately is, as described by the European Medicines Agency Guidance on Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials, as complete and close as possible to the ITT analysis of including all randomized subjects. 16 The ITT outcome data would be used for analysis where the study presented the ITT and FAS data. In addition, the pooled healing and eradication rates and the calculated risk ratio (RR) were determined from extracted data. The secondary outcome was the treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), where we calculated the RRs from the available data. Only ITT and safety analysis set (SAS) outcome data were extracted and included in the analysis for safety outcomes. ITT data would be used if studies reported both datasets. SAS outcome data included all randomized patients with at least one safety assessment after randomization. Additionally, for studies that reported different doses of PCAB (such as Vonoprazan 20 mg, Linaprazan 75 mg, and/or Tegoprazan 50 mg), their inclusion in the meta‐analysis would be based on clinical judgment. However, due to different efficacy and safety of individual PCAB, pooling of studies in a meta‐analysis would be performed only if two or more studies had used the same type of PCAB.

Data analysis

Data were presented in narrative form, and findings were summarized in tables. Due to the study's paucity and the heterogeneity of the improvement of GI symptoms in symptomatic GERD, we did not perform a meta‐analysis for that particular outcome of interest. Quantitative synthesis and statistical analyses of the remaining outcomes were performed using the R program v.4.1.2 (Vienna, Austria). 17 To summarize the pooled effect size, the random‐effects model was used. For data with dichotomized outcomes, we presented the data as proportion. We used the Mantel–Haenszel method to calculate the pooled RRs and 95% confidence interval (CI) of healing rates, eradication rates, and TEAEs. The heterogeneity of included studies was calculated using the Cochrane χ2 and I 2. All statistical analyses were two‐tailed and considered significant with P < 0.05, except for the Cochrane χ2 heterogeneity significance level, which was set to P < 0.10.

Due to study paucity (k < 10), we did not perform a publication bias assessment qualitatively using the funnel plot or quantitatively using Egger's linear regression and Begg's rank tests. Sensitivity analysis using the leave‐one‐out analysis was used to assess the robustness of the results. Furthermore, subgroup analyses (if k ≥ 2 in both subgroups) were performed to analyze the effect estimate based on the study location, the publication type, the study's risk of bias, and the specific intervention–comparator combination or type of PCAB as the comparator. Differences in subgroup analyses were considered significant if the interaction was P < 0.10.

Results

Study selection and baseline characteristics

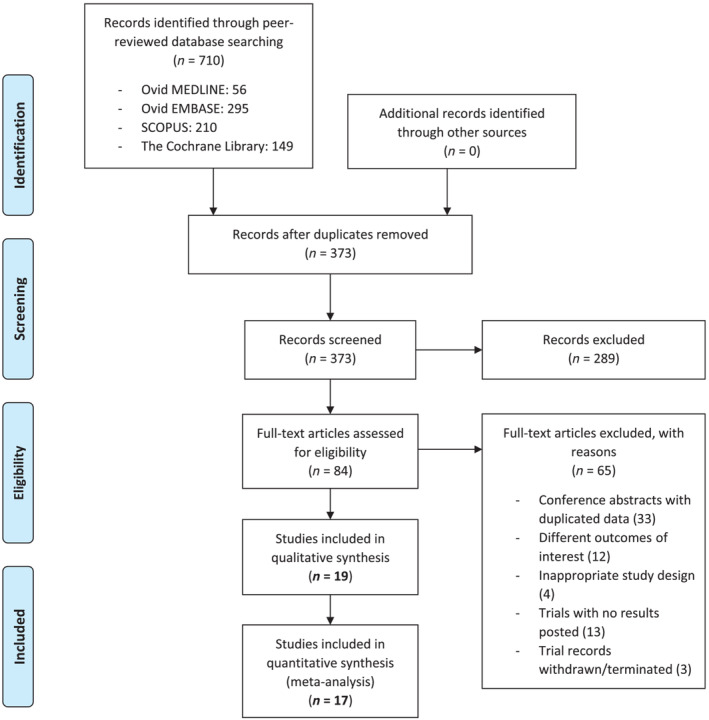

From a total of 686 potential studies screened, 19 studies with 7023 patients were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Of the gastric acid‐related diseases, six were erosive esophagitis, 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 two were symptomatic GERD, 24 , 25 nine were H. pylori infection, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 three were gastric ulcers, 34 , 35 , 36 and the remaining two were duodenal ulcers 33 , 35 (Table 1). All studies were peer‐reviewed published clinical trials except for two unpublished clinical trials. 25 , 34 Nine of the 19 studies were from Japan, 19 , 20 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 35 eight were from other parts of Asia, 21 , 22 , 23 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 and only two were from the Western countries 18 , 25 (European countries and the USA). The most common drug–drug comparison was Vonoprazan 20 mg–Lansoprazole 30 mg (8/19 studies; 42.1%). Overall, the risk of bias was generally low‐to‐some concerns; 10 studies (52.6%) had low risks of bias. We did not identify any studies with a high risk of bias. The overall risk of bias and the individual study's risk of bias are presented in Figure S2. Of the 7023 patients, 4271 (60.8%) received PCAB therapy, and 2752 (39.2%) received PPI therapy. The duration of treatment for PCAB and PPI ranged from 7 days (in H. pylori eradication) to 8 weeks (in erosive esophagitis and peptic ulcers). Study participants' baseline characteristics (age and gender) did not differ between the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of study search and study selection process (flow chart). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies investigating the efficacy and safety of PCAB and PPI in gastric acid‐related diseases

