Abstract

Background

Critical illness and the intensive care unit can be a terrifying experience to patients and relatives and they may experience the extreme life‐saving measures as dehumanizing. Humanizing intensive care is often described as holism or dignity, but these abstract concepts provide little bodily resonance to what a humanized attitude is in concrete situations.

Objective

To explore what contributes to patients' and relatives' experience of intensive care as humanized or dehumanized.

Design

Thematic synthesis.

Materials

Findings from 15 qualitative papers describing patients' and/or relatives' perceptions of humanizing or dehumanizing care.

Methods

A systematic literature search of PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus and EMBASE from 1 January 1999 to 20 August 2022 identified 16 qualitative, empirical papers describing patients' and relatives' experiences of humanizing or dehumanizing intensive care, which were assessed using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist, 15 papers were included and analysed using Thematic Synthesis and Ricoeur's model of the text.

Findings

Intensive care was humanized when patients felt connected with healthcare professionals, with themselves by experiencing safety and well‐being and with their loved ones. Intensive care was humanized to relatives when the patient was cared for as a unique person, when they were allowed to stay connected to the patient and when they felt cared for in the critical situation.

Conclusion

Patients and relatives experienced intensive care as humanized when healthcare professionals expressed genuine attention and supported them through their caring actions and when healthcare professionals supported patients' and relatives' opportunities to stay connected in the disrupted situation of critical illness. When healthcare professionals offered a connection to the patients and relatives, this helped them hold on and find meaning.

Patient or Public Contribution

No patient and public contribution.

Keywords: critical care, De, hermeneutics, humanizing, humanizing, intensive care, thematic synthesis

1. INTRODUCTION

Each day, humans find themselves admitted to intensive care units (ICU) because of severe, life‐threatening illness often resulting in mechanical ventilation and sedation. Critical care can be a terrifying experience where the patient feels isolated, lonely and at the mercy of strangers, and patients may experience pain and difficulty breathing, sleeping and thinking clearly (Engström et al., 2013; Haugdahl et al., 2015; Karlsson et al., 2012). Unfortunately, the lifesaving technological advances for survival have not been accompanied by similar advances in the more human aspects of critical care (Heras La Calle, Martin, & Nin, 2017). Consequently, the Spanish Proyecto HUCI has since 2014 sought to promote a more humanized approach to intensive care (Heras La Calle & Lallemand, 2014) culminating in a grand plan for humanizing intensive care in eight different areas including, but not limited to, open‐door policy, communication with patients and relatives, patient well‐being, participation of relatives in intensive care, end‐of‐life care and humanized infrastructure (proyectohuci.com). A scoping review (Kvande et al., 2021) sought to map how humanizing intensive care is described in the literature. There were many suggestions regarding how to make intensive care more humanized, ranging from the provision of specific interventions, adopting a certain attitude towards the patient, to the availability of resources and competencies (Kvande et al., 2021). The omnipresence of technology was a major threat to humanized care although it may be ameliorated by experienced healthcare professionals who understand how to focus on the patient despite their extensive use of technology (Kvande et al., 2021). Attempts to define humanizing intensive care have used theoretical concepts such as holism (Alonso‐Ovies & Heras la Calle, 2019; Milani et al., 2018; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019) and human dignity (Lopes & Brito, 2009; Mondadori et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2014). While the abstract nature of these concepts provides a cognitive understanding, they do not convey the mental and bodily resonance underlying a humanized attitude towards the patient; neither do they provide an immediate sense of how humanizing care is conducted or promoted. We assumed that knowledge of what contributes to patients' and relatives' experience of intensive care as humanized or dehumanized must be revealed from patients' and relatives' narratives of being at the mercy of the help of others, and therefore, it is important to clarify the meaning of humanism as experienced by patients and relatives in concrete situations and understand what it is and why it sometimes gets lost.

2. OBJECTIVE

To explore what contributes to patients' and relatives' experience of intensive care as humanized or dehumanized.

3. METHODS

3.1. Design

Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

3.2. Selection of studies for the review

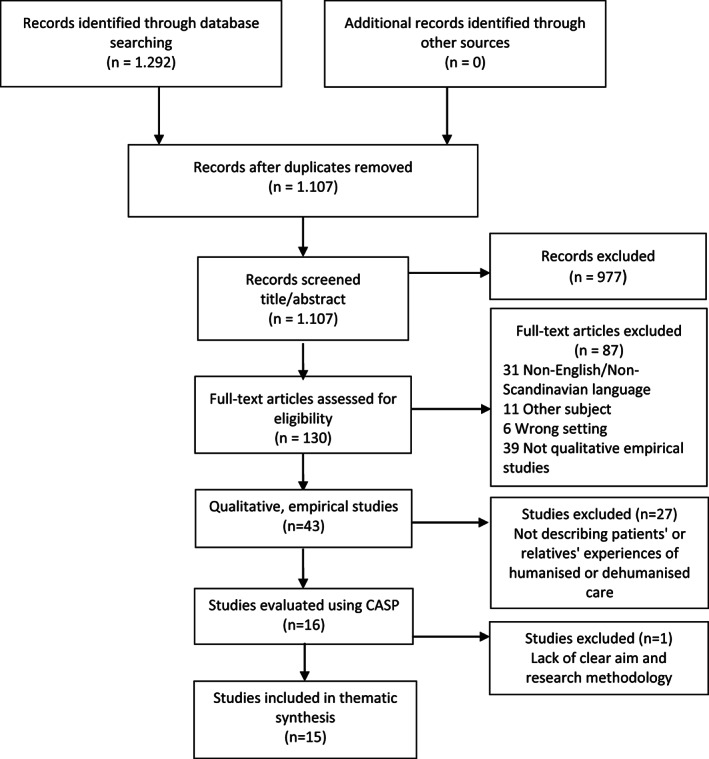

For an interpretive explanation, Thomas and Harden (2008) argued that purposive rather than exhaustive sampling and heterogeneity rather than homogeneity is important in thematic synthesis. Consequently, we did an extensive literature search covering the period between 1 January 1999 and 20 August 2022 for papers mentioning humanizing or dehumanizing in title or abstract. The literature searches of Embase, CINAHL, PubMed and Scopus databases identified 1.107 unique papers, which were screened by title and abstract and subsequently 130 papers were retrieved for full‐text screening. Papers describing non‐adult‐ICU settings, laboratory studies, COVID‐19 treatment and end‐of‐life care were excluded. Papers in other languages than English, Danish, Swedish or Norwegian were excluded. Qualitative, empirical studies (n = 43) were read thoroughly and papers not describing patients' or relatives' experiences of humanized or dehumanized care were excluded (n = 27). A total of 16 papers were independently assessed for quality (Table 1) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist (CASP‐QC) (casp‐uk.net) by two authors and discussed until consensus was reached before 15 papers were finally included in the study (Figure 1 and Table 2). All screening procedures were undertaken by two authors; in case of disagreement, a third author made the final decision.