| Gastric acid‐related disease | Study identifier | Country | Treatment (PCAB/PPI) | Duration | N | Age (in years); mean ± SD/(range) | Male; N (%) | RoB2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erosive esophagitis | Kahrilas (2007) | 188 centers in the USA, Canada, France, Germany, Norway, the UK, Finland, Italy, Sweden, and Denmark | AZD0865 75 mg | 8 weeks | 375 | 45.8 ± 13.1 | 236 (63) | ? |

| AZD0865 50 mg | 8 weeks | 377 | 47.4 ± 12.2 | 245 (65) | ||||

| AZD0865 25 mg | 8 weeks | 386 | 47.3 ± 12.1 | 233 (60) | ||||

| ESO 40 mg | 8 weeks | 376 | 46.5 ± 13.2 | 243 (65) | ||||

| Ashida (2015) | Japan | VPZ 40 mg | 8 weeks | 146 | 57.6 ± 12.8 | 114 (78) | ? | |

| VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 154 | 58.3 ± 13.9 | 115 (75) | ||||

| VPZ 10 mg | 8 weeks | 145 | 57.3 ± 13.0 | 113 (78) | ||||

| VPZ 5 mg | 8 weeks | 148 | 57.9 ± 13.0 | 110 (74) | ||||

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 140 | 55.8 ± 13.9 | 99 (71) | ||||

| Ashida (2016) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 207 | 58.3 ± 13.8 | 137 (66) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 202 | 57.4 ± 13.2 | 154 (76) | ||||

| Lee (2019) | South Korea | TPZ 100 mg | 8 weeks | 102 | 52.8 (20–74) | 66 (65) | ‐ | |

| TPZ 50 mg | 8 weeks | 99 | 52.7 (21–74) | 62 (63) | ||||

| ESO 40 mg | 8 weeks | 99 | 50.4 (21–75) | 53 (54) | ||||

| Xiao (2020) | 56 centers in China, South Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia | VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 244 | 54.1 ± 13.2 | 176 (72) | ? | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 237 | 53.8 ± 12.5 | 179 (76) | ||||

| Chen (2022) | 44 sites in China | KPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 119 | 49.7 ± 12.1 | 99 (83) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 119 | 48.8 ± 12.3 | 91 (76) | ||||

| GERD | Sakurai (2019) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 4 weeks | 22 | 58.0 ± 13.8 | 6 (27) | ? |

| ESO 20 mg | 4 weeks | 25 | 54.7 ± 13.2 | 10 (40) | ||||

| NCT02743949 | 33 centers in Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, and the UK | VPZ 40 mg | 4 weeks | 85 | 52.0 ± 14.7 | 32 (38) | ‐ | |

| VPZ 20 mg | 4 weeks | 85 | 51.8 ± 14.1 | 34 (40) | ||||

| ESO 40 mg | 4 weeks | 86 | 53.9 ± 13.9 | 38 (44) | ||||

| Helicobacter pylori | Murakami (2016) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 329 | 55.2 ± 12.3 | 196 (60) | ‐ |

| LPZ 30 mg | 7 days | 321 | 53.9 ± 12.9 | 194 (60) | ||||

| Maruyama (2017) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 72 | 58 (32–80) | 41 (57) | ? | |

| RPZ 20 mg or LPZ 30 mg | 7 days | 69 | 60 (36–77) | 40 (58) | ||||

| Sue (2018) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 55 | 64.3 ± 12.3 | 37 (68) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg or RPZ 10 mg or ESO 20 mg | 7 days | 51 | 61.9 ± 13.3 | 35 (69) | ||||

| Sue (2019) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 33 | 62.4 ± 14.1 | 18 (55) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg or RPZ 10 mg or ESO 20 mg | 7 days | 30 | 64.0 ± 12.3 | 15 (50) | ||||

| Hojo (2020) | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 23 | 56.0 ± 10.9 | 12 (52) | ? | |

| RPZ 10 mg | 7 days | 23 | 57.2 ± 14.4 | 14 (61) | ||||

| Bunchorntavakul (2021) | Thailand | VPZ 20 mg | 7 days | 61 | 54.2 ± 12.3 | 26 (43) | ? | |

| OMZ 20 mg | 14 days | 61 | 56.8 ± 13.3 | 31 (51) | ||||

| Huh (2021) | Korea | VPZ 20 mg | 14 days | 15 | 32.8 ± 6.9 | 14 (93) |

‐ |

|

| LPZ 30 mg | 14 days | 15 | 33.3 ± 8.6 | 14 (93) | ||||

| Hou (2022) † | 52 hospitals in China, South Korea, and Taiwan | VPZ 20 mg | 6 weeks | 226 | NR | NR | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 6 weeks | 229 | NR | NR | ||||

| NCT03050307 | 60 centers in China, Korea, and Taiwan | VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 115 | NR | NR | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 119 | NR | NR | ||||

| Gastric ulcer | Miwa (2017) † | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 244 | 58.2 ± 13.2 | 163 (67) | ? |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 238 | 58.6 ± 13.5 | 170 (71) | ||||

| Cho (2020) | South Korea | TPZ 100 mg | 8 weeks | 93 | 54.11 | 61 (66) | ? | |

| TPZ 50 mg | 8 weeks | 88 | 53.39 | 58 (66) | ||||

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 85 | 54.22 | 47 (55) | ||||

| NCT03050307 | 60 centers in China, Korea, and Taiwan | VPZ 20 mg | 8 weeks | 115 | 54.0 ± 13.7 | 86 (75) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 8 weeks | 119 | 53.5 ± 13.4 | 92 (77) | ||||

| Duodenal ulcer | Miwa (2017) † | Japan | VPZ 20 mg | 6 weeks | 184 | 49.9 ± 14.6 | 125 (68) | ? |

| LPZ 30 mg | 6 weeks | 188 | 50.2 ± 14.8 | 120 (64) | ||||

| Hou (2022) † | 52 hospitals in China, South Korea, and Taiwan | VPZ 20 mg | 6 weeks | 265 | 42.0 ± 12.2 | 166 (63) | ‐ | |

| LPZ 30 mg | 6 weeks | 268 | 41.4 ± 12.9 | 176 (66) |

Same study.

‐ indicates low risk of bias; ? indicates some risk of bias. ESO, Esomeprazole; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; KPZ, Keverprazan; LPZ, Lansoprazole; NR, not reported; PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RoB2, Cochrane's Risk of Bias 2 tool; RPZ, Rabeprazole; TPZ, Tegoprazan; VPZ, Vonoprazan.

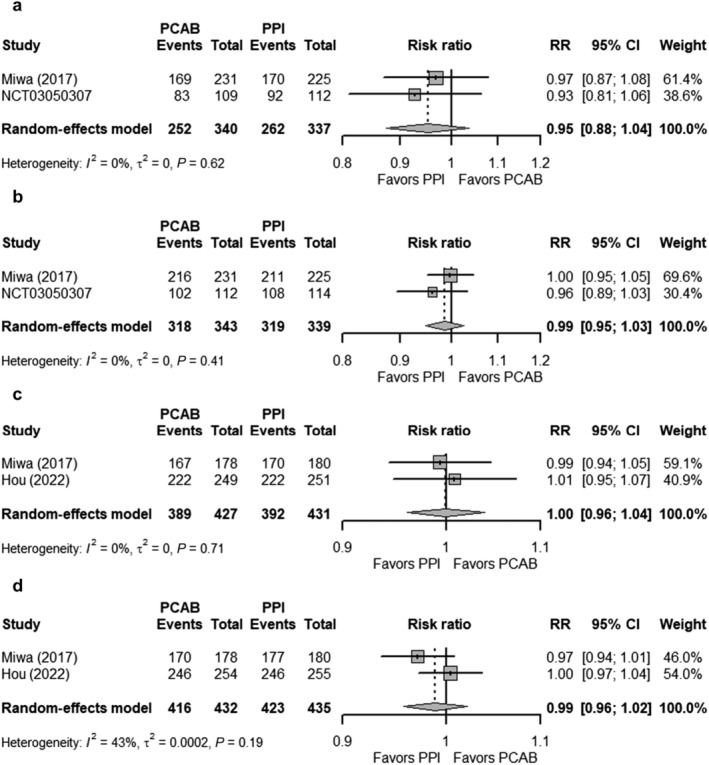

Erosive esophagitis

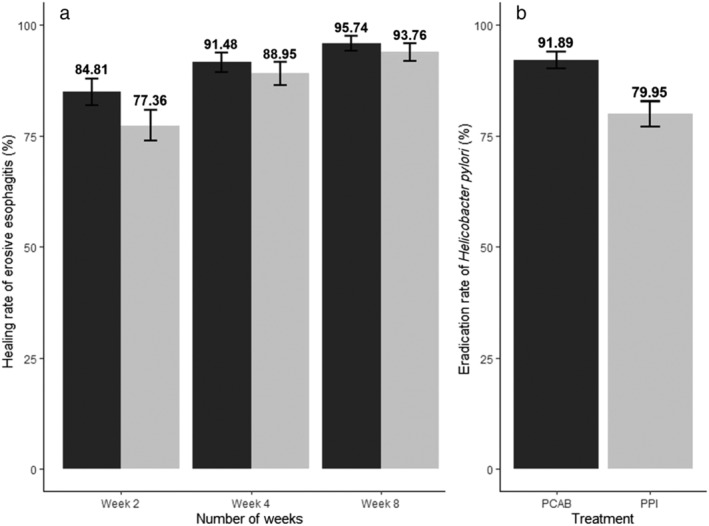

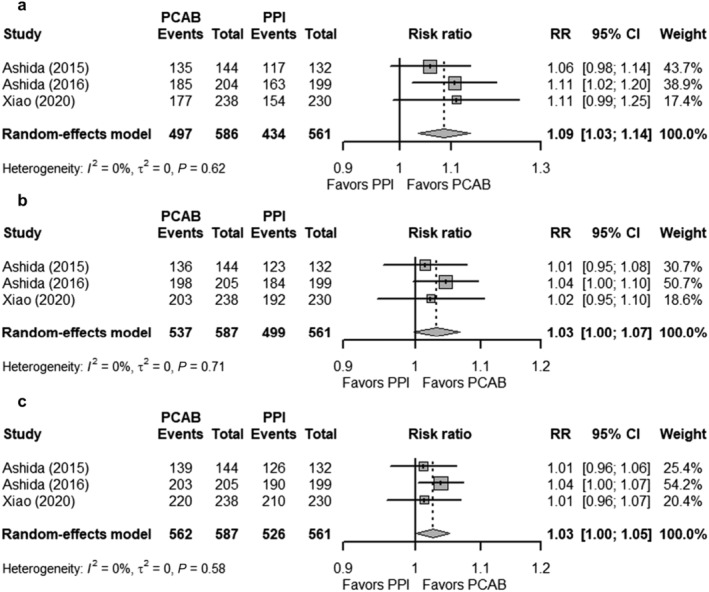

Overall, six studies investigated the use of PCAB versus PPI for healing of erosive esophagitis; three of which used Vonoprazan, while the remaining three used Linaprazan (AZD0865), Keverprazan, and Tegoprazan. The six studies reported three different endpoints (healing rates at Weeks 2, 4, and 8). The pooled healing rates of erosive esophagitis were higher in the Vonoprazan group than in the PPI group for all the three different endpoints (Fig. 2a; Week 2: 84.81% vs 77.36%; Week 4: 91.48% vs 88.95%; Week 8: 95.74% vs 93.76%). However, the pooled RRs showed better healing rates in the Vonoprazan group only in Week 2 (RR 1.09; 95% CI 1.03–1.14) compared with Week 4 (RR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00–1.07) and Week 8 (RR 1.02; 95% CI 1.00–1.05) (Fig. 3). Sensitivity analysis did not show any significant changes to the pooled RR, and the conclusion of the findings for healing rates at Weeks 2, 4, and 8 (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Bar graphs denoting (a) the crude/pooled healing rate of erosive esophagitis in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI and (b) the crude/pooled eradication rate of

Helicobacter pylori

infection in patients receiving first‐line treatment of ( ) Vonoprazan (PCAB) and (

) Vonoprazan (PCAB) and ( ) PPI. The healing rate and eradication rate are presented in % with its 95% confidence interval. PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