TABLE 1.

Quality assessment of papers

| Authors (year of publication) | Title | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliex, S., Irurita, V. F. (2004) | Caring in a technological environment: how is this possible? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Basile, M. J., Rubin, E., Wilson, M. E., Polo, J., Jacome, S. N., Brown, S. M., Heras La Calle, G., Montori, V. M., Hajazadeh N. (2021) | Humanizing the ICU patient: A Qualitative exploration of behaviors experienced by patients, caregivers, and ICU staff. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | Included |

| Cheraghi, M. A., Esmaeili, M., Salsali, M. (2017) | Seeking Humanizing Care in Patient‐Centered Care Process. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Connelly, C., Jarvie, L., Daniel, M., Monachello, E., Quasim, T., Dunn, L., McPeake, J. (2019) | Understanding what matters to patients in critical care: An exploratory evaluation. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Corner, E. J., Murray, E. J., Brett, S. J. (2019) | Qualitative, grounded theory exploration of patients' experience of early mobilization, rehabilitation and recovery after critical illness. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Fabiane, U., Correa, A. K. (2007) | Relatives' experience of intensive care: the other side of hospitalization. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Flinterud, S. I., Moi, A. L., Gjengedal, E., Ellingsen, S. (2022) | Understanding the Course of Critical Illness Through a Lifeworld Approach. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Included |

| Garrouste‐Orgeas, M., Périer, A., Mouricou, P., Grégoire, C., Bruel, C., Brochon, S., Philippart, F., Max, A., Misset, B. (2014) | Writing in and reading ICU diaries: Qualitative study of families' experience in the ICU. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Giuliano, K. K., Bloniasz, E., Bell, J. (1999) | Implementation of a pet visitation program in critical care. | − | ? | ? | − | − | − | ? | − | − | Not included |

| Hoad, N., Swinton, M., Takaoka, A., Tam, B., Shears, M., Waugh, L., Toledo, F., Clarke, F. J., Duan, E. H., Soth, M., Cook, D. J. (2019) | Fostering humanism: a mixed methods evaluation of the Footprints Project in critical care. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Included |

| Milani, P., Lanferdini, I. Z., Alves, V.B. (2018) | Caregivers' Perception When Facing the Care Humanization in The Immediate Postoperative Period From a Cardiac Surgery Procedure. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | Included |

| Pereira, M. M. M., Germano, R. M., & Câmara, A. G. (2014) | Aspects of nursing care in the intensive care unit. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Rodriguez‐Almagro, J., Quero Palomino, M. A., Aznar Sepulveda, E., Fernandez‐Espartero Rodriguez‐Barbero, M. D. M., Ortiz Fernandez, F., Soto Barrera, V., Hernandez‐Martinez, A. (2019) | Experience of care through patients, family members and health professionals in an intensive care unit: a qualitative descriptive study. | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | Included |

| Stayt, L. C., Seers, K., Tutton, E. (2015) | Patients' experiences of technology and care in adult intensive care. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

| Tripahty, S., Acharya, S. P., Sahoo, A. K., Mitra, J. K., Goel, K., Ahmad, S. R., Hansdah, U. (2020) | Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries and the experiences of patients' families: a grounded theory approach in a lower middle‐income country (LMIC). | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Included |

| Urizzi, F., Carvalho, L. M., Zampa, H. B., Ferreira, G. L., Grion, C. M., Cardoso, L. T., (2008) | The experience of family members of patients staying in intensive care units. | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | Included |

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram

TABLE 2.

Overview of included papers

| Authors | Year | Country | Population | Aim/objective | Method | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliex, S., Irurita, V. F. | 2004 | Australia | 13 patients (and 21 nurses) | To identify the problem from the nurses' perspective in interacting with patients within a technological context and to discover how nurses dealt with this problem | Grounded theory, interviews, participant observations | Addressing the patient as an individual caring for human needs as being talked to and with, offering attention, making comfortable, maintaining presence at the bedside, giving attention, making genuine inquiries of personal requests. Reducing the impact of technology by understating it and using humour. Using touch to demonstrate empathy and compassion (soft‐hand) |

| Basile, M. J., Rubin, E., Wilson, M. E., Polo, J., Jacome, S. N., Brown, S. M., Heras La Calle, G., Montori, V. M., Hajazadeh N. | 2021 | USA | 28 patients, 12 relatives (and 31 health professionals) | To understand how patients and family members experience dehumanizing or humanizing treatment when in the ICU | Qualitative analysis, Remote focus groups and open‐ended surveys on social media boards | Dehumanization occurred during “communication” exchanges when ICU team members talked “over” patients, made distressing remarks when patients were present, or failed to inform patients about ICU‐related care. “Outcomes” of dehumanization were associated with patient loss of trust in the medical team, loss of motivation to participate in ICU recovery, feeling of distress, guilt, depression, and anxiety. Humanizing behaviours were associated with improved recovery, well‐being, and trust |

| Cheraghi, M. A., Esmaeili, M., Salsali, M. | 2017 | Iran | 10 patients (16 nurses and 1 physician) | To explain the process and means of providing Patient‐Centred Care | Grounded theory, semi‐structured interviews | Patient‐centred Care required an all‐embracing understanding of the patient and showing respect for their values, needs and preferences |