) PPI. The healing rate and eradication rate are presented in % with its 95% confidence interval. PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Forest plots comparing the healing rates of erosive esophagitis in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI at (a) Week 2, (b) Week 4, and (c) Week 8. The RR and 95% CI for each study are presented in logarithmic scale. The pooled RRs are derived from the random‐effects model. CI, confidence interval; PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RR, risk ratio.

At Week 4, there were no differences in the healing rates of erosive esophagitis between PPI, and Linaprazan (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.93–1.07), Tegoprazan (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.90–1.11), and Keverprazan (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.90–1.14). Non‐inferiority was also shown at Week 8 between PPI, and Tegoprazan (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.96–1.10) and Keverprazan (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.99–1.14).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

The two included studies have used different endpoints to improve GI symptoms, and, due to the heterogeneity between studies, these were not pooled into the meta‐analysis (Table S2). In the first study, Sakurai et al. 24 reported no significant differences in symptom relief at 4 weeks between patients receiving Vonoprazan 20 mg and Esomeprazole 20 mg (sufficient relief 81.8% vs 88.0% and complete resolution 50% vs 64%). Furthermore, the numerical change in the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD (FSSG) between the Vonoprazan group and the Esomeprazole group (71.9% vs 72.8%) was not statistically different. Likewise, in the second unpublished clinical trial (NCT02743949) comparing Vonoprazan 40 mg or Vonoprazan 20 mg with Esomeprazole 40 mg, the 24‐h heartburn‐free periods (Vonoprazan 40 mg 38.4% or 20 mg 36.7% vs Esomeprazole 40 mg 36.5%) were not significantly different between the groups. Similarly, the percentage of participants with > 1 sustained resolution of heartburn (Vonoprazan 40 mg 31.8% or 20 mg 30.6% vs Esomeprazole 32.6%) was not significantly different between the groups.

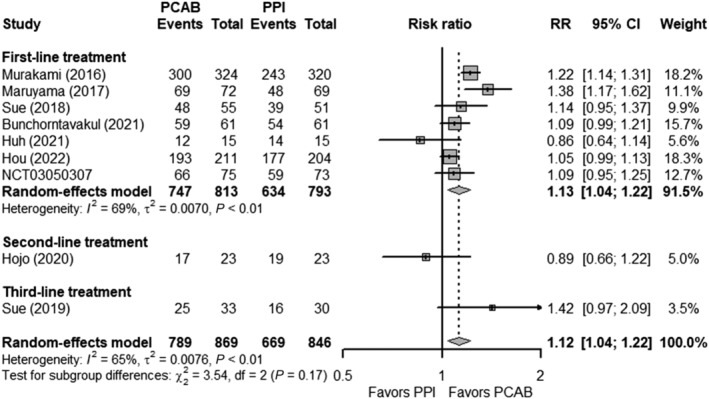

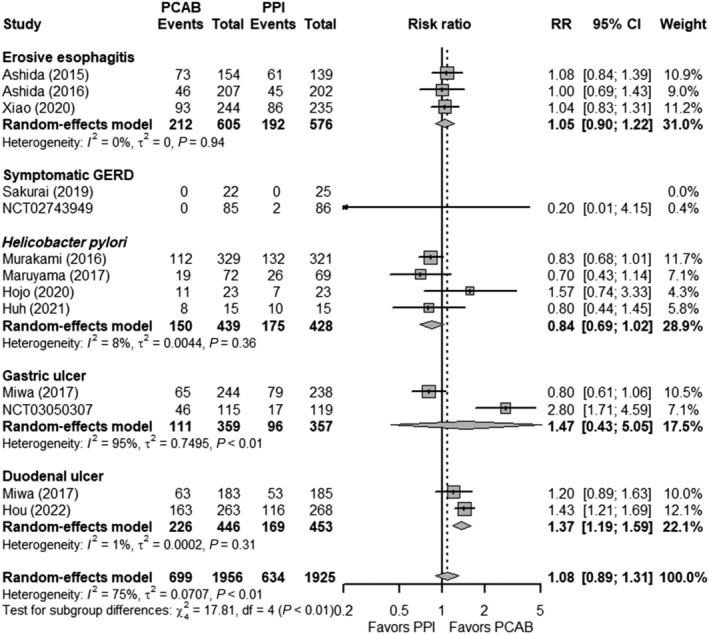

Helicobacter pylori eradication

A total of 869 and 846 patients from nine studies were randomized to PCAB‐based and PPI‐based therapy, respectively. Seven of the nine studies investigated first‐line treatment for H. pylori , while one study investigated second‐line and third‐line treatment. The pooled eradication rate of H. pylori for first‐line treatment was 91.89% in the PCAB‐based group and 79.95% in the PPI‐based group (Fig. 2b). The overall RR comparing the two groups was 1.13 (95% CI 1.04–1.22) in first‐line treatment, 0.89 (95% CI 0.66–1.22) in second‐line treatment, and 1.42 (95% CI 0.97–2.09) in third‐line treatment (Fig. 4). There was significant heterogeneity among studies exploring first‐line treatment of H. pylori (P < 0.01; I 2 = 69%). Sensitivity analysis comparing the eradication rate of H. pylori did not yield any substantial changes to the primary analysis for first‐line treatment (Fig. S4A). Subgroup analyses for first‐line treatment by drug–drug comparison and risk of bias of included studies did not show any significant subgroup differences (Fig. S4B). However, studies from Japan were shown to have a significantly higher RR than those conducted outside of Japan (1.24; 95% CI 1.14–1.34 vs 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.12; subgroup interaction P < 0.01). Additionally, restricting the analysis to studies that compared only triple therapies with the same treatment duration in both the PCAB and PPI groups showed a greater pooled RR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.14–1.34) (Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Forest plots comparing the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI as first‐line, second‐line, and third‐line treatment. The RR and 95% CI for each study are presented in logarithmic scale. The pooled RRs are derived from the random‐effects model. CI, confidence interval; PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RR, risk ratio.

Gastric and duodenal ulcers

Of four studies, two were gastric ulcers, one was duodenal ulcer, and one analyzed both gastric and duodenal ulcers. All studies investigated Vonoprazan as the PCAB, while only one study by Cho et al. used Tegoprazan and thus was not included in the pooled analysis. The healing rates of GI ulcers were assessed at Weeks 2, 4, and 6 for duodenal ulcers but at Week 8 for gastric ulcers. In Week 2, for the Vonoprazan group, the healing rates of gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers were 29.9% and 66.3%, respectively, compared with the PPI group, 32.4% and 63.9%, respectively. At Weeks 4 and 8, the healing rates of gastric and duodenal ulcers did not differ between the two groups (Fig. 5). The healing rates of gastric ulcers at Weeks 4 and 8 also did not differ in those receiving Tegoprazan and PPI.

Figure 5.

Forest plots comparing the healing rates of gastrointestinal ulcers in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI at (a) GU ‐ Week 4, (b) GU ‐ Week 8, (c) DU ‐ Week 4, and (d) DU ‐ Week 8. The RR and 95% CI for each study are presented in logarithmic scale. The pooled RRs are derived from the random‐effects model. CI, confidence interval; DU, duodenal ulcer; GU, gastric ulcer; PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RR, risk ratio.

Safety of potassium‐competitive acid blocker versus proton pump inhibitor

Fifteen studies reported TEAEs in 4519 patients receiving PCABs and PPIs, two and one studies of which reported safety endpoints on Tegoprazan and Keverprazan, respectively, while the remainder was done with Vonoprazan. The prevalence of TEAEs for the Vonoprazan and PPI groups was 35.7% and 32.9%, respectively. The RRs of TEAEs comparing the Vonoprazan group versus the PPI group were 1.05 (95% CI 0.90–1.22), 0.20 (95% CI 0.01–4.15), 0.84 (95% CI 0.69–1.02), 1.47 (95% CI 0.43–5.05), and 1.37 (95% CI 1.19–1.59) for erosive esophagitis, symptomatic GERD, H. pylori eradication, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcers, respectively (Fig. 6). The overall RR for all Vonoprazan studies reporting TEAEs was 1.08 (95% CI 0.89–1.31). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (P < 0.01; I 2 = 75). Sensitivity analysis did not change the conclusion (Fig. S6A). Furthermore, subgroup analyses by drug–drug comparison, study location, publication type, and risk of bias showed no significant difference in the RRs (interaction P > 0.10) (Fig. S6B). The overall RR for all Tegoprazan and Keverprazan studies reporting TEAEs was 0.84 (95% CI 0.60–1.17) and 1.37 (95% CI 0.92–2.03), respectively (Fig. S7).

Figure 6.

Forest plots comparing the treatment‐emergent adverse events in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI. The RR and 95% CI for each study are presented in logarithmic scale. The pooled RRs are derived from the random‐effects model. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the specific gastric acid‐related disease. CI, confidence interval; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PCAB, potassium‐competitive acid blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

There are several key findings in the current systematic review and meta‐analysis. First, the comparative efficacy of Vonoprazan (most studied PCAB) versus PPI seems to vary among different gastric acid‐related diseases. On the one hand, superiority in the eradication rate of H. pylori was demonstrated with Vonoprazan‐based versus PPI‐based first‐line therapy (approximately 13% greater eradication rate). On the other hand, non‐inferiority of PCAB over PPI was shown in the healing rates of erosive esophagitis, GERD, and gastric and duodenal ulcers. Second, the short‐term safety rates based on TEAEs were comparable between the two treatment groups. Third, the sensitivity and subgroup analyses further confirmed the aforementioned observations.