| Connelly, C., Jarvie, L., Daniel, M., Monachello, E., Quasim, T., Dunn, L., McPeake, J. | 2019 | UK | 196 Patients | To understand what mattered to patients on a daily basis within the critical care environment and understand personal goals and what patients needed to improve their experience | Framework Method, 592 statements from patients | Four themes: Medical outcomes and information, The critical care environment, Personal care, Family and caregivers |

| Corner, E. J., Murray, E. J., Brett, S. J. | 2019 | UK | 15 patients | To explore the patient experience of recovery from critical illness, with emphasis on their experience of rehabilitation, and to develop a theoretical model grounded in these data | Grounded theory, semi‐structured interviews | The central phenomenon grounded in these data was recalibration of the self. To communicate honestly and to maintain patient's hope, to be recognized as a person (‘humanized’ care), de‐humanized care included loss of agency |

| Fabiane, U., Correa, A. K. | 2007 | Brazil | 17 relatives | To understand the experiences of ICU patients' relatives, to contribute to health care humanization in this context | Phenomenology, interviews | Relatives described it as a difficult, painful, speechless experience; experiencing and recognizing somebody's life: approaching the patient's suffering; break‐up of the family's daily routine; fear of having a family member die; ICU: a fearsome scene, but necessary; concern with family care |

| Flinterud, S. I., Moi, A. L., Gjengedal, E., Ellingsen, S. | 2022 | Norway | 10 patients | To explore and describe what intensive care patients experience as limiting and strengthening throughout their illness trajectories to reveal their needs for support and follow‐up | Phenomenology, interview study | For patients, it was important to feel safe through a caring presence, being seen and met as a unique persona, and being supported to restore capacity |

| Garrouste‐Orgeas, M., Périer, A., Mouricou, P., Grégoire, C., Bruel, C., Brochon, S., Philippart, F., Max, A., Misset, B. | 2014 | France | 32 relatives | To investigate the families' experience with reading and writing in patient ICU diaries kept by both the family and the staff | Grounded theory, semi‐structured in‐depth interviews | Family members felt the diaries humanized the medical staff and patient. The diary was a tool of humanization of the ICU. The diaries served as a powerful tool to deliver holistic patient‐ and family‐centred care despite the potentially dehumanizing ICU environment. The staff viewed the patient as a living human being |

| 2019 | Canada | 5 patients, 13 relatives (and 35 health professionals) | To assess the uptake, sustainability and influence of the Footprints Project | Mixed‐methods design, 3 audits, semi‐structured interviews | The Footprints Project facilitated holistic, patient‐centred care by setting the stage for patient and family experience, motivating the patient and humanizing the patient for clinicians. Footprints helped clinicians initiate more personal conversations, foster deeper connections and guide treatment | |

| Milani, P., Lanferdini, I. Z., Alves, V.B. (2018) | 2018 | Brazil | 5 relatives | To analyse the caregivers' perception of patients submitted to cardiac surgery when facing the care humanization in an ICU | Content analysis, semi‐structured interviews | Providing quality care to patients and caregivers, listening and appreciating their feelings, are essential to providing humanized care |

| Pereira, M. M. M., Germano, R. M., & Câmara, A. G. | 2014 | Brazil | 10 patients | The study aims to understand the feelings of ICU patients | Qualitative interviews with 10 patients | Two major thematic groups emerged from their content: feelings of patients during shift change at the hospital beds, and relevant aspects of the ICU stay |

| Rodriguez‐Almagro, J., Quero Palomino, M. A., Aznar Sepulveda, E., Fernandez‐Espartero Rodriguez‐Barbero, M. D. M., Ortiz Fernandez, F., Soto Barrera, V., Hernandez‐Martinez, A. | 2019 | Spain | 9 patients, 9 relatives (and 9 nurses) | To explore the perceptions about the experiences of patients in the ICU, their family members and nurses who attend them | Descriptive phenomenological design, interviews | Humanizing is talking, touching as the patient is a person. Patients and relatives consider technical attention as dehumanizing. Dehumanizing as long waiting hours for relatives, and separation that make the patient be alone |

| Stayt, L. C., Seers, K., Tutton, E. | 2015 | UK | 19 patients | To investigate patients' experiences of technology in an adult intensive care unit | Heideggerian phenomenology, Interview study | Patients experienced technology and care as a series of paradoxical relationships: alienating yet reassuring, uncomfortable yet comforting, impersonal yet personal. By maintaining a close and supportive presence and providing personal comfort and care nurses may minimize the invasive and isolating potential of technology |

| Tripahty, S., Acharya, S. P., Sahoo, A. K., Mitra, J. K., Goel, K., Ahmad, S. R., Hansdah, U. | 2020 | India | 29 relatives | To explore how families of ICU patients experienced ICU diaries | Grounded theory, interview study | Relatives experienced the diary as a communication enabler, a spiritual support that improved knowledge and helped them connect with the health care workers |

| Urizzi, F., Carvalho, L. M., Zampa, H. B., Ferreira, G. L., Grion, C. M., Cardoso, L. T., (2008) | 2008 | Brazil | 27 relatives | Understand experience of family members during the patients stay in the ICU | Interviews, phenomenology | Thematic categories: difficult experience, painful, without words; put yourself in the place and perceive the other: approximation to the suffering of the patient; split in the relationship with family everyday life; fear of the family member death; concern with care of the family member |

3.3. Extraction of data

To describe the included studies, the following were extracted: authors, year of publication, journal name, title, country of origin, research design/methodology, objective, participants and main findings. For the synthesis, we extracted the entire section labelled ‘results’ or ‘findings’ as suggested by Thomas and Harden (2008) and considered all findings related to ICU patients and their relatives. We did not extract tables or figures.