The variations in comparative efficacy between PCAB and PPI in different disorders might not be all surprising. PCABs are faster in onset and more potent than PPIs. These properties likely impact therapy efficacy, as demonstrated in the current review. Furthermore, pH targets for healing of ulcers (pH > 3 for 12 h/day) are comparatively different from erosive esophagitis (pH > 4 for 18 h/day), as is time to response for gastric versus duodenal ulcers. 5 As such, PCABs may provide better responses to certain gastric acid‐related diseases than others.

There are other interesting findings. Of note, despite showing higher healing rates of erosive esophagitis in the Vonoprazan group compared with the PPI group across Weeks 2, 4, and 8, however, there was only substantial evidence to demonstrate superiority in Week 2. PCAB needed only 1 day to reach maximal acid suppression compared with 3–5 days with PPI. 9 , 37 Furthermore, PCAB does not require acid and proton pump activation to achieve the desired effect; thus, it has a faster acid‐suppressive effect. 37 , 38 These pharmacokinetic characteristics of PCAB could explain the better and quicker healing of erosive esophagitis being evident by Week 2 over PPI. However, PPI was able to catch up with recovery over time, as evident from healing rates in Weeks 4 and 8.

In addition, PCAB showed comparable efficacy over PPI in treating and maintaining erosive esophagitis. For example, a follow‐up study by Ashida et al. showed that Vonoprazan 20 mg was significantly more effective than Lansoprazole 15 mg in preventing erosive esophagitis recurrence at 24 weeks of maintenance period. 39 Despite the effectiveness in erosive esophagitis, the rate of symptom relief in GERD patients receiving PCAB versus PPI was similar or non‐inferior. Sakurai et al. and an unpublished clinical trial failed to demonstrate any statistical significance of GERD symptoms in PCAB over PPI. 25 However, in smaller studies on PPI‐resistant or refractory GERD patients, vonoprazan showed a more potent gastric suppression and better symptom improvement than PPI. 40 , 41 PCAB is probably the better choice because of the limitations of PPIs, such as short half‐lives, requiring acid activation and inhibiting only activated proton pumps, and clinical variability of CYP2C19 polymorphism. 41 PCAB might be a suitable replacement for PPI in a subset of patients where refractory GERD is due to the extensive metabolism of the CYP2C19. 40 It can be concluded that while PPI remains effective for symptom relief of GERD, PCAB could be the alternative in cases where GERD is resistant or refractory to PPI because of its limitations.

A key finding in the current meta‐analysis is the more effective eradication of H. pylori with Vonoprazan‐based versus PPI‐based first‐line therapy. Effective acid suppression is an essential component of H. pylori eradication. More potent and quicker acid inhibition stimulates the growth of H. pylori , which in turn enhances the bactericidal effects of growth‐dependent antibiotics such as amoxicillin. 4 , 42 In addition, our analysis suggested that Vonoprazan was similar or non‐inferior to PPI for second‐line and third‐line treatment. The choice of antibiotics may explain the identical rates; however, we recognized that limited data were available for second‐line and third‐line therapy. Although amoxicillin is a known growth‐dependent antibiotic, metronidazole, on the other hand, does not depend on the growth or stationary phase of H. pylori . Hence, the efficacy of metronidazole is unaffected by intragastric pH, which explains why acid suppression with PCAB could not improve the already high eradication rate of second‐line therapy in Hojo et al. 30

The healing rates of gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients receiving Vonoprazan versus PPI were similar for all weeks (Weeks 2, 4, and 6 for duodenal ulcers or Week 8 for gastric ulcers). However, the studies have combined both H. pylori ‐positive and H. pylori ‐negative ulcers. From the subgroup analyses focusing only on H. pylori ‐positive patients, PCAB was superior to PPI in the ulcer healing rates.

Vonoprazan was generally well tolerated; the overall prevalence of TEAE was 35.7% and 32.9% for PCAB and PPI, respectively, and did not significantly differ between the groups. TEAEs were substantially more significant in patients with duodenal ulcers receiving Vonoprazan than PPI. The RCTs in the current meta‐analysis only reported short‐term adverse events as the longest duration of PCAB use included in this study was 8 weeks. There is increasing safety concern associated with the long‐term use of PPIs, especially the risk of osteoporotic fractures and kidney disease among the elderly and a likely more severe course of COVID‐19 infection. 6 Unfortunately, the same cannot be inferred for the safety concerns related to long‐term Vonoprazan use as the safety data are minimal. A profound gastric inhibition and hypergastrinemia associated with PCAB may result in longer‐term issues, which have yet to be elucidated. However, from the present data, we may conclude that Vonoprazan is generally safe for short‐term use in gastric acid‐related diseases. Still, caution is needed if used for duodenal ulcer patients.

There are limitations to the current meta‐analysis. First, studies published in a language other than English were excluded, which could result in potential geographical bias as other studies could be missed. Second, there were limited studies for erosive esophagitis, GERD, and GI ulcers, which could cause our results to be overestimated. However, compared with previous meta‐analyses, which only included Vonoprazan as the only type of PCAB, other PCABs such as Linaprazan, Keverprazan, and Tegoprazan, which are available in markets outside of Japan, were also analyzed despite the limited studies available. Thus, more studies are needed to further establish the comparative efficacy and safety for other PCABs aside from Vonoprazan. Additionally, this meta‐analysis utilized sensitivity analysis to confirm the robustness of the analysis. Third, analysis of efficacy of PPIs affected by CYP2C19 genotypes was not performed; furthermore, PCABs were generally not affected by CYP2C19 genotypes. 43 Finally, non‐gastric acid‐related disorders, including aspirin‐induced or non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug‐induced gastric ulcers, and functional GI disorders were not included in the current meta‐analysis.

Conclusion

Vonoprazan is not inferior to PPI in healing erosive esophagitis and gastric and duodenal ulcers and improving GERD symptoms. Still, Vonoprazan is superior to PPI in the eradication rate of H. pylori infection using first‐line treatment. Vonoprazan is also relatively safe compared with PPI; however, only short‐term effects were evaluated. Further RCTs with larger samples, in different populations, and more variable use of PCABs (other than Vonoprazan) are needed to confirm findings of PCAB being the more potent and quicker acid suppressant and the alternative to PPIs in PPI‐refractory conditions. Likewise, long‐term safety data of PCABs are greatly needed.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Search strategy.

Figure S2. Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool assessment for included studies.

Figure S3. Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies comparing the healing rates of erosive esophagitis in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI at (A) Week 2, (B) Week 4 and (C) Week 8.

Figure S4. (A) Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies comparing the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line treatment Vonoprazan and PPI. (B) Subgroup analysis for the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line Vonoprazan and PPI by the drug–drug comparison, study location, and risk of bias.

Figure S5. Forrest plots showing the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line treatment of Vonoprazan and PPI. Analysis was restricted to studies which compared only triple therapies with the same treatment duration in both groups.

Figure S6. (A) Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies reporting the TEAEs in patients receiving PCAB and PPI. (B) Subgroup analysis for TEAEs in patients receiving PCAB and PPI by the drug–drug comparison, study location, publication type, and risk of bias.

Figure S7. Forrest plots comparing the TEAEs in patients receiving Tegoprazan and PPI.

Table S1. PRISMA Checklist.

Table S2. Summary of included studies in the systematic review.

Acknowledgment

None.

Simadibrata, D. M. , Syam, A. F. , and Lee, Y. Y. (2022) A comparison of efficacy and safety of potassium‐competitive acid blocker and proton pump inhibitor in gastric acid‐related diseases: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 37: 2217–2228. 10.1111/jgh.16017.

Declaration of conflict of interest: Daniel Martin Simadibrata, Ari Fahrial Syam, and Yeong Yeh Lee have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions: DMS contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the manuscript; and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AFS contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the manuscript; and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YYL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial support: This study was funded by the Universitas Indonesia's Hibah PUTI RA Q1 2022 under contract number NKB‐746/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022.

References

- 1. Kusano M, Kuribayashi S, Kawamura O et al. A review of the management of gastric acid‐related diseases: focus on rabeprazole. Clin Med Gastroenterol. 2011; 4: CGast.S5133. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peura DA, Gudmundson J, Siepman N, Pilmer BL, Freston J. Proton pump inhibitors: effective first‐line treatment for management of dyspepsia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007; 52: 983–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salas M, Ward A, Caro J. Are proton pump inhibitors the first choice for acute treatment of gastric ulcers? A meta analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2002; 2: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mori H, Suzuki H. Role of acid suppression in acid‐related diseases: proton pump inhibitor and potassium‐competitive acid blocker. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019; 25: 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sachs G, Shin JM, Munson K, Scott DR. Gastric acid‐dependent diseases: a twentieth‐century revolution. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014; 59: 1358–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Veettil SK, Sadoyu S, Bald EM et al. Association of proton‐pump inhibitor use with adverse health outcomes: a systematic umbrella review of meta‐analyses of cohort studies and randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022; 88: 1551–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, SIF‐AIGO‐FIMMG Group , Italian Society of Pharmacology, the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists, and the Italian Federation of General Practitioners . Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid‐related diseases—a position paper addressing benefits and potential harms of acid suppression. BMC Med. 2016; 14: 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nehra AK, Alexander JA, Loftus CG, Nehra V. Proton pump inhibitors: review of emerging concerns. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018; 93: 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sugano K. Vonoprazan fumarate, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: safety and clinical evidence to date. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018; 11: 1756283X17745776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng Y, Liu J, Tan X et al. Direct comparison of the efficacy and safety of vonoprazan versus proton‐pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021; 66: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jung YS, Kim EH, Park CH. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: the efficacy of vonoprazan‐based triple therapy on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017; 46: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin, Zhou Y, Meng C‐X, Takagi T, Tian Y‐S. Vonoprazan vs proton pump inhibitors in treating post‐endoscopic submucosal dissection ulcers and preventing bleeding: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020; 99: e19357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simadibrata DM, Syam AF. The efficacy and safety of potassium competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vs. proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in gastric acid‐related disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PROSPERO. 2022: CRD42022307265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 63 (Updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2019; 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Products CfPM . Note for Guidance on Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials (CPMP/ICH/363/96). London: European Medicines Agency, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahrilas PJ, Dent J, Lauritsen K, Malfertheiner P, Denison H, Franzén S, Hasselgren G. A randomized, comparative study of three doses of AZD0865 and esomeprazole for healing of reflux esophagitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007; 5: 1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A et al. Randomised clinical trial: a dose‐ranging study of vonoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the treatment of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015; 42: 685–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Hori T et al. Randomised clinical trial: vonoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the healing of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016; 43: 240–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee KJ, Son BK, Kim GH et al. Randomised phase 3 trial: tegoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, vs. esomeprazole in patients with erosive oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019; 49: 864–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao Y, Zhang S, Dai N et al. Phase III, randomised, double‐blind, multicentre study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of vonoprazan compared with lansoprazole in Asian patients with erosive oesophagitis. Gut 2020; 69: 224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen S, Liu D, Chen H et al. The efficacy and safety of keverprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, in treating erosive oesophagitis: a phase III, randomised, double‐blind multicentre study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022; 55: 1524–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakurai K, Suda H, Fujie S et al. Short‐term symptomatic relief in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a comparative study of esomeprazole and vonoprazan. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019; 64: 815–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takeda . Comparison of vonoprazan to esomeprazole in participants with symptomatic GERD who responded partially to a high dose of proton pump inhibitor (PPI). 2018.