3.4. Data analysis

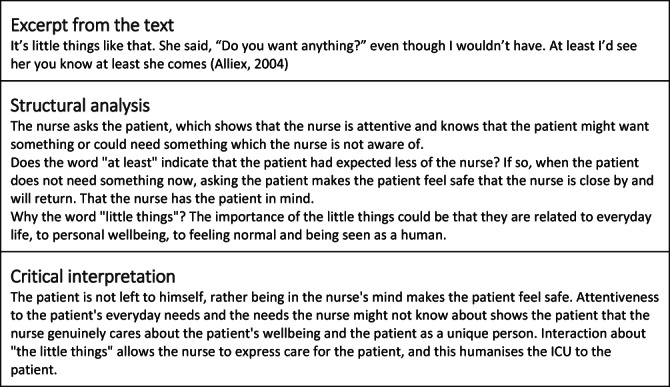

The analytic stages of thematic synthesis, as described by Thomas and Harden (2008), includes the following stages: free line‐by‐line coding, organizing free codes into descriptive themes and generating analytical themes with the aim of going beyond the findings of initial studies in a cyclical process of examining the descriptive themes in light of the research question. Thomas and Harden (2008) describe the process of interpretation as dependent on the insightfulness and judgement of the researcher but difficult to describe. Moreover, Thomas and Harden (2008) argued that the research question may restrain the researcher's openness towards the data and suggested setting aside review questions and starting with the study findings themselves. Extending this line of thought, we drew on Ricoeur's model of the text (Ricoeur, 1991) to further support and strengthen the analysis through a hermeneutic phenomenological reading of the original results and findings extracted for this review. Furthermore, Ricoeur's model of the text (1991) allowed us to clearly explicate what Thomas and Harden (2008) described as putting review questions aside and beginning with the study findings, a process that was not clearly described by Thomas and Harden (2008). Ricoeur (1991) describes the process from an initial naïve understanding to a critical interpretation. First, all extracted sections were read thoroughly for an initial overall understanding of what they were about (Ricoeur, 1991). In the following structural analysis, which is an explanatory procedure that focuses on the texts themselves freed from their origin or context, the extracted sections labelled ‘findings’ or ‘results’ were read line by line, and parts not smaller than sentences were described in terms of what they said and what they were about (Ricoeur, 1991). Then internal relations were explored within each extracted section and across sections (Ricoeur, 1991). In this sense, the texts were explained (Ricoeur, 1991) or, as Thomas and Harden (2008) stated, interpreted close to the original texts. However, according to Thomas and Harden (2008), the aim of a thematic synthesis is to go beyond the findings of the original studies in light of a new research question. With Ricoeur (1991), we can explain this move in greater detail. According to Ricoeur (1991), the critical interpretation does merely convey what the original studies say but what they open up for. This implied being receptive to what the texts said about the world or, in this case, about the research question and thus choosing the most probable interpretation among competing ones (Ricoeur, 1991). This involved moving back and forth between data and interpretations to ensure rigour and trustworthiness of the analysis. All authors participated in the analysis and continually discussed and reflected on the findings. For an example of the analysis, see Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Example from the analysis

3.5. Ethics

All included studies involving human subjects had undergone ethical review.

4. FINDINGS

Humanized intensive care was experienced by patients when they felt connected with healthcare professionals, with themselves by experiencing safety and well‐being and with their loved ones. Relatives experienced intensive care as humanized when the patient was cared for as a unique person, when they were allowed to stay connected to the patient and when they themselves were cared for in the critical situation (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Overview of themes

| Patients | Relatives |

|---|---|

|

|

4.1. Patients felt recognized as human beings when they experienced connectedness with healthcare professionals

Patients are highly appreciated when they felt recognized as human beings by healthcare professionals. Being looked in the eyes, seeing a smiling face or being touched in a kind way were powerful ways for the patient to be comforted in the critical situation (Corner et al., 2019; Flinterud et al., 2022; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019). Comforting the patient implied acknowledging the patient as a fellow human being of intrinsic value and thus humanized intensive care:

“A nurse…squeezing my hand, transmitting trust and well‐being to me, and understanding me straight away…I was so grateful for this gesture!” (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019)

When patients felt cared for in a personal way with meticulous attention to their needs and personal preferences, this promoted well‐being and thereby trust among patients:

“It's little things like that. She said, ‘Do you want anything?’ even though I wouldn't have. At least I'd see her you know at least she comes.” (Alliex & Irurita, 2004)

Patients referred to personal care and simply healthcare professionals looking into their room as ‘little things’, which suggests that even small gestures such as showing the patient deliberate and genuine attention may make a huge difference in terms of humanizing intensive care. Besides attention to little details that promoted patient comfort, staying beside the patient in the most critical situation and doing more than the patient thought could be expected was also a powerful way of connecting with the patient in a way that humanizes intensive care:

“And I had a couple of nurses by my side for the most dramatic period, and you get to know them. And I felt they did so much more for me than they had to.” (Flinterud et al., 2022)

Contrarily, a display of disinterest or lack of time to pay attention to the patient as a human being could trigger feelings of dehumanization and isolation even when receiving care:

“I felt cared for but it did seem impersonal at times…well they did examine me but I felt they were more interested in what the machines were telling them… I felt just separated from it.”

(Stayt et al., 2015)

The paradox of feeling cared for, although in an impersonal way, suggests that humanizing care truly depended on feeling connected to healthcare professionals.

Beyond the acute situation, getting to know the patient and learning about the patient's ways and preferences signalled to the patients that they were much more than merely patients but also persons in their own right with histories, families, interests and values:

“To me, it felt like, when they looked at it, they were looking at me ‐ no more as a patient…they were looking at me as a family man; a dad, a husband, an uncle, a brother… I wasn't just ‘that patient in Room 4.” (Hoad et al., 2019)

Being acknowledged as a person helped patients not only endure the time in the critical care unit but also alleviated feelings of insecurity, loneliness and despair (Corner et al., 2019; Flinterud et al., 2022; Hoad et al., 2019).