- 26. Murakami K, Sakurai Y, Shiino M, Funao N, Nishimura A, Asaka M. Vonoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, as a component of first‐line and second‐line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a phase III, randomised, double‐blind study. Gut 2016; 65: 1439–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maruyama M, Tanaka N, Kubota D et al. Vonoprazan‐based regimen is more useful than PPI‐based one as a first‐line Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017; 2017: 4385161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sue S, Ogushi M, Arima I et al. Vonoprazan‐ vs proton‐pump inhibitor‐based first‐line 7‐day triple therapy for clarithromycin‐susceptible Helicobacter pylori: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Helicobacter 2018; 23: e12456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sue S, Shibata W, Sasaki T, Kaneko H, Irie K, Kondo M, Maeda S. Randomized trial of vonoprazan‐based versus proton‐pump inhibitor‐based third‐line triple therapy with sitafloxacin for Helicobacter pylori . J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019; 34: 686–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hojo M, Asaoka D, Takeda T et al. Randomized controlled study on the effects of triple therapy including vonoprazan or rabeprazole for the second‐line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020; 13: 1756284820966247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bunchorntavakul C, Buranathawornsom A. Randomized clinical trial: 7‐day vonoprazan‐based versus 14‐day omeprazole‐based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori . J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021; 36: 3308–3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huh KY, Chung H, Kim YK et al. Evaluation of safety and pharmacokinetics of bismuth‐containing quadruple therapy with either vonoprazan or lansoprazole for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022; 88: 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hou X, Meng F, Wang J et al. Vonoprazan non‐inferior to lansoprazole in treating duodenal ulcer and eradicating Helicobacter pylori in Asian patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takeda . Comparison of TAK‐438 (vonoprazan) to lansoprazole in the treatment of gastric ulcer participants with or without Helicobacter Pylori infection. 2020.

- 35. Miwa H, Uedo N, Watari J et al. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy and safety of vonoprazan vs. lansoprazole in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers—results from two phase 3, non‐inferiority randomised controlled trials. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017; 45: 240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cho YK, Choi MG, Choi SC et al. Randomised clinical trial: tegoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, or lansoprazole in the treatment of gastric ulcer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020; 52: 789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miftahussurur M, Pratama Putra B, Yamaoka Y. The potential benefits of vonoprazan as Helicobacter pylori infection therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2020; 13: 276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Ofosu A, Gaduputi V. Potassium‐competitive acid blockers—are they the next generation of proton pump inhibitors? World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018; 9: 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ashida K, Iwakiri K, Hiramatsu N et al. Maintenance for healed erosive esophagitis: phase III comparison of vonoprazan with lansoprazole. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018; 24: 1550–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shinozaki S, Osawa H, Hayashi Y, Miura Y, Lefor AK, Yamamoto H. Long‐term vonoprazan therapy is effective for controlling symptomatic proton pump inhibitor‐resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease. Biomed Rep. 2021; 14: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Akiyama J, Hosaka H, Kuribayashi S et al. Efficacy of vonoprazan, a novel potassium‐competitive acid blocker, in patients with proton pump inhibitor‐refractory acid reflux. Digestion 2020; 101: 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scott DR, Sachs G, Marcus EA. The role of acid inhibition in Helicobacter pylori eradication. F1000Res 2016; 5: F1000 Faculty Rev‐747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kagami T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H et al. Potent acid inhibition by vonoprazan in comparison with esomeprazole, with reference to CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016; 43: 1048–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Search strategy.

Figure S2. Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool assessment for included studies.

Figure S3. Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies comparing the healing rates of erosive esophagitis in patients receiving Vonoprazan and PPI at (A) Week 2, (B) Week 4 and (C) Week 8.

Figure S4. (A) Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies comparing the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line treatment Vonoprazan and PPI. (B) Subgroup analysis for the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line Vonoprazan and PPI by the drug–drug comparison, study location, and risk of bias.

Figure S5. Forrest plots showing the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in patients receiving first‐line treatment of Vonoprazan and PPI. Analysis was restricted to studies which compared only triple therapies with the same treatment duration in both groups.

Figure S6. (A) Leave‐one‐out analysis for studies reporting the TEAEs in patients receiving PCAB and PPI. (B) Subgroup analysis for TEAEs in patients receiving PCAB and PPI by the drug–drug comparison, study location, publication type, and risk of bias.

Figure S7. Forrest plots comparing the TEAEs in patients receiving Tegoprazan and PPI.

Table S1. PRISMA Checklist.

Table S2. Summary of included studies in the systematic review.