4.2. Experiencing safety and well‐being helps patients feel connected with themselves and the situation

The ICU was perceived as an unfamiliar and stressful place for most patients with sensory impressions that seemed strange or frightening (Connelly et al., 2019; Pereira et al., 2014). Patients in the intensive care unit trusted and depended on lifesaving technology to save them but at times merely felt like an extension of the technology. This feeling was exacerbated when healthcare professionals directed their attention to the technology and less so to the patient (Stayt et al., 2015). Even if there were healthcare professionals around the patient at all times, the patient could feel isolated in the inescapable situation of being critically ill:

“The […] feeling I remember better about my stay was LONELINESS, feeling tremendously lonely. I had no idea that you could feel so much loneliness when surrounded by people.” (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019)

Knowing and understanding what was happening and why was important for patients. Receiving information could help patients manage and endure their critical situation; however, information should be tailored to the patient's individual needs. Not receiving information could cause patients to feel unsafe and could violate the trust between them and health professionals:

“I'd like my doctor to adequately inform me; however, nobody provides me with information. For instance, since yesterday I have felt that I'm going to undergo a surgery; still, one doctor says that I don't need surgery while the other one believes that I clearly need it. This uncertainty agitates me.” (Cheraghi et al., 2017)

Being unable to help themselves and escape the critical care situation, patients depended on healthcare professionals' readiness to attend to all their needs and not only their imminent medical needs. Lack of nursing care when the patient needed cleaning or help with personal care activities increased their feeling of helplessness and dehumanization (Basile et al., 2021; Milani et al., 2018) whereas meticulous attention to patients' personal care, such as body and hair washing, hair brushing, mouth care, tooth brushing and comfort, was important, as it helped patients feel presentable, promoted well‐being and made them feel more like themselves and thus as human beings (Alliex & Irurita, 2004; Connelly et al., 2019):

“[Summing up, patients] were very grateful to nurses when their likes were considered and nurses took the time to do the little things for them that made them comfortable, for example, fluffing pillows and keeping them comfortable.” (Alliex & Irurita, 2004)

4.3. Feeling connected with significant persons and life outside the ICU

Spending time with relatives was tremendously important to patients. Relatives' presence comforted patients and allowed them to relax and feel safe in an unfamiliar and frightening situation surrounded by strangers (Connelly et al., 2019). Feeling close to relatives meant being able to share feelings of love and belonging together and being reminded about life outside the ICU. Sometimes patients also needed to comfort their relatives, who they knew were in distress:

“My boy enters, he's nervous. I stretch my arms out to him and he starts crying over me. We both cry, we kiss one another, we give one another lots of paper kisses through the masks we wear, all the kisses we'd saved up for weeks.” (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019)

In addition to feeling connected to relatives, patients also wanted to feel part of their community and life outside the ICU. Being able to connect with one's chaplain or spiritual community was a source of great comfort to the patient and reminded them of life outside the ICU:

“Patients requested support from their own community, as well support available within the hospital setting.” (Connelly et al., 2019).

Healthcare professionals could support patients yearning for a normal life by providing them with entertainment such as a radio program the patient usually follows or turning the bed and letting the patient enjoy fireworks in a dark evening sky:

“[Patients] wanted to listen to the football radio show that he normally listened to each evening at home.” (Connelly et al., 2019).

Such experiences reminded the patient of the world and their life outside the ICU and emphasized their humanity and having family, friends, interests and desires and as such helped humanize the intensive care unit.

4.4. Seeing the patient safe and cared for as a unique human being comforted relatives

Relatives experienced the intensive care unit as a terrifying place with all its high‐tech equipment and invasive procedures. However, in the acute situation, the staff's expertise and dedication to saving the patient's life indicated the patient's absolute value of being a human being to the relatives. Relatives found comfort and hope in seeing how healthcare professionals with care and diligence worked to help the patient (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Pereira et al., 2014). This underscored the patient's value as a unique human being even if the severe situation made relatives willing to accept extremely advanced therapy for the sake of saving the patient's life, which might otherwise have been unacceptable:

“(…) but after he came here, I have hope, you know, because I know that here is where you recover, right … so it's for the best, right ….” (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007)

When healthcare professionals took good care of the patient, for example, by paying attention to the patient's needs and wishes (Cheraghi et al., 2017; Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Hoad et al., 2019) including their spiritual needs (Milani et al., 2018), this showed the relatives that the patient was an important and unique human being. When staff actively sought to know the patient as a person, this contributed to forming relationships with both patients and relatives. A diary written by staff and relatives could serve as a vehicle for communicating the healthcare professionals' care for the patient (Tripathy et al., 2020). A strong relationship promoted trust in healthcare professionals and thereby humanized intensive care to the relatives (Hoad et al., 2019):

“I think it helped improve and just strengthen the bond…and that trust. Knowing that…my family member was being cared for—not only on the clinical side but as a human being—that genuine care of humanity…I think it strengthened the relationship and gave us comfort as well.” (Hoad et al., 2019)

Meanwhile, when health professionals were ignorant of the patients' distress and discomfort or at least did not make their attention to the patients' distress visible to the relatives, this contributed to intensive care being perceived as dehumanizing (Basile et al., 2021). This means that not paying attention to the little details that may provide comfort for the patient in an otherwise stressful situation indirectly hurt their relatives. This included indifference, inattentiveness, disregard or disinterest in the patient's experiences and condition:

“So I saw that the nurse, that little apparatus that they put in the nose with no care, it's not put in correctly, it's like this, there's a mark there, like it is pressing my mother's face, so I, I felt like she didn't have love or care for the, the … a patient and not like … the thing itself.”(Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007)

4.5. Experiencing connectedness with the patient and maintaining bonds

Relatives wanted to be close to the patient in the intensive care unit, and they believed that their presence and support for the patient was essential to the patient's recovery (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007). The high‐tech environment and invasive treatments could, however, make it difficult for relatives to recognize the patient as an alive, living and breathing person that they were related to (Garrouste‐Orgeas et al., 2014). In such situations, relatives appreciated when health professionals encouraged them to reach out to the patient (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019):

“[nurses told relatives to] Talk to him, touch him in the same way you'd want if it was done to you.” (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019)

Separation of patients and relatives was distressing to the latter, who felt the bonds between them being severed (Basile et al., 2021;Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019). Therefore, helping relatives see the patient and experience closeness with the patient was important to humanize intensive care to the relative, as it restored the bond between them. Using intensive care unit diaries was another way health professionals could help relatives look beyond technology and see the person they love, which touched relatives deeply, provided hope and supported them emotionally:

“When I read what the staff members wrote, I really feel they're taking care of a person who is alive.” (Garrouste‐Orgeas et al., 2014)

Helping relatives reach out to the patient and connect with the patient humanized intensive care to relatives, but restrictive visitation policies could keep relatives from being with and supporting the patient (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019; Urizzi et al., 2008). When healthcare systems or healthcare staff failed to acknowledge the importance of relatives' need to be close and feel connected to the patient in a critical situation, this could cause relatives to experience intensive care as dehumanizing (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019; Urizzi et al., 2008):

“One wishes to be near and one can't yeah! Because visiting hours have to be controlled. One even understands that but, one would like to stay near, all the time if one could.” (Urizzi et al., 2008)

4.6. Feeling cared for helped relatives endure the critical situation in the ICU

Relatives missed the patient in their everyday life when the patient is admitted to the ICU and was constantly reminded of what a life without the patient would be like if they succumbed to critical illness. When in the ICU, they not only witnessed the patient's suffering; they also imagined themselves in the place of the patient and thus felt how the patient was suffering. This elicited extremely strong feelings that could be difficult to express in words, and not being able to express these feelings could cause relatives to feel alone:

“I crouch in a corner with my feelings; it's just me and loneliness.” (Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019)

Being met with kindness by all staff members, from receptionists to healthcare professionals and other groups working in the ICU, was critical to relatives being able to endure their difficult situation (Urizzi et al., 2008). Not having to wait without information but being welcomed as an important member of the team helped relatives feel that they belonged and humanized intensive care to them (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019).

Relatives also needed to understand the patient's condition to endure the difficult and emotional situation of the patient's critical illness, and when information was given with recognition of the relative's distressful situation, it alleviated some of the relatives' suffering:

“It's not the doctor speaking, it's the human being, who gives information – and obviously it's medical – but it's a human being speaking to another human being [relative].” (Garrouste‐Orgeas et al., 2014)

Healthcare professionals' perspectives might be limited by the technical‐scientific approach of the ICU (Fabiane & Corrêa, 2007), and standardization and adherence to procedures may dehumanize intensive care to relatives if their individual perspectives are not considered. However, if healthcare professionals can transcend the technical‐scientific perspective in conversations with relatives, they may be able to grasp the situation of the relatives and understand what their needs are.

5. DISCUSSION

This study showed that patients' and relatives' experiences of intensive care as humanized were closely linked to their feeling of being connected with each other, and with healthcare professionals, and receiving care and attention to all their needs.

The helplessness and extreme vulnerability of patients and relatives (Karlsson et al., 2012; Rodriguez‐Almagro et al., 2019; Stayt et al., 2015) are the antecedent to the need to address humanization. Furthermore, the high‐tech environment, described by Rodriguez‐Almagro et al. (2019) as a parallel universe, provides fertile ground for dehumanization. This dehumanizing nature of the ICU is supported by a conceptual framework developed by Galvin and Todres (2013), who identified eight forms of humanization–dehumanization: insiderness/objectification, agency/passivity, uniqueness/homogenization, togetherness/isolation, sense‐making/loss of meaning, personal journey/loss of personal journey, sense of place/dislocation and embodiment/reductionist body. Each pair are opposites on a continuum between humanization and dehumanization. Galvin and Todres (2013) underscored that these dimensions of humanization and dehumanization are not absolutes; rather, they depend on the context and complexity of the situation. All these forms of dehumanization apply to the ICU patient and highlight the fundamental threat the ICU poses to the preservation of patients' humanity and why a strong focus on humanizing the ICU is necessary. However, Galvin and Todres (2013) hesitated to overemphasize the negative effects of dehumanizing practices, as there are times when these are appropriate for effective care. In accordance, we found that if dehumanization in the form of lifesaving treatment was indeed necessary, the relatives accepted this treatment, as it served the higher purpose of saving the patient's life. This human tendency to seek meaning in the direst of situations is supported by the Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl (2004), who claimed that ‘human life under any circumstances, never ceases to have a meaning, and that this infinite meaning of life includes suffering and dying, privation and death’. Moreover, Frankl (2004) argued that as long as life has meaning, humans can endure almost any circumstance. Consequently, humanizing intensive care may not only be about preventing dehumanization intrinsic to the ICU but perhaps more about supporting patients and relatives to find meaning in the critical illness experience.

Humanizing intensive care has been previously described as a certain attitude towards patients and relatives (Heras La Calle, Ovies, & Tello, 2017) and the expression of this attitude in actions and interactions with patients and relatives (Kvande et al., 2021). When describing actions that humanized care, patients used the term ‘little things’ (Alliex & Irurita, 2004). Little things were ordinary and well‐known actions such as fluffing pillows or going to the patient's room to check if the patient needed anything. On the surface, these actions aimed at making the patient comfortable and safe. However, on a more existential level, the ‘little things’ conveyed healthcare professionals' attention to the patients' needs and served as a vehicle for making humanizing care visible to patients and relatives. We have resisted the temptation to list humanizing interventions or instructions for professionals' actions based on patients' and relatives' concrete examples of what they experience contribute to their experience of intensive care as humanized, as it was clear that actions and communication alone will not ensure humanized intensive care. This is supported by Ellis‐Hill et al. (2021) and Galvin and Todres (2013) who points to how a humanized approach draws upon an embodied understanding of intertwined and mutually arising reality rather than a cognitive understanding relying on an objectifying biomedical worldview. As such, it is the humanizing attitude expressed from the heart in the conduct, gaze and touch of the healthcare professionals that makes an impression on patients and relatives. This observation is consistent with that of Martinsen (2006), who explained that seeing with the heart's eye, with a participative and attentive approach, makes the other emerge as significant. The patients' and relatives' appeals and needs touch and move receptive healthcare professionals, and according to Martinsen's philosophy (2006), healthcare professionals are compelled to respond by acting in a practical way. This means that there is a fundamental connection between attitude, the eye for the other person's needs, and caring for them. Without caring, patients and relatives will not experience the ICU as humanized.

The German philosopher Heidegger problematized the tendency to focus solely on the body when tending to the sick and thus reduce a human to merely being a body, and not a trinity of body, mind and spirit (Aho, 2018). In addition, Tembo (2017) showed how critical illness disrupts the entire existence of both patient and their relatives, replacing the existence they take for granted with helplessness and suffering when subjected to the extreme lifesaving methods of the ICU. The close connection between the patient's life and the relatives' lives and the rupture that critical illness represents were evident in the relatives' strong feelings, where they both felt deeply for themselves and for the patient, rendering their suffering greater and more intense. However, this suffering could be ameliorated to some extent when patients and relatives are allowed to experience closeness and connectedness with each other. This is supported by Whiffin and Ellis‐Hill (2021) who found that health care professionals played an important role in helping patients and relatives find a way to reconnect through narratives to identify a liveable future. Moreover, we found that it was humanizing when healthcare professionals offered to connect with patients and relatives in the ICU. Underlying this is an understanding of what it means to be human and to feel like a human being. This is consistent with Martinsen (2006, 2010) who argued that human beings are interconnected and dependent on one another, inspired by Løgstrup's views of human life as one in interdependence (Martinsen, 2010). Thus, the relationship to the lived life and the dignity that emerges from being treated as a human is reinforced by feeling connected to the situation, to healthcare professionals and to loved ones. The notion of connectedness as a centrepiece of humanizing care can be further elaborated by the study of Rykkje et al. (2015). For the intensive care patient, the healthcare professional offers them an opportunity to connect. In this connectedness, the healthcare professional may express care for the patient as a person in a specific situation and convey a heartfelt desire to help. In addition to being connected to the healthcare professional, the offer of a connection to the patient provides them with the opportunity to connect with themselves, others and to something larger than themselves (Rykkje et al., 2015). If the healthcare professional is incapable of this, actions are reduced to tasks without spirit and heart (Rykkje et al., 2015). Care that does not offer connectedness leaves the patient and relatives with nothing to hold on to and nothing that can prevent the patient and relative from slipping into despair (Rykkje et al., 2015).

5.1. Strengths and limitations

The findings of this study were strengthened by the systematic approach to thematic synthesis outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008) and deepened by the incorporation of Ricoeur's model of the text (1991), which allowed us to engage with the analysis in a thorough yet transparent way. The probability of our interpretation has been verified by relating our findings to existing literature. Limitations of the study include the relatively small number of qualitative papers that specifically addressed patients' and relatives' perceptions of humanizing intensive care. Nevertheless, the findings were consistent across papers from different parts of the world, which suggest that the findings are universally human and thus applicable to intensive care units in different cultures and regions of the world.

6. CONCLUSION

Patients and relatives experienced intensive care as humanized when healthcare professionals expressed genuine attention to their every need and supported them through their caring actions. Intensive care was experienced as humanized when healthcare professionals supported patients' and relatives' opportunities to stay connected in the disruptive situation of critical illness. Moreover, intensive care was experienced as humanized when healthcare professionals offered a connection to patients and relatives, thereby providing them with something to hold on to and helping them find meaning.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anne Højager Nielsen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and editing. Monica Evelyn Kvande: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review and editing. Sanne Angel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review and editing. All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE*): (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; and (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors. Anne Højager Nielsen was founded by the NOVO Nordisk Foundation for another project NNF19OC0058277.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15477.

Nielsen, A. H. , Kvande, M. E. , & Angel, S. (2023). Humanizing and dehumanizing intensive care: Thematic synthesis (HumanIC). Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79, 385–401. 10.1111/jan.15477

Contributor Information

Anne Højager Nielsen, Email: ahn@clin.au.dk, @AnneHoejager.

Monica Evelyn Kvande, @MonicaKvande.

Sanne Angel, @Angel123_Sanne.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

For this is review all included papers were accessible to the public.

REFERENCES

- Aho, K. (Ed.). (2018). Existential medicine: Essays on health and illness. Rowman & Littlefield International. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliex, S. , & Irurita, V. F. (2004). Caring in a technological environment: How is this possible? Contemporary Nurse, 17(1–2), 32–43. 10.5172/conu.17.1-2.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso‐Ovies, A. , & Heras la Calle, G. (2019). Humanizing care reduces mortality in critically ill patients. Medicina Intensiva, 44(2), 122–124. 10.1016/j.medin.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile, M. J. , Rubin, E. , Wilson, M. E. , Polo, J. , Jacome, S. N. , Brown, S. M. , Heras La Calle, G. , Montori, V. M. , & Hajizadeh, N. (2021). Humanizing the ICU patient: A qualitative exploration of behaviors experienced by patients, caregivers, and ICU staff. Crit Care Explor, 3(6), e0463. 10.1097/cce.0000000000000463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASP Instrument. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists

- Cheraghi, M. A. , Esmaeili, M. , & Salsali, M. (2017). Seeking humanizing care in patient‐centered care process: A grounded theory study. Holistic Nursing Practice, 31(6), 359–368. 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, C. , Jarvie, L. , Daniel, M. , Monachello, E. , Quasim, T. , Dunn, L. , & McPeake, J. (2019). Understanding what matters to patients in critical care: An exploratory evaluation. Nursing in Critical Care, 25, 214–220. 10.1111/nicc.12461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corner, E. J. , Murray, E. J. , & Brett, S. J. (2019). Qualitative, grounded theory exploration of patients' experience of early mobilisation, rehabilitation and recovery after critical illness. BMJ Open, 9(2), e026348. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis‐Hill, C. , Pound, C. , & Galvin, K. (2021). Making the invisible more visible: Reflections on practice‐based humanising lifeworld‐led research – Existential opportunities for supporting dignity, compassion and wellbeing [article]. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 10.1111/scs.13013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström, Å. , Nyström, N. , Sundelin, G. , & Rattray, J. (2013). People's experiences of being mechanically ventilated in an ICU: A qualitative study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: The official journal of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses, 29(2), 88–95. 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiane, U. , & Corrêa, A. K. (2007). Relatives' experience of intensive care: The other side of hospitalization. Revista Latino‐Americana de Enfermagem, 15(4), 598–604. 10.1590/s0104-11692007000400012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinterud, S. I. , Moi, A. L. , Gjengedal, E. , & Ellingsen, S. (2022). Understanding the course of critical illness through a lifeworld approach. Qualitative Health Research, 32(3), 531–542. 10.1177/10497323211062567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V. E. (2004). Man's search for meaning: The classic tribute to hope from the holocaust (New edition ed.). Rider. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, K. , & Todres, L. (2013). Caring and well‐being: A lifeworld approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garrouste‐Orgeas, M. , Périer, A. , Mouricou, P. , Grégoire, C. , Bruel, C. , Brochon, S. , Philippart, F. , Max, A. , & Misset, B. (2014). Writing in and reading ICU diaries: Qualitative study of families' experience in the ICU. PLoS One, 9(10), 1–10. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2‐s2.0‐84908032399&partnerID=40&md5=132de5396b4fdd66a2566887a35483c3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugdahl, H. S. , Storli, S. L. , Meland, B. , Dybwik, K. , Romild, U. , & Klepstad, P. (2015). Underestimation of patient breathlessness by nurses and physicians during a spontaneous breathing trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 192(12), 1440–1448. 10.1164/rccm.201503-0419OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heras La Calle, G. , & Lallemand, C. Z. (2014). HUCI is written with H as in HUMAN. Enfermería Intensiva, 25(4), 123–124. 10.1016/j.enfi.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heras La Calle, G. , Martin, M. C. , & Nin, N. (2017). Seeking to humanize intensive care. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva, 29(1), 9–13. 10.5935/0103-507x.20170003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heras La Calle, G. , Ovies, A. A. , & Tello, V. G. (2017). A plan for improving the humanisation of intensive care units. Intensive Care Medicine, 43(4), 547–549. 10.1007/s00134-017-4705-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoad, N. , Swinton, M. , Takaoka, A. , Tam, B. , Shears, M. , Waugh, L. , Toledo, F. , Clarke, F. J. , Duan, E. H. , Soth, M. , & Cook, D. J. (2019). Fostering humanism: A mixed methods evaluation of the footprints project in critical care. BMJ Open, 9(11), e029810. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, V. , Bergbom, I. , & Forsberg, A. (2012). The lived experiences of adult intensive care patients who were conscious during mechanical ventilation: A phenomenological‐hermeneutic study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 28(1), 6–15. 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvande, M. E. , Angel, S. , & Nielsen, A. H. (2021). Humanizing intensive care: A scoping review (HumanIC). Nursing Ethics, 9697330211050998, 498–510. 10.1177/09697330211050998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, F. M. , & Brito, E. S. (2009). Humanization of physiotherapy care: Study with patients post‐stay in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva, 21(3), 283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, K. (2006). Care and vulnerability. Akribe. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, K. (2010). Fra Marx til Løgstrup: Om etik og sanselighed i sygeplejen [From Marx to Løgstrup. About moral and sensibility in nursing] (Fink H. C., Trans.; 2. udgave ed.). Munksgaard Danmark. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, P. , Lanferdini, I. Z. , & Alves, V. B. (2018). Caregivers' perception when facing the care humanization in the immediate postoperative period from a cardiac surgery procedure. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado e Fundamental, 10(3), 810–816. 10.9789/2175-5361.2018.v10i3.810-816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondadori, A. G. , de Moraes Zeni, E. , de Oliveira, A. , Cosmo da Silva, C. , Waldow Wolf, V. L. , & Taglietti, M. (2016). Humanization of physical therapy in an intensive care unit for adults: A cross‐sectional study. Fisioterapia e Pesquisa, 23(3), 294–300. 10.1590/1809-2950/16003123032016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M. M. M. , Germano, R. M. , & Câmara, A. G. (2014). Aspects of nursing care in the intensive care unit. Journal of Nursing UFPE/Revista de Enfermagem UFPE, 8(3), 545–554. 10.5205/reuol.5149-42141-1-SM.0803201408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P. (1991). From text to action. Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Almagro, J. , Quero Palomino, M. A. , Aznar Sepulveda, E. , Fernandez‐Espartero Rodriguez‐Barbero, M. D. M. , Ortiz Fernandez, F. , Soto Barrera, V. , & Hernandez‐Martinez, A. (2019). Experience of care through patients, family members and health professionals in an intensive care unit: A qualitative descriptive study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(4), 912–920. 10.1111/scs.12689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rykkje, L. , Eriksson, K. , & Råholm, M. B. (2015). Love in connectedness: A theoretical study [article]. SAGE Open, 5(1), 215824401557118. 10.1177/2158244015571186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stayt, L. C. , Seers, K. , & Tutton, E. (2015). Patients' experiences of technology and care in adult intensive care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(9), 2051–2061. 10.1111/jan.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, A. C. (2017). Critical illness as a biographical disruption. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 26(4), 253–259. 10.1177/2010105817699843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, S. , Acharya, S. P. , Sahoo, A. K. , Mitra, J. K. , Goel, K. , Ahmad, S. R. , & Hansdah, U. (2020). Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries and the experiences of patients' families: A grounded theory approach in a lower middle‐income country (LMIC). Journal of Patient‐Reported Outcomes, 4(1), 63. 10.1186/s41687-020-00229-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urizzi, F. , Carvalho, L. M. , Zampa, H. B. , Ferreira, G. L. , Grion, C. M. , & Cardoso, L. T. (2008). The experience of family members of patients staying in intensive care units. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva, 20(4), 370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffin, C. J. , & Ellis‐Hill, C. (2021). How does a narrative understanding of change in families post brain injury help us to humanise our professional practice? [article]. Brain Impairment, 1‐9, 125–133. 10.1017/BrImp.2021.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

For this is review all included papers were accessible to the public.